Abstract

Although iatrogenic damage is less often involved, deep nerve injuries are reported especially as a result of small saphenous vein (SSV) dissection. Complete or partial division of the common peroneal nerve (CPN) during varicose vein operations causes substantial and serious disability. Most CPN injuries recover spontaneously; nonetheless, some require nerve surgery. Treatment depends on the nature of CPN injury. This report chronicles 2 instances of CPN injury after SSV surgery, addressing treatment strategies and therapeutic gains. The pertinent literature is also reviewed.

Keywords: Varicose veins, Iatrogenic diseases, Common peroneal neuropathy, Regenerative medicine, Nerve tissue regeneration

Introduction

Common peroneal nerve (CPN) injury usually is due to trauma. Iatrogenic damage is less often involved and deep nerve injuries largely result from small saphenous vein (SSV) dissection. The prospect of regeneration after CPN repair is poor (compared to other peripheral nerves) and poses an immense challenge. This report chronicles 2 instances of CPN injury related to SSV surgery, addressing treatment strategies and therapeutic gains. The pertinent literature is also reviewed.

Cases Presentation

Patient 1

In August 2008, a 57-year-old man underwent left saphenopopliteal ligation (SPL) and multiple avulsions at another hospital. Postoperatively, he showed foot drop and partial anterior leg sensory loss. Three weeks after intervention, nerve conduction studies (NCS) confirmed a left common peroneal neuropathy at the site of the SSV surgery in the popliteal fossa. The patient came to our attention in July 2009. Surgical exploration discovered a neuroma of the popliteal fossa, leaving a nerve gap of ∼7 cm upon excision. An autologous sural nerve graft served for microsurgical repair. After 5 months, the distal motor deficit and hypoesthesia of the lateral leg/dorsal foot had not improved.

Patient 2

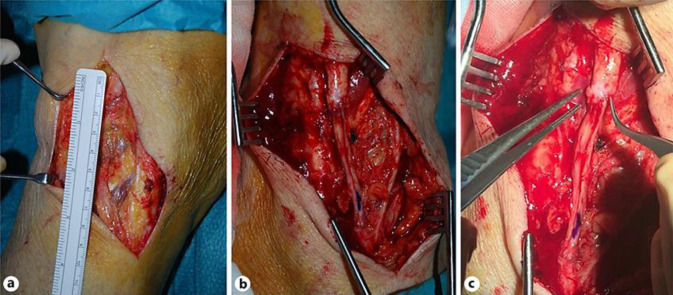

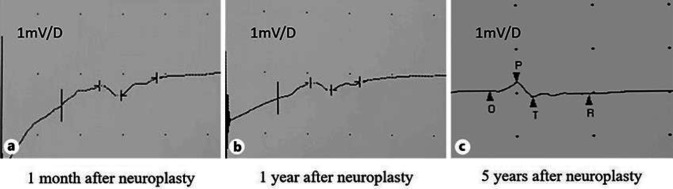

In July 2014, a 76-year-old woman underwent saphenous-popliteal crossectomy and phlebectomies due to right lower limb varices. Postoperatively, she experienced foot drop and dysesthesia of the lateral leg and dorsal foot. One year after, this patient presented to our service. Surgical exploration disclosed 2 amputation stumps separated by a 6-cm gap (Fig. 1a). Histologically, there was marked degenerative change of the proximal stump, with conspicuous endoneural and perineural fibrosis. Neurolysis was performed, followed by microsurgical autologous sural nerve graft (Fig. 1b). The anastomotic ends were then wrapped in human amniotic membrane (HAM) (Fig. 1c). One month after neuroplasty, NCS demonstrated abnormalities isolated to the right peroneal motor responses. The right peroneal nerve had severely decreased distal amplitude and even more decreased proximal amplitude, and there was a prolonged latency and an undetectable nerve conduction velocity. Superficial peroneal nerve sensory nerve action potentials were unobtainable. Electromyographic signs of denervation were found in the right tibialis anterior and extensor hallucis brevis muscles (Fig. 2a). Over the next 5 years, the neuropathy symptoms remained stable and the neurophysiological examinations showed no differences (Fig. 2b, c).

Fig. 1.

a Amputation stumps of right CPN separated by a 6-cm gap. b Sural nerve graft. c Anastomosis between CPN amputation stump and sural nerve graft wrapped in human amniotic membrane.

Fig. 2.

a EMG performed 1 month after neuroplasty. b EMG performed 1 year after neuroplasty. c EMG performed 5 years after neuroplasty.

Discussion

Conventional saphenopopliteal junction (SPJ) ligation, with or without SSV stripping, is the standard treatment for SSV insufficiency. In a survey polling members of the Vascular Surgical Society of Great Britain and Ireland on SSV management, a majority of respondents had performed >15 SPL procedures yearly [1]. This survey underscored a lack of consensus among surgeons regarding the best surgical technique in this context. SPL and extended SSV stripping are well-known causes of medicolegal disputes. Related complaints range from relatively minor problems (recurrent varices, scarring, nerve injuries) to potentially lethal pulmonary embolism or arterial injury requiring amputation [2]. CPN injuries after varicose vein surgery are rare and infrequently reported. Lucertini et al. [3] found this kind of lesion in only 1 of 15 patients (6.7%) undergoing varicose vein surgery involving SSV. Nevertheless, all patients who are a candidate for this type of procedure should be adequately informed of the risks of CPN injury as a potential complication of SSV surgery and about the possibility of its devastating and debilitating sequelae: foot drop upon ambulation, numbness or dysesthesia along the lateral leg and dorsal foot.

The anatomy of SPJ is highly variable; Balasubramaniam et al. [4] investigated the variation of the SPJ, its relationship to the CPN, and the relationship of both SPJ and CPN to defined anatomical landmarks. The level of SPJ termination was classified as low, normal and high when below, within 100 mm above and more than 100 mm above the lateral femoral epicondyle, respectively. The higher the SPJ, the closer it is to the CPN. Considering that the SPJ is commonly found close to the midline within the popliteal fossa, there is an increased risk of CPN injury during surgery associated with high SPJ terminations. This is the reason why preoperative mapping of the SPJ, via Duplex ultrasonography, is mandatory.

Aside from direct intraoperative transection, the CPN can be injured during retraction of the nerve trunk in order to expose the SPJ, as well as during the process of stripping the vein. Intraoperatively, careful tissue handling is therefore important, with avoidance of aggressive retraction of structures within the popliteal fossa; for example, the use of flat retractors in order to minimise local pressure is indicated. Furthermore, surgically induced perineural fibrosis may aggravate or perpetuate any nerve damage that occurs. Because proper command of regional anatomy is essential, surgery of this type should be reserved for more experienced surgeons. Even so, potential nerve injury during SSV surgery cannot be entirely avoided. Peripheral nerve injuries are typically assigned by severity to 1 of 3 categories, each differing in recovery time. The term neuropraxia refers to demyelination of nerve fibres without Wallerian degeneration or axonal injury. Full or partial spontaneous recovery is thus expected, often within days or weeks, without need of surgical intervention. If there is no resolution after 4–6 months, a more serious injury is likely. Axonotmesis signifies direct axonal damage, in addition to focal demyelination, without loss of connective tissue continuity. Neurotmesis, the most severe form of injury, implies full transection of axons and connective tissue layers. Given the length of the CPN, a proximal injury is particularly problematic, because regeneration and reinnervation progresses at about 1–4 mm/day. Furthermore, an injured CPN is less amenable to spontaneous recovery than are other injured peripheral nerves. It has been suggested that this phenomenon may be the result of an imbalance of forces; if, on the one hand, there is a preserved flexor muscle activity, on the other hand, the extensor muscles are paralytic [5]. The resulting equinus foot attitude could be an obstacle to a smooth nerve regeneration [6].

Treatment in this setting depends on the nature of CPN injury. To determine if palsies are complete or incomplete, clinical assessments, electromyography (EMG) tracings, and NCS are vital. Incomplete lesions are often marked by a combination of physiologic conduction block and low-grade axonal disruption. Progressive recovery may be anticipated through axonal regeneration. In the absence of Tinel's sign, complete palsies are due to conduction blocks and should resolve spontaneously. Complete and painful lesions, positive for Tinel's sign, rarely resolve spontaneously. EMG and NCS studies may aid in prognostication, but only at 4–6 weeks after injuries occur. Their value is limited prior to this time. Compared with axonal loss, the prognosis of demyelinating lesions is much more favourable [7]. Only neuropraxic injuries show distal motor conduction by EMG. This finding is absent in the event of neurotmesis or axonotmesis. If the aetiology of a nerve injury is unclear, symptomatic management is achieved through physical therapy, aimed at strengthening anterior muscles (presumably still functional) and stretching the posterior gastrocnemius-soleus complex, and use of ankle-foot orthotics to prevent equinovarus deformity. Observation is initially advocated, for at least 4–6 months, because many peroneal nerve palsies recover or their residual deficits are marginal [8]. After baseline evaluation, a follow-up EMG is advised at 4–6 weeks. For complete palsies, EMG studies at 3 and 6 months are recommended, proceeding to surgical intervention if no recovery is evident [9]. Surgical exploration to establish the continuity of nerves helps in formulating the most suitable treatments. Intraoperative EMG and NCS may be used for this purpose and to document reduced stimulation thresholds after scar release (neurolysis), which is a good prognostic sign. Nerve repair (neurorrhaphy) and nerve grafting are appropriate if there is discontinuity of nerves. Direct nerve repair is indicated in the presence of clean-cut lacerations, with healthy and well-vascularised nerve beds; but this is only feasible if the damage is discovered during surgery. Unfortunately, most of these nerve injuries may not be visible at the time of the operation. Nerve grafting provides a conduit for axonal regrowth across defects. Kim and Kline [10] reported good results with grafts bridging distances <6 cm, showing that outcomes progressively worsen as gaps increase. Niall et al. [11] also demonstrated that the lengths of injured segments are predictive of recovery potential. Lengths >6 cm signal unfavourable outcomes. If gaps are too large for direct tension-free suturing, an alternative remedy is the tubulisation technique, i.e., the interposition between nerve stumps of a biologic or artificial conduit that serves as a protective barrier, discourages scarring or restrictive adhesions and enables an optimal environment for nerve regeneration; it also provides a microenvironment in which various tissues, substances or cells may be introduced to improve the regeneration. Riccio et al. [12] used HAM tubules containing fragments of autologous skeletal muscle, a proven luminal filler for nerve guides, obtaining good results in grafting post-traumatic gaps (up to 5 cm) of median nerve.

Concerning the timing of surgical intervention, George and Boyce [13] reported significantly worse outcomes in treating remote injuries (>12 months prior), whereas recent injuries (≤6 months) yielded more favourable results. If reparative efforts fail to restore CPN function, such patients may be candidates for posterior tibial tendon (PTT) transfer or arthrodesis. In patients with simultaneous peroneal nerve neurolysis, Ho et al. [14] compared repair or grafting plus PTT transfer with PTT transfer alone. Active dorsiflexion was regularly achieved after combined procedures, whereas PTT transfer alone brought success in only 40%. Similarly, Garozzo et al. [5] and Ferraresi et al. [6] reported outstanding results for combination repair/grafting and PTT transfer, claiming that tendon transfer enhances neural regeneration. However, tendon transfers are customarily performed as salvage procedures for remote injuries. It has been determined that motor endplates degenerate 12–16 months after denervation but remain viable in innervated muscles for 18–24 months after injury. If rates of regeneration are not commensurate with lengths of injured segments, irreversible degeneration and fibrosis ensue, culminating in permanently paralyzed denervated muscles. In the first patient we describe, conventional techniques (neurolysis and sural nerve graft) were applied, adding a newer approach (sural nerve graft + HAM tubulisation) in the second patient. Neither strategy was satisfactory in terms of functional recovery, largely for two reasons. Each patient required a graft >6 cm long to fill the gap between CPN stumps. In addition, both presented for care belatedly, 12 months after injury. Chances of successful repair were therefore substantially diminished.

Conclusions

CPN injury is a rare but possible SSV surgery complication, of which patients should be accurately informed. Available therapeutic strategies range from more traditional methods to newer techniques, each with proven efficacy. The chief factors impacting functional recovery are the magnitudes of segmental gaps and the timing of repairs. The greater these become, the less chance there is for functional recovery. If CPN injury is suspected, and complete transection is not a concern, EMG studies will track signs of spontaneous recovery. A failure to resolve within 4–6 months calls for prompt surgical exploration to ensure optimal treatment and increase chances of functional restoration.

Statement of Ethics

The authors confirm obtaining written consent from the patient for publication of the manuscript (including images, case history and data).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Sources

No specific funding was received from any public, commercial, or not-for-profit sources to conduct the work herein.

Author Contributions

Pier Camillo Parodi and Fabrizio De Biasio contributed to the manuscript development, rationale and patients' management. Sebastiano Mura and Nicola Zingaretti reviewed the clinical data, made the literature search and drafted the manuscript. Anna Scalise contributed to the EMG images and descriptions and revised the manuscript.

References

- 1.Winterborn RJ, Campbell WB, Heather BP, Earnshaw JJ. The management of short saphenous varicose veins: a survey of the members of the vascular surgical society of Great Britain and Ireland. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004 Oct;28((4)):400–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Critchley G, Handa A, Maw A, Harvey A, Harvey MR, Corbett CR. Complications of varicose vein surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1997 Mar;79((2)):105–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lucertini G, Viacava A, Ermirio D, Belardi P. Surgery of recurrent varices of the minor saphenous vein [in Italian] Minerva Cardioangiol. 1998;46:91e5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balasubramaniam R, Rai R, Berridge DC, Scott DJ, Soames RW. The relationship between the saphenopopliteal junction and the common peroneal nerve: a cada-veric study. Phlebology. 2009 Apr;24((2)):67–73. doi: 10.1258/phleb.2006.006035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garozzo D, Ferraresi S, Buffatti P. Surgical treatment of common peroneal nerve injuries: indications and results. A series of 62 cases. J Neurosurg Sci. 2004 Sep;48((3)):105–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferraresi S, Garozzo D, Buffatti P. Common peroneal nerve injuries: results with one-stage nerve repair and tendon transfer. Neurosurg Rev. 2003 Jul;26((3)):175–9. doi: 10.1007/s10143-002-0247-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masakado Y, Kawakami M, Suzuki K, Abe L, Ota T, Kimura A. Clinical neurophysiology in the diagnosis of peroneal nerve palsy. Keio J Med. 2008 Jun;57((2)):84–9. doi: 10.2302/kjm.57.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rose HA, Hood RW, Otis JC, Ranawat CS, Insall JN. Peroneal-nerve palsy following total knee arthroplasty. A review of The Hospital for Special Surgery experience. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982 Mar;64((3)):347–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Houdek MT, Shin AY. Management and complications of traumatic peripheral nerve injuries. Hand Clin. 2015 May;31((2)):151–63. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim DH, Kline DG. Management and results of peroneal nerve lesions. Neurosurgery. 1996 Aug;39((2)):312–9. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199608000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niall DM, Nutton RW, Keating JF. Palsy of the common peroneal nerve after traumatic dislocation of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005 May;87((5)):664–7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B5.15607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riccio M, Pangrazi PP, Parodi PC, Vaienti L, Marchesini A, Neuendorf AD, et al. The amnion muscle combined graft (AMCG) conduits: a new alternative in the repair of wide substance loss of peripheral nerves. Microsurgery. 2014 Nov;34((8)):616–22. doi: 10.1002/micr.22306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.George SC, Boyce DE. An evidence-based structured review to assess the results of common peroneal nerve repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014 Aug;134((2)):302e–11e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho B, Khan Z, Switaj PJ, Ochenjele G, Fuchs D, Dahl W, et al. Treatment of peroneal nerve injuries with simultaneous tendon transfer and nerve exploration. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014 Aug;9((1)):67. doi: 10.1186/s13018-014-0067-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]