Key Points

Question

Can a genomic biomarker estimate the risk of prostate cancer clinical end points in men who received salvage radiation for rising prostate-specific antigen levels after surgery?

Findings

In this ancillary study of 352 men randomized to placebo or hormone therapy in the NRG/RTOG 9601 clinical trial of salvage radiation, the Decipher genomic classifier was independently associated with the risk of metastasis, prostate cancer–specific mortality, and overall survival.

Meaning

These findings suggest that the Decipher genomic classifier is a promising biomarker to risk stratify men to better enable hormone therapy treatment decisions for biochemical recurrence of their prostate cancer after surgery.

This ancillary study of the NRG/RTOG 9601 randomized clinical trial assesses the validity of a genomic classifier to estimate the risk of distant metastasis after radical prostatectomy in patients with prostate cancer.

Abstract

Importance

Decipher (Decipher Biosciences Inc) is a genomic classifier (GC) developed to estimate the risk of distant metastasis (DM) after radical prostatectomy (RP) in patients with prostate cancer.

Objective

To validate the GC in the context of a randomized phase 3 trial.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This ancillary study used RP specimens from the phase 3 placebo-controlled NRG/RTOG 9601 randomized clinical trial conducted from March 1998 to March 2003. The specimens were centrally reviewed, and RNA was extracted from the highest-grade tumor available in 2019 with a median follow-up of 13 years. Clinical-grade whole transcriptomes from samples passing quality control were assigned GC scores (scale, 0-1). A National Clinical Trials Network–approved prespecified statistical plan included the primary objective of validating the independent prognostic ability of GC for DM, with secondary end points of prostate cancer–specific mortality (PCSM) and overall survival (OS). Data were analyzed from September 2019 to December 2019.

Intervention

Salvage radiotherapy (sRT) with or without 2 years of bicalutamide.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The preplanned primary end point of this study was the independent association of the GC with the development of DM.

Results

In this ancillary study of specimens from a phase 3 randomized clinical trial, GC scores were generated from 486 of 760 randomized patients with a median follow-up of 13 years; samples from a total of 352 men (median [interquartile range] age, 64.5 (60-70) years; 314 White [89.2%] participants) passed microarray quality control and comprised the final cohort for analysis. On multivariable analysis, the GC (continuous variable, per 0.1 unit) was independently associated with DM (hazard ratio [HR], 1.17; 95% CI, 1.05-1.32; P = .006), PCSM (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.20-1.63; P < .001), and OS (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.06-1.29; P = .002) after adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, Gleason score, T stage, margin status, entry prostate-specific antigen, and treatment arm. Although the original planned analysis was not powered to detect a treatment effect interaction by GC score, the estimated absolute effect of bicalutamide on 12-year OS was less when comparing patients with lower vs higher GC scores (2.4% vs 8.9%), which was further demonstrated in men receiving early sRT at a prostate-specific antigen level lower than 0.7 ng/mL (−7.8% vs 4.6%).

Conclusions and Relevance

This ancillary validation study of the Decipher GC in a randomized trial cohort demonstrated association of the GC with DM, PCSM, and OS independent of standard clinicopathologic variables. These results suggest that not all men with biochemically recurrent prostate cancer after surgery benefit equally from the addition of hormone therapy to sRT.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00002874

Introduction

Currently, the management of localized or recurrent prostate cancer is largely based on risk stratification using clinicopathologic variables incorporated into national and international consensus guidelines. However, numerous studies demonstrated that standard prognostic clinicopathologic variables, such as Gleason score, T stage, and prostate-specific antigen (PSA), have modest performance to accurately identify men with more biologically aggressive disease.1 There is a significant need to develop and incorporate into clinical practice the prognostic biomarkers that can add to or replace these risk stratification schemes to more accurately determine which tumors are indolent and which are biologically aggressive.

Decipher (Decipher Biosciences Inc), a 22-gene genomic classifier (GC) derived from a commercial, high-throughput, clinical-grade whole transcriptome profiling platform, was developed to improve the estimation of patient prognosis.2 The GC was developed in a radical prostatectomy (RP) cohort, and the signature was trained to predict the development of distant metastasis (DM). In validation studies using retrospective institutional cohorts, the GC was consistently superior in its prognostic and discriminatory ability when compared with clinicopathologic variables for multiple oncologic end points.3,4,5,6,7,8

However, to date and to our knowledge, no clinically available genomic biomarker has been validated in the context of a phase 3 randomized trial in prostate cancer. Therefore, this secondary analysis sought to clinically validate the GC in the NRG/RTOG 9601 randomized trial of men with recurrent prostate cancer after RP.9 It was hypothesized that the GC would independently predict the development of DM and could be used to help personalize the use of hormone therapy with salvage radiation therapy (sRT). Furthermore, it was hypothesized that the GC would also independently stratify the risk of prostate cancer–specific mortality (PCSM) and overall survival (OS).

Methods

Trial and Ancillary Project Details

The NRG/RTOG 9601 study was a double-blind trial conducted from March 1998 to March 2003 of men receiving sRT with either a placebo or 150 mg bicalutamide daily for 2 years (trial protocol available in Supplement 1).8 The trial was sponsored by the National Cancer Institute with original ethical approval and conducted through NRG Oncology/RTOG. Eligible patients were required to have recurrent disease after RP with a PSA of 0.2 to 4.0 ng/mL, pathologic T3 disease (tumor spread beyond the prostate) or T2 disease (tumor contained within the prostate) with a positive surgical margin and no evidence of nodal or metastatic disease. Salvage radiation therapy was delivered to the prostate bed at a dose of 64.8 Gy in 1.8 Gy per fraction using 2- or 3-dimensional radiotherapy techniques. All enrolled patients gave written informed consent obtained as documented in the original trial publication.8 Approval for this ancillary study (NRG-GU-TS002 CSC0075) was granted from the National Clinical Trials Network Core Correlative Sciences Committee (NCTN-CCSC). This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

RNA Processing and Analysis

After NCTN-CCSC approval, an NRG biobank pathologist (J.P.S.) performed a pathology review of all available RP samples, the highest-grade tumor focus was identified, and specimens from corresponding blocks or unstained slides were deidentified and sent to Decipher Biosciences Inc for RNA extraction. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue samples were taken from freshly cut tissue slides or punch biopsy samples from submitted RP blocks or were from archived unstained tissue slides submitted at the time of enrollment. Decipher Biosciences Inc was blinded to all patient, tumor, and outcomes data from the trial at this stage. Tumor RNA was extracted after macrodissection guided by a histologic review of a matched hematoxylin and eosin slide of the tumor lesion. For all cases analyzed, at least 0.5 mm2 of tumor with at least 60% tumor cellularity was required for the assay. For all samples, specimen selection, RNA extraction, and microarray hybridization were done in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified laboratory facility (Decipher Biosciences Inc). Quality control was performed using Affymetrix Power Tools (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and normalization was performed using the Single Channel Array Normalization algorithm.10 Per the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments and standard operating procedures, each sample was required to meet prespecified criteria from tumor sampling, RNA extraction, cDNA amplification, and a series of microarray quality control (QC) metrics. Of the 760 patients enrolled in NRG/RTOG 9601 between March 1998 and March 2003, 522 patients (69%) had RP tissue with sufficient tumor to attempt genomic profiling (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). A total of 486 of 760 samples (64%) had RNA of sufficient quality for microarray profiling and generation of a GC score. A subsequent 352 of 522 samples (67%) passed microarray QC and comprised the final cohort for analysis, with equal distribution between treatment arms (176 patients in each arm). The tissue blocks obtained from this trial were aged a median of 21 years (range, 17-29 years). Quality control pass rates were 87% from tissue blocks but only 32% from archived tissue slides submitted at the time of patient enrollment. Only samples that passed all of these criteria were included in the final analysis, but sensitivity analyses were also performed on the larger cohort of 486 samples with GC scores.

GC Scores

For samples passing QC, GC scores were calculated on a continuous scale from 0 (lowest) to 1 (highest). Each score is associated with the probability of 5-year metastasis. Previously locked commercial GC cut points of 0.45 and 0.60 used for clinical testing were applied to define the 3 GC risk groups (low, intermediate, and high).11 Additionally, the NCTN-CCSC–approved application prespecified a lower GC cut point of 0.40, the cut point originally used in analysis of older, archived samples.4 Once the GC scores were generated, the gene expression data were linked to the clinical and outcomes data kept by NRG for analysis.

End Points

The primary end point of this ancillary project was the independent association of the GC with the development of DM. This outcome was assessed with multivariable analyses (MVAs) after adjusting for patient, treatment, and tumor characteristics. Secondary end points to be analyzed in a similar fashion included PCSM and OS. All end points were defined per the NCTN-CCSC trial protocol. Exploratory end points included the ability of the GC to prognosticate time to second biochemical recurrence, metastasis-free survival (metastasis or death as events), and progression-free survival (biochemical recurrence, local failure, metastasis, or death as events).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis plan was prespecified, reviewed, and approved by the NCTN-CCSC. This plan included sample size justifications for both prognostic and predictive evaluations (ie, interaction test between the biomarker and hormone therapy) of GC that assumed a 30% sample loss rate and 12-year DM rate of 23% (eMethods in Supplement 2). These assumptions provided 90% power to detect an HR of 1.13 (for a 10% change in GC) using a 2-sided α of .05. With the additional assumptions of equal sample loss in both arms, a 12-year DM rate of 14.5% for the treatment vs 23% for the placebo arm, and that 50% of samples would have a higher GC (score >0.4), a GC by treatment interaction HR of 0.49 would result in only 35% power. Therefore, a priori, the study was sufficiently powered for the prognostic evaluation but underpowered for the predictive evaluation of GC response to treatment.

Test statistics for between-group comparisons were provided using the Fisher exact test or the χ2 test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum test or Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables across 2 or more groups, respectively.

Distant metastasis and PCSM rates were estimated in GC risk groups using cumulative incidence functions (treating death without an event and death from other causes as competing risks) and compared using the Gray test. Overall survival was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used for comparison. To assess the prognostic performance of GC, univariable analyses and MVAs of Cox proportional hazards models (nonevents treated as censored) with the Firth method to account for small event size (unless stated otherwise) were conducted in the full cohort and in subcohorts.12 Subgroup analyses were performed in the sRT-only cohort (defined a priori) and the early salvage (ie, patients enrolled with PSA<0.7 ng/mL) cohort. Adjusted variables defined a priori and used in the full-cohort MVAs were age, race/ethnicity, Gleason score, T stage, entry PSA, margin status, PSA nadir status, and treatment arm. Only variables that reached the significance level of P < .05 in univariable analyses were included in the subsequent MVAs to reduce the number of fitted variables; the same rule applied to subgroup analyses.

The interaction effect of treatment arm and GC was assessed for DM, PCSM, and OS without adjusting for any covariables. Similarly, interaction models of the treatment arm with GC risk groups (intermediate and high were combined owing to sample size constraints) were built to estimate event rates at 12 years, which then were used to calculate the difference in rates between treatment and placebo for each GC risk group (bootstrapped 95% CIs were obtained from 200 resampled data sets). Sensitivity analyses were carried out to ensure the robustness of our findings, including adjusting models with continuous variables, such as age, PSA, and GC score, as categorical; comparing results across Cox proportional hazards models, Cox proportional hazards models with the Firth method, and Fine-Gray models accounting for competing risks; and adjusting for the time from surgery to enrollment.

Statistical analyses were performed from September 2019 to December 2019 using R, version 3.5.1 (R Foundation). All statistical tests were 2-sided, and P values less than .05 were deemed statistically significant.

Results

Genomic classifier scores were generated from 486 of 760 randomized patients with a median follow-up of 13 years; samples from a total of 352 men (median age, 64.5 [interquartile range (IQR), 60-70] years; 314 White participants [89.2%]) passed microarray QC and comprised the final cohort for analysis. The 2 arms of the final cohort were balanced for all patient, clinical, and pathologic characteristics (176 patients in each arm) (Table 1) and were similar to both the overall trial cohort and patients whose samples did not pass all QC measures (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). The median GC scores of each arm of the final cohort were similar: 0.43 (IQR, 0.29-0.59) vs 0.44 (IQR, 0.27-0.57) for the control and investigational arms, respectively (Wilcoxon P = .29) (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2). The final cohort consisted of 148 of 352 GC low (42%), 132 of 352 GC intermediate (38%), and 72 of 352 GC high risk (20%). There was marked heterogeneity of genomic risk within all clinical and pathologic subgroups but no significant differences in GC distribution between the 2 study arms (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2).

Table 1. Demographic, Baseline Clinical, and Genomic Characteristics of the Analytic Cohorta.

| Characteristic | No. (%)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Treatment | Total | |

| Total | 176 (50.0) | 176 (50.0) | 352 |

| Age, y | |||

| Median (IQR) | 64 (60-69) | 65 (60-70) | 64.5 (60-70) |

| ≤49 | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (1.1) |

| 50-59 | 36 (20.5) | 42 (23.9) | 78 (22.2) |

| 60-69 | 94 (53.4) | 87 (49.4) | 181 (51.4) |

| 70-79 | 41 (23.3) | 44 (25.0) | 85 (24.1) |

| ≥80 | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | 4 (1.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 156 (88.6) | 158 (89.8) | 314 (89.2) |

| Hispanic | 1 (0.6) | 5 (2.8) | 6 (1.7) |

| African American | 13 (7.4) | 12 (6.8) | 25 (7.1) |

| Asian | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (1.1) |

| American Indian | 1 (0.6) | NA | 1 (0.3) |

| Other | 2 (1.1) | NA | 2 (0.6) |

| Karnofsky performance status score | |||

| 80 | 1 (0.6) | 3 (1.7) | 4 (1.1) |

| 90 | 51 (29.0) | 37 (21.0) | 88 (25.0) |

| 100 | 124 (70.5) | 136 (77.3) | 260 (73.9) |

| Gleason score | |||

| 2-6 | 51 (29.0) | 53 (30.1) | 104 (29.5) |

| 7 | 96 (54.5) | 93 (52.8) | 189 (53.7) |

| 8-10 | 29 (16.5) | 29 (16.5) | 58 (16.5) |

| Unavailable | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | |

| T stagec | |||

| T2 | 56 (31.8) | 62 (35.2) | 118 (33.5) |

| T3 | 120 (68.2) | 114 (64.8) | 234 (66.5) |

| Neoadjuvant hormone use | |||

| Yes | 13 (7.4) | 10 (5.7) | 23 (6.5) |

| Positive surgical margins | |||

| Yes | 132 (75.0) | 132 (75.0) | 264 (75.0) |

| PSA nadir after surgery | |||

| Median (IQR) | 0.1 (0.1-0.2) | 0.1 (0.1-0.2) | 0.1 (0.1-0.2) |

| <0.5 ng/mL | 161 (91.5) | 158 (89.8) | 319 (90.6) |

| ≥0.5 ng/mL | 15 (8.5) | 18 (10.2) | 33 (9.4) |

| PSA level at trial entry | |||

| Median (IQR) | 0.7 (0.38-1.2) | 0.675 (0.4-1.01) | 0.7 (0.4-1.1) |

| <0.7 ng/mL | 87 (49.4) | 88 (50.0) | 175 (49.7) |

| 0.7-1.5 ng/mL | 57 (32.4) | 62 (35.2) | 119 (33.8) |

| >1.5-4.0 ng/mL | 32 (18.2) | 26 (14.8) | 58 (16.5) |

| Follow-up, y | |||

| Median (IQR) | 13 (11.7-14.1) | 13 (11.4-14.1) | 13 (11.7-14.1) |

| GC score | |||

| Median (IQR) | 0.43 (0.287-0.59) | 0.44 (0.27-0.57) | 0.435 (0.28-0.58) |

Abbreviations: GC, genomic classifier; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

All patients with samples passed assay quality control metrics. There were no significant differences across the treatment arms.

Values are listed as No. (%) unless otherwise specified.

T2 prostate cancer indicates that the tumor is confined to the prostate. T3 prostate cancer indicates that the tumor has grown outside the prostate.

Association of 22-Gene GC With Oncologic Outcomes

The GC was analyzed as both a categorical (3 risk groups) and a continuous (scale, 0-1) variable. In univariable analyses, GC as a continuous variable (per 0.1 unit) was significantly associated with the primary end point, DM (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.12-1.41; P < .001), and the secondary end points, PCSM (HR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.30-1.77; P < .001) and OS (HR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.10-1.33; P < .001) (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). The GC categorical risk groups also significantly stratified the risk of DM (event rate: high, 15.3% [95% CI, 6.9%-23.7%]; intermediate, 8.7% [95% CI, 3.7%-13.6%]; low, 6.2% [95% CI, 2.2%-10.1%]; P = .003), PCSM (event rate: high, 9.8% [95% CI, 2.9%-16.8%]; intermediate, 2.4% [95% CI, 0.0%-5.0%]; low, 0.7% [95% CI, 0.0%-2.0%]; P < .001), and OS (event rate: high, 83.2% [95% CI, 74.4%-91.9%]; intermediate, 90.6% [95% CI, 85.5%-95.7%]; low, 94.5% [95% CI, 90.7%-98.2%]; P = .013) (Figure 1 and eFigure 3 in Supplement 2).

Figure 1. Cumulative Incidence Estimates of Distant Metastasis (DM) and Prostate Cancer–Specific Mortality (PCSM) and Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Overall Survival (OS) by Genomic Classifier (GC) Risk Group.

All patients with samples passing assay quality control metrics. The GC risk groups were categorized based on per-protocol cut points of 0.4 and 0.6. The numbers in parentheses are 95% CIs.

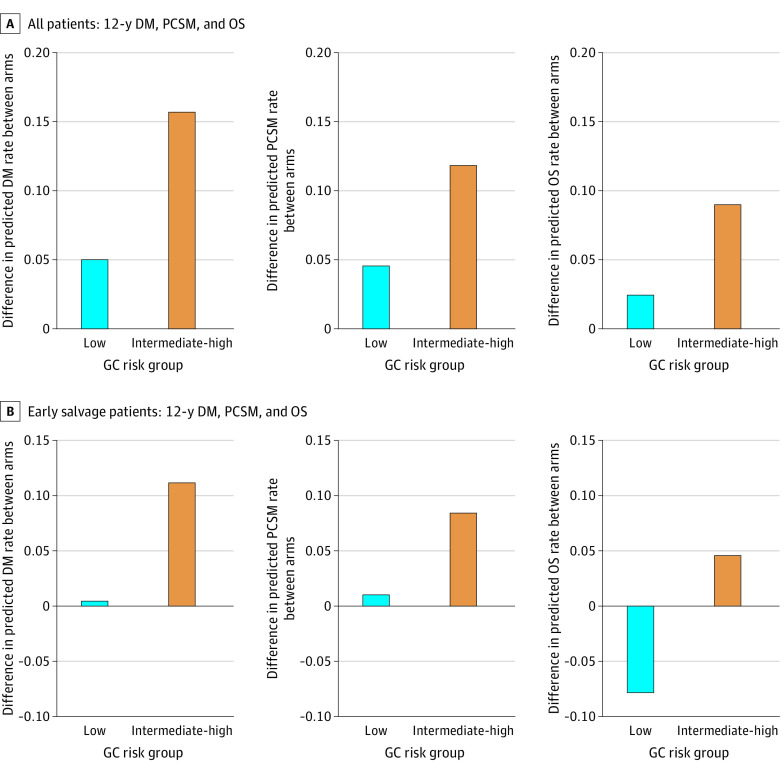

There was not a statistically significant interaction between GC score and hormone treatment effect for DM (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.82-1.30; P = .80), PCSM (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.81-1.57; P = .46), or OS (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.80-1.17; P = .76) (eTable 3 in Supplement 2). Despite this lack of significance, the estimated absolute benefits in DM, PCSM, and OS observed with hormone therapy were different by GC risk groups; the 12-year benefit from the addition of hormone therapy was approximately 3-fold greater in intermediate and high GC scores than in low GC scores (all patients, low vs intermediate and high: DM, 5.0% vs 15.7%; PCSM, 4.5% vs 11.8%; OS, 2.4% vs 8.9%) (Figure 2A and eTable 4 in Supplement 2). For example, the 12-year improvement in OS with the addition of hormone therapy in GC low scores was 2.4% compared with 8.9% for GC intermediate/high scores.

Figure 2. Difference Between Arms, by Genomic Classifier (GC) Risk Group, for Predicted Rates of Distant Metastasis (DM), Prostate Cancer–Specific Mortality (PCSM), and Overall Survival (OS) at 12 Years.

The top 3 panels (A) include all patients, whereas the bottom 3 panels (B) include early salvage patients only. Each bar height represents the difference in rates from subtracting the predicted rate in the treatment arm from the placebo arm (GC risk group: low = GC<0.45, intermediate-high = GC 0.45-1.0). A positive difference in rates indicates that there is a treatment benefit from bicalutamide. Individual predicted rates and bootstrapped 95% CIs are provided in eTable 4 in Supplement 2. Early salvage is defined as <0.7 ng/mL PSA at entry. PSA indicates prostate-specific antigen.

The GC score was prognostic in the subset of patients treated with earlier sRT when PSA was less than the median entry value (0.7 ng/mL) (eTable 5 in Supplement 2). The DM benefits from additional hormone therapy were estimated to be 0.4% vs 11.2% in low and higher GC risk groups, respectively (Figure 2B; eTable 4 in Supplement 2). The absolute effect of hormone therapy in low vs higher GC score on 12-year PCSM was 1.0% vs 8.4% and on OS was –7.8% vs 4.6%.

The GC was then analyzed both continuously and categorically, adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, Gleason score, T stage, margin status, entry PSA, and treatment arm. In the MVAs, continuous GC was independently associated with DM (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.05-1.32; P = .006), PCSM (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.20-1.63; P < .001), and OS (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.06-1.29; P = .002) (Table 2). The results were similar when GC was analyzed categorically (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Table 2. Multivariable Analysis of GC for Distant Metastasis, Death From Prostate Cancer, and Overall Survivala.

| Variable | DM | PCSM | OS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | ||

| GC score | 1.17 (1.05-1.32) | .006b | 1.39 (1.20-1.63) | <.001b | 1.17 (1.06-1.29) | .002b | |

| Treatment vs placebo | 0.62 (0.39-0.97) | .04b | 0.53 (0.30-0.92) | .02b | 0.82 (0.57-1.19) | .29 | |

| Age ≥65 vs <65, y | 1.30 (0.83-2.06) | .25 | 1.52 (0.88-2.66) | .14 | 1.95 (1.33-2.91) | <.001b | |

| African American vs non-African American | 0.88 (0.28-2.13) | .80 | 0.86 (0.17-2.73) | .83 | 1.35 (0.57-2.77) | .47 | |

| Gleason 8-10 vs ≤7 | 2.11 (1.24-3.47) | .007b | 2.53 (1.38-4.49) | .003b | 1.87 (1.20-2.85) | .007b | |

| T3 vs T2 | 1.42 (0.82-2.58) | .22 | 2.01 (0.97-4.62) | .06 | 1.24 (0.79-1.97) | .35 | |

| PSA level at trial entry | 1.16 (0.88-1.49) | .26 | 1.37 (1.01-1.80) | .04b | 1.08 (0.84-1.35) | .53 | |

| Positive surgical margins | 0.71 (0.44-1.16) | .17 | 1.26 (0.68-2.44) | .46 | 0.98 (0.64-1.53) | .92 | |

| Non-nadir vs nadir (<0.5 ng/mL) | 1.31 (0.62-2.51) | .46 | 2.10 (0.92-4.26) | .07 | 1.98 (1.13-3.30) | .02b | |

Abbreviations: DM, distant metastasis; GC, genomic classifier; OS, overall survival; PCSM, death from prostate cancer; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

One patient was dropped from the analyses owing to missing Gleason information. The median age of the analytic cohort was 65 years. Race/ethnicity, Gleason score, cancer stage, and nadir status were grouped according to the trial protocol. Hazard ratios of GC were per 0.1 unit increased.

P < .05.

Exploratory and Sensitivity Analysis

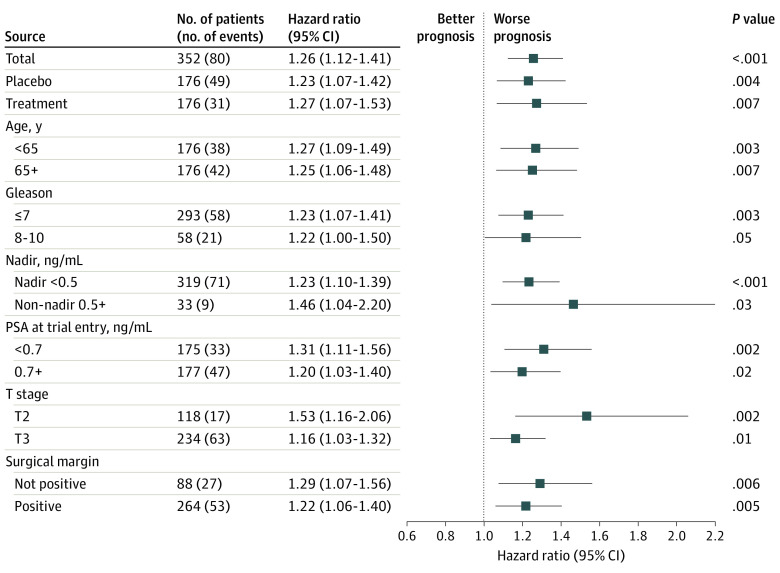

The GC score was prognostic also across other end points, including second biochemical recurrence (treatment arm: HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.10-1.39; P < .001), distant progression-free survival (treatment arm: HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.08-1.31; P < .001), and metastasis-free survival (treatment arm: HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.04-1.33; P = .008) (eFigure 4 in Supplement 2). Additionally, the GC score was consistently prognostic within all subgroups, including treatment arm (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.07-1.53; P = .007), age (<65 years, HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.09-1.49; P = .003; ≥65 years, HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.06-1.48; P = .007), Gleason score (Gleason ≤7, HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.07-1.41; P = .003; Gleason 8-10, HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.00-1.50; P = .05), surgical margin status (no margin, HR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.07-1.56; P = .006; positive margin, HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.06-1.40; P = .005), PSA nadir (<0.5 ng/mL, HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.10-1.39; P < .001), tumor stage (T2, HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.16-2.06; P = .002; T3, HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.03-1.32; P = .01), and entry PSA level (<0.7 ng/mL, HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.11-1.56; P = .002; ≥0.7 ng/mL, HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.03-1.40; P = .02) (Figure 3 and eTables 5 and 6 in Supplement 2 for early salvage subset and sRT-only arm, respectively) and with different modeling methods (eTable 7 in Supplement 2).

Figure 3. Prognostic Performance of Genomic Classifier (GC) for Distant Metastasis (DM) in Subgroups.

The forest plot summarizes the univariable Cox regression results of the GC continuous score (hazard ratio reported per 0.1-unit increase) in the full cohort (indicated by Total) or subcohorts including arm (placebo or treatment), age (<65 or ≥65 years), Gleason score (≤7 or 8-10), postoperative PSA nadir status (<0.5 ng/mL or ≥0.5 ng/mL), PSA at trial entry (<0.7 ng/mL or ≥0.7 ng/mL), pathologic stage (T2 or T3), and positive surgical margin (yes or no). The subgroups were predefined by the trial protocol. Race was not included owing to fewer than 5 events in the African American category. PSA indicates prostate-specific antigen.

Discussion

To date and to our knowledge, no multigene expression biomarker has been rigorously validated as a prognostic or predictive test in patients with prostate cancer who are receiving radical therapy.13 This circumstance has resulted in lack of complete support from consensus guideline panels for standard of care use of genomic biomarkers, given the potential for bias from institutional retrospective cohorts. The present study is, to our knowledge, the first prospectively designed validation study of a GC conducted from a large NCTN double-blinded randomized clinical trial in men receiving sRT with either placebo or bicalutamide daily for 2 years. In this study, the GC was prognostic for DM, PCSM, and OS when evaluated as a continuous score and as a 3-tier GC risk group system. The difference between GC low risk and higher risk groups for the prespecified primary end point of DM was large and statistically significant. Specifically, patients with intermediate and high GC scores had an 88% increased risk of DM vs those with low GC scores. The GC identified substantial heterogeneity within a given clinicopathologic subgroup, and many patients with adverse pathologic features harbored lower genomic risk. In MVAs, GC was independently prognostic.

In our current study, the GC was strongly and independently prognostic, though it did not have a statistically significant interaction with hormonal therapy. The final GC cohort was limited to 352 patients, and our prespecified statistical plan did not have adequate power to identify a statistical interaction between the GC and hormone therapy for any end point in the study. Although predictive biomarkers can help personalize therapeutic intervention,7,14 prognostic biomarkers can also identify patients at low risk of recurrence and those who are unlikely to experience meaningful clinical benefit from treatment intensification. This situation is illustrated by patients with lower GC scores having a 2.4% absolute improvement in 12-year OS compared with 8.9% in patients with higher GC scores. This approximate 4-fold difference may help guide shared decision-making. For some patients, the risk of toxic effects, cost, and possible effects on quality of life from long-term hormone therapy may erode further OS benefit. Patients with shorter comorbidity-adjusted life expectancy may also have lesser benefit. However, the estimated 8.9% absolute improvement in OS in patients with a higher GC score may affect the risk-benefit ratio to favor the addition of hormone therapy to sRT.

The importance of accurate prognostication perhaps is even greater in patients receiving earlier sRT at a PSA below 0.7 ng/mL. Indeed, a recent secondary analysis of RTOG 9601 demonstrated that pre-sRT PSA level in itself may be a prognostic biomarker for outcomes of antiandrogen treatment with sRT.7,15 This study demonstrates that within patients receiving earlier sRT, patients with higher GC scores derived an 11.2% improvement in 12-year DM and a 4.6% improvement in OS from the addition of hormone therapy. The CIs for these estimates cross 0% and are wide given the reduced sample size, but they illustrate the potential utility of personalizing shared decision-making beyond using PSA to drive hormone therapy utilization.

One challenge in the conduct of this study was the median age of the RP tissue being older than 20 years, which was reflected in the approximately 70% QC pass rate. Notably, the majority of the failures were from tissue cases submitted as unstained slides, suggesting that archived tissue blocks should be the preferred sample type for cooperative group biorepository initiatives. Importantly, the patient characteristics of the samples that did and did not pass QC were similar, reassuring that there was no selection bias introduced. However, it is possible that the age of the samples could shift the GC categorical cut points, and it is recommended that the GC be primarily interpreted on a continuous scale from 0 to 1. This maximizes statistical power and better assesses the relative risk increase across the GC scale.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this correlative analysis include the prospective, randomized, and double-blinded design of the NRG/RTOG 9601 trial, the long clinical follow-up, a well-balanced and profiled cohort, the stringent Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified laboratory facility procedures to profile the whole human transcriptome from clinical samples, and the NCTN-CCSC prespecified statistical plan to validate the GC. Limitations to this study include the fact that only a subset of clinical samples from the NRG/RTOG 9601 trial was available for profiling with the GC (31.3% of patient tissue was not available from the trial) and that one-third (or 22.4% of total trial) of the remaining clinical samples did not pass QC. As mentioned previously, this more limited sample size may explain the lack of a statistically significant interaction term observed between treatment and the GC. Ongoing randomized trials in the sRT setting have also prospectively incorporated GC testing (Decipher), seeking to validate these findings.16,17

Conclusions

In summary, the findings from this ancillary analysis of a randomized clinical trial represent the first validation in prostate cancer of a high-throughput, clinical-grade, whole transcriptome–based GC from a prospective randomized trial, and the findings add to the evidence base supporting the use of the GC to guide shared decision-making after RP. The results of this and other studies strongly suggest that not all men with biochemically recurrent prostate cancer after surgery derive equal absolute benefits from the addition of hormone therapy to sRT.

Trial Protocol

eFigure 1. Consort Diagram: Patient Sample Availability, Sample Quality and Follow-up Information of the Patients in the Study.

eFigure 2. Distributions of GC Scores by Arm, Pathologic Stage, and Gleason Score

eFigure 3. Cumulative Incidence Estimates of Distant Metastasis and Death From Prostate Cancer and Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Overall Survival by GC Risk Group

eFigure 4. Prognostic Performance of GC for All Endpoints in the Full Analytic Cohort and Each Arm

eTable 1. Demographic, Baseline Clinical and Genomic Characteristics in Different Patient Sample Groups

eTable 2. Univariable and Additional Multivariable Analyses of GC

eTable 3. Interaction Effect of Treatment Arm and GC

eTable 4. 12-Year Predicted Rates in Each Arm by GC Risk Group, Difference in Rate Between Arms and Bootstrapped 95% CI

eTable 5. Univariable and Multivariable Analyses of GC in the Early Salvage Cohort

eTable 6. Univariable and Multivariable Analyses of GC in the Placebo Arm

eTable 7. Model Comparison Across Cox PH With and Without Firth’s Method and Fine-Gray

eMethods. Analysis Codes

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Spratt DE, Zhang J, Santiago-Jiménez M, et al. Development and validation of a novel integrated clinical-genomic risk group classification for localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(6):581-590. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.2940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erho N, Crisan A, Vergara IA, et al. Discovery and validation of a prostate cancer genomic classifier that predicts early metastasis following radical prostatectomy. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooperberg MR, Davicioni E, Crisan A, Jenkins RB, Ghadessi M, Karnes RJ. Combined value of validated clinical and genomic risk stratification tools for predicting prostate cancer mortality in a high-risk prostatectomy cohort. Eur Urol. 2015;67(2):326-333. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.05.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karnes RJ, Bergstralh EJ, Davicioni E, et al. Validation of a genomic classifier that predicts metastasis following radical prostatectomy in an at risk patient population. J Urol. 2013;190(6):2047-2053. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karnes RJ, Choeurng V, Ross AE, et al. Validation of a genomic risk classifier to predict prostate cancer-specific mortality in men with adverse pathologic features. Eur Urol. 2018;73(2):168-175. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.03.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein EA, Yousefi K, Haddad Z, et al. A genomic classifier improves prediction of metastatic disease within 5 years after surgery in node-negative high-risk prostate cancer patients managed by radical prostatectomy without adjuvant therapy. Eur Urol. 2015;67(4):778-786. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao SG, Chang SL, Spratt DE, et al. Development and validation of a 24-gene predictor of response to postoperative radiotherapy in prostate cancer: a matched, retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(11):1612-1620. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30491-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spratt DE, Yousefi K, Deheshi S, et al. Individual patient-level meta-analysis of the performance of the decipher genomic classifier in high-risk men after prostatectomy to predict development of metastatic disease. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(18):1991-1998. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.2811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shipley WU, Seiferheld W, Lukka HR, et al. ; NRG Oncology RTOG . Radiation with or without antiandrogen therapy in recurrent prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(5):417-428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piccolo SR, Sun Y, Campbell JD, Lenburg ME, Bild AH, Johnson WE. A single-sample microarray normalization method to facilitate personalized-medicine workflows. Genomics. 2012;100(6):337-344. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2012.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Den RB, Santiago-Jimenez M, Alter J, et al. Decipher correlation patterns post prostatectomy: initial experience from 2 342 prospective patients. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2016;19(4):374-379. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2016.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Firth D. Bias reduction of maximum likelihood estimates. Biometrika. 1993;80:27-38. doi: 10.1093/biomet/80.1.27 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Amico AV. Decipher postprostatectomy: is it ready for clinical use? J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(18):1976-1977. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.8486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao SG, Chang SL, Erho N, et al. Associations of luminal and basal subtyping of prostate cancer with prognosis and response to androgen deprivation therapy. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(12):1663-1672. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dess RT, Sun Y, Jackson WC, et al. Association of presalvage radiotherapy PSA levels after prostatectomy with outcomes of long-term antiandrogen therapy in men with prostate cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(5):735-743. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antiandrogen therapy and radiation therapy with or without docetaxel in treating patients with prostate cancer that has been removed by surgery. Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT03070886. Updated December 9, 2020. Accessed December 30, 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03070886

- 17.Biomarker trial of apalutamide and radiation for recurrent prostate cancer (balance). Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT03371719. Updated May 21, 2020. Accessed December 30, 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03371719

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eFigure 1. Consort Diagram: Patient Sample Availability, Sample Quality and Follow-up Information of the Patients in the Study.

eFigure 2. Distributions of GC Scores by Arm, Pathologic Stage, and Gleason Score

eFigure 3. Cumulative Incidence Estimates of Distant Metastasis and Death From Prostate Cancer and Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Overall Survival by GC Risk Group

eFigure 4. Prognostic Performance of GC for All Endpoints in the Full Analytic Cohort and Each Arm

eTable 1. Demographic, Baseline Clinical and Genomic Characteristics in Different Patient Sample Groups

eTable 2. Univariable and Additional Multivariable Analyses of GC

eTable 3. Interaction Effect of Treatment Arm and GC

eTable 4. 12-Year Predicted Rates in Each Arm by GC Risk Group, Difference in Rate Between Arms and Bootstrapped 95% CI

eTable 5. Univariable and Multivariable Analyses of GC in the Early Salvage Cohort

eTable 6. Univariable and Multivariable Analyses of GC in the Placebo Arm

eTable 7. Model Comparison Across Cox PH With and Without Firth’s Method and Fine-Gray

eMethods. Analysis Codes

Data Sharing Statement