Abstract

Background

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) play important roles in essential biological processes. However, our understanding of lncRNAs as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) and their responses to nitrogen stress is still limited.

Results

Here, we surveyed the lncRNAs and miRNAs in maize inbred line P178 leaves and roots at the seedling stage under high-nitrogen (HN) and low-nitrogen (LN) conditions using lncRNA-Seq and small RNA-Seq. A total of 894 differentially expressed lncRNAs and 38 different miRNAs were identified. Co-expression analysis found that two lncRNAs and four lncRNA-targets could competitively combine with ZmmiR159 and ZmmiR164, respectively. To dissect the genetic regulatory by which lncRNAs might enable adaptation to limited nitrogen availability, an association mapping panel containing a high-density single–nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array (56,110 SNPs) combined with variable LN tolerant-related phenotypes obtained from hydroponics was used for a genome-wide association study (GWAS). By combining GWAS and RNA-Seq, 170 differently expressed lncRNAs within the range of significant markers were screened. Moreover, 40 consistently LN-responsive genes including those involved in glutamine biosynthesis and nitrogen acquisition in root were identified. Transient expression assays in Nicotiana benthamiana demonstrated that LNC_002923 could inhabit ZmmiR159-guided cleavage of Zm00001d015521.

Conclusions

These lncRNAs containing trait-associated significant SNPs could consider to be related to root development and nutrient utilization. Taken together, the results of our study can provide new insights into the potential regulatory roles of lncRNAs in response to LN stress, and give valuable information for further screening of candidates as well as the improvement of maize resistance to LN stress.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-021-02847-4.

Keywords: Maize, Nitrogen use efficiency, RNA-Seq, Genome-wide association study, LncRNA, Co-expression

Background

Presently, maize (Zea mays L.) serves as the major cultivated crop for human consumption and animal feed globally. Nitrogen (N) is an important plant macronutrient and improving N uptake is a key option for increasing crop yield [1]. Nitrate (NO3) and ammonium (NH4) are the main inorganic nitrogen sources that plant roots take up and assimilate in aerobic soil and flooded soil conditions, respectively [2]. Almost all soils are deficient in N, which directly leads to excessive application of N fertilizer. Therefore, it is more important to reduce the costs of agriculture and its impact on the environment. Recently, researchers found that growth-regulating factor 4 (GRF4) and growth-repressing DELLA proteins act in equilibrium in the regulation of growth and nitrogen metabolism in plants [3], which should help us understand the nitrogen metabolism of plants and contribute to sustainable development of global safe food supply.

Plant nitrate transport proteins include low-nitrate-affinity transporters such as most members of the NRT1 family [4], which are crucial transporters for nitrate uptake and nitrate transportation among cells, tissues, and organs. Meanwhile, high-nitrate-affinity transporter NRT2 families such as Arabidopsis thaliana NRT2.5 (AtNRT2.5) [5] are responsible for assimilating nitrate at relatively low concentration ranges. Other nitrate transporters, the chloride channel (CLC) family [6] can mediate nitrate accumulation and transport. Among these protein families, such as Arabidopsis thaliana NRT1.1 (AtNRT1.1) [7], which play dual roles as NO3− receptors and transporters. Ammonium transporters are mainly located at the plasma membrane. They are responsible for hydrophobic NH3 transport and ammonium distribution, such as Arabidopsis thaliana AMT1.1 (AtAMT1.1) [8].

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are generally defined as transcripts that cannot encode proteins and have a sequence length ranging from 200 nt to 100 kb. LncRNAs usually regulate adjacent target genes in cis, and regulate distant target genes in trans [9]. Hence, the positions of lncRNAs are helpful when speculating on their functions. The ceRNA hypothesis, which includes mRNAs, transcribed pseudogenes, and lncRNAs, describes that they can communicate with each other by sharing the same microRNA response elements (MREs) and that RNAs influence each other’s expression through competing miRNAs [10]. For example, the ceRNA linc-RoR was shown to share the same miRNA with core transcription factors (TFs) and prevent these core TFs from miRNA-mediated suppression in self-renewing human embryonic stem cells [11]. Moreover, in maize, the highly abundant Pi-deficiency-induced long-noncoding RNA1 (PILINCR1) could efficiently impair the miR399-guided cleavage of PHOSPHATE2 (PHO2) to regulate PHO2 level and reduce the tolerance to low Pi [12]. In rice, the potential ceRNA network comprising 376 and 511 lincRNAs of shoot and root, respectively, was identified from RNA-seq data, indicating the systematic regulation of lincRNA function under low Pi stress [13].

Upon completion of the reference genome sequencing of maize inbred line B73, the discovery of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertion-deletion polymorphisms lay a foundation for locating QTLs associated with maize agricultural characteristics and exploring candidate genes [14, 15]. Genome-wide association study (GWAS) is based on linkage disequilibrium (LD) to discover the relationship between objective traits and genetic markers in groups [16]. Maize lines presenting natural variation in different parts of the world were studied using GWAS to find the gene ZmNAC111, which encodes the transcription factor NAC located on chromosome 10 that plays an important role in maize seedling drought tolerance [17], and 384 maize inbred lines were genotyped with 681,257 SNPs and 22 seedling root architecture traits were applied to identify candidate genes contributing to root development at the seedling stage [18]. In double-haploid maize, a total of 54 SNPs were also identified to be significantly associated with resistance to maize chlorotic mottle virus and lethal necrosis [19]. Furthermore, by combining metabolite profiles and GWAS, five low-Pi-responding consensus genes associated with morphological traits and simultaneously involved in metabolic pathways were mined [20].

Previous researches generally focused on revealing coding genes regulated by nitrogen; in contrast, noncoding components such as lncRNAs induced by nitrogen deficiency have received little attention. In the present study, high-throughput sequencing was thus applied to analyze the expression profiles of lncRNAs, mRNAs, and miRNAs at the maize seedling stage under HN and LN conditions. The target genes of potential lncRNAs and miRNA–lncRNA pairs were predicted. We also determined the functions of lncRNAs in the co-expression network based on the “ceRNA hypothesis.” Transient expression assays in Nicotiana benthamiana demonstrated that LNC_002923 could inhibit the cleavage of Zm00001d015521 by ZmmiR159. One hundred and seventy lncRNAs containing significant root trait-associated SNPs were identified. Moreover, a total of 40 consistently LN–responsive candidate genes were screened through combining GWAS and RNA-Seq. Together, our results provide multiple insights to understand the LN–responsive mechanisms of lncRNAs in maize seedlings and offer new ideas for improving nitrogen use efficiency in maize.

Results

High-throughput sequencing of lncRNA and small RNA libraries

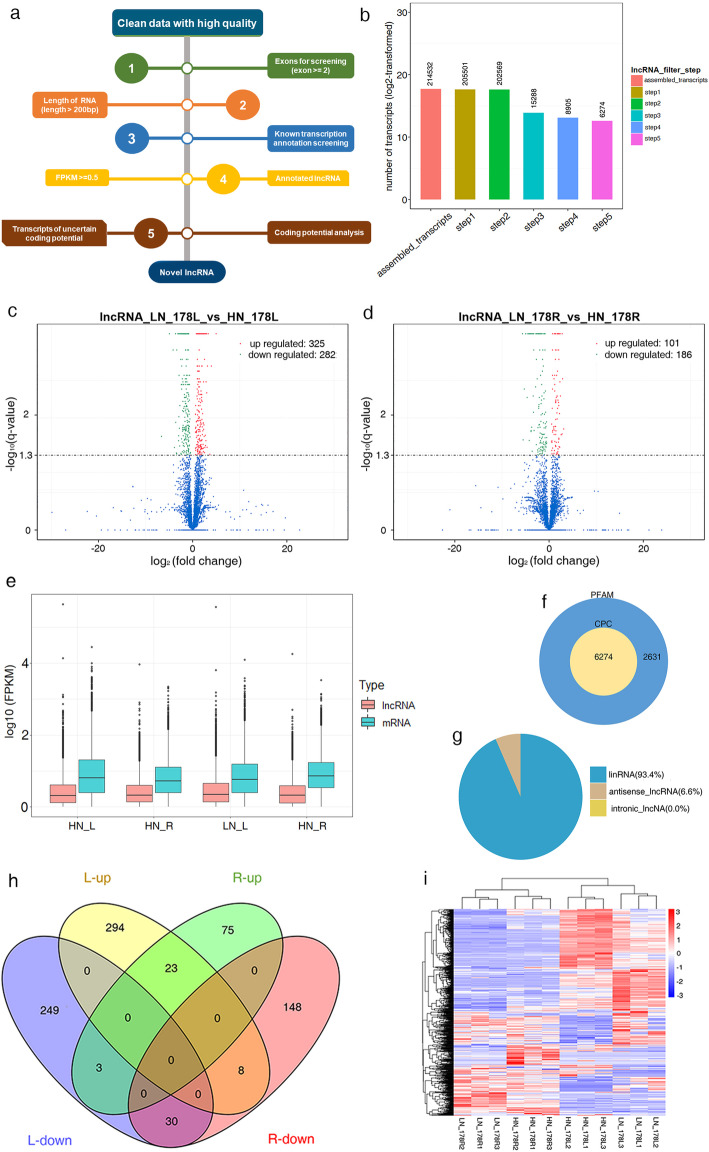

In total, 1,241,588,130 and 168,839,937 raw reads were generated from the libraries of lncRNAs and small RNAs, respectively. After the removal of low–quality reads and trim adapters, we obtained approximately 1,175,852,744 and 165,272,934 clean reads from the lncRNA and small RNA libraries. Then, we mapped the clean reads for each sample to the maize genome (B73 RefGen_V4) and used them for further analysis (Table 1). For mRNAs, a total of 214,532 transcripts were reconstructed from all of the 12 RNA-seq datasets, and 8836 differentially expressed genes were identified in leaves and roots (Fig. S1a, b). For lncRNAs, we based our analysis on the results of transcript splicing and following the structural characteristics and noncoding proteins, setting up a series of strict screening conditions (Fig. 1a). A total of 6274 transcripts were applied to the analysis of differential expression (Fig. 1b). We obtained 894 reliably expressed lncRNAs in leaves and roots (Fig. 1c, d). For miRNAs, the length distribution (range 18–30 nt) of total small RNAs was generated from clean reads (Fig. S2a). The transcripts per million (TPM) of miRNA is shown in Fig. S2b. Then, the screened sRNAs were used to analyze the distribution on the reference sequence and identify known and novel miRNAs. A total of 184 known miRNAs and 106 novel miRNAs were found in leaves and roots (Table S1). The analysis of differential mRNAs and miRNAs expression patterns under HN and LN conditions are presented in Fig. S3.

Table 1.

Overview of high-throughput sequencing datasets

| Sample | Raw reads (mRNA) |

Clean reads (mRNA) |

Mapped mRNA | Raw reads (sRNA) |

Clean reads (sRNA) |

Total sRNA | Mapped sRNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HN_178L1 | 109,909,236 | 103,469,546 | 87,028,986 (84.11%) | 13,280,860 | 12,997,834 | 10,034,480 | 9,092,731 (90.61%) |

| HN_178L2 | 98,882,294 | 92,738,214 | 77,601,590 (83.68%) | 13,386,049 | 13,013,518 | 11,416,614 | 10,586,874 (92.73%) |

| HN_178L3 | 112,394,988 | 107,414,484 | 91,656,287 (85.33%) | 14,543,122 | 14,230,805 | 11,286,848 | 10,204,716 (90.41%) |

| HN_178R1 | 107,762,888 | 103,079,810 | 66,664,905 (64.67%) | 14,487,323 | 14,182,798 | 10,576,881 | 3,754,075 (35.49%) |

| HN_178R2 | 113,741,976 | 107,492,062 | 69,938,707 (65.06%) | 12,788,134 | 12,544,973 | 9,729,248 | 3,298,959 (33.91%) |

| HN_178R3 | 112,270,478 | 105,413,706 | 69,146,376 (65.6%) | 14,253,769 | 13,962,951 | 9,719,839 | 3,346,704 (34.43%) |

| LN_178L1 | 112,309,946 | 107,045,930 | 91,314,837 (85.3%) | 14,953,702 | 14,688,124 | 12,241,826 | 11,194,567 (91.45%) |

| LN_178L2 | 86,345,420 | 81,918,980 | 70,017,448 (85.47%) | 14,796,171 | 14,527,123 | 8,584,463 | 7,808,736 (90.96%) |

| LN_178L3 | 89,499,196 | 85,098,370 | 72,826,546 (85.58%) | 13,941,202 | 13,607,151 | 10,073,249 | 9,268,334 (92.01%) |

| LN_178R1 | 87,421,586 | 81,198,490 | 56,714,397 (69.85%) | 13,320,127 | 13,046,233 | 9,657,102 | 5,046,601 (52.26%) |

| LN_178R2 | 103,512,304 | 99,661,226 | 68,242,687 (68.47%) | 14,165,435 | 13,850,479 | 10,900,885 | 5,754,381 (52.79%) |

| LN_178R3 | 107,537,818 | 101,322,926 | 71,234,057 (70.3%) | 14,924,043 | 14,620,945 | 10,581,227 | 5,504,041 (52.02%) |

Fig. 1.

The pipeline used for the identification of lncRNA (a). Setting up 5 steps to filter assembled transcripts (b). The volcano plot of differential expressed lncRNAs between two nitrogen conditions in leaf (c) and (d) root. The expression values of lncRNAs and mRNAs were calculated based on the RNA-Seq results, respectively (e). LncRNA classification (f) and lncRNA coding potential predicted by protein family database (Pfam) and Coding Potential Calculator (CPC) (g). Differentially expressed lncRNAs between leaves and roots (h). Expression profiles of lncRNA during seedling under HN and LN conditions (i). HN, hign nitrogen. LN, low nitrogen. L, leaf. R, root

Genome-wide identification of lncRNAs

In maize seedlings, the lncRNAs ranged in length from 201 base pairs (bp) to approximately 29,176 bp, with a mean length of 829 bp and distributed on each chromosome. The lncRNAs showed lower FPKM than the mRNAs (Fig. 1e). Of these lncRNAs, 93.4% were lincRNAs and 6.6% were antisense lncRNAs (Fig. 1f). Their coding potential was also predicted by PFAM and CPC (Fig. 1g). To identify the lncRNAs involved in responses to nitrogen stress, we selected lncRNAs with a q-value< 0.05 between the HN and LN groups as being differentially expressed. Overall, 607 and 287 differential lncRNAs were genome-widely screened from leaves and roots (Fig. 1c, d), respectively, of which 23 were consistently upregulated and 30 were consistently downregulated in both roots and leaves (Fig. 1h). This suggested that these lncRNAs perform similar functions in different tissues in response to LN stress. The clustering analysis of different lncRNAs was applied to determine the cluster model under HN and LN conditions (Fig. 1i); it showed upregulated and downregulated lncRNAs in the two tissues. Besides, 477 differentially expressed transcripts of uncertain coding potential (TUCPs) potentially containing a subset of lncRNAs with certain coding potential were identified (Fig. S1c, d). The characteristics of identified lncRNAs are shown in Fig. S4. In these results, we obtained a majority of lincRNAs and antisense lncRNAs, and a low proportion of TUCPs, which indicated that the RNA-Seq strategy can be used for these RNAs.

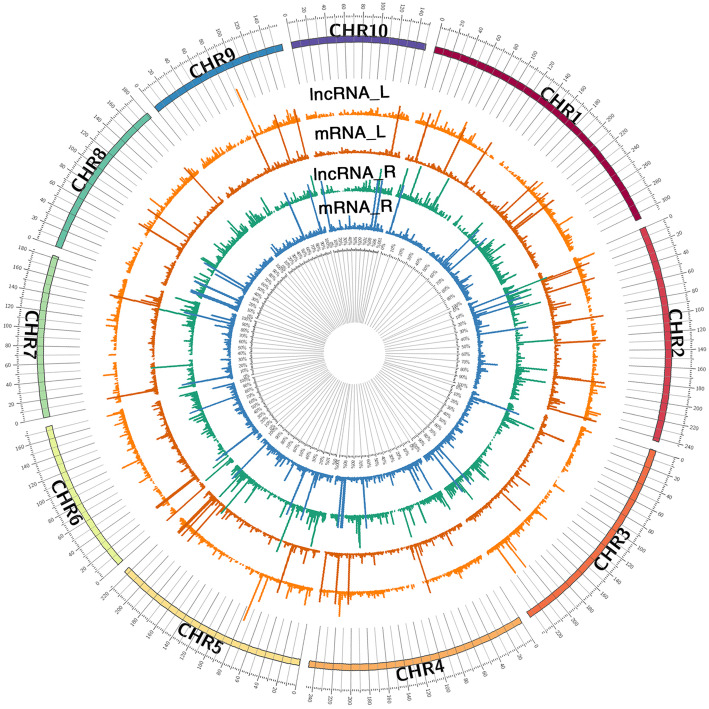

The expressional level mRNA distribution from the 12 libraries is shown along 10 chromosomes (Fig. 2). To understand the potential interaction between lncRNAs and coding transcripts, we identified the adjacent genes within 100 kb either up and downstream from the lncRNAs (Table S2). We also used Pearson’s correlation coefficient to analyze the correlation of expression level between lncRNAs and genes; those with a correlation value greater than 0.95 were taken for analysis (Table S2). The target analysis of co-location and co-expression provides an approach to predict the main functions of lncRNAs.

Fig. 2.

The distribution of lncRNAs and mRNAs on 10 chromosomes. The abundance level of lncRNAs and mRNAs (log10 (fold change)) on each chromosome in leaves and roots

Validation of lncRNA, lncRNA target, and miRNA expression using qRT-PCR

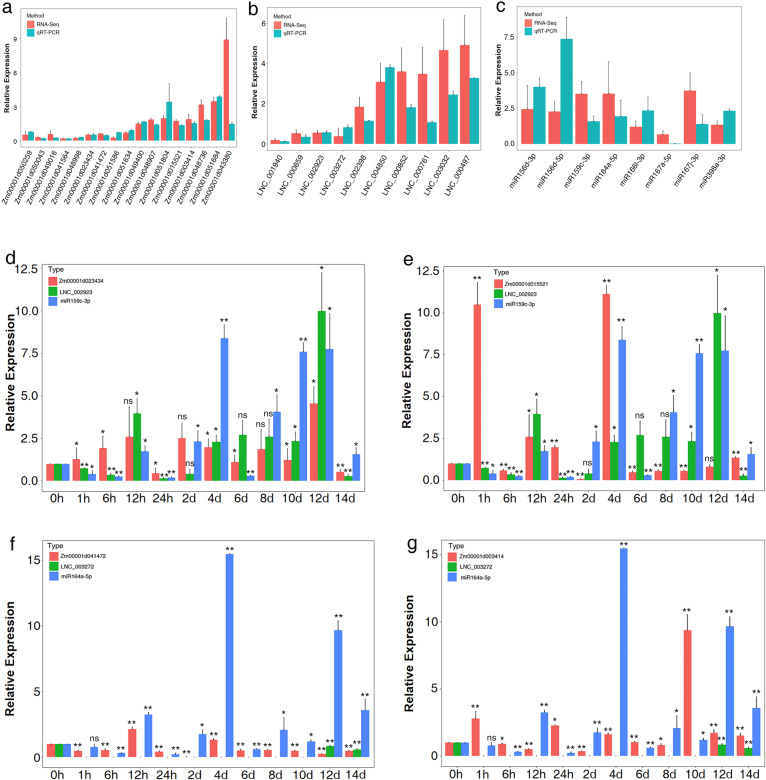

To confirm the reliability of the deep sequencing results, 17 mRNAs, 10 lncRNAs, and 8 miRNAs were randomly selected for qRT-PCR analysis. As shown in Fig. 3a–c, the qRT-PCR, and RNA-seq data showed the same tendency, indicating the reliability of the RNA-seq results.

Fig. 3.

qRT-PCR was performed to validate the differentially expressed mRNAs (a), lncRNAs (b) and miRNAs (c) identified by the RNA-seq results. There was no significant difference between RNA-Seq and qRT-PCR. qRT-PCR was performed to analysis the dynamic response of lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA expression levels to LN stress at different treatment stages.*, significant at P < 0.05. **, significant at P < 0.01. ns, not significant were relative to 0 h

Analysis of the co-expression network

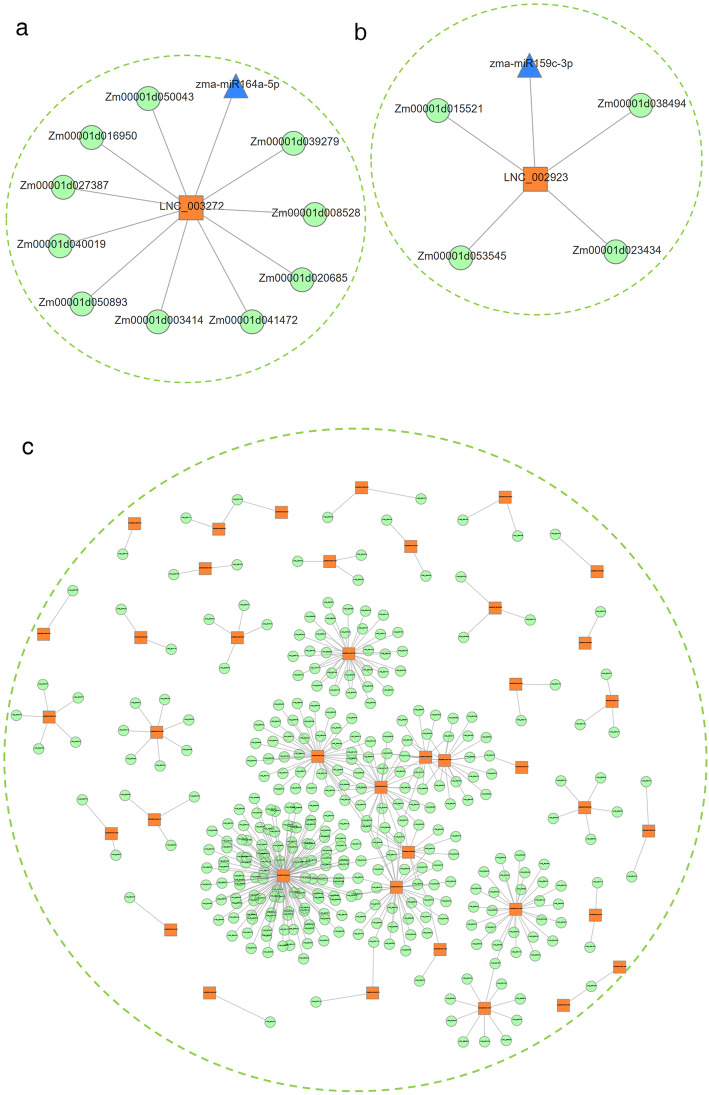

A total of 38 differentially expressed miRNAs identified from 12 small RNA libraries (Fig. S1e, f) were utilized for analyses of their interactions with lncRNAs and mRNAs. And then, we constructed the co-expression network that lncRNA–gene pairs generally share the same miRNA binding sites [10]. As shown in Fig. 4a, b, 2 lncRNAs, 2 miRNAs, and 14 mRNAs were included in the two co-expression networks, and the lncRNAs served as ceRNAs to communicate with many mRNAs through competing with specific miRNAs. These results contributed to our understanding the potential functions of lncRNAs in maize seedling under LN stress, and revealed the mechanism of lncRNAs regulated gene expression at the whole transcriptome.

Fig. 4.

The lncRNA-gene pairs which shared same miRNA binding sites with miRNA, root- (a) and leaf- (b) special co-expression networks. The 40 consistently candidate genes were influenced by lncRNAs in cis and trans (c). Green nodes represent lncRNAs, orange nodes represent mRNAs and blue triangles represent miRNAs

We then analyzed the dynamic responses of lncRNA–miRNA–mRNA expression levels to LN stress at different treatment stages. For the co-expression network in the leaf, LNC_002923, miR159c, and two mRNAs were selected for qRT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 3d, e, the expression profile of Zm00001d023434 was similar to LNC_002923, but opposite of miR159c. Furthermore, Zm00001d015521 in the lncRNA-associated co-expression network showed the opposite expression pattern to LNC_002923, but a similar one to miR159c at 14 days. In general, the level of Zm00001d023434 was upregulated under the nitrogen starvation of seedling leaves, except for at 24 h and 14 days. Zm00001d015521 was almost completely suppressed at most stages, except for 1 h, 12 h, 24 h, and 4 days. The level of miR159c was upregulated in leaf at most treatment stages, only showed downregulation at 1 h, 6 h, 24 h, and 6 days. The level of LNC_002923 was almost always downregulated in the short–term, but was upregulated in the long–term. For the co-expression network in the root, the expression of LNC_003272, miR164a, and two mRNAs is shown in Fig. 3f, g. The expression of LNC_003272 was hardly detected, only showing downregulation at 12 and 14 days. The levels of miR164a and mRNAs showed the opposite expression pattern at 14 days after LN stress. Overall, the expression profiles of nitrogen-responsive lncRNAs, miRNAs, and mRNAs match better at a later stage than other short–term treatment for the “ceRNA hypothesis”, suggesting that ceRNA mechanisms are vital for further studying lncRNA functions under LN condition in maize.

Targets analysis of LN-responsive lncRNAs

To detect the cis-acting lncRNAs function, we screened 100 kb upstream and downstream of the 607 and 287 differentially expressed lncRNAs in leaves and roots, respectively, and performed lncRNA-mRNA pairs expression correlation analysis. In total, 2561 and 1142 lncRNA-mRNA pairs for differentially expressed lncRNAs in leavesand roots were found, respectively (Table S3). GO analysis predicted some differential genes in the following subcategories within the main category of the biological process: nitrogen compound metabolic process, response to oxidative stress, and chromatin remodeling. Besides, there were also enriched GO terms such as nitrogen compound transport, organ nitrogen compound biosynthetic process, nitrate metabolic process, and regulation of external response (Table S5).

On the other hand, to detect the effect of trans-acting lncRNAs on genes expression regulation in diverse biological processes. According to the expression correlation between lncRNAs and mRNAs (Pearson correlation> 0.95), 59,577 and 22,227 co-expression relationships of lncRNAs and LN-responsive genes were found in leaf and root, respectively (Table S4). GO categories and subcategories were analyzed, the results predicted that most of these genes were organic substance biosynthetic, alpha-amino acid metabolic, and photosynthetic membrane in leaf and root.

We next analyzed the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis with differentially expressed genes, and the top20 enriched pathways are presented in (Table S6). The results showed the trans-acting lncRNAs were enriched in several pathways associated with cysteine and methionine metabolism, cyanamino acid metabolism. Meanwhile, some enriched pathways associated with nitrogen metabolism, alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism were identified. In cis-acting, the results of these genes function in the chlorophyll metabolism, biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, as well as carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms. These enriched biological processes and pathways are related to glutamine family amino acid biosynthetic process and abiotic stress, indicating that the differentially expressed LN-responsive lncRNAs play important roles in the absorption and transportation of nitrogen during maize development.

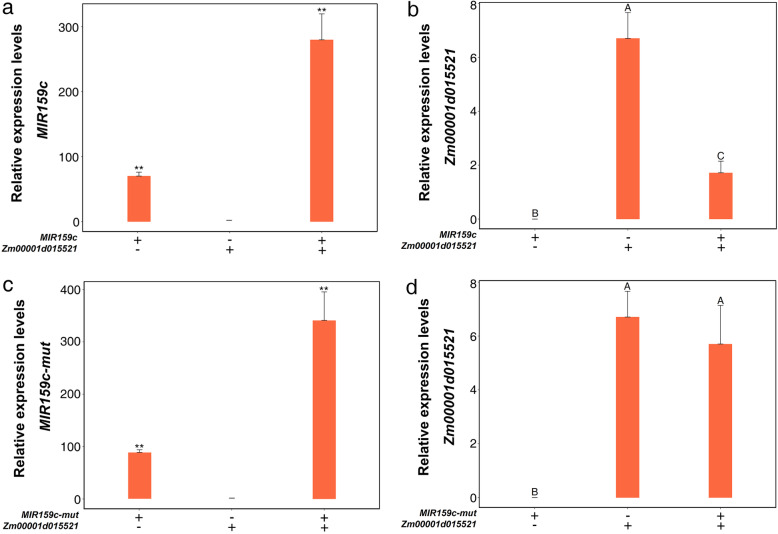

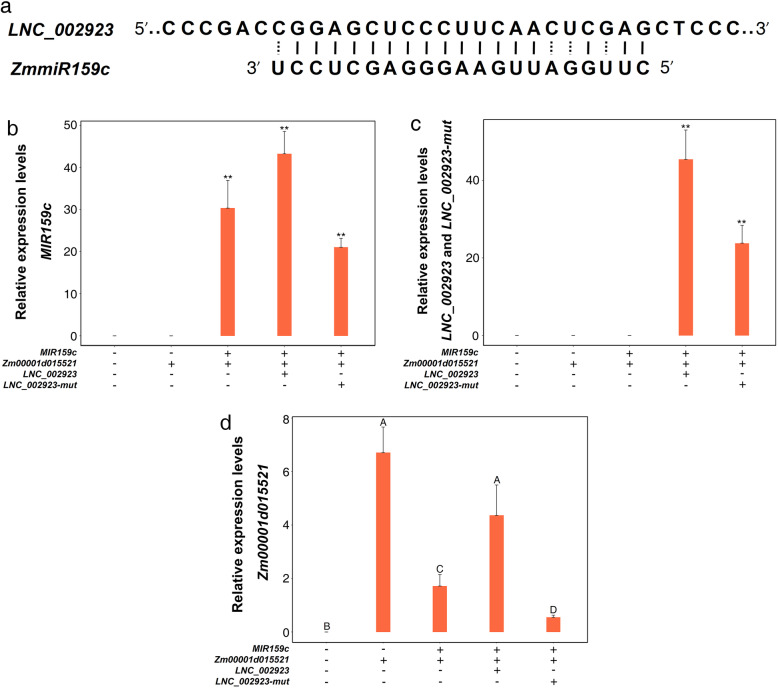

LNC_002923 inhibits the cleavage of Zm00001d015521 by ZmmiR159

According to our previously predicted co-expression regulatory networks, experiments were conducted to verify whether lncRNA affected the mRNA-miRNA pair. The Zm00001d015521 was the predicted target gene of ZmmiR159c. We used ZmmiR159c and ZmmiR159c-mut to construct the transient expression assay in Nicotiana benthamiana, in which ZmmiR159c-mut was designed primers for six loci in ZmmiR159c mature sequence to introduce the target mutation. The expression levels of ZmmiR159c and ZmmiR159c-mut were detected by qRT-PCR (Fig. 5a, c). As shown in Fig. 5b, d, the expression level of Zm00001d015521 significantly decreased when co-expressed with ZmmiR159c, however, the expression level of Zm00001d015521 was not affected when coexpressed with ZmmiR159c-mut. These results indicate that Zm00001d015521 is one of the target genes of ZmmiR159c. Previous studies have found that lncRNA could bind to miRNA, thus relieving the inhibitory effect of miRNA on target genes. In this study, the binding site of ZmmiR159c was found in LNC_002923 sequence (Fig. 6a). We also introduced six mutations in the ZmmiR159c sequence of LNC_002923 (LNC_002923-mut). Then, we conducted transient expression assays in Nicotiana benthamiana to detect whether LNC_002923 could inhabit the cleavage of Zm00001d015521 by ZmmiR159c. The expression levels of ZmmiR159c, LNC_002923 and LNC_002923-mut were detected by qRT-PCR (Fig. 6b, c). As shown in Fig. 6d, the expression level of Zm00001d015521 was not affected when LNC_002923 was co-expressed with ZmmiR159c, indicating that LNC_002923 could effectively inhibit the cleavage of Zm00001d015521 by ZmmiR159c. However, the Zm00001d015521 expression level was significantly decreased when co-expressed with LNC_002923-mut. These results suggested that LNC_002923 could reduce the inhibitory effect of ZmmiR159c.

Fig. 5.

Co-expression the combination expression plasmid of MIR159c/Zm00001d015521 (a, b) and MIR159c-mut/Zm00001d015521 (c, d) in N. benthamiana. The relative expression levels of MIR159c (a) and MIR159c-mut (c) were detected by qRT-PCR, and the data were normalized using U6 gene. The relative expression level of Zm00001d015521 (b, d) were normalized using the 18S gene of tobacco. Same letters are not significant at P < 0.01. **, significant at P < 0.01

Fig. 6.

The diagram of complementary binding sequence of LNC_002923 and ZmmiR159 in maize (a). Co-expression the combination expression plasmid of MIR159c, Zm00001d015521, LNC_002923, LNC002923-mut (b, c, d). The relative expression level of MIR159c (b) were normalized using U6 gene. The relative expression levels of mRNA and lncRNA were normalized using the 18S gene of tobacco (c, d). Same letters are not significant at P < 0.01. **, significant at P < 0.01

Phenotypic differences under HN and LN conditions

The descriptive statistics and broad heritability estimates (H2) of 17 maize seedling traits in HN and LN are presented in Table 2. The significance of genotypes and contrasting N concentrations on maize seedlings could be revealed by the analysis of variance results. Most traits showed significant differences between LN stress and the control, except the seminal root number (SRN). These findings indicated that collection of natural populations was sufficiently diverse for the subsequent association analysis. On average, shoot growth was limited under LN condition, while root growth was enhanced. The shoot length (SL) was greater under HN (36.278) than under LN (30.377) treatment. Moreover, root dry weight (RDW) and total root length (TRL) were higher under LN than under HN. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated for the 17 collected traits under contrasting nitrogen levels listed in Table S8.

Table 2.

Statistics of 17 traits collected

| Trait | Treatment | Mean | Sd | Min | Max | Skew | Kurtosis | H2 | F-value (Treatment) |

F-value (Genotype) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SL (cm) |

HN LN |

36.278 30.377 |

6.113 5.367 |

17.400 16.567 |

52.367 48.233 |

0.152 0.138 |

0.124 0.026 |

0.580 0.570 |

265** |

5.136** 5.028** |

| LN |

HN LN |

3.557 3.370 |

0.363 0.357 |

2.700 2.300 |

5.100 5.000 |

0.252 0.471 |

0.497 1.638 |

0.415 0.404 |

87.15** |

3.128** 3.038** |

| PRL (cm) |

HN LN |

17.968 16.758 |

3.927 3.834 |

4.567 7.250 |

28.300 33.567 |

0.181 0.280 |

0.003 0.782 |

0.271 0.279 |

21.34** |

2.135** 2.171** |

| CRN |

HN LN |

4.030 4.104 |

1.001 0.957 |

0.000 1.000 |

8.000 6.667 |

0.111 0.054 |

1.911 0.051 |

0.410 0.397 |

1.498** |

3.03** 2.978** |

| SRN |

HN LN |

6.332 6.415 |

1.842 1.803 |

2.333 2.556 |

13.667 12.667 |

0.716 0.525 |

1.045 0.186 |

0.677 0.660 |

1.216ns |

7.299** 6.829** |

| RFW (g) |

HN LN |

0.793 0.690 |

0.221 0.183 |

0.273 0.298 |

1.518 1.397 |

0.467 0.563 |

0.122 0.438 |

0.621 0.610 |

112.7** |

5.914** 5.744** |

| SFW (g) |

HN LN |

1.375 0.955 |

0.405 0.262 |

0.450 0.442 |

2.551 1.850 |

0.271 0.417 |

0.256 0.247 |

0.552 0.577 |

451.7** |

4.703** 5.057** |

| TPB (g) |

HN LN |

0.057 0.061 |

0.014 0.015 |

0.028 0.033 |

0.109 0.115 |

0.637 0.602 |

1.291 0.544 |

0.638 0.649 |

31.81** |

6.311** 6.548** |

| LDW (g) |

HN LN |

0.106 0.085 |

0.030 0.024 |

0.045 0.043 |

0.213 0.195 |

0.463 0.762 |

0.131 1.072 |

0.585 0.593 |

180.5** |

5.314** 5.562** |

| TDW (g) |

HN LN |

0.163 0.147 |

0.041 0.036 |

0.074 0.083 |

0.302 0.296 |

0.565 0.776 |

0.607 0.945 |

0.609 0.622 |

67.59** |

5.753** 5.99** |

| TRL (cm) |

HN LN |

267.097 268.077 |

92.748 100.252 |

35.040 71.685 |

649.066 632.929 |

0.534 0.515 |

0.491 0.134 |

0.472 0.516 |

0.18** |

3.686** 4.196** |

| SA (cm2) |

HN LN |

49.225 45.211 |

15.109 14.607 |

12.737 16.316 |

103.775 100.769 |

0.491 0.634 |

0.201 0.537 |

0.545 0.562 |

29.8** |

4.586** 4.845** |

| ARD (cm) |

HN LN |

0.629 0.585 |

0.079 0.075 |

0.424 0.399 |

1.002 0.871 |

0.474 0.472 |

1.416 0.871 |

0.571 0.640 |

107.5** |

5.225** 6.79** |

| RV (cm3) |

HN LN |

0.756 0.632 |

0.247 0.199 |

0.290 0.287 |

1.652 1.227 |

0.820 0.819 |

0.696 0.377 |

0.609 0.616 |

130.1** |

5.681** 5.803** |

| Tips |

HN LN |

337.396 345.986 |

133.261 136.940 |

51.667 96.750 |

756.667 852.800 |

0.600 0.566 |

0.080 0.171 |

0.516 0.571 |

0.614** |

4.197** 4.997** |

| Forks |

HN LN |

1043.947 1057.359 |

470.938 535.802 |

117.000 249.857 |

2939.571 3568.400 |

0.807 1.145 |

0.655 2.286 |

0.618 0.633 |

0.071** |

5.853** 6.182** |

| Crossings |

HN LN |

132.270 147.887 |

83.802 95.869 |

9.333 13.833 |

477.750 607.600 |

1.114 1.278 |

1.104 2.347 |

0.495 0.518 |

6.616** |

3.942** 4.219** |

**Significant at P < 0.01; ns Not significant; H2 Broad-sense heritability; HN High nitrogen; LN Low nitrogen. SL Shoot length; LN Leaf number; PRL Primary root length; CRN Crown root number; SRN Seminal root number; RFW Root fresh weight; SFW Shoot fresh weight; TPB Total plant biomass; LDW Leaf dry weight; TDW Total dry weight; TRL Total root length; SA Surface area; ARD Average root diameter; RV Root volume

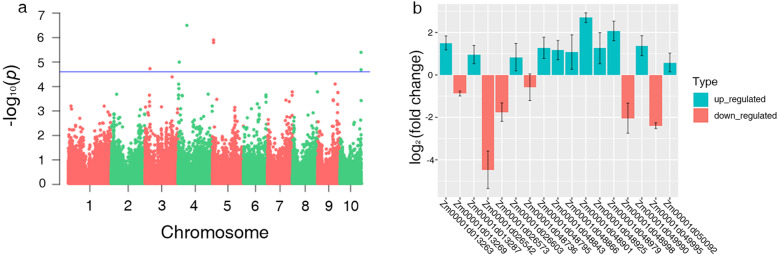

Candidate genes revealed by genome-wide association analysis

For the genome-wide identification of significant SNPs associated with traits, the software TASSEL 5.0 was selected to conduct GWAS with 46,108 high-quality SNPs (MAF > 0.01) using a mixed linear model (MLM) and markers with a p-value of <1e− 4.6 were considered for candidate gene analysis. A total of 23 significant markers were detected by low nitrogen tolerance index (LNTI) and three markers were detected under LN treatment. Among them, 12 SNPs were found to be associated with the crown root number (CRN). Seven and three significant associations corresponded to Forks and Tips, respectively, and three markers were associated with each of Crossings and average root diameter (ARD). Moreover, one SNP was found to be significantly associated with two root traits (Forks and Tips). According to the average linkage disequilibrium (calculated by TASSEL 5.0) decay distance across all 10 maize chromosomes within the mapping population, a total of 1474 candidate genes were screened near these significantly associated SNP markers. Three significant markers were associated with 232 genes under LN treatment, namely, PUT-163a-13,126,581-167, PZE-104092320, and PZE-109052750, and they were respectively associated with seminal root number (SRN), Crossings, and Tips and located on chromosomes 4, 6, and 9. Meanwhile, 23 significant SNPs associated with 1242 candidate genes were revealed by LNTI value. A list of all significant markers’ trait associations is presented in Table S7. According to the location of identified lncRNAs, a total of 36 and 134 differently expressed lncRNAs within the range of significant markers were screened under LN and LNTI, respectively (Table S7). These LN-responsive candidate genes and lncRNAs could play vital roles in regulating root development during the maize seedling stage.

Combining GWAS and expression profile to mine consistent candidate genes

Combined with GWAS and RNA-Seq, we found that among 232 candidate genes detected by GWAS under LN condition, 16 and 29 candidate genes respectively showed obvious downregulation and upregulation patterns, and 7 candidate genes were expressed in roots and leaves (Fig. S6a and Table S7). At the same time, among 1013 candidate genes detected by GWAS under LNTI, 107 and 125 candidate genes showed downregulation and upregulation respectively, among which 38 candidate genes were expressed in roots and leaves (Fig. S6b and Table S7). Besides, integrating the results of multiple RNA-seq and GWAS, a total of 10 significant SNPs (P < 1e− 4.6) were associated with 34 candidate genes identified by using LNTI of root traits, and one significant SNP associated with six candidate genes was identified under LN stress (Table 3). The expression levels of candidate genes in which GWAS-identified SNPs located were evaluated in 255 maize lines through RNA-Seq of root at the maize seedling stage under LN stress. This includes the discovery of two genes in the integration of meta-analysis and large-scale gene expression profile data of maize under LN stress [22]. For example, Zm00001d051804 plays an important role in glutamine biosynthesis in response to exogenous nitrogen during seed germination in maize and Arabidopsis [26]. In addition, Zm00001d048998 is a chlorophyll A-B binding protein, which is involved in the absorption and utilization of nitrogen nutrients in maize [21]. For other genes, Zm00001d051666 and Zm00001d049380 were found to be associated with nitrogen acquisition in maize roots [23]. Finally, six candidate genes were found in RNA-seq of maize root in response to nitrogen stress [24], and 29 genes were consistently detected upon comparing with research involving GWAS of carbon and nitrogen metabolism in maize [25], respectively. The Manhattan plots for Forks and fold change values from RNA-Seq are shown in Fig. 7a, b. These consistent candidate genes explored in our research could contribute strongly to deficient nitrogen tolerance.

Table 3.

Results for SNP loci with root traits and consistent candidate genes jointly identified by association and RNA-Seq

| Candidate genes based on RNA-Seqc | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait | SNP | Chr | Positiona | P | Alleles | R2 (%) | Geneb | Reference | Annotation | Fold change |

| Forks | PZE-104010552 | 4 | 7,929,588 | 5.0 × 10−5 | A/G | 8.9 | Zm00001d048998 | Mu et al. 2017 [21] | Chlorophyll a-b binding protein CP26 | −2.03939 |

| Crossings | PZE-104092320 | 4 | 167,437,768 | 4.7 × 10−5 | A/G | 1.8 | Zm00001d051804 | Luo et al. 2015 [22] | Glutamine synthetase root isozyme 4 | 1.65671 |

| Forks | PZE-104043052 | 4 | 61,411,237 | 6.5 × 10− 5 | A/C | 11 | Zm00001d049995 | Nitrate reductase [NADH] | −2.39002 | |

| Crossings | PZE-104092320 | 4 | 167,437,768 | 4.7 × 10−5 | A/G | 1.8 | Zm00001d051666 | Zanin et al. 2015 [23] | Neutral/alkaline invertase | 1.83246 |

| PRL | ZM005894–0463 | 4 | 31,060,531 | 5.6 × 10−5 | A/C | 9.9 | Zm00001d049380 | Putative aminotransferase superfamily protein | 0.66934 | |

| CRN | PZE-104016717 | 4 | 16,500,659 | 5.2 × 10−5 | A/G | 11 | Zm00001d049059 | He et al. 2016 [24] | Alcohol dehydrogenase2 | 0.766936 |

| Tips | PZE-104049074 | 4 | 75,505,829 | 5.2 × 10−5 | A/G | 8.7 | Zm00001d050195 | WRKY DNA-binding domain protein | −0.795948 | |

| Forks | PZE-104010552 | 4 | 7,929,588 | 5.0 × 10−5 | A/G | 8.9 | Zm00001d048866 | (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol acetyltransferase | 1.07489 | |

| Forks | PZE-104010552 | 4 | 7,929,588 | 5.0 × 10−5 | A/G | 8.9 | Zm00001d048736 | S-alkyl-thiohydroximate lyase SUR1 | −0.576864 | |

| CRN | PZE-105047147 | 5 | 36,470,371 | 6.1 × 10−5 | A/G | 13 | Zm00001d014200 | Expressed protein | 0.402627 | |

| Forks | PUT-163a-91,875,212-4781 | 5 | 7,724,698 | 5.9 × 10−5 | A/G | 10 | Zm00001d013263 | Expressed protein | 1.51149 | |

| Forks | PZE-104043052 | 4 | 61,411,237 | 6.5 × 10−5 | A/C | 11 | Zm00001d050092 | Zhang et al. 2015 [25] | Putative subtilase family protein | 0.585778 |

| Forks | PZE-104043052 | 4 | 61,411,237 | 6.5 × 10−5 | A/C | 11 | Zm00001d049990 | Putative ENTH/ANTH/VHS protein | 1.38056 | |

| PRL | ZM005894–0463 | 4 | 31,060,531 | 5.6 × 10−5 | A/C | 9.9 | Zm00001d049554 | Putative glycerol-3-phosphate transporter 1 | −0.807844 | |

| PRL | ZM005894–0463 | 4 | 31,060,531 | 5.6 × 10−5 | A/C | 9.9 | Zm00001d049551 | Putative cytochrome P450 protein | 2.50626 | |

| PRL | ZM005894–0463 | 4 | 31,060,531 | 5.6 × 10−5 | A/C | 9.9 | Zm00001d049502 | maternal effect embryo arrest 60 | 0.542646 | |

| PRL | ZM005894–0463 | 4 | 31,060,531 | 5.6 × 10−5 | A/C | 9.9 | Zm00001d049464 | B-box type zinc finger family protein | 0.980937 | |

| PRL | ZM005894–0463 | 4 | 31,060,531 | 5.6 × 10−5 | A/C | 9.9 | Zm00001d049418 | Germin-like protein subfamily 1 member 8 | 1.11388 | |

| PRL | ZM005894–0463 | 4 | 31,060,531 | 5.6 × 10−5 | A/C | 9.9 | Zm00001d049407 | Polyphenol oxidase chloroplastic | −0.61096 | |

| PRL | ZM005894–0463 | 4 | 31,060,531 | 5.6 × 10−5 | A/C | 9.9 | Zm00001d049365 | Methionine aminopeptidase | 0.319478 | |

| CRN | PZE-104016717 | 4 | 16,500,659 | 5.2 × 10−5 | A/G | 11 | Zm00001d049187 | Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase3 | −1.54203 | |

| CRN | PZE-104016717 | 4 | 16,500,659 | 5.2 × 10−5 | A/G | 11 | Zm00001d049158 | Transcription factor bHLH62 | 1.27949 | |

| CRN | PZE-104016717 | 4 | 16,500,659 | 5.2 × 10−5 | A/G | 11 | Zm00001d049127 | Putative serine/threonine protein | −0.848596 | |

| Forks | PZE-104010552 | 4 | 7,929,588 | 5.0 × 10−5 | A/G | 8.9 | Zm00001d048979 | Putative sucrose-phosphate synthase protein | 2.06952 | |

| Forks | PZE-104010552 | 4 | 7,929,588 | 5.0 × 10−5 | A/G | 8.9 | Zm00001d048925 | Hydroquinone glucosyltransferase | 1.25909 | |

| Forks | PZE-104010552 | 4 | 7,929,588 | 5.0 × 10−5 | A/G | 8.9 | Zm00001d048901 | Transcription factor bHLH47 | 2.69849 | |

| Forks | PZE-104010552 | 4 | 7,929,588 | 5.0 × 10−5 | A/G | 8.9 | Zm00001d048843 | Math-btb9 | 1.16984 | |

| Forks | PZE-104010552 | 4 | 7,929,588 | 5.0 × 10−5 | A/G | 8.9 | Zm00001d048795 | SPR1 | 1.27812 | |

| Forks | PZE-104010552 | 4 | 7,929,588 | 5.0 × 10−5 | A/G | 8.9 | Zm00001d048709 | benzoxazinless1 | −5.53653 | |

| Forks | PZE-110109365 | 10 | 148,503,798 | 4.7 × 10−5 | A/G | 7.5 | Zm00001d026605 | Endoglucanase 5 | −5.62458 | |

| Forks | PZE-110108403 | 10 | 148,106,661 | 5.4 × 10−5 | A/C | 8.9 | Zm00001d026603 | Mg chelatase subunit H 1 | 0.836012 | |

| Forks | PZE-110108403 | 10 | 148,106,661 | 5.4 × 10−5 | A/C | 8.9 | Zm00001d026573 | Methylthioribose kinase | −1.75366 | |

| Forks | PZE-110108403 | 10 | 148,106,661 | 5.4 × 10−5 | A/C | 8.9 | Zm00001d026542 | Myb family transcription factor PHL5 | −4.47132 | |

| CRN | PZE-105047221 | 5 | 36,532,569 | 5.6 × 10−5 | A/G | 11 | Zm00001d014555 | Tyrosine-sulfated glycopeptide receptor 1 | −1.98805 | |

| Forks | PUT-163a-91,875,212-4781 | 5 | 7,724,698 | 5.9 × 10−5 | A/G | 10 | Zm00001d013287 | – | 0.957732 | |

| Forks | PUT-163a-91,875,212-4781 | 5 | 7,724,698 | 5.9 × 10−5 | A/G | 10 | Zm00001d013269 | Beta-glucanase3 | −0.88007 | |

| Crossings | PZE-104092320 | 4 | 167,437,768 | 4.7 × 10−5 | A/G | 1.8 | Zm00001d051829 | U-box domain-containing protein 44 | 0.605786 | |

| Crossings | PZE-104092320 | 4 | 167,437,768 | 4.7 × 10−5 | A/G | 1.8 | Zm00001d051692 | Aspartyl protease AED1 | 0.609318 | |

| Crossings | PZE-104092320 | 4 | 167,437,768 | 4.7 × 10−5 | A/G | 1.8 | Zm00001d051664 | 2OG and Fe (II)-dependent superfamily protein | 0.924731 | |

| Crossings | PZE-104092320 | 4 | 167,437,768 | 4.7 × 10−5 | A/G | 1.8 | Zm00001d051598 | Plant-specific domain TIGR01570 protein | 1.82658 |

a The physical position of significant SNPs were based on the Maize B73 RefGen_v3. b The Genes were screened near these significantly associated SNP markers. c The candidate genes were identified by combining with RNA-Seq and previous studies, the expression (Log2(fold change)) based on us RNA-Seq

Fig. 7.

Manhattan plots of the MLM for FORKs in lines (a). Transcript level difference of candidate genes detected in RNA-Seq of Log2 (fold change) of FPKM around significant SNPs

To investigate the regulatory roles of lncRNAs in maize seedlings under LN stress, using the predictive lncRNA targets, potential lncRNAs that could influence 40 consistently LN-response candidate genes in a cis or trans manner were identified. As shown in Fig. 4c, a total of 354 lncRNAs were found. Furthermore, these targets of lncRNAs contained significant SNPs for multiple root traits (Table S9), and lncRNA targets were found to be significantly associated with nitrogen metabolism and the abiotic stress response pathway. Of these lncRNAs, we found LNC_002984, LNC_002985, and LNC_002986 located upstream of Zm00001d051804 that could potentially regulate the expression levels of neighboring genes in a cis manner. Zm00001d051804 was reported to be related to the response to low nitrogen stress [22]. Moreover, the homologous gene in Arabidopsis was shown to play an important redundant role in ammonium assimilation under ammonium-deficient conditions and in facilitating nitrogen remobilization in root [27, 28]. This implies these lncRNAs could play an important role in root development, especially in nitrogen absorption, transfer, and assimilation in plants. The present analysis provides new information for understanding lncRNAs as important regulators in growth and development associated with LN stress.

Discussion

Increasingly researches have focused on the regulatory mechanisms of noncoding RNA. Many potential lncRNAs were identified in mammals and plants, and were found to be associated with human diseases and regulation of the expression levels of genes involved in biological processes in plants [29–31]. The ceRNA hypothesis is a new option for explaining how lncRNAs and protein-coding genes communicate with each other through microRNA response elements (MREs). Genome-wide screening and analysis of lncRNAs can provide new insights into how plants respond to LN stress. In the present study, deep sequencing of 12 lncRNA and 12 small RNA libraries created from maize seedlings at the early stages of exposure to HN and LN conditions was performed. We identified 894 reliably differentially expressed lncRNAs and 38 miRNAs, including 19 novel miRNAs.

MicroRNAs mediate communication between lncRNAs and mRNAs

MicroRNAs as the core of the co-expression network are responsible for mediating lncRNAs and mRNAs. We identified miR159c and miR164a could communicate with individual lncRNAs, and these lncRNAs were communicated by competing specific miRNAs. MiR159 was shown to control the expression of GAMYB-like genes in anthers and seeds; these transcription factors are involved in GA-induced aleurone development and death [32], and was also reported to regulate many target genes, such as MYB transcription factors and conserved R2R3 domain [33]. The inhibition induced by miR159 could reduce the repression of MYB33/65 and play an important role in vegetative development [34]. Specifically, miR159 has been reported to participate in response to phosphate starvation [35]. However, studies on miR159 functions in the context of LN stress have not been reported. MiR164 was reported to participate in lateral root initiation [36] and LN stress response [37]. Under nitrate-starvation condition, miR164 could cut its target gene NAC1 between the 10th and 11th bases at the post-transcriptional level to resist LN availability [38]. In conclusion, under the co-expression networks, LNC_003272 and LNC_002923 could play pivotal roles in biological processes, including root system development and seed germination, as well as potentially participating in inhibiting the effects of miRNAs in response to nitrogen deficiency.

The co-expression network showed dynamic expression and regulation patterns during the seedling processes

According to the results, there were 2 lncRNAs, 2 miRNAs, and 14 mRNAs included in the network, forming two co-expression regulatory networks (Fig. 4a, b). The analysis of qRT-PCR showed the pattern of co-expression networks similar to the ceRNA hypothesis at most stages after LN treatment. For the co-expression network in leaf, the expression trend of Zm00001d023434 was consistent with that of LNC_002923, but opposite to that of miR159c. In the root, the expression of miR164a showed the opposite pattern to Zm00001d041472, but was consistent with that of Zm00001d003414 at 14 days after LN stress. The expression of LNC_003272 could not be detected at most stages, except 10 and 14 days. Meanwhile, the gene Zm00001d015521 was reported to regulate the metabolism of the plant hormone cytokinin and to be influenced by chlorophyll biosynthesis genes, and increased the number of absorbing roots and promoted the growth of seedlings [39]. Moreover, Zm00001d041472 was found to participate in nitrogen accumulation in vegetable tissue and improve stay-green and yields in maize [40]. Taking these findings together, we suggested LNC_002923 and LNC_003272 could participate in the pathway of nitrogen utilization to regulate chloroplast development, nitrogen utilization, as well as potentially participating in inhibiting the effects of miRNAs in response to nitrogen deficiency.

LNC_002923 inhibits the cleavage of Zm00001d015521 by ZmmiR159

Previous studies indicated that lncRNAs could regulate mRNA translation and compete with miRNAs to indirectly influence the expression of coding genes in animals and plants [12, 41]. We predicted two co-expression networks based on lncRNAs and mRNAs have the same miRNA binding sites. The genes were constructed into pCAMBIA2300-35S-OCS vector, then the various combinations was performed transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana. We demonstrated that ZmmiR159 could cut the target gene Zm00001d015521 and inhibit its expression level. Moreover, we found LNC_002923 could inhibit the cleavage of Zm00001d015521 gene guided by ZmmiR159c. The homologs of Zm00001d015521 in Arabidopsis was found that related to the development and growth of root and shoot, as well as abiotic stress such as drought and nutrition [39], meanwhile, miR159 has been reported to be involved in abiotic stress response-related pathways and plant growth and development [32, 35]. Based on these results, we concluded that the relatively high abundance of LNC_002923 could effectively inhibit ZmmiR159c to cleave potential coding genes, and further regulated Zm00001d015521 to play an important regulatory role in response to low nitrogen stress in maize.

GWAS and RNA-Seq for low nitrogen tolerance

Here it was necessary to combine multiple methods to obtain reliable information. An integrated method comprising GWAS, RNA-Seq, and genomic selection combined with phenotypic data collected from different environments found 16 loci that were significantly associated with soybean resistance to white mold in the field and 11 loci in the greenhouse [42]. In maize, metabolite profiling and GWAS were combined to analyze the mechanisms of response to low-Pi stress, and validation in a recombinant inbred line population found some candidate genes related to yield [20]. We screened 40 consistently LN-responsive candidate genes by integrating RNA-Seq profiles and GWAS data. Notably, among these 12 significant SNPs associated with five root traits, there were seven SNPs associated with Forks, Crossings, Tips, PRL, and CRN located on chromosome 4. A previous GWAS study [43] also found candidate genes controlling root growth and development on chromosome 4. Furthermore, some studies also detected that QTLs related to nitrogen utilization and phosphorus absorption were located on chromosome 4 [44, 45]. The consistency of the results from the present study with previous findings indicates that candidate genes potentially influencing root growth and nutrient utilization under LN stress are probably located on chromosome 4.

Targets analysis reveals the potential regulatory of LN-responsive lncRNAs in maize

We performed GO and KEGG analyses of lncRNAs and found there were significant numbers of GO terms related to the histidine biosynthetic process, nitrate metabolic process, and chromatin remodeling. Our findings showed that these lncRNAs are involved in the regulation of abiotic stress and nutrition metabolism [12, 46]. Furthermore, KEGG analysis focusing on the biological processes related to plant growth and nutrition metabolism showed that these lncRNAs could interact with mRNAs in the maize seedling in response to LN stress, and were particularly associated with photosynthesis and secondary metabolite synthesis (p < 0.05). Taken together, we suggested these lncRNAs participated in the key biological processes including development, biosynthesis, and abiotic stress response.

In the lncRNA-mRNA pairs, 44 and 310 lncRNAs were predicted to regulate transcriptional activation and expression of 24 neighboring and 16 distant genes in cis and trans manners, respectively, and to be regulated by multiple lncRNAs. In particular, the lncRNAs associated with Zm00001d051804, Zm00001d048998, Zm00001d051666, and Zm00001d049380, which could play large roles in determining root growth and responding to the availability of nitrogen in a cis and trans manner, warrant further study. Our results are interesting for further exploration of the functions of lncRNAs and their target genes in seedlings under LN stress. However, to date, no research has been performed combining GWAS and lncRNAs together to study the mechanism of LN response in maize seedlings.

Conclusion

We identified several hundred differentially expressed lncRNAs in maize seedlings and used them to construct two co-expression networks that lncRNA as ceRNA based on the “ceRNA hypothesis.” Combining GWAS and expression profiles, a total of 40 consistently LN-responsive candidate genes and lncRNAs potentially related to root traits were identified. Further research on biological function and regulation, including the identification of nearby and distant targets, GO enrichment, and KEGG analysis, should provide useful information for obtaining a deeper understanding of the mechanisms of lncRNA regulation during the early stages of N deficiency in maize seedling development, and for providing new insights enabling increased efficiency of breeding for nitrogen utilization.

Methods

Plant materials

Seeds of maize inbred line P178 and Nicotiana benthamiana were used in this study (both provided by the Maize Research Institute of Sichuan Agricultural University). The association mapping panel comprised 362 inbred lines with great variation in genetic background obtained from the Southwest China Breeding Program, the population has been reported in our pervious study, including the population structure, genetic diversity, and linkage disequilibrium decay distance [47].

Growth conditions

Seeds of maize inbred line 178 were surface–sterilized with 6% sodium hypochlorite for 15 min, washed twice with deionized water, immersed in saturated CaSO4 for 12 h, and then germinated in coarse quartz sand until two leaves were visible. After the endosperms had been removed, the seedlings were placed in a 25-L bucket containing improved half-concentration Hoagland’s nutrient solution for 2 days to adapt to the hydroponic environment and then supplied with full-concentration Hoagland’s nutrient solution. For HN treatment, the nutrient solution consisted of (mM): 4 KNO3, 4 MgSO4, 5 KCL, 5 CaCL2, 1 KH2PO4, 0.1 Fe-EDTA, 0.046 H3BO4, 0.009 MnSO4, 0.0007 ZnSO4, 0.0003 CuSO4, and 0.0002 (NH4)6Mo7O24. For LN treatment, the 4 mM KNO3 was replaced by 0.04 mM KNO3. The pH of the solution was adjusted to 6.0–6.5 and nutrient solution was renewed every 2 days. The seedlings were grown in a greenhouse with a photoperiod of 16/8 h (light/darkness) and 25/22 °C, with light intensity of 200 μmol photons m− 2 s− 1. The relative humidity was maintained at 65%. Three independent replications were conducted and each experiment included at least three seedlings under both HN and LN conditions. The second fully expanded leaf from top to bottom and whole roots were sampled, dried on blotting paper, frozen immediately in liquid N2 and finally stored in − 80 °C.

RNA isolation, and library preparation for lncRNA and small RNA sequencing

Total RNAs were extracted from 14-day-old seedlings of leaves and roots under HN and LN conditions. The libraries of lncRNAs and small RNAs were sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq2500 platform from 12 samples labeled as HN_178L1, HN_178L2, HN_178L3, HN_178R1, HN_178R2, HN_178R3, LN_178L1, LN_178L2, LN_178L3, LN_178R1, LN_178R2, and LN_178R3. RNA purity was checked using the NanoPhotometer® spectrophotometer (IMPLEN, CA, USA). RNA concentration was measured using Qubit® RNA Assay Kit in a Qubit® 2.0 Flurometer (Life Technologies, CA, USA) and integrity was assessed using the RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit of the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). A total of 3 μg of RNA per sample was used as input material for the RNA and small RNA libraries. After RNA products had been purified (AMPure XP system), library quality was assessed on the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system. The libraries were sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq 2500 platform by Novogene (Beijing, China).

Bioinformatics identification of lncRNAs

The pipeline used for the identification of lncRNAs is described in Fig. 1a. Clean data were obtained by removing reads containing adapters, reads containing poly-N, and low-quality reads from the raw data. The clean data of high quality that mapped to the B73 RefGen_V4 genome were downloaded directly from genome website (http://www.gramene.org/). An index of the reference genome was built using Bowtie v2.0.6 [48] and paired-end clean reads were aligned to the reference genome using TopHat [49] v2.0.9. After the alignment, the mapped reads of each sample were assembled by both Scripture (beta2) [50] and Cufflinks (v2.1.1) [51] in a reference-based approach. Both methods use spliced reads to determine exon connectivity, but with two different approaches. Next, transcripts predicted to have coding potential by CPC [52] and Pfam Scan [53] were filtered out, and those without coding potential were used as our candidate set of lncRNAs. Cuffdiff (v2.1.1) [51] was used to calculate FPKMs of both lncRNAs and coding genes in each sample. Cuffdiff provides statistical routines for determining differential expression in digital transcript or gene expression data using a model based on the negative binomial distribution. Transcripts with an adjusted P < 0.05 were assigned as differentially expressed.

Analysis of small RNA sequencing data

After the removal of the reads containing poly-N, with 5′ adapter contamination, without 3′ adapter or insert tag, and low-quality reads from the raw data, the small RNA tags were mapped to the maize B73 RefGen_V4 genome by Bowtie [48] without mismatch for further analysis. Rfam 11.0 [54] was applied to remove tags originating from protein-coding genes, repeat sequences, rRNA, tRNA, snRNA, and snoRNA. Then, mapped small RNA tags were used to look for known miRNAs. MiRBase20.0 was used as a reference, while modified software mirdeep2 [55] and sRNA-tools-cli were used to obtain potential miRNAs and draw the secondary structures. The characteristic hairpin structure of miRNA precursors could be used to predict novel miRNAs. The software miREvo [56] and mirdeep2 [55] were integrated to predict novel miRNAs through exploring the secondary structure, the dicer cleavage site, and the minimum free energy of the small RNA tags unannotated in the previous steps. The expression levels were estimated by transcripts per million (TPM) through the following criteria [57]. Differential expression analysis of two conditions/groups was performed using the DESeq R package (1.8.3). The P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini & Hochberg method. A corrected P-value of < 0.05 was set as the threshold for significant differential expression by default.

Prediction of target genes

The cis-acting mechanism of lncRNAs involves them acting on neighboring target genes. To identify such lncRNAs, a search was performed for coding genes 10–100 kb upstream and downstream of the lncRNAs; the function of those identified was then analyzed. The trans-acting mechanism of lncRNAs to identify each other by the expression level. We clustered the genes from different samples to search for common expression modules and then analyzed their function through functional enrichment analysis. Predicting the target genes of miRNA was performed by psRobot_tar in psRobot [58] for plants.

Validation of quantitative real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was applied to validate the results of sequencing. Total RNA was extracted from the leaves and roots of line 178 harvested after 0 h, 1 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 2 days, 4 days, 6 days, 8 days, 10 days, 12 days, and 14 days of nitrogen treatment using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription of mRNA and small RNA was performed with PrimeScript™ II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (TAKARA) and SYBR® PrimeScript™ miRNA RT-PCR Kit (TAKARA), following the manufacturer’s instructions, respectively.

The qRT-PCR validation of the lncRNAs, mRNAs, and miRNAs was performed with the Roche Cobas Z480 system using FastStart Essential DNA Green Master (Roche) and SYBR® PrimeScriptTM miRNA RT-PCR Kit (TAKARA). Data were analyzed by relative quantification using the myosin (mRNA and lncRNA qPCR) and U6 (miRNA qPCR) genes as standards. Three independent experiments were performed, and each experiment was performed in three technical replicates.

Construction of co-expression networks related to the development of maize

Based on the “ceRNA hypothesis”, MREs could be acted as the core by which transcripts could influence to each other to regulate their expression levels. First, the target genes of differentially expressed lncRNA and differential expressed mRNAs were combined to analysis. When the targets of lncRNAs were also significantly different, the mRNAs were more likely to be regulated by lncRNAs. Then, filtering out those lncRNAs that could be miRNA precursors based on the homology of lncRNA and miRNA precursors, the software psRobot was applied to predict the target lncRNAs of miRNAs. Third, the upregulated and downregulated results of each group of differentially expressed genes to identify candidate miRNAs that act on mRNAs. Finally, co-expression networks were constructed in which lncRNA was the decoy, miRNA was the core, and mRNA was the target gene.

Marker data

The MaizeSNP50 BeadChip containing 56,110 SNPs was used for genotyping the panel. Detailed information about this chip can be downloaded from the Illumina MaizeSNP50 website (http://support.illumina.com/array/array_kits/ maizesnp50_dna_analysis_kit/downloads.html) and the positional information of SNPs according to B73 RefGen_v2 can be downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GEO website.

Phenotypic measurement

A paper roll growth method was applied for culturing maize [59]. The growth conditions and nutrient solution were the same as previously described. Then, the seeds were surface–sterilized with 6% sodium hypochlorite sodium, and placed on moist filter paper to germinate in the dark. After 2 days, six germinated maize kernels were placed on a double layer of brown germination roll paper (Anchor Paper, St. Paul, MN, USA) that had been pre-moisturized with fungicide solution Captan (2.5 g/L). Germination paper rolls were placed vertically in a 10-l plastic bucket containing 5 l of nutrient solution (HN and LN). The pH of the solution was adjusted to 6.0–6.5. The nutrient solution was renewed every 2 days.

Each paper roll with six seedlings was regarded as an experimental unit. The association line was cultured in a completely random design in three independent replications completed in a greenhouse. After 14 days, seedlings were removed from the plastic bucket and phenotypic traits were measured (three similar seedlings out of six within each roll were sampled, to eliminate possible outliers within lines, and all traits’ means were taken). If measurement could not be performed on a particular day, the nutrient solution was replaced with 30% ethanol to prevent further growth. The root traits were recorded by the WinRhizo program. After measurements had been completed, shoots and roots were collected separately and dried for at least 48 h at 80 °C in an oven dryer.

Phenotypic analysis

Phenotypic descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients were analyzed using R software. Analyses of variance of seedling traits and broad-sense heritability (H2) were performed by SAS. The traits of low nitrogen tolerance index (LNTI) and means were employed to perform GWAS, in which LNTI is the relative trait value that the HN treatment was divided by the same trait value for the LN treatment.

Association analysis of low nitrogen tolerance-related traits

The allelic frequencies of 255 maize inbred lines and population structure were calculated using the software PowerMarker3.25 [60] and STRUCTURE 2.3 [61], respectively. Kinship was measured with the Genome Association and Prediction Integrated Tool-R package (GAPIT) and STRUCTURE was set to K = 2, in accordance with the results of a previous study [47]. SNPs with low minor allele frequency (MAF) < 0.01 and missing rate > 0.2 were removed, which left 46,108 high-quality SNPs for further association analysis. All markers were evenly distributed on 1–10 chromosomes. The software TASSEL 5.0 [62] was selected to conduct GWAS with the 46,108 high-quality SNPs (MAF > 0.01) using a mixed linear model (MLM) and markers with P > 4.6 were considered for candidate gene analysis.

Transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana

The full-length cDNA of genes and lncRNA were amplified with the specific primers. The precursor of ZmMIR159 and ZmMIR164 were amplified from genomic DNA. As a negative control, the sequence of LNC_002923, LNC_003272, ZmMIR159 and ZmMIR164 were conducted to generate site-directed mutagenesis with the Mut Express II Fast Mutagenesis Kit V2 (Vazyme, Nanjing, CN). All the amplified fragments were cloned into the pCAMBIA2300-35S-OCS vector using the SalI restriction site by In-Fusion (TAKARA). The expression plasmids were transformed into A. tumefaciens EHA105 and were injected into the epidermis of N. benthamiana for transient expression. Four independent experiments were performed. The RNA was extracted from leaves after 2 day using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) as described above.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. The volcano plot of differentially expressed mRNAs (a, b), TUCPs (c, d) and miRNAs (e, f) between HN and LN conditions in leaf and root. Fig. S2. The TPM (Transcripts per million) (a) and length distribution of 18- to 30-nt small RNAs (b). The concentrated length distribution with the peak at 24-nt in the 12 libraries respectively. Fig. S3. Expression profiles of mRNA and miRNA during seedling under HN and LN conditions. Cluster heat map of all mRNAs (a) and miRNAs (c) expression in leaf and root. VEEN analysis of differentially expressed mRNAs (b) and miRNAs (d). Fig. S4. Characteristics of lncRNAs identified in maize seedling. Fig. S5. Functional analysis of the LN-responsive lncRNAs. The enriched Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes (KEGG) pathways in leaf (a, c) and root (b, d). Fig. S6. Fourty-five and 232 consistent candidate genes were detected in root and leaf under LN condition (a) and LNTI (b) by combing with RNA-Seq and GWAS.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Known miRNAs and novel miRNAs identified from RNA-Seq.Table S2. The targets of lncRNAs predicted by co-location and co-expression. Table S3. LncRNA-mRNA pairs of cis-acting. Table S4. LncRNA-mRNA pairs of trans-acting. Table S5. The GO analysis of lncRNAs. Table S6. The KEGG analysis of lncRNAs. Table S7. The candidate genes identified by GWAS and RNA-Seq. Table S8. Pearson (r) correlations between all 17 traits. Table S9. The targets of lncRNAs contained significant SNPs for multiple root traits. Table S10. The information of primer sequences used in this study. Table S11. Trait abbreviation and description collected by manually and WinRizo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wenxue Li (Institute of Crop Science, National Engineering Laboratory for Crop Molecular Breeding, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences) for comments in the experiment of site-directed mutagenesis. We would also like to thank Beijing Novogene Co., Ltd. for assistance with the RNA-Seq experiments and data analysis.

Abbreviations

- HN

High nitrogen

- LN

Low nitrogen

- GWAS

Genome-wide association study

- SNPs

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms

- LncRNAs

Long-noncoding RNAs

- CeRNAs

Competing endogenous RNAs

- MREs

MicroRNA response elements

- LD

Linkage disequilibrium

- TPM

Transcripts per million

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR

- H2

Heritability

- LNTI

Low nitrogen tolerance index

- MAF

Minor allele frequency

- MLM

Mixed linear model

- TUCPs

Transcripts of uncertain coding potential

- SRN

Seminal root number

- RDW

Root dry weight

- SL

Shoot length

- TRL

Total root length

- CRN

Crown root number

Authors’ contributions

SG: Designed the experiment. PM, BL, and XZ: Conducted the experimental design and data analysis. ZC, XH, HZ, BL, DL, LW, SG, DG and ZS: Performed data collection. PM and SG: Drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant from the National Key Technologies Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0100707 and 2018YFD0200707). The Sichuan science and technology support project (2021YFYZ0027). China Agricultural Research System (CARS-02), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31971955).

Availability of data and materials

All original data can be downloaded from the NCBI database (accession number: PRJNA661965 and PRJNA662035).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Peng Ma and Xiao Zhang contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Xu G, Fan X, Miller AJ. Plant nitrogen assimilation and use efficiency. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2012;63:153–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xuan W, Beeckman T, Xu G. Plant nitrogen nutrition: sensing and signaling. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2017;39:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2017.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li S, Tian Y, Wu K, Ye Y, Yu J, Zhang J, et al. Modulating plant growth–metabolism coordination for sustainable agriculture. Nature. 2018;560:595–600. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0415-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiba Y, Shimizu T, Miyakawa S, Kanno Y, Koshiba T, Kamiya Y, et al. Identification of Arabidopsis thaliana NRT1/PTR FAMILY (NPF) proteins capable of transporting plant hormones. J Plant Res. 2015;128:679–686. doi: 10.1007/s10265-015-0710-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lezhneva L, Kiba T, Feria-Bourrellier AB, Lafouge F, Boutet-Mercey S, Zoufan P, et al. The Arabidopsis nitrate transporter NRT2.5 plays a role in nitrate acquisition and remobilization in nitrogen-starved plants. Plant J. 2014;80:230–241. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Angeli A, Monachello D, Ephritikhine G, Frachisse JM, Thomine S, Gambale F, et al. The nitrate/proton antiporter AtCLCa mediates nitrate accumulation in plant vacuoles. Nature. 2006;442:939–942. doi: 10.1038/nature05013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krouk G, Lacombe B, Bielach A, Perrine-Walker F, Malinska K, Mounier E, et al. Nitrate-regulated auxin transport by NRT1.1 defines a mechanism for nutrient sensing in plants. Dev Cell. 2010;18:927–937. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loqué D, Lalonde S, Looger LL, Von Wirén N, Frommer WB. A cytosolic trans-activation domain essential for ammonium uptake. Nature. 2007;446:195–198. doi: 10.1038/nature05579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kopp F, Mendell JT. Functional classification and experimental dissection of long noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2018;172:393–407. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salmena L, Poliseno L, Tay Y, Kats L, Pandolfi PP. A ceRNA hypothesis: the rosetta stone of a hidden RNA language? Cell. 2011;146:353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Xu Z, Jiang J, Xu C, Kang J, Xiao L, et al. Endogenous miRNA sponge lincRNA-RoR regulates Oct4, Nanog, and Sox2 in human embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Dev Cell. 2013;25:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du Q, Wang K, Zou C, Xu C, Li WX. The PILNCR1-miR399 regulatory module is important for low phosphate tolerance in maize. Plant Physiol. 2018;177:1743–1753. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu XW, Zhou XH, Wang RR, Peng WL, An Y, Chen LL. Functional analysis of long intergenic non-coding RNAs in phosphate-starved rice using competing endogenous RNA network. Sci Rep. 2016;6(January):1–12. doi: 10.1038/srep20715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnable PS, Ware D, Fulton RS, Stein JC, Wei F, Pasternak S, et al. The B73 maize genome: Complexity, diversity, and dynamics. Science (80- ) 2009;326:1112–1115. doi: 10.1126/science.1178534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiao Y, Peluso P, Shi J, Liang T, Stitzer MC, Wang B, et al. Improved maize reference genome with single-molecule technologies. Nature. 2017;546:524–527. doi: 10.1038/nature22971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards AO, Ritter R, Abel KJ, Manning A, Panhuysen C, Farrer LA. Complement factor H polymorphism and age-related macular degeneration. Science (80- ) 2005;308:421–424. doi: 10.1126/science.1110189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mao H, Wang H, Liu S, Li Z, Yang X, Yan J, et al. A transposable element in a NAC gene is associated with drought tolerance in maize seedlings. Nat Commun. 2015;6:1–13. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pace J, Gardner C, Romay C, Ganapathysubramanian BL, Lübberstedt T. Genome-wide association analysis of seedling root development in maize (Zea mays L.). BMC Genomics. 2015;16;1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Sitonik C, Suresh LM, Beyene Y, Olsen MS, Makumbi D, Oliver K, et al. Genetic architecture of maize chlorotic mottle virus and maize lethal necrosis through GWAS, linkage analysis and genomic prediction in tropical maize germplasm. Theor Appl Genet. 2019;132:2381–2399. doi: 10.1007/s00122-019-03360-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo B, Ma P, Nie Z, Zhang X, He X, Ding X, et al. Metabolite profiling and genome-wide association studies reveal response mechanisms of phosphorus deficiency in maize seedling. Plant J. 2019;97:947–969. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mu X, Chen Q, Chen F, Yuan L, Mi G. A RNA-seq analysis of the response of photosynthetic system to low nitrogen supply in maize leaf. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1–12. doi: 10.3390/ijms18091811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo B, Tang H, Liu H, Shunzong S, Zhang S, Wu L, et al. Mining for low-nitrogen tolerance genes by integrating meta-analysis and large-scale gene expression data from maize. Euphytica. 2015;206:117–131. doi: 10.1007/s10681-015-1481-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zanin L, Zamboni A, Monte R, Tomasi N, Varanini Z, Cesco S, et al. Transcriptomic analysis highlights reciprocal interactions of urea and nitrate for nitrogen acquisition by maize roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015;56:532–548. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He X, Ma H, Zhao X, Nie S, Li Y, Zhang Z, et al. Comparative RNA-Seq analysis reveals that regulatory network of maize root development controls the expression of genes in response to N stress. PLoS One. 2016;11:1–24. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang N, Gibon Y, Wallace JG, Lepak N, Li P, Dedow L, et al. Genome-wide association of carbon and nitrogen metabolism in the maize nested association mapping population. Plant Physiol. 2015;168:575–583. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stelpflug SC, Sekhon RS, Vaillancourt B, Hirsch CN, Buell CR, de Leon N, et al. An expanded maize gene expression atlas based on RNA sequencing and its use to explore root development. Plant Genome. 2016;9:1. doi: 10.3835/plantgenome2015.04.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Konishi N, Ishiyama K, Beier MP, Inoue E, Kanno K, Yamaya T, et al. Contributions of two cytosolic glutamine synthetase isozymes to ammonium assimilation in Arabidopsis roots. J Exp Bot. 2017;68:613–625. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Konishi N, Saito M, Imagawa F, Kanno K, Yamaya T, Kojima S. Cytosolic glutamine Synthetase Isozymes play redundant roles in ammonium assimilation under low-ammonium conditions in roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018;59:601–613. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcy014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilusz JE, Sunwoo H, Spector DL. Long noncoding RNAs: functional surprises from the RNA world. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1494–1504. doi: 10.1101/gad.1800909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L, Eichten SR, Shimizu R, Petsch K, Yeh CT, Wu W, et al. Genome-wide discovery and characterization of maize long non-coding RNAs. Genome Biol. 2014;15:1–15. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-1-r1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu J, Wang H, Chua NH. Long noncoding RNA transcriptome of plants. Plant Biotechnol J. 2015;13:319–328. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alonso-Peral MM, Li J, Li Y, Allen RS, Schnippenkoetter W, Ohms S, et al. The MicroRNA159-regulated GAMYB-like genes inhibit growth and promote programmed cell death in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010;154:757–771. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.160630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reyes JL, Chua NH. ABA induction of miR159 controls transcript levels of two MYB factors during Arabidopsis seed germination. Plant J. 2007;49:592–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y, Alonso-Peral M, Wong G, Wang MB, Millar AA. Ubiquitous miR159 repression of MYB33/65 in Arabidopsis rosettes is robust and is not perturbed by a wide range of stresses. BMC Plant Biol. 2016;16:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12870-016-0867-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nie Z, Ren Z, Wang L, Su S, Wei X, Zhang X, et al. Genome-wide identification of microRNAs responding to early stages of phosphate deficiency in maize. Physiol Plant. 2016;157:161–174. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fang Y, Xie K, Xiong L. Conserved miR164-targeted NAC genes negatively regulate drought resistance in rice. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:2119–2135. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu Z, Zhong S, Li X, Li W, Rothstein SJ, Zhang S, et al. Genome-wide identification of microRNAs in response to low nitrate availability in maize leaves and roots. PLoS One. 2011;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Jun W, Junhong Z, Menghui H, Minhui Z, Zaikang T. Expression analysis of miR164 and its target gene NAC1 in response to low nitrate availability in Betula luminifera. Yi Chuan. 2016;38:155–162. doi: 10.16288/j.yczz.15-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cortleven A, Marg I, Yamburenko MV, Schlicke H, Hill K, Grimm B, et al. Cytokinin regulates the etioplast-chloroplast transition through the two-component signaling system and activation of chloroplast-related genes. Plant Physiol. 2016;172:464–478. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang J, Fengler KA, Van Hemert JL, Gupta R, Mongar N, Sun J, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel stay-green QTL that increases yield in maize. Plant Biotechnol J. 2019;17:2272–2285. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gong C, Li Z, Ramanujan K, Clay I, Zhang Y, Lemire-Brachat S, et al. A long non-coding RNA, LncMyoD, regulates skeletal muscle differentiation by blocking IMP2-mediated mRNA translation. Dev Cell. 2015;34:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wen Z, Tan R, Zhang S, Collins PJ, Yuan J, Du W, et al. Integrating GWAS and gene expression data for functional characterization of resistance to white mould in soya bean. Plant Biotechnol J. 2018;16:1825–1835. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pace J, Gardner C, Romay C, Ganapathysubramanian B, Lübberstedt T. Genome-wide association analysis of seedling root development in maize (Zea mays L.). BMC Genomics. 2015;16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Zhu J, Kaeppler SM, Lynch JP. Mapping of QTLs for lateral root branching and length in maize (Zea mays L.) under differential phosphorus supply. Theor Appl Genet. 2005;111:688–695. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-2051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li P, Chen F, Cai H, Liu J, Pan Q, Liu Z, et al. A genetic relationship between nitrogen use efficiency and seedling root traits in maize as revealed by QTL analysis. J Exp Bot. 2015;66:3175–3188. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qin T, Zhao H, Cui P, Albesher N, Xionga L. A nucleus-localized long non-coding rna enhances drought and salt stress tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2017;175:1321–1336. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.00574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang X, Zhang H, Li L, Lan H, Ren Z, Liu D, et al. Characterizing the population structure and genetic diversity of maize breeding germplasm in Southwest China using genome-wide SNP markers. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3041-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guttman M, Garber M, Levin JZ, Donaghey J, Robinson J, Adiconis X, et al. Erratum: Ab initio reconstruction of cell type-specific transcriptomes in mouse reveals the conserved multi-exonic structure of lincRNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:503–510. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, Van Baren MJ, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kong L, Zhang Y, Ye ZQ, Liu XQ, Zhao SQ, Wei L, et al. CPC: Assess the protein-coding potential of transcripts using sequence features and support vector machine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;345–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Bateman A, Coin L, Durbin R, Finn RD, Hollich V, Griffiths-Jones S, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(DATABASE ISS):138–141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burge SW, Daub J, Eberhardt R, Tate J, Barquist L, Nawrocki EP, et al. Rfam 11.0: 10 years of RNA families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:226–232. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Friedländer MR, MacKowiak SD, Li N, Chen W, Rajewsky N. MiRDeep2 accurately identifies known and hundreds of novel microRNA genes in seven animal clades. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:37–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]