Abstract

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is the most common subepidermal autoimmune blistering disease. It usually affects people older than 70 years of age. The two main autoantigens are BP180 and BP230, both of which are components of hemidesmosomes. Immunoglobulin (Ig)G and IgE autoantibodies to BP180 detected by the enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) show close associations with the activity and severity of BP. In addition, inflammatory cells (eosinophils, neutrophils and mast cells) and cytokines (e.g. interleukins and CC chemokine ligands) play an important part in the pathogenesis, activity and severity of BP. We summarized the potential contribution of each factor postulated to be associated with the activity and severity of BP, and provide guidance for clinicians to pay timely and close attention to such parameters. This review may also promote the development of novel therapies for BP.

Key Messages

Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index (BPDAI) is a scoring system which can reflect the extent of clinical involvement of BP patients.

The titres of IgE autoantibodies and IgG autoantibodies against the NC16A domain of BP180 are closely correlated with the activity and severity of BP.

Many inflammatory cells and molecules, such as eosinophils and interleukins, can also reflect the activity and severity of BP.

Keywords: BPDAI, BP180, antibody titre, inflammatory cells and molecules

1. Introduction

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is the most common subepidermal autoimmune bullous disease. Clinically, it is characterized by tense blisters with widespread erythema. Histology reveals subepidermal bullae with eosinophil infiltration. Immunology reveals linear deposition of immunoglobulin (Ig)G and/or C3 along the basement membrane zone (BMZ) [1].

The worldwide incidence of BP is 12–66 cases per million people per year, and disease prevalence increases with age [2]. BP can be triggered by environmental factors such as burns, sun exposure, radiation or surgical wounds. It has been reported that dementia, Parkinson’s disease, psychiatric disorders and blood disorders are associated with BP [3].

The diagnosis of BP is based on clinical features, histology of lesions taken by skin biopsies, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) and serum tests (e.g. indirect immunofluorescence [IIF], enzyme-linked immunoassay [ELISA]) [4].

The non-collagenous 16A (NC16A) domain of BP180 and C-terminal domain of BP230 are the major epitopes of BP [5]. IgG autoantibodies against the NC16A domain of BP180 can be detected in >90% of BP patients, whereas autoantibodies against BP230 can be detected in only 60% of BP patients [6]. IgG1 and IgG4 have been reported to be the dominant subclasses of autoantibodies in BP. IgG4 cannot trigger complement activation, so IgG1 is thought to be mainly involved in tissue damage [7]. The binding of autoantibody against hemidesmosome protein leads to complement activation and neutrophilic chemotaxis, which causes degradation of the BMZ and blister formation. However, certain evidence has recently come to support non-complemental blistering mechanisms, and many studies showed that BP-IgG may be sufficient to induce skin fragility without complement activation. Complements are required to induce inflammation and exacerbate the disease [1].

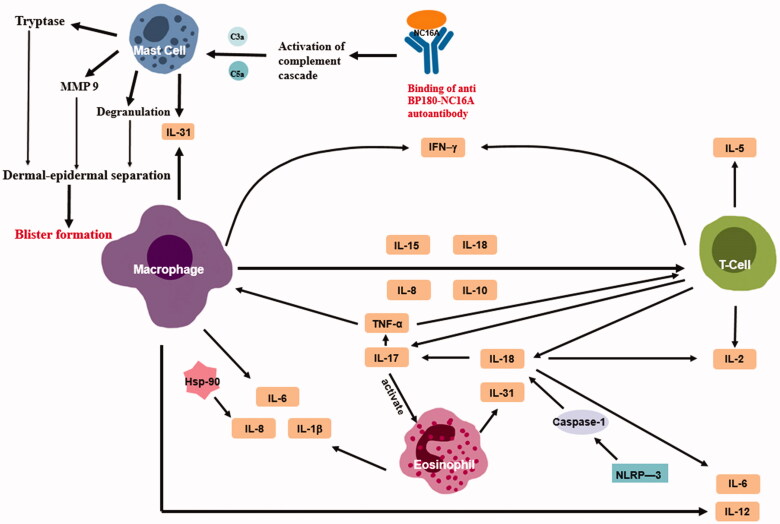

The severity of BP is thought to be correlated with BPDAI, eosinophils and mast cells’ secreted protein level and prothrombotic markers etc. The activity of BP is associated with the concentration of inflammatory molecules (Figure 1). However, antibody titre and individual inflammatory molecules such as IL-17 and IL-23 can reflect both of the activity and severity of BP. However, some researchers hold different opinions. However, until now, there has not been a review of these factors, which are probably related. We critically summarized the most likely factors postulated to be associated with the activity and severity of BP.

Figure 1.

Anti-BP180 autoantibody binding to BP180 NC16A aligning along the basement membrane zone causes mast cells (MCs) to degranulate and releases proteolytic enzymes including metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) and tryptase. This further leads to dermal-epidermal separation, resulting in sub-epidermal blister formation. What is more important that there is an interaction network existing in the inflammatory molecules associated with the activity of BP. Schematic representation of potential connections by which cytokines can reflect the activity and severity of BP.

2. Severity-related factors

2.1. Bullous pemphigoid disease area index (BPDAI)

Bullous pemphigoid disease area index (BPDAI) is the first BP-specific outcome measure used to evaluate the severity of various stages of BP. The total possible score of BPDAI ranges from 0 to 360 (120 points each for blisters, erythematous lesions and mucosal involvement) [2]. BPDAI has a close correlation with the erythematous/eczematous/urticarial skin lesions, number of blisters, and autoantibody titres against BP180 (as tested by the ELISA) of the patient [8]. BP severity can be assessed by counting the number of bullae on the skin [9]. BPDAI is also correlated closely with autoantibody titres against BP180, but not with autoantibody titres against BP230. BP patients with mucosal involvement usually have more severe disease than patients without mucosal involvement, and present with a higher BPDAI score. The titre of IgG autoantibodies against the NC16A domain of BP180 of BP patients with mucosal involvement using the ELISA is also higher than that of patients without mucosal involvement. Such data suggest that the extent of mucosal involvement may be a severity marker [10]. On the basis of previous literature, a total BPDAI score ≥56 could denote “severe BP” [11]. Hence, BPDAI can be considered as an intuitive method for reflecting the severity of the clinical presentation of BP patients.

2.2. Eosinophils’ secreted protein

Eosinophils are the main cells in the lesions of BP patients. It has been reported that eosinophils are present in the peripheral blood of >50% of untreated BP patients, and that eosinophils are correlated with disease activity. Eosinophil infiltration has been postulated to contribute to blister formation. High concentrations of eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) and major basic protein (MBP) have been detected in the serum and blister fluid of BP patients. Neutrophils produce several chemoattractants for eosinophils (e.g. leukotriene B4 and platelet-activating factor), which can lead to eosinophil recruitment [12].

The proteins released from eosinophil granules also influence BP severity. The proteins from eosinophil granules can be detected in the blister fluid and serum of BP patients [12]. Eosinophil activation can be evaluated by the concentrations of granule proteins such as MBP, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin and ECP. Proteins from eosinophil granules can be detected not only in fully developed blisters, but also at the earliest stages of blister formation [12]. Graauw et al. showed that eosinophil activation was associated with blister formation [12]. Due to the ribonuclease activity of eosinophil-derived neurotoxin and ECP, these two granule proteins can disrupt skin integrity and contribute to blister formation. They can be detected in blister fluid and are related closely to BP severity. However, MBP cannot be detected in blister fluid, Giusti et al. discovered that it had a negative correlation with BP severity [13]. Eosinophils also promote matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) releases at blister sites. MMP-9 degrades the extracellular collagenous domain of recombinant 180-kD BP antigen and cleaves dermo–epidermal junctions [12]. In BP patients, there is a close correlation between eosinophilia and circulating levels of total IgE. Messingham et al. found that for BP patients with total IgE ≥400 IU/mL, the eosinophil count in peripheral blood correlated strongly with levels of IgE autoantibodies directed against BP180. This finding could be due to the high-affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI) expressed on eosinophils in BP patients [14].

2.3. Tryptase level

The number of mast cells in the lesions of BP patients is increased. Tryptase is a proteolytic enzyme synthesized and released by mast cells [15]. Tryptase levels in the blister fluid of BP patients are increased, and are correlated positively with the titres of autoantibodies against the BMZ and levels of several chemokines/cytokines: interleukin (IL)-5, IL-6 and IL-8. Hence, the tryptase level can reflect BP severity indirectly [6,16].

2.4. Prothrombotic marker

Activation of the coagulation cascade also contributes to tissue damage and blister formation because thrombosis can increase vascular permeability and amplify inflammatory processes. Tedeschi et al. demonstrated an increased level of the prothrombotic markers F1 + 2 and D-dimer in the serum and blister fluid of BP patients, and that their levels correlated with disease severity [17].

3. Activity-related factors

3.1. Cytokines

Many inflammatory molecules were postulated to have a role in the activity and intensity of BP. The concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 and IL-15 are increased in the serum or blister fluid of BP patients [18–20]. Levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and E-selectin are also increased in BP patients [21]. High levels of IL-5 and eotaxin have been found in blister fluid [22]. Levels of IL-5 and cluster of differentiation (CD)-30 are associated with disease activity. With remission of BP, the concentrations of IL-5 and CD-30 also decline. In addition, the serum titres of IL-18, IL-21, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand (CCL)17 and CCL22 also decrease with clinical improvement upon therapy [23].

IL-31 is a novel T-cell-derived cytokine which plays an important part in controlling multiple immunomodulatory effects (e.g. release of pro-inflammatory cytokines) and contributes to itchiness induction. IL-31 can be secreted by activated T helper (Th) cells, particularly Th2 cells, mast cells, macrophages and dendritic cells [24]. However, recent studies have suggested eosinophils to be the primary source of IL-31 in BP patients [12]. Studies have shown that high levels of IL-31 are not only related to itchiness in BP patients, but also contribute to blister formation [25]. An increased level of IL-31 has been detected in the serum and lesions of BP patients, and is associated significantly with the eosinophil count and increased levels of IgE autoantibodies against BP180 [12]. The number of peripheral-blood eosinophils correlates strongly with BP activity, and pruritus is in parallel with the course of BP, so IL-31 is considered to be a new biomarker for monitoring BP activity [26,27]. Anti-IL-31 antibodies may serve as a novel therapeutic approach to combat BP-related itching symptoms [24].

Cytokines such as interferon (IFN)-γ, IL-1β and TNF-α have been detected at high concentrations in the blister fluid of BP patients, and their concentrations correlate with disease activity [6,28]. Zebrowska et al. showed that IL-36 could be used as a marker of BP activity/remission because the serum concentration of IL-36 was higher in BP patients compared with that of a control group [29].

3.2. Chemokines

The level of chemokines is determined using ELISA kits. Eotaxin-1 (CCL11) and eotaxin-3 (CCL26) belong to the eotaxin subfamily of CC-chemokines, and their expression is up-regulated in the serum and blister fluid of BP patients. CCL26 is also expressed strongly in the lesions of BP patients. CCL11 and CCL26 are associated significantly with eosinophil activation, especially serum levels of CCL26, which has a close correlation with eosinophil numbers in peripheral blood. Hence, CCL26 levels could be useful for assessing BP activity, and have a role in BP development. Blockade of CCL26 function could provide a novel target for treating BP [30]. CCL11 can bind to the CCR3 expressed on eosinophils and induce eosinophil chemotaxis [31]. In addition, several observations presented that levels of eotaxin, IL-5 and CCR3 were increased in the blister fluid as well as the lesional and peri-lesional skin of BP patients. These markers also have a significant correlation with the number of dermal-infiltrating eosinophils [22,32]. There had been a pilot phase 2a study proving that bertilimumab, an anti-eotaxin-1 antibody, was safe and efficacious in the treatment of BP. This finding provided a novel target for treating BP, however, a larger controlled trial would be expected [33].

3.3. CD23

CD23 is a low-affinity Fc receptor for IgE. It is expressed mainly on mature B lymphocytes, but also on monocytes, eosinophils and platelets. It has an affinity for, and regulates the synthesis of IgE. Several studies have shown that CD23 expression is significantly higher in BP patients than in healthy people. The serum level of soluble CD23 is also correlated with the serum IgE level, and acts as a parameter for assessing BP activity [34,35].

3.4. Inflammasome

The inflammasome is a multi-molecular complex which activates pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18 via caspase-1 activation. Caspase-1 is the primary enzyme responsible for the activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Fang et al. found that mRNA expression of the components of the NLRP3 inflammasome (NLRP3, pro-caspase-1 and pro-IL-18) in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of BP patients were significantly higher than those of healthy people [18]. Fang et al. demonstrated that expression of the components of the NLRP3 inflammasome (caspase-1, IL-18 and apoptosis-associated speck-like protein caspase recruitment domain) were correlated positively with autoantibody titres against the NC16A domain of BP180. Hence, NLRP3-inflammasome components were closely related to disease activity. The important pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 can stimulate the release of other cytokines, such as IL-2, IL-6, IL-12, and IL-17A. Hence, the NLRP3–caspase-1–IL-18 axis in the PBMCs of BP patients is correlated positively with disease activity. NLRP3-inflammasome components contribute to BP pathogenesis, so targeting these components may provide a novel therapy for BP. Fang et al. also showed that levels of lactate dehydrogenase and high-mobility group-1 protein were increased in the blister fluid of BP patients, so they could also be considered as parameters for monitoring BP activity [18,36].

3.5. Hsp 90

Heat shock protein (Hsp)90 is essential for the activity of several signalling molecules involved in cellular inflammatory events. Tukaj et al. showed high expression of Hsp90 in the epidermis of BP patients, and that its expression was paralleled with the serum titre of autoantibodies against the NC16A domain of BP180. Hsp90 can also promote the production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-8 [37–40]. This finding provides novel therapy for fighting BP: Hsp90-inhibitors may play a part in reducing inflammatory infiltrates at dermo–epidermal junctions and reduce the level of autoantibodies against the BMZ.

4. Both-related factors

4.1. Antibody titre

Immunofluorescence and the ELISA have shown that IgG1 and IgG4 are the major IgG subclasses to BP180. In addition, Zhou et al. found that the serum level of IgG1 and IgG4 targeting the NC16A domain of BP180 was correlated closely with BP severity, and Mihai et al. discovered that IgG4 autoantibodies induced Fc-dependent dermal–epidermal separation to a significantly lower extent when compared with IgG1 autoantibodies, and they proved that IgG4 autoantibodies may show a significantly lower pathogenic capacity than IgG1 autoantibodies [10,41].

Usually, the ELISA is employed to measure the circulating level of autoantibodies. Compared with immunoblotting and indirect immunofluorescence, the ELISA shows the best sensitivity for detecting IgG and IgE autoantibodies to the NC16A domain of BP180. The ELISA shows easy handling, automated processing and high throughput compared with other methods. Most importantly, the ELISA can achieve quantitative measurement of antibody levels. Hence, it has a considerable effect on monitoring of disease activity [9,42].

Using the ELISA, the autoantibody titre against BP180 has a close relationship with BP activity, but the autoantibody titre against BP230 is not correlated with BP activity [2]. This finding is supported by a study which showed that serum levels of IgG autoantibodies against BP180 could reflect disease severity [43]. However, the specific mechanism has not been elucidated.

In addition to levels of IgG autoantibodies against BP180, circulating levels of total IgE and BP180-specific IgE are also associated with BP activity. Most studies have reported that circulating levels of total IgE are correlated directly with disease severity in all or a subset of patients with high levels of IgE, and that IgE levels decrease as BP resolves. Levels of IgE autoantibodies against BP180 also have a positive correlation with disease activity [44]. Some studies have demonstrated that BP180-specific IgE autoantibodies may be involved in the formation of bullous skin lesions. That is, the higher the serum levels of IgE autoantibodies against BP180, the greater are the number of urticarial lesions and infiltrating eosinophils. Hence, the level of IgE autoantibodies against BP180 correlates closely with the total score of BPDAI [9,45]. However, van Beek et al. discovered that the anti-BP180NC16A antibodies were associated with the occurrence of erosions and blisters, but not urticarial and erythematous lesions [46]. And Hashimoto et al. proved that neither BP180 nor BP230 IgE ELISAs had a significant association with clinical phenotypes, especially erythematous phenotype. These discoveries were different from other researchers. However, the mechanism needs to be further explored [47].

Kalowska et al. found that, using the ELISA, BP patients with IgG and IgE autoantibodies against the NC16A domain of BP180 presented much more extensive skin involvement than patients with only IgG autoantibodies against the NC16A domain of BP180. This finding demonstrated that IgE autoantibodies together with IgG autoantibodies against the NC16A domain represented a more severe clinical picture of BP than that of only IgG autoantibodies against the NC16A domain of BP180 [48]. Besides, IgG and IgE autoantibodies against BP180 can induce different clinical manifestations. Hence, timely detection of these two classes of antibodies could help the evaluation of treatment efficacy in relation to individual symptoms [49].

However, Liu et al. found that at the very early stage of BP, the level of IgE autoantibodies against the NC16A domain of BP180 may not be very high in serum or blister fluid. They concluded that the level of IgE or IgE autoantibodies against the NC16A domain of BP180 could not reflect severity in the first 1–2 months after BP onset. Their finding was different from that of other scholars, and larger studies are needed to clarify this issue [50].

Omalizumab is a humanized monoclonal anti-IgE antibody. Originally, it was designed to control the symptoms of persistent, severe asthma. However, some studies have shown that omalizumab is also effective for BP patients with IgE autoantibodies, as it can inhibit the binding of IgE to FcεRI on the surface of mast cells and basophils [6]. Also, the ELISA for IgE detection is helpful for selecting patients sensitive to omalizumab [3,9]. In addition, omalizumab decreases the activation and degranulation of mast cells, and reduces the number of eosinophils in peripheral blood. Dufour et al. found that omalizumab treatment could result in a decrease in the number of bullae and urticarial lesions of BP patients, and that a 5-month-old boy suffering from BP achieved overall disease control by day-25 of omalizumab treatment [9].

4.2. Individual inflammatory molecules

IL-17 has been implicated as a major pathogenic factor in chronic inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease and several skin diseases such as psoriasis or hidradenitis [51–53]. It also plays a crucial part in the inflammatory process of BP because it can induce expression of MMP-9 and neutrophil elastase (which are involved in blister formation and extension of BP). IL-17 plays an essential part in activating and recruiting eosinophils and neutrophils. It is also involved in the production of cytokines such as TNF-α, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8, which play an active part in the recruitment of inflammatory cells, and lead to degradation of the extracellular matrix at lesion sites. IL-17 can be measured in the skin lesions and serum of patients, and can be regarded as a marker of disease activity [54]. A phase 2 pilot study carried out by Simon et al. showed that mepolizumab, an anti‐IL‐5 antibody, making an effect in reducing the number and activity of peripheral blood eosinophils in patients with active BP. However, it did not significantly affect tissue eosinophil infiltration, and the therapeutic effects were not obvious [55]. Novel therapies need to be further explored, targeting IL-17 could be a therapeutic option for BP in the future [56].

Similar to IL-17, IL-23 also plays an important part in the inflammatory process by increasing secretion of MMP-9 (one of the major proteases involved in blister formation). Both serum levels of IL-17 and IL-23 also correlate with BP severity [51].

5. Epilogue

The severity of BP is associated with clinical manifestations, the number of eosinophils and mast cells, and the concentration of their secreted proteins, also the level of prothrombotic markers F1 + 2 and D-dimer. The activity of BP is correlated to the expression of pro-inflammatory molecules (e.g. IL-6, IL-8, IFN-γ and TNF-α), chemokines such as CCL11 and CCL26, NLRP3-inflammasome components and Hsp90 level. The serum titre of IgG and IgE autoantibodies against BP180 and individual inflammatory molecules such as IL-17 and IL-23 can reflect both the severity and activity of BP (Table 1).

Table 1.

Factors positively correlated with the activity and severity of BP.

| Severity-relative factors |

| Clinical manifestation – BPDAI score |

| Eosinophils’ secreted proteins like Eosinophil Derived Neurotoxin (EDN) and Eosinophil Cationic Protein (ECP) |

| Mast cells’ secreted tryptase level |

| Prothrombotic markers F1 + 2 and D-dimer |

| Activity-relative factors |

| Inflammatory molecules |

| IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-15, CD-30, IL-18, IL-21, IL-31, IL-36, IFN-γ, IL-1β, TNF-α, eotaxin-1(CCL11), CCL22, eotaxin-3 (CCL26), CCR3 and CD23 |

| NLRP3 inflammasome Components ( NLRP3, pro-caspase-1, and pro-IL-18), caspase-1 and apoptosis-associated speck-like protein caspase recruitment domain (ASC) |

| Eotaxin, vascular endothelial growth factor, E-selectin and Hsp90, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and high-mobility group-1 (HMGB1) protein |

| Both-relative factors |

| Antibody titer – Anti-BP180 NC16A IgG and IgE antibodies |

| IL-17 and IL-23 |

BP severity can be evaluated using the BPDAI score, which provides guidance for the selection of appropriate therapies. Further developments should focus on automatization and novel technologies for detecting antibodies against additional target antigens.

Some of the factors identified so far have associations with the activity and severity of BP. Knowledge about these related factors can be incorporated into clinical practice to achieve early intervention. Further research should be undertaken to establish their roles. Cytokines could act as drug targets for therapy. Deeper study on the signalling pathways of these pro-inflammatory molecules could promote the development of novel therapeutic regimens, such as biologic agents.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Programme of China Grant No. 2016YFC0901500, National Natural Science Foundation of China (81972945) and Milstein Medical Asian American Partnership Foundation and Education Reform Projects of Peking Union Medical College [2016zlgc0106].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.Iwata H, Ujiie H. Complement-independent blistering mechanisms in bullous pemphigoid. Exp Dermatol. 2017;26(12):1235–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao CY, Murrell DF. Outcome measures for autoimmune blistering diseases. J Dermatol. 2015;42(1):31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hashimoto T. Induced autoimmune bullous diseases. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(2):304–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamagami J. Reorganization of serum analysis tools for the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180(5):980–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagci IS, Horvath ON, Ruzicka T, et al. Bullous pemphigoid. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16(5):445–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang H, Zhang Y, Li N, et al. The autoimmune skin disease bullous pemphigoid: the role of mast cells in autoantibody-induced tissue injury. Front Immunol. 2018;9:407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ludwig RJ. Bullous pemphigoid: more than one disease? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(3):459–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daneshpazhooh M, Ghiasi M, Lajevardi V, et al. BPDAI and ABSIS correlate with serum anti-BP180 NC16A IgG but not with anti-BP230 IgG in patients with bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018;310(3):255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dufour C, Souillet AL, Chaneliere C, et al. Successful management of severe infant bullous pemphigoid with omalizumab. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(5):1140–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou XP, Liu B, Xu Q, et al. Serum levels of immunoglobulins G1 and G4 targeting the non-collagenous 16A domain of BP180 reflect bullous pemphigoid activity and predict bad prognosis. J Dermatol. 2016;43(2):141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clape A, Muller C, Gatouillat G, et al. Mucosal involvement in bullous pemphigoid is mostly associated with disease severity and to absence of anti-BP230 autoantibody. Front Immunol. 2018;9:479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amber KT, Valdebran M, Kridin K, et al. The role of eosinophils in bullous pemphigoid: a developing model of eosinophil pathogenicity in mucocutaneous disease. Front Med. 2018;5:201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giusti D, Gatouillat G, Le Jan S, et al. Eosinophil Cationic Protein (ECP), a predictive marker of bullous pemphigoid severity and outcome. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):4833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Messingham KN, Holahan HM, Frydman AS, et al. Human eosinophils express the high affinity IgE receptor, FcepsilonRI, in bullous pemphigoid. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castells MC, Irani AM, Schwartz LB. Evaluation of human peripheral blood leukocytes for mast cell tryptase. J Immunol. 1987;138(7):2184–2189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D’Auria L, Pietravalle M, Cordiali-Fei P, et al. Increased tryptase and myeloperoxidase levels in blister fluids of patients with bullous pemphigoid: correlations with cytokines, adhesion molecules and anti-basement membrane zone antibodies. Exp Dermatol. 2000;9(2):131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tedeschi A, Marzano AV, Lorini M, et al. Eosinophil cationic protein levels parallel coagulation activation in the blister fluid of patients with bullous pemphigoid. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(4):813–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang H, Shao S, Cao T, et al. Increased expression of NLRP3 inflammasome components and interleukin-18 in patients with bullous pemphigoid. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;83(2):116–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Auria L, Cordiali Fei P, Ameglio F. Cytokines and bullous pemphigoid. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1999;10(2):123–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ameglio F, D’Auria L, Bonifati C, et al. Cytokine pattern in blister fluid and serum of patients with bullous pemphigoid: relationships with disease intensity. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138(4):611–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyamoto D, Santi CG, Aoki V, et al. Bullous pemphigoid. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94(2):133–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Graauw E, Sitaru C, Horn M, et al. Evidence for a role of eosinophils in blister formation in bullous pemphigoid. Allergy. 2017;72(7):1105–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giusti D, Le Jan S, Gatouillat G, et al. Biomarkers related to bullous pemphigoid activity and outcome. Exp Dermatol. 2017;26(12):1240–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibbs BF, Patsinakidis N, Raap U. Role of the pruritic cytokine IL-31 in autoimmune skin diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonciani D, Quintarelli L, Del Bianco E, et al. Serum levels and tissue expression of interleukin-31 in dermatitis herpetiformis and bullous pemphigoid. J Dermatol Sci. 2017;87(2):210–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salz M, Haeberle S, Hoffmann J, et al. Elevated IL-31 serum levels in bullous pemphigoid patients correlate with eosinophil numbers and are associated with BP180-IgE. J Dermatol Sci. 2017;87(3):309–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeidler C, Pereira MP, Huet F, et al. Pruritus in autoimmune and inflammatory dermatoses. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kasperkiewicz M, Zillikens D, Schmidt E. Pemphigoid diseases: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Autoimmunity. 2012;45(1):55–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zebrowska A, Wozniacka A, Juczynska K, et al. Correlation between IL36alpha and IL17 and activity of the disease in selected autoimmune blistering diseases. Mediat Inflamm. 2017;2017:8980534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kagami S, Kai H, Kakinuma T, et al. High levels of CCL26 in blister fluid and sera of patients with bullous pemphigoid. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(1):249–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gunther C, Wozel G, Meurer M, et al. Up-regulation of CCL11 and CCL26 is associated with activated eosinophils in bullous pemphigoid. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;166(2):145–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu LY, Jarjour NN, Busse WW, et al. Chemokine receptor expression on human eosinophils from peripheral blood and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid after segmental antigen challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112(3):556–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee J, Werth VP, Hall RP, et al. Perspective from the 5th international pemphigus and pemphigoid foundation scientific conference. Front Med. 2018;5:306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inaoki M, Sato S, Takehara K. Elevated expression of CD23 on peripheral blood B lymphocytes from patients with bullous pemphigoid: correlation with increased serum IgE. J Dermatol Sci. 2004;35(1):53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maekawa N, Hosokawa H, Soh H, et al. Serum levels of soluble CD23 in patients with bullous pemphigoid. J Dermatol. 1995;22(5):310–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dinarello CA. The IL-1 family and inflammatory diseases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20(27):S1–S13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tukaj S, Zillikens D, Kasperkiewicz M. Heat shock protein 90: a pathophysiological factor and novel treatment target in autoimmune bullous skin diseases. Exp Dermatol. 2015;24(8):567–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taipale M, Jarosz DF, Lindquist S. HSP90 at the hub of protein homeostasis: emerging mechanistic insights. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(7):515–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tukaj S, Kleszczyński K, Vafia K, et al. Aberrant expression and secretion of heat shock protein 90 in patients with bullous pemphigoid. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e70496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henderson B, Kaiser F. Do reciprocal interactions between cell stress proteins and cytokines create a new intra-/extra-cellular signalling nexus? Cell Stress Chaperones. 2013;18(6):685–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mihai S, Chiriac MT, Herrero-Gonzalez JE, et al. IgG4 autoantibodies induce dermal-epidermal separation. J Cellular Mol Med. 2007;11(5):1117–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saschenbrecker S, Karl I, Komorowski L, et al. Serological diagnosis of autoimmune bullous skin diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chanprapaph K, Ounsakul V, Pruettivorawongse D, et al. Anti-BP180 and anti-BP230 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for diagnosis and disease activity tracking of bullous pemphigoid: a prospective cohort study. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. [cited 2019 Jun 4]. DOI:10.12932/AP-231118-0446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Messingham KN, Crowe TP, Fairley JA. The intersection of IgE autoantibodies and eosinophilia in the pathogenesis of bullous pemphigoid. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cho YT, Liao SL, Wang LF, et al. High serum anti-BP180 IgE levels correlate to prominent urticarial lesions in patients with bullous pemphigoid. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;83(1):78–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Beek N, Luttmann N, Huebner F, et al. Correlation of serum levels of IgE autoantibodies against BP180 with bullous pemphigoid disease activity. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(1):30–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hashimoto T, Ohzono A, Teye K, et al. Detection of IgE autoantibodies to BP180 and BP230 and their relationship to clinical features in bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(1):141–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kalowska M, Ciepiela O, Kowalewski C, et al. Enzyme-linked immunoassay index for anti-NC16a IgG and IgE auto-antibodies correlates with severity and activity of bullous pemphigoid. Acta Derm Venerol. 2016;96(2):191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kamiya K, Aoyama Y, Noda K, et al. Possible correlation of IgE autoantibody to BP180 with disease activity in bullous pemphigoid. J Dermatol Sci. 2015;78(1):77–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bing L, Xiping Z, Li L, et al. Levels of anti-BP180 NC16A IgE do not correlate with severity of disease in the early stages of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol Res. 2015;307(9):849–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Plee J, Le Jan S, Giustiniani J, et al. Integrating longitudinal serum IL-17 and IL-23 follow-up, along with autoantibodies variation, contributes to predict bullous pemphigoid outcome. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blauvelt A, Chiricozzi A. The immunologic role of IL-17 in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis pathogenesis. Clin Rev Allerg Immunol. 2018;55(3):379–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yao Y, Thomsen SF. The role of interleukin-17 in the pathogenesis of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23(7):pii: 13030/qt8rw2j9zv. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zebrowska A, Wagrowska-Danilewicz M, Danilewicz M, et al. IL-17 expression in dermatitis herpetiformis and bullous pemphigoid. Mediat Inflamm. 2013;2013:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simon D, Yousefi S, Cazzaniga S, et al. Mepolizumab failed to affect bullous pemphigoid: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 2 pilot study. Allergy. 2019;75:669–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Le Jan S, Plee J, Vallerand D, et al. Innate immune cell-produced IL-17 sustains inflammation in bullous pemphigoid. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(12):2908–2917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]