Abstract

Background and purpose:

The optimization of an effective non-viral gene delivery method for genetic manipulation of primary human T cells has been a major challenge in immunotherapy researches. Due to the poor transfection efficiency of conventional methods in T cells, there has been an effort to increase the transfection rate in these cells. Protamine is an FDA-approved compound with a documented safety profile that enhances DNA condensation for gene delivery.

Experimental approach:

In this study, the effect of protamine sulfate on the transfection efficiency of standard transfection reagents, was evaluated to transfect primary human T cells. In this regard, pre-condensation of DNA was applied using protamine, and the value of the zeta potential of DNA/protamine/cargo complexes was determined. T cells were transfected with DNA/protamine/cargo complexes. The transfection efficiency rate was evaluated by flow cytometry. Also, the green fluorescent protein expression level and cytotoxicity of each complex were identified using real-time polymerase chain reaction and MTT assay, respectively.

Findings/Results:

Our results demonstrated that protamine efficiently increases the positive charge of DNA/cargo complex without any cytotoxic effect on the primary human T cells. We observed that the transfection efficiency in DNA/protamine/ Lipofectamine® 2000 and DNA/protamine/TurboFect™ was 87.2% and 78.9%, respectively, while transfection of T cells by Lipofectamine® 2000 and TurboFect™ would not result in sufficient transfection.

Conclusion and implications:

Protamine sulfate enhanced the transfection rate of T cells; and could be a promising non-viral gene delivery method to achieve a safe, rapid, cost-effective, and efficient system which will be further applied in gene therapy and T cells manipulation methods.

Keywords: Gene transfer techniques, Protamine sulfate, T-Lymphocytes, Transfection

INTRODUCTION

The vast clinical success of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells immunotherapy in targeting various blood malignancies and solid tumors and the applicability of other T cells subsets in the treatment of autoimmune diseases have created an inevitable need for a cost- effective, rapid, and efficient method for ex vivo gene delivery to primary human T cells (1). Recently, most clinical trials have applied gamma-retroviral and lentiviral methods for genetic manipulation of T cells, which has led to a permanent CAR expression (2,3,4,5). Although highly efficient-viral vectors are costly to produce at the good manufacturing practices scale and have significant limitations, such as cytotoxicity, immunogenicity, and insertional mutagenesis for clinical applications (6).

Moreover, non-viral methods, including electroporation and chemical transfection reagents have been suggested as alternative strategies for gene delivery to mammalian cells. However, several studies evaluated the challenging nature of primary T lymphocytes manipulation using non-viral gene delivery systems have presented their low transfection efficiency rate and the transient expression of introduced gene, as the most important limitations (7,8).

Since T lymphocytes are considered as hard to transfect primary cells, electroporation is becoming the most commonly used non-viral method for gene delivery to T lymphocytes. Electroporation is an efficient physical method for introducing a gene into the cells; however, electroporation conditions need to be optimized because of low transfection efficiency and poor cellular viability, particularly in primary human lymphocytes (9,10). On the other hand, T cells are resistant to common chemical transfection reagents, such as Lipofectamine® 2000, PolyFect™, and TurboFect™, which have a safety profile for many mammalian cells. These reagents are less popular in the case of T cells transfection due to their low transfection efficiency (11). Therefore, improvement of non-viral gene delivery methods seems to be necessary for an effective gene transfer into T cells, as well as a reduction of the carrier’s cell toxicity. However, there are numerous obstacles to develop a promising non-viral gene delivery method including DNA/carrier complex formation, cell entrance mechanism, endosomal escape, dissociation of DNA from the cargo, and nuclear translocation (7,8).

To promote the transfection process, it might be desirable to facilitate the electrostatic interaction of the transfection reagent with the negative charge of the DNA backbone and the cell membrane (12). Also, previous data have shown that pre condensation of DNA by an additional cationic charge improves its protection against degradation (13).

Protamines are small peptides (MW 4-10 kDa), FDA-approved cationic nuclear protein enriched in arginine. Due to their membrane- translocating activity and the ability to improve DNA packaging, they have been widely studied in the area of gene delivery. Protamines are isolated from the sperm of mature fish (14). During the fertilization procedure, protamines bind to and condense genomic DNA, and then deliver DNA to the nucleus due to containing four nuclear localization sequences in their structures (12,15,16). This unique role of protamine which directly transfers the DNA complex to the nucleus is beneficial for overcoming some major hurdles in gene delivery.

In the current study, the effect of protamine on transfection efficiency of standard transfection reagents, including TurboFect™ and Lipofectamine® 2000, was evaluated to transfect primary human T cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of PBMC and T-cell culture

Informed consent was obtained from a healthy donor before blood collection. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from heparinized blood using the Ficoll-hypaque density gradient. The isolated cells were incubated for 24 h in complete RPMI-1640 (Bioidea, Iran) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Bioidea, Iran) at 37 °C in a humidified incubator supplied with 5% CO2 to isolate monocytes in a 75-T cell culture flask. Lymphocytes were collected at 500 g for 5 min and suspended in complete RPMI-1640 medium containing 1 μg/mL phytohemagglutinin (Sigma, USA), and then cells were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. T cells were expanded using 3.3 μg/mL anti cluster of differentiation 3 (CD3) monoclonal antibody (Biolegend, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Cell lines

The Jurkat cells (human leukemia T cells) and human embryonic kidney 293 cells (HEK- 293) were purchased from Pasteur Institute of Iran (Tehran, Iran) and maintained in complete RPMI-1640 medium and cultured at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator.

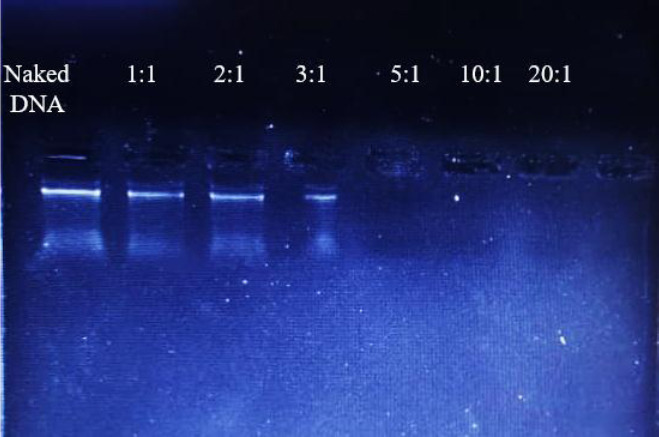

Preparation of plasmid/protamine complexes and detection of electrostatic binding of protamine to DNA

The plasmid DNA, pCDH513-B, encoding the green fluorescent protein (GFP) was extracted from Escherichia coli TOP10F’ and purified using a plasmid extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Genetbio, Korea). The purity of the extracted plasmid was checked by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel and the concentration of DNA was estimated by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm. One mg of purified plasmid was mixed with different amounts of protamine sulfate (Sigma, USA) to achieve the following N/P ratios: 20:1, 10:1, 5:1, 3:1, 2:1, and 1:1 in 150 mM NaCl. The mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 15 min. After incubation, the binding of protamine to DNA in each mixture was evaluated using a dye displacement assay and the electrophoretic mobility (15 min at 120 V) of the mixture was visualized on 1% (w/v) agarose gel stained with EcoDye (BIOFACT, Korea) to detect the optimal DNA/protamine ratio.

The zeta potential of DNA/protamine/cargo complexes:

To detect the surface charge of different DNA/cargo complexes, which was prepared by adding different transfection reagents to optimal DNA/protamine ratio, the value of the zeta potential was determined using Laser Zeta meter (HORBIO Scientific, Japan) in water solution (pH 7.4).

T cells transfection

Primary T cells and Jurkat cells, as well as HEK-293 as the control, were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 approximately 24 h before the transfection procedure which was performed in triplicate. Then 2.5 μL of transfection reagents, TurboFect™ and Lipofectamine® 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), was added to the optimal DNA/protamine complex, prepared as described earlier, and incubated for an additional 15 min at room temperature. The mixtures were subsequently added to the cells and the transfection procedure carried out according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The cells which were transfected using transfection reagents alone served as controls.

Transfection efficiency measurement

Cells were then harvested 24 h after transfection to evaluate the transfection efficiency in each group using fluorescent microscopy and flow cytometry analysis in parallel. Cells were centrifuged at 500 g for 5 min and then washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS; Bioidea, Iran). The GFP expression was evaluated with a BD flow cytometer (BD Bioscience, USA) by accumulating up to 100,000 cells per tube and the obtained data were analyzed by FlowJo™ 7.6.5 software (TreeStar, USA).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA of about 2 × 105 transfected T cells was extracted using the RNX kit (Cinagen, Iran) and treated with DNase I enzyme (Thermo Scientific, USA). The quality and quantity of the extracted RNA were assessed spectrophotometrically and by electrophoresis and the A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios indicate that the RNA was high purified. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using 2 μg of the total RNA according to first-strand cDNA synthesis kit instruction (Thermo Scientific, USA). Primer efficiency was assessed before undertaking the sample analysis using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assays of cDNA dilution series and relative quantification was performed using the following specific primers: GFP forward, 5’-AAGCTGACCCTGAAGTT- CATCTGC-3’, and GFP reverse, 5’-CTT- GTAGTTGCCGTCGTCCTTGAA-3’, beta- actin forward, 5’-ATGTGTGACGAAGAA- GCAT-CAGCC-3’, and beta actin reverse, 5’- TCATCCCAGTTGGTGATAATGCCG -3’.

All qRT-PCR reactions were prepared in triplicate by mixing 10 μL of SYBR green master mix (Ampliqon kit, Denmark), 0.5 μL of each primer (10 μM), 2 pL of synthesized cDNA, and 7 μL RNase free water. ABI Applied Biosystems™ Thermal cycler (Thermo Scientific, USA) was used with the cycling conditions comprised an initial 10 min incubation at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. Relative expression was determined using the 2-ΔΔCT method.

Cytotoxicity assay

MTT assay was performed to determine the cell toxicity of different DNA/protamine/cargo complexes in each group compared to untreated cells, as the negative control. About 2 × 105 primary isolated T cells, Jurkat cells, and HEK293 cells were seeded in 24-well plates (1 mL/well) and incubated for 24 h, before the experiment. Cells were incubated with protamine, TurboFect™, Lipofectamine®, DNA /protamine/TurboFect™, and DNA/protamine/Lipofectamine® complexes using the concentration mentioned in the transfection procedure for 24 h, respectively. Hygromycin B (Sigma, USA) at 900 μg/mL, as a positive control, was used to completely lyse the cells. Then the medium was removed and replaced with 50 μL (4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2- yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) tetrazolium (MTT; Sigma, USA) diluted in RPMI 1640 (final concentration 0.5 mg/mL). After 4 h incubation, formazan crystals were solubilized with 500 μL of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm in a Microplate Reader (Eppendorf, Germany). The cell viability (%) was calculated using the following equation:

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as mean ± SD and analyzed by SPSS software version 22. The statistical significance was determined using the one-way ANOVA and student t-test and the P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Effect of protamine on complex surface charge

After incubation, a fixed quantity of DNA with increasing amounts of protamine, the complete retardation of supercoiled and relaxed forms of DNA was found at and above N/P ratios 5:1 (Fig. 1). This result showed the complete masking of DNA at this optimal N/P ratio. On the other hand, the surface charge of different complexes was measured and the zeta potential of DNA/TurboFect™, DNA/Lipofectamine® 2000, DNA/protamine/ TurboFe™ and DNA/protamine/ Lipofectamine® 2000 was 1.2, 10.9, 22.2, and 25.3 mV, respectively. Data showed that protamine significantly enhances DNA/cargo complex surface positive charge.

Fig. 1.

Gel retardation assay of protamine/DNA complexes at various N/P ratios showed the complete retardation of DNA at and above N/P ratios 5:1. The values mentioned corresponding with the N/P ratios of protamine/DNA in a 20 μL reaction.

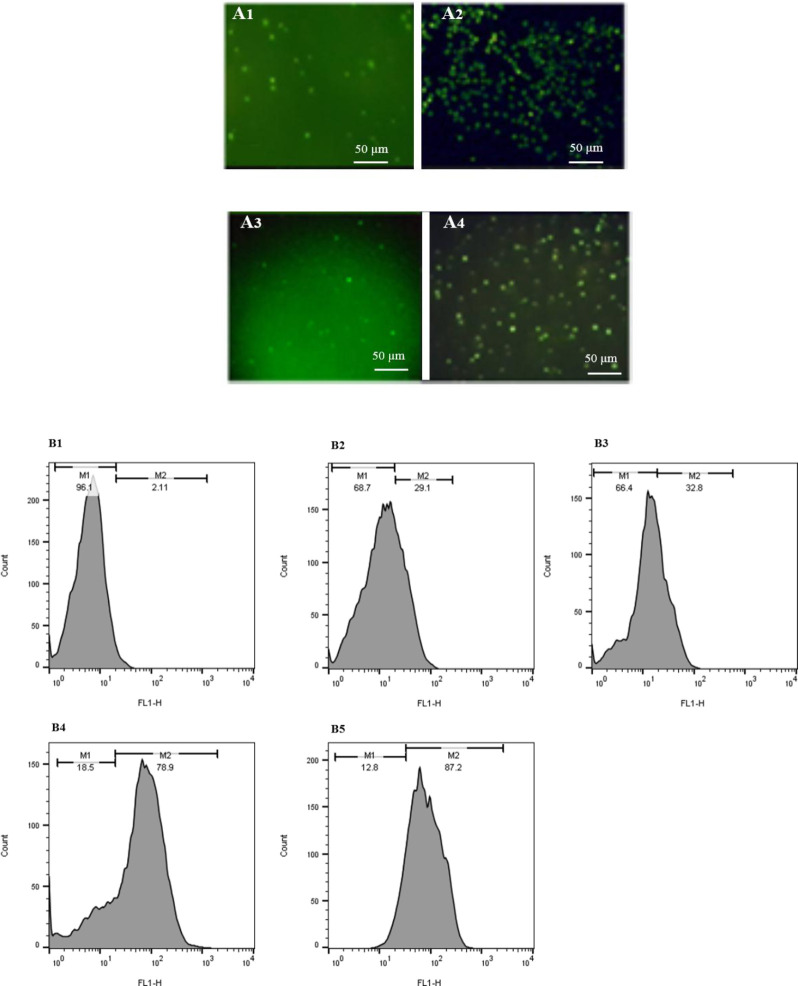

Primary T cells were transfected effectively by DNA/protamine/cargo complexes

At 24 h post-transfection, the transfection efficiency was determined via flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy in different cells. The number of cells expressing GFP markedly increased when protamine was applied in DNA/cargo complex formation (Figs. 2, 3). As flow cytometry histograms are shown in Fig. 2B, an improvement in transfection efficiency was observed when the DNA/cargo complex was applied in the transfection procedure. Accordingly, GFP expression was 87.2% and 78.9% in T cells which transfected via DNA/protamine/Lipofectamine® 2000 and DNA/protamine/ TurboFect™, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Protamine enhanced in vitro transfection efficiency of TurboFect™ and Lipofectamine® 2000. (A1-A4) The fluorescent microscopy images of human primary T cells transfected by Lipofectamine® 2000, DNA/protamine/Lipofectamine® 2000, TurboFect™, and DNA/protamine/TurboFect™ complex, respectively. (B1-B5) Flow cytometry results of human primary T cells, untransfected, transfected by TurboFect™, transfected by Lipofectamine® 2000, transfected by DNA/protamine/TurboFect™ complex, and transfected by DNA/protamine/Lipofectamine® 2000.

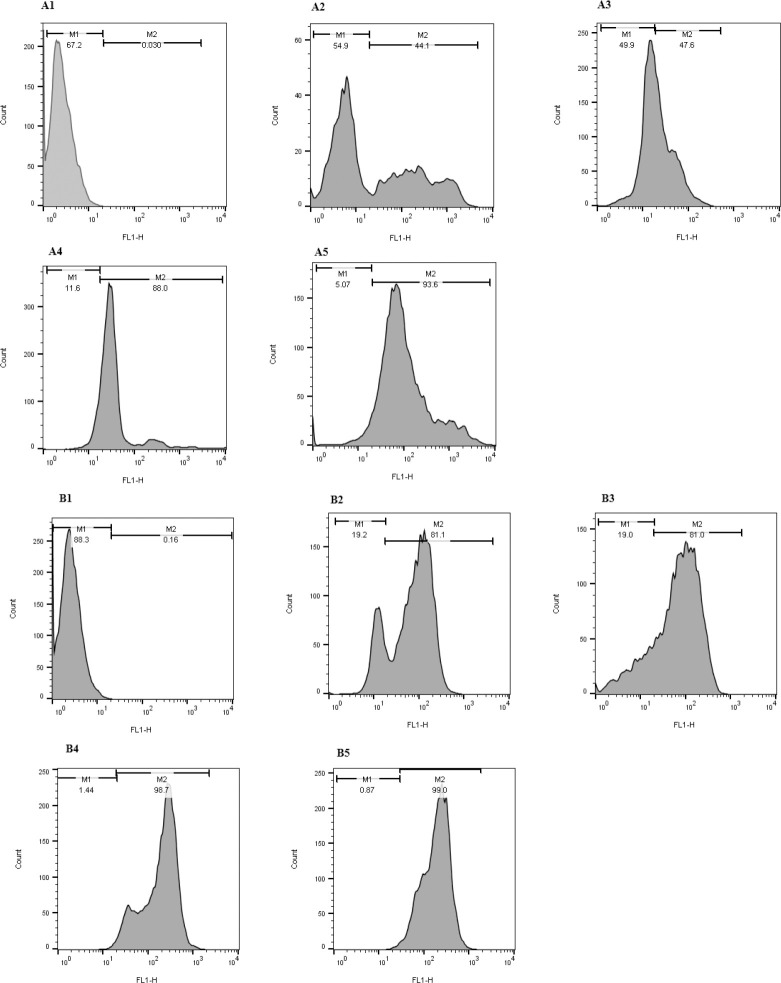

Fig. 3.

Flow cytometry analysis of GFP expression. Histograms showing the numbers of cells and the fluorescence intensity in transfected and untransfected cells. As flow cytometry results show, GFP expression increased in the case of DNA/protamine/cargo transfection. (A1-A5) GFP expression results in the Jurkat cell line including untransfected, transfected by TurboFect™, transfected by Lipofectamine® 2000, transfected by DNA/protamine/TurboFect™ complex, and transfected by DNA/protamine/Lipofectamine® 2000. (B1-B5) GFP expression results in HEK 293 cell line including untransfected, transfected by TurboFect™, transfected by Lipofectamine® 2000, transfected by DNA/protamine/TurboFect™ complex, and transfected by DNA/protamine/Lipofectamine® 2000, respectively. GFP, green fluorescent protein.

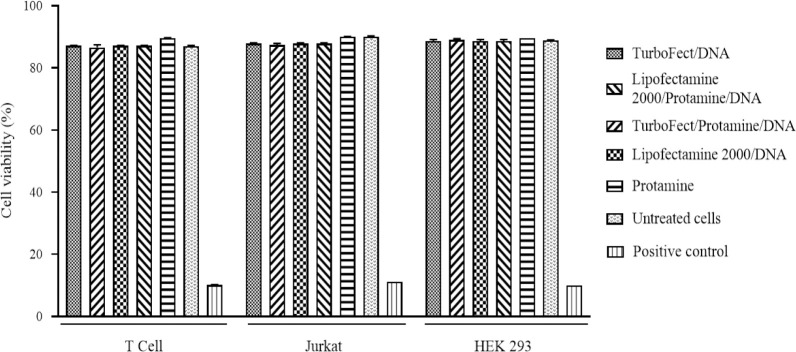

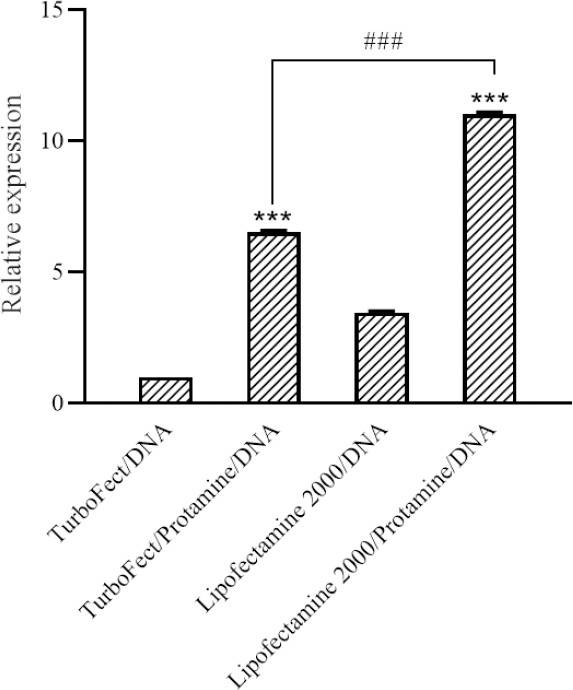

Relative quantitation of GFP expression

The GFP expression was measured by qRT- PCR and the mean value of GFP relative quantitation illustrated in Fig. 4. Our data showed that the transfection using DNA/protamine/cargo complexes results in a higher expression of the GFP marker. Remarkably, the level of GFP mRNA expression was elevated to 11.03 and 6.53 fold in the cells transfected with DNA/protamine/Lipofectamine® 2000 and DNA/protamine/TurboFect™, respectively, compared to the TurboFect™ transfected cells (P < 0.001).

Fig. 4.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction results. The green fluorescent protein expression level was significantly increased in transfected cells with DNA/protamine/cargo as illustrated in the graph. The results are presented as the means ± SD, n = 3. ***P < 0.001 indicates significant differences compared to the TurboFect/DNA group.

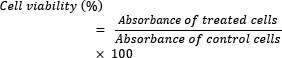

Cytotoxicity assay

To investigate the cytotoxicity of different complexes, the MTT assay was carried out. No significant cytotoxic effects were observed in the cells following incubation with different complexes in comparison with the negative control (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

MTT assay results show no significant difference in cell viability between different groups concerning the untreated cells (negative control; P > 0.05). The mean values of the cell viability of two independent experiments are plotted with mean ± SD. Hygromycin B at 900 μg/mL was used as a positive control.

DISCUSSION

Optimization of gene-delivery methods for effective genetic manipulation in primary human T cells is a major challenge in fundamental T cell studies and clinical immunotherapy researches (17). Viral-vectors are the most commonly used transfection methods in clinical trials and can achieve higher transduction efficiency. However, they may display high immunogenicity which causes a problem in clinical studies (18,19).

Data extracted from prior studies have provided noticeable evidence to overcome the current barriers that lead to the low efficiency of gene transfer into primary human T cells (11,20). Furthermore, the development of an effective non-viral gene delivery method for clinical applications depends on the ability of genes to escape from lysosomal degradation and poor nuclear translocation, which limits foreign DNA expression in the transfected cells (4,21). It is also well-documented that lysosomal degradation can be avoided by employing various approaches such as the proton sponge effect, that has been observed in some cationic polymers, including polyethyleneimine (PEI), polyamidoamine (PAMAM), and pH-sensitive membrane lytic peptides . However, the efficient nucleus targeting remains a barrier in transfection procedure (22,23). Additionally, DNA condensation with a cationic nuclear targeting signal peptide, such as TAT oligomer and a tetramer of the SV40 T-antigen-derived nuclear localization signal (NLSSV40) led to an increase in the nuclear membrane translocation (24,25).

As a cationic peptide that has been approved by the FDA, protamine has been widely used in DNA condensing, nuclear targeting, and the transgene expression enhancement (26). Further, the low transfection efficiency of the protamine/DNA complex was interestingly documented in the previous studies due to the strong hydrophilicity of protamine, which limits the complex to cross the cellular membrane (27). Therefore, it is essential to facilitate the electrostatic interaction between protamine and the negative charge on the cell membrane.

A standard commercial transfection reagent, such as TurboFect™ or Lipofectamine® 2000 with a safe usage profile is an alternative for current transfection methods, which primarily rely on physical methods and viral vector-based gene transfer systems. Because of the low transfection efficiency of conventional methods in human primary T cells, recent studies have focused on increasing the level of transfection rate in these cells (28).

In the present study, a combination of protamine and the aforementioned transfection reagents was used to form a stable and positively charged cargo for DNA delivery into the human primary T cells. The result from this study showed that the zeta potential of DNA/TurboFect™, DNA/Lipofectamine® 2000, DNA/protamine/ TurboFect™, and DNA/protamine/Lipofectamine® 2000 was 1.2, 10.9, 22.2, and 25.3 mV, respectively, and demonstrated that protamine increases the surface charge of different complexes. Our results also demonstrated that protamine at optimal N/P ratio can enhance DNA delivery rate and DNA/protamine/cargo complexes can effectively transfect human primary T cells as well as Jurkat and HEK293 cell lines and the highest expression efficiency was obtained using DNA/protamine/Lipofectamine®. The cytotoxicity of the different complex was estimated by MTT assay and data showed the average cell viability was over 87%. Furthermore, results of the present study suggest that pre condensation of DNA enhances the transfection rate of human primary T cells using TurboFect™ and Lipofectamine® 2000; thus, it could be a promising non-viral gene delivery method to achieve a safe, rapid, cost- effective, and efficient system to be further applied in gene therapy and T cells manipulation methods such as CAR T cell therapy.

CONCLUSION

Our results indicated that protamine sulfate increases the amount of DNA/cargo positive charge and improves the transfection efficiency of primary human T cells without any cytotoxic effect. Also, the in vitro transfection studies demonstrated that higher levels of gene expression can be achieved when protamine was applied in DNA/cargo complex formation. This optimized method could be a promising non-viral gene delivery strategy to achieve a safe, rapid, cost-effective, and efficient gene transfection method to be further applied in gene therapy and T cells fundamental studies.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that no conflict of interest in this study.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

H. Khanahmad and I. Rahimmanesh conceived of the presented idea. I. Rahimmanesh developed the theoretical framework, carryed out the experimental methods, analysed the data, and wrote the article. H. Khanahmad and M. Totonchi revised the final version of the article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was financially supported under Grant No. 970703 by the Biotechnology Development Council of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jin C, Fotaki G, Ramachandran M, Nilsson B, Essand M, Yu D. Safe engineering of CAR T cells for adoptive cell therapy of cancer using long-term episomal gene transfer. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8(7):702–711. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201505869. DOI: 10.15252/emmm.201505869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu WS, Pathak VK. Design of retroviral vectors and helper cells for gene therapy. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52(4):493–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang GP, Garrigue A, Ciuffi A, Ronen K, Leipzig J, Berry C, et al. DNA bar coding and pyrosequencing to analyze adverse events in therapeutic gene transfer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(9):e49,1–12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn125. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkn125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Aneed A. An overview of current delivery systems in cancer gene therapy. J Control Release. 2004;94(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2003.09.013. DOI: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darzi L, Boshtam M, Shariati L, Kouhpayeh S, Gheibi A, Mirian M, et al. The silencing effect of miR-30a on ITGA4 gene expression in vitro: an approach for gene therapy. Res Pharm Sci. 2017;12(6):456–464. doi: 10.4103/1735-5362.217426. DOI: 10.4103/1735-5362.217426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schambach A, Baum C. Clinical application of lentiviral vectors-concepts and practice. Curr Gene Ther. 2008;8(6):474–482. doi: 10.2174/156652308786848049. DOI: 10.2174/156652308786848049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gresch O, Engel FB, Nesic D, Tran TT, England HM, Hickman ES, et al. New non-viral method for gene transfer into primary cells. Methods. 2004;33(2):151–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2003.11.009. DOI: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yin H, Kanasty RL, Eltoukhy AA, Vegas AJ, Dorkin JR, Anderson DG. Non-viral vectors for gene-based therapy. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15(8):541–55. doi: 10.1038/nrg3763. DOI: 101038/nrg3763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stroh T, Erben U, Kühl AA, Zeitz M, Siegmund B. Combined pulse electroporation-a novel strategy for highly efficient transfection of human and mouse cells. PloS One. 2010;5(3):e9488,1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009488. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Z, Qiu S, Zhang X, Chen W. Optimized DNA electroporation for primary human T cell engineering. BMC Biotechnol. 2018;18(1):4–12. doi: 10.1186/s12896-018-0419-0. DOI: 10.1186/s12896-018-0419-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao N, Qi J, Zeng Z, Parekh P, Chang CC, Tung CH, et al. Transfecting the hard-to-transfect lymphoma/leukemia cells using a simple cationic polymer nanocomplex. J Control Release. 2012;159(1):104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.01.007. DOI: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motta S, Brocca P, Del Favero E, Rondelli V, Cantù L, Amici A, et al. Nanoscale structure of protamine/DNA complexes for gene delivery. Appl Phys Lett. 2013;102(5):053703,1–4. DOI: 10.1063/1.4790588. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen J, Yu Z, Chen H, Gao J, Liang W. Transfection efficiency and intracellular fate of polycation liposomes combined with protamine. Biomaterials. 2011;32(5):1412–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.074. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuchiya Y, Ishii T, Okahata Y, Sato T. Characterization of protamine as a transfection accelerator for gene delivery. J Bioact Compat Polym. 2006;21(6):519–537. DOI: 10.1177/0883911506070816. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vighi E, Montanari M, Ruozi B, Iannuccelli V, Leo E. The role of protamine amount in the transfection performance of cationic SLN designed as a gene nanocarrier. Drug Deliv. 2012;19(1):1–10. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2011.621989. DOI: 10.3109/10717544.2011.621989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta S, Tiwari N, Munde M. A Comprehensive biophysical analysis of the effect of DNA binding drugs on protamine-induced DNA condensation. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):5891–5901. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41975-8. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-019-41975-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu L, Johnson C, Fujimura S, Teque F, Levy JA. Transfection optimization for primary human CD8+ cells. J Immunol Methods. 2011;372(1-2):22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2011.06.026. DOI: 10.1016/j.jim.2011.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang W, Li W, Ma N, Steinhoff G. Non-viral gene delivery methods. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2013;14(1):46–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohammadi Z, Shariati L, Khanahmad H, Kolahdouz M, Kianpoor F, Ghanbari JA, et al. A lentiviral vector expressing desired gene only in transduced cells: an approach for suicide gene therapy. Mol Biotechnol. 2015;57(9):793–800. doi: 10.1007/s12033-015-9872-3. DOI: 10.1007/s12033-015-9872-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Y, Zheng Z, Cohen CJ, Gattinoni L, Palmer DC, Restifo NP, et al. High-efficiency transfection of primary human and mouse T lymphocytes using RNA electroporation. Mol Ther. 2006;13(1):151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.07.688. DOI: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.07.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Ilarduya CT, Arangoa M, Moreno-Aliaga M, Duzgune§ N. Enhanced gene delivery in vitro and in vivo by improved transferrin-lipoplexes. BBA Bioenergetics. 2002;1561(2):209–221. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00348-6. DOI: 10.1016/S0005-2736(02)00348-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pishavar E, Oroojalian F, Ramezani M, Hashemi M. Cholesterol-conjugated PEGylated PAMAM as an efficient nanocarrier for plasmid encoding interleukin-12 immunogene delivery toward colon cancer cells. Biotechnol Prog. 2020;36(3):e2952, 1–8. doi: 10.1002/btpr.2952. DOI: 10.1002/btpr.2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cervia LD, Chang CC, Wang L, Yuan F. Distinct effects of endosomal escape and inhibition of endosomal trafficking on gene delivery via electrotransfection. PloS One. 2017;12(2):e0171699, 1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171699. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hébert E. Improvement of exogenous DNA nuclear importation by nuclear localization signal-bearing vectors: a promising way for non-viral gene therapy. Biol Cell. 2003;95(2):59–68. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(03)00007-8. DOI: 10.1016/s0248-4900(03)00007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akita H, Kurihara D, Schmeer M, Schleef M, Harashima H. Effect of the compaction and the size of DNA on the nuclear transfer efficiency after microinjection in synchronized cells. Pharmaceutics. 2015;7(2):64–73. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics7020064. DOI: 10.3390/pharmaceutics7020064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masuda T, Akita H, Harashima H. Evaluation of nuclear transfer and transcription of plasmid DNA condensed with protamine by microinjection: the use of a nuclear transfer score. FEBS Lett. 2005;579(10):2143–2148. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.02.071. DOI: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu X, Li L, Li X, Tao D, Zhang P, Gong J. Aptamer- protamine-siRNA nanoparticles in targeted therapy of ErbB3 positive breast cancer cells. Research Square. 2020:1–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119963. DOI: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-42522/v1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basiouni S, Fuhrmann H, Schumann J. High- efficiency transfection of suspension cell lines. Biotechniques. 2012;53(2):1–4. doi: 10.2144/000113914. DOI: 10.2144/000113914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]