Abstract

In this report, two chromotrope dyes, chromotropic acid (CA) and chromotrope 2R (CR), were explored as inhibitors against mild steel corrosion in 1.0 M sulfuric acid solutions at 303 K. Electrochemical, spectroscopic, chemical, and microscopic techniques, namely, potentiodynamic polarization (PDP), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, mass loss, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM), have been employed to evaluate the inhibition efficiencies (%IEs) of the examined organic dyes. The %IEs were found to increase with the inhibitors’ concentrations, while they decreased with rising temperature. The outcomes of the PDP technique displayed that the examined inhibitors operated as mixed-type inhibitors with anodic prevalence. The impedance spectra described by Nyquist and Bode graphs in the corrosive environment and in the presence of various concentrations of the examined inhibitors showed single depressed capacitive loops and one-time constants. This behavior signified that the mild steel corrosion was managed by the charge transfer process. The SEM micrographs of the surfaces of mild steel samples after adding the examined inhibitors revealed a wide coverage of these compounds on the steel surfaces. Thus, the acquired high %IEs of the examined inhibitors were interpreted by strong adsorption of the organic molecules on the mild steel surface. This constructed a shielding layer separating the alloy surface from the corrosive medium, and such adsorption was found to follow the Langmuir isotherm. Furthermore, the evaluated thermodynamic and kinetic parameters supported that the nature of such adsorption was mainly physical. Results obtained from all employed techniques were consistent with each other and revealed that the %IE of the CR inhibitor was slightly higher than that of CA under similar circumstances. Finally, the mechanisms of both corrosion of mild steel in sulfuric acid solutions and its inhibition by the tested organic dyes were also discussed.

Introduction

Mild steel is the supreme common form of steel alloys used in several industrial applications as well as in various everyday objects we use because of its availability, its good mechanical properties acceptable for such applications, and its relatively low price.1 Acidic media are employed in almost all industries such as acid cleaning, manufacturing and pickling of steel, petroleum processes, removal of rust in metal finishing from metallic surfaces, and so forth.2 However, because of the known aggressiveness of acidic media, steel vessels used in these processes are generally susceptible to corrosion attack,3−8 which is a serious problem facing economy and safety. Thus, it is essential to safeguard mild steel from the adversarial impact of acidic media. For this purpose, extensive studies have been carried out by various research groups to find the most efficient, economic, and environmentally compliant means to control the corrosion attack.9−20 This has been achieved by two ways: the first is to coat the surface of metal or alloy with a protective thin layer.9,10 An alternative method is to employ corrosion inhibitors, which is regarded as the supreme proficient, practical, convenient, and low-cost technique to inhibit the surfaces of metals and alloys against corrosion in aggressive environments.11−20

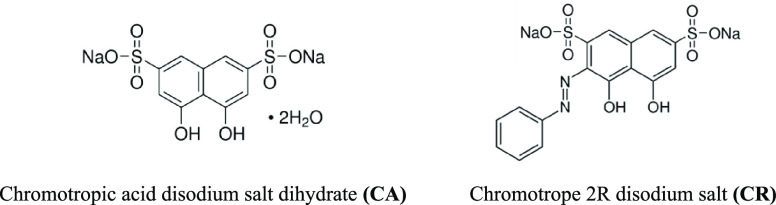

Organic dyes, in particular, have found substantial awareness because of their multipurpose applications in diverse fields, including cosmetics, textile, food, pharmaceuticals, and so forth.21−23 They are also employed in the corrosion inhibition of metals and alloys because of their distinctive chemical structures, which contain heteroatoms such as oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur, in addition to unsaturated bonds and aromatic rings.24,25 This strongly supports the adsorption of these molecules on the solid surfaces, forming protective layers and hence making them superior corrosion inhibitors to protect metallic surfaces. Among the organic dyes used as corrosion inhibitors are chromotropic acid (4,5-dihydroxynaphthalene-2,7-disulfonic acid) and chromotrope 2R (4,5-dihydroxy-3-(phenyldiazenyl) naphthalene-2,7-disulfonic acid), and their molecular structures are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structures of the two examined organic dyes.

In view of this, two dyes, chromotropic acid (CA) and chromotrope 2R (CR), were explored as unprecedented inhibitors for the corrosion of mild steel in an acidic environment of H2SO4 solution, which is regarded as the most frequently used mineral acid in the world. Various techniques such as potentiodynamic polarization (PDP), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), mass loss (ML), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) have been employed, at a fixed temperature, to evaluate the inhibition efficiencies (%IEs) of the examined organic dyes.

Results and Discussion

PDP Measurements

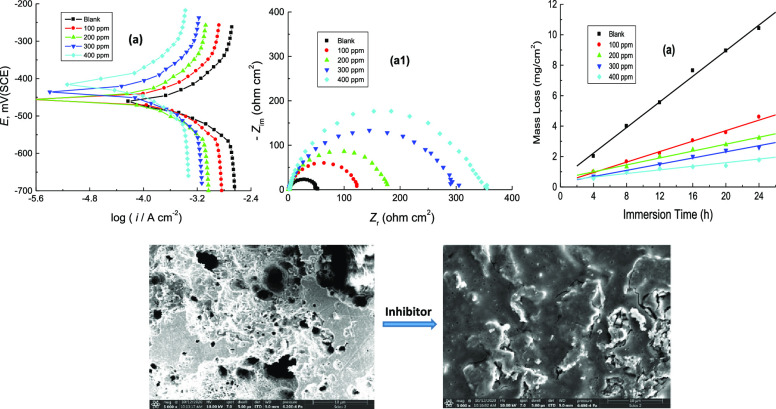

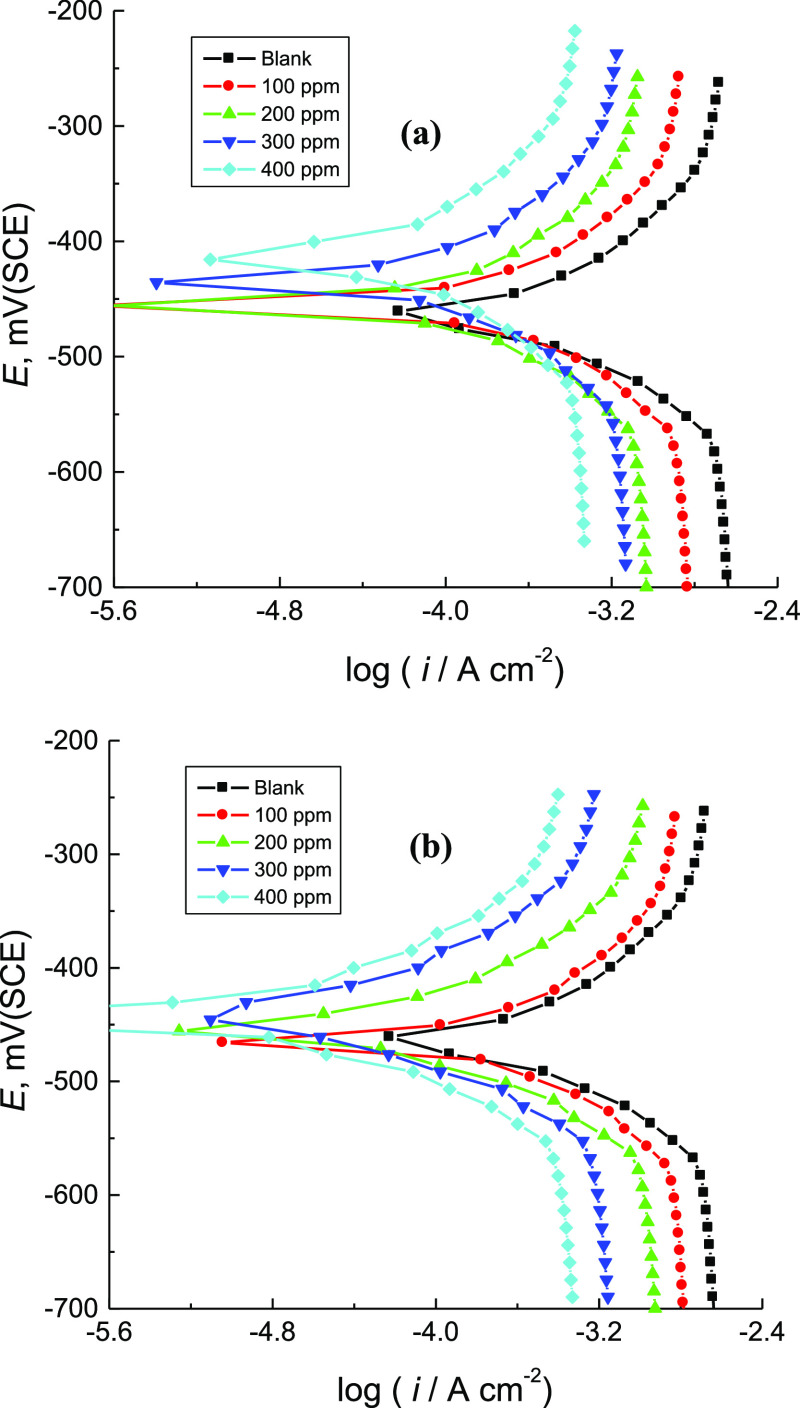

The PDP curves of mild steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution at 303 K without and with various concentrations of CA and CR are shown in Figure 2. The average values of the corrosion parameters, viz. corrosion potential (Ecorr), anodic and cathodic Tafel slopes (βa and βc), corrosion current density (icorr), polarization resistance (Rp), %IE, and surface coverage (θ) of the examined organic dyes, were determined and are listed in Table 1. From Figure 2(a,b) and the data inserted in Table 1, it can be noticed that adding the examined organic dyes to the corrosive medium transformed both anodic and cathodic branches of the polarization curves to lower current densities. This behavior indicated delay of both anodic and cathodic reactions and then inhibition of mild steel corrosion. The value of Ecorr for mild steel in the corrosive medium was shifted to positive directions as a result of adding the tested dyes, revealing that these compounds act as mixed-type inhibitors with a major anodic type.26 The value of βa in the corrosive medium did not change noticeably with addition of the organic inhibitors while the βc value was gradually increased. This suggested that the adsorbed molecules did not affect the anodic metal dissolution and enhanced the cathodic hydrogen evolution. Also, the value of icorr of mild steel in the corrosive medium was reduced with increasing the concentration of the examined organic dyes indicating protection impacts. However, the obtained value of Rp of the corrosive medium was found to increase with increasing dye concentrations, indicating a decrease in the corrosion rate (C.R.) of mild steel in the presence of the examined organic dyes. The acquired results indicated that, under similar investigational conditions, the %IE of the inhibitor CR was slightly higher than that of the inhibitor CA. This behavior may be attributed to the substituted azo group in CR, which enhances the inhibition performance of this dye.

Figure 2.

PDP curves for the corrosion of mild steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution without and with various concentrations of: (a) CA and (b) CR at 303 K.

Table 1. Average Corrosion Parameters Acquired from PDP Curves in the Corrosion of Mild Steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 Solution without and with Various Concentrations of CA and CR at 303 K.

| blank + | inh. conc. (ppm) | –Ecorr (mV(SCE)) | βa (mV/dec.) | –βc (mV/dec.) | icorr (μA/cm2) | Rp (ohm cm2) | % IE | θ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 458 | 115 | 96 | 431 | 55 | |||

| CA | 100 | 457 | 117 | 100 | 211 | 111 | 51 | 0.51 |

| 200 | 454 | 123 | 103 | 134 | 182 | 69 | 0.69 | |

| 300 | 434 | 118 | 107 | 91 | 268 | 79 | 0.79 | |

| 400 | 415 | 121 | 112 | 73 | 349 | 83 | 0.83 | |

| CR | 100 | 457 | 118 | 98 | 198 | 118 | 54 | 0.54 |

| 200 | 452 | 114 | 101 | 116 | 201 | 73 | 0.73 | |

| 300 | 450 | 111 | 103 | 69 | 337 | 84 | 0.84 | |

| 400 | 447 | 117 | 109 | 56 | 438 | 87 | 0.87 |

EIS Measurements

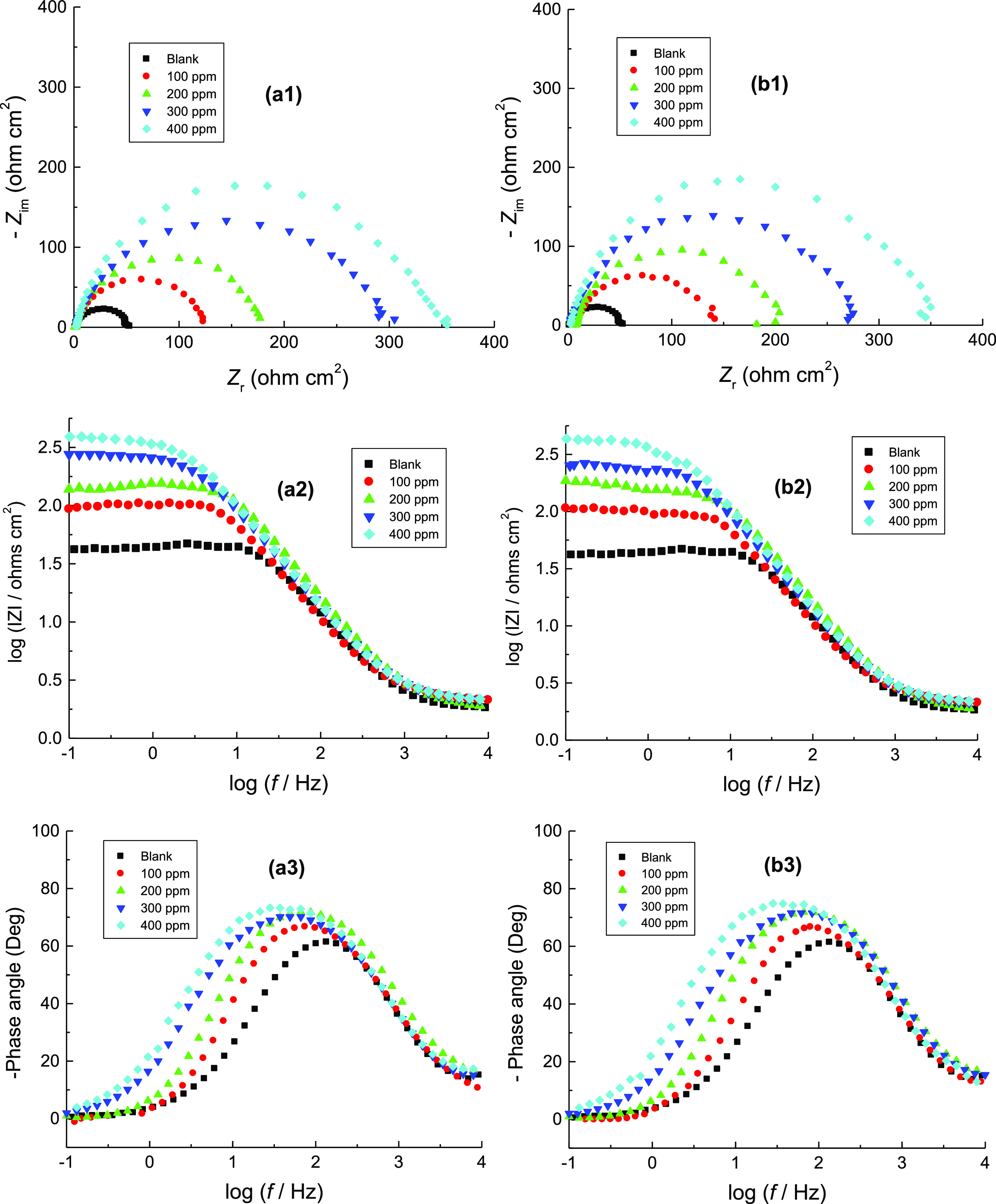

The corrosion of mild steel was studied in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution in the absence and presence of 100–400 ppm of CA and CR at 303 K after dipping of the steel specimens in the blank solution for about 40 min. by the EIS technique. The obtained Nyquist and Bode graphs are shown in Figure 3(a,b). It is noticed from the Nyquist (a1,b1) and Bode magnitude (a2,b2) graphs that the acquired impedance spectra consist of single depressed capacitive loops and one-time constants, respectively. This suggested that the adsorption of examined inhibitor molecules occurs by a simple surface coverage, and the corrosion process is operated by the charge transfer process.27 Also, the communal shape of the obtained graphs was the same in the absence and presence of the inhibitors at different concentrations suggesting that there was no change in the mechanism of mild steel corrosion.28 It is also observed from the Nyquist graphs that the size of the capacitive semicircle in the corrosive medium increased considerably after adding the examined inhibitors. This behavior revealed a reduction in the C.R. of mild steel and enhancement of the %IEs, and the latter increased as the inhibitors’ concentrations increased. In addition, the Bode phase graphs (a3,b3) showed that the phase angle of the inhibited steel samples was higher than that of the uninhibited sample, and the phase angle was increased with increasing the concentration of added inhibitors. Increasing phase angle indicated that the metallic surface considerably becomes smooth as a result of the construction of a protective layer by the adsorbed inhibitor molecules over the steel surface and decreased the steel dissolution rate.29

Figure 3.

(a1, b1) Nyquist graphs, (a2, b2) Bode magnitude graphs, and (a3, b3) Bode phase graphs for the corrosion of mild steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution without and with various concentrations of: (a) CA and (b) CR at 303 K.

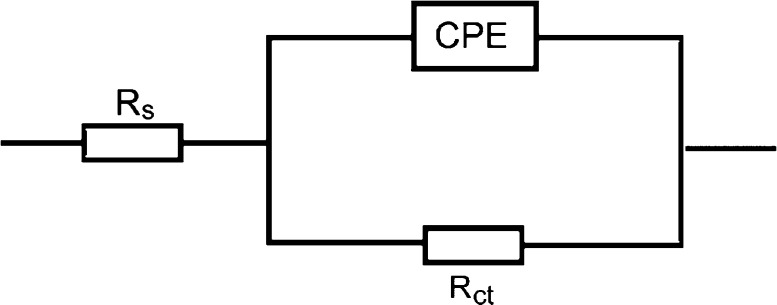

The impedance spectra were analyzed by fitting to the electrochemical equivalent circuit model illustrated in Figure 4. The circuit contains a solution resistance, Rs shorted by a constant phase element, CPE, present in the circuit in place of the pure double-layer capacitor to provide a more accurate fit, that is located in parallel to the charge transfer resistance, Rct. Utilizing the CPE, because of the depressed character of the Nyquist semicircles, suggests surface heterogeneity as a result of surface roughness, impurities, adsorption of inhibitor molecules, and construction of porous layers.30

Figure 4.

Electrochemical equivalent circuit used to fit the obtained EIS output data for the corrosion of mild steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution without and with the examined organic dyes.

The average values of the impedance parameters, viz. Rs, Rct, CPE, % IE, and θ, were determined from the impedance spectra and are given in Table 2. The data listed in Table 2 showed that adding the examined dyes to the corrosive medium resulted in augmenting the value of Rct of the medium-free inhibitor, and such behavior was found to greatly increase with increasing inhibitors’ concentrations. This was connected with a decrease in the value of the CPE, which results from a decrease in the dielectric constant and/or an increase in the double-layer thickness. This suggests adsorption of the organic molecules onto the metal/solution interface30 leading to protection of the metal surface from the corrosive medium attack. Also, increasing the value of Rct with increasing inhibitor concentrations indicates that the number of inhibitor molecules adsorbed on the surface of mild steel increases. This forms protective films on the electrode surface, which consequently became barriers to hinder the mass and charge transfer, resulting in an increase in the %IEs.31 With the increase in the concentration of the examined compounds, the protection efficiencies increased, which further confirms that these compounds were proficient inhibitors for the corrosion of mild steel in sulfuric acid medium. Also, under the same experimental circumstances, the %IE of CR was somewhat higher than that of CA.

Table 2. Average Corrosion Parameters Acquired from the Impedance Graphs in the Corrosion of Mild Steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 Solution without and with Various Concentrations of CA and CR at 303 K.

| blank + | inh. conc. (ppm) | Rs (ohm cm2) | Rct (ohm cm2) | CPE (μF/cm2) | % IE | θ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.93 | 53 | 298 | |||

| CA | 100 | 2.09 | 123 | 143 | 57 | 0.57 |

| 200 | 1.73 | 177 | 112 | 70 | 0.70 | |

| 300 | 2.17 | 295 | 87 | 82 | 0.82 | |

| 400 | 3.02 | 353 | 75 | 85 | 0.85 | |

| CR | 100 | 1.19 | 143 | 124 | 63 | 0.63 |

| 200 | 3.28 | 204 | 96 | 74 | 0.74 | |

| 300 | 8.97 | 279 | 79 | 81 | 0.81 | |

| 400 | 6.41 | 355 | 72 | 85 | 0.85 |

ML Measurements and the Impact of Temperature

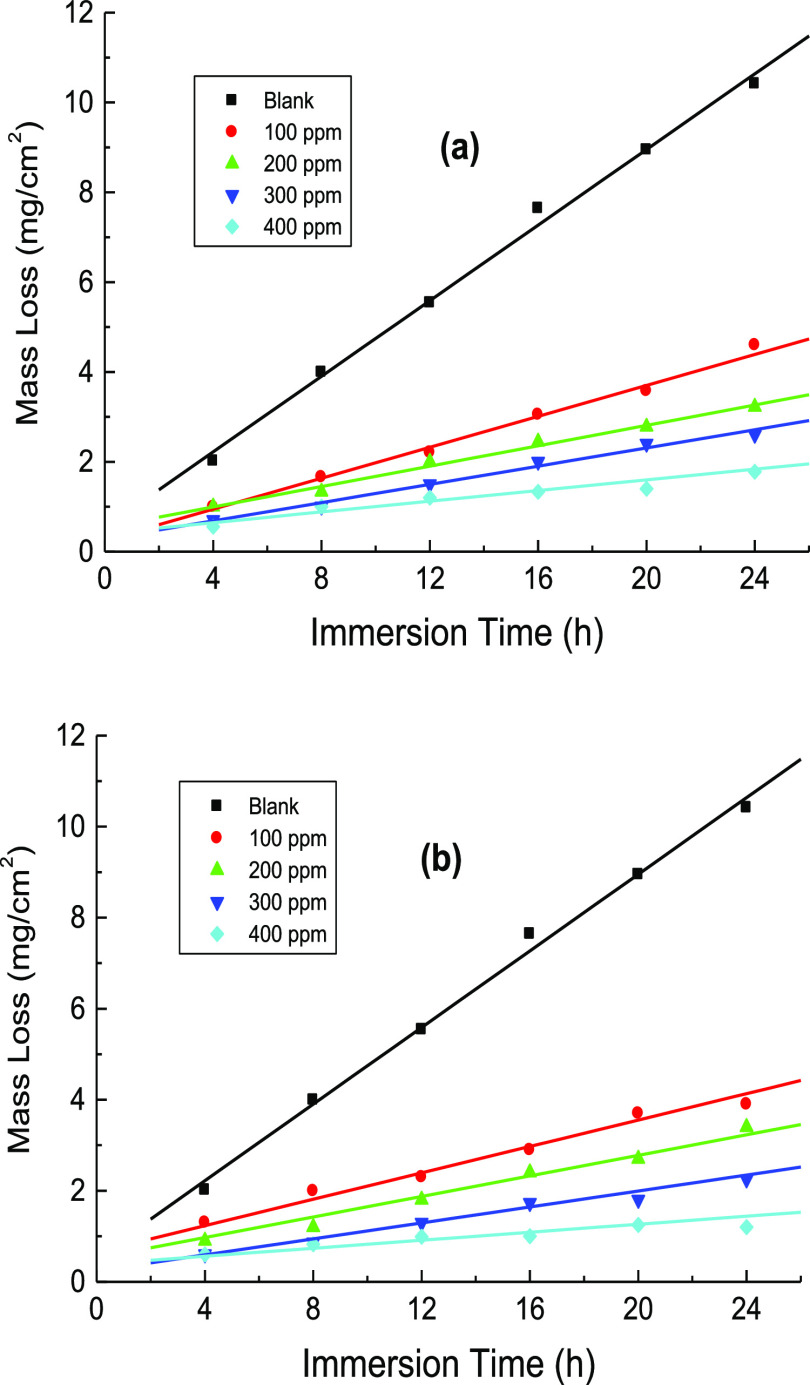

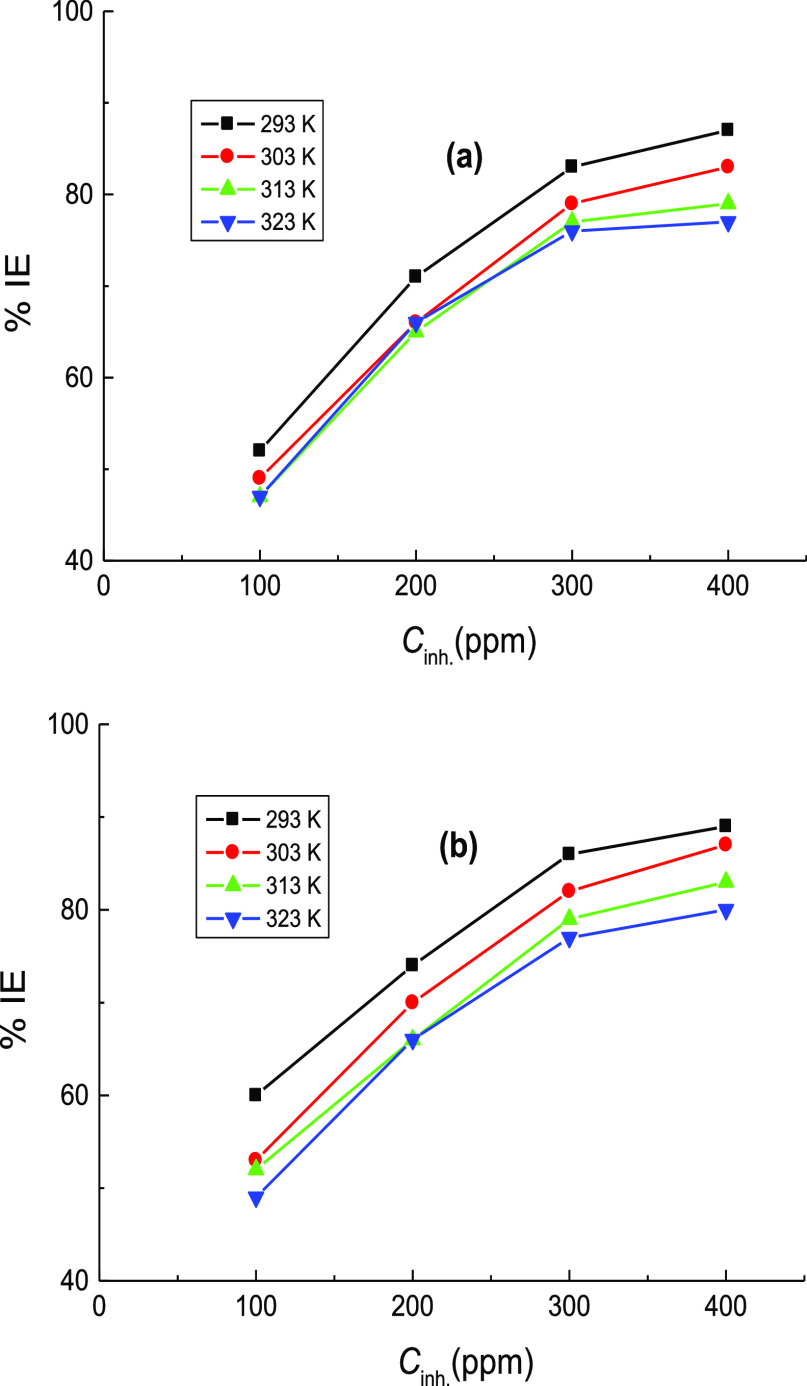

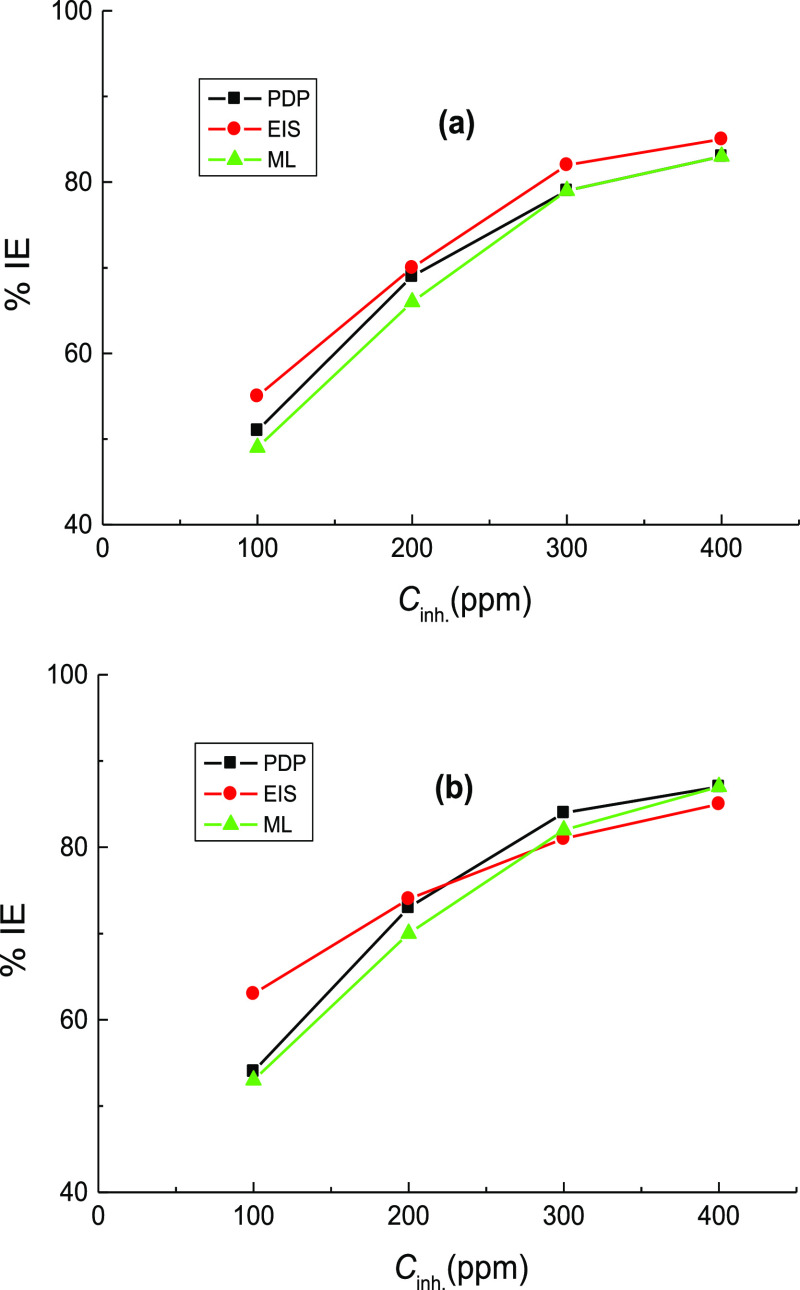

ML measurements of mild steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution were performed at certain time intervals in the corrosive medium-free inhibitors and in the presence of 100–400 ppm of CA and CR at different temperatures (293–323 K). Figure 5(a,b) illustrates only the ML against immersion time plots acquired at 303 K. Similar plots were achieved at other temperatures but not shown here. The average values of the C.R., θ, and %IE of the examined organic dyes are also listed in Table 3. From Table 3, it is evident that, at fixed temperature, the values of C.R. were reduced while the %IEs were increased with the inhibitors’ concentrations. This can be ascribed to increasing adsorption coverage of inhibitor molecules on the steel surface with their concentrations, which decreased the dissolution rates of mild steel. Thus, the examined organic dyes are regarded as proficient inhibitors for the corrosion of mild steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 solutions. On the other hand, with rising temperature at fixed inhibitor concentration, the value of C.R. was increased, and %IE was decreased. In this context, the change of %IEs of the examined dyes with their concentrations at different temperatures is illustrated in Figure 6. This behavior can be attributed to the acceleration of the hydrogen evolution reaction in acidic medium with rising temperature and thus reduction in inhibitor adsorption. This suggested the mechanism of physical adsorption of the inhibitor molecules on the electrode surface.32 In consistence with both PDP and EIS techniques, the values of %IE, acquired from ML measurements, of the inhibitor CR was also in general higher than those of the inhibitor CA. Furthermore, a comparison of the variation of the %IEs of the investigated dyes with their concentrations at 303 K, obtained from all employed techniques, PDP, EIS, and ML, is shown in Figure 7. The illustrated figure revealed that the results gained from all the utilized techniques are in good accordance with each other.

Figure 5.

ML against immersion time for mild steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution without and with various concentrations of: (a) CA and (b) CR at 303 K.

Table 3. Average Values of C.R. (mpy) of Mild Steel Gained from ML Measurements, %IE, and θ of CA and CR with Various Concentrations at Diverse Temperatures.

| temperature

(K) |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 293 |

303 |

313 |

323 |

||||||||||

| blank + | inh. conc. (ppm) | C.R. | % IE | θ | C.R. | % IE | θ | C.R. | % IE | θ | C.R. | % IE | θ |

| 0 | 164 | 177 | 187 | 195 | |||||||||

| CA | 100 | 79 | 52 | 0.52 | 91 | 49 | 0.49 | 99 | 47 | 0.47 | 103 | 47 | 0.47 |

| 200 | 48 | 71 | 0.71 | 60 | 66 | 0.66 | 65 | 65 | 0.65 | 66 | 66 | 0.66 | |

| 300 | 28 | 83 | 0.83 | 37 | 79 | 0.79 | 43 | 77 | 0.77 | 47 | 76 | 0.76 | |

| 400 | 21 | 87 | 0.87 | 30 | 83 | 0.83 | 39 | 79 | 0.79 | 45 | 77 | 0.77 | |

| CR | 100 | 66 | 60 | 0.60 | 83 | 53 | 0.53 | 90 | 52 | 0.52 | 99 | 49 | 0.49 |

| 200 | 43 | 74 | 0.74 | 53 | 70 | 0.70 | 64 | 66 | 0.66 | 65 | 66 | 0.66 | |

| 300 | 23 | 86 | 0.86 | 32 | 82 | 0.82 | 39 | 79 | 0.79 | 44 | 77 | 0.77 | |

| 400 | 18 | 89 | 0.89 | 23 | 87 | 0.87 | 32 | 83 | 0.83 | 39 | 80 | 0.80 | |

Figure 6.

Variation of %IE of: (a) CA and (b) CR with their concentrations at diverse temperatures, obtained from ML measurements, in the corrosion of mild steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution.

Figure 7.

Variation of %IEs of: (a) CA and (b) CR with their concentrations at 303 K, gained from PDP, EIS, and ML measurements, in the corrosion of mild steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution.

However, from the literature it was found that the examined organic dyes exhibited higher %IEs than other reported organic dyes for the corrosion of mild steel in sulfuric acid solutions.33−35

Adsorption Isotherm

The investigated organic dyes were set to be proficient inhibitors against the corrosion of mild steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution. They contain heteroatoms, such as oxygen and sulfur in CA and oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur in CR, in addition to aromatic rings, which can be adsorbed on the metal surface forming protective layers.24,25 These layers can be constructed by one of the following adsorption modes:36 (1) physisorption of the inhibitor molecules on the metal surface as a result of the electrostatic attraction among the protonated groups of the inhibitor molecules (in acidic medium) and the charged metal surface; (2) chemisorption by constructing coordination bonds among the empty d orbital of iron and the lone pair of electrons of the heteroatoms; or (3) coexistence of the two-mentioned adsorption types.

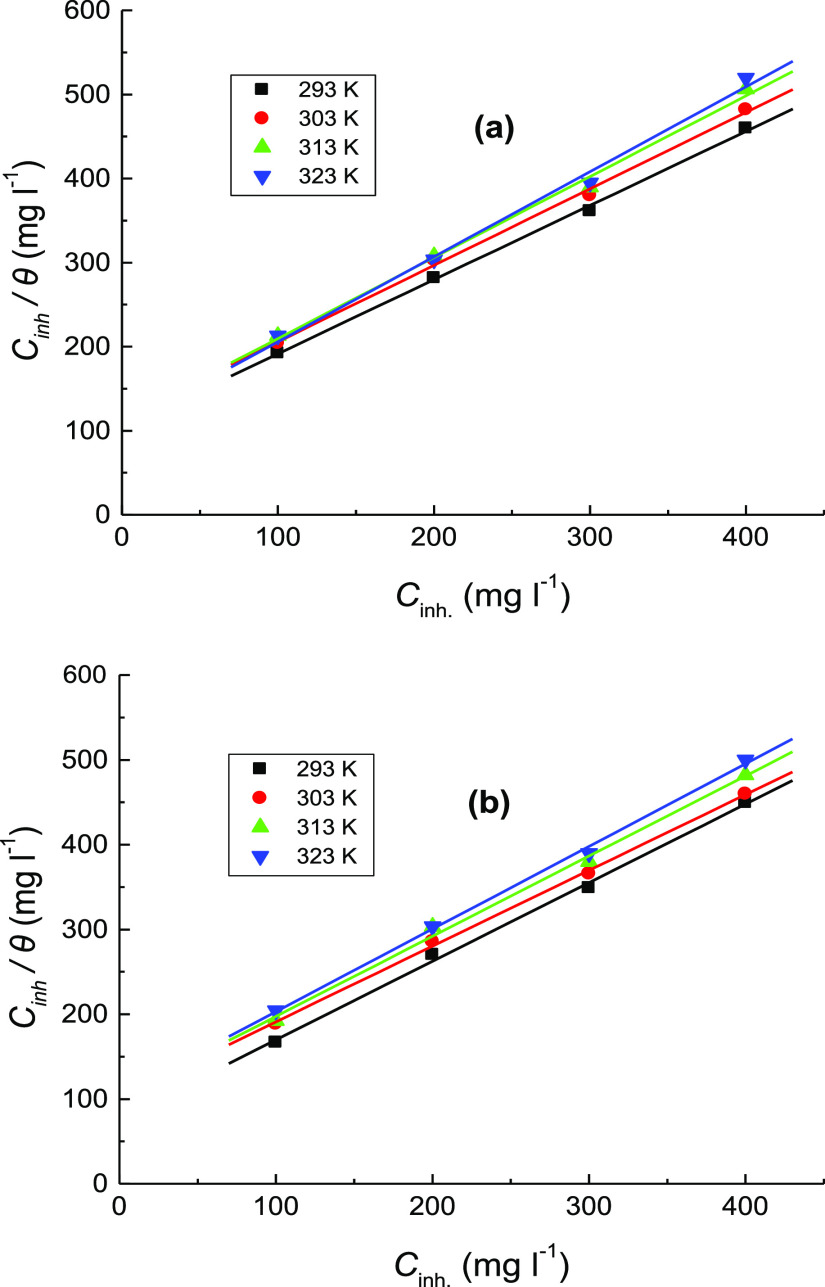

To examine the best-fit adsorption isotherm (Langmuir, Temkin, Freundlich, or Frumkin type) of the tested organic dyes, the plots of fractional surface coverage (Cinh/θ) against inhibitors’ concentrations (Cinh) at diverse temperatures were illustrated. Straight lines with about unit slopes were acquired as shown in Figure 8(a,b) confirming that the adsorption of the investigated inhibitors on the mild steel surface agreed with the Langmuir adsorption isotherm37,38 which is provided by the following equation,39

| 1 |

Figure 8.

Langmuir adsorption isotherms for: (a) CA and (b) CR at different temperatures in the corrosion of mild steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution.

where Kads is the absorptive equilibrium constant that was evaluated and inserted in Table 4. This table manifested that the values of Kads were reduced with rising temperature, demonstrating strong adsorption of the inspected organic dyes on the mild steel surface at relatively lower temperature, but at higher temperatures, the adsorbed molecules tend to desorb from the steel surface.

Table 4. Values of Kads and Thermodynamic Parameters for the Corrosion of Mild Steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 Solution Containing Various Concentrations of CA and CR at Diverse Temperatures.

| blank + | temperature (K) | 10–3Kads l mol–1 | ΔGoads kJ mol–1 | ΔHoads kJ mol–1 | ΔSoads(303) J mol–1 K–1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA | 293 | 10.71 | –13.32 | –5.74 | 25.02 |

| 303 | 9.97 | –13.60 | 25.94 | ||

| 313 | 9.26 | –13.86 | 26.80 | ||

| 323 | 8.61 | –14.10 | 27.59 | ||

| CR | 293 | 12.08 | –14.05 | –8.15 | 19.47 |

| 303 | 10.82 | –14.26 | 20.16 | ||

| 313 | 9.94 | –14.49 | 20.92 | ||

| 323 | 9.13 | –14.74 | 21.75 |

Thermodynamic Parameters

The standard free energy of adsorption (ΔGoads) was calculated using Kads as the equation,40

| 2 |

The evaluated values of ΔGoads for the two examined organic compounds at diverse temperatures are inserted in Table 4. From Table 4, it can be noticed that the obtained values of ΔGoads for the inhibitor CR were higher than those acquired for the inhibitor CA suggesting that the molecules of the inhibitor CR were more strongly adsorbed on the surface of mild steel in the corrosive medium than those of the inhibitor CA. This is in good agreement with the values of %IE of the examined organic dyes gained from all the utilized techniques; that is, %IE of the inhibitor CR was higher than that of CA. On the other hand, the obtained ΔGoads values were lower than −20 kJ mol–1 suggesting that the nature of adsorption of the tested organic dyes on the mild steel surface was mainly physical.41

The standard adsorptive heat (ΔHoads) was computed using the Van’t Hoff equation,42

| 3 |

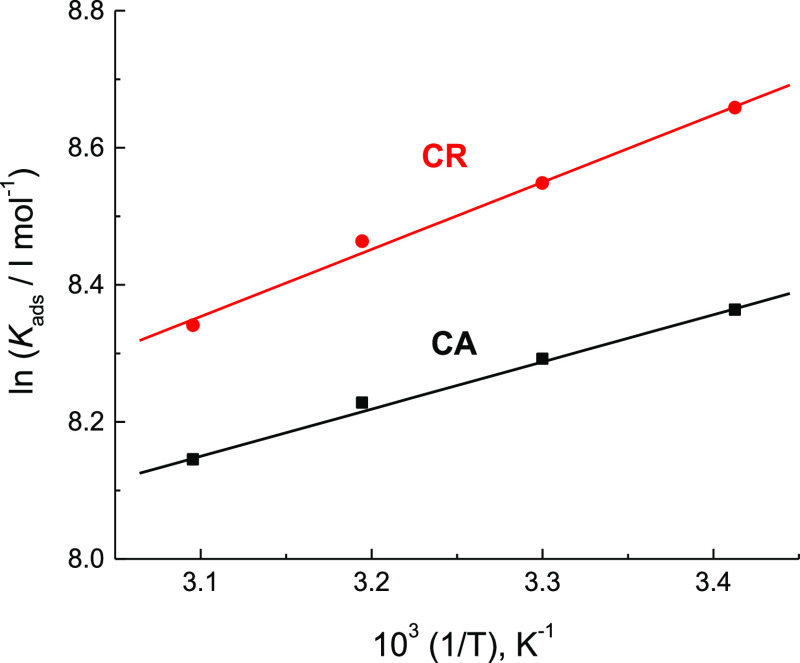

The plots of ln Kads versus 1/T gave good straight lines as shown in Figure 9; thus the values of ΔHoads were obtained and are listed in Table 4. The low negative values acquired for ΔHoads for each of the two inhibitors examined (−5.74 and −8.15 kJ mol–1) revealed that the adsorption of these molecules is an exothermic process with a predominant physical nature (physisorption).43,44

Figure 9.

Van’t Hoff plots of CA and CR adsorbed on the surface of mild steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution.

Finally, the standard entropy of adsorption (ΔSoads) was calculated from the rearranged Gibbs–Helmholtz equation,

| 4 |

The obtained positive values of ΔSadso(Table 4) suggested the increased randomness during the adsorption process at the metal/solution interface, which may be attributed to adsorption of additional water molecules from the mild steel surface by the inhibitor molecules.45

Kinetic Parameters

The dependency of C.R. on temperature is expressed by the Arrhenius equation as follows:46

| 5 |

where Ea* is the activation energy.

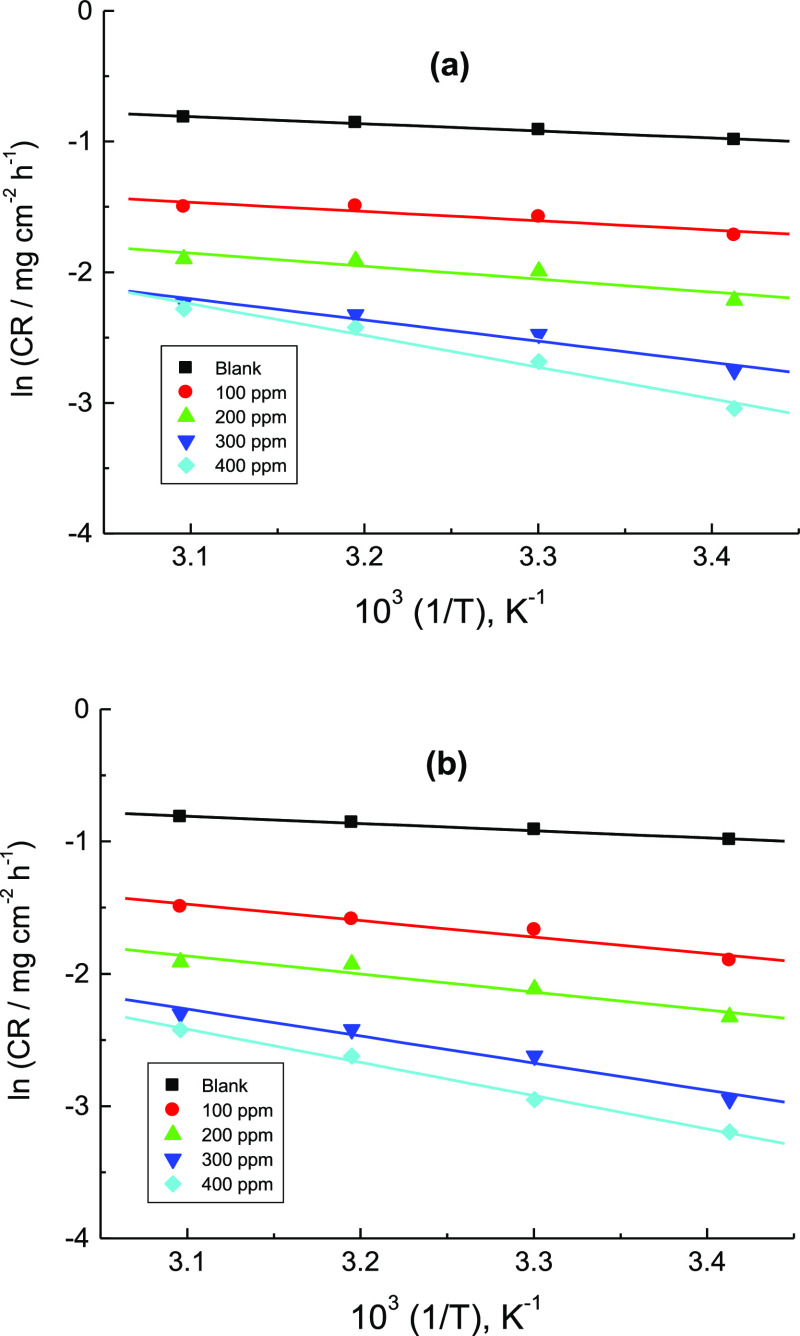

Figure 10 shows the Arrhenius plots for mild steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution without and after addition of various concentrations of the tested organic dyes. The evaluated values of Ea* (Table 5) in the presence of the inhibitors were found to be higher than those obtained in the corrosive solution verifying adsorption of the tested molecules on the mild steel surface and constructing a barrier between the steel surface and the corrosive medium.36

Figure 10.

Arrhenius plots for the corrosion of mild steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution without and with addition of various concentrations: (a) CA and (b) CR.

Table 5. Activation Parameters of the Corrosion of Mild Steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 Solution without and with Addition of Various Concentrations of CA and CR.

| blank + | inh. concn. (ppm) | Ea* kJ mol–1 | ΔH* kJ mol–1 | ΔS* J mol–1 K–1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4.53 | 4.65 | –39.91 | |

| CA | 100 | 5.86 | 6.32 | –38.49 |

| 200 | 8.25 | 8.89 | –33.25 | |

| 300 | 13.48 | 12.97 | –24.11 | |

| 400 | 20.12 | 16.96 | –12.47 | |

| CR | 100 | 10.27 | 10.64 | –27.43 |

| 200 | 11.31 | 13.30 | –23.44 | |

| 300 | 16.96 | 18.56 | –8.31 | |

| 400 | 20.78 | 21.20 | –0.83 |

Furthermore, the range of Ea* values (5.86–20.78 kJ mol–1) is lower than 80 kJ mol–1 confirming the physical adsorption of the examined inhibitors.41 These results are in good agreement with those based on the values of both ΔGoads and ΔHoads indicating the validity of the acquired investigational outcomes.

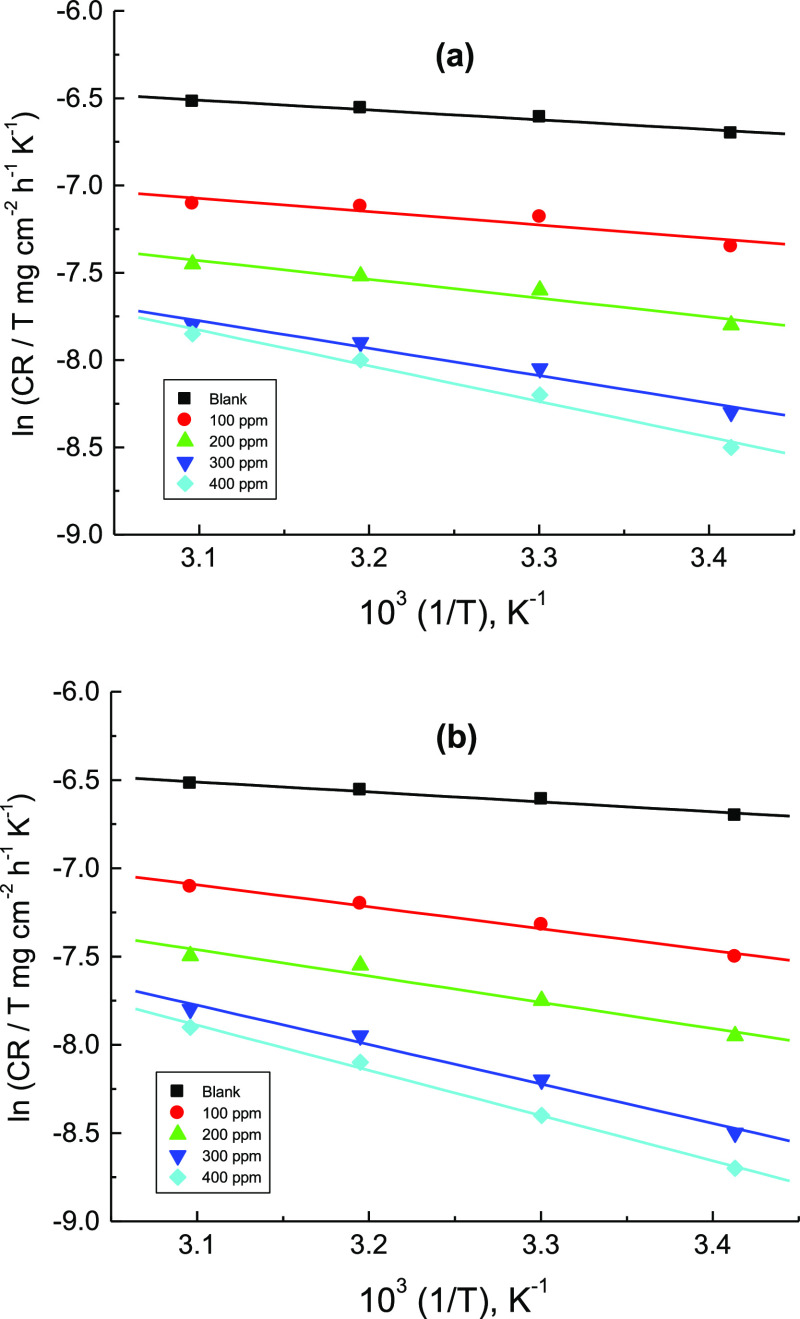

The enthalpy of activation (ΔH*) and entropy of activation (ΔS*) of metal corrosion are computed using the transition state equation,47

| 6 |

where N is Avogadro’s number and h is Planck’s constant. Plots of ln(CR/T) versus 1/T gave good straight lines, which appeared in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Arrhenius plots for the corrosion of mild steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution without and with addition of various concentrations of: (a) CA and (b) CR.

The computed values of ΔH* and ΔS* are presented in Table 5. The positive values of ΔH* propose that the corrosion process was endothermic. Also, the acquired negative values of ΔS* in the absence and presence of the inhibitors suggest construction of an activated complex, leading to a reduction in the disorder.48

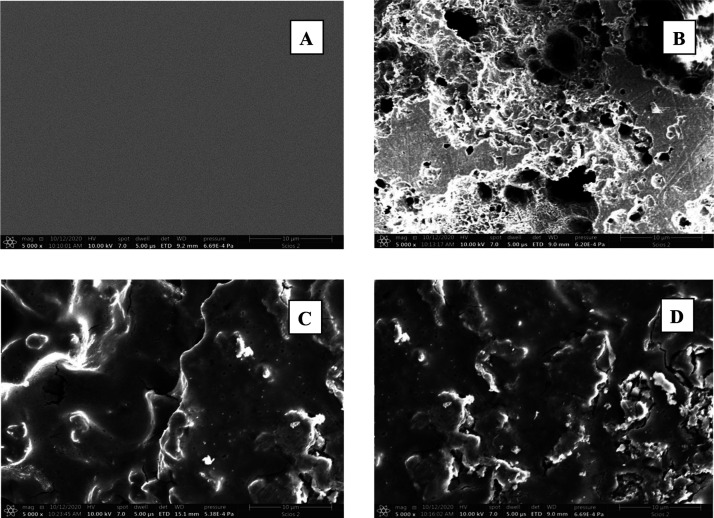

Surface Investigations

SEM micrographs of the surfaces of mild steel samples in 1.0 M H2SO4-free inhibitor solutions and in the presence of the tested organic dyes are shown in Figure 12(a–d). Figure 12(a,b) manifests a polished mild steel surface before and after 24 h dipping in the corrosive medium, respectively. Figure 12(b) shows a strong damage of the surface of steel sample as a result of its exposure to the corrosive medium. Figure 12(c,d) shows SEM micrographs after addition of a 200 ppm of CA and CR, respectively, to the corrosive medium (1.0 M H2SO4). It can be observed that the surfaces of mild steel samples were greatly covered with the tested organic dyes on the whole surfaces, which is ascribed to strong adsorption of the inhibitor molecules on the steel surfaces, leading to shielding steel surfaces from the corrosive medium and hence showing a proficient corrosion inhibition.

Figure 12.

SEM micrographs (x 5000) of the surfaces of mild steel samples: (A) polished, (B) after 24 h dipping in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution, and (C, D) after 24 h dipping in a solution of 1.0 M H2SO4 + 200 ppm of CA and CR, respectively.

Mechanism of Corrosion and Corrosion Inhibition

Generally, corrosion of steel alloys in H2SO4 solution is mainly uniform corrosion.49 When the mild steel sample is dipped in H2SO4 solution, an attack on the steel alloy will occur with evolution of H2 and formation of ferrous cations (Fe2+). This mechanism has been explained by the following stages,47

Anodic dissolution proceeds throughout the following equations:

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

| 10 |

| 11 |

| 12 |

Also, cathodic H2 evolution occurs via the following equations:

| 13 |

| 14 |

| 15 |

However, based on the obtained experimental outcomes gained from the different employed techniques which signified that the tested organic dyes act as proficient inhibitors for the corrosion of mild steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution as well as the previously reported studies,50,51 the mechanism of the inhibition process by the examined organic dyes was discussed in terms of the adsorption of the dye molecules at the metal/solution interface. The nature of the adsorption process may be physical, chemical, or a mixture of the two-mentioned adsorption types.36 The evaluated thermodynamic and kinetic parameters in the present study supported that the nature of adsorption of the two examined inhibitors on the steel surface in H2SO4 solution was mainly physical. Adsorption of the inhibitor molecules on the steel surface was set to depend on their chemical structures, intensity of surface charge, potential of zero charge (PZC) of metal, and the composition of the corrosive environment. The chemical structures of the examined dyes (Figure 1) reveal that the dye molecules have various adsorption modes, which can be summarized as follows. First, in an acidic medium, portions of the dye molecules were protonated,52 and thus the protonated cations coexist with the neutral dye molecules. Therefore, it became necessary to calculate the value of PZC of iron in the examined H2SO4 solution at the zero point to understand the charge type on the iron surface. PZC can be calculated using the equation,53

| 16 |

where Ecorr and Eq refer to the corrosion potential and PZC of iron, respectively. As recorded earlier,54 the Eq value of iron in H2SO4 solution is equal to −550 mV versus SCE. As listed in Table 1, the recorded Ecorr value for mild steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 was −458 mV versus SCE. Hence, the PZC value of steel is +92 mV indicating that the surface of mild steel was positively charged. Thereby, electrostatic repulsion is expected to take place between the protonated inhibitor molecules and the positively charged steel surface. Meanwhile, in H2SO4 solution the positively charged steel surface is also expected to be covered with the initially adsorbed negatively charged sulfate anions (SO42–) creating an excess negative charge on the steel surface. Therefore, an electrostatic attraction between the negatively charged surface and the protonated inhibitor molecules will occur forming a protective layer on its surface (physical adsorption),43 which is why the C.R. is remarkably reduced as listed in Tables 1–3. Second, adsorption of the dye molecules may occur via formation of coordinate bonds between the lone pairs of electrons located on the oxygen and sulfur atoms in CA, and oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur in CR, and the vacant d-orbitals of Fe atoms. In addition, π-electrons in the aromatic rings of the examined dye molecules can make adsorption throughout a donor–acceptor interaction (chemical adsorption).55 Third, the examined dye molecules are considered as good ligands, which can chelate with metal ions to construct coordination complexes.56 Thus, they may chelate with Fe2+ ions formed on the steel surface establishing metal–inhibitor complexes [Fe2+ – Inh.]ads that form a blocking barrier to further dissolution according to the following equation,

| 17 |

Furthermore, adsorption of inhibitor molecules involves substitution of one or more water molecules adsorbed on the metal surface with such molecules or with the anions of the acid medium,57

| 18 |

Finally, in sulfuric acid solution, iron oxidizes and ferrous sulfate (FeSO4) forms with evolution of H2, as described by the following equation,58

| 19 |

The produced FeSO4 is less soluble and strongly adheres to the steel surface constructing a protective layer, which inhibits the steel surface against further attack by H2SO4.

Conclusions

In the present investigation, we studied the %IEs of CA and CR dyes against the corrosion of mild steel in 1.0 M sulfuric acid solution at a fixed temperature of 303 K. Different techniques were employed, namely, PDP, EIS, ML, and SEM. The obtained outcomes of the different employed techniques proved that CA and CR dyes act as proficient inhibitors for the corrosion of mild steel in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution. Under similar conditions, the %IE of CR was found to be slightly higher than that of CA. The %IEs were increased with the inhibitor concentrations, while they decreased with rising temperature. The examined inhibitors acted as mixed-type inhibitors with anodic prevalence. The obtained impedance spectra signified that the mild steel corrosion in sulfuric acid was managed by the charge transfer process. The SEMimages revealed a wide coverage of the examined inhibitor molecules on the steel surfaces. Thus, the acquired high %IEs of the examined inhibitors were interpreted by strong adsorption of the organic molecules on the mild steel surfaces. This adsorption was found to follow the Langmuir adsorption isotherm. The evaluated thermodynamic and kinetic parameters supported that the nature of such adsorption was mainly physical. Results obtained from all employed techniques were set to accord with each other. The mechanisms of both corrosion of mild steel in sulfuric acid solutions and its inhibition by the tested organic dyes were also discussed. Finally, from the literature it was found that the examined organic dyes exhibited higher %IEs than other reported organic dyes for the corrosion of mild steel in sulfuric acid solutions.

Experimental Section

Materials

In this work, all the used solutions were prepared afresh from Merck or Sigma-Aldrich chemicals in doubly distilled water. A stock solution of sulfuric acid (corrosive medium) was prepared by dilution of 99% H2SO4 (Merck) with doubly distilled water, and the required concentrations were acquired via dilution. The examined organic compounds (inhibitors), CA disodium salt dihydrate (C10H10O10S2Na2) 98% (Sigma-Aldrich), and CR disodium salt (C16H10O8N2S2Na2) 95% (Sigma-Aldrich) were also prepared using doubly distilled water, and they were employed in the concentration range of 100–400 ppm (mg l–1). The reproducibility of the acquired results was attained throughout repeat of each experiment almost three times under the same circumstances. Corrosion tests were performed on mild steel samples (SABIC Company, Saudi Arabia), which have the composition (wt %): 0.070 C, 0.070 Si, 0.012 S, 0.021 P, and 0.270 Mn and the rest is iron.

Methods

Both PDP and EIS techniques were carried out utilizing a PGSTAT30 potentiostat/galvanostat in a three-electrode cell with a temperature-control containing Pt counterelectrode, a saturated calomel electrode as a reference electrode, and the examined mild steel sample as a working electrode (WE). Before each experiment, the WE was prepared for these measurements,5−7 where the exposed area of the WE was 0.5027 cm2 and was immediately dipped into the corrosive medium (1.0 M H2SO4) and /or a prerequisite inhibitor concentration at open circuit potential (OCP) for about 40 min or until a stable potential was attained. In PDP, the electrode potential was changed automatically in the range from −200 to +200 mV versus OCP at a scan rate of 2.0 mV/s. The values of both % IE and θ of the examined inhibitors on the surface of mild steel were computed from the equation,59

| 20 |

where icorr and icorr(inh) are corrosion current densities without and with the inhibitors, respectively.

EIS measurements were performed in a frequency range of 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz with an amplitude of 4.0 mV from peak to peak exploitation of AC signals in OCP. Also, values of % IE were calculated from the charge transfer resistance (Rct) using the equation,60

| 21 |

where Rct and Rct(inh) are the charge transfer resistance values (in ohms cm2) without and with inhibitors, respectively.

ML measurements were performed in temperature-controlled vessels. Mild steel samples used in this work were cylindrical rods of areas about 12.6 cm2, which were prepared for these measurements as mentioned previously.5−7 The values of C.R. were computed in mpy (mils penetration per year) from the equation,61

| 22 |

where K is a constant, W is the ML in g, A is the area of the specimen in cm2, t is the time in hour, and d is the density of mild steel (7.86 g/cm3). The values of %IE and θ of the studied organic inhibitors were also evaluated using the following equation:59

| 23 |

where C.R. and C.R.inh are corrosion rates in the absence and presence of inhibitors, respectively.

Surface morphologies of mild steel samples were investigated before and after addition of 200 ppm of the examined organic dyes using a JEOL scanning electron microscope model T-200 by application of a repetition voltage of 10.0 kV. The surfaces of these samples were first abraded with emery papers (grades 200 to 1200) and rinsed with doubly distilled water. Before examination, the sample was immersed in the examined solution for 24 h at 303 K.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project number 510.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Ahamad I.; Prasad R.; Quraishi M. A. Inhibition of mild steel corrosion in acid solution by Pheniramine drug: experimental and theoretical study. Corros. Sci. 2010, 52, 3033–3041. 10.1016/j.corsci.2010.05.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. A.; Holifield P. K.; Looney J. R.; McDougall L. A.. Inhibited Acid System for Acidizing Wells, in: US Patent 5, 209, 859, Exxon Chemical Patents, Inc.: Linden, N.J., 1993.

- Fawzy A.; Abdallah M.; Alfakeer M.; Ali H. M. Corrosion inhibition of Sabic iron in different media using synthesized sodium N-dodecyl arginine surfactant. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2019, 14, 2063–2084. [Google Scholar]

- Hazazi O. A.; Fawzy A.; Shaaban M. R.; Awad M. I. Enhanced 4-amino-5-methyl-4H-1,2,4-triazole-3-thiol inhibition of corrosion of mild steel in 0.5 M H2SO4 by Cu(II). Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2014, 9, 1378–1389. [Google Scholar]

- a Abdallah M.; Fawzy A.; Al Bahir A. The effect of expired acyclovir and omeprazole drugs on the inhibition of Sabic iron corrosion in HCl solution. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2020, 15, 4739–4753. 10.20964/2020.05.86. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Abdallah M.; Fawzy A.; Al Bahir A. Amoxicillin and cefuroxime expired drugs as efficient anticorrosive for Sabic iron in 1.0 M hydrochloric acid solution. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2020, 1852220. [Google Scholar]

- Hazazi O. A.; Fawzy A.; Awad M. I. Synergistic effect of halides on the corrosion inhibition of mild steel in H2SO4 by a triazole derivative: Kinetics and thermodynamic studies. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2014, 9, 4086–4103. [Google Scholar]

- Fawzy A.; Zaafarany I. A.; Ali H. M.; Abdallah M. New synthesized amino acids-based Surfactants as efficient inhibitors for corrosion of mild steel in hydrochloric acid medium: Kinetics and thermodynamic approach. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2018, 13, 4575–4600. [Google Scholar]

- Hazazi O. A.; Fawzy A.; Awad M. I. Sulfachloropyridazine as an eco-friendly inhibitor for corrosion of mild steel in H2SO4 solution. Chem. Sci. Rev. Lett. 2015, 4, 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Assaf F.; Abou-Krisha M.; Yousef T. A.; Abushoffa A.; El-Sheref F.; Toghan A. Influence of current density on the mechanism of electrodeposition and dissolution of Zn–Fe–Co alloys. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. 2020, 94, 1708–1715. 10.1134/S0036024420080026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abou-Krisha M. M.; Assaf F. H.; Toghan A. A. Electrodeposition of Zn–Ni alloys from sulfate bath. Solid State Electrochem. 2007, 11, 244–252. [Google Scholar]

- Fawzy A.; El-Ghamry H. A.; Farghaly T. A.; Bawazeer T. M. Investigation of the inhibition efficiencies of novel synthesized cobalt complexes of 1,3,4-thiadiazolethiosemicarbazone derivatives for the acidic corrosion of carbon steel. J. Mol. Str. 2019, 1203, 127447. [Google Scholar]

- Bawazeer T. M.; El-Ghamry H. A.; Farghaly T. A.; Fawzy A. Novel 1,3,4-thiadiazolethiosemicarbazones derivatives and their divalent cobalt complexes: Synthesis, characterization and their efficiencies for acidic corrosion inhibition of carbon steel. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2020, 30, 1609–1620. 10.1007/s10904-019-01308-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alfakeer M.; Abdallah M.; Fawzy A. Corrosion inhibition effect of expired ampicillin and flucloxacillin drugs for mild steel in aqueous acidic medium. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2020, 15, 3283–3297. [Google Scholar]

- Heikal M.; Ali A.; Ibrahim B.; Toghan A. Electrochemical and physico-mechanical characterizations of fly ash-composite cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 243, 118309 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fawzy A.; Abdallah M.; Zaafarany I. A.; Ahmed S. A.; Althagafi I. I. Thermodynamic, kinetic and mechanistic approach to the corrosion inhibition of carbon steel by new synthesized amino acids-based surfactants as green inhibitors in neutral and alkaline aqueous media. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 265, 276–291. 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.05.140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah M.; Fawzy A.; Hawsawi H. Maltodextrin and chitosan polymers as inhibitors for the corrosion of carbon steel in 10 M hydrochloric acid. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2020, 15, 5650–5663. [Google Scholar]

- Fawzy A.; Farghaly T.; Al Bahir A. A.; Hameed A. M.; El-Harbi A.; El-Ossaily Y. A. Investigation of three synthesized propane bis-oxoindoline derivatives as inhibitors for the corrosion of mild steel in sulfuric acid solutions. J. Mol. Str. 2021, 1223, 129318 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang Y.; Guo L.; Li H.; Lan X. Fabrication of environmentally friendly Losartan potassium film for corrosion inhibition of mild steel in HCl medium. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 15, 126863. [Google Scholar]

- Qiang Y.; Zhang S.; Wang L. Understanding the adsorption and anticorrosive mechanism of DNA inhibitor for copper in sulfuric acid. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 492, 228–238. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.06.190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang Y.; Guo L.; Li H.; Lan X. Self-assembling anchored film basing on two tetrazole derivatives for application to protect copper in sulfuric acid environment. J. Mat. Sci. Technol. 2020, 52, 63–71. 10.1016/j.jmst.2020.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fouda A. S.; Mostafa H. A.; El-Ewady Y. A.; El-Hashemy M. A. Low molecular weight straight-chain diamines as corrosion inhibitors for SS type 304 in HCl solution. J. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2008, 195, 934–947. 10.1080/00986440801905148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Letourneau D.; Krog N. The use of chromotropic acid for the quantitative determination of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. Plant Physiol. 1952, 27, 822–827. 10.1104/pp.27.4.822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Thickett D.; Green L. Two tests for the detection of volatile organic acids and formaldehyde. J. Am. Inst. Conservation 2013, 33, 47–53. 10.1179/019713694806066446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palanisamy K.; Kannan P.; Sekar A. Evaluation of chromotrope FB dye as corrosion inhibitor using electrochemical and theoretical studies for acid cleaning process of petroleum pipeline. Surf. Interf. 2018, 12, 50–60. 10.1016/j.surfin.2018.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mabrouk E. M.; Eid S.; Attia M. M. Corrosion inhibition of carbon steel in acidic medium using azo chromotropic acid dye compound. J. Basic Env. Sci. 2017, 4, 351. [Google Scholar]

- Mu G. N.; Li X. H.; Qu Q.; Zhou J. Molybdate and tungstate as corrosion inhibitors for cold rolling steel in hydrochloric acid solution. Corros. Sci. 2006, 48, 445–459. 10.1016/j.corsci.2005.01.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bessone J. C.; Mayer K.; Tuttner W.; Lorenz J. AC-impedance measurements on aluminium barrier type oxide films. Electrochim. Acta 1983, 28, 171–175. 10.1016/0013-4686(83)85105-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reis F. M.; De Melo H. G.; Costa I. EIS investigation on Al 5052 alloy surface preparation for self-assembling monolayer. Electrochim. Acta 2006, 51, 1780–1788. 10.1016/j.electacta.2005.02.118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muhsen A. M.; El-Haddad A.; Radwan B.; Sliem M. H.; Hassan W. M. I.; Abdullah A. M. Highly efficient eco-friendly corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in 5 M HCl at elevated temperatures: experimental & molecular dynamics study. Sci. Reports 2019, 9, 3695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayed S. Y.; El-Deab M. S.; El-Anadouli B. E.; Ateya B. G. Synergistic effects of benzotriazole and copper ions on the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and corrosion behavior of iron in sulfuric acid. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 5575. 10.1021/jp034334x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C.; Mansfeld F. Concerning the conversion of the constant phase element parameter Y0 into a capacitance. Corrosion 2001, 57, 747–748. 10.5006/1.3280607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B.; Liu Y.; Yin X.; Yang W.; Chen Y. Experimental and theoretical study of corrosion inhibition of 3-pyridinecarbozalde thiosemicarbazone for mild steel in hydrochloric acid. Corros. Sci. 2013, 74, 206–213. 10.1016/j.corsci.2013.04.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oguzie E. E.; Unaegbu C.; Ogukwe C. N.; Okolue B. N.; Onuchukwu A. I. Inhibition of mild steel corrosion in sulphuric acid using indigo dye and synergistic halide additives. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2004, 84, 363–368. 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2003.11.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyaraj T.; Raja C.; Paramasivam M.; Jayapriya B. Inhibition of Corrosion of Mild Steel in 10% Sulfamic Acid by Azo Dyes. Trans. SAEST 2005, 40, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar V.; Velumani K.; Rameshkumar S. Colocid Dye - A Potential Corrosion Inhibitor for the Corrosion of Mild Steel in Acid Media, Mat. Res. vol.21 no.4 São Carlos. Epub May 2018, 21, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ma X.; Wang J.; Xu J.; Jing J.; Li J.; Zhu H.; Yu S.; Hu Z. Sunflower head pectin with different molecular weights as promising green corrosion inhibitors of carbon steel in hydrochloric acid solution. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 21148–21160. 10.1021/acsomega.9b02570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang Y.; Zhang S.; Tan B.; Chen S. Evaluation of Ginkgo leaf extract as an eco-friendly corrosion inhibitor of X70 steel in HCl solution. Corros. Sci. 2018, 133, 6–16. 10.1016/j.corsci.2018.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang Y.; Zhang S.; Guo L.; Zheng X.; Xiang B.; Chen B. Experimental and theoretical studies of four allyl imidazolium-based ionic liquids as green inhibitors for copper corrosion in sulfuric acid. Corros. Sci. 2017, 119, 68–78. 10.1016/j.corsci.2017.02.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christov M.; Popova A. Adsorption characteristics of corrosion inhibitors from corrosion rate measurements. Corros. Sci. 2004, 46, 1613–1620. 10.1016/j.corsci.2003.10.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla S. K.; Quraishi M. A. Cefotaxime sodium: A new and efficient corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in hydrochloric acid solution. Corros. Sci. 2009, 51, 1007–1011. 10.1016/j.corsci.2009.02.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behpour M.; Ghoreishi S. M.; Soltani N.; Salavati-Niasari M.; Hamadanian M.; Gandomi A. Electrochemical and theoretical investigation on the corrosion inhibition of mild steel by thiosalicylaldehyde derivatives in hydrochloric acid solution. Corros. Sci. 2008, 50, 2172–2181. 10.1016/j.corsci.2008.06.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao T. P.; Mu G. N. The adsorption and corrosion inhibition of anion surfactants on aluminium surface in hydrochloric acid. Corros. Sci. 1999, 41, 1937–1944. 10.1016/S0010-938X(99)00029-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bentiss F.; Traisnel M.; Lagrenee M. The substituted 1,3,4-oxadiazoles: a new class of corrosion inhibitors of mild steel in acidic media. Corros. Sci. 2000, 42, 127–146. 10.1016/S0010-938X(99)00049-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khaled K. F. Evaluation of electrochemical frequency modulation as a new technique for monitoring corrosion and corrosion inhibition of carbon steel in perchloric acid using hydrazine carbodithioic acid derivatives. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2009, 39, 429–438. 10.1007/s10800-008-9688-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durnie W.; Marco R. D.; Jefferson A.; Kinsella B. Development of a structure-activity relationship for oil field corrosion inhibitors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1999, 146, 1751–1756. 10.1149/1.1391837. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elachouri M.; Hajji M. S.; Salem M.; Kertit S.; Aride J.; Coudert R.; Essassi E. Some nonionic surfactants as inhibitors of the corrosion of iron in acid chloride solutions. Corrosion 1996, 52, 103–108. 10.5006/1.3292100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bockris J. O. M.; Reddy A. K. N.; Modern Electrochemistry, vol. 2, Plenum Press, New York, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh J.Advanced Organic Chemistry, 3rd Ed, Wiley, Eastern New Delhi, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Rubaye A.; Abdulwahid A.; Al-Baghdadi S. B.; Al-Amiery A.; Kadhum A.; Mohamad A. Cheery sticks plant extract as a green corrosion inhibitor complemented with LC-EIS/MS spectroscopy. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2015, 10, 8200–8209. [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah M.; Fawzy A.; Hawsawi H.; Hameed R. S. A.; Al-Juaid S. S. Estimation of water-soluble polymeric materials (Poloxamer and Pectin) as corrosion inhibitors for carbon steel in acidic medium. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2020, 15, 8129–2144. [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah M.; Hazazi O. A.; Fawzy A.; El-Shafei S.; Fouda A. S. Influence of N-thiazolyl-2-cyanoacetamide derivatives on the corrosion of aluminum in 0.01M sodium hydroxide. Prot. Met. Phys. Chem. Surf. 2014, 50, 659–666. 10.1134/S2070205114050025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jr., A. S . Molecular Orbital Theory for Organic Chemists, John Wiley and Sons Inc., New York, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Benahmed M.; Djeddi N.; Akkal S.; Laouer H. Saccocalyx satureioides as corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel in acid solution. Int. J. Ind. Chem. 2016, 7, 109–120. 10.1007/s40090-016-0082-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Deng S.; Fu H. Triazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide as a novel corrosion inhibitor for steel in HCl and H2SO4 solutions. Corros. Sci. 2011, 53, 302–309. 10.1016/j.corsci.2010.09.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Issaadi S.; Douadi T.; Zouaoui A.; Chafaa S.; Khan M. A.; Bouet G. Novel thiophene symmetrical Schif base compounds as corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic media. Corros. Sci. 2011, 53, 1484–1488. 10.1016/j.corsci.2011.01.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu l.; Xiong y.; Chen S.; Long Y. Trace copper ion detection by the suppressed decolorization of chromotrope 2R complex. Anal. Methods 2015, 7, 266–270. 10.1039/C4AY02414A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bockris J. O.; Swinkels D. A. J. Adsorption of n-decylamine on solid metal electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1964, 11, 736–744. [Google Scholar]

- Dean S. W.; Grab G. D. Corrosion of carbon steel by concentrated sulfuric acid. Mater. Perform. 2012, 58, 1–11. 10.1016/j.corsci.2012.01.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manjula P.; Manonmani S.; Jayaram P.; Rajendran S. Corrosion behaviour of carbon steel in the presence of N-cetyl-N,N,N-trimethylammonium bromide, Zn2+ and calcium gluconate. Anti-Corros. Methods Mater. 2001, 48, 319–324. 10.1108/EUM0000000005883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H.; Chen S.; Niu L.; Zhao S.; Li S.; Li D. Inhibition of copper corrosion by several Schiff bases in aerated halide solutions. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2002, 32, 65–72. 10.1023/A:1014242112512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L. B.; Mu G. N.; Liu G. H. The effect of neutral red on the corrosion inhibition of cold rolled steel in 1.0 M hydrochloric acid. Corros. Sci. 2003, 45, 2251–2262. 10.1016/S0010-938X(03)00046-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]