Abstract

Objective:

To determine in true vocal fold (TVF) atrophy patients if symptoms of throat clearing and mucus sensation, attributed to laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR), are due to glottic insufficiency. Is the TVF atrophy population being prescribed proton pump inhibitors unnecessarily?

Methods:

A retrospective review of patients with TVF atrophy but no other underlying laryngeal pathology seen at a tertiary voice center from July 2009 to May 2012 was conducted. Patient demographics, symptoms, LPR diagnosis, interventions, and pre-intervention and post-intervention Voice Handicap Index–10 (VHI) and Reflux Symptom Index (RSI) scores were recorded.

Results:

Twenty-six patients met inclusion criteria, and 85% were treated for LPR. Throat clearing and mucus sensation (85%), dysphonia (54%), and globus sensation (46%) were recorded. Interventions included LPR medical management (65%), vocal fold augmentation (23%), and voice therapy (12%). Reflux Symptom Index scores improved in all groups. Voice Handicap Index–10 and RSI scores normalized in patients treated with augmentation. Globus was never present in patients who received augmentation.

Conclusion:

Throat clearing and mucus sensation may be due to underlying glottic insufficiency and changes of the aging larynx rather than LPR. High VHI and RSI scores normalized with TVF augmentation. Further work is needed to evaluate symptom presentation and risk versus benefit of treatment options, especially if it avoids unnecessary proton pump inhibitor trials.

Keywords: dysphonia, glottic insufficiency, laryngopharyngeal reflux, presbylarynx, proton pump inhibitors, vocal fold atrophy

Introduction

The ability of otolaryngologists to understand and manage the symptoms attributed to the inappropriate escape of subtle or gross air during normal phonation, otherwise known as glottic insufficiency (GI), remains a work in progress. True vocal fold (TVF) atrophy (hereinafter referred to as atrophy) is 1 cause of GI and a common finding among the ever growing, aging population who present with voice or throat complaints. The incidence of voice problems has been reported at approximately 29% in individuals older than 65 years. This accounts for greater than 10 million people in the United States per the US Census Bureau.1 The most common diagnoses in the setting of an older patient with a voice disorder include atrophy, neurologic disease, and TVF immobility or paralysis.2 These voice problems cause symptoms including throat clearing, cough, globus, dysphonia, decreased vocal volume, and vocal fatigue.3,4 The aging voice is naturally affected by anatomic, hormonal, circulatory, skeletal, pharmaceutical, and neuromuscular changes.5 These changes result in expected age-related acoustic variability that can be difficult to distinguish from a true voice disorder, and it is often the individual patient, the family, or the primary care provider who decides when laryngeal evaluation is warranted.

There is great overlap in the symptom presentation of GI and laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR), and both diagnoses are commonly given when patients present with the nonspecific symptoms of dysphonia, throat clearing, and mucus sensation.6 Among all ages, LPR is diagnosed as frequently as 35% to 78% of the time when muscle tension dysphonia (MTD) is present. However, up to 59% of the time, other pathology is coexistent that contributes to the symptoms and may cause GI, but the difference between primary and secondary MTD (with an underlying reason for the hyperfunction) has not been differentiated.7,8 In a study by Cohen et al,7 74% of dysphonic patients who had electively stopped prescribed proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) improved instead with voice therapy. This postulates that voice dysfunction previously assumed to be due to acid LPR may have been due to a previously missed underlying TVF pathology causing GI and secondary MTD.

Although some symptoms are universal to any cause of GI, there are likely distinguishable symptoms and therefore treatments that are superior based on the underlying diagnosis. Atrophy and paresis are 2 causes of GI and secondary MTD that likely deserve more differentiation. They have different pathophysiologies but can both lead to hyperfunctional behaviors.9 Distinguishing between atrophy and paresis from a treatment standpoint may help clinicians understand why procedures that focus solely on improving glottic closure may relieve certain symptoms and not others. One reason for potential differences in treatment outcomes is that paresis can often be part of a presumed post-viral vagal neuropathy (PVVN) with a higher incidence of true LPR and esophageal dysfunction, whereas atrophy is typically associated with tissue change to the lamina propria, mucus glands, and muscle of the larynx.8,10

With further study and focus on thorough diagnosis, interventions may be better tailored to the true voice disorder and may avoid unnecessary, potentially harmful medication use and expedite symptom resolution.11 In this study, patients with atrophy and resultant GI are evaluated to determine if treatment outcomes and presenting symptom patterns can be used to assist in differentiating future patients with isolated GI from those with concomitant LPR. We hypothesize that some atrophy patients with symptoms of throat clearing and mucus sensation are being started on PPIs unnecessarily for presumed LPR and correcting GI might instead be more effective for their symptoms.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained. A retrospective review of a prospectively maintained database was performed to identify patients with a diagnosis of atrophy. All patients were seen by the same physician in a tertiary academic medical center from 2009 to 2013. Atrophy patients’ charts were reviewed to document demographics including age, gender, laryngeal symptoms (throat clearing, mucus production, globus, and dysphonia), a clinical diagnosis of LPR, interventions, and pre- and post-intervention Voice Handicap Index–10 (VHI) and Reflux Symptom Index (RSI) scores.

The diagnosis of atrophy and GI is made the same way in each patient in the outpatient center using flexible larynxgovideostroboscopy (LVS) (KayPENTAX VNL-1070STK scope with Laryngeal Strobe Model 9200C; PENTAX Medical, Montvale, New Jersey, USA). The TVFs in an atrophy diagnosis are required to be symmetric in appearance with normal gross abduction and adduction and no membranous lesions present in the setting of bilateral atrophic changes (membranous volume loss, prominent vocal processes, etc). In addition, atrophy patients typically demonstrate an elliptical, anterior gap or short-complete phase closure glottic cycle pattern with 40% or less of frames in the closed phase at comfortable pitch and loudness (frame-by-frame analysis), often in the setting of supraglottic hyperfunction.12 Rarely, and usually in men, a complete-long and often exaggerated closed phase pattern is seen, but this must exist in the setting of obvious vocal fold soft tissue volume loss with the accompanying hyperfunction to be designated as TVF atrophy.12 The LVS videos were reviewed and these criteria confirmed by the senior author before final participant inclusion. Laryngopharyngeal reflux is diagnosed clinically by patient-reported laryngeal symptoms, RSI score greater than 13, and endoscopic changes such as edema and erythema of interarytenoid and post-cricoid areas and pseudosulcus vocalis.13 The diagnosis is never made on laryngeal appearance alone.

Exclusion criteria removed patients with other laryngeal pathologies such as lesions, scars, vocal fold motion abnormalities, and other neurologic disorders that could explain their symptoms and confound the results. One exception was to not exclude potential participants with a vocal process granuloma (not altering the ability of the vocal processes to touch) in the setting of glottic insufficiency with hyperfunction in the setting of LPR. Vocal process granulomas, LPR, and GI are intricately related and, in the senior author’s opinion, the granuloma is a result of the hyperfunction in the setting of LPR and amenable to resolution by treating LPR and/or treating the GI.11 Additional exclusion criteria included loss to follow-up within the 3-month period after initialization of treatment, missing data, and an initial RSI score less than or equal to 13.

Participants were divided into 3 groups based on the intervention they had received: LPR treatment only, vocal fold augmentation, and voice therapy. Laryngopharyngeal reflux treatment was either 40 mg of omeprazole (or equivalent) daily plus 300 mg of ranitidine at bedtime or 40 mg of omeprazole (or equivalent) twice daily for 3 months in those whose symptoms did not respond to the lower dose. Augmentation was performed in a trial fashion using carboxymethylcellulose (RADIESSE Voice Gel; Merz Aesthetics Inc, San Mateo, California, USA). In those patients who respond to their trial injection favorably, autologous fat or medialization laryngoplasty is typically offered. In the present study cohort, only autologous fat was chosen by patients who received permanent augmentation. Voice Handicap Index–10 and RSI scores were recorded as “worst pre-” and “best post-” intervention scores (which were after their trial or fat augmentation) and a Delta VHI score (the change in VHI with a larger positive score meaning more improvement) was reported for statistical analysis.

Mean VHI and RSI at baseline and Delta VHI were compared between groups. For normally distributed variables, the Student’s t test was used; for non-normally distributed variables, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used. To test the difference in the proportion of patients with improvement in RSI, the Fisher’s exact test was used. All analyses were performed using the SAS System for Windows, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA), and all reported P values were 2-sided. A P value of .05 was used for significance.

Results

A total of 26 patients from July 2009 to May 2012 were identified as having bilateral TVF atrophy. Fifty-four percent (14 of 26) of the participants were male. The mean age of all patients was 73 years (range, 55–92 years). Eighty-five percent (22 of 26) presented with both clinically suspected LPR and LVS evidence of atrophy, with the remaining 15% (4 of 26) having suspected atrophy with no LPR (hereinafter referred to as atrophy only) as revealed by history and examination. In these 4 patients who did not receive treatment for LPR initially, it should be noted that despite all having RSI scores higher than 13, when the entire patient picture was evaluated, there was not enough evidence from history or exam to begin PPI therapy. One participant, #19 (Table 1), had a vocal process granuloma as part of his clinical picture and was part of the LPR only group with a response to PPI therapy.

Table 1.

Description of Patient Characteristics, Grouped by Treatment, Including Sex, Age, Initial VHI, Delta VHI, Initial RSI, Final RSI, and Percentage Change in RSI.a

| Participant No. | Sex | Age, y | Initial VHI | Delta VHI | Initial RSI | Final RSI | % Change RSI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPR medical management | |||||||

| 1 | M | 81 | 0.0 | −5.0 | 22.0 | 5.0 | 77.3 |

| 2 | F | 73 | 17.0 | 9.0 | 14.0 | 8.0 | 42.9 |

| 3 | M | 74 | 1.0 | −2.0 | 36.0 | 10.0 | 72.2 |

| 4 | F | 87 | 18.0 | −6.0 | 20.0 | 17.0 | 15.0 |

| 5 | M | 61 | 14.0 | −2.0 | 20.0 | 6.0 | 70.0 |

| 6 | F | 85 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 22.0 | 5.0 | 77.3 |

| 7 | M | 55 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 19.0 | 11.0 | 42.1 |

| 8 | M | 68 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 23.0 | 3.0 | 87.0 |

| 9 | F | 62 | 8.0 | 2.0 | 15.0 | 6.0 | 60.0 |

| 10 | M | 79 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 24.0 | 10.0 | 58.3 |

| 11 | F | 58 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 35.0 | 27.0 | 22.9 |

| 12 | F | 64 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 35.0 | 18.0 | 48.6 |

| 13 | F | 91 | 9.0 | −3.0 | 36.0 | 8.0 | 77.8 |

| 14 | M | 84 | 2.0 | −2.0 | 13.0 | 2.0 | 84.6 |

| 15 | M | 65 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 13.0 | 35.0 |

| 16 | M | 73 | 6.0 | 3.0 | 22.0 | 20.0 | 9.1 |

| 17 | M | 83 | 16.0 | 4.0 | 29.0 | 6.0 | 79.3 |

| 7.3 | 0.6 | 23.8 | 10.3 | 56.4 | |||

| Voice therapy | |||||||

| 18 | M | 64 | 11.0 | 6.0 | 18.0 | 13.0 | 27.8 |

| 19 | M | 63 | 20.0 | 5.0 | 15.0 | 8.0 | 46.7 |

| 20b | F | 81 | 17.0 | 5.0 | 23.0 | 17.0 | 26.1 |

| 16.0 | 1.3 | 18.7 | 12.7 | 33.5 | |||

| Vocal fold augmentation | |||||||

| 21 | F | 75 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 26.0 | 3.0 | 88.5 |

| 22 | F | 67 | 25.0 | 21.0 | 40.0 | 13.0 | 67.5 |

| 23 | F | 82 | 14.0 | −4.0 | 23.0 | 7.0 | 69.6 |

| 24b | M | 60 | 21.0 | 9.0 | 16.0 | 12.0 | 25.0 |

| 25b | M | 60 | 23.0 | 21.0 | 14.0 | 7.0 | 50.0 |

| 26b | F | 92 | 26.0 | 12.0 | 18.0 | 7.0 | 61.1 |

| 20.8 | 12.5 | 22.8 | 8.2 | 60.3 | |||

Abbreviations: LPR, laryngopharyngeal reflux; RSI, Reflux Symptom Index; VHI, Voice Handicap Index–10.

Column averages for each subject group are shown in bold.

Designates participant as member of the “atrophy only” group who were never clinically suspected of LPR.

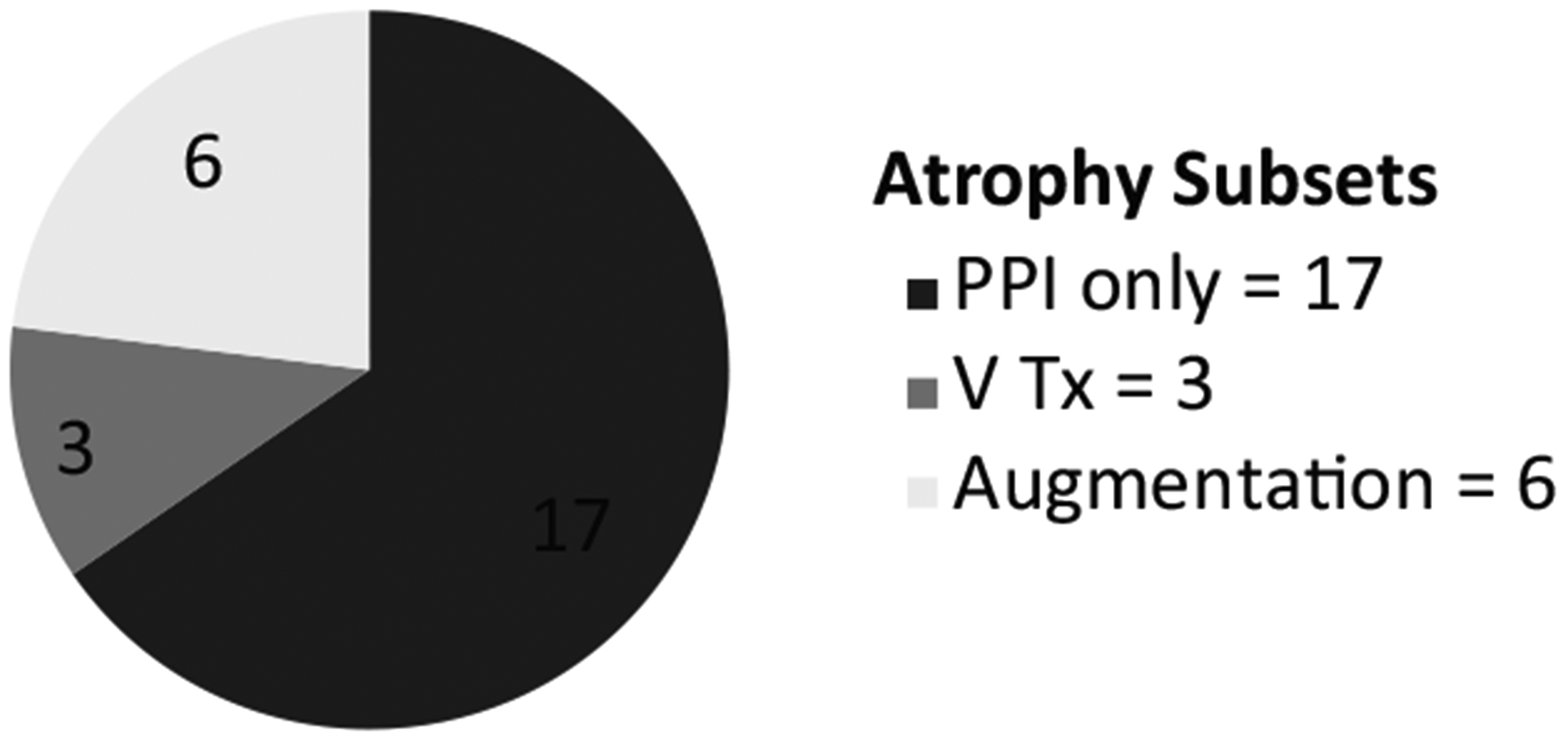

Sixty-five percent of participants were treated with medication only for LPR (17 of 26), 23% received vocal fold augmentation (6 of 26), and 12% underwent voice therapy (3 of 26) (Figure 1). The augmentation participants were either atrophy only or had not shown improvement on maximal PPI therapy as defined above. None of the voice therapy participants received a vocal fold augmentation, nor did any participant who received augmentation complete or improve his or her VHI with voice therapy if it was offered. Of the 4 participants given an atrophy only diagnosis on presentation (participants #20, #24, #25, and #26), 3 were part of the 6-patient group receiving vocal fold augmentation and the remaining participant was a member of the voice therapy group (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of atrophy patients treated with laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) medical therapy, voice therapy, and vocal fold augmentation.

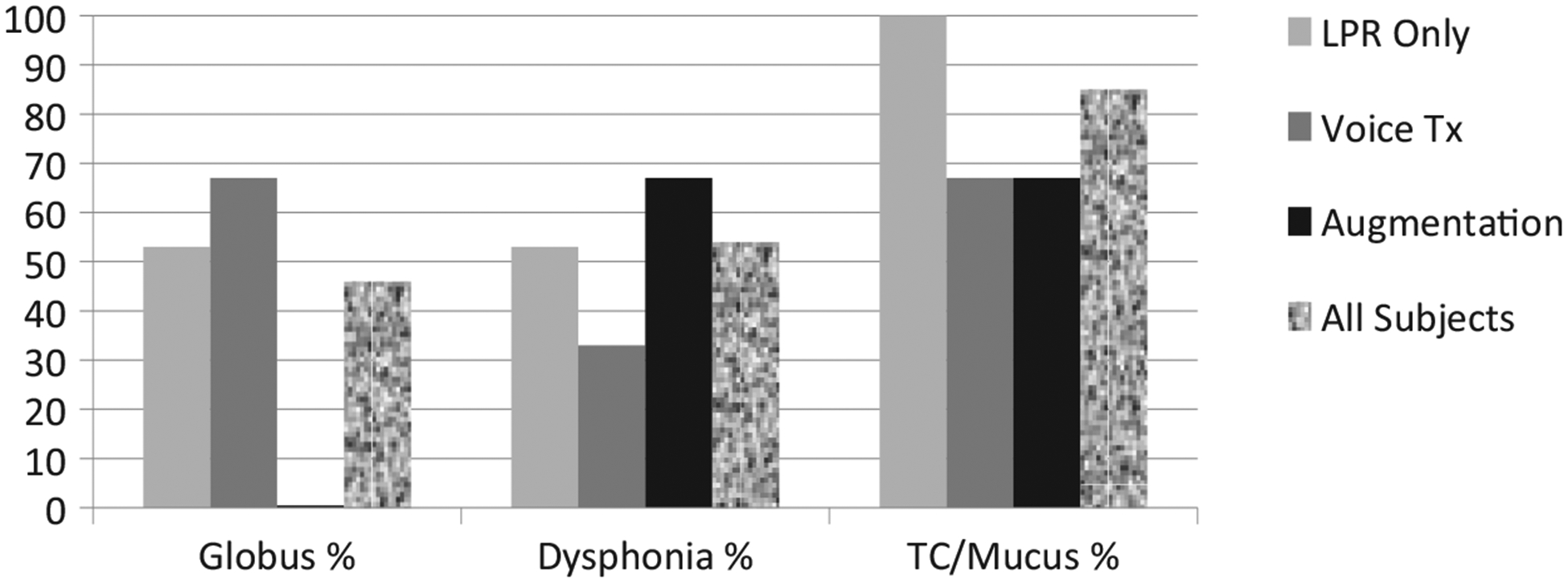

As shown in Figure throat clearing and mucus sensation was the most common complaint as reported by 85% (22 of 26) of all participants. Dysphonia was reported by 54% (14 of 26), and globus sensation was reported by 46% (12 of 26). Of the 17 patients treated for LPR alone, 53% presented with globus sensation, 53% with dysphonia, and 100% with throat clearing/mucus. Of the 3 patients receiving voice therapy, 67% presented with globus sensation, 33% with dysphonia, and 67% with throat clearing/mucus. Of the 6 patients who underwent vocal fold augmentation, none presented with globus sensation, 67% presented with dysphonia, and 67% with throat clearing/mucus.

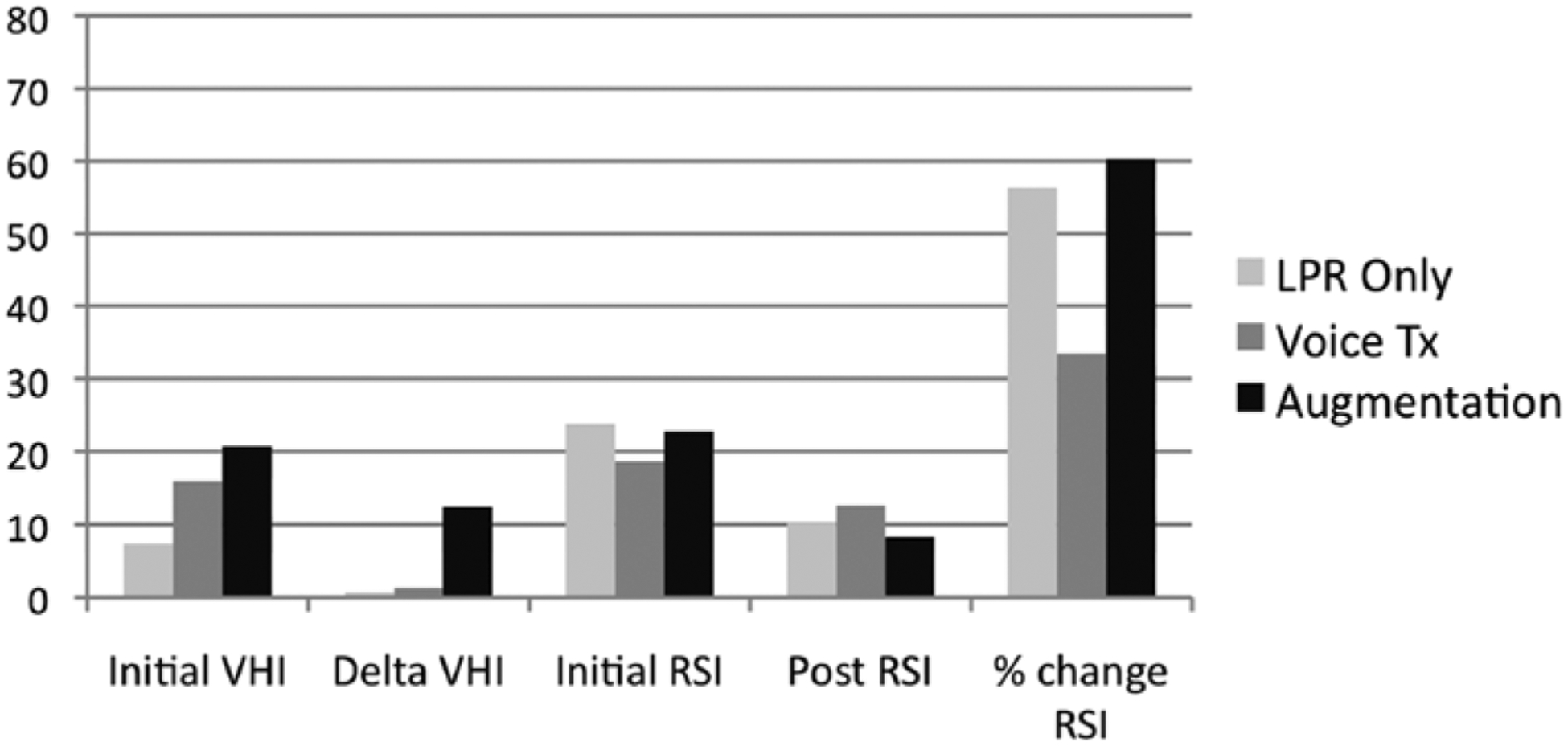

The average initial VHI and RSI scores in patients who received only LPR medical management were 7.3 and 23.8, respectively (Figure 3). After treatment, the Delta VHI was 0.6 and the RSI score improved to 10.3 in this group. Patients who received voice therapy alone had an average VHI score of 16 and average RSI score of 18.7 pre-treatment. The post-voice therapy Delta VHI was 1.3 and the RSI score decreased to 12.7. In the group of patients who received vocal fold augmentation, pre-treatment VHI and RSI scores were 20.8 and 22.8, respectively, with a Delta VHI of 12.5 and a decrease in RSI score to 8.2. The initial average VHI score was significantly higher in those patients who ultimately received TVF augmentation (P < .0004); however, the presenting RSI scores were not different between the augmentation group and the other participants (P = .95). The Delta VHI was significantly higher for the augmentation group compared to the PPI only and voice therapy groups (P = .03). Percentage change in RSI is also presented in Table 1 and Figure 3 for clinical interest.

Figure 3.

Voice Handicap Index–10 (VHI) and Reflux Symptom Index (RSI) scores in the setting of laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) treatment, voice therapy, and vocal fold augmentation.

Discussion

There is growing interest in voice-related problems in our aging population, and TVF atrophy has been found to be more prevalent in people older than 65 years.2 Throat clearing and mucus sensation are common complaints across TVF atrophy patients (85% in the current study) and this article affords its readers a hypothesis that these complaints should not be immediately attributed to LPR with PPIs prescribed in the setting of TVF atrophy. Globus, a common but nonspecific LPR complaint, was present in 46% of our participants, many who responded to empiric PPI therapy. It is interesting that globus was absent in our augmentation group. The augmentation group consisted of some patients who had failed PPI therapy and ultimately improved both their VHI and RSI scores only after augmentation. Of note, RSI scores normalized, on average, in all groups regardless of treatment. This supports the notion that finding the correct initial management strategy will cause relief of symptoms that are often attributable to LPR and are typically followed using the RSI.

Of the patients assessed in the current study, trends in treatment were apparent and suggest that initial interventions are appropriately driven by patient history as well as VHI and RSI scores. Voice therapy was offered in only 3 cases of atrophy because, like prior studies evaluating voice therapy, outcomes in this setting have shown that it had a lower likelihood of subjective voice improvement.1 Outcomes from the chosen treatments appear to appropriately relate back to the initial VHI and RSI scores: patients were more often successfully treated empirically for LPR when the presenting VHI score was low, whereas participants who presented with a high VHI score ultimately received voice therapy or augmentation. The augmentation group ultimately showed the largest Delta VHI despite 1 participant (#23) having a worse post-augmentation VHI score (this was likely due to the trial injection wearing off before the follow-up VHI was obtained). This begs the question of whether or not the presence of a voice complaint could trump LPR symptoms (even if present with a high RSI score) in directing the initial treatment in TVF atrophy patients away from PPIs. Because some patients had dramatic reductions in their RSI score only after augmentation, we purport that the symptoms of throat clearing and mucus sensation, potentially more arguably in the absence of globus sensation and in the setting of elevated VHI and RSI scores, may not need empiric PPI trials and the inherent risks that come from long- and short-term use of PPIs.14

Understanding the management of GI and its accompanying symptoms remains incomplete. It is unclear why TVF atrophy patients have throat clearing and mucus as a common complaint. Multiple factors affect the aging larynx and make it challenging to delineate normal change from pathology. Elderly patients are often on multiple medications with drying side effects.15 Previous studies describe senescent changes to mucus glands in the elderly.16 A study by Drs Koufman and Amin did not find objective reflux in all of their atrophy patients suspected of having this comorbidity.6 Although standard pH testing could have missed non-acid reflux disease in their cohort, this subset of patients may have had LPR-like symptoms due to GI rather than true LPR. Patients who do not respond to high dose BID PPIs in our institution are sent routinely for coordinated pH impedance and high resolution esophageal manometry testing. As an aside, 5 participants (participants #2, #4, #11, #16, and #18) in the current study who had clinically suspicious LPR and failed 40 mg BID omeprazole were sent for this testing and 4 completed it. All were from the LPR only group with either persistently high RSI scores or symptoms that warranted further reflux testing such as regurgitation. One was normal, 3 of 4 had abnormal pH impedance testing (non-acid reflux), 2 of these 3 had abnormal esophageal motility, and 1 was discovered to have Barrett’s esophagus requiring treatment before testing was completed. Overall, 3 of 4 participants who failed PPIs had good evidence of reflux that was not completely treated with acid suppression therapy.

Despite the data being collected prospectively, this is a retrospective review inherently with all associated bias. Prospective studies are needed to evaluate these trends, specifically exploring the success of augmentation as initial therapy in patients with TVF atrophy and the common complaints of throat clearing and mucus sensation when both presenting VHI and RSI scores are high. The decision to change treatment patterns, if these early data are correct, will depend not only on patient outcomes but also on risk and cost of augmentation when compared to PPI therapy and reflux testing.

Conclusion

Throat clearing and mucus sensation in the atrophy population may not be due to LPR but rather may be a reflection of underlying GI and other changes of the aging larynx. Participants presenting with high VHI and RSI scores normalized both scores when given TVF augmentation. Further work is needed to evaluate symptom presentation and risk versus benefit of treatment options in elderly dysphonic patients with GI, especially if it might avoid unnecessary PPI trials.

Figure 2.

Percentage of globus, dysphonia, and throat clearing or mucus sensation symptoms in the setting of patients managed with laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) treatment, voice therapy, or vocal fold augmentation.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The project described was supported by the National Center for Research Resources Grant No. UL1 RR025752 and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Grant No. UL1 TR000073. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr Carroll is a consultant for Merz Global and PENTAX Medical.

References

- 1.Gartner-Schmidt J, Rosen C. Treatment success for age-related vocal fold atrophy. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:585–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davids T, Klein AM, Johns MM III. Current dysphonia trends in patients over the age of 65: is vocal atrophy becoming more prevalent? Laryngoscope. 2012;122:332–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reulbach TR, Belafsky PC, Blalock PD, Koufman JA, Postma GN. Occult laryngeal pathology in a community based cohort. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;124:448–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gregory ND, Chandran S, Lurie D, Sataloff RT. Voice disorders in the elderly. J Voice. 2012;26:254–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woo P, Casper J, Colton R, Brewer D. Dysphonia in the aging: physiology versus disease. Laryngoscope. 1992;102: 139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koufman JA, Amin MR, Panetti M. Prevalence of reflux in 113 consecutive patients with laryngeal and voice disorders. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:385–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen SM, Garrett CG. Hoarseness: is it really laryngopharyngeal reflux? Laryngoscope. 2008;118(2):363–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altman KW, Atkinson C, Lazarus C. Current and emerging concepts in muscle tension dysphonia: a 30-month review. J Voice. 2005;19:261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Reulbach TR, Holland BW, Koufman JA. Muscle tension dysphonia as a sign of underlying glottic insufficiency. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:448–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rees CJ, Henderson AH, Belafsky PC. Postviral vagal neuropathy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2009;118(4):247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroll TL, Gartner-Schmidt J, Statham MM, Rosen CA. Vocal process granuloma and glottal insufficiency: an over-looked etiology? Laryngoscope. 2010;120:114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carroll TL, Wu YE, McRay M, Gherson S. Frame by frame analysis of glottic insufficiency using laryngovideostroboscopy. J Voice. 2012;26(2):220–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Validity and reliability of the Reflux Symptom Index (RSI). J Voice. 2002;16:274–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu EW, Bauer SR, Bain PA, Bauer DC. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of fractures: a meta-analysis of 11 international studies. Am J Med. 2011;124(6):519–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato K, Hirano M. Age-related changes of elastic fibers in the superficial layer of the lamina propria of vocal folds. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1997;106:44–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pontes P, Brasolotto A, Behlau M. Glottic characteristics and voice complaint in the elderly. J Voice. 2005;19(1):84–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]