Abstract

Objectives:

To explore the anxiolytic effects of a 4-month randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exercise and anti-depressant medication in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), and to examine the potential modifying effects of anxiety in treating depressive symptoms.

Materials and Methods:

In this secondary analysis of the SMILE-II trial, 148 sedentary adults with MDD were randomized to: (a) Supervised Exercise, (b) Home-Based Exercise, (c) Sertraline, or (d) Placebo control. Symptoms of state anxiety measured by the Spielberger Anxiety Inventory (STAI) were examined before and after four months of treatment. Depressive symptoms were assessed by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) and Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II). Analyses were carried out using general linear models.

Results:

Compared to placebo controls, the exercise and sertraline groups had lower state anxiety scores (standardized difference = 0.3 (95% CI = −0.6, −.04, p = 0.02) after treatment. Higher pre-treatment state anxiety was associated with poorer depression outcomes in the active treatments compared to placebo controls for both the HAMD (p = 0.004) and BDI-II (p = 0.02).

Conclusion:

Aerobic exercise as well as sertraline reduced symptoms of state anxiety in patients with MDD. Higher levels of pre-treatment anxiety attenuated the effects of the interventions on depressive symptoms, however, especially among exercisers. Patients with MDD with higher comorbid state anxiety appear to be less likely to benefit from exercise interventions in reducing depression and thus may require supplemental treatment with special attention to anxiety.

Keywords: Exercise, Depression, Anxiety, Sertraline, Randomized Clinical Trial

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common mental disorder, with a lifetime prevalence of 15-20% of the United States population (Hasin, et al., 2018). Anxiety disorders are even more ubiquitous, and commonly co-occur with MDD. An estimated 85% of adults with depression experience significant symptoms of anxiety (Gorman, 1996), and 58% with lifetime depression have a diagnosable anxiety disorder during their lifetimes (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005; Kessler, Nelson, McGonagle, Liu, Swartz, & Blazer, 1996). Among patients presenting in primary care settings, more than 75% of patients diagnosed with MDD also suffer from an anxiety disorder (Olfson et al., 1997) and comorbid anxiety may be highly prevalent among patients with coronary artery disease engaged in cardiac rehabilitation (Lavie & Milani, 2004). Comorbid anxiety disorders have important prognostic value, predicting greater chronicity and severity of depressive illness (Coryell, Endicott, & Winokur, 1992; Sherbourne & Wells, 1997), lower rates of treatment response (Dunlop et al., 2017; Trivedi et al., 2006), and higher suicide risk (Allgulander & Lavori, 1993; Johnson, Weissman, & Klerman, 1990). More severe anxiety is asociated with increased likelihood of discontinuation from treatment (Fawcett, 1997) and decreased response to anti-depressant medications (Dunlop et al., 2017; Steffens & McQuoid, 2005; Davidson, Meoni, Haudiquet, Cantillon, & Hackett, 2002).

Antidepressant medication and evidenced-based psychotherapy are widely considered to be the treatments of choice for MDD (Cuijpers, Sijbrandij, Koole, Andersson, Beekman, & Reynolds, 2014). Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have generally reported response rates of 30-45% with single action or dual action antidepressant monotherapy (Cipriani et al., 2018; Schulberg, Madonia, Block, Coulehan, Scott, Rodriguez, & Black, 1995) and up to 67% for patients receiving augmentation with additional medications (Craighead & Dunlop, 2014; Rush et al., 2006).

Aerobic exercise also has been shown to have antidepressant effects (Cooney et al., 2013; Josefsson, Lindwall, & Archer, 2014; Krogh, Videbech, Thomsen, Gluud, & Nordentoft, 2012; Morres et al., 2019), and has been associated with rates of MDD remission that are comparable to pharmacotherapy (Blumenthal et al., 1999). The effects of exercise on anxiety have been less widely studied, but there is suggestive evidence that exercise also may successfully reduce anxiety symptoms (Stonerock, Hoffman, Smith, & Blumenthal, 2015; Lavie & Milani, 2004). However, the extent to which exercise may reduce symptoms of anxiety in patients with MDD is uncertain, and whether the presence of comorbid anxiety may modify the efficacy of exercise in the treatment of depression is not known.

There are a variety of reasons why comorbid anxiety might affect or even compromise otherwise efficacious treatments, including exercise, for depression. For example, depressed patients who are also anxious, may present a different pattern of dysregulated pathophysiology that may not be amenable to standard therapies. Comorbid anxiety also might give rise to avoidance behaviors, and, consequently, limit engagement in treatment or result in premature dropout.

To our knowledge, no studies have compared the effects of exercise and an SSRI on symptoms of anxiety in patients with MDD. The present study reports an analysis of data from the SMILE-II study (Blumenthal et al., 2007), in which patients diagnosed with MDD were randomized to aerobic exercise (home-based or supervised), antidepressant medication (sertraline), or placebo. We previously reported (Blumenthal et al., 2007) that after 4 months of treatment, participants undergoing aerobic exercise achieved comparable benefits to those patients receiving sertraline, with both active treatments tending to show greater improvement in depressive symptoms relative to placebo controls. The present report examines the effect of exercise and sertraline on symptoms of anxiety, and considers whether the presence of co-morbid anxiety prior to treatment modifies the efficacy of the treatments for reducing depressive symptoms.

METHOD

This study was approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board and all patients provided written informed consent. Participants in the SMILE II study were enrolled between October 2000 and November 2005.

Patient eligibility.

Outpatients were initially screened using the 21-item Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II). Participants obtaining a BDI-II score of ≥12 were evaluated by a clinical psychologist (BH) using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1995) to diagnose MDD using criteria based on the Structured Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). The17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) also was used to assess MDD severity. Eligibility criteria also included age ≥40 years, sedentary (i.e., no current involvement in regular exercise), and no current psychiatric treatment. Exclusion criteria included a history of bipolar disorder or psychosis; medical comorbidities that would preclude participation in the trial (e.g., significant musculoskeletal difficulties); current use of antidepressants or other psychotropic medications; dietary supplements or herbal therapies with purported psychoactive indications; current active alcohol or drug abuse or dependence; and active suicidal intent.

Interventions

Participants were randomly assigned to one of four 16-week study conditions:

1. Supervised Aerobic Exercise.

Participants attended three 45-minute exercise groups each week in which they were supervised by exercise physiologists. Participants were assigned individualized target heart rate (HR) ranges of between 70 and 85% of their HR reserve.

2. Home-Based Aerobic Exercise.

Participants completed an initial training session with an exercise physiologist, and then exercised three times weekly at home, following an exercise program similar to that described above. They also had two follow-up sessions--one after the first month and a second after 2 months--to assess and encourage adherence to the home-based exercise prescription and to problem-solve any barriers to adherence.

3. Sertraline.

Participants received sertraline, a selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). Participants met with a staff psychiatrist at the time of randomization and at weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16. Treatment was initiated at 50 mg daily and titrated until a well-tolerated therapeutic dosage of up to 200 mg daily was achieved.

4. Placebo pill.

As with the Sertraline condition, participants met with a staff psychiatrist for 6 visits, and treatment was titrated up to 200 mg daily. Participants and study staff were blind to the pill condition.

Psychological Measures

Depression assessment.

To assess the diagnosis of depression, we used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Depression Module (SCID) (Robins, Helzer, Croughan, & Ratcliff, 1981) to diagnose depression and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Hamilton, 1960) to quantify the severity of depressive symptoms.

Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996):

The 21-item BDI-II is a widely used self-report measure of depression with scores ranging from 0 to 63, with higher scores suggesting greater depressive symptoms; scores ≥ 14 are suggestive of clinically significant depressive symptoms.

Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-State (STAI) (Spielberger & Gorsuch, 1970):

The 20-item STAI – State was used to assess levels of anxiety with scores ranging from 20 to 80; scores ≥ 40 suggest clinically significant anxiety.

Statistical Analyses

This secondary analysis is based on a subset of data used in our primary report (Blumenthal et al., 2007). Following our approach in the primary paper, we eliminated 14 early responders from our analysis and further restricted the sample to include only those participants who completed post-intervention assessments. Descriptive statistics were generated using median and interquartile range for continuous variables and percent and frequency for categorical variables. We used the rms and interactions package in R (https://cran.r-project.org/) for all analyses.

Parallel to the approach used in our primary paper, we evaluated treatment effects by specifying two a prioricontrasts: 1) the three active treatments with the placebo group, and 2) the two exercise groups with the sertraline group. We hypothesized that a) following treatment, participants in the active interventions (exercise and sertraline) would report lower state anxiety compared to placebo controls; and b) participants in the active interventions with higher state anxiety at baseline would show smaller reductions in depressive symptoms compared to those participants with low baseline state anxiety.

We estimated the effect of the interventions on state anxiety using the general linear model, including post-treatment anxiety as the dependent variable, and pre-treatment anxiety, pre-treatment HAMD, age, gender, race, and the two aforementioned treatment contrasts on the predictor side of the equation. To examine the potential modifying effects of baseline anxiety levels, we examined two models: one for each of the two depression measures (i.e., HAMD and BDI-II). Each model specified the post-intervention level of depressive symptoms as the dependent variable. Independent variables were the pre-treatment level of the corresponding depression measure, age, gender, race (Black, White, Other), pre-treatment level of anxiety, two orthogonal treatment contrast main effects, and two treatment group contrasts by anxiety interaction terms. When the null hypothesis for an interaction was rejected we probed the interaction using the Johnson-Neyman technique as available in the “interactions” package in R. Age, state anxiety, and pre-treatment depression and anxiety were modeled as continuous variables. After examining model residuals, the depression measures were transformed using the square root function (a generalized linear model with gamma distribution yielded identical results). Values were subsequently transformed back to approximate the original metric for graphical presentation. Statistical tests were two-sided. An alpha of 0.05 was used as the criterion for statistical significance. No correction for familywise error rate was made.

RESULTS

Participants.

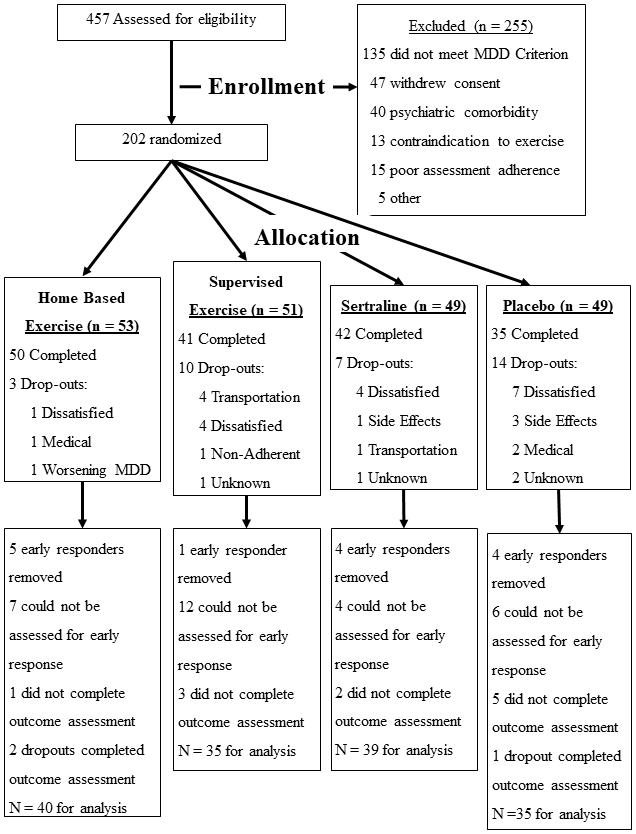

Figure 1 displays the flow of participants from initial screening to the final analysis sample. Two hundred two participants were enrolled in the primary trial. After removing the 14 early responders (i.e., those with >50% reduction in BDI-II scores after only one week of treatment) and 40 participants who did not have interim depression data or post-treatment assessments for at least one measure, the final sample size was 148. Demographic and baseline anxiety and depression characteristics were comparable across the four treatment groups (Table 1). The majority of participants were white, female, and middle aged, with a median age of about 51 years. Pre-treatment levels of depression symptoms were considered to be in the mild to moderate range for both the HAMD and BDI-II; 85% of the sample had STAI scores ≥ 40, suggesting the presence of significant comorbid anxiety in the majority of participants.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participant recruitment and retention throughout the study.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| N | Home Exercise |

Supervised Exercise |

Sertraline | Placebo | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=40) | (N=35) | (N=39) | (N=34) | ||

| Male % (N) | 148 | 28%(11) | 17%(6) | 28%(11) | 26%(9) |

| Race % (N) | 148 | ||||

| Black | 28%(11) | 23%(8) | 21%(8) | 26%(9) | |

| White | 65%(26) | 74%(26) | 77%(30) | 68%(23) | |

| Other | 148 | 8%(3) | 3%(1) | 3%(1) | 6%(2) |

| Age (yrs) | 148 | 49/54/57 | 44/51/58 | 46/51/55 | 44/50/56 |

| Pre-treatment HAMD | 148 | 15/17/20 | 14/17/20 | 13/16/18 | 13/16/19 |

| Pre-treatment BDI | 147 | 27/30/35 | 24/31/36 | 24/30/35 | 24/30/37 |

| Pre-treatment state anxiety | 147 | 45/52/57 | 43/47/54 | 43/49/54 | 43/48/57 |

| State anxiety ≥40 | 147 | 94%(37) | 83%(29) | 80%(31) | 85%(29) |

Value for categories are percent of group (N). For continuous variables, values are 25th percentile/Median/75th percentile.

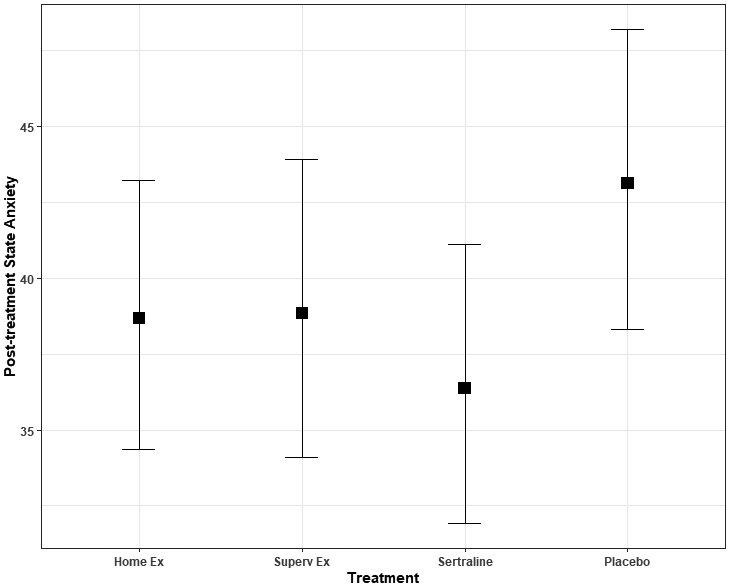

Effects of Treatment on Anxiety.

Figure 2 displays the adjusted STAI post-treatment means for each treatment group, while Table 2 provides the p-values for each model term in the analysis. At the conclusion of the 4-month interventions, the active treatment groups had lower post-treatment STAI scores compared to placebo controls (standardized difference = 0.3 (95% CI = −0.6, −.04, p = 0.02). There was no statistically significant difference in post-treatment anxiety scores in the sertraline group compared to the exercise groups (standardized difference = All exercise vs. sertraline = 0.13 (95% CI = −0.11, 0.37, p = 0.29).

Figure 2.

Post-treatment state anxiety. Values represent post-treatment state anxiety scores, adjusted for age, race, gender, pre-treatment HAMD score, and pre-treatment levels of corresponding anxiety score. After treatment, state anxiety was lower for the active treatments compared to placebo (p = .029). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Table 2.

P-values for treatment effect on state anxiety

| Factor | d.f. | p-values |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1 | 0.246 |

| Gender | 1 | 0.756 |

| Race | 2 | 0.022 |

| Pre-treatment HAMD | 1 | 0.651 |

| Pre-treatment anxiety | 1 | < 0.0001 |

| All treatment vs. placebo | 1 | 0.022 |

| All exercise vs. sertraline | 1 | 0.290 |

Standardized effect sizes for contrasts:

All treatment vs. placebo = 0.30 (95% CI = −0.6, −.04);

All exercise vs. sertraline = 0.13 (95% CI = −0.11,0.37)

We also observed a race difference in the adjusted levels of state anxiety after treatment. Whites had higher anxiety scores compared to Blacks (standardized difference = 0.5 [95% CI = 0.1, 0.8], p = 0.02). Not surprisingly, pre-treatment state anxiety was strongly related to post-treatment state anxiety, p < .001.

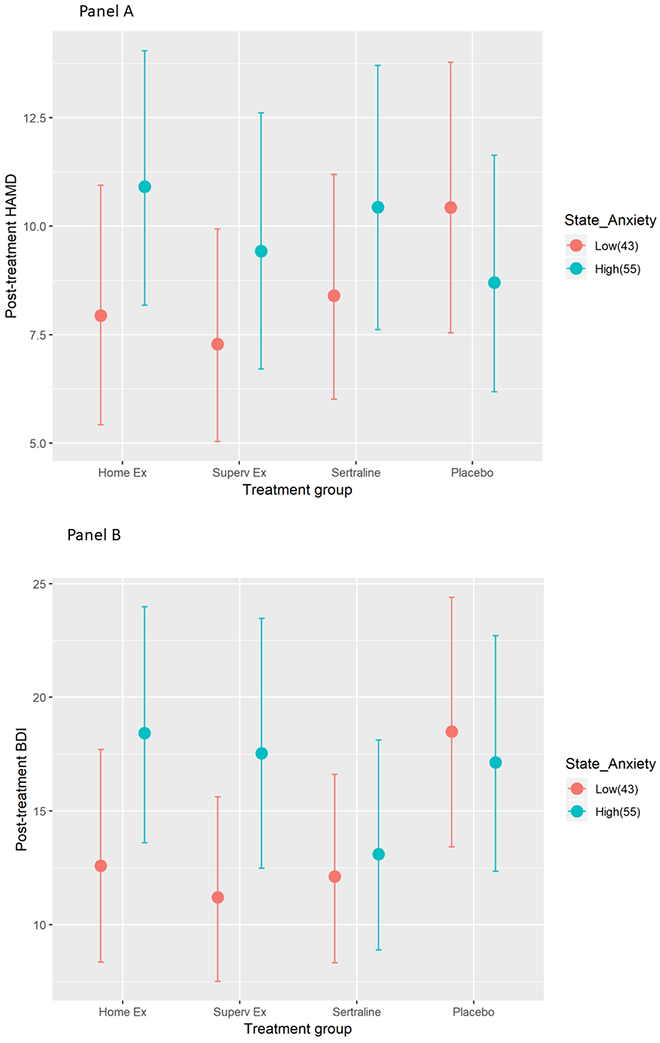

Moderating Effects of Anxiety on Depressive Symptoms.

Table 3 provides the p-values and effect sizes for each term in the interaction models. We observed evidence for a baseline state anxiety by treatment group interaction for both the HAMD (p = 0.004) and the BDI-II (p = 0.02). Among participants in the three active treatments, participants with lower pre-treatment state anxiety scores achieved lower post-treatment HAMD scores compared to placebo controls with low state anxiety (Figure 3, Panel A). Further, examination of within-treatment group differences revealed that the largest within-group differences between those with high and low pre-treatment anxiety were observed among those participants in the exercise conditions. A similar pattern was observed for the BDI-II, although it appeared that there was little effect of baseline anxiety on post-treatment BDI-II scores for the sertraline group (Figure 3, Panel B). Further, placebo controls with lower baseline state anxiety tended to have poorer depressive symptom outcomes compared to those on placebo with higher state anxiety.

Table 3.

State anxiety by intervention group interaction, general linear model results

| HAMD | BDI-II | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-value | R2 | p-value | R2 | ||

| Age | 1 | 0.11 | 0.020 | 0.12 | 0.006 |

| Gender | 1 | 0.68 | 0.004 | 0.52 | 0.002 |

| Race | 2 | 0.57 | 0.013 | 0.04 | 0.038 |

| Pre-treatment depressiona | 1 | 0.10 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.035 |

| Pre-treatment state anxiety | 1 | 0.06 | 0.016 | 0.02 | 0.028 |

| Active treatment vs. placebo | 1 | 0.90 | 0.065 | 0.16 | 0.037 |

| All exercise vs. sertraline | 1 | 0.84 | 0.014 | 0.29 | 0.015 |

| Pre-treatment anxiety by active treatments vs. placebo interaction | 1 | 0.004 | 0.053 | 0.02 | 0.030 |

| Pre-treatment anxiety by all exercise vs. sertraline interaction | 1 | 0.11 | 0.001 | 0.07 | 0.010 |

Pre-treatment depression measure is HAMD for the HAMD outcome and BDI-II for the BDI-II outcome.

Figure 3.

Post-treatment HAMD (Panel A-Top) and BDI (Panel B-Bottom) scores by treatment group and pre-treatment levels of state anxiety, adjusted for pre-intervention anxiety, pre-intervention depression, age, gender, and race. Values represent predicted scores for a typical participant at the 25th and 75th percentile (scores of 43 and 55, respectively) of baseline state anxiety. Participants with low state anxiety in the active treatments had lower HAMD depression scores compared to those with high anxiety. The pattern was similar for BDI-II scores, but this difference was less pronounced in the sertraline condition, with both high and low anxiety showing low post-treatment scores. Error bars represent 95% confidence limits.

Probing the two significant interactions further using the Johnson-Neyman technique (Johnson & Neyman, 1936), revealed that for the HAMD outcome, the difference between the active treatments (exercise and sertraline) and the placebo condition was statistically significant (i.e., at p < .05) in the region where the baseline state anxiety score was < 40 and > 61. The Johnson-Neyman result was similar for the BDI-II outcome; the difference between the active treatments and placebo was statistically significant in the region where the baseline state anxiety score was < 47 (see Appendix A).

DISCUSSION

As reported in our primary publication, among a sample of clinically depressed, sedentary, middle-aged and older adults, 46% were fully remitted at the end of the 4-month intervention, with patients receiving exercise or sertraline achieving comparable reductions in depressive symptoms, which were greater than placebo controls (Blumenthal et al., 2007). The present report extends these findings to note that not only was depression reduced, but that those participants who received either exercise or sertraline also reported significant reductions in state anxiety compared to those receiving placebo. In addition to confirming the value of exercise in improving depression, these results also indicate that exercise is effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety. (Bartley, Hay, & Bloch, 2013; Wipfli, Rethorst, & Landers, 2008). Further, these findings suggest that exercise is comparable to sertraline, an antidepressant that is also widely used to treat anxiety.

The results of this trial are consistent with findings from a number of meta-analyses of clinical populations which have reported that exercise improves depressive symptoms among depressed individuals (Cooney et al., 2013; Krogh, Nordentoft, Sterne, & Lawlor, 2011; Lawlor & Hopker, 2001; Morres et al., 2019). The effects of exercise on anxiety disorders have been less consistent, however, with some studies reporting positive results with moderate effect sizes (Wipfli, Rethorst, & Landers, 2008) while others reporting no benefit (Bartley, Hay, & Bloch, 2013). These discrepancies could be due, in part, to the nature of the samples studied and methodologies employed. Rebar and colleagues (Rebar, Stanton, Geard, Short, Duncan, & Vandelanotte, 2015) examined 8 meta-analyses of physical activity and depression or anxiety in “non-clinical” populations including 92 studies totaling 4310 participants with depression and 306 studies totaling 10,755 participants with anxiety. In their analysis, physical activity reduced depression with a medium effect size (SMD = −0.50), but with a smaller effect size for anxiety (SMD = −0.38) and suggested that exercise may be more effective in reducing symptoms of depression compared to anxiety. Further, they suggested that effects may be less consistent for studies of clinical populations. For example, Bartley and colleagues (Bartley, Hay, & Bloch, 2013) reported that physical activity had little benefit for anxiety among those with anxiety disorders (SMD = −0.02), while Wipfli, Rethorst and Landers (2008) found a moderate effect (SMD = −0.52). In a review of 12 RCTs and 5 meta-analyses, Stonerock and colleagues (Stonerock, Hoffman, Smith, & Blumenthal, 2015) reported that the majority of studies concluded that exercise offered benefits comparable to established treatments, such as psychotropic medication or cognitive behavior therapy, and better than those of placebo or waitlist controls. However, the authors also noted that because most studies suffered from significant methodological limitations, and few studies included patients with diagnosed anxiety disorders, the value of exercise to treat anxiety remained uncertain. Moreover, no studies specifically examined the effects of exercise on anxiety among patients with clinical depression. In the SMILE-II study, all participants were diagnosed with MDD, and standard measures of depression and anxiety were obtained, albeit no formal diagnosis of a co-morbid anxiety disorder was performed.

In a systematic and comprehensive review of 63 exercise and depression trials, Bond and colleagues (Bond, Stanton, Wintour, Rosenbaum, & Rebar, 2020), noted that only two studies considered co-morbidity descriptively, and neither accounted for co-morbidity in their analyses. They noted that the absence of data on this issue represented a significant gap in our understanding of how anxiety impacts the effects of exercise on depression and that this information was critical for guiding future clinical practice. To our knowledge, this secondary analysis of data from the SMILE-II study is the first report showing that pre-treatment state anxiety modified the effects of exercise on depression.

It has been noted that depression and anxiety often co-occur in the general community as well as in primary care and psychiatric settings (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005). Indeed, in the present study, we found that 85% of our sample reported elevated symptoms of anxiety as defined as an STAI score ≥ 40. Although previous studies generally have shown that aerobic exercise is an effective short-term treatment for MDD in patient volunteers, the beneficial effects of exercise, like those of antidepressant medications and psychotherapy, may be tempered by the presence of comorbid anxiety (Dunlop et al., 2017). In the present report, participants with MDD randomized to either exercise or sertraline experienced significant reductions in depressive symptoms compared to placebo controls, but the beneficial effects of exercise were more prominent among patients reporting low comorbid anxiety, especially among the exercisers. Those patients with MDD and elevated symptoms of state anxiety who received exercise or sertraline had smaller reductions in depressive symptoms compared to those with low anxiety. These results are consistent with data from Lenze and colleagues (Lenze, Mulsant, Shear, Alexopoulos, Frank, & Reynolds, 2001) who reported that depressed patients with comorbid anxiety had poorer treatment outcomes compared to those with depression alone. In the context of other RCTs that examined the effects of exercise on depression, it would appear that the presence of significant comorbid anxiety may serve to diminish the observed benefits of exercise and antidepressants on depressive symptoms. Depressed patients who are also highly anxious may have a more complex pattern of dysregulated pathophysiology that requires a more comprehensive intervention addressing the underlying dysregulation. One practical implication of these findings is that the use of exercise as a treatment for patients with MDD with comorbid anxiety may need to be augmented by additional therapies to maximize therapeutic effectiveness. Because accumulating evidence has shown that baseline anxiety levels among MDD patients predict greater relapse following successful treatments with antidepressants and cognitive behavior therapy (Kennedy, Dunlop, Craighead, Nemeroff, Mayberg, & Craighead, 2018), it also seems likely that more specialized and tailored treatments will be needed to sustain the long-term effects of exercise on MDD recurrence.

It should be noted that this study had several limitations. The final sample was relatively small and may have lacked adequate power to detect differences between treatment groups. We only used a subset of the original sample, eliminating those who exhibited an early response or those who had missing interim anxiety assessments. Although this approach minimized the effect of “placebo-responders,” the benefit of randomization may have been diminished. Although all patients were diagnosed with MDD, they were not selected for comorbid anxiety and the presence of a comorbid anxiety disorder was not assessed. However, 85% of the sample had significant elevations on the STAI, which confirms the high degree of comorbidity of anxiety among patients with MDD. Future studies will need to evaluate the efficacy of treating individuals with diagnosed comorbid mood and anxiety disorders. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which often may co-occur with MDD, also was not assessed, and may be especially difficult to treat and require longer term therapy to be effective (Londborg et al., 2001). In addition, because the presence of anxiety disorders was not assessed, future studies also should evaluate the efficacy of exercise in individuals with diagnosed anxiety disorders without MDD. Finally, if monotherapy is judged to be of limited effectiveness for patients with MDD and comorbid anxiety, augmenting treatment with an additional medication may be warranted. Similarly, the dose of aerobic exercise may need to be adjusted by increasing the frequency, duration, or intensity or by augmenting aerobic exercise with resistance training.

In conclusion, while previous studies of exercise in non-psychiatric patient populations and in patients with diagnosed anxiety disorders have provided evidence for the beneficial effects of exercise on anxiety, the analysis of data from SMILE-II indicates that exercise reduces symptoms of anxiety in patients with MDD. The reductions in state anxiety are comparable in magnitude to those observed for patients receiving sertraline, an antidepressant that has demonstrated efficacy for reducing anxiety symptoms (Lewis et al., 2019). Furthermore, results from the present report also suggest that anxiety may modify the response to exercise in adults with MDD. Although both exercise and sertraline reduced depressive symptoms, those with higher pre-treatment state anxiety had an attenuated response to treatment, particularly among those randomized to exercise, relative to those with lower state anxiety. Because anxiety is commonly found in adults with MDD, both as a symptom and as a comorbid disorder, these findings suggest that anxiety as well as depression may need to be addressed to maximize therapeutic effectiveness.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grant MH 49679 and HL 25552 from the National Institutes of Health. Medication and matched placebo pills were provided by a grant from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, Inc. We also thank Steve Herman, Ph.D. and Patrick Smith, Ph.D, for assistance with data collection and management and Hannah Malian for her assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. We also note that no authors reported any conflicts of interest. PMD has received grants from and/or served as an advisor to pharmaceutical, health and wellness companies for other projects. He also owns stocks in several health and technology companies whose products are not discussed here. He is a co-inventor on several patents which are not discussed here.

Abbreviations:

- BDI-II

Beck Depression Inventory-II

- DSM-IV

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth edition

- GLM

general linear model

- HAMD

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

- HR

heart rate

- MDD

Major Depressive Disorder

- PTSD

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- SCID

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders

- RCT

Randomized clinical trial

- SSRI

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor

- STAI

Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

Registration: clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00331305.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Allgulander C, & Lavori PW (1993). Causes of death among 936 elderly patients with 'pure' anxiety neurosis in Stockholm County, Sweden, and in patients with depressive neurosis or both diagnoses. Comprehensive psychiatry, 34(5), 299–302. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(93)90014-u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartley CA, Hay M, & Bloch MH (2013). Meta-analysis: aerobic exercise for the treatment of anxiety disorders. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry, 45, 34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). Beck Depression Inventory Manual (Vol. 2nd ed.). San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Doraiswamy PM, Watkins L, Hoffman BM, Barbour KA, … Sherwood A (2007). Exercise and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Psychosomatic medicine, 69(7), 587–596. doi:PSY.0b013e318148c19a [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Moore KA, Craighead WE, Herman S, Khatri P, … Krishnan KR (1999). Effects of exercise training on older patients with major depression. Archives of internal medicine, 159(19), 2349–2356. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.19.2349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond G, Stanton R, Wintour S-A, Rosenbaum S, & Rebar AL (2020). Do exercise trials for adults with depression account for comorbid anxiety? A systematic review. Mental health and physical activity, 18, 100320. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2020.100320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Atkinson LZ, Ogawa Y, … Geddes JR (2018). Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet, 391(10128), 1357–1366. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, Lawlor DA, Rimer J, Waugh FR, … Mead GE (2013). Exercise for depression. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews(9), CD004366–CD004366. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coryell W, Endicott J, & Winokur G (1992). Anxiety syndromes as epiphenomena of primary major depression: outcome and familial psychopathology. The American journal of psychiatry, 149(1), 100–107. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.1.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craighead WE, & Dunlop BW (2014). Combination Psychotherapy and Antidepressant Medication Treatment for Depression: For Whom, When, and How. Annual Review of Psychology, 65(1), 267–300. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Sijbrandij M, Koole SL, Andersson G, Beekman AT, & Reynolds CF 3rd. (2014). Adding psychotherapy to antidepressant medication in depression and anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 13(1), 56–67. doi: 10.1002/wps.20089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JRT, Meoni P, Haudiquet V, Cantillon M, & Hackett D (2002). Achieving remission with venlafaxine and fluoxetine in major depression: its relationship to anxiety symptoms. Depression and Anxiety, 16(1), 4–13. doi: 10.1002/da.10045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop BW, Kelley ME, Aponte-Rivera V, Mletzko-Crowe T, Kinkead B, Ritchie JC, … Mayberg HS (2017). Effects of Patient Preferences on Outcomes in the Predictors of Remission in Depression to Individual and Combined Treatments (PReDICT) Study. Am J Psychiatry, 174(6), 546–556. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16050517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett J (1997). The detection and consequences of anxiety in clinical depression. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 58(Suppl 8), 35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. (1995). Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I), clinician version. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman JM (1996). Comorbid depression and anxiety spectrum disorders. Depression and Anxiety, 4(4), 160–168. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M (1960). A rating scale for depression. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry, 23(1), 56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Meyers JL, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Stohl M, & Grant BF (2018). Epidemiology of Adult DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder and Its Specifiers in the United States. JAMA psychiatry, 75(4), 336–346. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PO, Neyman J (1936) Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their applications to some educational problems. Statistical Research Memoirs. 1:57–93 [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Weissman MM, & Klerman GL (1990). Panic Disorder, Comorbidity, and Suicide Attempts. Archives of General Psychiatry, 47(9), 805–808. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810210013002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josefsson T, Lindwall M, & Archer T (2014). Physical exercise intervention in depressive disorders: meta-analysis and systematic review. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 24(2), 259–272. doi: 10.1111/sms.12050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy JC, Dunlop BW, Craighead LW, Nemeroff CB, Mayberg HS, & Craighead WE (2018). Follow-up of monotherapy remitters in the PReDICT study: Maintenance treatment outcomes and clinical predictors of recurrence. J Consult Clin Psychol, 86(2), 189–199. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, & Walters EE (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of general psychiatry, 62(6), 617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Liu J, Swartz M, & Blazer DG (1996). Comorbidity of DSM-III-R major depressive disorder in the general population: results from the US National Comorbidity Survey. The British Journal of Psychiatry. Supplement(30), 17–30. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8864145 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh J, Nordentoft M, Sterne JAC, & Lawlor DA (2011). The effect of exercise in clinically depressed adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 72(4), 529–538. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08r04913blu [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh J, Videbech P, Thomsen C, Gluud C, & Nordentoft M (2012). DEMO-II trial. Aerobic exercise versus stretching exercise in patients with major depression-a randomised clinical trial. PLoS One, 7(10), e48316–e48316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavie CJ, & Milani RV (2004). Prevalence of anxiety in coronary patients with improvement following cardiac rehabilitation and exercise training. American Journal of Cardiology, 93, 336–339. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor DA, & Hopker SW (2001). The effectiveness of exercise as an intervention in the management of depression: systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 322(7289), 763–767. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7289.763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze EJ, Mulsant BH, Shear MK, Alexopoulos GS, Frank E, & Reynolds CF 3rd. (2001). Comorbidity of depression and anxiety disorders in later life. Depression and Anxiety, 14(2), 86–93. doi: 10.1002/da.1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis G, Duffy L, Ades A, Amos R, Araya R, Brabyn S, … Lewis G (2019). The clinical effectiveness of sertraline in primary care and the role of depression severity and duration (PANDA): a pragmatic, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised trial. The lancet. Psychiatry, 6(11), 903–914. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30366-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Londborg PD, Hegel MT, Goldstein S, Goldstein D, Himmelhoch JM, Maddock R, Patterson WM, Rausch J, Farfel GM. (2001) Sertraline treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: results of 24 weeks of open-label continuation treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. May 62(5):325–31. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morres ID, Hatzigeorgiadis A, Stathi A, Comoutos N, Arpin-Cribbie C, Krommidas C, Theodorakis Y. Aerobic exercise for adult patients with major depressive disorder in mental health services: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2019. January;36(1):39–53. doi: 10.1002/da.22842. Epub 2018 Oct 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Fireman B, Weissman MM, Leon AC, Sheehan DV, Kathol RG, … Farber L (1997). Mental disorders and disability among patients in a primary care group practice. The American journal of psychiatry, 154(12), 1734–1740. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.12.1734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebar AL, Stanton R, Geard D, Short C, Duncan MJ, & Vandelanotte C (2015). A meta-meta-analysis of the effect of physical activity on depression and anxiety in non-clinical adult populations. Health psychology review, 9(3), 366–378. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2015.1022901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, & Ratcliff KS (1981). National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Its history, characteristics, and validity. Archives of general psychiatry, 38(4), 381–389. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Stewart JW, Warden D, … Fava M (2006). Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. The American journal of psychiatry, 163(11), 1905–1917. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulberg HC, Madonia MJ, Block MR, Coulehan JL, Scott CP, Rodriguez E, & Black A (1995). Major depression in primary care practice: clinical characteristics and treatment implications. Psychosomatics, 36(2), 129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, & Wells KB (1997). Course of depression in patients with comorbid anxiety disorders. Journal of affective disorders, 43(3), 245–250. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)01442-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CE, & Gorsuch RL (1970). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steffens DC, & McQuoid DR (2005). Impact of symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder on the course of late-life depression. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry : official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 13(1), 40–47. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.1.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stonerock GL, Hoffman BM, Smith PJ, & Blumenthal JA (2015). Exercise as Treatment for Anxiety: Systematic Review and Analysis. Ann Behav Med, 49(4), 542–556. doi: 10.1007/s12160-014-9685-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Warden D, McKinney W, Downing M, … Sackeim HA (2006). Factors associated with health-related quality of life among outpatients with major depressive disorder: a STAR*D report. J Clin Psychiatry, 67(2), 185–195. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16566612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wipfli BM, Rethorst CD, & Landers DM (2008). The anxiolytic effects of exercise: a meta-analysis of randomized trials and dose-response analysis. Journal of sport & exercise psychology, 30(4), 392–410. doi: 10.1123/jsep.30.4.392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request.