Abstract

Background

Stimulated by both microbial and endogenous ligands, toll-like receptors (TLRs) play an important role in the development and progression of renal diseases.

Summary

As a highly conserved large family, TLRs have 11 members in humans (TLR1∼TLR11) and 13 members in mouse (TLR1∼TLR13). It has been widely reported that TLR2 and TLR4 signaling, activated by both exogenous and endogenous ligands, promote disease progression in both renal ischemia-reperfusion injury and diabetic nephropathy. TLR4 also vitally functions in CKD and infection-associated renal diseases such as pyelonephritis induced by urinary tract infection. Stimulation of intracellular TLR7/8 and TLR9 by host-derived nucleic acids also plays a key role in systemic lupus erythematosus. Given that certain microRNAs with GU-rich sequence have recently been found to be able to serve as TLR7/8 ligands, these microRNAs may initiate pro-inflammatory signal via activating TLR signal. Moreover, as microRNAs can be transferred across different organs via cell-secreted exosomes or protein-RNA complex, the TLR signaling activated by the miRNAs released by other injured organs may also result in renal dysfunction.

Key Messages

In this review, we sum up the recent progress in the role of TLRs in various forms of glomerulonephritis and discuss the possible prevention or therapeutic strategies for clinic treatment to renal diseases.

Keywords: Toll-like receptors, Renal diseases

Introduction

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are named after their structural homology with the Drosophila protein Toll, which plays a key role in protection from fungal infection [1]. This family of proteins recognizes pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and consequently triggers innate immune defense against pathogenic infections [2]. TLRs are the focal point of host-microbe interactions because they not only serve as a critical mediator of pathogen recognition by the innate immune system but also link the innate immunity to the adaptive immunity [1]. Moreover, these receptors can contribute to autoimmune diseases by the recognition of endogenous molecules, also known as damage-associated molecular patterns, released from damaged tissue [3]. Accumulating evidence show that dysregulation of TLRs is critically involved in multiple renal diseases including urinary tract infections (UTIs), ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury, acute kidney injury (AKI), lupus nephritis (LN), and diabetic nephropathy (DN) [3]. In the remainder of this review, we will discuss the anti-infectious mechanism of TLR family, the recent progress in the role of TLRs in various forms of glomerulonephritis, and the possible prevention or therapeutic strategies for clinic treatment to renal diseases.

Since TLR4 was defined as the first TLR member in mammals in 1998, the number of TLR family has been expanded to 11 members in humans (TLR1∼TLR11) and 13 members in mouse (TLR1∼TLR13) [2]. TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, and TLR6 are located on the cell surface. TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9 are expressed exclusively on the membrane of endosomes such as endoplasmic reticulum, endosomes, lysosomes, and endolysosomes [2]. The mRNA expression of human TLR1∼TLR10 can be detected in all human tissues including adrenal gland, brain, heart, kidney, liver, lung, placenta, prostate, salivary gland, skeletal muscle, small intestine, spinal cord, spleen, testis, thymus, thyroid gland, trachea, and uterus. However, TLR protein expressions display a diverse repertoire in human peripheral blood leukocytes [4]. Table 1 lists the expression pattern of TLRs of human immune and nonimmune cells in detail. According to the genomic structure and amino acid sequences, TLR family can be divided into 5 subgroups, namely TLR3, TLR4, TLR5, TLR2, and TLR9 subgroups. TLR3, TLR4, and TLR5 genes comprise 5, 4, and 5 exons, respectively. TLR2 subfamily includes TLR1, TLR2, TLR6, and TLR10. TLR1 and TLR6 are located in tandem on chromosome 4. Both have 1 exon and share similar genomic and protein structures. The identity of overall amino acid sequence between TLR1 and TLR6 is 69.3% [4]. The Toll receptor/interleukin (IL)-1 receptor (TIR) domains, in particular, of both receptors exhibit over 90% identity. TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9 belong to the TLR9 subgroup and are encoded by 2 exons. TLR7 and TLR8 are located close together on chromosome X, and they show 42.3% identity and 72.7% similarity in their amino acid sequences and TIR domains [4].

Table 1.

TLR expressions in human immune and nonimmune cells

| Cell types | TLR expression patterns [51, 52, 53, 54, 55] |

|---|---|

| Monocyte | TLR1, TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR8, TLR9 |

| Neutrophil | TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, TLR6, TLR7, TLR8, TLR9 |

| B cell | TLR1, TLR2, TLR3, TLR5, TLR6, TLR7, TLR9, TLR10 |

| T cell | TLR1, TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR5, TLR6, TLR8, TLR9 |

| Natural killer cell | TLR1, TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR5, TLR6, TLR7, TLR8 |

| Dendritic cell | TLR1, TLR2, TLR 3, TLR4, TLR5, TLR6, TLR8 |

| Platelet | TLR1, TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR6, TLR7, TLR9 |

| Oocyte | TLR3, TLR4, TLR5 |

| Hela | TLR1, TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR5, TLR6, TLR7, TLR8, TLR9, TLR10 |

| HepG2 | TLR2, TLR3, TLR6, TLR9 |

| MDA-MB-468 | TLR2, TLR3, TLR6, TLR8, TLR9 |

| T47D TLR, Toll-like receptor. |

TLR3, TRL5, TLR8, TLR9 |

Activation of TLRs by Microbial or Endogenous Ligands

TLRs are germline-encoded type I transmembrane proteins containing extracellular leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain, a cytoplasmic domain, and a transmembrane domain [5]. The extracellular LRR domain is responsible for recognizing diverse microbial and endogenous ligands. The cytoplasmic domain is necessary for initiating the intracellular signal transduction, which is evolutionarily conserved and homologous with the TIR [5]. The immune functions of TLRs begin by their specific recognition of ligands. Upon ligand binding to the LRR-containing ectodomain of TLRs, specific adaptor proteins are recruited to the intracellular TIR domains, which drive subsequent inflammatory response and even adaptive immunity [2].

Mammalian TLRs on the plasma membrane detect cognate microbial products. For instance, TLR4 recognizes LPS of gram-negative bacteria [6]. TLR5 binds bacterial flagellin [6]. TLR2 recognizes PAMPs including lipopeptides from bacteria, lipoarabinomannan from mycobacteria, peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acid from gram-positive bacteria, zymosan from fungi, and hemagglutinin protein from measles virus [2]. TLR2 can also form heterodimer with TLR1 or TLR6. The TLR2-TLR1 heterodimer is essential to recognize triacylated lipopeptides derived from gram-negative bacteria like Mycobacterium tuberculosis[2], while TLR2-TLR6 heterodimer can pick out diacylated lipopeptides from gram-positive bacteria and mycoplasma [2]. TLRs on the endosomal membranes can recognize synthetic or microbial nucleic acids. For instance, TLR3 can recognize double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) including synthetic polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (poly[I:C]), viral genomic RNA, dsRNA produced during the replication of single-stranded RNA (ssRNA), and small interfering RNAs [6]. TLR7 and TLR8 are phylogenetically similar and both can detect viral ssRNA [2] as well as synthetic small chemical ligands CL075 and R848 [7]. TLR9 can detect unmethylated cytidine-phosphate-guanosine DNA chromatin derived from bacteria or viruses [2]. Synthetic cytidine-phosphate-guanosine oligodeoxynucleotides are also able to be recognized by TLR9 [2]. The ligand of TLR10, however, remains unknown.

In addition, TLRs also recognize endogenous ligands like heat shock proteins, high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) proteins, and the components of extracellular matrix (ECM), which originated from injured or dying cells, tumor cells, and immune complex (IC)-containing self-antigens [2]. Heat shock proteins such as Hsp70, Hsp22, and gp96 can activate macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) by TLR2 or TLR4 [2]. HMGB1 also activates TLR2 and TLR4 [8]. ECM components like biglycan and hyaluronan act on TLR2 and TLR4 to mediate the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [2]. ECM proteoglycan versican stimulates macrophages to promote cancer metastasis through binding TLR2-TLR6 heterodimer [2]. Furthermore, TLR4 recognizes extra domain A-containing fibronectin, surfactant protein A, oxidized low-density lipoprotein, amyloid-β, and β-defensin 2 [2]. Endogenous ligands of intracellular TLRs include RNA, chromatin-DNA, and ribonucleoprotein complexes. TLR3 recognizes self mRNAs or other self dsRNAs released from necrotic cells and induces sterile immune responses [2]. TLR7 binds ssRNA from rheumatoid arthritis synovial fluid [9], GU-rich miRNA [10], imidazoquinoline, guanosine, and guanine analogs [7]. TLR8 also recognizes GU-rich miRNA [10]. TLR9 detects chromatin-DNA, chromatin ICs, or a chromatin-associated protein [2]. Table 2 sums up the corresponding ligands of each TLR member in detail.

Table 2.

Microbial, synthetic, and endogenous ligands for TLRs in humans

| TLR | Microbial ligands | Endogenous ligands | Synthetic ligands |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLR1-TLR2 | Triacylated lipopeptides [2] | ||

|

| |||

| TLR2 | Lipopeptides [2], lipoarabinomannan [2], peptidoglycan [2], lipoteichoic acid [2] | Hsp70 [2], Hsp22 [2], gp96 [2], HMGB1 [2], biglycan [2], hyaluronan [2] | |

|

| |||

| TLR3 | Viral genomic RNA [6] dsRNA [2], siRNA [6] | mRNAs [2] | Poly(I:C) [6] |

|

| |||

| TLR4 | LPS [6] | Hsp70 [2], Hsp22 [2], gp96 [2], HMGB1 [2], biglycan [2], hyaluronan [2], EDA-containing fibronectin [2], SP-A [2], oxidized low-density lipoprotein [2], amyloid-β [2], β-defensin 2 [2] | |

|

| |||

| TLR5 | Flagellin [6] | ||

|

| |||

| TLR6-TLR2 | Diacylated lipopeptides [2] | Versican [2] | |

|

| |||

| TLR7 | ssRNA [2] | ssRNA [9], GU-rich miRNA [10], imidazoquinoline [7], guanosine [7], guanine analogs [7] | CL075 [7], R848 [7] |

|

| |||

| TLR8 | ssRNA [2] | GU-rich miRNA [10] | CL075 [7], R848 [7] |

|

| |||

| TLR9 | Unmethylated CpG DNA [2] | chromatin-DNA [2], chromatin IC [2], chromatin-associated protein [2] | CpG oligodeoxy-nucleotides [2] |

|

| |||

| TLR10 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

TLR, Toll-like receptor; dsRNA, double-stranded RNA; siRNA, small interfering RNA; poly(I:C), polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid; HMGB1, high-mobility group box 1; EDS, extra domain A; SP-A, surfactant protein A; ssRNA, single-stranded RNA; CpG, cytidine-phosphate-guanosine; IC, immune complex.

The Intracellular Signal Transduction of TLRs

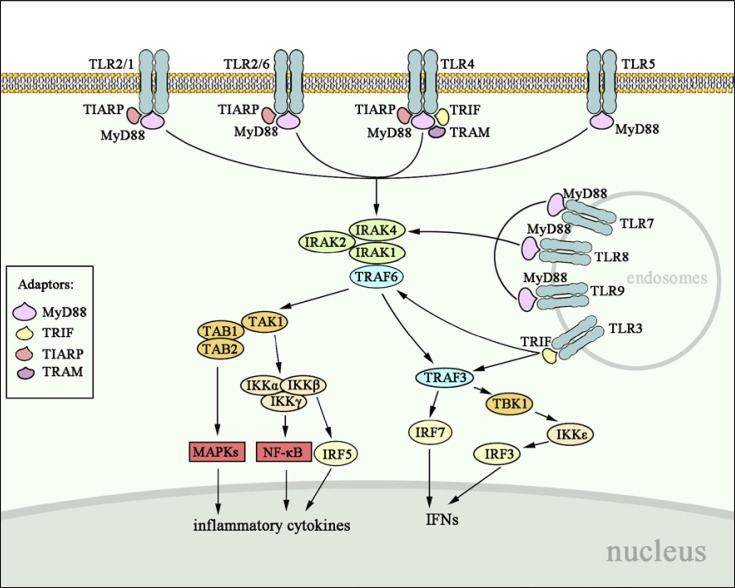

Upon ligand binding to the LRR domain, nonenzymatic TLRs will dimerize to change the conformation of the intracellular TIR domains, which subsequently recruit a range of adaptor molecules to trigger downstream kinases activity for signaling cascades [11]. Canonical adaptors include myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88), TIR-domain-containing adaptor-inducing interferon-β (TRIF, also known as TICAM1), TRIF-related adaptor molecule (TRAM, also known as TICAM2), and MyD88 adaptor-like (TIRAP, also known as MAL) [11]. Based on the adaptor molecules, TLR signaling pathway can be divided into MyD88-dependent pathway and MyD88-independent pathway (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Intracellular signal transduction of TLR family. All TLRs except TLR3 recruit MyD88 to activate IRAK complex and TRAF6, which acts on TAK1 to initiate downstream MAPK, NF-κB, IRF5, and IRF7, leading to the production of inflammatory cytokines and IFNs. TRAF6 also activates TBK1-IKKε-IRF3 axis to induce IFNs; yet, this signaling pathway is TRAF3-dependent. TLR3 particularly recruits TRIF to initiate downstream pathways through the activation of TRAF6 and TRAF3. TLR4 initiates signal via both MyD88-dependent and MyD88-independent pathways. TLR, Toll-like receptor; TRAF6, tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6; TAK1, transforming growth factor β-activated kinase 1, MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-B; IRF, interferon regulatory factor; IFN, interferon; TRIF, TIR-domain-containing adaptor-inducing interferon-β; TIR, Toll receptor/interleukin (IL)-1 receptor.

MyD88-Dependent Pathway

MyD88 is a core adaptor protein that mediates the signal transduction of all TLRs except TLR3. MyD88 has 2 functional domains: C-terminal TIR domain and N-terminal death domain (DD). As shown in Figure 1, MyD88 binds its C-terminal TIR domain to the TIR domains of both TIR and IL-1 receptors and utilizes its N-terminal DD to recruit DD-containing serine/threonine kinases, such as IRAK1, IRAK2, and IRAK4. The IRAK4 is initially phosphorylated and activated, leading to the activation of nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) [11]. The subsequently activated IRAK1 and IRAK2 are responsible for the robust activation of NF-κB and MAPKs [11]. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), an E3 ubiquitin ligase, is also activated by MyD88 and associates with IRAKs [5]. On the one hand, TRAF6 stimulates the transforming growth factor β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1), resulting in the activation of inhibitor of NF-κB kinases (IKKs) composed of IKKγ-scaffolded IKKα and IKKβ. This kinase complex will sequentially ubiquitinate, phosphorylate, and degrade IKKα, which relieves the IKKα-mediated suppression of NF-κB activity [5]. TAK1 also recruits TAK1-binding protein (TAB1 or TAB2) to activate the MAPKs including MAPK1, MAPK8, and MAPK13. On the other hand, TRAF6 can induce the production of interferon (IFN) α and β as well as the IFN-inducible genes by activating the key transcription factors, interferon regulatory factor (IRF) 7 [12]. Notably, IRF5 phosphorylated by IKKβ does not participate in IFN secretion but controls inflammatory cytokines [13]. Therefore, MyD88-dependent pathway is essential for inducing pro-inflammatory cytokines and IFN signals.

MyD88-Independent Pathway

MyD88-independent signaling pathway mainly refers to TRIF-dependent pathway, which is responsible for mediating the effects of TLR3 and TLR4 to induce IFNs and IFN-inducing genes as well as NF-κB and MAPKs [14]. TRIF-dependent pathway has 3 ways to exert its functions (Fig. 1). Similar to MyD88, TRIF also recruits TRAF6 and stimulates TAK1 for the activation of NF-κB and MAPKs. TRIF can recruit noncanonical IKKε (IKKi) and TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) to phosphorylate IRF3 and induce IFN secretion. The TBK1-IKKi activation is TRAF3-dependent as deficiency of TRAF3 affects IFN-β induction deriving from TLR3, TLR7, and TLR9 agonists [15]. TRAM and TIRAP are peripheral membrane proteins and act as sorting adaptor proteins guiding TRIF and MyD88 to distinct TLRs, respectively. TRAM interacts with TRIF to increase the TBK1 activity [16]. This TRAM-mediated pathway is only restricted to TLR4 effect [16]. TIRAP guided MyD88 to TLR4, TLR2, TLR1, and TLR6 when natural PAMPs are recognized as immune agonists [17].

Role of TLR Activation in Renal Diseases

Activation of TLR signaling plays an important role in development and progression of various renal diseases. Table 3 sums up the involvement of TLRs in different renal diseases.

Table 3.

TLRs and their associated renal diseases

| Renal diseases | TLR expression | Function in renal diseases |

|---|---|---|

| AKI | TLR2, TLR4 [19, 20, 21] | Recruitment of either proinflammatory M1 macrophages into the kidney via CD14-TLR2-TLR4 axis at early stage or anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages through CD44-TLR4 axis at later phase |

|

| ||

| LN | TLR2, TLR4 [26] | Anti-DNA autoantibody-associated tissue damage |

|

|

||

| TLR5 [22] | Susceptibility to LN | |

|

|

||

| TLR7 [24, 25] | Progression of SLE manifestations | |

|

|

||

| TLR9 [24, 25] | Remission of SLE manifestations | |

|

|

||

| DN | TLR2, TLR4 [30, 31, 56, 57] | Initiation and propagation of DN |

|

|

||

| TLR3, TLR5, TLR7/8 [32] | Functions unknown | |

|

| ||

| CKD | TLR2 [33] | Functions unknown |

|

|

||

| TLR4 [33, 34, 35] | Production of cathelicidin, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, and MCP-1 | |

|

| ||

| Nephrotoxicity | TLR2 [39] | Attenuation of the CDDP-induced AKI |

|

|

||

| TLR4 [36, 37, 38, 58] | Renal inflammation in CsA nephrotoxicity | |

|

| ||

| UTI | TLR4 [40] | Recruitment of leukocyte and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines |

|

|

||

| TLR5 [42] | Immunosuppressive state | |

|

| ||

| Leptospirosis | TLR2, TLR4 [43] | Production of cytokines in host and induction of humoral response against Leptospira interrogans |

|

| ||

| Candidemia | TLR1, TLR2 [44] | Fungal colonization and inflammatory responses |

|

| ||

| Hypertensive kidney | TLR2, TLR4 [46] | Activation of MAPKs |

|

| ||

| NAFLD-associated renal injury | TLR4 [47] | Kidney immunotoxicity and glomerular dysfunction |

|

| ||

| OSA-associated renal damage | TLR4 [48] | Early renal injury induced by hypoxia |

TLR, Toll-like receptor; AKI, acute kidney injury; LN, lupus nephritis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; DN, diabetic nephropathy; IL, interleukin; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant peptide protein 1; CDDP, cisplatin; UTI, urinary tract infection; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea.

Acute Kidney Injury

AKI is a severe syndrome characterized by inflammatory tubular damage. Many factors including I/R, drug toxicity, and infection will conduce to AKI. In this section, we mainly focused on I/R-induced AKI. Drug toxicity and infection will be discussed alone, respectively, in later sections. The pathogenesis of AKI can be triggered by TLRs, especially TLR2 and TLR4. TLR2 deficiency could diminish macrophages and attenuate renal damage [18]. TLR4 deficiency protected kidney from both dysfunction and histological damage associated with I/R by reducing granulocytes, pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and apoptosis of tubular epithelial cells [3]. In renal I/R injury, TLR2 functions through both MyD88-dependent and MyD88-independent pathways, while TLR4 effect completely depends on MyD88 [3, 19]. As co-receptors for TLR2 and TLR4, CD14 and CD44 are abnormally upregulated in tubular cells during AKI. CD14 and CD44 may play pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory role. For instance, in I/R AKI, TLR2 and TLR4 bind to biglycan and recruit either pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages into the kidney via CD14-TLR2-TLR4 axis at early stage [20] or anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages through CD44-TLR4 axis at later phase [21]. The M1 phenotype cells promote inflammatory responses, tissue damage, and kidney failure via producing TNF-α, IL-6, and nitric oxide synthase 2, whereas M2 macrophages contribute to inflammation resolution, tissue repair, and regeneration via secreting IL-10, IL-4, and arginase-1 [21]. To date, the underlying mechanisms of TLR3, TLR7, and TLR9 in regulating AKI pathogenesis remain to be further investigated.

Lupus Nephritis

LN is a severe manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) because deposition of ICs can cause proteinuria, hematuria, and renal failure. Renal TLR3, TLR4, TLR5, TLR7, and TLR9 are reportedly overexpressed in SLE patients compared to healthy controls [22, 23]. Specifically, the expression of TLR3, TLR4, and TLR9 is high in the glomeruli and tubules, while TLR7 is restrictedly increased in the tubulointerstitial [23]. TLR5 expression is intensely increased in the renal tubules [22]. TLR7 and TLR9 recognize RNA and DNA, respectively, to help B cells produce anti-RNA and anti-chromatin autoantibodies during SLE development. Both signal in the same MyD88-dependent way [24]. However, TLR7 accelerates the manifestations of SLE, whereas TLR9 ameliorates them [25]. TLR9 inhibits the production of anti-RNA autoantibodies that is stimulated by TLR7, indicating potential cross-regulation of autoantibody production as well [24]. Lupus-prone mice with TLR9 deficiency possess more autoantibodies against RNA-containing antigens, higher TLR7 protein levels, and increased TLR7-reactive ICs [26]. TLR9-deficient mice also displayed more severe DC infiltration in the kidney [26]. In addition to TLR7 and TLR9, TLR2 and TLR4 are found to be activated by HMGB1 and involved in anti-DNA autoantibody-associated tissue damage in LN [26]. How TLRs participate in distinct manifestations of SLE also depends on cell types. For instance, specific MyD88 knockout in B cells predominantly alleviates LN, while MyD88 deletion in DCs is critical for lupus dermatitis [27]. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells enhanced by TLR7 are significantly expanded in the kidney and spleen of lupus patients or lupus-prone mice [28]. TLR9 can either ameliorate granulopoiesis via suppressing IFN production by neutrophils or promote the occurrence of glomerulonephritis in the progression of SLE via upregulating TLR8 and its downstream cytokines in podocytes [29].

Diabetic Nephropathy

Diabetes is a chronic pro-inflammatory state with increased inflammatory cytokines, NF-κB activation, and positive C-reactive protein, which leads to severe complications such as diabetic nephropathy (DN) [30]. TLR2 and TLR4 are critical in initiating and propagating DN. Knocking out of TLR2 or TLR4 can relieve DN manifestations including albuminuria, podocyte and tubular injury, glomerular hypertrophy, and hypercellularity and renal inflammation [30]. Both TLR2 and TLR4 can be stimulated by HMGB1 and mediate the activation of NF-κB in proximal tubular cells, but the long-term pro-inflammatory role merely depends on TLR2. In vivo data showed an increase in tubular TLR2, HMGB1, and fibronectin expression, supporting that the pathway of HMGB1-TLR2-NF-κB might be the predominant inflammatory mediator for DN [31]. TLR4 can be activated by HMGB1 and HSP70 under the condition of high glucose and thereby promotes tubular and podocyte injury through NF-κB-mediated inflammation [31]. Diabetic pig model showed a significant increase in MyD88-dependent TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, TLR7, and TLR8 and MyD88-independent TLR3, as well as their downstream mediators MyD88, IRAK1, IRF3, IKKs, and NF-κB in the kidney [32]. However, so far, little is known about the role of TLR3, TLR5, TLR7, and TLR8 in the pathogenesis of DN and to what extent these TLRs will affect diabetic kidney.

Chronic Kidney Diseases

CKD is characterized by progressive loss of kidney function and may lead to irreversible nephron loss, ESRD, and even death. TLR2 and TLR4 are the most common TLRs activated in CKD. Both TLR2 and TLR4 were upregulated in the monocytes of ESRD patients compared to the healthy controls, and TLR4 expression was also higher in the neutrophils of ESRD groups than in the healthy controls [33]. The difference in TLR4 expression in monocytes and neutrophils was further confirmed in the healthy volunteers and CKD patients with or without hemodialysis (HD) [34]. Neutrophil TLR4 expression was significantly higher in HD patients than in CKD patients and healthy controls, and positively correlated with the production of cathelicidin, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, and monocyte chemoattractant peptide protein 1. Whereas monocyte TLR4 level was distinctly increased in CKD patients compared to HD patients and healthy controls. Different from neutrophil TLR4, TLR4 expression in CKD monocytes was positively correlated with IL-6 and monocyte chemoattractant peptide protein 1 but negatively correlated with cathelicidin. TLR4 was also activated in the skeletal muscle of CKD patients and thereby enhanced downstream MAPKs, NF-κB, and TNF-α expression during the progressive loss of renal function [35].

Drug-Induced Nephrotoxicity

Nephrotoxicity is a common side effect of drugs, which contributes to renal inflammation, tubular injury, and fibrosis. TLR-mediated innate immune signals, especially TLR4, play a critical role during drug-induced nephrotoxicity. For instance, TLR4/MyD88/IRAK/NF-κB pathway was a key pathogenic signal in CsA nephrotoxicity through promoting renal inflammation [36]. TLR4-deficient mice exhibited less tubular injury and renal fibrosis compared to WT mice when administrated with CsA [36]. HMGB1 was considered as the main upstream stimulator of TLR4-mediated tubular injury in CsA nephrotoxicity since tubular cells were observed to secret HMGB1 after treatment with CsA both in vitro and in vivo [36]. Supporting this, blockade of HMGB1 successfully ameliorated CsA nephrotoxicity through preventing the activation of TLR4/NF-κB signals [37]. Elevated TLR4 expression was also observed in compound FK506-induced nephrotoxicity and acetaminophen-caused organ toxicity [38]. In addition to TLR4, TLR2 was also involved in cisplatin (CDDP)-induced AKI. TLR2, whose expression was enhanced by galectin 3 (Gal-3) in renal DCs, significantly attenuated the CDDP-induced inflammation and AKI [39].

Infectious Kidney

Escherichia coli can bind to glycolipid receptors of urothelial and kidney tubular cells in the pathogenesis of UTI, which subsequently drives TLR4 activation, leukocyte recruitment, and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines [40]. Moreover, E. coli can produce a TIR homologous protein, TcpC, which binds to MyD88 and inhibits the MyD88 downstream signals. In this way, E. coli could weaken the host immune responses and improve bacterial survival [41]. In addition, UTI frequently occurs in renal transplant patients due to long-term tacrolimus treatment, resulting in less phagocytosis of E. coli and less secretion of myeloperoxidase and chemokines by granulocytes. This immunosuppressive state might be attributed to reduced expression of TLR5 in macrophages as well as increased TLR-negative regulators like IRAK-M [42]. Apart from UTI, TLR signals also play a vital role in response to leptospirosis caused by Leptospira interrogans and candidemia caused by Candida albicans. TLR2, TLR4, MyD88, and TRIF were found essential for production of cytokines in host and induction of humoral response against L. interrogans[43]. TLR1, TLR2, and TLR6 were regarded as critical mediators for fungal colonization and inflammatory responses in the candidemia kidney. As expression of these TLRs in the kidney could be enhanced by deficiency of nitric oxide synthase 3, NOS inhibition might mitigate candidemia [44].

Nephropathy Associated with Other Organ Dysfunction

Hypertension and cardiovascular events are common complications associated with renal diseases. As a major product of renin-angiotensin system, angiotensin II (ANG II) not only promotes hypertension but also causes inflammatory kidney damage via inducing cytokine release and immune cell infiltration in the kidney [45]. ANG II might activate TRIF to modulate TLR3 and TLR4 signals, in which TLR3-TRIF and TLR4-TRIF axes contributed to hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy, respectively [45]. Yu et al. [46] reported that in spontaneously hypertensive rats, ANG II upregulated the expression of TLR2 and TLR4 and promoted subsequent activation of MAPKs through TLR/MyD88/MAPK pathway. Their study further showed that genipin administration counteracted the ANG II-mediated pro-inflammatory responses and improve renal functions [46]. TLRs can also regulate the development and progression of renal diseases under the dysfunction of other organs. For instance, HMGB1-mediated TLR4 signaling contributed to the kidney immunotoxicity and glomerular dysfunction under the condition of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [47]. Patients with obstructive sleep apnea usually undergo a process of hypoxia-reoxygenation, which causes oxidative stress response in the kidney and induces renal injury. Such hypoxia stimulation would upregulate the levels of soluble form of TLR4 in the peripheral blood, promote HMGB1 secretion and translocation, and downregulate PPARγ expression [48].

Recent studies have demonstrated that intracellular TLR7/8 can be activated by miRNAs containing GU-rich sequences [10, 49, 50]. Given that miRNAs, particularly secretory miRNAs, are constantly transferred between different cells or tissues via extracellular vesicles or RNA-protein complexes, TLR7/8 can be activated by miRNAs from other injured organs [10]. For example, Wang et al. [10] found that under hepatic injury, hepatic miR-122, an miRNA carrying GU-rich sequence, was secreted into the blood circulation in an exosome-independent manner and taken up by alveolar macrophages. In alveolar macrophages, hepatic miR-122 bound to endosomal TLR7/8 and activated the TLR7-mediated inflammatory responses [10]. In addition, tumor-secreted miR-21 and miR-29a, both consisting of a GU-rich motif, exhibited the capacity of binding macrophage TLR7/8 and triggering TLR-mediated pro-metastatic inflammatory response [50]. Moreover, the study by Lehmann et al. [49] demonstrated that extracellular let-7b, also with a GU-rich motif, could activate neuronal TLR7 and induce neurodegeneration. These findings strongly suggest that miRNAs with GU-rich motifs are novel ligands for stimulating endosomal TLR7/8, which may play an important role in mediating organ-organ communication. Given that the levels of circulating miR-122, miR-21, and miR-29a in renal cell carcinoma, CKD, or IgAN are high, in which these miRNAs serve as biomarkers, we speculate that these miRNAs with GU-rich sequences are likely derived from other injured tissues such as liver and may modulate the development and progression of renal dysfunctions via activating endosomal TLR7/8 signaling in kidney.

Conclusions

In this brief review, we have summarized the roles and working models of TLRs in various renal diseases. Tremendous progresses have been made during last decade. Strong evidence comes from I/R AKI and DN, in which MyD88-dependent TLR2 and TLR4 are the main triggers of pro-inflammatory responses. TLR2 and TLR4 also play a role in initiating and aggravating CKD, drug-induced nephrotoxicity, and infectious kidney. Other available models of interstitial disease include renal fibrosis-inducing UUO, in which TLR4 plays a significant part in a way independent of canonical profibrotic signals TGF-β and SMAD. In autoimmune glomerular disease, TLR7 and TLR9 stimulated by various endogenous ligands (RNA or chromatin-containing autoantigens) are pivotal for the loss of tolerance to autoantigens in SLE development. The in vivo results confirm the role of TLR7 in promoting autoantibody production and inducing LN, but the role of TLR9 needs to be further clarified. There is increasing evidence that exogenous ligands for TLRs can exacerbate SLE and other types of GN, though the role of these TLR ligands in GN diseases other than SLE remains incompletely understood. TLR2, TLR3, and TLR4 also function in the nephropathy associated with hypertension and cardiovascular disease, as well as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and obstructive sleep apnea. An important field of future study will be to identify new endogenous ligands for TLRs and classify the importance of TLR ligands in glomerular diseases. Recent findings of GU-rich miRNAs directly serving as a ligand for TLR7/8 significantly extend the TLR ligand list and shed light in our understanding of TLR-mediated kidney injures associated with other organ dysfunction. Confirmation of which endogenous ligands for TLRs are important in renal diseases will be critical for developing TLR blockade as a potential therapeutic strategy for renal diseases.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2018YFA0507100), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31670917, 31770981), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2018M642211).

Author Contributions

M.L. contributes to drafting the work and K.Z. is responsible for the conception of the work and final approval of the version to be published. M.L. and K.Z. are responsible for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy of any part of the work are appropriately resolved.

References

- 1.Pasare C, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors: linking innate and adaptive immunity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2005;560:11–8. doi: 10.1007/0-387-24180-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11((5)):373–84. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gluba A, Banach M, Hannam S, Mikhailidis DP, Sakowicz A, Rysz J. The role of toll-like receptors in renal diseases. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010;6((4)):224–35. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2010.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:335–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gay NJ, Symmons MF, Gangloff M, Bryant CE. Assembly and localization of toll-like receptor signalling complexes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14((8)):546–58. doi: 10.1038/nri3713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124((4)):783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shibata T, Ohto U, Nomura S, Kibata K, Motoi Y, Zhang Y, et al. Guanosine and its modified derivatives are endogenous ligands for TLR7. Int Immunol. 2016;28((5)):211–22. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxv062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang H, Tracey KJ. Targeting HMGB1 in inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799((1–2)):149–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chamberlain ND, Kim SJ, Vila OM, Volin MV, Volkov S, Pope RM, et al. Ligation of TLR7 by rheumatoid arthritis synovial fluid single strand RNA induces transcription of TNFα in monocytes. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72((3)):418–26. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y, Liang H, Jin F, Yan X, Xu G, Hu H, et al. Injured liver-released miRNA-122 elicits acute pulmonary inflammation via activating alveolar macrophage TLR7 signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116((13)):6162–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1814139116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luo L, Lucas RM, Liu L, Stow JL. Signalling, sorting and scaffolding adaptors for toll-like receptors. J Cell Sci. 2019;133((5)):jcs239194. doi: 10.1242/jcs.239194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Honda K, Yanai H, Mizutani T, Negishi H, Shimada N, Suzuki N, et al. Role of a transductional-transcriptional processor complex involving MyD88 and IRF-7 in toll-like receptor signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101((43)):15416–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406933101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ren J, Chen X, Chen ZJ. IKKβ is an IRF5 kinase that instigates inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111((49)):17438–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418516111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, Hoshino K, Kaisho T, Sanjo H, et al. Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-independent toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Science. 2003;301((5633)):640–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1087262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Häcker H, Redecke V, Blagoev B, Kratchmarova I, Hsu LC, Wang GG, et al. Specificity in toll-like receptor signalling through distinct effector functions of TRAF3 and TRAF6. Nature. 2006;439((7073)):204–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, Uematsu S, Hoshino K, Kaisho T, et al. TRAM is specifically involved in the toll-like receptor 4-mediated MyD88-independent signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2003;4((11)):1144–50. doi: 10.1038/ni986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonham KS, Orzalli MH, Hayashi K, Wolf AI, Glanemann C, Weninger W, et al. A promiscuous lipid-binding protein diversifies the subcellular sites of toll-like receptor signal transduction. Cell. 2014;156((4)):705–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leemans JC, Stokman G, Claessen N, Rouschop KM, Teske GJ, Kirschning CJ, et al. Renal-associated TLR2 mediates ischemia/reperfusion injury in the kidney. J Clin Invest. 2005;115((10)):2894–903. doi: 10.1172/JCI22832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shigeoka AA, Holscher TD, King AJ, Hall FW, Kiosses WB, Tobias PS, et al. TLR2 is constitutively expressed within the kidney and participates in ischemic renal injury through both MyD88-dependent and -independent pathways. J Immunol. 2007;178((10)):6252–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roedig H, Nastase MV, Frey H, Moreth K, Zeng-Brouwers J, Poluzzi C, et al. Biglycan is a new high-affinity ligand for CD14 in macrophages. Matrix Biol. 2019;77:4–22. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lech M, Gröbmayr R, Ryu M, Lorenz G, Hartter I, Mulay SR, et al. Macrophage phenotype controls long-term AKI outcomes: kidney regeneration versus atrophy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25((2)):292–304. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013020152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elloumi N, Fakhfakh R, Abida O, Ayadi L, Marzouk S, Hachicha H, et al. Relevant genetic polymorphisms and kidney expression of toll-like receptor (TLR)-5 and TLR-9 in lupus nephritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2017;190((3)):328–39. doi: 10.1111/cei.13022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conti F, Spinelli FR, Truglia S, Miranda F, Alessandri C, Ceccarelli F, et al. Kidney expression of toll like receptors in lupus nephritis: quantification and clinicopathological correlations. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:7697592. doi: 10.1155/2016/7697592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nickerson KM, Christensen SR, Shupe J, Kashgarian M, Kim D, Elkon K, et al. TLR9 regulates TLR7- and MyD88-dependent autoantibody production and disease in a murine model of lupus. J Immunol. 2010;184((4)):1840–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bossaller L, Christ A, Pelka K, Nündel K, Chiang PI, Pang C, et al. TLR9 deficiency leads to accelerated renal disease and myeloid lineage abnormalities in pristane-induced murine lupus. J Immunol. 2016;197((4)):1044–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Celhar T, Yasuga H, Lee HY, Zharkova O, Tripathi S, Thornhill SI, et al. Toll-like receptor 9 deficiency breaks tolerance to RNA-associated antigens and up-regulates toll-like receptor 7 protein in Sle1 mice. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70((10)):1597–609. doi: 10.1002/art.40535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teichmann Ll, Schenten D, Medzhitov R, Kashgarian M, Shlomchik MJ. Signals via the adaptor MyD88 in B cells and DCs make distinct and synergistic contributions to immune activation and tissue damage in lupus. Immunity. 2013;38((3)):528–40. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang D, Xu J, Ren J, Ding L, Shi G, Li D, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells induce podocyte injury through increasing reactive oxygen species in lupus nephritis. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1443. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Umiker BR, Andersson S, Fernandez L, Korgaokar P, Larbi A, Pilichowska M, et al. Dosage of X-linked toll-like receptor 8 determines gender differences in the development of systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44((5)):1503–16. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Devaraj S, Tobias P, Kasinath BS, Ramsamooj R, Afify A, Jialal I. Knockout of toll-like receptor-2 attenuates both the proinflammatory state of diabetes and incipient diabetic nephropathy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31((8)):1796–804. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.228924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mudaliar H, Pollock C, Komala MG, Chadban S, Wu H, Panchapakesan U. The role of toll-like receptor proteins (TLR) 2 and 4 in mediating inflammation in proximal tubules. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;305((2)):F143–54. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00398.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feng Y, Yang S, Ma Y, Bai XY, Chen X. Role of toll-like receptors in diabetic renal lesions in a miniature pig model. Sci Adv. 2015;1((5)):e1400183. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1400183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gollapudi P, Yoon J-W, Gollapudi S, Pahl MV, Vaziri ND. Leukocyte toll-like receptor expression in end-stage kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2010;31((3)):247–54. doi: 10.1159/000276764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grabulosa CC, Manfredi SR, Canziani ME, Quinto BMR, Barbosa RB, Rebello JF, et al. Chronic kidney disease induces inflammation by increasing toll-like receptor-4, cytokine and cathelicidin expression in neutrophils and monocytes. Exp Cell Res. 2018;365((2)):157–62. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verzola D, Bonanni A, Sofia A, Montecucco F, D'Amato E, Cademartori V, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 signalling mediates inflammation in skeletal muscle of patients with chronic kidney disease. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2017;8((1)):131–44. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.González-Guerrero C, Cannata-Ortiz P, Guerri C, Egido J, Ortiz A, Ramos AM. TLR4-mediated inflammation is a key pathogenic event leading to kidney damage and fibrosis in cyclosporine nephrotoxicity. Arch Toxicol. 2017;91((4)):1925–39. doi: 10.1007/s00204-016-1830-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park HS, Kim EN, Kim MY, Lim JH, Kim HW, Park CW, et al. The protective effect of neutralizing high-mobility group box1 against chronic cyclosporine nephrotoxicity in mice. Transpl Immunol. 2016;34:42–9. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salama M, Elgamal M, Abdelaziz A, Ellithy M, Magdy D, Ali L, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 blocker as potential therapy for acetaminophen-induced organ failure in mice. Exp Ther Med. 2015;10((1)):241–6. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Volarevic V, Markovic BS, Jankovic MG, Djokovic B, Jovicic N, Harrell CR, et al. Galectin 3 protects from cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury by promoting TLR-2-dependent activation of IDO1/Kynurenine pathway in renal DCs. Theranostics. 2019;9((20)):5976–6001. doi: 10.7150/thno.33959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Conover MS, Hadjifrangiskou M, Palermo JJ, Hibbing ME, Dodson KW, Hultgren SJ. Metabolic requirements of Escherichia coli in intracellular bacterial communities during urinary tract infection pathogenesis. mBio. 2016;7((2)):e00104–16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00104-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yadav M, Zhang J, Fischer H, Huang W, Lutay N, Cirl C, et al. Inhibition of TIR domain signaling by TcpC: MyD88-dependent and independent effects on Escherichia coli virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6((9)):e1001120. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emal D, Rampanelli E, Claessen N, Bemelman FJ, Leemans JC, Florquin S, et al. Calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus impairs host immune response against urinary tract infection. Sci Rep. 2019;9((1)):106. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37482-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jayaraman PA, Devlin AA, Miller JC, Scholle F. The adaptor molecule Trif contributes to murine host defense during leptospiral infection. Immunobiology. 2016;221((9)):964–74. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Navarathna DH, Lionakis MS, Roberts DD. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase limits host immunity to control disseminated Candida albicans infections in mice. PLoS One. 2019;14((10)):e0223919. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh MV, Cicha MZ, Nunez S, Meyerholz DK, Chapleau MW, Abboud FM. Angiotensin II-induced hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy are differentially mediated by TLR3- and TLR4-dependent pathways. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2019;316((5)):H1027–38. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00697.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu D, Shi M, Bao J, Yu X, Li Y, Liu W. Genipin ameliorates hypertension-induced renal damage via the angiotensin II-TLR/MyD88/MAPK pathway. Fitoterapia. 2016;112:244–53. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alhasson F, Dattaroy D, Das S, Chandrashekaran V, Seth RK, Schnellmann RG, et al. NKT cell modulates NAFLD potentiation of metabolic oxidative stress-induced mesangial cell activation and proximal tubular toxicity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;310((1)):F85–101. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00243.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang C, Dong H, Chen F, Wang Y, Ma J, Wang G. The HMGB1-RAGE/TLR-TNF-α signaling pathway may contribute to kidney injury induced by hypoxia. Exp Ther Med. 2019;17((1)):17–26. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lehmann SM, Krüger C, Park B, Derkow K, Rosenberger K, Baumgart J, et al. An unconventional role for miRNA: let-7 activates toll-like receptor 7 and causes neurodegeneration. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15((6)):827–35. doi: 10.1038/nn.3113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fabbri M, Paone A, Calore F, Galli R, Gaudio E, Santhanam R, et al. MicroRNAs bind to toll-like receptors to induce prometastatic inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109((31)):E2110–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209414109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dasari P, Zola H, Nicholson IC. Expression of toll-like receptors by neonatal leukocytes. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22((2)):221–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Der Houwen TB, Dik WA, Goeijenbier M, Hayat M, Nagtzaam NMA, Van Hagen M, et al. Leukocyte toll-like receptor expression in pathergy positive and negative Behcet's disease patients. Rheumatology. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Terhorst D, Kalali BN, Weidinger S, Illig T, Novak N, Ring J, et al. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells from highly atopic individuals are not impaired in their pro-inflammatory response to toll-like receptor ligands. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37((3)):381–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hayashi F, Means TK, Luster AD. Toll-like receptors stimulate human neutrophil function. Blood. 2003;102((7)):2660–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bekeredjian-Ding I, Jego G. Toll-like receptors: sentries in the B-cell response. Immunology. 2009;128((3)):311–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03173.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jheng HF, Tsai PJ, Chuang YL, Shen YT, Tai TA, Chen WC, et al. Albumin stimulates renal tubular inflammation through an HSP70-TLR4 axis in mice with early diabetic nephropathy. Dis Model Mech. 2015;8((10)):1311–21. doi: 10.1242/dmm.019398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sawa Y, Takata S, Hatakeyama Y, Ishikawa H, Tsuruga E. Expression of toll-like receptor 2 in glomerular endothelial cells and promotion of diabetic nephropathy by Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide. PLoS One. 2014;9((5)):e97165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee D, Kang KS, Yu JS, Woo JY, Hwang GS, Eom DW, et al. Protective effect of Korean red ginseng against FK506-induced damage in LLC-PK1 cells. J Ginseng Res. 2017;41((3)):284–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]