Abstract

Objective

We analyze fertility preferences among women at risk of pregnancy with children ages five or younger as a function of two food security metrics: perceptions of household hunger and child stunting (height for age z scores ≤−2.0z) in order to convey a robust picture of food insecurity.

Methods

We use data from the 2016 Tanzania Demographic and Health Surveys to analyze this research question. Multinomial generalized logit models with cluster-adjusted standard errors are used to determine the association between different dimensions of food insecurity and individual-level fertility preferences.

Results

On average, women who experience household hunger are 19% less likely to want more children compared to women who do not experience household hunger (AOR: 0.81, p=0.02) when controlling for education, residence, maternal age, number of living children, and survey month. Adjusting for the same covariates, having at least one child ≤5 years old who is stunted is associated with 13% reduced odds of wanting more children compared to having no children stunted (AOR: 0.87, p=0.06).

Conclusions for Practice

In the context of a divided literature base, this research aligns with the previous work identifying a preference among women to delay or avoid pregnancy during times of food insecurity. The similarity in magnitude and direction of the association between food insecurity and fertility preferences across the two measures of food insecurity suggest a potential association between lived or perceived resource insecurity and fertility aspirations. Further research is needed in order to establish a mechanism through which food insecurity affects fertility preferences.

Keywords: food insecurity, household hunger, child stunting, fertility preferences, sub-Saharan Africa

INTRODUCTION

Fertility and food insecurity have a complex relationship. Accounting for this complexity, the birth seasonality framework suggests that there are biological and behavioral mechanisms behind changes in fertility that coincide with seasonal changes in food availability (Grace, Lerner, Mikal, & Sangli, 2017; Grace & Nagle, 2015). Some evidence suggests that women modify their short-term fertility goals, including birth timing and aspirations, when food is scarce (Clifford, Falkingham, & Hinde, 2010; Grace et al., 2017; Patel & Surkan, 2016). This may be explained by increased stress leading to less sexual activity, a fear of insufficient calories/nutrition affecting pregnancy, and continued breastfeeding through times of food scarcity (Grace, 2017; Grace et al., 2017; Rogawski McQuade et al., 2019). However, there is also conflicting evidence suggesting that fertility does not change, and might even increase, when an individual or household experiences food insecurity. An increase, or no change, in fertility during times of food scarcity may be explained by the increased financial burden of contraceptives during resource constrained periods, gratification in a time of uncertainty, a fear that the situation will only worsen, or to strengthen social and economic ties (Grace et al., 2017; Madhavan, 2010; Scheper-Hughes, 1993; Sennott & Yeatman, 2012).

While there are biological and behavioral mechanisms behind changes in fertility outcomes that coincide with seasonal changes in food availability, this paper builds on qualitative research that underscores the complexity of fertility preferences across periods of uncertainty (Agadjanian & Prata, 2002; Grace & Nagle, 2015; Kodzi, Casterline, & Aglobitse, 2010; Sennott & Yeatman, 2012; Yeatman, Sennott, & Culpepper, 2013). Here, we specifically concentrate on an individual woman’s fertility preferences rather than specific fertility outcomes, in order to isolate how behavioral intentions are affected by a common category of uncertainty- household food insecurity.

Increasingly, scholars are investigating the potential for fertility goals to act as a “moving target”, sensitive to dynamic contextual and individual-level factors (Gibby & Luke, 2019; Speizer, Calhoun, Hoke, & Sengupta, 2013; Staveteig, 2017; Yeatman et al., 2013). Dynamic economic and related livelihood factors feature as potentially significant influences on dynamic fertility preferences (Bongaarts & Casterline, 2013). A lack of appropriately detailed data limits scientific understanding of fertility decision-making in a context of resource insecurity. However, recently collected survey data from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) contains information on household level perceptions of resource insecurity relating to food insecurity, in addition to the standard information on fertility preferences (Croft, Marshall, Allen, & al., 2018).

We use Tanzania as a case study to assess the association between food insecurity and fertility preferences. Tanzania is characterized by widespread reliance on small-scale, household agriculture with routine seasonal hunger periods resulting in chronic and persistent food insecurity (FEWS NET, 2017; Kabote, 2018; Rogawski McQuade et al., 2019). Tanzania also has some of the highest fertility rates in the world, with a total fertility rate (TFR) in 2017 of 5.2 (Population Reference Bureau, 2017). The total wanted fertility rate in Tanzania is also much higher than replacement, at 4.5 in 2017 (Tanzania Ministry of Health, 2016). The co-occurrence of high total wanted fertility rates with the common experience of periodic food insecurity in Tanzania provides a useful setting to investigate the relationship between food insecurity and fertility preferences. The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between food insecurity and fertility preferences in Tanzania. In this research and reflecting the dynamic resource environment of subsistence production in Tanzania, we use household level perceptions of food insecurity in addition to one anthropometric health measure- child stunting1- to reflect household-level variation in resources.

This analysis addresses a gap in the literature investigating the quantitative impacts of food security on fertility preferences of women in low- and middle-income countries. While there is a growing body of literature that addresses the effect that fertility preferences have on child growth, one indicator of food insecurity, this analysis examines the context that precedes birth. The gap in the existing research is multidimensional, and leads to the two central aims of this study: 1) to quantitatively assess how different indicators of food availability might be associated with women’s fertility preferences while controlling for relevant demographic covariates; and 2) to examine this question using two indicators of food insecurity- one composite measure of household perceptions of hunger and one anthropomorphic measures of child growth- to compare the results that may capture different aspects of what it means to be food insecure.

METHODS

Ethical Review

All procedures and questionnaires for the standard Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) are reviewed and accepted by the Informed Consent Form (ICF) International Institutional Review Board (IRB). The host country’s IRB ensures that surveys are compliant with all laws and norms within the country. The International IRB certifies that all surveys are compliant with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services regulations for the protection of human subjects (DHS Program, 2017).

The study uses data from the standard DHS-VII conducted in Tanzania between 2015 and 2016, which includes interviews with 13,266 women ages 15 to 49 years old. The survey sample was selected from a stratified two-stage cluster design; the first stage consists of Enumeration Areas (EA) drawn from the Census file, while the second stage selects a sample of households within each EA from an updated list of households. This design creates a sample that is representative on the national, residence (urban-rural) and regional level. The full description of the study population is included in the country report (Tanzania Ministry of Health, 2016). The analysis reported herein used only de-identified data.

Data

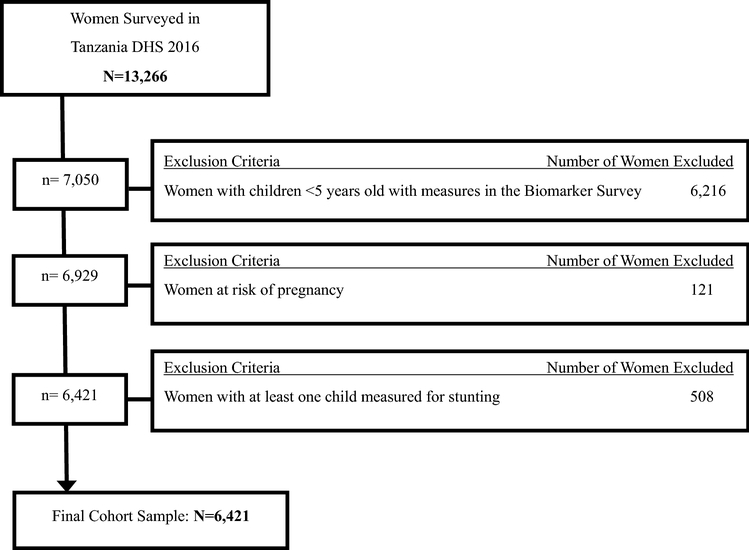

The data used in this analysis comes from the Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey in 2016, accessed through the IPUMS-DHS (Ministry of Health). Multiple questionnaires are used to compile all relevant variables, including the Women’s Questionnaire, Household Questionnaire, and Biomarker Questionnaire. The 2016 DHS captured data from 13,266 women in Tanzania (Figure 1). For the purposes of this analysis, we include only women with children ages five or younger who are measured in the Biomarker survey (n= 7,050), in order to utilize a child anthropomorphic measure as an indicator of food insecurity. We further defined the cohort by only including women who are currently at risk of pregnancy (not declared infecund or sterilized) to investigate fertility preferences (n= 6,929). The cohort was once more reduced to include only women who had at least one child measured for stunting (n= 6,421) (Croft et al., 2018).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of exclusion totals for final cohort.

Measures

Our outcome of interest is fertility preferences, captured by the desire for more children. Potential responses include: wants no more children, wants more children, or is unsure. We chose this measure of fertility preference, as opposed to desired family size or wantedness of last or current pregnancy, due to its empirically demonstrated resistance to bias (Bongaarts, 1990). Any opportunity for bias in this measure is likely to have small net offsetting effects (Bongaarts, 1990).

We use two measurements, household hunger and child stunting, as indicators of food insecurity. Household hunger measures food insecurity based on perceptions at a single point in time, while stunting captures chronic, long-term food insecurity. By using stunting in conjunction with household hunger scores, we convey a robust picture of food insecurity, based on both lived experiences and routinely used anthropometric standards that capture a long-term exposure to food deprivation. Stunting measures have long been used as indicators of household food insecurity while measures of household hunger are less commonly employed (Balk et al., 2005; Grace, Davenport, Funk, & Lerner, 2012). These two measures have the potential to offer different insights into food insecurity and what it means for a household and its members to experience food insecurity (Barrett, 2010).

The household hunger scale is a cross-culturally validated and simple indicator for household food deprivation in developing areas (Ballard, Coates, Swindale, & Deitchler, 2011). It allows us to capture the experience or perception of food insecurity on a household level (Ballard et al., 2011). The household hunger scale is comprised of three items found to be common experiences of food insecurity across diverse households: (1) In the past 4 weeks, was there ever no food to eat of any kind in your house because of lack of resources to get food?; (2) In the past four weeks, did you or any household member go to sleep at night hungry because there was not enough food?; and (3) In the past 4 weeks, did you or any household member go a whole day and night without eating anything at all because there was not enough food? (Coates et al., 2006). Participants respond yes or no to each of these questions. If they respond yes, they are asked to report on how frequently they experienced each item in the last 4 weeks using rarely (1–2 times), sometimes (3–10 times), or often (more than 10 times). The responses to each of the three questions is assigned a value between 0–2 depending on their frequency, and the scores are aggregated. The final household hunger scale ranges from 0 (little to no household hunger) to 6 (severe household hunger). For the purposes of this analysis, we create a binomial measure, assigning 0 to women with a household hunger score of 0–1 (little to no household hunger) and 1 to women with a household hunger score of 2–6 (moderate to severe household hunger). The binary measure was created due to a small cell size of severe household hunger, and sensitivity analyses confirmed that conclusions made from the binary variable were consistent with results had the household hunger score been treated as continuous or separated categorically by little to no household hunger, moderate household hunger, and severe household hunger.

The second measure of food insecurity used is child stunting, or height-for-age z scores ≤−2.0, as an indicator of chronic food insecurity and economic deprivation. We used height measurements taken in the DHS Biomarker Questionnaire to determine whether or not each child age five or younger is stunted. Consistent with related research, we adopt the World Health Organization approach and use standardized z-scores calculated by comparing each child’s height-for-age to a reference mean (Croft et al., 2018). Children whose height-for-age z-score is two standard deviations or more below the mean according to WHO 2006 Child Growth Standards are considered stunted (WHO, 2006). From this, we created a binary summary variable for each woman indicating whether or not she has at least one child five or younger who is stunted. The binary variable was created for ease of results interpretation, and sensitivity analyses confirmed that results were consistent had height-for-age z-scores been a continuous variable or had a cutoff point 0.2 above or below 2.0 standard deviations from the mean been used instead. We included all women with at least one non-missing child’s z-score. The presence of one child age five or younger with a stunted z-score was used to classify a woman as food insecure according to this measure (De Haen, Klasen, & Qaim, 2011; McDonald et al., 2015).

Factors that are relevant to food insecurity and fertility preferences were included as covariates in the analysis. These include: education, urban or rural residence, maternal age, and the total number of living children each woman has (Caldwell & Caldwell, 1985; Mosha, 2017). Many of these indicators are also highly associated with economic status and therefore that was not included in the model.

Analyses

Data cleaning and descriptive statistics were done using R version 3.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). All descriptive statistics reflect the sample population on the individual woman level, including only those with children ages five or younger who are at risk of pregnancy. Differences between women with differing fertility preferences were calculated using Chi-square tests of heterogeneity. All analyses are two-tailed with α set at 0.05. Demographic variables of interest are broken down by demographic and food security measures (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Selected characteristics of women with children five years of age or younger, by fertility preferences (N=6,421)†

| Characteristic | Wants no more children (N=1,604) | Wants more children (N=4,544) | Unsure (N=273) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education*** | |||

| No education | 23.7 | 18.9 | 16.1 |

| Any primary school | 66.0 | 57.9 | 67.8 |

| Any secondary school or higher | 10.3 | 23.2 | 16.1 |

| Residence*** | |||

| Urban | 23.9 | 25.0 | 35.2 |

| Rural | 76.1 | 75.0 | 64.8 |

| Mean age (yrs)*** | 35.3 | 27.0 | 30.4 |

| Mean number of living children*** | 5.4 | 2.7 | 3.7 |

| Household hunger*** | |||

| No household hunger | 74.6 | 80.6 | 80.6 |

| Any household hunger | 25.4 | 19.4 | 19.4 |

| Has at least one child ≤ 5 years old who is stunted*** | |||

| No children stunted | 55.6 | 61.1 | 63.4 |

| At least one child stunted | 44.4 | 38.9 | 36.6 |

p≤0.05.

p≤0.01.

p≤0.001.

All values are column percentages unless otherwise indicated; p-values calculated with Pearson’s Chi-squared test for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables

Multinomial generalized logit models were estimated using Stata SE 15 (College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC). For these models, the state of “Wants no more” children was used as the reference category and compared to other fertility preferences including “Wants more” and “Unsure”. Standard errors were adjusted to account for clustering of the data by the DHS primary sampling unit. Two models were estimated, one using household hunger and the other using at least one child ages five or younger who is stunted per woman as the independent variable of interest. Relevant covariates, including level of education, residence, maternal age, number of living children, and the month in which respondents were surveyed were added and assessed for goodness-of-fit. Significance was assessed using α set at 0.05, though any results with p≤0.1 are mentioned. DHS sample weights were not used when estimating these models for two reasons. First, the use of sample weights in the analysis of public health and social surveys is contested in the literature (Gelman, 2007). Second, the DHS sample weights are created using probability calculations and nonresponse adjustments based on the entire sample of N=13,266 women and may be inappropriate when applied to a reduced cohort as we have created here. To check these assumptions, weighted regressions were run and compared to the final models presented in the results; there were no differences in significance, magnitude or direction of our estimates of interest in the weighted compared to the unweighted models.

RESULTS

Comparisons across women with different fertility preferences were tested for significance using Pearson’s Chi-squared tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables (Table 1). Of women in this sample with at least one child age five or younger and who are at risk of pregnancy, most want more children (n=4,544). Fewer women want no more children (n=1,604), and even fewer are unsure of their fertility preferences (n=273). Women who wanted no more children were, on average, significantly older than those who wanted more children or who were unsure (p<0.001). Women who wanted more children had significantly fewer children than those who were unsure or who did not want more children (p<0.001). Women with different fertility preferences were significantly different with regard to education, residence, household hunger, and having at least one child ≤ 5 years old who is stunted (p<0.001).

Table 2 demonstrates the comparison of the two food insecurity measures used in this analysis. Using a Pearson’s Chi-squared test, household hunger and child stunting are found to be significantly associated (p= 0.009), indicating that though the two measures capture different aspects of food insecurity, there is significant overlap in the women captured in each measure.

TABLE 2.

| Household Hunger | ||

|---|---|---|

| No (N=5,078) | Yes (N=1,343) | |

| Any child ≤5 years old stunted | ||

| No | 3,081 (60.7) | 762 (56.7) |

| Yes | 1,997 (39.3) | 581 (43.3) |

p≤0.05.

p≤0.01.

p≤0.001.

Percentages indicate column percentages.

P-value calculated using Pearson’s Chi-squared test

Household Hunger and Fertility Preferences

The first model (Table 3) analyzes the association between household hunger and fertility preferences when accounting for education, residence, maternal age, number of living children, and survey month. When adjusting for education, residence, maternal age, number of living children, and the month in which respondents were surveyed, experiencing household hunger is associated with a decreased odds of wanting more children. On average, women who experience household hunger have 19% decreased odds of wanting more children compared to women who do not experience household hunger (AOR: 0.81, p=0.02). When comparing those who are unsure about their fertility preferences to those who do not want more children, experiencing household hunger is associated with 22% decreased odds of being unsure about fertility preferences, though this association is not significant (AOR: 0.78, p=0.14). Education, residence, maternal age, and number of living children are significantly associated with wanting more children compared to not wanting more children in this adjusted model.

TABLE 3.

Adjusted odds ratios (and 95% cluster-robust confidence intervals) from multinomial logistic regression analyses assessing relationship between fertility preference and Household Hunger.

| Measure | Wants more vs. Wants no more Adjusted Odds Ratio |

Unsure vs. Wants no more Adjusted Odds Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| FOOD INSECURITY† | ||

| Experiences any household hunger | 0.81 (0.69–0.96) * | 0.78 (0.56–1.08) |

| EDUCATION‡ | ||

| Any primary education | 0.63 (0.51–0.78) *** | 1.04 (0.70–1.55) |

| Any secondary or higher education | 1.19 (0.90–1.58) | 1.21 (0.73–2.02) |

| RESIDENCE§ | ||

| Urban | 1.61 (1.30–1.99) *** | 0.81 (0.56–1.11) |

| MATERNAL AGE | 0.91 (0.90–0.92) *** | 0.95 (0.92–0.97) *** |

| NUMBER OF LIVING CHILDREN | 0.67 (0.64–0.71) *** | 0.83 (0.75–0.91) *** |

p≤0.05.

p≤0.01.

p≤0.001.

Odds ratios are adjusted for all other covariates included in the table in addition to survey month to control for seasonality; estimates for survey month are not reported due to space.

Defined by household hunger; reference category is experiences no household hunger.

Reference category is no education.

Reference category is rural residence.

Child Stunting and Fertility Preferences

The second model (Table 4) analyzes the association between having at least one child ≤ 5 years old stunted per woman and fertility preferences when adjusting for education, residence, maternal age, number of living children, and the month in which respondents were surveyed. When comparing women who want more children to women who do not, having at least one child ≤ 5 years old stunted is significantly associated with fertility preferences only at α set to 0.1. Having at least one child stunted is associated with 13% reduced odds of wanting more children compared to having no children stunted (AOR: 0.87, p=0.06). When comparing those who are unsure about their fertility preferences to those who do not want more children, having any child stunted is associated with 20% decreased odds of being unsure about fertility preferences (AOR: 0.80, p=0.13). Education, residence, maternal age, and number of living children are significantly associated with wanting more children compared to not wanting more children in this adjusted model, as well (p<0.001).

TABLE 4.

Adjusted odds ratios (and 95% cluster-robust confidence intervals) from multinomial logistic regression analyses assessing relationship between fertility preference and any child ≤5 years old stunted per woman.

| Measure | Wants more vs. Wants no more Adjusted Odds Ratio |

Unsure vs. Wants no more Adjusted Odds Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| FOOD INSECURITY† | ||

| Any child ≤5 years old stunted | 0.87 (0.75–1.00) | 0.80 (0.60–1.06) |

| EDUCATION‡ | ||

| Any primary education | 0.63 (0.51–0.78) *** | 1.04 (0.69–1.55) |

| Any secondary or higher education | 1.19 (0.90–1.58) | 1.21 (0.73–2.00) |

| RESIDENCE§ | ||

| Urban | 1.65 (1.33–2.04) *** | 0.84 (0.61–1.16) |

| MATERNAL AGE | 0.91(0.90–0.92) *** | 0.94 (0.92–0.97) *** |

| NUMBER OF LIVING CHILDREN | 0.67 (0.64–0.71) *** | 0.83 (0.76–0.91) *** |

p≤0.05.

p≤0.01.

p≤0.001.

Odds ratios are adjusted for all other covariates included in the table in addition to survey month to control for seasonality; estimates for survey month are not reported due to space.

Reference category is no children ≤5 years old stunted.

Reference category is no education.

Reference category is rural residence.

DISCUSSION

The results of this analysis provide quantitative insight into the relationship between food insecurity and fertility preferences in Tanzania. With a divided qualitative evidence base, these results support the literature that suggests that times of uncertainty, such as food insecurity, are associated with a reduced odds of wanting more children (Clifford et al., 2010; Grace, 2017; Grace et al., 2017; Patel & Surkan, 2016). When operationalizing food insecurity through the experience of any household hunger, the decreased desire to want more children is significant at the α= 0.05 level (p=0.02). Women who experience household hunger have roughly 19% decreased odds of wanting more children compared to women who do not experience household hunger. This association remains even after adjusting for number of living children per woman, which is significant given the cultural value of large family size across much of sub-Saharan Africa (Bongaarts & Casterline, 2013; Caldwell & Caldwell, 1985; Korotayev, Zinkina, Goldstone, & Shulgin, 2016; Mosha, 2017). When operationalizing food insecurity through having at least one child ≤ 5 years old who is stunted, the association between food insecurity and fertility preferences is similar in magnitude and direction, but is significant only at the α= 0.1 level (p=0.06). Given the closeness of the p-values 0.02 and 0.06 in the two models, we presume these associations to be comparable in significance and look instead to the direction of the associations for insight.

This research suggests that women with young children are likely to want to delay or avoid having children when they experience food insecurity. Our results indicate that different measures of food insecurity capture overlapping portions of the population and maintain a similar relationship with fertility preferences. We posit that this significant preference to not have additional children results from a direct experience of food insecurity (or resource insecurity, more broadly) and its effects. Women experience, perceive, and report household hunger. The measure is the result of the direct experience of having difficulty feeding oneself and her family. A child who is stunted indicates long-term exposure to inadequate nutrition, potentially resulting from perceivable chronic household food insecurity, as well. The experience of uncertainty and limited resources may directly inform a woman’s desire for additional children.

Understanding the determinants of fertility preferences allows us to better understand behavior, motivations, and the connection between reproductive and sexual health preferences and behavior. This paper offers quantitative insight into a relationship that has shown many possible qualitative directions. This analysis is limited by a few important factors. First, only women with children ages five or younger were included in the sample. This is due to the DHS measure of stunting which is only taken on children ages five or younger. To compare the results between models, the sample had to be limited to include only women who had at least one child measured for stunting. Consequently, this analysis does not include all women sampled in Tanzania DHS-2016 and is therefore not nationally representative. Similarly, DHS data is cross-sectional, which does not allow for strong causal inference. Future research should include longitudinal studies to investigate how dynamic changes in food insecurity might affect fertility preferences and subsequently, fertility outcomes. Second, this analysis was only carried out in Tanzania. Future research should include a multinational analysis, given the widespread burden of resource constraints. The cross-cultural comparability of the household hunger scale, stunting and fertility preferences lends themselves to be strong points of country-to-country comparisons of the effects of food insecurity on fertility preferences. Third, this analysis was not able to examine the association between child wasting and fertility preferences due to an inadequate number of wasted children in this sample (only 6.67% of mothers had children who were wasted). Expanding this research question to assess how child wasting, which captures severe, acute food insecurity, is an important area of expansion for future research. Lastly, the models are limited in their inclusion of covariates. We included variables in the model that have established associations with both food insecurity and fertility, however the use of parsimonious models may exclude important factors, such as larger social, cultural or environmental structures that influence food insecurity and fertility preferences.

Overall, this research supports the literature that cites women’s preference to delay or avoid pregnancy during times of food scarcity. The similarity in magnitude and direction of the association between food insecurity and fertility preferences across the two measures of food insecurity indicate a consistent trend. Further research is needed in order to establish a mechanism through which food insecurity affects fertility preferences. Possible mechanisms that may be explored should include: stress; concerns about the health of existing children; frequency of sexual activity; and a fear of hunger affecting pregnancy, given their established relevance to both resource scarcity and fertility preferences.

SIGNIFICANCE.

Individual fertility preferences are sensitive to dynamic multi-level factors in a woman’s life. While qualitative research has explored the effect that food insecurity and associated resource constraints have on fertility preferences, results are conflicting.

Here, we quantitatively examine how individual woman’s fertility preferences associate with two measures of food insecurity and qualitatively compare the associations across food insecurity measures. We establish that two food insecurity measures- household hunger and child stunting-capture similar populations and have similar associations with fertility preferences. This is a critical step forward in understanding the dynamic relationship between resource availability, child well-being, and fertility preferences.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Child wasting, or low weight-for-height, may also be used here as a measure of acute rather than chronic food deprivation. Given the often significantly lower prevalence of wasting compared to stunting, this requires a substantial sample size and likely an oversampling of children who are wasted.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

REFERENCES

- Agadjanian V, & Prata N (2002). War, peace, and fertility in Angola. Demography, 39(2), 215–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balk D, Storeygard A, Levy M, Gaskell J, Sharma M, & Flor R (2005). Child hunger in the developing world: An analysis of environmental and social correlates. Food Policy, 30(5–6), 584–611. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard T, Coates J, Swindale A, & Deitchler M (2011). Household hunger scale: indicator definition and measurement guide. Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance (FANTA), 2. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett CB (2010). Measuring food insecurity. Science, 327(5967), 825–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts J (1990). The measurement of wanted fertility. PoPulation and develoPment review, 487–506. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts J, & Casterline J (2013). Fertility transition: is sub-Saharan Africa different? PoPulation and develoPment review, 38, 153–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JC, & Caldwell P (1985). Cultural forces tending to sustain high fertility in Tropical Africa.

- Clifford D, Falkingham J, & Hinde A (2010). Through civil war, food crisis and drought: Trends in fertility and nuptiality in post-Soviet Tajikistan. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 26(3), 325–350. [Google Scholar]

- Coates J, Frongillo EA, Rogers BL, Webb P, Wilde PE, & Houser R (2006). Commonalities in the experience of household food insecurity across cultures: what are measures missing? The Journal of nutrition, 136(5), 1438S–1448S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft TN, Marshall AMJ, Allen CK, & et al. (2018). Guide to DHS Statistics DHS-7. Retrieved from https://dhsprogram.com/Data/Guide-to-DHS-Statistics/index.cfm

- De Haen H, Klasen S, & Qaim M (2011). What do we really know? Metrics for food insecurity and undernutrition. Food Policy, 36(6), 760–769. [Google Scholar]

- FEWS NET. (2017). Vuli and Msimu seasons underway and average production expected in 2018. Retrieved from

- Gelman A (2007). Struggles with survey weighting and regression modeling. Statistical Science, 22(2), 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Gibby AL, & Luke N (2019). Exploring Multiple Dimensions of Young Women’s Fertility Preferences in Malawi. Maternal and child health journal, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace K (2017). Considering climate in studies of fertility and reproductive health in poor countries. Nature Climate Change, 7(7), 479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace K, Davenport F, Funk C, & Lerner AM (2012). Child malnutrition and climate in Sub-Saharan Africa: An analysis of recent trends in Kenya. Applied Geography, 35(1–2), 405–413. [Google Scholar]

- Grace K, Lerner AM, Mikal J, & Sangli G (2017). A qualitative investigation of childbearing and seasonal hunger in peri-urban Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Population and Environment, 38(4), 369–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace K, & Nagle NN (2015). Using high-resolution remotely sensed data to examine the relationship between agriculture and fertility in Mali. The Professional Geographer, 67(4), 641–654. [Google Scholar]

- Kabote SJ (2018). Farmers’ Vulnerability to Climate Change Impacts in Semi-arid Environments in Tanzania: A Gender Perspective. In: IntechOpen. [Google Scholar]

- Kodzi IA, Casterline JB, & Aglobitse P (2010). The time dynamics of individual fertility preferences among rural Ghanaian women. Studies in Family Planning, 41(1), 45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korotayev A, Zinkina J, Goldstone J, & Shulgin S (2016). Explaining current fertility dynamics in tropical Africa from an anthropological perspective: a cross-cultural investigation. Cross-Cultural Research, 50(3), 251–280. [Google Scholar]

- Madhavan S (2010). Early childbearing and kin connectivity in rural South Africa. International Journal of Sociology of the Family, 139–157. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald C, McLean J, Kroeun H, Talukder A, Lynd L, & Green T (2015). Household food insecurity and dietary diversity as correlates of maternal and child undernutrition in rural Cambodia. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 69(2), 242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, C. D., Gender, Elderly and Children [Tanzania], Ministry of Health [Zanzibar], National Bureau of Statistics [Tanzania], Office of the Chief Government Statistician, and ICF. . Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey 2015–16 [Dataset]. . Retrieved from: http://idhsdata.org

- Mosha IH (2017). The puzzle of family planning in Tanzania: A multi-method approach for understanding the use of family planning practices: [Sl: sn].

- Patel SA, & Surkan PJ (2016). Unwanted childbearing and household food insecurity in the United States. Maternal & child nutrition, 12(2), 362–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Population Reference Bureau. (2017). 2017 World Population Data Sheet. Retrieved from Washington, DC: [Google Scholar]

- Rogawski McQuade ET, Clark S, Bayo E, Scharf RJ, DeBoer MD, Patil CL, … Mduma ER (2019). Seasonal Food Insecurity in Haydom, Tanzania, Is Associated with Low Birthweight and Acute Malnutrition: Results from the MAL-ED Study. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, tpmd180547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheper-Hughes N (1993). Death without weeping: The violence of everyday life in Brazil: Univ of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sennott C, & Yeatman S (2012). Stability and change in fertility preferences among young women in Malawi. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 38(1), 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speizer IS, Calhoun LM, Hoke T, & Sengupta R (2013). Measurement of unmet need for family planning: longitudinal analysis of the impact of fertility desires on subsequent childbearing behaviors among urban women from Uttar Pradesh, India. Contraception, 88(4), 553–560. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staveteig S (2017). Fear, opposition, ambivalence, and omission: Results from a follow-up study on unmet need for family planning in Ghana. PLoS One, 12(7), e0182076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzania Ministry of Health. (2016). Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey (TDHS-MIS) 2015–16. Retrieved from Dar es Salaam, Tanzania and Rockville, Maryland, USA: [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2006). Child Growth Standards: Methods and Development. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/Technical_report.pdf

- Yeatman S, Sennott C, & Culpepper S (2013). Young women’s dynamic family size preferences in the context of transitioning fertility. Demography, 50(5), 1715–1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]