Abstract

Background

The effects of improvement (implementation and de-implementation) interventions are often modest. Although positive and negative deviance studies have been extensively used in improvement science and quality improvement efforts, conceptual and methodological innovations are needed to improve our ability to use information about variation in quality to design more effective interventions.

Objective

We describe a novel mixed methods extension of the deviance study we term “delta studies.” Delta studies seek to quantitatively identify sites that have recently changed from low performers to high performers, or vice versa, in order to qualitatively learn about active strategies that produced recent change, challenges change agents faced and how they overcame them, and where applicable, the causes of recent deterioration in performance—information intended to inform the design of improvement interventions for deployment in low performing sites. We provide examples of lessons learned from this method that may have been missed with traditional positive or negative deviance designs.

Design

Considerations for quantitatively identifying delta sites are described including which quality metrics to track, over what timeframe to observe change, how to account for reliability of observed change, consideration of patient volume and initial performance as implementation context factors, and how to define clinically meaningful change. Methods to adapt qualitative protocols by integrating quantitative information about change in performance are also presented. We provide sample data and R code that can be used to graphically display distributions of initial status, change, and volume that are essential to delta studies.

Participants

Patients and facilities of the US Veterans Health Administration.

Key Results

As an example, we discuss what decisions we made regarding the delta study design considerations in a funded study of low-value preoperative testing. The method helped us find sites that had recently reduced the burden of low-value testing, and learn about the strategies they employed and challenges they faced.

Conclusions

The delta study concept is a promising mixed methods innovation to efficiently and effectively identify improvement strategies and other factors that have actually produced change in real-world settings.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-020-06199-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: methods, deviance studies, learning from change, implementation science, healthcare evaluation mechanisms

BACKGROUND

Healthcare-focused improvement research often starts by quantitatively describing variation in healthcare quality, quantitatively and qualitatively studying the barriers and facilitators (i.e., determinants) of this variation, and then using what is learned to design and evaluate improvement (implementation or de-implementation) interventions.1 This common mixed methods design, which uses quantitative results to inform subsequent qualitative examination and ultimate synthesis of these streams, has been termed a “sequential explanatory” design.2, 3 Mistakes in this process can be made anywhere along the way. Problematic definitions of quality can focus attention on practices without a strong evidence base.4 Investigations of determinants can be conceptually or methodologically flawed, leading to incomplete or incorrect understanding of variations in quality.5 Designing improvement strategies and interventions that address the identified barriers and facilitators is also complicated and an active area of research.5–8 Therefore, it is perhaps not surprising that the effects of improvement interventions are often more modest than hoped.8–10 Conceptual and methodological innovations are needed to improve our ability to design effective improvement interventions.8 In this paper, we focus on one mixed methods innovation to efficiently and effectively identify improvement strategies and other factors that have produced change in real-world settings.

A traditional sequential explanatory approach to diagnosing the barriers and facilitators of healthcare quality is to qualitatively study those clinicians and settings that are quantitatively found to be positive or negative outliers—so-called deviance studies.11–13 The idea behind deviance studies is simple and compelling: If you want to know about the factors that facilitate success, study successful people and places.14 Conversely, barriers to success are identified through studying people and places that are not successful. Deviance studies have been used extensively in improvement science and quality improvement.13 One limitation of deviance studies is that factors thought to facilitate success in successful places may not be applicable or logistically feasible to implement in places that need to improve. Unless they have experienced recent improvements in performance, lessons derived from positive outliers may not be informative to the design of improvement interventions for negative outliers.

Here, we propose an extension of the deviance study concept we term “delta studies.” Delta studies seek to quantitatively identify sites that have recently changed from low performers to high performers, or vice versa, in order to then qualitatively learn about active strategies that produced change, challenges change agents faced and how they overcame them, and where applicable, the causes of recent deterioration in performance—information intended to inform the design of improvement interventions for deployment in low performing sites. The delta study concept and design have been successfully employed in large-scale improvement studies,15–17 but its distinctive features and methodological nuances relative to positive deviance studies14 have not been adequately described. Our initial experiences with applying the delta study concept suggest its potential for revealing information about the active improvement strategies or other factors that produced recent change in performance, rather than just information about determinants of static performance (i.e., barriers and facilitators) as might be revealed in a traditional deviance study. Before outlining the details of the method and design decisions that must be undertaken, we briefly describe lessons revealed from an in-progress delta study that likely would have been missed in traditional deviance studies.

Low-Value Preoperative Testing

In piloting this method in a VA-funded study to describe and develop strategies to reduce low-value preoperative testing for cataract surgery, we identified several sites with substantial decreases (improvements) in low-value testing between 2015 and 2017. By interviewing the service chiefs, anesthesiologists, and surgeons at these delta sites, we learned about common features that drove high levels of low-value testing before the change, and a variety of strategies (both common and unique) that explained the observed improvement. Prior to the improvements when the prevalence of low-value testing was high, most delta sites conducted evaluations for minor surgeries in the same preoperative clinic as evaluations for more major surgeries. The same battery of tests was routinely ordered for all preoperative patients regardless of procedure, planned anesthesia, or patient characteristics. We found that delta sites instituted a variety of strategies to reduce testing. Some instituted a specific pre-op clinic for minor procedures, focused on tailoring screening tests to procedure, anesthesia, or patient-specific risks. Some implemented tailoring protocols in the existing preoperative clinics. Others switched to making no evaluation the default, but still available when indicated by patient characteristics.

We were also able to learn from the people who actively produced change about challenges they faced implementing their innovations and suggestions for others wanting to make similar improvements. For example, in one site, the switch to the no-evaluation default was met with initial resistance. However, when it was presented as a short-term trial, comfort and buy-in increased. When nothing bad happened, the change became permanent. The delta study method allowed us to identify effective real-world change strategies and, in many cases, to learn directly from change agents about their successes and challenges. These opportunities would likely have been missed by studying stable high performers.

The purpose of the rest of this paper is to describe factors to consider in selecting delta sites for deeper qualitative investigation and to present possible adaptions to conceptually grounded qualitative protocols to focus on change. We describe how we wrestled with these design decisions in the low-value testing study. We also provide R code that can be used to graphically display distributions of initial status, change, and volume that are essential to using this method.

METHODS

In this section, we describe (1) quantitative methods and criteria for delta site selection and (2) considerations for using the quantitative results to inform the qualitative aspects of delta studies.

Criteria for Delta Site Selection

Several factors need to be considered in using quantitative results on change in performance in the selection of delta sites for deeper qualitative investigation. The overall goals of the study will dictate how these decisions are negotiated:

Which Quality Metrics Are Most Important to Track?

Improvement science studies are predicated on the existence of a process quality gap that needs to be fixed. However, most quality gaps have several dimensions and candidate specifications.18, 19 For example, efforts to improve the provision of evidence-supported psychotherapies for mental health disorders might hope to improve capacity (more trained clinicians), access (more patients served), length of engagement, and/or fidelity to established protocols. Some facilities might experience high improvement on all of these metrics, or some might have high delta (improvement or deterioration) for some and not others. Thinking through these scenarios and looking at the candidate metrics and distributions of change can help researchers refine the problem or problems that take priority when selecting facilities for qualitative study. Note that this consideration is also relevant for negative and positive deviance studies.

Over What Timeframe Do You Observe Change?

The main purpose of identifying sites that have experienced change is to then qualitatively learn how change happened. Choosing a baseline period needs to balance observing long enough to obtain a stable estimate of performance and recency to maximize the probability that key informants are still available and can provide relevant information. The follow-up period also needs to be long enough to obtain a stable estimate, occur long enough after the baseline period to allow for real change to happen, and be as recent as possible. Beyond the two time period pre-post formulation we have used, there may be other ways to represent change (e.g., linear slope over a time series) that could be developed for use in this context.

How to Account for the Reliability of Observed Change?

It is important not to over-interpret results that do not represent real change. Measured change is a sum of real change (signal) and measurement error (noise). For a quality metric that is calculated on a measurement year (e.g., the proportion patients with an opioid use disorder in 2017 that received medication treatment), reliability, also known as precision, quantifies the variation in scores that we would expect if the same year could be repeated many times.20 Many factors can affect reliability when measuring quality and change in quality.20–22 However, when the target quality metric is well-conceived and operationalized, perhaps the most important source of noise to consider is low volume measurement units (e.g., patients per clinic).23 A change from 50 to 75% in the percent of patients meeting a quality metric is less reliable in a clinic with 4 versus 400 patients in the denominator. For quality to be reliably measured, each observation period needs to be long enough to allow enough patients to be observed but short enough so real (vs. measured) performance does not change.

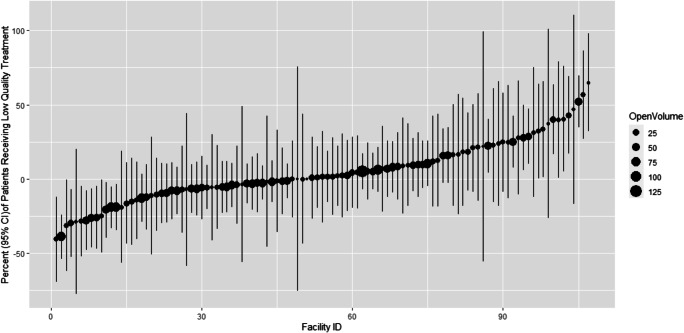

One simplistic but effective strategy to address this source of unreliability is to restrict the analysis to units with at least some minimum number of target patients over a period of time that real change is unlikely to occur. A more sophisticated way to determine if facilities are true outliers in terms of change in performance is to produce plots of 95% confidence intervals of the change in proportions (Fig. 1).22, 24, 25 Confidence intervals that do not include zero represent real change. Confidence intervals that do not overlap are significantly different from each other. The R code and data we used to produce these plots are provided as supplemental files.

Figure 1.

95% CIs of percent change in low-quality care in year 1 for 120 facilities.

Is Patient Volume an Important Aspect of Implementation Context?

Beyond the effect of site-level patient volume on reliability, one must also consider if patient volume is an important selection criterion in terms of implementation context.26, 27 Patient volume might be associated with other resources that impact implementation context. Effective implementation strategies may be quite different for small and/or rural facilities compared with very large and/or urban medical centers. Depending on the goals of the study, researchers may choose to maximize homogeneity or heterogeneity of facility size, or other related aspect of implementation context, in their qualitative selection criteria.

Initial Level of Quality

Implementation context includes current openness to and penetration of the practices to be implemented.28 Delta sites selected for qualitative study should have baseline levels of quality that match the sites targeted for improvement. If the ultimate goal is to improve quality at low outlier sites,29 then the delta studies should look for sites who were low outliers at baseline but experienced significant improvements. If the ultimate goal is to help 25th percentile sites improve to 75th percentile sites, then the delta studies should look for sites that were initially 25th percentile but experienced significant improvements.

Defining Meaningful Change

The literature on defining clinically vs. statistically meaningful change is mostly centered on patient-level outcomes30 or comparing facility-level performance between institutions.20–22 Less attention has been put on how to define clinically or operationally meaningful within-facility change. Beyond being reliable, what magnitude of change seems important to achieve? Is relative or absolute change more important for the problem at hand? Is an improvement from 25% performance to 75% performance (relative and absolute improvement 300% and 50%, respectively) more or less important than an improvement from 1 to 5% performance (relative and absolute improvement 500% and 4% respectively)? Clinically meaningful change, in relative or absolute terms, should be defined for each study and considered in selecting delta sites.

Designing Conceptually Grounded Interview Guides or Questionnaires for Delta Studies

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research,28 the Theoretical Domains Framework,31 and other frameworks have been used to develop conceptually grounded questionnaires and interview protocols to better understand the determinant current practice (aka barriers and facilitators). In traditional deviance studies, high and low performers are asked about various domains that might be related to their current status. In delta studies, it is fairly straightforward to modify these templates to focus on understanding changes in domains that influenced changes in performance (Table 1). When the change is positive, we also include specific information in recruitment materials: “We are interested in learning more about decisions regarding whether or not to order preoperative screening tests that some consider low value. In 2015, 90% of patients receiving cataract surgery at your facility received at least one low value test. But in 2017, that number was only 20%. We are interested in learning from you how that change occurred.” The exact nature of the qualitative investigation will be driven by the goals of the project. In our low-value testing study, we were interested in conducting a series of individual case studies in order to find either common or unique strategies that might account for the recent changes in performance.

Table 1.

Examples of Theoretical Domains Framework Domain-Grounded Interview Questions for Deviance and Delta Studies (Adapted from Michie et al., 2005 and Patey et al., 2012) 31,32

| Theoretical Domains Framework domain | Deviance study: example interview questions for low performing site | Delta study: example interview questions for greatly improved site |

|---|---|---|

| Motivation and goals | What would be an incentive for you to reduce the number of preoperative tests you order when evaluating patients for low-risk procedures? | Was there an incentive that helped reduce the number of preoperative tests you ordered when evaluating patients for low-risk procedures? |

| Beliefs about capabilities | How easy or difficult is it for you personally to cancel or order no tests as all? | Has it become more or less difficult for you personally to cancel or order no tests as all? (If yes) In what ways? How did this change occur? |

| Beliefs about consequences | What will happen if you do not order tests during your pre-op evaluation for low-risk patients? | Compared to before, do you think the consequences or risks have changed of not ordering tests during your pre-op evaluation for low procedures? |

| Environmental context and resources | What aspects of your clinical environment influence whether or not you are able to order preoperative tests for patient having a low-risk procedure? | What aspects of your clinical environment have changed to enable you to reduce the number of preoperative tests you order for a pre-op evaluation for patient having a low-risk procedure? |

| Social influences | Would your section chief support your decision to not order preoperative tests for low-risk procedures? | Has your section leader been supportive of your decision to not order tests for low-risk procedures? |

| Behavioral regulation | What would you personally have to do to decrease the number of preoperative tests you order for a patient having low-risk procedure? | How have you personally managed to decrease the number of preoperative tests you order for a patient having low-risk surgery? |

| Emotion | Does not ordering preoperative tests for a patient having a low-risk procedure evoke worry or concern in you? | Do you feel more or less worry or concern when you do not order preoperative tests compared to before? (If yes), what has contributed to that change? |

RESULTS

In this section, we present our experience conducting a delta study on the de-implementation of low-value preoperative testing for patients undergoing low-risk surgery in the Veterans Health Administration (VA). Although the main results from this study will be of most interest to perioperative professionals (and published in a specialty journal), how we navigated the decisions regarding the delta study design is intended to be useful to implementation scientists more broadly.

Metrics

In our study on low-value preoperative testing, several metrics of quality were relevant: the proportion of patients receiving at least one low-value test, the average number of low-value tests per patient, the average cost of low-value tests per patient, and total facility costs. Although we presumed that these metrics would be highly correlated, they were not. We found that some sites ordered many inexpensive tests while others ordered fewer very expensive tests. Although we could have chosen one of the metrics as primary and ignored the others, we decided to select sites where there was a consistent signal of change across all metrics.

Timeframe

We chose 2015 as the baseline period and the most recent fiscal year (2017) as the follow-up period. The 1-year performance period is long enough to accumulate enough surgeries per facility to produce reliable estimates and is consistent with the timeframe used for many VA quality measures. Based on pilot data demonstrating lower reliability of 1-year change compared with 2-year change, we allowed a 1-year gap. Alternatively, we could have looked for a trend in a monthly or quarterly time series.

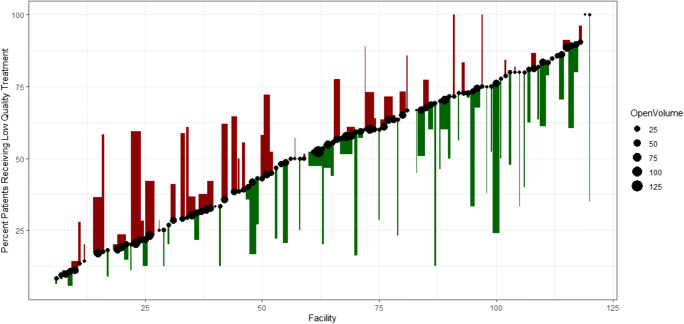

Displaying Variation in Change

A primary indicator of low quality was the proportion of patients receiving at least one low-value preoperative test in 120 VA facilities. Facilities were measured in year 1 and then again 2 years later (year 3). Modifying the candle chart concept from finance, we developed an R program to display a “delta plot” (Fig. 2): Performance in year 1 (black dots) sized by the volume of patients treated in each clinic during the measurement year with deltas between year 1 and year 3 signified by green bars for improvement and red bars for deterioration. The R code and sample data are available as supplemental files. We made similar delta charts for the other quality metrics.

Figure 2.

Distribution of initial performance (black dots), and 2-year improvements (green) and worsening (red) of low-quality care for 120 facilities.

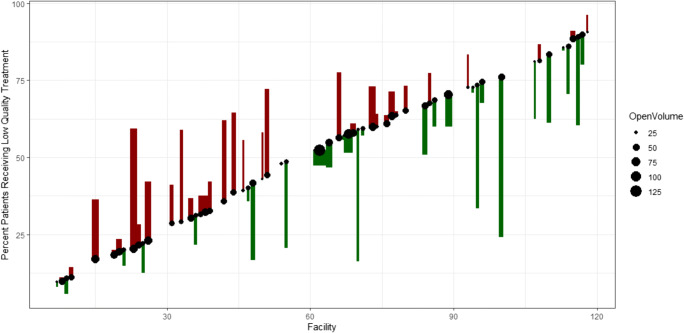

Reliability

To further improve reliability and overall impact, we restricted the sample to facilities with at least 20 low-risk surgeries a year (Fig. 3). We also checked that the 95% confidence intervals for the changes in proportion did not include (were significantly different from) zero (Fig. 1).

Figure 3.

Distribution of initial performance (black dots), and 2-year improvements (green) and worsening (red) of low-quality care for 62 facilities with > 20 denominators cases in year.

Facility Size, Initial Status, and Meaningful Change

From the sample remaining, we were most interested in larger sites with large absolute changes in quality. Although initial (2015) performance was not directly relevant from our goals, poorer performing sites had more opportunities to have large improvements. For example, in Figure 3, one can identify a moderately large site that improved from having 75 to 25% of patients receiving at least one low-value test. Although admittedly arbitrary, we prioritized sites with more than 25% absolute change in proportion of patients receiving at least one low-value test, and similar magnitude change on the other metrics.

Qualitative Interview Guide Focused on Understanding Recent Change

Informed by the Theoretical Domains Framework, the delta-focused aspects of our interview guide are included as supplemental materials. As already mentioned, we were able to use quantitative data on recent improvements to identify and recruit sites to participate in the interviews. In many cases, we recruited the people who the primary drivers of the observed change. We learned how they did it (e.g., implementing a new pre-op clinic for low-risk procedures), about the challenges they faced, and their strategies to overcome them.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, the delta study—an extension of the traditional deviance study—is described as a method to efficiently and effectively identify sites that have recently changed from low performers to high performers, or vice versa, in order to qualitatively learn about active strategies that produced change, challenges change agents faced and how they overcame them, and where applicable, the causes of recent deterioration in performance. The ultimate purpose of seeking this information is to inform the design or selection of improvement interventions for deployment in low performing sites. By sampling sites that have experienced recent improvements or deteriorations in quality for further qualitative investigation, the method seeks to identify strategies and other factors that have actually produced improvements or deteriorations in real-world settings. Delta studies are likely most feasible in large systems of care with centralized data systems. The experiences of our team and others using the delta study concept have confirmed its value (e.g., 15, 16, 17) and generated considerations in selecting delta sites for deeper qualitative investigation, adaptations to existing qualitative approaches, and R code that can be used to graphically display the facility-level distributions of initial status, change, and volume.

Although it is relatively straightforward to modify existing conceptually grounded interview guides, it is possible that conceptual frameworks and accompanying tools might be extended to accommodate factors related to change rather than current status. Identifying and learning from delta sites might also identify effective improvement strategies that should be used to supplement or improve current taxonomies33 and be modified and tested in new contexts. Our list of criteria for selecting delta sites should be considered preliminary. Furthermore, many future refinements and developments are possible. For example, the two time period pre-post formulation we have used thus far could be expanded to characterize change using other, perhaps more reliable, metrics (e.g., linear slope over a time series). Other criteria may be relevant depending on the goals of the study. For example, it may be important to select sites with good geographic or demographic diversity.

It is important to note a limitation shared by both traditional deviance studies and delta studies: they are trying to have been eloquently described but are often unheeded.34 When we ask people to explain high or recently improved performance, they will infer reasons which may or may not be the true determinants. It is therefore important not to take post hoc explanations for success at face value. Bradley et al. suggest that retrospective explanations for performance, such as those derived from deviance or delta studies, be considered hypotheses to be validated by triangulation with other methods (e.g., surveys) and data sources (e.g., a larger representative sample of organizations).14 As our group and others gain experience with conducting delta studies, its strengths, limitations, and potential for efficiently and effectively identifying improvement strategies that may have actually produced change in real-world settings will become clearer.

CONCLUSIONS

Improvement interventions designed with information about barriers and facilitators gleaned from traditional deviance studies often fail or have modest effects. Here, we describe an extension of deviance studies—delta studies—that seek to learn from recent change in performance in order to design and test improvement interventions. We view delta studies as a potentially promising complement to, rather than substitute for, traditional deviance studies. Deviance studies are helpful to understand stable high and low performers. However, if the focus is on understanding how change occurs, and finding or designing strategies to produce change, then the delta study design may be more useful. The ideas and methods outlined in this paper need to used, evaluated, and refined so that implementation scientists can most efficiently identify promising change strategies, as well as the challenges and successes experienced by change agents, all of which can inform the design of more effective improvement interventions in sites still needing to improve.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 14.6 kb)

(XLSX 13 kb)

(DOCX 21 kb)

Abbreviations

- VA

Veterans Health Administration

Authors’ Contributions

AHSH, HH, and AKF all made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the research, and provided valuable conceptual input throughout the development and the application of the method. AHSH led the drafting of the manuscript, and all authors have reviewed the draft critically and suggested revisions, given final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

Dr. Harris was funded as a VA HSR&D Research Career Scientist (RCS 14-232). Dr. Finlay was supported by a Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development (VA HSR&D) Career Development Award (CDA 13-279). The VA had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Studies used as examples are approved by the IRBs of VA Palo Alto Healthcare System and Stanford University.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position nor policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) or the US government.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol. 2015;3:32. doi: 10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6 Pt 2):2134–56. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guetterman TC, Fetters MD, Creswell JW. Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Results in Health Science Mixed Methods Research Through Joint Displays. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(6):554–61. doi: 10.1370/afm.1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris AH. The risks of action without evidence. Addiction. 2013;108(1):10–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams EC, Matson TE, Harris AHS. Strategies to increase implementation of pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorders: a structured review of care delivery and implementation interventions. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2019;14(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s13722-019-0134-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michie S, Carey RN, Johnston M, Rothman AJ, de Bruin M, Kelly MP, et al. From Theory-Inspired to Theory-Based Interventions: A Protocol for Developing and Testing a Methodology for Linking Behaviour Change Techniques to Theoretical Mechanisms of Action. Ann Behav Med. 2018;52(6):501–12. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9816-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michie S, Fixsen D, Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP. Specifying and reporting complex behaviour change interventions: the need for a scientific method. Implement Sci. 2009;4:40. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powell BJ, Fernandez ME, Williams NJ, Aarons GA, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, et al. Enhancing the Impact of Implementation Strategies in Healthcare: A Research Agenda. Front Public Health. 2019;7:3. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oxman A, Thomson M, Davis D, Haynes R. No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. CMAJ. 1995;153(10):1423–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, Oxman AD, Odgaard-Jensen J, Kristoffersen DT, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:CD000409. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000409.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baxter R, Taylor N, Kellar I, Lawton R. What methods are used to apply positive deviance within healthcare organisations? A systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(3):190–201. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ivanovic J, Anstee C, Ramsay T, Gilbert S, Maziak DE, Shamji FM, et al. Using Surgeon-Specific Outcome Reports and Positive Deviance for Continuous Quality Improvement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100(4):1188–94. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rose AJ, McCullough MB. A Practical Guide to Using the Positive Deviance Method in Health Services Research. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(3):1207–22. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Ramanadhan S, Rowe L, Nembhard IM, Krumholz HM. Research in action: using positive deviance to improve quality of health care. Implement Sci. 2009;4:25. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradley EH, Holmboe ES, Mattera JA, Roumanis SA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. A qualitative study of increasing beta-blocker use after myocardial infarction: Why do some hospitals succeed? Jama. 2001;285(20):2604–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.20.2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Webster TR, Mattera JA, Roumanis SA, Radford MJ, et al. Achieving rapid door-to-balloon times: how top hospitals improve complex clinical systems. Circulation. 2006;113(8):1079–85. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.590133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradley EH, Herrin J, Wang Y, Barton BA, Webster TR, Mattera JA, et al. Strategies for reducing the door-to-balloon time in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(22):2308–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa063117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donabedian A. An Introduction to Quality Assurance in Health Care. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris AH, Kivlahan DR, Bowe T, Finney JW, Humphreys K. Developing and validating process measures of health care quality: an application to alcohol use disorder treatment. Med Care. 2009;47(12):1244–50. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181b58882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams J, Mehrotra A, McGlynn E. Estimating Reliability and Misclassification in Physician Profiling: A Tutorial2010 09-2019. Available from: https://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR653.html. Accessed 1 June 2020.

- 21.Adams JL, Mehrotra A, Thomas JW, McGlynn EA. Physician cost profiling--reliability and risk of misclassification. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(11):1014–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0906323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shahian DM, Normand SL. What is a performance outlier? BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(2):95–9. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-003934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dimick JB, Welch HG, Birkmeyer JD. Surgical mortality as an indicator of hospital quality: the problem with small sample size. JAMA. 2004;292(7):847–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.7.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spiegelhalter DJ. Funnel plots for comparing institutional performance. Stat Med. 2005;24(8):1185–202. doi: 10.1002/sim.1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agresti A. An introduction to categorical data analysis. New York: Wiley; 1996. p. xi. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Squires JE, Graham ID, Hutchinson AM, Linklater S, Brehaut JC, Curran J, et al. Understanding context in knowledge translation: a concept analysis study protocol. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(5):1146–55. doi: 10.1111/jan.12574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfadenhauer LM, Gerhardus A, Mozygemba K, Lysdahl KB, Booth A, Hofmann B, et al. Making sense of complexity in context and implementation: the Context and Implementation of Complex Interventions (CICI) framework. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0552-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hagedorn H, Kenny M, Gordon AJ, Ackland PE, Noorbaloochi S, Yu W, et al. Advancing pharmacological treatments for opioid use disorder (ADaPT-OUD): protocol for testing a novel strategy to improve implementation of medication-assisted treatment for veterans with opioid use disorders in low-performing facilities. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2018;13(1):25. doi: 10.1186/s13722-018-0127-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Copay AG, Subach BR, Glassman SD, Polly DW, Jr, Schuler TC. Understanding the minimum clinically important difference: a review of concepts and methods. Spine J. 2007;7(5):541–6. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A, et al. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(1):26–33. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.011155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patey AM, Islam R, Francis JJ, Bryson GL, Grimshaw JM, Canada PPT. Anesthesiologists’ and surgeons’ perceptions about routine pre-operative testing in low-risk patients: application of the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) to identify factors that influence physicians’ decisions to order pre-operative tests. Implement Sci. 2012;7:52. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenzweig P. Misunderstanding the nature of company performance: The halo effect and other business delusions. Calif Manag Rev. 2007;49(4):6–20. doi: 10.2307/41166403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 14.6 kb)

(XLSX 13 kb)

(DOCX 21 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.