Procalcitonin (PCT) is widely considered an essential tool for identification and monitoring of patients with suspected and proved bacterial infections, to determine clinical severity and to assess the response to antibiotic therapy [1]. Moreover, recent studies demonstrated the association between PCT values and etiology of infection, with higher PCT concentrations detected in Gram-negative etiology, compared to Gram-positive and fungal infections [2, 3].

In a recent real-world study on hospitalized patients admitted with respiratory symptoms and suspected lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI), Johnson et al. evaluated clinical outcomes and costs associated with PCT use in different clinical situations: patients with pneumonia, heart failure, viral respiratory infection, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [4]. Of importance, the PCT assessment was associated with reduced antibiotic use, length of stay, and mortality. Furthermore, patients who underwent PCT testing with a negative result were observed to have a 1.7-day shorter mean duration of antibiotics, a shorter mean length of stay of 1.5 days, and the lowest healthcare costs without an increase in adverse outcomes. Of interest, patients with PCT assessment, regardless of the PCT result, were less likely to be readmitted within 30 days.

As a matter of fact, it is plausible that the PCT concentrations can drive physicians to an early diagnosis and an appropriate choice of therapy, also avoiding readmissions for patients who may have received an incorrect empiric therapy. In the study of Johnson and coworkers, PCT testing results a valid tool to manage not only patients with bacterial LRTI but also those with other etiologies including non-infective and viral causes of hospitalization.

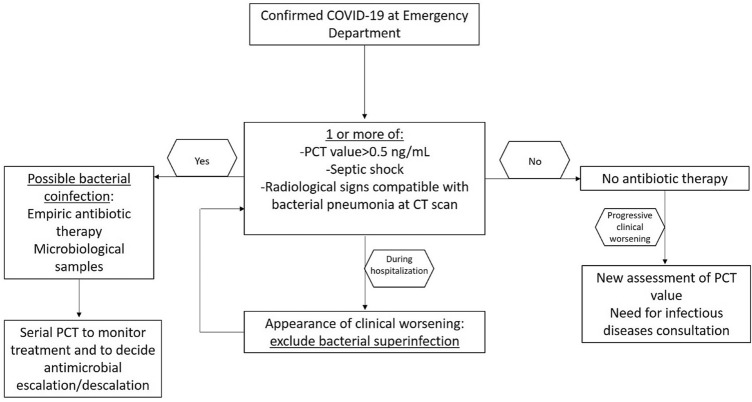

To date, PCT can be considered a useful tool for clinicians to manage at time of hospitalization patients with suspected infection by SARS-CoV-2 and to promptly distinguish this population from patients with bacterial etiology (see Fig. 1) [5]. Moreover, PCT results as one of the most important determinant to early detect and to monitor bacterial coinfections and superinfections in COVID-19 patients [5, 6]. Of importance, in a recent experience on 1461 patients with COVID-19, a PCT value > 0.5 ng/mL increased the risk of in-hospital mortality [7]. Finally, in a meta-analysis about risk factors for severity and death during COVID-19, a PCT value > 0.5 ng/mL was associated with a higher risk of progression to critical illness [8].

Fig. 1.

Management of COVID-19 patients at emergency department and during hospitalization

In vitro and in vivo models showed that PCT synthesis is stimulated by IL-6 and TNFα increase [9]. The inflammatory responses induced in immune cells (but also epithelial and endothelial cells) were demonstrated to be crucial in stimulating a cytokine storm, leading to severe injury also in COVID-19 patients [10]. IL-6 is considered to be one of the key mediator of this cytokine storm, causing lung injury and the progression of COVID-19. As reported in several studies, the levels of serum IL-6 were elevated and IL-6 receptors were significantly expressed in patients affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection [11, 12]. Thus, high PCT values may be associated with severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the measurement of PCT, especially in the first days of hospitalization, may help physicians to assess the hyper inflammatory activity and to rule out bacterial and fungal coinfection or superinfection [13, 14].

However, research is needed to clarify if the increase in serum inflammatory markers is directly caused by SARS-CoV-2 or should be considered an indirect consequence of patients’ clinical status, especially in a population with chronic diseases that, like infectious diseases, can trigger a chronic proinflammatory state. Patients with such comorbidities are more likely to develop severe COVID-19 than healthy patients, at least partly for a dysfunction of innate immune response, increasing the risk of COVID-19 progression. Monitoring inflammatory markers may represent as an early warning system for progression to a more severe clinical condition.

It is important to underline that monitoring PCT levels can allow early detection of bacterial infections, which may reduce inappropriate prescription of antibiotics or trigger an early antibiotic therapy to treat the first stage of sepsis and other severe infective conditions [15]. Of importance, all the observed advantages associated with PCT utilization in the study of Johnson et al. were limited to patients not requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission [4]. In this context, the use of PCT resulted to be more efficacious in ICU patients where the decrease of PCT of > 80% over 72 h from ICU admission may provide prognostic information in critically ill patients and drive physicians to the discontinuation of antibiotic therapy [16–18].

In conclusion, the high PCT values reported in COVID-19 patients could be associated with the severity of infection and not only with the presence of bacterial coinfection or superinfection; for all these reasons, the combination of patient’s clinical status with laboratory tests and imaging is crucial in daily practice to assess the likelihood of bacterial coinfection in patients with COVID-19 [19], (see Fig. 1). PCT should be included in a diagnostic stewardship to apply the well-known strategies for an appropriate antimicrobial prescription [20].

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hamade B, Huang DT. Procalcitonin: where are we now? Crit Care Clin. 2020;36:23–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2019.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassetti M, Russo A, Righi E, Dolso E, Merelli M, et al. Role of procalcitonin in bacteremic patients and its potential use in predicting infection etiology. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2019;17:99–105. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2019.1562335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassetti M, Russo A, Righi E, Dolso E, Merelli M, et al. Role of procalcitonin in predicting etiology in bacteremic patients: report from a large single-center experience. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson SA, Rupp AB, Rupp KL, et al. Clinical outcomes and costs associated with procalcitonin utilization in hospitalized patients with pneumonia, heart failure, viral respiratory infection, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Intern Emerg Med. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02618-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russo A, Bellelli V, Ceccarelli G, Marincola Cattaneo F, Bianchi L, Pierro R, Russo R, Steffanina A, Pugliese F, Mastroianni CM, d’Ettorre G, Sabetta F. Comparison between hospitalized patients affected or not by COVID-19 (RESILIENCY study) Clin Infect Dis. 2020;18:ciaa11745. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia-Vidal C, Sanjuan G, Moreno-García E, Puerta-Alcalde P, Garcia-Pouton N, et al. (2020) Incidence of co-infections and superinfections in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bahl A, Van Baalen MN, Ortiz L, Chen NW, Todd C, Milad M, Yang A, Tang J, Nygren M, Qu L. Early predictors of in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19 in a large American cohort. Intern Emerg Med. 2020;15:1485–1499. doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02509-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng Z, Peng F, Xu B, Zhao J, Liu H, Peng J, Li Q, Jiang C, Zhou Y, Liu S, Ye C, Zhang P, Xing Y, Guo H, Tang W. Risk factors of critical and mortal COVID-19 cases: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020;81:e16–e25. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nijsten MW, Olinga P, The TH, et al. Procalcitonin behaves as a fast responding acute phase protein in vivo and in vitro. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:458–461. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200002000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azkur AK, Akdis M, Azkur D, Sokolowska M, Van De Veen W, Bruggen MC, et al. Immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and mechanisms of immunopathological changes in COVID-19. Allergy. 2020;75:1564–1581. doi: 10.1111/all.14364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu BW, Li M, Zhou ZG, Guan X, Xiang YF. Can we use interleukin-6 (IL-6) blockade for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—induced cytokine release syndrome (CRS)? J Autoimmun. 2020;111:102452. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J, Li S, Liu J, Liang B, Wang X, Wang H, et al. Longitudinal characteristics of lymphocyte responses and cytokine profiles in the peripheral blood of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. EBioMedicine. 2020;55:102763. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danwang C, Endomba FT, Nkeck JR, Wouna DLA, Robert A, Noubiap JJ. A meta-analysis of potential biomarkers associated with severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Biomark Res. 2020;8:37. doi: 10.1186/s40364-020-00217-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russo A, Tiseo G, Falcone M, Menichetti F. Pulmonary aspergillosis: an evolving challenge for diagnosis and treatment. Infect Dis Ther. 2020;9:511–524. doi: 10.1007/s40121-020-00315-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji P, Zhu J, Zhong Z, Li H, Pang J, Li B, Zhang J. Association of elevated inflammatory markers and severe COVID-19: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e23315. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000023315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuetz P, Maurer P, Punjabi V, Desai A, Amin DN, Gluck E. Procalcitonin decrease over 72 hours in US critical care units predicts fatal outcome in sepsis patients. Crit Care. 2013;17:R115. doi: 10.1186/cc12787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alessandri F, Pugliese F, Angeletti S, Ciccozzi M, Russo A, Mastroianni CM, d’Ettorre G, Venditti M, Ceccarelli G. Procalcitonin in the assessment of ventilator associated pneumonia: a systematic review. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/5584_2020_591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bassetti M, Russo A, Righi E, Dolso E, Merelli M, Cannarsa N, D'Aurizio F, Sartor A, Curcio F. Comparison between procalcitonin and C-reactive protein to predict blood culture results in ICU patients. Crit Care. 2018;22:252. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2183-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falcone M, Bassetti M, Tiseo G, Giordano C, Nencini E, Russo A, Graziano E, Tagliaferri E, Leonildi A, Barnini S, Farcomeni A, Menichetti F. Time to appropriate antibiotic therapy is a predictor of outcome in patients with bloodstream infection caused by KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Crit Care. 2020;24:29. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2742-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wirz Y, Meier MA, Bouadma L, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic treatment on clinical outcomes in intensive care unit patients with infection and sepsis patients: a patient-level meta-analysis of randomized trials. Crit Care. 2018;22:191. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2125-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]