Abstract

Background

Triglyceride glucose (TyG) index is considered a reliable alternative marker of insulin resistance and an independent predictor of cardiovascular (CV) outcomes. However, the prognostic value of TyG index in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) remains unclear.

Methods

A total of 1932 consecutive patients with T2DM and AMI were enrolled in this study. Patients were divided into tertiles according to their TyG index levels. The incidence of major adverse cardiac and cerebral events (MACCEs) was recorded. The TyG index was calculated as the ln [fasting triglycerides (mg/dL) × fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL)/2].

Results

Competing risk regression revealed that the TyG index was positively associated with CV death [2.71(1.92 to 3.83), p < 0.001], non-fatal MI [2.02(1.32 to 3.11), p = 0.001], cardiac rehospitalization [2.42(1.81 to 3.24), p < 0.001], revascularization [2.41(1.63 to 3.55), p < 0.001] and composite MACCEs [2.32(1.92 to 2.80), p < 0.001]. The area under ROC curve of the TyG index for predicting the occurrence of MACCEs was 0.604 [(0.578 to 0.630), p < 0.001], with the cut-off value of 9.30. The addition of TyG index to a baseline risk model had an incremental effect on the predictive value for MACCEs [net reclassification improvement (NRI): 0.190 (0.094 to 0.337); integrated discrimination improvement (IDI): 0.027 (0.013 to 0.041); C-index: 0.685 (0.663 to 0.707), all p < 0.001].

Conclusions

The TyG index was significantly associated with MACCEs, suggesting that the TyG index may be a valid marker for risk stratification and prognosis in patients with T2DM and AMI.

Trial registration Retrospectively registered.

Keywords: Insulin resistance (IR), Triglyceride-glucose index (TyG index), Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), Acute myocardial infarction (AMI), Major adverse cardiac and cerebral events (MACCEs)

Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) has been recognized as the leading cause of morbidity and mortality of cardiovascular diseases(CVDs) worldwide [1]. The World Bank estimated that the number of individuals with MI in China will increase to 23 million by 2030 [2]. What’s more, some AMI patients remain at high risk for recurrent cardiovascular events (CVEs) despite the use of current guideline-recommended treatment. This risk is particularly high among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), accounting for approximately 37% of AMI cases in China, and is classified as extreme-risk group for recurrent CVEs [3]. Studies have shown that T2DM is significantly correlated with more complex coronary lesions and worse prognosis in AMI patients [4, 5].Therefore, early identification of the residual risk factors of AMI patients with T2DM is crucial for better clinical management to reduce future CVEs.

Insulin resistance (IR), a crucial mediator of metabolic disorders, not only contributes to the pathogenesis of CVDs, but also correlates with adverse cardiovascular (CV) outcomes [6–8]. Although the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp is the gold-standard test for IR assessment [9], it is not commonly used in clinical settings and large population studies due to the complex testing process [10]. Given that IR is significantly associated with the chronic increase in plasma glucose and triglycerides (TGs) [11], researchers hypothesized that the combination of plasma glucose and TGs might predict IR. Triglyceride glucose (TyG) index, which combines fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and TGs levels, has been shown to be significantly correlated with IR measured by the hyperinsulinaemic-euglycaemic clamp test [12] and homeostasis model assessment of IR (HOMA-IR) [13]. The TyG index was regarded as a reproducible, reliable, and valid surrogate marker of IR [12, 14, 15]. Numerous studies have indicated that the TyG index was significantly correlated with the occurrence of CVDs and poor CV prognosis [16–25]. However, no previous study has exclusively investigated the predictive value of the TyG index for adverse CVEs in AMI patients with T2DM. Our study was to fill this knowledge gap.

Methods

Study population

Study subjects were identified from the Cardiovascular Center of Beijing Friendship Hospital Database (CBD) Bank. A total of 5169 consecutive patients were diagnosed with AMI and underwent coronary angiography from January 2013 to August 2020. Of the 5169 patients, 3237 were excluded according to the exclusion criteria, which were (1) without T2DM, (2) with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 30 mL/min/1.73m2 or chronic dialysis, severe hepatic dysfunction, severe acute infection, malignant tumor, suspected familial hypertriglyceridemia [plasma TGs ≥ 5.65 mmol/L], (3) with cardiogenic shock, prior coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), severe valvulopathy or congenital heart disease requiring cardiac surgery, (4) lack of clinical or follow-up data. Finally, 1932 patients were included in this analysis. The patients were divided into 2 groups according to the occurrence of MACCEs during the follow-up: the MACCEs group (n = 735) and the No-MACCEs group (n = 1197). In addition, the patients were also divided into tertiles according to their TyG index levels (TyG index ≤ 8.91 group, n = 647; 8.91 < TyG index < 9.54 group, n = 639; TyG index ≥ 9.54 group, n = 646). All patients were followed up till October 31, 2020 with a median follow up of 26.8 (IQR: 12.4, 50.7) months.

Data collections and definitions

The data collection process was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Friendship Hospital affiliated to Capital Medical University and was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients’ demographics, medical history, laboratory test results, echocardiographic, and angiographic evaluation results were collected and verified using an electronic medical recording system. The concentrations of TGs and FPG in the first fasting blood samples during the stay in the hospital, which were obtained after at least 10 h of fasting, were determined at the central laboratory of Beijing Friendship Hospital. The TyG index was calculated as ln [fasting TGs (mg/dL) × FPG (mg/dL)/2] [12]. The Single Point Insulin Sensitivity Estimator(SPISE) and TGs/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol(HDL-C) ratio have been proven to be effective surrogate indexs for insulin sensitivity, so they are also included in the baseline clinical characteristics. The novel formula for SPISE was computed as follows: SPISE = 600 × HDL-C0.185/(TGs0.2 × body mass index(BMI)1.338) [26], with fasting HDL-C (mg/dL), fasting TGs (mg/dL), and BMI (kg/m2). The TGs/HDL-C ratio was calculated as TGs (mg/dL)/HDL-C(mg/dL). The outcomes from major adverse cardiac and cerebral events(MACCEs) were collected and recorded during clinical follow-up visits.

Criteria for T2DM include: (1) previously diagnosed T2DM under treatment of antidiabetic medication; (2) the typical symptoms of DM with a FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, and/or random blood glucose (RBG) ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, and/or 2-h plasma glucose level after oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) ≥ 11.1 mmol/L [27]. Hypertension (HT) is defined as the blood pressure is greater than or equal to 140/90 mmHg three times on different days, or the antihypertensive drugs are used. The criteria for dyslipidaemia is that fasting total cholesterol(TC) > 200 mg/dL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol(LDL-C) > 130 mg/dL, TGs > 150 mg/dL, HDL-C < 40 mg/dL, or previous use of lipid-lowering drugs. AMI, including non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction(NSTEMI) and ST-elevation myocardial infarction(STEMI), was defined as chest pain with new ST-segment changes and elevation of myocardial necrosis markers to at least twice of the upper limit of the normal range. MACCEs included all-cause death, non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke, cardiac rehospitalization (admission because of angina or heart failure), and revascularization. CV death was defined as fatal stroke and MI, sudden death, and other cardiac death. All-cause death was defined as the incidence of CV death or non-CV death. Non-fatal stroke, including ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, was defined as cerebral dysfunction caused by cerebral vascular obstruction or sudden rupture and was diagnosed based on signs of neurological dysfunction or evidence of brain imaging. Cardiac rehospitalization refers to rehospitalization for angina pectoris or heart failure. Any coronary revascularization was defined as a revascularization of the target vessel or non-target vessels.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (IQR). Comparisons between the 2 study groups were analyzed by Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test. Categorical variables were expressed as number and percentage and compared using the Pearson chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Two -sample T-test power analysis showed that the testing power of TyG index is 1. Baseline variables that were significantly correlated with MACCEs by univariate analysis and clinically relevant were entered into the multivariate model. Also, intercorrelations among variables were taken into consideration in the multivariate analysis. Considering that there is a competitive risk relationship between all-cause death and other events, the competing risk model is used to verify the independent predictive effect of the TyG index on each type of MACCEs. The cumulative incidence of MACCEs was estimated by competing risk regression curves. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to determine the optimal cutoff point value of TyG index for predicting MACCEs. We also calculated net reclassification improvement (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) to determine the extent to which the addition of TyG index improves the predictive power of existing baseline risk model. Statistical tests were performed with IBM SPSS statistics 24, StataMP 14 and the R Programming Language. A two-tailed p value < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients

Baseline characteristics of the total population and groups stratified by with or without MACCEs were presented in Table 1. The TyG index level and the proportion of the patients with TyG ≥ 9.54 were significantly higher in MACCEs group than those in the No-MACCEs group. Patients with MACCEs showed higher age, TGs/HDL-C ratio, hypersensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), FPG, TGs and creatinine, longer duration of diabetes, and higher prevalence of previous stroke and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) history. In addition, patients in MACCEs group had lower levels of hemoglobin, albumin and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). As for the angiographic findings, those with MACCEs showed lower proportions of left main coronary artery (LM)/three-vessel, proximal left anterior descending (LAD) and PCI/CABG treatment during hospitalization.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics of the patients stratified by MACCEs

| Variable | Total population n = 1932 | No-MACCEs n = 1197 | MACCEs n = 735 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin sensitivity surrogate index | ||||

| TyG index | 9.26 ± 0.73 | 9.17 ± 0.72 | 9.42 ± 0.72 | < 0.001 |

| TyG ≤ 8.91 | 647 (33.5) | 467(39.0) | 180 (24.5) | < 0.001 |

| 8.91 < TyG < 9.54 | 639 (33.1) | 401(33.5) | 238 (32.4) | |

| TyG ≥ 9.54 | 646 (33.4) | 329(27.5) | 317 (43.1) | |

| TGs/HDL-C ratio | 3.6 (2.4,5.6) | 3.3(2.3,5.1) | 4.2 (2.7,6.3) | < 0.001 |

| SPISE index | 5.9 ± 1.5 | 5.9 ± 1.5 | 5.8 ± 1.5 | 0.099 |

| Age, years | 65.4 ± 12.0 | 64.1 ± 11.6 | 67.4 ± 12.4 | < 0.001 |

| Male gender | 1324 (68.5) | 825(68.9) | 499 (67.9) | 0.636 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.8 ± 3.5 | 25.9 ± 3.5 | 25.6 ± 3.7 | 0.150 |

| SBP, mmHg | 130.9 ± 22.2 | 130.3 ± 21.4 | 131.7 ± 23.5 | 0.187 |

| DBP, mmHg | 73.8 ± 12.6 | 73.9 ± 12.3 | 73.7 ± 13.0 | 0.640 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Current/ex-Smoker | 1102 (57.0) | 698 (58.3) | 404 (55.0) | 0.149 |

| Duration of diabetes, years | 6.0 (1.0,12.0) | 6.0 (1.0,10.0) | 8.0 (1.0,14.0) | < 0.001 |

| CKD | 113 (5.8) | 51 (4.3) | 62 (8.4) | < 0.001 |

| Stroke | 396 (20.5) | 206 (17.2) | 190 (25.9) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1450 (75.1) | 887 (74.1) | 563 (76.6) | 0.218 |

| Dyslipidemia | 931 (48.2) | 584 (48.8) | 347 (47.2) | 0.500 |

| Previous MI | 218 (11.3) | 135 (11.3) | 83 (11.3) | 0.992 |

| Past PCI | 321 (16.6) | 183 (15.3) | 138 (18.8) | 0.046 |

| Medication used before admission | ||||

| Antiplatelet agent | 618 (32.0) | 364 (30.4) | 254 (34.6) | 0.058 |

| ACEI/ARB | 590(30.5) | 364(30.4) | 226(30.7) | 0.875 |

| Beta-blocker | 291(15.1) | 171(14.3) | 120(16.3) | 0.223 |

| Statins | 404(20.9) | 249(20.8) | 155(21.1) | 0.881 |

| Laboratory values | ||||

| WBC, 109/L | 8.1 (6.4,10.1) | 8.0 (6.5,9.9) | 8.2 (6.4,10.3) | 0.342 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 132.3 ± 20.0 | 133.9 ± 19.2 | 129.8 ± 20.9 | < 0.001 |

| Hs-CRP, mg/L | 12.2 (5.4,12.5) | 12.1 (6.3,12.5) | 12.3 (4.7,15.0) | 0.006 |

| RBG at admission, mmol/L | 11.1 (8.3,14.3) | 10.8 (8.1,14.0) | 11.5 (8.5,14.6) | 0.026 |

| FPG, mmol/L | 8.0 (6.3,10.4) | 7.9 (6.2,10.1) | 8.3 (6.4,11.1) | 0.001 |

| HbA1c,% | 7.8 ± 1.7 | 7.8 ± 1.7 | 7.8 ± 1.6 | 0.220 |

| Albumin, g/L | 36.0 ± 3.2 | 36.2 ± 3.0 | 35.8 ± 3.5 | 0.015 |

| Creatinine, umol/L | 80.9 (68.4,95.5) | 77.5 (66.2,92.2) | 85.9 (72.3,106.0) | < 0.001 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73m2 | 82.1 (63.2,98.5) | 86.9 (68.8,101.8) | 74.2 (56.1,90.9) | < 0.001 |

| TC, mmol/L | 4.38 (3.68,5.04) | 4.41(3.69,5.10) | 4.35 (3.65,5.00) | 0.276 |

| TGs, mmol/L | 1.51 (1.07,2.26) | 1.40 (1.01,2.09) | 1.78 (1.24,2.55) | < 0.001 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.58 ± 0.79 | 2.60 ± 0.79 | 2.56 ± 0.79 | 0.315 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.01 ± 0.24 | 1.00 ± 0.24 | 1.02 ± 0.25 | 0.253 |

| Initial diagnosis | ||||

| NSTEMI | 1042 (53.9) | 630 (52.6) | 412 (56.1) | 0.143 |

| STEMI | 890 (46.1) | 567 (47.4) | 323 (43.9) | |

| Echocardiography | ||||

| LVEF | 57.4 ± 10.3 | 58.8 ± 9.4 | 55.0 ± 11.3 | < 0.001 |

| Angiography findings | ||||

| LM/three-vessel | 1369 (70.9) | 881 (73.6) | 488 (66.4) | 0.001 |

| Proximal LAD | 948 (49.1) | 631 (52.7) | 317 (43.1) | < 0.001 |

| In-hospital treatment | ||||

| PCI/CABG | 1501 (77.7) | 1003 (83.8) | 498 (67.8) | < 0.001 |

| Antiplatelet agent | 1854 (96.0) | 1157 (96.7) | 697 (94.8) | 0.047 |

| ACEI/ARB | 1291 (66.8) | 816 (68.2) | 475 (64.6) | 0.108 |

| Beta-blocker | 1434 (74.2) | 905 (75.6) | 529 (72.0) | 0.076 |

| Statins | 1673 (86.6) | 1072 (89.6) | 601 (81.8) | < 0.001 |

| Hypoglycemic agents | ||||

| Metformin | 655 (33.9) | 437 (36.5) | 218 (29.7) | 0.002 |

| Alpha-glucosidase inhibitor | 1209 (62.6) | 760 (63.5) | 449 (61.1) | 0.289 |

| Sulfonylurea | 434 (22.5) | 281 (23.5) | 153 (20.8) | 0.174 |

| DPP-4i | 20 (1.0) | 16 (1.3) | 4 (0.5) | 0.095 |

| Insulin | 577 (29.9) | 312 (26.1) | 265 (36.1) | < 0.001 |

Dates are presented as mean ± SD, median (IQR) or number (%)

MACCEs, major adverse cardiac and cerebral events; TyG, triglyceride-glucose index; TGs, triglycerides; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; SPISE index, the Single Point Insulin Sensitivity Estimator; BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; ACEI/ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; WBC, white blood cell; Hs-CRP, hypersensitive C-reactive protein; RBG, random blood glucose; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; TC, total cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NSTEMI, Non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LM, left main coronary artery; LAD, left anterior descending; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; DPP-4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor

TyG index predicted the occurrence of MACCEs

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses and predictors for composite MACCEs were presented in Table 2. In the univariate analysis, the predictor associated with MACCEs occurrence were TyG index, age, BMI, duration of diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), previous stroke, past PCI, antiplatelet agent used before admission, white blood cell(WBC), hs-CRP, hemoglobin, FPG, RBG at admission, albumin, creatinine, eGFR, TGs, LVEF, LM/three-disease, proximal LAD, in-hospital treatment[PCI/CABG, antiplatelet agent, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker (ACEI/ARB), beta-blocker and statins] and hypoglycemic agents(insulin). FPG, RBG at admission, TGs and TyG index had a high correlation (p < 0.001). In addition, CKD and creatinine were significantly correlated with eGFR (p < 0.001), and hs-CRP was significantly correlated with WBC (p < 0.001). Therefore, FPG, RBG at admission, TGs, CKD, creatinine and hs-CRP were not included in the multivariate model. After adjusting for age, BMI and other confounding factors, multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis showed that TyG index, age, previous stroke, WBC, eGFR, LVEF and in-hospital treatment(PCI/CABG, antiplatelet agent, beta-blocker and statins) independently predicted the occurrence of MACCEs in patients with AMI and T2DM.

Table 2.

Independent predictors of composite MACCEs

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | p value | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | p value | |

| Insulin sensitivity surrogate index | ||||

| TyG index | ||||

| TyG ≤ 8.91 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 8.91 < TyG < 9.54 | 1.33 (1.09,1.61) | 0.004 | 1.58(1.33,1.88) | < 0.001 |

| TyG ≥ 9.54 | 1.93 (1.61,2.32) | < 0.001 | 2.32 (1.92,2.80) | < 0.001 |

| TGs/HDL-C ratio | 1.01 (0.99,1.03) | 0.675 | ||

| SPISE index | 0.98 (0.93,1.03) | 0.318 | ||

| Age, y | 1.03 (1.01,1.04) | < 0.001 | 1.02 (1.01,1.03) | < 0.001 |

| Male gender | 1.04 (0.88.1.20) | 0.642 | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 1.02 (1.01,1.04) | 0.046 | 0.99 (0.97,1.01) | 0.357 |

| SBP, mmHg | 1.01 (0.99,1.02) | 0.546 | ||

| DBP, mmHg | 0.99 (0.98,1.00) | 0.461 | ||

| Medical history | ||||

| Current/ex-Smoker | 0.93 (0.80,1.07) | 0.302 | ||

| Duration of diabetes, years | 1.02 (1.01,1.03) | < 0.001 | 1.02 (0.99,1.03) | 0.857 |

| CKD | 1.85 (1.43,2.40) | < 0.001 | ||

| Stroke | 1.59 (1.35,1.87) | < 0.001 | 1.38 (1.16,1.63) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1.17 (0.98,1.39) | 0.075 | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 1.04 (0.90,1.21) | 0.558 | ||

| Previous MI | 1.15 (0.91,1.44) | 0.243 | ||

| Past PCI | 1.25 (1.04,1.50) | 0.020 | 0.87 (0.71,1.08) | 0.205 |

| Medication used before admission | ||||

| Antiplatelet agent | 1.25 (1.08,1.46) | 0.004 | 0.95 (0.80,1.13) | 0.542 |

| ACEI/ARB | 1.09 (0.94,1.28) | 0.261 | ||

| Beta-blocker | 1.20 (0.98,1.45) | 0.074 | ||

| Statins | 1.15(0.96,1.38) | 0.120 | ||

| Laboratory values | ||||

| WBC,109/L | 1.04 (1.02,1.05) | < 0.001 | 1.03 (1.02,1.04) | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 0.98 (0.97,0.99) | < 0.001 | 0.99 (0.98,1.01) | 0.776 |

| Hs-CRP, mg/L | 1.02 (1.01,1.03) | < 0.001 | ||

| RBG at admission, mmol/L | 1.02 (1.01,1.03) | 0.042 | ||

| FPG, mmol/L | 1.05 (1.03, 1.08) | < 0.001 | ||

| HbA1c, % | 1.04 (0.99,1.09) | 0.066 | ||

| Albumin, g/L | 0.97 (0.95,0.99) | 0.004 | 1.01 (0.98,1.03) | 0.826 |

| Creatinine, umol/L | 1.02 (1.01,1.03) | < 0.001 | ||

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73m2 | 0.98 (0.96,0.99) | < 0.001 | 0.98(0.97,0.99) | 0.004 |

| TC, mmol/L | 1.01 (0.95,1.09) | 0.673 | ||

| TGs, mmol/L | 1.08 (1.01,1.12) | < 0.001 | ||

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 1.01 (0.92,1.11) | 0.821 | ||

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 0.94 (0.70,1.27) | 0.705 | ||

| Echocardiography | ||||

| LVEF,% | 0.97 (0.96,0.98) | < 0.001 | 0.98 (0.97,0.99) | < 0.001 |

| Angiography findings | ||||

| LM/three-disease | 1.39 (1.19,1.62) | < 0.001 | 1.15 (0.92,1.42) | 0.222 |

| Proximal LAD | 1.38 (1.20,1.60) | < 0.001 | 1.13 (0.96,1.33) | 0.150 |

| In-hospital treatment | ||||

| PCI/CABG | 0.52 (0.45,0.61) | < 0.001 | 0.63 (0.53,0.74) | < 0.001 |

| Antiplatelet agent | 0.67 (0.49,0.94) | 0.018 | 0.61 (0.42,0.88) | 0.008 |

| ACEI/ARB | 0.77 (0.66,0.89) | 0.001 | 0.89 (0.76,1.05) | 0.167 |

| Beta-blocker | 0.75 (0.64,0.88) | < 0.001 | 0.79 (0.67,0.94) | 0.009 |

| Statins | 0.56 (0.47,0.68) | < 0.001 | 0.64 (0.52,0.78) | < 0.001 |

| Hypoglycemic agents | ||||

| Metformin | 0.86 (0.74,1.01) | 0.068 | 0.98 (0.83,1.16) | 0.804 |

| Alpha-glucosidase inhibitor | 0.94 (0.81,1.08) | 0.367 | ||

| Sulfonylurea | 0.85 (0.71,1.02) | 0.074 | 0.88(0.73,1.06) | 0.174 |

| DPP-4i | 0.78 (0.29,2.08) | 0.619 | ||

| Insulin | 1.40 (1.20,1.63) | < 0.001 | 1.13(0.96,1.33) | 0.139 |

MACCEs, major adverse cardiac and cerebral events; TyG, triglyceride-glucose index; TGs, triglycerides; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; SPISE index, the Single Point Insulin Sensitivity Estimator; BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; ACEI/ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; WBC, white blood cell; Hs-CRP, hypersensitive C-reactive protein; RBG, random blood glucose; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; TC, total cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LM, left main coronary artery; LAD, left anterior descending; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; DPP-4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor

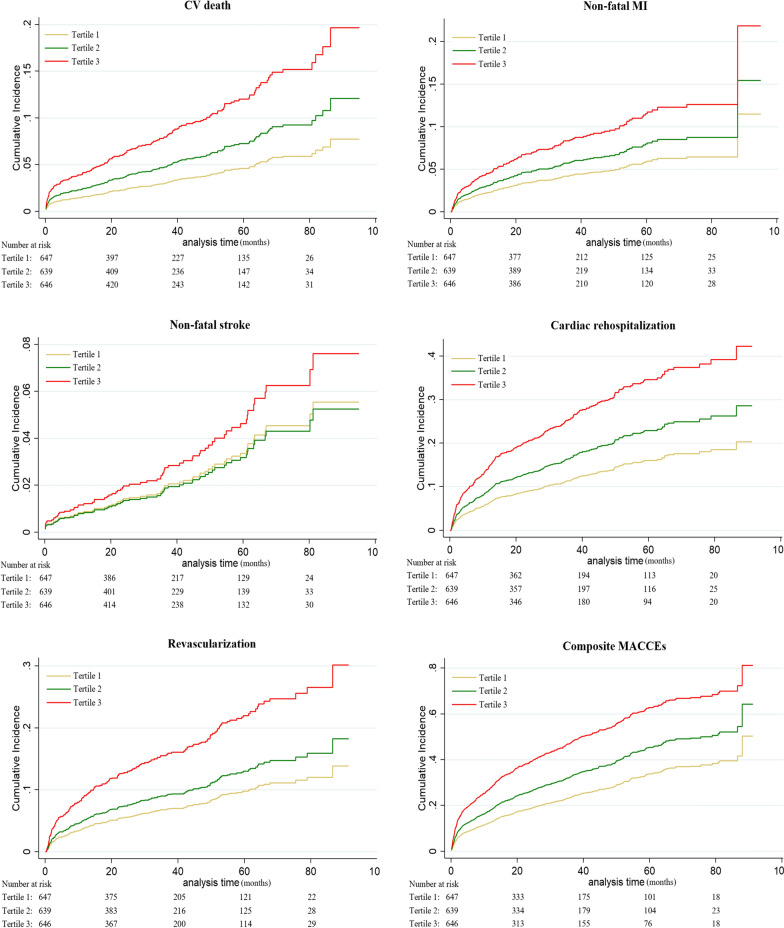

During the median of 26.8-month follow-up, MACCEs occurred in 735 (38.0%) patients [all-cause death: 292 (15.1%); CV death: 233 (12.1%); non-fatal MI: 161 (8.3%); non-fatal stroke: 76 (3.9%); cardiac rehospitalization: 354 (18.3%); revascularization: 226 (11.7%)]. Figure 1 and Table 3 showed the competing risk regression analysis for MACCEs. On unadjusted competing risk modeling, the cumulative incidence of CV death, non-fatal MI, cardiac rehospitalization, revascularization and composite MACCEs rose significantly with elevated TyG index levels (all p < 0.05). Notably, after adjusting for age, BMI and other potential confounding factors, multivariate-adjusted hazard ratio (HR) also increased with rising TyG index levels for all-cause death, CV death, non-fatal MI, cardiac rehospitalization, revascularization and composite MACCEs (all p < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Competing risk regression curves for CV death, non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke, cardiac rehospitalization, revascularization and composite MACCEs of the TyG ≤ 8.91 group (Tertile 1, yellow line), the 8.91 < TyG < 9.54 group (Tertile 2, green line) and the TyG ≥ 9.54 group (Tertile 3, red line). TyG, triglyceride-glucose index; CV, cardiovascular; MI, myocardial infarction; MACCEs, major adverse cardiac and cerebral events

Table 3.

Competing risk model of MACCEs

| % (Events) | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | p value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cause death | |||||

| TyG ≤ 8.91 | 12.8% (83) | Ref | -/- | Ref | -/- |

| 8.91 < TyG < 9.54 | 15.8% (101) | 1.18 (0.86,1.58) | 0.255 | 1.67 (1.24,2.25) | 0.001 |

| TyG ≥ 9.54 | 16.7% (108) | 1.26 (0.95,1.68) | 0.112 | 2.35 (1.72,3.20) | < 0.001 |

| CV death | |||||

| TyG ≤ 8.91 | 9.3% (60) | Ref | -/- | Ref | -/- |

| 8.91 < TyG < 9.54 | 11.9% (76) | 1.24 (0.88,1.73) | 0.217 | 1.60 (1.11,2.30) | 0.012 |

| TyG ≥ 9.54 | 15.0% (97) | 1.60 (1.16,2.20) | 0.004 | 2.71 (1.92,3.83) | < 0.001 |

| Non-fatal MI | |||||

| TyG ≤ 8.91 | 5.9% (38) | Ref | -/- | Ref | -/- |

| 8.91 < TyG < 9.54 | 8.0% (51) | 1.29 (0.85,1.96) | 0.214 | 1.37 (0.90,2.10) | 0.143 |

| TyG ≥ 9.54 | 11.1% (72) | 1.93 (1.28,1.90) | 0.001 | 2.02 (1.32,3.11) | 0.001 |

| Non-fatal stroke | |||||

| TyG ≤ 8.91 | 3.9% (25) | Ref | -/- | Ref | -/- |

| 8.91 < TyG < 9.54 | 3.4% (22) | 0.94 (0.52,1.69) | 0.830 | 0.94 (0.50,1.78) | 0.859 |

| TyG ≥ 9.54 | 4.5% (29) | 1.20 (0.69,2.08) | 0.529 | 1.39 (0.73,2.63) | 0.315 |

| Cardiac rehospitalization | |||||

| TyG ≤ 8.91 | 11.3% (73) | Ref | -/- | Ref | -/- |

| 8.91 < TyG < 9.54 | 17.4% (111) | 1.51 (1.13,2.03) | 0.006 | 1.48 (1.10,2.01) | 0.011 |

| TyG ≥ 9.54 | 26.3% (170) | 2.46 (1.87,3.24) | < 0.001 | 2.42 (1.81,3.24) | < 0.001 |

| Revascularization | |||||

| TyG ≤ 8.91 | 6.5% (42) | Ref | -/- | Ref | -/- |

| 8.91 < TyG < 9.54 | 10.6% (68) | 1.58 (1.08,2.31) | 0.020 | 1.35 (0.90,2.02) | 0.142 |

| TyG ≥ 9.54 | 18.0% (116) | 2.83 (1.99,4.04) | < 0.001 | 2.41 (1.63,3.55) | < 0.001 |

| Composite MACCEs | |||||

| TyG ≤ 8.91 | 27.8% (180) | Ref | -/- | Ref | -/- |

| 8.91 < TyG < 9.54 | 37.2% (238) | 1.34 (1.10,1.64) | 0.004 | 1.58 (1.33,1.88) | < 0.001 |

| TyG ≥ 9.54 | 49.1% (317) | 2.03 (1.68,2.45) | < 0.001 | 2.32 (1.92,2.80) | < 0.001 |

Adjusted factors included TyG index, age, BMI, history of stroke and PCI, antiplatelet agent used before admission, WBC, hemoglobin, albumin, eGFR, LVEF, angiography findings (LM/three-disease and proximal LAD), in-hospital treatment(PCI/CABG, antiplatelet agent, ACEI/ARB, beta-blocker, statins) and hypoglycemic agents(Metformin, Alpha-glucosidase inhibitor, DPP-4i and insulin)

MACCEs, major adverse cardiac and cerebral events; TyG, triglyceride-glucose index; CV, cardiovascular; MI, myocardial infarction; BMI, body mass index; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; WBC,white blood cell; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LM, left main coronary artery; LAD, left anterior descending; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; ACEI/ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; DPP-4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; Ref, reference

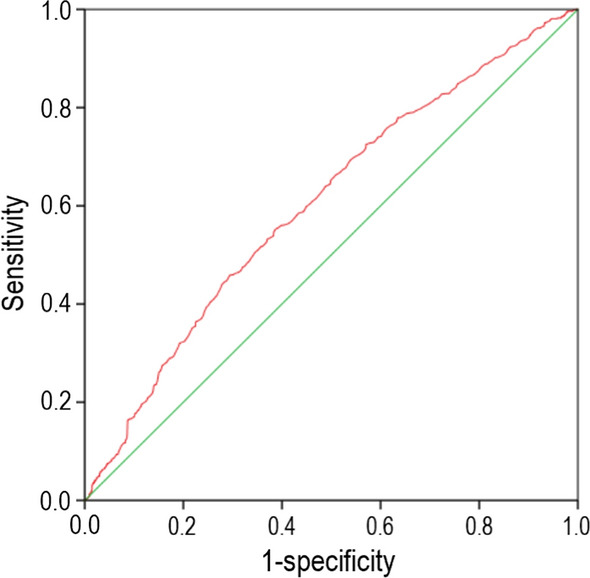

ROC curve analysis of the value of TyG index

The area under ROC curves (AUCs) of the TyG index for predicting the occurrence of MACCEs was 0.604 (95% CI 0.578–0.630; p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The cut-off value of TyG index to predict MACCEs was 9.30, the sensitivity was 0.552, and the specificity was 0.613.

Fig. 2.

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of the TyG index as a marker to predict composite MACCEs in patients with T2DM and AMI. The area under ROC curves (AUCs) of the TyG index for predicting the occurrence of MACCEs was 0.604 (95% CI 0.578–0.630; p < 0.001). The cut-off value of TyG index to predict MACCEs was 9.30, the sensitivity was 0.552, and the specificity was 0.613

Incremental effect of TyG index on predictive value for MACCEs

Table 4 showed that compared with the glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), FPG and TGs, the addition of TyG index significantly improved the reclassification and discrimination ability beyond the baseline risk model with NRI of 0.190 and IDI of 0.027 (both p < 0.001). In addition, the C-index of the baseline risk model [0.659 (0.638 to 0.681), p < 0.001] changed after addition of the TyG-index [0.685(0.663 to 0.707), p < 0.001].

Table 4.

Evaluate the incremental predictive value and predictive power of various models with NRI, IDI and C-index

| Category-free NRI | IDI | C-index | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index | 95% CI | p value | Index | 95% CI | p value | Index | 95% CI | p value | |

| Baseline risk model | Ref | Ref | 0.659 | 0.638 to 0.681 | < 0.001 | ||||

| + HbA1c | 0.032 | −0.063 to 0.094 | 0.228 | 0.005 | 0.000 to 0.013 | 0.084 | 0.661 | 0.638 to 0.683 | < 0.001 |

| + FPG | 0.095 | 0.015 to 0.150 | 0.020 | 0.007 | 0.001 to 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.664 | 0.641 to 0.686 | < 0.001 |

| + TGs | 0.111 | 0.030 to 0.164 | 0.020 | 0.010 | 0.007 to 0.020 | 0.012 | 0.676 | 0.654 to 0.697 | < 0.001 |

| + TyG index | 0.190 | 0.094 to 0.337 | < 0.001 | 0.027 | 0.013 to 0.041 | < 0.001 | 0.685 | 0.663 to 0.707 | < 0.001 |

Baseline risk model including age, history of stroke, beta-blocker used before admission, WBC, eGFR, LVEF, in-hospital treatment(PCI/CABG, antiplatelet agent, beta-blocker and statins) and hypoglycemic agents( insulin)

NRI, net reclassification improvement; IDI, integrated discrimination improvement; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; TGs, triglycerides; TyG, triglyceride-glucose index; WBC, white blood cell; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; Ref, reference

Independent association of TyG index with MACCEs in different subgroups

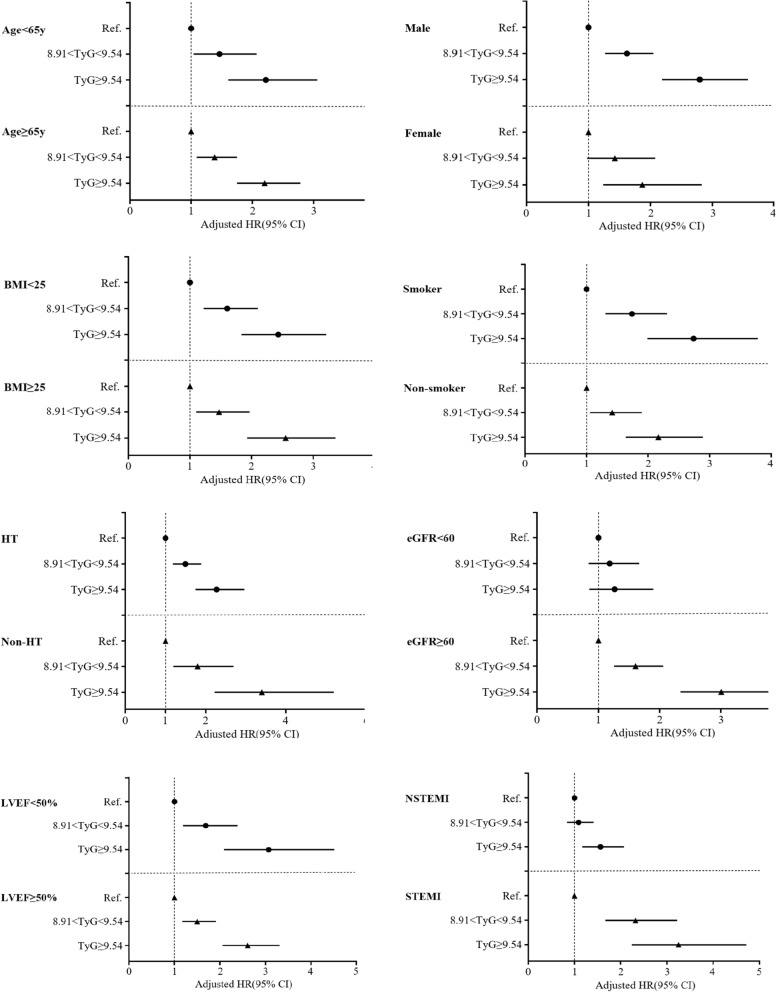

Subgroup analysis was performed according to age, sex, BMI, smoker, HT, eGFR, LVEF and AMI type (Fig. 3). We found that the predictive effect of TyG index on MACCEs is effective in most subgroups, except for patients with eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73m2.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of composite MACCEs according to different subgroups. Adjusted model included age, gender, BMI, SBP, DBP, previous MI, past PCI, history of stroke, current/ex-smoker, WBC, eGFR, albumin, TC, TGs, HDL-C, LDL-C, LVEF, hemoglobin, medication used before admission(antiplatelet agent, ACEI/ARB, beta-blocker and statins), in-hospital treatment(PCI/CABG, antiplatelet agent, ACEI/ARB, beta-blocker and statins) and hypoglycemic agents(metformin, alpha-glucosidase inhibitor, DPP-4i and insulin). MACCE, major adverse cardiac and cerebral events; TyG, triglyceride-glucose index; BMI, body mass index; HT, hypertension; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NSTEMI, Non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; WBC, white blood cell; TC, total cholesterol; TGs, triglycerides; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ACEI/ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; DPP-4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; Ref., reference(TyG ≤ 8.91 group)

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the association between the TyG index and MACCEs in AMI patients with T2DM. Our main findings include: (1) the incidences of MACCEs significantly increased with the increase of TyG index, and (2) the TyG index was an independent predictor of MACCEs(all-cause death, CV death, non-fatal MI, cardiac rehospitalization, revascularization and composite MACCEs, and (3) The AUC of the TyG index for predicting the occurrence of MACCEs was 0.604 with a cut-off value of 9.30, and (4) The addition of TyG index to a baseline risk model had an incremental effect on the predictive value for MACCEs, and (5) the predictive effect of TyG index on MACCEs is ineffective in patients with eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. According to this study, we confirmed that the TyG index was positively associated with increased MACCEs. Most importantly, this study suggested that a simple method of estimating IR may optimize the risk stratification of recurrent cardiovascular risk in AMI patients with T2DM.

IR is defined as a decrease in the efficiency of insulin in promoting glucose uptake and utilization, which is an indicator of abnormal metabolism. IR promotes the progression of CVDs by inducing glucose metabolism imbalance, altering systemic lipid metabolism, and causing endothelial dysfunction [11]. Several clinical studies found that IR was an important risk factor for CVDs and poor clinical outcomes [6, 28–30]. At present, the traditional methods of IR detection mainly include the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp and the HOMA-IR. However, due to the complexity and high cost of the detection process, the above two methods cannot be applied to clinical practice on a large scale. In order to solve this clinical problem, researchers have done a lot of studies on TyG index and found that it was a reliable surrogate marker of IR [12, 15]. Therefore, when the hyperinsulinaemic-euglycaemic clamp test and HOMA-IR cannot be measured, the TyG index be used to identify IR in clinical practice.

Researchers have done a lot of works to prove the predictive effect of TyG index on CVDs. Sánchez-Íñigo et al. suggested that a higher level of TyG index was significantly associated with an increased risk of developing CVDs independent of confounding factors, and the TyG index might be used to early identify the high-risk CVEs in healthy individuals [31]. Da Silva et al. demonstrated that the TyG index was positively associated with a higher prevalence of symptomatic coronary artery disease(CAD) in patients underwent secondary care for CVD [20]. Mao et al. firstly confirmed that the TyG index was positively associated with SYNTAX score and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS) population [22]. Additionally, a cohort study including 1092 STEMI patients who underwent PCI indicated that the incidences of composite MACCEs and all-cause death within 30 days, 6 months and 1 year were higher among those with highest level of TyG index (TyG index ≥ 9.608), and that the TyG index ≥ 9.608 was independently associated with an increased risk of MACCEs within 1 year [HR(95% CI) 1.53 (1.0 1, 2.06), p = 0 003] [21]. Considering that nearly one-third of ACS patients are combined with T2DM, and these patients are characterized by more complex coronary lesions, higher incidence of recurrent CVEs, and worse prognosis. Relevant studies about the TyG index in predicting CVEs in patients with ACS complicated with T2DM have been published in succession. Wang et al. followed up 2,531 ACS patients with T2DM for 3 years and found that the incidence of MACEs increased with the increase of TyG index, the TyG index was an independent predictor of MACEs, and the optimal TyG index cut-off for predicting MACEs was 9.323 [24]. A study by Ma et al. of 776 patients with T2DM and ACS who underwent PCI also showed that the TyG index was significantly associated with adverse CV outcomes, including all-cause mortality, non-fatal stroke, non-fatal MI and unplanned repeat revascularization [23]. In addition, a study including 798 patients with T2DM and NSTE-ACS undergoing PCI reported that 1-unit increase of TyG index was independently associated with higher risk of primary endpoint (a composite of all-cause death, non-fatal MI and ischemia-driven revascularization)[HR: 3.208 per 1-unit increase, 95% Cl 2.40–4.29, p < 0.001], and the addition of TyG index to a baseline risk model had an incremental effect on the predictive value for adverse prognosis [AUC: baseline risk model, 0.800 vs. baseline risk model + TyG index, 0.856, p < 0.001] [25]. However, the predictive effects of the TyG index on MACCEs in patients with AMI combined with T2DM, are still unclear.

In this study, we investigated the prognostic value of the TyG index in patients with AMI combined with T2DM for the first time. To better understand the predictive power of TyG index for different CVEs, we analyzed the correlation between TyG index and each type of MACCEs (including all-cause death, CV death, non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke, revascularization, and cardiac rehospitalization), which other studies have not tried. The conclusions drawn by this research have important guiding role for clinicians to predict the occurrence of future clinical events in patients with AMI and T2DM. In addition, we also found that adding TyG index to the baseline risk model had a significantly incremental effect on the predictive value for MACCEs, which is consistent with the conclusions of Zhao et al. [25]. Another novelty of this research is that we have done the predictive value of TyG index on MACCEs in different subgroups, including age, sex, BMI, smoker, HT, eGFR, LVEF and AMI type. We found that TyG index has a good predictive effect on MACCEs in most subgroups, except for patients with eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. For this result, the mechanism is still unclear. There are relatively few studies on TyG index and kidney disease. Zhao et al. [32] found that an elevated TyG index was associated with a higher risk of nephric microvascular damage. Zhu et al. [33] showed that an elevated TyG index is signifcantly associated with HT in the subgroup of the lower eGFR(< 90 ml/min/1.73 m2). Maybe we need to do some work on that.

Our study had several limitations. First, this was a single-center study although including a large sample size; thus, generalization of the findings should be cautious. Second, laboratory parameters were only measured once after hospital admission, which could cause potential bias due to measurement error. Third, conventional laboratory testing methods for IR, such as HOMA-IR, has not been tested, the relationship between TyG index and IR cannot be verified directly in this study. In addition, prospective cohort studies are required to confirm our findings.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the current study firstly demonstrated that elevated TyG index level was a strong independent predictor of MACCEs in patients with AMI and T2DM. In addition, adding the TyG index to a baseline risk model had an incremental effect on the predictive value for MACCEs.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of all staffs who work on the CBD Bank.

Abbreviations

- TyG

Triglyceride-glucose

- AMI

Acute myocardial infarction

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- MACCEs

Major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events

- IR

Insulin resistance

- CV

Cardiovascular

- CVDs

Cardiovascular diseases

- CVEs

Cardiovascular events

- TGs

Triglycerides

- FPG

Fasting plasma glucose

- HOMA-IR

The homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

- CBD

Cardiovascular Center of Beijing Friendship Hospital Database

- eGFR

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- CABG

Coronary artery bypass graft

- SPISE

The Single Point Insulin Sensitivity Estimator

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- BMI

Body mass index

- RBG

Random blood glucose

- OGTT

Oral glucose tolerance test

- HT

Hypertension

- TC

Total cholesterol

- LDL-C

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- NSTEMI

Non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- STEMI

ST-elevation myocardial infarction

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- NRI

Net reclassification improvement

- IDI

Integrated discrimination improvement

- Hs-CRP

Hypersensitive C-reactive protein

- PCI

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- LVEF

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- LM

Left main coronary artery

- LAD

Left anterior descending

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- WBC

White blood cell

- ACEI/ARB

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker

- HR

Hazard ratio

- HbA1c

Glycated hemoglobin

- CAD

Coronary artery disease

- MACEs

Major adverse cardiovascular events

- NSTE-ACS

Non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome

Authors’ contributions

YZ performed study, statistical analysis and wrote manuscript. XD, BH, QL and HG participated in study data collection. HC contributed discussion and edited manuscript. XQZ revised manuscript. WL designed study and performed statistical analysis. HL provided funding support, designed study and reviewed manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81670315) and Beijing Key Clinical Subject Program.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study data collections were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Friendship Hospital affiliated to Capital Medical University, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, et al. Heart disease and strokestatistics-2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(12):e67–492. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The World Bank. Toward a healthy and harmonious life in China: stemming the rising tide of non-communicable diseases. http://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/NCD_report_en.pdf.

- 3.Zhou M, Liu J, Hao Y, Liu J, Huo Y, Smith SC, et al. Prevalence and in-hospital outcomes of diabetes among patients withacute coronary syndrome in China: findings from the Improving Carefor Cardiovascular Disease in China-Acute Coronary Syndrome Project. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):147. doi: 10.1186/s12933-018-0793-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ray KK, Colhoun HM, Szarek M, Baccara-Dinet M, Bhatt DL, Bittner VA, et al. Effects of alirocumab on cardiovascular and metabolic outcomes after acute coronary syndrome in patients with or without diabetes: a prespecified analysis of the ODYSSEY OUTCOMES randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(8):618–628. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauters C, Lemesle G, de Groote P, Lamblin N. A systematic review and meta-regression of temporal trends in the excess mortality associated with diabetes mellitus after myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2016;217:109–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.04.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laakso M, Kuusisto J. Insulin resistance and hyperglycaemia in cardiovascular disease development. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10(5):293–302. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eddy D, Schlessinger L, Kahn R, Peskin B, Schiebinger R. Relationship of insulin resistance and related metabolic variables to coronary artery disease: a mathematical analysis. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(2):361–366. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caccamo G, Bonura F, Vitale G, Novo G, Evola S, Evola G, et al. Insulin resistance and acute coronary syndrome. Atherosclerosis. 2010;211(2):672–675. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeFronzo RA, Tobin JD, Andres R. Glucose clamp technique:a method for quantifying insulin secretion and resistance. Am J Physiol. 1979;237:e214–e223. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1979.237.3.E214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muniyappa R, Lee S, Chen H, Quon MJ. Current approaches for assessing insulin sensitivity and resistance in vivo: advantages, limitations, and appropriate usage. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metabol. 2008;294(1):e15–26. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00645.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ormazabal V, Nair S, Elfeky O, Aguayo C, Salomon C, Zuñiga FA. Association between insulin resistance and the development of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17:122. doi: 10.1186/s12933-018-0762-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guerrero-Romero F, Simental-Mendia LE, Gonzalez-Ortiz M, Martínez-Abundis E, Ramos-Zavala MG, Hernández-González SO, et al. The product of triglycerides and glucose, a simple measure of insulin sensitivity. Comparison with the euglycemichyperinsulinemic clamp. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:3347–3351. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vasques AC, Novaes FS, de Oliveira MS, Souza JR, Yamanaka A, Pareja JC, et al. TyG index performs better thanHOMA in a Brazilian population: a hyperglycemic clamp validated study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;93(3):e98–100. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du TT, Yuan G, Zhang MX, Zhou X, Sun X, Yu X. Clinical usefulness of lipid ratios, visceral adiposity indicators, and the triglycerides and glucose index as risk markers of insulin resistance. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;13:146. doi: 10.1186/s12933-014-0146-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bastard JP, Lavoie ME, Messier V, Prud'homme D, Rabasa-Lhoret R. Evaluation of two new surrogate indices including parameters not using insulin to assess insulin sensitivity/resistance in non-diabetic postmenopausal women: a MONET group study. Diabetes Metab. 2012;38:258–263. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park K, Ahn CW, Lee SB, Kang S, Nam JS, Lee BK, et al. Elevated TyG index predicts progression of coronary artery calcification. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:1569–1573. doi: 10.2337/dc18-1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SB, Ahn CW, Lee BK, Kang S, Nam JS, You JH, et al. Association between triglyceride glucose index and arterial stiffness in Korean adults. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17:41. doi: 10.1186/s12933-018-0692-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Irace C, Carallo C, Scavelli FB, De Franceschi MS, Esposito T, Tripolino C, et al. Markers of insulin resistance and carotid atherosclerosis. A comparison of the homeostasis model assessment and triglyceride glucose index. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(7):665–672. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee EY, Yang HK, Lee J, Kang B, Yang Y, Lee SH, et al. Triglyceride glucose index, a marker of insulin resistance, is associated with coronary artery stenosis in asymptomatic subjects with type 2 diabetes. Lipids Health Dis. 2016;15:155. doi: 10.1186/s12944-016-0324-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.da Silva A, Caldas APS, Hermsdorff HHM, Bersch-Ferreira ÂC, Torreglosa CR, Weber B, et al. Triglyceride-glucose index is associated with symptomatic coronary artery disease in patients in secondary care. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18:89. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0893-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo E, Wang D, Yan GL, Qiao Y, Liu B, Hou JT, et al. High triglyceride-glucose index is associated with poor prognosis in patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18:150. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0957-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mao Q, Zhou DL, Li YM, Wang YQ, Xu SC, Zhao XH. The triglyceride-glucose index predicts coronary artery disease severity and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Dis Markers. 2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/6891537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma X, Dong L, Shao Q, Cheng Y, Lv S, Sun Y, et al. Triglyceride glucose index for predictingcardiovascular outcomes after percutaneouscoronary intervention in patients with type 2diabetes mellitus and acute coronary syndrome. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19:31. doi: 10.1186/s12933-020-01006-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang L, Cong H, Zhang J, Hu Y, Wei A, Zhang Y, et al. Triglyceride-glucose index predicts adverse cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes and acute coronary syndrome. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19:80. doi: 10.1186/s12933-020-01054-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao Q, Zhang T, Cheng Y, Ma Y, Xu Y, Yang J, et al. Impacts of triglyceride-glucose index on prognosis of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: results from an observational cohort study in China. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19:108. doi: 10.1186/s12933-020-01086-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paulmichl K, Hatunic M, Højlund K, Jotic A, Krebs M, Mitrakou A, et al. Modification and validation of the triglyceride-to-HDL cholesterol ratio as a surrogate of insulin sensitivity in white juveniles and adults without diabetes mellitus: the single point insulin sensitivity estimator (SPISE) Clin Chem. 2016;62:1211–1219. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2016.257436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Provisional report of a WHO Consultation. Diabetic Med. 1998;15(7):539–553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reaven G. Insulin resistance and coronary heart disease in nondiabetic individuals. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(8):1754–1759. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.241885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bloomgarden ZT. Insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(8):2164–2170. doi: 10.2337/dc07-zb08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rutter MK, Meigs JB, Sullivan LM, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Wilson PW. Insulin resistance, the metabolic syndrome, and incident cardiovascular events in the Framingham Offspring Study. Diabetes. 2005;54(11):3252–3257. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.11.3252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sánchez-Íñigo L, Navarro-González D, Fernández-Montero A, Pastrana-Delgado J, Martínez JA. The TyG index may predict the development ofcardiovascular events. Eur J Clin Invest. 2016;46(2):189–197. doi: 10.1111/eci.12583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao S, Yu S, Chi C, Fan X, Tang J, Ji H, Teliewubai J, Zhang Y, Xu Y. Association between macro-and microvascular damage and the triglyceride glucose index in community-dwelling elderly individuals: the Northern Shanghai Study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18:95. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0898-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu B, Wang J, Chen K, Yan W, Wang A, Wang W, Gao Z, Tang X, Yan L, Wan Q, Luo Z. A high triglyceride glucose index is more closely associatedwith hypertensionthan lipid or glycemic parameters in elderly individuals: a cross-sectional survey from the Reaction Study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19:112. doi: 10.1186/s12933-020-01077-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.