Abstract

Infection by SARS-CoV-2 virus ranges from asymptomatic to severe and sometimes fatal disease, most frequently the result of acute lung injury. The role of imaging has evolved during the pandemic, initially with CT as alternative and possibly superior test compared to RT-PCR, to a more limited role based on specific indications. Several classification and reporting schemes were developed for chest imaging early during the pandemic for patients with suspected COVID-19 to aid in triage when the availability of RT-PCR testing was limited and its performance unclear. Interobserver agreement for categories with findings typical of COVID-19 and those suggesting an alternative diagnosis is high across multiple studies. Furthermore, some studies looking at the extent of lung involvement on chest radiography and CT showed correlations with critical illness and need for mechanical ventilation. In addition to pulmonary manifestations, cardiovascular complications such as thromboembolism and myocarditis have been ascribed to COVID-19, sometimes contributing to neurologic and abdominal manifestations. Finally, artificial intelligence has shown promise in both diagnosis and prognosis of COVID-19 pneumonia both with respect to radiography and CT.

Summary

Since the initial reports on imaging manifestations of COVID-19 were first published in early 2020, much has been learned. Many classification systems for reporting imaging studies have been developed based on established characteristic imaging findings. With improved performance and access to RT-PCR testing, chest imaging is only indicated for patients with more severe disease or risk for worsening respiratory status. Vascular and cardiac complications of COVID-19 have been recognized, and AI applications for diagnosis and prognosis have been developed.

Essentials

■ The chest CT and CXR findings of COVID-19 pneumonia and the evolution of findings over time are well described. An organizing pneumonia pattern of lung injury is most common with some patients developing a pattern of diffuse alveolar damage. Patients with few or no symptoms may have normal imaging.

■ Extent of CXR and CT findings correlates with a variety of clinical indicators and severity of clinical course. However, imaging alone is insufficient to determine outcome.

■ Classification systems of CT findings related to COVID-19 have high interobserver agreement across levels of experience. Performance will depend on the local prevalence of COVID-19, and their role greatly depends on availability of RT-PCR testing.

■ AI has shown promise in both diagnosis and prognosis of COVID-19. Larger datasets and prospective studies are needed to assess performance and generalizability.

■ Cardiovascular complications of COVID-19 include thromboembolic disease, myocarditis, and MIS-C with coronary artery aneurysms.

■ Abdominal complications of COVID-19 may be the consequence of cardiovascular effects or critical illness rather than direct abdominal organ infection.

■ Neurologic complications of COVID-19 are not well defined and likely are the result of the cardiovascular effects and not direct CNS infection.

Introduction

Since the first imaging summaries of coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19), the disease caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, were published (1, 2), much has been learned about the clinical and radiologic manifestations of COVID-19. As it has evolved from a disease isolated in the Hubei Province of China to a global pandemic resulting in over two million deaths worldwide, larger and more comprehensive studies have been published, the physiological and biological heterogeneity of the disease has been explored, and extrathoracic manifestations of COVID-19 have been reported. In this review, we aim to summarize what is known about COVID-19 with respect to imaging as well as state what is not yet known.

Indications for Imaging in COVID-19

The clinical indications for imaging, specifically chest radiography (CXR) and chest computed tomography (CT), have evolved since the initial discovery of disease in Wuhan, China and since the World Health Organization (WHO) officially characterized COVID-19 as a pandemic on March 11, 2020. While some early proponents particularly in China advocated for routine imaging in diagnosis of suspected COVID-19 pneumonia, others particularly in the United States and Europe proposed a much more conservative approach (3). Societies such as the American College of Radiology (ACR) (4) and the Society of Thoracic Radiology (STR) and American Society of Emergency Radiology (5) recommended against the use of routine imaging, particularly CT, as a first-line diagnostic test.

Experts felt that the value of CT was limited because the diagnosis is primarily based on nucleic acid testing, concern that frequent CT increases potential for infection transmission to other patients and health care staff, the CT findings of COVID-19 overlap with those of other causes of acute lung injury or can even be normal, and results from CT infrequently alter disease management (3). Ultimately, the precise role of imaging remains somewhat controversial and varies based on country and institution.

In April 2020, the Fleischner Society published a multinational consensus statement to offer guidance to clinicians on the use of thoracic imaging across a spectrum of healthcare environments and scenarios (6). The statement structure is centered around three clinical scenarios of patients with known or suspected COVID-19 infection with varying severities of illness (mild, moderate to severe, and moderate to severe in a resource constrained environment). Based on expert opinions of panel members, recommendations were issued including: no indication for routine imaging as a screening test for COVID-19 in asymptomatic individuals, no indication for daily CXR in stable intubated patients with COVID-19, and CT is indicated in patients with functional impairment, hypoxemia, or both after recovery from infection.

Imaging Features of COVID-19 on Chest Radiography and CT

Chest imaging findings of SARS-CoV-2 infection overlap with or mimic other infections, including those caused by other human coronaviruses (SARS, MERS), H1N1 and other influenza virotypes, as well as acute lung injuries from drug reactions and connective tissue diseases (7). Given that the outbreak heightened during the influenza season in many regions, this further limited the specificity of CXR and CT for diagnosis.

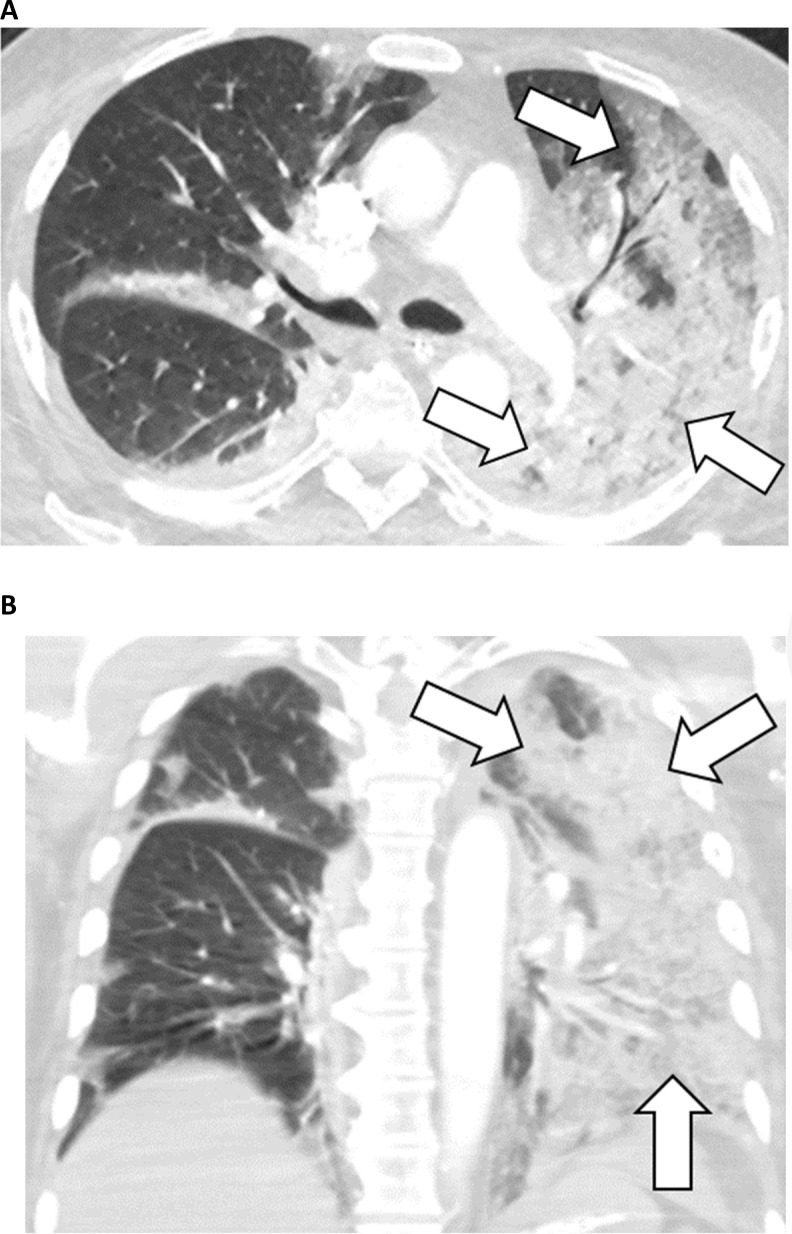

Findings of COVID-19 on CXR vary, ranging from normal in the early stages of disease to unilateral or bilateral lung opacities, sometimes with a basilar and strikingly peripheral distribution (Fig. 1) (7, 8). Early research reported a relatively low sensitivity (69%) for the diagnosis of COVID-19 on baseline CXR. Although underlying comorbidities such as chronic lung disease or congestive heart failure may confound CXR interpretation, studies have shown that many of the hallmark chest CT findings are apparent on CXR (8-10).

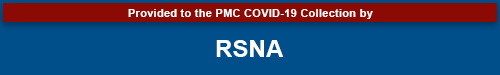

Figure 1:

37-year-old female with COVID-19 presenting with fever, cough, nausea, and diarrhea for one week. A, Posteroanterior chest radiograph shows mild, ill-defined pulmonary opacities in the periphery of the lungs bilaterally (arrows). B, C, Coronal unenhanced CT images of the chest show corresponding peripheral ground-glass opacities bilaterally, some with a rounded morphology.

The typical chest CT appearance of COVID-19 pneumonia is bilateral peripheral opacities with a lower lung distribution (Fig. 2). The opacities are usually ground-glass opacity (GGO) sometimes with areas of consolidation and are often nodular or mass-like, thereby resembling an organizing pneumonia pattern (11, 12). Additional imaging patterns resembling organizing pneumonia include a perilobular pattern of opacification and a “reverse halo” sign, defined as a focal, rounded area of GGO surrounded by a ring or arc of denser consolidation (Figs. 3 and 4). Diffuse GGO which can mimic other infections, drug toxicities, and inhalational lung disease has also been reported (12). Although prototypical CT features of COVID-19 pneumonia are well described, in clinical practice, many patients will have some but not all the imaging manifestations. For example, the opacities may be unilateral but have a rounded morphology. Alternatively, the opacities may have an upper lobe predominance but still retain a peripheral or subpleural distribution.

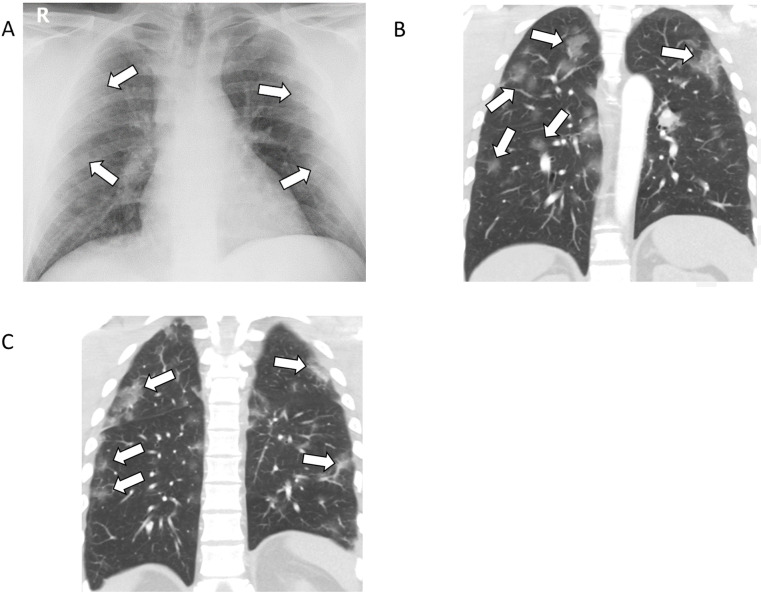

Figure 2:

77-year-old male with COVID-19 presenting with five days of fever and cough. A, B, Axial and, C, coronal unenhanced thin-section chest CT images show bilateral ground-glass opacities (arrows) in a predominately peripheral distribution, and many with a rounded morphology.

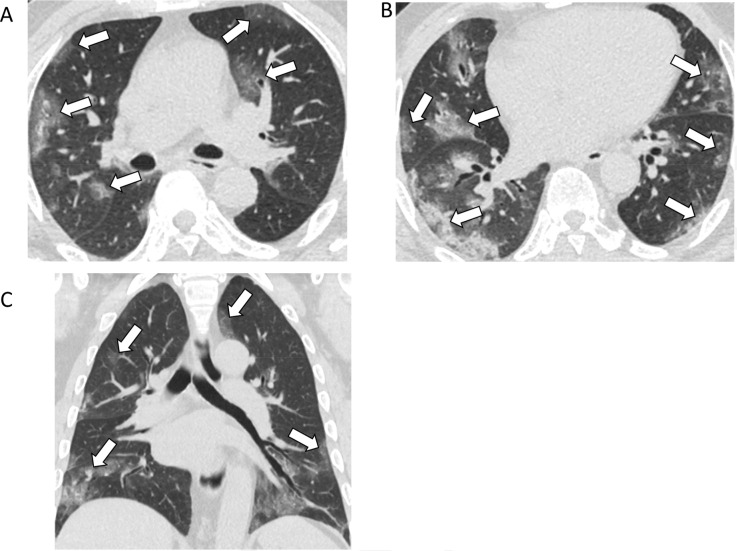

Figure 3:

57-year-old male with COVID-19 presenting with 4 days of cough. A, Axial and, B, sagittal unenhanced thin-section chest CT images show bilateral ground-glass opacities in a peripheral distribution in the left lung, some with a rounded morphology (arrowheads). There are also arcadelike opacities in the subpleural right lower lobe (arrow) indicative of a perilobular pattern of disease.

Figure 4:

72-year-old male with COVID-19 and history of heart failure presenting with 10 days of cough. A, Axial and sagittal, B, unenhanced thin-section chest CT images show peribronchial ground-glass opacities (arrowheads) as well as ground-glass opacity in the left lower lobe with a ring of denser consolidation (reverse halo sign) (arrow).

CT features which are indeterminate for COVID-19 have also been described and classified in guidelines such as the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) consensus statement on CT reporting (12). These include imaging findings which have been reported in COVID-19 but are not specific enough to arrive at a relatively confident radiological diagnosis. For example, diffuse or perihilar GGO with or without consolidation, or scattered non-rounded opacities can occur with a variety of other infectious and some noninfectious processes such as edema or alveolar hemorrhage (Fig. 3). Certain CT features are uncommonly seen in COVID-19 pneumonia including lobar or segmental consolidation without GGO, discrete small pulmonary nodules, pulmonary cavitation, septal thickening, pleural effusion, and pneumothorax. Interestingly, the rate of barotrauma in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 has been reported to be much more common that patients with other causes of acute respiratory distress syndrome (24% versus 11%) (13). A comprehensive review of the various scoring and assessment systems developed for CT lung findings is discussed in detail in a later section.

Change in COVID-19 Findings over Time on Chest Radiography and CT

While the presence of characteristic COVID-19 imaging findings is helpful in diagnosis and risk stratification, it is noteworthy that both CXR and chest CT may lack lung abnormalities in the earliest stages of infection, with rates of normal CT as high as 56% in patients imaged within two days of symptom onset (14). Therefore, a normal CXR and CT do not reliably exclude disease.

Pan et al. described four temporal stages of acute and subacute COVID-19 on CT, including an initial phase where abnormalities manifest as GGO, may be unilateral, and tend to lack the characteristic peripheral lung distribution (15). Patients often experience progression from day 5 to 8 when pulmonary opacities become more extensive and confluent with more common bilateral lung involvement (Fig.4). The peak stage occurs around 9 to 13 days and features more extensive consolidation, which parallels the evolution of acute lung injury (2, 14, 15). This dovetails with investigators who have found that abnormalities on CXR are most extensive 10 to 12 days after symptom onset (8). There is variation among patients, but beginning at about two weeks, many enter the absorption stage (16). During this period, consolidation may wane, and other manifestations absent in the earlier phases of acute infection such as linear opacities, a “reverse-halo” sign, and a “crazy-paving” pattern may emerge. During the first several weeks of infection, pleural effusions are uncommon, cavitation is rare, and pulmonary fibrosis is not expected.

Over weeks, COVID-19 pulmonary findings on both CXR and CT resolve or can evolve into a more structured and organized phase, in which case GGO and consolidation transform into more reticular opacities and may be associated with fibrosis, volume loss, architectural distortion, and traction bronchiectasis.

What role does severity of disease on CT play in disease evaluation?

Assessment of disease severity by imaging in COVID-19 may inform clinical decisions related to need for hospital admission, timing of intubation, patient course and prognosis, and therapeutic efficacy. CT may enable reproducible quantitative severity scoring and can be particularly helpful in detecting mild disease, characterizing longitudinal change, and assessing the extent of disease in the setting of baseline pulmonary abnormalities.

A variety of methods have been used to assess lung involvement at CT in COVID-19. Qualitative methods classify parenchymal disease as mild, moderate, or severe. Semiquantitative methods estimate lobar or zonal involvement by quartiles (0-25%, 26-49%, 50-75%, 76%-100%) (17), with <5% lobar involvement also sometimes used (18). Software-based quantitative methods, including those using machine learning, can be used to calculate the total lung involvement as well as the percentage of GGO and consolidation and may have higher accuracy than human semiquantitative estimates (19-21).

Several studies have shown correlations between extent of parenchymal involvement at CT and clinical assessment of COVID-19 disease severity as defined by parameters such as severity of symptoms, oxygenation status, and certain laboratory measures of infection and inflammation. Semiquantitative and quantitative studies have shown significantly higher CT severity scores for patients with severe and critical disease than for those with less severe disease (17, 22-25). For example, in one study of 189 inpatients, the average volume of lung involvement measured by semiautomated segmentation of parenchymal opacities on CT was higher in critically ill patients (38.5%) than in non-critically ill patients (5.8%), with a threshold of 23% distinguishing these two groups with 96% sensitivity and specificity (22). In another study of 78 patients, a semiquantitative total CT severity score ranging from 0 to 20 distinguished mild, moderate, and severe clinical disease with high accuracy (82.6% sensitivity and 100% specificity for a cutoff score of 7.5) and a high interclass correlation between readers (0.976) (17).

CT severity scores also show correlations with serum markers of disease severity. A study of 84 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 showed significant correlations of with lymphocyte count and percentage, neutrophil percentage, C-reactive protein and procalcitonin levels (all p<0.05) (26). Another semiquantitative study of 106 inpatients with COVID-19 pneumonia showed significant positive correlations between CT severity and levels of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 and interleukin-2R (27). Additional studies have observed similar correlations (22, 28, 29)

CT severity scoring may show promise for clinical triage and assessment of prognosis, and higher CT severity scores predict clinical outcomes in COVID-19 (29, 30). In a study of 572 hospitalized patients, 70% of patients with total lung involvement greater than 50% were admitted to the intensive care unit or died within seven days of a CT performed at admission, while these rates were lower for lung involvement of 26-50% (41%) and <25% (23%) (18). Semiquantitative CT severity scores of 18 or greater on a scale from 0-25 correlated with increased mortality risk in another study of 130 patients in the emergency department setting (HR 3.7, p=0.0348).

Semiquantitative CT severity scores of 18 or greater on a scale from 0-25 correlated with increased mortality risk in another study of 130 patients in the emergency department setting (HR 3.7, p=0.0348) (28). Higher semiquantitative total severity scores and multilobar involvement were associated with increased fatality risk in a study of 128 patients with COVID-19 hospitalized for observation; death was more common in patients with a CT severity score of 15 or greater (OR 53, p=0.003), and CT severity score was the only independent risk factor for mortality in a multivariate analysis that incorporated age and several inflammatory serum markers (30).

However, CT severity scores are just one of many clinical and laboratory parameters that correlate with patient prognosis (31). In addition, a significant percentage of patients with asymptomatic infection may have parenchymal involvement at CT that overlaps in severity with that of symptomatic patients (32), and CT severity scores of clinically severe cases of COVID-19 pneumonia may overlap with those of moderate clinical severity (30), underscoring limitations in drawing clinical conclusions from CT severity alone. Although initial evidence is promising, clinical studies of the usefulness of CT severity scoring in management of patients with COVID-19 are still awaited.

What role does severity of disease on chest radiography play in disease evaluation?

CXR is commonly used as the initial diagnostic imaging test to evaluate patients with suspected or known COVID-19. Several studies investigating the relationship of severity of lung abnormalities on CXR with disease severity have shown scores reflecting increased extent and intensity of lung opacities to be associated with more severe clinical manifestations, higher rates of ICU admission, and death (10, 33, 34). In one retrospective study of 338 young adults (median age 39 years), a CXR severity score ≥ 2 out of a maximum of 6 (OR 6.2) and obesity (OR 2.4) were independent predictors of hospital admission. Of those admitted to hospital, a CXR severity score ≥ 3 was an independent predictor of endotracheal intubation (10). Another study of 1157 subjects looked at a variety of clinical factors including radiologic assessment of lung edema (RALE) score found that with each unit increase of the RALE score, the hazard increased by 1.49 for ICU admission and 1.23 for death (33). A group from the Netherlands created a risk model from a retrospective study of 356 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 that included a 0-8 chest radiograph score based on 4 zones and severity of 0-2. Patients who required ICU admission or died had significantly higher radiograph scores (mean 4.4) than those who did not (mean 3.3), (p <0.01). Furthermore, bilateral lung involvement at presentation was present in 86% of patients with critical illness as compared to 73% without (p=0.06) (34).

Patients with COVID-19 and normal or near normal CXRs typically have a benign clinical course. In a retrospective study of 109 subjects with COVID-19 using a 72-point CXR severity score showed that a severity score < 5 between days 6-10 after onset of symptoms had a negative predictive value of 95.45 for supplemental oxygen requirement and 100.00 for ICU admission (35). A retrospective study of asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic 5621 males with COVID-19 of whom 1964 had CXRs showed normal results in 98%. Supplemental oxygen and inpatient treatment were only necessary for four (0.2%) (36). These studies support recommendations that imaging is not usually indicated for patients with COVID-19 who have minimal or no symptoms. Routine radiographic monitoring of stable patients with COVID-19, including those requiring mechanical ventilation, is not recommended (6).

Studies comparing the various scoring systems have not been performed, and each system has its own merits. In routine clinical practice, patients with COVID-19 and normal or minimal findings on CXR will likely have a benign clinical course whereas patients with more extensive lung opacities are much more likely to require supplemental oxygen, ICU admission, and mechanical ventilation.

What reporting systems have been found useful for conveying suspicion of COVID-19 at CT and radiography?

Early during the COVID-19 pandemic when access to accurate RT-PCR testing was limited, several reporting systems were proposed for reporting CXR and CT scans of patients with suspected COVID-19 in a high disease prevalence setting. These systems provide standardized language and diagnostic categories aiming to convey the likelihood of lung abnormalities on CT representing COVID-19. Reporting systems include the RSNA Expert Consensus Statement (Table 1) (12), CO-RADS developed by the Dutch Radiologic Society (Table 2) (37), British Society of Thoracic Imaging (Table 3) (38), COVID-RADS (Table 4) (39), and COVID-19 S (Table 5) (40). One study of the RSNA Expert Consensus Statement found excellent interobserver agreement among thoracic radiologists in a retrospective review of approximately 300 patients with suspected COVID-19 (41). In this study, Fleiss kappa for all observers was almost perfect for typical (0.815), atypical (0.806), and negative (0.962) COVID-19 categories (P <0.0001) and substantial (0.636) for indeterminate COVID-19 categories. A retrospective study of chest CT scans of 572 symptomatic patients (142 with RT-PCR confirmed COVID-19 and 430 without) showed moderate agreement for CO-RADS rating among all readers (Fleiss' k = 0.43 with a substantial agreement for CO-RADS 1 category (Fleiss' k = 0.61) and moderate agreement for CO-RADS 5 category (Fleiss' k = 0.60). CO-RADS score ≥ 4 was identified by ROC analysis as the optimal threshold with a cumulative area under the curve of 0.72, sensitivity 61%, and specificity 81% (42).

Table 1:

Summary of Radiologic Society of North America Expert Consensus Reporting System for COVID-19 (12)

Table 2:

Summary of CO-RADS Reporting System (37)

Table 3:

Summary of British Society of Thoracic Imaging (38)

Table 4:

COVID-RADS Summary (39)

Table 5:

COVID 19S (40)

Proposed CXR reporting language and categories include those of the British Society of Thoracic Imaging (43) and a multicenter US group (44) (Table 2). A retrospective study of the BSTI guidelines found substantial interobserver agreement (Fleiss' k = 0.61) for “classic” and “probable categories”. Agreement was fair for the “Indeterminate for COVID-19” (k = 0.23), and “Non-COVID-19” (k = 0.37) categories (45). The authors of this study suggest combining the latter two categories into a single “not classic of COVID-19” to improve interobserver agreement and to avoid labeling patients with COVID-19 as “Non-COVID-19”.

Despite routine use of CT as a triage tool early in the outbreak in China, the role of CT has been more limited elsewhere in the world, where use has been mostly limited to specific indications such as pulmonary embolism (PE) (6). With increased access to RT-PCR and faster results reporting, the prospective value of these classification systems in patients with COVID-19 is unclear. The positive predictive value of all these systems varies greatly with the prevalence of COVID-19 in the community. However, further investigation is warranted to evaluate the diagnostic performance of CT for patients not suspected clinically of having COVID-19 but who have highly suggestive CT findings (6, 46).

While each classification system is likely to be helpful in suggesting the presence or absence of COVID-19 when typical findings are present or absent, respectively, the value of any one system will vary depending on disease prevalence and access to and rapidity of RT-PCR. Radiologist experience may also play a role.

Why has CT detection vs. RT-PCR detection of COVID-19 been controversial?

The diagnosis of viral infection, including SARS-CoV-2, relies on RT-PCR test to identify genetic material in biological (47, 48). However, the availability of RT-PCR was limited in the first half of 2020 and for this reason CT was used for early triage and management of COVID-19 pneumonia. Because of this, the specific definition of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the early literature is unclear, with the CT definition and RT-PCR definitions complementary. Although RT-PCR is considered the reference standard for diagnosis SARS-CoV-2 infection, it is far from perfect.

RT-PCR is subject to false-negative results because its diagnostic performance can be influenced by multiple factors such as inadequate sampling and improper extraction of nucleic acids from biological materials, variations in the accuracies of different tests, or low initial or late viral load (49, 50). False negative CT scans have also been reported in 3%–56% of RT-PCR positive patients (14, 51, 52). CT signs of pneumonia represent on potential manifestation of COVID-19 severity and tend to develop later in the disease course, typically 6-11 days after infection (53).

Studies in symptomatic subjects reported higher sensitivity for CT as compared to RT-PCR (51, 53). It has been advocated that such findings could be due to several factors, particularly the inclusion of only patients with moderate to severe symptoms (54).

The interpretation of the RT-PCR/CT mismatch is difficult and is confounded by a variety of factors (55). In a large meta-analysis, the pooled sensitivity for CT was 94% (95% CI: 91%, 96%) and for RT-PCR 89% (95% CI: 81%, 94%) (56). In this study, lower sensitivity of CT was reported as a function of symptoms and disease severity, whereas these factors did not influence RT-PCR performance, underscoring that imaging is not meant for screening asymptomatic patients (6, 36).

The specificity of RT-PCR is optimal whereas the CT findings of COVID-19 pneumonia are far from pathognomonic. The systematic review from Cochrane Database reported substantial reduction of sensitivity and specificity in studies that included suspected cases. The chances of a positive CT result were 86% in patients with a SARS-CoV-2 infection and 82% in patients without. Therefore, the specificity of CT is too weak to justify its use for the diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia (57).

The accuracy of imaging tests in diagnosing COVID-19 and in any clinical setting is influenced by the prevalence of both COVID-19 and comparable viral pneumonias as well as other clinico-radiological mimickers. This issue was witnessed in regions with low rate of COVID-19 (<10%) where the positive predictive value (PPV) of chest CT was trivial (56).

What is the Role of Artificial Intelligence in COVID-19 Evaluation?

Artificial intelligence (AI) based on imaging has a potentially important role in the diagnosis, disease quantification, severity assessment, and prognosis of COVID-19 pneumonia. AI has been proposed as a tool to reduce radiologists’ workload, streamline workflow, improve diagnostic accuracy, and facilitate resource allocation.

Published studies have focused on using CT and CXR to distinguish COVID-19 from other types of pneumonia and predict disease severity (Table 7). Li et al. developed a fully automatic framework on 4352 chest CT scans from 3322 patients to distinguish COVID-19 pneumonia from community-acquired pneumonia and other lung conditions (58). The COVID-19 detection neural network (COVNet) achieved a per-scan sensitivity of 90% (95% CI: 83-94%) and specificity of 96% (95% CI: 93-98%) in detecting COVID-19 on the test set with an ROC-AUC of 0.96. Another study by Bai et al. used CT scans of 1186 patients (521 COVID-19 cases and 665 non-COVID-19 pneumonia cases) to distinguish COVID-19 from pneumonia of other lung disease (59). On independent testing, the model achieved an accuracy of 87% (95% CI: 82-90%), sensitivity of 89% (95% CI: 81-94%), and specificity of 86% (95% CI: 80-90%). Furthermore, the authors demonstrated the ability of AI to improve radiologists’ performance. In another study using 905 patients from Chinese hospitals, Mei et al. developed AI algorithms to integrate chest CT findings with clinical symptoms, exposure history, and laboratory testing for rapid diagnosis of patients with COVID-19 (60). In a test set of 279 patients, the AI system achieved an AUC of 0.92 and had equal sensitivity compared to a senior thoracic radiologist. In addition, the AI system improved the detection of patients who were positive for COVID-19 via RT-PCR who presented with normal CT scans, correctly identifying 17 of 25 (68%) patients.

Table 7:

Summary of AI Studies for COVID-19

Table 6:

Reporting Systems for Chest Radiography

Zhang et al. performed the largest and most comprehensive study using AI based on 6752 chest CT scans from 4154 patients to diagnose COVID-19 pneumonia and predict patient prognosis (61). To validate the AI system for distinguishing COVID-19 pneumonia from community acquired pneumonia and normal controls, the authors conducted three prospective pilot studies in China and externally tested the model on a cohort of patients from Ecuador. The AI system achieved stable and good results with an overall performance superior to that of junior radiologists and comparable to more experienced radiologists.

Several studies provided proof-of-concept for deep learning-based triage of COVID-19 cases using CXR. For example, Murphy et al. evaluated the performance of an AI system (CAD4COVID-Xray) trained on 24,678 CXR images and compared performance to that of six radiologists on a test set of 454 CXR images of patients suspected for COVID-19 pneumonia (62). The AI system correctly classified CXR images as COVID-19 pneumonia with an AUC of 0.81 and significantly outperformed each reader at their highest possible sensitivities. A summary of the important studies published using AI based on imaging is shown in Table 7. Another study by Li et al. developed a Siamese neural network-based severity score that correlated with radiologist-annotated pulmonary disease severity scores assigned to CXRs in the internal and external test sets (r=0.86 [95% CI 0.80-0.90]) and (r=0.86 [95% CI: 0.79-9.90]), respectively (63). In patients not intubated on the admission CXR, the severity score predicted subsequent intubation or death within three days of hospital admission with an AUC of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.75-0.85). Bai et al. investigated the performance of an AI system that combined CXR features and clinical data to predict future critical events of ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, or death for patients with COVID-19 (Bai unpublished).

In summary, AI based on chest CT and CXR have demonstrated potential in both diagnosis and prognosis of COVID-19 pneumonia. However, to integrate these AI algorithms into routine clinical care in the fight against pandemic, we advocate the following: first, open-source datasets and code are strongly advocated for the broader community to train, test, and evaluate the performance of the machine learning classifiers. This is exemplified by the recent publication of the RSNA International COVID-19 Open Annotated Radiology Database (RICORD) (64); second, true generalizability will need to be assessed in real-time in a prospective study design. If one or a few of these models can be validated prospectively, they could inform treatment algorithms and guidelines customized for patients along the spectrum of COVID-19 ranging from mild symptoms to death and pave the way for a bigger role of AI-based imaging in COVID-19 resurgence and future pandemics.

What are the pulmonary vascular effects of COVID-19?

Pulmonary macrovascular and microvascular manifestations of COVID-19, initially under-recognized, have received increasing attention in the radiology, clinical, and pathology literature. Our current understanding reflects intensive study predominantly focused on patients with severe disease and limited by marked paucity of data regarding asymptomatic patients and those with mild infection. The highest level of evidence, prospective randomized trials with outcomes data, is also presently lacking.

Diagnostic imaging pathways have evolved, often radically, during the COVID-19 pandemic. These changes vary widely in different countries, regions, and institutions reflecting differences in guidelines, availability of resources, prevalence of COVID-19, and institutional expertise. Variability in data resulting from differences in diagnostic imaging use in different populations during the pandemic and compared with pre-pandemic practice remains an analytic dilemma. This is particularly true for acute PE imaging, with performance characteristics that have been shown to be greatly impacted by disease prevalence (pretest probability) and diagnostic modality (65).

Although CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) remains a dominant diagnostic imaging test for acute PE, point of care ultrasound is commonly performed in critically ill patients in the ICU (66). COVID-19 patients with elevated D-dimer along with signs of right heart strain may be clinically diagnosed with PE. Change in utilization of the ventilation-perfusion lung scan during COVID-19 has received attention due to infection control concerns related to the risks of leakage of aerosolized ventilation agent. Some centers have been performing perfusion only scans for stable COVID-19 patients with normal CXR (67).

The preponderance of evidence suggests that there is a real increased incidence of acute PE and other thrombotic events among patients with COVID-19. Helms et al. described a prospective cohort of 150 COVID-19 patients (81% men, mean age 63 years) with ARDS from four ICUs in France (68). Primary outcome was any thrombotic event. There were 64 thrombotic complications diagnosed by CT, mainly PE. When compared with a historical matched prospective non-COVID-19 ARDS cohort, the COVID-19 patients had more PE, 11.7% vs 2.1% (p = 0.008), despite prophylactic or therapeutic anticoagulation in all patients.

Kaminetzky et al. described a retrospective cohort of 62 patients (65% men, mean age 58 years) with COVID-19 who underwent CTPA and 62 matched patients from the pre-COVID-19 era from a single New York institution (69). They found a higher CTPA positivity rate for patients with COVID-19 as compared to the non-COVID-19 cohort (37.1% vs. 14.5%). One observational cohort study of 3334 subjects (60% men, median age 64 years) hospitalized COVID-19 patients from the same New York institution found a 16% rate of thrombotic complications, including acute PE in 3.2% (n=106) (70). Other series have described acute PE prevalence on CTPA in hospitalized COVID-19 patients ranging from 6.4%-30% [6.4% (71), 18% (72), 23% (73), 30% (74)].

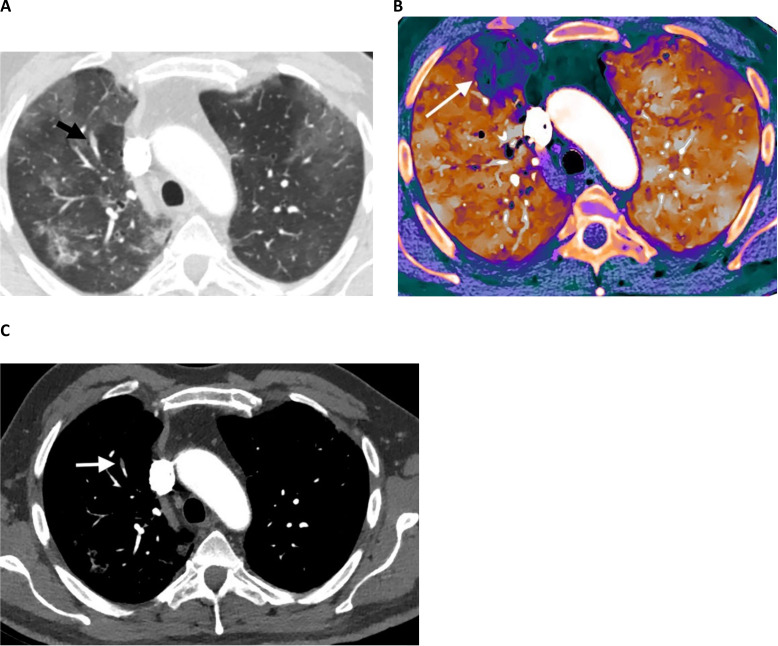

The dilated vessel sign was reported in the lungs early during the pandemic on unenhanced chest CT with some debate regarding its etiology. Possible explanations include small PEs, in situ pulmonary vascular thrombosis, and increased pulmonary blood flow (Fig. 5). There are imaging and pathological data to support both processes, and additional study will be useful for further elucidation (75, 76).

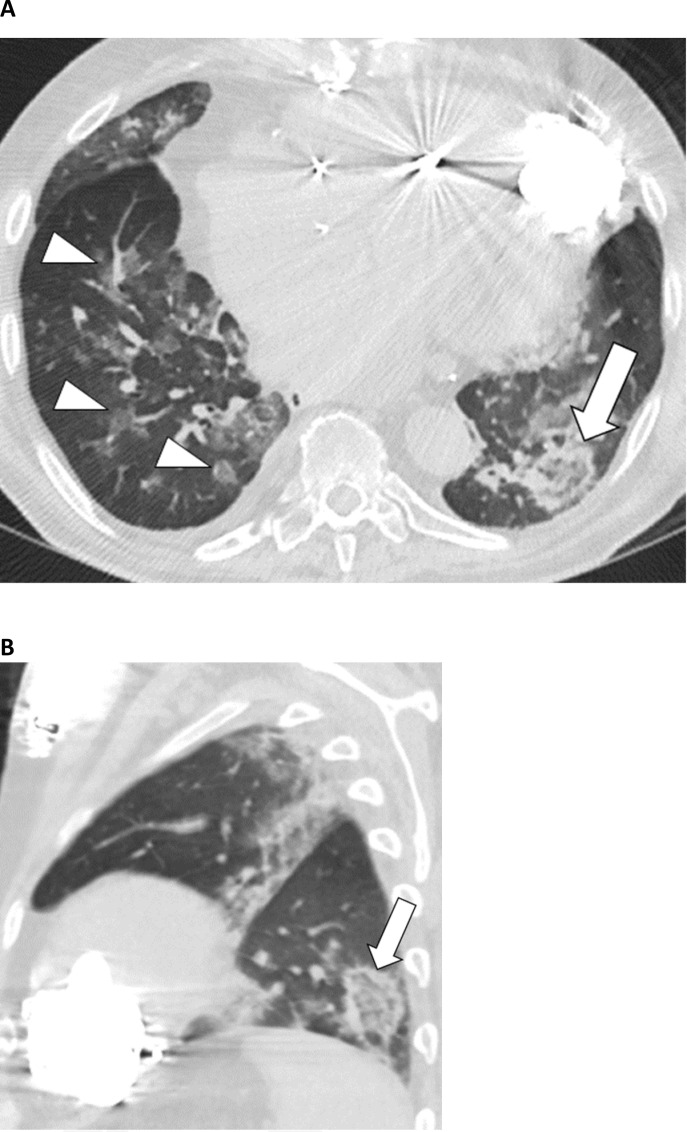

Figure 5:

74-year-old male with COVID-19 presenting with seven days of cough. A, Axial and, B, coronal contrast-enhanced, thin-section chest CT images show diffuse GGO and consolidation in the left lung (arrows). These findings would be classified as “indeterminate” per the RSNA, BSTI, and COVID-19S assessment systems and as “Equivocal / Unsure” per CO-RADS.

In situ thrombosis of the pulmonary arteries in the lungs of COVID-19 patients is supported by cohort studies that demonstrated clots disproportionately located in the distal pulmonary vasculature along with lower-than-expected rates of concurrent deep vein thrombosis. Van Dam et al. in a retrospective cohort comparing positive CTPA imaging characteristics in 23 COVID-19 patients with 100 controls (77). Thrombotic lesions affected COVID-19-involved lung in all cases with a lower thrombus burden and lower rate of proximal pulmonary artery involvement compared to controls. Cavagna et al. reported similar results in an Italian population of 101 COVID-19 patients who underwent CTPA, positive in 41%. Pulmonary emboli or thrombi were present in the segmental and more distal vessels in greater than 90% of patients, representing the most proximal clot in 52% (22/41); deep vein thrombosis prevalence was only 12% (5/41) (78).

Autopsy studies have shown various pulmonary vascular abnormalities in patients who died of COVID-19. Although representing only the most severe (fatal) disease spectrum, they shed light on the pathophysiology and imaging findings. Lax et al. in a prospective series found thrombosis of small to mid-sized pulmonary arteries in all patients, none clinically suspected and despite prophylactic anticoagulation in 91% (10/11) (79). Fox et al. found a dominant pattern of diffuse small vessel thrombosis associated with inflammation and hemorrhage in addition to diffuse alveolar damage (80). Ackermann et al. found distinctive vascular features including severe endothelial injury with intracellular virus and thrombosis with microangiopathy throughout the pulmonary vascular bed, including alveolar capillary microthrombi. They also found extensive new vessel growth predominantly via intussusceptive angiogenesis, which occurs in response to increased blood flow, vascular dilation, and resultant mural wall stress (81, 82).

Lang et al. described pulmonary vessel dilation and increased perfusion proximal and distal to lung opacities in COVID-19 patients without PE (83). They proposed that regional vasodilation rather than the normal vasoconstriction due to a dysfunctional diffuse inflammatory process. This paradoxical shunting to the hypoventilated regions may, in part, explain the poorly understood clinical phenomenon of the “happy hypoxic”- a well appearing profoundly hypoxic COVID-19 patient.

In severe COVID-19, it has been difficult to assess the contribution of PE to mortality in those patients who may have multiorgan failure, ARDS, and thromboses in different vessels, among other complexities. However, with increased recognition of thrombotic complications and issuing of anticoagulation recommendations (84), there is an evidence base suggesting that anticoagulation is associated with improved survival (85). The National Institute of Public Health of the Netherlands recommends prophylactic low molecular with heparin for all hospitalized COVID-19 patients and monitoring of D-dimer levels to guide the use of prophylactic anticoagulation and the decision to image for deep vein thrombosis or PE, in concert with the clinical picture and YEARS criteria (84).

Cardiac manifestations

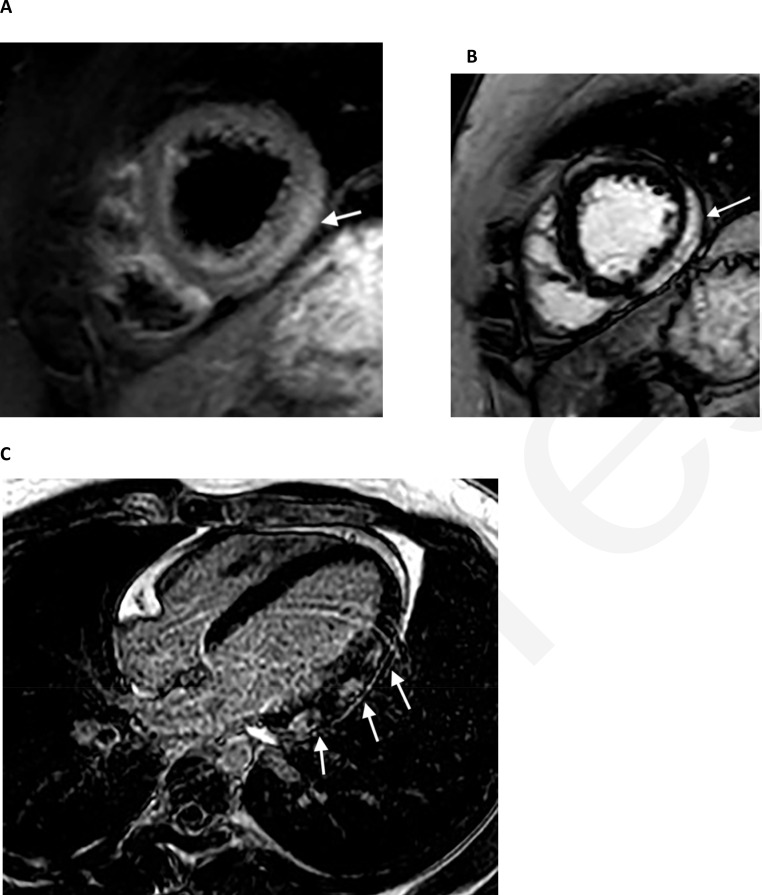

Cardiac manifestations associated with COVID-19 include myocarditis, acute myocardial infarction (MI), and coronary artery aneurysms, which have received particular attention as a component of the recently described multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) and can be associated with myocarditis.

Viral infection is the most common cause of myocarditis, while cardiac injury as a component of the inflammatory response commonly occurs in severely ill patients. Active investigation is in progress to determine whether myocarditis incidence is elevated compared with other viral infections. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the reference standard for myocarditis, and although available data are limited, its exquisite tissue characterization has shown abnormalities (Fig. 6) in most imaged COVID-19 patients, both symptomatic and asymptomatic. Puntmann et al. in a prospective observational cohort performed cardiac MRI (CMR) on 100 patients recovering from COVID-19 (33% hospitalized), 50 healthy controls, and 57 risk-factor matched patients (86). A median 71 days after COVID-19 diagnosis 78% of CMRs were abnormal with elevated native T1 and T2 values, lower left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction, higher LV volumes, late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) in 32% and pericardial enhancement in 22%. Huong et al. described a series of 26 symptomatic COVID-19 patients who underwent CMR compared with 20 controls; 58% of COVID-19 patients (15/26) had MR abnormalities including edema in 54% (14), LGE in 31% (8); additional parameters were abnormal only among this positive subset (87). Rajpal et al. described CMR findings for 26 competitive college athletes [54% (14/26) asymptomatic] with COVID-19 imaged 11-53 days after diagnosis (88). All had normal ventricular volumes and function, 45% (12/26) had LGE, 4 met modified Lake Louise Criteria for myocarditis with myocardial edema (two with pericardial effusion).

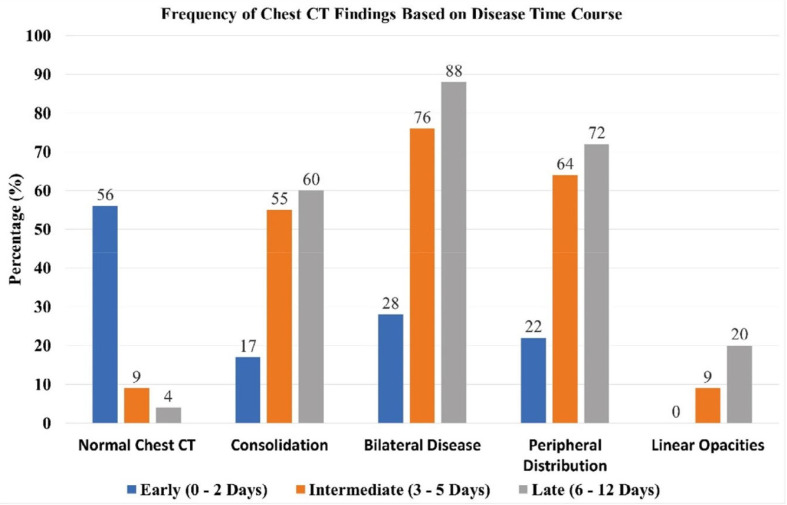

Figure 6:

Frequency of selected chest CT findings as a function of time course from symptom onset (Adapted from Reference 14).

Figure 7:

59-year-old male with COVID-19, diabetes, hypertension, and coronary artery disease who presented with shortness of breath and fever. A, Contrast-enhanced CT angiography image (lung window settings) shows bilateral peripheral GGO. A dilated vessel (arrow) is present in the anterior right upper lobe within a region of lung opacity. B, Spectral contrast-enhanced CT pulmonary blood volume map shows a subsegmental perfusion defect in the anterior right upper lobe, in the territory of the dilated vessel. C, Contrast-enhanced CT angiography image (vascular window settings) shows an isolated subsegmental filling defect corresponding to the dilated vessel in a subsegmental anterior right upper lobe pulmonary artery consistent with acute pulmonary embolism or in situ thrombus.

Figure 8:

22-year-old male with COVID-19, shortness of breath, and chest pain. Cardiac MRI showed mildly reduced left ventricular systolic function with an ejection fraction of 47%. A, T2 short axis image through the apical segments demonstrates subepicardial edema (high signal, arrow) along the lateral wall. B, C, There is corresponding subepicardial lateral wall late gadolinium enhancement on short axis (B, arrow) and 4-chamber (C, arrows) images.

The overall incidence of myocardial infarction (MI) in COVID-19 is uncertain, but Bilalogu et al. reported MI in 8.9% of 3334 hospitalized COVID-19 patients (70). Proposed mechanisms include direct viral infection of coronary endothelium via ACE2 receptors, microangiopathy and thrombosis, plaque instability related to severe inflammatory response, and demand ischemia. Catheterization with percutaneous coronary intervention remains standard treatment for ST-elevation MI, but utilization has been reduced during the COVID-19 pandemic (89, 90). CT coronary angiography (CCTA) has a role in low to intermediate risk chest pain patients to assess the patency of the epicardial coronary arteries (89, 90).

In multisystem inflammatory system in children (MIS-C), coronary artery aneurysms have been described in close to 10% of hospitalized children (91). CCTA has the capacity to exquisitely demonstrate coronary artery aneurysms, particularly useful for children with limited echocardiographic windows.

Are there abdominal findings in COVID-19?

While diagnostic imaging in COVID-19 has centered on the lungs and pulmonary manifestations of the disease, abdominal organs are also affected, most notably the liver, biliary tree, gastrointestinal tract, and abdominal vasculature (92). The affinity of SARS-CoV-2 for cells with surface expression of receptors for angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) forms a basis for preferential COVID-19 involvement of abdominal organs as well as the lungs (93). Within the abdomen, ACE2 expression predominates in small bowl enterocytes, vascular endothelium, and biliary epithelium (92, 94).

Thromboembolic complications of COVID-19 have been reported across a variety of vascular beds and attributed to both microvascular inflammation and coagulopathy, leading to thrombosis and embolization (94-96). Most abdominopelvic manifestations are associated with microvascular involvement and thus manifest as end-organ ischemia or infarction involving bowel, spleen, kidneys, and liver (92, 96) with rare reports of COVID-19 associated superior mesenteric artery or portal vein thrombosis (94, 97).

Because the use of abdominal imaging in association with COVID-19 is substantially less frequent than thoracic manifestations, the evidence base is limited to small case series and case reports with limited data to support SARS-CoV-2 causation versus association.

Abdominal pain and sepsis are the most common indication for abdominal imaging in COVID-19. Among patients hospitalized with COVID-19, cross-sectional abdominal imaging has been reported in 17% with equal use of ultrasonography (US) and CT and is significantly more likely among patients admitted to the ICU (92).

Common findings observed on abdominal CT scans include colorectal and small bowel wall thickening, fluid-filled colon, and infarction of the kidney, spleen, or liver. Pneumatosis and portal venous gas without vascular involvement may be associated with ischemic enteritis and necrosis or pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis (98). Direct viral infection, small vessel thrombosis, and nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia have been proposed as causes for the spectrum of bowel findings in COVID-19 (92).

Right upper abdominal US most commonly reveals signs of cholestasis, particularly gallbladder distension and sludge, and fatty liver (92). Acute cholecystitis, which can be acalculous, including a case of ischemic, gangrenous cholecystitis, has been reported in COVID-19 (99-101). In the latter instance, the gallbladder specimen lacked direct evidence of viral shedding, but medium vessel thrombosis, endothelial overexpression, and invasion by macrophages and T-cells supported a diagnosis of gallbladder vasculitis.

Serological evidence of pancreatic injury was reported in nine of 52 of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 pneumonia (102). Whether the mechanism of injury results from local cytopathic effects of the virus versus an indirect injury to systemic inflammatory response is not known. While CT findings of pancreatic edema and mild peripancreatic fluid collections in association with COVID-19 appear in case reports (103, 104), reports of pancreatic imaging findings are rare.

Are there any neuroimaging findings in COVID-19 that are concerning and consistent in the literature?

Neurological symptoms in COVID-19 are relatively uncommon, seen in about 5% of patients overall. The most common clinical symptoms include anosmia, headache, confusion, and encephalopathy. Large vessel ischemic stroke as well as Guillain-Barré syndrome are less common clinical presentations that have received substantial interest in the literature. At this time, it is difficult or impossible to determine the exact proportion of patients infected with SARS Co-V-2 that experience each of these specific neurologic symptoms. In the ICU setting, approximately 20% of patients will have some type of neurological impairment (105).

Approximately one half of patients that have undergone neuroimaging in the setting of COVID-19 have abnormal findings (106). The primary patterns of abnormalities include ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, leptomeningeal enhancement, encephalomyelitis, and widespread white matter hyperintensities, which may be associated with multiple microhemorrhages (107-110). Unfortunately, for many or most of these imaging findings, it remains unclear whether they are related to the underlying infection or to the multiple confounding comorbidities, including prolonged hypoxia and deranged coagulation parameters (111). For example, the widespread microhemorrhages are striking but have been previously reported in seriously ill intensive care unit patients without COVID-19 (112). A recent postmortem report noted that hemorrhagic transformation was rare with “pronounced neuroinflammatory changes” representing the dominant pathologic findings (113). Rarity of hemorrhagic findings was also observed in a recent systematic review (114). Large vessel occlusions have been seen in patients with COVID-19, which is unsurprising given the prothrombotic effects of the underlying infection. Anosmia, a common presenting symptom, was shown to be associated with T2 hyperintensity and volume loss in the olfactory bulb on MRI, but it remains unclear whether these imaging findings relate to direct viral involvement or post-inflammatory changes (115, 116). A recent report of olfactory epithelial biopsy highlighted its disruption, suggesting that direct neural invasion was not the primary culprit in anosmia (117).

The virus itself has been isolated from the CSF in very few reports (118), again lending credence to the hypothesis that neuroimaging findings are at least in part related to the associated systemic manifestations of the disease (109). Given the myriad presenting neurological symptoms, the frequency of normal imaging findings in symptomatic patients, the wide range of neuroimaging findings, and the lack of clear evidence of direct CNS involvement with the SARS-CoV-2, it remains difficult or impossible to draw meaningful conclusions about the role of neuroimaging in this pandemic (119).

Remaining Questions

Although our knowledge of COVID-19 and the role imaging plays in diagnosis and management has greatly increased since the infection became a global pandemic, many questions remain unanswered:

● What are the long-term sequelae of COVID-19 in the lungs and cardiovascular system?

● Are there long-term sequelae of COVID-19 outside of the cardiovascular system that have yet to be determined?

● Do classification systems of CT and CXR findings sufficiently predict prognosis and is extent of disease enough?

● Can imaging be used to reduce hospital admissions?

● How will the role of imaging change with the winter season of respiratory illnesses in the Northern Hemisphere?

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors would like thank Adina Haramati, M.D., for contributing to the pulmonary vascular and cardiovascular content.

References

- 1.Kanne JP. Chest CT Findings in 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Infections from Wuhan, China: Key Points for the Radiologist. Radiology. 2020:200241. Epub 2020/02/06. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200241. PubMed PMID: 32017662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanne JP, Little BP, Chung JH, Elicker BM, Ketai LH. Essentials for Radiologists on COVID-19: An Update-. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E113-E4. Epub 2020/02/27. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200527. PubMed PMID: 32105562; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7233379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma A, Eisen JE, Shepard JO, Bernheim A, Little BP. Case 25-2020: A 47-Year-Old Woman with a Lung Mass. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(7):665-74. Epub 2020/07/29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc2004977. PubMed PMID: 32730700; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7449229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Radiology . ACR recommendations for the use of chest radiography and computed tomography (CT) for suspected COVID-19 infection Reston, VA2020. Available from: https://www.acr.org/Advocacy-and-Economics/ACR-Position-Statements/Recommendations-for-Chest-Radiography-and-CT-for-Suspected-COVID19-Infection.

- 5.Society of Thoracic Radiology . STR/ASER COVID-19 position statement. Society of Thoracic Radiology and American Society of Emergency Radiology, March 11, 2020 2020. Available from: https://thoracicrad.org/?page_id=2879. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubin GD, Ryerson CJ, Haramati LB, Sverzellati N, Kanne JP, Raoof S, et al. The Role of Chest Imaging in Patient Management during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multinational Consensus Statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2020;296(1):172-80. Epub 2020/04/07. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201365. PubMed PMID: 32255413; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7233395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goyal N, Chung M, Bernheim A, Keir G, Mei X, Huang M, et al. Computed Tomography Features of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review for Radiologists. J Thorac Imaging. 2020;35(4):211-8. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000527. PubMed PMID: 32427651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong HYF, Lam HYS, Fong AH, Leung ST, Chin TW, Lo CSY, et al. Frequency and Distribution of Chest Radiographic Findings in Patients Positive for COVID-19. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E72-e8. Epub 2020/03/29. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201160. PubMed PMID: 32216717; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7233401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobi A, Chung M, Bernheim A, Eber C. Portable chest X-ray in coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19): A pictorial review. Clin Imaging. 2020;64:35-42. Epub 2020/04/08. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2020.04.001. PubMed PMID: 32302927; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7141645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toussie D, Voutsinas N, Finkelstein M, Cedillo MA, Manna S, Maron SZ, et al. Clinical and Chest Radiography Features Determine Patient Outcomes In Young and Middle Age Adults with COVID-19. Radiology. 2020:201754. Epub 2020/05/14. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201754. PubMed PMID: 32407255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung M, Bernheim A, Mei X, Zhang N, Huang M, Zeng X, et al. CT Imaging Features of 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Radiology. 2020:200230. Epub 2020/02/06. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200230. PubMed PMID: 32017661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simpson S, Kay FU, Abbara S, Bhalla S, Chung JH, Chung M, et al. Radiological Society of North America Expert Consensus Statement on Reporting Chest CT Findings Related to COVID-19. Endorsed by the Society of Thoracic Radiology, the American College of Radiology, and RSNA - Secondary Publication. J Thorac Imaging. 2020;35(4):219-27. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000524. PubMed PMID: 32324653; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7255403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGuinness G, Zhan C, Rosenberg N, Azour L, Wickstrom M, Mason DM, et al. Increased Incidence of Barotrauma in Patients with COVID-19 on Invasive Mechanical Ventilation. Radiology. 2020;297(2):E252-E62. Epub 2020/07/02. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020202352. PubMed PMID: 32614258; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7336751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernheim A, Mei X, Huang M, Yang Y, Fayad ZA, Zhang N, et al. Chest CT Findings in Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19): Relationship to Duration of Infection. Radiology.0(0):200463. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200463. PubMed PMID: 32077789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan F, Ye T, Sun P, Gui S, Liang B, Li L, et al. Time Course of Lung Changes On Chest CT During Recovery From 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pneumonia. Radiology. 2020:200370. Epub 2020/02/13. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200370. PubMed PMID: 32053470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan Y, Guan H, Zhou S, Wang Y, Li Q, Zhu T, et al. Initial CT findings and temporal changes in patients with the novel coronavirus pneumonia (2019-nCoV): a study of 63 patients in Wuhan, China. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(6):3306-9. Epub 2020/02/13. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06731-x. PubMed PMID:32055945; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7087663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li K, Fang Y, Li W, Pan C, Qin P, Zhong Y, et al. CT image visual quantitative evaluation and clinical classification of coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Eur Radiol. 2020;30(8):4407-16. Epub 2020/03/25. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06817-6. PubMed PMID: 32215691; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7095246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruch Y, Kaeuffer C, Ohana M, Labani A, Fabacher T, Bilbault P, et al. CT lung lesions as predictors of early death or ICU admission in COVID-19 patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020. Epub 2020/07/24. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.030. PubMed PMID: 32717417; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7378475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin X, Min X, Nan Y, Feng Z, Li B, Cai W, et al. Assessment of the Severity of Coronavirus Disease: Quantitative Computed Tomography Parameters versus Semiquantitative Visual Score. Korean J Radiol. 2020;21(8):998-1006. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2020.0423. PubMed PMID: 32677384; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7369205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pu J, Leader JK, Bandos A, Ke S, Wang J, Shi J, et al. Automated quantification of COVID-19 severity and progression using chest CT images. Eur Radiol. 2020. Epub 2020/08/13. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07156-2. PubMed PMID: 32789756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang L, Han R, Ai T, Yu P, Kang H, Tao Q, et al. Serial Quantitative Chest CT Assessment of COVID-19: A Deep Learning Approach. Radiology: Cardiothoracic Imaging. 2020;2(2):e200075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leonardi A, Scipione R, Alfieri G, Petrillo R, Dolciami M, Ciccarelli F, et al. Role of computed tomography in predicting critical disease in patients with covid-19 pneumonia: A retrospective study using a semiautomatic quantitative method. Eur J Radiol. 2020;130:109202. Epub 2020/07/29. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.109202. PubMed PMID: 32745895; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7388797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu N, He G, Yang X, Chen J, Wu J, Ma M, et al. Dynamic changes of Chest CT follow-up in Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) pneumonia: relationship to clinical typing. BMC Med Imaging. 2020;20(1):92. Epub 2020/08/05. doi: 10.1186/s12880-020-00491-2. PubMed PMID: 32758155; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7403785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu X, Zhou H, Zhou Y, Wu X, Zhao Y, Lu Y, et al. Temporal radiographic changes in COVID-19 patients: relationship to disease severity and viral clearance. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):10263. Epub 2020/06/24. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66895-w. PubMed PMID: 32581324; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7314788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao W, Zhong Z, Xie X, Yu Q, Liu J. Relation Between Chest CT Findings and Clinical Conditions of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pneumonia: A Multicenter Study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;214(5):1072-7. Epub 2020/03/03. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.22976. PubMed PMID: 32125873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun D, Li X, Guo D, Wu L, Chen T, Fang Z, et al. CT Quantitative Analysis and Its Relationship with Clinical Features for Assessing the Severity of Patients with COVID-19. Korean J Radiol. 2020;21(7):859-68. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2020.0293. PubMed PMID: 32524786; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7289692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen LD, Zhang ZY, Wei XJ, Cai YQ, Yao WZ, Wang MH, et al. Association between cytokine profiles and lung injury in COVID-19 pneumonia. Respir Res. 2020;21(1):201. Epub 2020/07/29. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01465-2. PubMed PMID: 32727465; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7389162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Francone M, Iafrate F, Masci GM, Coco S, Cilia F, Manganaro L, et al. Chest CT score in COVID-19 patients: correlation with disease severity and short-term prognosis. Eur Radiol. 2020. Epub 2020/07/04. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07033-y. PubMed PMID: 32623505; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7334627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J, Meng G, Li W, Shi B, Dong H, Su Z, et al. Relationship of chest CT score with clinical characteristics of 108 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Respir Res. 2020;21(1):180. Epub 2020/07/14. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01440-x. PubMed PMID: 32664991; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7359422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li K, Chen D, Chen S, Feng Y, Chang C, Wang Z, et al. Predictors of fatality including radiographic findings in adults with COVID-19. Respir Res. 2020;21(1):146. Epub 2020/06/13. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01411-2. PubMed PMID: 32527255; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7289230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu PP, Tian RH, Luo S, Zu ZY, Fan B, Wang XM, et al. Risk factors for adverse clinical outcomes with COVID-19 in China: a multicenter, retrospective, observational study. Theranostics. 2020;10(14):6372-83. Epub 2020/05/15. doi: 10.7150/thno.46833. PubMed PMID: 32483458; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7255028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang R, Ouyang H, Fu L, Wang S, Han J, Huang K, et al. CT features of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia according to clinical presentation: a retrospective analysis of 120 consecutive patients from Wuhan city. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(8):4417-26. Epub 2020/04/11. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06854-1. PubMed PMID: 32279115; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7150608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galloway JB, Norton S, Barker RD, Brookes A, Carey I, Clarke BD, et al. A clinical risk score to identify patients with COVID-19 at high risk of critical care admission or death: An observational cohort study. J Infect. 2020;81(2):282-8. Epub 2020/06/02. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.064. PubMed PMID: 32479771; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7258846 interest form and report no conflicts of interest. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schalekamp S, Huisman M, van Dijk RA, Boomsma MF, Freire Jorge PJ, de Boer WS, et al. Model-based Prediction of Critical Illness in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. Radiology. 2020:202723. Epub 2020/08/13. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020202723. PubMed PMID: 32787701; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7427120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hui TCH, Khoo HW, Young BE, Haja Mohideen SM, Lee YS, Lim CJ, et al. Clinical utility of chest radiography for severe COVID-19. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2020;10(7):1540-50. Epub 2020/07/18. doi: 10.21037/qims-20-642. PubMed PMID: 32676371; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7358410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuo BJ, Lai YK, Tan MML, Goh CX. Utility of Screening Chest Radiographs in Patients with Asymptomatic or Minimally Symptomatic COVID-19 in Singapore. Radiology. 2020:203496. Epub 2020/12/08. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020203496. PubMed PMID: 33289614; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7734843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prokop M, van Everdingen W, van Rees Vellinga T, Quarles van Ufford H, Stöger L, Beenen L, et al. CO-RADS: A Categorical CT Assessment Scheme for Patients Suspected of Having COVID-19-Definition and Evaluation. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E97-E104. Epub 2020/04/27. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201473. PubMed PMID: 32339082; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7233402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.BSTI COVID-19 Guidance for the Reporting Radiologist version 2.0 London: BSTI ; 2020 [cited 2020 11/12/2020]. Available from: https://www.bsti.org.uk/standards-clinical-guidelines/clinical-guidelines/bsti-covid-19-guidance-for-the-reporting-radiologist/.

- 39.Salehi S, Abedi A, Balakrishnan S, Gholamrezanezhad A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) imaging reporting and data system (COVID-RADS) and common lexicon: a proposal based on the imaging data of 37 studies. Eur Radiol. 2020. Epub 2020/04/28. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06863-0. PubMed PMID: 32346790; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7186323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gezer NS, Ergan B, Barış MM, Appak Ö, Sayıner AA, Balcı P, et al. COVID-19 S: A new proposal for diagnosis and structured reporting of COVID-19 on computed tomography imaging. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2020;26(4):315-22. doi: 10.5152/dir.2020.20351. PubMed PMID: 32558646; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7360076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Byrne D, O'Neill SB, Müller NL, Silva Müller CI, Walsh JP, Jalal S, et al. RSNA Expert Consensus Statement on Reporting Chest CT Findings Related to COVID-19: Interobserver Agreement Between Chest Radiologists. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2020:846537120938328. Epub 2020/07/02. doi: 10.1177/0846537120938328. PubMed PMID: 32615802; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7335944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bellini D, Panvini N, Rengo M, Vicini S, Lichtner M, Tieghi T, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and interobserver variability of CO-RADS in patients with suspected coronavirus disease-2019: a multireader validation study. Eur Radiol. 2020. Epub 2020/09/23. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07273-y. PubMed PMID: 32968883; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7510765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hare SS, Rodrigues JCL, Nair A, Jacob J, Upile S, Johnstone A, et al. The continuing evolution of COVID-19 imaging pathways in the UK: a British Society of Thoracic Imaging expert reference group update. Clin Radiol. 2020;75(6):399-404. Epub 2020/04/15. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2020.04.002. PubMed PMID: 32321645; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7158776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Litmanovich DE, Chung M, R RK, Kicska G, J PK. Review of Chest Radiograph Findings of COVID-19 Pneumonia and Suggested Reporting Language. J Thorac Imaging. 2020. Epub 2020/06/11. doi: 10.1097/rti.0000000000000541. PubMed PMID: 32520846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hare SS, Tavare AN, Dattani V, Musaddaq B, Beal I, Cleverley J, et al. Validation of the British Society of Thoracic Imaging guidelines for COVID-19 chest radiograph reporting. Clin Radiol. 2020. Epub 2020/07/08. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2020.06.005. PubMed PMID: 32631626; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7298474 Imaging. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lang M, Som A, Mendoza DP, Flores EJ, Li MD, Shepard JO, et al. Detection of Unsuspected Coronavirus Disease 2019 Cases by Computed Tomography and Retrospective Implementation of the Radiological Society of North America/Society of Thoracic Radiology/American College of Radiology Consensus Guidelines. J Thorac Imaging. 2020. Epub 2020/06/17. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000542. PubMed PMID: 32558725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fang Y, Zhang H, Xie J, Lin M, Ying L, Pang P, et al. Sensitivity of Chest CT for COVID-19: Comparison to RT-PCR. Radiology.0(0):200432. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200432. PubMed PMID: 32073353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharfstein JM, Becker SJ, Mello MM. Diagnostic Testing for the Novel Coronavirus. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1437-8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3864. PubMed PMID: 32150622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection based on CT scan vs RT-PCR: reflecting on experience from MERS-CoV. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105(2):154-5. Epub 2020/03/06. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.03.001. PubMed PMID: 32147407; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7124270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen D, Jiang X, Hong Y, Wen Z, Wei S, Peng G, et al. Can Chest CT Features Distinguish Patients With Negative From Those With Positive Initial RT-PCR Results for Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020:1-5. Epub 2020/05/05. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.23012. PubMed PMID: 32368928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, Zhan C, Chen C, Lv W, et al. Correlation of Chest CT and RT-PCR Testing for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: A Report of 1014 Cases. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E32- E40. Epub 2020/02/26. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200642. PubMed PMID: 32101510; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7233399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang W, Yan F. Patients with RT-PCR-confirmed COVID-19 and Normal Chest CT. Radiology. 2020;295(2):E3. Epub 2020/03/06. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200702. PubMed PMID: 32142398; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7233382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Y, Dong C, Hu Y, Li C, Ren Q, Zhang X, et al. Temporal Changes of CT Findings in 90 Patients with COVID-19 Pneumonia: A Longitudinal Study. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E55-E64. Epub 2020/03/19. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200843. PubMed PMID: 32191587; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7233482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Waller JV, Kaur P, Tucker A, Lin KK, Diaz MJ, Henry TS, et al. Diagnostic Tools for Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Comparing CT and RT-PCR Viral Nucleic Acid Testing. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020:1-5. Epub 2020/05/15. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.23418. PubMed PMID: 32412790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eng J, Bluemke DA. Imaging Publications in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Applying New Research Results to Clinical Practice. Radiology. 2020:201724. Epub 2020/04/23. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201724. PubMed PMID: 32324100; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7233392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim H, Hong H, Yoon SH. Diagnostic Performance of CT and Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction for Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Meta-Analysis. Radiology. 2020;296(3):E145-E55. Epub 2020/04/17. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201343. PubMed PMID: 32301646; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7233409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salameh JP, Leeflang MM, Hooft L, Islam N, McGrath TA, van der Pol CB, et al. Thoracic imaging tests for the diagnosis of COVID-19. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;9:CD013639. Epub 2020/09/30. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013639.pub2. PubMed PMID: 32997361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li L, Qin L, Xu Z, Yin Y, Wang X, Kong B, et al. Using Artificial Intelligence to Detect COVID-19 and Community-acquired Pneumonia Based on Pulmonary CT: Evaluation of the Diagnostic Accuracy. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E65-E71. Epub 2020/03/19. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200905. PubMed PMID: 32191588; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7233473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bai HX, Wang R, Xiong Z, Hsieh B, Chang K, Halsey K, et al. Artificial Intelligence Augmentation of Radiologist Performance in Distinguishing COVID-19 from Pneumonia of Other Origin at Chest CT. Radiology. 2020;296(3):E156-E65. Epub 2020/04/27. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201491. PubMed PMID: 32339081; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7233483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mei X, Lee HC, Diao K, Huang M, Lin B, Liu C, et al. Artificial intelligence-enabled rapid diagnosis of COVID-19 patients. medRxiv. 2020. Epub 2020/04/17. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.12.20062661. PubMed PMID: 32511559; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7274240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang K, Liu X, Shen J, Li Z, Sang Y, Wu X, et al. Clinically Applicable AI System for Accurate Diagnosis, Quantitative Measurements, and Prognosis of COVID-19 Pneumonia Using Computed Tomography. Cell. 2020;181(6):1423-33.e11. Epub 2020/05/04. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.045. PubMed PMID: 32416069; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7196900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murphy K, Smits H, Knoops AJG, Korst MBJM, Samson T, Scholten ET, et al. COVID-19 on Chest Radiographs: A Multireader Evaluation of an Artificial Intelligence System. Radiology. 2020;296(3):E166-E72. Epub 2020/05/08. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201874. PubMed PMID: 32384019; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7437494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li MD, Arun NT, Gidwani M, Chang K, Deng F, Little BP, et al. Automated assessment of COVID-19 pulmonary disease severity on chest radiographs using convolutional Siamese neural networks. medRxiv. 2020. Epub 2020/05/26. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.20.20108159. PubMed PMID: 32511570; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7274251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tsai EB, Simpson S, Lungren M, Hershman M, Roshkovan L, Colak E, et al. The RSNA International COVID-19 Open Annotated Radiology Database (RICORD). Radiology. 2021:203957. Epub 2021/01/05. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203957. PubMed PMID: 33399506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lim W, Le Gal G, Bates SM, Righini M, Haramati LB, Lang E, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3226-56. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024828. PubMed PMID: 30482764; PubMed Cent ral PMCID: PMCPMC6258916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith MJ, Hayward SA, Innes SM, Miller ASC. Point-of-care lung ultrasound in patients with COVID-19 - a narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(8):1096-104. Epub 2020/04/28. doi: 10.1111/anae.15082. PubMed PMID: 32275766; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCP MC7262296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zuckier LS, Moadel RM, Haramati LB, Freeman LM. Diagnostic Evaluation of Pulmonary Embolism During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Nucl Med. 2020;61(5):630-1. Epub 2020/04/01. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.120.245571. PubMe d PMID: 32238427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Helms J, Tacquard C, Severac F, Leonard-Lorant I, Ohana M, Delabranche X, et al. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1089-98. Epub 2020/05/04. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x. PubMed PMID: 32367170; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7197634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kaminetzky M, Moore W, Fansiwala K, Babb JS, Kaminetzky D, Horwitz LI, et al. Pulmonary Embolism on CTPA in COVID-19 Patients. Radiology Cardiothoracic Imaging. 2020;2(4):e200308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bilaloglu S, Aphinyanaphongs Y, Jones S, Iturrate E, Hochman J, Berger JS. Thrombosis in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 in a New York City Health System. JAMA. 2020;324(8):799-801. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.13372. PubMed PMID: 32702090; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7372509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mestre-Gómez B, Lorente-Ramos RM, Rogado J, Franco-Moreno A, Obispo B, Salazar-Chiriboga D, et al. Incidence of pulmonary embolism in non-critically ill COVID-19 patients. Predicting factors for a challenging diagnosis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020. Epub 2020/06/29. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02190-9. PubMed PMID: 32613385; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7327193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gervaise A, Bouzad C, Peroux E, Helissey C. Acute pulmonary embolism in non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients referred to CTPA by emergency department. Eur Radiol. 2020. Epub 2020/06/09. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06977-5. PubMed PMID: 32518989; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7280685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grillet F, Behr J, Calame P, Aubry S, Delabrousse E. Acute Pulmonary Embolism Associated with COVID-19 Pneumonia Detected with Pulmonary CT Angiography. Radiology. 2020;296(3):E186-E8. Epub 2020/04/23. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201544. PubMed PMID: 32324103; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7233384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Léonard-Lorant I, Delabranche X, Séverac F, Helms J, Pauzet C, Collange O, et al. Acute Pulmonary Embolism in Patients with COVID-19 at CT Angiography and Relationship to d-Dimer Levels. Radiology. 2020;296(3):E189-E91. Epub 2020/04/23. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201561. PubMed PMID: 32324102; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7233397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Saba L, Sverzellati N. Is COVID Evolution Due to Occurrence of Pulmonary Vascular Thrombosis? J Thorac Imaging. 2020. Epub 2020/04/28. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000530. PubMed PMID: 32349055; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7253049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Raptis CA, Hammer MM, Henry TS, Hope MD, Schiebler ML, van Beek EJR. What Do We Really Know About Pulmonary Thrombosis in COVID-19 Infection? J Thorac Imaging. 2020. Epub 2020/06/29. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000545. PubMed PMID: 32618808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.van Dam LF, Kroft LJM, van der Wal LI, Cannegieter SC, Eikenboom J, de Jonge E, et al. Clinical and computed tomography characteristics of COVID-19 associated acute pulmonary embolism: A different phenotype of thrombotic disease? Thromb Res. 2020;193:86-9. Epub 2020/06/06. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.06.010. PubMed PMID: 32531548; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7274953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cavagna E, Muratore F, Ferrari F. Pulmonary Thromboembolism in COVID-19: Venous Thromboembolism or Arterial Thrombosis? Radiology: Cardiothoracic Imaging. 2020;2(4):e200289. doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lax SF, Skok K, Zechner P, Kessler HH, Kaufmann N, Koelblinger C, et al. Pulmonary Arterial Thrombosis in COVID-19 With Fatal Outcome: Results From a Prospective, Single-Center, Clinicopathologic Case Series. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(5):350-61. Epub 2020/05/14. doi: 10.7326/M20-2566. PubMed PMID: 32422076; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7249507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fox SE, Akmatbekov A, Harbert JL, Li G, Quincy Brown J, Vander Heide RS. Pulmonary and cardiac pathology in African American patients with COVID-19: an autopsy series from New Orleans. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(7):681-6. Epub 2020/05/27. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30243-5. PubMed PMID: 32473124; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7255143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, Haverich A, Welte T, Laenger F, et al. Pulmonary Vascular Endothelialitis, Thrombosis, and Angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(2):120-8. Epub 2020/05/21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. PubMed PMID: 32437596; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7412750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.D'Amico G, Muñoz-Félix JM, Pedrosa AR, Hodivala-Dilke KM. "Splitting the matrix": intussusceptive angiogenesis meets MT1-MMP. EMBO Mol Med. 2020;12(2):e11663. Epub 2019/12/20. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201911663. PubMed PMID: 31858727; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7005529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lang M, Som A, Mendoza DP, Flores EJ, Reid N, Carey D, et al. Hypoxaemia related to COVID-19: vascular and perfusion abnormalities on dual-energy CT. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020. Epub 2020/04/30. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30367-4. PubMed PMID: 32359410; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7252023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Oudkerk M, Büller HR, Kuijpers D, van Es N, Oudkerk SF, McLoud TC, et al. Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment of Thromboembolic Complications in COVID-19: Report of the National Institute for Public Health of the Netherlands. Radiology. 2020:201629. Epub 2020/04/23. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201629. PubMed PMID: 32324101; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7233406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]