Abstract

Hormone therapy improves sleep in menopausal women and recent data suggest that transdermal 17β-estradiol may reduce the accumulation of cortical amyloid-β. However, how menopausal hormone therapies modify the associations of amyloid-β accumulation with sleep quality is not known. In this study, associations of sleep quality with cortical amyloid-β deposition and cognitive function were assessed in a subset of women who had participated in the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS). KEEPS was a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in which recently menopausal women (age=42–58; 5–36 months past menopause) were randomized to: 1) oral conjugated equine estrogen (oCEE, n=19); 2) transdermal 17β-estradiol (tE2, n=21); 3) placebo pills and patch (n=32) for 4 years. Global sleep quality score was calculated using Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, cortical amyloid-β deposition was measured with Pittsburgh compound-B (PiB) PET standard uptake value ratio (SUVr) and cognitive function was assessed in four cognitive domains three years after completion of trial treatments. Lower global sleep quality score (i.e. better sleep quality) correlated with lower cortical PiB SUVr only in the tE2 group (r=0.45, p=0.047). Better global sleep quality also correlated with higher visual attention and executive function scores in the tE2 group (r=−0.54, p=0.02) and in the oCEE group (r=−0.65, p=0.005). Menopausal hormone therapies may influence the effects of sleep on cognitive function, specifically, visual attention and executive function. There also appears to be a complex relationship between sleep, menopausal hormone therapies, cortical amyloid-β accumulation and cognitive function, and tE2 formulation may modify the relationship between sleep and amyloid-β accumulation.

Keywords: sleep, amyloid-β, cognition, estrogen, menopause

Introduction

During perimenopause and early postmenopause, initiating and maintaining sleep are the most common complaints of women [1]. Whereas aging and menopause negatively affect sleep quality, menopausal hormone therapies (mHT) improve sleep quality both in mice [2, 3] and humans [4–8]. Sleep disturbances are associated with cognitive dysfunction and neurodegeneration [9–11]. In rodents, sleep deprivation has shown to impair cognitive function [12–14]. Animal studies have also shown that the disruption of sleep-wake cycle is closely associated with amyloid-β deposition [15, 16]. A relationship between poor sleep quality and greater Alzheimer’s disease (AD) amyloid-β pathology has been detected with higher cortical amyloid-β deposition on PET in humans [17–24]. However, there is lack of data in postmenopausal women, and little is known about how mHT might affect this association.

The Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS), a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, compared effects of oral conjugated equine estrogen (oCEE) and transdermal 17β-estradiol (tE2) to placebo [25]. Sleep quality improved with both mHT compared to placebo [26]. In addition, women who received tE2 had lower cortical amyloid-β deposition on PET compared to placebo [27], while there were no differences in global cognitive function among any of the groups.

The relationship of sleep quality with amyloid-β deposition and cognition in the context of mHT in postmenopausal women has not been defined. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the association of self-reported sleep quality with cortical amyloid-β deposition and cognitive function in women who participated in KEEPS three years after completion of mHT.

Methods

Participants and study design

KEEPS was a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, multisite (9 institutions) clinical trial to assess the effects of two mHT on development of atherosclerosis as defined by increases in carotid intima-medial thickness. KEEPS included 727 women between the ages of 42 to 58 years within 36 months from menopause, who had no prior cardiovascular disease events before mHT. The study design and methods have been previously described in detail [25]. 118 women were randomized at the Mayo Clinic and 95 participated in the longitudinal KEEPS Neuroimaging Ancillary Study [27]. The KEEPS study was approved by Institutional Review Boards of each institution. Participants were randomized to either placebo pills and patch or oCEE (Premarin, 0.45 mg/d) or tE2 (Climara, 50 μg/d) for 4 years. Women in the active treatment groups were also administered oral micronized progesterone (Prometrium, 200 mg) 12 days each month. KEEPS participants at the Mayo Clinic site were invited to participate in an amyloid-β Pittsburgh compound-B (PiB) PET study three years after the end of mHT, which corresponded to 7 years from the enrollment time point. Of the 95 participants of the longitudinal KEEPS Neuroimaging Ancillary Study, 72 participated in the current study conducted 7 year after enrollment.

Study parameters-outcomes

MRI and PET Imaging:

All participants underwent MRI at 1.5 Tesla (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). A 3-dimensional (3D) T1-weighted sequence was performed for anatomical segmentation and labeling of PiB PET scans.

A PET/CT scanner (DRX; GE Healthcare) operating in 3D mode was used for PiB PET imaging. After the participants were injected with an average of 596 MBq PiB, a 40-minute uptake period was followed by acquisition of four 5-minute dynamic frames. A fully automated image processing pipeline was used to perform quantitative analysis. Global cortical PiB retention standard uptake value ratio (SUVr) was obtained from the PiB uptake in bilateral parietal, temporal, prefrontal, orbitofrontal, anterior cingulate, posterior cingulate and precuneus gray matter regions that were referenced to cerebellar gray matter PiB uptake [28].

Sleep quality:

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [29] was administered to investigate sleep quality within 6 weeks of imaging and neuropsychological testing. PSQI is a 19-item self-reported questionnaire. Questions are combined to form 7 component scores each ranging from 0 to 3 points. A score of 0 indicates no difficulty and a score of 3 indicates severe difficulty. The 7 sleep components are: 1) sleep satisfaction, 2) sleep latency, 3) sleep duration, 4) habitual sleep efficiency, 5) sleep disturbances, 6) use of sleeping medications and 7) daytime dysfunction. The 7 components are summed to calculate global PSQI sleep quality score ranging from 0 to 21. Lower PSQI score corresponds to better sleep quality. Based on prior literature, participants with a global PSQI score of >5 are defined as having poor sleep quality [29].

Cognitive function:

Cognitive function was characterized as four cognitive domain scores at year 7 [30]. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to derive summary scores [31]. Using a comprehensive battery of 11 subscale cognitive tests, the CFA produced four cognitive domain scores: verbal learning and memory, auditory attention and working memory, visual attention and executive function, and speeded language and mental flexibility [30].

Statistical analysis

Participants’ characteristics (age, education, APOE ε4 carrier status, global sleep quality and cognitive function) were compared among oCEE, tE2 and placebo groups using analysis of variance for continuous variables and using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables followed by Tukey Honest Significant differences for pairwise group comparisons where appropriate. Pearson’s correlations were used to test the associations of cortical PiB SUVr or cognitive test scores with sleep quality PSQI scores within each treatment group. Scatterplots and histograms were visually examined to assess the validity of assumptions (normality, homoscedasticity, linearity, and lack of outliers) for the correlations, and sensitivity analyses were performed with and without potentially influential observations. Linear models with APOE ε4 interaction terms were used to assess whether or not associations of sleep scores with PiB and cognitive domain scores differed by APOE ε4 carrier status. Significant interactions would indicate a significant difference. All tests used an alpha level of 0.05 for significance.

Results

Seventy-two women who participated in KEEPS at the Mayo Clinic had cognitive function testing and PSQI, and 68 underwent amyloid-β PiB PET at year 7. Age, education, cognitive performance and global PSQI scores were not different among the groups. While APOE ε4 carrier status did not differ among the groups (p=0.07), women in the tE2 group had a trend of higher proportion of APOE ε4 carriers compared to placebo (p=0.05). Mean global PSQI score was 5.15 (SD=3.23, median=5, IQR 3–7) and 36% of the entire group had poor sleep quality (global PSQI score>5). (Table 1)

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| oCEE | tE2 | Placebo | F | Degrees | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 19) | (n = 21) | (n = 32) | Stat | of freedom | ||

| Age at Year 7 (mean±SD) | 61 (3) | 60 (3) | 60 (2) | 0.36 | 2, 69 | 0.70 |

| Education, n (%) | 0.44 | |||||

| High school or less | 1 (6%) | 1 (5%) | 3 (9%) | |||

| Some college/college graduate | 14 (82%) | 12 (63%) | 18 (56%) | |||

| Some graduate/graduate | 2 (12%) | 6 (32%) | 11 (34%) | |||

| APOE carrier, n (%) | 3 (16%) | 9 (45%) | 5 (17%) | 0.07 | ||

| Sleep quality - Global PSQI score (Year 7) (mean±SD) | 5.63 (4.13) | 5.10 (2.51) | 4.91 (3.11) | 0.30 | 2, 69 | 0.74 |

| Cognitive function (Year 7) (mean±SD) | ||||||

| Verbal learning/memory | −0.81 (1.90) | 0.27 (1.88) | 0.25 (2.21) | 1.93 | 2, 68 | 0.15 |

| Auditory attention/working memory | −0.33 (0.99) | 0.18 (1.06) | 0.11 (1.20) | 1.25 | 2, 68 | 0.29 |

| Visual attention/executive function | −0.03 (1.27) | −0.26 (1.25) | 0.00 (1.09) | 0.33 | 2, 64 | 0.72 |

| Speeded language/mental flexibility | 0.23 (1.77) | −0.06 (1.65) | −0.09 (1.37) | 0.27 | 2, 68 | 0.76 |

| Cortical PiB SUVr on PET | 1.39 (0.17) | 1.36 (0.15) | 1.36 (0.06) | 0.50 | 2, 63 | 0.61 |

P-values between all groups are from Analysis of Variance for continuous variables or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. oCEE: oral conjugated equine estrogen; tE2: transdermal 17β-estradiol

In the entire group, there was no association between global sleep quality and cortical PiB SUVr on PET (r=0.19, p=0.13). Although marginally significant, only in the tE2 group, lower global PSQI scores (i.e. better global sleep quality) correlated with lower global cortical PiB SUVr on PET (r=0.45, p=0.047). There was no statistically significant relationship between separate components of the PSQI and cortical PiB SUVr in any of the groups.

In the entire group, among the four cognitive domains, only higher visual attention and executive function scores associated with better global sleep quality (r=−0.35, p=0.003). Similarly, only higher visual attention-executive scores correlated with better global sleep quality in the tE2 group (r=−0.54, p=0.02) and in the oCEE group (r=−0.65, p=0.005), but not in the placebo group. (Table 2) None of the cognitive domain scores correlated with cortical PiB SUVr in tE2, oCEE or placebo groups.

Table 2.

Association of sleep quality with cortical amyloid-β deposition and cognitive function

| All | oCEE | tE2 | Placebo | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R (p) | t Stat | DF | R (p) | t Stat | DF | R (p) | t Stat | DF | R (p) | t Stat | DF | |

| Verbal learning & memory | −0.23 (0.06) | −1.92 | 69 | −0.24 (0.32) | −1.03 | 17 | −0.05 (0.81) | −0.24 | 19 | −0.28 (0.13) | −1.54 | 29 |

| Auditory attention & working memory | −0.09 (0.46) | −0.74 | 69 | −0.12 (0.64) | −0.48 | 17 | −0.18 (0.43) | −0.81 | 19 | −0.004 (0.98) | −0.02 | 29 |

| Visual attention & executive function | −0.35 (0.003) | −3.05 | 65 | −0.65 (0.005) | −3.30 | 15 | −0.54 (0.02) | −2.69 | 18 | −0.02 (0.91) | −0.11 | 28 |

| Speeded language & mental flexibility | −0.07 (0.57) | −0.56 | 69 | 0.10 (0.68) | 0.42 | 17 | −0.06 (0.81) | −0.24 | 19 | −0.27 (0.14) | −1.53 | 29 |

| PiB SUVRs | 0.19 (0.13) | 1.55 | 64 | 0.18 (0.48) | 0.72 | 15 | 0.45 (0.047) | 2.14 | 18 | −0.08 (0.67) | −0.43 | 27 |

P-values are from Pearson’s correlations between PSQI scores and imaging/cognitive function domains at year 7. DF: degrees of freedom; oCEE: oral conjugated equine estrogen; tE2: transdermal 17β-estradiol

Because APOE ε4 carrier status differed between the tE2 and placebo groups (p=0.05), we investigated whether APOE ε4 carrier status modified the correlations between sleep quality and global cortical PiB SUVr or cognitive function. However, there was no interaction with APOE ε4 carrier status in any of the significant correlations in Table 2. The correlation between PSQI and PiB SUVr was not significant in APOE ε4 carrier positive (r=0.25, p=0.33) or negative (r=0.15, p=0.32) women. Similarly, the correlation between PSQI and visual attention-executive function was not significant in APOE ε4 carrier positive (r=−0.47, p=0.07) or negative (r=−0.29, p=0.05) women.

Discussion

At the year 7 follow-up of the KEEPS, we made several observations on the relationship between sleep quality and amyloid-β pathology as well as the potential influence of mHT on this relationship. Better global sleep quality associated with higher visual attention-executive function scores in the entire group of participants, but this association was driven completely by the tE2 and oCEE mHT groups. Only in the tE2 group, better sleep quality associated with lower cortical amyloid-β deposition on PET.

Sleep disorders increase with aging, with greater daytime sleepiness and fragmented sleep [32]. Regardless of sex, older adults present with increased wakefulness, reduced deep sleep and worse sleep consolidation [33], Chronic short sleep and sleep disruption are associated with neurodegeneration and are risk factors for AD [9–11]. Sleep quality also decreases during menopausal transition. During perimenopause and early postmenopause, 40 to 60% of women report problems sleeping [34]. This perception of poor sleep quality often is related to delayed sleep latency (time to sleep onset) and early awakenings [35]. Ovarian hormone fluctuations may influence menopausal sleep quality either directly or through perimenopause-related vasomotor symptoms such as hot flashes, perimenopause-related emotional status and concurrent sleep disorders [35].

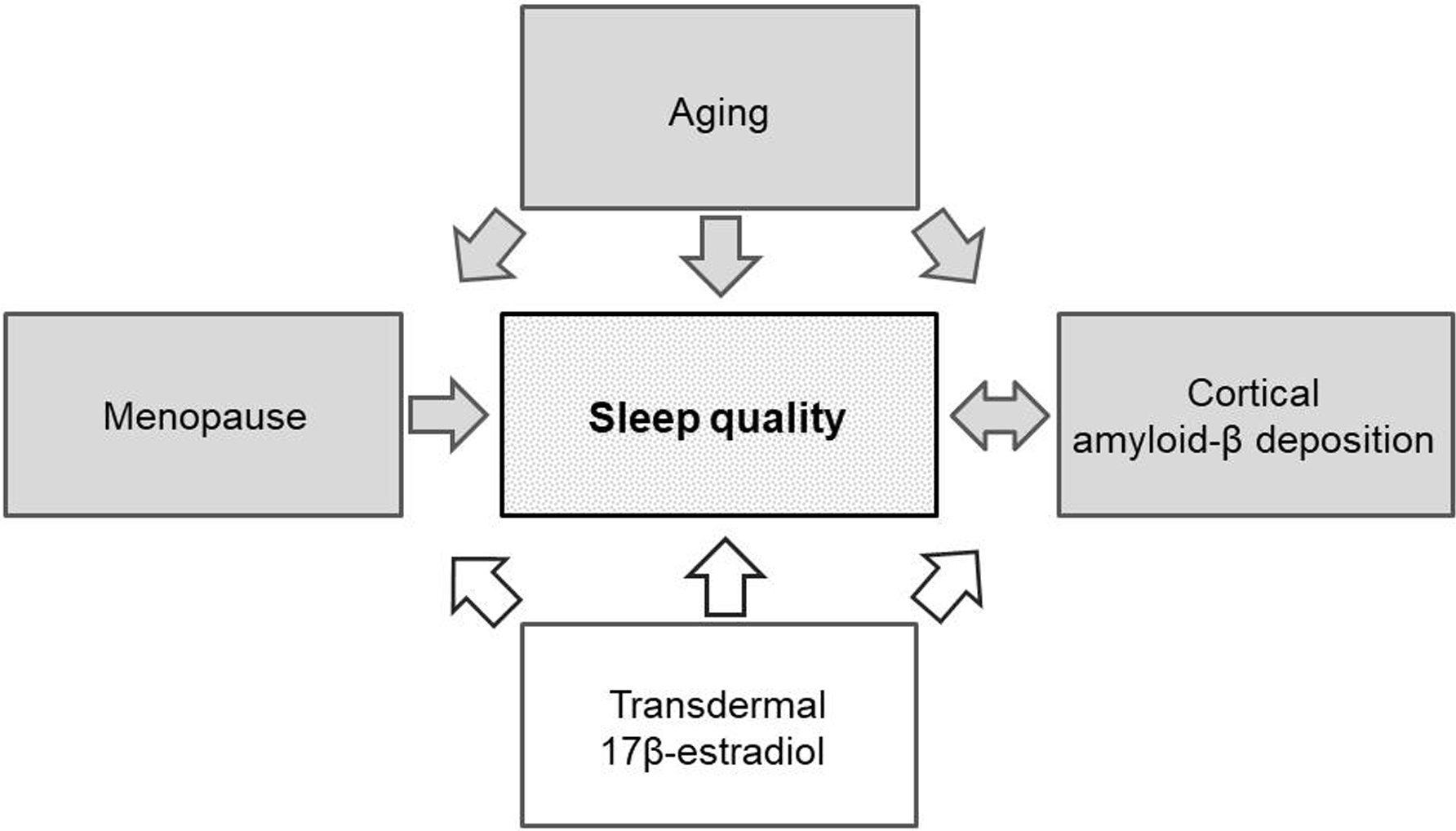

Poor sleep quality is also associated with cognitive impairment and increased risk of AD [36–40]. One of the earliest pathologic changes associated with AD is amyloid-β deposition, which can be measured with PET imaging [41, 42]. Global cortical PiB SUVr measure on PET includes a set of brain regions that are more likely to be affected earlier and more profoundly than other regions by the AD amyloid-β pathology [28]. In experimental animals, increased amyloid-β plaque formation was associated with chronic sleep deprivation and disrupted sleep-wake cycle [15, 16]. In cognitively unimpaired older adults, higher amyloid-β deposition correlated with poor sleep quality, shorter sleep duration and longer sleep latency [17–20]. Excessive daytime sleepiness was also associated with amyloid-β accumulation in older adults without dementia [21]. These findings are consistent with the concept that the toxic waste products such as amyloid-β, which accumulate during wakefulness, may be successfully removed during sleep. However, the relationship between sleep and AD amyloid-β pathology appears to be bi-directional (Figure 1), as sleep disturbances may lead to increase in amyloid-β production and decrease in amyloid-β clearance, and in return the accumulation of amyloid-β leads to more sleep disturbances [43]. The finding of a significant association between better sleep quality and lower cortical amyloid-β deposition on PET in the current study is consistent with these studies. However, this was observed only in women who had been randomized to tE2. It has been shown that 17β-estradiol regulates amyloid-β levels by modulating the production of amyloid-β and promoting the clearance of amyloid-β [44]. Furthermore, 17β-estradiol is associated with precluding the amyloid-β production by non-amyloidogenic processing of soluble amyloid precursor protein [45] and it also increases amyloid-β clearance by microglial internalization [46], suggesting that tE2 formulation may modify the relationship between sleep and cortical amyloid-β accumulation by enhancing amyloid-β clearance.

Figure 1. Relationships between aging, menopause, sleep quality, cortical amyloid-β deposition and transdermal 17β-estradiol.

Aging is a risk factor for sleep disturbances and poor sleep quality. Menopause influences sleep quality mostly due to ovarian hormone deficiencies during the perimenopausal and early menopausal period. There is a bi-directional relationship between poor sleep quality and higher cortical amyloid-β deposition. Transdermal 17β-estradiol potentially modifies the relationship between sleep quality and cortical amyloid-β deposition during perimenopause and early menopause. Gray arrows represent potential risk factors and white arrows represent potential beneficial effects based on the associations identified in the earlier studies and the current study [4–8, 17–22, 26, 27, 43].

Sleep quality improves with mHT [4–8]. This improvement may partially be due to the effective control of vasomotor symptoms [47]. In the KEEPS trial, improvement in sleep quality was observed in both oCEE and tE2 mHT groups over the 4 year treatment period and these effects were mostly mediated through symptom relief, especially through the alleviation of vasomotor symptoms [26]. Additionally, while global sleep quality was improved with both mHT, tE2 was modestly more efficacious compared to oCEE as it performed better in controlling sleep disturbances [26]. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that women who were treated with tE2 had lower global cortical PiB uptake, particularly if they were APOE ε4 carriers, without any differences in cognitive function between the groups [27]. In line with this, the relationship between better sleep quality and lower cortical amyloid-β deposition was observed only in the tE2 group in the current study. However, the relationship between better sleep quality and lower cortical amyloid-β deposition in the tE2 group should be evaluated cautiously. Although APOE ε4 carrier status frequency was not statistically different between the groups, given the modest sample size, the higher frequency of APOE ε4 carrier status in the tE2 group might still have a confounding effect on this relationship.

A clear relationship between sleep and cognitive function has been shown in previous studies. In cognitively unimpaired older adults, poor sleep quality was associated with lower cognitive function [36, 48, 49]. In older women, longer sleep latency correlated with higher risk of cognitive impairment [49]. Moreover, in older women, mHT seemed to have a modest effect on verbal memory [50–52]. In the current study, poor sleep quality was associated only with worse visual attention and executive function, and only in the mHT groups. Since the study participants were relatively younger (mean age 60) and healthier without any cardiovascular comorbidities or dementia and had a relatively low amyloid-β load, it seems like sleep disturbances were affecting visual attention and executive function before affecting other domains. This finding may not be surprising, because attentional networks are highly sensitive to sleep problems [53]. Furthermore, alertness, attention and vigilance start to alter with insufficient sleep [54] and executive function can be easily affected by poor sleep quality in older adults [55]. This association of poor sleep quality and lower visual attention and executive function was only observed in the mHT groups, suggesting that mHT are modulating the effect of sleep on cognitive function in postmenopausal women.

mHT used by recently menopausal women, may modify the risk of AD by preventing or delaying AD onset [56–63]. Although this was a small sample in a cross-sectional study, the association of better sleep quality and lower cortical amyloid-β deposition only existing in the tE2 group but not the oCEE group deserves attention. This might be due to the difference in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics between the two formulations and administration routes for tE2 and CEE. Moreover, this association was detectable 7 years after randomization (3 years after the treatment discontinuation) indicating that mHT may have long-term effects on the brain cortical amyloid-β deposition and its relationship with sleep and cognitive function.

It is difficult to establish definite causal relationships as there are complex relationships between sleep, aging, menopause, ovarian hormones, cognitive function and cortical amyloid-β accumulation. Although the ongoing relationships are both multi-directional and multi-factorial, these data provide support for larger prospective studies to evaluate these associations. If the associations are confirmed, better management of sleep and the choice of mHT could be modifiable candidates with potential public health implications. (Figure 1)

Funding:

Kronos Longevity Research Institute (Dr. Harman), NIH (NIA RF1 AG057547- Dr. Kantarci and Gleason, NIA U54 AG44170- Drs. Miller and Mielke, NS66147 Dr. Kantarci)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Disclosures: Burcu Zeydan receives research support from the NIH. Val J. Lowe serves is a consultant for Bayer Schering Pharma, AVID Radiopharmaceuticals, Piramal Imaging and GE Healthcare and receives research support from GE Healthcare, Siemens Molecular Imaging, AVID Radiopharmaceuticals, the NIH (NIA, NCI), and the MN Partnership for Biotechnology and Medical Genomics. Matthew L. Senjem discloses equity/options ownership in medical companies: Gilead Sciences Inc., Inovio Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, and PAREXEL International Corporation. Clifford R. Jack, Jr. serves on an independent data monitoring board for Roche and has consulted for Eisai, but he receives no personal compensation from any commercial entity. He receives research support from NIH and the Alexander Family Alzheimer’s Disease Research Professorship of the Mayo Clinic. Julie A. Fields receives research support from the NIH. Kejal Kantarci serves on data safety monitoring board for Takeda Global Research and Development Center, Inc, receives research support from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals and Eli Lilly, and receives funding from the NIH and Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation. Nirubol Tosakulwong, Timothy G. Lesnick, Taryn T. James, Carey E. Gleason, N. Maritza Dowling and Virginia M. Miller report no disclosures.

References

- [1].Jehan S, Masters-Isarilov A, Salifu I, Zizi F, Jean-Louis G, Pandi-Perumal SR, Gupta R, Brzezinski A, McFarlane SI (2015) Sleep Disorders in Postmenopausal Women. J Sleep Disord Ther 4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Paul KN, Dugovic C, Turek FW, Laposky AD (2006) Diurnal sex differences in the sleep-wake cycle of mice are dependent on gonadal function. Sleep 29, 1211–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Paul KN, Laposky AD, Turek FW (2009) Reproductive hormone replacement alters sleep in mice. Neurosci Lett 463, 239–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Keefe DL, Watson R, Naftolin F (1999) Hormone replacement therapy may alleviate sleep apnea in menopausal women: a pilot study. Menopause 6, 196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Welton AJ, Vickers MR, Kim J, Ford D, Lawton BA, MacLennan AH, Meredith SK, Martin J, Meade TW, team W (2008) Health related quality of life after combined hormone replacement therapy: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 337, a1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Polo-Kantola P (2011) Sleep problems in midlife and beyond. Maturitas 68, 224–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Stuenkel CA, Davis SR, Gompel A, Lumsden MA, Murad MH, Pinkerton JV, Santen RJ (2015) Treatment of Symptoms of the Menopause: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100, 3975–4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].de Villiers TJ, Hall JE, Pinkerton JV, Perez SC, Rees M, Yang C, Pierroz DD (2016) Revised global consensus statement on menopausal hormone therapy. Maturitas 91, 153–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pase MP, Himali JJ, Grima NA, Beiser AS, Satizabal CL, Aparicio HJ, Thomas RJ, Gottlieb DJ, Auerbach SH, Seshadri S (2017) Sleep architecture and the risk of incident dementia in the community. Neurology 89, 1244–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kang DW, Lee CU, Lim HK (2017) Role of Sleep Disturbance in the Trajectory of Alzheimer’s Disease. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci 15, 89–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lutsey PL, Misialek JR, Mosley TH, Gottesman RF, Punjabi NM, Shahar E, MacLehose R, Ogilvie RP, Knopman D, Alonso A (2018) Sleep characteristics and risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Alzheimers Dement 14, 157–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hagewoud R, Havekes R, Novati A, Keijser JN, Van der Zee EA, Meerlo P (2010) Sleep deprivation impairs spatial working memory and reduces hippocampal AMPA receptor phosphorylation. J Sleep Res 19, 280–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Walsh CM, Booth V, Poe GR (2011) Spatial and reversal learning in the Morris water maze are largely resistant to six hours of REM sleep deprivation following training. Learn Mem 18, 422–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Heckman PRA, Roig Kuhn F, Meerlo P, Havekes R (2020) A brief period of sleep deprivation negatively impacts the acquisition, consolidation, and retrieval of object-location memories. Neurobiol Learn Mem 175, 107326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kang JE, Lim MM, Bateman RJ, Lee JJ, Smyth LP, Cirrito JR, Fujiki N, Nishino S, Holtzman DM (2009) Amyloid-beta dynamics are regulated by orexin and the sleep-wake cycle. Science 326, 1005–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Roh JH, Huang Y, Bero AW, Kasten T, Stewart FR, Bateman RJ, Holtzman DM (2012) Disruption of the sleep-wake cycle and diurnal fluctuation of beta-amyloid in mice with Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Sci Transl Med 4, 150ra122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Spira AP, Gamaldo AA, An Y, Wu MN, Simonsick EM, Bilgel M, Zhou Y, Wong DF, Ferrucci L, Resnick SM (2013) Self-reported sleep and beta-amyloid deposition in community-dwelling older adults. JAMA Neurol 70, 1537–1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mander BA, Marks SM, Vogel JW, Rao V, Lu B, Saletin JM, Ancoli-Israel S, Jagust WJ, Walker MP (2015) beta-amyloid disrupts human NREM slow waves and related hippocampus-dependent memory consolidation. Nat Neurosci 18, 1051–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sprecher KE, Bendlin BB, Racine AM, Okonkwo OC, Christian BT, Koscik RL, Sager MA, Asthana S, Johnson SC, Benca RM (2015) Amyloid burden is associated with self-reported sleep in nondemented late middle-aged adults. Neurobiol Aging 36, 2568–2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Brown BM, Rainey-Smith SR, Villemagne VL, Weinborn M, Bucks RS, Sohrabi HR, Laws SM, Taddei K, Macaulay SL, Ames D, Fowler C, Maruff P, Masters CL, Rowe CC, Martins RN, Group AR (2016) The Relationship between Sleep Quality and Brain Amyloid Burden. Sleep 39, 1063–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Carvalho DZ, St Louis EK, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Lowe VJ, Roberts RO, Mielke MM, Przybelski SA, Machulda MM, Petersen RC, Jack CR Jr., Vemuri P (2018) Association of Excessive Daytime Sleepiness With Longitudinal beta-Amyloid Accumulation in Elderly Persons Without Dementia. JAMA Neurol 75, 672–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sharma RA, Varga AW, Bubu OM, Pirraglia E, Kam K, Parekh A, Wohlleber M, Miller MD, Andrade A, Lewis C, Tweardy S, Buj M, Yau PL, Sadda R, Mosconi L, Li Y, Butler T, Glodzik L, Fieremans E, Babb JS, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Lu SE, Badia SG, Romero S, Rosenzweig I, Gosselin N, Jean-Louis G, Rapoport DM, de Leon MJ, Ayappa I, Osorio RS (2018) Obstructive Sleep Apnea Severity Affects Amyloid Burden in Cognitively Normal Elderly. A Longitudinal Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 197, 933–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Shokri-Kojori E, Wang GJ, Wiers CE, Demiral SB, Guo M, Kim SW, Lindgren E, Ramirez V, Zehra A, Freeman C, Miller G, Manza P, Srivastava T, De Santi S, Tomasi D, Benveniste H, Volkow ND (2018) beta-Amyloid accumulation in the human brain after one night of sleep deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, 4483–4488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Holth JK, Fritschi SK, Wang C, Pedersen NP, Cirrito JR, Mahan TE, Finn MB, Manis M, Geerling JC, Fuller PM, Lucey BP, Holtzman DM (2019) The sleep-wake cycle regulates brain interstitial fluid tau in mice and CSF tau in humans. Science 363, 880–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Harman SM, Brinton EA, Cedars M, Lobo R, Manson JE, Merriam GR, Miller VM, Naftolin F, Santoro N (2005) KEEPS: The Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study. Climacteric 8, 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Cintron D, Lahr BD, Bailey KR, Santoro N, Lloyd R, Manson JE, Neal-Perry G, Pal L, Taylor HS, Wharton W, Naftolin F, Harman SM, Miller VM (2018) Effects of oral versus transdermal menopausal hormone treatments on self-reported sleep domains and their association with vasomotor symptoms in recently menopausal women enrolled in the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS). Menopause 25, 145–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kantarci K, Lowe VJ, Lesnick TG, Tosakulwong N, Bailey KR, Fields JA, Shuster LT, Zuk SM, Senjem ML, Mielke MM, Gleason C, Jack CR, Rocca WA, Miller VM (2016) Early Postmenopausal Transdermal 17beta-Estradiol Therapy and Amyloid-beta Deposition. J Alzheimers Dis 53, 547–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Jack CR Jr., Lowe VJ, Senjem ML, Weigand SD, Kemp BJ, Shiung MM, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Petersen RC (2008) 11C PiB and structural MRI provide complementary information in imaging of Alzheimer’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Brain : a journal of neurology 131, 665–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ (1989) The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 28, 193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gleason CE, Dowling NM, Wharton W, Manson JE, Miller VM, Atwood CS, Brinton EA, Cedars MI, Lobo RA, Merriam GR, Neal-Perry G, Santoro NF, Taylor HS, Black DM, Budoff MJ, Hodis HN, Naftolin F, Harman SM, Asthana S (2015) Effects of Hormone Therapy on Cognition and Mood in Recently Postmenopausal Women: Findings from the Randomized, Controlled KEEPS-Cognitive and Affective Study. PLoS Med 12, e1001833; discussion e1001833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Dowling NM, Gleason CE, Manson JE, Hodis HN, Miller VM, Brinton EA, Neal-Perry G, Santoro MN, Cedars M, Lobo R, Merriam GR, Wharton W, Naftolin F, Taylor H, Harman SM, Asthana S (2013) Characterization of vascular disease risk in postmenopausal women and its association with cognitive performance. PLoS One 8, e68741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wolkove N, Elkholy O, Baltzan M, Palayew M (2007) Sleep and aging: 1. Sleep disorders commonly found in older people. CMAJ 176, 1299–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ameratunga D, Goldin J, Hickey M (2012) Sleep disturbance in menopause. Intern Med J 42, 742–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Moline ML, Broch L, Zak R, Gross V (2003) Sleep in women across the life cycle from adulthood through menopause. Sleep Med Rev 7, 155–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Shaver JL, Woods NF (2015) Sleep and menopause: a narrative review. Menopause 22, 899–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Tworoger SS, Lee S, Schernhammer ES, Grodstein F (2006) The association of self-reported sleep duration, difficulty sleeping, and snoring with cognitive function in older women. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 20, 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Akbaraly TN, Marmot MG, Kivimaki M, Singh-Manoux A (2011) Change in sleep duration and cognitive function: findings from the Whitehall II Study. Sleep 34, 565–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Xu L, Jiang CQ, Lam TH, Liu B, Jin YL, Zhu T, Zhang WS, Cheng KK, Thomas GN (2011) Short or long sleep duration is associated with memory impairment in older Chinese: the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study. Sleep 34, 575–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ju YE, Lucey BP, Holtzman DM (2014) Sleep and Alzheimer disease pathology--a bidirectional relationship. Nat Rev Neurol 10, 115–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Miller MA, Wright H, Ji C, Cappuccio FP (2014) Cross-sectional study of sleep quantity and quality and amnestic and non-amnestic cognitive function in an ageing population: the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). PLoS One 9, e100991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Jack CR Jr., Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Aisen PS, Weiner MW, Petersen RC, Trojanowski JQ (2010) Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade. Lancet Neurol 9, 119–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Iwatsubo T, Jack CR Jr., Kaye J, Montine TJ, Park DC, Reiman EM, Rowe CC, Siemers E, Stern Y, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Morrison-Bogorad M, Wagster MV, Phelps CH (2011) Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7, 280–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Wang C, Holtzman DM (2020) Bidirectional relationship between sleep and Alzheimer’s disease: role of amyloid, tau, and other factors. Neuropsychopharmacology 45, 104–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Pike CJ, Carroll JC, Rosario ER, Barron AM (2009) Protective actions of sex steroid hormones in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neuroendocrinol 30, 239–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Jaffe AB, Toran-Allerand CD, Greengard P, Gandy SE (1994) Estrogen regulates metabolism of Alzheimer amyloid beta precursor protein. J Biol Chem 269, 13065–13068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Harris-White ME, Chu T, Miller SA, Simmons M, Teter B, Nash D, Cole GM, Frautschy SA (2001) Estrogen (E2) and glucocorticoid (Gc) effects on microglia and A beta clearance in vitro and in vivo. Neurochem Int 39, 435–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Cintron D, Lipford M, Larrea-Mantilla L, Spencer-Bonilla G, Lloyd R, Gionfriddo MR, Gunjal S, Farrell AM, Miller VM, Murad MH (2017) Efficacy of menopausal hormone therapy on sleep quality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine 55, 702–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Nebes RD, Buysse DJ, Halligan EM, Houck PR, Monk TH (2009) Self-reported sleep quality predicts poor cognitive performance in healthy older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 64, 180–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Blackwell T, Yaffe K, Ancoli-Israel S, Redline S, Ensrud KE, Stefanick ML, Laffan A, Stone KL, Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study G (2011) Association of sleep characteristics and cognition in older community-dwelling men: the MrOS sleep study. Sleep 34, 1347–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Maki PM, Gast MJ, Vieweg AJ, Burriss SW, Yaffe K (2007) Hormone therapy in menopausal women with cognitive complaints: a randomized, double-blind trial. Neurology 69, 1322–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Grady D, Yaffe K, Kristof M, Lin F, Richards C, Barrett-Connor E (2002) Effect of postmenopausal hormone therapy on cognitive function: the Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study. Am J Med 113, 543–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Resnick SM, Maki PM, Rapp SR, Espeland MA, Brunner R, Coker LH, Granek IA, Hogan P, Ockene JK, Shumaker SA, Women’s Health Initiative Study of Cognitive Aging I (2006) Effects of combination estrogen plus progestin hormone treatment on cognition and affect. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91, 1802–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Hennawy M, Sabovich S, Liu CS, Herrmann N, Lanctot KL (2019) Sleep and Attention in Alzheimer’s Disease. Yale J Biol Med 92, 53–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Killgore WD (2010) Effects of sleep deprivation on cognition. Prog Brain Res 185, 105–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Bernstein JPK, Calamia M, Keller JN (2018) Multiple self-reported sleep measures are differentially associated with cognitive performance in community-dwelling nondemented elderly. Neuropsychology 32, 220–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Paganini-Hill A, Henderson VW (1994) Estrogen deficiency and risk of Alzheimer’s disease in women. Am J Epidemiol 140, 256–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Waring SC, Rocca WA, Petersen RC, O’Brien PC, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E (1999) Postmenopausal estrogen replacement therapy and risk of AD: a population-based study. Neurology 52, 965–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Rocca WA, Grossardt BR, Shuster LT (2014) Oophorectomy, estrogen, and dementia: a 2014 update. Mol Cell Endocrinol 389, 7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Sherwin BB, Henry JF (2008) Brain aging modulates the neuroprotective effects of estrogen on selective aspects of cognition in women: a critical review. Front Neuroendocrinol 29, 88–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Henderson VW, Benke KS, Green RC, Cupples LA, Farrer LA, Group MS (2005) Postmenopausal hormone therapy and Alzheimer’s disease risk: interaction with age. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76, 103–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Whitmer RA, Quesenberry CP, Zhou J, Yaffe K (2011) Timing of hormone therapy and dementia: the critical window theory revisited. Ann Neurol 69, 163–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Maki PM (2013) Critical window hypothesis of hormone therapy and cognition: a scientific update on clinical studies. Menopause 20, 695–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Brinton RD (2009) Estrogen-induced plasticity from cells to circuits: predictions for cognitive function. Trends Pharmacol Sci 30, 212–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]