Abstract

Background

Primary care is increasingly contributing to improving the quality of patient care. This has imposed significant demands on clinicians with rising needs and limited resources. Organizational culture and climate have been found to be crucial in improving workforce well-being and hence quality of care. The objectives of this study are to identify organizational culture and climate measures used in primary care from 2008 to 2019 and evaluate their psychometric properties.

Methods

Data sources include PubMed, PsycINFO, HAPI, CINAHL, and Mental Measurements Yearbook. Bibliographies of relevant articles were reviewed and a cited reference search in Scopus was performed. Eligibility criteria include primary health care professionals, primary care settings, and use of measures representing the general concept of organizational culture and climate. Consensus-Based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) guidelines were followed to evaluate individual studies for methodological quality, rate results of measurement properties, qualitatively pool studies by measure, and grade evidence.

Results

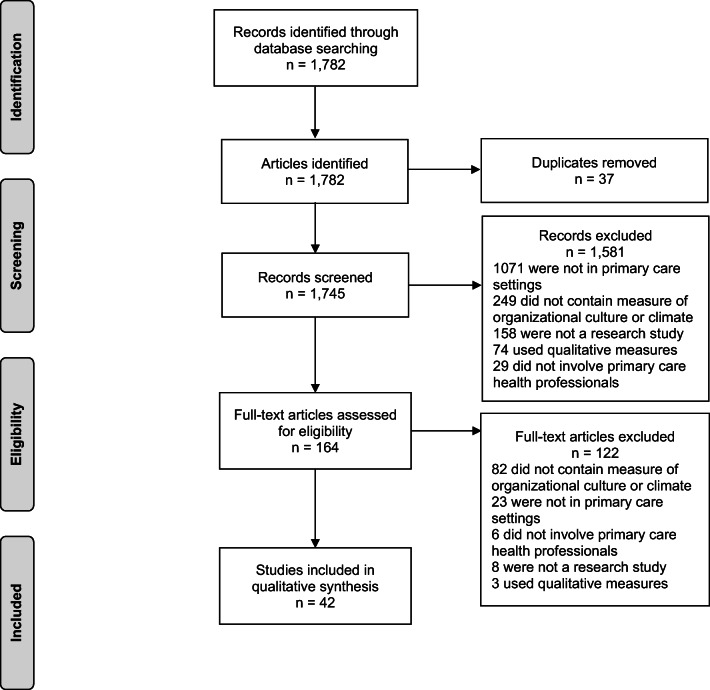

Of 1745 initial studies, 42 studies met key study inclusion criteria, with 27 measures available for review (16 for organizational culture, 11 for organizational climate). There was considerable variability in measures, both conceptually and in psychometric quality. Many reported limited or no psychometric information.

Discussion

Notable measures selected for frequent use and strength and applicability of measurement properties include the Culture Questionnaire adapted for health care settings, Practice Culture Assessment, and Medical Group Practice Culture Assessment for organizational culture. Notable climate measures include the Nurse Practitioner Primary Care Organizational Climate Questionnaire, Practice Climate Survey, and Task and Relational Climate Scale. This synthesis and appraisal of organizational culture and climate measures can help investigators make informed decisions in choosing a measure or deciding to develop a new one. In terms of limitations, ratings should be considered conservative due to adaptations of the COSMIN protocol for clinician populations.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD 42019133117

Supplementary Information

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-020-06262-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: organizational culture, organizational climate, primary care, COSMIN

INTRODUCTION

In a nation with health care system flaws and rising costs, health care reformers and political leaders are looking to primary care for solutions.1 Primary care providers are charged with improving preventative care, managing chronic diseases, and keeping patients out of hospitals, but face significant challenges, including time pressure, documentation burden, and an increasingly aging population.2–4 Organizational factors, including organizational culture and climate, are increasingly recognized as crucial to strengthening the primary care workforce and improving the quality of primary care.5–7

Organizational culture in health care is defined as the norms, values, and basic assumptions of a given organization, which drive both the quality of work life and the quality of care.8–10 Organizational climate is defined as the collective perception of the organization’s culture and how it impacts personal well-being and functioning.10 Organizational culture and climate are interconnected; an organization’s beliefs and values (culture) govern its members’ experience (climate). Together, they make up the “feel” of an organization.11,12 Unfavorable organizational cultures, such as those characterized by chaotic work environments, time pressures, and lack of control, have been associated with poorer outcomes, including greater provider burnout.2,13 Hierarchical cultures and those resistant to change have also been identified as significant barriers to innovation and implementation of evidence-based practices.14–16 In contrast, favorable cultures and climates, such as those that enhance autonomy, promote diversity and inclusion, and facilitate cooperation and collaboration, are associated with better outcomes, including provider well-being and engagement in quality improvement.17,18

Moving forward with research on organizational culture and climate in primary care requires greater attention to measurement. Although many tools to measure culture and climate have been used in health care settings, variation in measure domains and psychometric properties makes it difficult to draw consistent and reliable conclusions.10,19,20 Additionally, measures developed for other types of health care organizations, such as hospitals, may not be valid for primary care.21 Identification of validated measures for primary care will encourage more informed instrument selection in future research and foster greater understanding of the organizational culture and climate of these settings, leading to effective and sustainable ways to achieve organizational changes that improve the quality of care.

We conducted a systematic review to identify measures of organizational culture and climate used in primary care within recent years (2008–2019) and evaluate their psychometric properties. We focused on measures used with primary care practitioners who have direct patient contact, whose experience of culture and climate is likely to have the most direct influence on patient outcomes. We aimed to formulate recommendations on instrument selection based on these findings and suggest directions for future research.

METHODS

Protocol and Registration

This systematic review follows the publishing guidelines set forth by PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses),22 was assessed for quality using the AMSTAR checklist (https://amstar.ca/Amstar_Checklist.php), and contains a registered protocol with PROSPERO (CRD 42019133117). Our protocol is based on the Consensus-Based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) methodology.23–25

Eligibility Criteria

Eligibility criteria were determined a priori (Table 1). In summary, included articles met the following criteria: published 2008 and after, quantitative or mixed methodology were used, majority of the population were primary health care professionals, setting in primary care, and the target population completed an instrument measuring the general concept of organizational culture or organizational climate. Non-English articles were included; Google Translate was used to translate articles into English.26 Empirical research articles from journals and dissertations were included; cross-sectional, case-control, cohort studies, and clinical trials were also included.

Table 1.

Study Eligibility Criteria

| Study component | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Publication type |

• Empirical research articles from journals and dissertations; cross-sectional, case-control, cohort studies, clinical trials • Studies using quantitative or mixed methods |

• Articles outside of original research, including reviews, opinions, comments, editorials, conference proceedings, protocols, reports, etc. • Studies using qualitative methods only |

| Population |

• > 50% participants are primary care health professionals who have regular direct patient contact, including physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, nurses • < 50% participants are primary care health professionals, but a representative subgroup analysis has been performed on primary care health professionals |

• Personnel who do not have regular direct patient contact, including staff, administrators, managers, researchers, etc. |

| Intervention/exposure |

• Primary care settings • Medical centers, Veterans Affairs, hospitals, and health care systems ONLY if they are mentioned in the context of primary care |

• Nonprimary care settings • Medical centers, Veterans Affairs, hospitals, and health care systems with no mention of the primary care context |

| Comparator | N/A | N/A |

| Outcome |

• Use of measures representing the general concept of organizational culture or organizational climate • Organizational culture and climate are defined by the following: - “Organizational culture has been defined as the norms, values, and basic assumptions of a given organization….Organizational climate, in comparison, more closely reflects the employees’ perception of the organization’s culture; for example, it is a collective reflection of their experience of the culture.”9 |

• Measures representing specific concepts of organizational culture, including research culture, safety culture, innovation culture, etc. • Measures representing specific concepts of organizational climate, including team climate, safety climate, implementation climate, etc. |

| Time | • Studies published on or after 2008, up to the date the search is performed | • Studies published before 2008 |

Information Sources and Search Strategy

Two health sciences librarians with systematic review experience (BF, HVV) developed searches for the databases PubMed, PsycINFO, HAPI (Health and Psychosocial Instruments), CINAHL (Current Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), and Mental Measurements Yearbook. The initial PubMed search was developed (BF) using a combination of MeSH terms; title, abstract, and keywords were checked against a known set of studies. The search was then adapted to search other databases (HVV). Search strategies, dates, and results for each database were recorded in an Excel workbook and are found in ESM Appendix Table 1. The last database search was conducted on May 10, 2019.

We further manually reviewed bibliographies of articles selected for analysis and conducted a cited reference search using Scopus. Cited reference searches have been found to be a more sensitive search strategy than keyword searches for identifying articles using specific measurement instruments.27 Titles and abstracts of identified citations were initially reviewed by the first author (KSH) and selected citations underwent study selection procedures. EndNote was used to store all citations found in the search process and to check for duplicates. The last cited reference search was conducted on December 17, 2019.

Study Selection

Citations and abstracts were uploaded into DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada) for study selection. Two reviewers at any one time (KSH, JC, AG, RK) independently screened all titles and abstracts. The two reviewers met to discuss and reach consensus on differences, consulting a third reviewer (EAM) as needed. Following, two reviewers (KSH, JC) conducted independent full-text screening of included articles. Differences were discussed and consensus reached, consulting a third reviewer (EAM) as needed. Screening results using a sample of references from a preliminary search yielded a weighted average kappa value of 0.73, indicating moderate interrater reliability.28

Data Extraction

A graphic representation of the methods used to perform data extraction, risk of bias, and summary of findings is shown in Figure 1. Two reviewers (KSH, JC) independently extracted data for each study using DistillerSR with differences resolved through discussion and consultation with a third reviewer (EAM) as needed. Study-relevant characteristics extracted included sample size, sample demographics, and setting. Measure-relevant characteristics included measure name, source reference, method of administration, composition (e.g., domains, subdomains, number of items), response options, and method of scoring. Study authors were contacted via email to identify missing information.

Figure 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of the search and screening process.

Evaluation of Methodological Quality of Measurement Properties for Individual Studies

After data extraction, two independent raters trained in psychometrics (KSH, JC) used the COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist to evaluate methodological quality of measurement properties in each study.24 The COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist was originally designed for patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs); minor modifications were made for our target population of professionals (ESM Appendix Table 2). The quality of each measurement property (i.e., structural validity, internal consistency, cross-cultural validity/measurement invariance, reliability, measurement error, criterion validity, hypothesis testing for construct validity, responsiveness) was rated as very good, adequate, doubtful, inadequate, or N/A. Ratings followed the “worst score counts” principle—the lowest rating of any standard for that property was taken as its overall rating. Differences were resolved through discussion and consultation with an expert psychometrician (GES).

Rating Results of Measurement Properties of Individual Studies

Following the rating of methodological quality of measurement properties of each study, two authors (KSH, JC) rated results of measurement properties in each study using Prinsen and Terwee’s criteria for good measurement properties.24 Results were rated as sufficient (+), insufficient (−), or indeterminate (?) (i.e., not enough information available).

The Prinsen and Terwee protocol was further modified to omit ratings of content validity, which is more time- and resource-intensive than that of other measurement properties. It requires strong knowledge of PROM development and qualitative methodology, expertise in the field of interest (organizational culture and climate), and experience with the target population of interest for reviewers to rate the content of measures directly. Rating content validity to this standard was deemed beyond the scope of the study.

Data Synthesis

Following their appraisal, studies were grouped by measure, with results pooled into a qualitative summary for each measure. This summary was again rated against Prinsen and Terwee’s quality criteria for good measurement properties to obtain a measure rating. Ratings were given as sufficient (+), insufficient (−), inconsistent (±) (i.e., no explanation found for inconsistent results), or indeterminate (?). Finally, to determine the quality of the pooled result rating, the evidence was graded using a modified Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach as high, moderate, low, or very low quality. Definitions of quality levels are in ESM Appendix Table 3. The modified GRADE approach is adapted from the standard GRADE approach;29 quality of evidence is initially assumed to be high, then downgraded based on four factors: (1) risk of bias of individual studies (i.e., COSMIN ratings of methodological quality), (2) inconsistency, (3) imprecision, and (4) indirectness.24 Rating and grading were done independently by two authors (KSH, JC). Differences were resolved through discussion and consultation with a psychometrics expert (GES) as needed.

RESULTS

Study Selection

The electronic database search yielded 1782 records, 42 of which were selected for analysis. The selection process is detailed in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Data extraction, risk of bias, and summary of findings methods.

Across the 42 included studies, we identified 16 culture measures in 25 studies and 11 climate measures in 17 studies. After combining those that were variations of the same source measures (e.g., slight variations in wording or number of items; different domains or subscales), there were a total of 7 culture measures and 8 climate measures. Table 2 summarizes the measure characteristics. Measures varied in length from 15 to 50 items for organizational culture and 6 to 64 items for organizational climate. Number of domains ranged from 3 to 10 domains for culture and from 2 to 7 domains for climate. All but one measure were developed in English (Organizational Climate for Health Care Organizations,71 developed in Spanish). Most used Likert scales; however, some measures from the Competing Values Framework30 used an ipsative scale, where points are distributed among response options. Measure characteristics for individual studies can be found in ESM Appendix Table 4.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Included Measures of Organizational Culture and Organizational Climate

| Measure | Included studies | Domains (no. of items) | Response options |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational culture measures | |||

| Competing Values Framework30 | |||

| 1. Culture Questionnaire30 | Ghareeb et al., 201831 |

4 domains (16 items): 1. Organization’s character (4); 2. Organization’s managers (4); 3. Organization’s cohesion (4); 4. Organization’s emphasis (4) Items in each domain reflect 4 culture types: group, developmental, hierarchical, and rational |

Ipsative scale, where respondents distributed 100 points among 4 culture types in each domain |

| 2. Organizational Beliefs Questionnaire32 | Willcocks and Milne, 201333 | 4 domains, 10 subdomains (50 items): 1. People orientation/clan culture (work should be fun (5), worth and value of people (5), importance of shared philosophy (5)); 2. Innovation orientation/developmental culture (taking thoughtful risks (5), quality (5)); 3. Results/outcomes orientation/rational culture (being the best (5), growth, profit, and other indicators of success (5), hands-on-management (5)); 4. Control/hierarchical culture (attention to detail (5), communicating to get the job done (5)) | 5-point Likert scale, rating the extent to which participants agree with each statement about their practice |

| 3. Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument34 | Scammon et al., 201435 |

6 domains (24 items): 1. Organizational character (6); 2. Managers and leadership (6); 3. Organizational cohesion (6); 4. Management of employees (6); 5. Organizational emphases (6); 6. Criteria for success (6) Items in each domain reflect 4 culture types: group, developmental, hierarchical, and rational |

Ipsative scale, where respondents distributed 100 points among 4 culture types in each domain |

| 4. Culture Questionnaire adapted for health care settings36 |

Bosch et al., 200837 Brazil et al., 201038 Howard et al., 201139 Hung et al., 201440 Hung et al., 20165 King et al., 201841 Radwan et al., 201742 |

5 domains (20 items): 1. Practice character (4); 2. Practice managers (4); 3. Practice cohesion (4); 4. Practice emphasis (4); 5. Practice rewards (4) Items in each domain reflect 4 culture types: group, developmental, hierarchical, and rational |

Ipsative scale, where respondents distributed 100 points among 4 culture types in each domain |

| Medical Group Practice Culture Assessment43 | |||

| 5. Kralewski et al., 200844 | Kralewski et al., 200844 | 8 domains (18 items): 1. Collegiality; 2. Quality emphasis; 5. Organizational trust; 3. Participative management style; 4. Cohesiveness; 6. Adaptive; 7. Business orientation; 8. Autonomy | 4-point Likert scale, with 1 = not at all; 4 = to a great extent |

| 6. Mechaber et al., 200845 | Mechaber et al., 200845 | 5 domains (26 items): 1. Alignment between leadership and physician values (8); 2. Practice emphasis on quality (6); 3. Sense of trust or belonging (5); 4. Practice emphasis on information systems and communication; 5. Cohesiveness (3) | 4-point Likert scale, from 1 = not at all to 4 = to a great extent |

| 7. Linzer et al., 200946 | Linzer et al., 200946 | 5 domains (30 items): 1. Alignment of values between physicians and leaders (8); 2. Practice emphasis on quality (11); 3. Trust (4); 4. Information and communication (3); 5. Cohesiveness (4) | 4-point Likert scale, from 1 = not at all to 4 = to a great extent |

| 8. Dugan et al., 201147 | Dugan et al., 201147 | 3 domains (15 items): 1. Collegiality (6); 2. Quality emphasis (6); 3. Autonomy (3) | 4-point Likert scale, from 1 = not at all to 4 = to a great extent |

| 9. Pracilio et al., 201448 (Italian) | Pracilio et al., 201448 | 6 domains (16 items): 1. Collegiality (5); 2. Quality emphasis (4); 3. Organizational trust (1); 4. Information emphasis (2); 5. Management style (1); 6. cohesiveness (3) |

4-point Likert scale: 1 = do not agree at all2 = sometimes agree3 = often agree4 = agree to a great extent |

| 10. Zink et al., 201749 | Zink et al., 201749 | 10 domains: 1. Collegiality; 2. Quality emphasis; 3. Organizational trust; 4. Information emphasis; 5. Management style; 6. Cohesiveness; 7. Adaptive; 8. Business orientation; 9. Work ethic; 10. Group practice integration | 5-point Likert scale, with 5 being highest |

| 11. Linzer et al., 201950 |

Linzer et al., 201950 Prasad et al., 201951 |

5 domains (31 items): 1. Values alignment between clinicians and their leaders (8); 2. Emphasis on quality vs productivity (10); 3. Trust (5); 4. Emphasis on communication and information (4); 5. Cohesiveness (4) | 4-point Likert scale, from 1 = not at all to 4 = to a great extent |

| 12. Organizational Culture Profile, revised52 (Greek-Cypriot) | Zachariadou et al., 201353 | 7 domains (28 items): 1. Supportiveness (4); 2. Innovation (4); 3. Competitiveness (4); 4. Performance orientation (4); 5. Stability (4); 6. Emphasis on rewards (4); 7. Social responsibility (4) |

5-point Likert scale: 1 = very much 2 = considerably 3 = moderately 4 = minimally 5 = not at all |

| 13. Culture construct, Organizational Social Context54* | Kramer et al., 201755 | 3 domains, 6 subdomains (42 items): 1. Rigidity (centralization (7), formalization (7)); 2. Proficiency (responsiveness (7), competence (8)); 3. Resistant (apathy (6), suppression (7)) | 5-point Likert scale, ranging from not at all to a very great extent |

| 14. Practice Culture Assessment56 |

Dickinson et al., 201456 Dickinson et al., 201557 Jortberg et al., 201958 |

3 domains (22 items): 1. Change culture (10); 2. Work culture (8); 3. Chaos (4) | 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree |

| Primary Care Organizational Questionnaire59 | |||

| 15. Hall et al., 201060 | Hall et al., 201060 | 8 domains (40 items): 1. Conflict resolution (8); 2. Perceived effectiveness (7); 3. Communication between clinicians and staff (5); 4. Communication among clinicians (5); 5. Physician leadership (6); 6. Decision authority (3); 7. Communication timeliness (4); 8. Psychological job demands (2) |

5-point Likert scale: Conflict resolution: 1 = not at all likely; 5 = almost certain Perceived effectiveness, communication between clinicians and staff, communication among clinicians, physician leadership, communication timeliness: 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree Decision authority, psychological job demands: 1 = never; 5 = always |

| 16. Adaptive reserve domain, TransforMed Clinician and Staff Questionnaire61 | Friedberg et al., 201762 | 6 domains (23 items): 1. Relationship infrastructure (10); 2. Facilitative leadership (4); 3. Sensemaking (2); 4. Teamwork (2); 5. Work environment (2); 6. Culture of learning (3) |

6-point Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree2 = disagree3 = neither agree nor disagree4 = agree5 = strongly agree6 = does not apply or don’t know |

| Organizational climate measures | |||

| Nurse Practitioner Primary Care Organizational Climate Questionnaire63 | |||

| 17. Pilot-tested version63,b |

Poghosyan et al., 201363 Poghosyan L and Aiken LH, 201564 Poghosyan L, Shang J, and Liu J, 201565 |

5 domains (34 items): 1. NP-physician relations (8); 2. Organizational support and resources (5); 3. Autonomy and independent practice (6); 4. NP-administration relations (8); 5. Professional visibility (7) |

4-point Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree 2 = disagree 3 = agree 4 = strongly agree |

| 18. Field-tested version63,b |

Poghosyan et al., 201363 Poghosyan L, Chaplin WF, et al., 201766 Poghosyan L, Liu J, and Norful AA, 201767 Poghosyan L, Liu J, Shang J, et al., 201768 Poghosyan et al., 201869 |

4 domains (29 items): 1. NP-physician relations (7); 2. Independent practice and support (9); 3. Professional visibility (4); 4. NP-administration relations (9) |

4-point Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree 2 = disagree 3 = agree 4 = strongly agree |

| 19. IRT model70 | Poghosyan et al., 201970 | 4 domains (24 items): 1. NP-physician relations (5); 2. Professional visibility (3); 3. NP-administration relations (8); 4. Independent practice and support (8) |

4-point Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree2 = disagree3 = agree4 = strongly agree |

| 20. Organizational Climate for Health Care Organizations71 (Spanish) | Cruvinel et al., 201372 | 7 domains (64 items): 1. Leadership; 2. Professional development; 3. Relationship and team spirit; 4. Relationship with the community; 5. Safety; 6. Strategy; 7. Remuneration | 5-point Likert scale, from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree |

| 21. Climate construct, Organizational Social Context54 | Kramer et al., 201755* | 3 domains, 8 subdomains (46 items): 1. Engaged (personalization (5), personal accomplishment (6)); 2. Functional (growth and development (5), role clarity (6), cooperation (4)); 3. Stressful (emotional exhaustion (6), role overload (7), role conflict (7)) | 5-point Likert scale, ranging from not at all to a very great extent |

| 22. Kolko et al., 201473 | Kolko et al., 201473 | 2 domains, 4 subdomains (26 items): 1. “Positive” (cooperation (6), personal accomplishment (6)); 2. “Negative” (role conflict (7), role overload (7)) | 5-point Likert scale, from 0 = not at all to 4 = to a very great extent |

| 23. Practice Climate Survey74 | Grace et al., 201674 | 5 domains (26 items): 1) Team structure (5); 2) Team functioning (5); 3) Readiness for change (6); 4) Skills and knowledge (3); 5) Leadership (7) | 5-point Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree |

| 24. Primary Care Practice Climate75 | Rodriguez et al., 201575 | 2 domains, 4 subdomains (17 items): 1. Team composition and characteristics (practice decision-making (4), practice communication (5)); 2. Organizational context (psychological safety (4), leadership facilitation (4)) |

5-point Likert scale: Domain 1: 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree Domain 2: 1 = highly inaccurate to 5 = highly accurate |

| 25. Summary Practice Climate Scale76 | Becker and Roblin, 200876 | 8 domains (21 items): 1. Medical record availability (1); 2. Time for tasks (4); 3. Delegation and collaboration among team members (4); 4. Skip pattern (2); 5. Patient focus (2); 6. Collaboration and continuity of care (2); 7. Team ownership (1); 8. General autonomy (5) |

Likert scales with 4, 5, or 7 response options: 1), 2), 3), 4), 5), 7): very dissatisfied to very satisfied 6): none to max |

| 26. Task and Relational Climate Scale7 | Benzer et al., 20117 | 2 domains (6 items): 1. Task climate (3); 2. Relational climate (3) | 5-point Likert scale |

| 27. Workplace Climate Survey77 |

Friedberg et al., 201677 Martsolf et al., 201878 |

3 domains, 4 subdomains (44 items): 1. Clinic workload (6); 2. Teamwork (8); 3. Clinic functionality (staff relationships (7), QI orientation (12), manager readiness for change (7), staff readiness for change (4)) | 5-point Likert scale, with 43 of the items ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree; the remaining item assessed clinic atmosphere and ranged from 1 = calm to 5 = hectic/chaotic |

NP, nurse practitioner

*This reference is repeated twice as it includes both a culture and climate construct

Summary of Evidence

Table 3 shows the pooled qualitative summaries of measurement properties, their ratings, and an assigned GRADE for each measure. For ratings of methodological quality and results of measurement properties of individual studies, see ESM Appendix Table 5. Breakdown of GRADE assignments can be found in ESM Appendix Table 6. Overall, the most frequently reported measurement property was internal consistency, followed by structural validity. Cross-cultural validity was evaluated for two measures: the Medical Group Practice Culture Assessment (MGPCA)43 was translated into and adapted for the Italian language,48 and the revised Organizational Culture Profile52 was adapted for the Greek-Cypriot dialect.53 No psychometric properties were reported for seven culture measures and one climate measure. We describe measures that were cited by three or more studies, reported results for three or more measurement properties, have more than one measurement property with high-quality evidence, or were found to be originally developed for prim ary care (discovered through author correspondence or mentioned in the study).

Table 3.

Qualitative Summaries, Ratings, and GRADE for Measurement Properties Pooled by Measure

| Measure name | Measurement property* | Qualitative summary | Overall rating†‡ | GRADE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational culture measures | ||||

| Competing Values Framework71 | ||||

| Culture Questionnaire71 (1 study) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Organizational Beliefs Questionnaire43 (1 study) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument52 (1 study) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Culture Questionnaire adapted for health care settings36 (7 studies) | Content validity | 10 experts rated relevance of items using the CVI. All items were rated as relevant, with CVI > 0.93. Questionnaire was piloted among 30 eligible participants with modifications made based on feedback. | Not evaluated | |

| Internal consistency | Practitioners only: range (0.46, 0.89), total n = 944 Practitioners and staff: range (0.73, 0.81), total n = 593 | Practitioners only: − Practitioners and staff: ? | Practitioners only: high Practitioners and staff: moderate | |

| Medical Group Practice Culture Assessment79 (Kralewski et al., 2005) | ||||

| Kralewski et al., 200876 (1 study) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Mechaber et al., 200831 (1 study) | Internal consistency | Range (0.66, 0.88), total n = 422 | − | High |

| Linzer et al., 200932 (1 study) | Internal consistency | Range (0.66, 0.86), total n = 422 | − | High |

| Dugan et al., 201133 (1 study) | Structural validity | EFA (n = 293) was conducted with varimax rotation, yielding a 3-factor model. | − | Low |

| Pracilio, 201434 (Italian) (1 study) | Cross-cultural validity | Experts and study investigators revised the scale for the Italian health care system. 3 domains were dropped, and the scale was translated and back-translated independently 3 times. The tool was piloted among 5 clinical and policy decision makers and modified based on feedback. | ? | Very low |

| Zink et al., 201735 (1 study) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Linzer et al., 201937 (2 studies) | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Organizational Culture Profile, revised39 (Greek-Cypriot) (1 study) | Structural validity | EFA was conducted with varimax rotation; factor loading cutoff of 0.5 yielded 6-domain model. A 7-domain model was chosen due to high internal consistency and test–retest reliability. | − | Very low |

| Internal consistency | Range (0.53, 0.78), total n = 223 | − | High | |

| Reliability | Test–retest reliability was performed over a 2-week period among a pilot group of 30 nurses and physicians at a hospital. Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.78. | + | Very low | |

| Cross-cultural validity | A pretest was performed among 20 employees of a general hospital among the Greek-Cypriot population; items were rephrased based on feedback. A pilot study assessing test–retest reliability and internal consistency was then performed among 30 nurses and physicians in the hospital. | ? | Very low | |

| Climate construct, Organizational Social Context54§ (1 study) | Internal consistency | Range (0.61, 0.94), total n = 497 | − | Moderate |

| Practice Culture Assessment56 (3 studies) | Structural validity | EFA (n = 379) was conducted with oblique rotation, giving a 3-factor model | − | Low |

| Internal consistency | Range (0.78, 0.91), total n = 379 | + | Moderate | |

| Primary Care Organizational Questionnaire47 | ||||

| Hall et al., 201060 (1 study) | Internal consistency | Range (0.67, 0.94), total n = 130 | − | High |

| Adaptive reserve domain, TransforMed Clinician and Staff Questionnaire61 (1 study) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Organizational climate measures | ||||

| Nurse Practitioner Primary Care Organizational Climate Questionnaire54 | ||||

| Pilot-tested version63 (3 studies) | Content validity | See qualitative summary for field-tested version | Not evaluated | |

| Internal consistency | Range (0.80, 0.93), total n = 81 | ? | Moderate | |

| Field-tested version63 (5 studies) | Content validity | Two meetings were held; the first consisted of 3 experts who were asked to assess each item on relevance, representation, specificity, and clarity on a 4-point scale, and to give their suggestions. In the second meeting, 7 experts met for relevance and comprehensiveness; item-CVI and scale-CVI were computed, with 6/7 experts rating 41/55 items as relevant (I-CVIs 0.86–1.00). For 10 items, minor revisions were made according to expert feedback. Three questions did not receive high ranking from the experts because of clarity in language and were reworded substantially. None of the experts identified any additional content to be added (S-CVI 0.90). | Not evaluated | |

| Structural validity | EFA (n = 278) was conducted with Geomin rotation, giving a 4-factor model with RMSEA = 0.06 and CFI = 0.94. CFA (n = 314) supported a 4-factor model, with RMSEA = 0.08, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96. A 5-factor model improved model indices slightly; however, one subscale did not meet their standard acceptable criterion of at least four indicators for each latent construct, and two factors were excessively correlated. | + | High | |

| Internal consistency | Range (0.87, 0.95), total n = 314 | + | High | |

| Criterion validity | Linear and logistic regression showed scale-predicted NP job satisfaction and plans to leave current position, p < 0.001 and p = 0.011, respectively. | ? | Low | |

| IRT model70 (1 study) | Structural validity | An IRT model showed no violation of unidimensionality, local independence, and monotonicity. Model was fit to Samejima’s graded response model (Samejima 1969). No model fit indices were reported. | ? | High |

| Cross-cultural validity/measurement invariance | Significant baseline differences between NPs in New York and those in Massachusetts (e.g., age, gender, highest nursing degree, years in current position, average hours worked per week, main practice site, practice location). Nonuniform DIF found in 5 items, which were subsequently removed. | − | Very low | |

| Organizational Climate for Health Care Organizations65 (Spanish) (1 study) | Internal consistency | Range (0.77, 0.93), total n = 149 | + | High |

| Climate construct, Organizational Social Context54§ (1 study) | Internal consistency | Range (0.61, 0.94), total n = 497 | − | Moderate |

| Kolko et al., 201473 (1 study) | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Practice Climate Survey74 (1 study) | Structural validity | EFA was conducted with promax (oblique) and varimax (orthogonal) rotations. CFA yielded a 5-domain model. | ? | Low |

| Internal consistency | Range (0.76, 0.94), total n = 542 | + | High | |

| Primary Care Practice Climate75 (1 study) | Internal consistency | Range (0.83, 0.91), total n = 418 | ? | High |

| Summary Practice Climate Scale76 (1 study) | Internal consistency | Range (0.66, 0.85), total n = 97 | − | Very low |

| Task and Relational Climate Scale7 (1 study) | Structural validity | 2-level CFA (n = 223 clinics, at least 5 individuals per clinic): CFI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.03; SRMR (within) = 0.03; SRMR (between) = 0.03 | + | High |

| Internal consistency |

Individuals: range (0.86, 0.87), total n > 1115 Clinic: range (0.93, 0.94), total n = 223 |

+ | High | |

|

Workplace Climate Survey72 (2 studies) |

Structural validity | EFA (n = 401) was conducted with Geomin (oblique) rotation in Mplus; CFA (n = 200): CFI = 0.943, TLI = 0.939, RMSEA = 0.045 | + | Very low |

| Internal consistency | Range (0.72, 0.96), total n = 1047 | ? | Moderate | |

CVI, content validity index; EFA, exploratory factor analysis; CFA, confirmatory factor analysis; CFI, comparative fit index; TLI, Tucker–Lewis index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; IRT, item response theory; CTT, classical test theory; SRMR, standardized root mean residuals

*Internal consistency was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha for all studies

†+ = sufficient; − = insufficient; ± = inconsistent; ? = indeterminate

‡Rating content validity is outside the scope of the study

§This reference is repeated twice as it includes both a culture and climate construct

Organizational Culture Measures

We summarize the findings for 3 of the 16 identified culture measures: Culture Questionnaire adapted for health care settings, Practice Culture Assessment, and revised Organizational Culture Profile. The most frequently used measure, the Culture Questionnaire adapted for health care settings,36 had insufficient internal consistency based on high-quality evidence. The Practice Culture Assessment, used by three studies, had insufficient structural validity based on low-quality evidence and sufficient internal consistency based on moderate-quality evidence. Reasons for low/moderate-quality evidence were indirectness of evidence due to the population being a mix of clinicians and staff and the risk of bias from a lack of very good-quality studies. The revised Organizational Culture Profile53 reported many measurement properties, albeit the majority having very low-quality of evidence due to lack of available studies of very good quality. Downgrading also occurred due to risk of bias—structural validity was performed with a small sample size, and cross-cultural validity testing lacked direct comparisons between two culturally different groups. Among all culture measures, the Practice Culture Assessment56 is the only measure that was found to be originally developed in primary care health professionals and used in its original form. The MGPCA and the Primary Care Organizational Questionnaire59 were also developed in primary care; however, the included studies use modified forms from the original measure.

Organizational Climate Measures

We summarize findings for 4 of the 11 identified climate measures: Nurse Practitioner Primary Care Organizational Culture Questionnaire (NP-PCOCQ), Task and Relational Climate Scale, Practice Climate Survey, and Workplace Climate Survey. The climate measure used by most studies, all of which were by the measure developer, was the field-tested version of the NP-PCOCQ.63 It also had the most reported measurement properties, with high-quality evidence for sufficient structural validity and internal consistency. The Task and Relational Climate Scale,7 derived from a larger survey administered by the Veterans Affairs, also had high-quality evidence for sufficient structural validity and internal consistency, although based on a single study. The NP-PCOCQ,63 Workplace Climate Survey,77 and Practice Climate Survey74 were found to be developed in primary care settings—NP-PCOCQ with NPs and Practice Climate Survey and Workplace Climate Survey with primary care providers and staff. The Practice Climate Survey had high-quality evidence for sufficient internal consistency, while the Workplace Climate Survey had no measurement properties of high-quality evidence.

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review, we identified and evaluated the psychometric properties of instruments used from 2008 to 2019 to measure organizational culture and organizational climate for primary health care professionals in primary care settings. Overall, we found considerable variability in measures, both conceptually, in that they differ in the domains and subdomains assessed and in psychometric quality. Only a handful of measures (6 of 27) were used in more than one study, and many studies reported limited or no psychometric information. Accordingly, we were unable to pool many psychometric results.

One explanation for the variability of measures is the lack of a consensus on what domains define these two constructs.9,20,80 Generally, the domains of management, relationship infrastructure, and trust seemed to appear in several culture measures, and leadership, teamwork, and autonomy in climate measures. Thus, while evaluating content validity against a “gold standard” remained outside of our review scope, this work serves as a reference point to better understand the breadth of available domain conceptualizations. Until such standards are developed, we suggest that when choosing an organizational culture or climate measure, in addition to considering the quality of evidence, one should consider if its domains are suitable for one’s study purpose.

Lacking robust high-quality evidence, we cannot confidently recommend any one measure for use in measuring organizational culture or climate in primary care. We highlight below some of the most promising measures based on the evidence available so far. In choosing these measures, we consider its frequency of use, evidence for robust measurement properties, and if it was originally developed in primary care.

Recommendations: Organizational Culture

The Culture Questionnaire adapted for health care settings36 is the most frequently used measure of organizational culture in this review. It uses an ipsative scale design, where the respondent distributes 100 points among four items, each representing a culture type. With ipsative scales, the items are interdependent, which may confound validity and reliability (e.g., internal consistency, factor analysis). However, this design allows culture to be interpreted as a composition of multiple cultures to varying degrees, which may better represent true culture. Additionally, its widespread use makes it easily comparable across studies.

The Practice Culture Assessment56 is a newer scale originally developed in primary care settings. Testing the measurement properties of this measure for clinicians separately from staff who do not provide patient care can increase the quality of evidence for its psychometric properties.

The MGPCA43 is worth considering as it is a frequently cited source measure by several of our included studies and was also developed for primary care.43 Because each of the included studies used modified versions of the MGPCA that all lack strong validity evidence, clear recommendations cannot be made about which specific version to use. The developers recommend their most up-to-date version, a 17-item measure with eight domains (not included in this review). Testing psychometric properties of this scale and its modified versions is warranted for future use.

Recommendations: Organizational Climate

Among organizational climate measures, the field-tested version of the NP-PCOCQ63 for nurse practitioners has the strongest psychometric evidence, with high-quality evidence for sufficient structural validity and internal consistency. Further strengthening of this tool necessitates validation by investigators independent of the scale developers.

The Practice Climate Survey 74 and the Task and Relational Climate Scale7 are more recently developed measures that have been developed in primary care. Additionally, they have at least one good measurement property based on strong evidence, although this is based on a single study for each. These measures would benefit from additional use and validation.

We caution users who may be applying these measures to their own work that, when aggregating individual results to the organizational level using means (as many of our included studies had done), variability is overlooked, resulting in information loss and bias.79 Thus, aggregated results should be interpreted accordingly.

Limitations

While COSMIN guidelines provide a strong framework for systematic evaluation of measures, there were two areas where adaptations to these guidelines were necessary in the current review. First, as COSMIN guidelines are tailored to patient-reported outcome measure evaluation, we adapted the scope for relevance to a target population of health care professionals (ESM Appendix Table 2). Second, evaluation of content validity was omitted, as there was insufficient consensus in the literature to provide a gold standard for evaluating conceptual domain scope. Consequently, the ratings assigned in this review should be considered conservative.

At a review level, we recognize that all studies may not have published all methods and results of the measurement properties for the measures they used. This could negatively impact the ratings of methodological quality that were assigned to them and, subsequently, our final recommendations. To mitigate this limitation, we attempted to contact authors by email to fill in missing information when possible.

Future Directions

Based on our review of organizational culture and climate measures, we offer suggestions to build upon this work. Foremost, investigators should consider drawing on or expanding upon existing tools, before developing new competing tools in this milieu. Further validation is particularly warranted when adapting existing tools to other diverse settings or populations within primary care, expanding into new subdomains, creating short forms from already validated measures, or recalibrating scoring procedures.

Additionally, clinicians should be examined separately from nonclinical staff when measuring organizational culture or climate. For the Culture Questionnaire adapted for health care settings, pooled internal consistency results improved markedly when practitioners only were examined, compared to when practitioners and staff were examined together (Table 3). The study of Becker et al.76 illustrates how clinicians and staff were given separate, structurally different versions of a climate instrument.

The field of organizational culture and climate is one that is constantly conceptually expanding,10 with no consensus by which these constructs should be measured.20 The dynamic nature of this field presents as a limitation to its objective measurement, as demonstrated in our review. The question remains on what the best way is to objectively measure organizational culture and climate. It may require a completely new measure with a more inclusive conceptual framework, or multiple measures to capture the diversity of the concept. To work toward filling these research gaps, one research team has proposed key dimensions to comprise organizational culture in primary care.6 Future work may build upon or confirm similar work and move toward designing standards for these constructs in primary care.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we present a systematic review on instruments that measure organizational culture and climate in primary care settings. A variety of measures were found with diverse and nonuniform dimensions. Overall, more high-quality evidence on their measurement properties in primary care is needed. The lack of a standard framework for culture and climate could be contributing to the difficulty in performing rigorous validity testing. Suggestions for further research include better measurement and reporting of the psychometric properties of existing instruments, exploring differences in culture and climate between practitioners and support staff, and supporting work toward standardizing dimensions for these constructs. We hope that compiling organizational culture and climate measures in a single review can help researchers make more informed decisions when choosing a measure or when deciding to develop a new one.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 68 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Ashlynd Gogas, BS, and Rachel Kaffey, BS, for their diligent, efficient, and excellent contribution to the screening of titles and abstracts of records from our search.

Funding

This study was funded by the Clinical Scientist Training Program, sponsored by the Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, and the Roth Fellow Award for medical student research projects in psychiatry, behavioral medicine, and basic and applied research of the brain and its functioning.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bates DW. Primary care and the US health care system: what needs to change? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(10):998–999. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1464-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim LY, Rose DE, Soban LM, Stockdale SE, Meredith LS, Edwards ST, et al. Primary care tasks associated with provider burnout: findings from a veterans health administration survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;33(1):50–56. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4188-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gardner RL, Cooper E, Haskell J, Harris DA, Poplau S, Kroth PJ, et al. Physician stress and burnout: the impact of health information technology. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;26(2):106–114. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dall TM, Gallo PD, Chakrabarti R, West T, Semilla AP, Storm MV. An aging population and growing disease burden will require a large and specialized health care workforce by 2025. Health Aff. 2013;32(11):2013–2020. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hung D, Chung S, Martinez M, Tai-Seale M. Effect of organizational culture on patient access, care continuity, and experience of primary care. J Ambul Care Manag. 2016;39(3):242–252. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant S, Guthrie B, Entwistle V, Williams B. A meta-ethnography of organisational culture in primary care medical practice. J Health Organ Manag. 2014;28(1):21–40. doi: 10.1108/JHOM-07-2012-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benzer JK, Young G, Stolzmann K, Osatuke K, Meterko M, Caso A, et al. The relationship between organizational climate and quality of chronic disease management. Health Serv Res. 2011;46(3):691–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooke RA, Rousseau DM. Behavioral norms and expectations: a quantitative approach to the assessment of organizational culture. Group Organ Stud. 1988;13(3):245. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gershon RR, Stone PW, Bakken S, Larson E. Measurement of organizational culture and climate in healthcare. J Nurs Adm. 2004;34(1):33–40. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200401000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verbeke W. Exploring the conceptual expansion within the field of organizational behaviour: organizational climate and organizational culture. J Manag Stud. 1998;35(3):303–329. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider B, Brief AP, Guzzo RA. Creating a climate and culture for sustainable organizational change. Organ Dyn. 1996;24(4):7–19. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glisson C, James LR. The cross-level effects of culture and climate in human service teams. J Organ Behav. 2002;23(6):767–794. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabatin J, Williams E, Manwell LB, Schwartz MD, Brown RL, Linzer M. Predictors and outcomes of burnout in primary care physicians. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(1):41–43. doi: 10.1177/2150131915607799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nembhard IM, Alexander JA, Hoff TJ, Ramanujam R. Why does the quality of health care continue to lag? Insights from management research. Acad Manag Perspect. 2009;23(1):24–42. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams B, Perillo S, Brown T. What are the factors of organisational culture in health care settings that act as barriers to the implementation of evidence-based practice? A scoping review. Nurse Educ Today. 2015;35(2):e34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tabriz AA, Birken SA, Shea CM, Fried BJ, Viccellio P. What is full capacity protocol, and how is it implemented successfully? Implement Sci. 2019;14(73):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0925-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olson K, Marchalik D, Farley H, Dean SM, Lawrence EC, Hamidi MS, et al. Organizational strategies to reduce physician burnout and improve professional fulfillment. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2019;49. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Smith CD, Balatbat C, Corbridge S, Dopp AL, Fried J, Harter R, et al. Implementing optimal team-based care to reduce clinician burnout. NAM Perspectives [discussion paper]. 2018; https://nam.edu/implementing-optimal-team-based-care-to-reduce-clinician-burnout. Accessed 25 February 2020.

- 19.Bronkhorst BAC, Tummers LG, Steijn AJ, Vijverberg D. Organizational climate and employee mental health outcomes - a systematic review of studies in health care organizations. Health Care Manag Rev. 2015;40(3):254–271. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott T, Mannion R, Davies H, Marshall M. The quantitative measurement of organizational culture in health care: a review of the available instruments. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(3):923–945. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tallia AF, Stange KC, Reuben R, McDaniel J, Aita VA, Miller WL, Crabtree BF. Understanding organizational designs of primary care practices. J Healthc Manag. 2003;48(1):45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D, Group TP. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Mokkink LB, Vet HCWD, Prinsen CAC, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Bouter LM, et al. COSMIN risk of bias checklist for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:1171–1179. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1765-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prinsen CAC, Mokkink LB, Bouter LM, Alonso J, Patrick DL, HCWd V, et al. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:1147–1157. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-1798-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terwee CB, Prinsen CAC, Chariatto A, Westerman MJ, Patrick DL, Alonso J, et al. COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: a Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:1159–1170. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-1829-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackson JL, Kuriyama A, Anton A, Choi A, Fournier JP, Geier AK, et al. The accuracy of Google Translate for abstracting data from non-English-language trials for systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(9):677–679. doi: 10.7326/M19-0891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linder SK, Kamath GR, Pratt GF, Saraykar SS, Volk RJ. Citation searches are more sensitive than keyword searches to identify studies using specific measurement instruments. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:412–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2012;22(3):276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.GRADE. Handbook for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations using the GRADE approach. In: Schunemann H, Brozek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A, eds. GRADE Handbook. 2013: https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html. Accessed 15 May, 2020.

- 30.Quinn RE, Kimberly JR. Paradox, planning, and perseverance: guidelines for managerial practice. In: Kimberly JR, Quinn RE, editors. Managing Organization Transitions. Homewood: Dow Jones-Irwin; 1984. pp. 295–313. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghareeb A, Said H, El Zoghbi M. Examining the impact of accreditation on a primary healthcare organization in Qatar. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):216. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1321-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sashkin M. Pillars of Excellence: Organisational Beliefs Questionnaire. Carmarthen: Bryn Mawr; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Willcocks SG, Milne P. The Medical Leadership Competency Framework: challenges raised for GP educators by a pilot study of culture in general practice. Educ Prim Care. 2013;24(1):29–33. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2013.11493452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cameron K, Quinn R. Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture: Based on the Competing Values Framework. Reading: Addison-Wesley; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scammon DL, Tabler J, Brunisholz K, Gren LH, Kim J, Tomoaia-Cotisel A, et al. Organizational culture associated with provider satisfaction. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27(2):219–228. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2014.02.120338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shortell SM, Jones RH, Rademaker AW, Gillies RR, Dranove DS, Hughes EFX, et al. Assessing the impact of total quality management and organizational culture on multiple outcomes of care for coronary artery bypass graft surgery patients. Med Care. 2000;38(2):207–217. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200002000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bosch M, Dijkstra R, Wensing M, van der Weijden T, Grol R. Organizational culture, team climate and diabetes care in small office-based practices. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:180. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brazil K, Wakefield DB, Cloutier MM, Tennen H, Hall CB. Organizational culture predicts job satisfaction and perceived clinical effectiveness in pediatric primary care practices. Health Care Manag Rev. 2010;35(4):365–371. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e3181edd957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Howard M, Brazil K, Akhtar-Danesh N, Agarwal G. Self-reported teamwork in family health team practices in Ontario: organizational and cultural predictors of team climate. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(5):e185–191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hung DY, Leidig R, Shelley DR. What’s in a setting?: influence of organizational culture on provider adherence to clinical guidelines for treating tobacco use. Health Care Manag Rev. 2014;39(2):154–163. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e3182914d11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.King MA, Wissow LS, Baum RA. The role of organizational context in the implementation of a statewide initiative to integrate mental health services into pediatric primary care. Health Care Manag Rev. 2018;43(3):206–217. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Radwan M, Akbari Sari A, Rashidian A, Takian A, Abou-Dagga S, Elsous A. Influence of organizational culture on provider adherence to the diabetic clinical practice guideline: using the competing values framework in Palestinian Primary Healthcare Centers. Int J Gen Med. 2017;10:239–247. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S140140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kralewski J, Dowd BE, Kaissi A, Curoe A, Rockwood T. Measuring the culture of medical group practices. Health Care Manag Rev. 2005;30(3):184–193. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200507000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kralewski JE, Dowd BE, Cole-Adeniyi T, Gans D, Malakar L, Elson B. Factors influencing physician use of clinical electronic information technologies after adoption by their medical group practices. Health Care Manag Rev. 2008;33(4):361–367. doi: 10.1097/01.HCM.0000318773.67395.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mechaber HF, Levine RB, Manwell LB, Mundt MP, Linzer M, Schwartz M, et al. Part-time physicians...prevalent, connected, and satisfied. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(3):300–303. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0514-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Linzer M, Manwell LB, Williams ES, Bobula JA, Brown RL, Varkey AB, et al. Working conditions in primary care: physician reactions and care quality. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(1):28–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-1-200907070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dugan DP, Mick SS, Scholle SH, et al. The relationship between organizational culture and practice systems in primary care. J Ambul Care Manag. 2011;34(1):47–56. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e3181ff6ef2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pracilio VP, Keith SW, McAna J, Rossi G, Brianti E, Fabi M, et al. Primary care units in Emilia-Romagna, Italy: an assessment of organizational culture. Am J Med Qual. 2014;29(5):430–436. doi: 10.1177/1062860613501375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zink T, Kralewski J, Dowd B. The transition of primary care group practices to next generation models: satisfaction of staff, clinicians, and patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(1):16–24. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Linzer M, Poplau S, Prasad K, Khullar D, Brown R, Varkey A, et al. Characteristics of health care organizations associated with clinician trust: results from the Healthy Work Place Study. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Prasad K, Poplau S, Brown R, Yale S, Grossman E, Varkey AB, et al. Time pressure during primary care office visits: a prospective evaluation of data from the Healthy Work Place Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:465–472. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05343-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sarros JC, Gray J, Densten IL, Cooper B. The organizational culture profile revisited and revised: an Australian perspective. Aust J Manag. 2005;30(1):159–182. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zachariadou T, Zannetos S, Pavlakis A. Organizational culture in the primary healthcare setting of Cyprus. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:112. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Glisson C, Landsverk J, Schoenwald S, Kelleher K, Hoagwood KE, Mayberg S, et al. Assessing the organizational social context (OSC) of mental health services: implications for research and practice. Admin Pol Ment Health. 2008;35:98–113. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kramer TL, Drummond KL, Curran GM, Fortney JC. Assessing culture and climate of federally qualified health centers: a plan for implementing behavioral health interventions. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017;28(3):973–987. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2017.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dickinson WP, Dickinson LM, Nutting PA, Emsermann CB, Tutt B, Crabtree BF, et al. Practice facilitation to improve diabetes care in primary care: a report from the EPIC randomized clinical trial. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(1):8–16. doi: 10.1370/afm.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dickinson LM, Dickinson WP, Nutting PA, Fisher L, Harbrecht M, Crabtree BF, et al. Practice context affects efforts to improve diabetes care for primary care patients: a pragmatic cluster randomized trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(4):476–482. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3131-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jortberg BT, Fernald DH, Hessler DM, Dickinson LM, Wearner R, Connelly L, et al. Practice characteristics associated with better implementation of patient self-management support. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32(3):329–340. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2019.03.180124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hall CB, Tennen H, Wakefield DB, Brazil K, Cloutier MM. Organizational assessment in paediatric primary care: development and initial validation of the primary care organizational questionnaire. Health Serv Manag Res. 2006;19:207–214. doi: 10.1258/095148406778951457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hall CB, Brazil K, Wakefield D, et al. Organizational culture, job satisfaction, and clinician turnover in primary care. J Prim Care Community Health. 2010;1(1):29–36. doi: 10.1177/2150131909360990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jaen CR, Crabtree BF, Palmer RF, Ferrer RL, Nutting PA, Miller WL, et al. Methods for evaluating practice change toward a patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:s9–s20. doi: 10.1370/afm.1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Friedberg MW, Reid RO, Timbie JW, Setodji C, Kofner A, Weidmer B, et al. Federally qualified health center clinicians and staff increasingly dissatisfied with workplace conditions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(8):1469–1475. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Poghosyan L, Nannini A, Finkelstein SR, Mason E, Shaffer JA. Development and psychometric testing of the nurse practitioner primary care organizational climate questionnaire. Nurs Res. 2013;62(5):325–334. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3182a131d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Poghosyan L, Aiken LH. Maximizing nurse practitioners’ contributions to primary care through organizational changes. J Ambul Care Manag. 2015;38(2):109–117. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Poghosyan L, Shang J, Liu J, Poghosyan H, Liu N, Berkowitz B. Nurse practitioners as primary care providers: creating favorable practice environments in New York State and Massachusetts. Health Care Manag Rev. 2015;40(1):46–55. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Poghosyan L, Chaplin WF, Shaffer JA. Validation of Nurse Practitioner Primary Care Organizational Climate Questionnaire: a new tool to study nurse practitioner practice settings. J Nurs Meas. 2017;25(1):142–155. doi: 10.1891/1061-3749.25.1.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Poghosyan L, Liu J, Norful AA. Nurse practitioners as primary care providers with their own patient panels and organizational structures: a cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;74:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Poghosyan L, Liu J, Shang J, D'Aunno T. Practice environments and job satisfaction and turnover intentions of nurse practitioners: implications for primary care workforce capacity. Health Care Manag Rev. 2017;42(2):162–171. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Poghosyan L, Norful AA, Liu J, Friedberg MW. Nurse Practitioner practice environments in primary care and quality of care for chronic diseases. Med Care. 2018;56(9):791–797. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Poghosyan L, Ghaffari A, Shaffer J. Nurse practitioner primary care organizational climate questionnaire: item response theory and differential item functioning. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(15-16):2934–2945. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Menezes IG, Sampaio LR, Gomes ACP, Teixeira FS, Santos PS. Organizational climate scale for health organizations: development and factorial structure. Psicol Estud. 2009;26(3):301–316. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cruvinel E, Richter KP, Bastos RR, et al. Screening and brief intervention for alcohol and other drug use in primary care: associations between organizational climate and practice. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2013;8:4. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kolko DJ, Campo J, Kilbourne AM, Hart J, Sakolsky D, Wisniewski S. Collaborative care outcomes for pediatric behavioral health problems: a cluster randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):e981–992. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grace SM, Rich J, Chin W, Rodriguez HP. Implementing interdisciplinary teams does not necessarily improve primary care practice climate. Am J Med Qual. 2016;31(1):5–11. doi: 10.1177/1062860614550333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rodriguez HP, Meredith LS, Hamilton AB, et al. Huddle up!: the adoption and use of structured team communication for VA medical home implementation. Health Care Manag Rev. 2015;40(4):286–299. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Becker ER, Roblin DW. Translating primary care practice climate into patient activation: the role of patient trust in physician. Med Care. 2008;46(8):795–805. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817919c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Friedberg MW, Rodriguez HP, Martsolf GR, Edelen MO, Bustamante AV, Vargas Bustamante A. Measuring workplace climate in community clinics and health centers. Med Care. 2016;54(10):944–949. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Martsolf GR, Ashwood S, Friedberg MW, Rodriguez HP. Linking structural capabilities and workplace climate in community health centers. Inquiry. 2018;55:46958018794542. doi: 10.1177/0046958018794542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Clark W, Avery KL. The effects of data aggregation in statistical analysis. Geogr Anal 1976;8.

- 80.Benzer J, Horner M. A meta-analytic integration and test of psychological climate dimensionality. Hum Resour Manag. 2015;54(3):457–482. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 68 kb)