Abstract

Objective: To determine if presence of co-existing medically unexplained syndromes or psychiatric diagnoses affect symptom frequency, severity or activity impairment in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.

Patients: Sequential Chronic Fatigue Syndrome patients presenting in one clinical practice.

Design: Participants underwent a psychiatric diagnostic interview and were evaluated for fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome and/or multiple chemical sensitivity.

Main Measures: Structured Clinical Interview [SCID] for DSM-IV; SF-36, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Pain Short Form; Patient Health Questionnaire-8; Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI-20), CDC Symptom Inventory

Results: Current and lifetime psychiatric diagnosis was common (68%) increasing mental fatigue/health but no other illness variables and not with diagnosis of other medically unexplained syndromes. 81% of patients had at least one of these conditions with about a third having all three co-existing syndromes. Psychiatric diagnosis was not associated with their diagnosis. Increasing the number of these unexplained conditions was associated with increasing impairment in physical function, pain and rates of being unable to work.

Conclusions: Patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome should be evaluated for current psychiatric conditions because of their impact on patient quality of life, but they do not act as a symptom multiplier for the illness. Other co-existing medically unexplained syndromes are more common than psychiatric co-morbidities in patients presenting for evaluation of medically unexplained fatigue and are also more associated with increased disability and the number and severity of symptoms.

Key messages

When physicians see patients with medically unexplained fatigue, they often infer that this illness is due to an underlying psychiatric problem.

This paper shows that the presence of co-existing psychiatric diagnoses does not impact on any aspect of the phenomenology of medically unexplained fatigue also known as chronic fatigue syndrome. Therefore, psychiatric status is not an important causal contributor to CFS.

In contrast, the presence of other medically unexplained syndromes (irritable bowel syndrome; fibromyalgia and/or multiple chemical sensitivity) do impact on the illness such that the more of these that co-exist the more health-related burdens the patient has.

Keywords: Fatigue, widespread pain, unexplained illness

Introduction

Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) is a medically unexplained illness characterised by the new onset of fatigue, severe enough to produce a substantial decrease in activity, not relieved by rest, lasting for more than 6 months and accompanied by rheumatologic, infectious and neuropsychiatric symptoms [1,2]. Other clinically defined, medically unexplained illnesses often co-exist. One report noted considerable overlap in symptoms, as well as diagnosis, among patients with ME/CFS and those with the body-wide pain syndrome indicative of fibromyalgia (FM) and the syndrome of marked sensitivity to smells and odours indicative of multiple chemical sensitivity (MCS) [3]. In an analysis of 32 patients with this illness, nearly half had co-existing MCS and an eighth had FM; importantly, patients having more than one diagnosis had more disability than those with one diagnosis alone [4]. In addition to FM and MCS, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) also appears to exist frequently in patients with ME/CFS [5]. A prior study found an additional burden of lifetime psychiatric diagnosis in those with more than one diagnosis [6]. Patients with medically unexplained fatigue often fulfil criteria for major depressive disorder [6] and patients with depression often have somatic symptoms [7]. The objective of this report is to examine the impact of having one or more of the medically unexplained comorbid illnesses as well as current psychiatric diagnoses on ME/CFS symptom frequency and severity and risk of disability.

While the 2015 clinical case definition for ME/CFS advanced by the 2015 Institute of Medicine report [8] does not exclude diagnosis of ME/CFS on the basis of any other concurrent diagnoses, earlier case definitions, such as the 1994 research definition [1], considered some medical and psychiatric conditions as exclusionary. Exclusion, for research purposes, was to remove the contributions of illnesses with similar symptoms that could confound the understanding of ME/CFS. In this study we used the 1994 research case definition so patients diagnosed with one or more of the exclusionary medical and psychiatric conditions were not included and those in our study will be classified as having CFS.

We enrolled participants meeting criteria for CFS sequentially from new patients presenting to one academic specialist clinic and systematically evaluated them for FM, IBS, and MCS. Patients were grouped based on the number of comorbid conditions (0–3) from which they suffered. We also screened participants for psychiatric diagnoses and grouped them accordingly into three groups: no current psychiatric diagnosis, current psychiatric diagnosis, or psychiatric diagnosis more than 6 months previously. This stratification allowed us to test several hypotheses. One was that those patients with comorbid psychiatric diagnoses would have more functional impairment and worse symptoms than those with CFS absent comorbid psychiatric diagnosis. A second hypothesis was that a patient with CFS and a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis would be more likely to have comorbid medically unexplained illnesses. And finally, that patients with multiple medically unexplained illnesses comorbid with their CFS would be more symptomatic and have poorer functioning with each additional diagnosis.

Methods

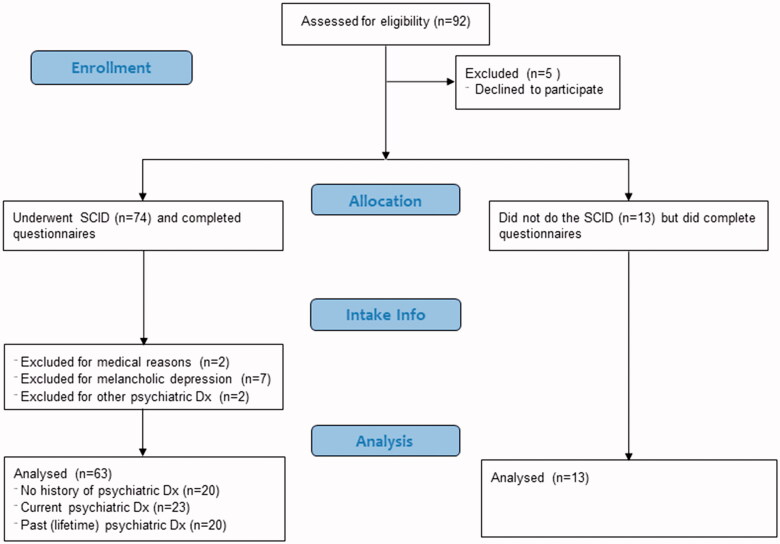

The subjects were 92 patients (see Figure 1 for flow chart of study), seen consecutively at the Pain & Fatigue Study Centre at the Union Square location of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City between 2012–2013 for the presumed diagnosis of CFS. All subjects signed an informed consent and were asked to return for data collection. Of these, 5 patients were withdrawn without taking part in any study procedures as they did not return.

Figure 1.

Diagram showing break down of subjects in this study.

All other patients (n = 87) underwent face-to-face evaluation for criteria in the 1994 research case definition as previously reported [1] (modified to capture symptom severity), requiring: new onset of fatigue, lasting at least 6 months, and producing at least a substantial decrease in activity in work/school, personal or social arenas where substantial was defined as 3 on a 0 to 5 visual analogue scale severity scale (0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = substantial, 4 = severe, 5 = very severe); and, at least three of the following symptoms producing at least a substantial burden (at least 3 on the 0 to 5 visual analogue scale) and one more symptom producing at least a moderate (2 or worse) burden (sore throat, tender lymph nodes, headache, myalgia, arthralgia, unrefreshing sleep, post exertional malaise, cognitive problems with attention or memory). We evaluated balance with the standard Romberg and tandem Romberg (with one foot in front of and touching the foot behind) tests, defining abnormal as failure to maintain either posture for 10 sec. We asked patients if they were currently working or if they were unable to work due to disability.

Participants were also evaluated for FM, MCS and IBS. We applied the 1990 case definition for FM requiring at least 3 months of widespread pain (defined as involving four bodily quadrants or three of these plus truncal) accompanied by tenderness at more than 10 of 18 bodily points when probed with 4 kg/1.54 cm2 of pressure [9]. MCS was diagnosed based on participants’ responses indicating sensitivity to more than one smell/odor associated with symptoms affecting more than one organ system severe enough to result in avoiding exposure. For IBS, we applied the Rome II criteria [10] based on participants’ report of at least 3 months of abdominal pain with two positive responses out of a possible of three related to how this pain affected defaecation.

Participants also completed questionnaires concerning symptoms and wellness scales [(Short Form Health Survey [11] (SF-36v2), Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory [12] (MFI-20), the PROMIS measures (Pain Intensity and Pain Behaviour) and the CDC Symptom Inventory (CDC-SI)]. The CDC-SI was scored as previously described [13] and included post-exertional fatigue, unrefreshing sleep, problems remembering or concentrating, muscle aches and pains, joint pain, sore throat, tender lymph node and swollen gland, and headaches as CFS symptoms. Other questionnaires included the Zung self-rating depression scale [14] (normed to 100) and the Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale (PHQ-8) [15]. See Table 1 for additional information concerning these questionnaires.

Table 1.

Details about the questionnaires used in this study.

| Questionnaire | Description | # Items | Score range |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDC Symptom Inventory (CDC SI) [13]* | Occurrence, frequency and intensity of symptoms common in CFS and other fatiguing illnesses. Used in studies of ME/CFS | 19 | 0–16 for each symptom Higher values = more |

| Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form Health Survey [11] (SF-36v2) |

General indicator of function and wellbeing in 8 areas (physical activities, social activities, usual role activities, bodily pain, general mental health, limitations due to emotional problems, vitality (energy and fatigue), and general health perception. Widely used in health studies | 36 | 0–100 on 8 scales Low score = more disability |

| Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory [12] (MFI-20) |

Self-reported measure of fatigue covering dimensions of General Fatigue, Physical Fatigue, Mental Fatigue, Reduced Motivation, and Reduced Activity. Widely used since 1995, validated in ME/CFS | 20 | 4–20 on each scale Higher score = more fatigue |

| PROMIS Pain Behaviour Short Form (PROMIS-PB SF) |

Seven self-reported measures of external manifestations of pain over the past 7 days, including observable displays (sighing, crying), pain severity behaviour (resting, guarding, facial expressions, asking for help) and verbal reports of pain. Validated for use in many illnesses | 7 | 36.7–75.9 Higher values = more pain |

| PROMIS Pain Interference Short Form (PROMIS-PI SF) | Six self-reported measures of the consequences of pain on social, cognitive, emotional, physical and recreational activities as well as on sleep and enjoyment of life, over the past 7 days | 6 | 41–78.3 Higher values = more pain |

| Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale [15] (PHQ-8) |

Comparable to PHQ-9 in diagnosing depressive disorders; omits suicidal ideation. Widely used | 8 | 0–24 Higher value = more depression |

| Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale [14] (Zung SDS) |

Quantifies the severity of current major depression | 20 | 20–80 Higher values – increased depression |

Current CDC-SI and scoring are available at http://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/programs/wichita-data-access/symptom-inventory.pdf and http://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/programs/wichita-data-access/si-scoring-algorithm.pdf.

Of the 87 patients who completed the face-to-face evaluation and at least some of the questionnaires, 74 agreed to and completed a telephone-administered Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic/Statistical Manual-IV [16]. Based on the 1994 case definition, patients would not be classified as meeting criteria for CFS if they had schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, melancholic depression, eating disorder within 5 years from intake, or drug/alcohol abuse within 2 years from intake. Results of the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic/Statistical Manual-IV were used to classify patients into three groups; those who had never received a diagnosis of a psychiatric condition, those with a psychiatric diagnosis within the past 6 months – i.e. current, and those who had received a psychiatric diagnosis more than 6 months prior to intake, but did not currently have such a diagnosis.

For the comparison of symptoms across the groups defined by psychiatric status, data were analysed using separate analyses of variance for each subscale and applying the Holm-Bonferroni correction to control for multiple comparisons within each scale. The level of significance (α) for all tests was set at a basal value of 0.05. Depending on the number of comparisons within a particular scale, α was adjusted to a more conservative value via the correction above as a method of controlling the family-wise error rate. A significant omnibus test was followed with a post-hoc analysis, Tukey’s Honest Significance Difference, to identify any pairwise differences. We conducted group comparisons for each of the individual symptom measures of the CDC-SI in addition to the composite scores. Scores for the individual CDC-SI items reflect the frequency, intensity, and duration of each symptom (symptom severity score = frequency x intensity, if duration ≥ 6 months). Fisher’s exact tests were calculated to compare patient groups defined by their psychiatric status in order to evaluate if that status was related to the presence of comorbid medically unexplained illnesses. For the comparison of symptoms across the groups defined by the number of comorbid medically unexplained illnesses, we opted to test the directional hypothesis that patients with a greater number of comorbid conditions would have worse symptom reports. To do so we employed separate Jonckheere-Terpstra tests, to identify any significant trends, for each subscale and applied the Holm-Bonferroni correction to control for multiple comparisons within each scale. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows software, version 24.

Results

Two subjects were excluded for medical reasons (one was a chronic hyperventilator and one had a history of heart disease). Nine patients, all women, were excluded due to psychiatric diagnoses exclusionary for CFS: 7 with melancholic depression, one with bipolar disorder, and one with binge eating disorder; of these, two had no psychiatric diagnosis within the past 6 months. In addition, 13 of the patients did not complete the psychiatric diagnostic interview and so their psychiatric status was not confirmed. Of the 63 patients remaining, 23 (36%) had a current psychiatric diagnosis (Current-psych group), 20 (32%) never had a psychiatric diagnosis (No-psych group) and 20 (32%) had a history of such a diagnosis occurring more than 6 months prior to intake (Prior-psych group).

The three groups had similar demographics (Table 2) and proportions with comorbid FM, IBS or MCS (Table 3). The number of patients with comorbid conditions was also similar between groups. Post-exertional malaise, a required symptom for some ME/CFS case definitions, was endorsed by all but four patients (Current-psych, n = 2; Prior-psych, n = 1, and No-psych, n = 1). Patient groups were comparable in regard to illness duration, number of medications, severity of post-exertion malaise, onset type – i.e. gradual or sudden or self-reported disability (Table 2). Abnormal results on the Romberg balance tests were identified for almost a quarter of patients (15 of 62; 24.2%; one member of the Prior-psych group did not complete balance testing). A minority of patients within each Current-psych (5 of 23, 21%), Prior-psych (7 of 19, 37%) and No-psych groups (3 of 20; 15%) tested positive for a balance abnormality.

Table 2.

Demographics and Illness Characteristics by Status of Psychiatric Comorbidity in 63 Patients with CFS Seen in a Specialty Clinic.

| Current-psych (n = 23) |

Prior-psych (n = 20) |

No-psych (n = 20) |

Total (n = 63) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 49.4 (11.3) | 47.0 (11.0) | 45.6 (8.8) | 47.5 (10.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.0 (4.4) | 28.4 (10.6) | 25.4 (4.2) | 26.2 (7.0) |

| Sex (% female) | 83% | 85% | 75% | 81% |

| Race/Eth. (% min.) | 13% | 20% | 15% | 16% |

| Not employed (% yes) | 70% | 70% | 70% | 70% |

| Fatigue duration (years) | 15.6 (10.6) | 13.7 (8.6) | 11.0 (7.4) | 13.5 (9.1) |

| No. of medications | 2.5 (3.2) | 2.3 (3.3) | 3.4 (3.7) | 2.7 (3.4) |

| Severity of PEM | 11.7 (5.0) | 10.4 (4.7) | 11.6 (5.1) | 11.24 (4.9) |

| Onset (% gradual) | 65% | 63% | 55% | 62% |

| Disabled (% yes) | 52% | 55% | 65% | 57% |

BMI: Body Mass Index; Eth.: Ethnicity; min.: minority; Not employed: Self-reported status indicating the patient is not currently working, reason unspecified; No. of Medications: Number of current physician-prescribed medications; Severity of PEM: The item score from the CDC Symptom Inventory reflecting intensity, frequency, and duration of “Unusual fatigue after exertion”; Disabled: Self-reported status indicating the patient’s disability prevents them from working; Current-psych: Patients with a current psychiatric diagnosis; Prior-psych: Patients who have received a psychiatric diagnosis in the past, but have since recovered; No-psych: Patients who have never received a psychiatric diagnosis.

Table 3.

Prevalence of other Comorbid Conditions by Status of Psychiatric Comorbidity in 63 Patients with CFS Seen in a Specialty Clinic [n (%)].

| Comorbid conditions | Current-psych (n = 23) |

Prior-psych (n = 20) |

No-psych (n = 20) |

Total (n = 63) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 6 (26.1%) | 2 (10%) | 4 (20.0%) | 12 (19.0%) |

| FM Only | 1 (4.3%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (3.2%) |

| IBS Only | 1 (4.3%) | 4 (20%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (7.9%) |

| MCS Only | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (5.0%) | 2 (3.2%) |

| FM & IBS | 2 (8.7%) | 1 (5.0%) | 3 (15.0%) | 6 (9.5%) |

| FM & MCS | 2 (8.7%) | 1 (5.0%) | 2 (10.0%) | 5 (7.9%) |

| IBS & MCS | 5 (21.7%) | 2 (10.0%) | 3 (15.0%) | 10 (15.9%) |

| FM, IBS & MCS | 6 (26.1%) | 8 (40.0%) | 7 (35.0%) | 21 (33.3%) |

FM: Fibromyalgia; IBS: Irritable Bowel Syndrome; MCS: Multiple Chemical Sensitivity.

Significant differences between groups were detected for the Zung SDS (F2,57 =4.45, p = .02; data not shown) and the PHQ-8 inventories (F2,50 =5.95, p = .01; data not shown). Respective means and standard deviations, mean differences (MD), and 95% confidence intervals for the differences (95% CI) are reported for the following comparisons. Post-hoc comparisons for the Zung scale indicated that the Current-psych group [60.9 (10.3)] had significantly higher depression scores compared to the No-psych group [53.0 (10.0), MD = 7.9, 95% CI (4.1–14.7)]. For the PHQ-8 scale, Current-psych patients [12.1 (4.2)] scored significantly higher on depression compared to both the No-psych [8.4 (3.6), MD = 3.7, 95% CI (0.7–6.7)] and Prior-psych patients [8.5 (3.1), MD = 3.6, 95% CI (0.6–6.6)]. Differences remained significant after correction for multiple comparisons (Holm-Bonferroni method) within the context of each scale. Of interest, the Prior-psych group resembled the No-psych group on these scores.

The psychiatric diagnosis groups significantly differed on the scores of MFI-20 mental fatigue (F2,60 = 5.03, p = .01) and SF-36 mental health (F2,60 = 8.65, p < .001) but were similar for nearly all other measures of symptom severity (Table 4). The mean score of the MFI-20 mental fatigue was higher for patients with Current-psych [17.1 (2.9)] than those with No-psych [13.8 (4.2), MD = 3.3, 95% CI (0.6, 6.0)]. Patients with Prior-psych [14.4 (3.9)], however, were not significantly different from either of the other two groups in regards to mental fatigue. Scores in the SF-36 Mental Health subscale were significantly lower for Current-psych patients [56.1 (20.2)] compared with the Prior-psych [69.7 (14.2), MD= −13.6, 95% CI (−25.8, −1.4) and No-psych groups [76.8 (14.1), MD= −20.7, 95% CI (−32.9, −8.4)]. Composite scores for the CDC-SI (i.e. total symptom score, total CFS symptom score, total number of symptoms, number of CFS symptoms) (Table 4) as well as individual symptom scores did not differ among the groups, except for the depression symptom score [F2,59=8.84, p < .001; data not shown]. The Current-psych group [3.8 (4.4)] had higher CDC SI Depression symptom scores than both the Prior-psych [1.1 (2.2), MD = 2.7, 95% CI (0.6–4.9)] and No-psych groups [0.2 (0.4), MD = 3.6, 95% CI (1.4–5.8)]). This difference remained significant after correction for multiple comparisons within the context of the scale.

Table 4.

Measures of Illness by Psychiatric Comorbidity Group in 63 Patients with CFS Seen in a Specialty Clinic [Mean (SD)].

| Measure Name, Min. – Max. Value | Current-psych (n = 23) |

Prior-psych (n = 20) |

No-psych (n = 20) |

Total (n = 63) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Fatigue (MFI), 4–20 | 18.7 (1.4) | 18.5 (2.0) | 18.5 (1.3) | 18.6 (1.6) |

| Physical Fatigue (MFI), 4–20 | 18 (2.2) | 17.3 (2.7) | 17.5 (1.9) | 17.6 (2.3) |

| Reduced Activity (MFI), 4–20 | 16.5 (3.1) | 16.0 (3.7) | 16.4 (2.8) | 16.3 (3.2) |

| Reduced Motivation (MFI), 4–20 | 13.3 (5.0) | 12.8 (3.1) | 10.3 (4.5) | 12.2 (4.4) |

| Mental Fatigue (MFI), 4–20 | 17.1 (2.9)a | 14.4 (3.9) | 13.8 (4.2) | 15.2 (3.9) |

| Physical Function (SF-36), 0–100 | 42.2 (20.3) | 42.3 (21.7) | 34 (17.7) | 39.6 (20) |

| Role Limits Phys. (SF-36), 0–100 | 17.3 (19.4) | 20.4 (18.2) | 14.1 (17.0) | 17.3 (18.2) |

| Bodily Pain (SF-36), 0–100 | 39.2 (25.9) | 33.2 (22.0) | 29.3 (13.8) | 34.2 (21.5) |

| Social Function (SF-36), 0–100 | 26.6 (19.3) | 26.3 (20.6) | 23.1 (16.9) | 25.4 (18.8) |

| Mental Health (SF-36), 0–100 | 56.1 (20.2)b | 69.7 (14.2) | 76.8 (14.1) | 67.0 (18.6) |

| Role Limits Emo. (SF-36), 0–100 | 69.9 (31.4) | 79.6 (26.8) | 87.1 (18.4) | 78.4 (26.9) |

| Vitality, Eng./Fat. (SF-36), 0–100 | 16.1 (14.1) | 18.4 (13.1) | 17.5 (10.8) | 17.3 (12.7) |

| General Health (SF-36), 0–100 | 29.1 (20.3) | 25.3 (15.3) | 27.7 (18.0) | 27.4 (17.9) |

| CFS Score (CDC-SI), 0–128 | 33.7 (23.6) | 30.9 (16.7) | 35.6 (22.1) | 33.4 (20.9) |

| Total Score (CDC-SI), 0–304 | 59.5 (27.0) | 55.7 (24.0) | 63.4 (17.9) | 59.5 (23.3) |

| No. of CFS Symp. (CDC-SI), 0–8 | 5.8 (2.0) | 5.8 (2.0) | 6.3 (1.6) | 5.9 (1.8) |

| No. of Symp. (CDC-SI), 0–19 | 10.8 (4.2) | 10.8 (4.4) | 12.5 (3.6) | 11.3 (4.1) |

Role Limits Phys.: Role Limits due to Physical Problems; Role Limits Emo.: Role Limits due to Emotional Problems; Eng./Fat.: Energy/Fatigue; CFS: Chronic Fatigue Syndrome; Symp.: Symptoms; No.: Number.

Significantly different from the No-psych group following correction for multiple comparisons (p < 0.01).

Significantly different from the Prior- and No-psych groups following correction for multiple comparisons (p < 0.001).

Thirteen patients, assessed on intake for comorbid FM, IBS and MCS, did not complete the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic/Statistical Manual-IV but did complete the other questionnaires. IBS, MCS and FM were comorbid with CFS in 67%, 58% and 54% of study participants, respectively, 81% had at least one of these comorbid conditions, and about a third of those with CFS had all three comorbidities (Table 5).

Table 5.

Breakdown of Comorbid Condition Group by Number and Specific Conditions in 76 Patients with CFS Consecutively Seen in a Specialty Clinic.

| No. of Comorbid Conditions | n (%) | Specific Condition (s) | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 14 (18.4%) | – | |

| 1 | 13 (17.1%) | FM Only | 4 (5.3%) |

| IBS Only | 7 (9.2%) | ||

| MCS Only | 2 (2.6%) | ||

| 2 | 24 (31.6%) | FM & IBS | 7 (9.2%) |

| FM & MCS | 5 (6.6%) | ||

| IBS & MCS | 12 (15.8%) | ||

| 3 | 25 (32.9%) | – | |

No.: Number; FM: Fibromyalgia; IBS: Irritable Bowel Syndrome; MCS: Multiple Chemical Sensitivity.

We categorised the sample into four groups, each defined by the number (i.e. 0–3) of comorbid conditions (i.e. FM, IBS, and MCS). The four groups (0 comorbidities, n = 14; 1 comorbidity, n = 13; 2 comorbidities, n = 24; 3 comorbidities, n = 25) were comparable in regards to the demographic variables collected (i.e. age, height, weight, BMI, % female, % minority, % sudden onset).

We evaluated illness characteristics using the MFI-20, SF-36, CDC-SI, and PROMIS Pain questionnaires. We examined trends in scores by number of comorbid conditions to evaluate whether symptoms worsened with a greater number of comorbid conditions (Table 6). Many of the illness measures indicated worsening or greater impairment with greater number of comorbid conditions. On the SF-36, significant trends were noted for the SF-36 Physical Function (JT = 3.411, p < .001) and Bodily Pain scores (JT = 3.602, p < .001). Significant trends were also observed for the symptom severity scores (CFS symptoms and total symptoms) and number of symptoms as measured with CDC-SI (CFS severity Score, JT = 2.584, p = .01; Total Severity Score, JT = 3.960, p < .001; number of CFS Symptoms, JT = 3.870, p < .001; Total number of Symptoms, JT = 3.185, p < .001). On the PROMIS Pain measures, scores on the Pain Intensity (JT = 3.711, p < .001) and Pain Behaviour scales (JT = 3.041, p < .001) were significantly higher for patients with a greater number of comorbid conditions. No significant trends were identified for the MFI-20 subscales.

Table 6.

Measures of Illness by the Number of Comorbid Conditions in 76 Patients with CFS Consecutively Seen in a Specialty Clinic [Mean (SD)].

| Number of Comorbid Conditions of FM, IBS, and MCS |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure Name, Min. – Max. Value | 0 (n = 14) |

1 (n = 13) |

2 (n = 24) |

3 (n = 25) |

Total (n = 76) |

| General Fatigue (MFI), 4–20 | 18.8 (1.4) | 17.9 (2.1) | 18.5 (1.4) | 18.8 (1.3) | 18.6 (1.5) |

| Physical Fatigue (MFI), 4–20 | 18.4 (1.8) | 17.3 (2.5) | 17.5 (2.2) | 17.7 (2.4) | 17.7 (2.3) |

| Reduced Activity (MFI), 4–20 | 16.9 (3.2) | 17.4 (3.2) | 15.3 (3.2) | 16.5 (3.3) | 16.3 (3.3) |

| Reduced Motivation (MFI), 4–20 | 11.9 (4.9) | 13.6 (3.1) | 11.1 (4.5) | 12.6 (4.4) | 12.2 (4.4) |

| Mental Fatigue (MFI), 4–20 | 16.3 (2.9) | 15.5 (2.8) | 14.2 (5.2) | 15.6 (3.6) | 15.3 (4) |

| Physical Function (SF-36), 0–100 | 48.2 (25.6) | 47.9 (14.6) | 37.9 (18.6) | 29.9 (16.8)a | 38.9 (20.1) |

| Role Limits Phys. (SF-36), 0–100 | 16.5 (12.4) | 16.3 (20.7) | 18.5 (22.7) | 13.8 (15.8) | 16.2 (18.4) |

| Bodily Pain (SF-36), 0–100 | 50.9 (26.6) | 39.2 (15.7) | 31.6 (16.9) | 24.7 (17.4)a | 34.2 (20.9) |

| Social Function (SF-36), 0–100 | 28.6 (22.2) | 26.0 (18.0) | 23.4 (21.0) | 25.0 (14.4) | 25.3 (18.5) |

| Mental Health (SF-36), 0–100 | 69.3 (18.9) | 56.2 (14.6) | 69.3 (21.7) | 65.6 (19.0) | 65.8 (19.5) |

| Role Limits Emo. (SF-36), 0–100 | 95.2 (11.7) | 57.1 (34.3) | 79.2 (27.3) | 72.3 (32.1) | 76.1 (30.1) |

| Vitality, Eng./Fat. (SF-36), 0–100 | 12.1 (8.3) | 17.3 (13.8) | 18.5 (13.4) | 18.1 (11.9) | 17 (12.2) |

| General Health (SF-36), 0–100 | 26.7 (15.6) | 28.7 (15.5) | 32.3 (20.0) | 23.6 (15.6) | 27.8 (17.2) |

| CFS Score (CDC-SI), 0–128 | 25.3 (12.5) | 33.8 (29.3) | 29.7 (19.8) | 42.2 (20.4)b | 33.7 (21.4) |

| Total Score (CDC-SI), 0–304 | 46.1 (17.1) | 48.0 (25.2) | 59.0 (25.0) | 71.4 (18.6)a | 58.8 (23.6) |

| No. of CFS Symp. (CDC-SI), 0–8 | 4.6 (1.3) | 5.3 (2.5) | 5.7 (2.1) | 6.9 (1.1)a | 5.8 (1.9) |

| No. of Symp. (CDC-SI), 0–19 | 8.9 (2.9) | 10.2 (5.9) | 10.9 (4.6) | 13.3 (2.7)a | 11.2 (4.3) |

| Pain Intensity (PROMIS), T score 41.0–78.3 | 15.0 (7.9) | 15.7 (6.8) | 20.9 (6.8) | 22.9 (5.6)a | 19.6 (7.3) |

| Pain Behaviour (PROMIS), T score 36.7–75.9 | 20.5 (8.7) | 22.2 (6.1) | 24.4 (6.1) | 27.1 (3.7)b | 24.2 (6.4) |

Reduced Motiv.: Reduced Motivation; Role Limits Phys.: Role Limits due to Physical Problems; Role Limits Emo.: Role Limits due to Emotional Problems; Eng./Fat.: Energy/Fatigue; CFS: Chronic Fatigue Syndrome; Symp.: Symptoms; No.: Number.

aSignificant trend (p < .001). bSignificant trend (p < .01).

The proportion of patients reporting inability to work due to disability increased in a significant linear trend with the number of comorbidities (data not shown, Mantel-Haenszelchi-square = 7.551, p = .01).

Discussion

We found that CFS patients with or without current or past psychiatric diagnoses were comparable in regards to measures of their illness (activity, pain, fatigue) as assessed with standardised questionnaires (MFI-20, SF-36, PROMIS Pain, CDC-SI). These findings support prior results that psychiatric status of patients with CFS did not affect brain neurochemical findings [17] as well as the findings in the recent Institute of Medicine (now National Academy of Medicine) report on ME/CFS [8]. Psychiatric diagnoses have been reported to act as an illness multiplier producing worse symptoms and more disability in somatisation disorders [18] – a psychiatric diagnosis made in cases of medically unexplained symptoms. CFS, although still medically unexplained, does not fulfil the earlier, agreed upon criteria for somatisation disorder [19], and our findings provide additional evidence for specifically using the diagnosis of CFS (or ME/CFS) rather than including it in the broad category of “somatic symptom disorder.” Viewing CFS as a psychiatric condition can lead to stigmatization [20] by physicians, creating barriers to the care of patients living with this chronic and often disabling condition. Our data suggest that depression and/or anxiety are independent disease processes from CFS. Patients with CFS and current co-existing psychiatric illness did have higher scores for depression in the Zung SDS and PHQ-8 questionnaires as well as more mental fatigue (MFI-Mental Fatigue) and poorer mental health (SF-36 Mental Health) as could have been anticipated. Because psychiatric illness impacts patient’s quality of life, physicians should diagnose and treat any co-existing psychiatric illnesses in their patients with CFS while remaining cognisant that effectively treating psychiatric conditions will have little impact on the patient’s CFS symptoms.

By contrast, the presence of another co-morbid condition significantly worsened nearly every measure of illness. The impact increased with each additional co-morbid condition. Importantly, only a minority of patients with CFS (18%) did not have FM, IBS or MCS. MCS was the most frequent co-morbid diagnosis (58%), followed by IBS (51%) and FM (47%). While the rate of MCS in this study was higher than in previous studies [4,21], probably because we did not require the existence of an initiating event for its diagnosis, those for co-existing FM [22,23] and IBS [24] were within the range previously reported here. Maixner and colleagues have noted that any one pain syndrome can often be accompanied by another, and they have suggested that these overlapping pain-related syndromes can be considered to be “chronic overlapping pain syndromes;” they have included ME/CFS among these disorders – implicating sensory amplification as the underlying cause of the pain in all [25]. However, in an assessment of this hypothesis, Geisser et al. found support for FM or for CFS plus FM but not for CFS alone suggesting differences between CFS alone and FM with or without coexisting CFS. One of the authors of this paper (BHN) has viewed the question of whether CFS and FM is the same or different illnesses to be an empiric one and has summoned evidence, recently reviewed [26], to support the position that the two have different underlying pathophysiological processes responsible for each and independent of the other.

Prior studies [6,21] have noted that the presence of comorbid conditions occurring with CFS lead to more disability – an effect also noted here. In addition, it does appear that CFS patients with comorbid conditions are more likely to report a greater number of symptoms, both CFS-related and general, as well as reporting greater severity of these symptoms. Importantly, patients seemed to fall out into two groups – those with CFS alone and those with CFS plus one or more other medically unexplained illnesses. Future research will be critical in determining if these two forms of CFS have the same or different underlying pathophysiological causes.

A strength of this study is that study subjects were enrolled sequentially and carefully evaluated for each diagnosis. As nearly all patients agreed to participate, the sample is representative of the clinic. The use of standardised questionnaires to characterise symptoms and impact of illness provide a full phenotypic description of the study population. The data reported are comparable to other reports of CFS from tertiary care clinics [21,22] suggesting that the patients studied were not dissimilar. However, as with all studies, this study does have weaknesses. Enrolment was restricted to one academic referral clinic, so the patients may not be representative of those presenting initially to primary care clinics. Patients had been ill an average of 13.4 years. Longitudinal data would be needed to determine the timing of additional co-morbid diagnoses, or even if one of the comorbid diagnoses preceded CFS. Furthermore, we did not evaluate patients for other comorbid diagnoses such as migraine headache, interstitial cystitis and temporomandibular joint dysfunction.

In summary, while a current psychiatric diagnosis does require identification and treatment because of its impact on a patient’s mental health and quality of life, it does not act as a symptom multiplier for CFS. By contrast, CFS patients with all three of the comorbid conditions evaluated (i.e. FM, IBS, and MCS) have a greater symptom burden than those CFS patients without a comorbid condition. In addition, a greater number of comorbid conditions is related to an increased likelihood of unemployment due to disability. The existence of other medically unexplained diagnoses that increase the morbidity and illness burden of patients with CFS is very common, emphasising the need for an individualised approach to symptom management.

Disclosure statement

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. None of the authors have any competing interests.

References

- 1.Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, et al. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121(12):953–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carruthers BM, van de Sande MI, De Meirleir KL, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria. J InternMed. 2011;270(4):327–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchwald D, Garrity D. Comparison of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and multiple chemical sensitivities. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154(18):2049–2053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jason LA, Taylor RR, Kennedy CL. Chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and multiple chemical sensitivities in a community-based sample of persons with chronic fatigue syndrome-like symptoms. Psychosomatic Med. 2000;62(5):655–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagy-Szakal D, Williams BL, Mishra N, et al. Fecal metagenomic profiles in subgroups of patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Microbiome. 2017;5(1):44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciccone DS, Natelson BH. Comorbid illness in the chronic fatigue syndrome: a test of the single syndrome hypothesis. Psychosom Med. 2003;62(2):268–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapfhammer HP Somatic symptoms in depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8(2):227–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.IOM. Beyond myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: redefining an illness. Washington (DC) 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia: Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(2):160–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, et al. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut. 1999;45(Supplement 2):Ii43–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 physical and mental summary scales: a user’s manual. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smets EM, Garssen B, Bonke B, et al. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39(3):315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner D, Nisenbaum R, Heim C, et al. Psychometric properties of the CDC Symptom Inventory for assessment of chronic fatigue syndrome. Popul Health Metrics. 2005;3(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zung WW A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12(1):63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, et al. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(1-3):163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.First MBS, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-1V-TR Axis 1 Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition (SCID-1/NP). New York: Biometrics Research New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Natelson BH, Mao X, Stegner AJ, et al. Multimodal and simultaneous assessments of brain and spinal fluid abnormalities in chronic fatigue syndrome and the effects of psychiatric comorbidity. J Neurol Sci. 2017;375:411–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen LA, Escobar JI, Lehrer PM, et al. Psychosocial treatments for multiple unexplained physical symptoms: a review of the literature. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(6):939–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson SK, DeLuca J, Natelson BH. Assessing somatization disorder in the chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychosom Med. 1996;58(1):50–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green J, Romei J, Natelson BH. Stigma and chronic fatigue syndrome. J Chr Fatigue Syndr. 1999;5(2):63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown MM, Jason LA. Functioning in individuals with chronic fatigue syndrome: increased impairment with co-occurring multiple chemical sensitivity and fibromyalgia. Dyn Med.. 2007;6:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bombardier CH, Buchwald D. Chronic fatigue, chronic fatigue syndrome, and fibromyalgia. Disability and health care use. Med Care. 1996;(9):924–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rusu C, Gee ME, Lagace C, et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia in Canada: prevalence and associations with six health status indicators. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2015;35(1):3–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR. Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology. 2002;122(4):1140–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maixner W, Fillingim RB, Williams DA, et al. Overlapping chronic pain conditions: implications for diagnosis and classification. J Pain. 2016;17(9):T93–T107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Natelson BH Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia: definitions, similarities, and differences. Clin Ther. 2019;41(4):612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]