Abstract

Background.

The systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), calculated using absolute platelet, neutrophil, and lymphocyte counts, has recently emerged as a predictor of survival for patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) when assessed at diagnosis. Neoadjuvant therapy (NAT) is increasingly used in the treatment of PDAC. However, biomarkers of response are lacking. This study aimed to determine the prognostic significance of SII before and after NAT and its association with the pancreatic tumor biomarker carbohydrate-antigen 19–9 (CA 19–9).

Methods.

This study retrospectively analyzed all PDAC patients treated with NAT before pancreatic resection at a single institution between 2007 and 2017. Pre- and post-NAT lab values were collected to calculate SII. Absolute pre-NAT, post-NAT, and change in SII after NAT were evaluated for their association with clinical outcomes.

Results.

The study analyzed 419 patients and found no significant correlation between pre-NAT SII and clinical outcomes. Elevated post-NAT SII was an independent, negative predictor of overall survival (OS) when assessed as a continuous variable (hazard ratio [HR], 1.0001; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.00003–1.00014; p = 0.006). Patients with a post-NAT SII greater than 900 had a shorter median OS (31.9 vs 26.1 months; p = 0.050), and a post-NAT SII greater than 900 also was an independent negative predictor of OS (HR, 1.369; 95% CI 1.019–1.838; p = 0.037). An 80% reduction in SII independently predicted a CA 19–9 response after NAT (HR, 4.22; 95% CI 1.209–14.750; p = 0.024).

Conclusion.

Post-treatment SII may be a useful prognostic marker in PDAC patients receiving NAT.

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a devastating disease and the third leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States.1,2 By 2030, PDAC-related mortality is projected to be the second leading cause of death, and innovations in prevention, screening, and treatment are required to improve patient outcomes.3 Surgical resection of the tumor with a negative margin (R0) is a critical factor determining long-term survival.4 Due to the aggressive nature of the disease and anatomic relationships of the tumor with major vasculature, more than one third of patients present with borderline resectable or locally advanced disease.5,6 Increasing evidence suggests that these patients may benefit from receiving neoadjuvant therapy (NAT).5–9

Given the emerging role of neoadjuvant treatment in patients with pancreatic cancer, biomarkers of response to treatment are needed. Unfortunately, cross-sectional imaging is not a precise indicator of treatment response or resectability after NAT.6,10–14 Serum carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA 19–9) is the most commonly used pancreatic cancer biomarker in PDAC patients treated with NAT.15,16 However, its prognostic potential is limited given its restricted sensitivity and specificity.17,18 Additionally, approximately 5–20% of all PDAC patients found to be Lewis histo-blood-type-negative are CA 19–9 non-secretors, supporting the need for novel biomarkers.17–20

Inflammatory mediators have demonstrated a substantial role in the PDAC tumor microenvironment, enhancing proliferation and growth of malignant cells, supporting an immunoregulatory adaptive immune response, and reducing efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents.21,22 First described in hepatocellular carcinoma, the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), calculated with lymphocyte, neutrophil, and platelet counts from a complete blood count and differential, is a readily available test that serves as an independent predictor of poor disease-free survival for patients with resectable PDAC.23–25

The influence of NAT on SII and its prognostic potential have not been explored to date. This study retrospectively analyzed the prognostic ability of SII before and after NAT for patients with pancreatic cancer and compared its association with clinical outcomes and CA 19–9.

METHODS

Patient Selection

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pittsburgh (PRO17080318). We retrospectively evaluated all patients receiving NAT for PDAC between April 2007 and June 2017 at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC, Pittsburgh, PA). Patients were included if they had undergone surgical resection with curative intent and had pathologic confirmation of PDAC. Patients who died within 90 days after surgery due to postoperative complications also were excluded.

Data Collection and Analysis

Demographics, treatment characteristics, and clinical variables including laboratory values, tumor stage, T-size, and CA 19–9 levels were retrospectively retrieved from the electronic medical record. Pre- and post-NAT (preoperative) laboratory values within 14 days before NAT and before surgery were analyzed. The clinical outcomes evaluated included R0 resection rate, CA 19–9 biomarker response, histopathologic response, and overall and disease-free survival rates. From the laboratory values, the absolute platelet (P), neutrophil (N), and lymphocyte (L) counts were used to calculate the SII (SII = P × [N/L]).23 Patients with normal pre-NAT CA 19-9 values (< 37) were excluded for further CA 19-9 response analysis, defined as a decrease greater than 50% after NAT.15

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data are reported as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range [IQR]). Categorical variables are reported as frequency (n) and percentage (%). For continuous variables, comparisons were made using Student’s t test when they were normally distributed, and using Wilcoxon rank-sum test when distributed otherwise. For categorical variables, comparisons were made using Chi square or Fisher’s exact test. Uni- and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify factors predictive of survival and neoadjuvant chemotherapy response. Kaplan–Meier was used to estimate median disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS). Survival was determined to be the time between operative resection and disease recurrence, death, or last follow-up evaluation. Follow-up evaluation was terminated January 1, 2019.

The critical cutoff value of SII was determined with the Harrell’s D and Somers’ D statistical tests. Statistical significance for survival was determined using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards models were used to identify predictors of survival after adjustment for disease stage, margin, administration of adjuvant chemotherapy, and other covariates. The backward stepwise elimination method was used in building all multivariate models. All tests used in the analysis were two-sided, with an alpha of 0.05 indicating statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed with Stata 13.1 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Demographic and Clinicopathologic Characteristics

As shown in Table 1, 419 patients (210 women, 50%) with a median age of 65.17 years were identified for analysis. A majority of the patients (77%, n = 324) underwent a pancreaticoduodenectomy for resection. A variety of a neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimens were used, including gemcitabine-based regimens (67.9%, n = 283), fluorouracil (5FU)-based regimens (24.2%, n = 101), or both gemcitabine- and 5FU-based regimens (7.4%, n = 31) in case of crossover, with 10% of all the patients (n = 41) also receiving stereotactic body radiation therapy.

TABLE 1.

Patient demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics

| Variable | Total cohort (n = 419) n (%) | Post-treatment SII ≤ 900 (n = 286) n (%) | Post-treatment SII > 900 (n = 133) n (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 65.17 ± 9.7 | 64.57 ± 9.7 | 66.44 ± 9.58 | 0.066 |

| Sex (F) | 210 (50.2) | 139 (48.6) | 71 (53.4) | 0.362 |

| Mean BMI | 26.91 ± 5.42 | 27.48 ± 5.33 | 25.69 ± 5.43 | 0.002 |

| Mean age-adjusted CCI | 4.69 ± 1.55 | 4.62 ± 1.54 | 4.86 ± 1.55 | 0.137 |

| Mean preop albumin (g/dL) | 3.59 ± 0.48 | 3.63 ± 0.48 | 3.50 ± 0.47 | 0.013 |

| Mean T size (cm) | 2.98 ± 0.89 | 2.99 ± 0.88 | 2.96 ± 0.91 | 0.708 |

| Median pre-NAT SII (IQR) | 563 (367–988) | 500 (341–825) | 809 (466–1359) | < 0.0001 |

| Median post-NAT SII (IQR) | 582 (275–1140) | 361 (211–589) | 1770 (1164–2640) | < 0.0001 |

| Median SII % change (IQR) | − 0.11 (− 0.53 to 0.80) | − 0.35 (− 0.66 to 0.1) | 1.24 (0.13 to 3.14) | < 0.0001 |

| Node+ | 198 (49.8) | 134 (49.6) | 64 (50) | 0.945 |

| Margin (negative) | 342 (81.6) | 230 (80.4) | 112 (84.2) | 0.351 |

| LVI | 282 (67.5) | 188 (66.0) | 94 (70.7) | 0.338 |

| PNI | 330 (78.8) | 225 (78.7) | 105 (79) | 0.949 |

| LN (positive) | 265 (63.3) | 183 (64) | 82 (61.7) | 0.645 |

| Grade | 0.886 | |||

| 0 | 8 (2) | 5 (1.8) | 3 (2.3) | |

| 1 | 11 (2.7) | 7 (2.5) | 4 (2.7) | |

| 2 | 292 (71.4) | 197 (71.1) | 95 (71.4) | |

| 3 | 95 (23.2) | 65 (23.5) | 30 (22.7) | |

| 4 | 3 (0.7) | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Median pre-NAT CA 19–9 (IQR) | 337 (111–1075) | 360 (113–1276) | 272 (98–852) | 0.284 |

| Median post-NAT CA 19–9 (IQR) | 57.1 (29–164) | 52.7 (27–154) | 62.5 (30.4–191.5) | 0.553 |

| Median CA 19–9% change (IQR) | − 0.79 (− 0.92 to − 0.50) | − 0.80 (− 0.93 to − 0.49) | − 0.75 (− 0.88 to − 0.51) | 0.211 |

| Pre-NAT CA 19–9 > 37 | 189 (65.2) | 131 (64.5) | 58 (66.7) | 0.727 |

| NAT regimen | 0.0001 | |||

| Gemcitabine-based | 283 (67.9) | 177 (62.3) | 206 (79.7) | |

| 5FU-based | 101 (24.2) | 84 (29.6) | 17 (12.8) | |

| Both | 31 (7.4) | 21 (7.4) | 10 (7.5) | |

| Other | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) | |

| NAT cycles | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–4) | 0.647 |

| Surgery | 0.012 | |||

| Whipple | 324 (77.3) | 210 (73.4) | 114 (85.7) | |

| Distal | 53 (12.7) | 39 (13.6) | 14 (10.5) | |

| Total | 6 (1.4) | 6 (2.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Appleby | 36 (8.6) | 31 (10.8) | 5 (3.8) | |

| AJCC Stage | 0.621 | |||

| 1A | 17 (4.3) | 11 (4) | 6 (4.7) | |

| 1B | 43 (10.8) | 28 (10.3) | 15 (11.7) | |

| 2A | 126 (31.5) | 88 (32.4) | 38 (29.7) | |

| 2B | 181 (45.3) | 119 (43.8) | 62 (48.4) | |

| 3 | 33 (8.3) | 26 (9.6) | 7 (5.5) | |

| Adjuvant therapy | 298 (73) | 206 (73.8) | 92 (71.3) | 0.594 |

| Median OS: months (IQR) | 24.2 (20.9–29.4) | 27.5 (21.4–32.8) | 20.0 (15.9–24.5) | 0.050 |

| Median DFS: months (IQR) | 11.9 (10.6–13.6) | 12.2 (10.5–15.2) | 11.5 (9.9–14.2) | 0.239 |

| Median follow-up: months (IQR) | 39.1 (32.6–48.1) | 39.1 (32.6–49.3) | 42.1 (24.6–51.3) | 0.706 |

SII, systemic immune-inflammation index; IQR, interquartile range; BMI, body mass index; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; T size, tumor size; NAT, neoadjuvant therapy; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; PNI, perineural invasion; LN, lymph node; CA 19–9, carbohydrate antigen 19–9; 5FU, fluorouracil; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; OS, overall survival; DFS, disease-free survival

For the patients with available CA 19–9 data (n = 290), the median baseline pre-NAT CA 19–9 was 337 (IQR, 111–1075), with 1.67% of the patients (n = 7) having normal CA 19–9 (< 37) values at diagnosis. Adjuvant treatment was received by 73% of all the patients (n = 298).

The median OS for the total cohort was 24.2 months, and the DFS was 11.9 months. The median pre-treatment SII was 563 (IQR, 367–988), and the median posttreatment SII was 582 (IQR, 275–1140), with a 0.11% median change in SII after treatment (IQR, − 0.53 to 0.80).

Prognostic Significance of Pre- and Post-neoadjuvant SII

The baseline SII before initiation of NAT was not associated with any clinical outcome. The post-NAT SII was an independent negative predictor of OS as a continuous variable and remained resilient even after adjustment for other preoperative variables (Table S1; hazard ratio [HR], 1.0001; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.00003–1.00014; p = 0.006). No association was found between post-NAT SII and DFS, R0 resection rate, lymph node (LN) positivity, tumor grade, or tumor stage.

We identified a post-NAT SII of 900 as the optimal cutoff point based on previously published values24,25 and confirmation with our own independent analysis (Table S2). A post-NAT SII of 900 or lower was observed in 286 patients, whereas an SII higher than 900 was observed in 133 patients. As shown in Table 1, the demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics were similar between the cohorts, with the exception of a lower BMI (27.48 ± 5.33 vs 25.69 ± 5.43 kg/m2; p = 0.002), a lower preoperative albumin (3.63 ± 0.48 vs 3.50 ± 0.47; p = 0.013), fewer patients receiving 5FU-based NAT (12.8% vs 29.6%; p = 0.0001), and more pancreatic head tumors requiring Whipple resection (85.7% vs. 73.4%; p = 0.012) in patients with a post-NAT SII higher than 900.

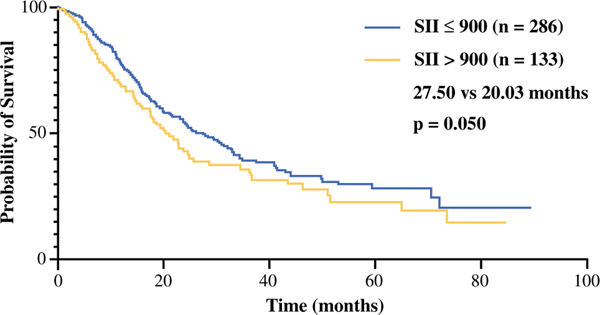

Kaplan–Meier analysis demonstrated that a post-NAT SII higher than 900 was associated with a significantly shorter OS (Fig. 1; p = 0.050). The median OS was 27.50 months (95% CI, 21.43–32.83 months) for the patients with a post-NAT SII of 900 or lower and 20.03 months (95% CI, 15.87–24.53 months) for the patients with an SII higher than 900. In a Cox regression univariate model of survival, post-NAT SII higher than 900, preoperative albumin, preoperative CA 19–9, CA 19–9 response, and administration of adjuvant therapy were prognostic factors for OS (Table 2). In the multivariate analysis, a post-NAT SII higher than 900 was an independent predictor of shorter OS (Table 2; HR, 1.369; 95% CI 1.019–1.838; p = 0.037).

FIG. 1.

Overall survival estimate for patients with a post-neoadjuvant treatment systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) greater than 900 (median overall survival, 27.50 vs 20.03 months; p = 0.050)

TABLE 2.

Predictors of overall survival

| Cox for OS | Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value |

| Post-NAT SII at 900a | 1.321 (0.999–1.746) | 0.051 | 1.369 (1.019–1.838) | 0.037 |

| Agea | 1.009 (0.995–1.023) | 0.196 | – | |

| Sex (F) | 1.053 (0.809–1.373) | 0.697 | ||

| Race (white) | 1.154 (0.543–2.453) | 0.709 | ||

| BMIa | 0.980 (0.954–1.006) | 0.134 | – | |

| BMI-35a | 0.688 (0.407–1.163) | 0.163 | – | |

| Pre-op albumina | 0.662 (0.501–0.874) | 0.004 | 0.781 (0.594–1.026) | 0.075 |

| Age-adjusted CCIa | 1.077 (0.994–1.166) | 0.069 | – | |

| Chronic disease ≥ 3 | 1.151 (0.862–1.538) | 0.341 | ||

| Tumor size | 0.994 (0.854–1.158) | 0.942 | ||

| Pre-NAT CA 19–9 | 1.000 (0.9995–1.0001) | 0.670 | ||

| Post-NAT CA 19–9a | 1.0001 (1.000002–1.0002) | 0.011 | – | |

| CA 19–9 50% changea | 0.816 (0.568–1.172) | 0.271 | – | |

| CA 19–9 80% changea | 0.728 (0.520–1.172) | 0.063 | – | |

| NAT cycles | 0.994 (0.964–1.026) | 0.737 | ||

| Adjuvant therapya | 0.410 (0.317–0.554) | < 0.0001 | 0.407 (0.303–0.547) | < 0.0001 |

No. of subjects = 389; LR χ2 (3) = 43.92; log-likelihood ratio = −1032.72; p < 0.0001

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; NAT, neoadjuvant therapy; SII, systemic immune-inflammation index; BMI, body mass index; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; CA 19–9, carbohydrate antigen 19–9

Indicates variables included in the multivariate model

Prognostic Significance of a Change in SII

We next evaluated the prognostic significance of a change in SII after NAT. We found that 10.2% of all patients (n = 39) had a decrease in SII of 80% or more. Demographic and clinical differences between the patients with and those without a decrease in SII of 80% are shown in Table S3. The patients with at least an 80% decrease in SII after NAT had a higher prevalence of 5FU-based therapy (42.5% vs 20.1%; p = 0.006) and a greater number of NAT cycles (4 vs 3; p = 0.0007) than the patients with less than an 80% reduction in SII. The findings showed a slight negative correlation between the percentage change in SII after NAT and the number of NAT cycles (Fig. S1; Spearman’s correlation coefficient [ρ], − 0.19; p < 0.01). A decrease in SII after NAT was not predictive of a change in clinical outcome, except for an association with CA 19–9 response to treatment. The patients with a change in SII of at least 80% after NAT were more likely also to have a CA 19–9 response (Table S3; 92% vs 73.7%; p = 0.016) after NAT. Dividing the patient cohort based on a 50% reduction in SII yielded similar results.

Association Between SII and CA 19–9 Response to Neoadjuvant Treatment

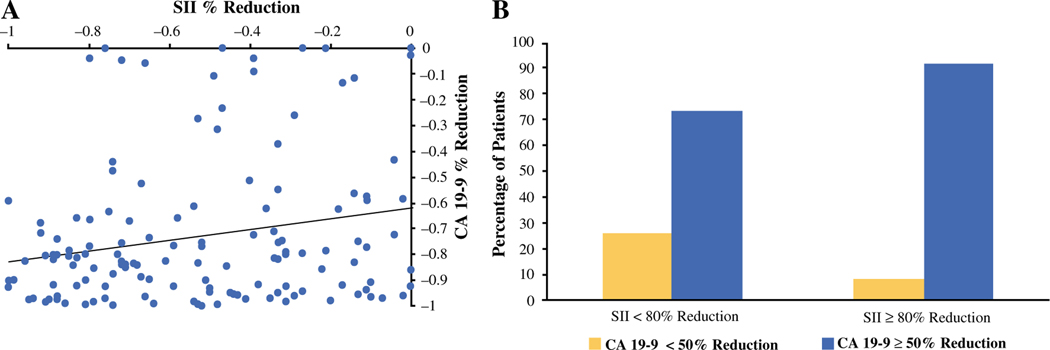

Given that CA 19–9 is an established PDAC biomarker of disease and treatment response, we sought further to explore the association between the change in SII and a change in CA 19–9.15,26 The findings showed a positive association between the percentage change in CA 19–9 and a percentage change in SII as continuous variables (Fig. 2a; Spearman’s correlation coefficient [ρ], 0.173; p = 0.013). Moreover, an 80% reduction in SII after NAT was also associated with a CA 19–9 response (Fig. 2b; Pearson χ2 = 5.82; p = 0.016). In a multivariate model, an 80% decrease in SII independently predicted a CA 19–9 response after NAT (Table 3; HR, 4.22; CI, 1.209–14.750; p = 0.024).

FIG. 2.

Association between the carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA 19–9) percentage change and the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) after neoadjuvant therapy. a ρ = 0.187; p = 0.027. The findings show a dichotomous association between a 50% change in CA 19–9 and an 80% change in SII after neoadjuvant therapy. b Pearson χ2 = 5.82; p = 0.016

TABLE 3.

Predictors of CA 19–9 response

| Dependent variable CA 19–9 50% change | Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value |

| SII 80% changea | 4.053 (1.20–13.69) | 0.024 | 4.22 (1.209–14.750) | 0.024 |

| Age > 65 yearsa | 1.976 (1.132–3.447) | 0.017 | 2.181 (1.191–3.993) | 0.012 |

| Sex (F) | 0.916 (0.528–1.589) | 0.755 | ||

| BMI | 0.985 (0.935–1.039) | 0.581 | ||

| Pre-op albumin | 1.365 (0.774–2.404) | 0.282 | ||

| Age-adjusted CCI | 1.021 (0.851–1.225) | 0.824 | ||

| T sizea | 1.348 (0.961–1.891) | 0.084 | 1.309 (0.912–1.878) | 0.144 |

| NAT cyclesa | 1.313 (1.118–1.542) | 0.001 | 1.278 (1.082–1.510) | 0.004 |

No. subjects = 261; LR χ2 (4) = 25.84, log-likelihood ratio = − 129.351, p < 0.0001

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; SII, systemic immune-inflammation index; BMI, body mass index; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; NAT, neoadjuvant therapy

Indicates variables included in multivariate model

DISCUSSION

Although neoadjuvant therapy is increasingly used for the treatment of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, biomarkers of treatment response are needed to determine the efficacy of treatment regimens for individualized patients and the duration of treatment before attempted surgical resection. This study evaluated the prognostic role of the systemic SII for patients with PDAC receiving neoadjuvant treatment before surgical resection. Post-neoadjuvant SII was determined to be an independent negative predictor of overall survival, and a change in SII after treatment was independently associated with a change in CA 19–9, which has been validated as a marker of treatment response.15 This association supports the prognostic value of SII for patients with PDAC, suggesting that it may be a useful marker in the subset of patients who do not secrete CA 19–9. However, this requires further analysis in a larger cohort.

The incorporation of NAT for patients with borderline-resectable and resectable PDAC has evolved in recent years. Preoperative treatment of PDAC with chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy has been increasingly used for its potential advantages in treating micrometastatic disease, downstaging tumors, improving R0 resection rates, and potentially improving OS compared with upfront resection.9,27,28 Given that neoadjuvant protocols are still under active clinical evaluation, it is critical to have intermediary parameters of treatment response beyond radiographic imaging or pathologic biopsy. Findings have demonstrated that CA 19–9 has some utility as a biomarker of NAT response. However, additional data are required, and a subset of patients do not secrete CA 19–9 and cannot rely on this biomarker. Currently no biomarkers are available to gauge treatment response in these patients. Easily obtainable markers of clinical response would be useful for evaluating novel treatment regimens and would help long term in treatment decision-making by assessing individualized treatment efficacy and the duration of the NAT course, which still needs to be definitively established.29

The complete blood count and differential required to calculate the SII is a common laboratory test ordered for patients that makes the SII a potentially compelling biomarker of interest because no specialized laboratory analyses are required. The SII has been evaluated in several solid tumors, including gastrointestinal malignancies.30,31 For patients with resectable PDAC, the preoperative SII has been shown to be an independent negative predictor of disease-free survival.24 The SII has also demonstrated great predictive ability of OS than the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) or the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) for patients with resectable PDAC.25 For patients with advanced, nonresectable PDAC, the SII was found to be an independent negative predictor of overall survival for those with normal or elevated levels of CA 19–9.32

In contrast to the existing literature on SII in PDAC, our study showed that baseline pre-treatment SII did not predict clinical outcome.24 This important finding suggests that NAT may alter tumor biology and outcome to influence prognosis. We identified post-NAT SII as an independent negative predictor of OS as a continuous variable. When the cohort was divided into post-NAT SII above and below 900, the patients with a post-treatment SII of 900 or lower had a median survival benefit of approximately seven months compared with the patients who had an SII of 900 or higher. A post-NAT SII greater than 900 appears to influence survival because it is an independent predictor of overall survival.

Reduction in CA 19–9 after NAT for PDAC remains the gold standard of biomarkers in predicting response to treatment. A CA 19–9 response greater than 50% after NAT is an independent predictor of overall survival and associated with improved R0 resection rate and histopathologic response.15 In our study, change in SII closely paralleled change in CA 19–9 after NAT. The SII is indicative of the general inflammatory response to cancer and can be combined with CA 19–9 for improved prognostic ability. Moreover, CA 19–9 is not a prognostic indicator in all patients with PDAC. As many as 18% of patients are CA 19–9 “non-secretors” and have normal CA 19–9 levels throughout diagnosis and treatment.26 The SII could be a helpful prognostic indicator of OS for these patients, but further evaluation is required for specific study of this patient cohort.

Consistent with previous studies identifying improved clinical outcomes associated with the administration of FOLFIRINOX,33,34 we found that patients with a post-NAT SII lower than 900 and those with an 80% or greater decrease in SII, predictive of better prognosis and CA 19–9 response, received a significantly higher rate of 5FU-based therapy than gemcitabine-based therapy.

The prognostic value of SII is deeply rooted in the tumor biology of PDAC. Chronic inflammation is a hallmark of PDAC, promoting cell proliferation and enhancing tumor cell invasiveness, migration, and metastasis.21,22,35 Chronic pancreatitis contributes to PDAC development with the formation of pancreatic intraepithelial lesions and is a known risk factor for PDAC.36–38 Neutrophils are central to the inflammatory response and are directly linked to cancer progression.39 Neutrophils also revert cancer cell senescence and promote immune evasion with inhibition of T cell activation and proliferation as well as recruitment of regulatory T cells.40,41 Neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation, whereby neutrophils produce extracellular webs of DNA, histones, and granule proteins, has been implicated in several diseases involving sterile inflammation, including pancreatitis42,43 and PDAC.44,45 Neutrophils are essential to the metastatic cascade, recruiting tumor cells to the endothelium, priming premetastatic niches, and tethering circulating tumor cells.46–48 Increased neutrophils are associated with necrosis, a poor prognostic factor for patients with PDAC and other tumor types.49,50

One major complication of PDAC and its subsequent treatment with surgery or chemotherapy is a hypercoagulable state that often manifests as thromboembolic disease.51–53 The generation of an intrinsic hypercoagulable state in PDAC is due to an activated coagulation cascade that acts in a feed-forward loop to promote tumor growth and metastasis.54 Activated platelets bind tumor cells via the adhesion receptor P selectin and direct tumor growth and metastasis by secreting proangiogenic and tumor-derived growth factors, namely, platelet-derived microparticles, tissue factor, and platelet-derived growth factor.55–57

This study was limited by the retrospective nature of its design. The timing of post-therapy blood draws used to calculate SII was variable, which was a limitation of the study. Because chemotherapy may suppress blood counts used in the SII calculation, using the immediate preoperative values, which typically are assessed three weeks after completion of therapy, allowed for return to baseline levels before assessment. Furthermore, because all the patients included in this analysis underwent surgical resection, it is not clear how SII influences patients who initiate chemotherapy but ultimately do not undergo surgical resection. Additional evaluations are necessary at multiple institutions before introduction of SII as a prognostic indicator in clinical practice.

CONCLUSION

This study suggests that elevated post-treatment SII is an independent negative prognostic indicator of survival after neoadjuvant treatment of PDAC. Moreover, an 80% reduction in SII is predictive of CA 19–9 response, and the combined prognostic ability of both markers warrants further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE Dr. Nathan Bahary has held Advisory Roles/Boards for BioLIneRx, AstraZeneca, Exelixis, BMS, and Thermo Fisher. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interests.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434–019-08094–0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aier I, Semwal R, Sharma A, Varadwaj PK. A systematic assessment of statistics, risk factors, and underlying features involved in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;58:104–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2913–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamamoto T, Yagi S, Kinoshita H, et al. Long-term survival after resection of pancreatic cancer: a single-center retrospective analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:262–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopez NE, Prendergast C, Lowy AM. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: definitions and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10740–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrone CR, Marchegiani G, Hong TS, et al. Radiological and surgical implications of neoadjuvant treatment with FOLFIRINOX for locally advanced and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 2015;261:12–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeung RS, Weese JL, Hoffman JP, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation in pancreatic and duodenal carcinoma: a Phase II study. Cancer. 1993;72:2124–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spitz FR, Abbruzzese JL, Lee JE, et al. Preoperative and postoperative chemoradiation strategies in patients treated with pancreaticoduodenectomy for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:928–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mokdad AA, Minter RM, Zhu H, et al. Neoadjuvant therapy followed by resection versus upfront resection for resectable pancreatic cancer: a propensity score-matched analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:515–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz MH, Fleming JB, Bhosale P, et al. Response of borderline resectable pancreatic cancer to neoadjuvant therapy is not reflected by radiographic indicators. Cancer. 2012;118:5749–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christians KK, Tsai S, Mahmoud A, et al. Neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX for borderline resectable pancreas cancer: a new treatment paradigm? Oncologist. 2014;19:266–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner M, Antunes C, Pietrasz D, et al. CT evaluation after neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX chemotherapy for borderline and locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Eur Radiol. 2017;27:3104–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kluger MD, Rashid MF, Rosario VL, et al. Resection of locally advanced pancreatic cancer without regression of arterial encasement after modern-era neoadjuvant therapy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;22:235–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cassinotto C, Sa-Cunha A, Trillaud H. Radiological evaluation of response to neoadjuvant treatment in pancreatic cancer. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2016;97:1225–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boone BA, Steve J, Zenati MS, et al. Serum CA 19–9 response to neoadjuvant therapy is associated with outcome in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:4351–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tzeng CW, Balachandran A, Ahmad M, et al. Serum carbohydrate antigen 19–9 represents a marker of response to neoadjuvant therapy in patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. HPB Oxford. 2014;16:430–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ballehaninna UK, Chamberlain RS. Serum CA 19–9 as a biomarker for pancreatic cancer: a comprehensive review. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2011;2:88–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poruk KE, Gay DZ, Brown K, et al. The clinical utility of CA19–9 in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: diagnostic and prognostic updates. Curr Mol Med. 2013;13:340–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishihara S, Yazawa S, Iwasaki H, et al. Alpha (1,3/1,4)fucosyltransferase (FucT-III) gene is inactivated by a single amino acid substitution in Lewis histo-blood-type-negative individuals. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;196:624–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haab BB, Huang Y, Balasenthil S, et al. Definitive characterization of CA 19–9 in resectable pancreatic cancer using a reference set of serum and plasma specimens. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hausmann S, Kong B, Michalski C, Erkan M, Friess H. The roleof inflammation in pancreatic cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;816:129–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu B, Yang XR, Xu Y, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of patients after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:6212–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aziz MH, Sideras K, Aziz NA, et al. The systemic-immune-inflammation index independently predicts survival and recurrence in resectable pancreatic cancer and its prognostic value depends on bilirubin levels: a retrospective multicenter cohort study. Ann Surg. 2018;270:139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jomrich G, Gruber ES, Winkler D, et al. Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII) predicts poor survival in pancreatic cancer patients undergoing resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019. 10.1007/s11605-019-04187-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rieser CJ, Zenati M, Hamad A, et al. CA19–9 on postoperative surveillance in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: predicting recurrence and changing prognosis over time. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:3483–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belli C, Cereda S, Anand S, Reni M. Neoadjuvant therapy in resectable pancreatic cancer: a critical review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39:518–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhan HX, Xu JW, Wu D, et al. Neoadjuvant therapy in pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Cancer Med. 2017;6:1201–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epelboym I, Zenati MS, Hamad A, et al. Analysis of perioperative chemotherapy in resected pancreatic cancer: identifying the number and sequence of chemotherapy cycles needed to optimize survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:2744–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y, Lin S, Yang X, Wang R, Luo L. Prognostic value of pretreatment systemic immune-inflammation index in patients with gastrointestinal cancers. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:5555–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhong JH, Huang DH, Chen ZY. Prognostic role of systemic immune-inflammation index in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:75381–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang K, Hua YQ, Wang D, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Transl Med. 2019;17:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dhir M, Zenati MS, Hamad A, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel for neoadjuvant treatment of resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic head adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:1896–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Conroy T, Hammel P, Hebbar M, et al. FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine as adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2395–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKay CJ, Glen P, McMillan DC. Chronic inflammation and pancreatic cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guerra C, Collado M, Navas C, et al. Pancreatitis-induced inflammation contributes to pancreatic cancer by inhibiting oncogene-induced senescence. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:728–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guerra C, Schuhmacher AJ, Canamero M, et al. Chronic pancreatitis is essential for induction of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by K-Ras oncogenes in adult mice. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:291–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirkegard J, Mortensen FV, Cronin-Fenton D. Chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1366–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coffelt SB, Wellenstein MD, de Visser KE. Neutrophils in cancer: neutral no more. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:431–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Di Mitri D, Toso A, Chen JJ, et al. Tumour-infiltrating Gr-1? myeloid cells antagonize senescence in cancer. Nature. 2014;515:134–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mantovani A, Cassatella MA, Costantini C, Jaillon S. Neutrophilsin the activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:519–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murthy P, Singhi AD, Ross MA, et al. Enhanced neutrophil extracellular trap formation in acute pancreatitis contributes to disease severity and is reduced by chloroquine. Frontiers Immunol. 2019;10:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Merza M, Hartman H, Rahman M, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps induce trypsin activation, inflammation, and tissue damage in mice with severe acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1920–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boone BA, Orlichenko L, Schapiro NE, et al. The receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) enhances autophagy and neutrophil extracellular traps in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2015;22:326–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boone BA, Murthy P, Miller-Ocuin J, et al. Chloroquine reduces hypercoagulability in pancreatic cancer through inhibition of neutrophil extracellular traps. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cools-Lartigue J, Spicer J, McDonald B, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps sequester circulating tumor cells and promote metastasis. J Clin Investig. 2013;123:3446–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bald T, Quast T, Landsberg J, et al. Ultraviolet radiation-induced inflammation promotes angiotropism and metastasis in melanoma. Nature. 2014;507:109–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee W, Ko SY, Mohamed MS, Kenny HA, Lengyel E, Naora H. Neutrophils facilitate ovarian cancer premetastatic niche formation in the omentum. J Exp Med. 2019;216:176–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gaida MM, Gunther F, Wagner C, et al. Expression of theCXCR6 on polymorphonuclear neutrophils in pancreatic carcinoma and in acute, localized bacterial infections. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;154:216–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chao T, Furth EE, Vonderheide RH. CXCR2-dependent accumulation of tumor-associated neutrophils regulates T-cell immunity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4:968–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khorana AA, Fine RL. Pancreatic cancer and thromboembolic disease. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:655–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boone BA, Zenati MS, Rieser C, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism for patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma undergoing preoperative chemotherapy followed by surgical resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:1503–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ansari D, Ansari D, Andersson R, Andren-Sandberg A. Pancreatic cancer and thromboembolic disease 150 years after Trousseau. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2015;4:325–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meikle CK, Kelly CA, Garg P, Wuescher LM, Ali RA, Worth RG. Cancer and thrombosis: the platelet perspective. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2016;4:147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coupland LA, Chong BH, Parish CR. Platelets and P-selectin control tumor cell metastasis in an organ-specific manner and independently of NK cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72:4662–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Varon D, Hayon Y, Dashevsky O, Shai E. Involvement of platelet-derived microparticles in tumor metastasis and tissue regeneration. Thromb Res. 2012;130(Suppl 1):S98–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dashevsky O, Varon D, Brill A. Platelet-derived microparticles promote invasiveness of prostate cancer cells via upregulation of MMP-2 production. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1773–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.