Abstract

Background

Patient-centered care (PCC) is a core component of quality care and its measurement is fundamental for research and improvement efforts. However, an inventory of surveys for measuring PCC in hospitals, a core care setting, is not available.

Objective:

To identify surveys for assessing PCC in hospitals, assess PCC dimensions that they capture, report their psychometric properties, and evaluate applicability to individual and/or dyadic (e.g., mother-infant pairs in pregnancy) patients.

Research Design:

We conducted a systematic review of articles published before January 2019 available on PubMed, Web of Science, and EBSCO Host and references of extracted papers to identify surveys used to measure “patient-centered care” or “family-centered care.” Surveys used in hospitals and capturing at least three dimensions of PCC, as articulated by the Picker Institute, were included and reviewed in full. Surveys’ descriptions, subscales, PCC dimensions, psychometric properties, and applicability to individual and dyadic patients were assessed.

Results:

Thirteen of 614 articles met inclusion criteria. Nine surveys were identified, which were designed to obtain assessments from patients/families (n=5), hospital staff (n=2), and both patients/families and hospital staff (n=2). No survey captured all eight Picker dimensions of PCC (median=6 [range 5–7]). Psychometric properties were reported infrequently. All surveys applied to individual patients, none to dyadic patients.

Conclusions:

Multiple surveys for measuring PCC in hospitals are available. Opportunities exist to improve survey comprehensiveness regarding dimensions of PCC, reporting of psychometric properties, and development of measures to capture PCC for dyadic patients.

Keywords: survey instrument, in-patient care, individual care, dyadic care, patient dyad

Introduction

The Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) 2001 report, Crossing the Quality Chasm, solidified the importance of patient-centered care (PCC) as one of the six core aims for health care improvement. The IOM defined PCC as “providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.”1 The Picker Institute further elaborated that PCC has eight dimensions: 1) respect, 2) care coordination and integration, 3) information, communication, and education, 4) physical comfort, 5) emotional support, 6) involvement of family and friends, 7) transition and continuity, and 8) access to care (Table 1).2

Table 1.

Eight Picker Dimensions articulated by the Picker Institute/Commonwealth Fund

| Dimension | Dimension description |

|---|---|

| Respect | Respect for patient-centered values, preferences, and expressed needs, including awareness of quality-of-life issues, involvement in decision-making, dignity, and attention to patient needs and autonomy. |

| Coordination/Integration | Coordination and integration of care across clinical, ancillary, and support services and in the context of receiving “frontline” care. |

| Information/Communication/Education | Information, communication, and education on clinical status, progress, prognosis, and processes of care in order to facilitate autonomy, self-care, and health promotion. |

| Physical comfort | Physical comfort, including pain management, help with activities of daily living, and clean and comfortable surroundings. |

| Emotional support | Emotional support and alleviation of fear and anxiety about such issues as clinical status, prognosis, and the impact of illness on patients, their families, and their finances. |

| Family/Friends | Involvement of family and friends in decision-making and awareness and accommodation of their needs as caregivers. |

| Transition/Continuity | Transition and continuity as regards information that will help patients care for themselves away from a clinical setting, and coordination, planning, and support to ease transitions. |

| Access | Access to care, with attention to time spent waiting for admission or time between admission and placement in a room in the inpatient setting. |

Research shows that PCC contributes to higher value care, as it increases treatment compliance3, decreases unnecessary diagnostic testing4, improves clinical outcomes5, and increases patient satisfaction.5 Data from hospitals show PCC increases physical comfort through improved pain control6 and suggest PCC decreases patient/caregiver anxiety, improves patient/caregiver-provider communication, and increases participation in care.7 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) identifies PCC hospital communication as a priority area, highlighting the instrumental role of hospital staff in facilitating PCC.5 The importance of PCC has led to public reporting of and performance-based reimbursement for measures like the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey in the United States (U.S.)8,9 Accordingly, there is increasing interest in valid and reliable measures to assess PCC in hospitals to enable research and guide improvement efforts.

To facilitate these efforts, we conducted a systematic review to identify surveys for measuring PCC in hospitals, assessed the dimensions of PCC captured by each survey, and appraised each survey’s psychometric properties. Additionally, we evaluated survey applicability to individual and dyadic patient care, two distinct types of care.10,11 Individual care occurs when a single person receives care (e.g., a patient undergoing surgery), whereas dyadic patient care occurs when there are two, interrelated patients receiving care simultaneously (e.g. mother-infant care during the hospitalization for childbirth). Childbirth is the most common indication for hospitalization in the U.S., illustrating the frequency of dyadic care in the hospital setting, although individual care receives much attention.12 We consider whether the surveys identified are designed individual and/or dyadic care.

This review contributes to the field by providing an inventory of tested PCC measures for hospital care with their reported psychometric properties, an assessment of survey comprehensiveness in capturing key dimensions of PCC, and an evaluation of measure applicability to individual and dyadic patients.

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted a search of PubMed, Web of Science, and EBSCO Host in January 2019. Studies published in English prior to January 2019 were considered. Our search terms were: “patient-centered”, “family-centered”, “culture”, “questionnaire”, and “survey”. “Family-centered” was included because PCC is addressed using this term in various hospital settings.13 For example, “family-centered care” is recommended by the Society for Critical Care Medicine and the American Academy of Pediatrics in all cases that include pediatric patients.13,14 “Culture” was included because PCC has been described as a culture of care.2,15 “Questionnaire” was included because it is a synonym for “survey.” Though sounding similar and helpful to PCC, because person-centered care is defined as care utilizing the accumulated knowledge of the whole person over time it was not included as a search term given our focus on PCC during hospitalizations, which are often acute, time-limited encounters where accumulated knowledge is less feasible.16 Moreover, person-centered care is not regarded as a dimension of PCC. However, articles on person-centered care identified by the search were assessed, when “patient-centered care” was an article keyword.

Article selection

Identified articles were screened using titles and abstracts by two authors. Our survey inclusion criteria were: 1) administration for hospital care, 2) measuring PCC in accordance with the IOM definition, 3) measuring at least three Picker dimensions of PCC, and 4) reporting at least one psychometric property. We focused on surveys measuring at least three PCC dimensions in order to reflect and adequately capture the multidimensional nature of PCC as described by the Picker Institute/The Commonwealth Fund, an accepted and influential PCC framework.2,17–20 We chose this framework because: 1) it has been a conceptual framework for published PCC studies in other healthcare contexts17–19, 2) was developed via focus groups and national interviews with multiple stakeholders, 3) integrates interpersonal aspects of care, and 4) emphasizes the multidimensionality of PCC through eight parsimonious and comprehensive dimensions. Reporting of at least one psychometric property was a criterion because we sought to assess measures with evidentiary basis. Full-text review was completed for articles meeting the inclusion criteria or if inclusion was unclear. Reference lists of articles identified via the search were screened for additional titles warranting review. We consulted with three PCC experts (>15 years of research experience) to solicit additional recommendations of articles/surveys for review. Duplicate articles were eliminated.

Data items and collection

The following data elements were extracted from surveys meeting inclusion criteria: 1) survey name, 2) respondent type (patient/family and/or hospital staff), 3) number of items and response scale (e.g. Likert scale), 4) hospital unit and surveyed population, 5) subscales identified by the survey developers/authors, 6) number of survey items associated with each Picker dimension, 7) psychometric properties of the survey, and 8) applicability to individual and dyadic care. All data elements were extracted directly from the articles, except for elements #6 and #8, which we determined in our review. For surveys appearing in multiple articles, the data reported for each survey was based on all relevant articles.

Assessing dimensions of PCC

For each survey, we assessed how many of the eight Picker dimensions of PCC were measured.2 Two authors independently reviewed survey items to assess if each item reflected a Picker dimension, if any, based on the definitions published by Shaller in 2007 (Table 1).2 The initial review of survey items revealed a need for two coding clarifications. First, whether to include items related to bedside care and hospital level actions (e.g. The philosophy of [patient-centered] care is taught as part of orientation for new unit employees21). We decided to include and code items at both levels in recognition that PCC can be displayed at multiple levels. Second, we clarified the coding of items in which the subject was family/friends, but the item’s action was a different Picker dimension. An example is: “Explanations are presented [action] to the family [subject] using a variety of techniques depending on the individual needs and learning styles of the family.”22 We decided to code items based on the action, as if the subject was the patient as in other surveys. Thus, the aforementioned example was coded “information, communication, and education”. After independent coding with these clarifications, the interrater reliability was very strong (κ=0.93; standard error=0.02). For the 27 discrepant items all authors discussed final coding decisions.

Assessing psychometric properties

To evaluate each survey’s psychometric strength, we reviewed reported reliability and validity metrics, which are fundamental indicators of survey quality.23–25 Reliability refers to how consistently a construct is measured, with greater similarity indicating greater reliability. Cronbach α, a standard reliability measure of internal consistency, indicates similarity of reports across items intended to capture the same concept.25,26 Cronbach α ranges from 0 to 1, and acceptable values are >0.7.27 Notably, α values increase with scale length and high α values may reflect item redundancy rather than greater reliability.25 The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and Pearson correlation coefficient, standard reliability measures of intra- and interrater agreement and reliability, assess the similarity of responses from different raters exposed to the same stimuli or to the same stimuli at different times.25,28 ICC and Pearson correlation coefficients of 0.5–0.75 indicate moderate reliability, 0.75–0.9 good reliability, and 0.9–1 excellent reliability, with 1 indicating perfect agreement and consistency.25,29

Validity, which refers to the degree that a construct captures what it claims to measure, is assessed by construct and content validity. Construct validity is used to evaluate if a group of items all measure the same construct and is often assessed using factor analysis. Factor analysis indicates the covariance of items, items with a high level of covariance all assess the same factor or construct. Factor analyses should report the number of factors, associated Eigenvalues of retained factors, and factor loadings (>0.4 is generally accepted as capturing a factor).25 Content validity evaluates if the survey truly reflects the construct of interest and is often achieved by triangulation, which relies on the integration of qualitative and quantitative methods.30 We reviewed all included articles for information about the aforementioned reliability and validity indicators, and recorded any other psychometric properties reported.

Assessing applicability to individual versus dyadic care

We defined individual care as care delivered to a single patient and dyadic care as care delivered to two interrelated patients simultaneously. Preexisting criteria to assess the applicability of PCC surveys to dyadic care do not exist. Our determination was based on subjective assessment and discussion amongst the authors, guided by three criteria: 1) Did the study population include a patient dyad? 2) Are survey items easily adaptable to address the multiplicity of patients and staff in dyadic care? and 3) Do survey items address at least three PCC dimensions in relation to dyadic care? We considered all Picker PCC dimensions as potentially applicable to the dyad because it is a comprehensive framework. When associated items did not or could not extend to dyadic care based on our criteria, we recorded a survey as suited for individual care only.

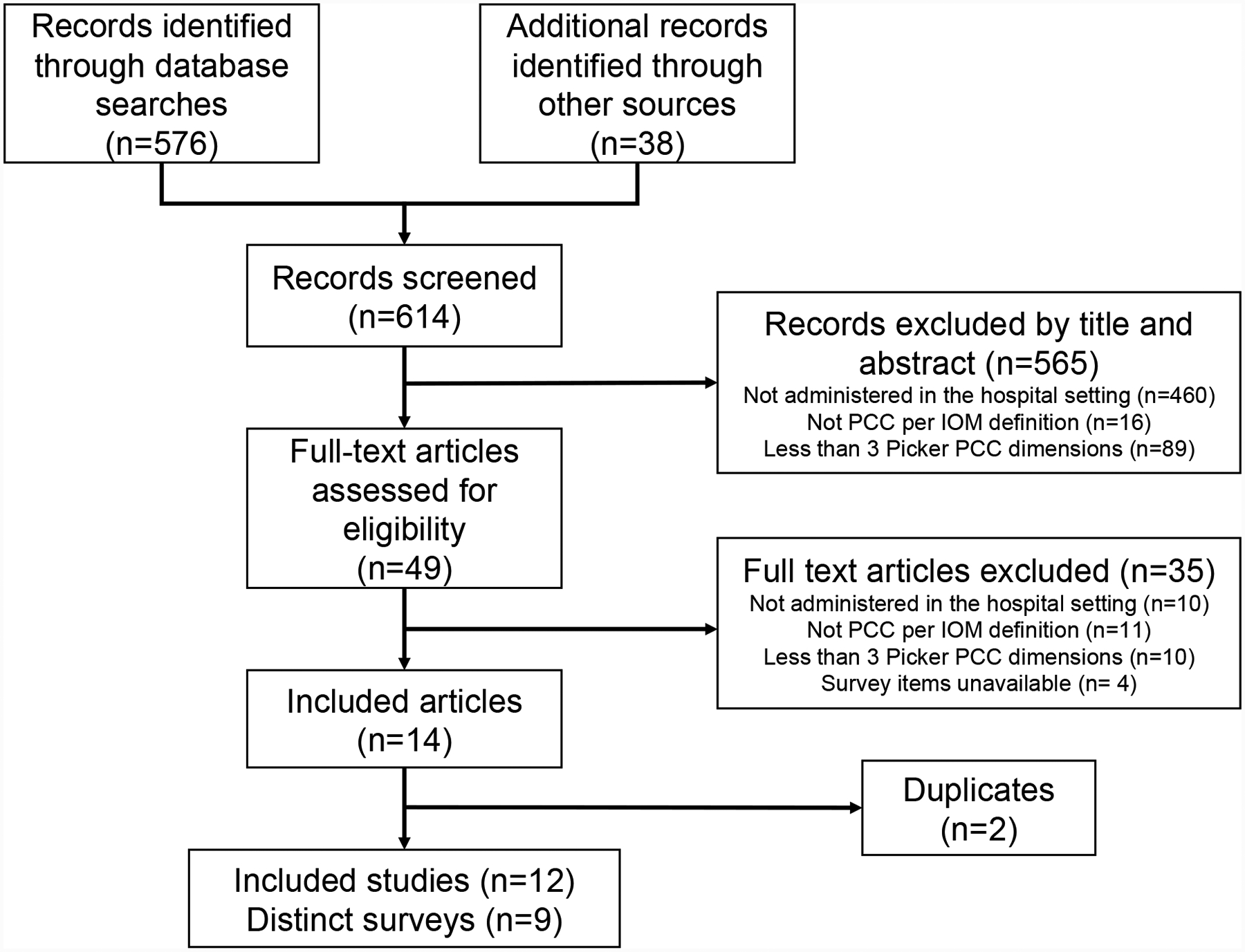

Results

Our search identified 576 articles. Screening of article reference sections identified another 36 citations and expert consultation an additional two, for a total of 614 articles. Forty-nine articles were reviewed in full. Fourteen articles met all inclusion criteria, of which two were duplicates, leaving 12 articles using nine surveys for further review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Abbreviations: PCC: patient-centered care; IOM: Institute of Medicine

Of the nine surveys identified, five obtained the perspective of patients or families and were published as assessments of patient experience or person-centered care (Table 2).31–35 The other four surveys obtained the perspective of hospital staff, with two of the four also incorporating familial responses (Table 3).21,22,36,37 One of these surveys elicited a consensus response from staff, patients, and families, while the other asked families to respond to items regarding the built environment. The four surveys reflecting the staff and/or staff and patient/family perspective were published as assessments of family-centered or person-centered care. Table 2 (patient/family-reported surveys) and Table 3 (staff or staff and patient/family-reported surveys) present survey characteristics and properties.

Table 2.

Surveys measuring patient, person or family-centeredness from the perspective of patients or families in the hospital setting.

| Survey name and author | Survey description | Author-reported Subscales | Picker PCC dimensions† | Psychometric properties | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Setting and sample for administration | Number of items | Response scale | ||||

| Picker Patient Experience (PPE-15); Jenskinson et al.35 | Patients (n=62,925) from acute care hospitals in five countries (UK, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and the USA) | 15 | yes/no or 3 to 4 scale choices |

|

|

Total scale α=0.80 to 0.87 (by country) |

| Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) Survey; Goldstein et al.36 | Patients (n=49,812) from 45 Maryland hospitals, 26 Arizona hospitals and 61 New York hospitals | 25, excluding demographic questions | yes/no, 4-point scale and 10-point scale for rating experience during the hospitalization |

|

|

*Analysis of the original 33 items with Item-total composite correlations were >0.4, for all but 2 items. 6 factors identified with 30 of 33 items loading >0.3. Shortened (16 question) version: Subscale #1-#7 α=0.51–0.88, >0.7 for 4 of 7 subscales. 16 questions load on to 7 factors with factor loadings >0.5744 |

| Person-centered climate questionnaire—patient version (PCQ-P); Edvardsson et al.37 | Patients (n=544) in 21 sub-acute and acute hospital wards in Sweden | 17 | 7-point Likert scale |

|

|

Total scale α=0.93; Subscales: α=0.64–0.94; Average ICC 0.73 (95% CI 0.58–0.85) |

| Person-centered climate questionnaire—family version (PCQ-F); Lindahl et al.38 | Family members (n=200) in one Emergency Department in Sweden | 17 | 6-point Likert scale |

|

|

Total scale α=0.93; Subscales α=0.75–0.95 |

| Family Inventory of Needs (FIN); Catlin, et al.39 | Parents (n=19) of pediatric oncology patients | 20 | Answer choices have three options (e.g: met, unmet, blank) |

|

|

#Total scale α=0.83–0.9642,43 |

Abbreviations: PCC: patient-centered care; ICC: intraclass correlation coefficient; CI: confidence interval

The numbers in parentheses refer to the number of survey items associated with the listed Picker dimension. Items were assigned to only one Picker dimension. Some items did not match one of the Picker dimensions and were labeled as not applicable. The number of not applicable items in each survey are not included in the table.

The HACHPS article by Goldstein et al. identified in our search referenced previous publications providing the psychometric data, primarily Keller et al. 2005, which is reflected in the HCAHPS psychometric properties reported.

Cronbach’s alpha as reported by Kristjanson et al. 1995 and Fridriksdottir et al 2006.

Table 3.

Surveys measuring patient, person or family-centeredness from the perspective of staff or staff and patients in the hospital setting.

| Section A. Staff perspective | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey name and author | Survey description | Author-reported Subscales | Picker PCC dimensions† | Psychometric properties | ||

| Setting and sample for administration | Number of items | Response scale | ||||

| Family Centered Care Questionnaire (FCCQ); Bruce and Ritchie26 | Nurses (n=124) caring for hospitalized children in Canada | 45 | 5-point Likert scale |

|

|

Total scale: α=0.9; Subscales: α=0.5 to 0.8; Test-retest correlations: 0.6–0.8. |

| Person-centered climate questionnaire-staff version (PCQ-S); Edvardsson et al.41 | Health care and support staff (n=52) in a short-stay unit offering elective surgery, diagnostic procedures and other planned services for public hospitals in Australia | 14 | 6-point Likert scale |

|

|

Total scale α=0.89; Subscales: α=0.69–0.87; Test-retest reliability with mean score p-values >0.05. Single measure intra-class correlation (ICC) of 0.75 (95% CI 0.58–0.86). |

| Section B. Staff and patient/family perspective | ||||||

| Pediatric Patient-Family-Centered Care (PFCC) Benchmarking Survey; Carmen et al.40 | Hospital leadership (n=770), staff (n=666) and families (n=267). (families were only asked about subscales #8-#17) | 108 | 4-point Likert scale |

|

|

Subscales: α=0.76–0.94; Factor analysis: items loaded on to subscales at 0.61 or greater. |

| Advancing Family-Centered Newborn Intensive Care: a self-assessment inventory; Dall’Oglio et al.25 | Representative group of staff and patients completed one assessment per neonatal intensive care unit (n=46) | 98 (186 including all sub-items) | 5-point Likert scale (status of family-centered care), 3-point scale for ranking the priority for change/improvement, and 5 open ended questions. |

|

|

Subscales α=0.75–0.96 (α for reporting of current status of care delivered). |

Abbreviations: PCC: patient-centered care; ICC: intraclass correlation coefficient; CI: confidence interval

The numbers in parentheses refer to the number of survey items associated with the listed Picker dimension. Items were assigned to only one Picker dimension. Some items did not match one of the Picker dimensions and were labeled as not applicable. The number of not applicable items in each survey are not included in the table.

Survey characteristics differed. There was heterogeneity in the survey administration setting and population, ranging from emergency to pediatric oncologic care and adult short-stay to neonatal intensive care units. Sample populations ranged from 19 to over 60,000 respondents, with the majority administered to ≤250 people. Survey length ranged from 14 to 107 items with two to 20 author-specified subscales. We assessed a median of 6 (range 5–7) Picker dimensions in the identified surveys. Respect and information, communication and education were the two dimensions captured in all surveys. The next more frequent dimensions were physical comfort, emotional comfort, and involvement of family and friends, which were present in eight surveys. The least assessed dimensions were coordination and integration and access to care, present in four surveys. Within each survey, the number of items associated with one Picker dimension ranged from 1 to 49.

Reporting of psychometric properties varied. None of the articles we found reported all reliability, both α and an ICC or Pearson’s correlation coefficient, and validity, construct and content, measures. Cronbach’s α was the only measure available for all surveys or author-specified survey subscales. When reported for the entire survey (six of nine), the reliability was acceptable (α≥0.8).27 The reported reliability of author-specified subscales was more variable, with Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.5 (one of nine subscales, Family-Centered Care Questionnaire (FCCQ)22) to 0.96 (environment and design subscale, Advancing family-centered newborn intensive care: a self-assessment inventory21). Two surveys reported a reliable ICC, the Person-Centered Climate Questionnaire-Patient Version (PCQ-P, 0.7333) and the Person-Centered Climate Questionnaire-Staff Version (PCQ-S, 0.7537). None of the articles reported a Pearson correlation coefficient. Factor analysis for validity was only reported for the Patient Family-Centered Care (PFCC) Benchmarking survey.36 There were two surveys, the Family Inventory of Needs (FIN) and HCAHPS surveys, in which the identified articles cited previous publications for information on scale reliability (FIN)38,39 or reliability and validity (HCAHPS).40

None of the identified surveys were administered to a dyadic patient or referenced two patients. While all surveys reflect multiple PCC dimensions, we deemed none readily adaptable to dyadic care, as none allowed for consideration of or captured the nuances of caring for two patients simultaneously. Such extension was not a reported intent of survey authors/developers.

Discussion

Our review identified nine surveys available to measure PCC and highlights opportunities to advance PCC measurement. In accordance with the IOM’s emphasis on respect for patient preferences, every survey includes the dimension of respect. Additionally, four other dimensions of PCC ―information, communication, and education, physical comfort, emotional comfort, and involvement of family and friends― were frequently assessed, suggesting these dimensions are either a priority in care delivery or are more acceptable and accessible dimensions to measure. One might presume a tradeoff in the assessment of PCC: covering more dimensions requires more items, which can burden respondents and limit response. Yet, there were four surveys that captured seven PCC dimensions, which varied in length from 15 to 186 items. This indicates that multidimensional measures of PCC can be succinct or longer, meaning users can select surveys that fit their objectives. In our analysis, however, no single survey captured all eight PCC dimensions and reporting of survey psychometric properties, particularly validity, is inconsistent. Additionally, measurement development has focused on individual not dyadic patient care.

The surveys identified suggest that patients, families, and hospital staff can all be assessors of PCC. However, we observed differences in the PCC dimensions assessed by patients/families versus staff, with patients/families more frequently assessing access to care and hospital staff more frequently assessing care coordination and integration. This observation is noteworthy because health professionals such as hospital staff are crucial to delivering PCC. Although the interchangeability of assessors was not addressed in the articles reviewed, data have shown assessments of PCC dimensions can differ between patients and providers.41 While patient assessment of PCC is presumably the gold standard, the presence of surveys designed to obtain the perspective of hospital staff illustrate the variety of sources for PCC data, which may relate to the care setting. The reality may be that each assessor group offers reliable and valid assessments of specific dimensions.

The inconsistent and limited reporting of survey psychometric properties is an opportunity for improvement. The majority of studies only reported reliability per Cronbach’s α, because surveys were administered to one population. The reliability and generalizability of the surveys identified would increase if administration was repeated or responses compared across different populations. Reporting of validity testing was very limited. Face validity, a subjective validity measure, cannot be quantified, which is why construct and content validity are expected measures of survey quality. Construct validity testing using factor analyses requires an adequate number of responses and is based on the survey length. Five of the surveys were administered to ≤250 people, which likely limited completion of factor analyses. Evidence of content validity testing was not available in any of the articles, which is less surprising as surveys are often developed to measure an unmeasured construct. Many of the surveys identified were relatively new, likely contributing to limited reports of concurrent validity (the survey’s ability to predict outcomes). Exceptions are the FCCQ22,42, HCAHPS32,43,44, and PPE-15 surveys, which have been more extensively studied. While our search found no articles with psychometrics for the current version of HCAHPS, psychometrics for prior, longer versions and organizational endorsements (i.e., AHRQ and National Quality Forum) focused on robust survey evaluation suggest acceptable reliability and validity. Our findings highlight the need for greater attention to and consistent reporting of reliability and validity measures for PCC surveys. Such reporting is critical to support informed selection and application of PCC measures across different populations and epochs, and evaluation of result robustness. Without knowledge of PCC survey psychometric properties, the significance of PCC interventions evaluated using these surveys cannot be fully determined, limiting advances in PCC delivery.

This review also highlights the opportunity to adapt or develop PCC measures for dyadic care. The distinction between individual and dyadic care is often overlooked, though the importance of distinguishing dyadic care is increasingly recognized.11,45–47 Dyadic care is unique in that there are two patients whose PCC needs are intertwined, and may be aligned or at odds. Using the mother-infant dyad as an example, the alignment of mother-infant PCC needs is demonstrated in studies of breastfeeding48 and caring for opioid dependent mother-infant dyads.45 Conversely, their PCC needs may be at odds when for example, a mother with an active, viral illness (e.g. influenza) delivers a baby and plans to maximize time breastfeeding, which would be PCC for her but may not be for her infant for whom separation may be best until mother’s symptoms resolve. This example illustrates the risk-benefit balancing in PCC for dyadic patients. Additionally, while care for individual patients with multiple conditions requires coordination, it does not involve the coordination of teams with two different patients as their focus, which increases and complicates care coordination and communication. Shortcomings in care team communication and coordination during individual care impede PCC49, which is likely magnified for dyadic care. It is therefore important to consider these different types of patients separately. To obtain accurate measures of PCC, surveys should consider PCC dimensions relevant to dyadic care and account for the complementary and potentially competing needs and preferences of dyadic patients. Given the volume of dyadic care annually12, future research should assess what are the dimensions of dyadic PCC (versus assuming they are the same as individual care), how best to measure the balancing of PCC within the dyad, and associations with patient and hospital outcomes. Future research should also examine the applicability of hospital dyadic PCC measures to outpatient care.

One of the strengths and contributions of this review is the focus on hospitals, which differentiates it from previous publications regarding outpatient care.50 Another contribution is our coding of the individual survey items and associated Picker dimensions, which provides data regarding the breadth of available PCC measures. Our review’s reporting of the survey psychometric properties is a contribution in that it enables survey selection for future assessments and research. To the extent, it facilitates the use of more reliable and valid surveys, the rigor of PCC studies will increase. Finally, the assessment of PCC measure applicability to different types of patients, the individual versus dyad, is a unique strength for understanding and quantifying care for all patient types.

The primary limitation of this review is the potential of missed or omitted surveys. Despite our attempts to query a variety of databases and use appropriate search terms, there may be surveys that we did not identify. However, we supplemented our electronic search with a manual search and expert consultation to enhance completeness of our review. We did not include person-centered care as a search term because such care, while beneficial for PCC (our focus), requires an accumulated knowledge of the whole person over time (e.g., multiple, longitudinal clinic visits), by definition, whereas hospital care does not. While our focus on PCC may have improved the relevance of our findings to hospital care, it may have led to the identification of surveys disproportionately focused on the assessment of Picker dimensions pertinent to hospitalizations (e.g. physical comfort) versus those related to the continuum of care (e.g. involvement of family and friends or continuity and transition). Finally, this review is limited to measures consisting of three or more PCC dimensions in order to capture a more comprehensive view of PCC. Although not addressed in this review, other surveys measuring one or two PCC dimensions are available to address research inquiries or improvement efforts related to specific dimensions.

In summary, there are a variety of published surveys available for the assessment of PCC in hospitals, which range greatly in length, comprehensiveness as reflected by the Picker dimensions, and reported reliability and validity. This review illuminates the opportunities for development of a survey that measures all dimensions of PCC and for greater sharing of psychometric data about existing surveys of PCC for individual care. Additionally, because surveys to measure dyadic care have not been developed, nor is it apparent that available surveys are amenable to adaptation to this type of care, our review highlights another important area for PCC measure development. Given the aforementioned benefits of PCC for hospitalized patients6,7 and the volume of dyadic dare (e.g., mother-infant care in the U.S.12), attending to PCC in the context of dyadic care is warranted. Increasing our understanding of PCC for dyadic and individual patients in the hospital may provide insights and avenues for change that could have widespread effects across the U.S and provide a valuable framework for assessing PCC in many patient populations.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to acknowledge the support received to complete this work from the National Institutes of Health (T32HD007440 to SH) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (U18 HS016978—Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) IV for IN).

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

References:

- 1.Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, National Research Council. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Summary Report Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaller D. Patient-Centered Care: What Does It Take? The Commonwealth Fund; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD. Physician-patient communication in the primary care office: A systematic review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15(1):25–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein RM, Franks P, Shields CG, et al. Patient-centered communication and diagnostic testing. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(5):415–421. doi: 10.1370/afm.348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agency for Health Research and Quality. 2018 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report; 2018. https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr18/index.html. Accessed August 26, 2020. [PubMed]

- 6.Tavares AP, Paparelli C, Kishimoto CS, et al. Implementing a patient-centred outcome measure in daily routine in a specialist palliative care inpatient hospital unit: An observational study. Palliat Med. 2017;31(3):275–282. doi: 10.1177/0269216316655349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaziunas E, Hanauer DA, Ackerman MS, Choi SW. Identifying unmet informational needs in the inpatient setting to increase patient and caregiver engagement in the context of pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2016;23(1):94–104. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anhang Price R, Elliott MN, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Examining the role of patient experience surveys in measuring health care quality. Med Care Res Rev. 2014;71(5):522–554. doi: 10.1177/1077558714541480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elliott MN, Beckett MK, Lehrman WG, et al. Understanding The Role Played By Medicare’s Patient Experience Points System In Hospital Reimbursement. Health Aff. 2016;35(9):1673–1680. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyons KS, Lee CS. The Theory of Dyadic Illness Management. J Fam Nurs. 2018;24(1):8–28. doi: 10.1177/1074840717745669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Handley SC, Nembhard IM. Measuring patient-centered care for specific populations: A necessity for improvement. Patient Exp J. 2020;7(1). [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDermott KW, Elixhauser A, Sun R. Trends in Hospital Inpatient Stays in the United States, 2005–2014. HCUP Statistical Brief #225 June 2017. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb225-Inpatient-US-Stays-Trends.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, et al. Guidelines for Family-Centered Care in the Neonatal, Pediatric, and Adult ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(1):103–128. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Committee on Hospital Care. Family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3 I):691–696. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.3.691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greene SM, Tuzzio L, Cherkin D. A framework for making patient-centered care front and center. Perm J. 2012;16(3):49–53. doi: 10.7812/tpp/12-025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Starfield B Is patient-centered care the same as person-focused care? Perm J. 2011;15(2):63–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dancet EAF, Nelen WLDM, Sermeus W, de Leeuw L, Kremer JAM, D’Hooghe TM. The patients’ perspective on fertility care: A systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(5):467–487. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmq004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gameiro S, Canavarro MC, Boivin J. Patient centred care in infertility health care: Direct and indirect associations with wellbeing during treatment. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(3):646–654. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shrivastava R, Couturier Y, Kadoch N, et al. Patients’ perspectives on integrated oral healthcare in a northern Quebec Indigenous primary health care organisation: A qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7). doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Labrusse C, Ramelet A-SS, Humphrey T, Maclennan SJ. Patient-centered Care in Maternity Services: A Critical Appraisal and Synthesis of the Literature. Women’s Heal Issues. 2016;26(1):100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2015.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dall’Oglio I, Portanova A, Tiozzo E, Gawronsk O, Rocco G, Latour JM. OC47 - NICUs and family-centred care, from the leadership to the design, the results of a survey in Italy (by FCC Italian NICU study group). Nurs Child Young People. 2016;28(4):86. doi: 10.7748/ncyp.28.4.86.s78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruce B, Ritchie J. Nurses’ practices and perceptions of family-centered care. J Pediatr Nurs. 1997;12(4):214–222. doi: 10.1016/s0882-5963(97)80004-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 63:737–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Litwin MS. How to Assess and Interpret Survey Psychometrics. 2nd ed. SAGE; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Streiner DL, Norman GR, Cairney J. Health Measurement Scales. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests. Psychometrika. 1951:16(3)297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hundleby JD, Nunnally J. Psychometric Theory. Am Educ Res J. 1968;5(3):431. doi: 10.2307/1161962 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass Correlations : Uses in Assessing Rater Reliability. 1979:(86)420–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Portney L Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Evidence-Based Practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jick TD. Mixing Qualitative and Quantitative Methods: Triangulation in Action. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24(4):602. doi: 10.2307/2392366 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Bruster S. The Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire: development and validation using data from in-patient surveys in five countries. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2002;14(5):353–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldstein E, Farquhar M, Crofton C, Darby C, Garfinkel S. Measuring hospital care from the patients’ perspective: An overview of the CAHPS® Hospital Survey development process. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 II):1977–1995. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00477.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edvardsson D, Koch Rhonda Nay S. Psychometric Evaluation of the English Language Person-Centered Climate Questionnaire-Patient Version. West J Nurs Res. 2009;31:235–244. doi: 10.1177/0193945908326064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindahl J, Elmqvist C, Thulesius H, Edvardsson D. Psychometric evaluation of the Swedish language Person-centred Climate Questionnaire-family version. Scand J Caring Sci. 2015;29(4):859–864. doi: 10.1111/scs.12198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Catlin A, Ford M, Maloney C. Determining Family Needs on an Oncology Hospital Unit Using Interview, Art, and Survey. Clin Nurs Res. 2016;25(2):209–231. doi: 10.1177/1054773815578806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carmen S, Teal S, Guzzetta CE. Development, testing, and national evaluation of a pediatric Patient-Family-Centered Care benchmarking survey. Holist Nurs Pract. 22(2):61–74; quiz 75–76. doi: 10.1097/01.HNP.0000312653.83394.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edvardsson D, Koch S, Nay R. Psychometric evaluation of the English language Person-centred Climate Questionnaire--staff version. J Nurs Manag. 2010;18(1):54–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.01038.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kristjanson LJ, Atwood J, Degner LF. Validity and reliability of the family inventory of needs (FIN): measuring the care needs of families of advanced cancer patients. J Nurs Meas. 1995;3(2):109–126. doi: 10.1891/1061-3749.3.2.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fridriksdottir N, Sigurdardottir V, Gunnarsdottir S. Important needs of families in acute and palliative care settings assessed with the family inventory of needs. Palliat Med. 2006;20(4):425–432. doi: 10.1191/0269216306pm1148oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keller S, O’Malley AJ, Hays RD, et al. Methods Used to Streamline the CAHPS® Hospital Survey. Vol 40; 2005:2057–2077. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00478.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bortoli A, Daperno M, Kohn A, et al. Patient and physician views on the quality of care in inflammatory bowel disease: results from SOLUTION-1, a prospective IG-IBD study. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(12):1642–1652. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alabdulaziz H, Moss C, Copnell B. Paediatric nurses’ perceptions and practices of family-centred care in Saudi hospitals: A mixed methods study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;69:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCaughey D, Stalley S, Williams E. Examining the effect of EVS spending on HCAHPS scores: a value optimization matrix for expense management. J Healthc Manag. 2013;58(5):320–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mcmillan MO. The Effects of Watson’s Theory of Human Caring on the Nurse Perception and Utilization of Caring Attributes and the Impact on Nurse Communication; 2017. https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/nursing_etd/267. Accessed October 21, 2019.

- 45.Velez M, Jansson LM. The opioid dependent mother and newborn dyad: Nonpharmacologic care. J Addict Med. 2008;2(3):113–120. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31817e6105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karney BR, Hops H, Redding CA, Reis HT, Rothman AJ, Simpson JA. A framework for incorporating dyads in models of HIV-prevention. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(SUPPL. 2):189–203. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9802-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Handley SC, Srinivas SK, Lorch SA. Regionalization of Care and the Maternal-Infant Dyad Disconnect. JAMA. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.6403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dieterich CM, Felice JP, O’Sullivan E, Rasmussen KM. Breastfeeding and Health Outcomes for the Mother-Infant Dyad. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2013;60(1):31–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2012.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zwarenstein M, Rice K, Gotlib-Conn L, Kenaszchuk C, Reeves S. Disengaged: a qualitative study of communication and collaboration between physicians and other professions on general internal medicine wards. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):494. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hudon C, Fortin M, Haggerty JL, Lambert M, Poitras ME. Measuring patients’ perceptions of patient-centered care: A systematic review of tools for family medicine. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(2):155–164. doi: 10.1370/afm.1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]