Abstract

The United States is 25 years into a large-scale drug overdose epidemic, yet its consequences for gender differences remain largely unexplored. This study finds that drug overdose mortality increased seven- and fivefold for men and women, respectively; accounts for 0.8-year (men) and 0.4-year (women) deficits in life expectancy at birth in 2017; and has made an increasing contribution (from 1 percent to 17 percent) to women’s life expectancy advantage at the prime adult ages between 1990 and 2017. I document a distinctive cyclicality to sex differences in drug overdose. During the epidemic’s early stages – the heyday of prescription opioids – gender differences narrowed, but once the epidemic transitioned to illicit drugs in 2010, gender differences widened again. This pattern holds across racial/ethnic groups, and in fact may be even stronger among Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks than among non-Hispanic Whites. That we observe this gender dynamic across racial/ethnic groups is surprising since very different trends in drug overdose mortality have been observed for Whites versus other groups. The contemporary epidemic is a case of dynamic change in gender differences, and the differential mortality risks experienced by men and women reflect gendered social norms, attitudes towards risk, and patterns of diffusion.

Introduction

Gender differences in drug use and its consequences are remarkably fluid, strongly patterned by social and institutional forces, and have shifted dramatically over time. These differences have in turn shaped the size of and changes in life expectancy differentials between men and women. The classic example of a substance use that has had an outsize impact on mortality differentials is cigarette smoking, widely acknowledged to be the single largest contributor to trends in gender differences in mortality in high-income countries (Oksuzyan et al. 2008; Pampel 2001; Waldron 1993). For example, gender differences in smoking were the key determinant of the widening and subsequent narrowing of mortality differences between American men and women that has occurred since the 1950s (Preston and Wang 2006). While gender differences in smoking have narrowed, a new group of substances – opioids – has recently emerged with the potential to reconfigure sex differences in drug use and mortality.

Over the past two and a half decades, drug overdose has reached unprecedented levels in the United States, to the point where deaths from drug overdose now outnumber those from motor vehicle accidents and homicide combined, amounting to over 70,000 deaths in 2017 alone (Hedegaard, Miniño, and Warner 2018). Initially driven by a massive escalation in the use of prescription opioid painkillers, the epidemic shifted to illicit substances like heroin and fentanyl after 2010 (Paulozzi et al. 2011; Guy et al. 2017; CDC 2018). Over the decade of the 1990s, powerful prescription opioids transformed from being a drug of last resort used primarily in cancer and end-of-life care to being widely prescribed for many different conditions including standard elective surgeries, sports injuries, back pain, and wisdom tooth extraction (Meier 2003; Macy 2018; van Zee 2009). Several interrelated factors contributed to this monumental change including the modern hospice movement and demands for increased attention to treating pain; pharmaceutical companies’ aggressive marketing and promotional techniques used to create and expand markets for prescription opioids; and institutional features of the American medical establishment including increasing constraints on physicians’ time with patients, tying payment to patient satisfaction scores, limited training in pain medicine, and insurance companies’ policies favoring coverage of drug therapies over alternative pain treatments and of opioids over non-opioids (IOM 2011; Macy 2018; Meier 2003; Mezei and Murinson 2011; Thomas and Ornstein 2017; U.S. Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee 2018; Van Zee 2009). Following increasing recognition of the epidemic and efforts to curtail opioid prescribing, including the release of an abuse-deterrent formulation of the prescription opioid OxyContin in 2010, heroin and other illicit drugs became increasingly important drivers of drug overdose. Drug overdose mortality has increased rapidly since 2010 and particularly since 2013, when the synthetic opioid fentanyl, which is 50 times more powerful than heroin, began entering the illicit drug supply (CDC 2018; Hedegaard et al. 2018).

Drug overdose mortality has now reached such high levels that it makes tangible contributions to life expectancy declines in the United States (Ho and Hendi 2018) and to the U.S. life expectancy shortfall relative to other high-income countries (Ho 2019). Several studies have documented large differences in drug overdose mortality within the United States by race/ethnicity (Alexander, Barbieri, and Kiang 2018), education (Ho 2017), urban/rural residence (Paulozzi and Xi 2008; Rigg, Monnat, and Chavez 2018), and region (Elo et al. 2019). However, no prior studies have undertaken an in-depth analysis of how sex differences in drug overdose mortality have changed in recent decades over the course of the contemporary American drug overdose epidemic. There is a general understanding that men have higher levels of drug overdose mortality but that women have had a more rapid rate of increase (during certain periods), and that many diverse factors are expected to contribute to gender differences in drug overdose (Mack, Jones, and Paulozzi 2013; Mazure and Fiellin 2018). However, our understanding of how and why gender differences in drug overdose mortality have changed over the course of the epidemic, as well as their connections to age patterns and the substances implicated in these deaths, remains limited.

Examining sex differences in drug overdose mortality not only sheds light on the contours of the contemporary epidemic – who is most affected, at which points in time or at which stages of the epidemic, and why – but also on broader questions regarding how social forces are structuring gender differences in life expectancy in today’s society. The epidemic has reached all corners of the country and resulted in unprecedented levels of drug overdose mortality; however, the epidemic has played out quite differently for men and women, resulting in dramatic shifts in gender differences in drug-related mortality within the space of a few decades. The epidemic serves as a lens that magnifies the social norms, institutions, attitudes towards risk, and patterns of the diffusion of innovations that shape how men and women respond to new social phenomena and, consequently, their differential vulnerability to their mortality risks. Thus, this paper examines: 1) how gender differences in drug overdose mortality changed over the course of the epidemic; 2) the factors underlying these trends; and 3) the epidemic’s implications for sex differences in life expectancy.

Background

Gender and the contemporary epidemic

The pathway from drug use to dying from an overdose is complex, and we can think of gender differences in mortality from drug overdose as reflecting three interrelated dimensions of use: exposure to substances, levels of use, and riskiness of use. These are in turn shaped by a wide array of broader factors including socioeconomic status, social norms, access to health care, social networks, and occupational conditions.

The extent to which individuals are more or less exposed to specific substances is influenced by several characteristics including age, gender, birth cohort, socioeconomic status, and urban/rural residence. One of the most obvious examples of gender structuring differential experiences is military service, which remains a predominantly male activity. Opioid epidemics have occurred periodically in the United States over the past two centuries, and at least two of them were concentrated among soldiers who had served in wars and became addicted to opioids – morphine during the Civil War and heroin during the Vietnam War. Cigarette use ramped up dramatically among World War I combatants, and cigarettes were included as part of soldiers’ rations during World War II (Courtwright 2001). When substances first appear or experience a resurgence in popularity, they tend to diffuse first among men. This pattern has historically been observed for both legal drugs (e.g., cigarettes) and illicit drugs (e.g., crack cocaine)1 (Pampel 2001; Waldron, McCloskey, and Earle 2005).

In terms of levels of use (i.e., how prevalent or widespread drug use is among men and women), most surveys find higher rates of substance use among men than women. Figure 1 presents reported use of illicit substances and nonmedical use of prescription drugs from the 2015–2017 waves of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). The percent of men who report (mis)using these substances exceeds the percent of women for every substance. Even in the case of legal substances for which we have observed substantial convergence between men and women, such as cigarettes and alcohol, complete convergence is rarely achieved. For example, the age-standardized prevalence of ever smoking peaked at 72 percent of men in 1974 and 47 percent of women in 1985 (author’s calculations based on the National Health Interview Survey [Blewett et al. 2019]). Even in their peak smoking year, women have never matched the levels of cigarette smoking observed among men. There is some evidence that the motivations for drug use differ for men and women, with men being relatively more likely to use drugs for pleasure or recreational purposes and women being relatively more likely to use drugs as a coping mechanism in response to stress, negative emotions, and psychological distress (Back et al. 2010; Choo, Douriez, and Green 2014; Jamison et al. 2010; McHugh et al 2013).

FIGURE 1.

Age-Standardized Percent Ever Used or Misused Specific Substances, Men and Women Ages 12+, 2015–2017, National Survey on Drug Use and Health

It is notable that the differences shown in Figure 1 tend to be smaller for abuse of legal drugs than for illegal drugs, and they are particularly small for nonmedical use of prescription drugs. Important gender differences exist in types of drug use – men have generally been more likely to drink and smoke and to use illicit drugs recreationally, while women have been relatively more likely to use and misuse prescription drugs (Becker, McClellan, and Read 2017; Greenfield et al. 2010; Kandall 1999; Simoni-Wastila 2000; Simoni-Wastila, Ritter, and Strickler 2004). It is striking that the only epidemic that we know of in which the prevalence of drug addiction (but not necessarily mortality) was equivalent or higher among women compared to men involved laudanum and other opioids used for medical ailments in the late 1800s (Courtwright 1982; Aldrich 1994).

Finally, key gender differences in the riskiness of drug use have been documented, encompassing the method or route of drug administration, the amounts and types of drugs used, and concurrent use of multiple substances (polydrug use). Among the various methods of drug administration, intravenous drug use is regarded as more likely to lead to overdose than, for example, snorting or orally consuming substances. In general, men may be more likely to engage in riskier types of drug use that elevate mortality including taking greater amounts of drugs, using more lethal drugs, and sourcing drugs from riskier sources and unvetted dealers (U.S. DHHS 2017). Polydrug use is known to increase the risk of drug overdose due to the side effects resulting from the interactions among these substances and amplification of their effects on the body.

Combining these observations with the parameters of the present epidemic leads to several interesting questions that we set out to answer in this paper. Given that prescription painkillers – controlled substances dispensed through the health care system even if they are eventually diverted for resale to black markets – were the initial drivers of the epidemic, were women more affected than men early on? In other words, at the close of the 20th century, was the stage set for a repeat of the late 19th century, when the typical addict was characterized as a white, middle- or upper middle class, middle-aged woman addicted to opium or morphine (Courtwright 1982; Aldrich 1994)? As the contemporary epidemic evolved to encompass illegal drugs, did the burden of mortality shift increasingly to men, or did this epidemic serve as a vehicle spurring an unprecedented convergence in illicit substance use and drug-related mortality between men and women?

Data and methods

Data

Death certificate data on all deaths occurring in the United States between 1990 and 2017 come from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Multiple Cause of Death files. These files contain information on decedents’ age, sex, and race/ethnicity, as well as the underlying cause of death. Deaths from drug overdose are identified following the standard definitions used by the NCHS2 and include deaths from both licit and illicit drugs (e.g., both prescription opioids and heroin) and deaths of all intents (i.e., drug-related suicides, drug-related homicides, accidental poisonings, and drug-related deaths of undetermined intent). Three specific drugs or categories of drugs involved in drug overdose deaths were identified using the codes for contributing causes listed on the death certificate (T codes): prescription opioids, heroin, and cocaine. These data are available from 1999 onwards with the phase-in of the tenth revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10). One limitation of using the T codes is that a nontrivial proportion of drug overdose deaths do not have these codes listed on the death certificate, and there may be considerable variation across time and space as improvements in toxicology testing and reporting occur. Nevertheless, these data have the potential to be highly informative. The figures in the main paper proportionately redistribute drug overdose deaths among five categories: those that involved opioids only, heroin only, cocaine only, two or more of the three aforementioned drugs, and drugs other than the three aforementioned drugs. The percent of drug overdose deaths without any substances identified is indicated as a separate sixth category in the online Appendix Figure A1.

Population data come from the bridged-race population estimates released by the CDC/NCHS (2019). The deaths and population data are combined to produce age-specific death rates and age-standardized death rates by year, sex, and race/ethnicity using the U.S. population in 2000 as the age standard (SEER). The analyses focus on the total population (all racial/ethnic groups combined) and on the three largest racial/ethnic subgroups in the U.S. population: non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, and Hispanics.

Data on drug use and attitudes towards risk come from the 2015–2017 waves of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality 2018). The NSDUH is representative of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population aged 12 and older and serves as the key source of information on the use of illicit drugs, alcohol, and tobacco; attitudes towards and beliefs regarding substance use; and mental health issues in the United States. All estimates based on the NSDUH are age-standardized and weighted to account for complex survey design using the weights provided by the NSDUH.

Methods

One set of analyses in this paper estimates the contribution of drug overdose to sex differences in life expectancy. Life expectancy at a given age is the additional number of years an individual who has survived to that age could expect to live if she experienced the prevailing age-specific death rates for the remainder of her life. For example, life expectancy at birth in 2017 is the number of years a newborn could expect to live if she experienced the age-specific death rates observed in 2017 at each age. Because deaths from drug overdose are highly clustered at the prime adult ages, we consider sex differences in both life expectancy at birth and years of life lived between ages 20 and 64. If no deaths occurred between these ages, an individual who survived to age 20 could expect to live the full 45 years between ages 20–64. Since deaths do occur at these ages, the years of life lived between ages 20–64 ranged from 40.9–42.1 years among men and from 42.9–43.3 years among women between 1990 and 2017.

Life expectancy at birth and years of life lived between ages 20–64 are calculated for men and women in each year using standard life table methods and graduation techniques (Preston, Heuveline, and Guillot 2001). “Observed” indicates that these measures are based on the actual death rates experienced by men and women in the United States in a specific year. We are interested in comparing what we observe to a counterfactual scenario – what gender differences in these measures of mortality would look like in the absence of drug overdose. This counterfactual scenario is calculated using cause-deleted life tables. The standard assumption of cause-deleted life tables is that in the absence of drug overdose (in other words, if we could eliminate all deaths from drug overdose), within each age interval, mortality rates would have the same shape as in the observed scenario but would be shifted downwards proportionately by a factor R, where R is defined as the proportion of total deaths in that age group due to drug overdose (ibid.). This is equivalent to assuming independence across causes of death. If individuals who died of drug overdose were more likely to engage in other risky behaviors or to have other risk factors linked to elevated mortality, it is possible that the counterfactual scenario may yield overestimates of the impact of eliminating drug overdose. On the other hand, several studies indicate that a nontrivial proportion of drug overdose deaths may not be coded as such on death certificates, which would lead to underestimates of the impact of eliminating drug overdose (Glei and Preston 2020; Paulozzi et al. 2006).

The percent contribution of drug overdose to sex differences in life expectancy at birth (e0), for example, can then be calculated as the difference between the observed and the counterfactual scenarios:

The same logic applies when the outcome measure is years of life lived between ages 20–64.

Results

Gender differences in drug overdose mortality

Between 1990 and 2017, drug overdose mortality increased substantially for both men and women in the total population (Figure 2a). For men, drug overdose mortality increased almost sevenfold, from 4.18 to 29.05 deaths per 100,000 over this period. For women, it more than quintupled, increasing from 2.58 to 14.39 deaths per 100,000. Using the metric of average year-to-year increases, these increases were larger for men (10.2 percent) than women (2.3 percent) between 1990 and 1995, larger for women (8.5 percent) than men (5.6 percent) between 1995 and 2010, and larger for men (10.2 percent) than women (6.0 percent) again in the 2010s.

FIGURE 2.

Age-Standardized Drug Overdose Death Rate (per 100,000) for Men and Women, 1990–2017, Total Population (a) and by Race/Ethnicity (b)

Looking at these trends separately by race/ethnicity (Figure 2b), we see that all three racial/ethnic groups have experienced sizeable increases in drug overdose mortality. These increases were largest for non-Hispanic Whites, who initially had lower (men) or comparable (women) rates compared to non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics in the early 1990s but now have the highest drug overdose death rates. For non-Hispanic Whites, we see the same pattern of larger increases among men in the early 1990s, among women between 1995 and 2010, and among men again after 2010 that was observed for the total population. For non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics, a similar pattern is observed, but with one key difference: drug overdose mortality actually decreased for men in these two groups between 1995 and 2010, such that the drug overdose death rate was slightly lower for non-Hispanic black and Hispanic men in 2010 than in 1995. In contrast, drug overdose mortality increased for non-Hispanic black and Hispanic women between 1995 and 2010, with the rates being 56 percent and 91 percent higher in 2010 than in 1995, respectively. In both the earliest (early 1990s) and most recent (since 2010) periods, increases in drug overdose mortality were larger among men than women for these two groups.

While men experienced higher death rates than women in each year, gender differences in drug overdose mortality have changed enormously. In the early 1990s, the male/female differential was relatively small, amounting to just 1.60 deaths per 100,000. By 2017, the difference in the drug overdose death rate had increased to 14.66 deaths per 100,000, a more than nine-fold increase. However, this is no simple tale of continuous increase in gender differences over the course of the epidemic.

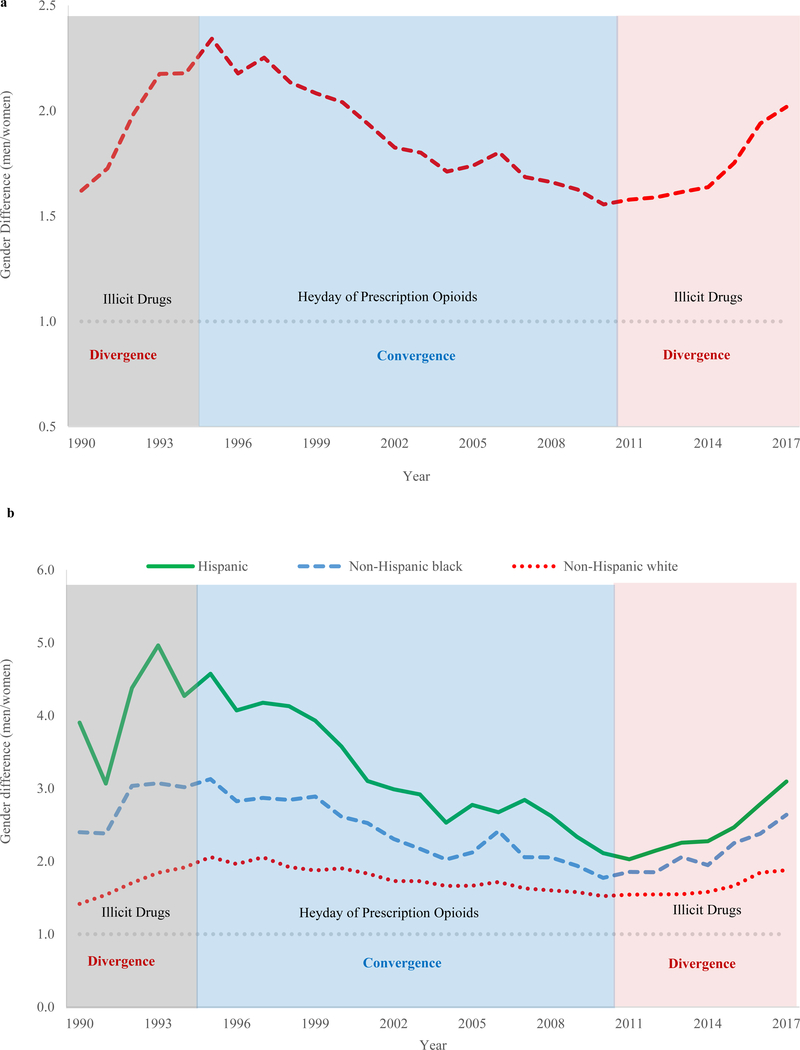

Figure 3a shows the relative difference (the ratio of men’s to women’s mortality) in drug overdose mortality for the total population between 1990 and 2017. The inflection points of this curve match up with landmark events in the course of the contemporary epidemic. The early period (early 1990s), shaded in gray, is the tail end of the crack cocaine epidemic, and it largely predates the contemporary epidemic. During this time, we saw gender differences in drug overdose widen. Subsequently, we observed a long period of gender convergence between 1995 and 2010. In other words, men’s and women’s drug overdose death rates became more similar. This was the heyday of prescription opioids. The epidemic entered a new phase around 2010, as the key drivers of the epidemic switched from prescription painkillers to heroin, illicit fentanyl3, and other drugs including cocaine and methamphetamine, coinciding with a change from decreasing to increasing gender differences in drug overdose.

FIGURE 3.

Gender Difference in Drug Overdose Death Rates (Men/Women), 1990–2017, Total Population (a) and by Race/Ethnicity (b)

Figure 3b demonstrates that this pattern of gender divergence, convergence, and divergence holds for all three racial/ethnic groups. In fact, it is somewhat more pronounced for non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics compared to non-Hispanic Whites owing to the greater relative difference, as between men and women, in drug overdose mortality in these two groups. This difference echoes that observed for other substances like smoking, where smoking prevalence and/or smoking-attributable mortality tend to be considerably lower among women than men for non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics (Ho and Elo 2013; Fenelon 2013; Holford, Levy, and Meza 2016). In the context of the contemporary epidemic, it is well-documented that racial and ethnic minorities were much less likely to be prescribed opioids than non-Hispanic Whites (Palanker 2008; Pletcher et al. 2008; Singhal, Tien, and Hsia (2016); Tamayo-Sarver et al. 2003; Terrell et al. 2010). This is reflected in the rapid increases in drug overdose mortality observed among non-Hispanic Whites since the mid-1990s (Figure 2b, see also Alexander et al. 2018).

An important interaction exists between sex and race/ethnicity. Prior studies of racial/ethnic differences in receipt of prescription opioids highlight the role of negative beliefs and expectations held by providers in driving these differences, since these studies generally find that racial/ethnic differences persist even after controlling for a wide range of sociodemographic characteristics, pain severity, and co-morbidities. Physicians tend to hold more negative perceptions of patients from racial/ethnic minority groups and may believe that they are at higher risk of abusing or becoming addicted to prescription opioids (Tamayo-Sarver et al. 2003). It is likely that these beliefs were more negative towards men than women from racial/ethnic minority groups, leading to some level of opioid prescribing for minority women (albeit lower than for non-Hispanic Whites) and even lower levels of opioid prescribing for minority men. While a fairly small number of studies have examined trends in prescribing along both racial/ethnic and gender dimensions, some have found that the racial/ethnic disparity in opioid prescribing is larger for men than women (Janakiram et al. 2019; Pletcher et al. 2008). This would be consistent with the finding in this paper that drug overdose mortality decreased among Hispanic and non-Hispanic black men, but increased among Hispanic and non-Hispanic black women, during the heyday of prescription opioids. Once the main sources of drug overdose mortality shifted to illicit drugs, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic men experienced very sharp increases in drug overdose death rates.

Gender differences in age patterns

Age is a key dimension structuring gender differences in drug overdose mortality, and the examination of age patterns of drug overdose mortality sheds additional light on this cyclical pattern of gender convergence and divergence. Figure 4 plots the age-specific death rate for three-year periods starting with 1991–1993 and ending with 2015–2017. The shading becomes progressively darker over time, such that the line corresponding to the earliest period has the lightest shading, and the line corresponding to the most recent period has the darkest shading. Three key observations hold: 1) mortality from drug overdose is strongly patterned by age for both men and women; 2) these age patterns shifted dramatically over the course of the contemporary American opioid epidemic; and 3) the patterns changed differently for men and women. Beginning with the patterns for men (Figure 4a), we see that the age distribution was unimodal in 1991–1993, which predated the contemporary epidemic. Drug overdose death rates were highest for men in their thirties, and they were fairly low at all other ages. Over time, however, the distribution broadened first to older ages and then to younger ages, eventually becoming bimodal. What is particularly interesting is that we can identify two distinct regimes in the age patterns, separated by the leadup to the 2010 turning point. The solid lines constitute the pre-2010 regime, where we see the peak in men’s drug overdose mortality getting older and older over time. The dashed lines are the post-2010 lines, where we observe substantial increases in drug overdose mortality at younger ages, particularly for men in their twenties.

FIGURE 4.

Age-Specific Drug Overdose Death Rates (per 100,000) for Men (a) and Women (b), 1991–2017

An examination of the patterns for women (Figure 4b) reveals a very different story. For women, the distribution maintained a single peak, and it moved to progressively older and older ages over time. This indicates that peak drug overdose death rates were shifting in line with a specific subset of female birth cohorts. The highest death rates among women were observed for the age group 40–44 in 1994–2002, then 45–49 in 2003–2011, and finally 50–54 in 2012–2017. The corresponding birth cohorts are women who were born roughly between 1950 and 1967, which overlap with what are commonly considered the baby boom cohorts born between 1946 and 1964 (Colby and Ortman 2014; Hogan, Perez, and Bell 2008). In terms of differences between men and women, the most striking contrast is that we observe only a single regime for women, not the two observed for men – in other words, the distinct break around 2010 is observed for men, but not for women. This is likely linked to the transition from prescription opioids to heroin and other illicit drugs that occurred in 2010.

Gender differences in substances involved in drug overdose deaths

Figure 5 plots the share of drug overdose deaths accounted for by specific categories of substances involved: (1) those that involved prescription opioids only; (2) heroin only; (3) cocaine only; (4) two or more of these three substances (an indicator of polydrug use); and (5) drugs other than opioids, heroin, or cocaine. Each bar shows the distribution of deaths in a given year, such that all of the bars in a column add up to 100 percent.

FIGURE 5.

Distribution of Drug Overdose Deaths by Substance(s) Involved, Men (a) and Women (b), 1999–2017

Note: Drug overdose deaths with no substance specified were distributed proportionately to the other categories in this figure. See Appendix Figure A1 for figures that include the proportion of drug overdose deaths with no substance specified as a sixth category.

For example, we see that among all of the male drug overdose deaths (Figure 5a) in 2017, which corresponds to the rightmost bar, 38 percent involved opioids only, 9 percent involved heroin only, and 7 percent involved cocaine only. Over a quarter (29 percent) involved two or more of these drugs, and the remaining 16 percent of deaths involved other drugs. Between 1999 and 2009, the dominant trend is the increase in the share of drug overdose deaths involving opioids only. From 2010 onwards, the share of deaths involving opioids only fell, while the shares of deaths involving heroin and multiple drugs rose rapidly. We observe two key differences between men and women (Figure 5b). First, the share of deaths involving opioids only is higher for women than men for most of the period, while the shares involving cocaine and heroin are much lower. Second, these figures suggest that polydrug use is much more common – or more commonly leads to death – among men compared to women.

The contribution of drug overdose to gender differences in life expectancy

The contemporary epidemic is having discernible impacts on life expectancy for both men and women. In 2017, life expectancy at birth would have been 0.78 years and 0.42 years higher for men and women, respectively, in the absence of drug overdose. The epidemic also has important implications for sex differences in life expectancy.

The increasing contribution of drug overdose to gender differences in life expectancy is apparent in Figure 6. We examine two measures: life expectancy at birth and years of life lived between ages 20–64, the age range in which drug overdose mortality is highest and in which we would expect it to be making the largest contribution. Beginning with life expectancy at birth, we see that between 1990 and 2017, the number of years by which women outlive men declined from 7.10 years to 5.07 years. In the absence of drug overdose, sex differences in life expectancy would generally have been smaller and narrowed faster, which is expected given that men have had higher levels of drug overdose mortality than women throughout the period. For example, in 2017, the difference in life expectancy at birth between men and women would have been 0.35 years smaller in the absence of drug overdose (4.71 vs. 5.07 years). The contribution of drug overdose to these differences has increased fairly steadily over time. In 1990, it made a minimal contribution – only 0.4 percent – to the gender difference in life expectancy. By 2017, however, its contribution had increased to 7.0 percent, an eighteen-fold increase.

FIGURE 6.

Gender Difference in Life Expectancy at Birth and Years of Life Lived Between Ages 20–64, Observed and Counterfactual Scenarios, 1990–2017

The contribution of drug overdose to gender differences in mortality is particularly striking at the prime adult ages (20–64). Overall, the story is similar to that for life expectancy at birth: male-female differences in years of life lived have decreased over time, and the contribution of drug overdose, which was initially negligible, has taken on increasing importance within a fairly short period of time. Drug overdose accounted for only 1.4 percent of the gender difference in years of life lived between ages 20–64 in 1990; by 2017, it was accounting for nearly a fifth (17.3 percent) of this difference. Another interesting observation is that following rapid declines in the 1990s, progress in narrowing gender differences in mortality slowed substantially. In fact, signs of widening gender differences have been observed from 2013 onwards. In the absence of drug overdose, these upticks would still have occurred, but would have been much more muted.

Discussion

Within the past 25 years, drug overdose has increased dramatically to become one of the key influences on American mortality. The contemporary drug overdose epidemic has resulted in substantial increases – on the order of seven- and five-fold increases – in drug overdose mortality for both men and women. In 2017, life expectancy at birth was 0.8 and 0.4 years lower than it would have been in the absence of drug overdose mortality for men and women, respectively. These life expectancy losses are substantial. By the metric of the rate of increase in best-practice life expectancy (i.e., the highest life expectancy observed worldwide in a given year), we could expect life expectancy to increase by 2.5 years per decade or 0.25 years per year (Oeppen and Vaupel 2002). Thus, these 0.8- and 0.4-year deficits are equivalent to losing roughly two to three years’ worth of life expectancy increases.4 Another consequence of the epidemic is the growing contribution of drug overdose to sex differences in life expectancy. In the early 1990s, drug overdose contributed very little to women’s life expectancy advantage. By 2017, however, higher drug overdose mortality among men relative to women accounted for 17 percent of women’s life expectancy advantage at the prime adult ages (20–64).

However, the story has not been a simple one of men being more affected than women or of drug overdose mortality moving in lockstep for both men and women. Instead, we document a distinctive cyclicality to gender differences in drug overdose linked to the nature of the substances accounting for the majority of drug overdose deaths and how these substances have diffused among men and women. Prior to the contemporary epidemic, American cities were in the throes of the crack cocaine epidemic, and gender differences in drug overdose mortality were widening. Once the current epidemic began, however, we observed a long period of narrowing male-female differences in drug overdose mortality. This was the period during which overprescribing of opioid painkillers was in its heyday. The age patterns of drug overdose mortality were altered similarly for men and women, with a shift towards older ages. In 2010, however, the epidemic changed from being primarily driven by prescription painkillers to being driven by illicit drugs like heroin and fentanyl, and gender dynamics shifted accordingly. A 15-year period of convergence ended, and we again observed divergence in men’s and women’s drug overdose death rates. Once similar, the age profiles of drug overdose mortality diverged substantially for men and women. Men’s age profile of drug overdose mortality became significantly younger, while women maintained an older age profile. These cycles of convergence and divergence are clearly tied to the nature and legality of the substances involved and, as a result, to differences in men’s and women’s propensity to use these substances and their risks of dying from drug overdose.

The early stage of the epidemic: convergence

The fact that the contemporary epidemic was initially driven by legal drugs – prescription painkillers – is the most likely explanation for the convergence in drug overdose mortality between men and women. Women have higher levels of prescription drug use, and between illicit and licit drugs, they are relatively more likely to misuse prescription drugs, especially narcotic analgesics and tranquilizers, than men (Mack 2013; Mazure and Fiellin 2018; Simoni-Wastila et al. 2004). Studies have documented higher rates of prescription opioid use among women over the course of the contemporary epidemic (Campbell et al. 2010; Kuo et al. 2016; Miller and Moriya 2018). Several factors may contribute to this phenomenon. Women have a greater prevalence of pain-related chronic conditions, reflected in their use of prescription opioid pain medications for longer periods and in higher doses (Campbell et al. 2010; Case and Paxson 2005; U.S. DHHS 2017). Women and men may also express pain differently in response to social norms and gender role expectations (e.g., men may be expected to be more “stoic”) or as a result of biological differences (Greenspan et al. 2007). Physicians and other health care providers may interpret the presentation of pain and treat pain differently in men and women. On the one hand, physicians may take complaints of pain symptoms from men more seriously than complaints from women; on the other hand, physicians may believe that men are more likely to abuse prescription drugs than women (Hoffmann and Tarzian 2001). In addition, there is a long history of physicians’ greater propensity to prescribe psychoactive drugs and particularly tranquilizers to women, dating back at least to the high levels of prescribing for women of opium and morphine in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Valium in the 1960s and 1970s, and various benzodiazepines in the era leading up to and overlapping with the contemporary epidemic (Courtwright 1982; Herzberg 2006; Olfson, King, and Schoenbaum 2015). These patterns partly reflect gendered power dynamics between physicians and their patients, as well as the use of drugs as a form of social control (Koumjian 1981). Women have greater overall health care utilization than men, which would result in more opportunities for them to be prescribed opioids. They also have greater access to health care as measured by health insurance coverage. Between 1987 and 2005, the percentage of men not covered by any type of health insurance was 1.9–3.6 percent higher than for women (U.S. Census Bureau 2016). Greater health insurance coverage facilitates more frequent doctor visits and conveys greater ability to pay for prescription drugs.

Of course, simply being prescribed prescription opioids does not necessarily lead to drug addiction or dying from drug overdose. Women had higher rates of being prescribed opioids, but men still had higher absolute levels of drug-related mortality during this period. Gender differences in mortality likely reflect differences in how the drugs were taken and particularly the riskiness of use. For example, women are more likely to hoard unused medications or to use other medications to achieve analgesic effects, whereas men are more likely to take the medication in a form other than prescribed (e.g., crushing and snorting pills) and to engage in polydrug use (Back et al. 2010; 2011a; 2011b).

The later stage of the epidemic: divergence

Growing recognition of the drug overdose epidemic led to restrictions on opioid prescribing, the release of an abuse-deterrent formulation of OxyContin in 2010, and a shift in drug use from prescription opioids to street drugs – primarily heroin but also methamphetamine, cocaine, and illicit fentanyl, among others. From 2010 onwards and particularly after 2014, drug overdose mortality increased much more rapidly among men than women, resulting in a widening of gender differences. Women’s reluctance or lower propensity to use illegal drugs likely plays a pivotal role in this divergence. Since 2010, the illegal drug supply has become increasingly contaminated by illicit fentanyl, which is extremely potent. Users are often unaware of or unable to determine whether the drugs they are consuming have been adulterated with illicit fentanyl, leading to high risks of overdose and death. Illicit fentanyl contamination has been observed for heroin, methamphetamine, and cocaine (Jones, Einstein, and Compton 2018).

In this period, women addicted to prescription opioids may have been less likely to switch to illicit drugs than their male counterparts due to: 1) greater stigma towards illicit drug use among women, 2) women placing a higher value placed on the perceived safety of prescription versus illicit drugs, and 3) the risks associated with engaging in illicit drug use that may be particular to or more prevalent among women such as physical and sexual violence (Becker et al. 2017; Macy 2018; Marshall et al. 2008). The general consensus is that gender differences exist in many aspects of risk-taking behavior, including aggression, thrill seeking, and risk acceptance. These differences have been observed in many arenas and are reflected, for example, in the high incidence of motor vehicle accidents among young men (Turner and McClure 2003). Figure 7 shows the prevalence of engaging in various risky behaviors and attitudes towards risk using the 2015–2017 waves of the NSDUH. Men were significantly more likely than women to report driving under the influence of alcohol and to forego wearing a seatbelt either when driving or riding in the front passenger seat. They were also significantly more likely to report that they sometimes or always “get a real kick out of doing dangerous things” and like to test themselves by doing risky things.

FIGURE 7.

Prevalence of Risky Behaviors and Attitudes Towards Risk, Men and Women Ages 12+, 2015–2017, National Survey on Drug Use and Health

Men and women also differ in how risky they perceive drug use to be. Figure 8 shows the percent of men and women reporting that there is moderate or great (versus no or slight risk) associated with engaging in various types of substance use in the 2015–2017 waves of the NDSUH. For all of the substances, women were more likely to report that there are moderate or great risks associated with substance use than men. For several of these substances, multiple questions were asked varying the frequency or level of use. For example, individuals were asked to rate the level of risk associated with having four to five drinks once or twice a week and with having four to five drinks daily. What is particularly interesting is that gender differences in risk assessment tend to be larger at lower frequencies or levels of substance use. For example, 95 percent of women and 89 percent of men believe having four to five drinks daily is fairly risky – a 6 percentage point difference – but 85 percent of women and 74 percent of men believe having four to five drinks once or twice a week is risky – an 11 percentage point difference. A similar pattern is observed for cocaine use, where the male-female difference nearly triples when using cocaine once a month versus once or twice a week are compared. In other words, men tend to rate drug use as less risky than women, particularly at intermediate levels or frequencies of use. These assessments likely manifest in differences between men and women in how they use drugs. Men are more likely to engage in riskier types of drug use that elevate mortality including polydrug use, using greater amounts of drugs, using more risky drugs, using drugs more frequently, and/or obtaining drugs from riskier sources – a particularly important concern in the post-2013 period when the lacing of various street drugs with illicit fentanyl has resulted in very high rates of drug overdose mortality (U.S. DHHS 2017).

FIGURE 8.

Beliefs About the Riskiness of Drug Use, Men and Women Ages 12+, 2015–2017, National Survey on Drug Use and Health

Care seeking and substance abuse treatment

A final domain concerns whether conditional on drug use or addiction, there are sex differences in access to, or taking advantage of access to, treatment for overdoses or substance abuse exist. It is unclear whether there are gender differences in the likeliness to seek emergency medical attention following an overdose. Prior evidence suggests that men may be more likely to help female victims, whereas women are equally likely to help victims of either sex during emergencies (Tobin, Davey, and Latkin 2005). One study of overdoses in Baltimore found that the sex of the individual who overdosed was not a significant predictor of whether bystanders called 911, but having any female bystanders present or ever having witnessed a fatal overdose increased the likelihood of calling 911 (ibid.). Naloxone is an opioid antagonist which can reverse the effects of opioid overdoses (thus reducing the risk of dying) and constitutes an important component in emergency medical service response to overdoses. One study has documented gender differences in the likelihood of naloxone administration in Rhode Island, finding that women were three times more likely to not receive naloxone than men (Sumner et al. 2016). One potential explanation for this finding may be the expectation that women will be less likely to use drugs than men.

Men and women may also have different thresholds for and experience different barriers to seeking treatment for substance abuse. A recent study found no significant gender differences in the age at onset of regular use of opioids, cannabis, or alcohol; however, women entered treatment earlier (i.e., after fewer years of regular use of these drugs) than men (Hernandez-Avila et al. 2004). This has been interpreted as women having quicker development of dependence but could also reflect a greater willingness to seek treatment. Research on sex differences in treatment success using large, population-representative samples is scarce (Petry and Bickel 2000).

Women who are addicted to drugs and become pregnant will necessarily be in contact with the health care system, at least at the point of delivery if not earlier, and this typically results in their being treated for addiction either during their pregnancy or following the delivery. There is no analogous point of entry into substance abuse treatment for men. However, women may face particular barriers to accessing substance abuse treatment (U.S. DHHS 2017). For example, women with children may be less likely to seek substance abuse treatment for fear that they may lose custody of their children. Maintaining abstinence from drug use is often facilitated by having social support. While women are generally regarded as having stronger social networks than men, which may be protective in terms of reducing the harmful consequences of drug use, there may be important differences in the sources of and levels of social support received by men and women in the specific domain of abstinence from drug use. Prior studies have found that men tend to receive more social support for maintaining abstinence at home and in the workplace, whereas women tend to receive less support in maintaining abstinence from their partners, resulting in higher risks of relapse (Becker et al. 2017).

Conclusion

The contemporary American drug overdose epidemic highlights a case of dynamic change in gender differentials rather than a straightforward narrative of convergence. In this paper, we found an initial narrowing of male-female differences during the heyday of prescription opioids, followed by a widening of gender differences in drug overdose mortality once the epidemic transitioned to illicit drugs. In other words, when prescription painkillers were the primary drivers of drug overdose deaths, gender differences narrowed, but when illegal drugs became the primary drivers, male-female differences widened. These findings raise two policy-important questions. First, are these processes of divergence and convergence occurring more or less rapidly than the processes we have observed occurring for other substances (e.g., cigarette smoking, alcohol, and cannabis)? Second, following the sharp rise in drug overdose mortality among men since 2010, will we eventually see women again catching up to men, or will men’s mortality disadvantage in this area persist? How long will it be until we encounter the next stage of what appears to be an enduring cycle in gender differences in drug overdose mortality?

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Arun Hendi, an anonymous reviewer, and the editor for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper.

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD) of the National Institutes of Health under Grant R00 HD083519 and the National Institute on Aging (NIA) of the National Institutes of Health under Grant R01 AG060115. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Crack cocaine is a free base form of cocaine that first saw widespread use beginning in the early 1980s.

These are deaths for which the underlying cause of death was ICD-9 codes E850–E858, E950.0–E950.5, E962.0, or E980.0–E980.5 prior to 1999 and ICD-10 codes X40–X44, X60–X64, X85, and Y10–Y14 from 1999 onward.

Pharmaceutical fentanyl is a very powerful synthetic opioid pain reliever with legitimate medical uses. Law enforcement reports indicate that the fentanyl implicated in drug overdose deaths is illicitly-made fentanyl sourced mainly from China and Mexico (thus, we refer to this as illicit fentanyl throughout this paper) (US Congress 2018).

These are likely to be underestimates given that the United States has not been able to attain anything close to a life expectancy increase of 0.25 years per year in recent decades.

References

- Aldrich Michael R. 1994. “Historical Notes on Women Addicts.” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 26(1): 61–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander Monica J., Kiang Matthew, and Barbieri Magali. 2018. “Trends in Black and White Opioid Mortality in the United States, 1979–2015.” Epidemiology 29(5), 707–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back Sudie E., Payne Rebecca L., Simpson Annie N., and Brady Kathleen T.. 2010. “Gender and prescription opioids: Findings from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.” Addictive Behaviors 35: 1001–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back Sudie E., Payne Rebecca L., Amy Herrin Wahlquist Rickey E. Carter, et al. 2011a. “Comparative Profiles of Men and Women with Opioid Dependence: Results from a National Multisite Effectiveness Trial.” The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 37(5): 313–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back Sudie E., Lawson Katie M., Singleton Lauren M., Brady Kathleen T.. 2011b. “Characteristics and correlates of men and women with prescription opioid dependence.” Addictive Behaviors 36: 829–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker Jill B., McClellan Michele L., and Beth Glover Reed. 2017. “Sex differences, gender and addiction.” Journal of Neuroscience Research 95(1–2): 136–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blewett Lynn A., Drew Julia A. Rivera, King Miriam L. and Williams Kari C.W. IPUMS Health Surveys: National Health Interview Survey, Version 6.4 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2019. 10.18128/D070.V6.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell Cynthia I., Weisner Constance, Linda LeResche, Ray G. Thomas, et al. 2010. “Age and Gender Trends in Long-Term Opioid Analgesic Use for Noncancer Pain.” American Journal of Public Health 100: 2541–2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case Anne, and Paxson Christina. 2005. “Sex differences in morbidity and mortality.” Demography 42(2): 189–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2018. Synthetic Opioid Overdose Data. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/fentanyl.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)/National Center for Health Statistics. 2018. U.S. Census Populations With Bridged Race Categories. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/bridged_race.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2019. CDC Wonder. http://wonder.cdc.gov/. September 2019.

- Choo Esther K., Douriez Carole, and Green Traci. 2014. “Gender and Prescription Opioid Misuse in the Emergency Department.” Academic Emergency Medicine 21:1493–1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby Sandra L., and Ortman Jennifer M.. 2014. The Baby Boom Cohort in the United States: 2012 to 2060. Current Population Reports, P25–1141. U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Courtwright David T. 1982. Dark Paradise A History of Opiate Addiction in America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Courtwright David T. 2001. Forces of Habit: Drugs and the Making of the Modern World. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elo Irma T., Hendi Arun S., Ho Jessica Y., Vierboom Yana, and Preston Samuel H.. 2019. “Trends in Non-Hispanic White Mortality in the United States by Metropolitan-Nonmetropolitan Status and Region, 1990– 2016.” Population and Development Review 45(3): 549–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenelon Andrew. 2013. “Revisiting the Hispanic mortality advantage in the United States: The role of smoking.” Social Science & Medicine 82: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich MJ 1999. “Hospice Care in the United States: A Conversation With Florence S. Wald.” JAMA 281(18):1683–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- General Accounting Office (GAO). 2003. Prescription drugs: OxyContin abuse and diversion and efforts to address the problem. Publication GAO-04–110. Washington, DC: General Accounting Office. [Google Scholar]

- Glei Dana A., and Preston Samuel H.. 2020. “Estimating the impact of drug use on US mortality, 1999–2016.” PLoS ONE 15(1): e0226732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield Shelly F., Back Sudie E., Lawson Katie, and Brady Kathleen T.. 2010. “Substance Abuse in Women.” Psychiatr Clin N Am 33: 339–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan Joel D., Craft Rebecca M., Linda LeResche Lars Arendt-Nielsen, et al. 2007. “Studying sex and gender differences in pain and analgesia: A consensus report.” Pain 132: S26–S45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy Gery P., Zhang Kun, Bohm Michele K., Losby Jan, et al. 2017. “Vital Signs: Changes in Opioid Prescribing in the United States, 2006–2015.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 66(26): 697–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard Holly, Miniño Arialdi M., and Margaret Warner. 2018. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2017. NCHS Data Brief, no 329. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Avila Carlos A., Rounsaville Bruce J., and Kranzler Henry R.. 2004. “Opioid-, cannabis- and alcohol-dependent women show more rapid progression to substance abuse treatment.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 74: 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg David. 2006. “‘The Pill You Love Can Turn on You’: Feminism, Tranquilizers, and the Valium Panic of the 1970s.” American Quarterly 58(1): 79–103. [Google Scholar]

- Ho Jessica Y. 2019. “The Contemporary American Drug Overdose Epidemic in International Perspective.” Population and Development Review 45(1): 7–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Jessica Y. 2017. “The Contribution of Drug Overdose to Educational Gradients in Life Expectancy in the United States, 1992–2011.” Demography 54(3): 1175–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Jessica Y., and Elo Irma T.. 2013. “The Contribution of Smoking to Black-White Differences in U.S. Mortality.” Demography 50(2): 545–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Jessica Y., and Hendi Arun S.. 2018. “Recent Trends in Life Expectancy across High Income Countries: A Retrospective Observational Study.” The BMJ. 362: k2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann DE, Tarzian AJ. 2001. “The girl who cried pain: a bias against women in the treatment of pain. J Law Med Ethics. 29(1): 13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan Howard, Perez Debbie, and Bell William R.. Who (Really) Are the First Baby Boomers?, in Joint Statistical Meetings Proceedings, Social Statistics Section, Alexandria, VA: American Statistical Association; 2008. pp. 1009–1016 [Google Scholar]

- Holford Theodore R., Levy David T., and Meza Rafael. 2016. “Comparison of Smoking History Patterns Among African American and White Cohorts in the United States Born 1890 to 1990.” Nicotine & Tobacco Research 18(suppl 1): S16–S29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2011. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs Harrison. 2016. “Pain Doctors: Insurance Companies Won’t Cover the Alternatives to Opioids.” Business Insider, August 10, 2016. http://www.businessinsider.com/doctors-insurancecompanies-policies-opioid-use-2016-6. [Google Scholar]

- Jamison Robert N., Butler Stephen F., Budman Simon H., Edwards Robert R., and Wasan Ajay D.. 2010. “Gender Differences in Risk Factors for Aberrant Prescription Opioid Use.” The Journal of Pain 11(4): 312–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janakiram Chandrashekar, Chalmers Natalia I., Fontelo Paul, Huser Vojtech, Gabriela Lopez Mitnik Timothy J. Iafolla, Brow Avery R., and Dye Bruce A.. 2019. “Sex and race or ethnicity disparities in opioid prescriptions for dental diagnoses among patients receiving Medicaid.” JADA 150(10): e135–e144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones Christopher M., Einstein Emily B., and Compton Wilson M.. 2018. “Changes in Synthetic Opioid Involvement in Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 2010–2016.” JAMA 319(17): 1819–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandall Stephen R. 1999. Substance and Shadow: Women and Addiction in the United States. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes Katherine M., Grant Bridget F., and Hasin Deborah S.. 2008. “Evidence for a closing gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 93: 21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koumjian Kevin. 1981. “The use of Valium as a form of social control.” Social Science & Medicine 15E: 245–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo Yong-Fang, Raji Mukaila A., Chen Nai-Wei, Hasan Hunaid, and Goodwin James S.. 2016. “Trends in Opioid Prescriptions Among Part D Medicare Recipients From 2007 to 2012.” The American Journal of Medicine 129: 221.e21–221.e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack Karin A., Jones Christopher M., and Paulozzi Leonard J.. 2013. “Vital Signs: Overdoses of Prescription Opioid Pain Relievers and Other Drugs Among Women — United States, 1999–2010.” Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report 62(26): 537–542. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macy Beth. 2018. Dopesick. New York: Hachette Book Group. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall Brandon D.L., Fairbairn Nadia, Kathy Li, Wood Evan, and Thomas Kerr. 2008. “Physical violence among a prospective cohort of injection drug users: A gender-focused approach.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 97: 237–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazure Caroyln M. and Fiellin David A. 2018. “Women and opioids: something different is happening here.” The Lancet 392(10141): 9–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh R Kathryn Elise E. DeVito Dorian Dodd, Carroll Kathleen M., et al. 2013. “Gender differences in a clinical trial for prescription opioid dependence.” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 45: 38–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier Barry. 2003. Pain Killer: A “Wonder” Drug’s Trail of Addiction and Death. New York: Rodale, St. Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mezei Lina, Murinson Beth B., and the Johns Hopkins Pain Curriculum Development Team. 2011. “Pain education in North American medical schools.” Journal of Pain 12(12): 1199–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edward Miller, G. Asako S.. 2018. Any Use and Frequent Use of Opioids among Non-Elderly Adults in 2015–2016, by Socioeconomic Characteristics September 2018. Statistical Brief #516. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD: https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st516/stat516.pdf 3. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Mortality - State Only (2005+) and Mortality - All County (micro-data) files (1989–2015), as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. [Google Scholar]

- Oeppen Jim, and Vaupel James W.. 2002. “Broken Limits to Life Expectancy.” Science 296(5570): 1029–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksuzyan Anna, Juel Knud, Vaupel James W., and Christensen Kaare. “Men: good health and high mortality. Sex differences in health and aging.” Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 20(2): 91–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson Mark, King Marissa, and Schoenbaum Michael. 2015. “Benzodiazepine use in the United States.” JAMA Psychiatry 72(2): 136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palanker Dania. 2008. “Enslaved by Pain: How the U.S. Public Health System Adds to Disparities in Pain Treatment for African Americans.” Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law & Policy 15(3): 847–878 [Google Scholar]

- Pampel Fred C. 2001. “Cigarette Diffusion and Sex Differences in Smoking.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 42(4): 388–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulozzi Leonard J., Budnitz Daniel S., and Xi Yongli. 2006. “Increasing deaths from opioid analgesics in the United States.” Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 15: 618–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulozzi Leonard J., Jones Christopher M., Mack Karin A., and Rudd Rose A.. 2011. Overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999–2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 60: 1487–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulozzi Leonard J., and Xi Yongli. 2008. “Recent changes in drug poisoning mortality in the United States by urban– rural status and by drug type.” Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 17: 997–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry Nancy M., and Bickel Warren K.. 2000. “Gender differences in hostility of opioid-dependent outpatients: role in early treatment termination.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 58: 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletcher Mark J., Kertesz Stefan G., Kohn Michael A., and Gonzales Ralph. 2008. “Trends in Opioid Prescribing by Race/Ethnicity for Patients Seeking Care in US Emergency Departments.” JAMA 299(1): 70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston Samuel H., Heuveline Patrick, and Guillot Michel. 2001. Demography: Measuring and modeling population processes. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Preston Samuel H., and Wang Haidong. 2006. “Sex Mortality Differences in the United States: The Role of Cohort Smoking Patterns.” Demography 43(4):631–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinones Sam. 2015. Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic. New York: Bloomsbury Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rigg Khary K., Monnat Shannon M., and Chavez Melody N.. 2018. “Opioid-related mortality in rural America: Geographic heterogeneity and intervention strategies.” International Journal of Drug Policy 57: 119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni-Wastila Linda. 2000. “The Use of Abusable Prescription Drugs: The Role of Gender.” Journal of Women’s Health and Gender-Based Medicine 9(3): 289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni-Wastila Linda, Ritter Grant, and Strickler Gail. 2004. “Gender and Other Factors Associated with the Nonmedical Use of Abusable Prescription Drugs.” Substance Use & Misuse 39(1): 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal Astha, Tien Yu-Yu, and Hsia Renee Y.. 2016. “Racial- Ethnic Disparities in Opioid Prescriptions at Emergency Department Visits for Conditions Commonly Associated with Prescription Drug Abuse.” PLoS ONE 11(8): e0159224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner Allan, Mercado-Crespo Melissa C., Spelke M. Bridget, Paulozzi Leonard, et al. 2016. “Use of Naloxone by Emergency Medical Services during Opioid Drug Overdose Resuscitation Efforts.” Prehospital Emergency Care 20(2): 220–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER). Standard populations - 19 age groups. https://seer.cancer.gov/stdpopulations/stdpop.19ages.html.

- Tamayo-Sarver Joshua H., Hinze Susan W., Cydulka Rita K., and Baker David W.. 2003. “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Emergency Department Analgesic Prescription.” American Journal of Public Health 93: 2067–2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrell Kevin M., Hui Siu L., Peter Castelluccio, Kroenke Kurt, McGrath Roland B., and Miller Douglas K.. 2010. “Analgesic Prescribing for Patients Who Are Discharged from an Emergency Department.” Pain Medicine 11: 1072–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas Katie, and Ornstein Charles. 2017. “Amid Opioid Crisis, Insurers Restrict Pricey, Less Addictive Painkillers.” New York Times, September 17, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/17/health/opioid-painkillers-insurance-companies.html. [Google Scholar]

- Tobin Karin E., Davey Melissa A., and Latkin Carl A.. 2005. “Calling emergency medical services during drug overdose: an examination of individual, social and setting correlates.” Addiction 100: 397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner Cathy, and Rod McClure. 2003. “Age and gender differences in risk-taking behaviour as an explanation for high incidence of motor vehicle crashes as a driver in young males.” Injury Control and Safety Promotion 10(3): 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2016. Health Insurance Historical Tables - Original Series: Table HI-1. Health Insurance Coverage Status and Type of Coverage--All Persons by Sex, Race and Hispanic Origin: 1987 to 2005. Available online at: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/health-insurance/historical-series/original.html. [Google Scholar]

- “Tackling Fentanyl: The China Connection.” Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights and International Organizations of Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives. September 6, 2018. Washington: U.S: Government Publishing Office; https://docs.house.gov/meetings/FA/FA16/20180906/108650/HHRG-115-FA16-Transcript-20180906.pdf [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). 2017. Final Report: Opioid Use, Misuse, and Overdose in Women. Available online at: https://www.womenshealth.gov/files/documents/final-report-opioid-508.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2018). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2015 (NSDUH-2015-DS0001). Retrieved from https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2018). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2016 (NSDUH-2016-DS0001). Retrieved from https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2018). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2017 (NSDUH-2017-DS0001). Retrieved from https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee. 2018. Fueling an Epidemic: Exposing the Financial Ties Between Opioid Manufacturers and Third Party Advocacy Groups (Report Two). Available online at: https://www.hsgac.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/REPORT-Fueling%20an%20Epidemic-Exposing%20the%20Financial%20Ties%20Between%20Opioid%20Manufacturers%20and%20Third%20Party%20Advocacy%20Groups.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Zee Van, Art. 2009. “The Promotion and Marketing of OxyContin: Commercial Triumph, Public Health Tragedy.” American Journal of Public Health 99(2): 221–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron Ingrid. 1993. “Recent Trends in Sex Mortality Ratios for Adults in Developed Countries.” Social Science and Medicine 36: 451–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron Ingrid, Christopher McCloskey, and Inga Earle. 2005. “Trends in gender differences in accidents mortality: Relationships to changing gender roles and other societal trends.” Demographic Research 13: 415–454. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.