INTRODUCTION

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a leading cause of preventable harm among hospitalized patients. Consequently, considerable emphasis has been placed upon increasing prescription of VTE prophylaxis;1 however, prophylaxis prescription does not ensure administration.

Evidence suggests many doses of prescribed VTE prophylaxis are not administered in both academic and community hospitals.2 VTE prophylaxis non-administration has been associated with VTE.3 Since 2005, we have worked to improve VTE prophylaxis prescription using mandatory clinical decision support tools and prescriber performance feedback.4 Beginning in 2013, we have focused on interventions to improve VTE prophylaxis administration for hospitalized patients.4

The purpose of this study was to explore the relationship between prescription and non-administration of VTE prophylaxis in hospitalized patients. We hypothesized that non-administration would increase as prescription increased.

METHODS

In this retrospective study, we included all doses of prescribed pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis at The Johns Hopkins Hospital from January 1, 2006, through June 30, 2016. We collected data on prescription and administration from our electronic medication administration record system which requires documentation of the administration status of all doses. The Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board approved this study.

We calculated the monthly mean number of doses prescribed in the pre-intervention (before July 1, 2013) and post-intervention (July 1, 2013, through June 30, 2016) periods. We compared the proportion of non-administered doses in the pre- and post-intervention periods. We explored the relationship between prescribed VTE prophylaxis and non-administered doses using a Cochrane-Orcutt regression with first-order serial correlation. The regression included a break point on July 1, 2013, to assess the relationship between VTE prophylaxis medication doses prescribed and the proportion of doses not administered in the absence of interventions intended to reduce missed doses. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata/IC, version 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, 77845, USA).

RESULTS

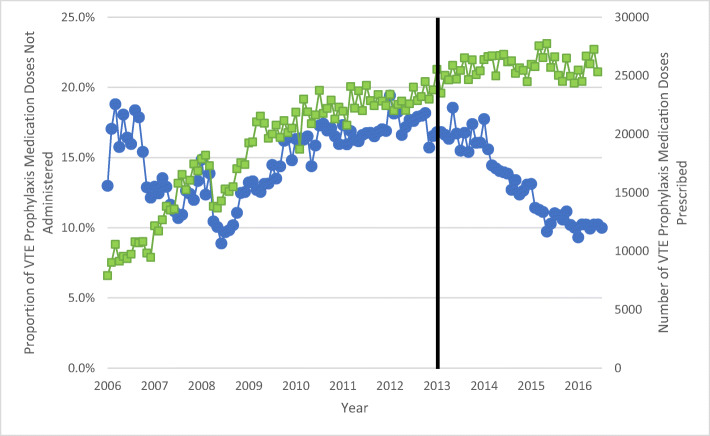

During the study period, there were 2,622,093 doses of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis prescribed. Of these, 377,269 (14.4%) were not administered. Monthly non-administration ranged from 8.9 to 19.4% (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Square dots ( ) represent the monthly number of VTE prophylaxis medications doses prescribed, and circle dots represent the monthly proportion of VTE prophylaxis medication doses not administered. The solid black line represents the beginning of the post-intervention period when an active management program to decrease missed doses on VTE prophylaxis was implemented.

) represent the monthly number of VTE prophylaxis medications doses prescribed, and circle dots represent the monthly proportion of VTE prophylaxis medication doses not administered. The solid black line represents the beginning of the post-intervention period when an active management program to decrease missed doses on VTE prophylaxis was implemented.

In the pre-intervention period, 259,165 of 1,690,655 (15.3%) prescribed doses of VTE prophylaxis were not administered. The monthly number of doses prescribed during this time increased 3-fold (range, 7,904–25,885) while the proportion of non-administered doses doubled (range, 8.9–19.4%) (Fig. 1). Non-administration increased 0.35% (95% CI, 0.16–0.53%; p < 0.001) for every additional 1000 doses prescribed during the same month for the pre-intervention period.

In the post-intervention period, 931,438 doses of VTE prophylaxis were prescribed and non-administration was significantly lower (15.3% vs. 12.7%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). The monthly mean number of doses prescribed was consistent (mean, 25,873; range, 24,355–27,737) (Fig. 1) in the post-intervention period.

DISCUSSION

As prescription of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis increases, non-administration increases. This relationship highlights an important unintended consequence of implementing interventions that target only prescription. Fortunately, this relationship can be overcome with interventions to address non-administration.

Two main reasons for non-administration of VTE prophylaxis were previously identified: gaps in nurse knowledge and variation in patient preferences.4 Nurses have reported feeling that VTE prophylaxis is overprescribed, and that they sometimes withhold VTE prophylaxis based upon a patient’s mobility status. We developed and launched learner-centric nurse education to improve knowledge about VTE and VTE prophylaxis and enhance skills in communicating this information to patients.5 Separately, we developed and implemented just-in-time patient-centered education to intervene when patients miss a dose of VTE prophylaxis.6 Both interventions were associated with significant reductions in non-administration.5,6 Missed doses of VTE prophylaxis are not inevitable; they can be reduced dramatically with active intervention.

This study is not without limitations. First, the study was done in a single academic medical center. Therefore, these findings may not be generalizable. However, non-administration of VTE prophylaxis has been reported at many other hospitals suggesting it is likely ubiquitous across the country.7 Second, our findings report an overall ecologic study of hospital performance. If non-administration varies by floor and patient population, increases may be exaggerated for some patient populations and underrepresented for others.

We found that non-administration of VTE prophylaxis increases as prescriptions increase, unless interventions targeting missed doses are employed. To replicate reductions in VTE with thromboprophylaxis demonstrated in randomized trials in real-world settings, it is essential to actively monitor and ensure appropriate administration. Future efforts to improve VTE prevention should measure both prescription and administration of VTE prophylaxis.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all members, past and present, of the Johns Hopkins Medicine Venous Thromboembolism Collaborative for their continued commitment to reducing preventable harm from VTE.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the NIH/NHLBI (R21HL129028) entitled “Analysis of the Impact of Missed Doses of Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis” and a contract (CE-12-11-4489) from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) “Preventing Venous Thromboembolism: Empowering Patients and Enabling Patient-Centered Care via Health Information Technology.”

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Mr. Lau, Dr. Streiff, and Dr. Haut are supported by a grant from the AHRQ (1R01HS024547) entitled “Individualized Performance Feedback on Venous Thromboembolism Prevention Practice” and a contract from PCORI entitled “Preventing Venous Thromboembolism (VTE): Engaging Patients to Reduce Preventable Harm from Missed/Refused Doses of VTE Prophylaxis.” Mr. Lau is supported by the Institute for Excellence in Education Berkheimer Faculty Education Scholar Grant, a contract (AD-1306-03980), and a contract from PCORI entitled “Patient Centered Approaches to Collect Sexual Orientation/Gender Identity Information in the Emergency Department.” Dr. Streiff has received research funding from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Janssen, Portola, and Roche; consulted for Bayer, CSL Behring, Daiichi-Sankyo, Janssen, and Pfizer; and has given expert witness testimony in various medical malpractice cases. Dr. Haut receives royalties from Lippincott, Williams, Wilkins for a book: “Avoiding Common ICU Errors.” Dr. Haut was the paid author of a paper commissioned by the National Academies of Medicine titled “Military Trauma Care’s Learning Health System: The Importance of Data Driven Decision Making” which was used to support the report titled “A National Trauma Care System: Integrating Military and Civilian Trauma Systems to Achieve Zero Preventable Deaths After Injury.” All other authors report no disclosures.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Brandyn D. Lau, Email: blau2@jhmi.edu.

Jiangxia Wang, Email: jwang135@jhu.edu.

Deborah B. Hobson, Email: dhobson1@jhmi.edu.

Peggy S. Kraus, Email: pkraus2@jhmi.edu.

Dauryne L. Shaffer, Email: dshaffe1@jhmi.edu.

Michael B. Streiff, Email: mstreif@jhmi.edu.

Elliott R. Haut, Email: ehaut1@jhmi.edu.

References

- 1.Lau BD, Streiff MB, Pronovost PJ, Haut ER. Venous Thromboembolism Quality Measures Fail to Accurately Measure Quality. Circulation. 2018;137(12):1278–84. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lau BD, Streiff MB, Kraus PS, et al. Missed Doses of Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) Prophylaxis at Community Hospitals: Cause for Alarm. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(1):19–20. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4203-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louis SG, Sato M, Geraci T, et al. Correlation of missed doses of enoxaparin with increased incidence of deep vein thrombosis in trauma and general surgery patients. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(4):365–70. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Streiff MB, Lau BD, Hobson DB, et al. The Johns Hopkins Venous Thromboembolism Collaborative: Multidisciplinary team approach to achieve perfect prophylaxis. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(Suppl 2):S8–S14. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lau BD, Shaffer DL, Hobson DB, et al. Effectiveness of two distinct web-based education tools for bedside nurses on medication administration practice for venous thromboembolism prevention: A randomized clinical trial. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0181664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haut ER, Aboagye JK, Shaffer DL, et al. Effect of Real-time Patient-Centered Education Bundle on Administration of Venous Thromboembolism Prevention in Hospitalized Patients. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(7):e184741. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fanikos J, Stevens LA, Labreche M, et al. Adherence to pharmacological thromboprophylaxis orders in hospitalized patients. Am J Med. 2010;123(6):536–41. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]