Abstract

Background

Higher concentrations of seminal reactive oxygen species may be related to male infertility. Astaxanthin with high antioxidant activity can have an impact on the prevention and treatment of various health conditions, including cancer. However, efficacy studies on astaxanthin in patients with oligospermia with/without astheno- or teratozoospermia (O±A±T) have not yet been reported. Our aim was to evaluate the effect of the oral intake of astaxanthin on semen parameters.

Patients and methods

In a randomized double-blind trial, 80 men with O±A±T were allocated to intervention with 16 mg astaxanthin orally daily or placebo. At baseline and after three months basic semen parameters, sperm deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) fragmentation and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) of spermatozoa and serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) value were measured.

Results

Analysis of the results of 72 patients completing the study (37 in the study group, 35 in the placebo group) did not show any statistically significant change, in the astaxanthin group no improvements in the total number of spermatozoa, concentration of spermatozoa, total motility of spermatozoa, morphology of spermatozoa, DNA fragmentation and mitochondrial membrane potential of spermatozoa or serum FSH were determined. In the placebo group, statistically significant changes in the total number and concentration of spermatozoa were determined.

Conclusions

The oral intake of astaxanthin did not affect any semen parameters in patients with O±A±T.

Key words: antioxidant, male infertility, oligo-astheno-teratozoospermia, semen quality, DNA fragmentation, cancer

Introduction

Currently, almost every seventh couple is infertile. The male factor as the single or additional reason for infertility is presented in nearly 50% of infertile couples.1 World Health Organization (WHO) defines oligo-astheno-teratozoospermia (OAT) as the concentration and the proportions of motile and morphologically normal spermatozoa below the reference values.2

One of the many pathophysiological factors of male infertility are higher concentrations of seminal reactive oxygen species (ROS).3 The uncontrolled production of these molecules may be harmful to cells and different biomolecules such as carbohydrates, amino acids, proteins, lipids, and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), which can be damaged. ROS can have a negative influence on sperm function and quality4,5,6,7 due to the reduced motility of spermatozoa8, DNA damage9,10,11 and the impaired integrity of the cellular membrane.7,12,13 It was revealed that infertile men with low semen concentration, poor semen motility, and a high proportion of morphologically abnormal spermatozoa were associated with an increased risk of testicular cancer.14,15 Several antioxidants are present within the ejaculate as protection against excessive ROS-induced lipid peroxidation.16 It has been confirmed that antioxidant capacity in semen is decreased in infertile men and men with testicular cancer with a high ROS proportion, compared to men with a normal proportion of ROS.17,18,19

Sperm function tests have arisen as a supplement to standard semen analysis.20 The DNA integrity of spermatozoa has a critical impact in determining sperm competence21,22 which is related to ROS levels9,10 and can be measured by sperm DNA fragmentation (SDF) assays.21,22 A recent meta-analysis of 28 studies demonstrated that SDF is more accurate in determining the function of spermatozoa compared to conventional semen parameters.23 A study of apoptotic DNA fragmentation in human spermatozoa found a significant increase in apoptotic SDF in the semen of testicular cancer patients post-orchiectomy and in OAT patients compared to a control group of healthy men.24 In addition to DNA integrity, mitochondria have an important impact on cell function25, and the sperm mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) contributes some benefit to male fertility potential and sperm quality.26 Combined SDF and MMP may act as better predictors of natural conception than standard semen parameters.27

Regarding the role of seminal antioxidant capacity in male infertility, several trials on the impact of antioxidants on semen characteristics have been performed. The review of randomized and placebo-controlled trials affirmed the favorable impact of some types of antioxidants on different semen characteristics.28 Several studies have shown favorable effects, especially on the motility of spermatozoa.29,30,31,32,33,34 In some trials, antioxidant combinations (coenzyme Q10, vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium, zinc, L-carnitine, etc.) were assessed.35,36,37,38,39,40 The most recent Cohrane review shows that for couples attending fertility clinics, pregnancy rates and live births may be improved with antioxidant supplementation in subfertile males.41

As one of many antioxidants, ketocarotenoid astaxanthin has the potential to prevent and treat various diseases, including diabetes, liver and renal diseases, cancer, chronic inflammatory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, eye and skin diseases, metabolic syndrome, gastrointestinal diseases, and neurodegenerative diseases.42 Astaxanthin accumulates in the microalga Haematococcus pluvialis, and compared to vitamin E, this compound has up to 100 times higher antioxidant activity.43 Astaxanthin is a food supplement and widely available over-the-counter. Until now, there were two “in vitro” studies that first showed the positive effect of astaxanthin on sperm capacitation in 24 healthy, fertile men44; subsequently, the positive effect on sperm capacitation in 27 men from couples who did not succeed to conceive after at least twelve months of regular unprotected intercourse was confirmed.45 On the other hand, there has been only one clinical trial investigating the influence of astaxanthin on male fertility published until now. The trial included a low number of patients with a history of male infertility – 11 patients in the study group and 19 patients in the placebo group; however, these patients were enrolled without regard for semen characteristics.46 Favorable changes in inhibin B concentration, sperm linear velocity and ROS levels, and pregnancy rate were determined. However, the efficacy of astaxanthin oral intake on semen parameters in OAT patients treated for infertility has not yet been reported.

The aim of this prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial was to assess the effect of three-month intake of astaxanthin in infertile men with oligospermia with/without astheno- or teratozoospermia (O±A±T) on basic semen parameters, DNA fragmentation and mitochondrial membrane potential of spermatozoa, and serum level of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

Patients and methods

The prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial was performed from November 2014 to January 2019 at the outpatient infertility clinic, Department of Human Reproduction, Division of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the University Medical Centre Ljubljana, Slovenia. The study was approved by the Slovenian National Medical Ethics Committee (consent number 145/02/14) and was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02310087. All participants were enrolled after they provided written informed consent to participate in the trial.

Participants

A total of 80 infertile men with O±A±T were enrolled after they signed a written informed consent to participate in this trial. They were considered O±A±T after at least two previous semen analysis (seminogram) and andrological examination in the frame of their infertility treatment after their partner being unable to conceive for at least 12 months of unprotected sexual intercourse or after a failed assisted conception procedure. Semen quality was defined as O±A±T according to the WHO 2010 guidelines: oligospermia (O) − sperm concentration < 15 million/ml; asthenozoospermia (A) − progressive motility of spermatozoa < 32%; teratozoospermia (T) − < 4% spermatozoa with normal morphology.20 The exclusion criteria were smoking more than 20 cigarettes per day, genetic causes of infertility, endocrinopathies, genital tract infections, undescended testis, systemic diseases, history of testicular cancer and treatment with other drugs and food supplements, such as antioxidants, during the last three months before enrolling in this study.

Intervention and methods

Eighty eligible infertile men with O±A±T were allocated at random to daily intake of 16 mg of astaxanthin capsules (Astasan) or placebo capsules, both produced by the same manufacturer (Sensilab). Astaxanthin capsules contained astaxanthin, vitamin E as a stabilizer, safflower oil, gelatin, water and glycerine. Placebo capsules were identical both in appearance and taste, containing gelatine, water and glycerine only. A computerized randomization table was used for the purpose of randomization. A random allocation sequence was generated and participants were enrolled and assigned to interventions by a third party, thus ensuring that both the enrolled participants and researchers were blinded. At baseline and after three months of treatment, all participants answered a questionnaire about their age, height, weight, smoking status and the history of current occupational exposure to high temperatures, ultraviolet or radiology radiation, chemicals, or a predominant sedentary job in order to exclude the potential effect of these factors on semen quality. The semen samples were obtained by masturbation after 2−5 days of sexual abstinence. Semen quality was assessed according to the WHO guidelines.20 The total number, concentration, motility and morphology were determined by international standard laboratory microscopic analyses.47

Sperm DNA fragmentation in our study was evaluated using a TUNEL assay – measuring DNA fragmentation in spermatozoa using terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase (TdT)-mediated dUTP nick-end labelling.48 The calculated threshold value for the TUNEL assay to distinguish between normal and abnormal semen samples in men was 20%.49 MMP was measured by means of 3,3’-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC6(3)) staining as an indicator of mitochondrial membrane integrity and the mitochondrial potential capacity to generate ATP by oxidative phosphorylation.50 Propidium iodide (PI) was used as a supravital fluorescent dye and stained spermatozoa were analyzed by flow cytometry. MMP was considered to be normal in our laboratory setting when the proportion of spermatozoa with normal MMP (attributed to cells with high fluorescence signals) was higher than 60%.27 The serum level of FSH was measured by a solid-phase, two-site chemiluminescent immunometric assay. The normal FSH values for males in our laboratory setting were 0.7−11.1 IU/L.

Sample size calculation

To estimate the sample size for the study, we anticipated an increase in sperm concentration in the astaxanthin group, as reported in the only clinical study until now.46 With the assumption of a 34% increase as reported, with alpha 0.05 and power 80%, 32 cases were needed in each group. To account for drop-outs, we aimed to recruit 40 cases in each group.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS), version 25, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA. An independent Student’s t-test was used to analyze normally distributed data, and the Mann-Whitney test was used to analyze data that were not distributed normally. A paired t-test or the Wilcoxon test were applied to analyze the differences in the semen variables within groups. The chi-square test was applied to compare the exposure to occupational factors between groups. The results of continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± SD. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

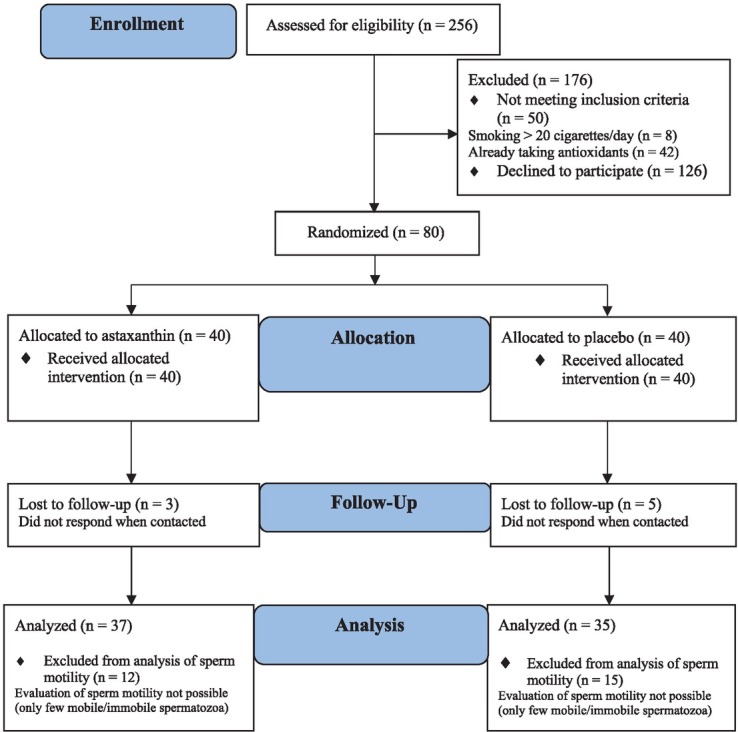

A group of 256 men was assessed for eligibility; half (126 men, 49.2%) declined to participate, and 50 did not meet the inclusion criteria; 80 men were eligible and willing to participate and these individuals were randomized. Eight patients in both groups (10%) dropped out for personal reasons during the treatment, and thus, 72 patients completed the trial. No adverse effects during the treatment were reported. Finally, we analyzed the effect of treatment in 37 patients in the astaxanthin and 35 patients in the placebo group (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow chart of study presenting the inclusion criteria, randomization and follow-up of participants.

Five patients were not included in the statistical analyses on changes in sperm total number and concentration and 27 patients were not includ ed in the statistical analyses on the motility of spermatozoa as in these patients only a few mobile or immobile spermatozoa in the semen sample were present. At baseline, all patients in the astaxanthin group were in accordance with WHO criteria for OAT. In the placebo group, all patients were in accordance with the WHO criteria for oligo-teratozoospermia and two-thirds for asthenozoospermia.

The epidemiological and semen characteristics of the included patients are summarized in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between all parameters of both groups of patients upon enrollment. In addition, exposure of patients to chemicals, ultraviolet rays, X-ray radiation, high temperature, and a sedentary job according to their history (questionnaire) have not been related to the semen parameters in the studied population of men.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics of patients in astaxanthin and placebo groups

| Characteristic | Astaxanthin (n = 37) | Placebo (n = 35) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 35.0 ± 5.2 | 36.4 ± 5.5 | 0.276 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.9 ± 3.8 | 27.1 ± 4.6 | 0.162 |

| Smoking (no. of cigarettes smoked / day) | 4.8 ± 6.8 | 3.6 ± 6.8 | 0.264 |

| Sperm concentration (million /ml)* | 6.9 ± 5.7 | 5.4 ± 5.8 | 0.297 |

| Total sperm number (million/ejaculate)* | 23.9 ± 28.4 | 15.6 ± 21.0 | 0.164 |

| Total sperm motility (%)** | 29.9 ± 14.8 | 38.2 ± 14.8 | 0.063 |

| Progressive sperm motility (%)** | 25.1 ± 14.5 | 33.3 ± 14.6 | 0.063 |

| Sperm morphology (%) | 1.8 ± 2.1 | 1.9 ± 2.0 | 0.663 |

| Sperm head defect (%) | 95.1 ± 16.2 | 97.5 ± 3.3 | 0.936 |

| Sperm neck + midpiece defect (%) | 2.9 ± 16.4 | 0.2 ± 0.8 | 0.981 |

| Sperm tail defect (%) | 0.2 ± 0.6 | 0.5 ± 1.0 | 0.424 |

| Leukocytes with peroxidase (million/ml) | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.976 |

| Mitochondrial membrane potential (%)*** | 27.5 ± 18.5 | 26.9 ± 15.3 | 0.888 |

| DNA fragmentation (%) | 50.5 ± 23.9 | 45.8 ± 21.8 | 0.424 |

| FSH (IU/l) | 9.7 ± 7.8 | 9.2 ± 5.8 | 0.919 |

| Chemicals at work (% exposed) | 5.4 | 14.3 | 0.204 |

| Ultraviolet rays at work (% exposed) | 2.7 | 0 | 0.327 |

| X-ray at work (% exposed) | 0 | 11.4 | 0.051 |

| High temperature at work (% exposed) | 13.5 | 14.3 | 0.925 |

| Sedentary job (% exposed) | 45.9 | 40.0 | 0.611 |

Results are presented as average (± SD) or percentage (%). Differences at baseline assessed with independent Student t-test, Mann-Whitney U-test or Chi-square test, as appropriate.

BMI = body mass index; DNA = deoxyribonucleic acid; FSH = follicle-stimulating hormone

= the analysis for total sperm number and sperm concentration was made for 34/37 patients from the astaxanthin group and 35/35 patients from the placebo group, since the excluded patients only had a few mobile or immobile spermatozoa in the semen sample;

= the analysis for total and progressive sperm motility was made for 25/37 patients from the astaxanthin group and 20/35 patients from placebo group, since the excluded patients only had a few mobile or immobile spermatozoa in the semen sample;

= the proportion of spermatozoa with normal MMP;

The pre- and post-treatment semen parameters and hormonal levels of both groups of patients are displayed in Table 2. The three-month treatment of patients with astaxanthin did not affect the semen parameters or serum FSH levels in any way. Interestingly, the significant change after the three-month period was the increased total number (16.0 ± 21.1 vs. 38.4 ± 69.2 million/ejaculate, p = 0.002) and concentration (5.7 ± 5.9 vs. 10.2 ± 15.7 million/ml, p = 0.024) of spermatozoa in the placebo group, but not in the astaxanthin group (24.6 ± 28.6 vs. 31.7 ± 33.4 million/ejaculate, p = 0.186, and 7.0 ± 5.6 vs. 9.2 ± 7.9 million/ml, p = 0.100).

Table 2.

Comparison of basic semen parameters, sperm MMP, DNA fragmentation, serum FSH values in astaxanthin and placebo groups after three-month treatment period

| Parameter | Astaxanthin (n = 37) | Placebo (n = 35) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | After 3 months | p-value | Baseline | After 3 months | p-value | |

| Sperm concentration (million /ml)* | 7.0 ± 5.6 | 9.2 ± 7.9 | 0.100 | 5.7 ± 5.9 | 10.2 ± 15.7 | 0.024 |

| Total sperm number (million/ejaculate)* | 24.6 ± 28.6 | 31.7 ± 33.4 | 0.186 | 16.0 ± 21.1 | 38.4 ± 69.2 | 0.002 |

| Total sperm motility (%)** | 32.3 ± 14.0 | 37.9 ± 14.7 | 0.172 | 38.0 ± 15.0 | 43.1 ± 12.8 | 0.164 |

| Progressive sperm motility (%)** | 27.3 ± 14.0 | 33.0 ± 14.7 | 0.171 | 33.1 ± 14.7 | 38.1 ± 12.8 | 0.176 |

| Sperm morphology (%) | 1.8 ± 2.1 | 1.6 ± 1.4 | 0.471 | 1.9 ± 2.0 | 2.0 ± 1.7 | 0.913 |

| Sperm head defect (%) | 95.1 ± 16.2 | 97.8 ± 2.2 | 0.785 | 97.5 ± 3.3 | 97.2 ± 2.7 | 0.836 |

| Sperm neck + midpiece defect (%) | 2.9 ± 16.4 | 0.2 ± 0.7 | 0.916 | 0.2 ± 0.8 | 0.3 ± 0.8 | 0.472 |

| Sperm tail defect (%) | 0.2 ± 0.6 | 0.4 ± 0.9 | 0.253 | 0.5 ± 1.0 | 0.5 ± 0.9 | 0.872 |

| Leukocytes with peroxidase (million/ml) | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.7 | 0.155 | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 0.365 |

| Mitochondrial membrane potential (%)*** | 27.5 ± 18.5 | 26.3 ± 18.5 | 0.375 | 26.9 ± 15.3 | 27.1 ± 15.9 | 0.925 |

| DNA fragmentation (%) | 50.5 ± 23.9 | 51.2 ± 17.9 | 0.958 | 45.8 ± 21.8 | 49.8 ± 16.9 | 0.116 |

| FSH IU/l) | 9.7 ± 7.8 | 10.0 ± 8.3 | 0.200 | 9.2 ± 5.8 | 9.7 ± 6.5 | 0.345 |

Results presented as average (±SD) or percentage (%). Differences within groups between baseline and after 3 months assessed with paired t-test and Wilcoxon test, as appropriate.

DNA = deoxyribonucleic acid; FSH = follicle-stimulating hormone

= the analysis for total sperm number and sperm concentration was made for 33/37 patients from the astaxanthin group and 34/35 patients from the placebo group, since the excluded patients only had a few mobile or immobile spermatozoa in the semen sample;

= the analysis for total and progressive sperm motility was made for 22/37 patients from the astaxanthin group and 16/35 patients from the placebo group, since the excluded patients only had a few mobile or immobile spermatozoa in the semen sample;

the proportion of spermatozoa with normal sperm mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP);

To address the increase in the concentration of spermatozoa in the placebo group, we separately analyzed the seasonal inclusion of patients into the trial to review the potential seasonal changes of semen quality. Nineteen patients in the astaxanthin group and 18 patients in the placebo group were enrolled in the study during the winter/spring period, and 18 patients in the astaxanthin group and 17 patients in the placebo group were enrolled during the summer/fall seasons. There was no significant difference in the seasonal inclusion of patients in the trial (p = 0.995).

Discussion

The present study is the first study of astaxanthin efficacy on semen parameters in oligo-asthenoteratozoospermic patients who were treated for infertility. Our results did not show any significant improvements in the basic semen parameters or at the cellular level (SDF, MMP) or serum FSH values after oral intake of astaxanthin. In previously published studies on the effects of antioxidants in semen quality28,32,38,39, the semen quality was defined according to the WHO 1999 guidelines. On the other hand, our patients were included based on their semen quality in line with the WHO 2010 guidelines, which have lower threshold values. Therefore, our patients were enrolled in the study with considerably poorer semen quality compared to patients in previous studies, which followed older WHO guidelines. Considering cancer patients, both chemotherapy and radiation have measurable effects on the sperm number, motility, morphology, and DNA integrity.51 Although treatment usually represents the greatest threat to the fertility of male survivors, the underlying malignancy may additionally affect semen production and quality. In cases of testicular cancer, the rates of oligospermia and azoospermia at presentation are 50% and 10%, respectively.52,53,54,55 Similarly, Hodgkin Lymphoma is associated with oligospermia and azoospermia before the treatment, and depending on the treatment regimen, also after.56,57,58 According to poor starting values of basic sperm parameters in our patients, in addition to their low MMP and very high DNA fragmentation, it can be concluded that our patients, in general, had poorer semen quality as subjects in the previous studies due to the lower threshold of the new WHO guidelines.

Under these conditions, our study revealed that antioxidant astaxanthin could not improve semen quality in cases of very poor semen quality, which could also be of great importance for cancer patients.

Our results are in contrast to a previous study by Comhaire, which determined favorable changes in the inhibin B concentration, sperm linear velocity and ROS levels, and pregnancy rate after astaxanthin treatment in the same dosage of astaxanthin as in our study. However, the study enrolled a low number of infertile males (11 in the study group and 19 in the placebo group) and was not based on semen analysis but rather on a more than twelve months’ infertility history of female partners having no verifiable cause of infertility.46 Interestingly, another recent study, similar to our study, showed that different antioxidants did not affect the semen quality in a larger group of infertile patients.59 Similar results of no effect of antioxidants were found in some other studies.38,60,61,62,63 These data show that antioxidants are interesting, but the clinical data should be comprehended with prudence.

The improved total number and concentrations of spermatozoa after three months of treatment with a placebo could reflect the beneficial psychological effect of placebo on patients. In the literature, the strength of expectations is connected to the degree of the placebo effect.64,65 The appearance of a medication, past experience, verbal information, and relationship between a patient and physician may influence the patient’s expectations.66 However, previously published reviews on the effects of oral antioxidants on semen quality did not show any positive effect of the placebo in the placebo-controlled studies.28,67

On average, the FSH value in the studied population was relatively high thus indicating the imbalance of the pituitary-gonadal endocrine axis and hypogonadism with a serious damage of spermatogenesis. In infertile men, a higher concentration of FSH is considered to be a reliable indicator of germinal epithelial damage, and was shown to be associated with azoospermia and severe oligozoospermia.68 This indicates that the studied population of men in our study was facing severe male infertility (severe OAT).

The advantage of our prospective, double-blind study includes the good randomization of patients for astaxanthin or placebo treatment. At baseline, both groups were comparable by their characteristics. We included patients based on their previous seminograms, and they were all clinically examined by an experienced andrologist. Additionally, strict exclusion criteria were used. Besides, this is the first clinical study of the efficacy of astaxanthin oral intake on semen parameters in severe oligo-astheno-teratozoospermic patients treated for infertility. The number of patients included is higher compared to similar placebo-controlled studies of other antioxidants.32,39,69,70 Astaxanthin group was homogenous because all patients accorded with WHO 2010 criteria for O+A+T. In the placebo group, two-thirds of patients also met the criteria for O+A+T; the average progressive motility of spermatozoa was just above the reference value (33.1 ± 14.7%), but the average total motility of spermatozoa was below the reference value. Therefore, the placebo group was also considered to be homogenous. Nevertheless, our study had some limitations, since one-third of patients had only a few mobile or immobile spermatozoa during the semen analysis; therefore, the measurements and statistical analysis for the total number, concentration and motility of spermatozoa in these patients were not possible. In addition, a relatively high proportion of patients declined to participate in this study.

As our study was performed with humans who gave consent to participate, it is our ethical obligation to also report the results with no evidence of an effect.71,72 Also, our study delivers an important fact that the clinical study on the astaxanthin effect in oligo-astheno-teratozoospermia was carried out. Unreported or unpublished negative findings introduce a bias in meta-analysis.73 Last but not least, the results could be an important part of future scientifically fair and flawless meta-analyses and reviews of the effects of antioxidants in infertile men.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the oral intake of 16 mg astaxanthin daily for three months did not significantly improve the semen parameters in patients with oligo-astheno-teratozoospermia compared to placebo. Our findings are important for the treatment and counselling on possible improvements in semen quality and fertilizing potential in infertile, and also post-testicular cancer patients. As a wide range of different antioxidant supplements is available, including astaxanthin, these findings are also significant concerning the efficacy of supplements in the treatment of male infertility.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Branko Zorn, Saso Drobnic, Mojca Kolbezen Simoniti, Ivan Verdenik, Natasa Petkovsek, Sara Hajdarevic, and registered nurses of the Division of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University Medical Centre Ljubljana, Slovenia, and Andreja Natasa Kopitar from the Institute for Microbiology and Immunology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ljubljana for their assistance in the study. The authors are grateful to manufacturer Sensilab, Ljubljana, Slovenia, for the donation of astaxanthin and placebo capsules.

Disclosure

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Sharlip ID, Jarow JP, Belker AM, Lipshultz LI, Sigman M, Thomas AJ. Best practice policies for male infertility. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:873. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03105-9. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper TG, Noonan E, von Eckardstein S, Auger J, Baker HW, Behre HM. World Health Organization reference values for human semen characteristics. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16:231. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp048. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desai N, Sharma R, Makker K, Sabanegh E, Agarwal A. Physiologic and pathologic levels of reactive oxygen species in neat semen of infertile men. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1626. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.109. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rivlin J, Mendel J, Rubinstein S, Etkovitz N, Breitbart H. Role of hydrogen peroxide in sperm capacitation and acrosome reaction. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:518. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.020487. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agarwal A, Virk G, Ong C, du Plessis SS. Effect of oxidative stress on male reproduction. World J Mens Health. 2014;32:1. doi: 10.5534/wjmh.2014.32.1.1. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darbandi M, Darbandi S, Agarwal A, Sengupta P, Durairajanayagam D, Henkel R. Reactive oxygen species and male reproductive hormones. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018;16:87. doi: 10.1186/s12958-018-0406-2. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gosalvez J, Tvrda E, Agarwal A. Free radical and superoxide reactivity detection in semen quality assessment: past, present, and future. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017;34:697. doi: 10.1007/s10815-017-0912-8. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kao SH, Chao HT, Chen HW, Hwang TI, Liao TL, Wei YH. Increase in oxidative stress in human sperm with lower motility. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:1183. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.05.029. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agarwal A, Ahmad G, Sharma R. Reference values of reactive oxygen species in seminal ejaculates using chemiluminescence assay. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015;32:1721. doi: 10.1007/s10815-015-0584-1. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aitken RJ, De Iuliis GN, Finnie JM, Hedges A, McLachlan RI. Analysis of the relationships between oxidative stress, DNA damage and sperm vitality in a patient population: development of diagnostic criteria. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:2415. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq214. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verit FF, Verit A, Kocyigit A, Ciftci H, Celik H, Koksal M. No increase in sperm DNA damage and seminal oxidative stress in patients with idiopathic infertility. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2006;274:339. doi: 10.1007/s00404-006-0172-9. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aitken RJ, Clarkson JS, Fishel S. Generation of reactive oxygen species, lipid peroxidation, and human sperm function. Biol Reprod. 1989;41:183. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod41.1.183. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agarwal A, Saleh RA, Bedaiwy MA. Role of reactive oxygen species in the pathophysiology of human reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:829. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04948-8. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobsen R, Bostofte E, Engholm G, Hansen J, Olsen JH, Skakkebaek NE. Risk of testicular cancer in men with abnormal semen characteristics: cohort study. BMJ. 2000;3:789. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7264.789. et al. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raman JD, Nobert CF, Goldstein M. Increased incidence of testicular cancer in men presenting with infertility and abnormal semen analysis. J Urol. 2005;174:1819. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000177491.98461.aa. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma RK, Agarwal A. Role of reactive oxygen species in male infertility. Urology. 1996;48:835. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(96)00313-5. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith R, Vantman D, Ponce J, Escobar J, Lissi E. Total antioxidant capacity of human seminal plasma. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:1655. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019465. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pahune PP, Choudhari AR, Muley PA. The total antioxidant power of semen and its correlation with the fertility potential of human male subjects. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:991. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/4974.3040. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sposito C, Camargo M, Tibaldi DS, Barradas V, Cedenho AP, Nichi M. Antioxidant enzyme profile and lipid peroxidation products in semen samples of testicular germ cell tumor patients submitted to orchiectomy. Int Braz J Urol. 2017;43:644. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538. et al. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. WHO Laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen 5th edition. Geneva: WHO Press;; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shamsi MB, Imam SN, Dada R. Sperm DNA integrity assays: diagnostic and prognostic challenges and implications in management of infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2011;28:1073. doi: 10.1007/s10815-011-9631-8. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammadeh ME, Al-Hasani S, Rosenbaum P, Schmidt W, Fischer Hammadeh C. Reactive oxygen species, total antioxidant concentration of seminal plasma and their effect on sperm parameters and outcome of IVF/ICSI patients. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;277:515. doi: 10.1007/s00404-007-0507-1. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santi D, Spaggiari G, Simoni M. Sperm DNA fragmentation index as a promising predictive tool for male infertility diagnosis and treatment management – meta-analyses. Reprod Biomed Online. 2018;37:315. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.06.023. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gandini L, Lombardo F, Paoli D, Caponecchia L, Familiari G, Verlengia C. Study of apoptotic DNA fragmentation in human spermatozoa. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:830. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.4.830. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piomboni P, Focarelli R, Stendardi A, Ferramosca A, Zara V. The role of mitochondria in energy production for human sperm motility. Int J Andro. 2012;35:109. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2011.01218.x. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marchetti P, Ballot C, Jouy N, Thomas P, Marchetti C. Influence of mitochondrial membrane potential of spermatozoa on in vitro fertilization outcome. Andrologia. 2012;44:136. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2010.01117.x. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malić Vončina S, Golob B, Ihan A, Kopitar AN, Kolbezen M, Zorn B. Sperm DNA fragmentation and mitochondrial membrane potential combined are better for predicting natural conception than standard sperm parameters. Fertil Steril. 2016;105:637. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.11.037. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imamovic Kumalic S, Pinter B. Review of clinical trials on effects of oral antioxidants on basic semen and other parameters in idiopathic oligoasthenoteratozoospermia. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:426951. doi: 10.1155/2014/426951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piomboni P, Gambera L, Serafini F, Campanella G, Morgante G, De Leo V. Sperm quality improvement after natural anti-oxidant treatment of asthenoteratospermic men with leukocytospermia. Asian J Androl. 2008;10:201. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2008.00356.x. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Safarinejad MR. Effect of pentoxifylline on semen parameters, reproductive hormones, and seminal plasma antioxidant capacity in men with idiopathic infertility: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Int Urol Nephrol. 2011;43:315. doi: 10.1007/s11255-010-9826-4. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Safarinejad MR, Safarinejad S, Shafiei N, Safarinejad S. Effects of the reduced form of coenzyme Q10 (ubiquinol) on semen parameters in men with idiopathic infertility: a double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized study. J Urol. 2012;188:526. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.03.131. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alizadeh F, Javadi M, Karami AA, Gholaminejad F, Kavianpour M, Haghighian HK. Curcumin nanomicelle improves semen parameters, oxidative stress, inflammatory biomarkers, and reproductive hormones in infertile men: a randomized clinical trial. Phytother Res. 2018;32:514. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5998. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banihani SA. Effect of ginger (Zingiber officinale) on semen quality. Andrologia. 2019;51:e13296. doi: 10.1111/and.13296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jannatifar R, Parivar K, Roodbari NH, Nasr-Esfahani MH. Effects of N-acetylcysteine supplementation on sperm quality, chromatin integrity and level of oxidative stress in infertile men. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2019;17:24. doi: 10.1186/s12958-019-0468-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lipovac M, Bodner F, Imhof M, Chedraui P. Comparison of the effect of a combination of eight micronutrients versus a standard mono preparation on sperm parameters. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2016;4:84. doi: 10.1186/s12958-016-0219-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tremellen K, Miari G, Froiland D, Thompson J. A randomized control trial examining the effect of an antioxidant (Menevit) on pregnancy outcome during IVF-ICSI treatment. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;47:216. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2007.00723.x. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ghanem H, Shaeer O, El-Segini A. Combination clomiphene citrate and antioxidant therapy for idiopathic male infertility: a randomized controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:2232. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.117. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raigani M, Yaghmaei B, Amirjannti N, Lakpour N, Akhondi MM, Zeraati H. The micronutrient supplements, zinc sulphate and folic acid, did not ameliorate sperm functional parameters in oligoasthenoteratozoospermic men. Andrologia. 2014;46:956. doi: 10.1111/and.12180. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamamoto Y, Aizawa K, Mieno M, Karamatsu M, Hirano Y, Furui K. The effects of tomato juice on male infertility. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2017;26:6571. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.102015.17. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Busetto GM, Agarwal A, Virmani A, Antonini G, Ragonesi G, Del Giudice F. Effect of metabolic and antioxidant supplementation on sperm parameters in oligo-astheno-teratozoospermia, with and without varicocele: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Andrologia. 2018;50:e12927. doi: 10.1111/and.12927. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smits RM, Mackenzie-Proctor R, Yazdani A, Stankiewicz MT, Jordan V, Showell MG. Antioxidants for male subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3:CD007411. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007411.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yuan JP, Peng J, Yin K, Wang JH. Potential health-promoting effects of astaxanthin: a high-value carotenoid mostly from microalgae. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011;55:150. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201000414. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miki W. Biological functions and activities of animal carotenoids. Pure Appl Chem. 1991;63:141. doi: 10.1351/pac199163010141. –. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dona G, Kozuh I, Brunati AM, Andrisani A, Ambrosini G, Bonanni G. Effect of astaxanthin on human sperm capacitation. Mar Drugs. 2013;11:1909. doi: 10.3390/md11061909. et al. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andrisani A, Donà G, Tibaldi E, Brunati AM, Sabbadin C, Armanini D. Astaxanthin improves human sperm capacitation by inducing lyn displacement and activation. Mar Drugs. 2015;13:5533. doi: 10.3390/md13095533. et al. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Comhaire FH, El Garem Y, Mahmoud A, Eertmans F, Schoonjans F. Combined conventional/antioxidant “Astaxanthin” treatment for male infertility: a double blind, randomized trial. Asian J Androl. 2005;7:257. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2005.00047.x. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Björndahl L, Barratt CLR, Mortimer D, Jouannet P.. ‘How to count sperm properly’: checklist for acceptability of studies based on human semen analysis. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:227. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev305. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Franco JG. Baruffi RL, Mauri AL, Petersen CG, Oliveira JB, Vagnini L. Significance of large nuclear vacuoles in human spermatozoa: implications for ICSI. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008;17:42. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60291-x. Jr. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sergerie M, Laforest G, Bujan L, Bissonnette F, Bleau G. Sperm DNA fragmentation: threshold value in male fertility. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:3446. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei231. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Armstrong JS, Rajasekaran M, Chamulitrat W, Gatti P, Hellstrom WJ, Sikka SC. Characterization of reactive oxygen species induced effects on human spermatozoa movement and energy metabolism. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26:869. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00275-5. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Colpi GM, Contalbi GF, Nerva F, Sagone P, Piediferro G. Testicular function following chemo-radiotherapy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;13(1):S2. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2003.11.002. Suppl. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pont J, Albrecht W. Fertility after chemotherapy for testicular germ cell cancer. Fertil Steril. 1997;68:1. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)81465-3. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fossa SD, Aass N, Molne K. Is routine pre-treatment cryopreservation of semen worthwhile in the management of patients with testicular cancer? Br J Urol. 1989;64:524. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1989.tb05292.x. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Horwich A, Nicholls EJ, Hendry WF. Seminal analysis after orchiectomy in stage I teratoma. Br J Urol. 1988;62:79. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1988.tb04272.x. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Berthelsen JG. Sperm counts and serum follicle-stimulating hormone levels before and after radiotherapy and chemotherapy in men with testicular germ cell cancer. Fertil Steril. 1984;41:281. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)47605-3. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rueffer U, Breuer K, Josting A, Lathan B, Sieber M, Manzke O. Male gonadal dysfunction in patients with Hodgkin’s disease prior to treatment. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:1307. doi: 10.1023/a:1012464703805. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van der Kaaij MA, Heutte N, Echten AJV, Raemaekers JMM, Carde P, Noordijk EM. Sperm quality before treatment in patients with early stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma enrolled in EORTC-GELA lymphoma group trials. Haematologica. 2009;94:1691. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.009696. et al. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Viviani S, Ragni G, Santoro A, Perotti L, Caccamo E, Negretti E. Testicular dysfunction in Hodgkin’s disease before and after treatment. Eur J Cancer. 1991;27:1389. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(91)90017-8. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steiner A, Hansen K, Diamond MP, Coutifaris C, Cedars M, Legro R. Antioxidants in the treatment of male factor infertility: results from double blind, multi-center, randomized controlled males, antioxidants, and infertility (MOXI) trial. [abstract O-064] Abstracts of the 34th annual meeting of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. 2018;33(1):i30. et al. In. Hum Reprod. Supp. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Donnelly ET, McClure N, Lewis SE. Antioxidant supplementation in vitro does not improve human sperm motility. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:484. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00267-8. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Safarinejad MR, Shafiei N, Safarinejad S. A prospective double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study of the effect of saffron (Crocussativus Linn.) on semen parameters and seminal plasma antioxidant capacity in infertile men with idiopathic oligoasthenoteratozoospermia. Phytother Res. 2011;25:508. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3294. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rafiee B, Morowvat MH, Rahimi-Ghalati N. Comparing the effectiveness of dietary vitamin C and exercise interventions on fertility parameters in normal obese men. Urol J. 2016;13:2635. –. PMID: 27085565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bozhedomov VA, Lipatova NA, Bozhedomova GE, Rokhlikov IM, Shcherbakova EV, Komarina RA. Using L- and acetyl-L-carnintines in combination with clomiphene citrate and antioxidant complex for treating idiopathic male infertility: a prospecitive randomized trial. Urologia. 2017;3:22. doi: 10.18565/urol.2017.3.22-32. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kirsch I. How expectancies shape experience. Washington: American Psychological Association;; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bjørkedal E, Flaten MA. Interaction between expectancies and drug effects: an experimental investigation of placebo analgesia with caffeine as an active placebo. Psychopharmacology. 2011;215:537. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2233-4. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Benedetti F. Placebo-effects: understanding the mechanisms in health and disease. Oxford: Oxford University Press;; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ahmadi S, Bashiri R, Ghadiri-Anari A, Nadjarzadeh A. Antioxidant supplements and semen parameters: an evidence based review. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2016;14:729. –. PMID: 28066832. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bergmann M, Behre HM, Nieschlag E. Serum FSH and testicular morphology in male infertility. Clin Endocrinol. 1994;40:133. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1994.tb02455.x. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kumar R, Saxena V, Shamsi MB, Venkatesh S, Dada R. Herbo-mineral supplementation in men with idiopathic oligoasthenoteratospermia: a double blind randomized placebo- controlled trial. Indian J Urol. 2011;27:357. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.85440. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nadjarzadeh A, Shidfar F, Amirjannati N, Vafa MR, Motevalian SA, Gohari MR. Effect of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on antioxidant enzymes activity and oxidative stress of seminal plasma: a double-blind randomised clinical trial. Andrologia. 2014;46:177. doi: 10.1111/and.12062. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sandercock P. Negative results: why do they need to be published? Int J Stroke. 2012;7:32. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00723.x. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mlinarić A, Horvat M, Šupak Smolčić V. Dealing with the positive publication bias: why you should really publish your negative results. Biochem Med. 2017;27:030201. doi: 10.11613/BM.2017.030201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hart B, Duke D, Lundh A, Bero L. Effect of reporting bias on meta-analyses of drug trials: reanalysis of meta-analyses. BMJ. 2012;344:d7202. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]