Abstract

Introduction:

This study aimed to evaluate the 3-dimensional (3D) mandibular dental changes over 42 years using the registration of digital models.

Methods:

The sample comprised digital dental models of 8 untreated subjects (4 males and 4 females) with normal occlusion measured longitudinally at ages 17 years (T1) and 60 years (T2). Using 13 landmarks placed on the mucogingival junction, we registered the T2 model on the T1 model. Three-dimensional changes in the position of the landmarks on the buccal cusp tip of the posterior teeth and incisal edge of the central incisors were measured by 2 examiners. Registration and measurements were performed using SlicerCMF (version 3.1; http://www.slicer.org) software. Intra- and interrater agreements were evaluated using intraclass correlation coefficients and the Bland-Altman method. One-sample t tests were used for evaluating interphase 3D dental changes (P<0.05).

Results:

Adequate intra- and interrater reproducibility was found. From T1 to T2, the mandibular teeth showed significant 3D positional changes. A significant dental eruption relative to the mucogingival junction was observed for the anterior and posterior teeth. Anteroposterior movements of mandibular teeth were not significant except for the right molar that drifted mesially. Transverse movements included slight lingual tipping at canines and premolars regions.

Conclusions:

Dental changes in untreated normal occlusion were very slight from early to mature adulthood. The eruption of the mandibular teeth was the most consistent finding. A tendency for mesial movement of molars and lingual movement of first premolars and canines was observed in the mandible during the aging process.

Skeletal and dentoalveolar changes during the growth of the face are continuous processes occurring throughout life.1,2 Maturational changes take place both in the maxillary and mandibular dental arches.1,3,4 Mandibular arch changes are of particular interest to the orthodontist because of the frequent occurrence of late incisor crowding,3,4 a common complaint of patients long after orthodontic treatment has been completed.

There have been several previous studies that have evaluated long-term changes in the dentition of untreated subjects. Sinclair and Little5 found a significant decrease in mandibular arch length, intercanine width, and intermolar width in a sample of 65 untreated subjects evaluated in the mixed, early permanent dentition, and early adulthood. A significant increase in the mandibular incisor irregularity was observed in the permanent dentition period.5

Bishara et al6 evaluated dental models derived from a sample with normal occlusion at ages 25 years and 46 years. A significant decrease in mandibular intercanine width and arch length was found.6 In addition, significant mandibular dental crowding took place during the 20 years of follow-up.6 Carter and McNamara Jr7 examined an untreated sample of subjects aged from 16 years to 48 years. A significant decrease in arch width, arch depth, and arch perimeter was found for the mandibular arch.7 Mandibular incisor irregularities showed a significant increase of 1.4 mm over a 30-year follow-up.7

Thilander8 analyzed a sample of subjects with normal occlusion, aged from 5 years to 31 years. A decrease of 4 mm in the arch perimeter was found in the mandible.8 After the age of 16 years, a continuous decrease in intercanine width was found in the mandibular arch, resulting in anterior crowding, especially in the mandible.8 Tsiopas et al9 evaluated dental models of untreated Swedish dentists from the ages of 20 years to 60 years. The authors found a significant increase in the irregularity index of Little10 in the mandibular arch and a decrease of arch length and intercanine distance in both dental arches.9

Miranda et al4 examined dental models of subjects between the ages of 13 years and 62 years with normal occlusion. The authors found significant mandibular incisor crowding occurring only in subjects without permanent tooth loss.4 Massaro et al3 evaluated the maturational changes in normal occlusion subjects throughout 40 years. Intercanine width and arch perimeter decreased from 18 to 60 years.3 Incisor crowding was found only in the mandible.3 The authors suggested that future studies with dental model superimpositions were necessary to elucidate if the decrease in intercanine width occurs because of mesial or lingual canine displacements.

The superimposition of digital dental models enables quantification and visual analysis of 3-dimensional (3D) tooth movements and arch changes over time.11 To achieve this goal, accurate registration of digital models from different time points using reliable reference areas is required. Previous studies on the superimposition of digital dental models for tooth movement analysis were limited to the maxillary arch, primarily using the palatal rugae as reference.12–15 Considering the technological development, a search for stable areas or points of reference for the mandibular dental arch was needed.

Park et al16 proposed a method of mandibular dental model superimposition based on cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) surface registration of the mandible in nongrowing patients. First, CBCT images of digital models were superimposed at corresponding time points using the best-fit method. Subsequently, the CBCT images were superimposed at the mandibular basal bone and posterior ramus regions. After deleting the tooth images from the CBCT, landmarks were assigned to digital dental models allowing reproducible measurements of 3D dental changes.16

An et al17 evaluated 4 regions of interest on the mandibular alveolar ridge and reported that the mandibular tori were stable areas for the superimposition of the digital dental model. The authors found that the horizontal and vertical movements of the central incisors and first molars measured on the superimposed models were similar to 2-dimensional cephalometric changes.17

More recently, Schmidt et al18 developed a method for dental model superimposition combining local rigid tooth surface registration with a nonimage based method driven by biomechanical models. The authors reported that their methods were applicable to both maxilla and mandible for orthodontic tooth movement analysis and that growth-related changes are ignored.18 Ioshida et al19 validated the mucogingival junction as a reference for mandibular digital dental model registration in a short-term assessment of 48 weeks. Voxel-based registration of mandibular CBCT images was compared with registered dental models on the mucogingival junction, and no significant differences were found.19

Although several studies1–7 have investigated the maturational process in the mandibular arch using dental casts, the 3D direction of mandibular teeth movements that occur with aging, and affect the stability of orthodontic correction, require further investigation. The superimposition of digital models could potentially elucidate the individual teeth movement over time. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the 3D mandibular dental changes during aging using the registration of digital models on the mucogingival junction. Maturational mandibular tooth movement from ages 17 years to 60 years was measured 3-dimensionally in normal occlusion subjects.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This study was approved by the institutional research ethical committee of Bauru Dental School, University of São Paulo (Process no. 43931915.4.0000.5417).

Written patient consent forms were obtained. Sample size calculation considered a test power of 80%, an alpha error of 5%, a minimum difference of 1 mm to be detected, and a standard deviation of 0.8 mm derived from preliminary statistics. A sample of 7 patients was necessary.

The sample of this study consisted of dental models of untreated subjects with normal occlusion. The original sample was composed of 82 white subjects, recruited in the 1960s and 1970s. Dental models obtained at age 17 years (T1) were used. All subjects were recalled in 2015 and 2016 (T2). From the initial sample, 38 subjects could be contacted, 36 could not be found, and 8 had died. Eleven subjects did not agree to return at T2. Twenty-seven subjects initially were enrolled in the sample.

The exclusion criteria included a history of previous orthodontic treatment, tooth loss of any tooth mesial to second molars from T1 to T2, absence of prosthetic rehabilitation, and inadequate dental models. From the subjects enrolled, 3 had inadequate T1 study models, and 16 subjects were excluded because of tooth loss and prosthetic rehabilitation at T2. The final sample consisted of 8 subjects with normal occlusion (4 males and 4 females).

The dental models taken at ages 17 years and 60 years were scanned using an R700 3D Scanner (3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark). The maxillary and mandibular dental models were scanned and stored as Stereolithography files (.STL) were converted to visualization toolkit (.VTK) mesh files, using SlicerCMF (version 3.1; http://www.slicer.org). Registration and measurements consisted of the following steps:

Model orientation: The maxillary and mandibular T1 dental models were oriented in centric occlusion using the 3D coordinate system in the transforms tool of SlicerCMF software. Using the maxillary occlusal perspective, we positioned the midpalatal raphe coincident with the anteroposterior yellow line (sagittal plane). In the same view, the second palatal rugae was moved to coincide with the superior-inferior green line (coronal plane). In the right-side view, the occlusal plane, defined by a line passing through the maxillary first molar mesiobuccal cusp tip and maxillary canine cusp tip, was placed on the right-left red line (axial plane). On the model’s frontal view, the cusp tips of the right and left canines were positioned on the red line (axial plane). After orientation, the maxillary dental model was eliminated, and all the following steps were performed only on the mandibular dental models.

Model approximation: Model approximation was conducted in 2 steps. First, the T2 mandibular dental model was approximated to the T1 model by placing 6 corresponding landmarks in the T2 and T1 3D digital dental models using the CMF registration module in SlicerCMF. The landmarks were placed on the tip of the mesiobuccal cusp of the first molar, the buccal cusp of the first premolar and the canine. All landmarks were placed bilaterally. The Q3DC module of the SlicerCMF software displayed the x-, y-, and z-coordinates for each landmark. Using the x-, y-, and z-coordinates of T1 as a reference, the software changed the spatial position of T2 to match the T1 coordinates. As a result, the T2 and T1 mandibular models were approximated by the superimposition of the corresponding landmarks facilitating the next step. The second step consisted of manual approximation of the mucogingival junction of the T2 mandibular model to the mucogingival junction of the T1 model.

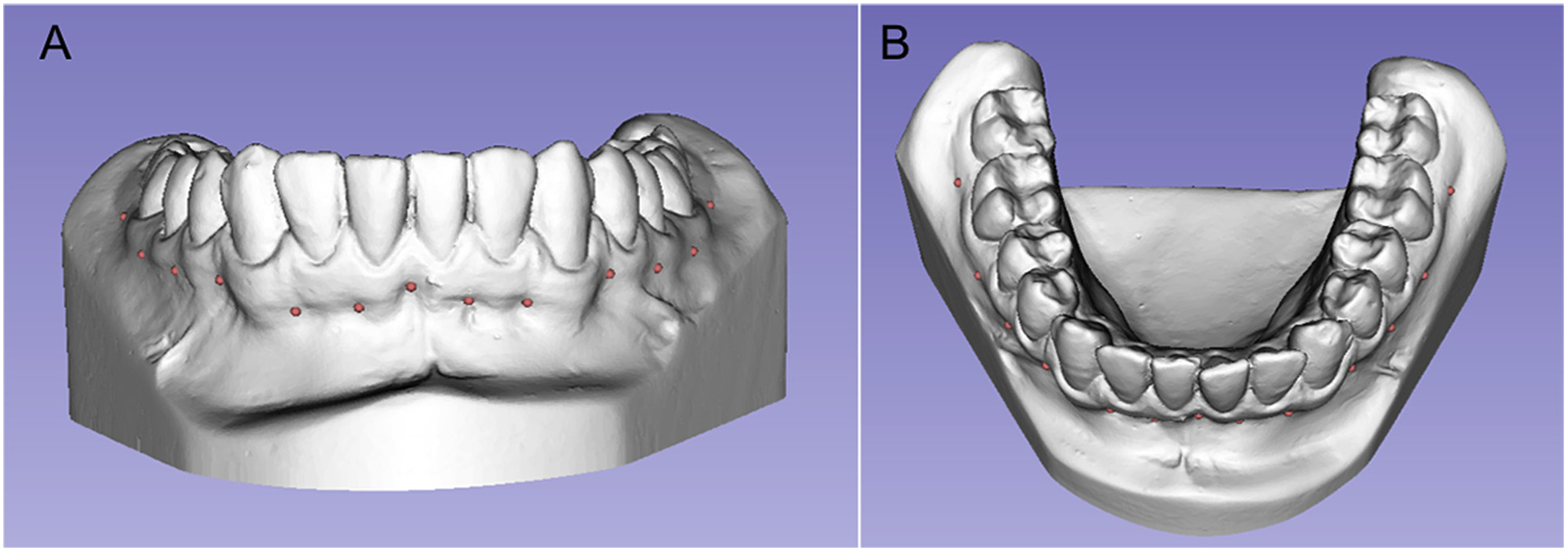

Registration: On both T1 and T2 mandibular models, 13 landmarks were placed on the mucogingival junction between each permanent tooth from the distal aspect of the mandibular right first molars to the distal aspect of the left homologous tooth (Fig 1). Using the CMF registration module in SlicerCMF, the T2 mandibular model was registered relative to the T1 model by matching the coordinates of the corresponding landmarks. The software automatically calculated the best fit for the simultaneous superimposition of the corresponding landmarks.

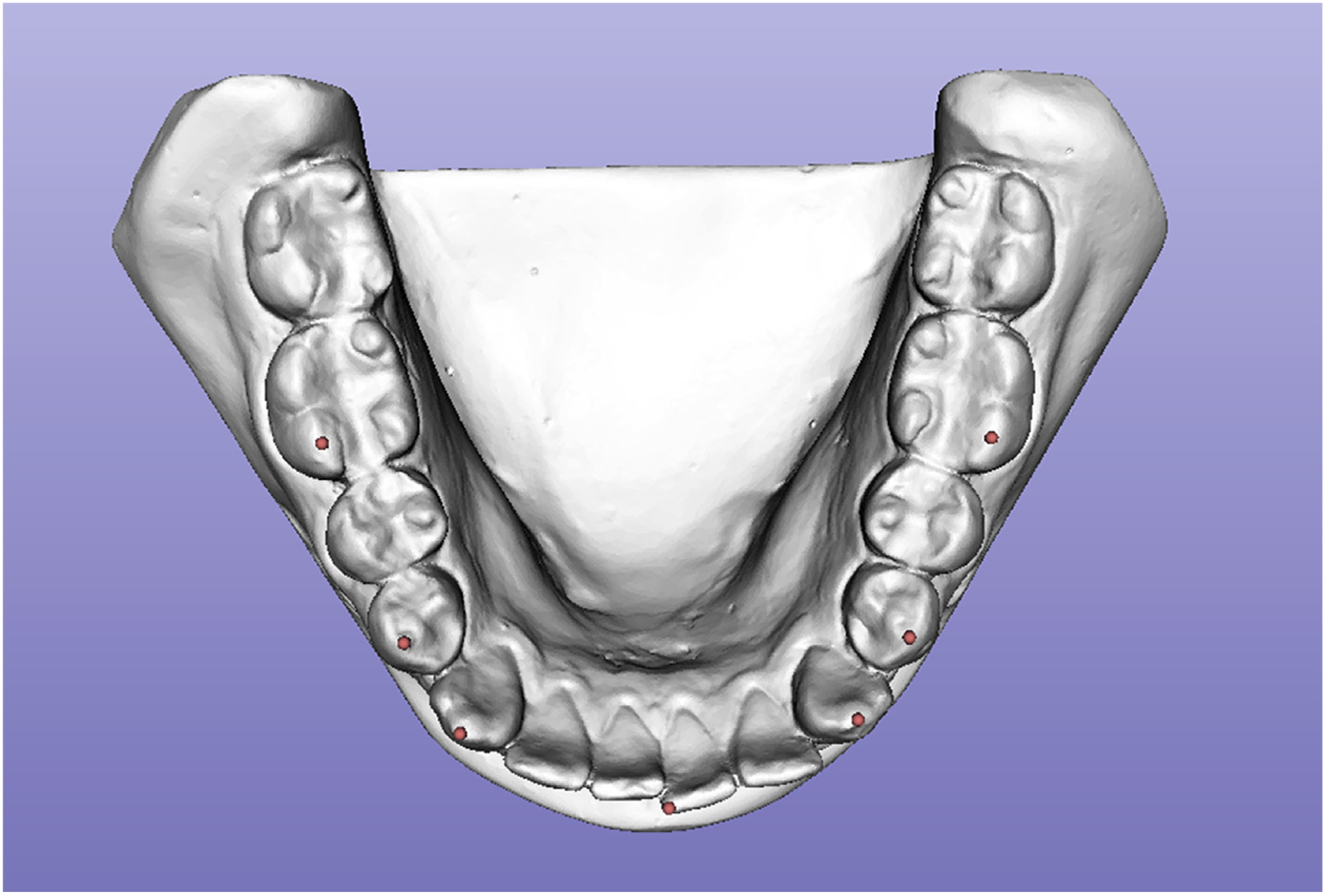

Three-dimensional measurements: Using the Q3DC module of the SlicerCMF software, we placed the landmarks on T1 and on the registered T2 models at the tip of the mesiobuccal cusp of the first molars, buccal cusp of the first premolars and canines, bilaterally, and on the mesial angle of the incisal edge of the left central incisor (Fig 2). Visualization of the occlusal view of the 2 time points of each pair of mandibular models was available, side-by-side on the screen while placing the dental landmarks. Differences between T1 to T2 were measured considering the complete 3D displacement and the changes in x-, y-, and z-coordinates. Anterior, superior, and lateral displacements had positive values. Posterior, inferior, and medial displacements had negative values.

Fig 1.

Thirteen landmarks were used for registration on the mucogingival junction.

Fig 2.

Landmarks used for 3D quantitative measurements.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS (version 21.0; SPSS, Chicago, Ill). Steps 1 to 4 were performed by 2 examiners (D.G and F.M). The first examiner repeated the steps twice with a 15-day interval. Descriptive statistics included the mean and standard deviation of 3D tooth displacements from T1 to T2, comprising a 42-year interval. Intra- and interrater agreements were calculated using a 1-way random intraclass correlation coefficient and Bland-Altman plot.20 Intraclass correlation coefficient values from 0.75 to 1, from 0.6 to 0.74, from 0.4 to 0.59, and less than 0.4 were considered excellent, good, fair, and poor agreements, respectively.21 A 1-sample t test was used for evaluating interphase 3D dental changes (P<0.05).

RESULTS

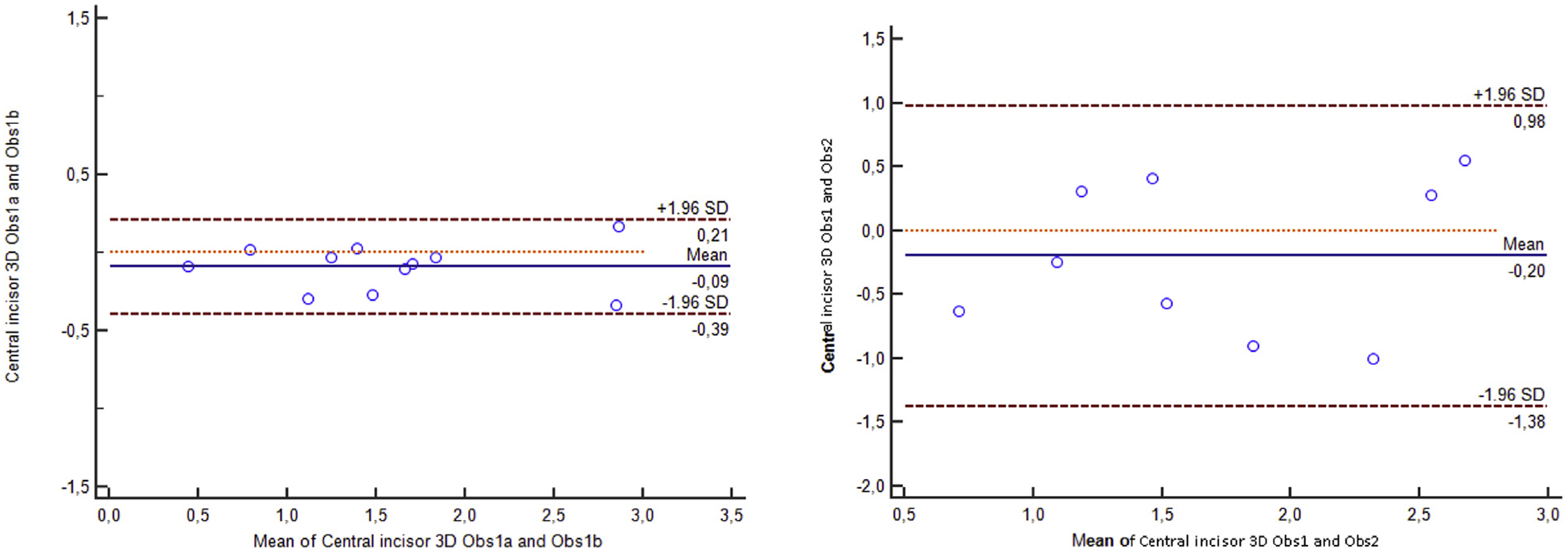

The intra- and interrater agreements and 3D dental movements are summarized in Table and Figure 3.

Table.

Three-dimensional dental changes (1-sample t tests) from ages 17 years to 60 years and intra- and interrater agreements (intraclass correlation coefficient and Bland-Altman)

| 3D changes (mm) | Intrarater differences (Bland-Altman) | Interrater differences (Bland-Altman) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tooth | Measurement | Mean | SD | P | Intrarater agreement ICC | Interrater agreement ICC | Mean | SD | LL | UL | Mean | SD | LL | UL |

| Right first molar | R-L | −0.11 | 0.80 | 0.72 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.33 | −0.60 | 0.70 | −0.04 | 0.56 | −1.14 | 1.06 |

| A-P | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.03* | 0.93 | 0.87 | 0.17 | 0.43 | −0.67 | 1.01 | 0.40 | 0.83 | −1.24 | 2.03 | |

| S-I | 0.87 | 0.67 | 0.01* | 0.92 | 0.55 | −0.06 | 0.42 | −0.89 | 0.77 | 0.20 | 0.91 | −1.59 | 2.00 | |

| 3D | 1.71 | 0.43 | 0.00* | 0.76 | 0.44 | 0.05 | 0.47 | −0.86 | 0.97 | 0.36 | 1.00 | −1.60 | 2.32 | |

| Right first premolar | R-L | −0.58 | 0.54 | 0.01* | 0.93 | 0.74 | 0.12 | 0.20 | −0.27 | 0.51 | 0.01 | 0.59 | −1.15 | 1.16 |

| A-P | 0.26 | 0.94 | 0.44 | 0.97 | 0.85 | 0.05 | 0.21 | −0.37 | 0.46 | −0.02 | 0.54 | −1.08 | 1.04 | |

| S-I | 0.82 | 0.71 | 0.01* | 0.77 | 0.73 | −0.10 | 0.51 | −1.10 | 0.91 | 0.21 | 0.54 | −0.85 | 1.26 | |

| 3D | 1.49 | 0.64 | 0.00* | 0.86 | 0.39 | −0.07 | 0.34 | −0.73 | 0.59 | −0.04 | 0.77 | −1.55 | 1.47 | |

| Right canine | R-L | −0.73 | 0.69 | 0.01* | 0.95 | 0.90 | −0.12 | 0.18 | −0.46 | 0.23 | −0.02 | 0.38 | −0.77 | 0.73 |

| A-P | −0.41 | 1.39 | 0.42 | 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.02 | 0.34 | −0.65 | 0.70 | −0.04 | 0.58 | −1.17 | 1.10 | |

| S-I | 0.93 | 1.02 | 0.03* | 0.89 | 0.84 | −0.05 | 0.45 | −0.93 | 0.83 | 0.19 | 0.53 | −0.85 | 1.23 | |

| 3D | 1.94 | 0.95 | 0.00* | 0.96 | 0.82 | 0.09 | 0.24 | −0.38 | 0.57 | 0.25 | 0.53 | −0.78 | 1.28 | |

| Central incisor | R-L | −0.20 | 0.22 | 0.03* | 0.84 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.18 | −0.36 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.38 | −0.63 | 0.87 |

| A-P | −0.81 | 1.15 | 0.08 | 0.94 | 0.76 | 0.04 | 0.36 | −0.67 | 0.75 | 0.17 | 0.74 | −1.28 | 1.62 | |

| S-I | 1.02 | 0.97 | 0.02* | 0.93 | 0.74 | 0.08 | 0.37 | −0.65 | 0.80 | 0.51 | 0.71 | −0.89 | 1.90 | |

| 3D | 1.77 | 0.85 | 0.00* | 0.97 | 0.68 | −0.10 | 0.17 | −0.43 | 0.23 | −0.20 | 0.60 | −1.38 | 0.98 | |

| Left canine | R-L | −0.32 | 0.52 | 0.12 | 0.89 | 0.52 | −0.08 | 0.27 | −0.61 | 0.45 | 0.23 | 0.61 | −0.97 | 1.43 |

| A-P | −0.53 | 1.16 | 0.23 | 0.97 | 0.85 | −0.03 | 0.26 | −0.55 | 0.48 | 0.04 | 0.61 | −1.15 | 1.23 | |

| S-I | 0.99 | 0.86 | 0.01* | 0.91 | 0.70 | 0.16 | 0.34 | −0.51 | 0.83 | 0.52 | 0.66 | −0.78 | 1.82 | |

| 3D | 1.69 | 0.81 | 0.00* | 0.92 | 0.72 | 0.04 | 0.32 | −0.60 | 0.67 | −0.01 | 0.60 | −1.19 | 1.17 | |

| Left first premolar | R-L | −0.39 | 0.63 | 0.11 | 0.92 | 0.58 | −0.05 | 0.22 | −0.48 | 0.39 | 0.29 | 0.37 | −0.44 | 1.03 |

| A-P | 0.10 | 0.63 | 0.71 | 0.90 | 0.76 | −0.05 | 0.34 | −0.73 | 0.62 | 0.18 | 0.61 | −1.02 | 1.37 | |

| S-I | 1.04 | 0.62 | 0.00* | 0.88 | 0.64 | 0.17 | 0.24 | −0.29 | 0.64 | 0.56 | 0.39 | −0.22 | 1.33 | |

| 3D | 1.42 | 0.69 | 0.00* | 0.94 | 0.84 | 0.07 | 0.22 | −0.35 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.35 | −0.49 | 0.89 | |

| Left first molar | R-L | −0.24 | 0.87 | 0.45 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.15 | 0.30 | −0.43 | 0.73 | −0.04 | 0.39 | −0.80 | 0.72 |

| A-P | 0.54 | 0.79 | 0.09 | 0.90 | 0.78 | −0.09 | 0.39 | −0.86 | 0.69 | 0.25 | 0.61 | −0.95 | 1.45 | |

| S-I | 1.19 | 0.93 | 0.00* | 0.94 | 0.75 | 0.13 | 0.34 | −0.54 | 0.80 | 0.56 | 0.58 | −0.58 | 1.70 | |

| 3D | 1.82 | 0.70 | 0.00* | 0.91 | 0.46 | −0.05 | 0.29 | −0.61 | 0.52 | 0.02 | 0.72 | −1.40 | 1.43 | |

SD, Standard deviation; LL, lower limit; UL, upper limit; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; R-L, right-left plane; A-P, anteroposterior plane; S-I, superoinferior plane.

Statistically significant at P<0.05.

Fig 3.

Bland-Altman plots displays the confidence intervals for the intra- and interexaminers agreement for the central incisors.

Measurements demonstrated excellent intrarater agreements with mean errors smaller than 0.17 mm (the largest mean intrarater error was found for the anteroposterior movement of the right first molar: 0.17 ± 0.43 mm). Interrater agreements showed adequate results with mean errors smaller than 0.56 mm (the largest mean interrater error was found for the superoinferior movement of the left first molar: 0.56 ± 0.58 mm).

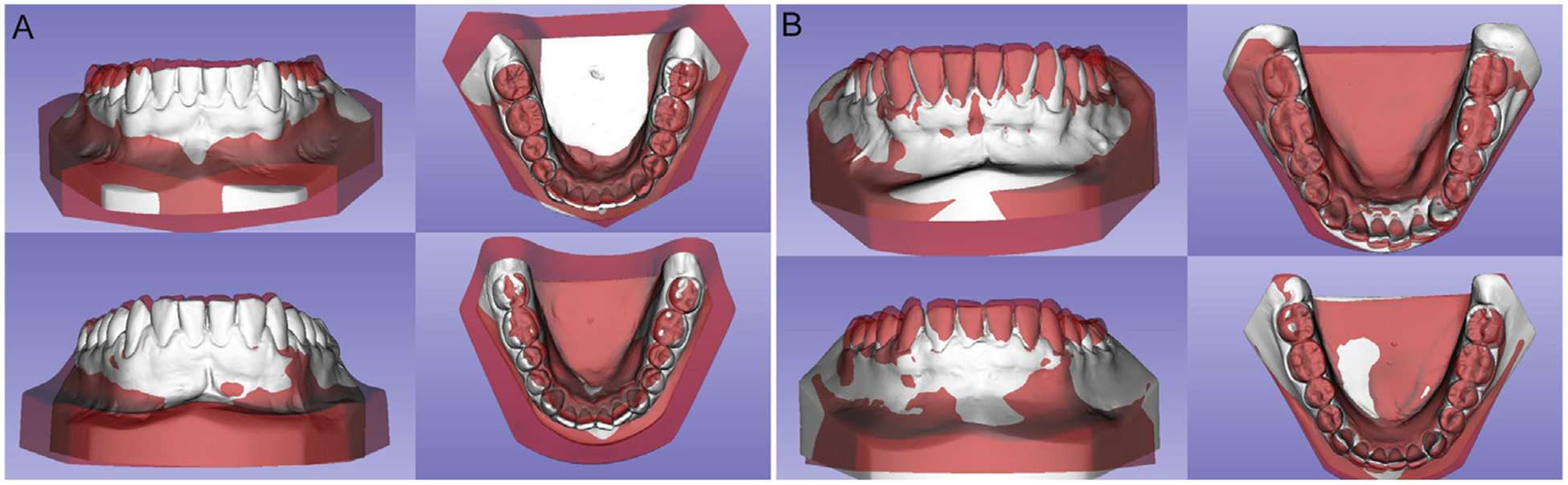

Three-dimensional dental changes demonstrated the tooth movements from ages 17 years to 60 years. The mean 3D positional changes of mandibular teeth varied from 1.42 to 1.94 mm. The anteroposterior, vertical, and transverse components of such 3D displacements revealed larger vertical changes that were greater than anteroposterior or transverse dental movements for all teeth that were assessed. Dental eruption relative to the mucogingival junction was statistically significant for all anterior and posterior teeth (Fig 4). The mesial shift of molars was observed on both right and left sides; a mesial shift was statistically significant on the right side only. The first premolar and canines moved slightly lingually; this displacement was statistically significant on the right side. The central incisor shifted slightly but statistically significantly (−0.20 ± 0.22 mm) toward the midline. Individual changes are demonstrated in Figure 5.

Fig 4.

Frontal and occlusal views of T2 models registered on T1 model: A, two males from the sample; B, two females from the sample.

Fig 5.

Individual tooth changes for females (red bars) and males (blue bars) in right-left (R-L), anteroposterior (A-P), superoinferior (S-I), and 3D displacements: A, central incisors; B, left canines; C, left first premolars; D, left first molars.

DISCUSSION

Registration of mandibular dental models using the mucogingival junction as reference demonstrated an adequate intra- and interexaminer reproducibility.

The mucogingival junction seems to remain stable throughout adulthood.22 A previous short-term study using superimposition between CBCT and digital dental models showed that the mandibular digital model registration on the mucogingival junction is accurate and reliable.19

The advantages of using dental model registration instead of CBCT registration for evaluating 3D dental changes are the higher resolution of dental crown surfaces for precise measurements and the smaller risk of cumulative radiation exposure.23 Furthermore, normal occlusion subjects could not be studied using CBCT for ethical reasons.23

Aging of the occlusion is not a static process. Previous studies reported that normal occlusion subjects demonstrate a decrease in arch length and perimeter during the maturational process.3,5–7 In the mandibular arch, intercanine width decreases, whereas incisor crowding increases from adolescence to late adulthood.3,5–7 How individual 3D tooth movements contribute to the abovementioned arch changes has not been elucidated previously. Registration of the mandibular models quantitatively and visually showed that the mandibular teeth moved from ages 17 years to 60 years (Table; Fig 3). The mean observed 3D dental changes were highly statistically significant (P<0.000) for all teeth (Table).

Superoinferior dental displacements were the most prevalent of the directional components of the 3D displacements for all teeth. Tooth eruption relative to the mucogingival junction was statistically significant for all teeth bilaterally. The mean eruption of the mandibular teeth varied from 0.82 to 1.19 mm. These results are in agreement with previous studies.1,24 Behrents1 reported vertical drift of mandibular incisors and molars relative to the mandibular plane in adult males and females. West and McNamara Jr24 found mandibular incisor eruption of 1.6 mm and molar extrusion of 1.8 mm in untreated subjects from the ages of 17 years to 47 years.

The amount of dental vertical drift measured in registered dental models was smaller than that measured cephalometrically. Possible explanations for these differences are several. First, digital dental model registration on the mucogingival junction is sensitive to only tooth eruption while tooth eruption and bone apposition on the mandibular base are cephalometrically measured.1,2 Second, cephalometric findings are not directly comparable to the findings of the current study because of the overlap of all 3D structures in 2-dimensional lateral cephalometry, with no true decomposition of the directional components of dental displacements. Tooth eruption might not only compensate for occlusal wear during the aging process but also represent an outcome of continuous growth throughout life. Dentoalveolar vertical drift during aging is a growth counterpart of the increase in the lower facial height during adulthood, as described previously.1,24–28 A previous cephalometric study of subjects from the ages of 21 years to 26 years showed that the greatest facial change was the vertical dimensions that increased by 1.5 mm in both sexes.28 The maxillary and mandibular dentoalveolar heights increased by 0.5 mm in both sexes at the same time interval.28 Studies on facial growth using metallic implants revealed no significant changes in incisor and molar eruption after the age of 16 years in females.29

The results of this study indicated a tendency to a mesial shift of molars, with statistical significance only on the right side (Table). Mesial migration of posterior teeth was believed to be associated with mesiodistal tooth wear.3,24 Previous studies have shown that mesial migration of the mandibular first molars during aging is consistent only in females.24 Behrents1 described that males have an uprighting of mandibular first molars relative to the mandibular plane, with a slight distal movement of the crown throughout life.

Sexual differences were not evaluated in our study because of the sample size. Premolars and canines demonstrated stability in the sagittal position. No previous report was found for the mesiodistal behavior of mandibular premolars and canines, probably because canines rarely are included in cephalometric evaluations. The current study is the first to report anteroposterior stability of mandibular premolars and canines, highlighting the importance of dental model registration to evaluate individual 3D dental changes.

Stability in the sagittal position of the central incisors (incisal edge) was also found, corroborating previous studies that showed no significant sagittal changes in the mandibular incisors during aging24,30,31 (Table). Behrents1 reported that the mandibular incisors tipped lingually in males and labially in females, compensating, respectively, for the counterclockwise and clockwise rotation of the mandible during adulthood.

Some tooth movements might be the result of late facial growth changes expected after the age of 17 years, especially in males. Although the present study did not test female-male differences, a similar tendency was observed in our study sample. Figure 4 illustrates that females demonstrated slight labial movement of the mandibular incisors, whereas males displayed slight lingual movement of the mandibular incisors in our 40-year follow-up. These results corroborate previous studies that showed that labial retrusion observed from early to late adulthood is predominantly the result of soft-tissue changes instead of positional changes of the incisor.1,24,31

Transverse changes demonstrated a discrete lingual displacement of the canines and first premolars during the aging process (Table). These findings agree with previous studies showing a decrease of intercanine and interpremolar width during adulthood in untreated subjects.3,5,6,9,32,33 Massaro et al3 found a 0.69-mm decrease in the mandibular intercanine width in subjects with normal occlusion, from the ages of 18 years to 60 years.

Dental model superimposition suggests that a lingual movement rather than a mesial movement of canines might be the primary causal factor for mandibular intercanine width decrease and incisor crowding increase observed during aging in previous studies.3,4,7,9,34 The slight medial shift of the central incisors observed in this study might result from incisor crowding that overlapped the homologous central incisor in some subjects (Table).

A limitation of this study is the lack of intermediate records between the ages of 17 years and 60 years, making unclear whether most of the dental changes occur in the late teens or early adulthood or if dental changes are continuous throughout life. The assumption is that the mesial movement of molars is a continuous change since interproximal tooth wear is expected to increase during aging.3,35,36 In addition, ethnic background and diet might influence dental changes during aging, and results should not be generalized for distinct ethnicities. The analysis of maxillary teeth was not performed in this study, considering that palatal rugae are not reliable for the superimposition of digital dental models when a very long time interval such as 40 years is considered.37 Some loss of volume and definition of the palatal rugae, besides a slight elongation, was observed with aging.37

Future studies with a larger sample size should elucidate male-female differences using digital model superimposition. In addition, mesiodistal and buccolingual inclination changes during aging should be evaluated.

CONCLUSIONS

Dental changes in untreated normal occlusion were slight from early to late adulthood. The eruption of anterior and posterior teeth and a tendency for lingual movement of canines and first premolars were observed during the aging process.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) (grant no. 2016/11400-8).

Footnotes

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest, and none were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Behrents RG. Growth in the Aging Craniofacial Skeleton. Ann Arbor: Center for Human Growth and Development, University of Michigan; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behrents RG. An Atlas of Growth in the Aging Craniofacial Skeleton. Ann Arbor: Center for Human Growth and Development, University of Michigan; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Massaro C, Miranda F, Janson G, Rodrigues de Almeida R, Pinzan A, Martins DR, et al. Maturational changes of the normal occlusion: a 40-year follow-up. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2018;154:188–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miranda F, Massaro C, Janson G, de Freitas MR, Henriques JFC, Lauris JRP, et al. Aging of the normal occlusion. Eur J Orthod 2019;41:196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinclair PM, Little RM. Maturation of untreated normal occlusions. Am J Orthod 1983;83:114–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bishara SE, Treder JE, Jakobsen JR. Facial and dental changes in adulthood. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1994;106: 175–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter GA, McNamara JA Jr. Longitudinal dental arch changes in adults. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1998;114:88–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thilander B. Dentoalveolar development in subjects with normal occlusion. A longitudinal study between the ages of 5 and 31 years. Eur J Orthod 2009;31:109–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsiopas N, Nilner M, Bondemark L, Bjerklin K. A 40 years follow-up of dental arch dimensions and incisor irregularity in adults. Eur J Orthod 2013;35:230–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Little RM. The irregularity index: a quantitative score of mandibular anterior alignment. Am J Orthod 1975;68:554–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pauls AH. Therapeutic accuracy of individualized brackets in lingual orthodontics. J Orofac Orthop 2010;71:348–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Almeida MA, Phillips C, Kula K, Tulloch C. Stability of the palatal rugae as landmarks for analysis of dental casts. Angle Orthod 1995;65:43–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailey LT, Esmailnejad A, Almeida MA. Stability of the palatal rugae as landmarks for analysis of dental casts in extraction and nonextraction cases. Angle Orthod 1996;66:73–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi JI, Cha BK, Jost-Brinkmann PG, Choi DS, Jang IS. Validity of palatal superimposition of 3-dimensional digital models in cases treated with rapid maxillary expansion and maxillary protraction headgear. Korean J Orthod 2012;42:235–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jang I, Tanaka M, Koga Y, Iijima S, Yozgatian JH, Cha BK, et al. A novel method for the assessment of three-dimensional tooth movement during orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod 2009;79:447–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park TJ, Lee SH, Lee KS. A method for mandibular dental arch superimposition using 3D cone beam CT and orthodontic 3D digital model. Korean J Orthod 2012;42:169–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.An K, Jang I, Choi DS, Jost-Brinkmann PG, Cha BK. Identification of a stable reference area for superimposing mandibular digital models. J Orofac Orthop 2015;76:508–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt F, Kilic F, Piro NE, Geiger ME, Lapatki BG. Novel method for superposing 3D digital models for monitoring orthodontic tooth movement. Ann Biomed Eng 2018;46:1160–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ioshida M, Muñoz BA, Rios H, Cevidanes L, Aristizabal JF, Rey D, et al. Accuracy and reliability of mandibular digital model registration with use of the mucogingival junction as the reference. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2019;127:351–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986;1:307–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleiss JL. Design and Analysis of Clinical Experiments. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ainamo A. Influence of age on the location of the maxillary mucogingival junction. J Periodontal Res 1978;13:189–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.SEDENTEXCT. Cone beam CT for dental and maxillofacial radiology: evidence based guidelines. Available at: www.sedentexct.eu/files/radiation_protection_172.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2018.

- 24.West KS, McNamara JA Jr. Changes in the craniofacial complex from adolescence to midadulthood: a cephalometric study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1999;115:521–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forsberg CM, Odenrick L. Changes in the relationship between the lips and the aesthetic line from eight years of age to adulthood. Eur J Orthod 1979;1:265–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Israel H. Age factor and the pattern of change in craniofacial structures. Am J Phys Anthropol 1973;39:111–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Israel H. Recent knowledge concerning craniofacial aging. Angle Orthod 1973;43:176–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarnäs KV, Solow B. Early adult changes in the skeletal and soft-tissue profile. Eur J Orthod 1980;2:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iseri H, Solow B. Continued eruption of maxillary incisors and first molars in girls from 9 to 25 years, studied by the implant method. Eur J Orthod 1996;18:245–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sinclair PM, Little RM. Dentofacial maturation of untreated normals. Am J Orthod 1985;88:146–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pecora NG, Baccetti T, McNamara JA Jr. The aging craniofacial complex: a longitudinal cephalometric study from late adolescence to late adulthood. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2008; 134:496–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bishara SE, Jakobsen JR, Treder J, Nowak A. Arch width changes from 6 weeks to 45 years of age. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1997;111:401–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henrikson J, Persson M, Thilander B. Long-term stability of dental arch form in normal occlusion from 13 to 31 years of age. Eur J Orthod 2001;23:51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bishara SE, Treder JE, Damon P, Olsen M. Changes in the dental arches and dentition between 25 and 45 years of age. Angle Orthod 1996;66:417–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.d’Incau E, Couture C, Maureille B. Human tooth wear in the past and the present: tribological mechanisms, scoring systems, dental and skeletal compensations. Arch Oral Biol 2012;57: 214–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Begg PR. Stone age man’s dentition: with reference to anatomically correct occlusion, the etiology of malocclusion, and a technique for its treatment. Am J Orthod 1954;40:298–312. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garib D, Miranda F, Yatabe MS, Lauris JRP, Massaro C, McNamara JA Jr, et al. Superimposition of maxillary digital models using the palatal rugae: does ageing affect the reliability? Orthod Craniofac Res 2019;22:183–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]