Abstract

Helicobacter pylori was first isolated from gastritis patients by Barry J. Marshall and J. Robin Warren in 1982, and more than 90% of duodenal ulcers and about 80% of gastric ulcers are caused by H. pylori infection. Most detection methods require sophisticated instruments and professional operators, making detection slow and expensive. Therefore, it is critical to develop a simple, fast, highly specific, and practical strategy for the detection of H. pylori. In this study, we used H. pylori as a target to select unique aptamers that can be used for the detection of H. pylori. In our study, we used random ssDNA as an initial library to screen nucleic acid aptamers for H. pylori. We used binding rate and the fluorescence intensity to identify candidate aptamers. One DNA aptamer, named HPA-2, was discovered through six rounds of positive selection and three rounds of negative selection, and it had the highest affinity constant of all aptamers tested (Kd = 19.3 ± 3.2 nM). This aptamer could be used to detect H. pylori and showed no specificity for other bacteria. Moreover, we developed a new sensor to detect H. pylori with the naked eye for 5 min using illumination from a hand-held flashlight. Our study provides a framework for the development of other aptamer-based methods for the rapid detection of pathogenic bacteria.

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori was first isolated from gastritis patients by Barry J. Marshall and J. Robin Warren in 1982.1H. pylori is a Gram-negative, unipolar, multiflagellate, microaerophilic pathogenic bacterium that lives in various areas of the stomach and duodenum.2,3 Generally speaking, H. pylori exhibits a typical spiral or curved shape on the surface of gastric mucosal epithelial cells and is 2.5–4.0 μm in length and 0.5–1.0 μm diameter based on biopsy specimen observation.1,4,5 The original spiral, however, fades over time and the bacterium tends to form rod-like or coccoid forms when cultured in vitro.5,6H. pylori is extremely harmful to humans. In developing countries, 70–90% of the population carries H. pylori.5 Numerous studies have shown that more than 90% of duodenal ulcers and about 80% of gastric ulcers are caused by H. pylori infection.7,8 This bacterium can cause mild chronic inflammation of the gastric mucosa,9,10 stomach and duodenal ulcers,11−13 and even stomach cancer.14−17

Various methods have been developed for the diagnosis of H. pylori infection, including those using bacteriology, genomics, isotope tracing, pathology, serology, and molecular biology.18−28 In general, from the perspective of specimen collection, these methods can be divided into two categories: invasive and noninvasive.29,30 The invasive methods mainly focus on methods of taking a biopsy specimen examination through a gastroscope, which is a conventional method of the digestive disease discipline. These methods include isolation and culture of bacteria and direct smear, rapid urease tests, or drug susceptibility test.31−35 Noninvasive methods mainly utilize methods of diagnosing infection of H. pylori specimens without biopsy specimen harvest by gastroscopy, such methods include antibody detection, antigen detection, and urea 13C/14C breath test.36−40 Although these methods are effective for H. pylori detection, most of them require sophisticated instruments and professional operators, which immensely limit early detection and preventative health, causing fateful consequences and economic losses. Therefore, it is critical to develop a simple, fast, highly specific, and practical strategy for the detection of H. pylori.41

Aptamers are single-stranded functionalized nucleic acids selected by in vitro systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) screening.42 Their tendency to form three-dimensional structures with target specificity makes them attractive as new potential molecular receptors.43,44 Compared to antibodies, aptamers possess multiple advantages, such as low molecular weight, nonimmunogenicity, good stability, easy synthesis, extensive target, and high specificity and affinity.45−47 Based on these excellent features, aptamers have become vital tools in many fields, such as immune diagnosis, pharmacology, biosensors, and nanomaterials.48−52 In particular, the emergence of new nucleic acid drugs allowed treatments that lack the harmful side effects of more traditional drugs,53−55 providing a new research platform for human health and the treatment of diseases such as cancer.

Although many aptamers had been designed for H. pylori detection, most of them were results of one-fold selection or combination with other medium. In this study, we explored aptamer binding using whole-cell selection with H. pylori and established a new fluorescence method for detecting H. pylori using HPA-2 aptamers as tools. H. pylori and HPA-2-labeled probes bound competitively, allowing rapid detection. Our research further deepens an understanding of the interaction between aptamers and H. pylori. Moreover, our data provide a theoretical basis for the development of new nucleic acid drugs, diagnosis, and treatment of bacterial diseases. We also present an aptamer-based fluorescent sensor for H. pylori.

Results and Discussion

Scanning Electron Microscopy Imaging of H. pylori

Due to the variability of H. pylori morphology, we performed a comparison of H. pylori to observe the cell-to-cell variation in different culture periods using an analytical scanning electron microscope (Jeol, Japan). As shown in Figure S1, the original spiral form gradually fades and tends toward a rod-like shape in the first culture (A). When continued to a second or third culture, H. pylori transformed into an oval shape (B and C), and it appeared as a spherical form after all subsequent cultures (D). These morphological changes were consistent with the report of Bruce E. Dunn in 1997.5

In Vitro Aptamer Selection Using SELEX

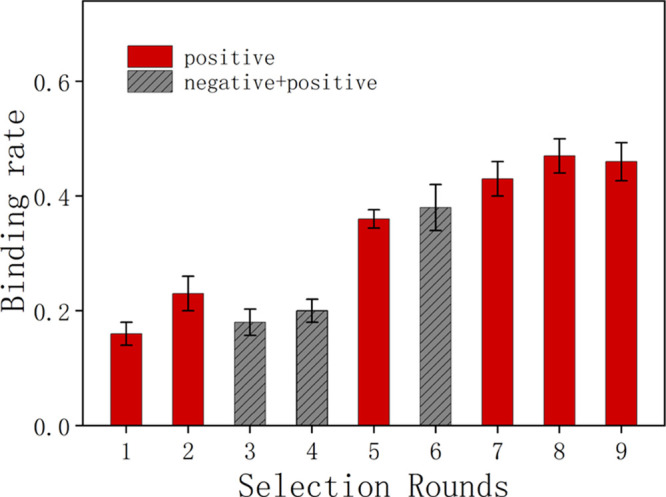

Next, H. pylori cells were used as a target to finish SELEX selection and to obtain high-affinity aptamers that could bind to H. pylori. In total, eight rounds of positive selection and three rounds of negative selection were carried out. Prior to incubation with H. pylori, the fluorescence intensity of ssDNA was measured. Synchronously, the fluorescence intensity of the eluted DNA (after incubation and washing) was also monitored. As shown in Figure 1, the binding rates gradually increased as the number of rounds of positive selection increased with the exception of the third and fourth rounds, where negative selection was introduced to remove nonspecific or weak binding sequences. The sixth round was also a negative selection round, but the fluorescence intensity did not decrease after this round. This indicated that the nonspecific or weak binding sequences had been eliminated. After the eighth round of selection, the binding rate reached a plateau. This information suggested that all cells were saturated with candidate aptamers, and all binding sites on the target bacteria had been occupied.56

Figure 1.

Comparison of binding rates for each round of SELEX selection.

Sequence Analysis

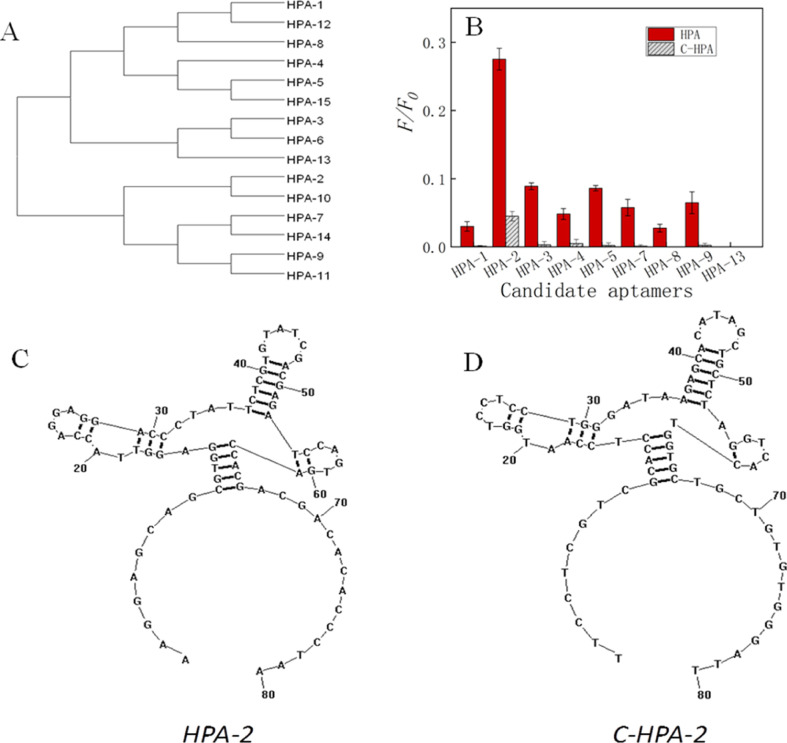

We next carried out high-throughput sequencing of the ninth round PCR product (Sangon, China) and obtained 15 candidate aptamers, which we named based on their proportions in all sequences (Table 1). First, we performed a similarity analysis of these sequences using Clustal software and found that these DNAs could be divided into two large groups (Figure 2A). HPA-1, HPA-3 to HPA-6, HPA-8, HPA-12, HPA-13, and HPA-15 belonged to the first group, and the other sequences were assigned to the second group. In these two large clusters, nine small branches were further identified. In order to seek the ideal aptamer for H. pylori, we focused on the first sequence in each embranchment (total 9). These sequences were synthesized by Sangon (Shanghai, China) and an FAM label (carboxyfluorescein) was fixed on their 5′ ends. Following this, we analyzed their binding capacity to H. pylori cells and found that HPA-2, HPA-3, HPA-5, and HPA-9 had higher binding ability to H. pylori cells than others from this clade (Figure 2B, HPA), and the binding ability order was HPA-2 > HPA-3 > HPA-5 > HPA-9. Due to the use of conventional PCR, we hypothesized that the complementary sequences of these candidate aptamer DNA sequences may also have binding ability, so we also analyzed the binding ability of these complementary sequences to H. pylori (Figure 2B, C-HPA) and their secondary structures. The results showed that both HPA-2 and C-HPA-2 had relatively high binding abilities to H. pylori cells. Even though the secondary structures revealed that these DNA sequences all had similar domains which probably acted as the core function for aptamer binding,57,58 the binding capacity of C-HPA-2 was much lower than that of HPA-2 (Figure 2C,D), which indicated that HPA-2 was the ideal aptamer for H. pylori from this screen.

Table 1. DNA Sequences of Selected Aptamer Candidates.

| name | sequences (5′–3′) | numbers | percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPA-1 | CGCCTGATCCAGGTGCTATCTTCCGCCCTGTTTCTTTGGT | 3094 | 4.84 |

| HPA-2 | CCAGGAGGACCCTATTCTCGTGTATCGACGAGATCCAGTG | 2759 | 4.31 |

| HPA-3 | CTCCTCGGTCCTTTCAGGTAGACGCTCTTACGCCCTCAGT | 1757 | 2.75 |

| HPA-4 | CGTGTATCCCCTGTGTGTTTGTACTCGGCTACTGTATCCG | 1699 | 2.66 |

| HPA-5 | CTCGTTTGGATACGTCATCGGTAGGACTACGGTACCTAAAC | 1438 | 2.25 |

| HPA-6 | GCACAGGAGACAGGGGGAGATGATACTCGGCGTTTCAAGG | 1376 | 2.15 |

| HPA-7 | CTCGCGCCCTTCTTTCAGTAGCAGTGTACGGATCTTGCGG | 1262 | 1.97 |

| HPA-8 | TGCATATCGCTAGCTGATAAGCTGATGCCATCGTGTCTAC | 1143 | 1.79 |

| HPA-9 | GCATCTTTGAGGAATTTTCGTCAAAGGACCGAGTAACGGC | 1034 | 1.62 |

| HPA-10 | AGTTGCTCTTGATCGTCGACCAGTCGCTATGCAGCACCCC | 861 | 1.35 |

| HPA-11 | CTGCACGAATGATCCCCCGCCATGCTGTAGTTCCGTCTTA | 664 | 1.04 |

| HPA-12 | CTGTAACGCCCCGCTGATTCTTTCTCAGCGTGCTAGGCGG | 468 | 0.73 |

| HPA-13 | ATCGCTCCGTCCAGTAAGAGTTGCCTACAATGCCCGCCGGC | 445 | 0.7 |

| HPA-14 | CAAATGAGCCTTAGAGCTGTGCAGAGTTCGAAGCTTGGTG | 250 | 0.39 |

| HPA-15 | CCTCGGTGTTCGTTCTGACTACGTTCCCTGGGACCCGCGT | 179 | 0.28 |

Figure 2.

(A) Similarity analysis of DNA sequences by cluster. (B) Binding rate comparison of each candidate aptamer to H. pylori cells. (C) Secondary structure of HPA-2 and (D) C-HPA-2.

Affinity Analysis and Specificity

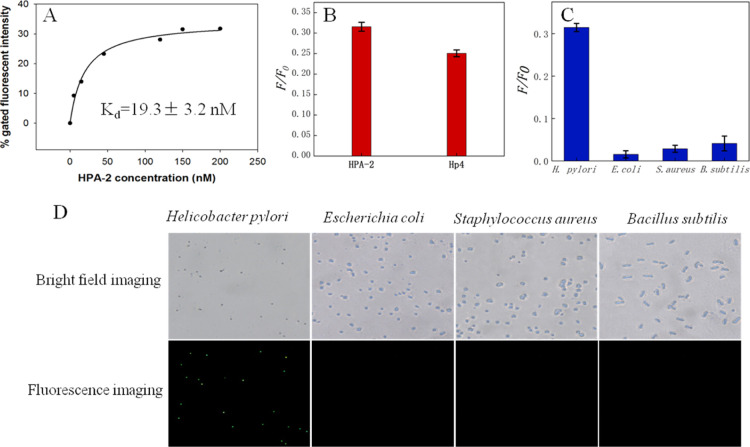

We then measured the binding affinities of HPA-2 to H. pylori under the same conditions using different concentrations of HPA-2 (final concentrations of 0, 5, 15, 45, 120, 150, and 200 nM, respectively). The affinity of HPA-2 at various concentrations was plotted with Sigma plot 12.5. The curve fitting results showed that HPA-2 had a good binding affinity for H. pylori, and the maximum dissociation constant (Kd) was 19.3 ± 3.2 nM (Figure 3A). Therefore, we selected HPA-2 for all follow-up experiments after analyzing the binding rate and affinity of two aptamers, HPA-2 and Hp4. The binding rate of HPA-2 to H. pylori was higher than that of Hp4 to H. pylori (Figure 3B). The Kd of HPA-2 was 19.3 ± 3.2 nM, and the Kd of Hp4 was 26.48 ± 5.72 nM. The Kd of both is not significantly different. Through the abovementioned analysis, the incubation effect of HPA-2 and H. pylori was better than that of Hp4. Good aptamers must have high specificity,59 so to characterize the specificity of HPA-2, we tested it with a variety of other bacteria, including Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, and Escherichia coli. As shown in Figure 3C,D, the intensity of the fluorescence with H. pylori was higher than that using other control bacteria. Fluorescence microscopic examination showed that HPA-2 bound more H. pylori sequences than other bacterial sequences. Thus, the selected aptamer had excellent target specificity.

Figure 3.

(A) Saturation curve of aptamer HPA-2. (B) Binding rate of HPA-2 and Hp4 at the same concentration (200 nM) relative to H. pylori. (C) Specificity of HPA-2 to different bacterial species. (D) Fluorescence microscopy images showing HPA-2 after incubation with different bacteria (magnification 400×).

Rapid Detection of H. pylori

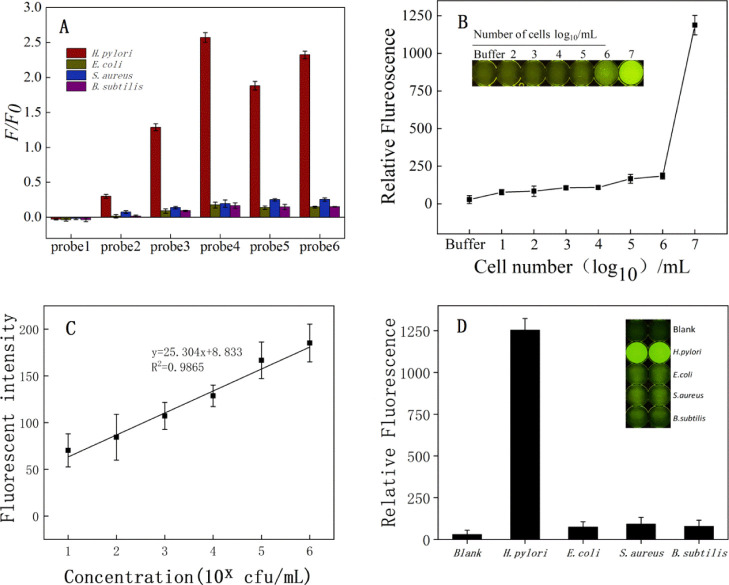

Compared to six conventional probes, the fluorescence intensity of the target bacteria was significantly higher than other bacteria, indicating that our detection method could feasibly detect H. pylori (Figure 4A). Probe 4 was preferred, due to the larger HPA-2-binding-induced fluorescence change and relatively good binding affinity. Considering its superior detection results, we chose probe 4 as the optimal probe and then optimized experimental conditions.60

Figure 4.

(A) Determination of the optimal probe sequence. (B) LOD of H. pylori. (C) Graph showing the linear relationship between fluorescence intensity and H. pylori concentration. In the equation, x represents the dilution exponent (x = 1–6). (D) Specificity test for H. pylori. The other tested bacteria included E. coli, S. aureus, and B. subtilis.

H. pylori-treated microregions produced a strong fluorescent signal, while controls treated with reaction buffers were weaker. The fluorescence signal of H. pylori-treated microdomains was at least five times higher than the fluorescence signal of buffered microdomains. We also investigated the sensitivity of the competitive detection using different concentrations of H. pylori (0–107 cfu/mL) (Figure 4B). We incubated HPA-2 with different concentrations of H. pylori and determined the fluorescence signal to detect the sensitivity of HPA-2 to H. pylori. The limit of detection (LOD) of HPA-2 was 88 cfu/mL (Figure 4C). To test the specificity of aptamer competitive combination, we assessed three other kinds of bacteria (Figure 4D). The addition of H. pylori caused a significant increase in fluorescence intensity. The fluorescence intensity did not significantly change when other bacteria were tested. This result suggested that the other tested bacteria did not interfere with H. pylori detection. In addition, the presence of E. coli, S. aureus, or B. subtilis in our H. pylori samples did not interfere with the detection of H. pylori. Our results showed that our assay was specific for H. pylori. Thus, this aptamer was ready for studies on the feasibility of application to clinical samples.61

Food Inspection

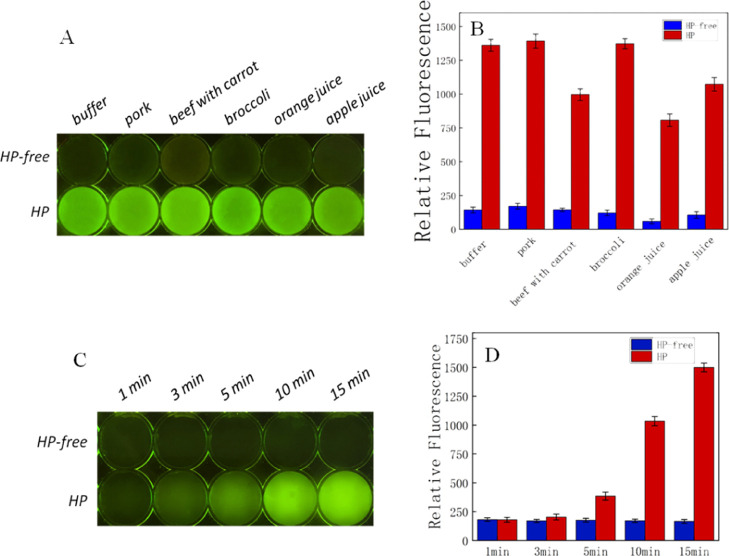

As shown in Figure 5, the results using our aptamer-based assay could be observed clearly by the naked eye. The area of H. pylori was bright, while in contrast, the area lacking H. pylori was dark. The fluorescence also demonstrated that our sensors were reliable. F/F0 indicates a positive fluorescent signal divided by the negative. The F/F0 of blank, pork, beef with carrot, broccoli, orange juice, and apple juice was 9.6, 8.2, 6.9, 11.3, 13.8, and 10.2, respectively. According to our sensor reaction over time, results could be achieved within 5 min. The F/F0 of different times with a pork sample was 1.2 (3 min), 2.2 (5 min), 6.1 (10 min), and 9.1 (15 min) (Figure 5). This was similar to our apple juice sample (Figure S2). Our results verified that these sensors could be used to screen food samples for H. pylori. Thus, this biosensor for H. pylori had a promising application prospect. The stability of the biosensor formed by aptamers will be focused next. Chemical modifications of aptamers or aptamer conjugation to nanomaterials may be chose to increase their stability.62,63

Figure 5.

Detection of H. pylori with: (A) sensor for food inspection; (B) fluorescence measurements; (C) sensor reaction over time; and (D) fluorescence measurements (HP-free: H. pylori-free, HP: H. pylori-added).

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

PCR master mix, low-weight DNA ladders, and gel-red (10,000×) were from BBI (BBI Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China); 6× gel loading dye was purchased from New England Biolabs, MA, America. Sterile defibrillated sheep blood was purchased from Nanjing Maojie Microbiology Technology Co., Ltd (Nanjing, China). Tryptone and yeast extract were purchased from OXOID (England). Soya peptone was purchased from AoBox (Beijing, China). Agar powder was purchased from Solarbio (Beijing, China). Peptone from fish, urea, Tween-20, MgCl2, KCl, NaHCO3, Na2CO3, and NaH2PO4 were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). NaCl, Na2HPO4, EDTA·2Na, and boric acid were purchased from Nanjing Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). Agarose was purchased from BIOWEST, France. Ammonium persulfate, tetramethylethylenediamine, acrylamide, and Tris were purchased from Aladdin (Beijing, China). All solutions were prepared using ultrapure water with an electric resistance >18.20 MΩ·cm, which was obtained using a Bamstead Labtower EDI water purification system (Thermo, Germany).

Bacteria and DNA Libraries

H. pylori were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, USA). Vibrio anguillarum, Vibrio Vulnificus, and V. parahaemolyticus were purchased from the China Center of Industrial Culture Collection (CICC, China). E. coli, B. subtilis, and S. aureus were provided by Jiangsu Marine Resources Development Research Institute (Lianyungang, China). Single-stranded DNA oligonucleotide libraries and candidate aptamers were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China).

Preparation of Bacteria

According to the product instructions of H. pylori (ATCC 43504), the medium for H. pylori growth was composed of ATCC medium 18 (tryptic soy broth) and ATCC medium 260 (tryptic soy agar with 5% defibrinated sheep blood). ATCC medium 18 recipe: tryptone 17 g, soytone 3 g, dextrose 2.5 g, NaCl 5 g, K2HPO4 2.5 g, DI water 1 L, final pH 7.3 ± 0.2, was autoclaved at 121 °C for 20 min. ATCC medium 260 recipe: tryptone 15 g, soytone 5 g, NaCl 5 g, agar 15 g, DI water 950 mL, final pH 7.3 ± 0.2, was autoclaved at 121 °C for 20 min and the medium was cold-sterilized to ∼47 °C. A total of 50 mL of room-temperature defibrinated sheep blood was aseptically added. Then, the mixture was gently mixed and dispensed as required. In order to obtain good growth of H. pylori, a biphasic culture was established between ATCC medium 18 and ATCC medium 260, and H. pylori growth at the broth/agar interface of the biphasic slant occurred within 3–4 days. The growth conditions were as follows: 37 °C, microaerophilic, 3–5% O2 ∼10% CO2. To observe growth, a wet mount from the broth was examined using phase microscopy. This organism displays motile tiny-corkscrew rod arranged singles. Other control bacteria were cultivated according to their growth conditions until the optical density (OD600) of the broth was approximately 1 (Infinite M1000 Pro, Tecan, Switzerland).

In Vitro Selection

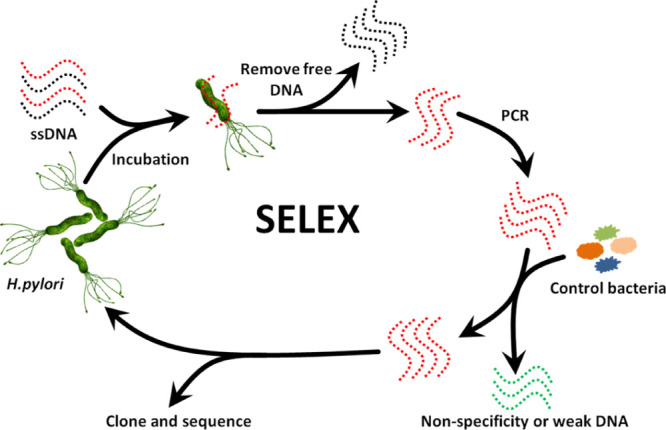

An initial library with a length of 80 nts was chosen for selection, and 40 random nucleotides (A, T, G, and C) were inserted in the center and flanked by two fixed sequences used for PCR amplification (5′-AAGGAGCAGCGTGGAGGTTA-N40-ACCACGACGACACACCCTAA-3′). The forward primer was 5′-AAGGAGCAGCGTGGAGGTTA-3′ (P1) and the reverse primer was 5′-TTAGGGTGTGTCGTCGTGGT-3′ (P2). All oligonucleotides were purified by 10% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and extracted from the gel with DNA elution buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5). The extracted DNA library was further concentrated via ethanol precipitation. The final concentration was 600 pM (100 μL), and the purified initial library was denatured at 95 °C for 5 min and immediately cooled with ice for 10 min. H. pylori cells were washed with 200 μL of selection buffer (100 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 50 mM Tris–HCl, and 1 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5) followed by centrifugation at 5000 g for 5 min. Then, the precipitate was resuspended in 100 μL of selection buffer. Next, single-stranded DNA (annealed) was mixed with the resuspended precipitate solution and incubated for 60 min at 30 °C on a thermomixer (Eppendorf, Germany) at 120 rpm to promote complexes. After binding, the mixture solution was centrifuged at 5000 g for 5 min to remove unbound ssDNA. The precipitate was rinsed three times with selection buffer to remove weakly binding ssDNA and the precipitate was then resuspended in 100 μL of ultrapure water. Suspensions were incubated at 95 °C for 5 min, placed on ice for 10 min, and centrifuged at 12,000g for 10 min. The supernatant was recovered and purified using ethanol precipitation with glycogen as a carrier. The purified ssDNA was next dissolved in 40 μL of ultrapure water and used as templates for PCR amplification. PCR products were analyzed using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis (stained with gel-red) and visualized using a Bio-Rad GelDoc EZ imager (Bio-Rad, USA). All the residual PCR products were purified by ethanol precipitation. The purified ssDNA was used for subsequent rounds of selection. During the negative selection process, the mixtures of six strains were used as a negative selection to incubate with PCR products. The unbound DNA was retained and used to incubate with H. pylori. After all SELEX rounds were completed, the last round PCR products were chosen for NGS sequencing (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of aptamer selection for H. pylori based on SELEX.

Sequencing and Analysis

In order to obtain high-specificity aptamers for H. pylori, nine cycles of positive selection and three cycles of negative selection were carried out. The selection effect of each round was quantified according to their binding rates (detecting fluorescence intensity before/after incubation). According to the binding rate, the last round product was chosen for sequencing when the rate did not increase. In order to understand the binding characteristics of aptamers and bacteria, the secondary structure of aptamers was analyzed using RNA structure software. A similarity analysis of each sequence was completed using Clustal software.

Affinity Analysis

Candidate DNA aptamers were obtained according to their binding rates to H. pylori, and varying concentrations of DNA aptamers (0, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 30, 50, and 100 nM) were incubated with the same amount of H. pylori cells to further compare the abilities of candidate aptamers. The affinity of aptamers was analyzed. After washing and separating these complexes, the fluorescence intensity was measured using an Infinite M1000 Pro microplate reader. The equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) was analyzed with Sigma Plot 12.5 software using the following equation (ligand binding, one site saturation)

where Y is the average value of fluorescence due to binding with FAM-labeled aptamers. X is considered as the aptamer concentration and Bmax is the maximum binding capacity of a specific aptamer. Naked H. pylori cells (without aptamers) were used as controls, and each concentration has three replicate tests.

Comparison with Aptamer Hp4

Hp4 was an aptamer screened by our laboratory using the H. pylori surface protein HP-Ag as a target.64 The binding rate of Hp4 and HPA-2 was then compared. The two aptamers were incubated with the same number of H. pylori cells at the same concentration (200 nM). After cleaning and separating these complexes, the fluorescence intensity was measured and further analyzed.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Prior to fluorescence microscopic imaging, DNA sequences were incubated with related bacteria. Then, the complex of aptamer bacteria was washed and resuspended in 100 μL of ultrapure water. Next, 5 μL of the resuspended precipitate was smeared on a glass slide for natural drying for immobilization. Finally, the glass slide was placed in an inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX53, Japan), and we compared the combination status using bright-field image and fluorescent imaging.

Rapid Detection of H. pylori

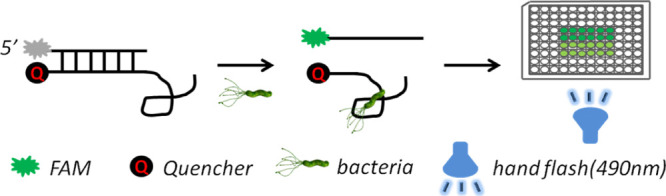

In order to find the optimal probe chain for the HPA-2 aptamer, we designed six different proportions of complementary sequences carrying FAM at the 5′ end as probe strands (Table 2). Figure 7 shows the principle of our aptamer detection assay for H. pylori. Fluorescent (FAM) and black hole quencher1 (BHQ1) were conjugated at the 5′ end of complementary sequences and the 3′ end of one aptamer against HPA-2. The aptamer and the FAM-labeled complementary sequences were annealed at 90 °C to form aptamer complexes, and the fluorescence was quenched. The FAM-labeled complementary sequences and aptamer combined competitively when H. pylori cells were added. If the aptamer bound with H. pylori, drawing an FAM-labeled complementary would separate from BHQ1, and the fluorescence would be released. Detection of H. pylori would thus be achieved by measuring the fluorescence. Moreover, this detection could be performed using the naked eye with illumination from a hand-held flashlight (490 nm).

Table 2. Six Probes in Different Proportions.

| name | proportion (%) | sequences |

|---|---|---|

| probe 1 | 7.5 | 5′-FAM-TTAGGGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′ |

| probe 2 | 10 | 5′-FAM-TTAGGGTGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′ |

| probe 3 | 12.5 | 5′-FAM-TTAGGGTGTGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′ |

| probe 4 | 15 | 5′-FAM-TTAGGGTGTGTCTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′ |

| probe 5 | 18.75 | 5′-FAM-TTAGGGTGTGTCGTCTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′ |

| probe 6 | 25 | 5′-FAM-TTAGGGTGTGTCGTCGTGGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′ |

Figure 7.

Rapid detection of H. pylori based on an aptamer.

Application for Food Inspection

In order to verify the application effect of our sensor, we mixed 1 mL of H. pylori (OD600 = 0.8) with 50 g or mL of meals (cooked pork, cooked beef with carrot, cooked broccoli, orange juice, and apple juice). Then, 30 μL of H. pylori-free and H. pylori-added meal was taken and added to our sensor. The results were observed using a hand-held flashlight (490 nm).

Conclusions

We report here an aptamer for the efficient detection of H. pylori obtained by in vitro selection using SELEX technology. The aptamer was 80 nts long and tightly bound to H. pylori with a Kd of 19.3 ± 3.2 nM. The selected aptamer was further applied to the development of sensors to detect H. pylori. The LOD of HPA-2 was 88 cfu/mL. A new competitive detection method for H. pylori based on HPA-2 was then developed and optimized to detect H. pylori. In food inspection, this sensor could distinguish positive and negative using the naked eye within 5 min. Our results indicated that this sensor could be used to screen food samples. The strategy underpinning our biosensor could be used as a reference for the detection of pathogenic bacteria.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFC0311106), the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD), and the Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu (KYCX19-1021 and JSIMR201926).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c05374.

SEM image for H. pylori and apple juice sample sensor reaction with time and fluorescence measurement (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Warren J. R.; Marshall B. Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet 1983, 1, 1273–1275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazell S. L.Mixed Gastric Infections and Infection with Other Helicobacter Species; Springer Netherlands, 1996; pp 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Miller F. P.; Vandome A. F.; Mcbrewster J.. Muscus, Helicobacter pylori; Alphascript Publishing, 2013; pp 290–294. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin C. S.; Mcculloch R. K.; Armstrong J. A.; Wee S. H. Unusual cellular fatty acids and distinctive ultrastructure in a new spiral bacterium (Campylobacter pyloridis) from the human gastric mucosa. J. Med. Microbiol. 1985, 19, 257–267. 10.1099/00222615-19-2-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn B. E.; Cohen H.; Blaser M. J. Helicobacter pylori. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1997, 10, 720–741. 10.1128/cmr.10.4.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin C. S.; Armstrong J. A. Microbiological aspects of Helicobacter pylori (Campylobacter pylori). Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1990, 9, 1–13. 10.1007/bf01969526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M. C.; Shane G. T.; Yang C. H.; Chen K. Y.. Composition for the Treatment and Prevention of Peptic Ulcer. U.S. Patent 20,080,145,409 A1, 2008; 11, 424–439.

- Vaira D.; Menegatti M.; Miglioli M. What is the role of Helicobacter pylori in complicated ulcer disease?. Gastroenterology 1997, 113, S78–S84. 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)80017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavi J.; Sondén B.; Hurtig M.; Olfat F. O.; Forsberg L.; Roche N.; Ångström J.; Larsson T.; Teneberg S.; Karlsson K. A. Helicobacter pylori SabA Adhesin in Persistent Infection and Chronic Inflammation. Science 2002, 297, 573–578. 10.1126/science.1069076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W.-P.; Hou M.-C.; Lan K.-H.; Li C.-P.; Chao Y.; Lin H.-C.; Lee S.-D. Helicobacter pylori-induced chronic inflammation causes telomere shortening of gastric mucosa by promoting PARP-1-mediated non-homologous end joining of DNA. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016, 606, 90–98. 10.1016/j.abb.2016.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konorev M. R. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori from the stomach and duodenum of patients with duodenal ulcers. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2001, 17, 425–426. 10.1016/s0924-8579(01)00304-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jónsson A.; Martin P.; Rautanen K.; Thomsen A. S.; Hjalt C. A.; Lœfroth G. [The channels for important new knowledge to medical doctors. The case of Helicobacter pylori and stomach and duodenal ulcers.]. Laeknabladid 2001, 87, 707–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovjak P. Ulcus duodeni, Ulcus ventriculi und Helicobacter pylori. Z. Gerontol. 2017, 50, 159–169. 10.1007/s00391-017-1190-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura N.; Okamoto S.; Yamamoto S.; Matsumura N.; Yamaguchi S.; Yamakido M.; Taniyama K.; Sasaki N.; Schlemper R. J. Helicobacter pylori Infection and the Development of Gastric Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 784–789. 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim N.; Park R. Y.; Cho S.-I.; Lim S. H.; Lee K. H.; Lee W.; Kang H. M.; Lee H. S.; Jung H. C.; Song I. S. Helicobacter pylori infection and development of gastric cancer in Korea: long-term follow-up. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2008, 42, 448–454. 10.1097/mcg.0b013e318046eac3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz P.; Valenzuela M. V.; Bravo J.; Quest A. Helicobacter pylori and Gastric Cancer: Adaptive Cellular Mechanisms Involved in Disease Progression. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 5. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung W. K.; Wong I. O. L.; Cheung K. S.; Yeung K. F.; Chan E. W.; Wong A. Y. S.; Chen L.; Wong I. C. K.; Graham D. Y. Effects of Helicobacter PYLORI Treatment on Incidence of Gastric Cancer in Older Individuals. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 67–75. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windsor H. M.; O’Rourke J. Bacteriology And Taxonomy Of Helicobacter Pylori. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2000, 29, 633–648. 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recavarren-Arce S.; León-barúa R.; Cok J.; Berendson R.; Gilman R. H.; Ramírez-Ramos A.; Rodríguez C.; Spira W. M. Helicobacter pylori and progressive gastric pathology that predisposes to gastric cancer. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1991, 26, 51–57. 10.3109/00365529109093208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkitt M. D.; Duckworth C. A.; Williams J. M.; Pritchard D. M. Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric pathology: insights from in vivo and ex vivo models. Dis. Models Mech. 2017, 10, 89–104. 10.1242/dmm.027649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuipers E. J.; Gracia-Casanova M.; Peña A. S.; Pals G.; van Kamp G.; Kok A.; Kurz-Pohlmann E.; Pels N. F. M.; Meuwissen S. G. M. Helicobacter pylori Serology in Patients with Gastric Carcinoma. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1993, 28, 433–437. 10.3109/00365529309098245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafaie E.; Saberi S.; Esmaeili M.; Karimi Z.; Najafi S.; Tashakoripoor M.; Abdirad A.; Hosseini M. E.; Mohagheghi M. A.; Khalaj V.; Mohammadi M. Multiplex serology of Helicobacter pylori antigens in detection of current infection and atrophic gastritis - A simple and cost-efficient method. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 119, 137–144. 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y.; Jicong W. U. ∼ (15)N-urea tracing emission spectroscopy for detecting the infection of Helicobacter pylori. Chin. J. Nuclear Med. 2002, 22, 306–307. [Google Scholar]

- Motta O.; De Caro F.; Quarto F.; Proto A. New FTIR methodology for the evaluation of 13C/12C isotope ratio in Helicobacter pylori infection diagnosis. J. Infect. 2009, 59, 90–94. 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanotti G.; Papinutto E.; Dundon W. G.; Battistutta R.; Seveso M.; Giudice G. D.; Rappuoli R.; Montecucco C. Structure of the Neutrophil-activating Protein from Helicobacter pylori. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 323, 125–130. 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00879-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosford C. J.; Chappie J. S. The crystal structure of the Helicobacter pylori LlaJI.R1 N-terminal domain provides a model for site-specific DNA binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 118–131. 10.1074/jbc.ra118.001888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alikhani M.; Shafaie E.; Mirabzadeh Ardakani E.; Esmaeili M.; Saberi S.; Hatefi M.; Mohammadi M. The Inhibitory Effect of Mouse Gastric DNA on Amplification of Helicobacter pylori Genomic DNA in Quantitative PCR. Iran. Biomed. J. 2019, 23, 297–302. 10.29252/.23.4.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson R.; Thorell K.; Hosseini S.; Kenny D.; Sihlbom C.; Sjöling Å.; Karlsson A.; Nookaew I. Comparative Analysis of Two Helicobacter pylori Strains using Genomics and Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1757–1765. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaira D.; Holton J.; Menegatti M.; Ricci C.; Gatta L.; Geminiani A.; Miglioli M. Invasive and non-invasive tests for Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000, 14, 13–22. 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci C.; Holton J.; Vaira D. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori: invasive and non-invasive tests. Best Pract. Res., Clin. Gastroenterol. 2007, 21, 299–313. 10.1016/j.bpg.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.-C.; Huang T.-C.; Lin C.-L.; Chen K.-Y.; Wang C.-K.; Wu D.-C. Performance of Routine Helicobacter pylori Invasive Tests in Patients with Dyspepsia. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2013, 2013, 184806. 10.1155/2013/184806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mégraud F.; Lehours P. Helicobacter pylori Detection and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 20, 280–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leszczyńska K.; Namiot A.; Namiot Z.; Leszczyńska J. K.; Jakoniuk P.; Chilewicz M.; Namiot D. B.; Kemona A.; Milewski R.; Bucki R. Patient factors affecting culture of Helicobacter pylori isolated from gastric mucosal specimens. Adv. Med. Sci. 2010, 55, 161–166. 10.2478/v10039-010-0028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laine L.; Lewin D.; Naritoku W.; Estrada R.; Cohen H. Prospective comparison of commercially available rapid urease tests for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1996, 44, 523–526. 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou Q. Y.; Yu R. B.; Shi R. H. [Drug susceptibility test guided therapy and novel empirical quadruple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection: a network Meta-analysis]. Chin. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 38, 670–673. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2017.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Püspök A.; Bakos S.; Oberhuber G. A new, non-invasive method for detection of Helicobacter pylori: validity in the routine clinical setting. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1999, 11, 1139–1142. 10.1097/00042737-199910000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara S.; Kaji T.; Kawamura A.; Rumi M. A.; Sato H.; Okuyama T.; Adachi K.; Fukuda R.; Watanabe M.; Hashimoto T.; Hirakawa K.; Matsushima Y.; Chiba T.; Kinoshita Y. Diagnostic accuracy of a new non-invasive enzyme immunoassay for detecting Helicobacter pylori in stools after eradication therapy. Gastroenterology 2000, 14, 611–614. 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamajima N.; Katsuda N.; Matsuo K.; Saito T.; Hirose K.; Inoue M.; Zaki T. T.; Tajima K.; Tominaga S. High anti-Helicobacter pylori antibody seropositivity associated with the combination of IL-8-251TT and IL-10-819TT genotypes. Helicobacter 2003, 8, 105–110. 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2003.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perri F.; Manes G.; Neri M.; Vaira D.; Nardone G. Helicobacter pylori antigen stool test and 13C-urea breath test in patients after eradication treatments. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2002, 97, 2756–2762. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamopoulos A. B.; Stergiou G. S.; Sakizlis G. N.; Tiniakos D. G.; Nasothimiou E. G.; Sioutis D. K.; Achimastos A. D. Diagnostic value of rapid urease test and urea breath test for Helicobacter pylori detection in patients with Billroth II gastrectomy: a prospective controlled trial. Dig. Liver Dis. 2009, 41, 4–8. 10.1016/j.dld.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jehanne Q.; Benejat L.; Megraud F.; Bessède E.; Lehours P. Evaluation of the Allplex H.pylori and ClariR PCR Assay for Helicobacter pylori detection on gastric biopsies. Helicobacter 2020, 25, e12702 10.1111/hel.12702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuerk C.; Gold L. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 1990, 249, 505–510. 10.1126/science.2200121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabar H.DNA Aptamers as a Molecular Probe for Diagnosis and Therapeutic in Cancer Cells, Milad Tower Conference Hall, 2009; Vol. 6, pp 13–15.

- Nutiu R.; Li Y. Structure-Switching Signaling Aptamers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 4771–4778. 10.1021/ja028962o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayasena S. D. Aptamers: an emerging class of molecules that rival antibodies in diagnostics. Clin. Chem. 1999, 45, 1628–1650. 10.1093/clinchem/45.9.1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno J. G. In Vitro Selection of DNA to Chloroaromatics Using Magnetic Microbead-Based Affinity Separation and Fluorescence Detection. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 234, 117–120. 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni S.; Yao H.; Wang L.; Lu J.; Jiang F.; Lu A.; Zhang G. Chemical Modifications of Nucleic Acid Aptamers for Therapeutic Purposes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1683–1703. 10.3390/ijms18081683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Xu D.; Tan W. Aptamer-functionalized nano/micro-materials for clinical diagnosis: isolation, release and bioanalysis of circulating tumor cells. Integrative Biology Quantitative Biosciences from Nano to Macro 2017, 9, 188–205. 10.1039/c6ib00239k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiao Y.-S.; Chiu H.-H.; Wu P.-H.; Huang Y.-F. Aptamer-Functionalized Gold Nanoparticles As Photoresponsive Nanoplatform for Co-Drug Delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 21832–21841. 10.1021/am5026243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. S.; Lee H.-S.; Yang J.-A.; Jo M.-H.; Hahn S. K. The fabrication, characterization and application of aptamer-functionalized Si-nanowire FET biosensors. Nanotechnol 2009, 20, 235501–235506. 10.1088/0957-4484/20/23/235501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.-F.; Shangguan D.; Liu H.; Phillips J. A.; Zhang X.; Chen Y.; Tan W. Molecular assembly of an aptamer-drug conjugate for targeted drug delivery to tumor cells. Chembiochem 2009, 10, 862–868. 10.1002/cbic.200800805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou X.-q.; Wang H.; Zhang J.; Wang F.; Xu G.-l.; Xu C.-c.; Xu H.-h.; Xiang S.-s.; Fu J.; Song H.-f. Aptamer–drug conjugate: targeted delivery of doxorubicin in a HER3 aptamer-functionalized liposomal delivery system reduces cardiotoxicity. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 763–776. 10.2147/ijn.s149887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stull R. A.; Szoka F. C. Jr. Antigene, Ribozyme and Aptamer Nucleic Acid Drugs: Progress and Prospects. Pharm. Res. 1995, 12, 465–483. 10.1023/a:1016281324761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimmele M. Nucleic Acid Aptamers as Tools and Drugs: Recent Developments. Chembiochem 2003, 4, 963–971. 10.1002/cbic.200300648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo J. H.; Ban C. I.; Jo H. H.; Kim J. Y.; Cho Y. K.. HER2 aptamer-anticancer drug complex for cancer cell chemotherapy. U.S. Patent 20,180,050,114 A1, 2018.

- Yan W.; Gu L.; Liu S.; Ren W.; Lyu M.; Wang S. Identification of a highly specific DNA aptamer for Vibrio vulnificus using systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment coupled with asymmetric PCR. J. Fish Dis. 2018, 41, 1821–1829. 10.1111/jfd.12891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katilius E.; Flores C.; Woodbury N. W. Exploring the sequence space of a DNA aptamer using microarrays. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 7626–7635. 10.1093/nar/gkm922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer N. O.; Tok B.-H.; Tarasow T. M. Massively Parallel Interrogation of Aptamer Sequence, Structure and Function. PLoS One 2008, 3, e2720 10.1371/journal.pone.0002720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biroccio A.; Hamm J.; Incitti I.; De Francesco R.; Tomei L. Selection of RNA Aptamers That Are Specific and High-Affinity Ligands of the Hepatitis C Virus RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 3688–3696. 10.1128/jvi.76.8.3688-3696.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Sun L.; Zhao Q. A simple aptamer molecular beacon assay for rapid detection of aflatoxin B1. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2019, 30, 1017–1020. 10.1016/j.cclet.2019.01.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Jiang W.; Yang S.; Hu J.; Lu H.; Han W.; Wen J.; Zeng Z.; Qi J.; Xu L.; Zhou H.; Sun H.; Zu Y. Rapid Detection of Mycoplasma-Infected Cells by an ssDNA Aptamer Probe. ACS Sens. 2019, 4, 2028–2038. 10.1021/acssensors.9b00582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokhtarzadeh A.; Tabarzad M.; Ranjbari J.; Guardia D. L.; Hejazi M.; Ramezani M. Aptamers as smart ligands for nano-carriers targeting. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2016, 82, 316–327. 10.1016/j.trac.2016.06.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alshaer W.; Hillaireau H.; Fattal E. Aptamer-guided nanomedicines for anticancer drug delivery. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2018, 134, 122. 10.1016/j.addr.2018.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan W.; Gu L.; Ren W.; Ma X.; Qin M.; Lyu M.; Wang S. Recognition of Helicobacter pylori by protein-targeting aptamers. Helicobacter 2019, 24, e12577 10.1111/hel.12577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.