Abstract

The outbreak of coronavirus is spreading at an unprecedented rate to the human populations and taking several thousands of life all over the globe. In this paper, an extension of the well-known susceptible-exposed-infected-recovered (SEIR) family of compartmental model has been introduced with seasonality transmission of SARS-CoV-2. The stability analysis of the coronavirus depends on changing of its basic reproductive ratio. The progress rate of the virus in critical infected cases and the recovery rate have major roles to control this epidemic. Selecting the appropriate critical parameter from the Turing domain, the stability properties of existing patterns is obtained. The outcomes of theoretical studies, which are illustrated via Hopf bifurcation and Turing instabilities, yield the result of numerical simulations around the critical parameter to forecast on controlling this fatal disease. Globally existing solutions of the model has been studied by introducing Tikhonov regularization. The impact of social distancing, lockdown of the country, self-isolation, home quarantine and the wariness of global public health system have significant influence on the parameters of the model system that can alter the effect of recovery rates, mortality rates and active contaminated cases with the progression of time in the real world.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Epidemiology, Mathematical modeling, Stability analysis, Bifurcation analysis, Spatial patterns

2010 MSC: 92B5, 92D25, 92D30, 92C60

1. Introduction

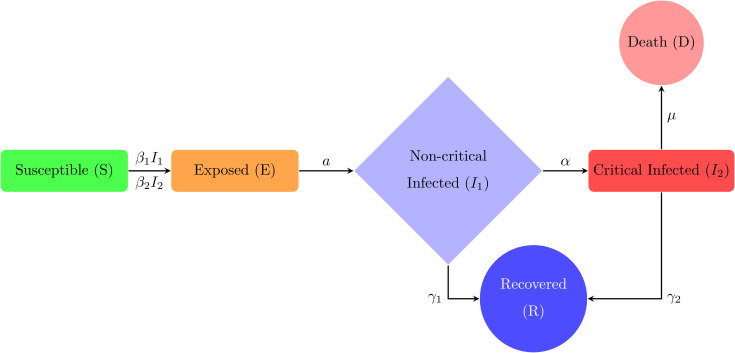

Susceptible individuals are those who have never been infected with and thus have no immunity against COVID-19. Susceptible individuals become exposed once they are infected with the disease. The next stage is Exposed individuals in which those who have been infected with COVID-19 but are not yet infectious to others. An individual remains exposed for the length of the incubation period, after which they become infectious and experience non-critical clinical symptoms . Infected individuals with a non-critical infection experience symptoms like fever and cough and may even have mild pneumonia but do not require hospitalization. These individuals may either recover or progress to the critical stage of the disease. One step further when the Infected individuals with a critical infection experience respiratory failure, septic shock, and/or multiple organ dysfunction or failure and require treatment in an ICU. These individuals may either recover or die from the disease. Recovered individuals are those who have recovered and are assumed to be immune to future infection with COVID-19 and lastly dead individuals are those who have died in COVID-19. The flow chart diagram is given in (1 ).

Fig. 1.

Extended SEIR model formulation.

Previously many studies have been done on the natural clinical progression of COVID-19 infection [43], [44], [54], [69]. Infected individuals do not immediately develop severe symptoms, but instead pass through milder phases of infection first. In some studies, mild infections are grouped into two different categories, mild and moderate, where individuals with moderate infection show radiographic signs of mild pneumonia. These mild and moderate cases occur at roughly equal proportions [73]. There is some debate about the role of pre-symptomatic transmission (occurring from exposed cases) and asymptomatic infected cases for coronavirus, which are not include in the present model [38], [42]. Here, a compartmental epidemiological model is formulated, followed by the traditional SEIR model, to illustrate the spread and clinical progression of COVID-19 [11], [37], [48], [67]. It is important to track the different clinical outcomes of infection, since they require different level of healthcare resources to care for and may be tested and isolated at different rates [4], [24], [46], [61]. Susceptible individuals who become infected start out in an exposed class where they are asymptomatic and do not transmit infection. The rate of progressing from the exposed stage to the infected stage where the individual is symptomatic and infectious, occurs at rate . Infected individuals begin with non-critical infection with a recovery rate and progress to critical infection at rate of . Individuals with critical infection recover at rate and death with rate of . Recovered individuals are tracked by class (R) and are assumed to be protected from re-infection for life [20], [77]. Individuals may transmit the infection at any stage with the transmission rates and respectively [7], [8], [13], [18]. The formulation of model is considered as a system of differential equations and the outcome therefore indicates the prospective values of every portion [9], [10], [45], [55], [57]. It does not take into account stochastic events, and so the epidemic cannot go extinct even when it gets to very low values (except when an intervention is stopped, at which case the number of individuals in each state is rounded to the nearest integer). The models do not fit for the imparity of expectant variables, which may occasionally be large. Population group experiences non-critical phase before turning as critical infected group. However, individual associated with in a critical group may die and rest of the population transmits the infection at similar rate with susceptible to infected groups. Therefore, the SARS-CoV-2 model system is introduced as follows:

| (1) |

The initial conditions of (1) are given as . The dynamical behaviour of the model system is calculated by a set of rate parameters which include the transmission rates and the progression rates and the recovery rates and and the death rate . In general, the parameter values are not measured directly in studies, other measurable quantities could be supported to back out these parameters. The time spent in the exposed class is called the incubation period and is generally assumed to be equal to the time between exposure to an infected source and the development of symptoms. In the model the average incubation period is . The infectious period is the time during which an individual can transmit to others [35], [58], [60]. There are potentially two different infectious periods, occurring during each clinical stage of infection and . Duration of each of these stages has been observed. The study shows that an individual is most infectious during the stage of non-critical infection period. At this period population would still be in the community and feeling well enough to interact with others. However there is also a chance to transmit the disease into the further stage such as critical stage [19], [66]. This phenomena is exemplified such as the transmission from hospitalized patients to their healthcare providers. At a population level, we expect most transmission to occur from these individuals with non-critical stage of infection, since most of the patients do not progress past this stage. For COVID-19, one can estimate the duration of the first stage from the duration of non-critical symptoms, the time from symptom onset to hospitalization (e.g. progress to critical stage), or the duration of viral shedding via sputum or throat swabs, the serial interval between symptom onset in an index case and a secondary case they infect. The probability of progressing to the critical stage is equal to the proportion of all infections that end up to critical. Individuals with critical infection need hospitalization. The duration of critical infections, which could be reported as the time from hospital admission to recovery for individuals or the time from hospital admission to ICU admission (since critical cases require ICU-level care). Since there are not direct estimates of this duration, we instead use estimates of the total time from symptom onset to ICU-admission (e.g. the length of critical infection). At the critical infection stage ICU care, generally with mechanical ventilation, is required. The duration of this stage of infection is the time from ICU admission to recovery or death. Study report shows that the total time from hospital admission to death, which can approximate the duration of the critical stage [34], [35], [36]. The case fatality ratio (CFR) describes the fraction of all symptomatic infected individuals who eventually die. Since individuals must progress to critical infection to die, the conditional probability of someone in the critical stage dying vs recovering is given by the CFR divided by the fraction of all critical infections.

1.1. Extended SEIR model with seasonality transmission of the disease

The model now includes the possibility for asymptomatic infection. After leaving the class, a fraction of individuals develop asymptomatic infection (enter class), whereas the remaining fraction develop symptomatic infection (enter class). Asymptomatic infection never progresses to more severe stages. The rate of recovery from asymptomatic infection is . Asymptomatically-infected individuals may transmit to others at rate . The original sliders that control the fractions of infections that are mild vs severe vs critical now have the interpretation as being the fraction of symptomatic infections that enter each of these stages. The model now also includes the possibility that exposed individuals who have not yet developed symptoms may still be able to transmit the virus (“pre-symptomatic transmission”). To model this, there is a division of the class into two separate classes, (no symptoms or transmission) and (no symptoms but can transmit). The rate of exit from is and from is . Now, there is a scope to include the option for seasonality in the transmission rates. All transmission rates are modified by a factor where is the relative amplitude of the seasonal oscillations and is the phase, and determines the time (in years) of the peak in transmission relative to the time the simulation starts. The values of the user inputs for the transmission rates are interpreted as the rates at time zero of the simulation. This input will be equal to the peak transmission if as the minimum transmission of if and as the time-average transmission if for example. Therefore, the updated model system of SARS-CoV-2 is obtained as follows:

| (2) |

In this paper, investigation scenario on population dynamics of coronavirus across the globe has been studied. The manuscript is organized as follows: mathematical simulations of epidemiological model and its properties are discussed in Section 2. Stability analysis is elaborately discussed in Sections 3. Conditions of bifurcation analysis is studied in Section 4. Properties of global stabilities and globally existing solutions of the model systems are described in Section 5 and Section 6 respectively. Impact of population density along with time is the mathematical key findings. Spatio temporal stability and weakly nonlinear dynamics are studied in Section 7 and Section 8 respectively. Persistence of the model system and extinction properties are discussed in Sections 9 and 10, respectively. Numerical simulation is described in Section 11. Effective measurement on controlling the disease is discussed in Section 12. Lastly, conclusion and future works are described in Section 13.

2. Mathematical simulations

The interesting part of observation is switching active number cases into close term. Assuming the active number cases, follows the growth model at an exponential rate such that . Practically, the dynamical growth is more critical whereas in a brief duration of time, the model system with exponential growth rate can provide a feasible approximation. In both sides by consideration of natural logarithm, yields which exhibits of fitting linear regression of associated to . The slope of this fit indicates the estimation of the intrinsic growth rate, . Doubling time represents an instinctive measurement of the growth rate of population. It has been reported that the number of days for the population to double in size and is calculated by setting yielding . Public health interventions are firmly aimed at the reduction of virus transmission and also in the lightening the growth of the number of active cases. The earliest indications of intervention success will manifest in lowered growth rates.

2.1. Epidemic Growth Rate

Early in the epidemic, before susceptible are depleted, the epidemic grows at an exponential rate which can also be described with doubling time . During this phase all infected classes grow at the same rate as each other and as the deaths and recovered individuals. The cumulative number of infections that have happened since the outbreak started also grows at the same rate. This rate can be calculated from the dominant eigenvalue of the linearized system of equations in the limit that . During this early exponential growth phase, there will be a fixed ratio of individuals between any pair of compartments. This expected ratio could be used to estimate the amount of under reporting in data. For example, all deaths are reported, but that some mild infections might not be reported, since these patients might not seek healthcare or might not be prioritized for testing. These ratios have expected values under the model for a fixed set of parameters. They can be calculated by finding the eigenvector corresponding to the dominant eigenvalue for the linearized system described above. Ratios that deviate from these values suggest either under reporting of cases relative to deaths, or local differences in the clinical parameters of disease progression. The expected ratios are as follows:

2.2. Well-posed system

Theorem 2.1

The unique solutions of system (1) with satisfying initial conditions have been defined as follows:

(3) where .

Proof

Unique solutions of (1) undergo the method of calculus directly with satisfying the initial criterion that become the set of solutions of (3). □

2.3. Basic Reproductive Ratio

Basic Reproductive Ratio is termed as . The basic idea is that is the sum of the average number of secondary infections generated from an individual in stage and the probability that an infected individual progresses to multiplied by the average number of secondary infections generated from an individual in stage . The value of for the system (1) is as follows:

where Total population size (constant).

Similarly, the value of for the system (2) is as follows:

3. Stability analysis

The study has been carried out to find all the feasible solution of any ecological dynamical system. The best possible definition belongs to the context of the environment. In the environment the main idea of stable neighbourhood and the domain of attraction are represented by dynamical system [56]. When a system is stable for a very small oscillation then it is called the local stability of that system and the system will be globally stable when there exist only a unique equilibrium point in the whole domain of attraction. At first, a model has been considered based on some realistic situation. Afterwards linearisation of the equilibrium points for their stability analysis is investigated. For global stability, the theory of Lyapunov stability is thoroughly utilized in mathematical modeling.

3.1. Properties of fixed-point

Here, all equations of L.H.S. of the model system (1) are equating to zero value. It is assumed that all parametric values are positive and we observe the case of fixed-point without disease i.e. so that following condition is satisfied:

| (4) |

where which is termed as the fraction of death of (1). With small perturbation such as at the fixed point results the emergence of exposed individual as follows:

| (5) |

Incorporating, the value of (5) into (1), we obtain,

| (6) |

which indicates instabilities at the point of (5). Therefore, this phenomena suggests that the characteristics of the dynamical system (1) goes away from the point of (5) towards the decreasing case of susceptible individuals, which is the cause of increasing infected population. Thus using the properties of eigen values, dynamical properties of the stability analysis of infectious disease has been investigated during an outbreak in the next section.

3.2. Stability properties during outbreak

During the initial stage of the pandemic, the infected individuals has been observed in lesser numbers with respect to the entire population. Consider, there are hundred thousand people who belong to infected or exposed population of a country and the number is huge corresponding to health care capacity system of any developed country around the world [6]. However, the countries having more than 100 millions or 1 billion population, the ratio of the infected or exposed population (100,000) and the total population comes down 0.1 or 0.01 respectively. Thus in the initial case of spreading the disease, one modification of the model system (1) is added by considering the susceptible cases as constant and therefore with fixing the other parametric values of the system (1). Therefore the above consideration of less percentage of infected or exposed individuals suggests that the importance of the entire population is not much significant during the outbreak of pandemic [21] and the model system (1) becomes

| (7) |

Assume that . Now (7) is rewritten in the following form:

| (8) |

whereas represents as matrix corresponding to the R.H.S. of (7). After the row operation of the matrix the characteristics equation becomes,

| (9) |

where are associated eigenvalues and . The following eigenvalues are obtained,

| (10) |

Now by observation, it can be easily said that all eigenvalues are real and . Eigenvectors associated to the eigenvalues are given below:

| (11) |

whereas and represent arbitrarily constant parameter value. Now the solution’s general formation associated to the state variables as a sum of exponential components corresponding to their rates of exponential and eigenvectors can be written as follows:

| (12) |

Since the critical infected individuals are more prior than non-critical infected population hence with some algebraic calculation and depending upon initial value, for example the exposed and critical infected population are given as:

| (13) |

It is clearly visible from the system (1) that if the rate of infected individual does not become zero i.e. then it is not possible to control the death rate of the population. From the above calculation it is observed that the dominance nature of eigenvalue plays a crucial role in the stability of the system (1) and this suggests a full control on the death population from the disease.

Theorem 3.1

The necessary and sufficient criterion on stability of the system(1)is.

Proof

Necessary and sufficient condition of stability of system (1) is Hence the theorem is proved. □

Remark 3.2

3.1 suggests the condition on controlling the death toll from the disease SARS-CoV-2.

Moreover, if the above theorem is not satisfied i.e. implies total cases of exposed and infected population grow at exponential rate corresponding to the eigenvalue . Here, parametric values of the system (1) are fixed and the rate of infection increases at an exponential rate towards a point where linear estimation does not maintain properly.

Remark 3.3

In real world practical problem, this situation represents corresponding to an exponential outbreak of an epidemic i.e. which indicates the instability about the system. If this continues without imposing lockdown and self isolation or home quarantine, not maintaining social distance and wearing mask in public places then exponential growth on number of infected individuals has been observed to a certain level at which an effective portion of individuals is infected.

Theorem 3.4

The necessary and sufficient criterion on stability of the seasonality outbreak for the system(2)isandwhere

Proof

Similarly if the same process will be followed as above, three eigenvalues of the system (2) are obtained such as and 0 respectively. For rest of the eigenvalues of the system (2), Routh-Horwitz criterion is applied. Thus, the characteristic equation becomes

(14) where,

Thus, from Routh-Hurwitz criterion [15] we have the matrix

According to the Routh-Hurwitz criterion the system (2) is stable if and . □

4. Bifurcation Analysis

Bifurcation analysis illustrates the qualitative behaviour of any dynamical system and so bifurcation theory of the equilibrium points of model systems is described. There is an explanation of Hopf bifurcation [26], which satisfies the presence or absence of a periodic orbit by a change which is local in the stability properties of a fixed point where endemic equilibria exchanges its stability. In Hopf bifurcation the dynamical system switches its stability and a periodic solution arises and this point is called the critical point.

4.1. Hopf bifurcation

On the basis of Poincar-Bendixson theorem, in this section we analyse the existence of limit cycle.

Theorem 4.1

(Poincar-Bendixson theorem)[27]. Letbe a simply connected subset ofandis a flow on. Suppose that the forward orbit of someis contained in a compact set andcontains no equilibrium points. Thenis a periodic orbit.

Consider as bifurcation parameter of the system and statement of the Hopf Bifurcation Theorem is as follows:

Theorem 4.2

(Hopf bifurcation theorem)[28]. Ifare continuous functions ofinsuch that the characteristic equation has

(i) a pair of complex eigenvaluesso that they become purely imaginary at

(ii) the other eigenvalue is negative atthen a Hopf Bifurcation occurs around the endemic equilibrium at.

Theorem 4.3

The system(1)witnesses a Hopf bifurcation ifwith satisfying the conditionaround the endemic equilibrium at.

Proof

It directly comes from the Eq. (9). □

Remark 4.4

From Poincar-Bendixson theorem (4.1) and (5.1), there exists an unique limit cycle.

Remark 4.5

The same process will be followed as above from the Eq. (14) for the occurrence of Hopf bifurcation for the system (2) where as bifurcation parameter around the endemic equilibrium point of the system.

5. Properties of global stabilities

If a dynamical system returns from any starting point to the equilibrium point of the system and the whole domain of attraction contains only a unique equilibrium point then the system is called globally stable which implies the dynamical system’s attracting basin of trajectories is either the space of state or a particular region in the space of state, which is defining the domain of the variable of state of the dynamical system. It is a form of asymptotic stability. The global stability of the endemic equilibria of the systems (1) and (2) are described as follows.

Theorem 5.1

System(1)is globally asymptotically stable at endemic equilibrium point.

Proof

Let be the endemic equilibrium point. The proof of the theorem will be followed by using a Lyapunov function. Now, upon consideration of positive definite function as

Thus collecting positive terms together and negative terms together from the above

where,

Thus if for then has been obtained noting that if and only if and . Therefore, the largest compact invariant set in becomes singleton set of the endemic equilibrium of system (1). Thus, by LaSalle’s invariance principle [27], it implies that the system (1) becomes globally asymptotically stable at endemic equilibrium point if . Hence, the function represents a Lyapunov function, which belongs to the interior of the positive octant. Therefore, the endemic equilibria in the positive octant is globally asymptotically stable. □

Theorem 5.2

System(2)is globally asymptotically stable at endemic equilibrium point.

Proof

The same process will be followed as Theorem 5.1. □

6. Global existence of the solutions

Let be Hilbert spaces and a continuous nonlinear operator. One can try to obtain the solution of the operator equation given noisy data satisfies the condition Let denotes the exact solution. Here the usual norm is considered. In the generalization to the nonlinear case, the study of Tikhonov regularization is investigated with the related schemes more precisely, which will be discussed in the following.

6.1. Tikhonov regularization

Tikhonov regularization leads to the minimization problem

where is initial guess value of and is regularization parameter.

The mapping

| (15) |

is said to be nonlinear Tikhonov functional. In linear case, let us assume that

For there should be an identical solution of (15) and there are more than one global minimizer of (15) in the case of .

6.2. Analysis of Weak Convergence in Hilbert Spaces

Definition 6.1

In Hilbert space be a sequence which converges weakly to if

It is denoted by .

Lemma 6.2

is a linear operator. is defined as weakly continuous if suggests as

Proof

Let Assume that for any one can obtain

□

Lemma 6.3

If then It is called weak lower semi-continuous.

Proof

Since as By the application of Cauchy-Schwarz inequality property, it satisfies

It follows the statement. □

Theorem 6.4

Each bounded sequence has a subsequence which is weakly convergent.

Proof

Consider is a sequence which belongs to with

Let and assume that be an complete orthonormal system in is a bounded sequence which consists complex numbers, then a subsequence which is convergent. As it is defined the bounded sequence is there exists a subsequence of which is termed as such that becomes convergent sequence. If the above technique is followed, a subsequence is derived, namely, such that becomes convergent and one can have a subsequence of which is termed as Now a sequence is observed such as and its diagonal entities possesses the characteristics such that the sequence is going to converge to as Here, define be an element of associated to the condition . It satisfies

Now the aim is to show that Since it is sufficient to consider that Let and choose such that Then such that

Now from the application of the Cauchy-Schwarz and triangle inequalities, it satisfies

□

Definition 6.5

is said to be weakly closed set if all the weak limits of weakly convergent sequences are contained in .

Assume be an operator and is said to be weakly closed if its graph be weakly closed in implies if and such that . It is notably that if the conditions such as be weakly closed and is weakly continuous satisfy that is weakly closed. Hence the consequences of weakly closed are obtained in the following:

Theorem 6.6

Letis a linear subspacewhich is closed. For everya uniqueexists such that,

Thenis called the best approximation toin

Remark 6.7

If is the unique element of then it satisfies

Remark 6.8

Extension of Theorem 6.6 suggests if be closed and convex. Now we change the Remark 6.7 as follows:

Theorem 6.9

is called weakly closed ifbe closed and convex.

Proof

Consider a sequence in which is weakly convergent to From the remark of 6.8, best approximation property satisfies for to in holding the following condition:

Substituting and taking the limit shows that Therefore particularly . □

6.3. Analysis of Convergence

Theorem 6.10

Tikhonov functional (15) possesses a global minimum if is weakly closed for all .

Proof

Assume . Now consider be a sequence of such that

(16) Since then the sequence be bounded. Therefore from theorem (6.4), we obtain a subsequence which is weakly convergent associated to a weak limit . Furthermore, a bounded sequence is derived from (16). Hence, weakly convergent subsequence has been obtained. Since is weakly closed, this suggests as . Now using Lemma (6.3), the following inequality is derived,

Therefore, be termed as global minimum of the Tikhonov functional and we yield globally existing solution. □

Global Existence Theorem (GET)

Theorem 6.11

If the model system (1) is convex, then the system has always globally existing solutions.

Proof

Let us consider that . Here we are going to prove that model system of (1) is semi-positive definite. Here denotes Hessian matrix. Let us denote the following algebraic functions as follows:

Our aim is to show that is convex by using Hessian matrix of is semi-positive definite. i.e. After some algebraic rearrangements and calculations, the following relation has been obtained

(17) Repeating similar techniques for the functions and the following relations have been obtained

. Therefore the functions and are semi-positive definite and thus these functions are convex. This implies that the model system of (1) is convex. From the Theorem (6.9) and (6.10), it follow that the non-spatial model system of (1) has globally existing solution. Hence the theorem is proved. □

Remark 6.12

To get the globally existing solutions for the model system of (2), the same process will be followed as above.

7. Spatio temporal dynamics

Here, Turing instability of the model system of (1) has been discussed. The investigation on spatially and non-spatially Turing patterns are illustrated with providing elaborate calculation of Turing analysis. In this section, we mainly focus on then relation of exposed and infected individuals during the outbreak of the epidemic (susceptible cases consider as constant ) in spatio temporal domain. The stability conditions around the point with and without the diffusion parameters has been described. Incorporating diffusional parameters, the following system of reaction-diffusion equations have been obtained:

| (18) |

where and are diffusion constants of () respectively and . According to the properties of fundamental differential equations [28], unique solutions such as of the system (18) have been obtained with above initial conditions.

Our primary object is to linearize the model system (18) around the homogeneous steady state which depends on time and space. Thus the equations have been obtained as follows:

| (19a) |

| (19b) |

| (19c) |

where and . Usually, consider

where for represent the associated amplitudes, the wave number is denoted by the perturbation growth rate is defined by at time and the spatial coordinate is termed as . Putting the values of (19) into (18) including higher order nonlinear terms are ignored, the characteristic equation is given as

| (20) |

where

| (21) |

Here, J represents the Jacobian matrix of the model system (18) and be a identity matrix. With non-triviality condition of the solution of (20), the following condition is obtained

which suggests a relation of dispersion [30]. Now the stability domain corresponding around the coexistence equilibrium is calculated and a cubic polynomial function is obtained. After rewriting the dispersion relation that is given as

| (22) |

with coefficients

From Routh-Hurwitz criterion, the condition of stability domain around at the equilibria point of (18) is for the real part of the eigenvalue is negative i.e. Re and the condition is valid iff the following properties are satisfied:

| (23) |

With the infringement of the above mentioned conditions indicates about the instability (i.e. ) of the system (18). Now the perturbation of the system around the homogeneous steady state is occurred and investigated the stability condition of the system (18) in the presence of diffusion coefficients and without the diffusion coefficients with respect to certain value of . The conditions are given as follows:

where the assumptions are made that is real and positive nonetheless may be complex valued. Nature of this phenomenon is stated as diffusion driven instability [30]. The stability conditions without the presence of diffusion coefficients of the systems (18) are given as follows:

whereas in the presence of the diffusion coefficients (), the instability around the homogeneous steady state is observed and this phenomena can be studied from the coefficients of (22). To obtain the unstable condition of the model systems (18), at least one of the signs of (23) has to be reversed. Due to this reason, one has to elaborately investigate . Irrespective of the value of the value of should be positive as remains negative. Thus the conditions to ensue the diffusion driven instability of the model systems (18) are given as follows:

| (24) |

General form of both the above mentioned functions are form of cubic equation of which is given by

The standard form of the coefficients of are stated in [30]. Here we calculate the minimum of which defines the minimum value of Turing point () so that the value of for the condition either or is negative for some . This happens only when

which is solved for and we get

which confirms that is positive real valued so that the condition occurs and from which it satisfies either

| (25) |

which assures,

Therefore if at

| (26) |

Therefore the conditions (25)-(26) confirms its necessity and sufficiency to generate pattern formations around the coexistence equilibrium point in the domain of diffusion driven instability. Also to exhibit stability when and should be positive for each case.

Now incorporating the 1-D diffusion means we replace or into in the model system of (18) where and are termed as diffusive parameters of respectively and with prescribed Neumann boundary conditions whereas domain the following mathematical reaction-diffusion equation is derived as follows:

| (27) |

Theorem 7.1

Consider the model systems of(18)with incorporating one dimensional diffusion, and its Jacobian matrixof reaction terms, mentioned in(21). Consider a parameter set for whichis stable, whilst the conditions(25)-(26)are satisfied. Then there exists diffusion coefficientssuch that the steady state of spatially homogeneous pointmay become unstable because of Turing instability.

8. Weakly nonlinear analysis

The model system (18) shows a major slow down around Turing bifurcation parameter. The eigenvalues of the model system (18) are approaching to zero as bifurcation parameters are heading to Turing bifurcation parameters. In this dynamical state, the system (18) exhibit Turing patterns [72] with active slow modes [1], [5], [29], [63], [70], [71]. Theoretical analysis of these patterns are illustrated by amplitude equations, that is explained by the study of weakly nonlinear analysis. Here multiple-time scale [12], [17], [59] analysis is used to derive amplitude equations of the model system (18). are different types of modes corresponding to the Turing patterns associated with an angle of within each pair, which satisfy the conditions as follows and For the sake of easy calculation, and are considered. The solution of the model system (18) is expanded as follow:

| (28) |

where is the eigenvector of the linearized operator. and conjugate are the amplitudes associated with the modes and respectively. Consider the system (18) and it is written as follows:

| (29) |

where

Now the aim is to linearize the system (29) with the application of Taylor’s series formula and the results have been derived as follows:

| (30) |

Therefore the formulation of system (30) is derived as follows:

| (31) |

whereas,

| (32) |

| (33) |

and

| (34) |

Here for the system (18), the control parameter or the bifurcation parameter is termed as . Now the expansion around the Turing threshold constant has been investigated and the mathematical relation has been obtained as follows:

| (35) |

such that,

| (36) |

| (37) |

Here, are termed as system’s time scales.

| (38) |

Next the aim is to linearize each and with applying the expansion of Taylor’s series formulation around the point and following equations are derived,

| (39) |

where, and are the value of and at respectively and and at [Here we denote ].

Applying the Taylor’s series expansion and using the technique of (39), we can write term as follows:

| (40) |

where

| (41) |

and

| (42) |

and are terms associated with second and third order of of nonlinear term mentioned as After the linearisation of the operator of (31) at the point the operator is formulated as follows:

| (43) |

where

| (44) |

and

| (45) |

At with the entities of are written as follows:

After replacing the Eqs. (35)-(45) into Eq. (31) and equalising with the corresponding coefficient of following mathematical relationships are obtained:

| (46a) |

| (46b) |

| (46c) |

Since is linear, eigenvector corresponding to the eigenvalue 0 is also linear. Consider the first order of the solution of (46a) can be obtained as:

| (47) |

where, are termed as the amplitude of the mode and c.c. denotes complex conjugate. Applying the solvability condition of Fredholm, R.H.S. part of (46b) should be orthogonal associated to the zero eigenvector of which is defined as the adjoint operator of Therefore we obtain the following equation:

| (48) |

The value of the solution, which is formed as the eigenvector associated to zero eigenvalue of the Eq. (48) is written as,

| (49) |

where, .

By replacing the Eq. (47) into Eq. (46b) and obtain,

| (50) |

whereas, For the sake of easy calculation, the following terms are considered,

| (51) |

From above it is clear that L.H.S. eigenvector associated to the eigenvalue, which is zero, of (49) should be orthogonal to following condition is obtained,

| (52) |

Incorporating the Eqs. (49)-(50) in Eq. (52) and comparing the value of the coefficient of the derivation of the following equations for are obtained as follows:

| (53) |

Now the term is expressed as sum of Fourier series and the mathematical equation is derived as follows:

| (54) |

By replacing the Eq. (54) into Eq. (46b) and equalising the coefficient values of and the following results are obtained for

| (55) |

Incorporating the Eqs. (47) and (54) in Eq. (42) and going through a long algebraic calculation, the Eq. (42) is derived as follows:

| (56) |

where,

| (57) |

Now substituting the Eqs. (47), (54) and (56) into the Eq. (46c) and comparing the corresponding coefficient value of Eq. (46c) becomes

| (58) |

Assume that . Applying the solvability condition of Fredholm to the corresponding Eq. (46c), should be orthogonal associated to left eigenvectors of corresponding to the eigenvalue zero. The following mathematical relations are obtained:

| (59) |

Amplitude equation can be expressed as follows:

| (60) |

Applying above equations all together, the amplitude equations are derived from the Eq. (38) as follows:

| (61) |

whereas,

| (62) |

8.1. Stability Properties of Amplitude Equations

Amplitude equation can be expressed as

| (63) |

together with the properties of same angle of phase whereas mode is defined as where

Now the following relation is obtained from (63),

| (64) |

Taking the real part, one can have

| (65) |

Replacing the value of Eq. (63) in the system of amplitude equations of (61) and taking the consideration of the real part of equations, the mathematical relations are derived as follows:

| (66) |

For the value of value of turns out positive and negative respectively. Now if the positive value of i.e. is considered, then patterns of the system are going to be stable and defined as whereas if the negative value of i.e. is considered, then patterns of the system are going to be stable and defined as . Therefore the following system of equations are obtained from Eq. (66):

| (67) |

From Eq. (67), the stability properties of the amplitude equations are analysed.

Theorem 8.1

The condition for the stability of stationary state isand condition for the unstable iswhere.

Proof

Consider the stationary state is and from Eq. (67), the stability condition is given by, for and otherwise unstable for □

Theorem 8.2

The stability condition of the stripe patterns isand unstable forwhere.

Proof

Assume the stripe patterns is denoted as and it is given by,

Consider Now incorporating the values of in the Eq. (67)(ignoring the terms associated to ) and replacing the condition of the steady state. Mathematical relations are derived as follows:

(68) Now from (68), the characteristic equation for the stability of stripe patterns is obtained as follows:

(69) whereas the corresponding eigenvalues are termed as . Substituting the value of in the Eq. (69) and one can obtain

(70) From above we have and Stripe patterns become stable if the value of all corresponding eigenvalues are negative i.e.

(71) Therefore, from the above it suggests that the stability condition for stripe patterns is and the condition for unstable is . □

Theorem 8.3

The stability condition of the hexagonal patterns isand the condition for unstable iswhere.

Proof

Substitute in Eq. (67) and get,

(72) The value of discriminant of must positive on consideration of real value and it becomes

(73) Assume Now incorporating the values of in the Eq. (67)(ignoring the terms associated to ) and replacing the condition of the steady state. Mathematical relations are derived as follows:

(74) where

(75) Now from (74), the characteristic equation is obtained as follows:

(76) whereas the corresponding eigenvalues are termed as . Following eigenvalues are obtained after calculating the root of the above cubic equation:

(77) Now the conditions of stability properties of the eigenvalues are investigated, say . □

Case 1. :

First incorporate the parameter value from (72) in the value of which is defined as and obtain,

| (78) |

Here the stability condition of hexagonal patterns is explored so that it ensures the other eigenvalues such as must be negative. On assumption, setting and obtain

| (79) |

On simplification of (79), one can get

| (80) |

Hence, the condition of the hexagonal patterns is stable if .

Case 2. :

Here the same technique will be followed as above case and incorporating the parameter value of from (72) in the value of which is termed as and the following relation is derived,

| (81) |

Comparing both the Eqs. (81) and (78), the eigenvalue turns out to be positive. Moreover, parametric values of are calculated and the mathematical relation is obtained as follows:

| (82) |

Again comparing both the Eqs. (82) and (79) and obtaining the Eq. (82) is positive. Hence, in the case of every eigenvalues become positive and that ensures the unstable condition for hexagonal patterns.

9. Persistence analysis

Persistence/permanence is a long terminal process which is very much essential topic to know the exact features of any dynamical system. Biologically, the long term survival of all the individuals of the populations are represented by persistence property where the amount of initial populations doesn’t matter here. Where in mathematically point of view, persistence/permanence of a dynamical system represents the strictly positive solutions of the system which do not have any omega limit points on the boundary of the non-negative cone (i.e., all the trajectories lie in a fixed region which is bounded for any large time ) [16]. Suppose for any we have . Then if holds we can say that is persistent. When all solutions with +ve initial conditions of any differential equation are persistent then the system is also persistent. The most significant part is the peak times of infected population and its repeated nature [76]. The peaks are related to local or global extremum of and . From system (1), we have and . This can be solved by the solution variables . It has been observed that there is many more local peaks of the infected population over the time along with repeated behaviours, which has been noticed in the earlier pandemics such as Spanish flu (1918 pandemic influenza), which had three pandemic waves of infection within quick interval of few months [53].

Definition 9.1

If there exist positive constants and which are independent of the solution of system (1) such that solution of system (1) satisfies

then system (1) is persistent.

Definition 9.2

If there exist positive constants and which are independent of the solution of system (1) such that solution of system (1) satisfies

then system (1) is persistent.

Lemma 9.3

[14]Ifandwhenandwe have

Ifandwhenandwe have

Theorem 9.4

Letbe any solution of system(1), then

then system(1)is persistent.

Proof

Let be a solution of system (1). From the system (1), we have,

(83) Applying Lemma (9.3) to (83), it immediately follows that

(84) Again we have,

(85) Applying Lemma (9.3) to (85), it immediately follows that

(86) □

Now we conclude that from definition (9.1), lemma (9.3) and Theorem (9.4), we have that the system (1) is persistent.

Theorem 9.5

Letbe any solution of system(1), then

then system(1)is persistent.

Proof

Similar process will be followed as above Theorem 9.4. □

Remark 9.6

Over the progression of time, the fatal disease can be repeated pseudo-periodically i.e. coronavirus can return once again in the later seasons of the year or over the years in the worldwide and it becomes into a persistent disease in the long term of period. The amplitude and time gap of the infection peaks totally relies on the parameters of the system (1).

10. Extinction properties

Extinction is a term which occurs when the last individual of any population die, though the efficiency to reproduce and heal could have been ruined prior to extinction. If existing individual is not present till the end of its life time that particular kind of population then the situation ensures the extinction of that particular kind of individual. Also a kind of individual may become operationally extinct when only a small number of that kind of population remains alive in the environment and they have no power to breed for illness, old age, infrequent ordination along huge area, lack of opposite gender population etc. This paragraph mainly illustrates about the extermination conditions of the population. Consider the notation: and Here, assume the following facts: and where and .

Theorem 10.1

Ifthen.

Proof

Choose Then s.t. and . Also it is known that, . Then from the model system (1) one can have,

Hence, . □

Remark 10.2

The progression rate is enough to extinct the exposed populations.

Theorem 10.3

Ifthen.

Proof

Here it is known that, . Then from the model system (1) one can have,

Hence, . □

Theorem 10.4

Ifthen.

Proof

Similar process will be followed as above Theorem 10.3. □

Remark 10.5

The higher recovery rate helps to extinct the infected populations.

11. Numerical simulation

Analytical results of the model systems (1) and (2) are obtained by numerical simulation [18], [22], [31], [49], [52]. The transmission rates are generally impossible to directly observe or estimate. Instead, these values can be backed out by looking at the early exponential growth rate of an epidemic and choosing transmission rates that recreate these observations. The growth of COVID-19 outbreaks has varied a lot between settings and over time. Some values reported in the literature are in Table (1 ), (2 ) and (3 ).

Table 1.

Estimated parameters for COVID-19 clinical progression.

| Quantity | Value |

|---|---|

| Duration of asymptomatic infections | 6 days |

| Duration of pre-symptomatic infctiousness [13], [18], [36] | 2 days |

| Portion of asymptomatic infections [8], [39], [41] | 30% |

| Incubation Period [8], [33], [34], [35], [58] | 5 days |

| Proportion of non-critical infections [32], [69], [73] | 80% |

| Duration of non-critical infections [58], [60], [68] | 5 days |

| Proportion of critical infections [32], [69], [73] | 20% |

| Time from symptoms to ICU admission [32], [74], [75] | 12 days |

| Time from hospital admission to death [19], [34], [58], [75] | 14 days |

| Duration of critical infection [75] | 8 days |

| Time from symptom onset to death [64], [66], [75] | 20 days |

| Case fatality ratio [7], [47], [50], [64], [66], [69] | 2% |

| Serial interval | 8 days |

Table 2.

Observed early epidemic growth rates r across different settings, along with the corresponding doubling times.

| Growth rate r | Doubling time | Location | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 6.9 days | Wuhan | Early January [33] |

| 0.14 | 5 days | Wuhan | Early January [64] |

| 0.25 | 2.8 days | Wuhan | January [51] |

| 0.3 | 2.3 days | Wuhan | January [58] |

| 0.5 | 1.4 days | Italy | February 24 [51] |

| 0.17 | 4.1 days | Italy | March 9 [51] |

| 0.3 | 2.3 days | Iran | March 2 [51] |

| 0.5 | 1.4 days | Spain | February 29 [51] |

| 0.2 | 3.5 days | Spain | March 9 [51] |

| 0.2 | 3.5 days | France | March 9 [51] |

| 0.2 | 3.5 days | South Korea | February 24 [51] |

| 0.5 | 1.4 days | UK | March 2 [51], [62] |

Table 3.

A sampling of the estimates for epidemic parameters.

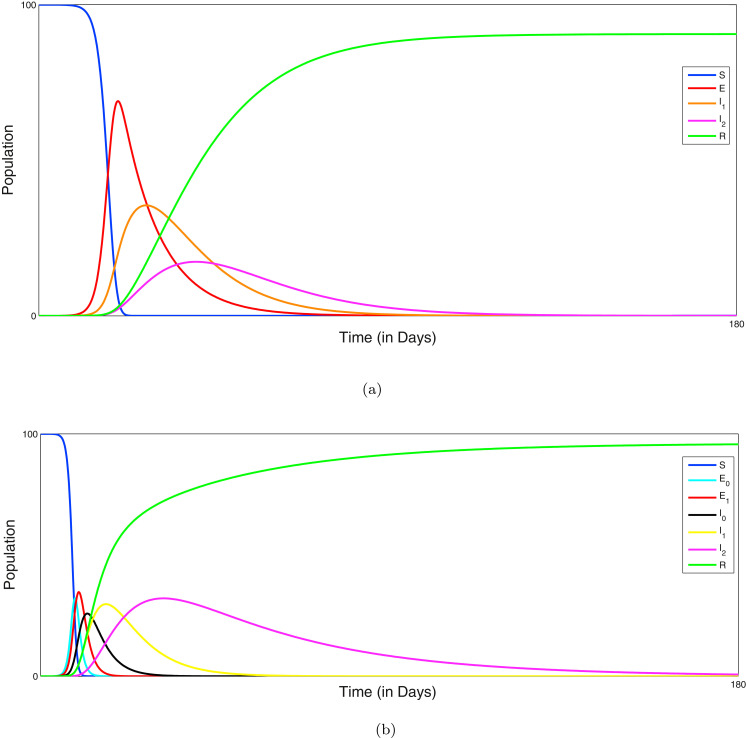

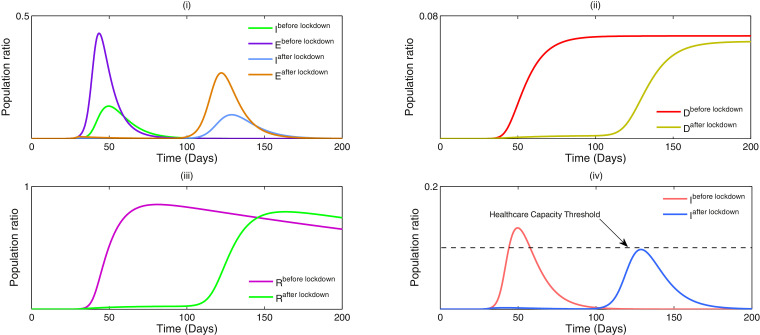

In the Fig. 2 (a), (b), the outbreak of corona virus of the model systems (1) & (2) are illustrated respectively and it has been observed that the lifetime immunity has been developed from this viral disease, so there is no sign of returning cases recovered to susceptible compartment. Here the time span is about six months, from the beginning of the epidemic outbreak. In generally population is initially mostly susceptible (other than for initial cases). Individuals that recover from COVID-19 are subsequently immune. The primary purpose is to explore the dynamics of COVID-19 cases and the associated strain on the health care system in the near future. The outbreak is influenced by infection control measures such as school closures, lock-down, etc. In Fig. 3 (i), the effect of lockdown is illustrated, applied by the government to calculate the infected cases and it gives us a proper idea about the effect of quarantine period and also suggests that the population ratio of infected peaks have decreased after the lockdown period. Here the time period about more than six months is considered. However 3 (ii) indicates the mortality rate does not significantly fluctuate after more than the six months period of lockdown. The main reason of this because of after the lockdown period is over, a fraction of the exposed population can again restart the corona virus spread. In Fig. 3(iii), it is observed that the recovery rate has been increased after the lockdown period and the effect of the significance of this phenomenon plays a major role to fight against COVID-19. In Fig. 3 (iv), it has been investigated that the effect of healthcare system capacity reaches to its threshold point for the model system (1) during the lockdown period. We consider that the dominant source of transmission is from individuals with having non-critical infections who are likely to still be in the community, as opposed to isolated in the hospital.

Fig. 2.

(a) Time series diagram of the model system (1) with the time period of six months. Parameter values of system (1): . (b) Time series diagram of the model system (2) with the time period of six months. Parameter values of system (2): .

Fig. 3.

(i) Simulation of the model system (1) with a lockdown period correspond to the effect of before and after the lockdown. (ii) The effect of mortality rate before and after the lockdown. (iii) The effect of recovered rate before and after the lockdown. (iv) Healthcare capacity system reaches its threshold point at . Parameter values of system (1): . During the lockdown period and are decreased to 0.1 and 0.001 respectively whilst other parameters are fixed. When the lockdown period is over, the value of is increased to 0.4 (more than lockdown period), however remains unchanged as 0.001 which implies that after the lockdown is lifted people remain keep social distance with the infected populations.

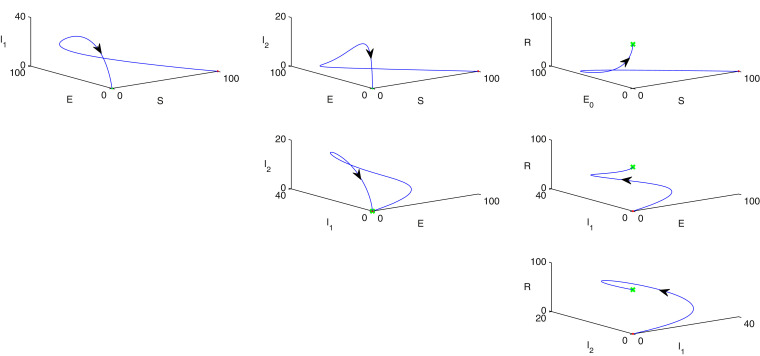

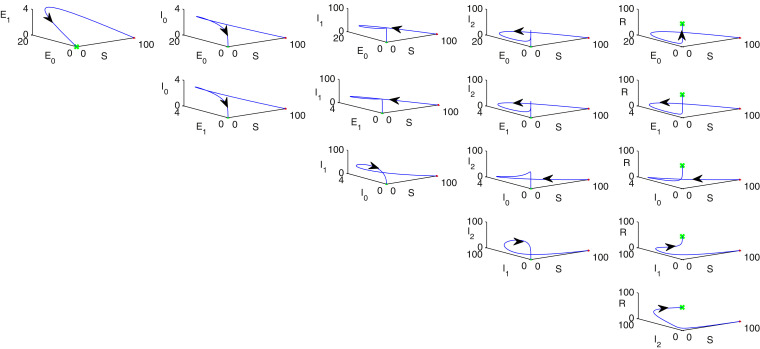

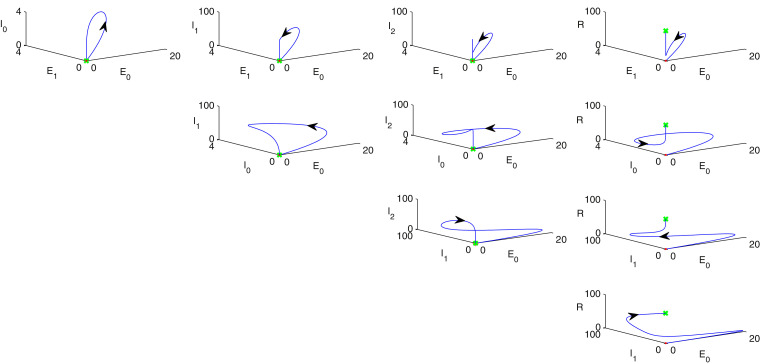

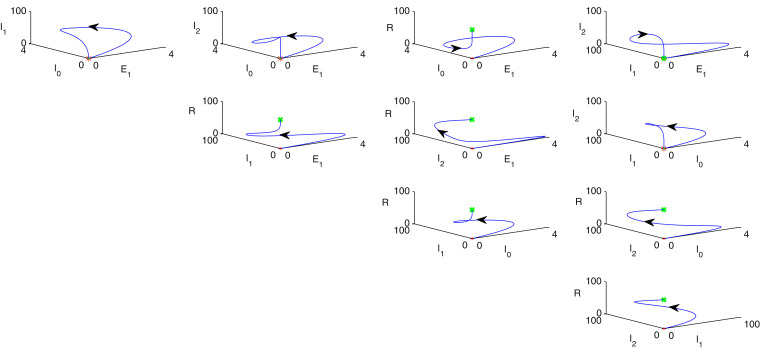

Fig. 4illustrates phase portrait diagram of stability analysis w.r.t. every possible combination of any three individual population of model (1) where red point indicates as starting point and the final destination is marked as green colour. In each column, population in the -axis of sub-figures are same whereas other two population in the rest of the axes are taken randomly. Therefore, taking any three possible population combinations in and axes and the parametric values are given as follows: . Similarly in Figs. 5 , 6 , phase portrait diagrams of stability analysis w.r.t. every possible combination of any three individual population of model (2) are portrayed where red point indicates as starting point and the final destination is marked as green colour. In each column, population in the -axis of sub-figures are same whereas other two population in the rest of the axes are taken randomly. In Fig. 7 , rest of the possible combinations of individual populations of the system (2) for stability analysis is depicted where red point indicates as starting point and the final destination is marked as green colour. Hence, taking any three possible population combinations of the system (2) in and axes and the parametric values are given as follows: .

Fig. 4.

Phase portrait diagram of stability analysis w.r.t. all combinations of the individuals of the model system (1), where red point indicates as starting point and the green point denotes the final destination. Parameters are given in Section 11.

Fig. 5.

Phase portrait diagram of stability analysis w.r.t. all combinations of the individuals of the model system (2), where red point indicates as starting point and the green point denotes the final destination. Parameters are given in Section 11.

Fig. 6.

Phase portrait diagram of stability analysis w.r.t. all combinations of the individuals of the model system (2), where red point indicates as starting point and the green point denotes the final destination. Parameters are given in Section 11.

Fig. 7.

Phase portrait diagram of stability analysis w.r.t. all combinations of the individuals of the model system (2), where red point indicates as starting point and the green point denotes the final destination. Parameters are given in Section 11.

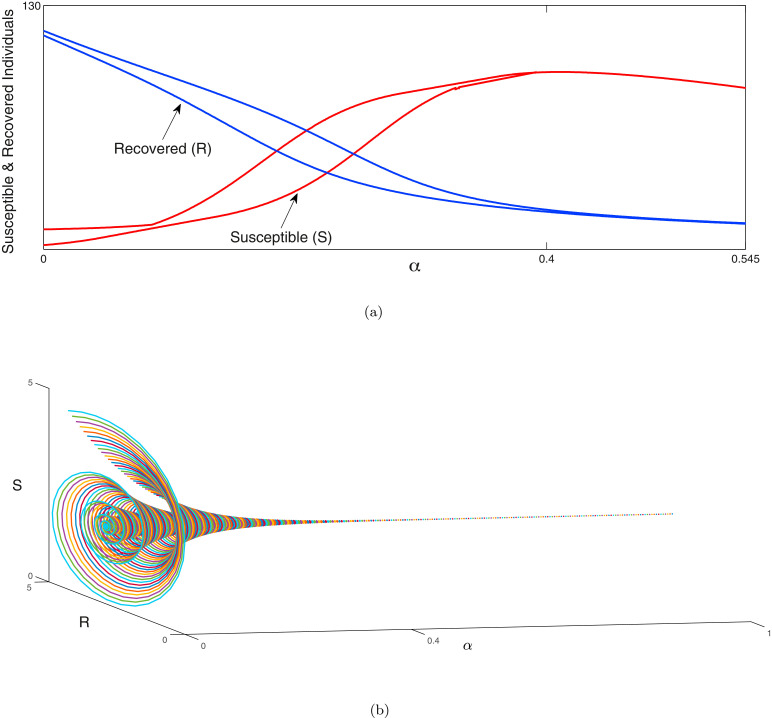

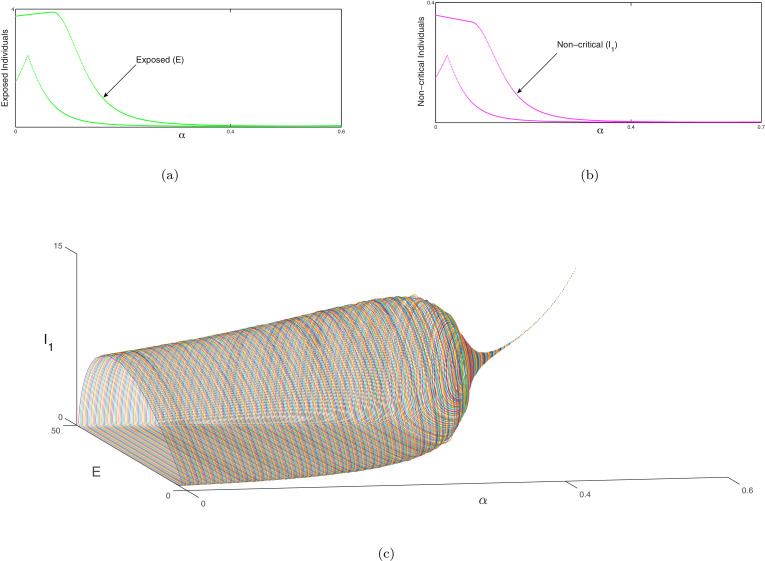

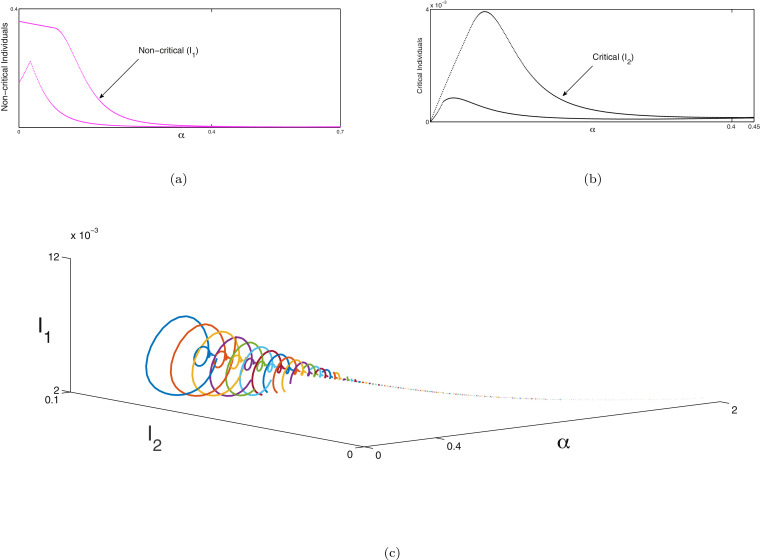

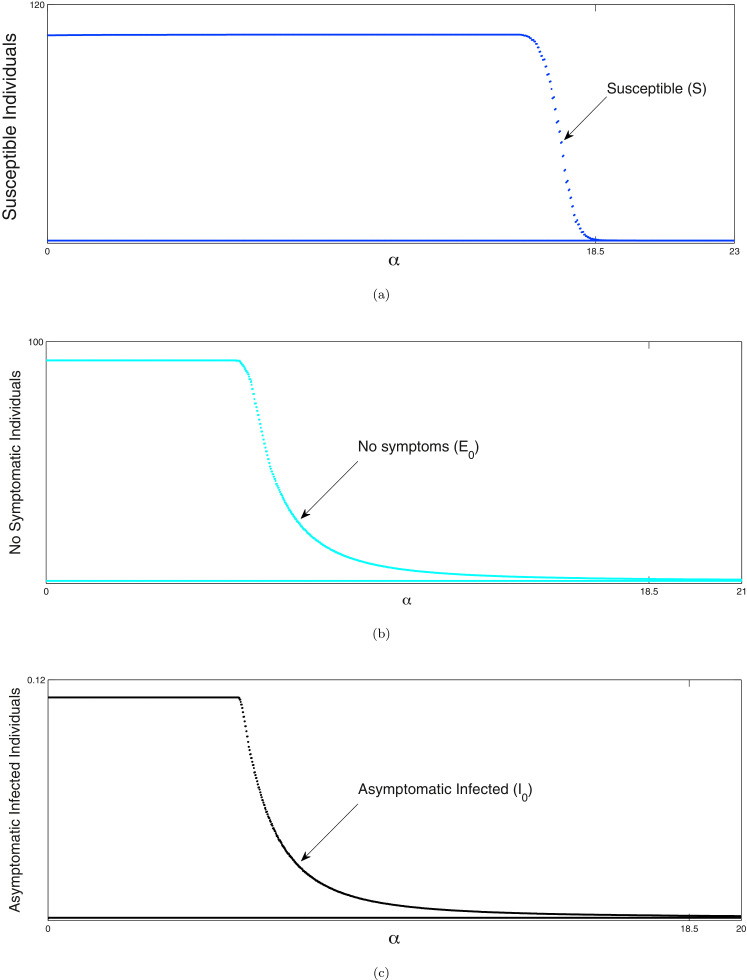

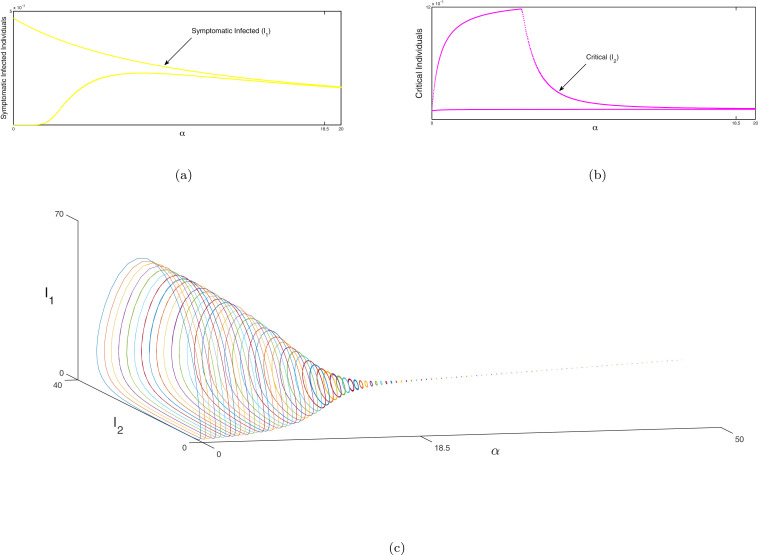

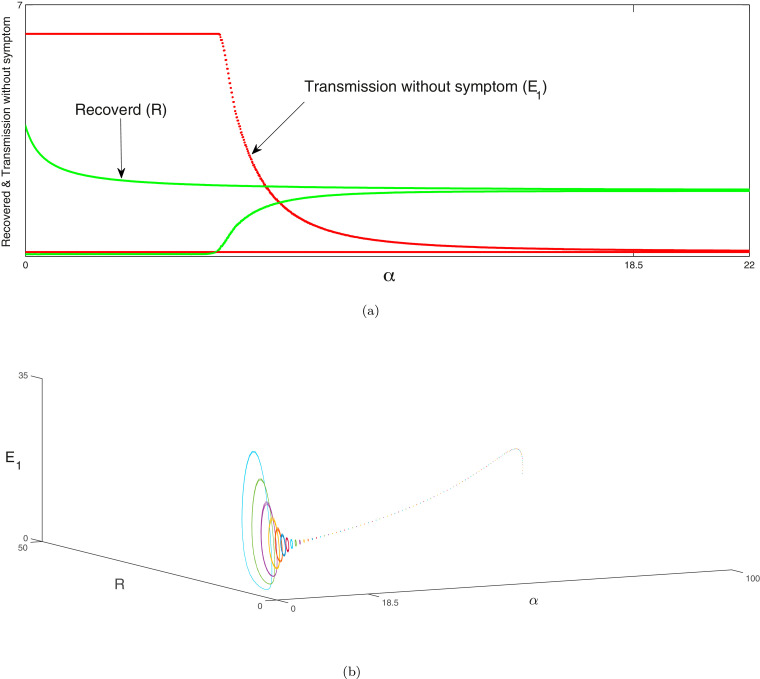

Next the bifurcation analysis between susceptible and recovered individuals is portrayed in Fig. 8 , exposed and non-critical individuals in Figs. 9 (a) & 9(b) and non-critical and critical individuals in Figs. 10 (a) & 10(b) of system (1) with respect to as bifurcation parameter respectively. Red line represents the susceptible individuals, blue line indicates the recovered population, green line denotes the exposed ones, magenta line indicates the non-critical population and black line shows the critical population of system (1). In Fig. 8, Fig. 9 and 10 at a Hopf bifurcation arises. In Figs. 8(b), 9(c) and 10 (c), we illustrate the phenomena of Hopf bifurcation in 3D domain corresponding to the bifurcation parameter to describe the analysis of stable state of the system (1) around the endemic equilibria of the system. In these figures, we observe that the system (1) is unstable when and it is stable asymptotically within . The parametric values are given as: . Similarly, the same process will be followed as above for the system (2) and the bifurcation analysis of susceptible, no symptomatic/transmission and asymptomatic infected individuals are illustrated in Fig. 11 , bifurcation analysis between symptomatic infected & critical infected population are portrayed in Fig. 12 (a),(b) and bifurcation analysis between transmission without symptom and recovered individuals are depicted in Fig. 13 (a). In Fig. 11, Fig. 12 and 13 at a Hopf bifurcation arises. In Figs. 12(c) and 13(b), the phenomena of Hopf bifurcation is illustrated in three dimensional domain corresponding to the bifurcation parameter to describe the analysis of stable state of the system (2) around the endemic equilibria of the system. In these figures, we observe that the system (2) is unstable when and it is stable asymptotically within . The parametric values are given as: .

Fig. 8.

(a) Hopf-bifurcation of susceptible and recovered individuals of system (1) corresponding to the bifurcating parameter . The Hopf bifurcation occurs at around the endemic equilibrium. We illustrate the unstable focus on the range and asymptotically stable on the range . (b) The three-dimensional diagram of Hopf-bifurcation of the system (1) w.r.t. the parameter of bifurcation which is portrayed in 3D space which is . In this Figure endemic equilibria be a focus which is unstable on the range (which is depictured with various coloured cycles) and also the endemic equilibria be a focus which is stable on the range (depictured with the dashed line). A Hopf-bifurcation takes place at . Other parameters are given in Section 11.

Fig. 9.

(a), (b) Hopf-bifurcation of exposed and non-critical individuals of system (1) corresponding to the bifurcating parameter respectively. The Hopf bifurcation occurs at around the endemic equilibrium. We illustrate the unstable focus on the range and asymptotically stable on the range . (c) The three-dimensional diagram of Hopf-bifurcation of the system (1) w.r.t. the parameter of bifurcation which is portrayed in 3D space which is . In this Figure endemic equilibria be a focus which is unstable on the range (which is depictured with various coloured cycles) and also the endemic equilibria be a focus which is stable on the range (depictured with the dashed line). A Hopf-bifurcation takes place at . Other parameters are given in Section 11.

Fig. 10.

(a), (b) Hopf-bifurcation of non-critical and critical individuals of system (1) corresponding to the bifurcating parameter respectively. The Hopf bifurcation occurs at around the endemic equilibrium. We illustrate the unstable focus on the range and asymptotically stable on the range . (c) The three-dimensional diagram of Hopf-bifurcation of the system (1) w.r.t. the parameter of bifurcation which is portrayed in 3D space which is . In this Figure endemic equilibria be a focus which is unstable on the range (which is depictured with various coloured cycles) and also the endemic equilibria be a focus which is stable on the range (depictured with the dashed line). A Hopf-bifurcation takes place at . Other parameters are given in Section 11.

Fig. 11.

(a), (b), (c) Hopf-bifurcation of susceptible no symptom or transmission and asymptomatic infected individuals of system (2) corresponding to the bifurcating parameter respectively. The Hopf bifurcation occurs at around the endemic equilibrium. We illustrate the unstable focus on the range and asymptotically stable on the range . Other parameters are given in Section 11.

Fig. 12.

(a), (b) Hopf-bifurcation of non-critical and critical individuals of system (2) corresponding to the bifurcating parameter respectively. The Hopf bifurcation occurs at around the endemic equilibrium. We illustrate the unstable focus on the range and asymptotically stable on the range . (c) The three-dimensional diagram of Hopf-bifurcation of the system (2) w.r.t. the parameter of bifurcation which is portrayed in 3D space which is . In this Figure endemic equilibria be a focus which is unstable on the range (which is depictured with various coloured cycles) and also the endemic equilibria be a focus which is stable on the range (depictured with the dashed line). A Hopf-bifurcation takes place at . Other parameters are given in Section 11.

Fig. 13.

(a) Hopf-bifurcation of transmission without symptom and recovered individuals of system (2) corresponding to the bifurcating parameter . The Hopf bifurcation occurs at around the endemic equilibrium. We illustrate the unstable focus on the range and asymptotically stable on the range .

(c) The three-dimensional diagram of Hopf-bifurcation of the system (2) w.r.t. the parameter of bifurcation which is portrayed in 3D space which is . In this Figure endemic equilibria be a focus which is unstable on the range (which is depictured with various coloured cycles) and also the endemic equilibria be a focus which is stable on the range (depictured with the dashed line). A Hopf-bifurcation takes place at . Other parameters are given in Section 11.

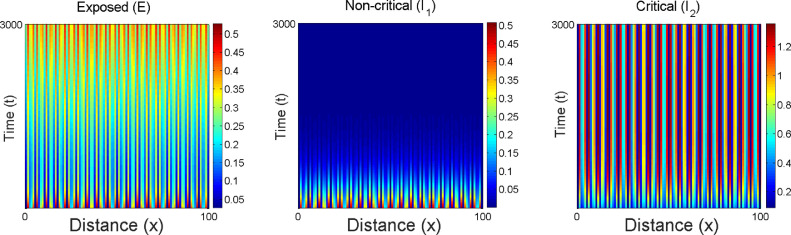

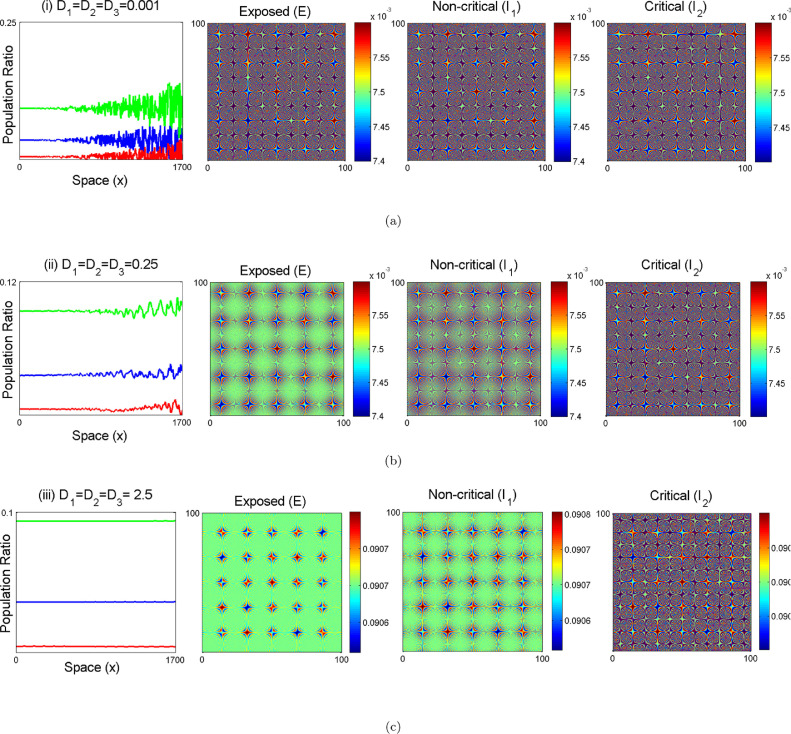

In Fig. (14) , the parametric values of one dimensional patterns for the 1D diffusive model system (27) is considered and explored the numerical results via simulations to portray Turing patterns in the -plane. Hence from theorem (7.1), the instability of Turing pattern is observed in 1D diffusive model system (27) to happen and the numerical result suggests the same in the form of Fig. 14. In the first panel of Fig. 5, one-dimensional solutions of the system (18) are portraited with respect to space. Small spatial random perturbations are made around endemic equilibrium of the spatially homogeneous system. There is a witness of three significant one-dimensional dynamical behaviours such as chaos, oscillatory and stability covering almost all over the domain. In the 2nd, 3rd and 4th panels of Fig. 15 (a) shows chaotic dynamics in the systems. Now, the change in the dynamics of the model system upon increasing the the value of the diffusion parameters is observed. The system (18) exhibits an oscillatory dynamics and are presented in the 2nd, 3rd and 4th panels of Fig. 15(b). Further with the increase the value of the diffusion parameters, the system becomes stable which proves the analytical queries that the dynamical behaviour of a chaotic system is changed to stable dynamical system by sufficiently increasing the value of the diffusion parameters in the 2nd, 3rd and 4th panels of Fig. 15(c). The formations of pattern of the exposed individual non-critical infected population and critical infected ones associated to the diffusion parameters and from 0.001, 0.25, and 2.5 corresponding to every state of the conditions from chaos to the stability of the system (18) is depicted in Fig. 15. Spatial patterns of the model system (18) is illustrated around the endemic equilibrium point in Fig. 15. It is clear that the changes in the stability domain of the model system certainly visible after incorporating the diffusive parameters in the model system. The dynamical behaviour of the system (18) is investigated around the coexistence equilibrium point with small changing in the boundary conditions by keeping the parameters fixed and changing the time and diffusive parameters. The pattern formations is illustrated to investigate the dynamics spatially of the model system (18) and initial criterion are represented as where and are uniformly distributed random numbers which lie between with the parametric values are given as follows: .

Fig. 14.

Snapshots of spatial Turing pattern formations of 1D diffusive parameter w.r.t. the evolution of time of exposed non-critical infected and critical infected individuals over xt-domain of the system (27) have been portraited. Time, has been considered. Perturbation around the endemic equilibria has been considered by .

Fig. 15.

One-dimensional numerical solutions of population ratio with space series and snapshots of contour pictures of the time evolution of exposed non-critical infected and critical infected individuals in the -plane of the diffusive model (18) for different values of diffusion parameters (a) (b) and (c) incorporating the effect of diffusion parameters and of the system (18). Here, Blue line describes exposed population, Red line denotes non-critical individual and Green line indicates for critical population.

12. Discussion

Some recent reports have suggested that healthcare workers are disproportionally infected with COVID-19, suggesting there is some role to hospital-based transmission (e.g. from individuals in infected state, or individuals who are hospitalized with only mild infection). In China, approximately 5% of all infections were in healthcare workers [65], and in Italy the number is currently around 10% [65]. One of the biggest dangers of a widespread COVID-19 epidemic is the strain it could place on hospital resources, since individuals with critical infection require hospital care. The critical stage of infection requires mechanical ventilation, which is ICU-level care. Individuals with non-critical infection do not require hospitalization, and could recover at home on their own or can be treated in a regular hospital ward. However, in many countries these individuals have also been hospitalized, likely as a way to isolate them and decrease the transmission rate, as well as to observe them for progression to more aggressive disease stages. In recent studies on COVID-19, it has been noticed that nearly all individuals included had symptoms, since the presence of symptoms was used to determine whether someone would be admitted for a test of COVID-19. However, it is possible that some individuals may be infected and be able to transmit to others without developing symptoms. The model also suggests the possibility of pre-symptomatic transmission. In general compartmental epidemiological models assume that the onset of symptoms and the onset of infectiousness coincide, but recent evidence indicates that symptoms may be delayed relative to when an individual is infectious. Viral loads are measured over time in symptomatic individuals, studies show that they are at a peak on the first day of symptoms, suggesting that they were already high before symptoms started [68]. Detailed contact tracing studies that have tracked transmission chains where the infector and the infectee are both known have found the serial interval, which is the time between symptom onset in the infector and infectee, is sometimes less than the incubation period. This means there must be pre symptomatic transmission. A wide range of values for the proportion of all transmission that is pre-symptomatic have been estimated so choose an intermediate value of consistent with [36]. A related line of evidence for the presence of pre symptomatic infection is that the average length of the serial interval is quite close to the average length of the incubation period in a few studies. This suggests either a very short symptomatic and infectious period, or, significant pre-symptomatic transmission. Undetected cases of COVID-19 are the primary incertitude of this pandemic. COVID-19 is new and it has not been observed before as a result, massive number of infected populations are registered day by day in the globe. Effectively, it is impossible for a country to diagnose all the active cases of COVID-19. So naturally the number of active cases always remains less than the actual cases in the country. This can be described the non-detected cases in two categories such as undiagnosed and undetected. Undiagnosed individuals are considered as the infected individuals whose symptoms are yet to visualize and they will come under diagnosis very soon. Undetected individuals never come under the scanner of treatment as they are having mild symptoms. A delay has been noticed between the time period of infection and treatment. If somehow one can able to know about the time period of the delay then one can capable to investigate about the number of undiagnosed individuals. The most significant time of the delay is the infection’s incubation period of time which can be mathematically modeled with the help of probability distribution, termed as incubation distribution. In general the average period of incubation is between five to six days. It is been observed that the infections with 95% of cases have maximum period of incubation time is twelve to thirteen days. Recovered COVID-19 patients have immediate immunity strength. Initially the objective is to analyse the characteristics of COVID-19 cases and the corresponding strength of the medical care system. The prevalence of this disease is caused the educational institutes to shut down, lockdown policies to implement of a region, stop airlines from flying, making social distancing etc. so that the spread of infection rate can manage to control. We show that these policies can give impactful results in the controlling of the pandemic by synthesizing the parameter data. Most of the countries will witness a recurrent of maximal pandemic scenario in the globe if possible. However, the pandemic situation will slow down if the lockdown policies are implemented perfectly in place. Otherwise we are going to face another repeated scenario of the outbreak of the disease will take place. Therefore the conclusion is that another phase of coronavirus possibly hit in the globe for neglecting above preventive policies. So this would be a case of alarming situation. Also studies suggest that how novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) might spread between different age of people and the impact of this situation directly reflects to the healthcare system worldwide. Due to COVID-19, the infected older individuals are either hospitalised or died and the infected young ones may have asymptomatic infection. So the young individuals recover much faster than the adult ones and it seems to look through that young individuals became more susceptible from infection rather than adult individuals [22], [31], [40]. Everyday analysis of the COVID-19 in the populations is registered a larger section of infected individuals. To control this epidemic, government has to impose lockdown situation so that the effectiveness of the virus spreading is delaying over the time and the peaks of the infected population becomes minimize. However this process is insufficient for a long term of period. Social distancing, effectiveness of quarantine, less crowd gathering are most feasible conditions to become the zero contaminated zone for a longer period of time. Mathematically the whole situation is investigated in this manuscript. Some effective proposals have been offered to control this fatal epidemic disease in the followings:

12.1. Effective proposals to control the epidemic disease

Embed maximum lockdown of the entire population in the country, send to quarantine of the infected cases, impose home isolation of the asymptomatic cases (rest of the people who are not infected) and look after in the application of these above-mentioned cases as soon as possible.

Figure out the number of exposed cases and distinguish the level of their infectiousness.

Maximal lockdown remains until as many of all the number of estimated exposed cases are calculated.

Lift the lockdown and apply strict social distancing upon economic conditions.

Back to normal life if there are no new cases have been registered for a long period of time.

Select a state as a model state and apply all the above regulations and observe the effectiveness if results will fruitful then apply the regulations in whole country.

13. Conclusion and future work

In this paper, the characteristics of the pandemic disease has been investigated from mathematical approach via compartmental model with seasonality transmission of the infectious disease. The stability analysis of the model systems at the fixed point is illustrated and observed the mathematical interpretation of the global stability. In many countries it has been noticed that with limited test kits, medication, hospitalization, excessive fatigue or mortality of the healthcare personnel, economic breakdowns, etc. cause health-care system to reach its threshold capacity. This situation looked as worst case scenario for pandemic strategies. Now the situation becomes more worried as there are observed instability in the community since the outbreak of such pandemic is spreading rapidly. Here, are the sufficient criterion, which is directly obtained from the Theorem 3.1. It is clear with the criterion that the individuals which are termed as susceptible are avoiding to get in contact with the infected individuals. Moreover, the application of the other criteria i.e. is a bit more complex in practical life as the exposed individuals are having without any symptoms and this suggests the importance of the requirement of social contacting or distancing. Thus suggests that the exposed individuals can have the permission to travel among infected population without transmitting the disease into new groups and this leads to the consideration of disease free environment of asymptomatic population. With the case of indicates that the individuals with healthy outfit stay away from contacting the infected ones and suggests the recovery rate of non-critical population or the emergence of symptoms is much faster than their transmission rate of the disease. Global stability of the endemic equilibrium point, properties of persistence and extinction criteria during an outbreak of the epidemic for the model systems (1) and (2) are discussed. Also the Hopf bifurcation of the systems (1) and (2) have been illustrated. Moreover, the existence of the solution of the model system is described. Effect of diffusional formations of pattern of the population densities with infected individuals interaction is elaborately investigated and described the recovered cases in spatio temporal area with its dynamical consequences of diffusion parameters of the model system (18). Amplitude equations are used to formulate the general theories of Turing patterns around the bifurcation threshold constant. Moreover, it has been noticed that the theoretical explanation associated to amplitude equations of Turing patterns is failed when the bifurcation constant goes away from the bifurcating threshold constant. Changes with decent variations in the diffusion parameters and of the model system (18) exhibits caricature transformation in the solution of the dynamical systems in one dimension. A certain variation in the dynamics of the systems such as chaos to stability, has been observed with increasing value of the diffusion parameters. The ecological importance of diffusion stands for individual populations are dispersing between sub-populations over global populations and it can relate to the eco-evolutionary process. Indeed the dynamical behaviour of the spatial system is very much complicated and its heavily rely on system diffusive parameters. The pattern structures, depend on initial conditions, remain entirely on the limit cycle over the region and the solution exists in the spatial region over all the time. The main reason of dynamical changes in the model system (18) is a small perturbation on the bifurcation parameter and the occurrence has been described by weakly nonlinear analysis.

Transmission dynamics of coronavirus has been exhibited by bifurcation analysis. With small perturbation of control parameter, the fatal disease is spreading and this phenomena leads to exhibit two limit cycles in which one has the property of stability. Hence, the emergence of reproducible periodicity has been noticed in the transmission of the disease. This suggests the biological importance of perturbation the control parameter and effective proposals should have been taken to control on spreading the disease around the worldwide. Therefore with enforcing lockdown policies and maintaining social distancing, we can sustain the disease for a certain of period (self isolation among asymptomatic population if needed). The repetition of epidemic situation may also happen in the later-half of the season and becomes the disease persistent in the real world in the extended run of our life. The amplitude and time gap of the infection peaks totally relies on the parameters. The higher recovery rate suggests to extinct the infected populations over the time period. Disease spreads into the community for not taking the preventive measures by individuals and causes to form the Turing patterns. The impact of structural behaviour of Turing patterns may turn to chaotic from stability in the homogeneous environment. The resource level becomes low in the spatial heterogeneous environment and the ratio of the spatially homogeneous population is going to the path of extinction. From the point of view of population biology, Turing patterns may lead the model system (18) to the homogeneous steady state in the spatial domain by changing the control parameter and diffusion parameters, which is not an admissible condition in the ecosystem. Spatio temporal dynamics is key to control the biodiversity of the ecology. The condition of human lives are such metastable so that we all need to think as united against the deadly coronavirus and make a way through this such fatal phase unless the parametric conditions, nothing is specified about the coronavirus.

This research work will be carried out in different futuristic perspectives. Especially, comparing to the real world problem by fitting our model over real data and predict the infected and mortality rates under quarantine and vaccination with all possible patterns of the epidemic disease over the progression of time. Confidence intervals have not been considered. However, it would be suggested as future work if possible and to implement this work, one has to use the bootstrapping scheme corresponding to the distribution of infection with the help of non-linear fractional control operator [2], [3]. Here, undetected cases are totally ignored. To calculate those, one has to consider that the death individuals should not be avoided such as undetected cases and to count the cases of community transmission in a dense population with figuring out the mortality rate of the symptomatic cases. As a result, there are a large number of death populations than the registered cases in the countries associated to undetected cases. The estimation of the undiagnosed infected individuals are considered as new cases as their diagnosis completely rely on the previous infection and this would be an another field to work on.

Funding source

There is no funding source in this research.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Saikat Batabyal: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Software, Data curation, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Visualization, Investigation, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest