Abstract

Background:

Evidence regarding the association between HIV viral load (VL) and hypertension is inconsistent. In this study, we investigated the relationship using viremia copy-years (VCY), a cumulative measure of HIV plasma viral burden.

Methods:

Data were analyzed for 686 PLWH in the Florida Cohort Study, who had at least five years of VL data before the baseline. VL data were extracted from Enhanced HIV/AIDS Reporting System (eHARS) and used to define peak VL (pVL), recent VL (rVL), and undetectable VL (uVL: rVL<50copies/mL). A five-year VCY (log10 copy × years/mL) before the baseline investigation, was calculated and divided into 5 groups (<2.7, 2.7–3.7. 3.8–4.7, 4.8–5.7 and >5.7) for analysis. Hypertension was determined based on hypertension diagnosis from medical records. Multivariable logistic regression was used for association analysis.

Results:

Of the total sample, 277 (40.4%) participants were hypertensive. Compared to the participants with lowest VCY (<2.7 log10 copy × years/mL), the odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence interval [95% CI] for hypertension of the remaining four groups, in order, were 1.91 [1.11, 3.29], 1.91 [1.03, 3.53], 2.27 [1.29, 3.99], and 1.25 [0.65, 2.42], respectively, controlling for confounders. The association was independent of pVL, rVL, and uVL, each of which was not statistically significant associations with hypertension.

Conclusion:

Persistent HIV infection is a risk factor for hypertension among PLWH. Information provided by VCY is more effective than single time-point VL measures in investigating HIV infection-hypertension relationship. The findings of this study support the significance of continuous viral suppression in hypertension prevention among PLWH.

Keywords: Cumulative viremia, copy-years, hypertension, HIV, viral load, virological suppression

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic health conditions have emerged as a new health challenge for persons living with HIV (PLWH), along with the success of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and increases in survival after HIV diagnosis [1–5]. As a common risk factor for cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), hypertension is prevalent among PLWH [5–15] and increases with an incidence ranging from 26–220 per 1000 person-years [7, 16–23]. Plasma HIV viral load (VL) or HIV RNA is used as an integral clinical indicator in patient care and an independent predictor of HIV infection-related morbidity and mortality in research [24–28]. The effect of plasma HIV RNA has largely been ascribed to the sustained de novo viral replication, which is responsible for the irreversible damage to the immune system, inflammatory responses, and immune system activation [29–31].

The risk of hypertension among people with HIV is attributable to a combination of the traditional risk factors, HIV-specific factors, and side effects of ART agents [11, 14, 20, 32–36]. HIV infection has been related to some potential mechanisms of hypertension, such as immune activation and chronic low-grade inflammation [37–41]. The pro-inflammatory effects of HIV infection on vascular endothelium activate reactive oxygen species that further induce endothelial damage, vasoconstriction, reduced endothelium-dependent relaxation, and vascular stiffness [37, 38, 42–44]. Other pathophysiologic mechanisms for hypertension include microbial translocation, immune suppression/ reconstitution, viral tropism, lipodystrophy, adipokines, and HIV-related renal disease [20, 44–47]. Some studies suggest that successful HIV virological suppression was associated with the improvement of immune function, reduction of systemic inflammatory markers, and reduction in CVD events [48]. However, a careful examination of the findings revealed that the epidemiological evidence supporting the association between HIV VL and hypertension is either limited or inconsistent [37, 49, 50]. More research is needed to advance our understanding of the relationship between HIV infection and the risk of hypertension to develop evidence-based and effective intervention strategies for hypertension prevention among PLWH.

One issue common among the published studies is that HIV infection in these studies was often measured with viral load data collected at one point in time, such as peak VL (pVL), recent VL (rVL), undetectable viral load (uVL) and viral suppression [37, 49–51]. Relative to single time-point measures, a cumulative measure of VL may be more effective to reflect the process of systemic inflammation and immune activation after HIV infection [29]. Therefore, a cumulative measure may be more relevant than a single time-point measure to examine the relationship between HIV infection and hypertension.

Repeated VL measures from diverse sources make it possible for researchers to derive cumulative measures of long-term exposure to viral replication. One typical measure is the viremia copy-years (VCY). As the term indicates, VCY measures HIV infection by summing up VL measured at multiple time points over time. It provides a proxy of cumulative HIV viremia, and is a strong predictor of all-cause mortality among PLWH [52–55]. In theory, VCY may also be associated with hypertension [29], yet no reported studies have used this measure in hypertension research among PLWH. We conducted this study with an attempt to fill the data gap.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Setting and Participants

This is a secondary analysis of data extracted from the Florida Cohort Study (http://sharc-research.org/). The Florida Cohort Study is an NIH-funded project to identify influential factors to improve HIV care outcomes with a diverse sample of PLWH. Participants were enrolled between 2014–2017 from multiple HIV clinics and community settings across the State of Florida, including Lake City, Gainesville, Tampa, Orlando, Sanford, Ft. Lauderdale, and Miami. Detailed information of this cohort has been previously described [56, 57].

With the assistance of the Florida Department of Health, survey data collected by the Florida Cohort Study were linked with laboratory data on VL and CD4+ T cell counts in the Enhanced HIV/AIDS Reporting System (eHARS) and data on hypertension diagnosis, antiretroviral medications, antihypertensive medication, and height and weight in the medical record.

We included participants who had been diagnosed with HIV for at least 5 years prior to the baseline investigation, who had at least 2 HIV viral load test results during the 5 years, and who had data to ascertain hypertension diagnosis. Hypertension was defined using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9: 401.xx). In order to avoid secondary hypertension and hypertension-related comorbidities confounding the potential association between hypertension and VCY, we excluded patients with secondary hypertension and relevant comorbidities, including hypertensive heart disease (402.xx), hypertensive renal disease (403.xx) hypertensive heart and renal disease (404.xx) and secondary hypertension (405.xx). Finally, a total of 686 participants were included in this study.

Written informed consent was obtained from individual participants of the Florida Cohort study. Approval of this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at the University of Florida, Florida International University, and the Florida Department of Health.

2.2. Definition and Calculation of VCY

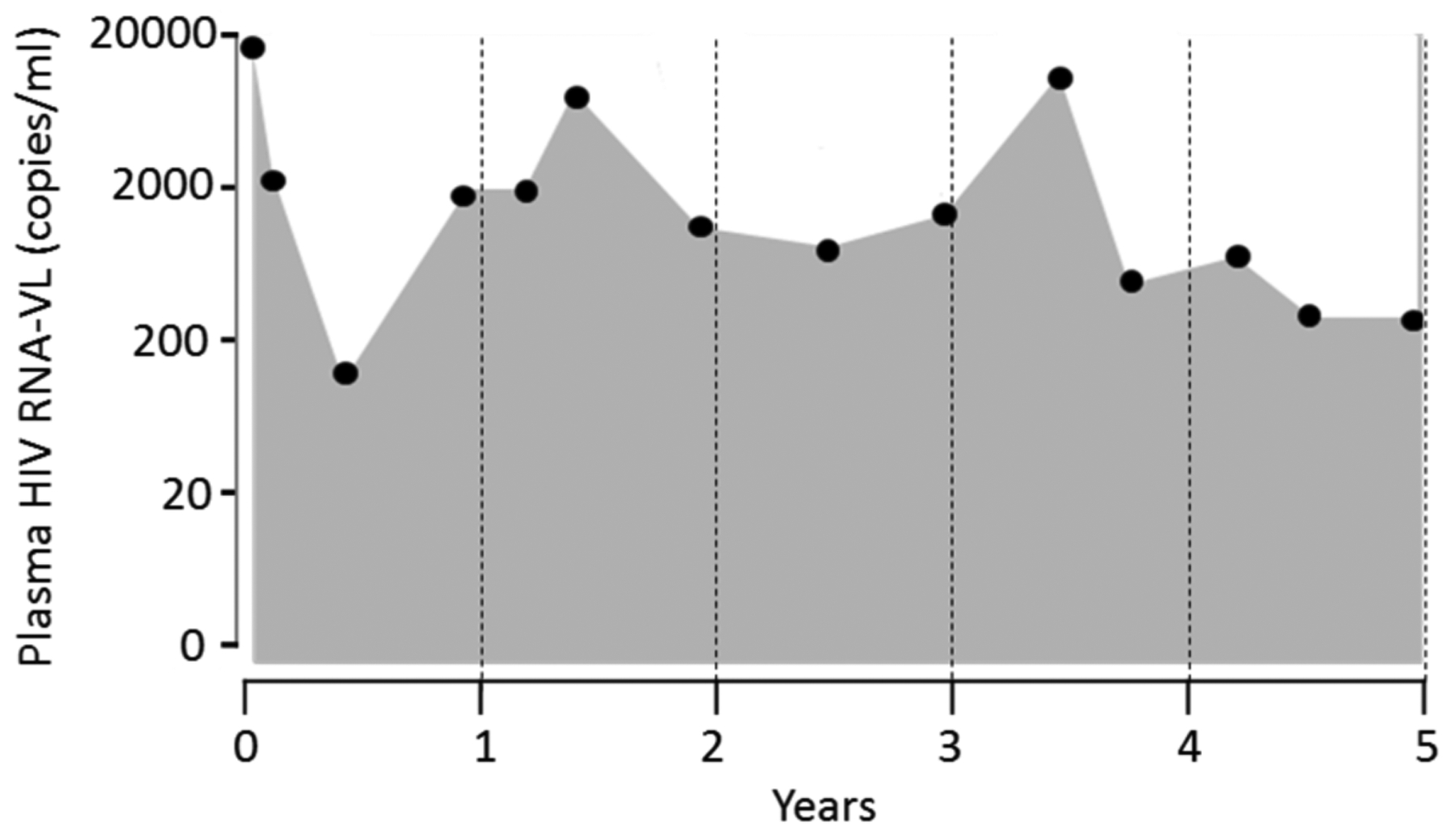

VCY was the primary predictor variable and it was calculated based on the VL measures over 5 years prior to the baseline. The calculation was completed following the standard method by summing up the areas under the VL time series using the trapezoidal rule (Fig. 1) [55, 58, 59]. Since the number of visits J, the timing of visits t(j) and VL value at time j VL(j) vary by participant, VCY was estimated using the following formula and expressed in copies × years per milliliter (cells × years/ml):

| (1) |

Fig. (1).

Example calculation of 5-year viremia copy-years.

The calculated VCY provided a monotonic increasing measure of cumulative plasma HIV viremia over time. Thus, VCY for a participant can thus be described as the sum of areas for each trapezoid consisting of 2 consecutive VL values and the time interval between the 2 VL measures (Fig. 1). A person with a VCY of 10,000 copy-years is equivalent to being exposed to 10,000 copies per milliliter of VL each day for 1 year or 1000 copies per milliliter VL each day for 10 years of HIV-RNA.

We selected 5 years because findings of a previously reported study showed that VCY calculated using time intervals of 3–8 years better-predicted mortality risk than complete VL history and single time-point VL measures [53].

2.3. Other HIV Infection Measures

Three more HIV infection measures were used. The peak viral load (pVL) was defined as the maximum value of VL since confirmed HIV diagnosis. The recent viral load (rVL) was defined as the VL measurement closest to the baseline investigation. Undetectable viral load (uVL) was defined as rVL< 50 copies/mL. These three measures were used as secondary predictors to be compared with VCY in predicting hypertension.

2.4. Other Variables

The CD4+ T-cell count closest to the baseline investigation was extracted from eHARS for analysis. The duration of HIV diagnosis was a difference of years between HIV diagnosis and baseline investigation. Depression was defined based upon the depression diagnosis from medical records. Other covariates were collected through questionnaires (age, gender, race/ethnicity, current smoking, and drinking) or extracted from their medical records (diabetes, status of antiretroviral therapy, and the use of antihypertensive medications). Heavy drinkers was defined as >14 drinks/week for male, and >7 drinks/week for female.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Participants with and without hypertension were compared first using Student t-test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. Correlations between VCY, pVL, rVL, and uVL were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation. Separate multivariable logistic regression models for different VL measures were constructed to examine their associations with hypertension. In addition to continuous VCY, the categorized VCY in five groups was analyzed with four cutoffs: 2.7 log10 (500 copy-years), 3.7 log10 (5,000 copy-years), 4.7 log10 (50,000 copy-years), and 5.7 log10 (500,000 copy-years). Likewise, pVL was categorized into five groups with cutoffs of 2.3 log10 (200 copies/mL), 3.3 log10 (2,000 copies/mL), 4.3 log10 (20,000 copies/mL), and 5.3 log10 (200,000 copies/mL), and rVL was categorized into four groups with cutoffs of 1.3 log10 (20 copies/mL), 2.3 log10 (200 copies/mL), and 3.3 log10 (2,000 copies/mL).

In the multivariate logistic regression analyses, the following covariates were controlled: age, sex, race/ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic-black, and other), and other variables significantly associated with hypertension in bivariate analysis, including BMI (kg/m2), diabetes, CD4+ count (≥500 vs. <500 cells/mm3), and years of HIV infection (>10 vs. ≤10 years).

To avoid the potential confounding effects of antihypertensive medications, a sensitivity analysis was performed with patients categorized into three groups: no-hypertension, hypertension treated, and hypertension untreated. We employed multinominal logistic regression to test the association with CVY for hypertension treated vs. no hypertension and hypertension untreated vs. no hypertension. In the last step of the analysis, a logistic regression model with all four VL measures (i.e. VCY, pVL, rVL, and uVL) being included was constructed to assess the independent association of VCY with -hypertension after considering the effect of other three single time-point VL measures.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. A total of 686 participants were included in this study. Among 277 hypertensive participants, 178 (64.3%) used antihypertensive medications. The mean age was 46.8 (SD=11.2) years and more than half were males. The median VCY was 4.4 log10 copy × year/mL [Interquartile range (IQR): 3.0, 5.4 log10 copy × year/mL]. The medians of pVL and the rVL were 3.0 log10 copies/mL [IQR: 2.0, 3.0 log10 copies/mL] and 1.3 log10 copies/mL [IQR: 1.3, 2.2 log10 copies/mL] respectively. Of all participants, 450 (65.6%) had viral load undetectable. Compared with normotensive participants, those with hypertension were older and more likely to be black and female (p<0.05). Hypertensive participants had higher BMI, CD4+ T cell counts, and VCY, and longer years living with a diagnosis of HIV than normotensives (p<0.01).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Variables | Participants (n=686) | Hypertensive (n=277) | Normotensive (n=409) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | <0.01 | |||

| Male | 442 (64.4) | 162 (58.5) | 280 (68.5) | |

| Female | 244 (35.6) | 115 (41.5) | 129 (31.5) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | <0.01 | |||

| Non-Hispanic whites | 151 (22.0) | 44 (15.9) | 69 (16.6) | |

| Non-Hispanic blacks | 395 (57.6) | 44 (15.9) | 107 (26.2) | |

| Hispanics | 112 (16.3) | 185 (66.8) | 210 (51.3) | |

| Others | 28 (4.1) | 4 (1.4) | 24 (6.9) | |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 0.24 | |||

| Yes | 351 (51.2) | 134 (48.4) | 217 (53.1) | |

| No | 335 (48.8) | 143 (51.6) | 192 (46.9) | |

| Heavy drinking, n (%) | 0.34 | |||

| Yes | 63 (9.2) | 29 (10.5) | 34 (8.3) | |

| No | 623 (90.8) | 248 (89.5) | 375 (91.7) | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | <0.01 | |||

| Yes | 88 (12.8) | 63 (22.7) | 25 (6.11) | |

| No | 598 (87.2) | 214 (77.3) | 384 (93.9) | |

| Depression | 0.54 | |||

| Yes | 99 (14.5) | 42 (15.2) | 59 (14.5) | |

| No | 585 (85.5) | 235 (84.8) | 350 (85.6) | |

| CD4 (cells/mm3), n (%) | 0.02 | |||

| ≥500 | 355 (51.3) | 158 (57.0) | 197(48.2) | |

| <500 | 331 (48.7) | 119 (43.0) | 212 (51.8) | |

| Currently on ART, n (%) | 0.74 | |||

| Yes | 593 (86.4) | 238 (85.9) | 355 (86.8) | |

| No | 93 (13.6) | 39 (14.1) | 54 (13.2) | |

| Undetectable viral load, n (%) | 0.48 | |||

| Yes | 450 (65.6) | 186 (67.2) | 264(64.6) | |

| No | 236 (34.4) | 91 (32.8) | 145 (35.4) | |

| Use of antihypertensive medications | ||||

| Yes | - | 178 (64.3) | - | - |

| No | - | 99 (35.) | - | - |

| Age, mean (SD) | No | 50.5 (9.7) | 44.4(11.4) | <0.01 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 28.3 (7.1) | 29.9 (7.3) | 27.1 (6.6) | <0.01 |

| Years of HIV infection, median (IQR) | 10 (5,17) | 13 (7, 18) | 10 (4, 15) | <0.01 |

| pVL (log10 copies/mL), median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0, 3.0) | 3.0 (2.0, 3.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 0.36 |

| rVL (log10 copies/mL), median (IQR) | 1.3 (1.3, 2.2) | 1.3 (1.3, 2.0) | 1.3 (1.3, 2.3) | 0.76 |

| VCY (log10 copy × year/mL), median (IQR) | 4.4 (3.0, 5.4) | 4.7 (3.0,6.3)) | 4.2 (2.9, 5.3) | <0.01 |

Note: ART: antiretroviral therapy; BMI: Body Mass Index; IQR Interquartile Range; SD: Standard Deviation; pVL: Peak Viral Load; rVL: the most Recent Viral Load; uVL: undetectable viral load; VCY: Viremia Copy-years.

3.2. Correlations of VCY, rVL, pVL, and uVL

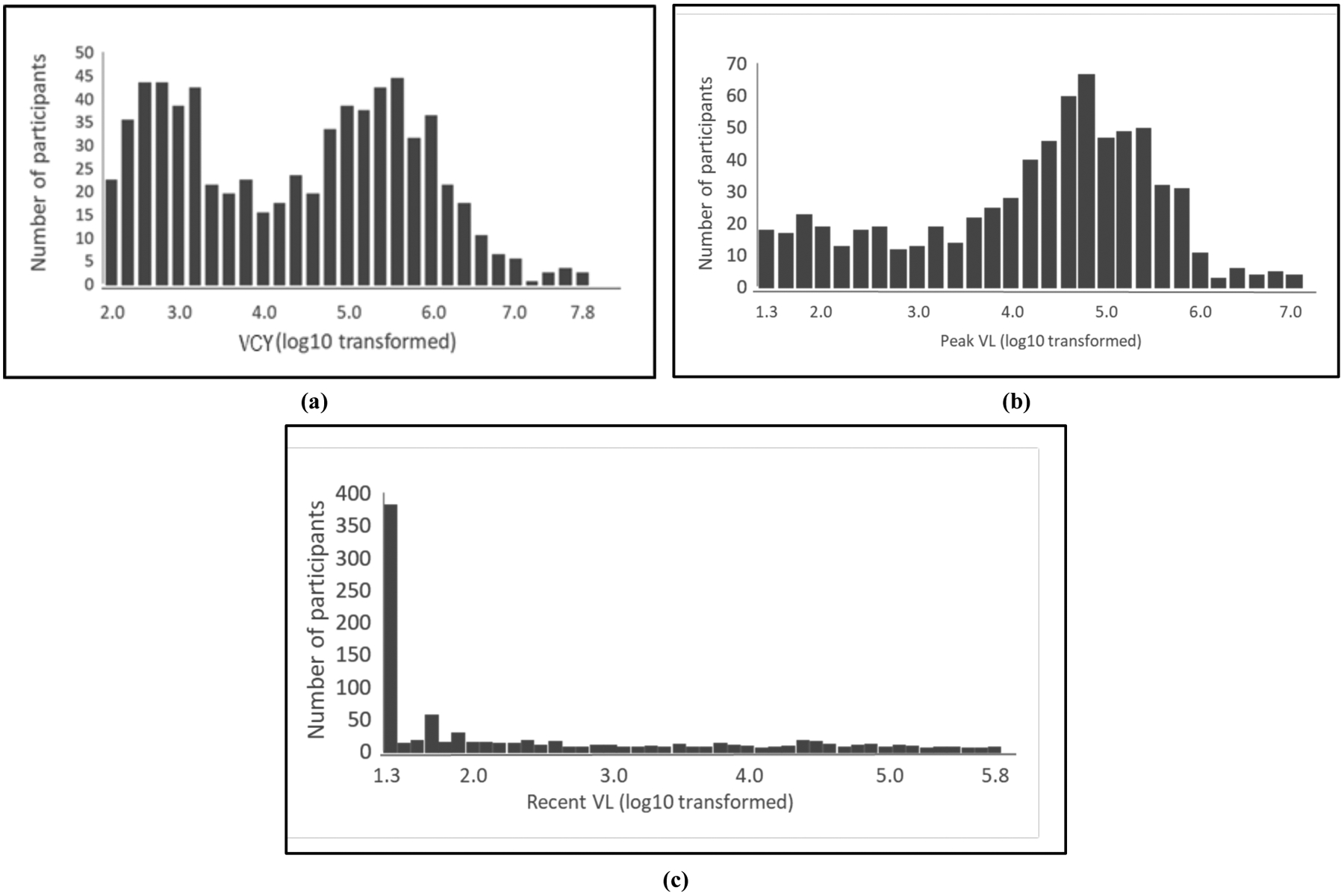

The log10 transformed VCY had a bimodal distribution with two peaks at 2.5–3.0 and 4.8–6.0, respectively. The distribution of pVL (log10 transformed) was relatively stable except for an increase between 4.5 – 5.5. The distribution of rVL (log10 transformed) was asymmetric and skewed distributed with the majority falling at 1.3 or less (Fig. 2). The rank correlation matrix for the various measures of VL is provided in Table 2. In summary, these measures of VL were positively correlated with each other with different extent.

Fig. (2).

Distribution of viremia copy-years (a), peak viral load (b), the most recent viral load (c).

Table 2.

Spearman’s rank correlation matrix for variables measures of viral load.

Note:

p<0.01; pVL: Peak Viral Load; rVL: the most Recent Viral Load; uVL: undetectable viral load; VCY: Viremia Copy-years;

3.3. Association between VCY and Hypertension

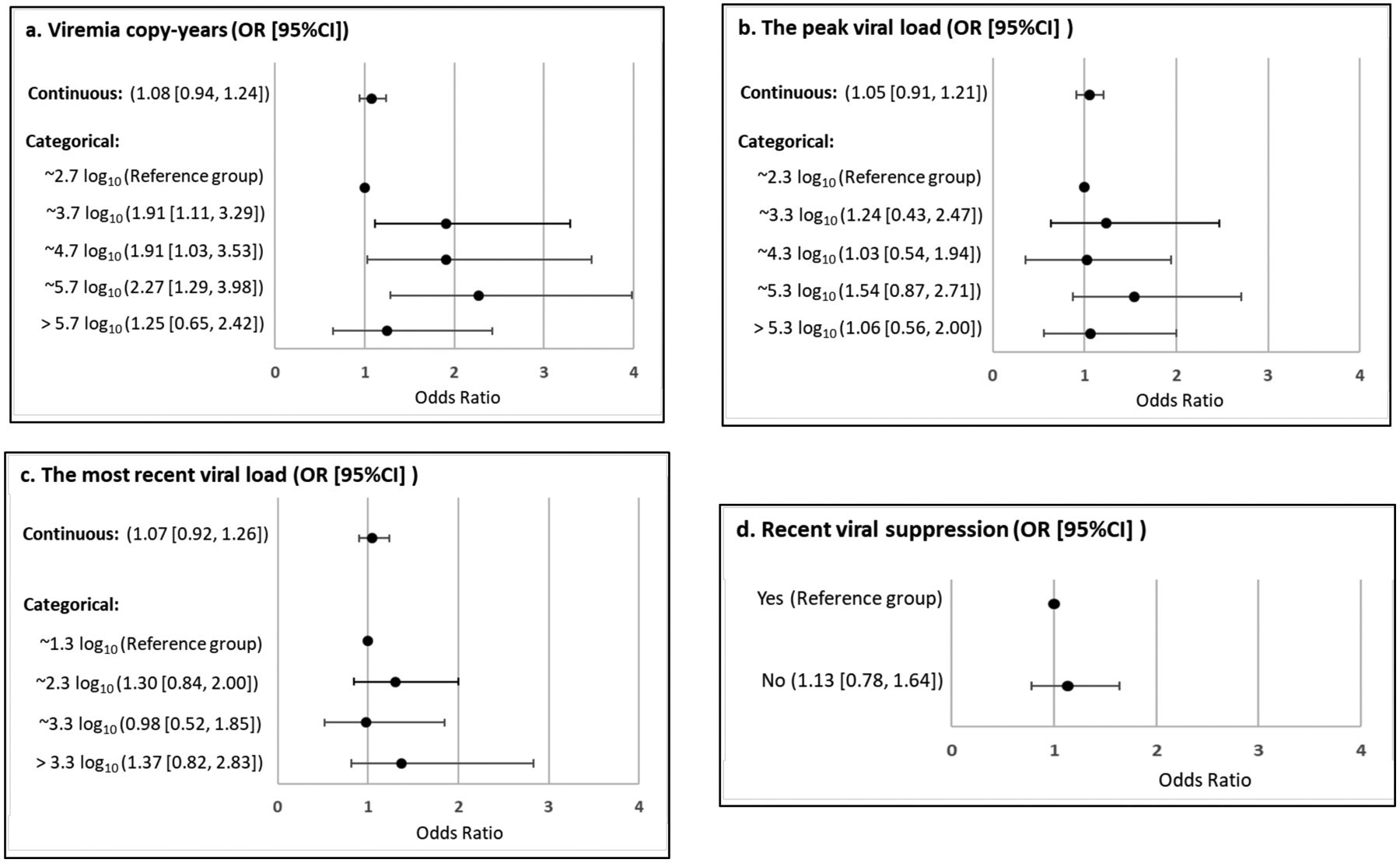

The associations with hypertension from separate logistic regressions for VCY, pVL, rVL, and uVL are given in Fig. (3) and Table 3. Of these four viral-load measures, VCY was significantly associated with hypertension (Fig. 3a and Table 3). Compared with the participant with VCP<2.7 log10 copy × years/mL, the odds ratio (OR) and the [95% CI] for participants with VCP of 2.7 – 3.7, 3.8 – 4.7, 4.8 – 5.7, and >5.7 log10 copy × years/mL were 1.91 [1.11, 3.29], 1.91 [1.03, 3.53], 2.27 [95%CI=1.29, 3.99], and 1.25 [95%CI=0.65, 2.42], respectively, after adjusting for demographic (age, sex, race/ethnicity) and other key factors (BMI, diabetes, CD4+ T cell count, and years of HIV diagnosis). Sensitivity analysis showed similar results for hypertensive patients with and without treatment in comparison to normotensive people (Appendix Table 1). When VCY was used as a continuous variable, the association with hypertension was not statistically significant (OR [95% CI] = 1.08 [0.94, 1.24]) (Fig. 3a).

Fig. (3).

Results of separate multivariable logistic regression models for (a) viremia copy-years, (b) peak viral load, (c) the most recent viral load, and (d) undetectable viral load.

Table 3.

Results of one multivariable logistic regression model including viremia copy-years, peak viral load, the most recent viral load, and undetectable viral load.

| Variables | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||

| Viremia copy-years | |||

| ~ 2.7 log10 (n=120) | 1.00 | - | - |

| ~ 3.7 log10 (n=151) | 1.93 | 1.09 | 3.44 |

| ~ 4.7 log10 (n=98) | 2.06 | 1.01 | 4.23 |

| ~ 5.7 log10 (n=204) | 2.14 | 1.05 | 4.36 |

| > 5.7 log10 (n=113) | 1.18 | 0.50 | 2.80 |

| Peak VL | |||

| ~2.3 (n=85) | 1.00 | - | - |

| ~3.3 (n=76) | 1.00 | 0.49 | 2.07 |

| ~4.3 (n=124) | 0.73 | 0.35 | 1.53 |

| ~5.3 (n=264) | 1.04 | 0.51 | 2.11 |

| >5.3 (n=137) | 0.93 | 0.41 | 2.11 |

| Recent VL | |||

| ~1.3 (n=369) | 1.00 | - | - |

| ~2.3 (n=153) | 1.29 | 0.74 | 2.25 |

| ~3.3 (n=55) | 0.92 | 0.34 | 2.47 |

| >3.3 (n=109) | 1.34 | 0.54 | 3.35 |

| Undetectable viral load | |||

| Yes | 1.00 | - | - |

| No | 0.94 | 0.45 | 1.96 |

No significant relationship was observed between the other three viral load measures and hypertension, including the peak viral load, the most recent viral load and whether the virus was detected or not (Fig. 3b–3d and Table 3).

All models were adjusted for age, sex, race (Hispanics, non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic-blacks, and others) BMI (kg/m2), diabetes, CD4+ T cell count (≥500 vs. <500 cells/mm3), and years of HIV diagnosis (>11 vs. ≤11years).

The model was adjusted for age, sex, race (Hispanics, non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic-blacks, and others) BMI (kg/m2), diabetes, CD4+ T cell count (≥500 vs. <500 cells/mm3), and years of HIV diagnosis (>11 vs. ≤11years).

4. DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study that assessed the relationship between cumulative exposure to HIV viremia and hypertension among PLWH using VCY, a well-established and widely accepted measure in research. With this measure, a patient’s cumulative HIV exposure was measured using VL data collected from routine HIV clinical blood draws for care. Although various VL measures are positively correlated with each other, their function to predict hypertension risk differed.

In our study, only VCY was significantly associated with hypertension, and this relationship was independent of pVL, rVL, and uVL. This association would not be detected if any of the three single time-point VL measures were used. Our findings support that VCY can provide more useful information beyond single time-point measures in investigating HIV infection-hypertension relationship. The findings of this study demonstrate the significance of continuous suppression of HIV VL in the prevention of hypertension for those living with a diagnosis of HIV.

A number of recent observations have examined the prognostic values of VCY measures. Some demonstrated improved prognostic performance of VCY over that of single time-point VL, and showed VCY as an independent predictor for AIDS mortality and morbidity [54, 60–62]. Some showed that the prognostic effect of VCY was dependent on single time-point VL measures and showing a stronger predictive effect of mortality of the single time-point VL measures than the accumulative VCY [59, 63]. We found two studies in which VCY was used to predict non-AIDS related clinic events. Results from these studies showed significant relationships between VCY and age-related declines in grip strength and acute myocardial infarction [60, 61]. Findings from our study add new data demonstrating the advantages of using VCY over other measures to examine the relationship between HIV infection and the risk of hypertension among PLWH.

Findings of our study suggest it is not the HIV exposure at a point in time but the cumulative exposure over time to elevate the risk of hypertension. The inconsistent findings regarding the relationship between HIV VL and hypertension [64–66] could be due to the use of one single time-point measure of VL while large variations in VL are possible for individual patients. Therefore, researchers must consider the relevance to the outcome variable when selecting a predictor [59, 67]. When examining an acute outcome, one-time measure of VL prior to the occurrence of the outcome, such as the most recent VL may be the most appropriate. However, hypertension is a chronic condition and it involves a long process from systematic inflammation, immune system activation, to arterial sclerosis, which occurs over a long period of time [59]. Therefore, VCY provides the most appropriate measure of exposure to HIV infection, compared to the other single time-point measures.

There is not yet a consensus on the routine use of VCY in HIV care practice, our findings serve as proof of the concept that such measures should be used to improve clinicians’ ability to identify patients who are at increased risk of hypertension. It implies that maintaining a low level of VL may lower the risk of hypertension among PLWH. Studies have shown a persistently elevated risk of hypertension among PLWH than HIV-controls despite viral suppression [39, 68, 69]. These conclusions, however, are based upon single time-point VL measure with the validity questionable.

It is worth noting that VCY>5.7 log10 copy × years/mL, the highest CVY group was not significant because the 95% CI included zero. This is probably due to the fact that participants with higher viral loads are also be more likely in the early stage of HIV infection, while hypertension often occur years later after infection. When VCY was analyzed as a continuous variable, the relationship with hypertension was not statistically significant. This result is reasonable because the VCY measure is bimodal rather than normally distributed as shown in Fig. (2) and the relationship between VCY and hypertension is not linear, based on results from the categorized VCY presented above. Additional studies are needed with discrete and chaotic models capable of considering this characteristic of the data, such as the cusp catastrophe modeling method [70–74]. Further, we selected a 5-year time frame to calculate VCY according to the existing literature regarding all-cause mortality [53]. How long of a meaningful window of a PLWH’s VL history should be included in VCY for optimal prognostic performance in predicting hypertension risk needs to be explored in more detail.

This study has limitations. Although we assessed cumulative HIV burden, the temporality of when the hypertension diagnosis occurred is unknown. Studies should be done using longitudinal data considering temporal sequences and time-dependent covariates. Studies in which VCY showed a better predictive of mortality were generally conducted among ART-initiating people, [54, 55, 63] whose hypertension risk is likely to be affected by the therapy [6, 7, 75, 76]. Because of data limitations, we were not able to separate the impact of cumulative HIV infection from ART initiation and ART regimens on the risk of hypertension. Data was unavailable to test the association of VCY with the severity of hypertension, such as elevated blood pressure, stage 1 hypertension, and stage 2 hypertension. In addition, although we have controlled established confounders available in our dataset, unmeasured confounders, such as physical activity, diet, and serum lipid measures were not taken into account. Finally, caution should be taken when generalizing our findings to other studies since participants of the study are persons living with an HIV diagnosis in Florida.

CONCLUSION

By assessing cumulative exposure to HIV viremia, the results of our study suggest that long-term unsuppressed HIV may be an independent risk factor of hypertension among PLWH. Keeping HIV VL continuously suppressed not only contributes to improving AIDS-related mortality and morbidity but also can be used as an effective strategy for hypertension prevention. Future research is necessary to explore how the correlation with VCY would be impacted by the severity of hypertension. In addition, future studies are needed to discover the impact of viral clade and HIV mutations on the relationship of cumulative HIV exposure and hypertension.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIAAA and the Southern HIV and Alcohol Research Consortium (SHARC). HIV surveillance data were provided by the HIV Surveillance section of the Florida Department of Health, Florida, USA.

FUNDING

This research was financially supported by NIAAA (Grants: U24 AA022002 and U24 AA022003).

APPENDIX

Table 1.

Association of viremia copy-years (cells × years/ml) and hypertension by the use of antihypertensive medication.

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||

| Hypertension treated vs. no hypertension | |||

| ~ 2.7 log10 | 1.00 | - | - |

| ~ 3.7 log10 | 2.06 | 1.22 | 4.39 |

| ~ 4.7 log10 | 2.11 | 1.12 | 4.63 |

| ~ 5.7 log10 | 2.91 | 1.68 | 6.64 |

| > 5.7 log10 | 1.54 | 0.85 | 4.21 |

| Hypertension untreated vs. no hypertension | |||

| ~ 2.7 log10 | 1.00 | - | - |

| ~ 3.7 log10 | 1.81 | 1.02 | 2.96 |

| ~ 4.7 log10 | 1.68 | 0.74 | 3.26 |

| ~ 5.7 log10 | 2.02 | 1.03 | 3.06 |

| > 5.7 log10 | 0.77 | 0.80 | 3.77 |

CI: Confidence Interval; OR: Odds Ratio. Odds ratio was estimated using multinominal logistic regression, controlling for age, sex, race (Hispanics, non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic-blacks, and others) BMI (kg/m2), diabetes, CD4+ T cell count (≥500 vs. <500 cells/mm3), and years of HIV diagnosis (>11 vs. ≤11years).

Footnotes

STANDARD OF REPORTING

The study conforms to the STROBE guidelines.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The authors confirm that the data supporting the results and findings of this study are available within the article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- [1].Samji H, Cescon A, Hogg RS, et al. North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD) of IeDEA. Closing the gap: increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and Canada. PLoS One 2013; 8(12): e81355 10.1371/journal.pone.0081355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Palella FJ Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, et al. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med 1998; 338(13): 853–60. 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Armah KA, Chang CC, Baker JV, et al. Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS) Project Team. Prehypertension, hypertension, and the risk of acute myocardial infarction in HIV-infected and -uninfected veterans. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58(1): 121–9. 10.1093/cid/cit652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bloomfield GS, Hogan JW, Keter A, et al. Hypertension and obesity as cardiovascular risk factors among HIV seropositive patients in Western Kenya. PLoS One 2011; 6(7): e22288 10.1371/journal.pone.0022288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Buchacz K, Baker RK, Palella FJ Jr, et al. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. Disparities in prevalence of key chronic diseases by gender and race/ethnicity among antiretroviral-treated HIV-infected adults in the US. Antivir Ther (Lond) 2013; 18(1): 65–75. 10.3851/IMP2450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Xu Y, Chen X, Wang K. Global prevalence of hypertension among people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Soc Hypertens 2017; 11(8): 530–40. 10.1016/j.jash.2017.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].van Zoest RA, van den Born BH, Reiss P. Hypertension in people living with HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2017; 12(6): 513–22. 10.1097/COH.0000000000000406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ucciferri C, Falasca K, Vecchiet J. Hypertension in HIV: Management and Treatment. AIDS Rev 2017; 19(4): 198–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kendall CE, Wong J, Taljaard M, et al. A cross-sectional, population-based study measuring comorbidity among people living with HIV in Ontario. BMC Public Health 2014; 14: 161 10.1186/1471-2458-14-161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Myerson M, Poltavskiy E, Armstrong EJ, Kim S, Sharp V, Bang H. Prevalence, treatment, and control of dyslipidemia and hypertension in 4278 HIV outpatients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014; 66(4): 370–7. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].van Zoest RA, Wit FW, Kooij KW, et al. AGEhIV Cohort Study Group. Higher Prevalence of Hypertension in HIV-1-Infected Patients on Combination Antiretroviral Therapy Is Associated With Changes in Body Composition and Prior Stavudine Exposure. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63(2): 205–13. 10.1093/cid/ciw285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nüesch R, Wang Q, Elzi L, et al. Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Risk of cardiovascular events and blood pressure control in hypertensive HIV-infected patients: Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013; 62(4): 396–404. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182847cd0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Clin Endo-crinol Metab 2007; 92(7): 2506–12. 10.1210/jc.2006-2190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Peck RN, Shedafa R, Kalluvya S, et al. Hypertension, kidney disease, HIV and antiretroviral therapy among Tanzanian adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med 2014; 12: 125 10.1186/s12916-014-0125-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Míguez-Burbano MJ, Quiros C, Lewis JE, et al. Gender differences in the association of hazardous alcohol use with hypertension in an urban cohort of people living with HIV in South Florida. PLoS One 2014; 9(12): e113122 10.1371/journal.pone.0113122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Manner IW, Baekken M, Oektedalen O, Os I. Hypertension and antihypertensive treatment in HIV-infected individuals. A longitudinal cohort study. Blood Press 2012; 21(5): 311–9. 10.3109/08037051.2012.680742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Krauskopf K, Van Natta ML, Danis RP, et al. Studies of the Ocular Complications of AIDS Research Group. Correlates of hypertension in patients with AIDS in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2013; 12(5): 325–33. 10.1177/2325957413491432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].De Socio GV, Ricci E, Maggi P, et al. CISAI study group. Time trend in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in a contemporary cohort of HIV-infected patients: the HIV and Hypertension Study. J Hypertens 2017; 35(2): 409–16. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hasse B, Tarr PE, Marques-Vidal P, et al. CoLaus Cohort, FIRE and the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Strong Impact of Smoking on Multimorbidity and Cardiovascular Risk Among Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Individuals in Comparison With the General Population. Open Forum Infect Dis 2015; 2(3): ofv108 10.1093/ofid/ofv108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rodríguez-Arbolí E, Mwamelo K, Kalinjuma AV, et al. KIU-LARCO Study Group. Incidence and risk factors for hypertension among HIV patients in rural Tanzania - A prospective cohort study. PLoS One 2017; 12(3): e0172089 10.1371/journal.pone.0172089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Factor SH, Lo Y, Schoenbaum E, Klein RS. Incident hypertension in older women and men with or at risk for HIV infection. HIV Med 2013; 14(6): 337–46. 10.1111/hiv.12010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Okello S, Kanyesigye M, Muyindike WR, et al. Incidence and predictors of hypertension in adults with HIV-initiating antiretroviral therapy in south-western Uganda. J Hypertens 2015; 33(10): 2039–45. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wong C, Gange SJ, Buchacz K, et al. North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD). First Occurrence of Diabetes, Chronic Kidney Disease, and Hypertension Among North American HIV-Infected Adults, 2000–2013. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64(4): 459–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mellors JW, Margolick JB, Phair JP, et al. Prognostic value of HIV-1 RNA, CD4 cell count, and CD4 Cell count slope for progression to AIDS and death in untreated HIV-1 infection. JAMA 2007; 297(21): 2349–50. 10.1001/jama.297.21.2349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Olsen CH, Gatell J, Ledergerber B, et al. EuroSIDA Study Group. Risk of AIDS and death at given HIV-RNA and CD4 cell count, in relation to specific antiretroviral drugs in the regimen. AIDS 2005; 19(3): 319–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Livelli A, Vaida F, Ellis RJ, et al. CHARTER Group. Correlates of HIV RNA concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid during antiretroviral therapy: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet HIV 2019; 6(7): e456–62. 10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30143-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chow FC, Bacchetti P, Kim AS, Price RW, Hsue PY. Effect of CD4+ cell count and viral suppression on risk of ischemic stroke in HIV infection. AIDS 2014; 28(17): 2573–7. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Rosenson RS, Kaul R. Cardiovascular Outcomes in Persons With HIV and Heart Failure: Medication Class or Suboptimal Viral Suppression? J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 72(5): 531–3. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.05.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kuller LH, Tracy R, Belloso W, et al. INSIGHT SMART Study Group. Inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers and mortality in patients with HIV infection. PLoS Med 2008; 5(10): e203 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tebas P, Henry WK, Matining R, et al. Metabolic and immune activation effects of treatment interruption in chronic HIV-1 infection: implications for cardiovascular risk. PLoS One 2008; 3(4): e2021 10.1371/journal.pone.0002021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hunt PW, Martin JN, Sinclair E, et al. T cell activation is associated with lower CD4+ T cell gains in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with sustained viral suppression during antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 2003; 187(10): 1534–43. 10.1086/374786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Manner IW, Trøseid M, Oektedalen O, Baekken M, Os I. Low nadir CD4 cell count predicts sustained hypertension in HIV-infected individuals. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2013; 15(2): 101–6. 10.1111/jch.12029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Crane HM, Van Rompaey SE, Kitahata MM. Antiretroviral medications associated with elevated blood pressure among patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2006; 20(7): 1019–26. 10.1097/01.aids.0000222074.45372.00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Xu Y, Chen X, Zhou Z, Morano J, Cook RL. The interaction between detectable plasma viral load and increased body mass index on hypertension among persons living with HIV. AIDS Care 2019; 1–6. 10.1080/09540121.2019.1668521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Remick J, Georgiopoulou V, Marti C, et al. Heart failure in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and future research. Circulation 2014; 129(17): 1781–9. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Gazzaruso C, Bruno R, Garzaniti A, et al. Hypertension among HIV patients: prevalence and relationships to insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. J Hypertens 2003; 21(7): 1377–82. 10.1097/00004872-200307000-00028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Calò LA, Caielli P, Maiolino G, Rossi G. Arterial hypertension and cardiovascular risk in HIV-infected patients. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2013; 14(8): 553–8. 10.2459/JCM.0b013e3283621f01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Bourgi K, Wanjalla C, Koethe JR. Inflammation and Metabolic Complications in HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2018; 15(5): 371–81. 10.1007/s11904-018-0411-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Castley A, Williams L, James I, Guelfi G, Berry C, Nolan D. Plasma CXCL10, sCD163 and sCD14 Levels Have Distinct Associations with Antiretroviral Treatment and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors. PLoS One 2016; 11(6): e0158169 10.1371/journal.pone.0158169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Pirro M, Mannarino MR, Francisci D, et al. Urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio is associated with endothelial dysfunction in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 28741 10.1038/srep28741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Slim J, Saling CF. A Review of Management of Inflammation in the HIV Population. BioMed Res Int 2016; 2016: 3420638 10.1155/2016/3420638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Maia-Leite LH, Catez E, Boyd A, et al. Aortic stiffness aging is influenced by past profound immunodeficiency in HIV-infected individuals: results from the EVAS-HIV (EValuation of Aortic Stiffness in HIV-infected individuals). J Hypertens 2016; 34(7): 1338–46. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Stein JH, Hsue PY. Inflammation, immune activation, and CVD risk in individuals with HIV infection. JAMA 2012; 308(4): 405–6. 10.1001/jama.2012.8488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Fahme SA, Bloomfield GS, Peck R. Hypertension in HIV-Infected Adults: Novel Pathophysiologic Mechanisms. Hypertension 2018; 72(1): 44–55. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.10893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Glyn MC, Van Rooyen JM, Schutte R, et al. A comparison of the association between glomerular filtration and L-arginine status in HIV-infected and uninfected African men: the SAfrEIC study. J Hum Hypertens 2013; 27(9): 557–63. 10.1038/jhh.2013.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ding Y, Lin H, Liu X, et al. Hypertension in HIV-Infected Adults Compared with Similar but Uninfected Adults in China: Body Mass Index-Dependent Effects of Nadir CD4 Count. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2017; 33(11): 1117–25. 10.1089/aid.2017.0008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Morimoto HK, Simão AN, de Almeida ER, et al. Role of metabolic syndrome and antiretroviral therapy in adiponectin levels and oxidative stress in HIV-1 infected patients. Nutrition 2014; 30(11–12): 1324–30. 10.1016/j.nut.2014.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Hemkens LG, Bucher HC. HIV infection and cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J 2014; 35(21): 1373–81. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Okeke NL, Davy T, Eron JJ, Napravnik S. Hypertension Among HIV-infected Patients in Clinical Care, 1996–2013. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63(2): 242–8. 10.1093/cid/ciw223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Antonello VS, Antonello IC, Grossmann TK, Tovo CV, Pupo BB, Winckler LdeQ. Hypertension--an emerging cardiovascular risk factor in HIV infection. J Am Soc Hypertens 2015; 9(5): 403–7. 10.1016/j.jash.2015.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Cheru LT, Saylor CF, Fitch KV, et al. Low vitamin D is associated with coronary atherosclerosis in women with HIV. Antivir Ther (Lond) 2019; [Epub ahead of print]. 10.3851/IMP3336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Quiros-Roldan E, Raffetti E, Castelli F, et al. Low-level viraemia, measured as viraemia copy-years, as a prognostic factor for medium-long-term all-cause mortality: a MASTER cohort study. J An-timicrob Chemother 2016; 71(12): 3519–27. 10.1093/jac/dkw307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Wang R, Haberlen SA, Palella FJ Jr, et al. Viremia copy-years and mortality among combination antiretroviral therapy-initiating HIV-positive individuals: how much viral load history is enough? AIDS 2018; 32(17): 2547–56. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Mugavero MJ, Napravnik S, Cole SR, et al. Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems (CNICS) Cohort Study. Viremia copy-years predicts mortality among treatment-naive HIV-infected patients initiating antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53(9): 927–35. 10.1093/cid/cir526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Wright ST, Hoy J, Mulhall B, et al. Determinants of viremia copy-years in people with HIV/AIDS after initiation of antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014; 66(1): 55–64. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Sharpe JD, et al. Interest in using mobile technology to help self-manage alcohol use among persons living with the human immunodeficiency virus: A Florida Cohort cross-sectional study. Subst Abus 2017; 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Cook RL, Zhou Z, Kelso-Chichetto NE, et al. Alcohol consumption patterns and HIV viral suppression among persons receiving HIV care in Florida: an observational study. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2017; 12(1): 22 10.1186/s13722-017-0090-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Olson AD, Walker AS, Suthar AB, et al. CASCADE Collaboration in EuroCoord. Limiting Cumulative HIV Viremia Copy-Years by Early Treatment Reduces Risk of AIDS and Death. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016; 73(1): 100–8. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Cole SR, Napravnik S, Mugavero MJ, Lau B, Eron JJ Jr, Saag MS. Copy-years viremia as a measure of cumulative human immunodeficiency virus viral burden. Am J Epidemiol 2010; 171(2): 198–205. 10.1093/aje/kwp347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Salinas JL, Rentsch C, Marconi VC, et al. Baseline, Time-Updated, and Cumulative HIV Care Metrics for Predicting Acute Myocardial Infarction and All-Cause Mortality. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63(11): 1423–30. 10.1093/cid/ciw564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Schrack JA, Jacobson LP, Althoff KN, et al. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Effect of HIV-infection and cumulative viral load on age-related decline in grip strength. AIDS 2016; 30(17): 2645–52. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Kowalkowski MA, Day RS, Du XL, Chan W, Chiao EY. Cumulative HIV viremia and non-AIDS-defining malignancies among a sample of HIV-infected male veterans. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014; 67(2): 204–11. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Chirouze C, Journot V, Le Moing V, et al. ANRS CO 08 Aproco-Copilote Study Group. Viremia copy-years as a predictive marker of all-cause mortality in HIV-1-infected patients initiating a protease inhibitor-containing antiretroviral treatment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 68(2): 204–8. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Jericó C, Knobel H, Montero M, et al. Hypertension in HIV-infected patients: prevalence and related factors. Am J Hypertens 2005; 18(11): 1396–401. 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Medina-Torne S, Ganesan A, Barahona I, Crum-Cianflone NF. Hypertension is common among HIV-infected persons, but not associated with HAART. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2012; 11(1): 20–5. 10.1177/1545109711418361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Arruda Junior ER, Lacerda HR, Moura LC, et al. Risk factors related to hypertension among patients in a cohort living with HIV/AIDS. Braz J Infect Dis 2010; 14(3): 281–7. 10.1016/S1413-8670(10)70057-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Rothman KJ. Induction and latent periods. Am J Epidemiol 1981; 114(2): 253–9. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Longenecker CT, Sullivan C, Baker JV. Immune activation and cardiovascular disease in chronic HIV infection. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2016; 11(2): 216–25. 10.1097/COH.0000000000000227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Nordell AD, McKenna M, Borges ÁH, Duprez D, Neuhaus J, Neaton JD. INSIGHT SMART, ESPRIT Study Groups; SILCAAT Scientific Committee. Severity of cardiovascular disease outcomes among patients with HIV is related to markers of inflammation and coagulation. J Am Heart Assoc 2014; 3(3): e000844 10.1161/JAHA.114.000844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Chen X, Stanton B, Chen D, Li X. Intention to use condom, cusp modeling, and evaluation of an HIV prevention intervention trial. Nonlinear Dyn Psychol Life Sci 2013; 17(3): 385–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Xu Y, Chen X. Protection motivation theory and cigarette smoking among vocational high school students in China: a cusp catastrophe modeling analysis. Glob Health Res Policy 2016; 1: 3 10.1186/s41256-016-0004-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Yu B, Chen X, Stanton B, Chen DD, Xu Y, Wang Y. Quantum changes in self-efficacy and condom-use intention among youth: A chained cusp catastrophe model. J Adolesc 2018; 68: 187–97. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Wang W, Chen X, Li S, Yan H, Yu B, Xu Y. Cusp Catastrophe Modeling of Suicide Behaviors among People Living with HIV in China. Nonlinear Dyn Psychol Life Sci 2019; 23(4): 491–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Chen X, Wang Y, Chen DG. Nonlinear Dynamics of Binge Drinking among U.S. High School Students in Grade 12: Cusp Catastrophe Modeling of National Survey Data. Nonlinear Dyn Psychol Life Sci 2019; 23(4): 465–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Dimala CA, Atashili J, Mbuagbaw JC, Wilfred A, Monekosso GL. A Comparison of the Diabetes Risk Score in HIV/AIDS Patients on Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) and HAART-Naïve Patients at the Limbe Regional Hospital, Cameroon. PLoS One 2016; 11(5): e0155560 10.1371/journal.pone.0155560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Bernardino de la Serna JI, Zamora FX, Montes ML, García-Puig J, Arribas JR. Hypertension, HIV infection, and highly active antiretroviral therapy. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2010; 28(1): 32–7. 10.1016/j.eimc.2008.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]