Abstract

Animal studies have demonstrated the therapeutic potential of polyphenol-rich pomegranate juice. We recently reported altered white matter microstructure and functional connectivity in the infant brain following in utero pomegranate juice exposure in pregnancies with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). This double-blind exploratory randomized controlled trial further investigates the impact of maternal pomegranate juice intake on brain structure and injury in a second cohort of IUGR pregnancies diagnosed at 24–34 weeks’ gestation. Ninety-nine mothers and their eligible fetuses (n = 103) were recruited from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and randomly assigned to 8 oz pomegranate (n = 56) or placebo (n = 47) juice to be consumed daily from enrollment to delivery. A subset of participants underwent fetal echocardiogram after 2 weeks on juice with no evidence of ductal constriction. 57 infants (n = 26 pomegranate, n = 31 placebo) underwent term-equivalent MRI for assessment of brain injury, volumes and white matter diffusion. No significant group differences were found in brain volumes or white matter microstructure; however, infants whose mothers consumed pomegranate juice demonstrated lower risk for brain injury, including any white or cortical grey matter injury compared to placebo. These preliminary findings suggest pomegranate juice may be a safe in utero neuroprotectant in pregnancies with known IUGR warranting continued investigation.

Clinical trial registration: NCT04394910, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04394910, Registered May 20, 2020, initial participant enrollment January 16, 2016.

Subject terms: Randomized controlled trials, Intrauterine growth, Neonatal brain damage

Introduction

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), defined as in utero growth that fails to achieve the full endogenous potential of the fetus1,2, is a serious complication affecting approximately 10 percent of pregnancies worldwide3. Moreover, IUGR is associated with significant risk of perinatal death and neurodevelopmental impairment among surviving infants including cerebral palsy4–9. While the etiology of IUGR is complex and multifactorial, it typically refers to growth-restricted fetuses exposed to chronic periods of hypoxia secondary to placental insufficiency or compromised placental blood flow10,11. The developing fetal brain is particularly vulnerable to the harmful effects of oxidative stress10,12, with the result often similar to that of neurological injury caused by a hypoxic-ischemic event around the time of birth6,7,10,11,13. Importantly, for pregnant mothers with a diagnosis of IUGR, few therapeutic options exist. Indeed, management approaches are largely supportive involving monitoring to balance fetal wellbeing and risk of preterm birth4,14. Thus, there is an urgent need for preventive measures to protect the developing brain in utero, prior to insult, particularly therapies that are safe and well-tolerated during pregnancy.

Polyphenols are a promising source of potential therapeutic capacity. They are a micronutrient class of antioxidants found naturally in foods like green tea, chocolate, nuts, berries and other fruits including pomegranate15. Pomegranate juice is one of the highest polyphenol-containing, commercially available dietary supplements with particularly potent antioxidant capacity due to high bioavailability of biologically active compounds like flavonoids, ellagic acid and ellagitannins. These properties have led to increasing interest in its potential role in the prevention of chronic diseases associated with oxidative stress, such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes and neurodegenerative diseases16–21, although until recently, no studies have examined the effects of prenatal pomegranate juice consumption in humans22.

Pomegranate juice and its derivatives have been studied as potential neuroprotectants in animal models of neurodegeneration, demonstrating benefits in rat models of Alzheimer’s23 and more recently, Parkinson’s disease24. Previous studies have also demonstrated the therapeutic potential of polyphenol consumption in rat models of stroke25 and hypoxic-ischemic injury26,27; with rats whose mothers drank pomegranate juice demonstrating markedly reduced brain tissue loss after an ischemic insult26. Notably, the degree of neuroprotection increased with increased pomegranate intake26,27. Neuroprotectant effects have also been reported in human studies of adult ischemic stroke, with patients randomized to pomegranate pills equivalent to 8 oz daily demonstrating improved cognitive and functional recovery compared with placebo28. There have further been reports of memory improvement and increased functional MRI activity during verbal and visual memory tasks in adults following 4 weeks’ daily pomegranate juice consumption29,30.

We recently reported differences in white matter microstructure and resting state connectivity within visual networks in IUGR infants born to mothers who consumed pomegranate juice compared to placebo22, representing to the best of our knowledge the only study of prenatal pomegranate juice exposure and the developing human brain. In the current study we sought to continue to explore the neuroprotectant potential of pomegranate juice by further investigating associations between pomegranate juice consumption and neonatal brain injury, volumes and white matter microstructure in a second site involving IUGR pregnancies presenting at a major tertiary hospital in Boston, MA. We also addressed gaps from our earlier trial by establishing baseline fetal brain injury prior to juice consumption, and further assessed the safety of high polyphenol intake on fetal ductal constriction31–33 using fetal echocardiograms. Neurodevelopmental follow-up at 18–36 months is ongoing and will form the focus of a subsequent publication.

Results

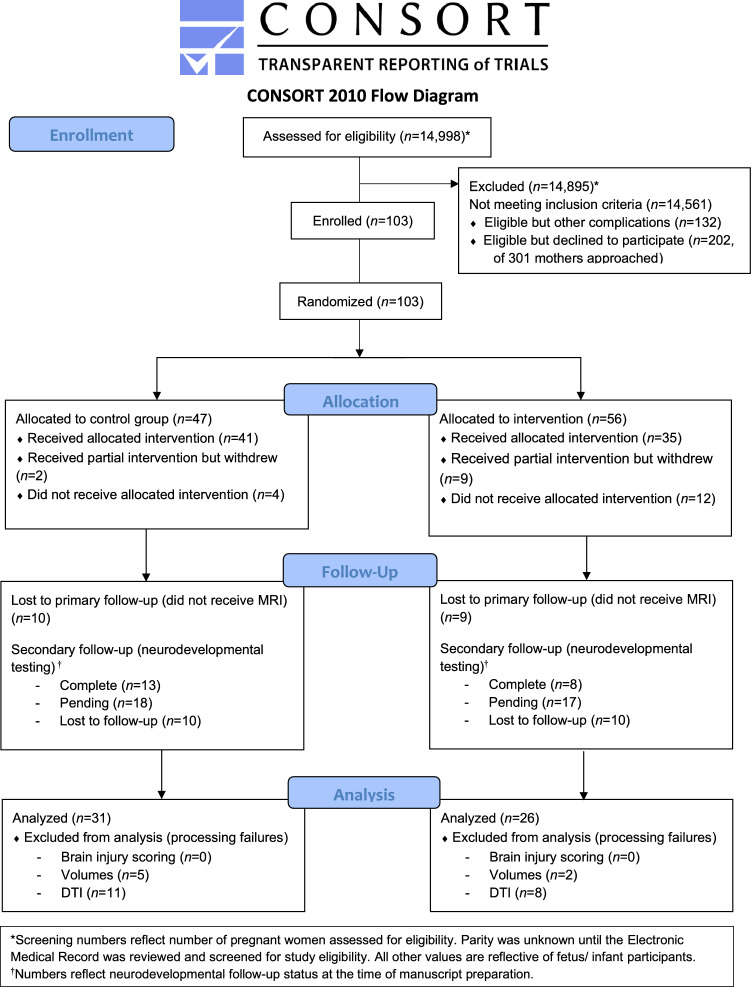

Ninety-nine mothers and their 103 eligible IUGR fetuses were enrolled and randomly assigned to either treatment (pomegranate juice, n = 56) or placebo (n = 47) arms (Fig. 1). Of the fetuses randomized to the placebo arm, six (12.8%) were withdrawn from the study: two subjects received partial intervention before withdrawing (n = 1 for hyperemesis, n = 1 for ductal closure in non-eligible (non-IUGR) co-triplet on first echocardiogram), and four did not receive any intervention (delivered early). Of the 41 fetuses who received the allocated placebo intervention, 31 (66%) underwent term-equivalent brain MRI. Among the fetuses randomized to the treatment arm, 21 (37.5%) were withdrawn from the study: nine received partial intervention but withdrew (n = 6 aversion to juice, n = 1 postnatal genetic anomaly diagnosis, n = 1 overwhelmed with pregnancy, n = 1 delivering early), and 12 did not receive any intervention (n = 6 no longer interested, n = 2 congenital anomaly diagnosed after enrollment, n = 4 delivered prior to intervention). Of the 35 fetuses who received the allocated treatment intervention, 26 (74.3%) underwent term-equivalent brain MRI.

Figure 1.

CONSORT participant flowchart.

Baseline characteristics and participant outcomes

There were no differences in estimated fetal weight or IUGR growth percentile between study arms at enrollment (Table 1). The groups were largely similar in other baseline and demographic characteristics in both modified intention-to-treat (mITT) and per protocol (PP) analyses; the latter restricted to participants who adhered to the protocol based on metabolite status. Mothers in the placebo group had significantly higher BMI at enrollment than mothers in the treatment group in both mITT (p = 0.009) and PP (p = 0.040) analyses. Infants in the treatment group were more likely to be born SGA than those in the placebo group in both mITT (p = 0.015) and PP (p = 0.031) analyses. This difference is a result of the differential rates of follow-up in the two study arms; with infants lost to follow up (n = 46) more likely to be from the treatment group (65.2% vs. 45.6%, p = 0.047), compared with infants who underwent infant MRI (mITT total, n = 57), and more likely to be appropriate for gestational age (AGA) (62.5% vs. 40.4%, p = 0.012); there was no difference in SGA status among total enrolled sample (Table 1). Participants lost to follow-up were also born slightly younger (median (IQR) 35 (33–37) vs 36 (33–37) weeks’ GA, p = 0.032), and were more likely to be born preterm (< 37 weeks’ GA), 69.6% vs 58.3%, p = 0.037) compared with infants who underwent infant MRI, although these differences did not vary by study arm.

Table 1.

Baseline maternal and fetal characteristics and neonatal outcomes of study participants.

| Total enrolled | Modified intention-to-treat | Per-protocol | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 47) | POM (n = 56) | Placebo (n = 31) | POM (n = 26) | Placebo, metabolite − ve (n = 17) | POM, metabolite + ve (n = 17) | |

| Baseline characteristics | ||||||

| Maternal age (yrs), mean (SD) | 31.5 (6.8) | 29.2 (6.5) | 30.5 (5.8) | 27.4 (5.5) | 30.4 (5.9) | 28.0 (5.5) |

| Maternal BMI, median (IQR) | 29.9 (26.5, 36.5) | 27.7 (24.3, 32.5)* | 31.2 (26.5, 37.3) | 25.9 (24.2, 30.4)* | 31.8 (29.6, 40.7) | 26.1 (24.2, 30.4)* |

| Race, Black n (%) | 16 (34.0) | 21 (37.5) | 8 (25.8) | 10 (38.5) | 5 (29.4) | 5 (29.4) |

| Race, Caucasian n (%) | 12 (25.5) | 15 (26.8) | 9 (29.0) | 6 (23.1) | 2 (11.8) | 5 (29.4) |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic/Latino n (%) | 13 (27.7) | 16 (28.6) | 9 (29.0) | 8 (30.8) | 6 (35.3) | 5 (29.4) |

| Nulliparous, n (%) | 16 (34.0) | 26 (46.4) | 12 (38.7) | 14 (53.9) | 8 (47.1) | 9 (52.9) |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 2 (4.3) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Past smoking, n (%) | 14 (29.8) | 12 (21.4) | 8 (25.8) | 6 (23.1) | 2 (11.8) | 3 (17.7) |

| Sickle cell trait, n (%) | 2 (4.3) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (5.9) |

| Past/current diabetes and/or gestational diabetes, n (%) | 2 (4.3) | 5 (8.9) | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.9) |

| Multiples, n (%) | 13 (27.7) | 17 (30.4) | 9 (29.0) | 5 (19.2) | 4 (23.5) | 4 (23.5) |

| Gestational age at enrollment (wks), median (IQR) | 31.4 (29.0, 33.0) | 29.9 (27.3, 32.0) | 31.9 (29.7, 33.1) | 30.7 (27.3, 32.9) | 31.4 (29.7, 32.0) | 30.6 (27.3, 31.9) |

| Estimated fetal weight at enrollment (g), mean (SD) | 1242.5 (433.2) | 1140.5 (419.3) | 1265.4 (431.1) | 1157.7 (502.2) | 1183.9 (375.0) | 1136.1 (490.9) |

| Growth percentile at enrollment, median (IQR) | 3 (1, 4) | 2 (1, 4) | 3 (1, 4) | 1.5 (0, 5) | 3 (1, 4) | 1 (0, 5) |

| Steroids for fetal lung immaturity, n (%) | 15 (31.9) | 13 (23.2) | 9 (29.0) | 5 (19.2) | 4 (23.5) | 3 (17.6) |

| Delivery outcomes | ||||||

| Gestational age at delivery (wks), median (IQR) | 35.0 (34.0, 37.0) | 36.0 (33.0, 37.0) | 35.0 (34.0, 37.0) | 37.0 (34.0, 38.0) | 35.0 (34.0, 37.0) | 37.0 (36.0, 38.0) |

| Gestational age at MRI scan, (wks), median (IQR) | 40.0 (38.4, 41.4) | 39.5 (38.1, 40.0) | 40.0 (38.4, 41.4) | 39.5 (38.1, 40.0) | 39.7 (37.7, 41.4) | 39.6 (38.6, 39.9) |

| Preterm birth < 37 weeks, n (%) | 29 (61.7) | 31 (55.4) | 18 (58.1) | 10 (38.5) | 8 (47.1) | 6 (35.3) |

| Preterm birth < 34 weeks, n (%) | 10 (21.3) | 18 (32.1) | 7 (22.6) | 5 (19.2) | 3 (17.6) | 2 (11.8) |

| Mode of delivery (vaginal), n (%) | 25 (53.2) | 30 (53.6) | 15 (48.4) | 18 (69.2) | 10 (58.8) | 12 (70.6) |

| Meconium stained amniotic fluid, n (%) | 3 (6.4) | 1 (1.8) | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Neonatal outcomes | ||||||

| Female sex, n (%) | 27 (57.5) | 29 (51.8) | 18 (58.1) | 11 (42.3) | 11 (64.7) | 7 (41.2) |

| Birthweight (g), mean (SD) | 1993.0 (647.7) | 1953.5 (610.0) | 2032.8 (617.9) | 2018.3 (572.5) | 2060.9 (571.4) | 2064.2 (476.2) |

| Birthweight Z-score, median (IQR) | − 1.1 (− 1.9, − 0.8) | − 1.35 (− 1.9, − 0.9) | − 1.2 (− 1.9, − 0.8) | − 1.6 (− 2.0, − 1.3) | − 1.1 (− 1.6, − 0.8) | − 1.9 (− 2.1, − 1.4)* |

| Small for gestational age, n (%) | 20 (42.6) | 30 (53.6) | 14 (45.2) | 20 (76.9)* | 8 (47.1) | 14 (82.4)* |

| APGAR score at 1 min, median (IQR) | 8 (7, 8) | 8 (7, 8) | 8 (7, 8) | 8 (7, 8) | 8 (7, 8) | 8 (8, 8) |

| APGAR score at 5 min, median (IQR) | 9 (8, 9) | 9 (8, 9) | 9 (8, 9) | 9 (8, 9) | 9 (9, 9) | 9 (9, 9) |

| Cord arterial pH1, median (IQR) | 7.2 (7.2, 7.2) | 7.3 (7.3, 7.3) | 7.2, (7.2, 7.2) | 7.3, (7.3, 7.3) | 7.2 | 7.3 |

| Cord arterial base excess1, median (IQR) | 5.2 (4.9, 5.8) | 4.1 (2.9, 9.6) | 5.8 (4.9, 9.7) | 2.3 (1.6, 2.9) | 9.7 | 1.6 |

| Respiratory distress syndrome, n (%) | 8 (17.0) | 12 (21.4) | 6 (19.4) | 3 (11.5) | 3 (17.7) | 1 (5.9) |

*p < 0.05 POM vs. placebo (placebo = reference).

1Cord gas data available for 3 infants in placebo mITT, 2 infants in POM mITT, 1 infant in placebo PP, 1 infant in POM PP.

Among total enrolled sample pH data available for 7 infants in placebo, 7 infants in POM; base excess data available for 6 infants in placebo, 7 infants in POM.

Brain outcomes

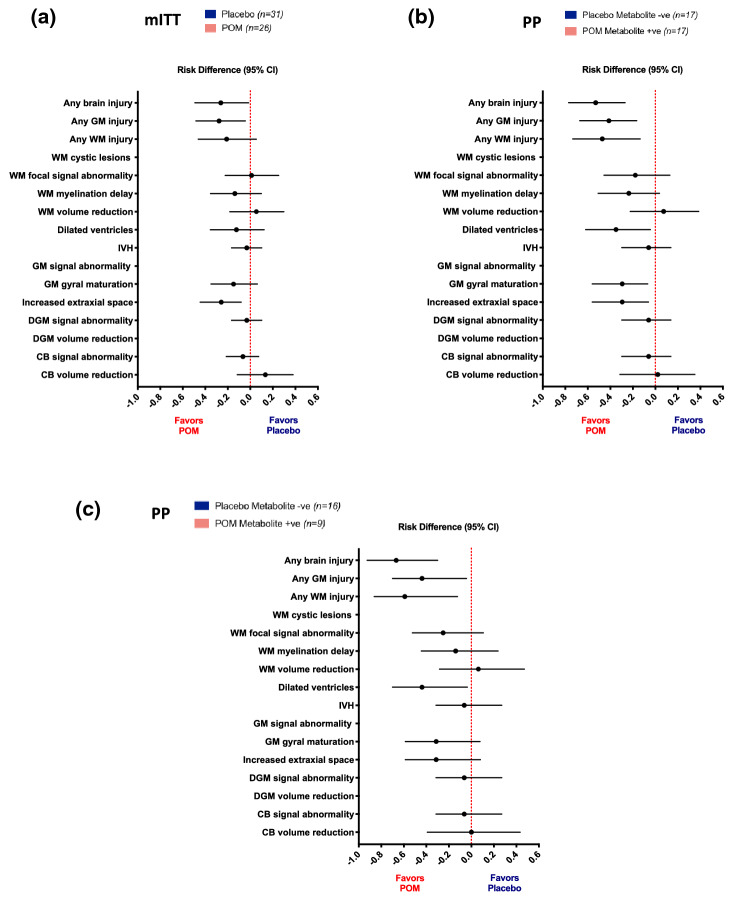

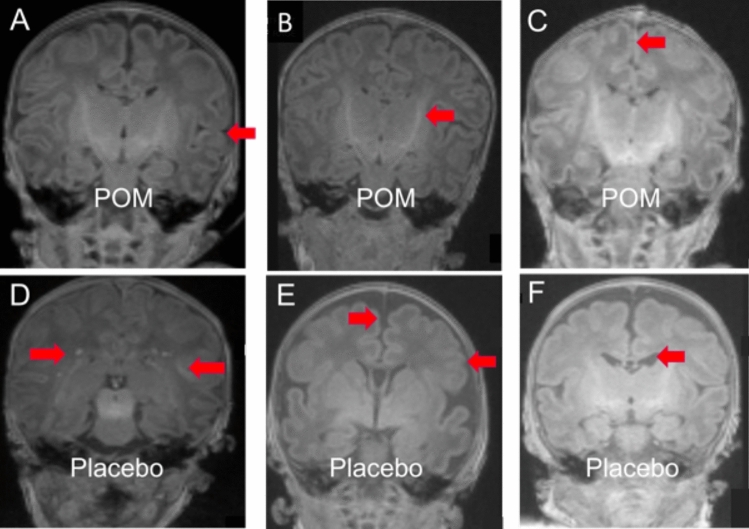

There was no evidence of fetal brain injury in any of the participants who underwent fetal MRI prior to starting the allocated juice regimen. We did not observe group differences in total or regional brain volumes, or in DTI measures (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2), however significant risk differences were detected between groups in brain injury measures using the Kidokoro scoring system in both mITT and PP analyses (Table 2, Fig. 2a,b)34. T1-weighted coronal MRIs demonstrating representative brain injury scoring are shown in Fig. 3.

Table 2.

Neonatal brain injury frequency and risk comparison by study arm.

| Modified intention-to-treat | Placebo (n = 31) | POM (n = 26) | Group comparison | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 0 | Grade ≥ 1 | Grade 0 | Grade ≥ 1 | Risk difference1 (95% CI) | Relative risk2 (95% CI) | |

| WM cystic lesions | 31 (100) | 0 (0) | 26 (100) | 0 (0) | N/A | N/A |

| WM focal signal abnormality | 23 (74.2) | 8 (25.8) | 19 (73.1) | 7 (26.9) | 0.01 (− 0.22, 0.25) | 1.04 (0.38, 2.63) |

| WM myelination delay | 22 (71.0) | 9 (29.0) | 22 (84.6) | 4 (15.4) | − 0.14 (− 0.35, 0.10) | 0.53 (0.08, 1.48) |

| WM volume reduction3 | 24 (77.4) | 7 (22.6) | 18 (72.0) | 7 (28.0) | 0.05 (− 0.18, 0.30) | 1.24 (0.44, 3.49) |

| Dilated ventricles3 | 21 (67.7) | 10 (32.3) | 20 (80.0) | 5 (20.0) | − 0.12 (− 0.36, 0.12) | 0.62 (0.17, 1.57) |

| GM signal abnormality | 31 (100) | 0 (0) | 26 (100) | 0 (0) | N/A | N/A |

| GM gyral maturation | 24 (77.4) | 7 (22.6) | 24 (92.3) | 2 (7.7) | − 0.15 (− 0.35, 0.06) | 0.34 (0.04, 1.39) |

| Increased extra-axial space3 | 23 (74.2) | 8 (25.8) | 25 (100) | 0 (0) | − 0.26 (− 0.45, − 0.08)* | 0.75 (0.60, 0.93)* |

| DGM signal abnormality | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | 26 (100) | 0 (0) | − 0.03 (− 0.17, 0.10) | 0.97 (0.89, 1.07) |

| DGM volume reduction3 | 31 (100) | 0 (0) | 25 (100) | 0 (0) | N/A | N/A |

| Cerebellar signal abnormality | 29 (93.5) | 2 (6.5) | 26 (100) | 0 (0) | − 0.07 (− 0.21, 0.07) | 0.94 (0.84, 1.05) |

| Cerebellar volume reduction3 | 24 (77.4) | 7 (22.6) | 16 (64.0) | 9 (36.0) | 0.13 (− 0.12, 0.38) | 1.59 (0.64, 4.07) |

| IVH | 30 (96.8) | 1 (3.2) | 26 (100) | 0 (0) | − 0.03 (− 0.17, 0.10) | 0.97 (0.89, 1.07) |

| Any WM injury | 9 (29.0) | 22 (71.0) | 13 (50.0) | 13 (50.0) | − 0.21 (− 0.46, 0.05) | 0.71 (0.38, 1.10) |

| Any GM injury | 20 (64.5) | 11 (35.5) | 24 (92.3) | 2 (7.7) | − 0.28 (− 0.48, − 0.05)* | 0.22 (0.02, 0.89)* |

| Any brain injury | 5 (16.1) | 26 (83.9) | 11 (42.3) | 15 (57.7) | − 0.26 (− 0.49, − 0.02)* | 0.69 (0.42, 0.98)* |

| Per protocol | Placebo, metabolite − ve (n = 17) | POM, metabolite + ve (n = 17) | Group comparison | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 0 | Grade ≥ 1 | Grade 0 | Grade ≥ 1 | Risk difference1 (95% CI) | Relative risk2 (95% CI) | |

| WM cystic lesions | 17 (100) | 0 (0) | 17 (100) | 0 (0) | N/A | N/A |

| WM focal signal abnormality | 12 (70.6) | 5 (29.4) | 15 (88.2) | 2 (11.8) | − 0.18 (− 0.46, 0.13) | 0.40 (0.06, 1.83) |

| WM myelination delay | 12 (70.6) | 5 (29.4) | 16 (94.1) | 1 (5.9) | − 0.24 (− 0.51, 0.04) | 0.20 (0.03, 1.54) |

| WM volume reduction3 | 14 (82.4) | 3 (17.7) | 12 (75.0) | 4 (25) | 0.07 (− 0.22, 0.39) | 1.42 (0.34, 8.05) |

| Dilated ventricles3 | 10 (58.8) | 7 (41.2) | 15 (93.8) | 1 (6.3) | − 0.35 (− 0.62, − 0.04)* | 0.15 (0.01, 0.87)* |

| GM signal abnormality | 17 (100) | 0 (0) | 17 (100) | 0 (0) | N/A | N/A |

| GM gyral maturation | 12 (70.6) | 5 (29.4) | 17 (100) | 0 (0) | − 0.29 (− 0.56, − 0.07)* | 0.71 (0.52, 0.98)* |

| Increased extra-axial space3 | 12 (70.6) | 5 (29.4) | 16 (100) | 0 (0) | − 0.29 (− 0.56, − 0.06)* | 0.72 (0.52, 0.98)* |

| DGM signal abnormality | 16 (94.1) | 1 (5.9) | 17 (100) | 0 (0) | − 0.06 (− 0.30, 0.14) | 0.94 (0.80, 1.11) |

| DGM volume reduction3 | 17 (100) | 0 (0) | 16 (100) | 0 (0) | N/A | N/A |

| Cerebellar signal abnormality | 16 (94.1) | 1 (5.9) | 17 (100) | 0 (0) | − 0.06 (− 0.30, 0.14) | 0.94 (0.80, 1.11) |

| Cerebellar volume reduction3 | 11 (64.7) | 6 (35.3) | 10 (62.5) | 6 (37.5) | 0.02 (− 0.31, 0.35) | 1.06 (0.35, 3.22) |

| IVH | 16 (94.1) | 1 (5.9) | 17 (100) | 0 (0) | − 0.06 (− 0.297, 0.138) | 0.94 (0.80, 1.11) |

| Any WM injury | 3 (17.6) | 14 (82.4) | 11 (64.7) | 6 (35.3) | − 0.47 (− 0.73, − 0.14)* | 0.43 (0.17, 0.83)* |

| Any GM injury | 10 (58.8) | 7 (41.2) | 17 (100) | 0 (0) | − 0.41 (− 0.67, − 0.17)* | 0.60 (0.40, 0.89)* |

| Any brain injury | 0 (0) | 17 (100) | 9 (52.9) | 8 (47.1) | − 0.53 (− 0.77, − 0.27)* | 0.47 (0.23, 0.72)* |

Group summaries are n (%).

Group comparisons tested using exact methods due to small sample size (i.e. cell counts < 5).

*p < 0.05.

1Absolute effect size reported as the risk difference (placebo = reference). Corresponding 95% confidence intervals are reported.

2Relative effect size reported as relative risk (placebo = reference). For analyses with zero in one or more cells, 0.5 was added to each cell prior to calculation of the relative risk. Corresponding 95% confidence intervals are reported.

3Metric-based data unavailable for 1 POM infant (not possible due to incomplete acquisition).

DGM deep grey matter; GM cortical grey matter; IVH intraventricular hemorrhage; POM pomegranate; WM white matter.

Figure 2.

Brain injury risk by study arm on mITT and PP analysis. Risk difference and 95% confidence intervals are shown (Placebo = reference). Lines to the left of 0 favor pomegranate juice, i.e. infants randomized to pomegranate juice demonstrate lower risk of brain injury compared with infants randomized to placebo. Lines that do not cross 0 denote a significant difference in risk, p < 0.05. (a) Modified intention-to-treat (mITT) analysis. (b) PP analysis. (c) PP analysis excluding infants born to mothers positive for metabolites at enrollment. CB cerebellum; DGM deep grey matter; GM cortical grey matter; IVH intraventricular hemorrhage; POM pomegranate; WM white matter.

Figure 3.

Representative brain MRIs demonstrating Kidokoro injury scoring34. T1-weighted coronal slices from six representative infants exposed in utero to pomegranate juice (top row) or placebo (bottom row). (A–C) No injury detected—normal scores for gyral maturation, PLIC myelination, extra-axial space/IHD (arrows). (D–F) Representative injury categories detected; (D)—2 points for WM focal signal abnormality (arrows); (E)—2 points for focal signal abnormality, 1 point for myelination delay, 1 point for gyral maturation delay (arrow), 1 point for IHD (arrow); (F)—1 point for gyral maturation delay, 2 points for IHD, 2 points for lateral ventricle enlargement (arrow). IHD interhemispheric distance; PLIC posterior limb of the internal capsule; WM white matter.

Infants randomized to pomegranate juice were less likely to demonstrate any brain injury compared to those randomized to placebo (mITT 57.7% vs. 83.9%; PP 47.1% vs. 100%), with approximately 30 to 50% lower risk of any brain injury in mITT and PP analyses, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 2a,b, Supplementary Tables S4-S6). More specifically, infants born to mothers receiving pomegranate juice demonstrated lower risk of any cortical grey matter injury, including lower risk of increased extra-axial space (interhemispheric distance, IHD) and gyral maturation delay, relative to infants in the placebo group. Infants exposed to pomegranate juice further demonstrated lower risk of any white matter injury, including lower risk of enlarged lateral ventricles compared with placebo infants. Although there were no statistically significant differences between groups for several white matter injury components, including cysts and focal signal abnormalities, infants in the treatment arm demonstrated notably lower frequency of delayed myelination particularly in PP analyses (5.9% vs. 29.4%) compared with placebo (Table 2, Fig. 2b).

While we identified differences in SGA and maternal BMI by study arm, brain injury analyses were not adjusted for either as there was no association between these covariates and injury outcome, with the exception of an association between maternal obesity (BMI > 30) and extra-axial space and dilated ventricles in mITT and PP analyses, respectively. To assess maternal obesity as a potential confounder in the association between study arm and extra-axial space and dilated ventricles in mITT and PP analyses, we performed supplemental stratified analysis by obesity status and observed greater frequency of injury among infants whose mothers were randomized to placebo compared to those randomized to pomegranate juice, irrespective of maternal obesity status (Supplementary Table S7), consistent with results from unadjusted analyses.

As part of the injury scoring system34, continuous measures were first generated for white matter (biparietal diameter), deep grey matter (total basal ganglia area) and cerebellar (trans-cerebellar diameter) volume reduction, and for ventricular dilatation (ventricular diameter) and extra-axial cerebrospinal fluid-filled space (IHD) prior to conversion to their corresponding scores. We performed supplemental analysis exploring group differences in these continuous measures using median regression and found no differences by study arm (Supplementary Table S3). Further exploration of the variable distributions by study arm indicated that, for increased extra-axial space and enlarged ventricles, the placebo arm presented longer right tails in its distributions relative to the treatment arm, with greater differences between study arms observed at upper quartiles. Furthermore, while we observed differences in the corresponding categorical measures, injury score cut-offs for ventricular (one side > 7.5 mm) and IHD (> 4 mm) measures34 in the placebo arm were located within the right tail of these distributions, such that we did not observe differences in the central tendencies of these distributions (Supplementary Table S3).

Compliance

There were no significant differences in the time period on juice or in the recorded days of juice consumption between study arms (Table 3). Maternal metabolite presence (either UA or DMEAG present in blood or urine) at enrollment also did not differ between groups in mITT analysis, with 27.6% and 32.0% of mothers being metabolite positive before starting the juice regimen in the placebo and treatment arms, respectively. Of note, in PP analysis, there was a higher prevalence of maternal metabolite presence at enrollment in the treatment arm than in placebo (50.0% vs. 5.9%, p = 0.007, Table 3).

Table 3.

Measures of compliance.

| Modified intention-to-treat | Per protocol | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 31) | POM (n = 26) | Absolute effect size1 | Relative effect size2 | SE2 | / | P value | Placebo, metabolite − ve (n = 17) | POM, metabolite + ve (n = 17) | Absolute effect size1 | Relative effect size2 | SE2 | / | P value | |

| Time period on juice in days, median (IQR) | 19 (11, 34) | 28.5 (19, 46) | 9.50 | 0.37 | 2.43 | 1.73 | 0.083 | 28 (13, 39) | 33 (25, 47) | 5.00 | 0.34 | 3.23 | 1.19 | 0.234 |

| Recorded days of consumption, median (IQR)3 | 17 (10.5, 30.5) | 35 (22.5, 47.5) | 18.00 | 0.52 | 3.38 | 1.85 | 0.064 | 27 (15.5, 34.5) | 36 (25, 52.5) | 9.00 | 0.57 | 4.13 | 1.03 | 0.301 |

| Maternal UA or DMEAG plasma at enrollment, n (%) | 2 (6.9)a | 3 (13.0)d | 6.15% | 1.89 | 0.08 | 0.644 | 1 (5.9) | 3 (21.4)f | 15.55% | 3.64 | 0.12 | 0.304 | ||

| Maternal UA or DMEAG urine at enrollment, n (%) | 8 (27.6)a | 8 (32.0)c | 4.41% | 1.16 | 0.12 | 0.125 | 0.723 | 1 (5.9) | 8 (50.0)g | 44.12% | 8.50 | 0.16 | 0.007 | |

| Positive for metabolites in plasma or urine at enrollment, n (%) | 8 (26.7)b | 8 (32.0)c | 5.33% | 1.20 | 0.12 | 0.188 | 0.664 | 1 (5.9) | 8 (50.0)g | 44.12% | 8.50 | 0.16 | 0.007 | |

| Maternal UA or DMEAG plasma at delivery, n (%) | 3 (12.0)c | 9 (40.9)e | 28.91% | 3.41 | 0.13 | 0.042 | 0 (0)h | 9 (60.0)h | 60.00% | 19.00 | 0.16 | < .001 | ||

| Maternal UA or DMEAG urine at delivery, n (%) | 13 (41.9) | 16 (64.0)c | 22.06% | 1.53 | 0.13 | 2.699 | 0.100 | 0 (0) | 16 (94.1) | 94.12% | 33.00 | 0.17 | < .001 | |

| Cord UA or DMEAG at delivery, n (%) | 2 (8.7)d | 9 (39.1)d | 30.43% | 4.50 | 0.13 | 0.035 | 0 (0)i | 9 (64.3)i | 64.29% | 19.00 | 0.17 | < .001 | ||

| Positive for metabolites in cord blood or maternal blood or urine at delivery, n (%) | 14 (45.2) | 17 (65.4) | 20.22% | 1.45 | 0.13 | 2.331 | 0.127 | 0 (0) | 17 (100.0) | 100.00% | 35.00 | 0.17 | < .001 | |

Group comparisons evaluated using Wilcoxon rank sum and χ2 tests, as appropriate.

Fisher’s exact test (2-sided) used to compare proportions by group where expected cell counts < 5.

1Absolute effect size calculated as the median difference for continuous variables, and the risk difference (%) for categorical variables (placebo = reference).

2Relative effect size calculated as Cohen’s d for continuous variables, and the relative risk for categorical variables (placebo = reference). For analyses with zero in one or more cells, 0.5 was added to each cell prior to calculation of the relative risk and its standard error (SE). Corresponding SE are reported.

3Logbook data available for 19 infants in placebo mITT, 11 infants in POM mITT, 11 infants in placebo PP, 8 infants in POM PP.

an = 29; bn = 30; cn = 25; dn = 23; en = 22; fn = 14; gn = 16; hn = 15; in = 14.

DMEAG dimethylellagic acid glucuronid; IQR interquartile range; POM pomegranate; SE standard error; UA urolithin A.

In mITT analysis, there was higher metabolite detection at delivery in the treatment arm compared to placebo in plasma (40.9% vs. 12%, p = 0.042), urine (64% vs. 41.9%, p = 0.1), and cord blood (39.1% vs. 8.7%, p = 0.035). However, a large number of placebo participants (45.2%) were positive for metabolites at delivery, detected in either cord blood, maternal blood or maternal urine.

Due to the variability of metabolite presence both at enrollment and delivery between groups, PP analyses were performed using strict metabolite criteria, which included only placebo participants who were metabolite-negative at delivery, and treatment participants who were metabolite-positive at delivery.

To further address the difference in maternal metabolite presence between study arms at enrollment in PP analyses and any potential confounding due to non-random baseline metabolite positivity, we reran PP analyses for brain injury outcomes, excluding the 9 infants born to mothers who were positive for metabolites at enrollment. While associations for gyral maturation, extra-axial space and lateral ventricles lost statistical significance, this was due to a reduction in power, with no change in the number of infants with injury in either study arm (5 (31.3%) placebo infants with gyral maturation delay, and 5 (31.3%) placebo infants with increased extra-axial space compared with 0 infants with either injury in the treatment arm). Findings for white matter injury, cortical grey matter injury and any brain injury further remained unchanged, maintaining statistical significance (Fig. 2c).

Safety assessment

Safety was assessed in infants born to mothers who completed either full or partial juice regimen (total n = 87). No differences were observed between groups with respect to any complications (Table 4). As part of Phase 1, 17 participants (8 in placebo, 9 in treatment) underwent two fetal echocardiograms: one before starting the juice regimen, and one approximately two weeks after starting daily juice consumption in order to investigate whether a diet rich in polyphenol-rich foods can lead to fetal ductal constriction31–33. There was no evidence of ductal constriction in either the treatment or placebo groups in association with juice consumption. As no adverse events were reported, no stopping rules were implemented.

Table 4.

Safety measures.

| Complication | Placebo (n = 43) | POM (n = 44) | Risk difference1 (%) | Relative risk2 | SE2 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NICU admission, n (%) | 22 (51.2) | 25 (56.8) | 5.66 | 1.11 | 0.11 | 0.28 | 0.597 |

| Respiratory distress, n (%) | 7 (16.3) | 6 (13.6) | − 2.64 | 0.84 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.730 |

| Resuscitation at delivery, n (%) | 2 (4.7) | 2 (4.6) | − 0.11 | 0.98 | 0.04 | 1.000 | |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage, n (%) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0) | − 2.33 | 0.33 | 0.03 | 0.494 | |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.3) | 2.27 | 2.93 | 0.03 | 1.000 | |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.02 | N/A |

Group comparisons evaluated using Wilcoxon rank sum and χ2 tests, as appropriate.

Fisher’s exact test (2-sided) used to compare proportions by group where cell counts < 5.

1Absolute effect size calculated as the risk difference (%, placebo = reference).

2Relative effect size calculated as the relative risk for categorical variables (placebo = reference). For analyses with zero in one or more cells, 0.5 was added to each cell prior to calculation of the relative risk and its standard error (SE). Corresponding SE are reported.

NICU neonatal intensive care unit; POM pomegranate; SE standard error.

Discussion

In this double-blind, exploratory randomized controlled trial we present findings suggesting in utero exposure to polyphenol-rich pomegranate juice may reduce the risk of perinatal brain injury in the at-risk infant with IUGR. No injury was observed on fetal MRI in the subset of infants who underwent fetal MRI prior to the start of juice consumption, indicating that the reported brain injury occurred during the third trimester, over the course of the juice regimen. Our findings therefore suggest that maternal pomegranate juice intake may have a beneficial effect during a period of marked brain vulnerability such as late gestation. Furthermore, while recent reports have suggested that a polyphenol-rich diet can lead to fetal ductal constriction31–33, we did not observe any instances of ductal constriction related to maternal intake of 8 oz pomegranate juice, suggesting its daily consumption is safe and without attributable side effects.

Although the underlying mechanisms are not yet fully understood, pomegranate juice and its derivatives have demonstrated anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic properties35, and have been shown to act as cytoprotective agents through direct scavenging of reactive oxygen species, and increased antioxidant enzymatic response36, suggesting multiple potential modes of action. While the relationships between impaired placental perfusion, oxygen and nutrient transfer disturbances and subsequent brain abnormality in IUGR remain unclear, it is possible that the observed brain injury may reflect a primary or secondary dysmaturational event. We had initially postulated that pomegranate juice may exert its protective effect on the placenta, leading to improved outcomes for the fetus, including reduced brain injury. Indeed, using a hypoxia-induced growth restriction mouse model, Chen et al. reported decreased placental heat shock protein expression and apoptosis in pregnant dams who received pomegranate juice compared to glucose37. Notably, pregnant dams consumed juice prior to and in conjunction with hypoxic exposure, suggesting that antecedent pomegranate juice may be critical for placental protection. In our study, however, IUGR was not diagnosed until late in the second trimester, such that by the time the juice regimen is started, it is likely too late post-implantation to change the placental villous structure. Indeed, secondary analysis of our earlier cohort has shown no difference in placental pathology between pomegranate and placebo arms38, suggesting the lower injury risks reported in the current study may reflect a distinct cerebral effect of pomegranate juice. Future assessment of placental morphometry and pathology will provide added insight into potential differential placental and cerebral protection.

The pathophysiology of perinatal brain injury, including that following IUGR, is complex with varying degrees of grey and white matter involvement, depending on the nature, location, timing and severity of the injury39–43. Our findings for lower risk of white matter injury associated with pomegranate juice exposure may suggest a beneficial effect on pre-oligodendrocyte (pre-OL) maturation, a dominant feature of cerebral white matter development during late gestation44,45, and the period during which enrolled mothers consumed juice. Pre-OL vulnerability to oxidative attack is well established, and has been postulated to relate to the lack of white matter antioxidant capacity before birth, rendering the immature white matter susceptible to free radical toxicity as the fetus transitions to an oxygen-rich postnatal environment13,46. Thus, our white matter findings appear to be consistent with potential benefit via reduced susceptibility to redox status perturbations and improved oligodendrocyte maturation or sparing. Relatedly, while we did not observe significant differences in myelination, likely due to sample size limitations, infants in the treatment arm demonstrated notably lower frequency of delayed myelination on PP analyses.

Our findings of lower grey matter injury risk may reflect associated sparing of secondary axonal disturbance and impaired gray matter maturation45,47. Cerebral cortex undergoes dramatic expansion during the last trimester48–51 characterized by increased complexity of neuronal processes, synaptogenesis, and tertiary folding49,52. Cortical developmental vulnerability including impaired gyrification has been demonstrated in growth-restricted fetuses and preterm infants with IUGR6,7,53,54, and has been linked to subplate neurons beneath the developing cortical plate41,55–58 and their susceptibility to hypoxic injury and excitotoxic cell death59. Furthermore, and similar to pre-OLs, peak subplate neuron development occurs between 24–32 weeks’ gestation before undergoing programmed cell death60,61. Of note, our previous findings of greater functional connectivity in visual networks would appear to lend support to a beneficial effect at the level of subplate neurons22, given their implication in normal visual cortical development62 and roles in early establishment of thalamocortical connections to visual cortex56,57,62. Our findings for gyral maturation also appear to be consistent with potential sparing of upper cortical neurons over this period; given disturbances in late migration of GABAergic neurons destined for upper cortical layers have been proposed to lead to gyral maturation delay47,63.

The observed lower frequency of enlarged ventricles and increased extra-axial space may reflect associated cortical tissue sparing. Of note, brain injury scoring in the current study incorporated both qualitative signal abnormality scores as well as scores based on continuous quantitative biometrics34. For ventricular and IHD measures, differences between study arms observed using categorical scores appeared to be masked in analyses using continuous measures, because the corresponding injury scoring cut-offs were located within the right tail of these distributions. This may explain the lack of observable group differences in our earlier trial where brain metric measures were assessed separately from signal abnormality measures22.

Given the exploratory nature of the current study, larger controlled trials are needed to better assess the aforementioned relationships and speculative mechanisms before definitive conclusions can be drawn. Longitudinal studies to track the pre-post-conception effects of pomegranate juice on injury evolution, brain development and linear growth in the growth-restricted population may also be merited. The latter is of particular interest given a recent animal study suggesting maternal consumption of pomegranate juice may not be beneficial for fetal growth restriction64. While the authors reported reduced litter size and biometric measurements, these findings are difficult to extrapolate to the more complex etiology of human IUGR. Importantly, they did not observe differences in fetal weight related to pomegranate juice consumption64. In line with this, our observed group differences in SGA by study arm were due to a differential loss to follow up of AGA infants in the treatment arm, with no group differences in SGA among total enrolled sample, suggesting the higher frequency of SGA in the treatment arm was not due to a pomegranate juice effect.

While the results of this study appear to be consistent with the hypothesized therapeutic potential of prenatal pomegranate juice, there are several limitations that warrant consideration. We acknowledge limitations with our trial being retrospectively registered and study protocol changes occurring subsequent to randomization, including cessation of fetal MRI acquisition due to scheduling difficulties and stricter inclusion cut-off for IUGR early; however, protocol variations occurred while maintaining blinding to accumulating data. In addition to further challenges related to the small sample size and participant attrition, there are difficulties related to measures of metabolite bioavailability65; estimates based on plasma pharmacokinetics may not yield accurate quantitative measures of absorption; however, we attempted to address this by also capturing urinary excretion66, a strength over our earlier trial. We further attempted to address compliance issues through strict PP analyses focusing on metabolite positivity rather than group allocation alone with our results largely consistent across all analyses. We observed group differences in baseline metabolite status suggesting non-random distribution of starting polyphenol levels from non-pomegranate dietary sources65,67,68 such as green tea, chocolate, nuts, berries15; however, we accounted for this in further analysis excluding infants born to mothers positive for metabolites at enrollment; with results again remaining largely unchanged. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that potential bias arising from participant exclusion cannot be excluded in our PP analyses. Another limitation relates to the lack of resting state functional MRI due to clinical scanner time and data quality constraints, so we were unable to further investigate our previously reported functional connectivity findings22. Finally, future trials may benefit from incorporating additional criteria for IUGR diagnosis beyond estimated fetal weight; although in the current study, we used a more conservative cutoff for inclusion (< 5th percentile) than that widely used to ensure infants were truly growth restricted, as evidenced by average birthweights of approximately 2 kg.

Conclusion

In this double-blind, exploratory randomized controlled trial, we present further preliminary findings suggestive of potential in utero neuroprotectant effects of maternal dietary supplementation with pomegranate juice. We report decreased brain injury risk in IUGR infants exposed to pomegranate juice compared with placebo. Importantly, we demonstrate that 8 oz daily of polyphenol-rich pomegranate juice during pregnancy does not increase risk for fetal ductal constriction. Together with our earlier work, these findings warrant continued investigation and suggest secondary studies using advanced quantitative techniques such as cortical surface analysis and non-tensor based diffusion analysis may be needed to better untangle brain structural alterations associated with the observed brain injury differences. Such studies could aid in identifying brain outcome measures that may be more sensitive to the potential neuroprotectant effects of pomegranate juice. Neurodevelopmental follow-up of this cohort is ongoing and will provide further insight into the potential functional correlates and long-term clinical implications of prenatal dietary supplementation with pomegranate juice.

Methods

Trial design and participants

This was a double-blind, exploratory randomized controlled trial of maternal POM consumption during pregnancy, and represents a follow-up to a previously published study22, involving a second population of IUGR pregnancies presenting at a major tertiary hospital in Boston, MA. Study staff screened high risk ultrasound reports of expectant mothers receiving prenatal care at Brigham and Women’s Hospital between October 2015 and March 2020. Due to a period of rapid study staff turnover in the initial stages of study set-up, the trial was inadvertently not prospectively registered, but has since been registered to clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04394910). Initial inclusion criteria were: 1) fetal diagnosis of IUGR < 10th percentile on the Hadlock growth curve69 and at least one of the following: 2) concern over umbilical artery doppler flow for gestational age as per standard clinical Brigham and Women’s Hospital guidelines, 3) reduction in amniotic fluid volume. Following enrollment of the fourth participant, the inclusion criteria were amended to ensure that eligible participants were truly growth restricted, and not simply constitutionally small fetuses11,70,71. The doppler flow and amniotic fluid criteria were also eliminated because these conditions were not routinely clinically reported, resulting in recruitment difficulties. The amended inclusion criteria were: 1) fetal diagnosis of IUGR defined by estimated fetal weight < 5th percentile for gestational age on the Doubilet growth curve72; 2) 24–34 weeks’ gestation based on ultrasound or reliable clinical dating by ACOG standards73. Exclusion criteria were: 1) multiple congenital anomalies; 2) known fetal chromosomal disorder; 3) maternal illicit drug or alcohol intake. Notably, the first four participants enrolled under the initial inclusion criteria fulfilled the updated recruitment criteria. All protocols were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained for all participants.

Enrollment study visits

Maternal blood and urine samples were collected at enrollment to measure baseline metabolite levels. Samples were sent to the University of California, Los Angeles Center for Human Nutrition for liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LCMS/MS) analysis of pomegranate juice metabolites, Urolithin A (UA) and dimethylellagic acid glucuronide (DMEAG). Sociodemographic, health status, and pregnancy information of consented participants were collected by review of the electronic medical record.

The first 31 mothers (34 infants) were recruited as part of a Phase 1 study to assess the effect of high polyphenol intake on fetal ductal constriction, and were scheduled to receive two fetal echocardiograms, the first at enrollment before commencing juice consumption and the second after two weeks of the daily juice regimen.

A subset of participants also received fetal MRI (n = 44) prior to commencing juice consumption to establish baseline brain injury; fetal MRIs were subsequently eliminated due to difficulty in scheduling, and following preliminary analyses revealed no fetal brain injury in any of the participants who underwent fetal MRI prior to starting the allocated juice regimen.

Randomization

Participants were block randomized by random number generator and blinded envelope in a 1:1 ratio to a daily regimen of either 8 oz of 100% pomegranate juice (POM Wonderful, Los Angeles, CA) or a polyphenol-free control beverage matched for color, taste and calorie content. Total polyphenols were determined by the Folin-Ciocalteu method calibrated by a gallic acid standard curve and reported as gallic acid equivalents (GAE)15,74,75. Pomegranate juice (16 ± 0.2° Brix) contained no less than 700 mg GAE per 8 oz serving, and placebo (16 ± 0.2° Brix) contained no more than 38 mg GAE per serving. Juice was distributed as 8 oz bottles labeled A or B; bottles were visually indistinguishable such that the investigative team, participants, and care providers remained blinded to group allocation. Participants were instructed to begin juice consumption on the day of initial study visit, following collection of enrollment blood and urine samples, and first echocardiogram and fetal MRI when applicable, through to delivery.

Follow-up and compliance

Participants were followed up from enrollment until delivery. Juice consumption was tracked in two ways: participants kept a daily diary documenting the number of days of juice consumption, and study staff recorded juice consumption on a weekly basis while delivering juice at regular clinical prenatal appointments. Maternal blood and urine, and cord blood were collected at delivery and analyzed to determine change in polyphenol levels from baseline and to confirm transfer of pomegranate metabolites. Information regarding mode and type of delivery, labor and delivery complications, and neonatal outcomes were recorded from the electronic medical record. Clinically stable infants underwent term equivalent brain MRI. Formal neurodevelopmental follow-up at 18–36 months is currently ongoing.

Image acquisition

Infants were scanned without sedation at 37–41 weeks’ postmenstrual age on a 3 T Siemens Trio scanner (Erlangen, Germany) at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Images included a turbo spin echo T2-weighted sequence (TR/TE 8630/133 ms, FOV = 190 × 190, matrix = 192 × 192, refocusing flip angle = 160°, voxel size 1 × 1 × 1 mm3) and diffusion data obtained using a 2D spin-echo echo-planar-image (EPI) sequence with 30 gradient directions, b value = 1000 s/mm2, 1 b = 0, and spatial resolution 2 × 2 × 2 mm3. Images were interpreted by pediatric neuroradiologists (Drs. Edward Yang and Ellen Grant) and a neonatologist experienced in neuroradiology and brain injury scoring (TEI).

MR image analysis

All term-equivalent MRI analysis was performed blinded to treatment group. Brain injury was scored on T1- and T2- weighted images using the Kidokoro scoring system34, capturing signal abnormality and volume reduction measures in white matter, grey matter, deep grey matter and cerebellum, as well as measures of gyral maturation delay, ventricular dilatation, increased CSF-filled extra-axial space, and intraventricular hemorrhage. Total and regional brain volumes were generated using MANTiS76. Diffusion data was processed using a tensor model. Images were distortion and motion corrected using FSL77. Regions of interest were manually drawn on each brain78 using FSLview (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN) in the bilateral anterior and posterior limbs of the interior capsule (ALIC, PLIC), optic radiations, frontal and occipital lobes, to generate diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) measures of fractional anisotropy (FA), mean (MD), radial (RD) and axial diffusivity (AD). Twenty subjects were excluded from DTI analysis due to processing failure (12 placebo, 8 treatment). Six subjects were excluded from MANTiS analysis due to processing failure (4 placebo, 2 treatment).

Safety assessment

Safety was assessed via review of the electronic medical record for frequency of adverse neonatal outcomes, including neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, respiratory distress, resuscitation at delivery, intraventricular hemorrhage on clinical ultrasound79, sepsis, and necrotizing enterocolitis. Assessors were unaware of study-group allocation. Of the 31 mothers (34 infants) recruited as part of Phase 1 to assess the effect of high polyphenol intake on fetal ductal constriction, 17 completed two fetal echocardiograms according to protocol specifications, revealing no evidence of fetal duct constriction. Of the remaining 17 fetuses who did not receive two fetal echocardiograms, 8 were removed from the study (2 delivered before juice commencement, 1 withdrew due to ductal closure in non-eligible (non-IUGR) co-triplet on first echo before juice commencement, 3 (triplets) withdrew due to maternal migraines triggered by juice, 2 withdrew due to maternal change of mind), 5 completed the first fetal echo but delivered within two weeks of juice consumption, i.e. before the second echo could be performed, and 5 did not undergo either echocardiogram due to scheduling complications.

Outcomes measures

Primary outcomes

Term-equivalent MRI measures of brain structure and injury included total and regional brain volumes, brain injury scoring, and region-of-interest diffusion measures of FA, MD, AD, and RD.

Secondary outcomes

Measures of treatment compliance included time period on juice, number of recorded days of juice consumption, maternal blood and urine metabolite concentrations (enrollment and delivery) and cord blood metabolite concentrations. Safety outcomes included NICU admission, respiratory distress, resuscitation, IVH, sepsis and NEC.

Neurodevelopmental testing is currently ongoing using the Bayley III exam to assess cognitive, gross and fine motor, and language outcomes at 18–36 months; this will form the focus of a subsequent publication.

Measures of placental morphometry and pathology were also collected and will be reported in future secondary analysis of this cohort.

Statistical analysis

Power calculations were based on effect sizes with regard to the primary brain outcome measures of a comparable study in high-risk infant populations, which reported medium to large standardized effect sizes between 0.7–1.380. Accounting for the feasibility of our study, our enrollment of 103 pregnant mothers (n = 47 placebo; n = 56 POM) yields > 90% power based on a two-tailed test of significance (α = 0.05) to detect an effect size of 0.7, and 80% to detect a moderate effect size of 0.56 with 80% power.

Modified intention-to-treat (mITT) analyses were conducted including all participants who received their allocated intervention and who underwent term equivalent brain MRI. This mITT design was necessary given the outcome measures—MRI measures of brain structure and injury—could only be assessed for infants who underwent term-equivalent brain MRI. Per-protocol (PP) analyses were conducted including all participants who received their allocated intervention, underwent term-equivalent brain MRI, and strictly adhered to the protocol based on metabolite status: i.e. comparing brain MRI measures among participants who were randomized to placebo and who were metabolite-negative in maternal blood, urine, and cord blood at delivery (DMEAG and UA = 0 ng/mL), with participants who were randomized to pomegranate juice and who were metabolite-positive (DMEAG and/or UA > 0 ng/mL) in maternal blood, urine, or cord blood at delivery.

Brain injury scores were re-categorized as binary (none vs. ≥ 1) for analysis due to the small number of infants with higher severity scores. Although the clinical importance of mild brain abnormalities still requires further clarification, MRI evidence of mild brain injury has been associated with adverse neurological functioning in the term born infant with mild encephalopathy compared to infants with no brain injury, supporting the premise that MRI-defined injury is a risk factor for subsequent neurodevelopmental challenges81. Furthermore, independent measures from the scoring system used in the current study, including brain metrics, have been shown to be related to neurological outcomes in preterm infants, supporting that even a score if 1–2 from such measures may be of neurodevelopmental significance without other overt brain injury82. Differences in brain injury by study arm were assessed using risk differences and risk ratios. Exact methods were used to calculate risk measures and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals due to small sample sizes. Group differences in brain volumes and DTI measures were analyzed using a median regression approach due to skewed distributions of the outcomes of interest; models were adjusted for intrafamilial correlation among twins, as well as for potential confounding due to postmenstrual age at MRI, infant sex, maternal BMI at enrollment, and small for gestational age (SGA) status83. Differences in compliance and safety measures were evaluated using Wilcoxon rank sum and χ2 tests (or Fisher’s exact tests for small cell counts, n < 5), as appropriate. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C.) and STATA 13.1 (StataCorp, Texas, USA).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Drs. Edward Yang and Ellen Grant for clinical interpretation of MRI images; Susanne Henning, Zhaoping Li and Ru-Po Lee at the UCLA Center for Human Nutrition for performing LCMS/MS analysis; Krittin Supapannachart and Casey Pollard for assistance with brain mask editing; the mothers and infants whose time and efforts allow these scientific insights; and Joseph Volpe, Bronson Crothers Professor of Neurology, Emeritus, for invaluable discussions and insights into mechanisms of neonatal brain injury.

Author contributions

Study conception and design: T.E.I.; Trial coordination, participant recruitment and data collection: D.T., J.R., M.M.R., N.D.M., T.E.I.; Data analysis and interpretation: L.G.M., S.C., T.E.I. Manuscript writing: L.G.M., M.M.R. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Program for Interdisciplinary Neuroscience Award (L.G.M) and an unrestricted gift to Brigham and Women’s Hospital from POM Wonderful, Los Angeles, CA. The sponsors had no role in study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing or revisions of the manuscript, or the decision to publish.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because we had not previously sought IRB approval for public sharing of participant data as part of our informed consent. However, the de-identified minimal raw dataset is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-82144-0.

References

- 1.Kingdom, J. & Smith, G. in Intrauterine Growth Restriction Aetiology and Management (eds J Kingdom & P Baker) 257–273 (Springer, 2000).

- 2.Resnik R. Intrauterine growth restriction. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;99:490–496. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01780-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Intrauterine growth restriction. Practice Bulletin no. 12, Washington DC. http://www.acog.org.

- 4.Suhag A, Berghella V. Intrauterine Growth Restriction (IUGR): Etiology and diagnosis. Curr. Obstet. Gynecol. Rep. 2013;2:102–111. doi: 10.1007/s13669-013-0041-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Beckerath AK, et al. Perinatal complications and long-term neurodevelopmental outcome of infants with intrauterine growth restriction. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lodygensky GA, et al. Intrauterine growth restriction affects the preterm infant's hippocampus. Pediatr. Res. 2008;63:438–443. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318165c005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tolsa CB, et al. Early alteration of structural and functional brain development in premature infants born with intrauterine growth restriction. Pediatr. Res. 2004;56:132–138. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000128983.54614.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colella M, Frérot A, Novais ARB, Baud O. Neonatal and long-term consequences of fetal growth restriction. Curr. Pediatr. Rev. 2018;14:212–218. doi: 10.2174/1573396314666180712114531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levine TA, et al. Early childhood neurodevelopment after intrauterine growth restriction: A systematic review. Pediatrics. 2015;135:126–141. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller SL, Huppi PS, Mallard C. The consequences of fetal growth restriction on brain structure and neurodevelopmental outcome. J. Physiol. 2016;594:807–823. doi: 10.1113/JP271402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McIntire DD, Bloom SL, Casey BM, Leveno KJ. birth weight in relation to morbidity and mortality among newborn infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;340:1234–1238. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904223401603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rees S, Harding R, Walker D. The biological basis of injury and neuroprotection in the fetal and neonatal brain. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2011;29:551–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Folkerth RD, et al. Developmental lag in superoxide dismutases relative to other antioxidant enzymes in premyelinated human telencephalic white matter. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2004;63:990–999. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.9.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma D, Shastri S, Sharma P. Intrauterine growth restriction: Antenatal and postnatal aspects. Clin. Med. Insights Pediatr. 2016;10:67–83. doi: 10.4137/CMPed.S40070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seeram NP, et al. Comparison of antioxidant potency of commonly consumed polyphenol-rich beverages in the United States. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008;56:1415–1422. doi: 10.1021/jf073035s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aquilano K, Baldelli S, Rotilio G, Ciriolo MR. Role of nitric oxide synthases in Parkinson's disease: A review on the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of polyphenols. Neurochem. Res. 2008;33:2416–2426. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9697-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bastianetto S, Krantic S, Quirion R. Polyphenols as potential inhibitors of amyloid aggregation and toxicity: Possible significance to Alzheimer's disease. Min. Rev. Med. Chem. 2008;8:429–435. doi: 10.2174/138955708784223512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esmaillzadeh A, Tahbaz F, Gaieni I, Alavi-Majd H, Azadbakht L. Cholesterol-lowering effect of concentrated pomegranate juice consumption in type II diabetic patients with hyperlipidemia. Int. J. Vitamin Nutr. Res. 2006;76:147–151. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.76.3.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong MY, Seeram NP, Heber D. Pomegranate polyphenols down-regulate expression of androgen-synthesizing genes in human prostate cancer cells overexpressing the androgen receptor. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2008;19:848–855. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mokni M, et al. Resveratrol provides cardioprotection after ischemia/reperfusion injury via modulation of antioxidant enzyme activities. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. IJPR. 2013;12:867–875. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shema-Didi L, et al. One year of pomegranate juice intake decreases oxidative stress, inflammation, and incidence of infections in hemodialysis patients: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2012;53:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matthews LG, et al. Maternal pomegranate juice intake and brain structure and function in infants with intrauterine growth restriction: A randomized controlled pilot study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0219596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braidy N, et al. Consumption of pomegranates improves synaptic function in a transgenic mice model of Alzheimer's disease. Oncotarget. 2016;7:64589–64604. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kujawska M, et al. Neuroprotective effects of pomegranate juice against parkinson's disease and presence of Ellagitannins-derived metabolite-Urolithin A-in the brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020 doi: 10.3390/ijms21010202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ritz MF, et al. Chronic treatment with red wine polyphenol compounds mediates neuroprotection in a rat model of ischemic cerebral stroke. J. Nutr. 2008;138:519–525. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.3.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loren DJ, Seeram NP, Schulman RN, Holtzman DM. Maternal dietary supplementation with pomegranate juice is neuroprotective in an animal model of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Pediatr. Res. 2005;57:858–864. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000157722.07810.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.West T, Atzeva M, Holtzman DM. Pomegranate polyphenols and resveratrol protect the neonatal brain against hypoxic-ischemic injury. Dev. Neuroscience. 2007;29:363–372. doi: 10.1159/000105477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bellone JA, et al. Pomegranate supplementation improves cognitive and functional recovery following ischemic stroke: A randomized trial. Nutr. Neurosci. 2019;22:738–743. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2018.1436413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bookheimer SY, et al. Pomegranate juice augments memory and FMRI activity in middle-aged and older adults with mild memory complaints. Evid. Based Complement Altern. Med. 2013;2013:946298. doi: 10.1155/2013/946298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siddarth P, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled study of the memory effects of pomegranate juice in middle-aged and older adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020;111:170–177. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqz241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bubols GB, et al. Nitric oxide and reactive species are modulated in the polyphenol-induced ductus arteriosus constriction in pregnant sheep. Prenat. Diagn. 2013;34:1268–1276. doi: 10.1002/pd.4463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zielinsky P, et al. Maternal restriction of polyphenols and fetal ductal dynamics in normal pregnancy: An open clinical trial. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2013;101:217–225. doi: 10.5935/abc.20130166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zielinsky P, Busato S. Prenatal effects of maternal consumption of polyphenol-rich foods in late pregnancy upon fetal ductus arteriosus. Birth Defects Res. 2013;99:256–274. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.21051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kidokoro H, Neil JJ, Inder TE. New MR imaging assessment tool to define brain abnormalities in very preterm infants at term. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2013;34:2208–2214. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ginsberg Y, et al. Maternal pomegranate juice attenuates maternal inflammation-induced fetal brain injury by inhibition of apoptosis, neuronal nitric oxide synthase, and NF-kappaB in a rat model. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018;219(113):e111–113.e119. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Casedas G, Les F, Choya-Foces C, Hugo M, Lopez V. The metabolite urolithin-A ameliorates oxidative stress in neuro-2a cells, becoming a potential neuroprotective agent. Antioxidants (Basel). 2020 doi: 10.3390/antiox9020177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen B, Longtine MS, Riley JK, Nelson DM. Antenatal pomegranate juice rescues hypoxia-induced fetal growth restriction in pregnant mice while reducing placental cell stress and apoptosis. Placenta. 2018;66:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2018.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tuuli MG, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of maternal antenatal pomegranate juice (POM) ingestion and POM effects on placental morphology and function in women diagnosed antenatally with intrauterine growth restriction. Trends Dev. Biol. 2019;12:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Back SA. Cerebral white and gray matter injury in newborns: New insights into pathophysiology and management. Clin. Perinatol. 2014;41:1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reich B, Hoeber D, Bendix I, Felderhoff-Mueser U. Hyperoxia and the Immature Brain. Dev Neurosci. 2016;38:311–330. doi: 10.1159/000454917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McQuillen PS, Sheldon RA, Shatz CJ, Ferriero DM. Selective vulnerability of subplate neurons after early neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:3308. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03308.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Esteban FJ, et al. Fractal-dimension analysis detects cerebral changes in preterm infants with and without intrauterine growth restriction. Neuroimage. 2010;53:1225–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Padilla N, et al. Differential effects of intrauterine growth restriction on brain structure and development in preterm infants: A magnetic resonance imaging study. Brain Res. 2011;1382:98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Back SA. White matter injury in the preterm infant: Pathology and mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;134:331–349. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1718-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Volpe JJ. Brain injury in premature infants: A complex amalgam of destructive and developmental disturbances. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:110–124. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(08)70294-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davidson JO, et al. Perinatal brain injury: Mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 2018;23:2204–2226. doi: 10.2741/4700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Volpe JJ. Dysmaturation of premature brain: Importance, cellular mechanisms, and potential interventions. Pediatr. Neurol. 2019;95:42–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2019.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matthews LG, et al. Brain growth in the NICU: Critical periods of tissue-specific expansion. Pediatr. Res. 2018;83:976–981. doi: 10.1038/pr.2018.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bystron I, Blakemore C, Rakic P. Development of the human cerebral cortex: Boulder Committee revisited. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008;9:110–122. doi: 10.1038/nrn2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ball G, et al. Development of cortical microstructure in the preterm human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:9541–9546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301652110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hüppi PS, et al. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging of brain development in premature and mature newborns. Ann. Neurol. 1998;43:224–235. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kapellou O, et al. Abnormal cortical development after premature birth shown by altered allometric scaling of brain growth. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e265–e265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dubois J, et al. Primary cortical folding in the human newborn: An early marker of later functional development. Brain. 2008;131:2028–2041. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Samuelsen GB, et al. Severe cell reduction in the future brain cortex in human growth-restricted fetuses and infants. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007;197(56):e51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chun JJ, Nakamura MJ, Shatz CJ. Transient cells of the developing mammalian telencephalon are peptide-immunoreactive neurons. Nature. 1987;325:617–620. doi: 10.1038/325617a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Friauf E, Shatz CJ. Changing patterns of synaptic input to subplate and cortical plate during development of visual cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 1991;66:2059–2071. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.6.2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhao C, Kao JP, Kanold PO. Functional excitatory microcircuits in neonatal cortex connect thalamus and layer 4. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:15479–15488. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4471-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.59Kinney, H. C. & Volpe, J. J. in Volpe’s Neurology of the Newborn (eds J. J. Volpe et al.) Ch. 7, (Elsevier, 2018).

- 59.Sheikh A, et al. Neonatal hypoxia-ischemia causes functional circuit changes in subplate neurons. Cereb. Cortex. 2019;29:765–776. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhx358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kostovic I, Rakic P. Developmental history of the transient subplate zone in the visual and somatosensory cortex of the macaque monkey and human brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 1990;297:441–470. doi: 10.1002/cne.902970309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meinecke DL, Rakic P. Expression of GABA and GABAA receptors by neurons of the subplate zone in developing primate occipital cortex: Evidence for transient local circuits. J. Comp. Neurol. 1992;317:91–101. doi: 10.1002/cne.903170107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Allendoerfer KL, Shatz CJ. The subplate, a transient neocortical structure: its role in the development of connections between thalamus and cortex. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1994;17:185–218. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.001153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu G, et al. Late development of the GABAergic system in the human cerebral cortex and white matter. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2011;70:841–858. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31822f471c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Finn-Sell SL, et al. Pomegranate juice supplementation alters utero-placental vascular function and fetal growth in the eNOS(-/-) mouse model of fetal growth restriction. Front. Physiol. 2018;9:1145–1145. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Panickar KS, Anderson RA. Effect of polyphenols on oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in neuronal death and brain edema in cerebral ischemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011;12:8181–8207. doi: 10.3390/ijms12118181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Seeram NP, et al. Pomegranate juice ellagitannin metabolites are present in human plasma and some persist in urine for up to 48 hours. J. Nutr. 2006;136:2481–2485. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.10.2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hammerstone JF, Lazarus SA, Schmitz HH. Procyanidin content and variation in some commonly consumed foods. J. Nutr. 2000;130:2086s–2092s. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.8.2086S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lacroix S, et al. A computationally driven analysis of the polyphenol-protein interactome. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:2232. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20625-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hadlock FP, Harrist RB, Martinez-Poyer J. In utero analysis of fetal growth: A sonographic weight standard. Radiology. 1991;181:129–133. doi: 10.1148/radiology.181.1.1887021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McCormick MC. The contribution of low birth weight to infant mortality and childhood morbidity. N. Engl. J. Med. 1985;312:82–90. doi: 10.1056/nejm198501103120204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Peleg D, Kennedy CM, Hunter SK. Intrauterine growth restriction: Identification and management. Am. Fam. Phys. 1998;58(453–460):466–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Doubilet PM, Benson CB, Nadel AS, Ringer SA. Improved birth weight table for neonates developed from gestations dated by early ultrasonography. J. Ultrasound Med. 1997;16:241–249. doi: 10.7863/jum.1997.16.4.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gynecologists AC. ACOG practice bulletin no. 134: Fetal growth restriction. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;121:1122–1133. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000429658.85846.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ben Nasr C, Ayed N, Metche M. Quantitative determination of the polyphenolic content of pomegranate peel. Zeitschrift fur Lebensmittel-Untersuchung und -Forschung. 1996;203:374–378. doi: 10.1007/BF01231077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Singleton VL, Rossi JA. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965;16:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Beare RJ, et al. Neonatal brain tissue classification with morphological adaptation and unified segmentation. Front. Neuroinf. 2016;10:12. doi: 10.3389/fninf.2016.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Smith SM, et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. NeuroImage. 2004;23:S208–S219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rogers CE, et al. Regional white matter development in very preterm infants: Perinatal predictors and early developmental outcomes. Pediatr. Res. 2016;79:87–95. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: A study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. J. Pediatr. 1978;92:529–534. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(78)80282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Inder TE, Warfield SK, Wang H, Huppi PS, Volpe JJ. Abnormal cerebral structure is present at term in premature infants. Pediatrics. 2005;115:286–294. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rao R, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in neonates with mild hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy treated with therapeutic hypothermia. Am. J. Perinatol. 2019;36:1337–1343. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hammerl M, et al. Supratentorial brain metrics predict neurodevelopmental outcome in very preterm infants without brain injury at age 2 years. Neonatology. 2020;117:287–293. doi: 10.1159/000506836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Olsen IE, Groveman SA, Lawson ML, Clark RH, Zemel BS. New intrauterine growth curves based on United States data. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e214–224. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because we had not previously sought IRB approval for public sharing of participant data as part of our informed consent. However, the de-identified minimal raw dataset is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.