Abstract

Background

CRISPR-Cas genome editing technologies have revolutionized biotechnological research particularly in functional genomics and synthetic biology. As an alternative to the most studied and well-developed CRISPR/Cas9, a new class 2 (type V) CRISPR-Cas system called Cpf1 has emerged as another versatile platform for precision genome modification in a wide range of organisms including filamentous fungi.

Results

In this study, we developed AMA1-based single CRISPR/Cpf1 expression vector that targets pyrG gene in Aspergillus aculeatus TBRC 277, a wild type filamentous fungus and potential enzyme-producing cell factory. The results showed that the Cpf1 codon optimized from Francisella tularensis subsp. novicida U112, FnCpf1, works efficiently to facilitate RNA-guided site-specific DNA cleavage. Specifically, we set up three different guide crRNAs targeting pyrG gene and demonstrated that FnCpf1 was able to induce site-specific double-strand breaks (DSBs) followed by an endogenous non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) DNA repair pathway which caused insertions or deletions (indels) at these site-specific loci.

Conclusions

The use of FnCpf1 as an alternative class II (type V) nuclease was reported for the first time in A. aculeatus TBRC 277 species. The CRISPR/Cpf1 system developed in this study highlights the feasibility of CRISPR/Cpf1 technology and could be envisioned to further increase the utility of the CRISPR/Cpf1 in facilitating strain improvements as well as functional genomics of filamentous fungi.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12896-021-00669-8.

Keywords: CRISPR/Cpf1, pyrG, 5-FOA, FnCpf1, Gene editing, Filamentous fungi, Aspergillus

Background

Filamentous fungi are of great value in the commercial production of enzymes and heterologous proteins [1, 2], a wide range of primary and secondary metabolites such as organic acids and pharmaceuticals [3, 4], as well as bio-based chemicals, and biofuels [5, 6]. One of the ways to increase the fungi potential in commercial applications is by means of strain improvement via genetic engineering [7]. However, the conventional genetic engineering tools via classical mutagenesis and homologous recombination remain challenging due to additional complexity and time, as well as low efficiency, particularly in targeting multiple genes [8]. Therefore, the development of versatile genetic tools, e.g., CRISPR-based, for filamentous fungi modification would be of great value [9].

The rapid technological advances in low-cost high-throughput sequencing, as well as in CRISPR-Cas genome engineering technology, have accelerated research in several industrially and medically important Aspergillus species [10, 11]. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated proteins (Cas), evolved as a defense system of bacteria to invading viruses. This system has become a versatile tool to solve the problem of low gene editing frequency in filamentous fungi [12]. CRISPR/Cas, particularly CRISPR/Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes, has become a tool in basic research, genetic improvement, and metabolic engineering [13]. In this system, a guide RNA (gRNA) or CRISPR RNA (crRNA) is used to direct Cas9 which targets sequence-specific DNA according to two simple rules: Watson-Crick base pairing between DNA target with the 5′-end guide sequence of crRNA, and the presence of a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) 5′-NGG in the DNA target [14, 15]. Recently, applications of CRISPR/Cas9 in filamentous fungi have been shown in several fungal strains, e.g., Aspergillus fumigatus [16], Aspergillus oryzae [17], Aspergillus niger [7, 9, 18–20], Aspergillus nidulans [21, 22], Trichoderma reesei [23], Neurospora crassa [24], Ganoderma lucidum [25], and Myceliophthora thermophila [26]. In addition to Cas9 from S. pyogenes, Cpf1s derived from Francisella tularensis subsp. novicida U112 (FnCpf1), Acidaminococcus sp. BV3L6 (AsCpf1), and Lachnospiraceae bacterium (LbCpf1), are additional tools for genome editing. Cpf1 is distinct from Cas9 in terms of PAM sequence, structure of the guide RNA, and the DNA cleavage position [27].

CRISPR/Cpf1 is characterized as a novel class 2 (type V) system with distinct features compared to Cas9 [28]. It is a single RNA-guided endonuclease which recognizes a thymidine-rich protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) and produces staggered cuts distal to the PAM site [29]. This type V CRISPR/Cpf1 system was first harnessed and shown to have robust genome editing activity in mammalian cell lines [27], as well as targeted mutations in plants and other eukaryotic cells [30]. Interestingly, Cpf1 is a dual nuclease that not only cleaves target DNA but also processes its own crRNA array [29, 31]. CRISPR/Cpf1-mediated DNA cleavage is guided by a short single crRNA (42–44 nt), in contrast to Cas9 that uses both crRNA and tracrRNA. More importantly, Cpf1 makes a staggered DNA double-stranded break resulting in a five-nucleotide 5′-overhang distal to the PAM site [29], whereas Cas9 creates blunt ends proximal to the PAM site [15]. However, both Cas9 and Cpf1 need a seed sequence at the PAM-proximal side of the protospacers, which is critical for DNA recognition and cleavage. With these advantages, Cpf1 system has been used for multiplex gene editing in mammalian cells, where up to four genes were simultaneously edited using just a single crRNA array spaced by direct repeats (DR) [29].

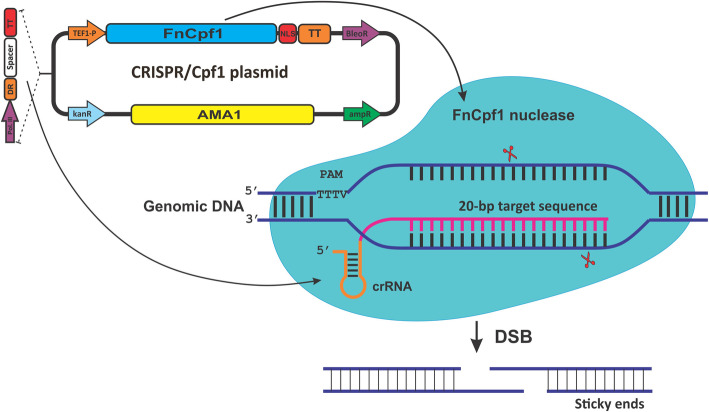

Cpf1 nuclease and the crRNA are two essential components in the formation of an adjustable CRISPR toolbox for genetic manipulation (Fig. 1). In general, Cpf1 expression is driven by an RNA polymerase II promoter [32]. The guide RNAs are noncoding small RNAs with guide sequence at their 3′-end crRNA and are naturally expressed using an RNA polymerase III (Pol III) promoter [33]. However, due to the complexity and uncertainty of genome information, some endogenous Pol III promoters from filamentous fungi are difficult to identify or are not suitable for crRNA transcription [12]. Therefore, suitable crRNA expression cassettes are needed to construct efficient CRISPR-based tools. Until recently, several methods have been developed to enhance the expression of crRNAs by engineering different RNA processing machineries, including a self-cleavable ribozyme from a virus [34], the endogenous tRNA processing enzymes [35], and pre-crRNA array consisting of direct repeats [29]. These systems are used to generate crRNAs from a single primary polycistronic transcript driven by either Pol II or Pol III promoter. Among these methods, a single pre-crRNA array and a tRNA-based CRISPR system have been shown to boost multiplex genome-editing capability and efficiency without introducing exogenous ribonucleases or additional tracrRNA in the CRISPR/Cas9 system [21].

Fig. 1.

Schematic of CRISPR/Cpf1 in a single-plasmid system for use in fungal genome engineering application. In this study, FnCpf1 and crRNA are expressed under A. nidulans TEF1 Pol II promoter and A. fumigatus U3 Pol III promoter, respectively, to edit genome of the wild-type strain of A. aculeatus TBRC 277

Over the past several years, various studies have demonstrated the great potential of CRISPR/Cpf1 as a tool for genome engineering, owing to user-designated site specificity of Cpf1 endonuclease activity and the simplicity of crRNA designs [27, 30]. Since the first harnessing of Cpf1 in human and animal cell lines [27], until recenty, AsCpf1 and LbCpf1 were reported to effectively catalyze oligonucleotide-mediated genomic site-directed mutagenesis and simultaneous gene deletions/insertions in a few filamentous fungi [36–38]. However, there have been no reports for the use of FnCpf1 from F. tularensis subsp. novicida U112 for genome editing in Aspergillus filamentous fungus despite its successful application in yeast [39–41]. Here, we established a single vector for the CRISPR/Cpf1 platform derived from FnCpf1 and a crRNA with the endogenous tRNA-processing system for CRISPR-mediated gene editing in Aspergillus aculeatus TBRC 277, a wild-type filamentous fungus. As a proof of principle, pyrG gene was used as the target gene for the CRISPR/Cpf1-mediated gene editing to generate uracil auxotrophic fungi.

Results

Construction of CRISPR/Cpf1 plasmid backbone

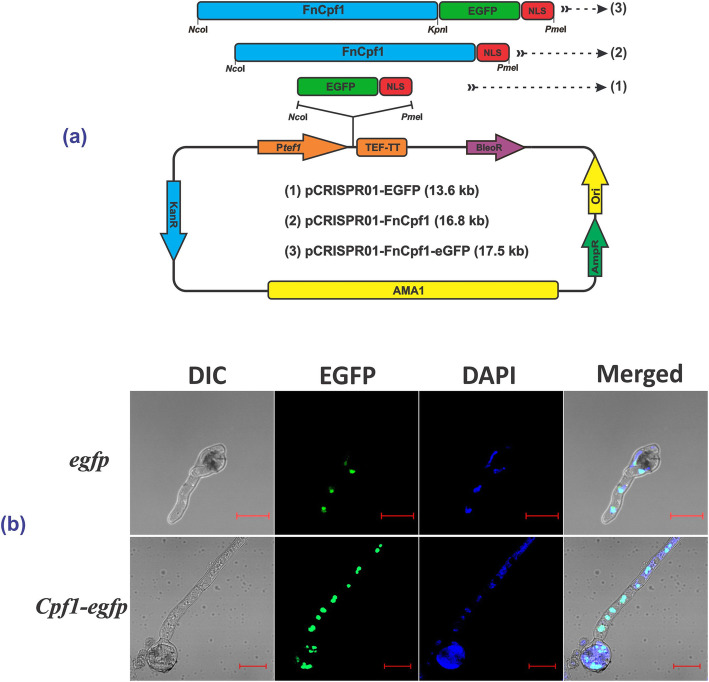

To establish the CRISPR/Cpf1 system in A. aculeatus TBRC 277 (Fig. 2a), an expression plasmid carrying the PTEF1-Cpf1-TEF1TT cassette and bleomycin selection marker was initially constructed. For Cpf1 gene, we codon-optimized the F. tularensis subsp. novicida Cpf1, so called FnCpf1, and attached a SV40 nuclear localization signal (NLS) fragment at the C-terminal to ensure successful nuclear compartmentalization in the fungal host. Specifically, construction of CRISPR/Cpf1 backbone carrying 5.5 kb autonomously replicating plasmids (AMA1) was successfully obtained by removing Cas9 from pFC333 plasmid [22], followed by MCS insertion that allows for expression of a 3.93 kb Cpf1-SV40 NLS gene fusion controlled by a constitutive A. nidulans TEF1 promoter. The successfully constructed plasmid, referred to as pCRISPR0 (Supplementary Fig. S1), was verified by Sanger sequencing. Then, insertion of kanamycin resistant gene cassette at the BglII-site was performed. This was confirmed by positive selection on LB agar containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin, as well as 25 μg/ml ampicillin; and also by HindIII digestion of recombinant plasmids. The obtained plasmid was named pCRISPR01 (Supplementary Fig. S1) and used throughout this study as the vector backbone for FnCpf1 and crRNA expressions.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of vector constructions for heterologous FnCpf1 expression and confocal microscopy assessment of the subcellular localization of the recombinant eGFP and Cpf1-EGFP fusion proteins in A. aculeatus TBRC 277. a The constructed vectors of (1) pCRISPR01-EGFP, expression of enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP), to test the tef1 promoter activity, (2) pCRISPR01-FnCpf1, for subsequent crRNA cassette insertion carrying a protospacer pyrG-targeted locus, (3) pCRISPR01-FnCpf1-EGFP, expression of Cpf1-EGFP, to detect Cpf1 fusion protein. b Subcelullar localization of FnCpf1 as EGFP-fused protein in A. aculeatus TBRC 277. Nuclei were visualized by DAPI staining (blue). Scale bar = 10 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein

Expression of codon-optimized eGFP and eGFP-Cpf1 in A. aculeatus TBRC 277

To test the expression and localization of the recombinant FnCpf1, the enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) and FnCpf1-eGFP fusion, with attached SV40 NLS, were used as the gene reporter. These were constructed by ligation of each DNA fragment to the NcoI/PmeI-site of pCRISPR01, yielding pCRISPR01-eGFP and pCRISPR01-FnCpf1-eGFP plasmids, respectively. The positive clones of each construct were confirmed by restriction analyses and further verified by sequencing. The obtained vectors, pCRISPR01-eGFP and pCRISPR01-FnCpf1-eGFP, were individually transformed into A. aculeatus TBRC 277 host. Positive transformants were further confirmed by colony PCR, followed by single spore isolation hereafter referred to as egfp and Cpf1-egfp accordingly.

The expression of eGFP and Cpf1-eGFP was detected after culturing TBRC 277 transformants in PDB for 24 h. Western blot detected specific protein bands of approximately 28 kDa and 180 kDa as predicted for eGFP and Cpf1-eGFP, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S2), suggesting that codon-optimized FnCpf1 was expressed in A. aculeatus TBRC 277. Additionally, to investigate whether the SV40 nuclear localization signal targeted FnCpf1 to the nucleus, the transformants were further assessed using confocal microscopy. The result showed that both transformants, egfp and Cpf1-egfp, showed green fluorescence signal when compared to the WT, after overnight incubation in PDB medium with bleomycin. Furthermore, these recombinant fungi were also stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and showed that the majority of the eGFP signals were overlapped with nuclei, suggesting that FnCpf1 correctly localized to the nucleus of A. aculeatus TBRC 277 (Fig. 2b). Finally, to obtain the expression vector for further genome engineering in TBRC 277, we also cloned just FnCpf1-NLS without eGFP to generate pCRISPR01-FnCpf1 plasmid.

Construction of guide RNA (crRNA)

CRISPR/Cpf1 system requires crRNA consisting of a 20-bp direct repeat (DR) followed by a 20–23 bp protospacer to direct Cpf1 to cleave sequence-specific target [41]. In this study, pyrG, an essential gene for the biosynthesis of uridine, was chosen as the target gene. As pyrG mutants undergo auxotrophic selection, its inactivation can be observed by growing transformants in minimal medium containing 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) [42, 43]. PyrG converts 5-FOA into fluoroorotidine monophosphate which is subsequently converted into fluorodeoxyuridine by ribonuclease reductase. Fluorodeoxyuridine is a pyrimidine analog that is rapidly converted to 5-fluorouracil, a suicide inhibitor of the thymidylate synthase, and therefore inhibits nucleic acid synthesis, leading to cell death; however, 5-FOA is non-lethal in the absence of pyrG [9, 44].

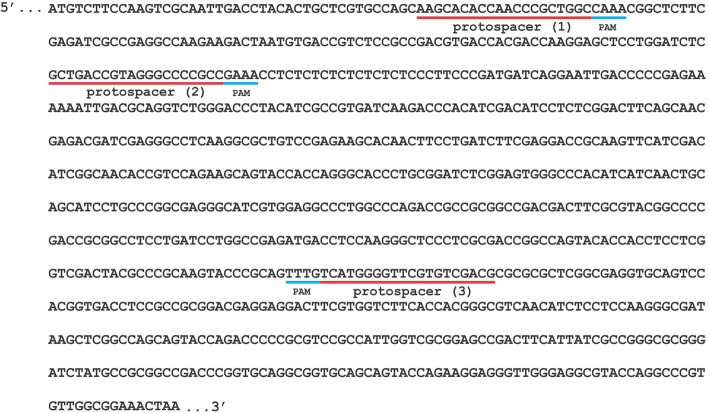

To perform this experiment, first, we needed to validate the sequence of A. aculateus TBRC 277 pyrG gene from the genomic draft sequence as generated by Next Generation Sequencing (NGS). The pyrG gene was successfully PCR amplified and sequenced (Fig. 3). The 915-bp amplified sequence was identified to encode orotidine 5′-phosphate decarboxylase (pyrG); it showed 93.63% sequence identity to A. aculeatus ATCC 16872 and had a 81-bp putative intron at the positions 158–238. Secondly, since FnCpf1 could be programmed to edit multiple target sites [29], this aspect was tested by selecting three out of eight predicted protospacers with the following criteria: no off-targets and highest specificity score (100%). Three protospacer guide sequences were obtained targeting positions 59-bp (pyrG-1), 167-bp (pyrG-2), and 648-bp (pyrG-3) downstream of the pyrG start codon.

Fig. 3.

The complete sequence of pyrG gene of A. aculeatus TBRC 277 (GenBank accession number MN364695). The locations of the three selected protospacers are indicated by the red lines, with the corresponding 5′-TTTN-3′ PAM in blue (putative intron 158–238; 81 bp)

Next, due to the lack of well-identified RNA Pol III promoters in A. aculeatus, we instead employed a U3 Pol III promoter derived from A. fumigatus to generate a single crRNA construct, i.e. a 182-bp crRNA-flanking tRNA fusion transcript (GenBank KT031983.1) [21]. Using this approach, the endogenous tRNA processing system was expected to cleave both ends of the tRNA precursor and release a single crRNA with the aid of RNAses Z and P [35]. In this study, U3 Pol III promoter and its terminator, together with tRNA-sgRNA(Cas9)-tRNA motif originating from pFC902, were successfully amplified and inserted into pJET1.2B resulting in pJET-U3P sgRNA (Table 1). This plasmid served as a template for the subsequent PCR reactions to generate six DNA fragments, in which each of the associated fragments were assembled with BglII-cut pOK12 by Gibson Assembly (see Methods). The obtained tRNA-crRNA-tRNA Cpf1-associated cassettes in pOK12 specifically referred to as crRNA-tRNA-pyrG-1, crRNA-tRNA-pyrG-2, and crRNA-tRNA-pyrG-3 which corresponded to the sequence-specific protospacers pyrG-1, pyrG-2, and pyrG-3, respectively. To finalize the CRISPR/Cpf1 construction, each of the purified crRNA-pyrG cassettes successfully incorporated the BglII-cut pCRISPR01-FnCpf1 to obtain the plasmid constructs named pCRISPR01-FnCpf1-pyrG-1, pCRISPR01-FnCpf1-pyrG-2, and pCRISPR01-FnCpf1-pyrG-3. All of these plasmids were verified by sequencing and by BglII digestions, which generated 16.8-kb and 0.9-kb DNA fragments representing the vector pCRISPR01-FnCpf1 and crRNA-pyrG inserts, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Table 1.

Plasmids and fungal strain used in this study

| Plasmids/Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmid | ||

| pFC902 | AmpR, pyrG, AMA1, U3-AF crRNA Cas9 | [21] |

| pJET1.2B-KmR | AmpR, kanR | This study |

| pJET-U3P sgRNA | AmpR, U3-AF sgRNA Cas9 | This study |

| pFC333 | AmpR, bleR, AMA1, TEF-Cas9 | [22] |

| pCRISPR0 | AmpR, bleR, AMA1 | This study |

| pCRISPR01 | AmpR, bleR, kanR, AMA1 | This study |

| pCRISPR01-eGFP | AmpR, bleR, kanR, AMA1, TEF1-EGFP | This study |

| pCRISPR01-FnCpf1 | AmpR, bleR, kanR, AMA1, TEF1-FnCpf1 | This study |

| pCRISPR01-FnCpf1-eGFP | AmpR, bleR, kanR, AMA1, TEF1-Cpf1-EGFP fusion | This study |

| pOK-U3P crRNA pyrG-1 | KanR, U3-AF crRNA-pyrG-1 | This study |

| pOK-U3P crRNA pyrG-2 | KanR, U3-AF crRNA-pyrG-2 | This study |

| pOK-U3P crRNA pyrG-3 | KanR, U3-AF crRNA-pyrG-3 | This study |

| pCRISPR01-FnCpf1-pyrG-1 | AmpR, bleR, kanR, AMA1, TEF-Cpf1, crRNA-pyrG-1 | This study |

| pCRISPR01-FnCpf1-pyrG-2 | AmpR, bleR, kanR, AMA1, TEF-Cpf1, crRNA-pyrG-2 | This study |

| pCRISPR01-FnCpf1-pyrG-3 | AmpR, bleR, kanR, AMA1, TEF-Cpf1, crRNA-pyrG-3 | This study |

| Strain | ||

| A. aculeatus TBRC 277 | Wild type | [1] |

CRISPR-crRNA complex induced pyrG-targeted gene disruption in A. aculeatus TBRC 277

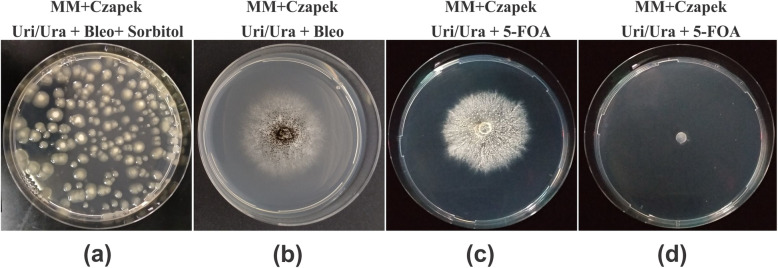

This study relies on the ability of Cpf1/crRNA-complex targeting pyrG locus to induce DSB, followed by NHEJ-repair mechanism. While some methods employ either Cas9 or Cpf1 expression in vivo but crRNA preparation in vitro which requires laborious steps for crRNA transcript preparation as well as an additional transformation step when introducing the crRNA. This leads to low transformation efficiencies due to crRNA stability issues [9, 14]. We therefore opted for in vivo preparation both of crRNA and Cpf1 in a single plasmid (see Methods). To test whether heterologous expression of the CRISPR/Cpf1 system is able to induce pyrG-targeted DSB in A. aculeatus TBRC 277 chromosome, as well as to explore the general utility of RNA-guided genome editing in fungal cells, three pCRISPR01-FnCpf1-pyrGs plasmids expressing Cpf1 and three different crRNA guides were independently transformed into A. aculeatus TBRC 277 protoplasts. Next, pyrG-mutant selection was performed by a two-step selection by first randomly selecting bleomycin-resistant colonies (Fig. 4a) and re-culture the colonies on new MM+Czapek-Dox plates with bleomycin and Uri/Ura supplementation, referred as the primary selection plate, but in the absence of sorbitol (Fig. 4b). Then, the colonies were grown on the secondary MM+Czapek-Dox plates supplemented with Uri/Ura as well as 5-FOA (Fig. 4c). The colonies that survived on this medium were considered mutant auxotroph [45]. For a negative control, the protoplast was transformed with empty vector or only Cpf1-bearing plasmid, and no colony was observed on the secondary selection plates (Fig. 4d). Our preliminary study showed that selective medium for protoplast-mediated transformation comprised of a mixture of sorbitol and 5-FOA gave rise to false-positives. Therefore, a two-step selection was required to remove fungal clones without the CRISPR plasmid. Using this approach, several bleomycin-resistant colonies obtained from the primary selection were not viable on secondary selective medium containing 5-FOA considered as non-mutated pyrG transformants.

Fig. 4.

An example of A. aculeatus TBRC 277 protoplasts transformed with CRISPR/Cpf1 plasmids. a pCRISPR01-FnCpf1-pyrGs (with crRNA specific targeting pyrG gene) on primary selective transformation medium containing 1.2 M sorbitol + 10 mM uri/ura + 50 μg/ml bleomycin, b a single colony selected from panel a, was then cultured on new minimal medium containing 10 mM uri/ura+ 50 μg/ml bleomycin, (c) secondary selection from panel b, re-cultured on minimal medium containing 10 mM uri/ura and 1.5 mg/ml 5-FOA. d pCRISPR01-FnCpf1 encoding only Cpf1 (without crRNA targeting pyrG), after growing on secondary selective medium containing 5-FOA, no colony was observed (control). Uri: uridine, Ura: uracil

Additionally, we also tested the transformation efficiency of Cpf1-bearing plasmids (in pCRISPR01-FnCpf1) which was 30 colonies/μg of DNA (Supplementary Fig. S4). This was slightly lower than that of the empty vector without Cpf1 (37.5 colonies/μg of plasmid DNA). This may be due to size of the plasmid since the Cpf1-bearing plasmid is approximately 4–5 kb larger. However, the effect of the constitutive Cpf1 expression from the AMA1-based plasmid may also contribute to the minor difference in transformation efficiency. Similar results were also reported in A. nidulans [36], and Ashbya gossypii [37] expressing LbCpf1. However, the potential toxicity effect of FnCpf1 was reported in yeast expressing multicopy plasmid [40].

To confirm whether the obtained colonies were auxotrophic mutants, PCR was performed to detect the presence of introduced exogenous CRISPR plasmid followed by sequencing of the pyrG gene. Using this approach, each randomly selected clones exhibited the presence of indels with 100% efficiency in every pyrG locus (Supplementary Table S1). Sequencing of the pyrG-specific locus revealed that three out of ten randomly selected mutant of each auxotroph contained pyrG indels (Fig. 5). These results indicated that Cpf1-crRNA complex induces DSB and endogenous error-prone repair that leads to indels of the pyrG gene in A. aculeatus TBRC 277.

Fig. 5.

Indels of pyrG gene in A. aculeatus TBRC 277 genome transformed with CRISPR/Cpf1 plasmids with three different crRNAs. Red arrow indicates putative cleavage sites; red dashes, deleted bases; red bases, insertions or mutations

Moreover, these DNA sequences were further analyzed. The results showed that mutants carrying either crRNA-pyrG-1 or crRNA-pyrG-2, typically had small insertions or deletions in the range of 2–6 bp and 7–16 bp, respectively. Interestingly, in a mutant carrying crRNA-pyrG-1, we noticed a 6-bp insertion in the exon of the pyrG-targeting cleavage site; this small in-frame insertion somehow could abolish PyrG activity. Additionally, for mutants carrying crRNA-pyrG-3, their deletions were in the range of 23–28 bp. These similar observations were also reported in other fungi [17, 23], plant [46], and animal cell line [27]. However, large DNA insertions with sizes greater than 100-bp were also found in which polyketide synthase gene (pksP) was targeted in A. fumigatus [16].

Discussion

CRISPR-Cas based systems have been broadly applied for use in targeted genome modification of cells or organisms due to their programmable sequence specificity. More recently, the CRISPR-Cas based system is no longer limited to Cas9 from S. pyogenes. As an alternative to Cas9, two Cas nuclease genes originating from Acidominococcus and Lachnospiraceae that belong to the Cpf1 family have been reported [27]. The introduction of CRISPR/Cpf1 system provides another option to the CRISPR toolbox [47]. So far, applications of CRISPR-Cas in filamentous fungi have focused mostly on Cas9 [28, 32, 48]. Here, we presented data of another type of Cpf1, called FnCpf1, and demonstrated the NHEJ pathway involvement in the repair of Cpf1-induced DNA DSBs in a non-model filamentous fungus, A. aculeatus TBRC 277.

The success of genome editing by CRISPR/Cpf1 system requires the heterologous expression of the codon-optimized Cpf1 gene fused with a NLS (PKKKRKV) to efficiently target the fused protein into the cell nucleus. To date, studies of the CRISPR/Cas9 system have been applied for genome engineering applications in various filamentous fungi such as A. fumigatus [16], A. oryzae [17], A. niger [7, 9, 18–20], A. nidulans [21, 22], T. reesei [23], N. crassa [24], G. lucidum [25], and M. thermophila [26]. These studies were performed by taking advantage of the Cas9 in vivo expression strategy using various types of promoters such as tef1, gpdA, trpC, pdc, and cbh1. Until recently, for CRISPR/Cpf1 system, only LbCpf1 from L. bacterium and AsCpf1 from Acidaminococcus sp. were reported to effectively catalyze oligonucleotide-mediated genomic site-directed mutagenesis in the filamentous fungi A. nidulans and M. thermophila, respectively [36, 38].

crRNA together with FnCpf1 were expressed via a single vector in the host cell, hence, it is not necessary for in vitro crRNA preparation which is laborious and time consuming [12]. In this study, to increase the ability of A. fumigatus U3 Pol III promoter to drive the functional transcription of crRNA, we chose a tRNA-processing system to yield a mature crRNA transcript rather than introducing any additional RNases along with Cpf1/crRNA components. This strategy was also employed for CRISPR/Cpf1 based multiplex genome editing applications in another filamentous fungi [21]. Here, we successfully produced the monocistronic tRNA-processing system and verified its ability to edit pyrG gene in the host TBRC 277 genome. Hence, this report demonstrated the successful in vivo expression and assembly of FnCpf1 and crRNA to form functional FnCpf1-crRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. These complexes serve as RNA-guided nucleases to specifically target and cleave genomic DNA. In addition, these results also suggested that a 20-bp protospacer sequence is sufficient in CRISPR/Cpf1 based system, in contrast to the previous reports using a 23-bp protospacer [29, 36]. Our study therefore supports the previous report that the Cpf1 in complex with the crRNA and double-stranded DNA target was dictated by only the first 20-bp of heteroduplex formation of crRNA and target DNA [49].

We first developed CRISPR/Cpf1 vector specifically for FnCpf1 nuclease, as a proof of concept for gene editing in A. aculeatus species. To our knowledge, the use of FnCpf1 nuclease gene for targeted gene editing has not been reported in any Aspergillus species despite its successful applications in bacteria [50], yeast [40], plant [30], and animal cell lines [29]. In this study, we have shown that the CRISPR/Cpf1 system is able to site-specific edit A. aculeatus chromosome at three different loci within the pyrG gene by constructing specific protospacer guides. However, for genes that are located in a region of low transcriptional activity this would probably reduce the editing efficiency and require optimization [23]. Although it is advisable to carry out off-target mutation analyses by PCR and sequencing, local BLAST analyses of each guide showed no off-targets. Interestingly, indels obtained from all pyrG mutants retain the PAM site since FnCpf1 cleaves target DNA at a distal position, and this report is in accordance with the previous studies in plants [46, 51]. In contrast, Cas9-mediated NHEJ usually destroys the PAM site due to its proximity to the cleavage site thus preventing the possibility for future edits. Since we employed AMA1-based CRISPR/Cpf1 expression vector for transient expression of both FnCpf1 and crRNAs, this would allow us to perform iterative genome editing. This iterative process would allow for targeted gene disruption of multiple targets as well as marker-free genome editing, thus greatly improving the engineering throughput. Some Cpf1 features described above make Cpf1 has several advantageous over Cas9 for gene editing applications even though in some cases both Cpf1 and Cas9 achieved comparable targeting efficiencies [41]. In addition, we envision that gene editing by CRISPR/Cpf1 could be efficiently used as a powerful tool and would enhance the range of possible target sites because of its unique PAM sequence, as well as simplicity in designing crRNA cassettes, when compared to the well-studied CRISPR/Cas9 system.

Conclusions

In summary, we have demonstrated the use of CRISPR/Cpf1 mediated gene editing technology in the wild type strain of A. aculeatus TBRC 277. Using this system, the pyrG gene involved in uridine biosynthesis pathway was successfully edited to generate an auxotrophic strain. The use of FnCpf1 as an alternative class II (type V) nuclease was reported for the first time in A. aculeatus species. The CRISPR/Cpf1 system developed in this study highlights the feasibility of CRISPR/Cpf1 technology and could be envisioned to further increase the utility of the CRISPR/Cpf1 in facilitating strain improvements as well as functional genomics of filamentous fungi.

Materials and methods

Strains, media, and culture conditions

Escherichia coli strain DH5α (Novagen, USA) served as cloning host and for propagating all plasmids. E. coli bearing plasmids were grown in liquid or with 1.5% agar in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium plus ampicillin (100 μg/ml) or kanamycin (50 μg/ml) when required. Recombinant plasmids were purified from E. coli according to QIAquick spin miniprep kit (QIAGEN, Germany). Wild type (WT) strain of A. aculeatus TBRC 277 (= BCC 199), obtained from the Thailand Bioresource Research Center, was used as the host for CRISPR/Cpf1 expression and gene editing experiments. The pyrG gene, encoding orotidine-5′-monophosphate decarboxylase, was retrieved from a complete genome sequence of A. aculeatus TBRC 277. The fungus was grown at 30 °C for 2–4 days on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium for sporulation or potato dextrose broth (PDB) for mycelia propagation. Minimal medium (MM) plus Czapek-Dox (3% sucrose, 0.3% NaNO3, 0.1% KH2PO4, 0.05% MgSO4.7H2O, 0.05% KCl, 0.001% FeSO4.7H2O) containing 1.2 M sorbitol and 50 μg/ml of bleomycin was used as selective medium for protoplast-mediated transformation [52]. MM plus Czapek-Dox medium was supplemented with 10 mM uridine (Uri), 10 mM uracil (Ura), and 1.5 mg/ml 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) (Sigma Aldrich, USA) when required. Plasmids pFC333 and pFC902 [21, 22] were used as templates for constructing CRISPR/Cpf1 and crRNA based plasmids, respectively. Plasmids pJET1.2/Blunt (Thermo Fisher, USA) and pOK12 [53] served as cloning vectors.

Plasmid constructions

All oligonucleotide primers used in this study are shown in Supplementary Table S2. All PCR reactions for cloning purposes were performed for 35 cycles with Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher, USA) using touch-down PCR with annealing temperature starting from 65 °C, with a decrement of 1 °C per cycle for the first 10 cycles followed by a constant annealing temperature at 55 °C up to 35 cycles. Standard reaction volumes were 50 μl including 1x Phusion HF or GC Buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.5 μM primers (IDT, USA), 1 unit of Phusion DNA Polymerase, 10–50 ng of genomic DNA or plasmid as the template. All PCR products were purified using Qiaquick gel extraction and PCR clean-up kits (Qiagen, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instruction. All expression vectors were assembled by standard molecular cloning or Gibson assembly methods [54].

All plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. A detailed schematic map of CRISPR/Cpf1 based expression vector construction is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S1. pFC333 was used to establish CRISPR/Cpf1-based expression vectors [22]. Briefly, to create multiple cloning sites (MCS), a 421-bp of TEF1 terminator from pFC333 was amplified by using a pair of primers pFC333-TT-NcoI-F and pFC333-TT-BamHI-R. The amplified DNA fragment was digested by NcoI/BamHI and ligated to a 11.1-kb of NcoI/BamHI-cut pFC333 plasmid to generate expression vector backbone named pCRISPR0. Additionally, a 1.4-kb BamHI/BglII-cut kanamycin resistance gene cassette, amplified from pJET1.2B-Km by using KanR-Bgl2-F and KanR-R primer pairs, was ligated to BglII-cut pCRISPR0, generating pCRISPR01 vector (Supplementary Table S3). The presence of the intended MCS sequences flanked by Aspergillus nidulans TEF-1 promoter and terminator in the pCRISPR01 was verified by sequencing.

The sequence of F. tularensis subsp. novicida U112 Cpf1 gene, FnCpf1, was obtained from pY001 plasmid [27]. A 3.9-kb of FnCpf1 gene (Supplementary Table S3) with its C-terminal fused to SV40 NLS was optimized for translation on the basis of codon frequency in A. aculeatus (http://www.kazusa.or.jp/codon/cgi-bin/showcodon.cgi?species=5053&aa=1& style=N) and synthesized (GenScript, USA) to obtain pUC57-FnCpf1 plasmid. Then, the FnCpf1-SV40 fusion gene was PCR-amplified from the plasmid using a pair of primers FnCpf1-NcoI-F and FnCpf1-PmeI-R, followed by NcoI/PmeI digestion and ligation to pCRISPR01 to obtain a plasmid named pCRISPR01-FnCpf1 (Table 1, Fig. 2a).

To detect the expression and localization of Cpf1, enhanced GFP (eGFP) gene was fused in-frame to Cpf1 at the C-terminal together with SV40 NLS at the 3′ end of the fused sequence to generate plasmid pCRISPR01-FnCpf1-eGFP (Supplementary Table S3, Fig. 2a). This was carried out by amplification of pUC57-FnCpf1 and pUC57-EGFP with a pair of primers FnCpf1-NcoI-F/FnCpf1-Kpn-R and EGFP-NK-F/ EGFP-SV40-Pme-R, respectively, followed by restriction enzyme digestion (NcoI/KpnI for FnCpf1 and KpnI/PmeI for eGFP) and ligation. In addition to Cpf1 and Cpf1-EGFP fusion constructs, the expression vector bearing only eGFP gene was also employed as a control by amplification of eGFP in pUC57-EGFP using the same primers used for eGFP fusion construction, but the amplified PCR product was digested by NcoI/PmeI prior to ligation with plasmid pCRISPR01.

Protoplast-mediated transformation

All CRISPR/Cpf1 vectors were transformed into the recipient A. aculeatus TBRC 277 using the protoplast-mediated transformation method [55, 56]. Briefly, spore suspension (105 spores/ml) was inoculated into 50-ml of PDB and incubated at 30 °C with shaking at 250 rpm for 10–12 h. Mycelia were collected by filtration and washed with sterilized distilled water, then suspended in 5-ml protoplast buffer (1.2 M sorbitol, 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 5.6) together with enzyme mixtures (2 mg/ml β-glucoronidase, 10 mg/ml driselase, 20 mg/ml lysing enzyme/Glucanex). The mixture was incubated at 30 °C with gentle shaking at 100 rpm for 4–5 h. Protoplasts were separated from undigested mycelia by using Falcon Cell Strainer with 40 μm porosity (Thermo Fisher, USA), then gently rinsed with Wash Buffer (1.2 M sorbitol, 10 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5) followed by centrifugation at 3000 x g for 5 min. The protoplast pellets were resuspended in STC buffer (1.2 M sorbitol, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM CaCl2) to achieve a concentration of 107–108 protoplasts/ml.

Protoplast-mediated transformation (PMT) was carried out as described previously [9]. Specifically, 10-μg of purified DNA in 20 μl (500 ng/μl) was mixed with 100 μl of protoplast suspension (107-108 protoplast/ml) and incubated on ice for 50 min. Subsequently, 1.25 ml of PCT buffer (25% PEG 6000, 50 mM CaCl2, 10 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5) was added to the mixture followed by incubation at room temperature for additional 20 min. Next, 1.25 ml of STC buffer was added, followed by addition of 5 ml PDB in 1.2 M sorbitol. The solution was centrifuged at 3000 x g for 10 min and the supernatant was discarded. Next, 2 ml of STC buffer was added to the cell pellet, and gently mixed with 30 ml of preheat MM+Czapek-Dox soft agar medium at 45 °C. Approximately 5-ml of mixture was overlayed on the high osmotic pressure MM+Czapek-Dox plates with 1.2 M sorbitol containing 50 μg/ml bleomycin (InvivoGen, USA) and Uri/Ura, followed by incubation at 30 °C for 3-5 days. Fungal transformants were selected and purified to obtain single colonies onto new MM+Czapek-Dox containing 50 μg/ml bleomycin and Uri/Ura. For pyrG mutant selections, fungal transformants were selected on MM+Czapek-Dox plates containing 5-FOA and Uri/Ura.

Fluorescence microscopy imaging and analysis

For recombinant fungi bearing pCRISPR01-FnCpf1-eGFP, bleomycin-resistant colonies were selected and purified to obtain single colonies followed by fluorescent microscopic assessment [57, 58]. Specifically, conidia were inoculated into 750 μl PDB medium containing 25 μg/ml antibiotics bleomycin and grown statically for 12–14 h at 30 °C. Before imaging, hyphae were washed with 1x PBS pH 7.4 and incubated with 50 μg/ml 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma Aldrich, USA) for 30 min. The image was captured by Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (LSM) 800 with Airyscan 2 (Carl Zeiss, Germany) with a 63x oil immersion objective lens. Image handling and quality optimization were performed using ZEN 2.1 imaging software (Carl Zeiss, Germany).

Western blotting

Expression of FnCpf1 in A. aculeatus TBRC 277 was also detected by western blot as described [16, 59]. Specifically, total proteins from recombinant A. aculeatus mycelia was extracted by first inoculating 105 conidia in 50-ml PDB medium with bleomycin (100 μg/ml) and incubated for 24 h at 30 °C with 250 rpm on a rotary shaker. Then, the mycelia were collected by filtration with Whatman Grade 41 filter paper (Sigma Aldrich, USA) followed by gently blotting with tissue paper to remove the remaining liquid media. The mycelia were ground into fine powders under liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle. Subsequently, approximately 200 mg of mycelia powders was added into an eppendorf tube containing 500 μl ice-cold extraction buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 137 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol 99.5%) with freshly added cOmplete mini protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), followed by gently mixing for 5 min. The slurry was incubated on ice for additional 10 min, and the supernatant which contains a total protein was collected in a new tube after centrifugation at 14,000 x g for 15 min at 4 °C. The protein quantity was determined by Bradford method [60] using protein assay dye reagent (Bio-Rad, USA).

Approximately 20 μg of crude protein extracts was loaded in each lane for a 10% SDS-PAGE [16, 59]. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to a 5.5 × 8.5 cm nitrocellulose membrane with 0.2 μm pore size (Bio-Rad, USA) by using a Mini Trans-Blot Immersion (Bio-Rad) in 38.90 mM glycine, 47.88 mM Tris base, 0.0375% (w/v) SDS and 20% methanol at 90 V for 70 min. Then the membrane was soaked in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) for 5 min, then incubated in blocking buffer (PBS with 0.5% Tween 20 (PBST), 4% (w/v) non-fat dry milk) for 2 h at room temperature on shaking incubator with gentle agitation. Subsequently, the membrane was probed with anti-GFP mouse monoclonal antibody (Thermo Fisher, USA) or FnCpf1 mouse monoclonal antibody (Genscript, USA) in PBST buffer at 1:1000 dilution for 1 h. The membrane was washed with PBST buffer twice for 5 min each, then added with a 1:1000 dilution of anti-mouse IgG conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (Thermo Fisher, USA) in PBST buffer. The membrane was then washed twice with PBST buffer for 5 min each and developed using a 1-Step NBT/BCIP chromogenic substrate (Thermo Fisher, USA) by incubating the membrane for 5–15 min or until the desired color developed.

Development of a single crRNA targeting pyrG gene in A. aculeatus TBRC 277

pyrG coding sequence validation

A. aculeatus TBRC 277 genomic DNA was extracted using Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, USA). The pyrG gene from A. aculeatus TBRC 277 genomic DNA was PCR-amplified using pyrG-F and pyrG-R primers (Supplementary Table S2). The amplified fragment was purified and cloned into pJET1.2/B vector (Thermo Fisher, USA). Positive clones carrying DNA inserts were sequenced from both strands. Nucleotide sequence of pyrG obtained were pairwise-aligned to the sequence previously obtained by next-generation sequencing (NGS). The consensus sequence was submitted to GenBank under accession number MN364695 and used as template in selecting protospacer guide sequence (Table 2).

Table 2.

Protospacer sequences selected for the gene editing of A. aculeatus TBRC 277

| Spacer ID | Gene target | Genomic target sequence (5′> 3′) | PAM | Promoter | Location (ATG Start) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pyrG-1 | pyrG | GCCAGCGGGTTGGTGTGCTT | TTTN | U3-AF | 43–62 |

| pyrG-2 | pyrG | GGCGGGGCCCTACGGTCAGC | TTTN | U3-AF | 151–170 |

| pyrG-3 | pyrG | TCATGGGGTTCGTGTCGACG | TTTN | U3-AF | 632–650 |

Construction of pre-crRNA for pyrG gene editing in A. aculeatus TBRC 277

The protospacer guide sequences were designed based on the criteria used in S. cerevisiae [40]. Specifically, crRNA sequence targeting pyrG was first determined by searching for potential PAM sites (5′-TTTV-) together with a 20–23 bp protospacer sequence directly at the 3′-end of the PAM motifs using Geneious Prime ver. 2019.2.1 software [20, 61]. To ensure no off-targets, the obtained protospacer sequences were BLAST against A. aculeatus TBRC 277 genome sequence. The guide sequences of pyrG used in this study are shown in Table 2.

The U3-Af Pol III promoter and U3-Af terminator derived from Aspergillus fumigatus for crRNA expression was PCR amplified from pFC902 [22] by using AF U3 Prom-F and U3-TT R primers (Supplementary Table S1). The amplified PCR product was cloned into pJET1.2/Blunt vector to generate pJET1.2-U3P sgRNA plasmid, and verified by sequencing. This plasmid was then used as DNA template for the synthesis of three crRNA cassettes carrying specific Cpf1-associated protospacers (pyrG-1, pyrG-2 and pyrG-3) flanked by tRNA-Gly motif (the crRNA-tRNA-pyrG cassettes). These cassettes were individually constructed using PCR reactions with primers (Supplementary Table S1) to remove Cas9-associated sgRNA. The cassettes were used to generate Cpf1-associated crRNA cassettes which were divided into two DNA fragments each containing the appropriate homologous sequence overlaps. The corresponding purified PCR fragments were assembled into the linear BglII-cut pOK12 plasmid using Gibson assembly method [54]. Then each crRNA cassette was individually subcloned into BglII-cut pCRISPR01-FnCpf1 to generate the plasmids pCRISPR01-FnCpf1-pyrG-1, pCRISPR01-FnCpf1-pyrG-2 and pCRISPR01-FnCpf1-pyrG-3, each carrying the specific protospacer pyrG-1, pyrG-2 and pyrG-3, respectively.

Verification of recombinant TBRC 277 and analysis of indels

Fungal genomic DNA of randomly selected mutants was purified by Phire plant direct PCR kit (Thermo Fisher, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. For detection of the recombinant plasmids in TBRC 277, two pairs of primers (seq TEF-F/seq TEF-R or seq CRISPR sgRNA F-1/seq CRISPR sgRNA R-1) were employed to verify Cpf1 gene inserts or crRNA cassettes. For detection of the genotype of uridine auxotrophic mutants, a pair of 5′-169 bp up F3/3′-148 bp down R2 primers was used to amplify pyrG gene, followed by DNA sequencing to determine the presence of mutations (indels) within the targeted pyrG loci. The CRISPR efficiency was calculated by dividing the number of mutant colonies detected by sequencing and the total number of putative mutants selected for analysis [20].

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Schematic representation of pCRISPR01 plasmid construction backbone for CRISPR/Cpf1 genome editing experiment in A. aculeatus TBRC 277.

Additional file 2: Fig. S2. Western blot detection of heterologous EGFP and Cpf1-EGFP proteins in recombinant A. aculeatus TBRC 277 egfp and Cpf1-egfp, respectively. (a) GenCRISPRTM FnCpf1 monoclonal antibody (9H6) was used as the primary detection, 1.0 μg (Genscript, USA). (b) GFP monoclonal antibody (C163) was used for the primary detection, 3 μg (Thermo Fisher, USA). All samples were treated by IgG-AP as the secondary antibody for detection, 2 μg. Lane 1, crude protein of A. aculeatus recombinant (Cpf1-egfp). Lane 2, crude protein of recombinant A. aculeatus (egfp), Lane 3, crude protein of A. aculeatus TBRC 277 wild-type (control). Each lane was loaded with 20-μg protein. Anti-GFP (Roche) and FnCpf1 (Genscript, USA) antibodies were used as the primary (monoclonal) antibodies, anti IgG-conjugated AP was used for secondary antibody. M: PageRule Plus Prestained Protein Ladder (Thermo Fisher, USA).

Additional file 3: Fig. S3. The functional plasmid construction of CRISPR/Cpf1 system. The plasmid consists of Cpf1 nuclease gene and crRNA-pyrG cassettes for targeted genome modification in A. aculeatus TBRC 277. (a) pCRISPR/Cpf1-pyrG plasmid, crRNA is expressed under control of U3-AF pol. III promoter, (b) Guide RNA cassette, crRNA, consists of 19-bp direct repeats (DR) to form a stem-loop structure, as well as 20-bp pyrG-targeted protospacers.

Additional file 4: Fig. S4. Transformation efficiency of A. aculeatus TBRC 277 in the presence or absence of Cpf1 endonuclease containing plasmids. To investigate the toxicity of Cpf1 on the A. aculeatus host, 10-μg DNA of each plasmids were independently transformed into TBRC 277 protoplast. The number of transformants were recovered from minimal medium (MM+Czapek-Dox+bleomycin+sorbitol) supplemented with Uri/Ura. Protoplast transformed with empty vector, pCRISPR01, has no FnCpf1 gene (dark grey); protoplast transformed with FnCpf1-containing plasmid, pCRISPR01-FnCpf1 (light-grey); protoplast transformed with FnCpf1 and crRNA-pyrGs, pCRISPR01-FnCpf1-pyrGs (pyrG-1, pyrG-2, or pyrG-3) (white). The graph shows the means and standard deviation (SD) from two independent experiments.

Additional file 5: Table S1. CRISPR/Cpf1 gene editing efficiency targeting pyrGof A. aculeatus TBRC 277.

Additional file 6: Table S2. List of primers used in this study.

Additional file 7: Table S3. The sequence of FnCpf1, eGFP, and pCRISPR01 expression vector.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Aiyada Aroonsri and Poochit Nonejuie for technical assistance and helpful scientific discussion. We also thank Dr. Albert Ketterman for his careful and critical reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- 5-FOA

5-fluoroorotic acid

- Cas

CRISPR-associated proteins

- CRISPR

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

- crRNA

CRISPR RNA or guide RNA or gRNA

- eGFP

Enhanced green fluorescent protein

- MM

Minimal medium

- NHEJ

Non-homologous end-joining

- NLS

Nuclear localization signal

- PAM

Protospacer adjacent motif

Authors’ contributions

DA performed the experimental works, investigated and interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript. KP and DC supervised, provided technical support, and edited the manuscript. KP, DC, LE, and VC were responsible for the primary conception of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology (NSTDA), National Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (BIOTEC), Thailand, under the grants P-18-51580 and P-18-52106, the ASEAN Royal Golden Jubilee Scholarship (RGJ-ASEAN), the Mahidol University Postgraduate scholarship, and the Thailand Graduate Institute of Science and Technology (TGIST), NSTDA.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. The open reading frame of pyrG gene sequence was submitted to NCBI sequence database under the accession number MN364695. Plasmids are available upon reasonable request as well as on the TBRC website: https://www.tbrcnetwork.org.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Duriya Chantasingh, Email: duriya@biotec.or.th.

Kusol Pootanakit, Email: kusol.poo@mahidol.ac.th.

References

- 1.Suwannarangsee S, Arnthong J, Eurwilaichitr L, Champreda V. Production and characterization of multi-polysaccharide degrading enzymes from Aspergillus aculeatus BCC199 for saccharification of agricultural residues. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;24(10):1427–1437. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1406.06050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward OP. Production of recombinant proteins by filamentous fungi. Biotechnol Adv. 2012;30(5):1119–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nielsen JC, Grijseels S, Prigent S, Ji B, Dainat J, Nielsen KF, et al. Global analysis of biosynthetic gene clusters reveals vast potential of secondary metabolite production in Penicillium species. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:17044. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Vries RP, Riley R, Wiebenga A, Aguilar-Osorio G, Amillis S, Uchima CA, et al. Comparative genomics reveals high biological diversity and specific adaptations in the industrially and medically important fungal genus Aspergillus. Genome Biol. 2017;18(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1151-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y, Hu X, Sang J, Zhang Y, Zhang H, Lu F, et al. An acid-stable beta-glucosidase from Aspergillus aculeatus: gene expression, biochemical characterization and molecular dynamics simulation. Int J biol Macromol. 2018;119:462–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.07.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein-Marcuschamer D, Oleskowicz-Popiel P, Simmons BA, Blanch HW. The challenge of enzyme cost in the production of lignocellulosic biofuels. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109(4):1083–1087. doi: 10.1002/bit.24370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarkari P, Marx H, Blumhoff ML, Mattanovich D, Sauer M, Steiger MG. An efficient tool for metabolic pathway construction and gene integration for Aspergillus niger. Bioresour Technol. 2017;245(Pt B):1327–1333. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer V. Genetic engineering of filamentous fungi — Progress, obstacles and future trends. Biotechnol Advances. 2008;26(2):177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leynaud-Kieffer LMC, Curran SC, Kim I, Magnuson JK, Gladden JM, Baker SE, et al. A new approach to Cas9-based genome editing in Aspergillus niger that is precise, efficient and selectable. PloS one. 2019;14(1):e0210243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kjærbølling I, Vesth TC, Frisvad JC, Nybo JL, Theobald S, Kuo A, et al. Linking secondary metabolites to gene clusters through genome sequencing of six diverse Aspergillus species. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(4):E753-EE61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715954115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Besser J, Carleton HA, Gerner-Smidt P, Lindsey RL, Trees E. Next-generation sequencing technologies and their application to the study and control of bacterial infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(4):335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi TQ, Liu GN, Ji RY, Shi K, Song P, Ren LJ, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing of the filamentous fungi: the state of the art. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101(20):7435–7443. doi: 10.1007/s00253-017-8497-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu PD, Lander ES, Zhang F. Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell. 2014;157(6):1262–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339(6121):819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337(6096):816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuller KK, Chen S, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC. Development of the CRISPR/Cas9 system for targeted gene disruption in Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryotic cell. 2015;14(11):1073–1080. doi: 10.1128/EC.00107-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katayama T, Tanaka Y, Okabe T, Nakamura H, Fujii W, Kitamoto K, et al. Development of a genome editing technique using the CRISPR/Cas9 system in the industrial filamentous fungus Aspergillus oryzae. Biotechnol Lett. 2016;38(4):637–642. doi: 10.1007/s10529-015-2015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong H, Zheng J, Yu D, Wang B, Pan L. Efficient genome editing in Aspergillus niger with an improved recyclable CRISPR-HDR toolbox and its application in introducing multiple copies of heterologous genes. J Microbiol Methods. 2019;163:105655. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2019.105655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuivanen J, Wang YMJ, Richard P. Engineering Aspergillus niger for galactaric acid production: elimination of galactaric acid catabolism by using RNA sequencing and CRISPR/Cas9. Microbial Cell Factories. 2016;15(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s12934-016-0613-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song L, Ouedraogo J-P, Kolbusz M, Nguyen TTM, Tsang A. Efficient genome editing using tRNA promoter-driven CRISPR/Cas9 gRNA in Aspergillus niger. PloS one. 2018;13(8):e0202868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nodvig CS, Hoof JB, Kogle ME, Jarczynska ZD, Lehmbeck J, Klitgaard DK, et al. Efficient oligo nucleotide mediated CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing in Aspergilli. Fungal genet biol. 2018;115:78–89. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nodvig CS, Nielsen JB, Kogle ME, Mortensen UH. A CRISPR-Cas9 system for genetic engineering of filamentous Fungi. PLoS one. 2015;10(7):e0133085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu R, Chen L, Jiang Y, Zhou Z, Zou G. Efficient genome editing in filamentous fungus Trichoderma reesei using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Cell Discov. 2015;1:15007. doi: 10.1038/celldisc.2015.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsu-Ura T, Baek M, Kwon J, Hong C. Efficient gene editing in Neurospora crassa with CRISPR technology. Fungal Biol Biotechnol. 2015;2:4. doi: 10.1186/s40694-015-0015-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qin H, Xiao H, Zou G, Zhou Z, Zhong J-J. CRISPR-Cas9 assisted gene disruption in the higher fungus Ganoderma species. Process Biochem. 2017;56:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2017.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Q, Gao R, Li J, Lin L, Zhao J, Sun W, et al. Development of a genome-editing CRISPR/Cas9 system in thermophilic fungal Myceliophthora species and its application to hyper-cellulase production strain engineering. Biotechnol biofuels. 2017;10(1). 10.1186/s13068-016-0693-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Zetsche B, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Slaymaker IM, Makarova KS, Essletzbichler P, et al. Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell. 2015;163(3):759–771. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koonin EV, Makarova KS, Zhang F. Diversity, classification and evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2017;37:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zetsche B, Heidenreich M, Mohanraju P, Fedorova I, Kneppers J, DeGennaro EM, et al. Multiplex gene editing by CRISPR-Cpf1 using a single crRNA array. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35(1):31–34. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang M, Mao Y, Lu Y, Tao X, Zhu JK. Multiplex gene editing in Rice using the CRISPR-Cpf1 system. Mol Plant. 2017;10(7):1011–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fonfara I, Richter H, Bratovic M, Le Rhun A, Charpentier E. The CRISPR-associated DNA-cleaving enzyme Cpf1 also processes precursor CRISPR RNA. Nature. 2016;532(7600):517–521. doi: 10.1038/nature17945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deng H, Gao R, Liao X, Cai Y. CRISPR system in filamentous fungi: current achievements and future directions. Gene. 2017;627:212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White RJ. Transcription by RNA polymerase III: more complex than we thought. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(7):459–463. doi: 10.1038/nrg3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao Y, Zhao Y. Self-processing of ribozyme-flanked RNAs into guide RNAs in vitro and in vivo for CRISPR-mediated genome editing. J Integr plant biol. 2014;56(4):343–349. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xie K, Minkenberg B, Yang Y. Boosting CRISPR/Cas9 multiplex editing capability with the endogenous tRNA-processing system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015;112(11):3570–3575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420294112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vanegas KG, Jarczynska ZD, Strucko T, Mortensen UH. Cpf1 enables fast and efficient genome editing in Aspergilli. Fungal biol Biotechnol. 2019;6:6. doi: 10.1186/s40694-019-0069-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiménez A, Hoff B, Revuelta JL. Multiplex genome editing in Ashbya gossypii using CRISPR-Cpf1. New biotechnology. 2020;57:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2020.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Q, Zhang Y, Li F, Li J, Sun W, Tian C. Upgrading of efficient and scalable CRISPR-Cas-mediated technology for genetic engineering in thermophilic fungus Myceliophthora thermophila. Biotechnology for biofuels. 2019;12:293. doi: 10.1186/s13068-019-1637-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li ZH, Liu M, Lyu XM, Wang FQ, Wei DZ. CRISPR/Cpf1 facilitated large fragment deletion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J basic Microbiol. 2018;58(12):1100–1104. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201800195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swiat MA, Dashko S, den Ridder M, Wijsman M, van der Oost J, Daran JM, et al. FnCpf1: a novel and efficient genome editing tool for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic acids res. 2017;45(21):12585–12598. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verwaal R, Buiting-Wiessenhaan N, Dalhuijsen S, Roubos JA. CRISPR/Cpf1 enables fast and simple genome editing of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2018;35(2):201–211. doi: 10.1002/yea.3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boeke JD, LaCroute F, Fink GR. A positive selection for mutants lacking orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase activity in yeast: 5-fluoro-orotic acid resistance. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;197(2):345–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00330984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ling SO, Storms R, Zheng Y, Rodzi MR, Mahadi NM, Illias RM, et al. Development of a pyrG mutant of Aspergillus oryzae strain S1 as a host for the production of heterologous proteins. Scientific World J. 2013;2013:634317. doi: 10.1155/2013/634317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.d'Enfert C. Selection of multiple disruption events in Aspergillus fumigatus using the orotidine-5′-decarboxylase gene, pyrG, as a unique transformation marker. Curr Genet. 1996;30(1):76–82. doi: 10.1007/s002940050103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weidner G, d'Enfert C, Koch A, Mol PC, Brakhage AA. Development of a homologous transformation system for the human pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus based on the pyrG gene encoding orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase. Curr Genet. 1998;33(5):378–385. doi: 10.1007/s002940050350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim H, Kim ST, Ryu J, Kang BC, Kim JS, Kim SG. CRISPR/Cpf1-mediated DNA-free plant genome editing. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14406. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swarts DC, Jinek M. Cas9 versus Cas12a/Cpf1: structure-function comparisons and implications for genome editing. Wiley Interdiscip rev RNA. 2018:e1481. 10.1002/wrna.1481. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Jöchl C, Rederstorff M, Hertel J, Stadler PF, Hofacker IL, Schrettl M, et al. Small ncRNA transcriptome analysis from Aspergillus fumigatus suggests a novel mechanism for regulation of protein synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(8):2677–2689. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Swarts DC, van der Oost J, Jinek M. Structural basis for guide RNA processing and seed-dependent DNA targeting by CRISPR-Cas12a. Mol Cell. 2017;66(2):221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang Y, Qian F, Yang J, Liu Y, Dong F, Xu C, et al. CRISPR-Cpf1 assisted genome editing of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15179. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ding D, Chen K, Chen Y, Li H, Xie K. Engineering introns to express RNA guides for Cas9- and Cpf1-mediated multiplex genome editing. Mol Plant. 2018;11(4):542–552. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arentshorst M, Ram AFJ, Meyer V. Using non-homologous end-joining-deficient strains for functional gene analyses in filamentous Fungi. In: Bolton MD, Thomma BPHJ, editors. Plant fungal pathogens: methods and protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2012. pp. 133–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vieira J, Messing J. New pUC-derived cloning vectors with different selectable markers and DNA replication origins. Gene. 100:1991, 189–4. 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90365-I. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, 3rd, Smith HO. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat methods. 2009;6(5):343–345. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnstone IL, Hughes SG, Clutterbuck AJ. Cloning an Aspergillus nidulans developmental gene by transformation. EMBO J. 1985;4(5):1307–1311. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03777.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Penttilä M, Nevalainen H, Rättö M, Salminen E, Knowles J. A versatile transformation system for the cellulolytic filamentous fungus Trichoderma reesei. Gene. 1987;61(2):155–164. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Berger H, Pachlinger R, Morozov I, Goller S, Narendja F, Caddick M, et al. The GATA factor AreA regulates localization and in vivo binding site occupancy of the nitrate activator NirA. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59(2):433–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vaknin Y, Hillmann F, Iannitti R, Ben Baruch N, Sandovsky-Losica H, Shadkchan Y, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel Aspergillus fumigatus rhomboid family putative protease, RbdA, involved in hypoxia sensing and virulence. Infect Immun. 2016;84(6):1866–1878. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00011-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang C, Meng X, Wei X, Lu L. Highly efficient CRISPR mutagenesis by microhomology-mediated end joining in Aspergillus fumigatus. Fungal Genet Biol. 2016;86:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Analytical biochem. 1976;72(1):248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, et al. Geneious basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(12):1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Schematic representation of pCRISPR01 plasmid construction backbone for CRISPR/Cpf1 genome editing experiment in A. aculeatus TBRC 277.

Additional file 2: Fig. S2. Western blot detection of heterologous EGFP and Cpf1-EGFP proteins in recombinant A. aculeatus TBRC 277 egfp and Cpf1-egfp, respectively. (a) GenCRISPRTM FnCpf1 monoclonal antibody (9H6) was used as the primary detection, 1.0 μg (Genscript, USA). (b) GFP monoclonal antibody (C163) was used for the primary detection, 3 μg (Thermo Fisher, USA). All samples were treated by IgG-AP as the secondary antibody for detection, 2 μg. Lane 1, crude protein of A. aculeatus recombinant (Cpf1-egfp). Lane 2, crude protein of recombinant A. aculeatus (egfp), Lane 3, crude protein of A. aculeatus TBRC 277 wild-type (control). Each lane was loaded with 20-μg protein. Anti-GFP (Roche) and FnCpf1 (Genscript, USA) antibodies were used as the primary (monoclonal) antibodies, anti IgG-conjugated AP was used for secondary antibody. M: PageRule Plus Prestained Protein Ladder (Thermo Fisher, USA).

Additional file 3: Fig. S3. The functional plasmid construction of CRISPR/Cpf1 system. The plasmid consists of Cpf1 nuclease gene and crRNA-pyrG cassettes for targeted genome modification in A. aculeatus TBRC 277. (a) pCRISPR/Cpf1-pyrG plasmid, crRNA is expressed under control of U3-AF pol. III promoter, (b) Guide RNA cassette, crRNA, consists of 19-bp direct repeats (DR) to form a stem-loop structure, as well as 20-bp pyrG-targeted protospacers.

Additional file 4: Fig. S4. Transformation efficiency of A. aculeatus TBRC 277 in the presence or absence of Cpf1 endonuclease containing plasmids. To investigate the toxicity of Cpf1 on the A. aculeatus host, 10-μg DNA of each plasmids were independently transformed into TBRC 277 protoplast. The number of transformants were recovered from minimal medium (MM+Czapek-Dox+bleomycin+sorbitol) supplemented with Uri/Ura. Protoplast transformed with empty vector, pCRISPR01, has no FnCpf1 gene (dark grey); protoplast transformed with FnCpf1-containing plasmid, pCRISPR01-FnCpf1 (light-grey); protoplast transformed with FnCpf1 and crRNA-pyrGs, pCRISPR01-FnCpf1-pyrGs (pyrG-1, pyrG-2, or pyrG-3) (white). The graph shows the means and standard deviation (SD) from two independent experiments.

Additional file 5: Table S1. CRISPR/Cpf1 gene editing efficiency targeting pyrGof A. aculeatus TBRC 277.

Additional file 6: Table S2. List of primers used in this study.

Additional file 7: Table S3. The sequence of FnCpf1, eGFP, and pCRISPR01 expression vector.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. The open reading frame of pyrG gene sequence was submitted to NCBI sequence database under the accession number MN364695. Plasmids are available upon reasonable request as well as on the TBRC website: https://www.tbrcnetwork.org.