Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to compare the clinical and radiological outcomes of the 3D-printed artificial vertebral body vs the titanium mesh cage in repairing bone defects for single-level anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion (ACCF).

Material/Methods

A total of 51 consecutive patients who underwent single-level ACCF in Huai’an Second People’s Hospital from July 2017 to August 2020 were retrospectively reviewed. According to the implant materials used, patients were divided into a 3D-printed artificial vertebral body group (3D-printed group) (n=20; 12 males, 8 females) and a titanium mesh cage group (TMC group) (n=31; 15 males, 16 females). General data, radiological parameters, and clinical outcomes were recorded.

Results

The rate of subsidence in the 3D-printed group (0.01, 2/20) was lower than in the TMC group (0.29, 9/31) (P<0.05). HAE and HPE of the patients in the 3D-printed group were significantly higher than those in the TMC group (P<0.05). C2–C7 Cobb angle and SA of the patients in the 3D-printed group were significantly larger than those in the TMC group (P<0.05). All patients in the 2 groups showed significant improvement in VAS, JOA, and NDI scores at 3 months and 1 year after surgery.

Conclusions

3D-printed artificial vertebral body helps maintain intervertebral height and cervical physiological curvature and is a good candidate for ACCF.

Keywords: Imaging, Three-Dimensional; Neck Pain; Titanium; Uterine Cervical Diseases

Background

With the development of modern life, the prevalence of cervical spine diseases is on the rise. Anterior cervical compression and fusion (ACCF) has the advantages of complete decompression and ample exposure, so it is extensively used in the treatment of a variety of cervical-related diseases [1,2], such as cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM), cervical fracture, tumor, and tuberculosis. ACCF has become one of the main surgical methods for treating CSM [3,4]. Titanium mesh cage (TMC) is currently the most common implant for repairing bone defects during ACCF, but TMC subsidence may occur after surgery and cause a series of changes and clinical symptoms [4–6]. The excessive subsidence of TMC causes changes in intervertebral height and cervical curvature, resulting in compression of nerve roots, ligamenta flava fold, and cervical kyphosis. Extensive research has resulted in great improvements [7–9]. The 3D-printed artificial vertebral body that was recently introduced has the characteristics of larger contact area, favorable mechanical properties, and biocompatibility, becoming an acceptable substitute for repairing bone defects during ACCF [10]. Yang et al [11] used an individualized 3D-printed artificial vertebral body for cervicothoracic reconstruction in a 6-level recurrent chordoma. Xu et al [12] used a personalized 3D-printed vertebral body to reconstruct the upper cervical spine in an adolescent with Ewing sarcoma.

Material and Methods

Patients

Fifty-one consecutive patients who received single-level ACCF between July 2017 and August 2020 were enrolled and their data were retrospectively analyzed. We excluded patients who received more than 1-level ACCF, those with incomplete perioperative radiographic data, and those with primary or metastatic cervical tumors and severe osteoporosis. In this study, 20 patients (12 males, 8 females) with an average age of 58.83±11.13 years (range, 47–79 years) underwent single-level ACCF using a 3D-printed artificial vertebral body. Thirty-one patients (15 males, 16 females) with an average age of 59.17±9.24 years (range, 35–74 years) underwent single-level ACCF using TMC. The level of corpectomy was as follows: C3 (2), C4 (3), C5 (8), and C6 (7) in the 3D-printed group, and C3 (3), C4 (5), C5 (12), and C6 (11) in the TMC group.

Surgical Procedure

Briefly, all patients received general anesthesia and were placed in supine position. A standard anterior cervical surgical approach was used. A transverse incision was made on the right side of the lower edge of the circular cartilage, and muscles and subcutaneous tissue were separated to expose the anterior vertebral body. Then, the positioning needles were insert into the intervertebral space and C-arm fluoroscopy was used to determine the intervertebral space. The longus colli muscle was cut and the anterior longitudinal ligament was stripped. We scraped the cervical disc tissue and performed corpectomy, then explored and relieved the cervical spinal cord compression. The prosthesis was placed in the bone defect and the titanium plate was placed in front of it. The titanium plate was fixed above and below the vertebral body.

General Information

Data on age, sex, and operation segment are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

General patient data (mean±SD).

| Group | 3D-printed group | TMC group | Statistical analysis | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 12 | 15 | ||

| Female | 8 | 16 | ||

| Age (years) | 58.83±11.13 | 59.17±9.24 | −0.56 | 0.956 |

| Surgical segment | ||||

| C3 | 2 | 3 | ||

| C4 | 3 | 5 | ||

| C5 | 8 | 12 | ||

| C6 | 7 | 11 | ||

| Hospital day (days) | 13.50±3.51 | 13.17±3.66 | 0.161 | 0.875 |

| Operation time (mins) | 106.50±7.20 | 127.50±14.40 | −3.194 | 0.010 |

Radiological Assessment

Radiological assessment was performed 1 day before surgery and 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, and 1 year after surgery. We performed anterior-posterior and lateral cervical spine X-ray examination at each follow-up. Radiological assessment included the segmental angle (SA) between the borders of endplates above and below the affected segment, and the heights of the anterior (HAE) and posterior endplates (HPE) were measured as the distance between the anterior and posterior points of the lower endplate of the superior vertebra and the upper endplate of the inferior vertebra and the C2–C7 Cobb angles.

Assessment of Clinical Effectiveness

At each radiological assessment, we performed surgery-related evaluations. Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA) scores were used to evaluate neural functions, Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scores were used to evaluate perioperative pain, and Neck Disability Index (NDI) scores were used to evaluate the degree of cervical function damage.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical evaluation was performed using SPSS 22.0 software. Results are presented as the mean±standard deviation (SD). A paired t test was used to compare the results between the 2 groups. The chi-squared (χ2) test was used to compare quantitative data. The rank-sum test was used to compare qualitative data. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient general data

A total of 51 patients received ACCF using a 3D-printed artificial vertebral body or TMC. The 3D-printed artificial vertebral body was used in 20 patients and TMC was used in 31 patients. All patients were followed up for more than 1 year. The general data of patients are listed in Table 1. There were no deaths during the study period. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in sex, age, or length of hospital stay (P>0.05). The duration of surgery in the 3D-printed group was shorter than that in the TMC group (P<0.05).

Preoperative and Postoperative Parameters

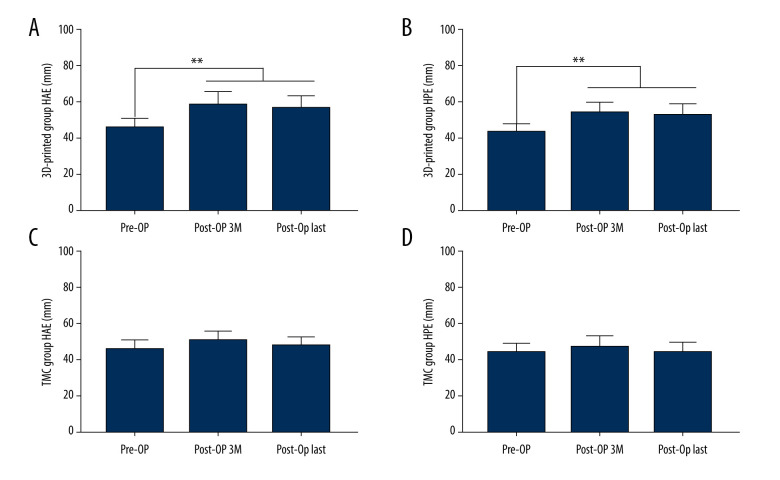

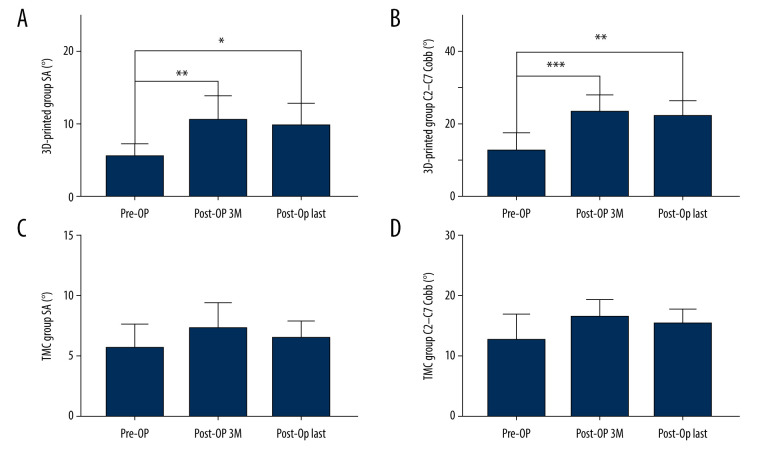

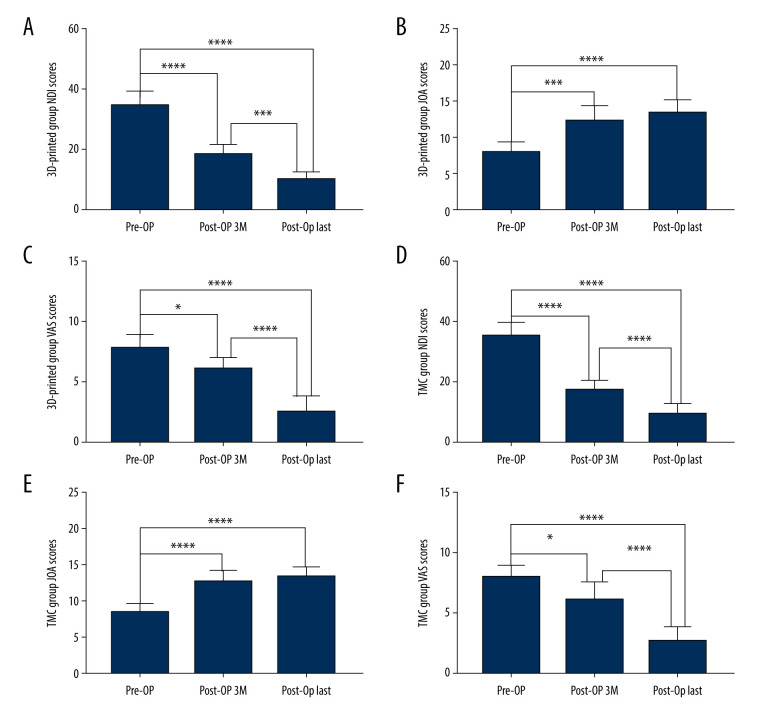

All patients had significantly improved neurological function at the last follow-up compared with before surgery, and all had achieved bone healing by the last follow-up. In this study, we defined subsidence as more than 3 mm. There were 2 cases of subsidence in the 3D-printed group and 9 cases of subsidence in the TMC group (Table 2). The postoperative rate of change in HAE and HPE of the 3D-printed group was significantly higher than that of the TMC group at 3 months and 1 year after surgery (P<0.05) (Table 2). The postoperative rate of change in C2–C7 Cobb angle and SA of the 3D-printed group was significantly larger than that of the TMC group at 3 months and 1 year after surgery (P<0.05) (Table 3). All patients in both groups showed significant improvement in VAS, JOA, and NDI scores at 3 months and 1 year after surgery (Table 4).

Table 2.

Preoperative and postoperative HAE, HPE, and subsidence rate.

| Group | 3D-printed group | TMC group | Statistical analysis | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAE (mm) | ||||

| Pre-OP | 46.14±4.16 | 47.60±3.09 | −0.694 | 0.503 |

| Post-OP 3M | 58.60±5.97 | 52.06±3.62 | 2.295 | 0.045 |

| Post-OP Last | 56.93±5.71 | 49.08±3.91 | 2.778 | 0.020 |

| HPE (mm) | ||||

| Pre-OP | 44.49±3.12 | 45.5±3.38 | −0.571 | 0.581 |

| Post-OP 3M | 55.37±4.70 | 48.80±4.07 | 2.588 | 0.027 |

| Post-OP last | 54.12±4.64 | 45.72±3.91 | 3.388 | 0.007 |

| Rate of subsidence (>3 mm) (%) | 0.01 (2/20) | 0.24 (9/31) | 19.039 | 0.000 |

Table 3.

Preoperative and postoperative C2–C7 Cobb angles and SA.

| Group | 3D-printed group | TMC group | Statistical analysis | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C2–C7 Cobb (°) | ||||

| Pre-OP | 12.89±4.25 | 12.68±4.06 | 0.087 | 0.933 |

| Post-OP 3M | 23.72±3.83 | 16.76±2.43 | 3.758 | 0.004 |

| Post-OP last | 22.64±3.35 | 15.53±1.86 | 4.546 | 0.001 |

| SA (°) | ||||

| Pre-OP | 5.71±1.51 | 5.84±1.70 | −0.133 | 0.897 |

| Post-OP 3M | 10.73±2.96 | 7.47±1.92 | 2.267 | 0.047 |

| Post-OP last | 9.93±2.83 | 6.60±1.30 | 2.614 | 0.026 |

Table 4.

Preoperative and postoperative NDI, JOA, and VAS scores.

| Group | 3D-printed group | TMC group | Statistical analysis | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDI (scores) | ||||

| Pre-OP | 34.83±3.97 | 35.50±3.72 | −0.300 | 0.770 |

| Post-OP 3M | 17.33±2.16 | 20.83±4.02 | −1.878 | 0.090 |

| Post-OP Last | 7.50±1.52 | 10.17±2.32 | −2.359 | 0.040 |

| JOA (scores) | ||||

| Pre-OP | 8.17±1.17 | 8.67±1.03 | −0.785 | 0.451 |

| Post-OP 3M | 12.50±1.64 | 12.83±1.17 | −0.405 | 0.694 |

| Post-OP Last | 13.67±1.37 | 13.50±1.05 | 0.237 | 0.817 |

| VAS (scores) | ||||

| Pre-OP | 7.83±0.98 | 8.17±0.75 | −0.659 | 0.525 |

| Post-OP 3M | 6.17±0.75 | 6.33±1.21 | −0.286 | 0.780 |

| Post-OP Last | 2.67±1.03 | 2.83±0.98 | −0.286 | 0.780 |

Discussion

ACCF has the advantages of complete decompression and ample exposure [1,2]. Since first reported in the 1950s, it has been widely used in the treatment of various cervical spine diseases and has become one of the main surgical procedures used for the treatment of CSM [3,4]. There are many methods for the reconstruction of local cervical spine stability after decompression. Autogenous bone transplantation is considered to be the criterion standard for bone fusion [13,14], and autogenous iliac bone transplantation is widely used. However, complications related to autologous iliac bone transplantation are still a disturbing problem, which may lead to related complications such as bone resorption, vertebral body subsidence, and pseudo-articular formation [15,16]. In addition, the material is limited, and additional surgery is required to remove the bone, causing bleeding and pain in the iliac fossa [17]. Allogeneic bone transplantation has disadvantages such as possible disease transmission, immune response induction, and poor bone healing. TMC has good biocompatibility and can be trimmed freely, and the hollow structure can be filled with a large amount of autogenous bone. TMC with autologous bone graft is generally accepted and widely used.

With the increasing popularity of TMC in ACCF, its shortcomings have become increasingly apparent, especially when the TMC subsides. Loss of intervertebral height, ligamenta flava folds, and volume of the intervertebral foramen frequently occur, and corresponding decreases can result in spinal cord and nerve compression [7,18]. The definition of TMC subsidence is not absolutely clear. Van Jonbergen et al [19] believed that due to errors in measurement, it is recommended to define the postoperative reduction of intervertebral height by more than 3 mm as TMC subsidence, which is generally accepted. In addition, Chen et al [20] divided TMC subsidence into mild (1–3 mm) and severe (>3 mm).

To reduce related complications, Zhang et al [17] used a new type of nano-hydroxyapatite/polyamide 66 (n-HA/PA66) TMC that is conducive to the growth and migration of bone cells. The bending strength, tensile strength, compressive strength, and elastic modulus of the n-HA/PA66 strut are similar to those of human bone, but the osteoconductivity and osseointegration characteristics of the prosthetics are still insufficient for clinical applications. Wang et al [8] conducted in vitro biomechanical studies on a dome-shaped TMC, finding it has stronger resistance to subsidence than normal TMC, but the clinical effect of the dome-shaped TMC needs to be further verified. Lu et al [9] used a new type of 3D-printed anatomy adaptive titanium mesh cage (3D-printed AA-TMC) to treat CSM and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL). It increases the contact area with the vertebral body, and the 3D-printed microporous structure is conducive to the growth and integration of bone cells.

In recent years, 3D-printed technology, materials science, and engineering have been continuously developed. 3D-printed technology has a very high degree of freedom in processing. Engineers can use CT, MRI, and other medical images to reconstruct the patient’s failed bone through the computer modeling to manufacture prosthetics with biological and mechanical properties that better match the bone [21]. Yang et al [11] used individualized a 3D-printed artificial vertebral body for cervicothoracic reconstruction in a 6-level recurrent chordoma. Xu et al [12] used a personalized 3D-printed vertebral body to reconstruction of the upper cervical spine in an adolescent with Ewing sarcoma. Most of the 3D-Printed prosthetics are titanium alloys. 3D-printed titanium alloy prosthetics have the advantages of excellent biocompatibility and corrosion resistance and thus are now used widely in orthopedics [22]. One of the causes of TMC subsidence is that TMC has a greater elastic modulus than human bone, causing stress shielding [23]. 3D-printed technology can make titanium alloy into a porous structure that is conducive to the migration and proliferation of bone cells. 3D-printed porous titanium alloy prosthetics can not only construct shapes that match bone defects, but also combine growth factors and osteoblasts. 3D-printed porous prosthetics can simulate the human cell microenvironment and accelerate bone tissue healing [24]. Also, due to the special process of 3D-printed technology, the surface of the 3D-printed prosthetics is relatively rough, which creates ideal conditions for early cell attachment. Olivares-Navarrete et al [25] found that porous titanium alloy prosthetics increase the maturation of osteoblasts and creates an osteogenic environment that contains BMP2, BMP4, and BMP7, enhancing bone formation and implant stability.

The 3D-printed artificial vertebral body is composed of Ti6Al4V. The porosity of the 3D-printed artificial vertebral body we used is 80% and the compression strength and elastic modulus are similar to those of human bones. For porous prosthetics, some scholars reported that the porosity should be controlled at between 65% and 80% [26]. The price of 3D-printed artificial vertebral body is around 11000 yuan ($1600), while the price of a titanium mesh cage is about 7000 yuan ($1000 USD). The price of the former is higher than that of the latter. The design of porous prosthetics can improve the embedding of bone to the surface, reduce the difference in elastic modulus between bone and metal surface, prevent the aseptic loosening of implants, and improve their long-term stability. Although the design of a porous structure can effectively reduce the elastic modulus of the prosthetic, its compressive strength is greatly reduced with increasing porosity. Low-porosity prosthetics have high mechanical tension, but tend to generate stress shielding due to their high elastic modulus, which can cause the prosthetic to fall off, and also prevents cells from growing into spaces sufficiently.

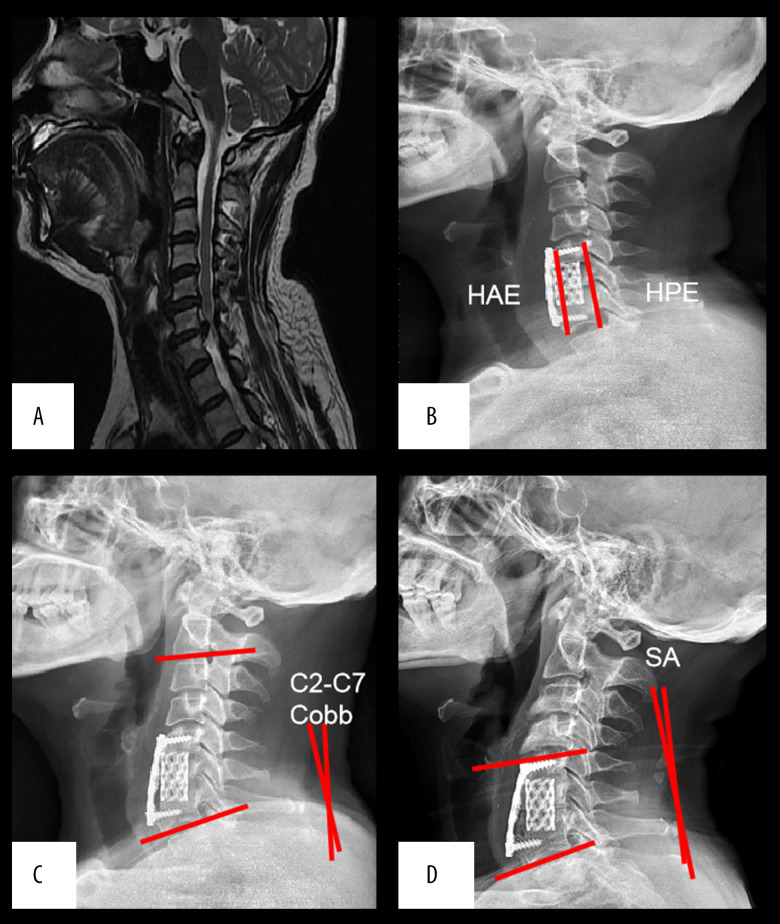

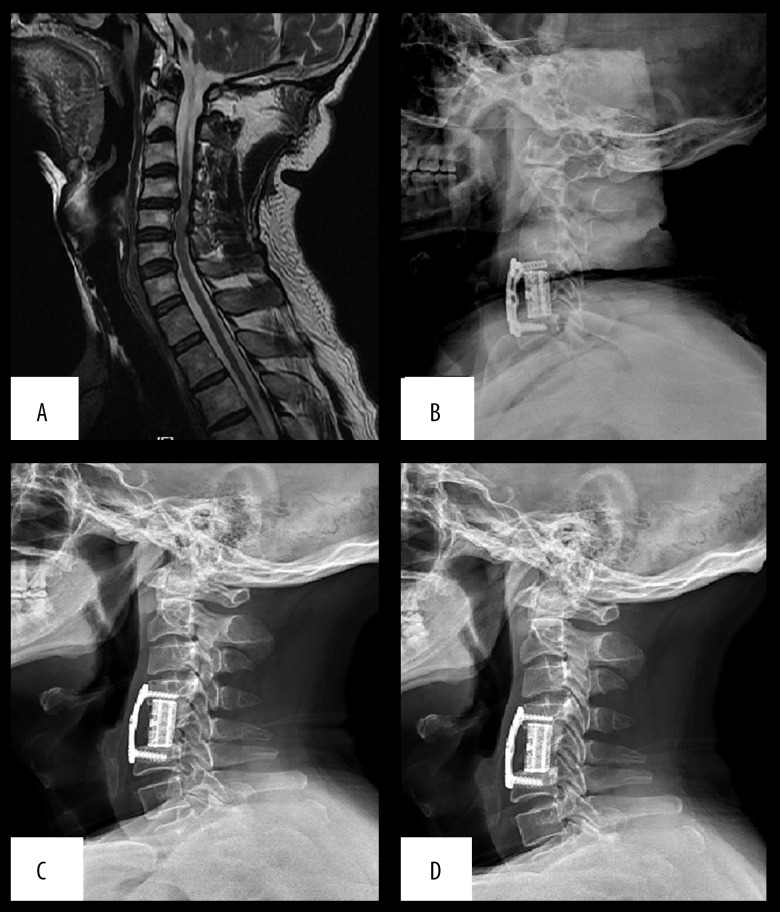

Some examples of 3D-printed artificial vertebral bodies and titanium mesh cages are listed in Figure 1. Figures 2 and 3 show the preoperative and postoperative radiological results respectively. In this study, postoperative indexes improved compared with preoperative indexes in all patients (Figures 4–6). Patients in the 3D-printed group had a lower probability of subsidence than that in the TMC group. Also, HAE and HPE of patients in the 3D-printed group were significantly higher than that in the TMC group at 3 months and 1 year after surgery. We used the 3D-printed artificial vertebral body to reduce subsidence based on its characteristics of excellent biocompatibility and corrosion resistance. The 3D-printed artificial vertebral body increases the maturation of osteoblasts and creates an osteogenic environment, which reduces subsidence. It also has a larger contact area than the TMC (Figure 1). SA and C2–C7 Cobb angles of patients in the 3D-printed group were closer to normal values than that in the TMC group. The results from the present study show that intervertebral height stabilization helps maintain cervical stability and physiological curvature, as reported in previous studies [7,18]. Patients in the 3D-printed group had lower VAS and NDI scores than in the TMC group. The duration of surgery in the 3D-printed group was shorter than that in TMC group because TMC requires more time for trimming.

Figure 1.

(A, C) Show examples of 3D-printed artificial vertebral bodies. (B, D) Show the examples of TMCs.

Figure 2.

(A) Preoperative MRI showed obvious C6/7 intervertebral disc herniation, spinal stenosis, and nerve compression (B) 1 week after surgery, (C) 3 months after surgery, and (D) 1 year after surgery.

Figure 3.

(A) Preoperative MRI showed compression and deformation of cervical spinal cord behind C4/C5 vertebral body (B) 1 week after surgery, (C) 3 months after surgery, and (D) 1 year after surgery.

Figure 4.

Related evaluation indexes of patients in the 3D-printed group and TMC group at different time points. (A–D) 3D-printed group and TMC group preoperative and postoperative HAE and HPE. All data are expressed as mean±standard deviation. (0.01< * P<0.05, 0.001< ** P<0.01, and *** P<0.001).

Figure 5.

Related evaluation indexes of patients in the 3D-printed group and TMC group at different time points. (A–D) 3D-printed group and TMC group preoperative and postoperative C2–C7 Cobb angles and SA. All data are expressed as mean±standard deviation. (0.01< * P<0.05, 0.001< ** P<0.01, and *** P<0.001).

Figure 6.

Related evaluation indexes of patients in 3D-printed group and TMC group at different time points. (A–F) 3D-printed group and TMC group preoperative and postoperative NDI, JOA, and VAS scores. All data are expressed as mean±standard deviation. (0.01< * P<0.05, 0.001< ** P<0.01, and *** P<0.001).

Conclusions

Compared with the titanium mesh cage, the 3D-printed artificial vertebral body performs better in maintaining intervertebral height and cervical physiological curvature, and thus is a good candidate for use in ACCF.

Footnotes

Source of support: This study was supported by the Key Research Program of Science and Technology Support Program of Jiangsu Province (BK20171265), and the Research Program of Science and Technology Support Program of Huai’an (HAP201608)

References

- 1.Qiu X, Zhao B, He X, et al. Interface fixation using absorbable screws versus plate fixation in anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion for two-level cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e921507. doi: 10.12659/MSM.921507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, Liu H, Yang H, Pi B. Anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion versus discectomy and fusion for the treatment of two-level cervical spondylotic myelopathy: Aanalysis of sagittal balance and axial symptoms. Int Orthop. 2018;42(8):1877–82. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-3804-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang L, Wang X, Wang W, et al. Design, biomechanical study, and clinical application of a new pterygo-shaped titanium mesh cage. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2012;22(2):111–17. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhong W, Liang X, Tang K, et al. Nanohydroxyapatite/polyamide 66 strut subsidence after one-level corpectomy: Underlying mechanism and effect on cervical neurological function. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):12098. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30678-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ji C, Yu S, Yan N, et al. Risk factors for subsidence of titanium mesh cage following single-level anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-3036-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burkett CJ, Baaj AA, Dakwar E, Uribe JS. Use of titanium expandable vertebral cages in cervical corpectomy. J Clin Neurosci. 2012;19(3):402–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2011.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kabir SMR, Alabi Rezapoor K, Casey ATH. Anterior cervical corpectomy: Review and comparison of results using Titanium mesh cages and Carbon fibre reinforced polymer cages. Br J Neurosurg. 2010;245:542–46. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2010.503819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Lu T, He X, et al. An in vitro biomechanics study. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:142–49. doi: 10.12659/MSM.911888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu T, Liu C, Yang B, et al. Single-level anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion using a new 3D-printed anatomy-adaptive titanium mesh cage for treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: A retrospective case series study. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:3105–14. doi: 10.12659/MSM.901993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xue W, Krishna BV, Bandyopadhyay A, et al. Processing and bio- compatibility evaluation of laser processed porous titanium. Acta Biomater. 2007;3(6):1007–18. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang X, Wan W, Gong H, Xiao J. Application of Individualized 3D-printed artificial vertebral body for cervicothoracic reconstruction in a six-level recurrent chordoma. Turk Neurosurg. 2020;30(1):149–55. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.25296-18.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu N, Wei F, Liu X, et al. Reconstruction of the upper cervical spine using a personalized 3D-printed vertebral body in an adolescent with Ewing sarcoma. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41(1):E50–54. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanayama M, Hashimoto T, Shigenobu K, et al. Pitfalls of anterior cervical fusion using titanium mesh and local autograft. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16(6):513–18. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200312000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malloy KM, Hilibrand AS. Autograft versus allograft in degenerative cervical disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;394:27–38. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200201000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weber MH, Fortin M, Shen J, et al. Graft subsidence and revision rates following anterior cervical corpectomy: A clinical study comparing different interbody cages. Clin Spine Surg. 2017;30(9):E1239–45. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Narotam PK, Pauley SM, McGinn GJ. Titanium mesh cages for cervical spine stabilization after corpectomy: A clinical and radiological study. J Neurosurg. 2003;99(2 Suppl):172–80. doi: 10.3171/spi.2003.99.2.0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Deng X, Jiang D, et al. Long-term results of anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion with nano-hydroxyapatite/polyamide 66 strut for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26751. doi: 10.1038/srep26751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fengbin Y, Jinhao M, Xinyuan L, et al. Evaluation of a new type of titanium mesh cage versus the traditional titanium mesh cage for single-level, anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(12):2891–96. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-2976-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Jonbergen HP, Spruit M, Anderson PG, et al. Early radiological assessment of fusion and subsidence. Spine J. 2005;5(6):645–49. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y, Chen D, Guo Y, et al. A study based on 300 case. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21(7):489–92. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e318158de22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warnke PH, Douglas T, Wollny P, et al. Porous titanium alloy scaffolds produced by selective laser melting for bone tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2009;15(2):115–24. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2008.0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu H, Li W, Liu C, et al. Incorporating simvastatin/poloxamer 407 hydrogel into 3D-printed porous Ti6Al4V scaffolds for the promotion of angiogenesis, osseointegration and bone ingrowth. Biofabrication. 2016;8(4):045012. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/8/4/045012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagels J, Stokdijk M, Rozing PM. Stress shielding and bone resorption in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(1):35–39. doi: 10.1067/mse.2003.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim K, Yeatts A, Dean D, Fisher JP. Stereolithographic bone scaffold design parameters: Osteogenic differentiation and signal expression. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2010;16(5):523–39. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2010.0171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olivares-Navarrete R, Gittens RA, Schneider JM, et al. Osteoblasts exhibit a more differentiated phenotype and increased bone morphogenetic protein production on titanium alloy substrates than on poly-ether-ether-ketone. Spine J. 2012;12(3):265–72. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mullen L, Stamp RC, Fox P, et al. A unit cell approach for the manufacture of porous, titanium, bone in-growth constructs, suitable for orthopedic applications. II. Randomized structures. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2010;92(1):178–88. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]