Abstract

Aims

We evaluated the influence of sacubitril/valsartan on the effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibition with empagliflozin in patients with heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction.

Methods and results

The EMPEROR-Reduced trial randomized 3730 patients with heart failure and an ejection fraction ≤40% to placebo or empagliflozin (10 mg/day), in addition to recommended treatment for heart failure, for a median of 16 months. A total of 727 patients (19.5%) received sacubitril/valsartan at baseline. Analysis of the effect of neprilysin inhibition was 1 of 12 pre-specified subgroups. Patients receiving a neprilysin inhibitor were particularly well-treated, as evidenced by lower systolic pressures, heart rates, N-terminal prohormone B-type natriuretic peptide, and greater use of cardiac devices (all P < 0.001) when compared with those not receiving sacubitril/valsartan. Nevertheless, when compared with placebo, empagliflozin reduced the risk of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure in patients receiving or not receiving sacubitril/valsartan [hazard ratio 0.64 (95% CI 0.45–0.89), P = 0.009 and hazard ratio 0.77 (95% CI 0.66–0.90), P = 0.0008, respectively, interaction P = 0.31]. Empagliflozin slowed the rate of decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate by 1.92 ± 0.80 mL/min/1.73 m2/year in patients taking a neprilysin inhibitor (P = 0.016) and by 1.71 ± 0.35 mL/min/1.73 m2/year in patients not taking a neprilysin inhibitor (P < 0.0001), interaction P = 0.81. Combined inhibition of SGLT2 and neprilysin was well-tolerated.

Conclusion

The effects on empagliflozin to reduce the risk of heart failure and renal events are not diminished in intensively treated patients who are receiving sacubitril/valsartan. Combined treatment with both SGLT2 and neprilysin inhibitors can be expected to yield substantial additional benefits.

Keywords: Heart failure, Empagliflozin, Sacubitril/valsartan

Graphical Abstract

See page 681 for the editorial comment on this article (doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa1012)

Introduction

Pharmacological inhibition of both neprilysin and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) has been shown individually to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalization for heart failure in patients with heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction. In the PARADIGM-HF trial, sacubtril/valsartan decreased the risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalization for heart failure by 20% as compared with enalapril.1 In the DAPA-HF and EMPEROR-Reduced trials, SGLT2 inhibition with dapagliflozin or empagliflozin reduced the risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalization for heart failure by 25% as compared with placebo.2 , 3 Modelling analysis has suggested a substantial mitigation of major adverse cardiovascular outcomes when the two pharmacological approaches are combined.4 However, this analysis assumed that the effects of neprilysin and SGLT2 inhibition are additive, i.e. each approach exerts an effect that is neither potentiated nor attenuated by concurrent treatment with the other.

However, it is not yet clear that the benefits of neprilysin and SGLT2 inhibition are truly independent of each other. In the large-scale trial of sacubitril/valsartan, no patients were receiving background therapy with an SGLT2 inhibitor, and conversely, in the large-scale trials of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes, no patients were receiving sacubitril/valsartan. In the DAPA-HF, only 10.7% of the patients with heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction were receiving a neprilysin inhibitor at baseline. As a result, the number of heart failure events in patients receiving sacubitril/valsartan in this trial was sparse, leading to estimates of a treatment effect for most outcome measures that were imprecise.5 Accordingly, additional evidence is needed concerning the potential influence of neprilysin inhibition on the effects of SGLT2 inhibitors; this evidence is important for the formulation of clinical practice guidelines.

As compared with DAPA-HF, the EMPEROR-Reduced trial was enriched for patients with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction (i.e. ejection fraction of 30% or less), and the placebo event rate for the primary endpoint was 40% higher than in DAPA-HF. More importantly, the proportion of patients receiving sacubitril/valsartan at baseline in the EMPEROR-Reduced trial was approximately twice than in DAPA-HF.3 Therefore, as compared with DAPA-HF, the EMPEROR-Reduced trial is well-positioned to quantify the influence of neprilysin inhibition on the effects of SGLT2 inhibitors with a greater degree of precision.

Methods

The EMPEROR-Reduced trial was a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, and event-driven study, whose design has been described previously.3 Ethics approval was obtained at each study site, and all patients provided informed consent to participate in the study; the registration identifier at ClinicalTrials.gov is NCT03057977.

Participants were men or women with chronic heart failure (New York Heart Association [NYHA] functional class II, III, or IV) with a left ventricular ejection fraction ≤40%, who were receiving all appropriate treatments for heart failure, including drugs and cardiac devices, as indicated and as available. We preferentially enrolled patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 30% or less by requiring patients with an ejection fraction >30% to have been hospitalized for heart failure within 12 months or to have markedly increased levels of N-terminal prohormone B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), i.e. ≥1000 or ≥2500 pg/mL in those with an ejection fraction of 31–35% or 36–40%, respectively; these thresholds were doubled in patients with atrial fibrillation.

Patients were randomized double-blind (in a 1:1 ratio) to receive placebo or empagliflozin 10 mg daily, in addition to their usual therapy for heart failure. Following entry into the trial, all appropriate treatments for heart failure or other medical conditions could be initiated or altered at the clinical discretion of the investigator. Patients were periodically assessed at study visits for major outcomes, symptoms, and functional capacity related to heart failure, initiation of new treatments for heart failure (including neprilysin inhibition), vital signs and biomarkers reflecting changes in the course of heart failure or the action of SGLT2 inhibitors, and adverse events. All randomized patients were followed for the occurrence of pre-specified outcomes for the entire duration of the trial, regardless of whether the study participants were taking their study medications.

The primary endpoint was the composite of adjudicated cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure analysed as time to first event. The first secondary endpoint was the occurrence of all adjudicated hospitalizations for heart failure (including first and recurrent events). The second secondary endpoint was the analysis of the slope of the change in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) during double-blind treatment, which was supported by an analysis of a composite of serious adverse renal outcomes. The latter was defined as chronic dialysis, renal transplant, a sustained reduction of ≥40% eGFR, or a sustained eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73m2 (for patients with baseline estimated GFR ≥30) or sustained eGFR <10 mL/min/1.73m2 (for patients with baseline estimated GFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2). Additional analyses included (i) the individual components of the primary endpoint; (ii) analyses of the intensity of treatment received during hospitalizations for heart failure, as reported recently6; (iii) changes in the NYHA functional class and the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) at 52 weeks; (iv) changes in haematocrit, uric acid, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), NT-proBNP, body weight, and systolic blood pressure.

Outcome measures and statistical analysis

For time-to-first-event analyses, differences between the placebo and empagliflozin groups were assessed for statistical significance using a Cox proportional hazards model, with pre-specified covariates of age, gender, geographical region, diabetes status at baseline, left ventricular ejection fraction, and eGFR at baseline. For the analysis of total (first and repeated) events, between-group differences were assessed using a joint frailty model, with cardiovascular death (for endpoints including heart failure events) as a competing risk and using covariates that were used for the time-to-first-event analyses. To assess differences between the patients taking and not taking neprilysin inhibitors at baseline, time-to-event and joint frailty analyses were performed on placebo patients only, using the same covariate adjustments.

The analysis of the slope in eGFR was based on on-treatment data using a random coefficient model including age and baseline eGFR as linear covariates and sex, region, baseline left ventricular ejection fraction, baseline diabetes status, and baseline eGFR-by-time, treatment-by-baseline-use-of-neprilysin-inhibition, and treatment-by-time-by-baseline-use-of-neprilysin-inhibition interactions as fixed effects; the model allows for randomly varying slope and intercept between patients. To assess differences between the patients taking and not taking neprilysin inhibitors at baseline, the same model was used on placebo patients only, but using baseline eGFR-by-time and baseline use of neprilysin inhibitor-by-time as the interaction terms.

For vital signs and laboratory measurements, treatment effects were assessed based on changes from baseline to 52 weeks using a mixed model for repeated measures that included age and baseline eGFR as linear covariates and baseline score by visit, visit by treatment, sex, region, baseline left ventricular ejection fraction, individual last projected visit based on dates of randomization and trial closure, and baseline diabetes status as fixed effects. The analysis of changes in NT-proBNP was performed on log-transformed data. For all analyses, the effect of empagliflozin was compared in groups defined by the use or non-use of sacubitril/valsartan. Effect size estimates (with 95% CIs or standard errors) were calculated along with between-group and interaction P-values.

Results

Of the 3730 patients who were randomized into the trial, 727 patients (19.5%) were receiving sacubitril/valsartan before the start of double-blind treatment. The baseline characteristics of the patients treated or not treated with a neprilysin inhibitor were similar with respect to age, sex, NYHA functional class, aetiology of heart failure, renal function, history of hospitalizations for heart failure, atrial fibrillation and diabetes, and the use of beta-blockers and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. However, patients treated with a neprilysin inhibitor were more likely to be recruited in North America; had lower systolic pressure, heart rate, and lower levels of NT-proBNP; and were more likely to have received a cardiac device (all P < 0.001). Specifically, patients who were treated with sacubitril/valsartan were more likely to have an implantable cardioverter-defibrillation (48.1% vs. 27.3%) and more likely to have undergone cardiac resynchronization therapy (17.6% vs. 10.5%), each P < 0.0001, Table 1. A large proportion of the total number of patients recruited in the USA and Canada (i.e. 38%) were receiving a neprilysin inhibitor at baseline, as compared with 20% of those recruited in Europe, and 14% of those recruited in Latin America and in Asia.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients taking and not taking a neprilysin inhibitor at baseline

| Patients not taking a neprilysin inhibitor (n = 3003) |

Patients taking a neprilysin inhibitor (n = 727) |

P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 1480) | Empagliflozin (n = 1523) | Placebo (n = 387) | Empagliflozin (n = 340) | ||

| Age (year) | 66.5 ± 11.2 | 67.4 ± 10.7 | 66.2 ± 11.4 | 66.5 ± 11.4 | 0.191 |

| Women—n (%) | 363 (24.5) | 351 (23.0) | 93 (24.0) | 86 (25.3) | 0.632 |

| Race—n (%) | |||||

| White | 1038 (70.1) | 1089 (71.5) | 266 (68.7) | 236 (69.4) | 0.046 |

| Black | 100 (6.8) | 97 (6.4) | 34 (8.8) | 26 (7.6) | |

| Asian | 276 (18.6) | 284 (18.6) | 59 (15.2) | 53 (15.6) | |

| Other or missing | 66 (4.5) | 53 (3.5) | 28 (7.3) | 25 (7.4) | |

| Region—n (%) | |||||

| North America | 126 (8.5) | 138 (9.1) | 87 (22.5) | 74 (21.8) | <0.0001 |

| Latin America | 554 (37.4) | 554 (36.4) | 91 (23.5) | 87 (25.6) | |

| Europe | 527 (35.6) | 550 (36.1) | 150 (38.8) | 126 (37.1) | |

| Asia | 207 (14.0) | 219 (14.4) | 38 (9.8) | 29 (8.5) | |

| Other | 66 (4.5) | 62 (4.1) | 21 (5.4) | 24 (7.1) | |

| NYHA functional classification—n (%) | |||||

| Class II | 1110 (75.0) | 1158 (76.0) | 291 (75.2) | 241 (70.9) | 0.380 |

| Class III | 362 (24.5) | 358 (23.5) | 93 (24.0) | 97 (28.5) | |

| Class IV | 8 (0.5) | 7 (0.5) | 3 (0.8) | 2 (0.6) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.7 ± 5.3 | 27.8 ± 5.4 | 28.2 ± 5.3 | 28.6 ± 5.9 | 0.003 |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 27.3 ± 6.1 | 28.0 ± 5.9 | 26.7 ± 6.0 | 26.7 ± 6.3 | 0.0002 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 122.5 ± 15.4 | 123.4 ± 16.1 | 117.0 ± 14.4 | 118.9 ± 14.4 | <0.0001 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 72.1 ± 11.8 | 71.3 ± 11.9 | 69.4 ± 11.5 | 69.7 ± 10.7 | <0.0001 |

| NT-proBNP (IQR), median, pg/mL | 1954 (1180, 3544) | 1956 (1108, 3612) | 1727 (1027, 3251) | 1570 (955, 2679) | 0.0001 |

| Estimated eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 62.7 ± 21.7 | 61.5 ± 21.7 | 60.4 ± 20.7 | 63.5 ± 21.8 | 0.839 |

| Cardiovascular history—n (%) | |||||

| Prior myocardial infarction | 611 (41.3) | 683 (44.8) | 173 (44.7) | 156 (45.9) | 0.291 |

| Hospitalization for HF within 12 months | 446 (30.1) | 464 (30.5) | 128 (33.1) | 113 (33.2) | 0.136 |

| Atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter | 576 (38.9) | 575 (37.8) | 162 (41.9) | 128 (37.6) | 0.379 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 735 (49.7) | 765 (50.2) | 194 (50.1) | 162 (47.6) | 0.635 |

| Treatment of heart failure | |||||

| Cardiac glycosides | 255 (17.2) | 236 (15.5) | 56 (14.5) | 47 (13.8) | 0.149 |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist | 1064 (71.9) | 1060 (69.6) | 291 (75.2) | 246 (72.4) | 0.093 |

| Beta-blocker | 1403 (94.8) | 1448 (95.1) | 365 (94.3) | 317 (93.2) | 0.222 |

| Implantable cardioverter-defibrillatora | 401 (27.1) | 420 (27.6) | 192 (49.6) | 158 (46.5) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiac resynchronization therapyb | 153 (10.3) | 161 (10.6) | 69 (17.8) | 59 (17.4) | <0.0001 |

P-values refer to the difference between patients treated or not treated with a neprilysin inhibitor, combining patients in the two randomized treatment groups. Plus-minus values are mean ± SD. Patients who self-identified with ≥1 race or with no race were classified as other.

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; LV, left ventricular; NT-proBNP, N-terminal prohormone B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator with or without cardiac resynchronization therapy.

Cardiac resynchronization therapy with or without a defibrillator.

Despite these differences, examining only the patients in the placebo group, patients treated or not treated with a neprilysin inhibitor were similar with respect to (i) the combined risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalization (21.2 vs. 21.0 events per 100 patient-years of follow-up, P = 0.79); (ii) total number of hospitalizations for heart failure (121 events in 387 patients vs. 432 events in 1480 patients, P = 0.67), and the rate of decline in eGFR (−2.2 mL/min/1.73 m2/year vs. –2.3 mL/min/1.73 m2/year, P = 0.99), in the neprilysin inhibitor and the no neprilysin inhibitor groups, respectively. During the course of double-blind treatment, among patients not treated with sacubitril/valsartan, 131 (8.9%) of the patients in the placebo group and 121 (7.9%) of the patients in the empagliflozin group were initiated on therapy with a neprilysin inhibitor following randomization.

Effect on hierarchically ranked endpoints

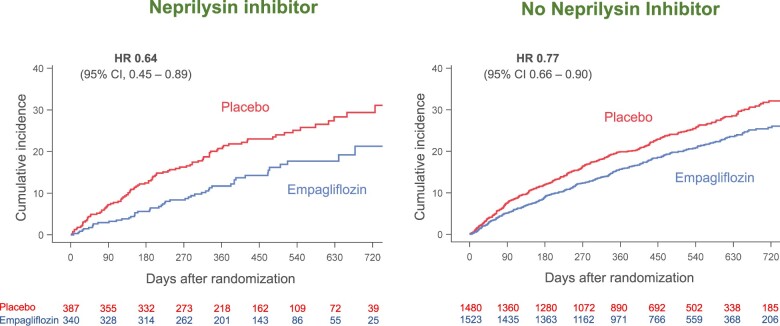

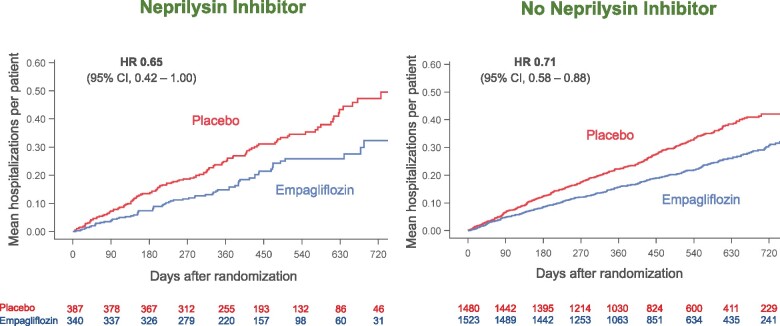

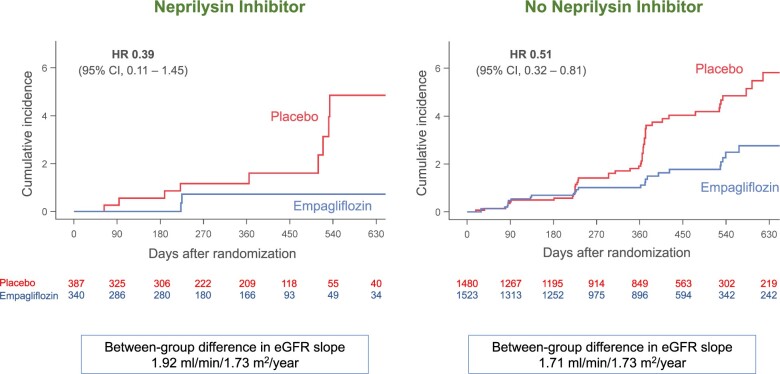

The influence of background therapy with sacubitril/valsartan on the effects of empagliflozin on the three major hierarchically ranked end points is shown in Table 2. When compared with placebo, empagliflozin reduced the combined risk of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure by 23% in the patients not taking a neprilysin inhibitor and by 36% in the patients taking a neprilysin inhibitor, hazard ratios of 0.77 (95% CI 0.66–0.90), P = 0.0008 and 0.64 (95% CI 0.45–0.89), P = 0.009, respectively. Empagliflozin decreased the total number of hospitalization for heart failure by 29% in the patients not taking a neprilysin inhibitor and by 35% in the patients taking a neprilysin inhibitor, hazard ratios of 0.71 (95% CI 0.58–0.88), P = 0.002 and 0.65 (95% CI 0.42–1.00), P = 0.052, respectively, Figure 1. When compared with placebo, empagliflozin slowed the rate of decline in eGFR by 1.71 ± 0.35 mL/min/1.73 m2/year in the patients not taking a neprilysin inhibitor (P < 0.0001) and by 1.92 ± 0.80 mL/min/1.73 m2/year in the patients taking a neprilysin inhibitor (P = 0.016). All treatment-by-subgroup interaction P-values for these analyses were >0.05, Table 2.

Table 2.

Effects of empagliflozin in patients taking and not taking a neprilysin inhibitor at baseline

| Patients not taking a neprilysin inhibitor (n = 3003) |

Patients taking a neprilysin inhibitor (n = 727) |

Interaction P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 1480) | Empagliflozin (n = 1523) | Placebo (n = 387) | Empagliflozin (n = 340) | ||

| Cardiovascular death or adjudicated hospitalization for heart failure [n (%)] | 369 (24.9) | 310 (20.9) | 93 (24.0) | 51 (15.0) | 0.31 |

| HR 0.77 (0.66–0.90) | HR 0.64 (0.45–0.89) | ||||

| P = 0.0008 | P = 0.0094 | ||||

| Total (first and recurrent adjudicated hospitalizations for heart failure) | 432 | 318 | 121 | 70 | 0.72 |

| HR 0.71 (0.58–0.88) | HR 0.65 (0.42–1.00) | ||||

| P = 0.002 | P = 0.052 | ||||

| Slope of decline in eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2/year) (± SE) | –2.3 ± 0.3 | –0.6 ± 0.2 | –2.2 ± 0.5 | –0.2 ± 0.6 | 0.81 |

| +1.71 ± 0.35, P < 0.0001 | +1.92 ± 0.80, P = 0.016 | ||||

| Composite of serious adverse renal outcomes | 49 (3.3) | 27 (1.8) | 9 (2.3) | 3 (0.9) | 0.71 |

| HR 0.51 (0.32–0.81) | HR 0.39 (0.11–1.45) | ||||

| P = 0.005 | P = 0.16 | ||||

| Time-to-first adjudicated hospitalization for heart failure | 266 (18.0) | 206 (13.5) | 76 (19.6) | 40 (11.8) | 0.50 |

| HR 0.71 (0.59–0.85) | HR 0.61 (0.42–0.90) | ||||

| P = 0.0002 | P = 0.013 | ||||

| Time-to-first adjudicated hospitalization for heart failure requiring IV positive inotropic or vasopressor drugs or mechanical or surgical intervention | 132 (8.9) | 118 (7.7) | 42 (10.9) | 16 (4.7) | 0.049 |

| HR 0.84 (0.66–1.08) | HR 0.45 (0.25–0.80) | ||||

| P = 0.18 | P = 0.007 | ||||

| Time-to-first adjudicated hospitalization for heart failure requiring admission to ICU or CCU | 105 (7.1) | 72 (4.7) | 31 (8.0) | 17 (5.0) | 0.95 |

| HR 0.66 (0.49–0.89) | HR 0.64 (0.36–1.17) | ||||

| P = 0.006 | P = 0.15 | ||||

| Cardiovascular death | 167 (11.3) | 166 (10.9) | 35 (9.0) | 21 (6.2) | 0.37 |

| HR 0.95 (0.76–1.18) | HR 0.73 (0.42–1.25) | ||||

| P = 0.63 | P = 0.25 | ||||

| All-cause mortality | 213 (14.4) | 217 (14.2) | 53 (13.7) | 32 (9.4) | 0.25 |

| HR 0.96 (0.79–1.16) | HR 0.73 (0.47–1.13) | ||||

| P = 0.68 | P = 0.15 | ||||

| Time to all-cause mortality, hospitalization for heart failure or emergent or urgent care visit for heart failure | 379 (25.6) | 318 (20.4) | 94 (24.3) | 51 (15.0) | 0.27 |

| HR 0.77 (0.66–0.89) | HR 0.63 (0.44–0.88) | ||||

| P = 0.0006 | P = 0.007 | ||||

| NYHA functional class at 52 weeks | |||||

| Odds ratio for improvement | 1.29 (1.05–1.60), P = 0.02 | 1.39 (0.90–2.14), P = 0.14 | 0.77 | ||

| Odds ratio for worsening | 0.88 (0.71–1.09), P = 0.24 | 0.61 (0.38–0.96), P = 0.03 | 0.15 | ||

| KCCQ clinical summary score at 52 weeks | +1.64 (0.28–3.01) | +1.68 (-1.13–4.49) | 0.98 | ||

| P = 0.018 | P = 0.24 | ||||

Treatment effects are shown as HR and 95% confidence intervals in parentheses, except for eGFR slope (shown as adjusted mean ± SE). For NYHA class, a benefit of empagliflozin is indicated by odds ratios >1.0 for improvement and <1.0 for worsening.

CCU, cardiac care unit; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR, hazard ratios; ICU, intensive care unit; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; IV, intravenous; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SE, standard error.

Figure 1.

Effect of empagliflozin on total (first and recurrent) hospitalizations for heart failure, according to use of neprilysin inhibition at baseline. P-value for the interaction of the effect of empagliflozin and the background use of a neprilysin inhibitor was 0.72. A number of patients at risk at specific time points in each treatment group are displayed below each graph. CI, confidence intervals; HR, hazard ratio. In accordance with usual practice, cumulative function plots were truncated when the number of patients being followed in individual subgroups became extremely sparse.

Effect on other pre-specified heart failure and renal outcomes

With respect to the treatments received during hospitalizations for heart failure, when compared with placebo, empagliflozin reduced the risk of the time to the first hospitalization for heart failure requiring intensive care to a similar degree, hazard ratio of 0.64 (95% CI 0.36–1.17) and 0.66 (95% CI 0.49–0.89), respectively, for the neprilysin inhibitor and no neprilysin inhibitor groups, respectively; interaction P = 0.95. With respect to the time to the first hospitalization for heart failure requiring intravenous positive inotropic or vasopressor drug or mechanical support or surgical intervention, the effect of empagliflozin in patients treated with a neprilysin inhibitor was greater than those not treated with a neprilysin inhibitor; hazard ratio of 0.45 (95% CI 0.25–0.80) and 0.84 (95% CI 0.66–1.08), respectively, for the neprilysin inhibitor and no neprilysin inhibitor groups, respectively; treatment-by-subgroup interaction P = 0.049, Table 2.

For several secondary analyses, the magnitude of the effect of empagliflozin in patients receiving a neprilysin inhibitor was numerically larger than in those not receiving a neprilysin inhibitor, although the interaction P-values were >0.05 (Table 2). When compared with placebo, empagliflozin reduced the risk of cardiovascular death by 5% in the patients not taking a neprilysin inhibitor and by 27% in the patients taking a neprilysin inhibitor, hazard ratios of 0.95 (95% CI 0.76–1.18) and 0.73 (95% CI 0.42–1.25), respectively. Empagliflozin reduced the time to first hospitalization for heart failure by 29% in the patients not taking a neprilysin inhibitor and by 39% in the patients taking a neprilysin inhibitor, hazard ratios of 0.71 (95% CI 0.59–0.85) and 0.61 (95% CI 0.42–0.90), respectively. Empagliflozin reduced the risk of the composite of serious adverse renal outcomes by 49% in the patients not taking a neprilysin inhibitor and by 61% in the patients taking a neprilysin inhibitor, hazard ratios of 0.51 (95% CI 0.32–0.81) and 0.39 (95% CI 0.11–1.45), respectively, Figure 2. The latter analysis was based on only 12 events. For changes in NYHA functional class at 52 weeks, empagliflozin-treated patients had a higher odds of showing improvement, odds ratios of 1.39 (95% CI 0.90–2.14) and 1.29 (95% CI 1.05–1.60) for patients taking or not taking a neprilysin inhibitor, respectively. Similarly, empagliflozin-treated patients had a lower odds of showing worsening of NYHA functional class, odds ratios of 0.61 (95% CI 0.38–0.96) and 0.88 (95% CI 0.71–1.09), for patients taking or not taking a neprilysin inhibitor, respectively. For the KCCQ clinical summary score, the effects of empagliflozin were similar in patients receiving or not receiving a neprilysin inhibitor, Table 2.

Figure 2.

Effect of empagliflozin on composite of serious adverse renal outcomes, according to use of neprilysin inhibition at baseline. P-value for the interaction of the effect of empagliflozin and the background use of a neprilysin inhibitor was 0.71. A number of patients at risk at specific time points in each treatment group are displayed below each graph. Between-group difference in estimated glomerular filtration rate represents a slowing of the decline in renal function in the empagliflozin group. CI, confidence intervals; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR, hazard ratio. In accordance with usual practice, cumulative incidence plots were truncated when the number of patients being followed in individual subgroups became extremely sparse.

Effect on vital signs, biomarkers, and safety

Treatment with a neprilysin inhibitor did not influence the effect of empagliflozin on haemoglobin A1c, uric acid, N-terminal proBNP, or bodyweight, Table 3. As compared with placebo, systolic blood pressure declined by a mean of 1–2 mm Hg shortly during initiation of treatment (at Week 4), and by ∼1 mm Hg after 52 weeks; the magnitude of these decreases was not influenced by background therapy with sacubitril/valsartan (interaction P = 0.59 and P = 0.57, respectively). Additionally, the frequency of reports of adverse events related to hyperkalaemia or hypokalaemia, hypotension, or hypoglycaemia were similar in placebo- or empagliflozin-treated patients and was not influenced by background neprilysin inhibition, Table 4. When analysing treatment-by-neprilysin inhibitor interactions, the use of empagliflozin in neprilysin inhibitor-treated patients was associated with a numerically higher frequency of volume depletion but numerically lower frequency of worsening renal function (as compared with patients receiving empagliflozin but not treated with a neprilysin inhibitor), although the between-group difference generally represented only 10–20 events.

Table 3.

Changes in vital signs and biomarkers at 52 weeks in patients randomized to placebo and empagliflozin, according to baseline use of a neprilysin inhibitor

| Patients not taking a neprilysin inhibitor (n = 3003) |

Patients taking a neprilysin inhibitor (n = 727) |

Interaction P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 1480) | Empagliflozin (n = 1523) | Placebo (n = 387) | Empagliflozin (n = 340) | ||

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | |||||

| At 4 weeks | –1.7 ± 0.3 | –3.0 ± 0.3 | –1.4 ± 0.7 | –3.3 ± 0.7 | 0.59 |

| –1.4 ± 0.5 (P = 0.005) | –1.9 ± 1.0 (P = 0.048) | ||||

| At 52 weeks | –1.8 ± 0.5 | –2.4 ± 0.4 | –0.7 ± 0.9 | –2.1 ± 1.0 | 0.57 |

| –0.6 ± 0.6 (P = 0.38) | –1.4 ± 1.3 (P = 0.29) | ||||

| Bodyweight (kg) | +0.08 ± 0.15 | –0.71 ± 0.14 | +0.06 ± 0.29 | –0.81 ± 0.31 | 0.87 |

| –0.80 ± 0.21 (P = 0.0001) | –0.87 ± 0.42 (P = 0.04) | ||||

| Glycated haemoglobin (%) | –0.12 ± 0.05 | –0.30 ± 0.05 | –0.11 ± 0.09 | –0.21 ± 0.10 | 0.65 |

| –0.18 ± 0.07 (P = 0.0074) | –0.11 ± 0.14 (P = 0.44) | ||||

| Uric acid (mg/mL) | –0.01 ± 0.05 | –0.92 ± 0.05 | –0.18 ± 0.09 | –1.17 ± 0.10 | 0.59 |

| –0.91 ± 0.07 (P < 0.0001) | –0.99 ± 0.14 (P < 0.0001) | ||||

| NT-proBNP (ratio of geometric means) | 0.85 (0.81–0.90) | 0.74 (0.71–0.78) | 0.87 (0.79–0.96) | 0.77 (0.69–0.85) | 0.88 |

| 0.87 (0.81–0.93) P < 0.0001 | 0.88 (0.76–1.02) P = 0.09 | ||||

| Haematocrit (%) | –0.26 ± 0.11 | +2.04 ± 0.11 | –0.86 ± 0.22 | +1.69 ± 0.24 | 0.49 |

| +2.29 ± 0.16, P < 0.0001 | +2.55 ± 0.33, P < 0.0001 | ||||

For all variables except for NT-proBNP, changes are shown as adjusted mean ± standard error. Because of the exceptional non-normal distribution, changes in NT-proBNP are shown as the ratio of geometric means and 95% confidence intervals. Changes in glycated haemoglobin were measured in patients with diabetes, i.e. 735 placebo-treated patients and 765 empagliflozin-treated patients among those not receiving a neprilysin inhibitor at baseline and in 194 placebo-treated patients and 162 empagliflozin-treated patients among those receiving a neprilysin inhibitor at baseline.

NT-proBNP, N-terminal prohormone B-type natriuretic peptide.

Table 4.

Frequency of selected adverse events in placebo and empagliflozin-treated patients, according to baseline use of a neprilysin inhibitor

| Patients not taking a neprilysin inhibitor (n = 2999) |

Patients taking a neprilysin inhibitor (n = 727) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 1476) | Empagliflozin (n = 1523) | Placebo (n = 387) | Empagliflozin (n = 340) | |

| Serious adverse events | 702 (47.6) | 631 (41.4) | 194 (50.1) | 141 (41.5) |

| Hypotension | 124 (8.4) | 132 (8.7) | 39 (10.1) | 44 (12.9) |

| Symptomatic hypotension | 75 (5.1) | 76 (5.0) | 28 (7.2) | 30 (8.8) |

| Volume depletion | 144 (9.8) | 146 (9.6) | 40 (10.3) | 51 (15.0) |

| Hyperkalaemia | 98 (6.6) | 89 (5.8) | 29 (7.5) | 20 (5.9) |

| Hypokalaemia | 24 (1.6) | 30 (2.0) | 5 (1.3) | 5 (1.5) |

| Worsening renal function | 141 (9.6) | 143 (9.4) | 51 (13.2) | 32 (9.4) |

| Acute kidney injury | 38 (2.6) | 25 (1.6) | 17 (4.4) | 10 (2.9) |

| Confirmed hypoglycaemia | 22 (1.5) | 22 (1.4) | 6 (1.6) | 5 (1.5) |

Shown are adverse events while on study medication and recorded up to 7 days following discontinuation of the study medications.

Discussion

Most treatments for chronic heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction have been evaluated in patients who were receiving background treatment with drugs that had been previously shown to reduce morbidity and mortality. The large-scale trials with beta-blockers were carried out in patients already receiving inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system.7–9 Mineralocorticoids were initially found to be effective in a trial that enrolled few patients receiving a beta-blocker,10 but were subsequently shown to exert similar benefits in a population well-treated with inhibitors of the sympathetic nervous system.11 Neprilysin inhibition was shown to reduce morbidity and mortality in patients who were already receiving inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system, beta-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists.1 However, in the first large-scale trial of SGLT2 inhibition in heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction (DAPA-HF), only 10.7% of patients were treated with a neprilysin inhibitor.2 Although the effects of dapagliflozin were numerically similar in patients regardless of treatment with sacubitril/valsartan, there were fewer than 100 primary endpoint events in patients receiving both sacubitril/valsartan and dapagliflozin, leading to estimates that were imprecise. For the analysis of most secondary variables in that trial, the confidence intervals for the effect of dapagliflozin in patients receiving a neprilysin inhibitor were wide, with upper bounds exceeding 1.0.

Although the EMPEROR-Reduced trial was ∼20% smaller than DAPA-HF, we studied patients in whom the incidence of cardiovascular death and hospitalization for heart failure was 40% higher than in DAPA-HF,3 and the proportion of patients receiving a neprilysin inhibitors was approximately twice that in DAPA-HF. As a result, our analyses of the influence of empagliflozin on heart failure events were based on 50% more events than observed in DAPA-HF, thereby affording a greater degree of precision of our estimates. As in DAPA-HF, we found that background therapy with a neprilysin inhibitor did not diminish the treatment benefits of the SGLT2 inhibitor, and in fact, for most endpoints, the magnitude of the effect of empagliflozin in patients receiving sacubitril/valsartan was numerically larger than in those not receiving a neprilysin inhibitor, although the interaction P-values were generally not statistically significant. For all of these reasons, for each of our three major hierarchical endpoints, we were able to demonstrate a significant or near-significant benefit of empagliflozin (P-values ranging from 0.052 to 0.009), even when the analysis of the effect of empagliflozin was confined only to patients receiving sacubitril/valsartan. This was true both for the effect of empagliflozin to reduce the risk of heart failure events as well as the effect of the drug to slow the progression of renal disease.

The ability of empagliflozin to produce both cardiac and renal benefits in patients receiving sacubitril/valsartan is particularly noteworthy since patients receiving the neprilysin inhibitor were exceptionally well-treated with currently recommended drugs and devices. As compared with patients not treated with sacubitril/valsartan, systolic blood pressure and circulating levels of NT-proBNP at baseline were meaningfully lower in patients treated with a neprilysin inhibitor than those who were not; they also had lower heart rates, potentially indicative of the use of higher doses of beta-blockers. The use of cardiac devices was nearly twice as great in patients treated with sacubitril/valsartan than those who were not; nearly 50% of patients treated with a neprilysin inhibitor had an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Yet, despite the greater intensity of background therapy for heart failure, SGLT2 inhibition with empagliflozin exerted favourable effects on heart failure events and on the progression of renal disease that were not attenuated (and were often numerically greater) than those seen in patients not receiving a neprilysin inhibitor. This benefit was achieved with a minimal incremental reduction in systolic blood pressure, either following initiation of therapy or during long-term treatment, and combination treatment was generally well-tolerated.

The lack of an adverse interaction between SGLT2 inhibitors and sacubitril/valsartan reinforces the current belief that these two classes of drugs have distinctly different mechanisms of action. Sacubitril/valsartan potentiates the effects of endogenous vasodilatory peptides that appear to act primarily through increasing levels of intracellular cyclic GMP,12 although other mediators may be involved.13 In contrast, although the mechanism of action of SGLT2 inhibitors has not yet been fully elucidated, these drugs act intracellularly to reduce oxidative stress and mitigate proinflammatory pathways, possibly through an effect to enhance nutrient deprivation signalling.14 , 15 Whereas neprilysin inhibitors exert striking effects to reduce NT-proBNP and may produce symptomatic hypotension during initiation of treatment,16 , 17 SGLT2 inhibitors have only modest effects on circulating natriuretic peptides,18 and initiation of treatment is not generally associated with meaningful decreases in blood pressure. Both neprilysin inhibitors and SGLT2 inhibitors have favourable effects to slow the decline in renal function in patients with heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction,3 , 19 although the magnitude of the effect of SGLT2 inhibitors is larger than that of neprilysin inhibitors, and their use is accompanied by a reduced risk of serious adverse renal outcomes.3 , 20 Conversely, the effect of neprilysin inhibitors to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death is more firmly established than that of SGLT2 inhibitors.1 , 21

The results of the current study should be considered in light of its strengths and limitations. The study evaluated the influence of neprilysin inhibition on the effects of empagliflozin across multiple endpoints, which were analysed based on larger number of treated patients and a greater number of events than the DAPA-HF trial. Yet, the total database with the combined use of SGLT2 inhibitors and neprilysin inhibitors in the EMPEROR-Reduced trial is still smaller than would be seen in a dedicated trial where the use of neprilysin inhibitors was mandated or highly prevalent. Nevertheless, a recent meta-analysis that evaluated the influence of sacubitril/valsartan on the risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalization for heart failure, based on the combined results of the DAPA-HF and EMPEROR-Reduced trials, analysed nearly 250 events observed in 1230 patients who were treated with a neprilysin inhibitor.22 In this meta-analysis, the results across the two trials were highly concordant, with no evidence of heterogeneity. Combining the results takes advantage of the fact that the two trials studied complementary but overlapping groups of patients, which cover the full spectrum of patients with heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction.21 , 22 Nevertheless, these analyses do not provide any insights concerning the effects of neprilysin inhibitors in patients who were receiving background therapy with SGLT2 inhibitors. Examination of this question in a large-scale is not feasible, and given the lack of interaction seen in the meta-analysis, is unlikely to yield results that differ from that of the effects of neprilysin inhibition in the absence of SGLT2 inhibition.

In conclusion, the effects on empagliflozin to favourably affect the clinical course of heart failure and kidney function are not influenced by concurrent therapy with sacubtril/valsartan. Concurrent treatment with both neprilysin and SGLT2 inhibitors is well-tolerated and is expected to yield substantial incremental benefits.4 Efforts should be directed towards developing and implementing strategies that would encourage combined use of both classes of drugs in a broad range of patients with heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction.

Data availability

Data will be made available upon request in adherence with transparency conventions in medical research and through requests to the corresponding author. The executive committee of EMPEROR has developed a comprehensive analysis plan and numerous pre-specified analyses, which will be presented in future scientific meetings and publications. At a later time point, the full database will be made available in adherence with the transparency policy of the sponsor (available at https://trials.boehringer-ingelheim.com/transparency_policy.html).

Funding

Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly and Company.

Conflict of interest: M.P. reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Abbvie, Akcea, Amarin, AstraZeneca, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardiorentis, Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Relypsa, Sanofi, Synthetic Biologics, Theravance, NovoNordisk, outside the submitted work. S.A. reports grants and personal fees from Vifor Int. and Abbott Vascular, and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Brahms, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardiac Dimensions, Novartis, Occlutech, Servier, and Vifor Int. Personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim during the conduct of the study. J.B. reports consulting fees from BI, Cardior, CVRx, Foundry, G3 Pharma, Imbria, Impulse Dynamics, Innolife, Janssen, LivaNova, Luitpold, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, NovoNordisk, Relypsa, Roche, Sanofi, Sequana Medical, V-Wave Ltd, and Vifor. Personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim during the conduct of the study. G.F. reports Committee Member contributions in trials. Personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim during the conduct of the study. J.P.F. is a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim. S.P. is a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim. Personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim during the conduct of the study. H.-P.B.-L.R. reports grants and personal fees from Novartis, Roche Diagnostics, Vifor, and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, outside the submitted work. Personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim during the conduct of the study. S.J. reports grants from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Bayer, and Daiichi Sankyo outside the submitted work, including personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim during the conduct of the study. The University of Leuven is reimbursed for time spent on advisory boards for Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, and Regeneron. H.T. reports receiving grants from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Japan Ltd, Japan Tobacco Inc., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, IQVIA Services Japan, Omron Healthcare, Teijin Pharma Ltd, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co Ltd, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Bayer Yakuhin Ltd, Kowa Pharmaceutical Co Ltd, Teijin Pharma Ltd, Ono Pharmaceutical Co Ltd, AstraZeneca K.K., grants and personal fees from Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co Ltd, Daiichi Sankyo Co Ltd, Astellas Pharma Inc, Novartis Pharma K.K., Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, MSD K.K. Pfizer Japan Inc outside the submitted work. Personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim during the conduct of the study. J.Z. reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, during the conduct of the study. M.B., W.J., D.C., T.I., and J.S. are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim. F.Z. has received steering committee or advisory board fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Cardior, CVRx, Janssen, Livanova, Merck, Mundipharma, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Vifor Fresenius. Personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim during the conduct of the study.

Contributor Information

Milton Packer, Baylor Heart and Vascular Institute, Baylor University Medical Center, 621 N. Hall Street, Dallas, TX, USA; Imperial College, London, UK.

Stefan D Anker, Department of Cardiology (CVK), and Berlin Institute of Health Center for Regenerative Therapies, German Centre for Cardiovascular Research Partner Site Berlin, Charité Universitätsmedizin, Berlin, Germany.

Javed Butler, Department of Medicine, University of Mississippi School of Medicine, Jackson, MS, USA.

Gerasimos Filippatos, National and Kapodistrian, University of Athens School of Medicine, Athens University Hospital Attikon, Athens, Greece.

Joao Pedro Ferreira, Université de Lorraine, Inserm INI-CRCT, CHRU, Nancy, France.

Stuart J Pocock, Department of Medical Statistics, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK.

Hans-Peter Brunner-La Rocca, Department of Cardiology, Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Stefan Janssens, Department of Cardiology, University Hospital Gasthuisberg of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium.

Hiroyuki Tsutsui, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Kyushu University, Higashi-ku, Fukuoka, Japan.

Jian Zhang, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, People’s Republic of China.

Martina Brueckmann, Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH and Faculty of Medicine Mannheim, University of Heidelberg, Mannheim, Germany.

Waheed Jamal, Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH, Ingelheim, Germany.

Daniel Cotton, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Ridgefield, CT, USA.

Tomoko Iwata, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co. KG, Biberach, Germany.

Janet Schnee, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Ridgefield, CT, USA.

Faiez Zannad, Université de Lorraine, Inserm INI-CRCT, CHRU, Nancy, France.

References

- 1. McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau JL, Shi VC, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile MR, PARADIGM-HF Investigators and Committees. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014;371:993–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Martinez FA, Ponikowski P, Sabatine MS, Anand IS, Bělohlávek J, Böhm M, Chiang C-E, Chopra VK, de Boer RA, Desai AS, Diez M, Drozdz J, Dukát A, Ge J, Howlett JG, Katova T, Kitakaze M, Ljungman CEA, Merkely B, Nicolau JC, O’Meara E, Petrie MC, Vinh PN, Schou M, Tereshchenko S, Verma S, Held C, DeMets DL, Docherty KF, Jhund PS, Bengtsson O, Sjöstrand M, Langkilde A-M; DAPA-HF Trial Committees and Investigators. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1995–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Pocock SJ, Carson P, Januzzi J, Verma S, Tsutsui H, Brueckmann M, Jamal W, Kimura K, Schnee J, Zeller C, Cotton D, Bocchi E, Böhm M, Choi DJ, Chopra V, Chuquiure E, Giannetti N, Janssens S, Zhang J, Gonzalez Juanatey JR, Kaul S, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Merkely B, Nicholls SJ, Perrone S, Pina I, Ponikowski P, Sattar N, Senni M, Seronde MF, Spinar J, Squire I, Taddei S, Wanner C, Zannad F, EMPEROR-Reduced Trial Investigators. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1413–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, Jhund PS, Cunningham JW, Pedro Ferreira J, Zannad F, Packer M, Fonarow GC, McMurray JJV, Solomon SD. Estimating lifetime benefits of comprehensive disease-modifying pharmacological therapies in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a comparative analysis of three randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2020;396:121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Solomon SD, Jhund PS, Claggett BL, Dewan P, Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Martinez FA, Ponikowski P, Sabatine MS, Inzucchi SE, Desai AS, Bengtsson O, Lindholm D, Sjostrand M, Langkilde AM, McMurray JJV. Effect of dapagliflozin in patients with HFrEF treated with sacubitril/valsartan: the DAPA-HF trial. JACC Heart Fail 2020;8:811–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Ferreira JP, Pocock SJ, Carson P, Anand I, Doehner W, Haass M, Komajda M, Miller A, Pehrson S, Teerlink JR, Brueckmann M, Jamal W, Zeller C, Schnaidt S, Zannad F, for the EMPEROR-Reduced Trial Committees and Investigators. Effect of empagliflozin on the clinical stability of patients with heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction: the emperor-reduced trial. Circulation 2020; doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.051783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7. Packer M, Coats AJS, Fowler MB, Katus HA, Krum H, Mohacsi P, Rouleau JL, Tendera M, Castaigne A, Roecker EB, Schultz MK, Staiger C, Curtin EL, DeMets DL, Carvedilol Prospective Randomized Cumulative Survival Study Group. Effect of carvedilol on survival in severe chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1651–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MERIT-HF Investigators. Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure: Metoprolol CR/XL Randomised Intervention Trial in Congestive Heart Failure (MERIT-HF). Lancet 1999;353:2001–2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CIBIS II Investigators. The Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study II (CIBIS-II): a randomised trial. Lancet 1999;353:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, Cody R, Castaigne A, Perez A, Palensky J, Wittes J. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 1999;341:709–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zannad F, McMurray JJ, Krum H, van Veldhuisen DJ, Swedberg K, Shi H, Vincent J, Pocock SJ, Pitt B, Emphasis HF, Study G. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med 2011;364:11–21.21073363 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Packer M, McMurray JJV. Importance of endogenous compensatory vasoactive peptides in broadening the effects of inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system for the treatment of heart failure. Lancet 2017;389:1831–1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tam K, Richards DA, Aronovitz MJ, Martin GL, Pande S, Jaffe IZ, Blanton RM. Sacubitril/valsartan improves left ventricular function in chronic pressure overload independent of intact cyclic guanosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase I alpha signaling. J Card Fail 2020;26:769–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Packer M. Role of deranged energy deprivation signaling in the pathogenesis of cardiac and renal disease in states of perceived nutrient overabundance. Circulation 2020;141:2095–2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Packer M. Role of impaired nutrient and oxygen deprivation signaling and deficient autophagic flux in the development of diabetic chronic kidney disease: implications for understanding the effects of metformin and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors. J Am Soc Nephrol 2020;31:907–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Packer M, McMurray JJ, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau JL, Shi VC, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile M, Andersen K, Arango JL, Arnold JM, Bělohlávek J, Böhm M, Boytsov S, Burgess LJ, Cabrera W, Calvo C, Chen CH, Dukat A, Duarte YC, Erglis A, Fu M, Gomez E, Gonzàlez-Medina A, Hagège AA, Huang J, Katova T, Kiatchoosakun S, Kim KS, Kozan Ö, Llamas EB, Martinez F, Merkely B, Mendoza I, Mosterd A, Negrusz-Kawecka M, Peuhkurinen K, Ramires FJ, Refsgaard J, Rosenthal A, Senni M, Sibulo AS Jr, Silva-Cardoso J, Squire IB, Starling RC, Teerlink JR, Vanhaecke J, Vinereanu D, Wong RC, Paradigm-HF Investigators and Coordinators. Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibition compared with enalapril on the risk of clinical progression in surviving patients with heart failure. Circulation 2015;131:54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Senni M, McMurray JJ, Wachter R, McIntyre HF, Reyes A, Majercak I, Andreka P, Shehova-Yankova N, Anand I, Yilmaz MB, Gogia H, Martinez-Selles M, Fischer S, Zilahi Z, Cosmi F, Gelev V, Galve E, Gómez-Doblas JJ, Nociar J, Radomska M, Sokolova B, Volterrani M, Sarkar A, Reimund B, Chen F, Charney A. Initiating sacubitril/valsartan (LCZ696) in heart failure: results of TITRATION, a double-blind, randomized comparison of two uptitration regimens. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:1193–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nassif ME, Windsor SL, Tang F, Khariton Y, Husain M, Inzucchi SE, McGuire DK, Pitt B, Scirica BM, Austin B, Drazner MH, Fong MW, Givertz MM, Gordon RA, Jermyn R, Katz SD, Lamba S, Lanfear DE, LaRue SJ, Lindenfeld J, Malone M, Margulies K, Mentz RJ, Mutharasan RK, Pursley M, Umpierrez G, Kosiborod M, Malik AO, Wenger N, Ogunniyi M, Vellanki P, Murphy B, Newman J, Hartupee J, Gupta C, Goldsmith M, Baweja P, Montero M, Gottlieb SS, Costanzo MR, Hoang T, Warnock A, Allen L, Tang W, Chen HH, Cox JM, On behalf of the DEFINE-HF Investigators. Dapagliflozin effects on biomarkers, symptoms, and functional status in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the DEFINE-HF trial. Circulation 2019;140:1463–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Damman K, Gori M, Claggett B, Jhund PS, Senni M, Lefkowitz MP, Prescott MF, Shi VC, Rouleau JL, Swedberg K, Zile MR, Packer M, Desai AS, Solomon SD, McMurray JJV. Renal effects and associated outcomes during angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition in heart failure. JACC Heart Fail 2018;6:489–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter R, Chertow GM, Greene T, Hou FF, Mann JFE, McMurray JJV, Lindberg M, Rossing P, Sjöström CD, Toto RD, Langkilde AM, Wheeler DC, DAPA-CKD Trial Committees and Investigators. Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1436–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Butler J, Zannad F, Filippatos G, Anker SD, Packer M. Totality of evidence in trials of sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors in the patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: implications for clinical practice. Eur Heart J 2020;41:3398–3401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zannad F, Ferreira JP, Pocock SJ, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Brueckmann M, Ofstad AP, Pfarr E, Jamal W, Packer M. SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a meta-analysis of the EMPEROR-Reduced and DAPA-HF trials. Lancet 2020;396:819–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request in adherence with transparency conventions in medical research and through requests to the corresponding author. The executive committee of EMPEROR has developed a comprehensive analysis plan and numerous pre-specified analyses, which will be presented in future scientific meetings and publications. At a later time point, the full database will be made available in adherence with the transparency policy of the sponsor (available at https://trials.boehringer-ingelheim.com/transparency_policy.html).