Abstract

Aim

The attitudes and behaviours of nursing staff are critical to determine patients’ satisfaction and to have a competitive advantage for any healthcare organization. This study is set to investigate the effects of internal service quality (ISQ) on nurses’ job satisfaction, employee commitment, well‐being and job performance in the healthcare sector of Pakistan. Further, this study also examines the mediating role of nurses’ well‐being for the relationship of job satisfaction and commitment with their job performance.

Methods

This was a cross‐sectional quantitative research. A self‐administered survey was used to collect data from 412 nursing employees of 20 private sector healthcare centres operating in Pakistan. Partial least square of structural equation model (PLS‐SEM) and structural equation modelling (SEM) were employed through Smart PLS 3.2.8 for data analysis.

Results

Study results revealed that ISQ directly effects employees’ satisfaction, commitment, well‐being of the nursing employees. Moreover, employees’ well‐being has mediated job satisfaction and job performance relationship; however, well‐being did not mediate the relationship between commitment and job performance.

Keywords: employee commitment, employee–nurse satisfaction, health care, internal service quality, well‐being

1. INTRODUCTION

In this modern era, organizations are competing in a global market. Healthcare sector of a country has a significant influence on its economy and overall health of the nation. There is a growing recognition of nurses’ wellness in the workplace and its impact on nurses’ productivity and effectiveness (Berry et al., 2010; Mirabito & Berry, 2015) which ultimately leads to the performance of healthcare organizations. The concept of internal service has emerged as one of the most vital principles of the service management approach (Farner et al., 2001). According to customer service literature, service quality (SERVQUAL) is the primary debate for modelling and operationalization of service quality in the measurement of an effective organizational system (Brandon‐Jones & Silvestro, 2010; Wang & Li, 2018). Previous studies consider internal service quality (ISQ) operationalization (Brandon‐Jones & Silvestro, 2010), explores its antecedents and consequences (Nazeer et al., 2014) and study its role as a mediator variable (Ehrhart et al., 2011).

A lot of literature is available relating to the SERVQUAL with reference to the healthcare sector (e.g. Akdere et al., 2020; Fatima et al., 2018; Mosadeghrad, 2014); however, relatively less studies have examined the effects of ISQ on nursing staff attitudes and behaviours (Prakash & Srivastava, 2019), especially in the developing countries like Pakistan. The existing literature positively associates human resources performance with organizational performance (Hitt et al., 2001; Moynihan & Pandey, 2007). Moreover, job motivation and satisfaction are positively correlated to employee retention and intent to stay with the current employer (Rahman et al., 2008; Rust et al., 1996).

Furthermore, reduced job satisfaction has been firmly established as a prime predictor of voluntary turnover (Griffeth et al., 2000). Job Satisfaction has a positive association with job performance (Miller et al., 2001; Moynihan & Pandey, 2007). Over the past few decades, the global shortage of employees has been steadily growing (Kingma, 2001). Studies have shown that job dissatisfaction is positively linked with employees’ intention to quit (Applebaum et al., 2010; Heinen et al., 2013) and worsening the overall nursing staff supply for the healthcare organizations. Some sources of job satisfaction include cohesion among the nursing staff (Adams & Bond, 2000), management's engagement and support (Masum et al., 2016; Tovey & Adams, 1990; Uğur GöK & Kocaman, 2011), autonomy and ability to make a decision (Nolan et al., 1995) and interactions with the patients (Tzeng, 2002a, 2002b).

Health care is one of the fastest‐growing industries worldwide, and healthcare professions are in high demand now a day. Pakistan is a developing country with a low‐income level. Like most of the developing countries, private healthcare sector is providing better services as compared with the public sector in Pakistan (Javed et al., 2019). However, there are still deficiencies which need to be covered. Healthcare centres must improve internal services to enhance their service quality and thus increase profits. However, previous research determined that the nursing employees’ wellness depends on the internal services provided to its employees. Additionally, employees’ effectiveness and efficiency increase as they feel more motivated towards their job (Eskildsen & Dahlgaard, 2000). Ultimately, this leads to organizations' sustainability in the market (Berry et al., 2010; Mirabito & Berry, 2015).

Healthcare occupations are of high pressure and have long working hours. Also, being a critical industry, healthcare centres must provide more timely facilities and services as compared with other service sectors. They are expected to respond to the consumers/ patients in no time. The nurses are required to serve patients in the standard approach (Gupta & Sharma, 2009). Nurses’ commitment level, performance effectiveness and efficiency are affected due to work‐related pressure. Internal service is adopted and implemented in various healthcare centres, leading to nurses’ satisfaction (Prakash & Srivastava, 2019). Further, Berry et al. (2010) and Mirabito and Berry (2015) have highlighted the importance of employee wellness at the workplace and its impact on employee's productivity and effectiveness. Based on the effective event theory, it is necessary to investigate the role of internal services quality to improve the performance of an employee at the workplace, which will ultimately result in organizational wellness. Moreover, previously there is no study which has investigated the role of internal service quality in the health sector of Pakistan.

Therefore, this study is set to investigate the influence of ISQ on nurses’ job satisfaction, employee commitment, well‐being and job performance in the healthcare settings. Further, this study also examines the mediating role of nurses’ well‐being for the relationship of job satisfaction and commitment with their job performance.

1.1. Conceptual framework

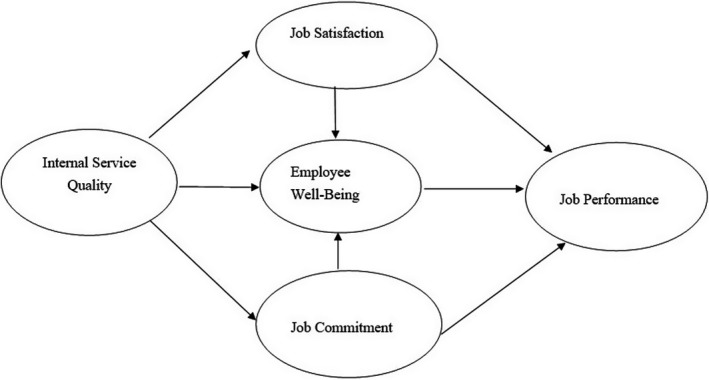

This study is vital to investigate and analyse the role of ISQ and how it effects on nurses’ performance in the Pakistani private healthcare sector (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual Framework

2. BACKGROUND

The internal service quality (ISQ) is considered as one of the primary driver for employee loyalty, job satisfaction and organizational productivity (Hallowell et al., 1996; Sharma et al., 2016). Therefore, the ISQ management system is considered integral for consumer‐oriented organizations. It is focused on higher internal services through the satisfaction of internal consumers’ needs. The poor level of ISQ can severely damage the employees’ organizational commitment (Sharma et al., 2016). Organizations providing high‐quality internal services can achieve their goals more efficiently and effectively (Berry, 1981; Grönroos, 1981). In this way, a higher level of ISQ leads to a higher level of employees’ commitment and satisfaction—both of which help to enhance employee performance. Employee satisfaction level explains the perception of an employee about his or her job, whether he or she is willing to work in that particular organization and to what extent the job has associated with positive and negative aspects (Moorhead & Griffin, 2008). Employee commitment means bonding with an organization that creates an employment relationship with his or her employer organization. This bonding has a significant impact on employee performance, which can be positive, as well as negative (Becker et al., 1996; Meyer et al., 2004; Rubin & Brody, 2011).

One of the earliest definitions of job satisfaction is “a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one's job or job experience” (Locke, 1976, p. 1304). Job satisfaction is explained in terms of a job's agreeability (Ellickson & Logsdon, 2002), as well as in terms of employees’ positive sensations and preference for the work itself (Shields & Price, 2002). An employee satisfaction is recognized as one of the most vital drivers of employee’ service quality, productivity and loyalty (Matzler & Renzl, 2006). Previous studies have revealed that ISQ helps employees do their jobs better, which makes them feel more satisfied (Chiang & Wu, 2014; Hallowell et al., 1996; Loveman, 1998; Nazeer et al., 2014; Pantouvakis, 2011). ISQ has a significant influence on employees’ satisfaction or job satisfaction and improved ISQ facilitates employees to improve their job performance. Organizations having high quality of internal services to their employees are more developed and successful (Khan et al., 2011). Satisfied employees used to be hard worker, and they are highly motivated (Eskildsen & Dahlgaard, 2000).

Hypothesis H1

Internal service quality has a positive effect on employee satisfaction.

In management research, employee commitment is considered an essential aspect as it has a direct nexus with employee as well as with organizational performance. Several factors are associated with human resources and these factors play a pivotal role in the development of organizations through the factors like employees’ satisfaction, employee commitment, loyalty and communication. A higher commitment level of the employees with their employer leads to higher level of productivity. Employees’ performance and commitment have a direct relation and high commitment of employees has a positive impact on their work performance.

Over the past few years, the concept of employee commitment has emerged in a significant way and a strong relationship has been found between employee commitment and ISQ (Bai et al., 2006; Boshoff & Mels, 1995; Ching et al., 2019; Odeh & Alghadeer, 2014). ISQ has a positive influence on employees’ commitment as it can enhance employees’ commitment at a high level and encourage them to work hard for the advancement and success of the organization. Some researchers considered employees’ commitment as a psychological state of employees that indicates a firm relation of employees with the organization and motivates them to work harder for their employer organization (Richardsen et al., 2006). A higher level of employees’ commitment is beneficial for the organization as it leads to high level of behavioural outcomes and helps the organization to achieve its overall goals (Khan et al., 2011).

Researchers argued that ISQ has an impact on employee commitment and employee satisfaction level (Maharani et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2016). In the same way, many researchers used variables other than ISQ and do not consider it when studying about employee commitment (Vanniarajan & Subbash Babu, 2011). Studies conducted on employee commitment and ISQ have revealed that ISQ would make the employees’ work easier and would have a positive impact on it. This is why organizations need to improve ISQ to make employees’ jobs more meaningful and productive (Masemola, 2011).

Hypothesis H2

Internal service quality has a positive effect on employee commitment.

The concept of employee well‐being has emerged over the past few years. Well‐being includes different aspects an organization covers such as health and safety. Organizations are initiating productivity programmes for the employees’ betterment. Workplace health and well‐being programmes have become essential not only for the employees but also for the organization because they have a positive impact on employees’ performance (Guest & Conway, 2002).

There are several possible ways through which employees’ well‐being can be maintained in the organization such as on‐site fitness programmes, a flexible working arrangement to avoid frustration, financial education, career coaching, emotional intelligence development training, providing healthy food to employees, establishing a friendly environment work in the organization and so on (Renee Baptiste, 2008). Employees’ well‐being also enables them to have a good relationship with other employees, so they can work in a team and produce better outcomes (Lawson et al., 2009). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an individual's health is the mix of mental, physical and social well‐being. In the case of employees, well‐being is the combination of mental, physical, emotional and spiritual well‐being. Mental health is the designation of less depression, anxiety and stress. Physical health issues include digestive issues, headache, muscle pains and dizziness. Several researchers argued that employees who have to work under pressure and in stressful condition would have a low‐performance level that would have an impact on the organizational outcomes (e.g. Babic et al., 2020; Kinman & Johnson, 2019). According to these authors, employees have to work under stress, fear, pressure, anxiety and tension in an unhealthy work environment. Consequently, such organization would face increased employee absenteeism and employee turnover.

Hypothesis H3

Internal service quality has a positive effect on employee well‐being.

Extant literature on employee satisfaction has shown that while its determinants may vary among different jobs, it has a crucial influence on worker's performance (Jalagat, 2016; Torlak & Kuzey, 2019). In the case of healthcare, nurse satisfaction is a consistent predictor of nursing performance and patient satisfaction (Ahmad et al., 2017; Perry et al., 2018; Putra et al., 2017). This link is also observed when using longitudinal data (Shazadi et al., 2017). That is, the positive effects of nurses’ satisfaction on job performance hold over time. Moreover, nurses’ job satisfaction has a positive relationship with staff productivity and organizational growth, mainly when employed by a non‐governmental institution (Mirzabeigi et al., 2018).

Hypothesis H4

Employee satisfaction has a positive effect on job performance.

Employee commitment has a positive impact on job performance (Ahmad et al., 2014; Shazadi et al., 2017). This overall effect can be disaggregated and observed in the several facets of employee commitment, including meaningful work, value congruence, safe working environment, proper training and coaching and teamwork. When nurses perceive their work as significant, it has a positive effect on task performance and quality of nursing care (Tong, 2018). Some factors have specific importance in influencing nurses’ and healthcare professionals’ level of organizational commitment. Workplace violence is a prevalent phenomenon in healthcare and a global public health concern which has been shown to severely damage nurses’ commitment to their jobs and employer organization and, thus negatively influence their performance (Arnetz et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2018). Another concern for work environment safety is injury rates, which are higher in healthcare than any other industries (Dressner, 2017). Safe patient handling programmes can lead to decrements in injury rates (Tompa et al., 2016). Peer coaching increases the success of such programmes (Allen et al., 2015; Hurtado et al., 2018) by proving co‐worker support (Spruce, 2015), which increases nurses’ commitment and job performance.

Hypothesis H5

Employee commitment has a positive effect on job performance.

By definition, employee well‐being is a broad concept. A multitude of factors can be a source of well‐being, including leadership, empowerment, autonomy, resilience, stress and burnout (Baek & Yang, 2017; Li & Hasson, 2020; Rantika, 2017). Nurses with higher levels of independence tend to be high performing, satisfied and committed in their jobs (Labrague et al., 2019). Nurses who identify themselves as responsible for the welfare of their patients and build their resilience continue to perform despite the job stressors (Ang et al., 2019). Stress and burnout have adverse effects on nurses’ performance (Chen & Fang, 2016; Gasparito & Guilardello, 2015; Zhang et al., 2014). For instance, haemodialysis nurses experience high levels of burnout even though their work environment is favourable and they have acceptable levels of job satisfaction (Hayes et al., 2015). Burnout occurs less in men, younger people, and married individuals compared to others (Tarcan et al.,2017).

Hypothesis H6

Employee well‐being has a positive effect on job performance.

Hypothesis H7

Employee well‐being positively mediates the impact of nurses’ job satisfaction on employee performance.

Hypothesis H8

Employee well‐being positively mediates the impact of nurses’ job commitment on employee performance.

3. METHODS

This was a relational quantitative study which used self‐administered survey approach for primary data collection.

3.1. Research design, settings and participants

This research was a quantitative relational study which used cross‐sectional survey design approach to test the proposed relationships. The purpose of this approach was to determine the effect of ISQ on nurses’ satisfaction, commitment, well‐being and performance along with the mediating role of well‐being for the relationships of satisfaction and commitment with job performance. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) and Smart PLS 3.2.8 softwares was used for the data analysis as this technique is widely adopted by the scientific community, being more robust compared with the traditional regression analysis (Amram & Dryer, 2008). For the purpose of this study, the frontline nursing employees, directly dealing with the patients, working in the healthcare organizations operating in Pakistan were targeted. For sample selection, 20 healthcare organizations were randomly selected for this study. Finally, 800 frontline nursing employees from these healthcare organizations, with at least one year of service in current organization, were requested to participate in this study. Primary data for hypotheses testing have been collected through a self‐administered survey. The survey acts as an appropriate way for the assessment of information related to the sample. It allows the researchers to draw results from a sample of responses from respondents (Gregar, 1994). A total of 430 survey forms were received back from the participants out of which 18 were not filled properly and thus eliminated. Finally, 412 responses were used for data analysis, which constituted a response rate of 51.5%. Reliability of all the measurement scales was tested to ensure the soundness of measures.

3.2. Measures

Multi‐item measures were used for the measurement of the constructs used in this study to avoid any drawback which could be occurred due to the use of a single‐item scale (Churchill, 1979; Nunnally et al., 1978). The single‐item scale lacks appropriateness of the correlation between the variables (Churchill, 1979). Further, Likert scale approach is commonly used to collect responses for measuring the latent construct (Kent, 2001). In this study, 5‐point Likert scale was used starting from 5 for “strongly agree” ‐ 1 for “strongly disagree” to gauge the responses of the participants for each of the construct of the study.

Internal services quality (ISQ) was measured using a 9‐item scale developed by Ehrhart et al., (2011). Participants’ responses on ISQ covered aspects including response timing, follow‐through, competence of the employees, job knowledge, quality of interaction and level of cooperation. Employee satisfaction is generally described as the feeling of gratification or prosperity that employees procure from their job (Moorhead & Griffin, 2008). In this study, employee satisfaction was measured by adopting a 4‐item scale from the study of Homburg and Stock, (2004). Further, there is a different perspective that can define or explain employee's commitment, such as employee's commitment is the name of the connection to the goal, connection to an organization, connection to the work and someone's attitude towards his or her work (Meyer et al., 2004). In this study, commitment consisted of two dimensions. The first one was a normative commitment and the second one was continuance commitment. Normative commitment has the items related to organization and continuance commitment has items related to personal or emotional attachment with the organization. The overall commitment of the participants was measured using a 13‐item scale developed by Mcdonald and Makin, (2000). Next, employee well‐being is defined by the quality of life, health, sleep, capacity and activities. The well‐being of participating employees was measured using a 9‐item scale from the study of Skevington et al. (2004). Moreover, “positive job attitude creates a tendency to engage or contribute to desirable inputs into one's work role” (Harrison et al., 2006, p. 312). In the present research, employee performance has items like attitude, initiative, dependability, responsibility, team play and overall performance. For this study, employees’ job performance was measured using a 10‐item scale from the study of Werner, (1994). We have used SPSS and Smart PLS for data analysis. These statistical software tools are useful for solving research problems. Complex data sets with advanced statistical procedures can be adopted by statistical tools. Table 1 shows study variables measurements and scale items.

TABLE 1.

Measurements

| Measurement | Scale item |

|---|---|

| Internal Service Quality (Ehrhart et al., 2011; Schneider et al., 1998). How do you rate the service provided by the employees in the other departments in your organization, on the following attributes? | |

| Internal Service Quality | Timeliness of response |

| Follow‐through | |

| Competence of employees | |

| Job knowledge | |

| Quality of interaction | |

| Level of cooperation | |

| Employee satisfaction (Homburg & Stock, 2004) | |

| Employee satisfaction | All in all, I am satisfied with my job. |

| All in all, I am satisfied with my coworkers. | |

| All in all, I am satisfied with my supervisor. | |

| All in all, I am satisfied with my working at this company. | |

| Employee commitment (McDonald & Makin, 2000) | |

| Affective commitment | I have a strong sense of belongings to my organization. |

| I really feel as if this organization's problems are my own. | |

| I feel like 'part of the family' at my organization. | |

| I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization. | |

| Continuance commitment | Right now, staying with my organization is a matter of necessity as much as desire. |

| It would be very hard for me to leave my organization right now, even if I wanted to. | |

| I feel that I have too few options to consider leaving this organization. | |

| Employee well‐being (Skevington et al., 2004) | |

| Employee well‐being | How would you rate your quality of life? |

| How satisfied are you with your health? | |

| How satisfied are you with your sleep? | |

| How satisfied are you with your ability to perform daily activities? | |

| How satisfied are you with your capacity for work? | |

| How satisfied are you with yourself? | |

| To what extent do you feel that physical pain prevents you from doing what you need to do?* | |

| How much do you need any medical treatment to function normally in your daily life?* | |

| How often do you have negative feelings such as blue mood? despair, anxiety, depression? | |

| Employee performance (Werner, 1994). How would you rate this employee on the following attributes? | |

| Employee performance | Attitude |

| Initiative | |

| Dependability | |

| Responsibility | |

| Judgement | |

| Work knowledge | |

| Work quality | |

| Organization capability | |

3.3. Ethics

The research proposal was submitted for ethical clearance to the ethical committee at COMSATS University Islamabad. It was confirmed to have no harm to healthcare providers. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and information collected from healthcare providers was kept confidential.

4. RESULTS

Table 2 represents the demographic attributes of the participants including gender, age, marital status, nature of employment, job experience, education level and monthly salary. The female ratio was higher as compared with males in the targeted healthcare organizations. According to the results, 8.492% (35) respondents were under 25 years old, 28.883% (119) respondents were 26–30 years old, 38.349% (158) respondents were 31–25 years old, 15.048% (62) respondents were 36–40 years old and 9.223% (38) respondents were more than 40 years old. Most of the employees were married and have job experience of 6–10 years.

TABLE 2.

Demographic attributes

| Attributes | Distribution | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 151 | 36.650 |

| Female | 261 | 63.345 | |

| Age | Under 25 years | 35 | 8.495 |

| 26–30 years | 119 | 28.883 | |

| 31–35 years | 158 | 38.349 | |

| 36–40 years | 62 | 15.048 | |

| Above 40 years | 38 | 9.223 | |

| Marital status | Single | 167 | 40.533 |

| Married | 223 | 54.126 | |

| Others | 20 | 4.854 | |

| Nature of employment | Contractual | 198 | 48.058 |

| Permanent | 171 | 41.504 | |

| Others | 43 | 10.436 | |

| Job experience | Under‐5 years | 54 | 13.106 |

| 6–10 years | 143 | 34.708 | |

| 11–15 years | 103 | 25.00 | |

| 16–20 years | 75 | 18.203 | |

| Above 20 years | 37 | 8.90 | |

| Education level | Master degree | 74 | 17.961 |

| Bachelor degree | 248 | 60.194 | |

| Diploma | 69 | 16.747 | |

| Other | 21 | 5.097 | |

| Monthly salary (In PKR) | Less than 20,000 | 72 | 17.475 |

| 21,000–30,000 | 216 | 52.427 | |

| 31,000–40,000 | 79 | 19.174 | |

| More than 40,000 | 45 | 10.922 |

Table 3 presents the values of means, standard deviations and correlations between the variables of the study. All the skewness and kurtosis values lay within the range indicated normality of the data. The mean value of ISQ, employee satisfaction, employee's commitment, employee's well‐being and employee's performance were 3.42, 3.61, 4.38, 3.42 and 3.51, respectively. The standard deviation value of the employee's commitment was 1.64, which was the highest as compared with other variables. The values in diagonal show the square roots of the average variance extracted (AVE). Each latent construct has a higher value of its square roots of average variance (AVEs) as compared with the respective correlation of the latent construct. So, these results from measurement model analysis confirmed the convergent and discriminant validity of all the measures used in this study.

TABLE 3.

Means, standard deviations and discriminant validity (HTMT Ratio)

| Variables | Means | SD | ISQ | ES | EC | EW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISQ | 3.419 | 1.432 | ||||

| ES | 3.604 | 0.849 | 0.621 | |||

| EC | 4.384 | 1.638 | 0.563 | 0.716 | ||

| EW | 3.416 | 1.199 | 0.573 | 0.542 | 0.495 | |

| EP | 3.512 | 1.432 | 0.349 | 0.520 | 0.481 | 0.531 |

Reliability results are reported in parentheses.

Abbreviations: EC, employee commitment; EP, employee performance; ES, employee satisfaction; EW, employee well‐being; ISQ, internal service quality.

Results reported in Table 3 indicate means, standard deviations and discriminant validity. We assessed discriminant validity using the heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) criteria. Henseler et al. (2015) suggested HTMT values under 0.85. All HTMT values are under the threshold.

Further, factor loadings of all items on their respective construct were measured and reported in Table 4. According to Bagozzi and Yi (1988), factor loading score of each of the item towards its respective construct should be above 0.50. Thus, items having a factor loading score less than 0.50 were removed and did not used for further data analysis.

TABLE 4.

Factor loadings, composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE)

| Variables | Loadings | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal service quality | |||

| ISQ1 | 0.587 | ||

| ISQ2 | 0.691 | ||

| ISQ3 | 0.751 | ||

| ISQ4 | 0.738 | ||

| ISQ5 | 0.716 | ||

| ISQ6 | 0.715 | ||

| ISQ7 | 0.782 | ||

| ISQ8 | 0.776 | ||

| ISQ9 | 0.678 | 0.904 | 0.814 |

| Employee's satisfaction | |||

| ES1 | 0.84 | ||

| ES2 | 0.859 | ||

| ES3 | 0.829 | ||

| ES4 | 0.828 | 0.905 | 0.774 |

| Employee's commitment | |||

| AC1 | 0.804 | ||

| AC2 | 0.792 | ||

| AC3 | 0.779 | ||

| AC4 | 0.855 | 0.883 | 0.653 |

| CC1 | 0.815 | ||

| CC2 | 0.86 | ||

| CC3 | 0.884 | 0.889 | 0.728 |

| Employee's well‐being | |||

| EW1 | 0.783 | ||

| EW2 | 0.779 | ||

| EW3 | 0.817 | ||

| EW4 | 0.808 | ||

| EW5 | 0.81 | ||

| EW6 | 0.837 | ||

| EW7 | 0.828 | ||

| EW8 | 0.798 | ||

| EW9 | 0.72 | 0.941 | 0.638 |

| Employee's Performance | |||

| EP1 | 0.737 | ||

| EP2 | 0.814 | ||

| EP3 | 0.66 | ||

| EP4 | 0.797 | ||

| EP5 | 0.801 | ||

| EP6 | 0.772 | ||

| EP7 | 0.823 | ||

| EP8 | 0.781 | 0.923 | 0.693 |

Table 4 presents the factor loadings, composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVEs) values of the constructs used in this study. Factor loadings and AVE's scores were more than 0.50, which empirically proved the convergent validity of all the constructs of the study. At the same time, composite reliability was greater than 0.8, indicated the acceptable level of CR of all the constructs of the study. Validity of the measure can be defined as the extent to which it is measuring what it is supposed to measure (Bordens & Abbott, 2008). Construct validity was checked by using convergent validity and discriminant validity. Convergent validity was checked through factor loadings, CR and AVEs. However, discriminant validity was analysed via comparing the square root of AVEs with relevant correlations where the square root of AVEs should be higher than the pertinent relationships. Overall, these results empirically proved the validity and reliability of all the constructs used in this study.

Table 5 represents model fit summary. RMSEA is connected with the residuals in the model.

TABLE 5.

Models fit summary

| Model | CMIN/DF | RMR | GFI | AGFI | PGFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold values suggested by Hair et al (2008) | Less than 3 | Less than 0.05 | Greater than 0.90 |

Greater than 0.80 |

Closer to 1 the better | Less than less than 0.08 |

| ES | 0.617 | 0.031 | 0.956 | 0.978 | 0.100 | 0.000 |

| EC | 1.309 | 0.024 | 0.978 | 0.825 | 0.372 | 0.059 |

| EW | 1.812 | 0.044 | 0.998 | 0.836 | 0.691 | 0.051 |

| EP | 2.442 | 0.034 | 0.959 | 0.845 | 0.100 | 0.044 |

The value of RMSEA ranges from 0 to 1; the smaller value of RMSEA shows a better fitness model. 0.06 Or less value of RMSEA indicates the acceptable model fitness (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The above table statistics indicate the goodness of fit test.

The model was executed by using Smart PLS 3.2.8 software to test all the proposed relationships of the study. This software is suitable for short sample size and for non‐normal data distribution as well. There are two conditions to be fulfilled for a variable to be a mediator. First, the exogenous variable should have a significant relationship with the mediator. Second, the mediator should have significant relation with an indigenous variable. According to Barron and Kenny (1986), the independent variable must have a significant relationship with the dependent variable. Mediation can also exist in the absence of significant relationships among exogenous and indigenous variables (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Interactive effects could diminish the overall independent and dependent variable (Mathieu & Taylor, 2006). For measuring the dependency among latent variables, three types of effects were assumed. Direct effect, indirect effect and total effects were calculated, where total effects mean a sum of the direct and indirect effect. All these three effects were investigated with their corresponding p‐value, beta values and t values as well as a confidence interval, which help to determine the acceptance/ rejection of the hypotheses of the study. The effect size of every dependent variable has also been reported in this study. Effect size is considered as the percentage of variance independent latent variable and explained by independent latent variable (Hayes & Preacher, 2010; Preacher & Hayes, 2004). The indirect effect explains the extent to which change in the independent variable brings change in dependent variable through the mediating variable. The direct effect is the extent to which change in the independent variable directly affects the dependent variable without a mediator.

Direct effects were used for hypotheses testing for the direct relationships. These effects were measured to find the dependency among the latent variables. ISQ has a direct and indirect impact of employee well‐being on employee performance, employee satisfaction and employee commitment. The result showed that ISQ has a significant direct effect on job satisfaction, employee commitment, employee well‐being and job performance. Further, the results reported in Table 6 indicated that employee well‐being mediated the direct relationship between employee satisfaction and job performance. However, the mediating role of employee well‐being between commitment and job performance was not empirically supported.

TABLE 6.

Results of hypotheses testing

| Direct relationship | b‐value | P values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISQ ‐>AC | 0.664 | <0.01 | Supported |

| ISQ ‐>CC | 0.562 | <0.01 | Supported |

| ISQ ‐>ES | 0.704 | <0.01 | Supported |

| ISQ ‐>EW | 0.204 | <0.01 | Supported |

| EW ‐>EP | 0.803 | <0.01 | Supported |

| AC ‐>EW | 0.325 | <0.01 | Supported |

| CC ‐>EW | 0.066 | <0.01 | Supported |

| ES ‐>EW | 0.404 | <0.01 | Supported |

| Indirect relationships | <0.01 | ||

| ES ‐> EW ‐> EP | 0.324 | <0.01 | Supported |

| CC ‐>EW‐> EP | 0.053 | <0.01 | Not supported |

5. DISCUSSION

First of all, study results showed that ISQ is one of the significant drivers of employees’ satisfaction and commitment in the private healthcare organizations operating in Pakistan. This study has contributed to the literature by investigating the impact of ISQ on nurses’ satisfaction, commitment, well‐being and job performance. A survey of 412 nurses from 20 private healthcare centres of Pakistan provides support to the hypotheses of the study. Results revealed that ISQ has a positive effect on employees’ satisfaction and commitment. Similarly, ISQ influenced employees’ well‐being, positively. The results of the study also revealed that employees’ well‐being positively mediated the impact of employees’ satisfaction on employees’ performance. Several factors can influence nurses’ job satisfaction, commitment, well‐being and job performance. In addition to the main hypotheses, the results also indicated that nurses’ age has a positive relationship with job performance in the healthcare sector. Nurses’ competencies increase with age (Karathanasi et al., 2014). Higher age leads towards higher job satisfaction and performance. So, these results supported the finding of previous studies (Curtis, 2008). Although gender roles are changing, nursing is still a predominantly female profession. Most studies on the relationships between employee satisfaction, employee commitment, employee well‐being and employee performance demonstrated sharply skewed samples towards females (Hasan & Aljunid, 2019; Tapela et al., 2015; Wong & Laschinger, 2015). Salary is a significant source of dissatisfaction among healthcare professionals (Hasan & Aljunid, 2019). The higher wage has a significant impact on the employees’ performance in the healthcare sector of Pakistan. All study findings have contributed to the current research on ISQ and its consequences by providing meaningful insights into the stressed process where ISQ impacts employees’ satisfaction, commitment, well‐being and performance, positively. Fewer studies indicated the development of employees’ satisfaction and commitment to job performance due to ISQ (Judge et al., 2001). Previous studies have proposed fairness perception, autonomy and employee well‐being might mediate the effect of job satisfaction on job performance (Shantz et al., 2013; Wright et al., 2007). Convincingly, the study enunciates on the employee well‐being as a focal construct which influences the employees’ satisfaction, commitment and performance (Danna & Griffin, 1999; Sparks et al., 2001).

Employee well‐being has a mediating effect on the relationship of employee satisfaction and commitment with job performance. Hence, this study fulfils the utmost research gap in extant research work on ISQ and its impact on subsequent attitudinal and behavioural outcomes of the employees. Moreover, it also urges researchers to consider employee well‐being as a part of any conceptual framework while studying employee attitudes and behaviours, especially in service sector. This study results indicated that employee satisfaction has a direct impact on employee performance. Similarly, employee commitment also influences employee performance directly. Also, the relationship of job satisfaction and job performance was further strengthened by using employee well‐being as mediating factor. Any organization needs to assess the service quality which is being provided by all concerned departments to each other. Management should find out the ways to enhance the ISQ at the individual level of employee along with departmental and working unit levels. ISQ is an essential factor in the service sector to achieve competitive advantage. Managers need to acknowledge its importance and to build mechanisms in their organization to analyse and measure ISQ. There is enormous work pressure on the employees in the healthcare sector. Therefore, healthcare centres management needs to encourage their employees through higher level of ISQ.

5.1. Study limitations

Despite its useful theoretical and managerial contributions, this study, like all other research studies, has some limitations. First, the current study was conducted in a single sector that is, healthcare and in a single region. Hence, the findings of this study may be influenced by the unique socio‐economic and cultural characteristics of this region and may not be equally applicable to other countries and regions. Future researchers are required to these the proposed relationships of this study in other industrial settings and in other regions to check the validity of the results of this study in different settings and different regions. Secondly, data were collected from private healthcare centres located in Pakistan. Further studies can consider a comparison between public and private healthcare centres to have more meaningful insights into the relationships investigated. Thirdly, the study examined employee perceptions towards various aspects of ISQ, but prior researches on service quality have also highlighted the prominence of expectations. Hence, future research on expectations and perceptions about ISQ can develop a comprehensive model with all its antecedents and consequences. In the last, this study has used cross‐sectional research design which limits the inference of causal relationships. Thus, future researchers are required to use longitudinal research design to establish cause and effect among the variables of the study.

6. CONCLUSIONS

This study contemplates the interconnection among ISQ, employees’ satisfaction, commitment along with well‐being which escalates the job performance, decisively, among the nursing employees working in the healthcare sector of Pakistan. In specific, the study proposed that ISQ positively influence job satisfaction, commitment and well‐being of the frontline nursing employees working in the healthcare sector of Pakistan. Further, this study also proposed that well‐being mediates the relationship of job satisfaction and commitment with job performance of the employees. Self‐administered survey was conducted with the participation of 412 frontline nursing employees which empirically confirmed all the main proposed relationships of the study.

In specific, the results revealed that ISQ has a positive effect on nurses’ satisfaction, commitment and well‐being, which in turn have positive effects on employee performance.. Further, nurses’ well‐being positively mediated the relationship of nurses’ satisfaction with their performance. However, the nurses’ well‐being did not mediate the relationship of nurses’ commitment with their job performance. These findings make a useful contribution to the literature around ISQ and its impact on employee attitudes and behaviours. Study results provide useful insights into the complex process by which internal service quality affects employee satisfaction, commitment, well‐being and performance.

6.1. Study implications

Internal service quality is vital source of employee satisfaction and commitment in service industries such as healthcare sector (Gremler et al., 1994; Hallowell et al., 1996; Heskett et al., 1994). Previous studies conclude mixed results about the impact of employee satisfaction and Job commitment on their performance. Current study shows that factors such as employee well‐being (Soane et al.,2013; Wright et al., 2007) may moderate job satisfaction on job performance. These results are previously supported by the studies of Soane et al., 2013; Wright et al., 2007. Current study has managerial implications as well. First, internal service quality is vital in the service sector. It highlights the need for manager's in service businesses to recognize its significance. Suitable mechanisms should be established by the managers to measure internal service quality on the regular bases. Development of cross‐functional teams can be used for internal service quality measurement. Secondly, sometimes employees are not aware about their rights. Usually, government has imposed labour regulations those neglected by the employers and employees. Employee can still monitor other performance because they are working in a team. In this study, employee satisfaction and commitment act as imperative driver of.

employee performance. Current study provides a useful insight to the management of the service sector organizations those are interest to improve employee satisfaction, commitment and performance by offering good quality of internal service at all levels.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All author provided substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author is grateful to the Editor and anonymous reviewers for their constructive and helpful comments and suggestions.

Abdullah MI, Dechun H, Sarfraz M, IVASCU L, Riaz A. Effects of internal service quality on nurses’ job satisfaction, commitment and performance: Mediating role of employee well‐being. Nurs Open.2021;8:607–619. 10.1002/nop2.665

Funding informationThis study was supported by Innovative Team of Philosophy and Social Sciences in Jiangsu Higher Learning Institutions “2017ZSTD002.”

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data are available upon request.

REFERENCES

- Adams, A. , & Bond, S. (2000). Hospital nurses’ job satisfaction, individual and organizational characteristics. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32(3), 536–543. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01513.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, N. , Iqbal, N. , Javed, K. , & Hamad, N. (2014). Impact of organizational commitment and employee performance on the employee satisfaction. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 1(1), 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, N. , Iqbal, N. , Javed, K. , Hamad, N. , Mirzabeigi, M. , Fardi, A. , & Azeem, M. (2017). Impact of organizational commitment and employee performance on the employee satisfaction. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 18(4), 1632–1636. [Google Scholar]

- Akdere, M. , Top, M. , & Tekingündüz, S. (2020). Examining patient perceptions of service quality in Turkish hospitals: The SERVPERF model. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 31(3–4), 342–352. 10.1080/14783363.2018.1427501 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen, D. , Weinhold, M. , Miller, J. , Joswiak, M. E. , Bursiek, A. , Rubin, A. , & Grubbs, P. (2015). Nurses as champions for patient safety and interdisciplinary problem solving. Medsurg Nursing, 24(2):107‐110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amram, Y. , & Dryer, C. (2008). The integrated spiritual intelligence scale (ISIS): Development and preliminary validation. In 116th annual conference of the American Psychological Association, Boston, MA (pp. 14–17).

- Ang, S. Y. , Uthaman, T. , Ayre, T. C. , Lim, S. H. , & Lopez, V. (2019). A Photovoice study on nurses’ perceptions and experience of resiliency. Journal of Nursing Management, 27(2), 414–422. 10.1111/jonm.12702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applebaum, D. , Fowler, S. , Fiedler, N. , Osinubi, O. , & Robson, M. (2010). The impact of environmental factors on nursing stress, job satisfaction and turnover intention. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 40, 323–328. 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3181e9393b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnetz, J. E. , Hamblin, L. , Essenmacher, L. , Upfal, M. J. , Ager, J. , & Luborsky, M. (2015). Understanding patient‐to‐worker violence in hospitals: A qualitative analysis of documented incident reports. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(2), 338–348. 10.1111/jan.12494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babic, A. , Gillis, N. , & Hansez, I. (2020). Work‐to‐family interface and well‐being: The role of workload, emotional load, support and recognition from supervisors. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 46(1), 1–13. 10.4102/sajip.v46i0.1628 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baek, H. K. , & Yang, M. H. (2017). Relationships between perceived stress, burnout and psychological well‐being of athletes: Testing of moderated mediation effect of ego‐resilience. The Korean Journal of Physical Education, 56(2), 125–143. 10.23949/kjpe.2017.03.56.2.9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R. P. , & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. 10.1007/BF02723327 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bai, B. , Brewer, K. P. , Sammons, G. , & Swerdlow, S. (2006). Job satisfaction, organizational commitment and internal service quality: A case study of Las Vegas hotel/casino industry. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 5(2), 37–54. 10.1300/J171v05n02_03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barron, R. M. , & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator‐mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, T. E. , Billings, R. S. , Eveleth, D. M. , & Gilbert, N. L. (1996). Foci and bases of employee commitment: Implications for job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 39(2), 464–482. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, L. L. (1981). The employee as customer. Journal of Retail Banking, 3(1), 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, L. , Mirabito, A. M. , & Baun, W. (2010). What’s the hard return on employee wellness programs? Harvard Business Review, 88(12):104‐112, 142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordens, K. S. , & Abbott, B. B. (2008). Research methods and design: A process approach. McGraw‐Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Boshoff, C. , & Mels, G. (1995). A causal model to evaluate the relationships among supervision, role stress, organizational commitment and internal service quality. European Journal of Marketing, 29(2), 23–42. 10.1108/03090569510080932 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon‐Jones, A. , & Silvestro, R. (2010). Measuring internal service quality: Comparing the gap‐based and perceptions‐only approaches. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 30(12), 1291–1318. 10.1108/01443571011094271 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.‐M. , & Fang, J.‐B. (2016). Correlation between nursing work environment and nurse burnout, job satisfaction and turnover intention in the western region of Mainland China. Hu Li Za Zhi, 63(1), 87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, C.‐F. , & Wu, K.‐P. (2014). The influences of internal service quality and job standardization on job satisfaction with supports as mediators: Flight attendants at branch workplace. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(19), 2644–2666. 10.1080/09585192.2014.884616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ching, P. P. S. , Nazarudin, M. N. , & Suppiah, P. K. (2019). The Relationship Between Organizational Commitment and Internal Service Quality Among the Staff in Majlis Sukan Negeri‐negeri in Malaysia. In International Conference on Movement, Health and Exercise (pp. 199‐205). Springer, Singapore.

- Churchill, G. A. Jr (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64–73. 10.1177/002224377901600110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, E. A. (2008). The effects of biographical variables on job satisfaction among nurses. British Journal of Nursing, 17(3), 174–180. 10.12968/bjon.2008.17.3.28406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danna, K. , & Griffin, R. W. (1999). Health and well‐being in the workplace: A review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of Management, 25(3), 357–384. 10.1177/014920639902500305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dressner, M. (2017). Hospital workers: An assessment of occupational injuries and illnesses. Monthly Labor Review.140 10.21916/mlr.2017.17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhart, K. H. , Witt, L. A. , Schneider, B. , & Perry, S. J. (2011). Service employees give as they get: Internal service as a moderator of the service climate–service outcomes link. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(2), 423 10.1037/a0022071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson, M. C. , & Logsdon, K. (2002). Determinants of job satisfaction of municipal government employees. Public Personnel Management, 31(3), 343–358. 10.1177/009102600203100307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eskildsen, J. K. , & Dahlgaard, J. J. (2000). A causal model for employee satisfaction. Total Quality Management, 11(8), 1081–1094. 10.1080/095441200440340 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farner, S. , Luthans, F. , & Sommer, S. M. (2001). An empirical assessment of internal customer service. Managing Service Quality, 11(5), 350–358. 10.1108/09604520110404077 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fatima, T. , Malik, S. A. , & Shabbir, A. (2018). Hospital healthcare service quality, patient satisfaction and loyalty. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 35(6), 1195–1214. 10.1108/IJQRM-02-2017-0031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, M. S. , & MacKinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233–239. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparito, R. C. , & Guilardello, E. B. (2015). Professional practice environment and burnout among nurses. Rev Rene, 16(1): 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Gregar, J. (1994). Research Design (Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches.Book published by SAGE Publications; 228 [Google Scholar]

- Gremler, D. D. , Bitner, M. J. , & Evans, K. R. (1994). The internal service encounter. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 5(2), 34–56. 10.1108/09564239410057672 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffeth, R. W. , Hom, P. W. , & Gaertner, S. (2000). A meta‐analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management, 26(3), 463–488. 10.1177/014920630002600305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grönroos, C. (1981). Internal marketing–an integral part of marketing theory. Marketing of Services, 236, 238. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, D. E. , & Conway, N. (2002). Communicating the psychological contract: An employer perspective. Human Resource Management Journal, 12(2), 22–38. 10.1111/j.1748-8583.2002.tb00062.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, M. , & Sharma, P. (2009). Job satisfaction level among employees: A case study of Jammu region. J&K. IUP Journal of Management Research, 8(5), 17. [Google Scholar]

- Hallowell, R. , Schlesinger, L. A. , & Zornitsky, J. (1996). Internal service quality, customer and job satisfaction: Linkages and implications for management. Human Resource Planning, 19(2), 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, D. A. , Newman, D. A. , & Roth, P. L. (2006). How important are job attitudes? Meta‐analytic comparisons of integrative behavioral outcomes and time sequences. Academy of Management Journal, 49(2), 305–325. 10.5465/amj.2006.20786077 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, H. , & Aljunid, S. M. (2019). Job satisfaction among Community‐Based Rehabilitation (CBR) workers in caring for disabled persons in the east coast region of Peninsular Malaysia. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 6520‐z 10.1186/s12889-019-6520-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. , & Preacher, K. J. (2010). Quantifying and testing indirect effects in simple mediation models when the constituent paths are nonlinear. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 45(4), 627–660. 10.1080/00273171.2010.498290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, B. , Douglas, C. , & Bonner, A. (2015). Work environment, job satisfaction, stress and burnout among haemodialysis nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 23(5), 588–598. 10.1111/jonm.12184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F. Jr , Black, W. C. , Babin, B. J. , & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Heinen, M. M. , van Achterberg, T. , Schwendimann, R. , Zander, B. , Matthews, A. , Kózka, M. , Ensio, A. , Sjetne, I. S. , Casbas, T. M. , Ball, J. , & Schoonhoven, L. (2013). Nurses’ intention to leave their profession: A cross sectional observational study in 10 European countries. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(2), 174–184. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J. , Ringle, C. M. , & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135. 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hitt, M. A. , Bierman, L. , Shimizu, K. , & Kochhar, R. (2001). Direct and moderating effects of human capital on strategy and performance in professional service firms: A resource‐based perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Homburg, C. , & Stock, R. M. (2004). The link between salespeople’s job satisfaction and customer satisfaction in a business‐to‐business context: A dyadic analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(2), 144–158. 10.1177/0092070303261415 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. T. , & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(2), 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado, D. A. , Dumet, L. M. , Greenspan, S. A. , Rodríguez, Y. I. , & Heinonen, G. A. (2018). Identifying safety peer leaders with social network analysis. Occupational Health Science, 2(4), 437–450. 10.1007/s41542-018-0026-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jalagat, R. (2016). Job performance, job satisfaction and motivation: A critical review of their relationship. International Journal of Advances in Management and Economics, 5(6), 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, S. A. , Liu, S. , Mahmoudi, A. , & Nawaz, M. (2019). Patients' satisfaction and public and private sectors' health care service quality in Pakistan: Application of grey decision analysis approaches. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 34(1), 168–182. 10.1002/hpm.2629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T. A. , Thoresen, C. J. , Bono, J. E. , & Patton, G. K. (2001). The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 127(3), 376 10.1037/0033-2909.127.3.376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karathanasi, K. , Prezerakos, P. , Maria, M. , Siskou, O. , & Kaitelidou, D. (2014). Operating room nurse manager competencies in Greek hospitals. Clinical Nursing Studies, 2(2), 16–29. 10.5430/cns.v2n2p16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kent, R. (2001). Data construction and data analysis for survey research. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, R. A. G. , Khan, F. A. , & Khan, M. A. (2011). Impact of training and development on organizational performance. Global Journal of Management and Business Research, 11(7). [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, M. (2001). Nursing migration: Global treasure hunt or disaster‐in‐the‐making? Nursing Inquiry, 8(4), 205–212. 10.1046/j.1440-1800.2001.00116.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinman, G. , & Johnson, S. (2019). Special section on well‐being in academic employees. International Journal of Stress Management, 26(2), 159 10.1037/str0000131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Labrague, L. J. , McEnroe‐Petitte, D. M. , & Tsaras, K. (2019). Predictors and outcomes of nurse professional autonomy: A cross‐sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 25(1), e12711 10.1111/ijn.12711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, K. J. , Noblet, A. J. , & Rodwell, J. J. (2009). Promoting employee wellbeing: The relevance of work characteristics and organizational justice. Health Promotion International, 24(3), 223–233. 10.1093/heapro/dap025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. S. , & Hasson, F. (2020). Resilience, stress and psychological well‐being in nursing students: A systematic review. Nurse Education Today, 90, 104440 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke, E. A. (1976). The nature and causes of job satisfaction. 1, 1297‐1343. Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 10.1207/s15427633scc0304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loveman, G. W. (1998). Employee satisfaction, customer loyalty and financial performance: An empirical examination of the service profit chain in retail banking. Journal of Service Research, 1(1), 18–31. 10.1177/109467059800100103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maharani, S. P. , Syah, T. Y. R. , & Negoro, D. A. (2020). Internal service quality as a driver of employee satisfaction, commitment and turnover intention exploring over focal role of employee well‐being. Journal of Multidisciplinary Academic, 4(3), 170–175. [Google Scholar]

- Masemola, S. E. (2011. ). Employee turnover intentions, organisational commitment and job satisfaction in a post‐merger tertiary institution: the case of the University of Limpopo. University of Limpopo (Turfloop Campus).

- Masum, A. K. M. , Azad, M. A. K. , Hoque, K. E. , Beh, L.‐S. , Wanke, P. , & Arslan, Ö. (2016). Job satisfaction and intention to quit: An empirical analysis of nurses in Turkey. PeerJ, 4, e1896 10.7717/peerj.1896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu, J. E. , & Taylor, S. R. (2006). Clarifying conditions and decision points for mediational type inferences in organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(8), 1031–1056. 10.1002/job.406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matzler, K. , & Renzl, B. (2006). The relationship between interpersonal trust, employee satisfaction and employee loyalty. Total Quality Management and Business Excellence, 17(10), 1261–1271. 10.1080/14783360600753653 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, D. J. , & Makin, P. J. (2000). The psychological contract, organisational commitment and job satisfaction of temporary staff. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 21(2), 84–91. 10.1108/01437730010318174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J. P. , Becker, T. E. , & Vandenberghe, C. (2004). Employee commitment and motivation: A conceptual analysis and integrative model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(6), 991 10.1037/0021-9010.89.6.991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, N. G. , Erickson, A. , & Yust, B. L. (2001). Sense of place in the workplace: The relationship between personal objects and job satisfaction and motivation. Journal of Interior Design, 27(1), 35–44. 10.1111/j.1939-1668.2001.tb00364.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mirabito, A. M. , & Berry, L. L. (2015). You say you want a revolution? Drawing on social movement theory to motivate transformative change. Journal of Service Research, 18(3), 336–350. 10.1177/1094670515582037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzabeigi, M. , Fardi, A. , Yousofi, H. R. , Norouzian, M. , Pariav, M. , Lak, S. , Radfard, M. , & Ebadi, A. (2018). Assessment of Job satisfaction of group of nurses in ava salamat entrepreneurs institute in Iran. Data in Brief, 18, 1632–1636. 10.1016/j.dib.2018.04.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorhead, G. , & Griffin, R. W. (2008). Organizational behavior managing people and organizations, New Delhi: Dreamtech Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mosadeghrad, A. M. (2014). Factors influencing healthcare service quality. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 3(2), 77–89. 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan, D. P. , & Pandey, S. K. (2007). Finding workable levers over work motivation: Comparing job satisfaction, job involvement and organizational commitment. Administration & Society, 39(7), 803–832. 10.1177/0095399707305546 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nazeer, S. , Zahid, M. M. , & Azeem, M. F. (2014). Internal service quality and job performance: Does job satisfaction mediate. Journal of Human Resources, 2(1), 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, M. , Nolan, J. , & Grant, G. (1995). Maintaining nurses’ job satisfaction and morale. British Journal of Nursing, 4(19), 1149–1154. 10.12968/bjon.1995.4.19.1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J. , Barnette, J. J. , & Peter, J. P. (1978). Reliability: A review of psychometric basics and recent marketing practices. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 6–17. [Google Scholar]

- Odeh, G. R. , & Alghadeer, H. R. (2014). The impact of organizational commitment as a mediator variable on the relationship between the internal marketing and internal service quality: An empirical study of five star hotels in Amman. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 6(3), 142–147. 10.5539/ijms.v6n3p142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pantouvakis, A. (2011). Internal service quality and job satisfaction synergies for performance improvement: Some evidence from a B2B environment. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 19(1), 11–22. 10.1057/jt.2011.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perry, S. J. , Richter, J. P. , & Beauvais, B. (2018). The effects of nursing satisfaction and turnover cognitions on patient attitudes and outcomes: A three‐level multisource study. Health Services Research, 53(6), 4943–4969. 10.1111/1475-6773.12997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, G. , & Srivastava, S. (2019). Role of internal service quality in enhancing patient centricity and internal customer satisfaction. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing, 13(1), 2–20. 10.1108/IJPHM-02-2018-0004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K. J. , & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717–731. 10.3758/BF03206553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putra, G. N. W. , Kurniati, T. , & Hidayat, A. A. A. (2017). Job Satisfaction and Nursing Performance through Career Development. In Health Science International Conference (HSIC 2017). Atlantis Press.

- Rahman, A. , Naqvi, S. , & Ramay, M. I. (2008). Measuring turnover intention: A study of it professionals in Pakistan. International Review of Business Research Papers, 4(3), 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Rantika, S. D. , & Yustina, A. I. (2017). Effects of ethical leadership on employee well‐being: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Journal of Indonesian Economy and Business, 32(2), 121–137. 10.22146/jieb.22333 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Renee Baptiste, N. (2008). Tightening the link between employee wellbeing at work and performance: A new dimension for HRM. Management Decision, 46(2), 284–309. 10.1108/00251740810854168 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richardsen, A. M. , Burke, R. J. , & Martinussen, M. (2006). Work and health outcomes among police officers: The mediating role of police cynicism and engagement. International Journal of Stress Management, 13(4), 555 10.1037/1072-5245.13.4.555 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, B. A. , & Brody, C. J. (2011). Operationalizing management citizenship behavior and testing its impact on employee commitment, satisfaction and mental health. Work and Occupations, 38(4), 465–499. 10.1177/0730888410397924 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rust, R. T. , Stewart, G. L. , Miller, H. , & Pielack, D. (1996). The satisfaction and retention of frontline employees: A customer satisfaction measurement approach. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 7(5), 62–80. 10.1108/09564239610149966 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, B. , White, S.S. and Paul, M.C. (1998), "Linking service climate and customer perceptions of service quality: tests of a causal model", Journal of Applied Psychology ,83 pp. 150‐163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shantz, A. , Alfes, K. , Truss, C. , & Soane, E. (2013). The role of employee engagement in the relationship between job design and task performance, citizenship and deviant behaviours. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(13), 2608–2627. 10.1080/09585192.2012.744334 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P. , Kong, T. T. C. , & Kingshott, R. P. (2016). Internal service quality as a driver of employee satisfaction, commitment and performance. Journal of Service Management, 27(5), 773–797. 10.1108/JOSM-10-2015-0294 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shazadi, A. , Nadeem, S. , Nisar, Q. A. , & Azeem, M. (2017). Do high performance work practices influence the job outcomes? Mediating role of organizational commitment & job satisfaction: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Advanced Biotechnology and Research, 8(4), 303–314. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, M. A. , & Price, S. W. (2002). Racial harassment, job satisfaction and intentions to quit: Evidence from the British nursing profession. Economica, 69(274), 295–326. 10.1111/1468-0335.00284 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout, P. E. , & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skevington, S. M. , Lotfy, M. , & O'Connell, K. A. (2004). The World Health Organization's WHOQOL‐BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Quality of Life Research, 13(2), 299–310. 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soane, E. , Shantz, A. , Alfes, K. , Truss, C. , Rees, C. and Gatenby, M. (2013), "The association of meaningfulness, well‐being, and engagement with absenteeism: a moderated mediation model", Human Resource Management, 52 pp. 441‐456. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, K. , Faragher, B. , & Cooper, C. L. (2001). Well‐being and occupational health in the 21st century workplace. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 74(4), 489–509. 10.1348/096317901167497 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spruce, L. (2015). Back to basics: Implementing evidence‐based practice. AORN Journal, 101(1), 106–114.e4. 10.1016/j.aorn.2014.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapela, N. M. , Bukhman, G. , Ngoga, G. , Kwan, G. F. , Mutabazi, F. , Dusabeyezu, S. , Mutumbira, C. , Bavuma, C. , & Rusingiza, E. (2015). Treatment of non‐communicable disease in rural resource‐constrained settings: A comprehensive, integrated, nurse‐led care model at public facilities in Rwanda. The Lancet Global Health, 3, S36 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70155-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tarcan, M. , Hikmet, N. , Schooley, B. , Top, M. , & Tarcan, G. Y. (2017). An analysis of the relationship between burnout, socio‐demographic and workplace factors and job satisfaction among emergency department health professionals. Applied Nursing Research, 34, 40–47. 10.1016/j.apnr.2017.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompa, E. , Dolinschi, R. , Alamgir, H. , Sarnocinska‐Hart, A. , & Guzman, J. (2016). A cost‐benefi t analysis of peer coaching for overhead lift use in the long‐term care sector in Canada. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 10.1136/oemed-2015-103134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, L. (2018). Relationship between meaningful work and job performance in nurses. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 24(2), 1–6. 10.1111/ijn.12620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torlak, N. G. , & Kuzey, C. (2019). Leadership, job satisfaction and performance links in private education institutes of Pakistan. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 68(2), 276–295. 10.1108/IJPPM-05-2018-0182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tovey, E. J. , & Adams, A. E. (1990). The changing nature of nurses’ job satisfaction: An exploration of sources of satisfaction in the 1990s. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 30(1), 150–158. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01059.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng, H.‐M. (2002a). Satisfying nurses on job factors they care about: A Taiwanese perspective. Journal of Nursing Administration, 32(6), 306–309. 10.1097/00005110-200206000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng, H.‐M. (2002b). The influence of nurses’ working motivation and job satisfaction on intention to quit: An empirical investigation in Taiwan. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 39(8), 867–878. 10.1016/S0020-7489(02)00027-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uğur GöK, A. , & Kocaman, G. (2011). Reasons for leaving nursing: A study among Turkish nurses. Contemporary Nurse, 39(1), 65–74. 10.5172/conu.2011.39.1.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanniarajan, T. , & Subbash Babu, K. (2011). Internal service quality and its consequences in commerical banks: A HR perspective. Global Management Review, 6(1).943–954. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. H. , & Li, C. Y. (2018). Should medical service industry in China implement the internal service recovery? Explore its moderation effect on internal service quality, employee satisfaction and employee loyalty. Journal of Management & Decision Sciences, 1(1).20–43. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, J. M. (1994). Dimensions that make a difference: Examining the impact of in‐role and extrarole behaviors on supervisory ratings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(1), 98–107. 10.1037/0021-9010.79.1.98 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, C. A. , & Laschinger, H. K. S. (2015). The influence of frontline manager job strain on burnout, commitment and turnover intention: A cross‐sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(12), 1824–1833. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, T. A. , Cropanzano, R. , & Bonett, D. G. (2007). The moderating role of employee positive well being on the relation between job satisfaction and job performance. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(2), 93 10.1037/1076-8998.12.2.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. , You, L. , Liu, K. , Zheng, J. , Fang, J. , Lu, M. , & Wang, S. (2014). The association of Chinese hospital work environment with nurse burnout, job satisfaction and intention to leave. Nursing Outlook, 62(2), 128–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.‐H. , Shi, Y. U. , Sun, Z.‐N. , Xie, F.‐Z. , Wang, J.‐H. , Zhang, S.‐E. , Gou, T.‐Y. , Han, X.‐Y. , Sun, T. , & Fan, L.‐H. (2018). Impact of workplace violence against nurses’ thriving at work, job satisfaction and turnover intention: A cross‐sectional study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(13–14), 2620–2632. 10.1111/jocn.14311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon request.