Teleophthalmology benefits from tremendous development since CoVid-19 pandemic. Teleconsultation based on remote anterior segment photo [1], [2], retinography [3], [4], optical coherence tomography or simple smartphone-based teleconsultation [5] passed from confidential practice reserved to war zones or remote areas to everyday practice. Teleconsultation in primary ophthalmic emergencies during the COVID-19 lockdown in Paris [6] illustrated ophthalmologists early response to patients sudden access loss to primary ophthalmology emergency care. The study demonstrated the ability of smartphone-based teleconsultation to properly evaluate the indication of a physical consultation (27% of patients undergoing teleconsultation were asked to consult physically afterwards) with 96% sensitivity, 95% specificity and only 1.0% identified misdiagnoses that lead to delayed care. Consequently, 73% of patients were managed only with teleconsultation and had direct phone access to the emergency department if their symptoms derogated to the practitioners’ recommendations.

Considering all patients did not have free and anonymous personal evaluation of their teleconsultation and following French Health Authority (Haute Autorité de Santé-HAS) recommendations for good clinical practice [7], we invited the 1901 patients who solicited a teleconsultation in April and May 2020 to evaluate their own experience. This survey permitted to evaluate false negatives and also to estimates patient's demography, main motivation to teleconsultation, satisfaction and further acceptance to new distancial medical practice.

In all, 176 patients voluntarily answered to the anonymous online survey [8]. 133 (76%) were women and mean age was 48.3 ± 14.5 years old, both indicators were slightly superior to 500 patients initial cohort. Patients main motivations were reduced time to consultation (37%), to avoid displacement (30%) and to avoid emergency department frequentation (22%); 13% patients were seeking for specialist second opinion following general practitioner consultation or pharmacist recommendations. 34% patients were oriented to physical consultation also slightly superior to the 27% of the 500 patients initial cohort (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Patients demographic and orientation.

| Total |

Female |

Male |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 176 | 133 (76%) | 43 (24%) | |||

| Age (years) | 48.3 (±14.5) | 49.2 (±13.9) | 45.8 (±16.2) | 173 | 0.22 | Welch |

| Location (Paris 0), n | ||||||

| Paris & suburb | 145 (82.3%) | 111 (83%) | 34 (79%) | 145 | 0.51 | Chi2 |

| Rest of France | 31 (17.7%) | 22 (17%) | 9 (21%) | 31 | – | – |

| Principal motivation | ||||||

| Reduce time to consultation | 64 (37%) | 47 (36%) | 17 (40%) | 64 | 1 | Fisher |

| Avoid displacement | 53 (30%) | 40 (31%) | 13 (30%) | 53 | – | – |

| Avoid emergency department frequentation | 38 (22%) | 28 (21%) | 10 (23%) | 38 | – | – |

| Other | 19 (11%) | 16 (12%) | 3 (7%) | 19 | – | – |

| Orientation after teleconsultation | ||||||

| Teleconsultation only | 116 (66%) | 91 (69%) | 25 (58%) | 116 | 0.14 | Chi2 |

| SOSOeil department | 38 (22%) | 24 (18%) | 14 (33%) | 38 | – | – |

| Other practitioner | 21 (12%) | 17 (13%) | 4 (9.3%) | 21 | – | – |

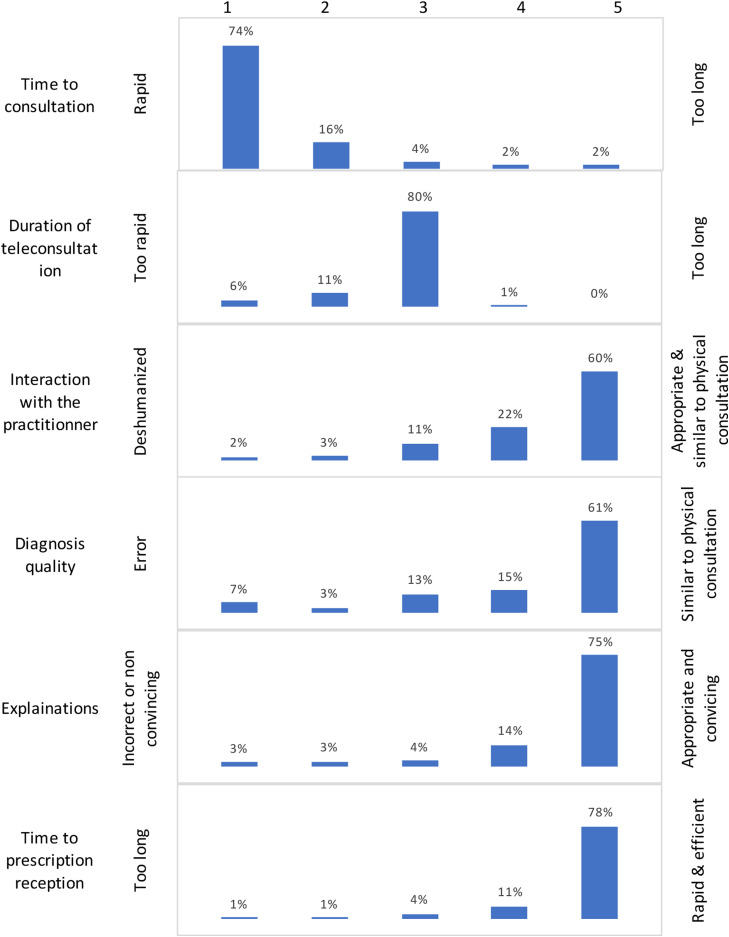

80% patients admitted they would privilege TC evaluation first in case of new ophthalmologic emergency independently from the pandemic situation and 84% would recommend TC to their family if appropriate (Table 2 ). Based on patients numerical evaluation scaled from 1 to 5 (Fig. 1 ), 74% of patients estimated the delay between TC request and the TC beginning was appropriate and 80% were totally satisfied of the TC duration. 75% where highly satisfied of the explanations given by the practitioner and 60% patients judged their interaction was comparable to physical consultation. 61% patients estimated their diagnosis was similar to physical consultation while 7% complained of diagnosis error caused by teleconsultation with 1 patient (0.6%) identified loss of chance (pan uveitis with 48 h PC consultation delay).

Table 2.

Patients evaluation of further teleconsultation.

| Total | Female | Male | n | P | Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seek for second opinion | No | 152 (87%) | 113 (86%) | 39 (93%) | 152 | 0.22 | Chi2 |

| In case of new emergency, would you privilege | |||||||

| Teleconsultation first | 140 (80%) | 101 (76%) | 39 (91%) | 140 | 0.15 | Fisher | |

| Physical consultation | 31 (18%) | 28 (21%) | 3 (7%) | 31 | – | – | |

| Depends on symptoms & circumstances | 5 (2.8%) | 4 (3%) | 1 (2.3%) | 5 | – | – | |

| Would you recommend a teleconsultation to your family | |||||||

| Yes | 148 (84%) | 106 (80%) | 42 (98%) | 148 | 0.021 | Fisher | |

| No | 15 (8.5%) | 15 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 15 | |||

| Depends on symptoms & circumstances | 13 (7.4%) | 12 (9%) | 1 (2.3%) | 13 | – | – |

In bold: p value < 0.05 (significant).

Figure 1.

Patients evaluation of their teleconsultation.

In conclusion, emergency teleophthalmology respond to a growing demand from patients for immediate access to primary ophthalmology care with satisfying and secure outcomes. Strict conditions for teleconsultation should be shared with the patient before the consultation begin and 27 to 34% of patients will have reasonable physical consultation for further evaluation.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

- 1.Blackwell N.A., Kelly G.J., Lenton L.M. Telemedicine ophthalmology consultation in remote Queensland. Med J Aust. 1997;167:583–586. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb138904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ribeiro A.G., Rodrigues R.A.M., Guerreiro A.M., Regatieri C.V.S. A teleophthalmology system for the diagnosis of ocular urgency in remote areas of Brazil. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2014;77:214–218. doi: 10.5935/0004-2749.20140055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Massin P., Chabouis A., Erginay A., Viens-Bitker C., Lecleire-Collet A., Meas T., et al. OPHDIAT: a telemedical network screening system for diabetic retinopathy in the Île-de-France. Diabetes Metab. 2008;34:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chasan J.E., Delaune B., Maa A.Y., Lynch M.G. Effect of a teleretinal screening program on eye care use and resources. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132:1045–1051. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mines M.J., Bower K.S., Lappan C.M., Mazzoli R.A., Poropatich R.K. The United States Army Ocular Teleconsultation program 2004 through 2009. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152 doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.01.028. [126-132.e2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourdon H., Jaillant R., Ballino A., El Kaim P., Debillon L., Bodin S., et al. Teleconsultation in primary ophthalmic emergencies during the COVID-19 lockdown in Paris: experience with 500 patients in March and April 2020. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2020;43:577–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2020.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Méthodes d’élaboration des recommandations de bonne pratique. Haute Autorité de Santé n.d. https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/c_418716/fr/methodes-d-elaboration-des-recommandations-de-bonne-pratique (accessed January 26, 2021).

- 8.Online survey: (https://docs.google.com/forms/d/14Z2KZc-Yts8sU9R7piLPhauA2v5uTWA3I7Nk0xAWXdk/edit). n.d.