Abstract

Inner cities are characterized by inter-generational poverty, limited educational opportunities, poor health, and high levels of segregation. Human capital, defined as the intangible, yet integral economically productive aspects of individuals, is limited by factors influencing inner-city populations. Inner-city environments are consistent with definitions of disasters causing a level of suffering that exceeds the capacity of the affected community. This article presents a framework for improving health among inner-city populations using a multidisciplinary approach drawn from medicine, economics, and disaster response. Results from focus groups and photovoice conducted in Milwaukee, Wisconsin are used as a case study for a perspective on using this approach to address health disparities. A disaster approach provides a long-term focus on improving overall health and decreasing health disparities in the inner-city, instead of a short-term focus on immediate relief of a single symptom. Adopting a disaster approach to inner-city environments is an innovative way to address the needs of those living in some of the most marginalized communities in the country.

Keywords: inner city, disaster zone, human capital, framework

Introduction

Inner cities are broadly characterized as distressed urban environments that sit outside of the economic mainstream with high concentrations of poverty, limited educational opportunities, poor health, and high levels of segregation [1]. Once synonymous with the term central city, inner cities have been described as the oldest part of a Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) and were the hub of economic production, densely populated with the primary work force and transportation systems [2]. However, economic decline in the 20th century resulted in the systematic departure of many industries from the inner cities to surrounding suburbs [1, 3]. This resulted in deterioration across economic and social conditions, and eventually impoverishment and structural decay over time 1, 3]. The poverty that became characteristic of many inner cities across the US became widespread, connoting negativity and giving rise to such terms as slums and ghetto, used in conjunction with inner city to typify violence, drug use, and poverty [4].

The causes of poverty across inner cities in the US have long been a part of academic, economic, and political discourse, with many theories and explanations offered [1]. Overall, there are eight primary causes of poverty across inner cities that include: 1) the effect of structural economic shifts; 2) inadequate human capital; 3) racial and gender discrimination; 4) an interaction of culture and behavior; 5) spatial mismatch; 6) migration; 7) endogenous growth deficit; and 8) public policy [1]. These hypotheses span disciplines and broadly represent research across economics, population health, societal structures, and geographic location [1]. Taken together, evidence suggests that a combination of factors have led to sustained poverty in the inner city, with the persistence of this poverty largely attributed to ineffective efforts implemented downstream to address proximal correlates of poverty rather than taking a systematic approach.

The health consequences as a result of decades of poverty that are occurring throughout inner cities in the US have been aptly captured by Andrulis who describes “deterioration of inner cities and their social conditions joining with poverty to create an urban health penalty that profoundly handicaps the well-being of communities”[4]. This description led to efforts by the American College of Physicians to issue a position on the health care of inner cities in 1997 [5]. This included cataloguing the underlying factors across the societal level and recommending models for care to improve the health of inner-city populations [4]. An uptake of medical research examining the challenges that inner city populations experience across individual, community, and health systems levels has since been observed [6]. The body of evidence that has been generated over the last several decades denotes the longstanding, systemic challenges, and barriers that exist for inner-city populations that persist to date [6].

While inner-city populations have long been considered among the nation’s most vulnerable, the inter-generational transmission of poverty and poor health persists due to poor and inadequate access to care, further compounded by adverse social and environmental risk factors [4]. Recent efforts are emerging suggesting a multifaceted approach to addressing the health and well-being of the inner-city using a population health approach [6]. However, given the longstanding state of poverty, such approaches necessitate a paradigm shift in the improvement of health within inner cities. This article therefore aims to present a framework for improving health among inner-city populations using a multidisciplinary approach drawn from medicine, economics, and emergency response interventions through presentation of a case study from the city of Milwaukee, WI. It is important to acknowledge and specify however the use of the term inner city at the outset.

Debates surrounding the use of the term inner city are longstanding, [4] with recent mainstream efforts suggesting the term be replaced as it serves as a euphemism symbolizing violence and drug ridden communities used to characterize social issues faced by many minority populations [7]. Other scholars suggest the validity of the term as defined by an “urban community as an integrated whole with subpopulations, diversity, major problems, urban renewal and related initiatives all a part of a whole” [4]. The perspective presented in this paper aligns more closely with the latter definition. However, the perspective presented here not only views the term inner city from the perspective of academic medicine and health disparities, but holds that the term inner city has historic meaning; describing the state of economic, social, and environmental deterioration due to the systematic removal of resources, followed by attempts to further isolate and segregate communities living on the margins of society. Whether all scholars embrace or agree with the use of the word inner city, the critical and salient point remains that inner-city environments continue to experience extreme levels of poverty, poor health outcomes, and generational cycles of deprivation. These cycles not only preclude upward mobility due to limited economic opportunity, but alter health trajectories as a result of social, structural, and environmental deterioration. To eliminate the term inner city not only negates the historic events but runs the risk of relegating the needs of our society’s most vulnerable to the background. For this reason, this perspective and subsequent work continue to use the term inner city to emphasize the imperative of addressing the health of populations who, while sitting at the heart of many major cities across the US, now reside on the margins of society.

Patient Information

The city of Milwaukee is the state of Wisconsin’s largest city with approximately 600,000 residents according to the 2013 census [8]. Milwaukee is one of few cities in the United States that is a majority minority city and is also one of the most segregated cities in the nation [9]. Milwaukee is the second poorest city in the US, second only to Detroit, for cities with greater than 500,000 residents [9]. Preliminary work has shown that the health of inner-city Milwaukee is impacted by a number of factors that may be considered vulnerabilities. These include discrimination, poverty, segregation, and food insecurity.

As the first phase in a coordinated effort to address health disparities, high crime, high poverty, and racially segregated neighborhoods in inner city Milwaukee, our research team used qualitative methods to understand the impact of the built environment on stress and the negative effect it has on cardiovascular disease risk factors among African Americans. We conducted 29 focus groups, 40 key stakeholder interviews and 10 photovoice interviews with a total number of over 350 community participants and community leaders across 10 zip codes in inner city Milwaukee. Key stakeholders represented multidisciplinary backgrounds including healthcare, public education, public housing, churches, police departments, fire departments, community-based organizations, and civic agencies. The rationale behind qualitative methods was to foreground the lived experience and voice of the patients in their own words. Photovoice specifically is a well-established methodology used in participatory action research and allows participants to serve as co-researchers by collecting data through images that reflect their own perspectives of strengths, weaknesses, barriers, and facilitators within their community. As originally described by Wang and Burris (1997) [10], photovoice serves as a powerful tool to generate dialogue and impact policy. All interviews and focus groups were led using a semi-structured interview guide and moderator guide to facilitate discussions around the role of poverty and health within inner cities. Stakeholders included representatives across government and community organizations including the Milwaukee Health Department, Milwaukee Fire Department, public officials including Aldermen, judges, and public defenders, representatives from the YMCA, YWCA, Boys and Girls Club, local food pantries, and local churches. Focus group participants included individuals with and without chronic disease and photovoice participants included individuals with chronic disease, all ranging in age from 19 through 70. Grounded theory approach was used with constant comparison to identify themes as they emerged through interviews and focus groups.

Findings

Major themes identified across interviews, focus groups, and photovoice sessions for barriers to managing health in the community included the role of stress, specifically resulting from constant experiences of violence, discrimination, racism, crime, residential segregation and incarceration. For example, participants stated:

“We wonder if when our kids walk out the door if they are going to make it home. I think that is the stress in my eyes that there is so much happening. My stress is coming from some of the, I don’t claim I am sick, but that is where a lot of the stress come from. Kids in school, kids getting shot. I was sitting in my house one night and a bullet came through my window. That is where stress comes from.”

“I served in Afghanistan. Living in inner city Milwaukee is like serving in Afghanistan. The difference is you do not get hazard pay.”

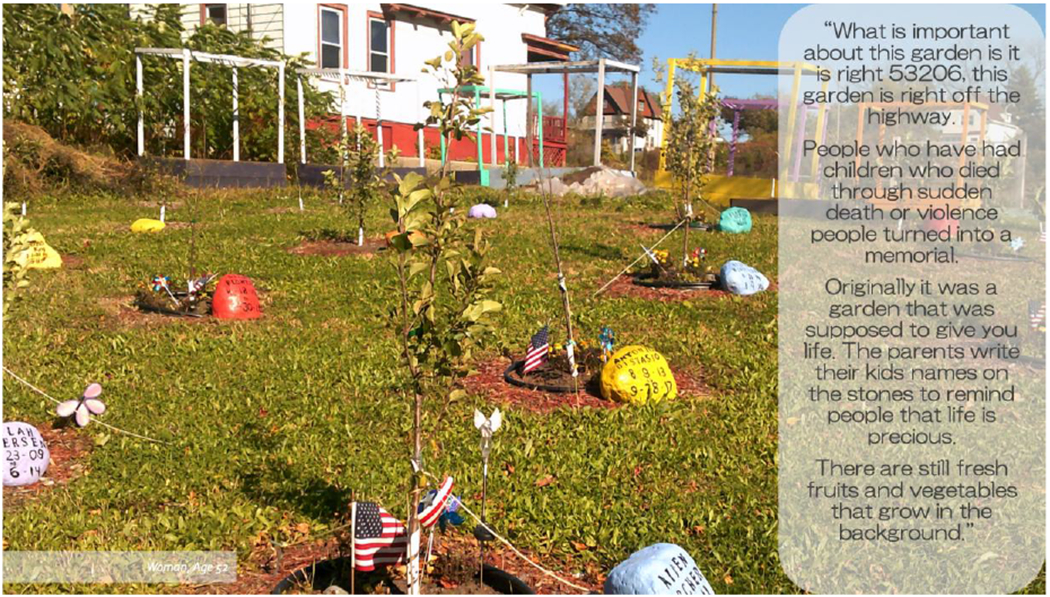

Image 1 was presented during a photovoice session to capture the extent to which community members have been exposed to traumatic stress and the response:

Image 1.

Parents write their kids’ names on the stones to remind people that life is precious. It depicts the impacts of cycles of poverty on the community and limited resources to care. It captures the extent to which community members have been exposed to traumatic stress.

Additional themes included the impact of cycles of poverty on the community, and limited resources to care for health. Limited resources included lack of transportation to clinic visits, the high cost of healthy food and stable housing, and a lack of access to education and unemployment. For example:

“Stress is a very big factor. Other factors are the lack of community resources and the lack of family resources, high unemployment and general urban stress= crime, violence, anything that affects the health of individuals.”

“Access to health care and high cost of medication. With age comes illness, living on fixed income and paying for medication is very hard and you have to make choices of what you will pay for. Some people have very good benefits and that helps but when you don’t have it is very very stressful. You ignore being sick because you know you cannot afford it.”

Image 2 was presented during a photovoice session to demonstrate the stress that occurs when medications cannot be afforded, and strategies used to cope:

Image 2.

Medication for chronic disease management which often cannot be afforded.

Participants also discussed substance abuse and a sense of hopelessness that resulted from the social factors dominating their lives. They regularly tied these experiences back to stress and trauma, which they believed resulted in poor health and disability.

“A lot of people do not expect good health for themselves, so they are willing to accept or ignore issues regarding their health. Because people feel they will not be treated seriously they avoid seeking treatment but also minimize, deny, and use substances so they don’t have to think about it. There is a lot of trauma which adds complexity to the health issues.”

“Stress plays a huge role. Trauma is a very destructive form of stress. Exposure to the stress is only part of it, the damaging part is that there is actual harm that is done to the brain. That kind of stress is very toxic and disables your sense of safety and security. It causes you to develop a narrow and comprised vision of what your life could be. Stress has so many organic effects on blood pressure, sleep, concentration, hormones. I think a lot of obesity is tied to stress and then it is complicated when living in food deserts.”

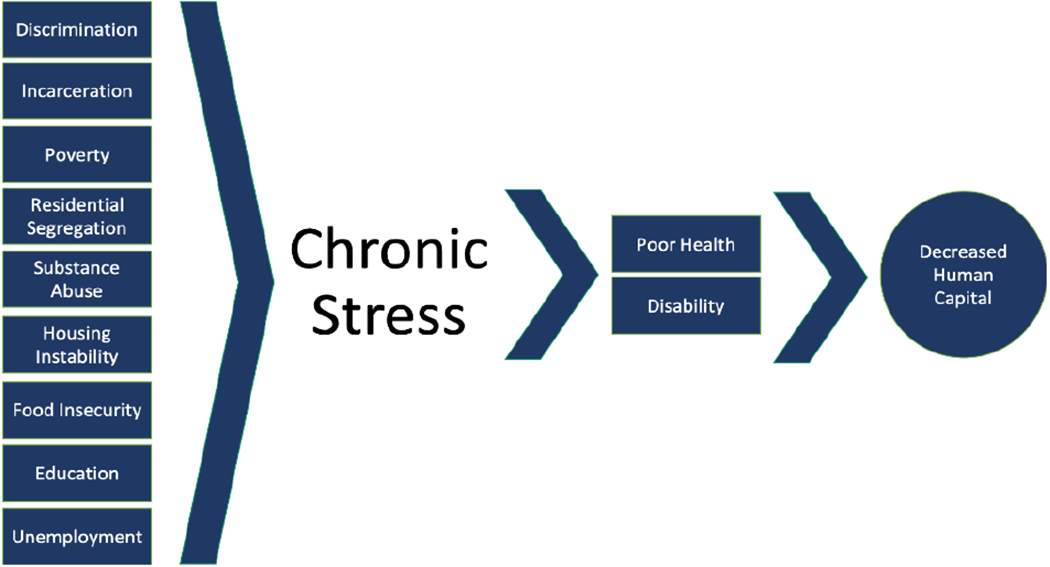

Initial review using grounded theory provided key themes that was used to develop the conceptual model in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Framework Highlighting Vulnerability and Hazards of Inner-City Man-Made Disaster Zones.

Current Challenges

Using this framework in Figure 1, human capital, is a measure of knowledge, skills, health, resilience, and values that people obtain throughout their lives, positioning them to achieve self-actualization [11, 12]. These intangible forms of capital have the ability to increase earnings and improve one’s health overtime, increasing their contribution to society [11, 12]. The World Bank maintains that health is a key component of human capital as people are more productive in society when they are healthier [11, 13]. The development of human capital, a central driver of sustainable growth and poverty reduction, can be used to bring an end to extreme poverty by investing in people through increasing access to and provision of adequate nutrition, health care, quality education and jobs [11]. Even though human capital is a key aspect of economic growth, policy makers find it challenging to make the case for human capital investments due to the length of time necessary for the benefits of investing in people to materialize [11]. Building roads and bridges can rapidly generate economic and political benefits, however, the human capital of young children will not deliver economic returns until those children become adults and join the workforce [11]. Due to this slow return on investment, countries often underinvest in human capital and miss the opportunity to create a cycle of increased human capital and growth [11].

In addition to healthcare, education and training have been identified as important investments in human capital [12, 13, 14]. While it is known that higher education can increase one’s human capital and earning potential, racial and ethnic minorities face more barriers compared to their non-Hispanic White counterparts to graduating from high school and entering and finishing college [12, 14]. The costs of achieving a higher education have risen more for non-Hispanic Black college students compared to non-Hispanic Whites due to a higher percentage of blacks coming from low-income families participating in government subsidized programs [12]. Unfortunately, cuts in federal grants for non-Hispanic Blacks substantially raised the cost of a college education for this group, further exacerbating the impact [12].

Ethnic minorities often face barriers to achieving an optimal education, and hence increasing their human capital, prior to birth. For example, proper nutrition in utero and in early childhood improves children’s physical and mental well-being [11]. Studies show that school children with healthier diets significantly increase their achievements while underweight and obese children have lower IQ scores than healthy-weight children [11]. Poorer youth health status remains a barrier for high school and college degree completion [11]. While income directly influences the availability of food, health care, and housing, financial strain also hinders child development through lack of medical care, living in illness-inducing environments and poverty [15, 16]. Because of economic limitations, parents living in poverty have more difficulty providing intellectually stimulating materials such as books, games, quality day-care, or preschool opportunities that are essential for positive child development [15]. Children who have lived on welfare for extended periods of time are significantly less healthy, have more developmental problems, are more than twice as likely to fail in school, and are more likely to have serious conduct and discipline problems compared to children not living on welfare [16, 17]. Children who experience behavioral and learning challenges are also less likely to graduate high school, less likely to go to college, and less likely to actively participate in the labor force [18].

Health disparities experienced by racial/ethnic minorities and individuals living in low socioeconomic status environments can thus be framed within the construct of human capital. Unemployment and underemployment are chronic factors limiting human capital despite programs initiated to support individuals with financial difficulty. Research on welfare to work programs show that half of welfare recipients do not have a high school degree or equivalent and while many recipients are able to find a job, a large proportion lose the job within the first year of employment [19]. Employment has also been positively associated with perceived health, with non-working women reporting themselves as less healthy compared to those who were working [20]. Women on welfare are at high risk of having mental health problems, [19] and health problems account for about 10% of all job losses in government sponsored programs [21]. Individuals whose government benefits are terminated due to noncompliance with the work component of the welfare-to-work program report serious personal or health issues as the primary reason for non-compliance [22]. Finally, research shows that being in good health increases the likelihood of being in the workforce and keeping a job for both men and women [23]. As racial/ethnic minorities are disproportionately impacted by chronic conditions like obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, and stroke, potential economic and societal contributions are also missed largely due to missed workdays and loss wages [24, 25]. This limitation of human capital within specific groups adds a layer of complexity to the discussion of health disparities that is often overlooked.

Proposed Intervention Approach and Conceptual Model

The above case summary illustrates the historical challenges facing inner-cities, the patient perspective of how the inner city impacts health, and the current challenges and factors that converge, sealing health trajectories for those who live within an inner city. What follows is the proposed intervention approach that accounts for the acute and chronic state of inner-city health by drawing from emergency response interventions under the umbrella of disaster response while focusing on increasing human capital as a long-term outcome.

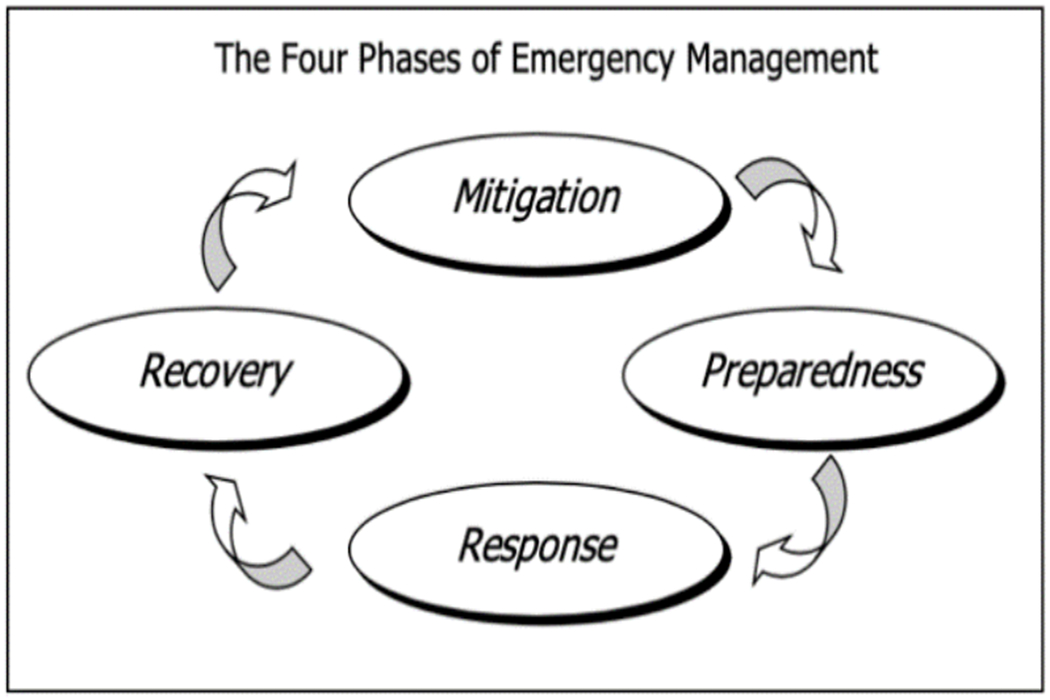

Disaster responses are well established in the literature and have been incorporated into many ethical standards [26]. Such disaster responses typically occur as emergency responses and can be characterized in four phases that include mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery [27]. These phases can be seen as cyclical, as seen in Figure 2, with mitigation dealing with prevention both before and after an event takes place. As such, mitigation may focus on preventing future emergencies or minimizing the effect of existing events. The recovery period is intended to return the location of a disaster to normal, or if possible, a safer situation following the emergency.

Figure 2.

Cyclical Nature of Emergency Response (WHO, 2000)

The nature of disaster response often reflects the type of the disaster, i.e. man-made versus natural, as well as the timing, duration, and location of a disaster as critical considerations [28]. Timing can be typified as either rapid or slow emerging, with duration consisting of a finite period from hours to weeks, or conversely being indefinite and persistent for years [28]. As disasters often result in mass casualties and debilitation of the communities in which they occur, disaster response is a matter of national and international concern across public health agendas. Disaster responses are most often focused on rehabilitation and provision of resources for basic needs to be met to redress the loss of life, the loss of capability, and the loss of stability across human and economic agency.

In comparison to this framework, the current approach to inner-city environments has been primarily a social framework that focuses on relief programs such as income assistance, housing subsidies, and food assistance [29]. This social framework, though necessary, does not encompass the full scope of needs that exist when viewing an inner city as a man-made disaster in need of a disaster response. Social relief programs focused on basic needs do not address the concurrent existing loss of capability or capacity of the community, or the lack of stability at both human and economic levels.

Economic models would incorporate building economic sustainability at the individual and community level, aiming to foster wealth creation rather than simply meeting immediate economic or social needs [29]. A key attribute of economic productivity along with physical capital such, as buildings, is human capital, characterized as aggregate levels of education, training, and skills that exist in a population [12, 30; Schulz, 1961]. A new measure of human capital incorporates not only education, but health to understand how to increase economic growth and monitor investments [31]. Similar to low-income and middle-income countries, investments in inner cities into human capital tends to be much lower than investments into physical capital [32]. Therefore, within the framework of inner-city environments as disaster areas, a comprehensive emergency management response would include efforts to prevent and/or minimize damaging effects, including investments that help individuals meet social needs, while at the same time expanding the economic and educational opportunities, and meeting health needs in a way that improves human capital and economic productivity. Indeed, several disaster emergency response interventions have been developed to address the needs of disaster victims. Programs focusing on enhancing the immediate short-term and on-going long-term needs of victims through information gathering, practical assistance, problem-solving skills building, connection with social support and linkage with collaborative services have been found to be particularly successful [33, 34]. Furthermore, interventions that are culturally informed and that include strategies for building community resilience, replenishing social and economic resources that will restore living conditions, and establishing partnerships with community leaders (e.g., faith-based leaders, and community- based organizations) to promote disaster preparedness, crisis knowledge, and post-disaster service utilization have been shown to have positive effects on the overall well-being of disaster victims [35, 36, 37, 38]. Adaptation of these programs to inner-city environments would address well-established health disparities at individual and community-level and would serve to minimize the effect of existing disasters as well as preventing future events through addressing most pressing basic and social needs, increasing knowledge and skill-base for managing daily hazards, and connecting with relevant community-based resources.

Conclusion

Taken together, the approach presented in this case study places focus on sustained efforts to address existing needs, followed by capacity building to prevent future disasters [28]. This mind set is greatly needed when seeking to address the health of inner-city populations who experience pervasive levels of chronic stress and hopelessness. By deploying resources to build on the strengths of a community, efforts using a disaster framework can lift the burden from the patients’ lived experience presented here.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This project was supported by grant from Advancing Healthier Wisconsin (PI: Egede). Funding organization had no role in the analysis, interpretation of data, or writing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: All authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to participate: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish: Patients consented to publishing their data and photographs.

Data Availability: Data for qualitative findings used for this study is available upon request from LEE

References

- 1.Teitz MB, Chapple K. The causes of inner-city poverty: eight hypotheses in search of reality. Cityscape. 1998;1:33–70. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mills ES, Lubuele LS. Inner cities. J Econ Lit. 1997;35(2):727–56. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson WJ, Aponte R. Urban poverty. Annu Rev Sociol. 1985;11(1):231–58. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrulis DP. The urban health penalty: new dimensions and directions in inner-city health care. In: Inner-City Health Care. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians; 1997. no 1. (Available from: American College of Physicians, Independence Mall West, Sixth Street at Race, Philadelphia, PA 19106). [Google Scholar]

- 5.American College of Physicians. Inner-city health care. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:485–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell JA, Egede LE. Individual-, community-, and health system–level barriers to optimal type 2 diabetes care for inner-city African Americans: an integrative review and model development. Diabetes Educ. 2019;5:0145721719889338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Axel-Lute M 4 reasons to retire the phrase “inner city”. Shelter Force. 2017; Accessed from: https://shelterforce.org/2017/05/23/4-reasons-to-retire-the-phrase-inner-city/. Accessed 2 Feb 2020.

- 8.CensusScope available at www.censusscope.org based on William H. Frey and Dowell Myers’ analysis of Census 2000. Accessed 19 Mar 2018.

- 9.Jacobs H, Kiersz A, Lubin G. The 25 most segregated cities in America. Business Insider. 2013. www.businessinsider.com/most-segregated-cities-in-america-2013-11. Accessed 15 Feb 2020.

- 10.Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24(3):369–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Bank. The human capital project. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2018. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/30498/33252.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y. Accessed 15 Feb 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Becker GS. Human capital. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1964. https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/HumanCapital.html. Accessed 15 Feb 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stein F, Sridhar D. Back to the future? Health and the World Bank’s human capital index. BMJ. 2019;367:15706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becker GS. Human capital: a theoretical and empirical analysis with special reference to education. 3rd ed. National Bureau of Economic Research: The University of Chicago Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zill N, Moore K, Smith E, Stief T, Coiro MJ. The life circumstances and development of children in welfare families: a profile based on National Survey Data. Washington, DC: Child Trends; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elman C, Wray LA, Xi J. Fundamental resource dis/advantages, youth health and adult educational outcomes. Soc Sci Res. 2014;43:108–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wise PH, Meyers A. Poverty and child health. Pediatr Clin N Am. 1988;35:1169–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sum A The consequences of dropping out of high school: Joblessness and jailing for high school dropouts and the high cost for taxpayers. In: Center for Labor Market Studies. Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts. 2009. https://repository.library.northeastern.edu/downloads/neu:376324?datastream_id=content. Accessed 2 Feb 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Danziger SK, Kalil A, Anderson NJ. Human capital, physical health, and mental health of welfare recipients: co-occurrence and correlates. J Soc Issues. 2000;56(4):635–54. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anson O, Anson J. (1987). Women’s health and labour force status: an enquiry using a multi-point measure of labour force participation. Soc Sci Med. 1987;25(1):57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hershey AM, Pavetti LA. Turning job finders into job keepers. The Future of Children. 1997; 10.2307/1602579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fraker T Iowa’s limited benefit plan. In: Office of planning, research, & evaluation. 1997. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/resource/iowas-limited-benefit-plan-executive-summary. Accessed 5 Mar 2020.

- 23.Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Does employment affect health? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:230–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oates GR, Jackson BE, Partridge EE, Singh KP, Fouad MN, Bae S. Sociodemographic patterns of chronic disease: how the mid-south region compares to the rest of the country. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(Suppl 1):S31–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Druss BG, Marcus SC, Olfson M, Tanielian T, Elinson L, Pincus HA. Comparing the national economic burden of five chronic conditions. Health Aff. 2001;20(6):233–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cline RJ, Orom H, Berry-Bobovski L, Hernandez T, Black CB, Schwartz AG, et al. Community-level social support responses in a slow-motion technological disaster: the case of Libby. Montana Am J Community Psychol. 2010;46(1–2):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. IFRC World Disaster Report. 2000. http://apps.who.int/disasters/repo/7656.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2020.

- 28.Leider JP, DeBruin D, Reynolds N, Koch A, Seaberg J. Ethical guidance for disaster response, specifically around crisis standards of care: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(9):e1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Porter ME. The Competitive Advantage of the Inner City. In: Harvard Business Review. 1995. https://hbr.org/1995/05/the-competitive-advantage-of-the-inner-city. Accessed 5 Jan 2020.

- 30.Schultz TW. Investment in human capital. Am Econ Rev. 1961;51:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim SS, Updike RL, Kaldjian AS, Barber RM, Cowling K, York H, et al. Measuring human capital: a systematic analysis of 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016. Lancet. 2018;392:1217–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim JY. The human capital gap. Foreign Aff. 2018;92:102. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Litz BT, Gray MJ, Bryant RA, Adler AB. Early intervention for trauma: current status and future directions. Clin Psychol. 2002;9(2):112–34. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berkowitz S, Bryant R, Brymer M, Hamblen J, Jacobs A, Layne C, et al. The National Center for PTSD & the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, skills for psychological recovery: field operations guide. Washington, DC and London: American Psychiatric Pub; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eisenman DP, Zhou Q, Ong M, Asch S, Glik D, Long A. Variations in disaster preparedness by mental health, perceived general health, and disability status. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2009;3(1):33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galea S, Tracy M, Norris F, Coffey SF. Financial and social circumstances and the incidence and course of PTSD in Mississippi during the first two years after hurricane Katrina. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21(4):357–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lachlan KA, Spence PR. Crisis communication and the underserved: the case for partnering with institutions of faith. J Appl Commun Res. 2011;39(4):448–51. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plough A, Fielding JE, Chandra A, Williams M, Eisenman D, Wells KB, et al. Building community disaster resilience: perspectives from a large urban county department of public health. A J Public Health. 2013;103(7):1190–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]