Abstract

Situations of public calamity, such as that caused by COVID-19 pandemic, strongly impact mental health, especially among people who feel most anxious about the imminence of death, as highlighted by the Terror Management Theory. In this research, we investigated how and under which conditions concerns about death itself and anxiety are related to psychological well-being. Specifically, we assessed the role of fear caused by the prominence of death (contextual and dispositional) in anxiety and well-being during the pandemic. Participants were 352 Brazilians, who answered a measurement of fear of death and read a news story about COVID-19. The manipulated news brought the idea of death to prominence (vs. non-prominence). After reading the news, the participants answered scales of anxiety and psychological well-being. The results showed that individual differences in fear of death related to well-being, and that this relationship was mediated by anxiety in face of COVID-19. Contrastingly, the manipulation of the salience of death in the news did not affect this relationship. These results contribute to the understanding of a psychological process related with fluctuations in individuals' well-being during the pandemic, offering insights for future studies that can promote better coping conditions during this period of world crisis.

Keywords: COVID-19, Mortality prominence, Mental health, Terror management, Well-being

1. Introduction

On December 31st, 2019 the World Health Organization (WHO) was alerted to a growing number of cases of atypical pneumonia among the city of Wuhan, in the province of Hubei, China (Cascella et al., 2020). It was the unfolding of a new type of virus, hitherto not identified in humans (Amawi et al., 2020). The new virus, called SARS-CoV-2 (or new Coronavirus), causes severe acute respiratory syndrome, and the disease which has been called COVID-19 (Gorbalenya et al., 2020). This disease was the number one cause of death in Brazil during 2020, where more than 200,000 people lost their lives to this disease, and more than 8 million infected people have fallen ill (DATASUS, 2020).

The increase in the number of cases and the global spread of the new Coronavirus in a short time led WHO to declare the COVID-19 pandemic on March 11th, 2020 (WHO, 2020). At the time, they recommended that, for individuals to protect themselves against SARS-CoV-2 infection, it was essential to maintain personal hygiene (e.g., washing hands frequently, using hand sanitizer etc.). When these measures became insufficient to contain the spreading of the virus (given the effectiveness of its large-scale proliferation capacity), several government organizations, in agreement with the WHO, adopted a social distancing public policy. In other words, to mitigate the number of COVID-19 cases, it was important that people stayed at home, avoiding contact with others as much as possible to protect public health systems from collapse, and thus preventing a mass mortality event.

As a consequence of these social distancing measures, people's mental health concerns have been severely affected (Zhu et al., 2021). Indeed, because involuntary isolation frustrates the social nature of the human being, the abrupt reduction in social contact could have negative psychological consequences. This can be seen through reports of increased anxiety and the development of symptoms of severe psychological syndromes, such as depression and other psychotic affective spectrum disorders (Pietrabissa & Simpson, 2020). In this context, individuals' mental suffering has increased over time, as emphasized by the United Nations' secretary-general, António Guterres, in May 2020 (Guterres, 2020). These are still plausible hypotheses to understand the impact of the abrupt containment of social relationships on general psychological well-being (Gaspar & Balancho, 2017). As a matter of fact, both the adherence to social isolation and its consequences on psychological well-being occur because of the fear of being infected with the virus or dying as a result of COVID-19, this fear being potentiated by the abundant flood of information released by the media. However, it is not yet effectively-known if the media-promoted prominence of the fear of contamination with the new coronavirus indeed increases the activation of psychological states sensitive to negative information, such as anxiety, and the impact of this activation on psychological well-being. The present article contributes to overcoming this gap by proposing that the salience of fear of death is related to the current pandemic scenario's anxiety. Moreover, we predicted that the increase of such anxiety is associated with worse indicators of psychological well-being.

A variable that may help us understand the impact of COVID-19 on anxiety and psychological well-being is the fear of death. According to the Terror Management Theory (Greenberg et al., 1986), human beings guide their behavior from how they manage fears related to death (Pyszczynski et al., 2015). This theoretical perspective argues that fear of mortality can be experienced at two levels: the contextual level, i.e., where the context highlights the inevitability of death; and the dispositional level, i.e., individual differences on how each person reacts to the contingencies of life that indicate the inevitability of death (Greenberg et al., 1994). Previous research from the Terror Management Theory indicates that some psychological factors and states act as a buffer for fear of death's effect on individuals' well-being (see Arrowood & Cox, 2020, for a review). Accordingly, dysfunctional regulation of fear of death can lead individuals to develop anxiety and the subsequent psychological malaise (Pyszczynski et al., 2020).

Indeed, Juhl and Routledge (2016) demonstrated that individuals experience more anxiety when mortality has been emphasized and, as a consequence, express lower psychological well-being. The contextual salience of death's idea can have negative psychological impacts (Klackl & Jonas, 2019). For instance, when reading a news piece highlighting death, individuals may momentarily feel anxious and present lower psychological well-being. Furthermore, fear of death has also been studied as something dispositional (see Pyszczynski et al., 2015, for a review). Throughout life, individuals develop feelings and attitudes towards their deaths, those with higher fear of death are likely more vulnerable to situations such as a pandemic. If this process does occur, then the following events are probable: (1) the news content about COVID-19, when highlighting deaths caused by the illness, influences individuals' anxiety and well-being; (2) the more prominent the fear of death, the more individuals are vulnerable to developing anxiety in the face of COVID-19, and thus experiencing lower psychological well-being; (3) the salience of mortality, contextually activated by the news that emphasizes death by COVID-19, increases the negative impacts of fear of death on the anxiety and well-being of individuals who have access to this news.

Thus, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, we seek to analyze how the fear of mortality interferes with anxiety and, consequently, with individuals' psychological well-being. We predicted that (a) the contextual salience of mortality (e.g., reading news about deaths by Covid-19) leads individuals to think about their deaths, and this increases anxiety momentarily and decreases psychological well-being; (b) regardless of the context, the individual differences in fear of death impact anxiety and psychological well-being (i.e., the relationship between individual differences in fear of death and psychological well-being is mediated by anxiety regarding COVID-19); and (c) the context of mortality salience enhances individual differences in fear of death, impacting anxiety and psychological well-being (i.e., the mediation is moderated by the salience of contextual death, based on news concerning deaths caused by COVID-19). To test these hypotheses, we developed an experimental study.

We addressed a phenomenon that has critically transformed the lifestyle of most people around the world. Specifically, we explored the role of news reports about COVID-19 in increasing levels of anxiety and decreasing individuals' psychological well-being. The situation of vulnerability and the proximity with the idea of death that the pandemic context provides, which is continuously reinforced by the media, can negatively impact mental health. Therefore, this study's results can contribute to our understanding of the negative psychological consequences caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, and it can shed light on the impact of news about COVID-19 on individuals' mental health.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and research design

This is a unifactorial experimental study conducted between March to August 2020, in which we manipulated two news reports about the COVID-19 pandemic (control vs. mortality salience). We defined the sample size beforehand using WebPower (Zhang & Yuan, 2018) by taking into account a median effect size (f = 0.25), standard parameters of α = 0.05, and power = 0.95. Considering our experimental design, the sample size necessary to detect the predicted effect was 210 or higher. Thus, three-hundred-fifty-two (352) Brazilians from the general population participated in this study. That is, the study is sufficiently powered to detect the expected effects. Most of the participants were female (71%), aged between 18 and 65 years old (M = 29.56, SD = 9.97), of single marital status (68.5%), and predominantly heterosexual (74.7%). Participants were randomly allocated to one of two experimental conditions: non-salience of mortality (n = 171); condition of salience of mortality by COVID-19 (n = 181).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Mortality awareness measure

To assess individual differences in participants' susceptibility to fear of death, we used the adaptation of the Multidimensional Mortality Awareness Measure (Levasseur, McDermott, & Lafreniere, 2015), more precisely the Fear of Mortality dimension. This measurement consists of 10 items, which assess individuals' concerns related to the impossibility of escaping the end of life. The items are answered in a four-point Likert scale (1 = does not apply to me; 4 = applies to me), and the higher the score of the participants, the greater the fear of mortality. Examples of items are: “I get nervous when I think about death”, “I think about death as a negative thing”. We have no information about the psychometric properties of this scale in the Brazilian context. For this reason, it was necessary to perform an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using the principal-axis factoring extraction method to address the items' dimensionality, as Hair et al. (2013) suggested for similar situations to the current study. We found a single factor (eigenvalue = 3.97; explained variance = 39.8%), with strong internal consistence as estimated by Cronbach's alpha (α = 0.86) and by McDonald's omega coefficients (ω = 0.86).

2.2.2. Anxiety associated with COVID-19 measure

Participants responded to a measurement that assessed how anxious they felt about the threat of the new coronavirus – the COVID-19 Anxiety Scale (Silva et al., 2020). We presented them with a set of seven items, based on the characteristics of anxious behavior operationalized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V). Examples of items are: “I feel anxious about COVID-19”, “I feel heart racing when I read about COVID-19”. They responded using a Likert scale ranging from 0 (does not apply to me) to 3 (applies to me). The higher the score, the greater the anxiety about COVID-19. This measure shows high internal consistency (α = 0.89, ω = 0.89).

2.2.3. Psychological well-being measure

To assess the psychological well-being, we used the adapted version of the General Questionnaire for Reduced Psychological Well-Being – QGBEP-R (Pereira et al., 2018). The QGBEP-R is a unifactorial measure, composed of six items, being answered in a Likert scale of 5 points, being 0 (not applicable to me) and 5 (applicable to me). In this study, the internal consistency was strong (α = 0.82, ω = 0.83).

2.3. Procedures

Before starting data collection, the research protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee of the first author's institution. After this stage, we invited participants through posts on social media groups, such as Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram. Participants were presented with a link to access the survey form, available on the Qualtrics Platform, whose home page contained the Informed Consent Form (ICF). The ICF contained information about the purpose of the study, the condition of volunteering, as well as the contact of the responsible researcher and the ethics committee responsible for the study (World Medical Association, 2001). Those who agreed to participate in the study responded to the set of instruments. After responding to the measurement of susceptibility to fear of death, the participants read a news report allegedly published in a nationally circulated newspaper regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. Depending on the experimental condition, the news highlighted the imminence of death by COVID-19, or did not emphasize this possibility. Specifically, in the condition of mortality salience, they read the following text:

“The increase in confirmed cases in Brazil has worried authorities about the control of the virus in the country. Up to August 8th, state health departments accounted for 3 million infected people in all states and 96 thousands deaths. In Ceará [Brazilian city], a three-month-old baby died of the infection, the youngest to date. An epidemiological bulletin made by the Ministry of Health points to a phase of uncontrolled acceleration of the pandemic in the country. According to the document, it is estimated that up to 2 million deaths can occurs due to the virus in Brazil.”

Contrastingly, in the condition of non-salience of mortality (control), the participants read the following text:

“COVID-19 is the name of the disease caused by the new coronavirus SARS-COV-2, which can cause respiratory infection. In Brazil, the first case of COVID-19 was announced on February 26th. To prevent infection by the virus, the Ministry of Health makes the following recommendations: Wash your hands with soap and water or use hand sanitizer; cover your nose and mouth when breathing or coughing; avoid crowds if you are ill; keep rooms well ventilated; do not share personal objects.”

Finally, we debriefed the participants by informing them about the objectives of the study and the fictional nature of the news about COVID-19.

2.4. Data analysis

We used the Jamovi software (The Jamovi Project, 2019; R Development Core Team, 2008) for data analysis. To test our prediction, we performed three regression equations. In the first one, we regressed the psychological well-being on both contextual (dummy coded: 0 = no salience; 1 = mortality salience) and dispositional fear of mortality, and the interaction term (i.e., contextual*dispositional). In the second equation, we estimated the effects of these predictors on anxiety. In the final equation, we added anxiety (and its interaction terms) as a predictor of psychological well-being in the set of predictors included in the first equation. The estimated parameters in these equations allowed us to analyze whether anxiety mediated the effects of fear of death (of both contextual and dispositional) on individuals' psychological well-being. In addition, by including the interaction terms in the equations, we explored whether the mediating role of anxiety in the relationship between individual differences in fear of death and psychological well-being was moderated by the contextual salience of death, promoted by reading a news story about COVID-19. Hence, we followed the required procedures to test a moderated-mediation model (Muller et al., 2005), for which we computed confidence intervals of the mediating effects by using bootstrapping techniques with 10,000 resamples.

3. Results

We started by analyzing the correlations between the measured variables. Both fear of death and anxiety about COVID-19 are moderately to strongly related to individuals' well-being (Table 1 ). Specifically, the stronger the fear of death and the more intense the anxiety, the lower the psychological well-being. In addition, those who have a high fear of death are those presenting the greatest anxiety. The average well-being of individuals was 1.37 (SD = 1.44), which was low considering the response scale that varied between 0 and 5. On the other hand, the levels of anxiety in the face of COVID-19 and fear of death were relatively high, since the response scales of both varied between 1 and 4.

Table 1.

Correlations among measures.

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Mortality awareness | 2.39 | 0.74 | ||

| 2. Anxiety associated with COVID-19 | 2.48 | 0.81 | 0.43⁎⁎⁎ | |

| 3. Psychological well-being | 1.37 | 1.44 | −0.29⁎⁎⁎ | −0.46⁎⁎⁎ |

p < .001.

Table 2 presents the estimated parameters in three regression equations. In the first one, we found a significant effect of fear of death on psychological well-being, that is, the greater the fear of death, the lower the well-being (b = −0.57, p < .001).

Table 2.

Estimated parameters moderated mediation model.

| Predictor | Step 1 |

Step 2 |

Step 3 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PWB |

AAC |

PWB |

||||

| b | t | b | t | b | t | |

| MA | −0.57 | −5.76⁎⁎⁎ | 0.47 | 9.00⁎⁎⁎ | −0.22 | −2.22⁎⁎ |

| EM | 0.18 | 1.25 | −0.08 | −1.04 | −0.09 | −0.19 |

| MA x EM | 0.14 | 0.73 | −0.11 | −1.05 | 0.02 | 0.12 |

| AAC | −0.71 | −7.69⁎⁎⁎ | ||||

| AAC x EM | 0.08 | 0.47 | ||||

Note. AAC = Anxiety Associated with COVID-19; EM = Experimental Manipulation (0 = control, 1 = mortality salience); MA = Mortality Awareness; PWB = Psychological Well-Being; b = Unstandardized regression coefficients.

p < .001.

p < .01.

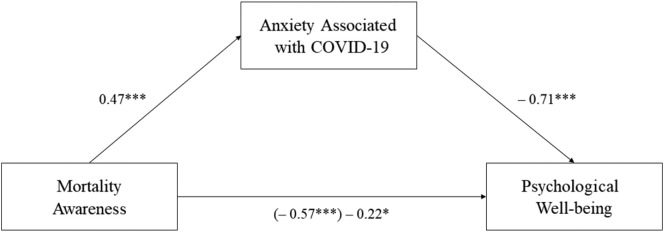

In the second equation, we identified that the fear of death also significantly predicts anxiety (b = 0.47, p < .001), this time in a positive way: the greater the fear of death, the greater the anxiety. In the third equation, the results showed that both fear of death (b = −0.22, p < .01) and anxiety (b = − 0.71, p < .001) are negatively related to psychological well-being, which indicates that anxiety mediates the relationship between fear of death and well-being. In fact, and as it can be seen in Fig. 1 , the relationship between fear of death and well-being is significantly mediated by anxiety (indirect effect = −0.35, 95% CI: −0.47; −0.23).

Fig. 1.

The impact of mortality awareness on participant's psychological well-being mediated by the anxiety associated with COVID-19.

Note. ⁎⁎⁎p < .001. ⁎p < .05.

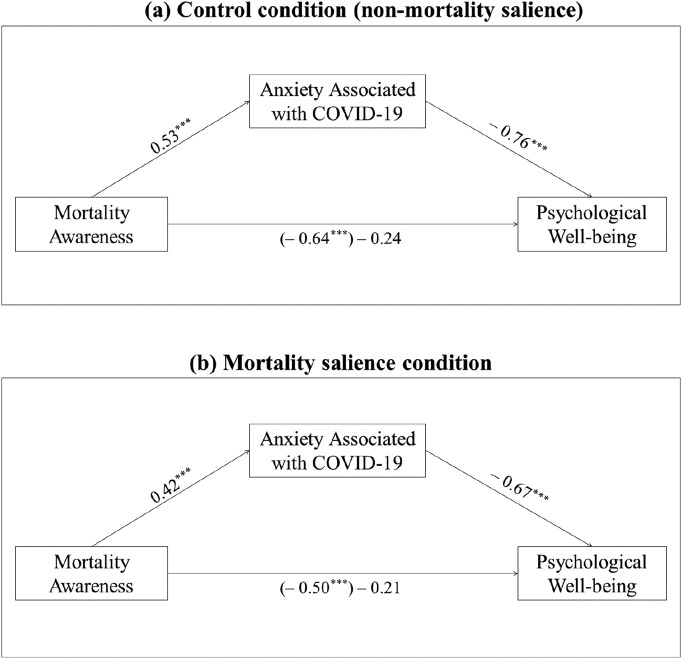

The results also reveal that the contextual salience of death, experimentally manipulated with newspaper articles, did not influence anxiety or psychological well-being. Additionally, there is also no evidence that this manipulation moderated the relationships between individual differences regarding fear of death, anxiety, and well-being, as none of the interactions proved to be significant. This result indicates that the mediating role of anxiety in the relationship between individual differences in fear of death and well-being occurred in an equally intense way, both in the mortality and non-mortality salience conditions. In fact, as we can see in Fig. 2 , the mediation process occurred in a significant way both in the condition of mortality salience (indirect effect = −0.28, 95%, Boot. CI = −0.40. −0,15), and in the condition of non-salience (indirect effect = −0.40, 95%, Boot. CI = −0.55. −0.25).

Fig. 2.

Effect of mortality awareness on participant's psychological well-being mediated by the anxiety associated with COVID-19 in each condition of the experimental manipulation.

Note. ⁎⁎⁎p < .001.

4. Discussion

We investigated how and under which conditions fear of death is related to individuals' psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. We tested the hypotheses that: (a) the contextual salience of mortality (e.g., reading news about COVID-19 deaths) leads individuals to think about their own deaths, momentarily increasing anxiety and decreasing psychological well-being; (b) the relationship between individual differences in fear of death and psychological well-being is mediated by anxiety regarding COVID-19; and (c) this mediation is moderated by the salience of contextual death, based on news concerning deaths caused by COVID-19. The results confirmed most of our predictions. Individuals differences in fear of death is related to well-being, and this relationship is mediated by anxiety. On the other hand, the salience of contextual mortality did not influence this relationship, which did not confirm our first hypothesis.

These results have important implications for the study of psychological well-being in the current context of social isolation, and contribute to the literature on fear of death within the scope of the Terror Management Theory (Arrowood & Cox, 2020; Pyszczynski et al., 2020). Previous studies have already shown that the individual differences in concern about mortality increases anxiety and decreases well-being (Juhl & Routledge, 2016). Our research went further, by demonstrating that the levels of fear of death as a psychological disposition is a strong predictor of lower well-being, and that this relationship is mediated by anxiety regarding COVID-19. Contrastingly, our results showed that the content of the news concerning the pandemic, regarding the salience or not of the number of deaths, does not cause changes in anxiety and well-being. It is important to note that individuals' well-being scores were very low, indicating that Brazilians recognize that the present situation is a source of psychological suffering during the pandemic, as was already predicted by the WHO (Guterres, 2020), although this situation is not due to the information they receive regarding the level of mortality caused by the new coronavirus.

The most innovative aspect in the present research is the evidence that the intensity of concern that individuals have with the imminence of death, and the negative relationship they have with the idea of their own death. This is relevant to understand their psychological states of greatest anxiety and sadness during a pandemic. Previous studies have suggested that the salience of mortality would be a particularly important predictor of these psychological variables (Gordillo et al., 2017). However, in a pandemic context, it can be considered that the contextual salience conveyed in news reports contributes little to aggravate a situation where the imminence of death seems to be largely internalized in individuals' lives. The current research contributes to the understanding of this phenomenon, showing that news content that addresses the word “death” does not moderate the effect of fear of death on anxiety and well-being. These findings open new possibilities for further research aiming to understand the role of this psychological disposition in individuals' quality of life, especially during a pandemic.

Thus, considering that the fear of death plays a central role in individuals' mental health, it is crucial to examine some predictors of this variable and their potential as a resource to prevent anxiety in the face of COVID-19 and the consequent psychological suffering. The protective effects of self-esteem for psychological well-being are already known (Du et al., 2017), which can also act as a buffer for the adverse effects of the fear of death on anxiety and psychological malaise (Helm et al., 2018). Similarly, believing in a just world has also proved to be an excellent protective factor for well-being (Yu et al., 2018). According to this hypothesis, people have a need to believe that they live in a world that is a fair place where good things happen to good people, while bad things happen to bad people. People with a belief in this highly fair world may consider themselves less vulnerable to COVID-19, because they assume that bad things do not occur to them, as they tend to perceive themselves as good people. Following this line of thought, we suggest that in future studies the effects of believing in a fair world and of self-esteem to be controlled. Additionally, it should be investigated whether the mere fact that the news piece contains the word COVID-19 already raises the salience of mortality in individuals, since in our study we do not have a control condition that allows analyzing this possibility.

Although our results provided essential contributions to understanding the pandemic-based anxiety effect on well-being, the current study has some limitations. First, we did not access information regarding the participants' consumption of news about COVID-19 (e.g., how often they followed the sequential progress of pandemic news and the specific media they consulted for it). Second, we did not gather more information about the sample's characteristics (e.g., contact with people diagnosed with COVID-19, whether they had chronic diseases, and if they were part of some risk group). Third, most of the participants were women, which narrowed the scope of our findings. Fourth, we used only one type of media in our experimental manipulation (i.e., news report). Given these shortcomings, future studies must explore the impact of these variables on the relationship between media consumption and psychological outcomes.

Finally, the pattern of results allows us to conclude that the more individuals worry about their own deaths, the more anxiety they feel within the COVID-19 pandemic social environment, and the less psychological well-being is perceived, which reveals that individuals are reacting to the pandemic with the recognition of the presence of negative changes in their psychological well-being, especially for those who already relate more negatively to the idea of their own deaths. We believe that the enhancement of buffers for this effect can contribute to a reduction in this suffering. More importantly, by promoting an increase in self-esteem, based on strategies to strengthen self-worth. In addition, at a societal level, seeking a guarantee that individuals perceive their surroundings as fair, reliable, and stable could significantly contribute to the reduction of their negative concerns about death. The inclusion of these factors would help to better understand the complexity of the phenomenon, and could play a fundamental role in the development of strategies and policies to promote a better well-being among the population during the pandemic.

Data availability statements

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the OPEN SCIENCE FRAMEWORK repository, https://osf.io/9s782/.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Washington Allysson Dantas Silva: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Software, Investigation. Tátila Rayane de Sampaio Brito: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Software, Investigation. Cicero Roberto Pereira: Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Rui Costa-Lopes for giving us access to data collection tools. This work was funded by a scholarship grant of the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES; Finance Code 001) awarded to Washington Allysson Dantas Silva, and to Tátila Rayane de Sampaio Brito. The manuscript’s preparation was also supported by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq: 312095/2018-0) and by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT: PTDC/PSI-GER/30928/2017) awarded to Cicero Roberto Pereira.

References

- Amawi H., Abu Deiab G.I., Aljabali A.A., Dua K., Tambuwala M.M. COVID-19 pandemic: An overview of epidemiology, parthenogenesis, diagnostics and potential vaccines and therapeutics. Therapeutic Delivery. 2020;35(1):1–24. doi: 10.4155/tde-2020-0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrowood R.B., Cox C.R. Terror management theory: A practical review of research and application. Brill Research Perspectives in Religion and Psychology. 2020;2(1):1–83. doi: 10.1163/25897128-12340003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cascella M., Rajnik M., Cuomo A., Dulebohn S.C., Di Napoli R. Stat Pearls Publishing; 2020. Features, evaluation and treatment coronavirus (COVID-19) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DATASUS Painel de casos de doença pelo coronavírus 2019 (COVID-19) no Brasil [Panel of cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Brazil by the Ministry of Health] Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. 2020 https://covid.saude.gov.br/ [Google Scholar]

- Du H., King R.B., Chi P. Self-esteem and subjective well-being revisited: The roles of personal, relational, and collective self-esteem. PLoS One. 2017;12(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar T., Balancho L. Fatores pessoais e sociais que influenciam o bem-estar subjetivo: diferenças ligadas estatuto socioeconômico. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2017;22(4):1373–1380. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232017224.07652015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbalenya A.E., Baker S.C., Baric R.S., de Groot R.J., Drosten C., Gulyaeva A.A. The species severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: Classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nature Microbiology. 2020;5(4):536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordillo F., Mestas L., Arana J.M., Pérez M.A., Escotto E.A. The effect of mortality salience and type of life on personality evaluation. Europe’s Journal of Psychology. 2017;13(2):286–299. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v13i2.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg J., Pyszczynski T., Solomon S. In: Public self and private self (pp. 189–212) Baumeister R.F., editor. Springer; 1986. The causes and consequences of a need for self-esteem: A terror management theory. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg J., Pyszczynski T., Solomon S., Simon L., Breus M. Role of consciousness and accessibility of death-related thoughts in mortality salience effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67(4):627–637. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guterres A. (May 13). Mental health services are an essential part of all government responses to COVID-19. United Nations. 2020. https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/mental-health-services-are-essential-part-all-government-responses-covid-19

- Hair J.F., Black B., Babin B.J., Anderson R.E. 2013. Multivariate data analysis: Global edition (7th edition) (Pearson) [Google Scholar]

- Helm P.J., Duchschere J.E., Greenberg J. In: Curing the dread of death theory, research and practice (pp. 219–237) Menzies R.E., Menzies R.G., Iverach L., editors. Australian Academic Press; 2018. Treating low self-esteem: Cognitive behavioural therapies and terror management theory. [Google Scholar]

- Juhl J., Routledge C. Putting the terror in terror management theory: Evidence that the awareness of death does cause anxiety and undermine psychological well-being. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2016;25(2):99–103. doi: 10.1177/0963721415625218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klackl J., Jonas E. Effects of mortality salience on physiological arousal. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019;10:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levasseur O., McDermott M.R., Lafreniere K.D. The multidimensional mortality awareness measure and model: Development and validation of a new self-report questionnaire and psychological framework. Journal of Death and Dying. 2015;70(3):317–341. doi: 10.1177/0030222815569440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller D., Judd C.M., Yzerbyt V. When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89(6):852–863. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira M.C.A.R.S., Antunes M.C.Q., Barroso I.M.A.R.C., Correia T.I.G., Brito I.S., Monteiro J.F.S.P.M. Adaptação e validação do Questionário Geral de Bem-Estar Psicológico: análise fatorial confirmatória da versão reduzida. Revista de Enfermagem Referência. 2018;18(4):9–18. doi: 10.12707/RIV18001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrabissa G., Simpson S.G. Psychological consequences of social isolation during COVID-19 outbreak. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020;11:2201–2204. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyszczynski T., Lockett M., Greenberg J., Solomon S. Terror management theory and the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 2020;60(6):1–17. doi: 10.1177/0022167820959488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyszczynski T., Solomon S., Greenberg J. In: Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 52, pp. 1–70) Zanna M., Olson J., editors. Academic Press; 2015. Thirty years of terror management theory: From genesis to revelation. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2008. http://www.R-project.org

- Silva W.A.D., Brito T.R.S., Pereira C.R. COVID-19 anxiety scale (CAS): Development and psychometric properties. Current Psychology. 2020;39(6):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-01195-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Jamovi Project Jamovi (Version 1.1.9.0) [Computer Software] 2019. https://www.jamovi.org

- WHO. World Health Organization March 11. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on. 2020;COVID-19 https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association World medical association declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bulletin World Health Organization. 2001;79:373–374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X., Ren G., Huang S., Wang Y. Undergraduates’ belief in a just world and subjective well-being: The mediating role of sense of control. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal. 2018;46(5):831–840. doi: 10.2224/sbp.6912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Yuan K.H. 2018. Practical statistical power analysis using R and WebPower. (ISDSA) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Zhang L., Zhou X., Li C., Yang D. The impact of social distancing during COVID-19: A conditional process model of negative emotions, alienation, affective disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;281(4):131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the OPEN SCIENCE FRAMEWORK repository, https://osf.io/9s782/.