Abstract

Background:

The pandemic of COVID-19 has affected many countries and medical services including assisted reproductive treatment (ART) have been hampered.

Aim:

The study was conducted to assess the preparedness of ART clinics and staff to resume services; patients' reasons to initiate treatment; and key performance indicators (KPIs) of ART laboratories during the pandemic.

Setting and Design:

This was a semidescriptive, prospective study in two private in vitro fertilization (IVF) clinics in Maharashtra, India, when COVID-19 testing for asymptomatic people was unavailable.

Materials and Methods:

Time required for replenishing consumables and clinic preparedness to function under “new norms” of pandemic was documented. Infection mitigation measures and triaging strategy were evaluated. KPIs following resumption were analyzed. The Student's t-test was performed for comparing parameters.

Results:

Thirty percent of the patients consulted through telemedicine accepted or were eligible to initiate treatment on clinic resumption. Lack of safe transport and financial constraints prevented majority from undergoing IVF, and 9% delayed treatment due to fear of pandemic. With adequate training, staff compliance to meet new demands was achieved within a week, but procuring consumables and injections was time-consuming. Fifty-two cycles of IVF were performed including fresh and frozen embryo transfers with satisfactory KPIs even during pandemic. Conscious sedation and analgesia during oocyte retrieval were associated with reduced procedure time and no intervention for airway maintenance compared to general anesthesia. Self-reported pain scores by patients ranged from nil to mild on a graphic rating scale.

Conclusions:

This study provides practical insight for the resumption of IVF services during the COVID-19 pandemic.

KEYWORDS: Assisted reproduction, coronaviruses, COVID-19 pandemic, key performance indicators, resumption of in vitro fertilization, SARS

INTRODUCTION

COVID-19 pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus has strained and challenged the health-care systems of all the affected countries in an unprecedented manner.[1,2,3,4] As a mitigation strategy, many countries were/are under lockdown to minimize human-to-human transmission, and prioritize services of health-care professionals and medical equipment to the care of seriously sick people.[4] Nonessential medical services were put on hold leading to the suspension of medically assisted reproduction/assisted reproductive treatments (ART) in majority of the clinics across the globe. The scientific bodies in assisted reproduction advised against initiation of new treatment cycles including ovulation induction, intrauterine insemination, in vitro fertilization (IVF), intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), embryo transfers, and nonurgent gamete cryopreservation in March 2020, except for ongoing cycles or fertility preservation before gonadotoxic therapy.[2,3,5,6] They recommended preferential utilization of telemedicine over “in-person” interactions and suspension of nonurgent diagnostic and elective surgeries.[2,3,5,6]

Subsequently, the reproductive medicine societies advocated gradual and judicious resumption of reproductive care services, as we understood the population dynamics of the spread of the virus and successful mitigation strategies.[7,8,9,10,11,12] A general framework for restarting ART activities was released based on the principle that clinic staff and couple undergoing treatment are triage-negative.[7,8,9,10,11,12] For the triage positive patients, further decisions are based on the results of testing for SARS-CoV-2.[9,12] Many clinics across the globe adopted this framework and resumed ART services. Limited knowledge of the pregnancy outcomes in COVID-19 affected women remains an important concern with resumption of ART services during the pandemic.[13,14,15,16,17] While the ART pregnancies are not absolutely protected from SARS-CoV-2, the possibility of vertical transmission from an IVF clinic may be negligible.[18,19,20,21] Presence of SARS-CoV-2 receptors in both female and male genital tract and gametes, and permissibility of trophectoderm and early placenta to the virus are of concern for ART fraternity.[22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30] The available evidence should be a part of pretreatment communication with couples planning ART.

India went into national lockdown from 25th March 2020 to 31st May 2020. Movement of people and all forms of transport including goods across states were completely prohibited during the initial weeks. While essential medical services were operational, nonessential services were halted. Most IVF clinics spontaneously stopped services at least in the first 6 weeks. As time-dependent relaxations happened based on the scenario across individual states or territories, resumption of fertility services became a necessity, infertility being a time-sensitive disease.[12,31] As per the national guidelines at the time, the SARS-CoV-2 testing by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction was to be offered to symptomatic patients and those requiring emergency medical services.[12,32,33] The testing facilities were overburdened and not easily available in all parts of the country. This raised the need for a clinic centric protocol to reinitiate treatment, taking cognizance of local scenario and regular internal auditing, in addition to observing international recommendations.[34,35]

Herein, we describe our experience of resuming IVF services during the initial months of the pandemic in a hot spot zone of India. We aim to address three important primary outcome measures (1) preparedness of clinics to resume functionality, (2) characteristics of patients making an informed decision to initiate treatment, and (3) key performance indicators (KPIs) of laboratories following the resumption of IVF work. Secondary outcome measures were the efficacy and acceptance of conscious sedation and analgesia (CSA) for oocyte pick up (OPU) in comparison to general anesthesia (GA).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

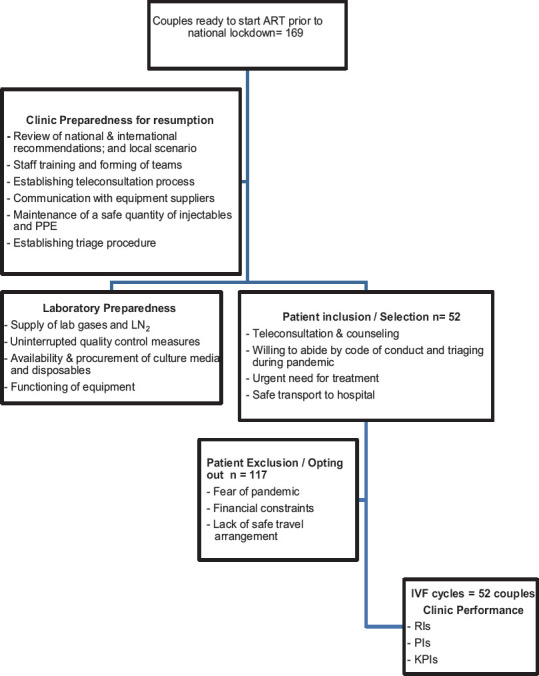

The data are from two private tertiary fertility clinics – Sushrut Assisted Conception Clinic and Shreyas Hospital, Kolhapur (Clinic 1) and Nagpur Test Tube Baby Centre, Nagpur (Clinic 2), located 900 km apart, in the state of Maharashtra, India. This prospective, observational, semidescriptive study was conducted between April 14, 2020 and July 22, 2020. It was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional review boards of the hospitals granted approval both for resuming IVF work and for the study. Informed written consent was obtained from couples for planned treatment and for IVF during the COVID-19 pandemic. Consent to follow the prescribed code of conduct was obtained from all the team members and patients [Supplementary Data]. The methodology of the study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study design. ART=Assisted reproduction treatments, PPE=Personal protective equipment, LN2=Liquid nitrogen, IVF=In vitro fertilization, RIs=Reference indices, PIs=Performance indices, KPIs=Key performance indices

Functional preparedness of the clinics

Both clinics maintained the basic functionality of IVF laboratories during the national lockdown. An uninterrupted supply of laboratory gases, liquid nitrogen (LN2), daily logging of quality control measures, and maintaining the stock of all consumables above predefined clinic-specific minimum quantity were ensured. While suppliers prioritized the provision of LN2 to IVF clinics during the lockdown period, a special permission from local authorities was needed for transport, facilitated by the directives of the national body of IVF specialists (Indian Society for Assisted Reproduction). Distributors of laboratory, operating theater, and ultrasound equipment were contacted and any specific advice for the protection of the equipment was implemented. The time taken to achieve each of these goals was documented. Telephonic contact with all patients in different stages of preparation for an ART cycle was established, at the beginning of the lockdown. They were counseled about compliance with lockdown rules and importance of “new norms” (social distancing, wearing face masks in public places, and hand sanitization). Further, they were encouraged to follow healthy lifestyle with a combination of exercise and diet and refrain from visiting hospital without prior arrangement.

Simultaneously, steps were initiated toward COVID-19 specific functioning of the clinic personnel during the pandemic, and regular “mock-drills” were commenced. These involved adherence to “new norms,” undergoing daily triaging, working in teams, disinfection routine, and adherence to a clinic-specific code of conduct [Supplementary Data] which later incorporated the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) and Indian advisory.[9,12] Triage questionnaire went through periodic review and changes to meet the demands of the evolving pandemic [Supplementary Data].[9,35,36] Two teams, each consisting of at least one clinician, one IVF nurse, an anesthetist, and two embryologists skilled in performing ICSI, vitrification, and warming were created with due consideration for short and long leave of absence. Both teams resided in different geographic areas to minimize the chance of members from the two teams being in the same containment zone and getting quarantined simultaneously.[37] The time required to comply with all the steps and for procurement of appropriate standard personal protective equipment (PPE) was tracked on a daily basis.

Patient recruitment

Once the clinic preparedness was ensured, couples wishing to commence their treatment were contacted. Treatment plan, code of conduct, available data on pregnancy outcomes in COVID-19 affected women, and need for the couple to self-isolate from 2 weeks before initiation of ovarian stimulation through the duration of treatment were discussed through teleconsultation. The reasons for consenting or not for IVF were recorded. Consent forms were sent electronically to the couples and a follow-up teleconsultation was done to clarify any concerns. This was followed by an “in-person” consultation to reinforce the above information, to ensure couple's understanding of the code of conduct, possibility of cancellation if the pandemic worsened locally, or if either or both patients contracted or suspected of having COVID-19. Information of financial implications and alternative arrangements if any personnel from the clinics got infected, was also provided. All couples were encouraged to procure COVID-specific insurance cover for any hospitalization due to COVID-19 before initiating the cycles. The couples were counseled regarding the current lack of accessibility to COVID testing for asymptomatic people in the local area. Semen cryopreservation if not previously done, was performed during their visit to the hospital and postwash samples were stored in a dedicated cryocan.

Among those who wished to start IVF, priority was given to couples with wife's age >35 years, proven or expected poor ovarian reserve (anti-Mullerian hormone <1.2 ng/mL and antral follicle count <8), and for fertility preservation in malignant and benign conditions.

Those with apprehension about treatment during pandemic, financial concerns, or without safe transport were advised to defer treatment. Some were referred to nearby clinics to avoid undue delay due to travel restrictions.

COVID-19-specific patient preparedness

Specific plans were made to address the situation of a patient undergoing ovarian stimulation or a staff testing positive for COVID-19. While a patient testing positive meant cancelation of the ongoing cycle, a staff testing positive would demand temporary closure of the clinic for contact tracing, testing, and sanitization. An alternative arrangement whereby patients could continue their treatment in another clinic was set in place. In an exceptional scenario of high risk of ovarian hyperstimulation (OHSS) and the woman testing positive for COVID, if cancelation was not an option for medical or personal reasons, a GnRH analog trigger and oocyte retrieval in a designated COVID hospital with appropriate infection control measures and oocyte vitrification was planned [Supplementary Data]. The cost of injections used before any cancellation was to be borne by the couple while the clinic may not charge for ultrasound and endocrine monitoring and any professional fee in the event of cancellation.

Treatment

Clinic 1 utilized both agonist and antagonist protocols, IVF or ICSI, based on ovarian reserve markers and semen parameters, respectively, and selective embryo freezing. Clinic 2 utilized antagonist protocol, ICSI, and elective “freeze all” policy in fresh cycles. The starting dose of gonadotropin depended on the ovarian reserve markers in both clinics. All women received human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) as trigger. Frozen embryo transfer was performed in hormone replacement therapy cycles following mid-luteal pituitary downregulation in both clinics. Anesthesia for OPU depended on the routine practice in each clinic. Women in Clinic 1 were counseled and offered CSA with intravenous (IV) midazolam and fentanyl. Propofol was available for use if pain control was not satisfactory. Pain score was documented on a graphic rating scale (GRS) of 10 cm length extending from no pain through mild, moderate to severe pain.[38] In Clinic 2, GA with IV propofol and fentanyl along with an intubation box were used during OPU. The duration of OPU was documented. Sequential embryo assessment was performed in Clinic 1, whereas uninterrupted single-step culture was utilized in Clinic 2. Those undergoing embryo transfer received standard luteal support with vaginal progesterone.

Key performance indicators

Reference indicators (RIs), performance indicators (PIs), and KPIs to assess the teams' performance during the pandemic were assessed according to ESHRE Vienna consensus criteria.[39] 18 of the total 19 recommended parameters relevant to both the clinics involving ovarian stimulation, fertilization and post-fertilization laboratory parameters were documented.

Statistical analysis

As this study reports initial experience after resuming IVF work during the COVID-19 pandemic, a sample size calculation was not performed. Data for both the clinics are pooled and represented. The data were prospectively maintained in Microsoft excel. Parameters related to different types of anesthesia for OPU were compared using Student's t-test and the results expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The rest of the data are expressed as actual numbers, percentages, or descriptive.

RESULTS

Time taken for preparing the clinics and staff to the new norms

Time taken to achieve safe functional preparedness is shown in Table 1. Among the laboratory requirements, availability of fresh stock of media and consumables took the longest, followed by fresh stock of gonadotropin injections. The operation theater preparedness was uninterrupted. Most of the COVID-19-specific requirements were achieved within a week's time, but achieving appropriate social distancing measures took more than 2 weeks. One nursing staff declined working for the fear of COVID-19 while the majority was willing to work and resumed duties on the availability of safe transport organized by the clinics. The timeline for preparedness was similar in both clinics. In absence of SARS-CoV-2 testing services for asymptomatic individuals, the triage questionnaire played an important role and needed regular modification due to evolving situation. Triage questionnaire and procedure were implemented within 48 h.

Table 1.

Time taken for resumption of services in the in vitro fertilization clinics postlockdown imposed due to COVID-19 pandemic

| Services | Time taken for re-initiation since lockdown |

|---|---|

| Laboratory preparedness | |

| LN2 supply | Uninterrupted |

| Calibrated CO2 cylinders | Already available |

| Daily logs | Uninterrupted |

| Availability of fresh culture media | 45 days |

| Availability of IVF laboratory consumables | 45 days |

| Availability of andrology laboratory consumables | 2 days |

| Establishing contact with equipment suppliers | 8 days |

| Availability of laboratory disinfectant | Continuous |

| Operation theater preparedness | |

| Availability of fresh stock of anesthetic medications | Uninterrupted |

| Availability of anesthetic gases | Uninterrupted |

| Consumables for routine procedures | Uninterrupted |

| Preparedness for superovulation | |

| Gonadotropins, agonists, and antagonists for superovulation | 30 days |

| Oral/transdermal estrogens; progesterone preparations | 7 days |

| COVID-19-specific preparedness | |

| Procuring N95 masks and other PPE | 7 days |

| Organizing the clinics for triage, isolation area, and patient movement | 2 days |

| Developing teleconsultation questionnaire | 1 day |

| Establishing teleconsultation system | 5 days |

| Sanitization of hospital every 4 h | Immediate |

| Staff preparation for COVID-19-specific requirements | |

| Number of staff willing to work | 31/32 (92.3%) |

| Number of staff eligible to work after completing triaging | 31 |

| Number of staff compliance with daily triage (since March 25, 2020) | 100% |

| Safe transport services for staff | 2 days |

| Staff compliance for wearing mask | Immediate |

| Compliance with hand sanitization | 2 days |

| Compliance with appropriate PPE | 7 days |

| Training for social distancing practices | 17 days |

| Training for obtaining patient consent for teleconsultation | 2 days |

CO2=Carbon dioxide, LN2=Liquid nitrogen, PPE=Personal protective equipment, IVF=In vitro fertilization

Operationalization and outcomes of telemedicine services

Telemedicine questionnaire was prepared within a week and the teleconsultation services could be initiated immediately in both the clinics [Table 1 and Supplementary Data]. About 169 couples were consulted by telemedicine based on the prelockdown appointment logs [Table 2]. Only 30% of them wished to undergo IVF postresumption of services. Lack of easy access to clinics was the most prominent reason to delay treatment, followed by financial constraints [Table 2].

Table 2.

Outcomes of teleconsultation by the in vitro fertilization clinics after resumption of services postlockdown imposed due to COVID-19 pandemic

| Patient details | Number of couples, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Total number of couples administered with teleconsultation questionnaire | 169 |

| Number of couples agreeing to/eligible for treatment at teleconsultation | 52 (30.8) |

| Number of patients declining/advised against treatment at teleconsultation | 117 (69.2) |

| Reasons for declining | |

| Fear of pandemic | 11 (9.4) |

| Financial reasons | 24 (20.5) |

| Lack of access to clinic | 72 (61.5) |

| Presence of comorbidities | 9 (7.6) |

| Number of patients transferred to other clinics for accessibility | 1 (0.85) |

Characteristics of couples who underwent assisted reproductive treatment

Fifty-two couples underwent treatment on resumption of ART services. All couples complied with new norms, triage during every visit, underwent self-reported isolation for 2 weeks before and during treatment, and agreed to freeze all embryos (and cancel embryo transfer) if advised due to any change in pandemic scenario. Table 3 shows that majority of the couples initiated treatment in view of medical urgency: fertility preservation, expected or proven poor ovarian response (POR). However, a proportion of infertile couples chose to go through treatment without delay due to self-perceived urgency or preparedness.

Table 3.

Indications for assisted reproduction in infertile couples who underwent treatment after resumption of services postlockdown imposed due to COVID-19 pandemic

| Indication for IVF | Number of couples (n=52), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Fresh IVF cycles | 28 |

| Frozen embryo transfer cycles | 24 |

| Fertility preservation | 2 (3.8) |

| Age>35 years | 15 (28.8) |

| Poor ovarian reserve | 12 (23.1) |

| Severe male factor | 15 (28.8) |

| PCOS achieving desired weight reduction | 1 (1.9) |

| Couples’ choice (due to career) | 7 (13.5) |

PCOS=Polycystic ovarian syndrome, IVF=In vitro fertilization

In vitro fertilization treatment details

The mean age of women undergoing ART was 32.3 ± 3.5 years. There was no incidence of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) or COVID-19 and one cycle was canceled due to no response. Different anesthesia techniques used for OPU show a significantly less time for OPU with CSA compared to GA for retrieval of similar number of oocytes [Table 4]. Further, mapping of pain score on a GRS revealed high acceptance rate of CSA [Table 4]. The overall clinical pregnancy rate per cycle was 41.7% in fresh cycles and 48.1% in frozen cycles.

Table 4.

Anesthesia and oocyte pick up details from both clinics after resumption of services postlockdown imposed due to COVID-19 pandemic

| Parameter | Protocol 1 | Protocol 2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anesthesia used for OPU | CSA | GA | |

| Number of patients | 14 | 13 | |

| Duration of OPU (min) | 17.0±3.1 | 23.7±10.9 | 0.03* |

| Pain score during OPU as documented on a GRS | None: 1Mild: 12Moderate: 1 | - | - |

| Number of oocytes (mean±SD) | 12.6±7.4 | 14.5±7.5 | 0.5 |

*P=Significant; value is by Student’s t-test. CSA=Conscious sedation and analgesia, GA=General anesthesia, GRS=Graphic rating scale, OPU=Oocyte pick up, SD=Standard deviation

None of the patients undergoing treatment or the clinic staff were affected by COVID-19 during the study period.

Key performance indicators after resumption of services

Table 5 shows RIs, PIs, and KPIs of the clinics during the pandemic, in comparison to historic data of 3 months during their full functionality (October 2019 to December 2019). As evident, these indicators of clinics' performance matched the historic data and were above the competency value or approached benchmark values as per ESHRE Vienna Consensus.

Table 5.

Reference/performance/key performance indicators in in vitro fertilization clinics after resumption of services postlockdown imposed due to COVID-19 pandemic

| Reference/performance/key performance indicators | Values during study period (%) | Historic data (%) | Competency value (Vienna consensus) | Benchmark value (Vienna consensus) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time period | April 2020 - July 2020 | October 2019 - December 2019 | ||

| Number of patients | 52 | 117 | ||

| Reference indicators | - | |||

| Proportion of oocytes recovered | 366/389 (94.1) | 822/875 (93.9) | - | 80%-95% of follicles |

| Proportion of MII oocytes | 265/350 (75.7) | 503/670 (75.1) | - | 75%-90% |

| Performance indicators | ||||

| Postpreparation sperm motility | 90 | 90 | 90% | ≥95% |

| Polyspermy in IVF | 0/15 (0) | 5/152 (3.3) | - | <6% |

| 1 PN in IVF | 0/15 (0) | 6/152 (3.9) | - | <5% |

| 1 PN in ICSI | 3/265 (1.1) | 10/503 (1.9) | - | <3% |

| Good blastocysts | 40/82 (48.8) | 48/107 (44.8) | - | ≥40% |

| Key performance indicators | ||||

| ICSI damage rate | 25/285 (8.8) | 59/503 (11.7) | </=10 | </=5 |

| ICSI - normal fertilization | 187/285 (65.6) | 310/503 (61.6) | ≥65 | ≥80 |

| IVF - normal fertilization | 10/15 (66.7) | 98/152 (64.5) | ≥60 | ≥75 |

| Failed fertilization in IVF | 0 | 0 | <5 | |

| Cleavage rate | 87/93 (93.5) | 328/408 (80.3) | >/=95 | >/=99 |

| Day 2 embryo development rate | 63/93 (67.7) | 228/408 (55.3) | >/=50 | >/=80 |

| Day 3 embryo development rate | 134/197 (68) | 168/408 (41.1) | >/=40 | >/=60 |

| Blastocyst development rate | 73/156 (46.7) | 52/107 (48.5) | >/=40 | >/=60 |

| Implantation rate (day 3) | 2/6 (33.3)* | 18/70 (25.7) | >/=25 | >/=35 |

| Implantation rate (day 5) | 4/6 (66.6)* | 12/25 (48) | >/-35 | >/=60 |

| Blastocyst cryosurvival rate | 25/26 (96.2) | 50/52 (96.1) | >/=90 | /=99 |

| Implantation rate of vitrified and warmed embryos (day 5) | 12/25 (48) | 26/50 (52) | - | - |

*Data are from embryo transfer in fresh IVF/ICSI cycles. Values are expressed as numbers (%). ICSI=Intracytoplasmic sperm injection, IVF=In vitro fertilization, MII=Meiosis II, PN=Pronucleus

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the three important factors that influence successful resumption of IVF during the COVID-19 pandemic – clinic preparedness, informed decision of patients to go through treatment, and KPIs of the clinics. The study highlights the need for a multipronged approach cognizant of local, national, and international scenario for successful resumption of ART services under the newly defined norms and code of conduct to mitigate the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a hotspot region of India.

Resumption of ART services during pandemic is both a clinical and social dilemma.[3,31] Infertility continues to be the top stressor even in the midst of the pandemic and delaying treatment may add further stress to such couples.[40] Whether psychological stress affects IVF outcome remains a controversial issue.[41,42] However, as the pandemic continues to disrupt routine life, it may become important for those who have not been able to access fertility services.[31,43] While the short-term delay may have no negative impact on IVF outcomes, this has to be balanced against the impact of prolonged delays on population dynamics and age-related decline in live births.[44,45,46]

Timely knowledge sharing and recommendations from national and international scientific societies played a crucial role in planning resumption of ART in our clinics.[7,8,9,10,11,12] One of the first key challenges we faced was the interrupted supply of perishables such as IVF culture media and injections for ovarian stimulation. While other supplies and functionalities were uninterrupted, procurement of perishables took the longest. This was understandably the consequence of restricted import and regional transport services due to lockdown. Our results indicate the need for an anticipatory planning, close monitoring of the ordering and purchase routines, and co-ordination not only at the clinic level but with distributors, and manufacturers as well, both for completion of on-going cycles and for smooth restarting.[47] Another major requirement for service resumption in an IVF clinic is the staff adapting to the new norms.[47] A high asymptomatic infection state, high human-to-human transmission rate, and survival of the virus on surfaces for unusually long periods are important aspects of this pandemic.[48] Clinicians and laboratory and paramedical staff must be acutely aware of this and act appropriately. Most laboratory, paramedical, and support staff were willing to undergo specific training and resume work even in the midst of the pandemic. This is heartening for both clinicians and patients. Once safe transport was organized, they promptly concentrated on training and telecommunication with patients. Adaptation to new practices was achieved within a week with the exception of social distancing measures. Maintaining at least 2 m distance from each other and minimizing “in-person” interactions were hard to achieve and took more than 2 weeks to ensure compliance.

The use of telemedicine has been widely advised to minimize “in-person” visits to the clinic while continuing appropriate clinical services.[2,3,5,6,47] We devised a telequestionnaire that spanned questions not only about the medical problems but also provided information on clinic preparedness and obtained an understanding telephonically if the couples would qualify triaging. Of those who deferred treatment, nearly 62% did so due to lack of appropriate transport to access the clinic. While 20% declined stating financial reasons, only 9% of couples deferred due to fear of pandemic. The findings highlight the possibility of financial crises the society is facing affecting IVF services eventually.[49] In addition to medically urgent IVF, the informed decision by patients to initiate treatment also amounts to a valid indication. Interestingly, approximately 42% underwent treatment because they identified lockdown as an opportunity to improve their lifestyle, which was otherwise a challenge for them due to heavy work schedule. It will be important for reproductive medicine specialists to recognize this demand, which by no stretch of imagination is a medical emergency but a socially justified emergency.[31,49,50,51,52]

Triaging of couples and team members and adherence to the code of conduct as an integral strategy does instill a level of discipline at the clinics.[9,12,34,35] This served as a crucial step toward judicious utilization of resources while striving to provide optimal services. Scientific societies differ in their recommendations of relative roles of triaging and testing for SARS-COV-2.[35,53] Further, as India had closed its international borders since March 2020, the question pertaining to international travel became irrelevant in due course. Our experience highlights that triaging is an evolving concept to ensure patient and staff safety. Even though we could successfully resume IVF, an upward trajectory of COVID-19 demands continued vigilance. While the testing services are still largely prioritized to symptomatic patients and those with high-risk exposures, availability and accessibility for testing are increasing in India.[54] Understanding of utility, constraints, and limitations of different tests for SARS-CoV-2 is increasing as the time span of pandemic is increasing.[55,56] Failure to appreciate the lacunae of various tests and undue reliance on them may prove to be detrimental for the ART program.[53,55]

OPU is the only step in IVF during which considerable time is spent in close proximity to patients. Many different types of anesthesia or analgesia are equally effective in achieving patient comfort during OPU.[57,58,59] The findings of this study show that the procedure time is significantly less with CSA compared to GA for retrieval of similar number of oocytes. Reduced procedural time and no intervention for airway maintenance have important implications in this pandemic with a respiratory virus. Considering that the pain score was low and patient satisfaction was high, this is a useful strategy to mitigate the infection risk to health-care professionals, in addition to the use of appropriate PPE.

Clinical and laboratory PIs provide an objective understanding of the clinic's performance. Additional challenges for ART during this pandemic are the anxieties, added responsibilities, and concerns faced by the IVF team adversely affecting the KPIs.[39,47] We evaluated these less often reported parameters and found that the stimulation and laboratory parameters were consistently above the competency level or approaching benchmark level despite new and diverse responsibilities. In addition, the KPIs were comparable to the prepandemic values and provide an objective evidence of clinical and laboratory performance during the pandemic. This is reassuring and will encourage other clinics to resume services for the benefit of the patients.

The emergence of new evidence and its understanding will continue to influence the safe provision of ART services during this pandemic.[60] Active communication with infertile couples while formulating relevant clinic policies may play an important role for uninterrupted ART services. This study shows the need for simultaneous attention to diverse issues including but not limited to the safety of clinic personnel, safe environment in the clinic for patients, ensuring the availability of the necessary consumables, communication with various agencies, continued communication and counseling of patients, and ongoing learning from the international, national, and local scenario for an effective and safe provision of ART services. The challenges faced by us and our initial experience will be applicable to most clinics in low- to middle-income countries experiencing a first wave of COVID-19 pandemic where testing may not be available freely. In addition, it offers an objective initial evidence for better preparedness of clinics in geographic areas with restricted access to testing in asymptomatic individuals.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, this is the first study with objective documentation of the experience following reopening IVF services during this pandemic. It shows the diverse areas to be addressed while achieving functionality of the clinics. We show that (1) the preparedness of laboratory and hospital setup may not be time-consuming but the supplies need to be ensured, (2) there will be a need for an individualized approach for selecting couples to undergo IVF, and (3) the performance of clinicians and embryologists in the face of uncertainties and anxieties due to the pandemic may not be compromised if adequate measures are taken and training provided. The role of SARS-COV-2 testing in asymptomatic individuals undergoing IVF remains unclear and when access to testing is restricted, it is important to develop clinic-specific triaging norms to resume services. It is possible to provide safe ART services even during the pandemic upon their diligent implementation.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance provided by Miss Rushita Vaghasia and Miss Pranita Bawaskar, Nagpur Test Tube Baby Centre, Nagpur, for data compilation.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Name of the Clinic……………………………

CONSENT for in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection during COVID-19 Pandemic*

Patient's Name……………… Hospital Number (ID)………….

Husband's name …………………

I/we confirm that I/we have been provided with information leaflet on in vitro fertilization (IVF) during the pandemic.

I/we understand the importance of triage and code of conduct and consent to abide by the same to mitigate the risk of acquiring infection.

I/we agree to maintain social distancing and wear face mask at all times while in the clinic and to maintain hand hygiene.

I/we understand that currently, SARS-CoV-2 reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction test is available only for people with specific indications. We may not be able to undergo the test routinely and hence abiding by the above is obligatory.

I/we understand that if triaging results lead to suspicion of COVID-19, I/we will be referred for testing.

If the test is positive, the treatment will be canceled irrespective of the stage of treatment.

I/we understand that there are cost implications for testing (if advised) and cancellation of treatment (if tested positive). If tested positive, HCG will not be administered and treatment will be canceled. The cost of injections received thus far will be borne by me/us while the clinic will forgo any fee incurred for sonography, blood tests, and professional fee. If the source of my/our infection is a clinic personnel, then the clinic will not charge for any of the injections or treatment received during the concerned cycle.

I/we understand that if I become COVID-19 positive during treatment and oocyte retrieval needs be done to reduce the risk of severe OHSS, it would be performed in a hospital designated for COVID treatment and the oocytes will be transported in a transport incubator to the IVF clinic and vitrified for possible future use. They will be cryopreserved in a cryocan designated for COVID patients until further use or evidence.

I/we understand that the national/regional advisory for testing may change in time and agree to follow any changed advisory.

I/we understand that the current understanding of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 through gametes and consequently transmission to embryo is very limited. Similarly, I/we understand the limitations in the understanding of COVID-19 on pregnancy.

I/we understand that if the clinic is sealed due to team members getting infected with COVID-19 during the course of our treatment, our treatment may have to be transferred to another IVF clinic as advised by the clinic (name of the backup clinic…………) and we are willing for the same.

All the above has been explained to us by Dr………………………….

Patient's name:…………….………… Husband's name:…………………………………

Signature:……………………………… Signature:……………………….

Date:………………….…… Date:………………….……

Dr. Name:………………………………. Witness name:……………………………………

Signature:……………………………… Signature:……………………………

Date:…………………….… Date:…………………………….

Teleconsultation Questionnaire

Part 1 (information given to couples)

Compliance with “lockdown” rules

Importance of COVID-19 period norms: social distancing, frequent handwashing, and face mask when in public spaces

Code of conduct leading up to and during treatment

Available evidence on impact of COVID-19 on pregnancy

Clinician's concern, if any, for commencing treatment (any medical conditions).

Part 2 (questionnaire)

Does the couple has any concern about initiating IVF treatment?

Do they have access to clinic/permission to travel (interdistrict or interstate)

Do they have safe mode/s of transport?

How many people live in their household?

Any other concerns?

Anyone affected with COVID-19 in their vicinity/home?

Their reasoning for going ahead with treatment apart from the medical indication.

Triage questionnaire for all those attending the clinic

History of travel in the past 2 weeks (regional, national, or international)

Anyone visiting them in the past 2 weeks

-

Any symptoms:

- Cough, runny nose, sore throat, fever

- Diarrhea/loss of taste/loss of smell.

Contact with anyone diagnosed/suspected of COVID-19?

Number of adults in the household working out of home daily

Certificate of cure, if one has already had COVID-19.

Footnotes

The consent forms are available in English, Marathi, Kannada, and Hindi languages.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO: WHO Virtual Press Conference on COVID-19. 2020. Mar 11, [Last accessed on 2020 Jul 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/transcripts/who-audio-emergencies-coronavirus-press-conference-full-and-final-11mar2020.pdf?sfvrsn=cb432bb3_2 .

- 2.ASRM. American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) Patient Management and Clinical Recommendations during the Coronavirus (Covid-19) Pandemic. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Jul 25]. Available from: https://www.asrm.org/news-andpublications/covid-19/statements/patient-management-and-clinicalrecommendations-during-the-coronavirus-covid-19-pandemic/

- 3.Vaiarelli A, Bulletti C, Cimadomo D, Borini A, Alviggi C, Ajossa S, et al. COVID-19 and ART: The view of the Italian Society of Fertility and Sterility and Reproductive Medicine. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;40:755–9. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedford J, Enria D, Giesecke J, Heymann DL, Ihekweazu C, Kobinger G, et al. WHO Strategic and Technical Advisory Group for Infectious Hazards. COVID-19: Towards controlling of a pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:1015–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30673-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.FOGSI Short Term Advisory on COVID-19 Pandemic. [Last acessed on 2020 Aug 19]. Available from: https://www.fogsi.org/category/whats-new/page/3/

- 6.ESHRE. Coronavirus Covid-19: ESHRE Statement on Pregnancy and Conception. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 19]. Available from: http://www.fertilityeurope.eu/coronavirus-covid-19-eshre-statement-on-pregnancy-and-conception/

- 7.ASRM. Patient Management and Clinical Recommendations during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic. 2020. [Last accessed on 19 Aug 2020]. Available from: https://www.asrm.org/globalassets/asrm/asrm-content/news-and-publications/covid-19/covidtaskforceupdate4.pdf .

- 8.BFS & ARCS. U.K. Best Practice Guidelines for Reintroduction of Routine Fertility Treatments during the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020. [Last [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 19]. Available from: https://www.britishfertilitysociety.org.uk/2020/05/06/arcs-and-bfs-u-k-best-practice-guidelines-forreintroduction-of-routine-fertility-treatments-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

- 9.ESHRE. ESHRE Guidance on Recommencing ART Treatments. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 18]. Available from: http://www.eshre.eu>sitecore-files>Guidelines>COVID19 .

- 10.CFAS. Fertility Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Guiding Principles to Assist Canadian ART Clinics to Resume Services and Care. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 19]. Available from: https://cfas.ca/Fertility_Care_during_COVID-19.html .

- 11.La Marca A, Niederberger C, Pellicer A, Nelson SM. COVID-19: Lessons from the Italian reproductive medical experience. Fertil Steril. 2020;113:920–2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prasad S, Trivedi P, Malhotra N, Patil M, Swaminathan D, Shukla S, et al. Joint IFS-ISAR-ACE recommendations on resuming/opening up assisted reproductive technology services. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2020;13:82–8. doi: 10.4103/jhrs.JHRS_109_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan C, Lei D, Fang C, LI C, Wang M, Liu Y, et al. Perinatal transmission of COVID-19 associated SARS-CoV-2: Should we worry? Clin Infect Dis 2020. ciaa226. Advance online publication. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa226. Doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa226.

- 14.Gajbhiye R, Modi D, Mahale S. Pregnancy Outcomes, Newborn Complicaions and Maternal-Fetal Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in Women with COVID-19: A Systematic Review of 441 Cases. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.11.20062356v2 .

- 15.Dubey P, Reddy SY, Manuel S, Dwivedi AK. Maternal and neonatal characteristics and outcomes among COVID-19 infected women: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;252:490–501. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dang D, Wang L, Zhang C, Li Z, Wu H. Potential effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy on fetuses and newborns are worthy of attention. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2020;46:1951–7. doi: 10.1111/jog.14406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vivanti AJ, Vauloup-Fellous C, Prevot S, Zupan V, Suffee C, Do Cao J, et al. Transplacental transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3572. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17436-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arav A. A recommendation for IVF lab practice in light of the current COVID-19 pandemic. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37:1543. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01841-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anifandis G, Messini CI, Daponte A, Messinis IE. COVID-19 and fertility: A virtual reality. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;41:157–9. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maggiulli R, Giancani A, Fabozzi G, Dovere L, Tacconi L, Amendola MG, et al. Assessment and management of the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in an IVF laboratory. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;41:385–94. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pomeroy KO, Schiewe MC. Cryopreservation and IVF in the time of Covid-19: What is the best good tissue practice (GTP) J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37:2393–8. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01904-5. Doi: 101007/s10815-020-01904-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stanley KE, Thomas E, Leaver M, Wells D. Coronavirus disease-19 and fertility: Viral host entry protein expression in male and female reproductive tissues. Fertil Steril. 2020;114:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan F, Xiao X, Guo J, Song Y, Li H, Patel DP, et al. No evidence of SARS-CoV-2 in semen of males recovering from COVID-19. Fertil Steril. 2020;98:870–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li D, Jin M, Bao P, Zhao W, Zhang S. Clinical characteristics and results of semen tests among men with coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e208292. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corona G, Baldi E, Isidori AM, Paoli D, Pallotti F, de Santis L, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection, male fertility and sperm cryopreservation: A position statement of the Italian Society of Andrology and Sexual Medicine (SIAMS) (Società Italiana di Andrologia e Medicina della Sessualità) J Endocrinol Invest. 2020;43:1153–7. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01290-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weatherbee BA, Glover DM, Zernicka-Goetz M. Expression of SARSCoV-2 receptor ACE2 and the protease TMPRSS2 suggests susceptibility of the human embryo in the first trimester. Open Biol. 2020;10:200162. doi: 10.1098/rsob.200162. doi: 10.1098/rsob.200162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colaco S, Chhabria K, Singh D, Bhide A, Singh N, Singh A, et al. A single-cell RNA Expression Map of Coronavirus Receptors and Associated Factors in Developing Human Embryos. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 22]. Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.04935 .

- 28.Ashray N, Bhide A, Chakarborty P, Colaco S, Mishra A, Chhabria K, et al. Single-Cell RNA-seq identifies cell subsets in human placenta that highly expresses factors to drive pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:783. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh M, Bansal V, Feschotte C. A single-cell RNA expression map of human coronavirus entry factors. Cell Rep. 2020;32:108175. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shinde P, Gaikwad P, Gandhewar M, Ukey P, Bhide A, Patel V, et al. Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in the first trimester placenta leading to vertical transmission and fetal demise from an asymptomatic mother. (Preprint) medRxiv. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa367. 2020.08.18.20177121; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.18.20177121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alviggi C, Esteves SC, Orvieto R, Conforti A, La Marca A, Fischer R, et al. POSEIDON (Patient-Oriented Strategies Encompassing IndividualizeD Oocyte Number) group. COVID-19 and assisted reproductive technology services: Repercussions for patients and proposal for individualized clinical management. Version 2. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2020;18:45. doi: 10.1186/s12958-020-00605-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strategy for COVID19 Testing in xxxx (Version 4, dated 09/04/2020) [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 18]. Available from: https://www.icmr.gov.in/pdf/covid/strategy/Strategey_for_COVID19_Test_v4_09042020.pdf .

- 33.Strategy for COVID-19 Testing in xxxx Version 5 dated 18/5/20. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 18]. Available from: https://www.icmr.gov.in/pdf/covid/strategy/Testing_Strategy_v5_18052020.pdf .

- 34.de Santis L, Anastasi A, Cimadomo D, Klinger FG, Licata E, Pisaturo V, et al. COVID-19: The perspective of Italian embryologists managing the IVF laboratory in pandemic emergency. Hum Reprod. 2020;35:1004–5. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Papathanasiou A. COVID-19 screening during fertility treatment: How do guidelines compare against each other? J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37:1831–5. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01885-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.COVID Risk Assessment form Patient. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 18]. Available from: http://www.isarindia.net/covid-19/COVID%20RISK%20ASSESSMENT%20TRIAGE%20%20FORM%20PATIENT-25.05.pdf .

- 37.Micro Plan for Containing Local Transmission of Coronavirus Disease (COVID19) [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 19]. Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/ModelMicroplanforcontainmentoflocaltransmissionofCOVID19.pdf .

- 38.Haefeli M, Elfering A. Pain assessment. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(Suppl 1):S17–24. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-1044-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.ESHRE Special Interest Group of Embryology; Alpha Scientists in Reproductive Medicine. The Vienna Consensus: Report of an Expert Meeting on the Development of art Laboratory Performance Indicators. Hum Reprod Open. 2017;2017:ho×011. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hox011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vaughan DA, Shah JS, Penzias AS, Domar AD, Toth TL. Infertility remains a top stressor despite the COVID-19 pandemic. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;41:425–7. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lintsen AM, Verhaak CM, Eijkemans MJ, Smeenk JM, Braat DD. Anxiety and depression have no influence on the cancellation and pregnancy rates of a first IVF or ICSI treatment. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:1092–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quant HS, Zapantis A, Nihsen M, Bevilacqua K, Jindal S, Pal L. Reproductive implications of psychological distress for couples undergoing IVF. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013;30:1451–8. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0098-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boivin J, Harrison C, Mathur R, Burns G, Pericleous-Smith A, Gameiro S. Patient experiences of fertility clinic closure during the COVID-19 pandemic: Appraisals, coping and emotions. Hum Reprod. 2020;35:2556–66. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Romanski PA, Bortoletto P, Rosenwaks Z, Schattman GL. Delay in IVF treatment up to 180 days does not affect pregnancy outcomes in women with diminished ovarian reserve. Hum Reprod. 2020;35:1630–6. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith AD, Gromski PS, Rashid KA, Tilling K, Lawlor DA, Nelson SM. Population implications of cessation of IVF during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;41:428–30. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Esteves SC, Carvalho JF, Martinhago CD, Melo AA, Bento FC, Humaidan P, et al. Estimation of age-dependent decrease in blastocyst euploidy by next generation sequencing: development of a novel prediction model. Panminerva Med. 2019;61:3–10. doi: 10.23736/S0031-0808.18.03507-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hickman C, Rogers S, Huang G, MacArthur S, Meseguer M, Nogueira D, et al. Managing the IVF laboratory during a pandemic: International perspectives from laboratory managers. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;41:141–50. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khan S, Liu J, Xue M. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2, Required Developments in Research and Associated Public Health Concerns. Front Med. 2020;7:310. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dyer SJ, Vinoos L, Ataguba JE. Poor recovery of households from out-of-pocket payment for assisted reproductive technology. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:2431–6. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hornstein MD. Lifestyle and IVF outcomes. Reproduct Sci (Thousand Oaks, Calif) 2016;23:1626–9. doi: 10.1177/1933719116667226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meldrum DR. Introduction: Obesity and reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2017;107:831–2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.02.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khalili MA, Leisegang K, Majzoub A, Finelli R, Panner Selvam MK, Henkel R, et al. Male fertility and the COVID-19 pandemic: Systematic review of the literature. World J Mens Health. 2020;38:506–20. doi: 10.5534/wjmh.200134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.La Marca A, Nelson SM. SARS-CoV-2 testing in infertile patients: Different recommendations in Europe and America. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37:1823–8. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01887-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Newer Additional Strategies for COVID Testing. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug18]. Available from: http://health.delhigovt.nic.in/wps/wcm/connect/feb8c0804ec7c627a4e7a55dc9149193/ICMR.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&lmod=-341573094&CACHEID=feb8c0804ec7c627a4e7a55dc9149193 .

- 55.La Marca A, Capuzzo M, Paglia T, Roli L, Trenti T, Nelson S. Testing for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): A systematic review and clinical guide to molecular and serological in vitro diagnostic assays. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;41:483–99. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cevik M, Bamford CG, Ho A. COVID-19 pandemic-a focused review for clinicians. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:842–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yasmin E, Dresner M, Balen A. Sedation and anaesthesia for transvaginal oocyte collection: An evaluation of practice in the UK. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2942–5. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Singhal H, Premkumar PS, Chandy A, Kunjummen AT, Kamath MS. Patient experience with conscious sedation as a method of pain relief for transvaginal oocyte retrieval: A cross sectional study. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2017;10:119–23. doi: 10.4103/jhrs.JHRS_113_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kwan I, Wang R, Pearce E, Bhattacharya S. Pain relief for women undergoing oocyte retrieval for assisted reproduction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5:CD004829. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004829.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gianaroli L, Ata B, Lundin K, Rautakallio-Hokkanen S, Tapanainen JS, Vermeulen N, et al. ESHRE COVID-19 Working Group. The calm after the storm: re-starting ART treatments safely in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Hum Reprod. 2020 doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa285. deaa285. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa285. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]