Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cells are endowed with germline-encoded receptors that enable them to detect and kill malignant cells without prior priming. Over the years, overwhelming evidence has identified an essential role for NK cells in tumor immune surveillance. More recently, clinical trials have also highlighted their potential in therapeutic settings. Yet, data show that NK cells can be dysregulated within the tumor microenvironment (TME), rendering them ineffective in eradicating the cancer cells. This has been attributed to immune suppressive factors, including the tumor cells per se, stromal cells, regulatory T cells, and soluble factors such as reactive oxygen species and cytokines. However, the TME also hosts myeloid cells such as dendritic cells, macrophages, neutrophils, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells that influence NK cell function. Although the NK-myeloid cell crosstalk can promote anti-tumor responses, myeloid cells in the TME often dysregulate NK cells via direct cell-to-cell interactions down-regulating key NK cell receptors, depletion of nutrients and growth factors required for NK cell growth, and secretion of metabolites, chemokines and cytokines that ultimately alter NK cell trafficking, survival, and cytotoxicity. Here, we review the complex functions of myeloid-derived cytokines in both supporting and suppressing NK cells in the TME and how NK cell-derived cytokines can influence myeloid subsets. We discuss challenges related to these interactions in unleashing the full potential of endogenous and adoptively infused NK cells. Finally, we present strategies aiming at improving NK cell-based cancer immunotherapies via pathways that are involved in the NK-myeloid cell crosstalk in the TME.

Keywords: natural killer (NK) cells; myeloid cells; cytokines; tumor microenvironment; cancer immunotherapy, tumor immunity

Introduction

Natural Killer (NK) cells are cytotoxic lymphocytes that innately recognize their target cells based on signals from an array of germline-encoded inhibitory and activating cell surface receptors (1). While inhibition is mainly mediated by HLA class I-binding receptors such as KIR, LIR-1, and NKG2A, activation is triggered by the NKG2D, DNAM-1, NKp30, NKp46, and 2B4 receptors, among others (2). Experimental approaches delineating how NK cells target tumor cells have in more recent years been harmonized with studies evidencing their role in tumor immune surveillance (3) and clinical therapy to treat patients with cancer (4, 5). However, it has also become increasingly clear that NK cells are often dysfunctional in cancer patients (6, 7). This is most prominent in the tumor microenvironment (TME), although also observed in blood and other tissues in patients with advanced cancer (6–8). Factors suppressing endogenous or adoptively infused NK cells in the TME are likely limiting the full potential of NK cell-based cancer immunotherapies.

NK cells can be disarmed in the TME by both direct and indirect interactions with the tumor cells (6, 7, 9). However, several other cell types in the TME, such as stroma cells and immune cells, acting by direct interactions and via release of reactive oxygen species, growth factors, and cytokines, can also induce NK cell dysfunction (9–11). Both the degree and mode of NK cell suppression in the TME may dynamically vary from early to later stages of cancer development as well as between different tumor histotypes. Beyond reducing the anti-tumor cytotoxicity of NK cells per se, suppression of NK cells in the TME can also negatively impact their ability to recruit other immune cells (12–15), which is crucial for initiating and maintaining proper anti-tumor responses. In this regard, a pivotal interaction in the TME is the one between NK cells and myeloid cells, such as dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages, neutrophils, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) (16–19). While NK cells positively promote DC infiltration and maturation via release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interferon (IFN)-γ (20), myeloid-derived cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-12, IL-15, and IL-18, critically promote NK cell maturation, proliferation, and anti-tumor functions (21). However, aggravation of the TME often observed in more advanced stages of cancer direct myeloid cells towards a suppressive phenotype that instead can impede NK cell functions via secretion of cytokines, such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, IL-1β, and IL-10 (22–24). Thus, the NK-myeloid crosstalk is intricate but critical for proper anti-tumor properties of NK cells in the TME.

Here we give an overview of the cytokines involved in the interplay between NK cells and myeloid cells in the general TME. We discuss how myeloid cells promote NK cell functions and vice versa, but foremost, how this interaction can hinder NK cell-mediated tumor rejection. We outline current methods and possible future approaches to enhance anti-tumor responses by NK cells via administration or manipulation of cytokines and cytokine signaling, as well as preventing myeloid cell infiltration into the TME. This review highlights that a better understanding of the crosstalk between myeloid cells and NK cells is likely critical to improve the efficacy of NK cell-based cancer immunotherapy.

Myeloid-Derived Cytokines Promoting Natural Killer Cell Responses to Cancer

Several myeloid cells, exemplified by macrophages and DCs, are characterized by a pro-inflammatory phenotype and release cytokines such as type-1 IFNs, IL-12, IL-15, IL-18, IL-21 (Table 1A) upon recognition of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) on the transformed cells (70, 71). This pro-inflammatory cytokine milieu, together with key chemokines, aid in the recruitment of NK cells to the tumor site while promoting their persistence and anti-tumor effector functions (70, 72). Several of these cytokines have overlapping functions but also possess specific functions in the regulation of NK cell responses in cancer (35, 73–79) (Figure 1 and Table 1A). In this section, we will present the key cytokines released by myeloid cells that promote anti-tumor cytotoxicity by NK cells but also give examples of how cytokines can have dual functions.

Table 1.

Cytokines and chemokines involved in the NK-myeloid cell crosstalk and drugs directed to modulate these interactions.

| A. Myeloid cell-derived cytokines and their effects on NK cells. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokine | Produced by | Effects | Therapy | Ref. | |

| TGF-β | MDSCs, TAMs, tumor cells, mast cells | ↓activating receptor, cytokine production, cytotoxicity, proliferation | Fresolimumab, galunisertib, M7824 (clinical trial) | (25–30) | |

| IL-10 | MDSCs, TAMs, NK cells, DCs, macrophages | ↓/↑ cytotoxicity, cytokine production | – | (24, 31–33) | |

| IL-32α | DCs | ↓perforin, granzyme B | – | (34) | |

| TNF | Macrophages | ↑ cytokine production | – | (35) | |

| IL-12 | DCs, macrophages, monocytes, neutrophils | ↑ cytotoxicity, cytokine production, proliferation, survival | IL-12, IL-12 + pembrolizumab (clinical trial) | (21, 36) | |

| IL-15 | DCs, macrophages, monocytes | ↑ cytotoxicity, cytokine production, proliferation, survival, activating receptors, KIR | ALT-803 (phase 1 and 2 clinical trial), IL-15 + Ipilimumab and Nivolumab (phase 1 clinical trial) | (37–39) | |

| IL-18 | M0 macrophages, TAMs, DCs, | ↑ cytotoxicity, cytokine production, proliferation, survival | IL-18 (phase 1 and 2 clinical trial) | (40–44) | |

| IL-21 | DCs | ↑ cytotoxicity, proliferation, activating receptors | IL-21, IL-21 + Ipilimumab and nivolumab (phase-I and –II clinical trial) | (45) | |

| IL-6 | MDSC, TAM, tumor cell, macrophages, monocytes, mast cells | ↓/↑ cytotoxicity, ↓ cytokine production | Tocilizumab (clinical trial) | (46, 47) | |

| IL-1α | Monocytes, DCs, macrophages | ↓maturation | Anakinra, Canakinumab, Isunakinra (phase 1 and 2 clinical trial) | (23) | |

| IL-27 | DCs, macrophages, MDSCs | ↓/↑ cytotoxicity, cytokine production | p28 peptide | (48–53) | |

| IL-23 | MDSC and TAM, DC and macrophage | ↓/↑ cytotoxicity, cytokine production | – | (54, 55) | |

| IL-17 | Neutrophils | ↑cytotoxicity, ↓maturation | – | (56, 57) | |

| IFN-α/β | DC | ↑ cytotoxicity, cytokine production, proliferation, survival, NKG2D | IFN-α/β approved | (58) | |

| B. NK cell-derived cytokines and their effects on myeloid cells. | |||||

| Cytokine | Target population | Effects | Therapy | Ref. | |

| IFN-γ | DCs | maturation, activation | – | (59–61) | |

| TAMs | polarization towards pro-inflammatory Mφ | – | (62, 63) | ||

| TANs | inhibition of pro-tumorigenic TANs | – | (64) | ||

| TNF-α | DCs | maturation, activation | – | (59–61) | |

| TAMs | polarization towards pro-inflammatory Mφ | – | (62) | ||

| HMGB1 | DCs | activation | – | (43, 65) | |

| GM-CSF | DCs | activation | – | (62) | |

| TAMs | polarization towards pro-inflammatory Mφ | – | (62) | ||

| TANs | activation, promotes NETs | – | (66–68) | ||

| VEGF-A | Endothelial cells, tumor cells | proliferation, migration | – | (69) | |

A) Effects of myeloid cell-derived cytokines on NK cells and therapeutic targeting thereof. B) Effects of NK cell-derived cytokines on the maturation and differentiation of different myeloid cell subsets and therapeutic targeting thereof.

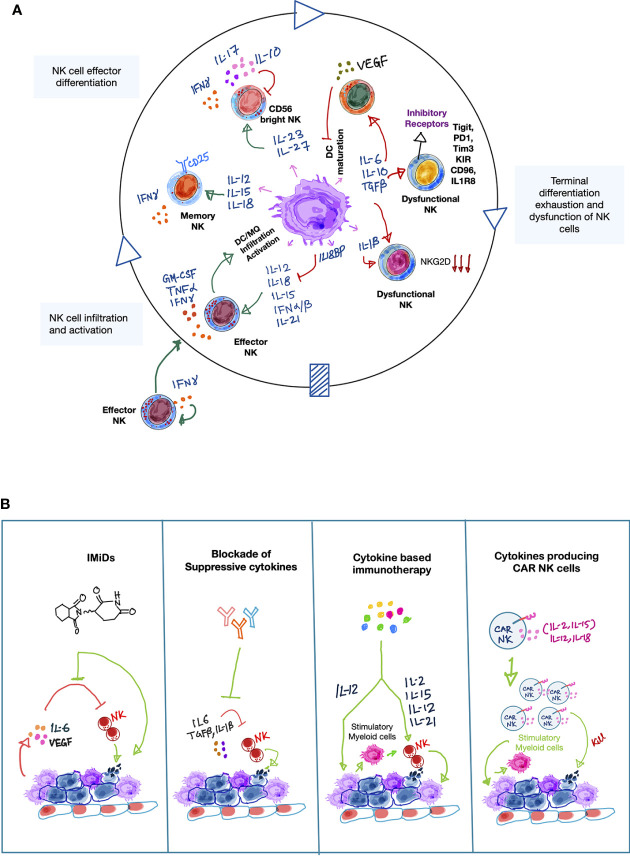

Figure 1.

Cytokines involved in the NK-myeloid cell cross talk in the tumor microenvironment. (A) A simplified schematic illustration showing the orchestra of myeloid- and NK cell-derived cytokines involved in forming anti-tumor immune responses by NK cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME). Activated NK cells produce IFN-γ which indirectly promotes recruitment of other NK cells from peripheral blood to the tumor sites. Upon recognition of tumor antigens, myeloid cells, especially DCs and macrophages produce inflammatory cytokines such as type-1 IFNs, IL-12, IL-15, IL-18, IL-21. These cytokines either alone or cooperatively promote NK cell survival, proliferation, maturation and production of spectrum of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IFN-γ, TNF-α, GM-CSF, which further boost anti-tumor immune-activating potential of myeloid cells while recruiting additional inflammatory myeloid cells [including M1 macrophages (MQ), mature dendritic cells (DCs)] to sustain the anti-tumor immune response. Furthermore, myeloid-derived IL-23 and IL-27 cytokines can also promote NK cell activity by inducing IFN-γ production, but they can also negatively influence the NK-myeloid cell anti-tumor crosstalk by secretion of tumor-promoting cytokines such as IL-17 and IL-10, respectively. This suggests a dual role of IL-23 and IL-27 in NK cell-mediated tumor immunity. In line with the dual roles of certain cytokines, myeloid cells can become immune suppressive (myeloid-derived suppressor cells; MDSCs). This is frequently occurring during cancer progression. MDSCs secrete a plethora of immune suppressive cytokines that negatively influence the anti-tumor potential of NK cells per se but also impair anti-tumor responses normally resulting from the NK-myeloid cell crosstalk. For example, suppressive cytokines promote NK cell exhaustion and directly impair NK cell-mediated cytolytic activity, while limiting the ability of myeloid cells to produce NK cell stimulatory cytokines such as IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18. Green arrows indicate positive interactions and red arrows indicate negative interactions. (B) Therapeutic approaches that directly or indirectly modulate cytokine mediators that enhance NK cell-mediated anti-cancer responses in the TME. Simplified illustrations showing validated therapeutic approaches that can either restore or reinforce a stimulatory cytokine environment to augment NK cell-mediated tumor killing activity. On one hand, immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) such as lenalidomide can indirectly augment NK cell anti-tumor activity by reducing the levels of pro-tumorigenic factors, such as IL-6 and VEGF, while stimulating other immune cells to secrete IL-2. Accordingly, targeted blockade of immune-suppressive cytokines, such as IL-6, TGF-β can also positively impact NK-myeloid anti-tumor cross-talk in a similar manner. On the other hand, recombinant or synthetic cytokines as well as cell-based therapies such as cytokine-secreting CAR-NK cells can directly influence NK cell-mediated cancer cell killing. Importantly, cytokine-activated NK cells can further edit myeloid cells to enhance anti-tumor response via the production of inflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-γ. Light green arrows show the mode of therapeutic action.

Direct and Indirect Contribution of Interferon-α and Interferon-β in Natural Killer Cell Activation

The type-1 IFNs, IFN-α, and IFN-β are secreted by activated myeloid cells and stimulate NK cell expansion while enhancing the effector functions upon stimulation of the IFN-α receptor (IFNAR) (80, 81). Inversely, as highlighted in experimental models using IFNAR-deficient NK cells and NK cells with defective downstream signaling molecule transducer and activator-1 (STAT1), impaired type-1 IFN signaling results in defective functional NK cell maturation and hampered anti-tumoricidal potential in sarcoma and lymphoma mouse models (82, 83). Importantly, while transient or intermittent type-1 IFN stimulation results in preferential phosphorylation of STAT4 than STAT1 and thereby increased IFN-γ production by NK cells promoting pro-inflammation, chronic stimulation coupled with increased levels of IFN-γ also bolster NK cell cytotoxicity (81, 84). This is due to increases basal levels of STAT1 protein expression following chronic IFN-γ stimulation that triggers preferential activation of STAT1 over STAT4 (81, 84). Additionally, autocrine type-1 IFN signaling in activated myeloid cells induces interleukin (IL)-15 production, which is a critical cytokine for NK cell development, proliferation and cytotoxic function (37, 85).

Regulation of Natural Killer Cell Activation and Effector Function by Interleukin-12 Family of Cytokines

The IL-12 family of heterodimeric cytokines, including IL-12, IL-23, and IL-27, critically regulate NK cell activation and effector functions (Figure 1A and Table 1A). Phagocytic macrophages and DCs produce these cytokines following the recognition of DAMPs on dying tumor cells. Despite sharing sequence similarly, these cytokines uniquely modulate NK cell function.

Interleukin-12

IL-12 (p35 and p40 complex) signals by engaging the heterodimeric receptor complex of IL-12Rβ1 and IL-12Rβ2 subunits that are readily expressed by mature activated but not immature NK cells. In NK cells, IL-12 signaling principally mediates STAT4 phosphorylation that is essential for both IFN-γ and perforin expression, as observed both in human NK cells in vitro and in murine NK cells in vivo (21, 86–89). Accordingly, blockade of IL-12 diminishes DC-induced IFN-γ production by NK cells, suggesting IL-12 is critical for optimal IFN-γ release by activated human NK cells (90). Additionally, IL-12 can work in concert with IL-15 and IL-18 to generate ‘memory-like’ NK cells, partly facilitated by epigenetic reprogramming of the CNS1 enhancer region of the Ifng locus in NK cells, which enables them to produce elevated levels of IFN-γ compared to conventional NK cells upon activation as shown by transferring IL-12/IL-15/IL-18-pretreated human NK cells in NSG mice (91).

Interleukin-23

IL-12p40 also interacts with p19 subunits forming the heterodimeric cytokine IL-23. Upon stimulation with IL-23, CD56bright NK cells release higher levels of IFN-γ as compared to CD56dim NK cells due to their higher expression levels of IL-23R. IL-23 also increases IL-18Rα expression, thus priming NK cells for IL-18-induced IFN-γ production. IL-23 stimulates human NK cell activation in vitro while inhibiting IL-15- and IL-18-induced NK cell proliferation (54). However, IL-23 reduces both cytotoxicity and IFN-γ production in vivo, indeed anti-IL-23 therapy synergizes with IL-2 or anti-erbB2 treatment in mammary and melanoma tumor models in an NK cell-dependent manner (55, 92).

Interleukin-27

The IL-27 heterodimer is composed of p28 and EBI3 and promotes pro- and anti-inflammatory functions mainly through STAT1 and STAT3 (93). Like IL-23, IL-27 shows differential activity on human CD56bright and CD56dim subsets, maybe related to the higher expression of IL-27Rα in the CD56bright subset (48). While CD56dim NK cells are not affected, CD56bright NK cells acquire a regulatory phenotype. Yet, in vivo studies on a murine squamous cell carcinoma model and in vitro analysis on human NK cells also demonstrated that IL-27 primes NK cells to respond to IL-18, while inducing perforin, granzyme B, NKp46, and NKG2D expression, as well as promoting antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) (49–52, 94, 95).

Critical Role of Gamma-Chain Cytokines Released by Myeloid Cells in Promoting Natural Killer Cell Survival, Proliferation, and Functions

The gamma-chain family consists of cytokines such as IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15, and IL-21 that all bind the common gamma-chain receptor. Below we will focus the discussion on IL-15 and IL-21 that are commonly derived from myeloid cells.

Interleukin-15

IL-15/IL-5Rα induces NK cell survival and proliferation by acting as a soluble form or presented at the DC membrane. As mentioned above, it is also an essential driver of NK cell development and activation (37–39, 96). IL-15 expression correlates with NK cell infiltration in human tumor samples (97), and data from a murine melanoma model indicate CD11b+Ly6ChiLy6G- monocytic cells are the major source of this cytokine (78). IL-15, together with IL-12, also indirectly regulates NK cell functions by controlling metabolism via mTORC1 activation, which stimulates nutrient uptake, glycolysis, and OXPHOS, thereby providing the energy for NK cell proliferation, proper functions and enhanced persistance (36, 98). Interestingly, chronic IL-15 stimulation of NK cells results in exhaustion by reducing the mitochondrial respiratory capacity (99).

Interleukin-21

In addition to IL-15, DCs also release IL-21, which following STAT3 and STAT1 signaling in NK cells, promotes NK cell cytotoxicity via increased granzyme B and perforin expression. Moreover, STAT1 and PI3K pathways are essential for IL-21-mediated reversal of NK cell exhaustion in mice and for intratumoral human NK cells cultured in vitro (45). Interestingly, IL-21 differentially regulates the expression of activating receptors by inducing NKp30 levels while reducing NKG2D/DAP10 expression in human NK cell (100). However, IL-21 contributes to tumor rejection in an NKG2D-dependent manner in multiple mouse tumor models (101).

Interleukin-17 Can Promote Natural Killer Cell Cytotoxicity While Limiting Terminal Differentiation of Natural Killer Cells

Neutrophils are the major producers of IL-17, which binds to a dimeric receptor and mainly signals through the NF-kB and ERK pathways (102). IL-17 has been shown to enhance NK cell recruitment in human esophageal cancer through tumor-derived chemokines and NK cell cytotoxicity through the increased expression of activating receptors, perforin, granzyme B, TNF-α, and IFN-γ (103). However, IL-17 has also been reported to limit IL-15-mediated terminal murine NK cell differentiation via upregulation of suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS), which inhibits STAT5 phosphorylation, and reduces NK cell killing in the presence of IFN-γ (56).

Context-Dependent Role of Interleukin-18 in Cancer

Upon interaction with its heterodimeric receptor and the activation of the MyD88 signaling pathway, IL-18 primes NK cells to produce IFN-γ (104). In vitro data also show that IL-18 can favor the differentiation of human CD56dim CCR7+ CD25+ CD83+ helper NK cells, which control tumor dissemination and CD8+ T cell activation through the crosstalk with DCs in the lymph nodes (40, 41, 105). Similar to other activating cytokines, such as IL-17 above, also IL-18 can display immunosuppressive features by boosting TGF-β-mediated immunosuppression (106), formation of MDSCs, and induction of PD1 expression on NK cells in mouse models (42, 107, 108). Notably, the upregulation of IL-18 binding protein (IL-18BP), which sequesters IL-18 as a physiological negative feedback mechanism, has been reported as an immune escape strategy (42, 109).

Natural Killer Cell Dysfunction in the Tumor Microenvironment Triggered by Myeloid-Derived Cytokines

Although the NK-myeloid crosstalk stimulates anti-tumor immunity by NK cells in the early tumor development, immunosuppressive cytokines promoting NK cell dysfunction predominate in the aggravated TME of more advanced tumors. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and MDSCs are usually the main myeloid cell populations in such TME and represent the major producers of NK cell suppressive TGF-β and IL-10 (Figure 1A and Table 1A) (110).

Transforming Growth Factor-β

As mentioned above, TGF-β is a key suppressor of NK cell migration, cytotoxicity, and cytokine production via transcriptional and post-transcriptional control of receptor and effector molecule expression (111). As an example, TGF-β-mediated downregulation of CX3CR1 can limit NK cell migration towards the tumor site (25); similarly, the downregulation of activating receptors including NKG2D and NKp30 as well as the adaptor proteins DAP10 and DAP12 triggered by TGF-β diminishes human NK cell cytotoxicity in vitro (26–28, 111). TGF-β-mediated NK cell conversion into Eomes- ILC1 with increased expression levels of inhibitory receptors may represent an additional mechanism to reduce NK cell cytotoxicity in mouse tumor models (29), while a third mechanism is the inhibition of signaling pathways downstream of pro-inflammatory cytokines (30, 36, 111, 112). TGF-β-induced miRNA targets STAT1, which is essential for perforin expression (111), whereas blockade of IL-15-mediated mTOR activity dampens NK cell metabolism. Beyond this, TGF-β also reduces NK cell-mediated IFN-γ and TNF-α production in both human and mouse (29, 30, 36, 111, 112).

Interleukin-10

Like TGF-β, IL-10 directly inhibits IFN-γ and TNF-α production by NK cells in vitro. This effect is also indirectly mediated via inhibition of IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18 production in myeloid cells (24, 58). Yet, in the presence of IL-12 and IL-18, IL-10 has also been shown to stimulate NK cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, and IFN-γ production in vitro via the STAT3 signaling pathway (24, 31, 113, 114). More studies are needed to determine this complex relationship between NK cell suppressive and possibly NK cell promoting properties of IL-10.

Interleukin-32α

Another myeloid-derived immunosuppressive cytokine that can characterize the NK cell suppressive TME is IL-32α. IL-32α, which is often found highly expressed in the TME (115), inhibits IL-15-induced upregulation of perforin and granzyme B in vitro (34). Interestingly, dysregulated levels of IL-32α impairs human NK cell functions in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome (116).

Interleukin-1β

IL-1β is released by monocytes, DCs, and macrophages and stimulates the expansion of CD11b+Gr-1+Ly6C- MDSCs, which are potent inhibitors of murine NK cells in vivo (117). This cytokine has also been reported to maintain human NK cells in an immature state in the presence of IL-15 in secondary lymphoid tissues (23). Similarily to several cytokines above, IL-1β can also have NK cell promoting effects. One example is by indirectly promoting NK cell IFN-γ release by inducing IL-21 production in Th9 cells in mice (118).

Natural Killer Cell-Derived Cytokines Regulating Myeloid Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment

Upon cytokine stimulation and target cell encounter, NK cells themselves produce a range of cytokines such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and in some cases IL-10, that in turn modulate myeloid cells (119–121) (Figure 1A and Table 1B). In this section, we will summarize how cytokines released by NK cells affect the NK-myeloid cell crosstalk.

Dendritic Cells

DCs are central in triggering immune responses by T and NK cells. However, NK cells are also important for the DC function. In addition to cell-to-cell contact, NK cell-derived IFN-γ, TNF-α, and GM-CSF play a key role in the maturation and activation of human antigen-presenting DCs in the TME and lymphoid organs (59–61, 122). Further, activated human DCs maintain the IFN-γ production and induce high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) production in NK cells via secretion of IL-12 and IL-18, resulting in further DC activation and maturation (43, 65). Hence, NK cells can be central in promoting DC maturation and activation, thereby feeding the positive loop of NK-myeloid crosstalk involving DCs in the TME.

Tumor-Associated Macrophages

TAMs are often immunosuppressive and known drivers of tumor progression (123). However, macrophages in the TME have a high degree of plasticity and can even display a pro-inflammatory phenotype (M1) and release IFN-γ and TNF-α (124). In vitro studies have shown that IFN-γ is the main cytokine that drives classical activation of macrophages and polarizes them towards an M1-like phenotype (62). Indeed, as highlighted in a murine sarcoma model, NK cell-derived IFN-γ promotes M1 polarization of macrophages (63). Additionally, TNF-α, and GM-CSF also support an inflammatory phenotype in macrophages (62). Hence, NK cells can also have a critical role in maintaining a pro-inflammatory phenotype of TAMs.

Tumor-Associated Neutrophils

Similar to TAMs, tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) can be both tumor-promoting or pro-inflammatory and thereby counteract tumor growth. Recently, the first studies have investigated the interaction of NK cells with TANs in mouse models. NK cell-derived IFN-γ inhibits the tumor-promoting function of TANs in murine sarcoma and lung cancer models (64). NK cell-derived GM-CSF appears to promote Neutrophils Extracellular Trap formation by neutrophils, which can support tumor metastasis (66, 67).

Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells

MDSCs include a heterogenous group of myeloid cells that have a markedly strong immunosuppressive ability. While NK cell-derived GM-CSF results in DC activation and macrophage polarization towards an anti-tumorigenic phenotype, GM-CSF expands MDSCs in human and murine tumors (62, 125, 126). The exact role of NK cell-derived GM-CSF in promoting MDSC expansion in the TME remains unclear but should likely not be neglected. Importantly, it is clear that NK cells can promote MDSCs in the TME also by other mechanisms. A CD73+ IL-10-secreting subset of NK cells was recently identified in human sarcomas (127). While IL-10 promotes regulatory T cells (Tregs), it has also been shown to maintain the immune-suppressive functions of MDSCs in ovarian cancer (128).

Therapeutic Approaches to Directly Stimulate Natural Killer Cells or to Revert the Tumor Microenvironment to Favor Natural Killer Cell Anti-Tumor Responses

As highlighted in the previous sections, controlling the cytokine milieu in the TME is likely key to unleash the full potential of NK cell-based immunotherapies for several malignancies. Below, we will discuss ongoing and future approaches to enhance NK cell cytotoxicity in the TME (Figure 1B).

Administration of Cytokines

Administration of cytokines to boost NK cell anti-tumor cytotoxicity has been widely explored in the recent years. IL-2, IL-12, IL-15, and IL-21 represent the most promising cytokines under investigation. While IL-2 acts on several immune cell populations, the effects of IL-15 is mainly limited to NK cells and CD8+ T cells. Promising results have been obtained in phase I clinical trials for melanoma and hematologic malignancies using ALT-803 (an IL-15 mutein/IL-15Rα complex fused with the IgG1 Fc) (129, 130). However, side-effects observed following high-dose administration of both IL-2 and IL-15 represents a major challenge along with mobilization of Tregs (131, 132). An alternative strategy to reduce the risk of side-effects while stimulating NK cells more specifically is the use of IL-2 mutants, such as IL-2 F42K and IL-2 H9 that compared to wildtype IL-2 preferentially bind IL-2Rα and thereby increases NK cell activation without inducing Treg expansion (133–135). Likewise, although the use of IL-18 therapy did not show toxicity and was ineffective in several clinical trials, a novel IL-18 mutant has been recently shown to induce NK cell anti-tumor activity (136).

To avoid the toxicities of high-dose cytokines, investigators have also addressed the use of lower doses following adoptive NK cell transfer or combined with checkpoint blockade or fused to anti-tumor antibodies. Intermediate doses of IL-2 have been explored to support adoptively infused NK cells (5). In this context, IL-2 is intended to promote persistence and expansion of the infused donor NK cells, however, data also show IL-2 mobilizes Tregs which likely counteract the effect of the transferred NK cells. As clinical protocols on adoptive NK cell transfer where post-infusion IL-2 has been omitted report similar outcomes as those with IL-2 (137), it remains unclear as to whether post-NK cell infusion IL-2 is of benefit or not. Administration of IL-15 has also been used to support adoptively infused NK cells. However, although in initial trials report this cytokine may trigger better responses, intermediate doses of IL-15 were associated with cytokine-release syndrome (CRS) when administrated subcutaneously (138). Additional investigations are needed to identify which cytokines and the window in which they promote the effect of adoptively infused NK cells.

IL-15, IL-12, and IL-21 are under clinical investigation combined with anti-CTLA4, anti-TIM3, or anti-PD-1 (139, 140). Alternative approaches that are also currently explored are based on the generation of anti-tumor antibody-cytokine fusion molecules. Trispecific killer engagers (TriKEs) fused with IL-15 have demonstrated their ability to boost NK cell functions and persistence (141, 142), whereas IL-21 fused to anti-CD20 increases mouse survival in a lymphoma model (143). Future studies have to address the clinical efficacy of these approaches.

Modulation and Prevention of Cytokine Signaling

In addition to the more direct cytokine-based treatment approaches discussed above, there are also indirect strategies explored. Targeting pathways downstream of cytokine receptors may represent an alternative or complementary approach. Inhibition of SOCS proteins is promising since blockade of the STAT5 inhibitor CIS increases NK cell-mediated anti-tumor activity (144). In preclinical models, agonists of the stimulator of IFN genes (STING) pathway induce tumor regression by stimulating IL-15 production by infiltrating myeloid cells (145). Data also support the potential of GSK3 inhibitors in promoting maturation and cytotoxicity of NK cells following expansion ex vivo with IL-15 (146) GSK3 inhibition increased NK cell production of TNF and IFN-γ as well as bolstered the NK cytotoxicity per se and via ADCC, which translated into better tumor control of human ovarian cancer in a mouse model. An alterantive strategy is to alter the cytokine environment in the TME by neutralizing immunosuppressive cytokines. Ongoing trials with anti-TGF-β (Fresolimumab) and inhibitors of TGF-β signaling (140) will show if such approach has potential for the future. Depletion and/or prevention of the infiltration of suppressive cytokine-producing myeloid cells in the TME per se represents a tempting and yet incompletely explored alternative that indirectly would bolster the anti-tumor properties of NK cells. This approach needs further attention in future studies.

Concluding Remarks

The network of cells and signals in the TME is complex and not yet fully understood. However, ample evidence show that this environment most often is NK cell suppressive, especially in more advanced disease. Yet, the NK-myeloid cell crosstalk is central in shaping NK cell anti-tumor responses and that a better understanding of this crosstalk is required to improve outcomes of NK cell-based cancer immunotherapies. While strategies directed towards boosting NK cell cytotoxicity per se using cytokines or drugs that modulate cytokine signaling, other complementory approaches directed towards reverting the TME to favor anti-tumor immunity is likely required to promote long-term responses.

As pointed out in this mini review, challenges hindering prompt progress in the field include the multitude of different cell types in the TME along with the context-dependent functions of several cytokines derived from both the myeloid cells and the NK cells. We predict that recent developments related to genetic engineering of NK cells along with the arsenal of new cytokine mutants as well as targeted and immunomodulatory drugs, alone or combination, can facilitate progress in the field. We foresee the use of genetically engineered NK cells to help improve their efficacy per se but also to resist and persist in the TME and thereby have the chance to revert it to a more pro-inflammatory milieu optimal for initating potent durable anti-tumor immune reponses. CAR-NK cells equipped with cytokine signaling elements or dominant negative cytokine receptors are examples that hold promise. We are positive that this along with further insights in the basic biology of cytokines and cytokine signaling will help improve NK cell-based cancer immunotherapy.

Author Contributions

SG, KW, MC, and SM have together outlined and written the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from Jeanssons Stiftelser (MC), Swedish Society for Medical Research (MC), Wallenberg Clinical Fellow (MC), Cancerfonden (MC) and the Swedish Research Council (MC) as well as from Fondation Arc Pour La Recherche Sur Le Cancer (SM), Ligue Nationale Contre Le Cancer (SM), Cancéropôle Nord-Ouest (SM), and CPER (SM).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the funding agencies supporting our work.

References

- 1. Chiossone L, Dumas P-Y, Vienne M, Vivier E. Natural killer cells and other innate lymphoid cells in cancer. Nat Rev Immunol (2018) 18:671–88. 10.1038/s41577-018-0061-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Long EO, Sik Kim H, Liu D, Peterson ME, Rajagopalan S. Controlling Natural Killer Cell Responses: Integration of Signals for Activation and Inhibition. Annu Rev Immunol (2013) 31:227–58. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Malmberg K-J, Carlsten M, Björklund A, Sohlberg E, Bryceson YT, Ljunggren H-G. Natural killer cell-mediated immunosurveillance of human cancer. Semin Immunol (2017) 31:20–9. 10.1016/j.smim.2017.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Urbani E, Perruccio K, Shlomchik WD, Tosti A, et al. Effectiveness of donor natural killer cell alloreactivity in mismatched hematopoietic transplants. Science (2002) 295:2097–100. 10.1126/science.1068440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Miller JS, Soignier Y, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, McNearney SA, Yun GH, Fautsch SK, et al. Successful adoptive transfer and in vivo expansion of human haploidentical NK cells in patients with cancer. Blood (2005) 105:3051–7. 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carlsten M, Norell H, Bryceson YT, Poschke I, Schedvins K, Ljunggren H-G, et al. Primary human tumor cells expressing CD155 impair tumor targeting by down-regulating DNAM-1 on NK cells. J Immunol (2009) 183:4921–30. 10.4049/jimmunol.0901226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carlsten M, Baumann BC, Simonsson M, Jädersten M, Forsblom A-M, Hammarstedt C, et al. Reduced DNAM-1 expression on bone marrow NK cells associated with impaired killing of CD34+ blasts in myelodysplastic syndrome. Leukemia (2010) 24:1607–16. 10.1038/leu.2010.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Devillier R, Chrétien A-S, Pagliardini T, Salem N, Blaise D, Olive D. Mechanisms of NK cell dysfunction in the tumor microenvironment and current clinical approaches to harness NK cell potential for immunotherapy. J Leukocyte Biol (2020). 10.1002/JLB.5MR0920-198RR [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9. Melaiu O, Lucarini V, Cifaldi L, Fruci D. Influence of the Tumor Microenvironment on NK Cell Function in Solid Tumors. Front Immunol (2019) 10:3038. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.03038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sarhan D, Wang J, Sunil Arvindam U, Hallstrom C, Verneris MR, Grzywacz B, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells shape the MDS microenvironment by inducing suppressive monocytes that dampen NK cell function. JCI Insight (2020) 5(5):e130155. 10.1172/jci.insight.130155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Romero AI, Thorén FB, Brune M, Hellstrand K. NKp46 and NKG2D receptor expression in NK cells with CD56dim and CD56bright phenotype: regulation by histamine and reactive oxygen species. Br J Haematol (2006) 132:91–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05842.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Iyori M, Zhang T, Pantel H, Gagne BA, Sentman CL. TRAIL/DR5 plays a critical role in NK cell-mediated negative regulation of dendritic cell cross-priming of T cells. J Immunol (2011) 187:3087–95. 10.4049/jimmunol.1003879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pallmer K, Oxenius A. Recognition and Regulation of T Cells by NK Cells. Front Immunol (2016) 7:251. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Raulet DH. Interplay of natural killer cells and their receptors with the adaptive immune response. Nat Immunol (2004) 5:996–1002. 10.1038/ni1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Salagianni M, Lekka E, Moustaki A, Iliopoulou EG, Baxevanis CN, Papamichail M, et al. NK cell adoptive transfer combined with Ontak-mediated regulatory T cell elimination induces effective adaptive antitumor immune responses. J Immunol (2011) 186:3327–35. 10.4049/jimmunol.1000652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kumar V, Patel S, Tcyganov E, Gabrilovich DI. The Nature of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment. Trends Immunol (2016) 37:208–20. 10.1016/j.it.2016.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Veglia F, Gabrilovich DI. Dendritic cells in cancer: the role revisited. Curr Opin Immunol (2017) 45:43–51. 10.1016/j.coi.2017.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kiss M, Van Gassen S, Movahedi K, Saeys Y, Laoui D. Myeloid cell heterogeneity in cancer: not a single cell alike. Cell Immunol (2018) 330:188–201. 10.1016/j.cellimm.2018.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vivier E, Raulet DH, Moretta A, Caligiuri MA, Zitvogel L, Lanier LL, et al. Innate or adaptive immunity? The example of natural killer cells. Science (2011) 331:44–9. 10.1126/science.1198687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Böttcher JP, Bonavita E, Chakravarty P, Blees H, Cabeza-Cabrerizo M, Sammicheli S, et al. NK Cells Stimulate Recruitment of cDC1 into the Tumor Microenvironment Promoting Cancer Immune Control. Cell (2018) 172:1022–1037.e14. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Walzer T, Dalod M, Robbins SH, Zitvogel L, Vivier E. Natural-killer cells and dendritic cells: “l’union fait la force.” Blood (2005) 106:2252–8. 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang L, Pang Y, Moses HL. TGF-beta and immune cells: an important regulatory axis in the tumor microenvironment and progression. Trends Immunol (2010) 31:220–7. 10.1016/j.it.2010.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hughes T, Becknell B, Freud AG, McClory S, Briercheck E, Yu J, et al. Interleukin-1β Selectively Expands and Sustains Interleukin-22+ Immature Human Natural Killer Cells in Secondary Lymphoid Tissue. Immunity (2010) 32:803–14. 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mannino MH, Zhu Z, Xiao H, Bai Q, Wakefield MR, Fang Y. The paradoxical role of IL-10 in immunity and cancer. Cancer Lett (2015) 367:103–7. 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Regis S, Caliendo F, Dondero A, Casu B, Romano F, Loiacono F, et al. TGF-β1 Downregulates the Expression of CX3CR1 by Inducing miR-27a-5p in Primary Human NK Cells. Front Immunol (2017) 8:868:868. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Castriconi R, Cantoni C, Chiesa MD, Vitale M, Marcenaro E, Conte R, et al. Transforming growth factor β1 inhibits expression of NKp30 and NKG2D receptors: Consequences for the NK-mediated killing of dendritic cells. PNAS (2003) 100:4120–5. 10.1073/pnas.0730640100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Espinoza JL, Takami A, Yoshioka K, Nakata K, Sato T, Kasahara Y, et al. Human microRNA-1245 down-regulates the NKG2D receptor in natural killer cells and impairs NKG2D-mediated functions. Haematologica (2012) 97:1295–303. 10.3324/haematol.2011.058529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Park YP, Choi S-C, Kiesler P, Gil-Krzewska A, Borrego F, Weck J, et al. Complex regulation of human NKG2D-DAP10 cell surface expression: opposing roles of the γc cytokines and TGF-β1. Blood (2011) 118:3019–27. 10.1182/blood-2011-04-346825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gao Y, Souza-Fonseca-Guimaraes F, Bald T, Ng SS, Young A, Ngiow SF, et al. Tumor immunoevasion by the conversion of effector NK cells into type 1 innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol (2017) 18:1004–15. 10.1038/ni.3800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Viel S, Marçais A, Guimaraes FS-F, Loftus R, Rabilloud J, Grau M, et al. TGF-β inhibits the activation and functions of NK cells by repressing the mTOR pathway. Sci Signal (2016) 9:ra19. 10.1126/scisignal.aad1884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lauw FN, Pajkrt D, Hack CE, Kurimoto M, van Deventer SJ, van der Poll T. Proinflammatory effects of IL-10 during human endotoxemia. J Immunol (2000) 165:2783–9. 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cai G, Kastelein RA, Hunter CA. IL-10 enhances NK cell proliferation, cytotoxicity and production of IFN-γ when combined with IL-18. Eur J Immunol (1999) 29:2658–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Parato KG, Kumar A, Badley AD, Sanchez-Dardon JL, Chambers KA, Young CD, et al. Normalization of natural killer cell function and phenotype with effective anti-HIV therapy and the role of IL-10. AIDS (2002) 16:1251–6. 10.1097/00002030-200206140-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gorvel L, Korenfeld D, Tung T, Klechevsky E. Dendritic Cell–Derived IL-32α: A Novel Inhibitory Cytokine of NK Cell Function. J Immunol (2017) 199:1290–300. 10.4049/jimmunol.1601477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Almishri W, Santodomingo-Garzon T, Le T, Stack D, Mody CH, Swain MG. TNFα Augments Cytokine-Induced NK Cell IFNγ Production through TNFR2. JIN (2016) 8:617–29. 10.1159/000448077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. O’Brien KL, Finlay DK. Immunometabolism and natural killer cell responses. Nat Rev Immunol (2019) 19:282–90. 10.1038/s41577-019-0139-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lucas M, Schachterle W, Oberle K, Aichele P, Diefenbach A. Dendritic Cells Prime Natural Killer Cells by trans-Presenting Interleukin 15. Immunity (2007) 26:503–17. 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Koka R, Burkett P, Chien M, Chai S, Boone DL, Ma A. Cutting Edge: Murine Dendritic Cells Require IL-15Rα to Prime NK Cells. J Immunol (2004) 173:3594–8. 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wagner JA, Rosario M, Romee R, Berrien-Elliott MM, Schneider SE, Leong JW, et al. CD56bright NK cells exhibit potent antitumor responses following IL-15 priming. J Clin Invest (2017) 127:4042–58. 10.1172/JCI90387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mailliard RB, Alber SM, Shen H, Watkins SC, Kirkwood JM, Herberman RB, et al. IL-18–induced CD83+CCR7+ NK helper cells. J Exp Med (2005) 202:941–53. 10.1084/jem.20050128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wong JL, Mailliard RB, Moschos SJ, Edington H, Lotze MT, Kirkwood JM, et al. Helper Activity of Natural Killer Cells During the Dendritic Cell-mediated Induction of Melanoma-specific Cytotoxic T Cells. J Immunother (2011) 34:270–8. 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31820b370b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fabbi M, Carbotti G, Ferrini S. Context-dependent role of IL-18 in cancer biology and counter-regulation by IL-18BP. J Leukocyte Biol (2015) 97:665–75. 10.1189/jlb.5RU0714-360RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Semino C, Angelini G, Poggi A, Rubartelli A. NK/iDC interaction results in IL-18 secretion by DCs at the synaptic cleft followed by NK cell activation and release of the DC maturation factor HMGB1. Blood (2005) 106:609–16. 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bellora F, Castriconi R, Dondero A, Pessino A, Nencioni A, Liggieri G, et al. TLR activation of tumor-associated macrophages from ovarian cancer patients triggers cytolytic activity of NK cells. Eur J Immunol (2014) 44:1814–22. 10.1002/eji.201344130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Seo H, Jeon I, Kim B-S, Park M, Bae E-A, Song B, et al. IL-21-mediated reversal of NK cell exhaustion facilitates anti-tumour immunity in MHC class I-deficient tumours. Nat Commun (2017) 8:15776. 10.1038/ncomms15776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jones SA, Jenkins BJ. Recent insights into targeting the IL-6 cytokine family in inflammatory diseases and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol (2018) 18:773–89. 10.1038/s41577-018-0066-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cifaldi L, Prencipe G, Caiello I, Bracaglia C, Locatelli F, De Benedetti F, et al. Inhibition of Natural Killer Cell Cytotoxicity by Interleukin-6: Implications for the Pathogenesis of Macrophage Activation Syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol (2015) 67:3037–46. 10.1002/art.39295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Laroni A, Gandhi R, Beynon V, Weiner HL. IL-27 Imparts Immunoregulatory Function to Human NK Cell Subsets. PloS One (2011) 6:e26173. 10.1371/journal.pone.0026173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ziblat A, Domaica CI, Spallanzani RG, Iraolagoitia XLR, Rossi LE, Avila DE, et al. IL-27 stimulates human NK-cell effector functions and primes NK cells for IL-18 responsiveness. Eur J Immunol (2015) 45:192–202. 10.1002/eji.201444699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Matsui M, Kishida T, Nakano H, Yoshimoto K, Shin-Ya M, Shimada T, et al. Interleukin-27 Activates Natural Killer Cells and Suppresses NK-Resistant Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma through Inducing Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity. Cancer Res (2009) 69:2523–30. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hemati M, Rasouli Nejad Z, Shokri M-R, Ghahremanfard F, Mir Mohammadkhani M, Kokhaei P. IL-27 impact on NK cells activity: Implication for a robust anti-tumor response in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Int Immunopharmacol (2020) 82:106350. 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dondero A, Casu B, Bellora F, Vacca A, Luisi AD, Frassanito MA, et al. NK cells and multiple myeloma-associated endothelial cells: molecular interactions and influence of IL-27. Oncotarget (2017) 8(21):35088–102. 10.18632/oncotarget.17070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wei J, Xia S, Sun H, Zhang S, Wang J, Zhao H, et al. Critical Role of Dendritic Cell–Derived IL-27 in Antitumor Immunity through Regulating the Recruitment and Activation of NK and NKT Cells. J Immunol (2013) 191:500–8. 10.4049/jimmunol.1300328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ziblat A, Nuñez SY, Raffo Iraolagoitia XL, Spallanzani RG, Torres NI, Sierra JM, et al. Interleukin (IL)-23 Stimulates IFN-γ Secretion by CD56bright Natural Killer Cells and Enhances IL-18-Driven Dendritic Cells Activation. Front Immunol (2018) 8:1959. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Teng MWL, Andrews DM, McLaughlin N, von Scheidt B, Ngiow SF, Möller A, et al. IL-23 suppresses innate immune response independently of IL-17A during carcinogenesis and metastasis. PNAS (2010) 107:8328–33. 10.1073/pnas.1003251107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wang X, Sun R, Hao X, Lian Z-X, Wei H, Tian Z. IL-17 constrains natural killer cell activity by restraining IL-15–driven cell maturation via SOCS3. PNAS (2019) 116:17409–18. 10.1073/pnas.1904125116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Qian X, Chen H, Wu X, Hu L, Huang Q, Jin Y. Interleukin-17 acts as double-edged sword in anti-tumor immunity and tumorigenesis. Cytokine (2017) 89:34–44. 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Konjević GM, Vuletić AM, Mirjačić Martinović KM, Larsen AK, Jurišić VB. The role of cytokines in the regulation of NK cells in the tumor environment. Cytokine (2019) 117:30–40. 10.1016/j.cyto.2019.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Piccioli D, Sbrana S, Melandri E, Valiante NM. Contact-dependent stimulation and inhibition of dendritic cells by natural killer cells. J Exp Med (2002) 195:335–41. 10.1084/jem.20010934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gerosa F, Baldani-Guerra B, Nisii C, Marchesini V, Carra G, Trinchieri G. Reciprocal activating interaction between natural killer cells and dendritic cells. J Exp Med (2002) 195:327–33. 10.1084/jem.20010938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Vitale M, Della Chiesa M, Carlomagno S, Pende D, Aricò M, Moretta L, et al. NK-dependent DC maturation is mediated by TNFalpha and IFNgamma released upon engagement of the NKp30 triggering receptor. Blood (2005) 106:566–71. 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sica A, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J Clin Invest (2012) 122:787–95. 10.1172/JCI59643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. O’Sullivan T, Saddawi-Konefka R, Vermi W, Koebel CM, Arthur C, White JM, et al. Cancer immunoediting by the innate immune system in the absence of adaptive immunity. J Exp Med (2012) 209:1869–82. 10.1084/jem.20112738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ogura K, Sato-Matsushita M, Yamamoto S, Hori T, Sasahara M, Iwakura Y, et al. NK Cells Control Tumor-Promoting Function of Neutrophils in Mice. Cancer Immunol Res (2018) 6:348–57. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Mailliard RB, Son Y-I, Redlinger R, Coates PT, Giermasz A, Morel PA, et al. Dendritic cells mediate NK cell help for Th1 and CTL responses: two-signal requirement for the induction of NK cell helper function. J Immunol (2003) 171:2366–73. 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bertin F-R, Rys RN, Mathieu C, Laurance S, Lemarié CA, Blostein MD. Natural killer cells induce neutrophil extracellular trap formation in venous thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost (2019) 17:403–14. 10.1111/jth.14339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yang L, Liu Q, Zhang X, Liu X, Zhou B, Chen J, et al. DNA of neutrophil extracellular traps promotes cancer metastasis via CCDC25. Nature (2020) 583(7814):133–8. 10.1038/s41586-020-2394-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Louis C, Souza-Fonseca-Guimaraes F, Yang Y, D’Silva D, Kratina T, Dagley L, et al. NK cell-derived GM-CSF potentiates inflammatory arthritis and is negatively regulated by CIS. J Exp Med (2020) 217(5):e20191421. 10.1084/jem.20191421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Gotthardt D, Putz EM, Grundschober E, Prchal-Murphy M, Straka E, Kudweis P, et al. STAT5 Is a Key Regulator in NK Cells and Acts as a Molecular Switch from Tumor Surveillance to Tumor Promotion. Cancer Discovery (2016) 6:414–29. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Huntington ND, Cursons J, Rautela J. The cancer-natural killer cell immunity cycle. Nat Rev Cancer (2020) 20(8):437–54. 10.1038/s41568-020-0272-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Galluzzi L, Buqué A, Kepp O, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Immunogenic cell death in cancer and infectious disease. Nat Rev Immunol (2017) 17:97–111. 10.1038/nri.2016.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Castriconi R, Carrega P, Dondero A, Bellora F, Casu B, Regis S, et al. Molecular Mechanisms Directing Migration and Retention of Natural Killer Cells in Human Tissues. Front Immunol (2018) 9:2324. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. O’Sullivan TE, Sun JC, Lanier LL. Natural Killer Cell Memory. Immunity (2015) 43:634–45. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Fehniger TA, Shah MH, Turner MJ, VanDeusen JB, Whitman SP, Cooper MA, et al. Differential Cytokine and Chemokine Gene Expression by Human NK Cells Following Activation with IL-18 or IL-15 in Combination with IL-12: Implications for the Innate Immune Response. J Immunol (1999) 162:4511–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Leong JW, Chase JM, Romee R, Schneider SE, Sullivan RP, Cooper MA, et al. Preactivation with IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18 Induces CD25 and a Functional High-Affinity IL-2 Receptor on Human Cytokine-Induced Memory-like Natural Killer Cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant (2014) 20:463–73. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Burkholder B, Huang R-Y, Burgess R, Luo S, Jones VS, Zhang W, et al. Tumor-induced perturbations of cytokines and immune cell networks. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) Rev Cancer (2014) 1845:182–201. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ewen E-M, Pahl JHW, Miller M, Watzl C, Cerwenka A. KIR downregulation by IL-12/15/18 unleashes human NK cells from KIR/HLA-I inhibition and enhances killing of tumor cells. Eur J Immunol (2018) 48:355–65. 10.1002/eji.201747128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Carrero RMS, Beceren-Braun F, Rivas SC, Hegde SM, Gangadharan A, Plote D, et al. IL-15 is a component of the inflammatory milieu in the tumor microenvironment promoting antitumor responses. PNAS (2019) 116:599–608. 10.1073/pnas.1814642116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Nguyen KB, Salazar-Mather TP, Dalod MY, Van Deusen JB, Wei X, Liew FY, et al. Coordinated and distinct roles for IFN-alpha beta, IL-12, and IL-15 regulation of NK cell responses to viral infection. J Immunol (2002) 169:4279–87. 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Müller L, Aigner P, Stoiber D. Type I Interferons and Natural Killer Cell Regulation in Cancer. Front Immunol (2017) 8:304. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Paolini R, Bernardini G, Molfetta R, Santoni A. NK cells and interferons. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev (2015) 26:113–20. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Sheehan KCF, Shankaran V, Uppaluri R, Bui JD, et al. A critical function for type I interferons in cancer immunoediting. Nat Immunol (2005) 6:722–9. 10.1038/ni1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Swann JB, Hayakawa Y, Zerafa N, Sheehan KCF, Scott B, Schreiber RD, et al. Type I IFN Contributes to NK Cell Homeostasis, Activation, and Antitumor Function. J Immunol (2007) 178:7540–9. 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Gough DJ, Messina NL, Clarke CJP, Johnstone RW, Levy DE. Constitutive type I interferon modulates homeostatic balance through tonic signaling. Immunity (2012) 36:166–74. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Montoya M, Schiavoni G, Mattei F, Gresser I, Belardelli F, Borrow P, et al. Type I interferons produced by dendritic cells promote their phenotypic and functional activation. Blood (2002) 99:3263–71. 10.1182/blood.v99.9.3263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Thierfelder WE, van Deursen JM, Yamamoto K, Tripp RA, Sarawar SR, Carson RT, et al. Requirement for Stat4 in interleukin-12-mediated responses of natural killer and T cells. Nature (1996) 382:171–4. 10.1038/382171a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Sun JC, Madera S, Bezman NA, Beilke JN, Kaplan MH, Lanier LL. Proinflammatory cytokine signaling required for the generation of natural killer cell memory. J Exp Med (2012) 209:947–54. 10.1084/jem.20111760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Yamamoto K, Shibata F, Miyasaka N, Miura O. The human perforin gene is a direct target of STAT4 activated by IL-12 in NK cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2002) 297:1245–52. 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02378-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol (2003) 3:133–46. 10.1038/nri1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Ferlazzo G, Pack M, Thomas D, Paludan C, Schmid D, Strowig T, et al. Distinct roles of IL-12 and IL-15 in human natural killer cell activation by dendritic cells from secondary lymphoid organs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2004) 101:16606–11. 10.1073/pnas.0407522101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Ni J, Hölsken O, Miller M, Hammer Q, Luetke-Eversloh M, Romagnani C, et al. Adoptively transferred natural killer cells maintain long-term antitumor activity by epigenetic imprinting and CD4+ T cell help. Oncoimmunology (2016) 5:e1219009. 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1219009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Teng MWL, von Scheidt B, Duret H, Towne JE, Smyth MJ. Anti-IL-23 Monoclonal Antibody Synergizes in Combination with Targeted Therapies or IL-2 to Suppress Tumor Growth and Metastases. Cancer Res (2011) 71:2077–86. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Yoshida H, Hunter CA. The immunobiology of interleukin-27. Annu Rev Immunol (2015) 33:417–43. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Murugaiyan G, Saha B. IL-27 in tumor immunity and immunotherapy. Trends Mol Med (2013) 19:108–16. 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Zwirner NW, Ziblat A. Regulation of NK Cell Activation and Effector Functions by the IL-12 Family of Cytokines: The Case of IL-27. Front Immunol (2017) 8:25. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Anton OM, Peterson ME, Hollander MJ, Dorward DW, Arora G, Traba J, et al. Trans -endocytosis of intact IL-15Rα–IL-15 complex from presenting cells into NK cells favors signaling for proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2020) 117:522–31. 10.1073/pnas.1911678117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Cursons J, Souza-Fonseca-Guimaraes F, Foroutan M, Anderson A, Hollande F, Hediyeh-Zadeh S, et al. A Gene Signature Predicting Natural Killer Cell Infiltration and Improved Survival in Melanoma Patients. Cancer Immunol Res (2019) 7:1162–74. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Mao Y, van Hoef V, Zhang X, Wennerberg E, Lorent J, Witt K, et al. IL-15 activates mTOR and primes stress-activated gene expression leading to prolonged antitumor capacity of NK cells. Blood (2016) 128:1475–89. 10.1182/blood-2016-02-698027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Felices M, Lenvik AJ, McElmurry R, Chu S, Hinderlie P, Bendzick L, et al. Continuous treatment with IL-15 exhausts human NK cells via a metabolic defect. JCI Insight (2018) 3(3):e96219. 10.1172/jci.insight.96219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Burgess SJ, Marusina AI, Pathmanathan I, Borrego F, Coligan JE. IL-21 Down-Regulates NKG2D/DAP10 Expression on Human NK and CD8+ T Cells. J Immunol (2006) 176:1490–7. 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Takaki R, Hayakawa Y, Nelson A, Sivakumar PV, Hughes S, Smyth MJ, et al. IL-21 Enhances Tumor Rejection through a NKG2D-Dependent Mechanism. J Immunol (2005) 175:2167–73. 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Amatya N, Garg AV, Gaffen SL. IL-17 Signaling: The Yin and the Yang. Trends Immunol (2017) 38:310–22. 10.1016/j.it.2017.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Lu L, Pan K, Zheng H-X, Li J-J, Qiu H-J, Zhao J-J, et al. IL-17A Promotes Immune Cell Recruitment in Human Esophageal Cancers and the Infiltrating Dendritic Cells Represent a Positive Prognostic Marker for Patient Survival. J Immunother (2013) 36:451–8. 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3182a802cf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Chaix J, Tessmer MS, Hoebe K, Fuséri N, Ryffel B, Dalod M, et al. Priming of Natural Killer cells by Interleukin-18. J Immunol (2008) 181:1627–31. 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.1627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Wong JL, Berk E, Edwards RP, Kalinski P. IL-18–Primed Helper NK Cells Collaborate with Dendritic Cells to Promote Recruitment of Effector CD8+ T Cells to the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Res (2013) 73:4653–62. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Casu B, Dondero A, Regis S, Caliendo F, Petretto A, Bartolucci M, et al. Novel Immunoregulatory Functions of IL-18, an Accomplice of TGF-β1. Cancers (2019) 11:75. 10.3390/cancers11010075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Terme M, Ullrich E, Aymeric L, Meinhardt K, Coudert JD, Desbois M, et al. Cancer-Induced Immunosuppression: IL-18–Elicited Immunoablative NK Cells. Cancer Res (2012) 72:2757–67. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Lim HX, Hong H-J, Cho D, Kim TS. IL-18 Enhances Immunosuppressive Responses by Promoting Differentiation into Monocytic Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. J Immunol (2014) 193:5453–60. 10.4049/jimmunol.1401282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Carbotti G, Barisione G, Orengo AM, Brizzolara A, Airoldi I, Bagnoli M, et al. The IL-18 Antagonist IL-18–Binding Protein Is Produced in the Human Ovarian Cancer Microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res (2013) 19:4611–20. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, Inflammation, and Cancer. Cell (2010) 140:883–99. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Regis S, Dondero A, Caliendo F, Bottino C, Castriconi R. NK Cell Function Regulation by TGF-β-Induced Epigenetic Mechanisms. Front Immunol (2020) 11:311. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Zaiatz-Bittencourt V, Finlay DK, Gardiner CM. Canonical TGF-β Signaling Pathway Represses Human NK Cell Metabolism. J Immunol (2018) 200:3934–41. 10.4049/jimmunol.1701461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Park JY, Lee SH, Yoon S-R, Park Y-J, Jung H, Kim T-D, et al. IL-15-Induced IL-10 Increases the Cytolytic Activity of Human Natural Killer Cells. Mol Cells (2011) 32:265–72. 10.1007/s10059-011-1057-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Shibata Y, Foster LA, Kurimoto M, Okamura H, Nakamura RM, Kawajiri K, et al. Immunoregulatory Roles of IL-10 in Innate Immunity: IL-10 Inhibits Macrophage Production of IFN-γ-Inducing Factors but Enhances NK Cell Production of IFN-γ. J Immunol (1998) 161:4283–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Sloot YJE, Smit JW, Joosten LAB, Netea-Maier RT. Insights into the role of IL-32 in cancer. Semin Immunol (2018) 38:24–32. 10.1016/j.smim.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Marcondes AM, Mhyre AJ, Stirewalt DL, Kim S-H, Dinarello CA, Deeg HJ. Dysregulation of IL-32 in myelodysplastic syndrome and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia modulates apoptosis and impairs NK function. PNAS (2008) 105:2865–70. 10.1073/pnas.0712391105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Elkabets M, Ribeiro VSG, Dinarello CA, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Santo JPD, Apte RN, et al. IL-1β regulates a novel myeloid-derived suppressor cell subset that impairs NK cell development and function. Eur J Immunol (2010) 40:3347–57. 10.1002/eji.201041037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Végran F, Berger H, Boidot R, Mignot G, Bruchard M, Dosset M, et al. The transcription factor IRF1 dictates the IL-21-dependent anticancer functions of TH9 cells. Nat Immunol (2014) 15:758–66. 10.1038/ni.2925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Turner SC, Chen KS, Ghaheri BA, Ghayur T, et al. Human natural killer cells: a unique innate immunoregulatory role for the CD56(bright) subset. Blood (2001) 97:3146–51. 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Fauriat C, Long EO, Ljunggren H-G, Bryceson YT. Regulation of human NK-cell cytokine and chemokine production by target cell recognition. Blood (2010) 115:2167–76. 10.1182/blood-2009-08-238469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Delahaye NF, Rusakiewicz S, Martins I, Ménard C, Roux S, Lyonnet L, et al. Alternatively spliced NKp30 isoforms affect the prognosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Nat Med (2011) 17:700–7. 10.1038/nm.2366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Morrissey PJ, Bressler L, Park LS, Alpert A, Gillis S. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor augments the primary antibody response by enhancing the function of antigen-presenting cells. J Immunol (1987) 139:1113–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Jayasingam SD, Citartan M, Thang TH, Mat Zin AA, Ang KC, Ch’ng ES. Evaluating the Polarization of Tumor-Associated Macrophages Into M1 and M2 Phenotypes in Human Cancer Tissue: Technicalities and Challenges in Routine Clinical Practice. Front Oncol (2019) 9:1512. 10.3389/fonc.2019.01512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Mantovani A, Marchesi F, Malesci A, Laghi L, Allavena P. Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment targets in oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol (2017) 14:399–416. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Becher B, Tugues S, Greter M. GM-CSF: From Growth Factor to Central Mediator of Tissue Inflammation. Immunity (2016) 45:963–73. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol (2009) 9:162–74. 10.1038/nri2506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Neo SY, Yang Y, Record J, Ma R, Chen X, Chen Z, et al. CD73 immune checkpoint defines regulatory NK cells within the tumor microenvironment. J Clin Invest (2020) 130:1185–98. 10.1172/JCI128895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Hart KM, Byrne KT, Molloy MJ, Usherwood EM, Berwin B. IL-10 immunomodulation of myeloid cells regulates a murine model of ovarian cancer. Front Immunol (2011) 2:29. 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Margolin K, Morishima C, Velcheti V, Miller JS, Lee SM, Silk AW, et al. Phase I Trial of ALT-803, A Novel Recombinant IL15 Complex, in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res (2018) 24:5552–61. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Romee R, Cooley S, Berrien-Elliott MM, Westervelt P, Verneris MR, Wagner JE, et al. First-in-human phase 1 clinical study of the IL-15 superagonist complex ALT-803 to treat relapse after transplantation. Blood (2018) 131:2515–27. 10.1182/blood-2017-12-823757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Conlon KC, Lugli E, Welles HC, Rosenberg SA, Fojo AT, Morris JC, et al. Redistribution, Hyperproliferation, Activation of Natural Killer Cells and CD8 T Cells, and Cytokine Production During First-in-Human Clinical Trial of Recombinant Human Interleukin-15 in Patients With Cancer. J Clin Oncol (2015) 33:74–82. 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.3329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Abbas AK, Trotta E, Simeonov DR, Marson A, Bluestone JA. Revisiting IL-2: Biology and therapeutic prospects. Sci Immunol (2018) 3:eaat1482. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aat1482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Sim GC, Liu C, Wang E, Liu H, Creasy C, Dai Z, et al. IL2 Variant Circumvents ICOS+ Regulatory T-cell Expansion and Promotes NK Cell Activation. Cancer Immunol Res (2016) 4:983–94. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Ardolino M, Azimi CS, Iannello A, Trevino TN, Horan L, Zhang L, et al. Cytokine therapy reverses NK cell anergy in MHC-deficient tumors. J Clin Invest (2014) 124:4781–94. 10.1172/JCI74337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Mitra S, Leonard WJ. Biology of IL-2 and its therapeutic modulation: Mechanisms and strategies. J Leukoc Biol (2018) 103:643–55. 10.1002/JLB.2RI0717-278R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Zhou T, Damsky W, Weizman O-E, McGeary MK, Hartmann KP, Rosen CE, et al. IL-18BP is a secreted immune checkpoint and barrier to IL-18 immunotherapy. Nature (2020) 583(7817):609–14. 10.1038/s41586-020-2422-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Björklund AT, Carlsten M, Sohlberg E, Liu LL, Clancy T, Karimi M, et al. Complete Remission with Reduction of High-Risk Clones following Haploidentical NK-Cell Therapy against MDS and AML. Clin Cancer Res (2018) 24:1834–44. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Cooley S, He F, Bachanova V, Vercellotti GM, DeFor TE, Curtsinger JM, et al. First-in-human trial of rhIL-15 and haploidentical natural killer cell therapy for advanced acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv (2019) 3:1970–80. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018028332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Waldmann TA. Cytokines in Cancer Immunotherapy. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2018) 10:a028472. 10.1101/cshperspect.a028472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Berraondo P, Sanmamed MF, Ochoa MC, Etxeberria I, Aznar MA, Pérez-Gracia JL, et al. Cytokines in clinical cancer immunotherapy. Br J Cancer (2019) 120:6–15. 10.1038/s41416-018-0328-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Vallera DA, Felices M, McElmurry R, McCullar V, Zhou X, Schmohl JU, et al. IL15 Trispecific Killer Engagers (TriKE) Make Natural Killer Cells Specific to CD33+ Targets While Also Inducing Persistence, In Vivo Expansion, and Enhanced Function. Clin Cancer Res (2016) 22:3440–50. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Felices M, Kodal B, Hinderlie P, Kaminski MF, Cooley S, Weisdorf DJ, et al. Novel CD19-targeted TriKE restores NK cell function and proliferative capacity in CLL. Blood Adv (2019) 3:897–907. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018029371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Bhatt S, Parvin S, Zhang Y, Cho H-M, Kunkalla K, Vega F, et al. Anti-CD20-interleukin-21 fusokine targets malignant B cells via direct apoptosis and NK-cell–dependent cytotoxicity. Blood (2017) 129:2246–56. 10.1182/blood-2016-09-738211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Scarno G, Pietropaolo G, Di Censo C, Gadina M, Santoni A, Sciumè G. Transcriptional, Epigenetic and Pharmacological Control of JAK/STAT Pathway in NK Cells. Front Immunol (2019) 10:2456. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Carrero RMS, Beceren-Braun F, Rivas SC, Hegde SM, Gangadharan A, Plote D, et al. IL-15 is a component of the inflammatory milieu in the tumor microenvironment promoting antitumor responses. PNAS (2019) 116:599–608. 10.1073/pnas.1814642116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Cichocki F, Valamehr B, Bjordahl R, Zhang B, Rezner B, Rogers P, et al. GSK3 Inhibition Drives Maturation of NK Cells and Enhances Their Antitumor Activity. Cancer Res (2017) 77:5664–75. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]