Abstract

Background

The clinical impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) among people with HIV (PWH) remains unclear. In this retrospective cohort study of COVID-19, we compared clinical outcomes and laboratory parameters among PWH and controls.

Methods

Sixty-eight PWH diagnosed with COVID-19 were matched 1:4 to patients without known HIV diagnosis, drawn from a study population of all patients who were diagnosed with COVID-19 at an academic urban hospital. The primary outcome was death/discharge to hospice within 30 days of hospital presentation.

Results

PWH were more likely to be admitted from the emergency department than patients without HIV (91% vs 71%; P = .001). We observed no statistically significant difference between admitted PWH and patients without HIV in terms of 30-day mortality rate (19% vs 13%, respectively) or mechanical ventilation rate (18% vs 20%, respectively). PWH had higher erythrocyte sedimentation rates than controls on admission but did not differ in other inflammatory marker levels or nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 viral load estimated by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction cycle thresholds.

Conclusions

HIV infection status was associated with a higher admission rate; however, among hospitalized patients, PWH did not differ from HIV-uninfected controls by rate of mechanical ventilation or death/discharge to hospice.

Keywords: COVID-19, HIV-1, SARS-CoV-2

The global severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic has led to >54 million cases and 1.3 million deaths worldwide [1]. The clinical manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) range from asymptomatic disease to acute respiratory disease syndrome with shock and multiorgan failure [2, 3]. There is ongoing uncertainty about whether HIV infection or degree of HIV-related immune deficiency contributes to severity of COVID-19 and COVID-19-related outcomes.

A large cohort study from South Africa recently found that PWH had a 2-fold increased risk of COVID-19 mortality compared with HIV-uninfected people [4]. It has been shown that PWH with CD4 counts <200 cells/mm3 may be at higher risk for severe outcomes compared with PWH with CD4 counts >500 cells/mm3 [5]. Other studies have shown that COVID-19 outcomes do not significantly differ by HIV infection status [6–8]. Indeed, the World Health Organization recognizes that there is currently no evidence to suggest that PWH are at higher risk for contracting SARS-CoV-2 or severe COVID-19 [9]. Some have even postulated that HIV might exert a protective effect against SARS-CoV-2 by diminishing the inflammatory response due to dysfunctional cellular immunity or the antiviral effects of co-incidental use of specific HIV antiretrovirals [10, 11]. We sought to describe the COVID-19 clinical experience and laboratory characteristics of PWH and to evaluate the association between HIV infection status and death/discharge to hospice and other clinical outcomes.

METHODS

Study Population and Design

Between March 10, 2020, and June 10, 2020, there were 6098 patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection at Columbia University-New York Presbyterian, a quaternary care medical center in Northern Manhattan. From this sample, we conducted a retrospective cohort analysis to evaluate the association between HIV infection status and several clinical outcomes: admission, mechanical ventilation, and death/discharge to hospice within 30 days of hospital admission. We identified all adult patients (≥18 years old) with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swabs. We identified PWH cases (n = 68) and selected matched controls at a ratio of 1 to 4 (n = 272). HIV cases were defined based on HIV diagnostic codes or administration of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in the electronic medical record (EMR). HIV status was confirmed through manual chart review indicating laboratory evidence of HIV or provider documentation of HIV status. Controls were selected from the same COVID-19 population and had no documented HIV status in any of the same EMR data sources used to confirm HIV infection. Controls were matched by age group (<45 years of age, then 10-year bands, and 85 years and above), sex, and the number of days before presentation that the patient was symptomatic (±1 day).

Data Collection

The data were extracted from the EMR and augmented with manually abstracted data. Electronically extracted data included demographics, oxygen rank severity upon arrival (room air, nasal canula, non-rebreather, noninvasive ventilation, invasive ventilation), basic laboratory testing results (ie, complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, coagulation panel), other laboratory parameters per institutional guidelines for management of COVID-19 (ie, erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], C-reactive protein [CRP], lactate dehydrogenase [LDH], ferritin, D-dimer, procalcitonin, and interleukin-6 [IL-6]), presentation, admission and discharge dates, diagnosis codes for comorbid conditions, and potential therapeutic agents for COVID-19. Of note, our institutional protocol for the care of patients with COVID-19 recommended immediate measurement of the above laboratory markers; thus, the values reflect measurements drawn from patients while they were in the emergency department. Additional data abstracted for PWH included a history of AIDS (CD4 ˂200 cells/mm3), prescribed ART during admission, HIV viral load (VL), T-cell panel, and any opportunistic infections diagnosed during the admission. These data were entered into a REDCap database. All data were merged using R studio [12].

Statistical Analysis

We conducted descriptive analyses comparing PWH cases and matched controls. Continuous variables were described using means and standard deviations. Categorical variables were described with counts and percentages. In bivariate analyses, categorical variables were compared using the Wald chi-square test or Fisher exact test, and continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test or Kruskal-Wallis test as appropriate and visualized in box and whisker plots. Group differences at admission were evaluated with the categorical and continuous variable tests described. The likelihood of admission was calculated using multiple logistic regression adjusting for ethnicity, race, history of hypertension, and history of pulmonary disease. For the effect of HIV status on the risk of requiring mechanical ventilation, we conducted a conditional Cox proportional hazards model using the Fine-Gray extension comparing those who required mechanical ventilation with admitted patients who did not. For the risk of death/discharge to hospice within 30 days of presentation, we conducted a conditional Cox proportional hazards model with and without discharge within 30 days as a competing risk. Patients were observed for mechanical ventilation or death/discharge to hospice as the primary outcomes, with discharge as a competing risk, or were censored at day 30 after admission if neither of the primary or competing events occurred. The HIV-specific hazard for death/discharge to hospice/mechanical ventilation at any time point, t, is the instantaneous risk of death/discharge to hospice/mechanical ventilation as the first event, conditional on being admitted just before t. Individuals who were discharged first were censored at this time when considering each primary outcome in the hazard analysis. All regression models were fit with all variables that were significantly different by HIV status based on logistic regression analysis and Wald test, or exclusion of the null for 95% confidence intervals. All statistical analyses and data visualization were performed in SAS STAT software, version 13.2 (Cary, NC, USA).

Patient Consent Statement

This study was exempt from patient consent, and the Columbia University-New York Presbyterian Institutional Review Board approved the study.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

There were 68 PWH and 272 matched controls with positive test results for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR of nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swab evaluated during the study period. The overall sample (n = 340) had a mean age (SD) of 58 (12.7) years and was disproportionately male (71%, n = 240) (Table 1). There was no difference in age or sex due to the matching criteria, but PWH were more likely to be non-Hispanic Black (41% vs 20%) and less likely to be Hispanic (21% vs 43%; P = .0004). The 3 most common comorbidities among PWH were hypertension (63%), diabetes (37%), and pulmonary disease (26%). PWH had lower body mass index (BMI; 26.9 vs 28.8; P = .02) but were more likely to have a history of hypertension (63% vs 43%; P = .003) and pulmonary disease (26% vs 15%; P = .03). Compared with matched controls, PWH had lower initial alanine aminotransferase levels (31.1 U/L vs 49.1 U/L; P = .02), a lower initial neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR; 5.39 vs 6.99; P = .01), and higher ESR levels (77.9 mm/h vs 65.8 mm/h; P = .02) (Table 1). There were no differences in oxygen rank severity upon arrival to the emergency department by HIV status (3/68 PWH and 74/272 controls had missing data). Among admitted patients, there were no differences in the use of potential COVID-19 therapeutics between PWH and HIV-negative controls.

Table 1.

Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2-Positive Patients by HIV Status

| Overall (n = 340), No. (%) | HIV+ (n = 68), No. (%) | HIV- (n = 272), No. (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 58.4 ± 12.7 | 59.0 ± 13.1 | 58.2 ± 12.6 | .61 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 240 (71) | 48 (71) | 192 (71) | 1.00 |

| Female | 100 (29) | 20 (29) | 80 (29) | |

| Racial ethnic identity | .0004 | |||

| Hispanic | 130 (38) | 14 (21) | 116 (43) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 82 (24) | 28 (41) | 54 (20) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 45 (13) | 7 (10) | 38 (14) | |

| Other/not specified | 83 (24) | 19 (28) | 64 (24) | |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Admitted to hospital | 256 (75) | 62 (91) | 194 (71) | .001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 66 (19) | 12 (18) | 54 (20) | .68 |

| Death or discharge to hospice | 48 (14) | 13 (19) | 35 (13) | .19 |

| Comorbidities and clinical parameters | ||||

| Diabetes | 105 (31) | 25 (37) | 80 (29) | .24 |

| Hypertension | 161 (47) | 43 (63) | 118 (43) | .003 |

| Kidney disease | 33 (10) | 8 (12) | 25 (9) | .52 |

| Pulmonary | 59 (17) | 18 (26) | 41 (15) | .03 |

| Initial temperature, mean ± SD, °F | 99.45 ± 1.56 | 99.2 ± 1.5 | 99.5 ± 1.6 | .13 |

| Oxygen rank severity upon arrival to emergency department | .56 | |||

| No support | 168 (64) | 41 (63) | 127 (64) | |

| Nasal canula | 60 (23) | 18 (28) | 42 (21) | |

| Non-rebreather | 28 (10) | 6 (9) | 22 (11) | |

| Noninvasive ventilation | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Invasive ventilation | 6 (2) | 0 (0) | 6 (3) | |

| BMI, mean ± SD, kg/m2 | 28.42 ± 5.90 | 26.9 ± 6.0 | 28.8 ± 5.8 | .02 |

| 30.1–40.0 kg/m2 | 84 (25) | 15 (22) | 69 (25) | |

| >40.1 kg/m2 | 11 (3) | 1 (1) | 10 (4) | |

| COVID-19 treatment | ||||

| Hydroxychloroquine | 141 (57) | 31 (52) | 110 (59) | .35 |

| Remdesivir | 6 (2) | 2 (3) | 4 (2) | .59 |

| Tociluzmab | 11 (4) | 3 (5) | 8 (4) | .8 |

| Methylprednisolone | 39 (16) | 12 (20) | 27 (14) | .30 |

| Laboratory parameters, mean ± SD (%) | ||||

| WBC count, ×103/mm3 | 7.96 ± 4.73 (80) | 7.6 ± 4.7 (99) | 8.1 ± 4.7 (76) | .45 |

| Platelet count, ×103/mm3 | 210.1 ± 98.2 (80) | 214.6 ± 95.5 (99) | 208.7 ± 99.3 (76) | .67 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.74 ± 2.34 (81) | 2.06 ± 3.01 (99) | 1.64 ± 2.08 (76) | .20 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.79 ± 0.60 (79) | 3.89 ± 0.63 (97) | 3.76 ± 0.58 (75) | .15 |

| AST, U/L | 64.9 ± 137.1 (79) | 50.7 ± 33.3 (97) | 69.5 ± 156.4 (75) | .33 |

| ALT, U/L | 44.70 ± 53.95 (79) | 31.1 ± 22.3 (97) | 49.1 ± 60.2 (75) | .02 |

| LDH, U/L | 460 ± 247 (71) | 464 ± 250 (88) | 459 ± 246 (67) | .90 |

| D-dimer, µg/mL | 8.65 ± 79.50 (62) | 3.16 ± 4.35 (74) | 10.36 ± 91.04 (59) | .58 |

| Inflammatory markers, mean ± SD (%) | ||||

| ESR, mm/h | 68.6 ± 33.4 (67) | 77.9 ± 35.5 (79) | 65.8 ± 32.3 (64) | .02 |

| CRP, mg/L | 126 ± 92 (71) | 120 ± 92 (88) | 129 ± 93 (67) | .51 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 1250 ± 2085 (71) | 1361 ± 3617 (84) | 1215 ± 1301 (68) | .65 |

| IL-6, pg/mL | 79.8 ± 96.5 (60) | 47.5 ± 89.9 (66) | 34.1 ± 55.8 (59) | .22 |

| NLR | 6.60 ± 5.93 (75) | 5.39 ± 6.51 (93) | 6.99 ± 5.68 (71) | .01 |

| Procalcitonin, ng/mL | 3.51 ± 27.75 (71) | 0.61 ± 1.04 (85) | 4.43 ± 31.8 (67) | .36 |

| Nasopharyngeal swab RT-PCR, mean ± SD | ||||

| Cycle threshold (E gene) | 26.18 ± 6.4 | 28.1 ± 6.4 | 25.7 ± 6.3 | .14 |

| HIV parameters | ||||

| Opportunistic infection | 3 (4) | N/A | ||

| Prior AIDS diagnosis (CD4 ˂200 cells/mm3) | — | 18 (27) | — | |

| CD4 cells/mm3 absolute and percentage upon admission, mean ± SD | — | 324 ± 228 (26.5 ± 12.5) | — | |

| CD4 cell count >200 cells/mm3 | — | 29 (69) | — | |

| <200 cells/mm3 | — | 13 (31) | — | |

| 200–500 cells/mm3 | — | 22 (52) | — | |

| >500 cells/mm3 | — | 7 (17) | — | |

| CD4 percentage ≥14 | — | 35 (83) | — | |

| HIV RNA <200 copies/mL | — | 32 (89) | — | |

| Current ARV (not mutually exclusive) | — | 67 (99) | — | |

| INSTI-based | — | 51 (76) | — | |

| PI-based | — | 15 (22) | — | |

| NNRTI-based | — | 9 (13) | — | |

| TDF/TAF-containing | — | 39 (58) | — |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ARV, antiretroviral; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; IL-6, interleukin-6; INSTI, integrase strand transfer inhibitor; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory disease coronavirus 2; TAF, tenofovir alafenamide; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; WBC, white blood cell.

Hospital Admission

PWH were more likely to be admitted to the hospital (91% vs 71%; P = .001) than patients without HIV (Table 1). The unadjusted odds ratio for admission among PWH was 5.2 (95% CI, 1.9–14.3) (Table 2). After adjusting for potential confounding variables, only HIV and history of hypertension were predictive of hospitalization. PWH remained 4.1 times more likely to be admitted than HIV-negative controls (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 4.1; 95% CI, 1.4–12.4), and patients with a history of hypertension were 4.8 times more likely to be admitted (aHR, 4.8; 95% CI, 1.8–13.3).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Logistic Regression of HIV Status on Admission From the Emergency Department and Conditional Cox Proportional Hazards Regression of HIV Status on Mechanical Ventilation and Death/Discharge to Hospice

| Conditional Logistic Regression for Admission | Cox Proportional Hazards for Mechanical Ventilation | Cox Proportional Hazards Death/Discharge to Hospice | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | ORunadj (95% CI) | HRadj (95% CI) | HRunadj (95% CI) | HRadj (95% CI) | HRunadj (95% CI) | HRadj (95% CI) |

| HIV | 5.2 (1.9–14.3) | 4.1 (1.4–12.4) | 0.8 (0.5–1.6) | 0.7 (0.4–1.5) | 1.4 (0.7–2.8) | 0.9 (0.3–2.3) |

| Racial and ethnic identity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.4 (0.1–1.4) | 0.9 (0.3–2.7) | 0.5 (0.2–1.9) | |||

| Hispanic | 1.5 (0.5–4.9) | 1.1 (0.5–2.9) | 0.4 (0.1–1.2) | |||

| Other/not specified | 2.6 (0.5–4.9) | 0.9 (0.3–2.4) | 0.6 (0.2–1.7) | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| BMI (kg/m2 every 5-unit increase; Ref.) | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | |||

| Hypertension | ||||||

| Yes | 4.8 (1.8–13.3) | 1.4 (0.8–2.3) | 1.5 (0.6–3.4) | |||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | ||||

| ALT | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) | ||||

| ESR | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) | ||||

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HR, hazard ratio.

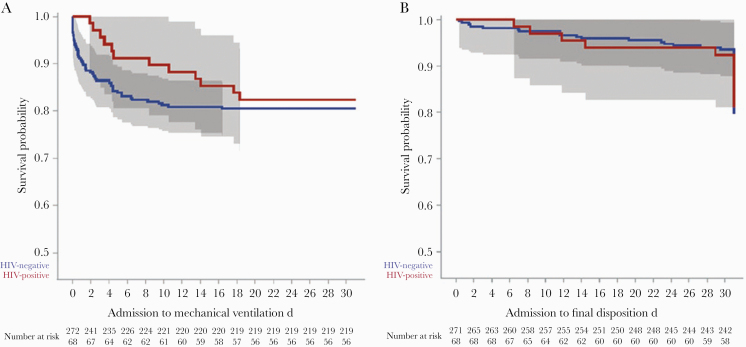

Mechanical Ventilation

There was no significant difference in the rate of mechanical ventilation among PWH and their matched controls (18% vs 20%; P = .68) (Table 1), with an unadjusted hazard ratio of 0.8 (95% CI, 0.5–1.6) (Table 2). The competing risk model was not applied to mechanical ventilation, as this always preceded discharge. After adjustment for potential confounding factors, there was still no difference in the rate of mechanical ventilation by HIV status (aHR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.4–1.5). Variables associated with a higher rate of mechanical ventilation were BMI (aHR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.0–1.4) and NLR (aHR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.2–1.8). A Kaplan-Meier curve representing time to mechanical ventilation by HIV status group is presented in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves of (A) time to requiring mechanical ventilation and (B) time to death/discharge within 30 days of presentation between HIV-positive cases and matched controls.

Death/Discharge to Hospice

There was also no difference in the rate of death/discharge to hospice between PWH and matched controls (19% vs 13%; P = .19) (Table 1), with an unadjusted hazard ratio of 1.4 (95% CI, 0.7–2.8) (Table 2). Among admitted-only patients, the rate of death/discharge to hospice among PWH and matched controls was 21% and 18%, respectively. After statistical adjustment, PWH had an aHR of 0.9 for death/discharge to hospice (95% CI, 0.3–2.3). Variables associated with a higher rate of death/discharge to hospice were BMI (aHR, 1.1; 95% CI, 1.0–1.1) and NLR (aHR, 1.1; 95% CI, 1.0–1.1). Although the number of discharges as a competing risk was high, this was not different by HIV status; therefore, the Kaplan-Meier curve representing time to death/discharge to hospice by HIV status group is presented in Figure 1B. Additionally, cumulative incidence curves shown in Supplementary Figure 1 support this observation.

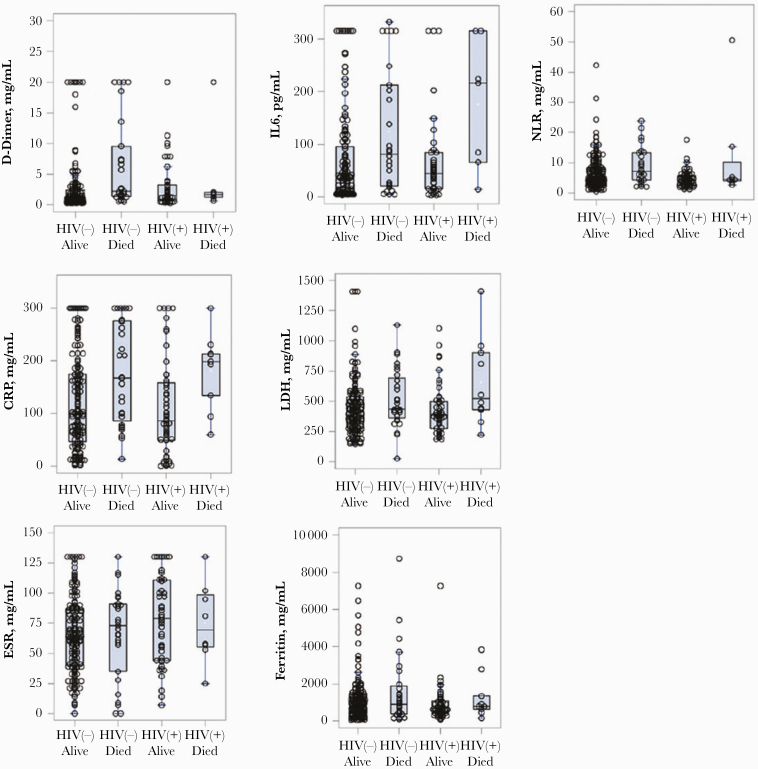

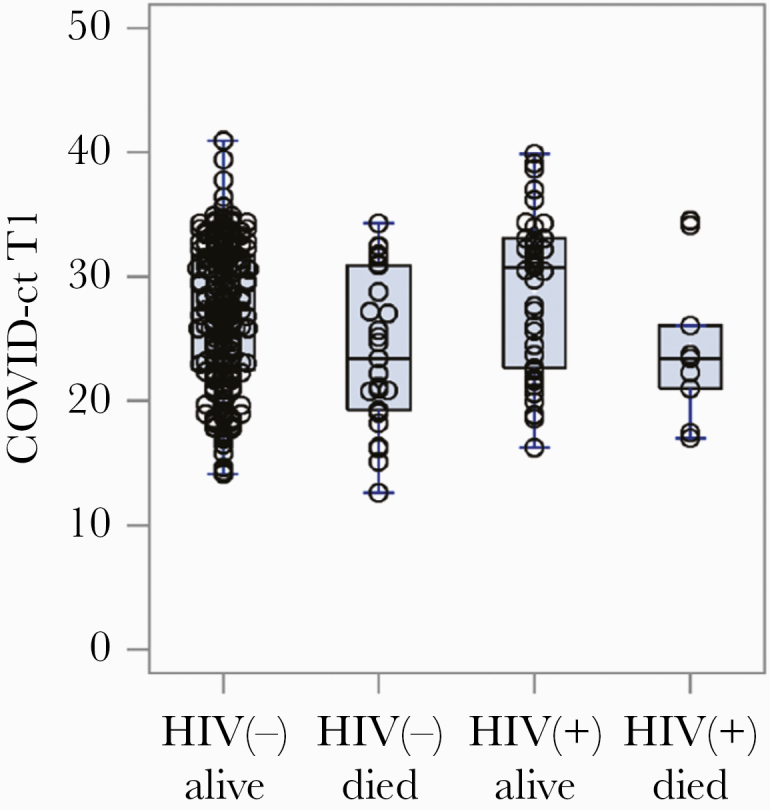

Laboratory Markers

We found no differences in initial inflammatory markers when stratified by HIV infection and mortality status (Figure 2). We also compared laboratory markers over time in PWH compared with negative controls and found no difference (data not shown). There was no significant difference by HIV status in nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR cycle threshold values (E-gene for both Roche cobas SARS-CoC-2 or Cepheid Xpert Xpress) (Table 1). Additionally, there was no difference in cycle threshold value when stratified by HIV infection and mortality status (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Initial values of inflammatory markers stratified by HIV status and clinical outcome. Abbreviations: CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; IL-6, interleukin-6; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio.

Figure 3.

Initial cycle threshold values of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 nasopharyngeal reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction for E-gene targets (Roche or Cepheid) stratified by HIV status and clinical outcome. Abbreviation: COVID, coronavirus disease.

Among PWH

Among PWH, there was no association between CD4 cell count on admission, CD4 cell percentage on admission, and use of TDF/TAF with rates of mechanical ventilation. There was also no association between CD4 percentage on admission and use of TDF/TAF with death/discharge to hospice, but PWH with the outcome of death/discharge to hospice had a lower mean CD4 count on admission (206 cells/mm3 vs 366 cells/mm3; P = .04). Of the 36 PWH with VL measurements during admission for COVID-19, one-fourth (25%) of those with a VL >200 cells/mL required mechanical ventilation vs 9/32 (28%) patients with a VL <200 cells/mL (P = 1.00). Similarly, 2/4 (50%) and 6/32 (19%) PWH with a VL above and below 200 cells/mL, respectively, met the outcome of death/discharge to hospice (P = .38). There were few (4%, n = 3) opportunistic infections diagnosed in PWH. The 3 opportunistic infections in our study were coinfections at the time of COVID-19 diagnosis; they included 2 PWH with oral thrush and 1 PWH with disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex, and they all occurred in patients nonadherent to ART. During the study period, there were 144 PWH either discharged from our emergency department or admitted to our hospital who had negative test results for SARS-CoV-2 who were not included in this study. Their mean age (SD) was 51 (12.9) years, most identified as non-Hispanic and Black, and more than half (51%) had a history of AIDS. Most (86%) of the HIV-positive, SARS-CoV-2-negative patients were prescribed ART, and most (70%) were on an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI)–based regimen.

HIV-Specific Markers

Nearly all PWH were prescribed ART during their admission for COVID-19, most (76%) received an INSTI-based regimen, and more than half received either TDF or TAF (Table 1). Although 18 patients (27%) had a history of AIDS, of the patients with measurements upon admission for COVID-19, the mean CD4 count was 324 cells/mm3, 29/42 (69%) had a CD4 count >200 cells/mm3, and 35/42 (83%) had a CD4 percentage ≥14. Of the 36 patients with VL measurements during admission, most (89%) achieved viral suppression.

DISCUSSION

Our institution is a quaternary care medical center in New York City and was an epicenter of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic during the study period. We found that PWH were more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19, but once admitted, they had similar rates of mechanical ventilation and death/discharge to hospice compared with demographically matched controls. Higher BMI and higher NLR remained significant predictors of mechanical ventilation and death/discharge to hospice overall. PWH and HIV-negative controls did not differ in their exposure to potential COVID-19 therapeutics.

The higher admission rate among PWH was surprising, as in our sample PWH were similar in age, comorbidity profile, temperature, duration of symptoms, and laboratory measures as their HIV-uninfected comparators. Notably, there was also no difference in oxygen rank severity upon arrival to the emergency department by HIV status. Emergency room providers’ perceptions surrounding HIV and historical biases toward admission of HIV-positive patients may have contributed to the difference we observed, as PWH are more likely to be admitted from emergency departments than HIV-negative patients [13]. Providers’ anxiety that HIV status may confer poor outcomes from COVID-19 may have also contributed to the higher admission rates among PWH.

The lack of an association between HIV infection status and mechanical ventilation and death/discharge to hospice has been reported by others [14]. It is notable that studies from across Europe and the United States have shown that the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19 in PWH is not due to immunosuppression, but rather mostly due to underlying socioeconomic conditions and comorbidities [7, 8, 15–21]. The 1 notable exception was a population-based study from South Africa that found that PWH had a 2-fold increased risk of COVID-19 mortality compared with HIV-uninfected people [4]. Residual confounding may explain this finding in this cohort, which tried to account for socioeconomic status by adjusting for location within the province but may not have been able to completely adjust for this complex variable.

The comorbidities of hypertension, pulmonary disease, and obesity are widely recognized risk factors for severe disease from COVID-19. We found a consistent association between higher BMI and increased rates of mechanical ventilation or death/discharge to hospice in our adjusted model. This finding is consistent with other studies, which also found that elevated BMI is a risk factor for poor outcomes from COVID-19 [22, 23]. Similarly, elevated inflammatory markers and nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 viral loads have been demonstrated to be predictors of poor outcomes from COVID-19 [24, 25]. D-dimer elevation upon admission has been shown to be predictive of critical illness and death in patients with COVID-19, and we found no difference in d-dimer levels between PWH and controls [26]. We explored whether initial levels of all tested inflammatory markers or nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 viral loads differed by HIV status and mortality, but found no differences. However, in adjusted models, we found that NLR was associated with rates of mechanical ventilation and death/discharge to hospice. NLR has been shown to be predictive of severe COVID-19 requiring transfer to an intensive care unit [27]. The biological mechanism underlying this association remains unknown, but a possible explanation is that a sustained reduction in lymphopenia in critically ill patients is associated with nonresolution of inflammation [28].

In vitro studies suggest that some forms of ART, especially protease inhibitors (PIs) and TDF/TAF, may have activity against SARS-CoV-2 with the following mechanisms: PIs via inhibition of proteases required for polyprotein cleavage into functional subunits and TDF/TAF via inhibition of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase [29–31]. Despite promising in vitro data, randomized clinical trials in humans with PIs for SARS-CoV-2 infection have been negative [32, 33]. In our study sample, we found that PWH who received TDF/TAF did not differ in risk of mechanical ventilation or death/discharge to hospice.

The strengths of our study include a moderately sized study population with a matched comparison group during the heart of the pandemic in New York City. Limitations include the study being conducted at a single center at a large metropolitan city in the United States, our reliance on manual extraction from the EMR for medical history, insufficient data to match by race/ethnicity or date of diagnosis, and our use of diagnosis codes to identify PWH.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we found that PWH were more likely to be admitted from the emergency department, but once hospitalized they had similar rates of mechanical ventilation and death/discharge to hospice as matched controls.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Financial support. For the research reported in this publication, J.L. was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32AI114398.

Disclaimer. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors have no reported conflicts of interest. All authors are familiar with and abide by the standards set by the ICMJE Conflict of Interest form. All authors: no reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Author contributions. Zucker J, Castor D, McMahon D, and Yin M participated in study design and conception; Laracy J and Guo TW performed manual extraction of patient data from the electronic medical record; Zucker J, Castor D, McMahon D, Laracy J, and Yin M interpreted data results. All authors contributed to and approved the final draft for publication. Yin M was the principal investigator of the study.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019?gclid=Cj0KCQjwrIf3BRD1ARIsAMuugNsOgasTzfhTZp-LENqd4pLWr_6TA-lxPJjQr54oOVg5MrMhOG3FCNMaAuS8EALw_wcB. Accessed 10 June 2020.

- 2. Hu Z, Song C, Xu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 24 asymptomatic infections with COVID-19 screened among close contacts in Nanjing, China. Sci China Life Sci 2020; 63:706–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395:1054–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boulle A, Davies M-A, Hussey H, et al. Risk factors for COVID-19 death in a population cohort study from the Western Cape Province, South Africa. Clin Infect Dis . 2020; 14:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dandachi D, Geiger G, Montgomery MW, et al. Characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes in a multicenter registry of patients with HIV and coronavirus disease-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sigel K, Swartz T, Golden E, et al. Covid-19 and people with HIV infection: outcomes for hospitalized patients in New York City. Clin Infect Dis. 2020; 71:2933–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vizcarra P, Pérez-Elías MJ, Quereda C, et al. Description of COVID-19 in HIV-infected individuals: a single-centre, prospective cohort. Lancet HIV 2020; 7:e554–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Karmen-Tuohy S, Carlucci PM, Zacharioudakis IM, et al. Outcomes among HIV-positive patients hospitalized with COVID-19. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2020; 85:6–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.World Health Organization. Information note on HIV and COVID-19. 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/hiv-aids. Accessed 14 September 2020.

- 10. del Amo J, Polo R, Moreno S, et al. Incidence and severity of COVID-19 in HIV-positive persons receiving antiretroviral therapy. Ann Int Med. 2020; 173:536–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Laurence J Why aren’t people living with HIV at higher risk for developing severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)? AIDS Patient Care STDS 2020; 34:247–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. RStudio. Open source & professional software for data science teams—RStudio. Available at: https://rstudio.com/. Accessed 17 August 2020.

- 13. Mohareb A, Rothman R, Hsieh Y-H. Emergency department (ED) utilization by HIV-infected ED patients in the United States in 2009 and 2010—a national estimation. HIV Med 2013; 14:605–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stoeckle K, Johnston CD, Jannat-Khah DP, et al. COVID-19 in hospitalized adults with HIV. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020; 7:XXX–XX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blanco JL, Ambrosioni J, Garcia F, et al. ; COVID-19 in HIV Investigators COVID-19 in patients with HIV: clinical case series. Lancet HIV 2020; 7:e314–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gervasoni C, Meraviglia P, Riva A, et al.. Clinical features and outcomes of patients with human immunodeficiency virus with COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020; 71:2276–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Childs K, Post FA, Norcross C, et al. Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and human immunodeficiency virus: a case series. Clin Infect Dis. 2020; 71:2021–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Collins LF, Moran CA, Oliver NT, et al. Clinical characteristics, comorbidities and outcomes among persons with HIV hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 in Atlanta, GA. AIDS 2020; 34:1789–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Byrd KM, Beckwith CG, Garland JM, et al. SARS-CoV-2 and HIV coinfection: clinical experience from Rhode Island, United States. J Int AIDS Soc 2020; 23:e25573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Meyerowitz EA, Kim AY, Ard KL, et al. Disproportionate burden of COVID-19 among racial minorities and those in congregate settings among a large cohort of people with HIV. AIDS. 2020; 34:1781–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carlos del Rio M COVID-19 in persons living with HIV—what do we know today? NEJM J Watch. 2020. doi: 10.1056/NEJM-JW.NA52137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Petrilli CM, Jones SA, Yang J, et al. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2020; 369:m1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 2020; 584:430–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, et al. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med 2020; 46:846–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Magleby R, Westblade L, Trzebucki A, et al. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 viral load on risk of intubation and mortality among hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Al-Samkari H, Karp Leaf RS, Dzik WH, et al. COVID-19 and coagulation: bleeding and thrombotic manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Blood 2020; 136:489–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ciccullo A, Borghetti A, Zileri Dal Verme L, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and clinical outcome in COVID-19: a report from the Italian front line. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020; 56:106017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heffernan DS, Monaghan SF, Thakkar RK, et al. Failure to normalize lymphopenia following trauma is associated with increased mortality, independent of the leukocytosis pattern. Crit Care 2012; 16:R12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chien M, Anderson T, Jockusch S, et al. Nucleotide analogues as inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 polymerase. bioRxiv 2020.03.18.997585 [Preprint]. 20 March 2020. Available at: 10.1101/2020.03.18.997585. Accessed 14 September 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zumla A, Chan JFW, Azhar EI, et al. Coronaviruses—drug discovery and therapeutic options. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2016; 15:327–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McKee DL, Sternberg A, Stange U, et al. Candidate drugs against SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Pharmacol Res 2020; 157:104859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, et al. A trial of lopinavir–ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe COVID-19. N Eng J Med 2020; 382:1787–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li Y, Xie Z, Lin W, et al. Efficacy and safety of lopinavir/ritonavir or arbidol in adult patients with mild/moderate COVID-19: an exploratory randomized controlled trial. Med (N Y) 2020; 1:105–13.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.