Abstract

To meet urgent decisional needs of retirement/nursing home residents and their families, our interdisciplinary stakeholder team rapidly developed and disseminated patient decision aids (PtDAs) regarding leaving one’s residence during the COVID-19 pandemic. The development steps were as follows: identify urgent decisional needs, develop PtDAs using the Ottawa Decision Support Framework template and minimal International PtDA Standards, obtain stakeholder feedback, broadly disseminate, and incorporate user feedback. Within 2 wk, we developed 2 PtDAs for retirement and nursing home living environments that were informed by decisional needs (identified from public responses to related media reports), current pandemic regulations/guidance, and recent systematic reviews. Within 3 wk of their dissemination (websites, international PtDA inventory, Twitter, Facebook, media interviews), the PtDAs were downloaded 10,000 times, and user feedback was positive. Our expert team showed feasible rapid development and wide dissemination of PtDAs to respond to urgent decisional needs. Development efficiencies included access to a well-tested theory-based PtDA template, recent evidence syntheses, and values-based public responses to media reports. Future research includes methods for rapidly collecting user feedback, facilitating implementation, and measuring use and outcomes.

Keywords: decisional needs, development methods, dissemination, Ottawa Decision Support Framework, patient decision aid, shared decision making

Introduction

“If you can get your relatives out of seniors’ homes, try to do so as fast as you can,”1 was the headline of a Canadian newspaper on April 2, 2020. At this early phase of the pandemic, the paper reported >600 COVID-19 outbreaks in retirement and nursing homes.1 This evoked significant media coverage and strong emotional public responses, with hundreds of posted comments. By May 25, Canada had the highest proportion of deaths (>80%) occurring in long-term care among 37 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries.2

Because many families were grappling with the decision to temporarily move a resident from a retirement or nursing home during the pandemic, 3 authors (D.S., N.E., A.M.O.) collaborated in early April to determine if a patient decision aid (PtDA) could help families facing this quandary. PtDAs3 make explicit the decision being considered; provide information on options, benefits, and harms; and help patients/families clarify their values for outcomes/features of options. The Ottawa Decision Support Framework is the most commonly used framework guiding PtDA development.4 Its main premise is that decision quality improves when patients’/families’ decision-making needs are addressed.5 Common manifestations of the difficultly in making decisions are feeling uninformed, lacking access to information, feeling unclear about personal values, and feeling unsupported in decision making.6 A systematic review of 24 randomized trials evaluating PtDAs, developed according to the Ottawa Framework, revealed that they were superior to usual care in addressing decisional needs and improving decision quality.7

PtDAs developed according to the Ottawa Framework also meet the International PtDA Standards (IPDAS).8,9 However, PtDA development and evaluation often takes more than 1 y, which is too long to address urgent emerging decisional needs. Our objective was to rapidly develop and disseminate a PtDA to meet retirement or nursing home residents’ and families’ decision-making needs regarding location of residence during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

We designed and used an expedited Ottawa PtDA development process (Table 1). First, we rapidly assessed the urgent need for a PtDA.

Table 1.

Comparison of Prepandemic IPDAS and Ottawa PtDA Development and Evaluation Processes and the Expedited Ottawa Process during the Pandemic

| Prepandemic Process | Pandemic Process | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IPDAS8,10 | Ottawa11,12 Based on ODSF and IPDAS | Expedited Ottawa Based on ODSF and IPDAS | |

| PtDA development process10–12 | |||

| Consider rationale for developing PtDA: initial stimulus, available PtDAs, decision dilemma, numbers affected, practice and preference variation | Explore: initial stimulus, available PtDAs (A to Z PtDA Inventory13) Consult experts and review: practice guidelines, systematic reviews, decision analyses; statistics; practice atlases, patient preference studies |

Rapidly assess urgent need for PtDA: initial stimulus, available PtDAs (A to Z PtDA inventory13); consult available experts and scan readily available information | |

| Define scope, purpose, target audience | √ | √ | √ |

| Assemble steering group: clinicians,a patients,b other experts/stakeholders | √ | √ | Clinicians, senior care administrators, PtDA researchers/developers (no residents included) |

| Design | |||

| •Assess patients’ and clinician’s views on decisional needs | √ | √ Tested assessment methods | 298 public responses to media reports, steering group’s views, a public health official’s statement |

| •Determine format and distribution plan | √ | Used tested Ottawa template | Used tested Ottawa template |

| •Review/synthesize evidence | √ | √ | √ Available reviews, regulations, policies |

| Draft PtDA prototype to meet IPDAS | √ | √ | √ |

| Meet IPDAS qualifying criteria8 (describes condition, index decision, target audience, provides options, positive and negative features, clarifies values for positive/negative features) | √ | √ | √ |

| Meet IPDAS criteria to minimize risk of bias (compares positive/negative features with equal detail; probabilities, if used, compare same denominators; includes developers’ credentials, funding sources, conflicts of interest, date of last update, readability levels, references to scientific evidence) | √ | √ | √ |

| Consider relevant IPDAS quality criteria8,14 (natural course of the condition if no action taken; procedures before, during, and/or after the health care option; describes options’ outcome probabilities using event rates; compares probabilities of options over the same period of time; uses same scales in diagrams comparing options) | √ | √ | √ Procedures involved X Natural course, outcome probabilities unavailable or changing rapidly |

| Field testing (alpha testing) with users who have already made the decision: •with patients to check comprehensibility and usability •with clinicians to check acceptability and usability •review by steering group and revised |

√ | √ | Limited to some steering group members who are potential users as clinicians or as family members who decided for their own families |

| Field testing (beta testing) with users making the decision: •with patients and clinicians to assess feasibility •review by steering group and finalize PtDA and distribution plan |

√ | √ | Limited to 1 steering group member who was currently making the decision with a family member |

| Evaluation of PtDA effectiveness8,10,11 and dissemination | |||

| Evaluation according to IPDAS effectiveness criteria8: evidence PtDA (or one based on the same template): 1) helps people know about available options/features, 2) improves match between features that matter most and option chosen |

√ | √ Effectiveness of Ottawa template shown in RCTs7 Template embeds knowledge test, values, choice, SURE test15 (feel sure, informed, clear about features that matter most, supported) for users and evaluators |

√ Effectiveness of Ottawa template shown in RCTs7 Template embeds choice, SURE test15 (feel sure, informed, clear about features that matter most, supported) for users X No knowledge test as facts are changing rapidly |

| Distribution | √ | On website16 and register in A to Z PtDA inventory13 | Rapid scale distribution on websites, A to Z PtDA inventor,13 Twitter, media Facebook, interviews, organizations |

IPDAS = International Patient Decision Aid Standards; ODSF = Ottawa Decision Support Framework; PtDA = patient decision aid; √= m et; X = not done.

Health care providers who deal directly with patients.

Includes residents of retirement/nursing homes, residents’ substitute decision makers, family members, and others involved in the decision.

Next, we established an interdisciplinary stakeholder team (nurses, social worker, physicians, physiotherapist) with expertise in PtDA development/evaluation (D.S., A.M.O.), care of the elderly (N.E., S.S.), local health governance of seniors’ care (C.L., K.B.), counseling patients/families on care options on discharge from hospital (J.L.), and advising provincial governments on medical management of COVID-19 (P.A., S.S.). Team members had either faced the decision about moving a family member into a retirement or nursing home within the past 5 y (n = 3) or were currently facing the decision during the pandemic (n = 1).

Then, we drafted 2 PtDAs using the well-tested Ottawa Framework template.7,11,12 Each PtDA was circulated for iterative feedback from our stakeholder team. Next, the PtDAs were translated into French and disseminated broadly. Users were invited to provide feedback on the website, and we planned to modify the PtDAs, if necessary, based on the feedback.

Results

Our initial rapid assessment indicated there was no available PtDA on location of residence during the pandemic. The PtDAs were justified by the families’ and residents’ decision dilemma stemming from the risks of COVID-19 in retirement and nursing homes, the publics’ response to controversial media, and changes in nursing home regulations specific to COVID-19.17

A key source for identifying residents’/families’ decision-making needs were the public’s 298 comments regarding the April newspaper articles.1,18 Many held opposing views on the best course of action. Several commented on the decision dilemma indicating reasons to leave a retirement/nursing home during the pandemic or to stay. It was apparent some readers were not familiar with changes in provincial regulations facilitating discharges and readmissions to nursing homes during the pandemic. On April 3, one public health official’s special statement focused on the decision difficulty:

I totally understand concerns that families have about their loved ones who reside in retirement or long-term care homes. Some families are considering whether to take loved ones out of their retirement or long-term care home. This is a challenging decision . . . a family would need to think about.19

Since our main target audience consisted of Ontario residents, their substitute decision makers, and other family members, we used sources relevant to that province (legislation, policies). The PtDAs included a self-assessment to determine if personal care needs could be met at the family’s home, a home safety assessment, and suggestions to discuss care needs with current care providers.20–22 Statements for the values-clarification exercise were informed by public responses to media reports. The final PtDAs met all IPDAS criteria (qualifying criteria, criteria to minimize risk of bias). The Flesch-Kincaid readability levels were grades 6.7 and 7.1. The PtDAs were endorsed by the Canadian National Institute of Ageing.23

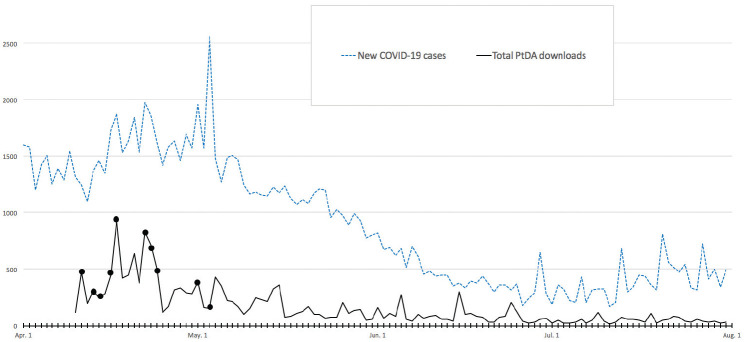

The English and French versions of the PtDAs were disseminated on the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute PtDAs website,16 the National Institute of Ageing website,23 and the International A to Z PtDA inventory.13 They were also promoted through our contacts, including front-line clinicians who work directly with residents/families, organizations having outreach to seniors (Family Councils Ontario, Canadian Association of Retired Persons), and on social media (Twitter, Facebook, Shared@Shared Decision Making Network Facebook). The PtDAs were discussed in 4 media interviews and 16 media articles (e.g., Canada24 the United States25,26) from April 11 to May 3, 2020. The PtDAs were downloaded 10,000 times within the first 3 wk and 17,953 times as of July 31, 2020 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Daily patient decision aid (PtDA) downloads (solid line) and 10 media interviews/reports mentioning the PtDAs (black dots) contrasted with the daily number of new cases of COVID-19 in Canada27,28 (dotted line).

Feedback was received from 3 users. One user thanked us for “the tools that were of great interest” and reported a typo on the French version. The second said, “Thank you to you and your team for putting out resources that will allow families to make informed decisions about their loved ones during this pandemic. My wife, 51 lives with dementia at a long-term care home. I found your document to be most helpful.” A social worker at a Canadian publicly funded rehabilitation facility sent feedback requesting training in using these PtDAs with their residents.

Discussion

Our expert team demonstrated feasible rapid development and wide dissemination of PtDAs to respond to urgent decisional needs due to COVID-19. Efficiencies in the development process were having access to a well-tested theory-based PtDA template, recent evidence syntheses, values-based public responses to media reports, and extensive experience in developing PtDAs. Our findings led to the following considerations.

Expedited design of PtDAs is feasible. IPDAS design processes include patient/clinician decisional needs assessments, format and distribution identification, and review/synthesis of the evidence (Table 1).10 Often, the needs assessments are quite formal, although a more recent approach is to include PtDA users as part of the development team.4,29 Our stakeholder team had members who were positioned to use the PtDAs as clinicians and sometimes as decision makers for their own families. Fortuitously, the intensity of the public’s response to the newspaper articles facilitated assessment of families’ decisional needs. However, our stakeholder team should have included residents who were facing this decision and a broader range of family members.

Regarding the format and evidence, our expert team used the well-tested Ottawa Framework PtDA template.11 The evidence on home versus residential/nursing home was limited by its generalizability to pandemic conditions. Moreover, the evidence on COVID-19 was often unavailable or continuously changing. We incorporated links to sources (e.g., nursing home regulations, public health recommendations) so that users had access to up-to-date information.

Expedited field-testing methods when using a well-tested PtDA template need refinement. IPDAS describes alpha testing with patients and clinicians who have made the decision to assess comprehensibility, acceptability, and usability and beta testing with patients and clinicians facing the decision to assess feasibility.10 Our stakeholder team included clinicians who provided feedback. Although we invited feedback from users on the usefulness of the PtDAs, we had few respondents. Low responses may have been due to the request for feedback on only one page where downloads were possible. Moreover, it may be unrealistic to expect high response rates from users during a crisis. Future studies should determine how to obtain user feedback more formally after rapid dissemination. For example, program the website to provide a pop-up questionnaire eliciting feedback from those who download the PtDAs; however, the ethics review for such a strategy may delay dissemination.

Expedited dissemination and measuring use/outcomes need refinement. We used several strategies, previously described by PtDA developers, to broadly disseminate them.30,31 The PtDAs were delivered online, endorsed by the National Institute of Ageing,23 promoted through organizations for seniors, and discussed in media interviews and social media. Dissemination was likely facilitated by the urgent need in the pandemic crisis. The number of media interviews and downloads were highest around the peak of COVID-19 cases (Figure 1).

In summary, it was possible to rapidly develop and disseminate PtDAs when there was an experienced team with access to a well-tested PtDA template and synthesized evidence. A rapid development approach is appropriate for time-sensitive PtDAs, but there needs to be adequate support, including experienced developers, to avoid poor-quality or biased PtDAs. Future research is required to determine how best to engage more target users in the development and dissemination process, to identify efficient ways to gather more rigorous feedback during development and dissemination, and to measure actual PtDA use and resident/family outcomes.

Footnotes

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Some authors have faced the decision about placing an elderly parent in a retirement home and/or long-term care home; one author had family considering moving a loved one from a retirement home during the pandemic.

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Financial support for this study was provided in part by the University of Ottawa Research Chair in Knowledge Translation to Patients and the National Institute on Ageing. The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report. D.S. is employed by the University of Ottawa and holds the research chair. N.E. and A.M.O. are both emeritus professors at the University of Ottawa. S.S. is the director of health policy research at the National Institute on Ageing at Ryerson University. C.L. is a recipient of a trainee award through the Integrated Knowledge Translation Research Network (CIHR#143237).

P.A. was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Embedded Clinician Researcher Award (#370937) and is now supported by a Fonds de recherche Québec - Santé Senior Clinical Research Scholar Award (#283211).

ORCID iDs: Dawn Stacey  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2681-741X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2681-741X

Patrick Archambault  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5090-6439

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5090-6439

Contributor Information

Dawn Stacey, University of Ottawa, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Claire Ludwig, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada; Champlain LHIN, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Patrick Archambault, Centre de recherche du Centre intégré de santé et de services de santé de Chaudiére-Appalaches and Université Laval.

Kevin Babulic, Champlain LHIN, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Nancy Edwards, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Josée Lavoie, Royal Ottawa Mental Health Centre, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Samir Sinha, University of Toronto/Ryerson University.

Annette M. O’Connor, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

References

- 1. Picard A. If you can get your relatives out of seniors’ homes, try to do so as fast as you can. The Globe and Mail. April 2, 2020. Available from: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-if-you-can-get-your-relatives-out-of-seniors-homes-try-to-do-so-as/

- 2. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Pandemic experience in the long-term care sector: how does Canada compare with other countries? 2020. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/covid-19-rapid-response-long-term-care-snapshot-en.pdf

- 3. Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(4):CD001431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vaisson G, Provencher T, Dugas M, et al. User involvement in the development of patient decision aids: a systematic review. Med Decis Making. 2019. Available from: https://osf.io/qyfkp/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5. Stacey D, Legare F, Boland L, et al. 20th anniversary Ottawa Decision Support Framework part 3: overview of systematic reviews and updated framework. Med Decis Making. 2020;40(3):379–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hoefel L, O’Connor AM, Lewis KB, et al. 20th anniversary update of the Ottawa Decision Support Framework part I: a systematic review of the decisional needs of people making health or social decisions. Med Decis Making. 2020;40(5):555–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hoefel L, Lewis KB, O’Connor AM, Stacey D. 20th anniversary update of the Ottawa Decision Support Framework part 2: sub-analysis of a systematic review of patient decision aids. Med Decis Making. 2020;40(4):522–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Joseph-Williams N, Newcombe R, Politi M, et al. Toward minimum standards for certifying patient decision aids: a modified Delphi consensus process. Med Decis Making. 2013;34(6):699–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ottawa Patient Decision Aids Research Group OHRI. Ottawa Decision Support Framework training in communication skills when providing decision support. 2019. Available from: https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/decision_coaching_communication.pdf

- 10. Coulter A, Stilwell D, Kryworuchko J, Mullen PD, Ng CJ, Van der Weijden T. A systematic development process for patient decision aids. BMC Med Inform Decis Making. 2013;13(S2):1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. O’Connor A, Stacey D, Saarimaki A, et al. Ottawa Patient Decision Aid Development eTraining. 2015. Available from: https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/eTraining/

- 12. Patient Decision Aids Research Group OHRI. Development methods for Ottawa patient decision aids. 2019. Available from: https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/methods.html

- 13. Patient Decision Aids Research Group OHRI. A to Z inventory of decision aids. 2020. Available from: https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/AZinvent.php

- 14. Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. Br Med J. 2006;333(7565):417–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Legare F, Kearing S, Clay K, et al. Are you SURE? Assessing patient decisional conflict with a 4-item screening test. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(8):e308–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Patient Decision Aids Research Group. 2020. Available from: https://decisionaid.ohri.ca

- 17. Ontario Government. O. Reg. 83.20: GENERAL filed March 24, 2020 under Long-term Care Homes Act, 2007, S.O. 2007, c.8. 2020. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/regulation/r20083

- 18. Grant K, Stueck W. Families face tough call over removing loved ones from long-term care. Globe and Mail. April 3, 2020. Available from: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-families-face-tough-call-over-removing-loved-ones-from-long-term-care/#comments.

- 19. Public Health Ottawa. Special statement from Dr. Brent Moloughney, Associate Medical Officer of Health. 2020; Available at: https://www.ottawapublichealth.ca/en/public-health-topics/novel-coronavirus.aspx?utm_source=OPH&utm_medium=Home_Page_Banner&utm_campaign=Coronavirus&utm_content=Home_Page_Banner_OPH#April-3-2020—Special-Statement-from-Dr-Brent-Moloughney-Associate-Medical-Officer-of-Health

- 20. Boland L, Légaré F, Perez MMB, et al. Impact of home care versus alternative locations of care on elder health outcomes: an overview of systematic reviews. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Blanchet R, Edwards N. A need to improve the assessment of environmental hazards for falls on stairs and in bathrooms: results of a scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Edwards N, Dulai J, Rahman A. A scoping review of epidemiological, ergonomic, and longitudinal cohort studies examining the links between stair and bathroom falls and the built environment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(9):1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. National Institute on Ageing. Think tank focused on the realities of Canada’s ageing population. 2020. Available from: https://www.nia-ryerson.ca/

- 24. Richard J. Seniors still hardest hit by COVID-19 pandemic. 2020. Available from: https://torontosun.com/life/relationships/0503-lifenational

- 25. Donato A. Canadians share why they did or didn’t remove a parent from a care home: here’s how two Ontarians answered, “Should I bring my parent home?” Huffington Post. 2020. Available from: https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/entry/decision-longterm-carehomes-canadians_ca_5e9f82d3c5b6b2e5b839b085?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAL8ekM3DuyBt-cCa1B7_AB6ZDuUn2E3rmT8TnmVfDLYidkWEZhC793GDY5dnxASXrbPRiZkY7HXXL-Bvb2EoQ30dOS3JokiW5YtGc832yjB43-15prm8njybUiGuLuzY4QtO3YhVXHWU6t-i6JbgeJyVlY13RSqXjQvmkm5wkkAp

- 26. Graham J. Banned from nursing homes, families need to know if their loved ones are safe. CNN Health. May 1, 2020. Available from: https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/01/health/family-nursing-home-elderly-care-coronavirus-wellness-partner/index.html

- 27. University of Toronto Libraries. COVID-19 data and statistical sources. 2020. Available from: https://mdl.library.utoronto.ca/covid-19/data

- 28. Soucy JPR, Berry I. Covid19Canada/timeseries_canada/cases_timeseries_canada.csv. 2020. Available from: https://github.com/ishaberry/Covid19Canada

- 29. Witteman HO, Dansokho SC, Colquhoun H, et al. User-centered design and the development of patient decision aids: protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Elwyn G, Scholl I, Tietbohl C, Mann M, Edwards AG, Clay C. “Many miles to go …”: a systematic review of the implementation of patient decision support interventions into routine clinical practice. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13(suppl 2):S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stacey D, Suwalska V, Boland L, Lewis KB, Presseau J, Thomson R. Are patient decision aids used in clinical practice after rigorous evaluation? A survey of trial authors. Med Decis Making. 2019;39(7):805–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]