Abstract

Cocaine, an alkaloid, is an addictive drug and its abuse as a recreational drug is on the increasing side with its associated complications. Gastrointestinal complications, after cocaine abuse, are less known and need to be addressed since the abuse is on the rise and the existing evidence is scarce. We report a case of a 22-year-old male patient who presented with abdominal pain following a cocaine injection. On examination, signs of peritonitis were noted and laparotomy revealed a 2×1 cm perforation in the distal ileum. The unhealthy intestinal segment was resected and taken out as a double-barrel ileostomy. The patient had an episode of severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding on postoperative day 6. CT and colonoscopy revealed signs of ischaemic bowel and tissue biopsy showed oedematous, inflamed and haemorrhagic bowel mucosa. The patient was managed conservatively and is doing well under follow-up in a de-addiction centre.

Keywords: gastrointestinal surgery, drugs misuse (including addiction)

Background

Cocaine is an addictive stimulant drug and its recreational use is illegal. Cocaine is taken orally, intranasally, intravenously or smoked as crack (the freebase of cocaine). Cocaine and crack abuse are associated with nasal septal perforations and necrosis, cardiac complications like arrhythmia, cardiomyopathy, myocarditis and endocarditis, respiratory problems like pulmonary haemorrhages, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum and non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema (crack lung). Gastrointestinal (GI) complications of cocaine abuse are relatively uncommon and the incidence is not well established owing to the rarity of the GI symptoms. However, limited evidence suggests that cocaine abuse can cause mesenteric ischaemia and gangrene leading to bowel perforation.1 We report an unusual case of gastrointestinal perforation with massive GI bleeding associated with cocaine abuse. This case emphasises the need to suspect cocaine abuse in young patients presenting with symptoms and signs of bowel ischaemia in the absence of other predisposing factors.

Case presentation

A 22-year-old male patient came to our surgical emergency ward with a complaint of pain in the right lower abdominal quadrant occurring for 10 days. The pain was accused to start after a cocaine injection and was associated with multiple episodes of vomiting and a single episode of bloody diarrhoea. The patient was a chronic smoker with alcohol and cocaine abuse. He had been smoking cocaine and taking intravenous injections almost every 20 days for the past 6 years and the last dose of cocaine abuse was the night before the symptom onset.

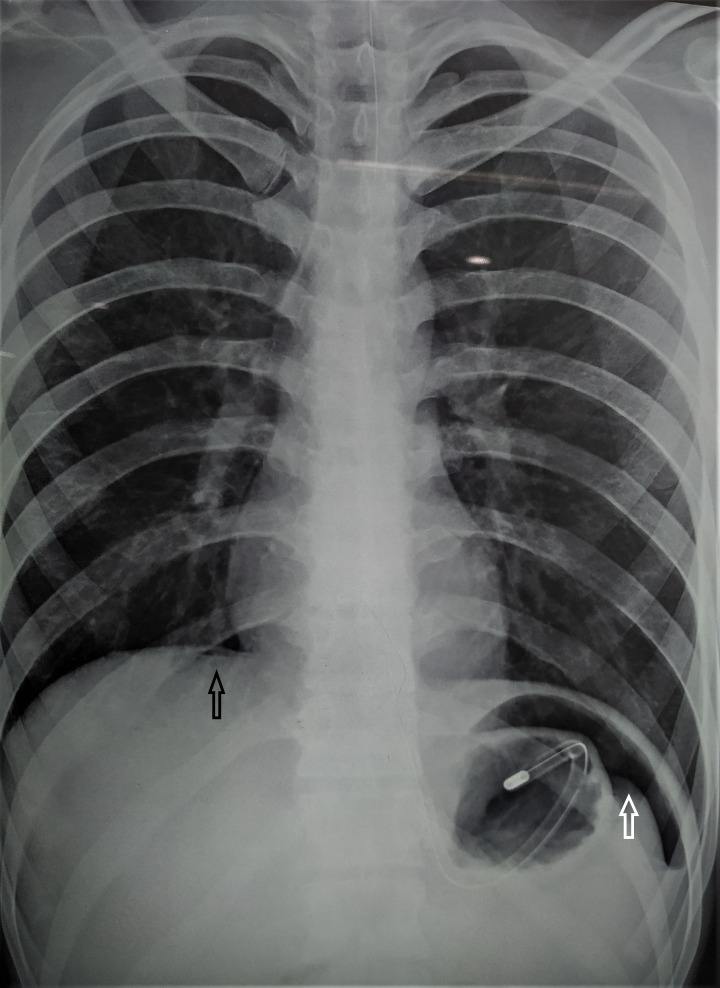

At presentation, the patient was conscious, oriented and haemodynamically stable except for mild tachycardia. On examination, the abdomen was distended with evidence of rebound tenderness and rigidity. Fingers were stained with blood and faeces on digital rectal examination. An abdominal X-ray revealed air under the diaphragm (figure 1). Haematological parameters were within normal range except for leucocytosis.

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray showing air under diaphragm.

Treatment

The patient was planned for emergency laparotomy after adequate resuscitation in the suspect of perforation peritonitis. The laparotomy revealed biliopurulent contamination, and a 2×1 cm perforation was observed in the distal ileum along the antimesenteric margin. Multiple impending perforations were present along 10 cm proximal to the perforated ileum (figures 2 and 3). The unhealthy bowel segment was resected and taken out as a double-barrel ileostomy. On postoperative day 3, the patient was haemodynamically stable and fed orally. Because of substance abuse, psychiatric consultation was taken. On postoperative day 6, a single episode of severe lower GI bleeding was noticed. The patient was pale, with a pulse rate of 110/min, and blood pressure of 100/70 mm Hg; there were no signs of peritonitis and the stomal output was feculent without any evidence of active bleeding. An abdominal contrast-enhanced CT with CT angiography was performed and revealed a normal angiographic pattern with small bowel loops showing circumferential mural thickening distal to the stoma site (figures 4 and 5). A colonoscopy revealed multiple aphthous ulcerations (figure 6), an erythematous mucosa, and submucosal haemorrhages along the terminal ileum and the ascending colon (figures 7 and 8). Tissue biopsy showed oedematous, inflamed and haemorrhagic mucosa with inflammatory cell infiltrate in the lamina propria with the absence of granuloma, vascular thrombi or fibrin formation, and infectious organisms. Echocardiography showed no evidence of endocarditis or cardiomyopathy. The patient was treated conservatively and discharged on oral feeds after 10 days.

Figure 2.

2×2 cm ileal perforation with surrounding unhealthy bowel.

Figure 3.

Cut section of resected bowel segment shows multiple ulcers with unhealthy bowel mucosa with impending perforations.

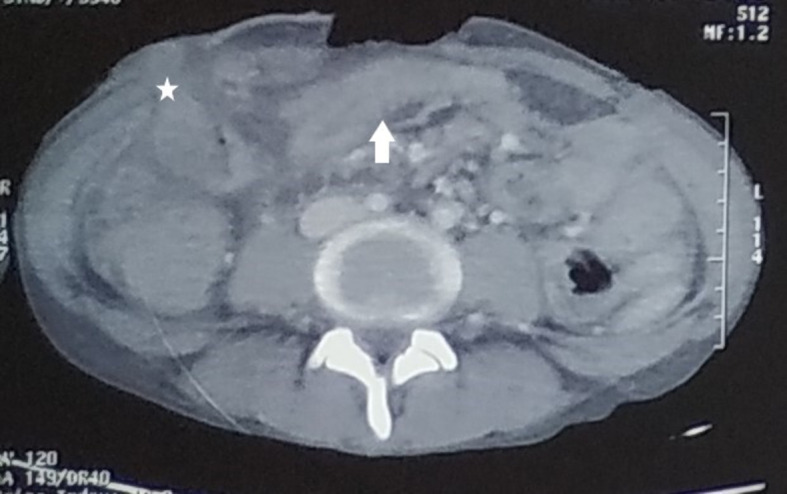

Figure 4.

CT image showing stoma (*) and oedematous distal bowel loops.

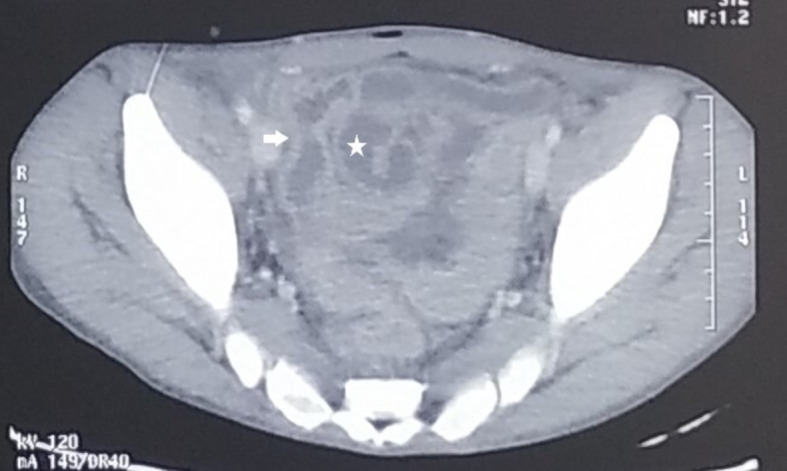

Figure 5.

CT image showing thickened, oedematous and dilated bowel loops (*) characteristic of ischaemic colitis.

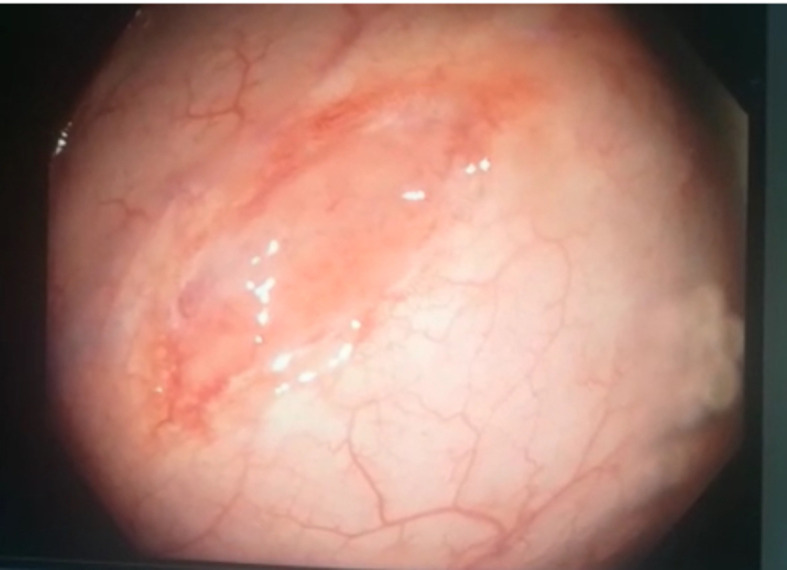

Figure 6.

Colonoscopy image showing an aphthous ulcer.

Figure 7.

Iodocyanine green colonoscopy image of an aphthous ulcer.

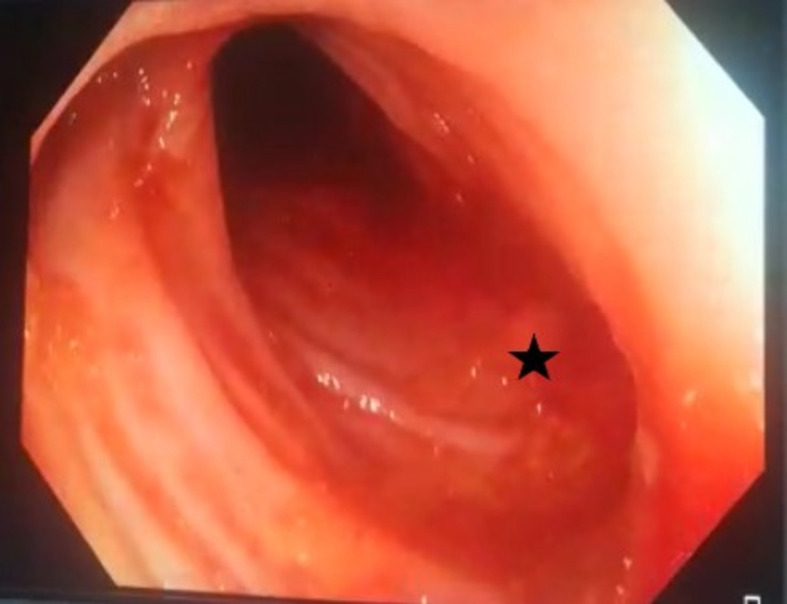

Figure 8.

Oedematous and inflamed colonic mucosa with mucosal irregularity with active ooze from ulcer (*) with areas of submucosal haemorrhage.

Outcome and follow-up

Follow-up was uneventful; the patient denied the stoma reversal when offered 2 months after the emergency surgery. Moreover, the patient was accepting orally, and the stoma was correctly functioning with no recurrence of bleeding. The patient was taken care of in a de-addiction centre with no evidence of cocaine abuse relapse.

Discussion

According to the World Drug Report in 2002, alcohol, cannabis and opioids were the major substances abused in India.2 Cocaine abuse has increased over the past years with an incidence reported at 1.5%. The abuse of cocaine results in serious cardiovascular complications including myocardial infarction, acute aortic dissection, arrhythmias, endocarditis, myocarditis, cardiogenic pulmonary oedema, cerebrovascular accidents, nasal septal perforations/necrosis, respiratory problems including pneumothorax and ‘crack lung’.2 3

GI complications are relatively rare, which include mesenteric ischaemia that can lead to gangrene, intestinal perforation and rarely lower GI bleed. Prepyloric or duodenal perforation are more common. The incidence of cocaine-induced GI complication is not well documented due to their rarity. Any portion of the small bowel can be involved, with the distal ileum being the most commonly reported to date. Crack abuse can cause ischaemic colitis which presents with abdominal pain and bloody diarrhoea.

Including our case, a total of 36 cases of cocaine-induced bowel ischaemia have been reported in the literature.4 Most patients were in their second and third decade of life, and smoking

(‘crack’) was the most common form of cocaine abuse followed by the nasal, intravenous and oral route. Most patients presented within a day of abuse, but the interval varied from 1 hour to 2 days. Abdominal pain is the most common presentation followed by vomiting and rebound tenderness. Imaging characteristics of mesenteric ischaemia include bowel oedema with a typical thickness of 8–9 mm, mucosal enhancement, venous engorgement, mesenteric free fluid and dilatation of the lumen. The most common endoscopic presentation was oedema, diffuse erythema, ulcerations and subepithelial haemorrhages as reported also in our patient. Bowel gangrene is the most common finding in laparotomy followed by perforation and bowel oedema. Histologically, cocaine-associated colitis presents with oedema, congestion, inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria, loss of goblet cells and submucosal haemorrhage which is consistent with our histological findings.4–6

Cocaine causes severe vasoconstriction of the splanchnic circulation, inducing tissue ischaemia and infarction. Cocaine (known as benzoylmethylecgonine) blocks the reuptake of the released norepinephrine in the presynaptic terminal of the splanchnic circulation especially in the α-adrenergic receptors, which are most abundant in the distal ileum and the colon, leading to arterial vasospasm and vasoconstriction resulting in intestinal ischaemia and signs of ischaemic colitis. Cocaine induces platelets to aggregate and to release vasoactive mediators in the splanchnic circulation which causes symptoms like mesenteric angina. Cocaine has also a direct toxic effect on the intestinal mucosa that contributes to intestinal ischaemia.7

The abdominal complications of crack and cocaine abuse differ slightly. Prepyloric or duodenal perforation are the usual consequences of crack abuse. Crack can produce similar effects of acute abdomen encountered with cocaine abuse such as ischaemic colitis presenting as bowel gangrene and perforation, both with similar pathophysiological mechanisms causing vasoconstriction. The possible explanation of upper GI perforation being most commonly associated with abuse of crack is the documented effects on decreasing gastric motility and increasing intragastric pressure due to increased air swallowing and breath-holding.8 9

In our case, cocaine abuse was recreational, and the patient had no predisposing factors for bowel ischaemia except cigarette smoking, which has an additive effect on the vasoconstrictive mechanism of cocaine-induced bowel ischaemia. Our patient had postoperative lower GI bleeding, which is an unusual presentation, with the colonoscopy showing features of diffuse small bowel ischaemia and inflammation from the ileum to the ascending colon. Presentation with lower gastrointestinal bleeding is a rare complication of cocaine abuse. To our knowledge, this patient is the only reported case of cocaine-induced bowel ischaemia, which presented with both ischaemia-induced perforation and colitis, causing lower GI bleeding.10 11

Learning points.

This is a classic case of gastrointestinal complications of cocaine abuse presenting as ischaemic perforation and lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

Due to the increasing abuse of cocaine and crack, it is important to be aware of their associated abdominal complications, such as mesenteric ischaemia and intestinal perforation, in younger and middle-aged patients who access the surgical emergency with an acute abdomen.

Identification of aetiology might help in preventing future episodes of complications and efforts should be made for de-addiction which might help in improving the overall outcome of this specific group of patients.

Footnotes

Contributors: SD took part in conception, design and revision of the study. SI revised the manuscript critically and gave final approval of the version to be published. JS drafted the manuscript and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. YS revised the manuscript critically and ensured the accuracy of the study.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Tiwari A, Moghal M, Meleagros L. Life threatening abdominal complications following cocaine abuse. J R Soc Med 2006;99:51–2. 10.1177/014107680609900203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murthy P, Manjunatha N, Subodh BN, et al. Substance use and addiction research in India. Indian J Psychiatry 2010;52:189–99. 10.4103/0019-5545.69232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bansal R, Sharma M, Aron J. Cocaine gut.. ACG Case Rep J 2019;6:e00041. 10.14309/crj.0000000000000041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nidimusili AJ, Mennella J, Shaheen K. Small intestinal ischemia with pneumatosis in a young adult: what could be the cause? Case Rep Gastrointest Med 2013;2013:462985. 10.1155/2013/462985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angel W, Angel J, Shankar S. Ischemic bowel: uncommon imaging findings in a case of cocaine enteropathy. J Radiol Case Rep 2013;7:38–43. 10.3941/jrcr.v7i2.1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linder JD, Mönkemüller KE, Raijman I, et al. Cocaine-associated ischemic colitis. South Med J 2000;93:909–13. 10.1097/00007611-200009000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Texter EC, CHOU CC, MERRILL SL, et al. Direct effects of vasoactive agents on segmental resistance of the mesenteric and portal circulation. Studies with 1-epinephrine, levarterenol, angiotensin, vasopressin, acetylcholine, methacholine, histamine, and serotonin. J Lab Clin Med 1964;64:624–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feliciano DV, Ojukwu JC, Rozycki GS, et al. The epidemic of cocaine-related juxtapyloric perforations: with a comment on the importance of testing for Helicobacter pylori. Ann Surg 1999;229:801–4. 10.1097/00000658-199906000-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kram HB, Hardin E, Clark SR, et al. Perforated ulcers related to smoking "crack" cocaine. Am Surg 1992;58:293–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaheen K, Alraies MC, Marwany H, et al. Illicit drug, ischemic bowel. Am J Med 2011;124:708–10. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wattoo MA, Osundeko O. Cocaine-Induced intestinal ischemia. West J Med 1999;170:47–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]