Abstract

Background:

Whereas cardiovascular disease (CVD) metrics define risk in individuals above age 40 years, the earliest lesions of CVD appear well before this age. Despite the role of metabolism in CVD antecedents, studies in younger, biracial populations to define precise metabolic risk phenotypes are lacking.

Methods:

We studied 2330 white and Black young adults (mean age 32 years, 45% Black) in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study to identify metabolite profiles associated with an adverse CVD phenome (myocardial structure/function, fitness, vascular calcification), mechanisms, and outcomes over two decades. Statistical learning methods (elastic nets/principal components analysis) and Cox regression generated parsimonious, metabolite-based risk scores validated in >1800 individuals in the Framingham Heart Study (FHS).

Results:

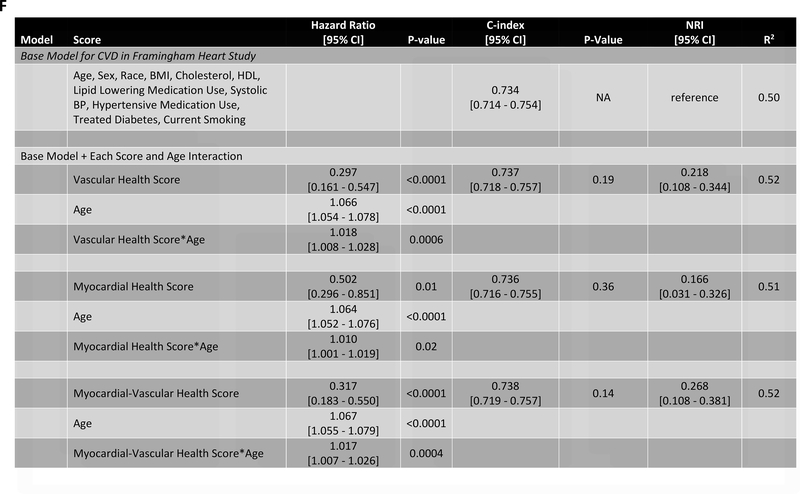

In CARDIA, metabolite profiles quantified in early adulthood were associated with subclinical CVD development over 20 years, specifying known and novel pathways of CVD (e.g., transcriptional regulation, BDNF, NO, renin-angiotensin). We found two multi-parametric, metabolite-based scores linked independently to vascular and myocardial health, with metabolites included in each score specifying microbial metabolism, hepatic steatosis, oxidative stress, NO modulation, and collagen metabolism. The metabolite-based vascular scores were lower in men, and myocardial scores were lower in Blacks. Over nearly 25 year median follow-up in CARDIA, the metabolite-based vascular score (HR = 0.68 per SD; 95% CI 0.50–0.92, P=0.01) and myocardial score (HR=0.60 per SD; 95% CI 0.45–0.80, P=0.0005) in the third and fourth decade of life were associated with clinical CVD with a synergistic association with outcome (Pinteraction=0.009). We replicated these findings in 1898 individuals in FHS over 2 decades, with a similar association with outcome (including interaction), reclassification, and discrimination. In FHS, the metabolite scores exhibited an age interaction (P=0.0004 for a combined myocardial-vascular score with incident CVD), such that young adults with poorer metabolite-based health scores had highest hazard of future CVD.

Conclusions:

Metabolic signatures of myocardial and vascular health in young adulthood specify known/novel pathways of metabolic dysfunction relevant to CVD, associated with outcome in two independent cohorts. Efforts to include precision measures of metabolic health in risk stratification to interrupt CVD at its earliest stage are warranted.

Keywords: Cardiometabolic disease, Metabolomics, Lipidomics, Prevention, Aging

INTRODUCTION

Whereas contemporary cardiovascular disease (CVD) prediction identifies individuals above age 40 years at clinical risk1, the earliest lesions of CVD appear well before this age. Autopsy studies over the last three decades have identified primordial CVD lesions in young adulthood (age under 34 years)2. Early, sustained exposure to heightened cardiometabolic risk (e.g., dyslipidemia, dysglycemia, hypertension) contributes substantially to CVD in mid-life and beyond2–4. Further, recent Mendelian randomization studies suggest life-long exposure to a healthy blood pressure and anti-atherogenic lipid profile may be protective5, and early CVD risk may be conferred by clinical traits below treatment thresholds established for clinical risk prediction in older adults6. Indeed, subclinical atherosclerosis is present by mid-life in individuals despite lipids and blood pressure falling within an otherwise normal range in young adulthood3. One explanation for this observation is that metabolic antecedents of standard CVD risk factors may be more physiologically relevant in younger individuals. Indeed, dysregulated metabolism appears to be at the heart of several chronic diseases, including aging, CVD, cancer, and diabetes. Nevertheless, most studies of CVD focus on older adults, which limits risk prediction for and molecular pathogenesis of CVD in a younger population when intervention may be most impactful.

In the present study, we analyzed 410 circulating metabolites in 2330 white and Black young adults (mean age 32 years) in a large multi-site study of CVD development (the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study, CARDIA) to identify metabolic pathways at the heart of CVD pathogenesis in young adulthood. Using integrative statistical learning methods alongside multiple, serial phenotypes across the heart and vascular system over nearly 20 years, we identified independent metabolic signatures of myocardial and atherosclerotic vascular disease and their race and sex-stratified distributions. We measured the association of these signatures with CVD and mortality in CARDIA, with subsequent validation across a wide range of age in the Framingham Heart Study Offspring Cohort with two decades of follow-up. Our primary hypothesis was that early perturbations in metabolism (as reflected by circulating metabolome) would pinpoint predisposition to cardiovascular disease early in life, thus identifying potentially targetable molecular pathways at a time when modifiability and prevention is most fruitful.

METHODS

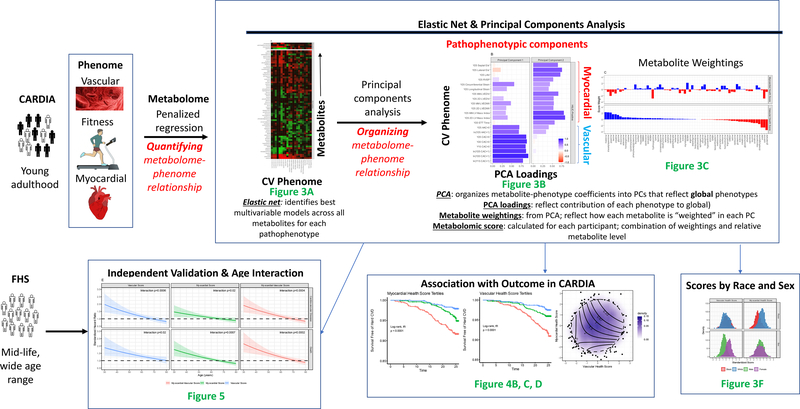

The overall study scheme is shown in Figure 1. Study cohort description, metabolite profiling and exposure definitions (the cardiovascular phenome) are defined below. Associations between metabolites and each cardiovascular phenotype were calculated using regression methods (including elastic net-PCA; described in Expanded Methods, Figures I–V in Supplement), organized into principal components PCs, and regressed against outcomes in CARDIA and FHS. Because of the sensitive nature of the data collected for this study, requests to access the dataset from qualified researchers trained in human subject confidentiality protocols may be sent to the CARDIA Study (https://www.cardia.dopm.uab.edu) and the Framingham Heart Study (https://framinghamheartstudy.org).

Figure 1. Study scheme.

Diagram of study design. Each step in the performance of this work is detailed, with corresponding major figures referenced in green font. This figure is a “roadmap” for the scientific approach with example figure layouts drawn from figures in this manuscript as a guide.

Study cohorts

The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study is a prospective cohort study of 5115 white and Black participants (age 18–30 years recruited in 1985–1986 from 4 field centers in the United States: Birmingham, AL; Chicago, IL; Minneapolis, MN; and Oakland, CA) aimed to identifying risk factors for cardiovascular disease in young adulthood7–10. In this sub-study, we performed metabolite profiling in 2358 individuals at the Year 7 visit in CARDIA without prior CVD with fasting blood (>8 hours) selected across a spectrum of metabolic trajectories adding additional available cases of incident CVD with available fasting blood (mean age 32.1±3.6 years; 45% female, 45% Black)11. The comparison of the analytic subsample with present covariates (N=2330) with the overall cohort that attended Year 7 is shown in Table I in the Supplement. The assessment of standard cardiovascular risk factors in CARDIA has been previously reported.

For validation of associations between metabolite-based signatures of CVD with subclinical phenotypes and clinical outcomes, we examined 1898 participants of the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) Second Generation (Offspring) cohort 5th Examination with fasting metabolite profiles measured at the same time (>8 hour fasting; age 54.9±9.7 years; 52.4% women)12. All individuals included in this study provided written informed consent, and the CARDIA and FHS studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board at each participating institution.

Metabolite profiling

Metabolite profiling in CARDIA was performed as described in the Expanded Methods (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA) via standard liquid chromatography-mass spectrometric (LC-MS) techniques13, 14. Metabolite profiling in the FHS was performed as previously described12 and detailed in the Expanded Methods.

Subclinical measures of cardiovascular disease

We utilized three major measures of subclinical CVD that have been associated with future clinical CVD in multiple studies: (1) those relating to myocardial health and function (echocardiographic phenotypes); (2) those relating to vascular health (calcification across multiple vascular beds) and (3) cardiorespiratory fitness (treadmill exercise time)15–19. Two-dimensional echocardiography was performed in CARDIA at Year 25 as previously reported, with quantification of prognostic subclinical markers of cardiac structure and function, including left ventricular mass and volumes (indexed to height2.7) and the ratio of mass to end-diastolic volume (by M-mode and two-dimensional techniques), left ventricular strain, right ventricular systolic pressure, left atrial volume, and tissue Doppler measures of diastolic function20–22. Total exercise time on a standardized treadmill protocol performed at Year 20 was also included, given its strong association with cardiac outcomes in multiple large studies, including in young adults19, and its role as an integrated biomarker of cardiovascular performance. Computed tomography imaging for coronary calcium score at Years 15, 20, and 25 and for abdominal calcium score at Year 25 were included as vascular markers of subclinical CVD, as described17, 23. Left atrial volumes and left ventricular mass and volumes were indexed to height.

Outcomes

Our primary clinical outcome in CARDIA was survival free of hard CVD (defined as fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, stroke, congestive heart failure, carotid artery disease, or peripheral arterial disease) with a secondary outcome of all-cause mortality. Survival time was measured from Year 7 study visit to censoring (event, loss to follow-up, or last contact). For FHS, our primary outcome for validation was all-cause CVD across coronary and peripheral vascular beds, including chest pain or angina; myocardial infarction; heart failure; cardiac catheterization; percutaneous or surgical coronary revascularization; suspected or confirmed stroke, transient ischemic attack or carotid revascularization; peripheral vascular disease or revascularization; and venous thromboembolism. Our secondary outcome was all-cause mortality. In incident CVD analyses, individuals with a history of CVD before Exam 5 were excluded. Survival time was measured from Exam 5 study visit to censoring or occurrence of an event at the last survival file from the cohort study. Detailed description of event ascertainment and adjudication methods are available directly from CARDIA (https://www.cardia.dopm.uab.edu/images/more/2020/CARDIA_Endpoint_Events_MOO_v10_09_2017_with_reports_instructions.pdf) and FHS (https://framinghamheartstudy.org/files/2019/05/MO-Endpoint-Review-v2.0-msp.pdf).

Statistical methods

Exposure preparation:

Distributions of continuous subclinical endpoints and covariates were graphically examined. CAC was transformed with as the natural logarithm of CAC+1, as is customary. ETT time was sufficiently normal and was not transformed. All remaining continuous endpoints and covariates were subjected to hyperbolic arcsine transformation to improve normality. Pooled cohort equation (PCE) risk was calculated as specified by the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology, setting age to 40 years (the minimum age for which the risk assessment is calibrated). All continuous endpoints and covariates and were then mean centered and standardized for further analysis. Missing values of metabolites were imputed at half the minimum value. All metabolites were then log transformed. Within each metabolomic platform, correlations among all metabolites were computed and plotted in heatmap format ordered by complete-linkage clustering. Principal component analysis was performed for metabolites, by metabolomic platform, with varimax rotation of the 10 metabolites with largest eigenvalues.

Single metabolite regressions:

First, we regressed each subclinical CVD outcome against each metabolite using linear or logistic regression, as appropriate. Three sets of models were constructed: (1) unadjusted, (2) adjusted for age, sex and race and (3) adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, cholesterol, HDL, systolic blood pressure, hypertensive medication use, diabetes, and smoking status (never, former, or active). In each case, Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate control was applied within each combination of outcome, metabolomic platform and adjustment set. Venn diagrams were generated for metabolites which remained significant in age, sex and race-adjusted models using four CVD endpoint groups: fitness (treadmill time), vascular calcification (ln(CAC + 1) at year 25 or ln(AAC + 1) at year 25), LV mass (by either 2D or M-mode) and LV strain (longitudinal or circumferential).

Elastic net and PCA:

While single metabolite-outcome approaches have been widely used to identify molecular correlates of CVD, these approaches do not capture interconnected networks of multiple metabolites that specify shared and distinct metabolic pathways and may be limited by statistical precision in modeling disease predisposition. We therefore used multivariable learning algorithms employed frequently to optimize selection of analytes most closely linked to an outcome of interest. First, both the polar and lipid metabolome were decomposed using principal components analysis (PCA), with associations between each PC and cardiac phenotype estimated via linear regression.

Second, in order to find a parsimonious set of metabolites best related to each subclinical CVD endpoint, we used elastic net regression and subsequent PCA of the regularized regression coefficients across the polar metabolites using cross-validation to optimize hyperparameters α and λ. This novel, two-phase regression approach (“elastic net-PCA”; described further in the Expanded Methods) (1) selected the best explanatory model for each subclinical CVD endpoint (“elastic net” component) and (2) used the strength of the relations between the metabolome and phenome (as opposed to each metabolite or endpoint individually) to identify a metabolic network linked to future adverse cardiovascular phenotypes (the “PCA” component). In this approach, the resulting principal components (PCs) describe the major relations between the metabolome and the CVD phenome (e.g., each PC is loaded on a given myocardial, fitness, or vascular phenotype). Each metabolite is then weighted on each PC (reflecting the strength of relationship of that metabolite to the PC). Operationally, the unadjusted beta coefficients from elastic net models were combined into a matrix and plotted in heat map format with metabolites ordered using complete-linkage clustering and endpoints ordered into clinically relevant groups. We then performed principal component analysis with varimax post-rotation and selected two principal components based on analysis of loadings. We used the principal component scores for each metabolite as weights for generating a vascular and myocardial score for each subject, respectively. Scores were standardized.

Survival analysis:

The relationship between these scores and the primary endpoint of “hard” cardiovascular disease was evaluated using Cox regression with adjustment for age, sex, race, body mass index, cholesterol, HDL, systolic blood pressure, hypertensive medication use, diabetes, and smoking status (never, former, or active). Similar analysis was conducted for the secondary endpoint of death from any cause. Survival plots across tertiles of the scores for each outcome were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Time-to-event analysis began at Year 7 (time of metabolite profiling) and participants were censored at the latest date of follow-up within CARDIA. Because the scores were both statistically significant along with a multiplicative-interaction wherein adverse (low values) of both scores was especially adverse, we also constructed a combined “myocardial-vascular health” score as the sum of the vascular and myocardial health scores. Effect modification was evaluated for age, sex and race on each of these scores. Model R2 was computed using the method of Xu and O’Quigley24. A continuous net reclassification improvement (NRI) was computed at the 75th percentile of follow-up time using methods for censored data25.

FHS validation:

Because not all of the identified metabolites required for the scores were measured in the FHS validation cohort, we then fit reduced metabolite scores using linear regressions wherein the full scores (standardized) were the response variables and levels of the metabolites available for validation in FHS were the predictors (44 available in FHS out of 66 metabolites used in scores in CARDIA). Of note, metabolites that were included were missing in less than 15% participants (assumed below detection limit). Similar to our approach in CARDIA, we imputed 50% of the lowest measured value on a per metabolite level for individuals with missing values (median fraction of imputed data 0%, range 0%−12.8%), log-transformed, and standardized metabolites before entering into score calculation. The three reduced metabolite scores were computed in FHS, standardized and validated against incident CVD (primary) and death (secondary) in FHS using Cox regression. Scores were robust to alternative imputation strategies (R2=0.99). We identified effect modification by age of all three scores using multiplicative interaction terms. Adjustments included age, sex, body mass index, cholesterol, HDL, lipid medication, systolic blood pressure, hypertensive medication use, diabetes, and current smoking.

R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used for statistical analyses. A two-sided P value less than 0.05 was considered significant, with type 1 multiplicity corrections using the FDR method, as specified above.

Pathway analysis:

The detailed methods for the pathway analysis are described in the Expanded Methods.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics

Characteristics of the 2330 individuals in CARDIA included in this study are shown in Table I in the Supplement (mean age 32.1±3.6 years; 45% women, 45% Black). The study sample was generally at low CVD risk (by standard CVD risk factors) at the time of metabolite quantification (Year 7), with a near normal average BMI (25.7±5.0 kg/m2), and low prevalent hypertension, and favorable lipid profiles (low density lipoprotein LDL 106±31 mg/dl, high-density lipoprotein HDL 54±14 mg/dl, triglycerides 74±43 mg/dl), but with a notable high prevalence of current or former smoking (39%). The comparison between our Year 7 subsample of CARDIA to the overall cohort attending Year 7 is shown in Table I in the Supplement. In comparison to CARDIA, the Framingham Heart Study Offspring cohort (Table II in the Supplement) was generally older, albeit with a wide range of ages (mean age 54.9±9.7 years; 52.4% women) and was white, with greater prevalence of CVD risk factors (18.4% hypertension, 2.1% diabetes, 6.3% treatment for lipids, 18.8% smoking). The comparison with the overall FHS Offspring Study at Exam 5 is also shown in Table II in the Supplement.

Metabolic dysfunction in young adulthood identifies molecular signatures and pathways linked to an adverse cardiovascular phenome up to two decades later

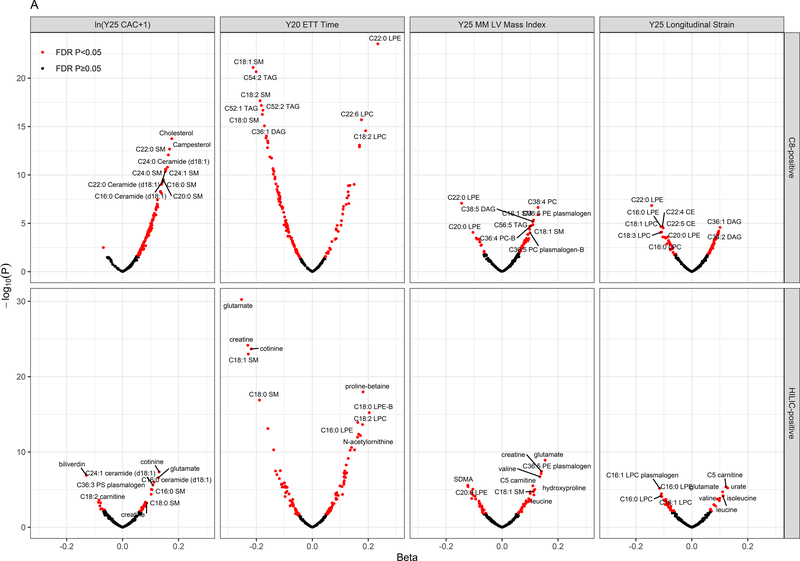

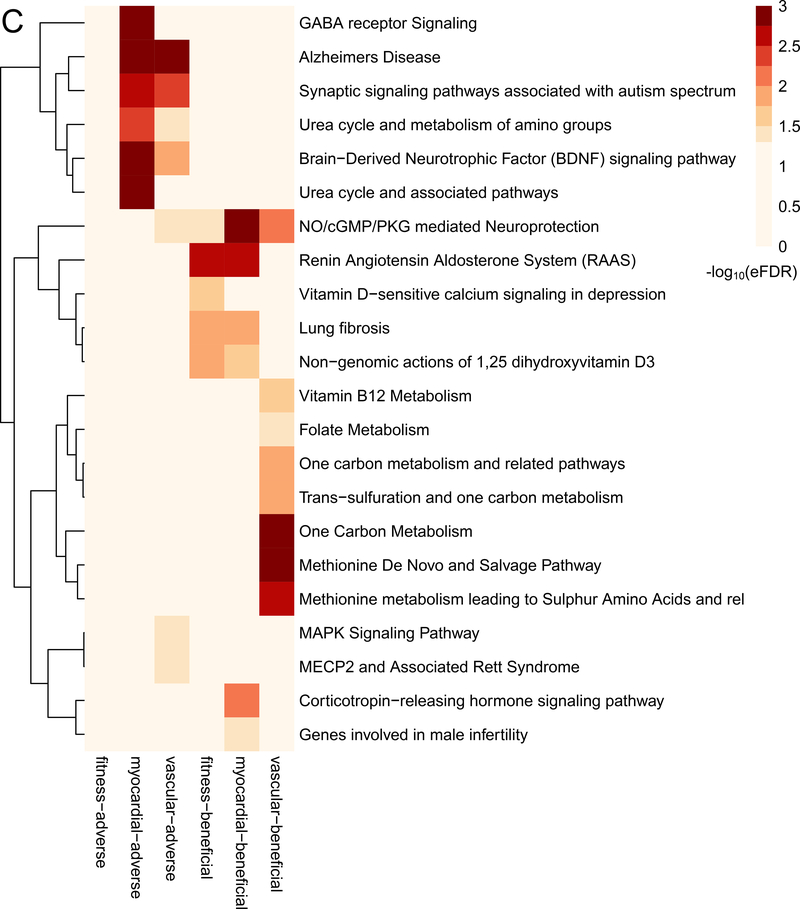

As a first step, we examined the association between metabolites measured in the third and fourth decades of life with the subsequent development of an adverse cardiovascular phenome up to 20 years later (single metabolite regressions in Methods; Supplemental Data File with number of endpoints noted in Table III in the Supplement, Figure 2A–B). Most metabolite-phenotype associations were “concordant” across phenotypes, simultaneously associated with “myocardial” traits (e.g., greater LV mass, lower LV strain, decreased cardiorespiratory fitness) and “vascular” traits (e.g., greater vascular calcification; as shown in the intersections of the significant associations in Figure 2B). Of note, in addition to cotinine (smoking exposure) and cholesterol, several metabolites associated with subclinical CVD phenotypes have been mechanistically implicated in endothelial dysfunction, insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and inflammation in older adults and model systems (e.g., glutamine/glutamate metabolism12, 26–28, branched chain/aromatic amino acid metabolism12, 29, dimethylguanidinovaleric acid [DMGV]30–32, sphingomyelin and ceramides33, 34, uric acid35). Using a network in silico approach linking metabolites to regulated pathways (Figure 2C), we observed canonical pathways of both myocardial and vascular remodeling previously implicated in model systems in CVD across several of these pathways, including brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) signaling36–38, NO/cGMP pathways, the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, vitamin D, MAPK signaling, and transcriptional regulation via methyl-CpG-binding protein-2 (MECP2) signaling.

Figure 2. Metabolites in early adulthood are associated with the cardiovascular phenome and identify pathways central to CVD development.

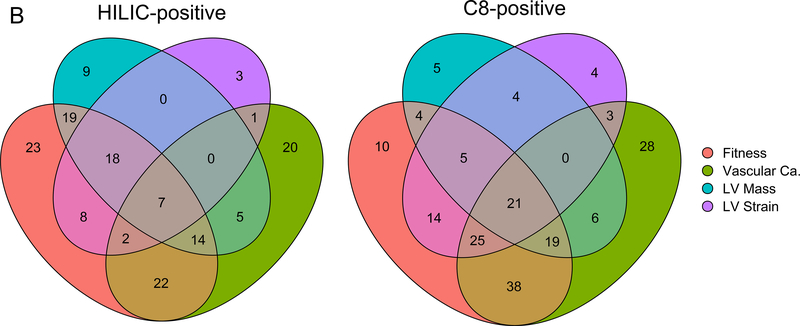

Figure 2A displays magnitude and significance in linear models of associations with four key parameters reflecting myocardial phenotypes, vascular phenotypes, and fitness (Year 25 coronary calcification [Y25 CAC]; Year 20 exercise tolerance time [Y20 ETT]; Year 25 echocardiographic left ventricular mass by M-mode [Y25 MM LV Mass, indexed as described]; Year 25 global longitudinal strain). Associations for both HILIC and C8 metabolite modes displayed. Beta coefficients displayed here are adjusted for age, sex and race. Red dots signify metabolites statistically significant at a 5% false discovery rate (Benjamini-Hochberg). Of note, metabolites associated with greater strain (positive beta coefficient), greater LV mass, greater calcification, and lower exercise duration (negative beta coefficient) are unfavorable. For example, glutamate was associated with adverse phenotypes across four phenotypes. The full set of associations across the full range of the measured cardiovascular phenome are tabulated in Supplemental Data File. Figure 2B displays a Venn diagram of metabolites significantly associated with four groups of phenotypes: fitness (treadmill time), vascular calcification (ln(CAC + 1) at year 25 or ln(AAC + 1) at year 25), LV mass (by either 2D or M-mode) and LV strain (longitudinal or circumferential).

“Vascular Ca.” indicates vascular calcification. Figure 2C display the results of pathway analysis. Figure 2C shows set analysis of enriched pathways from 6 sets of HILIC metabolite-linked genes. The heatmap color gradient is based on the -log10(empirically determined FDR value) of the pathway analysis results for the genes linked to each of the HILIC metabolites sets (columns).

Identifying metabolic networks of the cardiovascular phenome in young adulthood

To generate parsimonious associations between the metabolome and phenome, we next performed PCA and elastic net regressions (elastic net and PCA in Methods above). We observed more correlation in molecular information among lipid metabolites relative to polar metabolites (Figure VIa–b in the Supplement), consistent with fewer PCs required to explain a significant proportion of variance in the metabolome (Figure Vic in the Supplement). These findings suggested a greater diversity in non-redundant molecular information within polar metabolites. Several PCs in both classes of metabolites were related to the cardiovascular phenome (Figure VId in the Supplement, yellow boxes). We observed that several metabolites that defined PCs associated with subclinical CVD (e.g., those highly “loaded” in PCs related to subclinical CVD endpoints) were similar to those in single metabolite-phenotype analyses. Given its molecular and functional curation and greater diversity, we focused on the polar metabolome to define molecular networks of predisposition to early CVD.

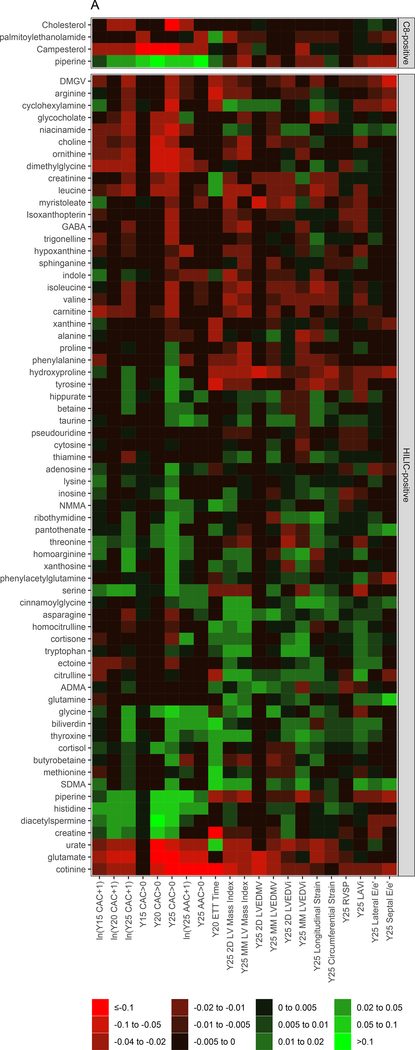

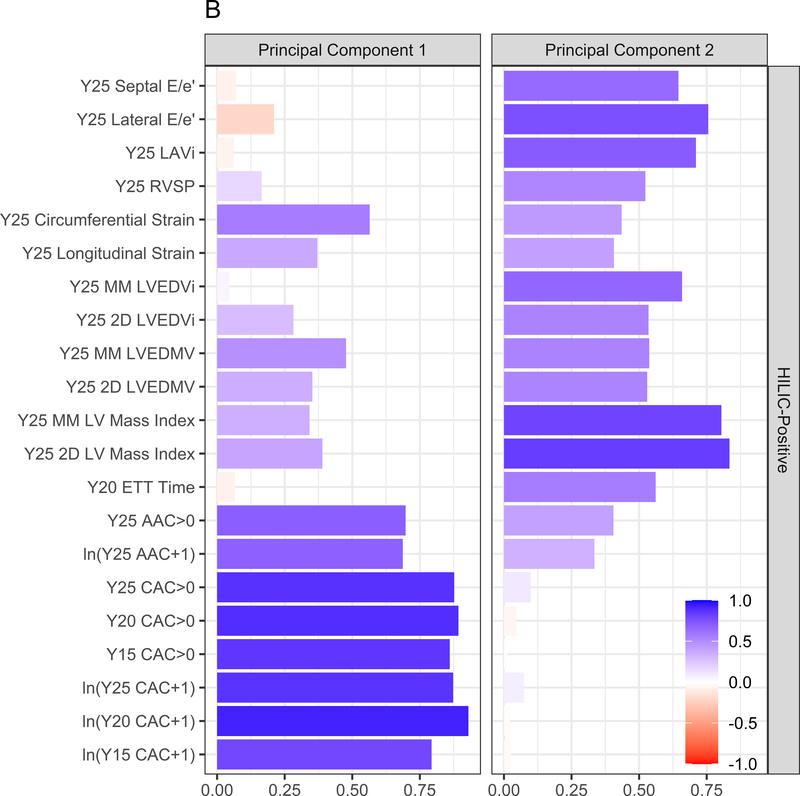

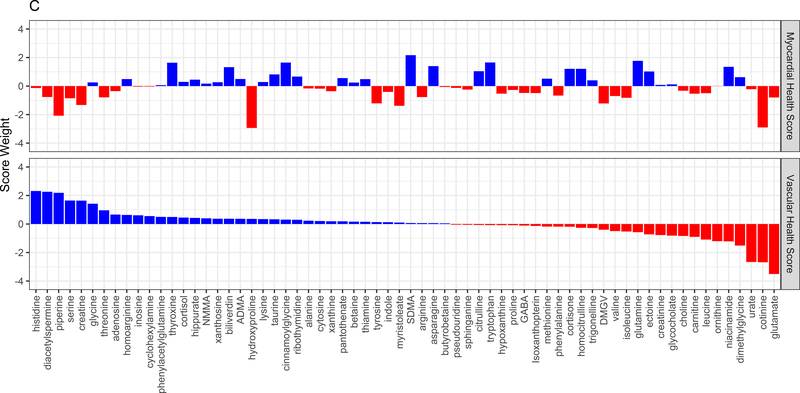

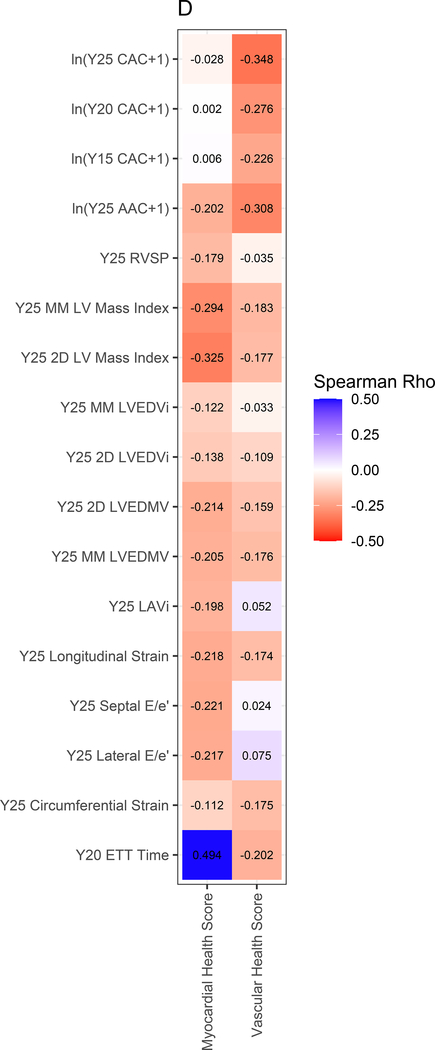

We next performed elastic net regression to identify a parsimonious set of polar metabolites associated with each subclinical CVD endpoint. The heatmap of the regression coefficients from each elastic net model is shown in Figure 3A (with the phenotype [dependent variable] in columns and the metabolites [independent variables] in rows, colorized by magnitude of association). A review of the distributions of metabolite-phenotype associations in Figure 3A suggested specific groups of metabolites may be related differently with myocardial versus vascular phenotypes. Therefore, we “decomposed” this heatmap of regression coefficients into PCs using a PCA approach. This approach yielded two PCs, which explained 56% of the total variance across all phenome-metabolome relations, with loadings of each PC on each phenotype shown in Figure 3B: PC1 appeared loaded more heavily on vascular phenotypes and PC2 appeared loaded more heavily on myocardial phenotypes. The corresponding weightings of each metabolite in each PC is shown in Figure 3C. Metabolic scores corresponding to vascular and myocardial traits (hereafter referred to as “vascular” and “myocardial health scores”) were subsequently generated for each CARDIA participant based on the linear combination of metabolite weighting and metabolite concentration.

Figure 3. Metabolic origins of myocardial and vascular health in early adulthood are distinct and diverge by race and sex.

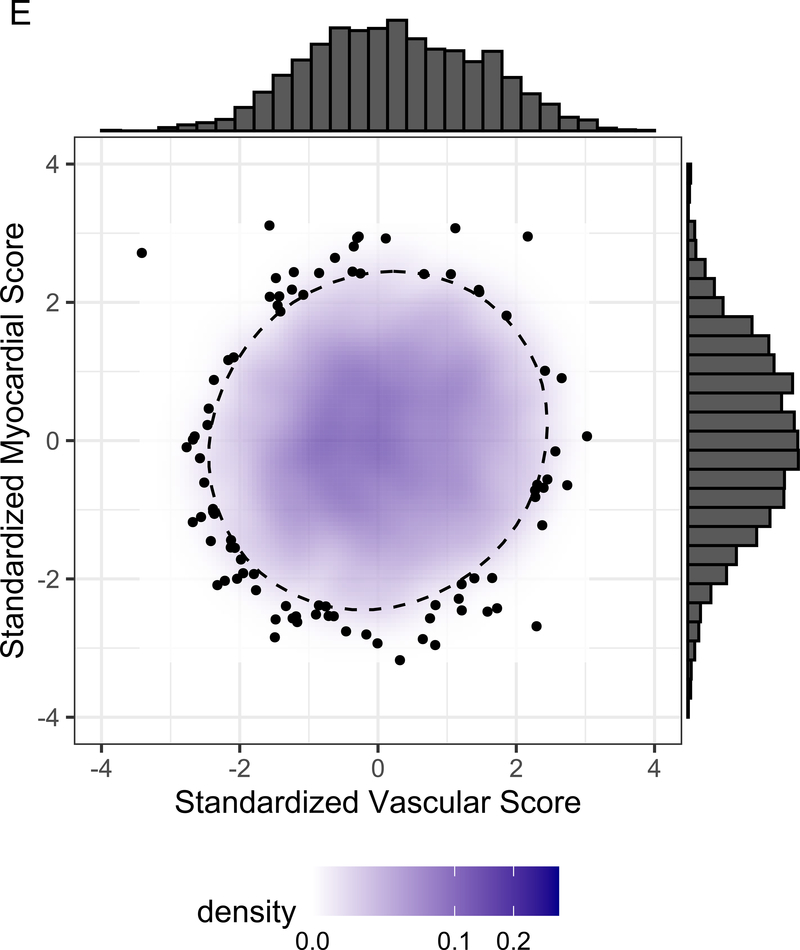

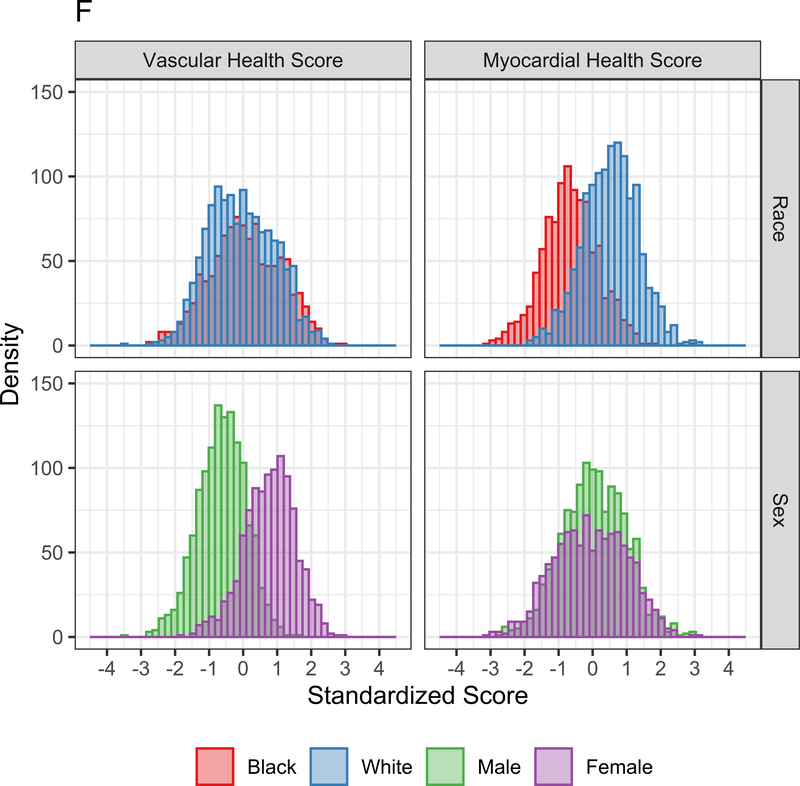

Figure 3A displays the regression coefficients of elastic nets specified for each phenotypic outcome in CARDIA, with outcomes in columns and metabolites in rows. Elastic net regressions included all metabolites measured in the HILIC and C8 platforms (separately). Metabolites with any non-zero coefficient for any outcome are displayed here in heatmap visualization, with the heatmap color key representing the magnitude of the regression coefficient. Coefficients for all subclinical endpoints except exercise duration were inverted such that a positive coefficient would be associated with a prognostically better value of the subclinical endpoint. Metabolites were ordered by complete-linkage clustering and subclinical CVD endpoints were ordered based on pathophysiology. Figure 3B shows loadings from a principal component analysis (PCA) of the elastic net regression coefficients from Figure 3A. This approach organizes the metabolite-phenome associations observed in the elastic net into those metabolites that are jointly related in a similar fashion to each set of phenotypes (“elastic net-PCA” approach described in Figure 1). This process yielded two PCs: the first PC loaded on the vascular phenome, and the second PC loaded on the myocardial phenome. The absolute value of the loading on each phenotype signifies how closely the underlying metabolite may be related to that phenotype. Figure 3C shows the relative weightings of each metabolite in each PC that are subsequently used in the construction of specific, independent myocardial and vascular health “scores.” Here, the blue color represents positive weighting (related to greater myocardial or vascular health), and the red color represents negative weighting (relative to poorer myocardial or vascular health). As noted, several metabolites in elastic net were similar to those observed in single metabolite-phenotype association (Figure 2A; e.g., glutamine, urate). Figure 3D shows Spearman correlation between the subsequent score (derived from summing the product of weightings in Figure 3C and individual metabolite levels, as described in Methods) and each phenotype. Figure 3E demonstrates the independence of vascular and myocardial health metabolite scores. The dashed line represents the 95% ellipse for the bivariate distribution. The cloud density and marginal histograms represent the fraction of CARDIA at each metabolomic score. Individual points outlying the 95% ellipse are also shown. Figure 3F shows the distribution of each score by sex and race, with a lower myocardial health metabolite score in Blacks (vs. whites) and a lower vascular health metabolite score in females (vs. males), consistent with epidemiologic observations of a higher heart failure risk in Blacks and greater atherosclerotic CVD risk in men.

As anticipated from our initial results with single metabolite-phenotype associations (Figure 2), the final elastic net-PCA-based myocardial and vascular scores were composed of metabolites (1) previously implicated in CVD (e.g., glutamate, phenylalanine, urate, branched-chain amino acids) and (2) metabolites spanning a variety of mechanistic pathways and outcomes including hepatic steatosis (DMGV), gut microbial metabolism (trigonelline, hippurate, cinnamoylglycine), longevity and oxidative stress (taurine), aerobic metabolic efficiency (pantothenate), nitric oxide modulation (symmetric and asymmetric dimethylarginine [SDMA, ADMA]), collagen metabolism (hydroxyproline), and a variety of other metabolites implicated in vascular injury and inflammation (dimethylglycine, tyrosine, niacinamide, histidine; Table IV in the Supplement). Metabolites in the scores are summarized in Table V in the Supplement, alongside their weightings.

By construction, higher vascular and myocardial health scores were associated with better vascular and myocardial phenotypes, respectively (Figure 3D), but were not themselves correlated with each other (Figure 3E). Consistent with differences in vascular and myocardial outcomes by sex and race, the vascular metabolic score was lower (worse) in men, while the myocardial metabolic score was lower in Blacks (Figure 3F). Standardized BMI only explained 4.8% and 15.8% of the variance in the vascular and myocardial scores, respectively (Pearson r=−0.21 and −0.39 for the vascular and myocardial scores, respectively, both P<0.0001). The magnitude of scores without inclusion of cotinine were similar to that of scores including cotinine (Figure VII in the Supplement).

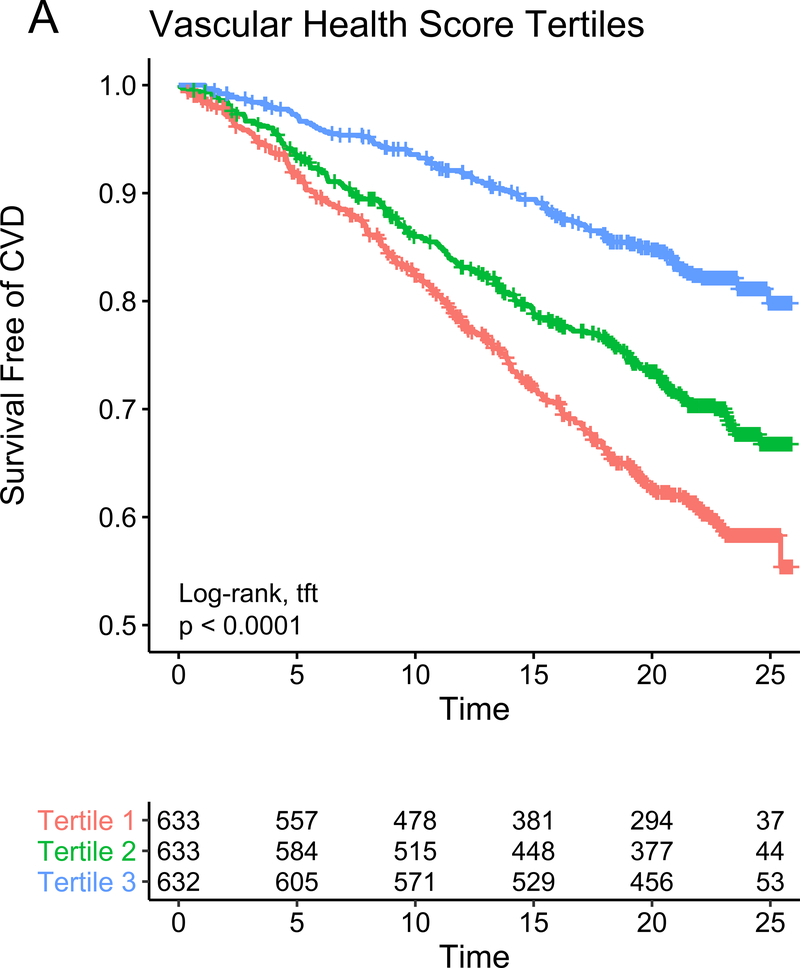

Metabolite networks associated with the cardiovascular phenome identify young adults at high risk for future CVD independent of clinical metrics

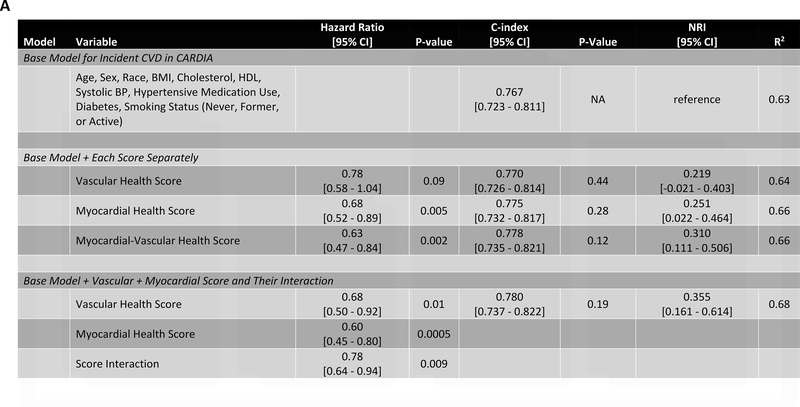

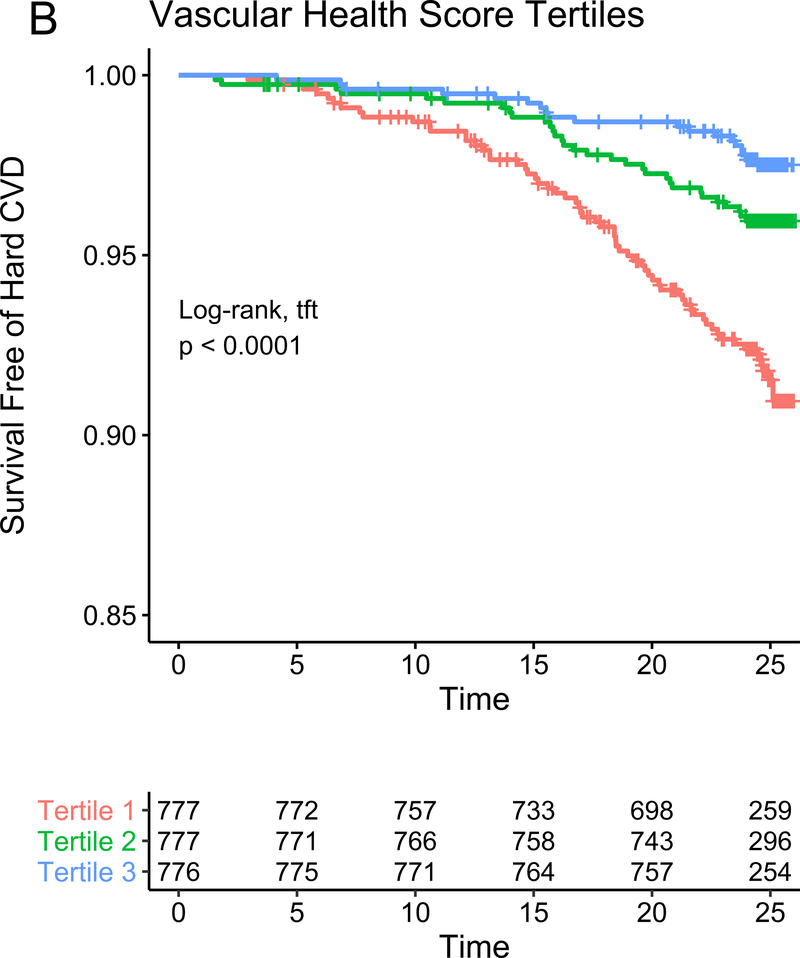

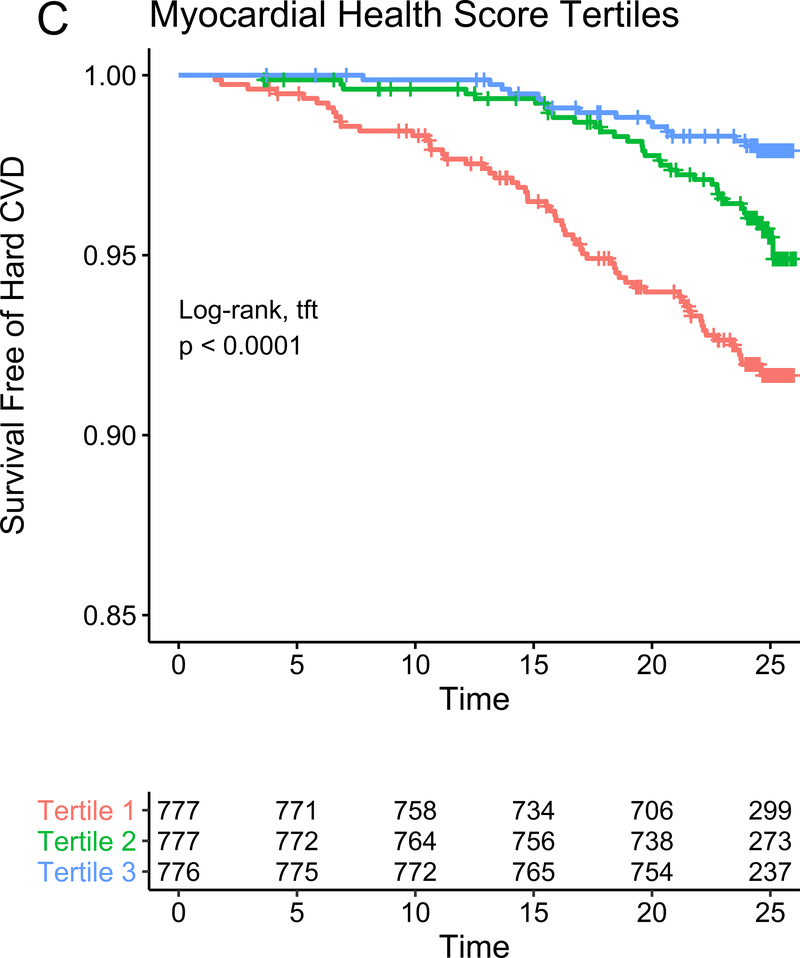

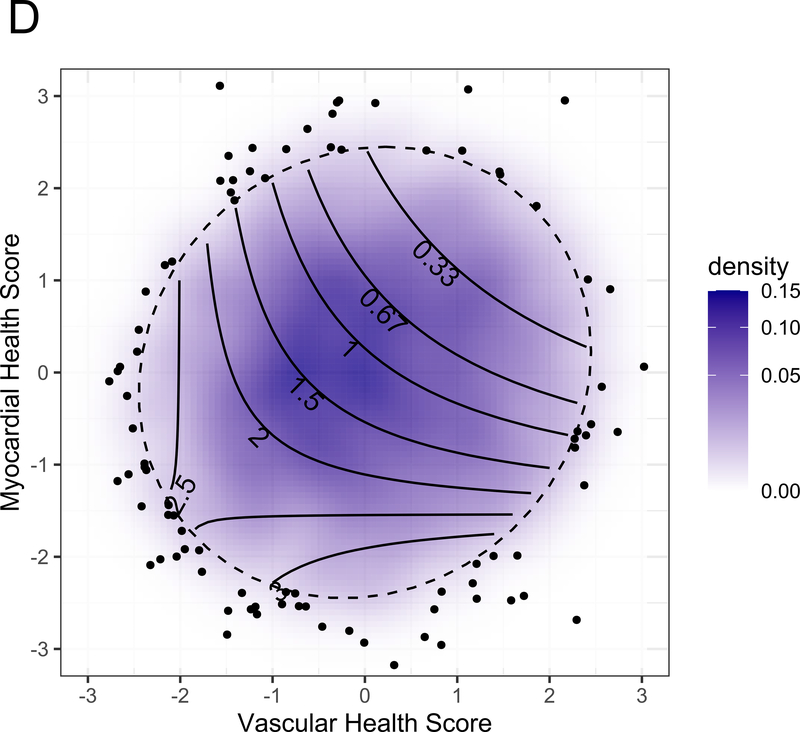

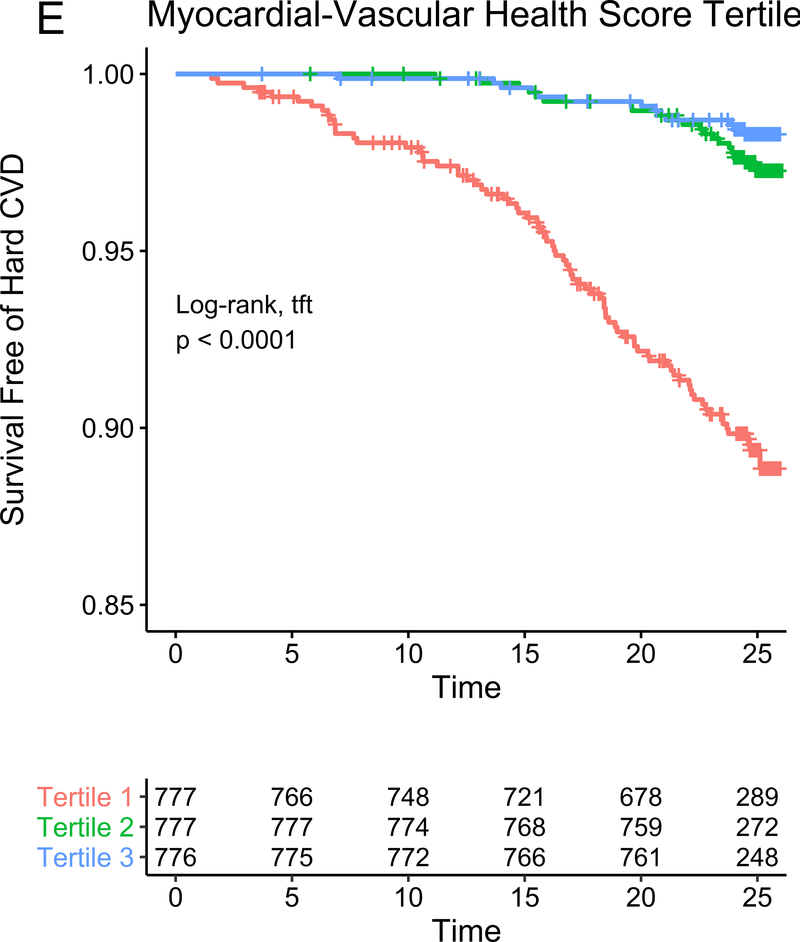

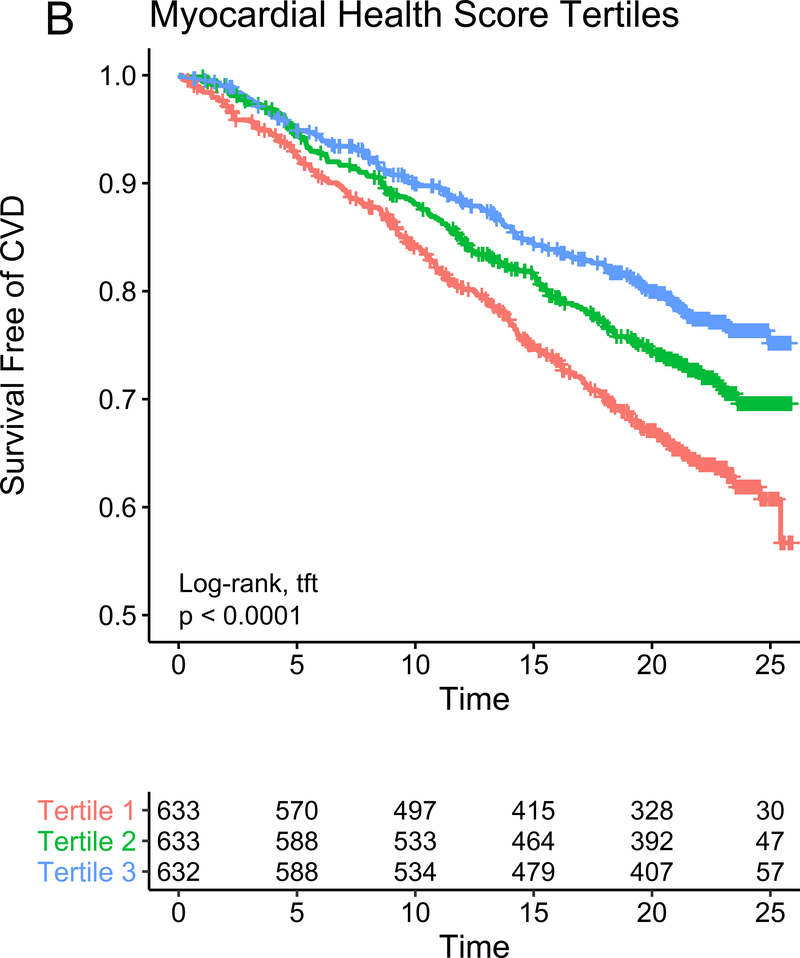

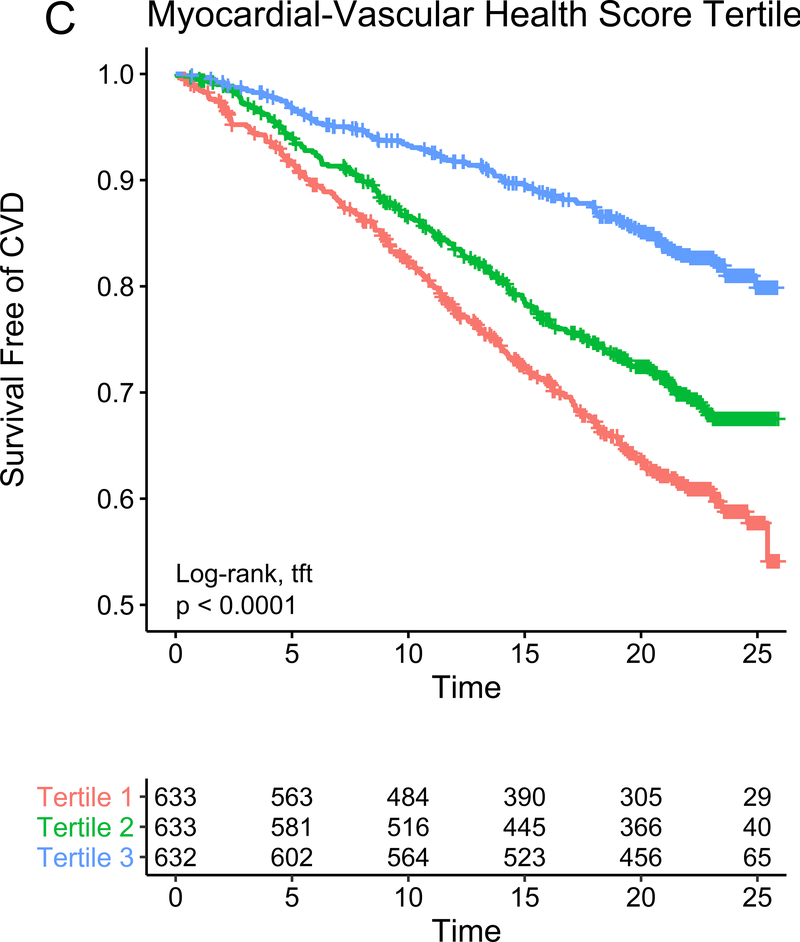

In our study subsample in CARDIA, we observed 113 hard CVD events and 135 deaths at 24.9 years median follow-up (IQR 24.7–25.0 years) for hard CVD and 24.9 years median follow-up (IQR 24.8–25.1 years) for death. The results of multivariable survival analysis (including reclassification and discrimination metrics) is shown in Figure 4A. In models with clinical risk factors, metabolic scores and their interaction, both vascular health (hazard ratio HR = 0.68 per 1 SD higher score; 95% CI 0.50–0.92, P=0.01) and myocardial health (HR=0.60 per 1 SD higher score; 95% CI 0.45–0.80, P=0.0005) measured in the third and fourth decade of life were associated with clinical CVD (Kaplan-Meier plots for hard CVD across tertiles of each score displayed in Figure 4B–C). Composite models demonstrated reclassification of risk above clinical variables (Figure 4A). In addition, we observed a statistically significant interaction between vascular and myocardial health on CVD (P=0.009), such that individuals with the lowest metabolic scores across both myocardial and vascular health had the highest hazard of CVD (Figure 4D). Consistent with this observation, we observed the highest “gradient” of risk in individuals with progressively lower scores on both myocardial and vascular health (Figure 4D, as evidenced by the close spacing of the hazard lines along a diagonal from bottom left to top right). Therefore, we constructed a composite “myocardial-vascular health” score based on the sum of each myocardial and vascular health score, which itself was associated with outcomes and provided risk reclassification for long-term outcome (Figures 4A, E). Of note, despite the differences in distribution of each score by race or sex (Figure 3F), we did not observe modification of the association between any score on either outcome by race or sex (Table VI in the Supplement). Relations of scores without cotinine to outcomes were similar (Figure VIIb in the Supplement). We also observed significant association of the vascular (but not myocardial score) with all-cause mortality, with significant improvement in reclassification for the vascular score (Figure VIII in the supplement), but no evidence of interaction between scores.

Figure 4. Metabolomic myocardial and vascular health in young adulthood are associated with long-term cardiovascular risk.

Figure 4A depicts the results of fully adjusted multivariable survival analysis for hard CVD (defined in Methods) for models containing the myocardial and vascular metabolite score and their multiplicative interaction (top three rows). Given their significant interaction, the myocardial and vascular metabolite scores were added together to produce a composite “myocardial-vascular health score.” The bottom three rows in Figure 4A shows the results of each score considered in separate fully adjusted models. Point estimates and confidence limits for reclassification (net reclassification index, NRI), discrimination (C-index), and fit statistics (R2) are depicted (and described in Methods). Base model adjustments are listed in Figure 4A. Figures 4B and 4C depict Kaplan-Meier (unadjusted) curves for survival free of hard CVD by tertiles of vascular and myocardial health metabolite score, with trend P value. Figure 4D is a visual depiction of the statistically significant interaction between myocardial and vascular health metabolite scores and long-term CVD. Here, the contours (solid black lines) represent the hazard ratio for hard CVD, and the cloud density represents the distribution of CARDIA participants across each score. The dashed line represents the 95% ellipse and individuals outside are plotted (to avoid overplotting within the cloud). Hazard (contour lines) for CVD increases most steeply (e.g., most “rapidly” crossing contours of hazard) across a diagonal from the top right to the bottom left, corresponding to jointly more negative myocardial and vascular metabolic health, suggesting the greatest risk is via a joint increase in both of them concurrently in young adulthood (evidence of interaction). Figure 4E is a Kaplan-Meier (unadjusted) curve for survival free of hard CVD by tertiles of the myocardial-vascular health score. The term tft indicates test for trend.

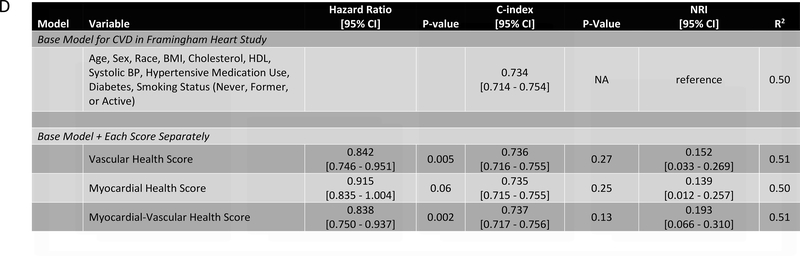

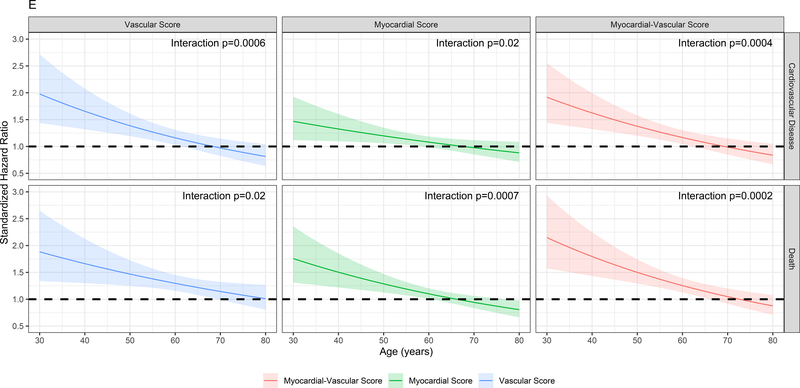

Finally, we sought to replicate our findings across a wider spectrum of age to test (1) whether metabolic networks in young adults based in the cardiovascular phenome apply across the adult lifespan and (2) the relative contributions of traditional risk factors versus these a high-dimensional metabolite-based score to risk stratification. We studied 1898 participants in the Framingham Heart Study Offspring cohort (mean age 54.9±9.7 years at metabolite measurement, range 29–82) who had undergone metabolite profiling at their fifth examination. We observed a total of 600 mortality events (median follow-up time 23.2 years [IQR 19.8–24.4 years]) and 518 CVD events (median follow-up time 21.5 years [IQR 13.5–23.4 years]). Of the 66 metabolites included in our CARDIA-based scores, 44 had been quantified in FHS with limited missingness and were included in validation. We generated re-weighted myocardial and vascular scores within CARDIA based on these 44 metabolites, with excellent correspondence to the full score (full versus reduced score correlations of Pearson r=0.97 and r=0.95 for the vascular and myocardial health scores, respectively, all P<0.0001; Figure IXa in the Supplement) and maintained associations with outcome (Figure IXb in the Supplement). The vascular (but not myocardial) health score was different by sex (directionally consistent with CARDIA; Figure Xa in the Supplement), and neither score was different across age in FHS (Figure Xb in the Supplement), implying age-independence in the distribution of prognostic measures of metabolic dysfunction. Higher vascular and myocardial health scores were both associated with a lower risk of hard CVD (hazard ratio 0.84 [95% CI 0.75–0.95] per 1 SD increase, P=0.005 for the vascular; and hazard ratio 0.92 [95% CI 0.84–1.00] per 1 SD increase, P=0.06 for the myocardial score, Figure 5), with a similar effect size in FHS for the myocardial-vascular health score. These metabolite-based scores again provided favorable risk reclassification for CVD beyond traditional clinical risk factors (NRI 0.152 [95% CI 0.033–0.269], 0.139 [95% CI 0.012–0.257] and 0.193 [95% CI 0.066–0.310] for the vascular, myocardial and myocardial-vascular health scores, respectively). Of note, we observed a strong interaction between age and myocardial, vascular and composite myocardial-vascular health score in association with CVD (for the myocardial-vascular health score: interaction P=0.0004 for CVD events, Figure 5E, F; P=0.0002 for death, Figure XId in the Supplement). Effectively, the adjusted hazard for CVD and mortality for each increment in metabolic health appeared greatest in young adulthood, even though the metabolic health scores themselves did not vary meaningfully across age. Similar results were seen for all-cause mortality (Figure XI in the Supplement), with an improvement in risk discrimination.

Figure 5. Metabolic origins of vascular and myocardial health are widely generalizable, with greatest risk in early adulthood.

Figure 5A-C shows Kaplan-Meier (unadjusted) survival curves for CVD (defined in Methods) for each score in FHS, alongside a fully adjusted multivariable survival analysis (Figure 5D) analogous to Figure 4A. Figure 5E demonstrates the expected marginal hazard for a 1-SD decrease (“poorer” metabolic health) in each metabolomic score across age for CVD and mortality. This figure demonstrates that the hazard of CVD or mortality in young adults for a change in metabolic health is higher relative to the same change later in life. Figure 5F shows the results of the multivariable survival models for CVD, including interactions. Of note, age is modeled in years (not standardized) for this analysis for clarity. The hazard ratios for each score are expressed per 1 SD increase (better health), and the hazard for metabolite-based score is expressed at an age of “0 years” for this table. The hazard for a 1-SD increase in metabolite-based score at any given age is calculated by adding effects from interaction to the base score term. The term tft indicates test for trend.

DISCUSSION

Understanding the antecedents of cardiovascular risk in younger adults—where intervention may exact a sustained, lifetime benefit—is a major goal of modern CVD prevention. Traditional approaches to CVD prediction have focused either on assessment of clinical risk factors (e.g., lipid profiles) or subclinical phenotypes on a mechanistic pathway toward outcome (e.g., cardiac hypertrophy in heart failure). While the pathologic antecedents of CVD occur early in life2, 39, selected risk factors and phenotypes (e.g., arterial calcification) may not be sufficiently abnormal (outside of those individuals with extreme calcification or familial hyperlipidemia) to be sufficiently predictive across the population for clinical utility17. Here, we use molecular measures of metabolism to identify specific metabolic features in young adulthood that capture long-term risk of an adverse cardiovascular phenome, using novel techniques (elastic net-PCA) to construct metabolic signatures of health linked to CVD outcome. Metabolites identified here specify known and novel pathways of metabolic dysfunction previously clinically implicated in older populations or mechanistically implicated in animal models (e.g., transcriptional regulation, BDNF, NO, renin-angiotensin). Metabolites could be decomposed into unique scores reflecting myocardial and vascular phenotypes that were divergent by sex and race (but not age). These composite measures of molecular metabolic health quantified in young adulthood offered significant prognostic value for future CVD beyond classical clinical risk factors at a nearly 20 year time horizon. This association was replicated in a separate population with nearly two decades of follow-up, with the greatest hazard of adverse CVD occurring referable to metabolic health observed in the youngest age range. These results provide evidence that precise aspects of metabolism rooted in underlying mechanisms, phenotypes and prognosis mark early alterations relevant to the pathogenesis of CVD in young adulthood, before traditional risk factors take hold.

This work builds on over two decades of investigation bridging metabolism and CVD. In seminal work from CARDIA and the Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth (PDAY) study, a standard CVD and metabolic risk score (composed of smoking, lipids, hypertension, obesity, dysglycemia) early in adulthood was associated with subclinical CVD by mid-life23, 40. Interestingly, the hazard of future subclinical CVD was highest with scores assessed earliest in adulthood, though most effect sizes (and discrimination) for mid-life CVD remained modest23. Previous seminal results in large cohorts suggest that metabolic dysfunction at a molecular level may occur before changes in insulin sensitivity, preceding the development of disease by decades12, and very recent studies support this concept41. Nevertheless, studies to elucidate early CVD propensity in young adults are scarce. Future CVD occurs in young adults who exhibit levels of clinically “standard” risk factors below current treatment thresholds3, observations that have motivated broad efforts to identify genetic and epigenetic risk factors to subset clinically actionable younger sub-populations. With regard to genetic risk, recent work suggests that—outside of extreme levels of a polygenic risk score—may not confer substantial risk across the general population42. The approach taken here (based on identifying metabolic features associated with widely accepted, imaging-based and clinical surrogates of CVD) identifies a metabolic fingerprint that likely integrates multiple dimensions of risk (genetic, epigenetic, environmental) when applied earlier in the life-course of CVD across two large populations. Furthermore, metabolism appears to be distinct from obesity in conferring risk (given modest correlations with BMI and independence from BMI in survival models). In addition, many of the metabolites identified appear modifiable with intervention, such as exercise (pantothenate, glutamate43) and diet (glutamine, taurine44, arginine45), highlighting the potential importance of clinical metabolic interventions to shift prognostic signatures of CVD early in adulthood. Collectively, these results demonstrate that while metabolism certainly remains prognostic across life, its association with CVD appears highest when quantified early in adulthood, before the cumulative toll of traditional risk factors ensues.

We also noted a difference in myocardial health score by race, without significant differences by race in how that score was related to CVD. Black Americans experience a higher rate of early heart failure (HF; before age 50 years) relative to whites46, linked to disparities in predisposing metabolic phenotypes (e.g., hypertension, diabetes)47, 48 and attendant subclinical cardiac remodeling49, 50. The current study provides molecular context for these epidemiologic observations, implicating a host of metabolic pathways in myocardial dysfunction and CVD. The underlying impetus behind changes in metabolism is likely complex, involving interaction between important environmental and metabolic factors (e.g., dietary patterns, physical activity51). In this context, studies that investigate how dietary factors and activity mediate the relationship between molecular profiles of subclinical heart disease and CVD are warranted. Though cross-cohort collaborative efforts may provide some opportunity to address these issues52, large multi-component studies of metabolism involving young Black adults before the onset of important cardiometabolic illnesses are warranted to confirm, clarify and extend these findings.

To our knowledge, this study represents the largest, biracial study of metabolism in young adults, where modern CVD risk prediction algorithms are not formally calibrated. Nevertheless, there are several limitations that merit mention. We selected a subsample of Year 7 within CARDIA (potential referral bias), though the selected subsample was similar to the overall CARDIA cohort attending Year 7. In addition, the associations with outcomes were externally validated in FHS. Additional efforts to address important features in early adulthood that may impact long-term risk (e.g., pregnancy and related complications, physical activity, diet, cardiorespiratory fitness) specifically focused on mediation represent an important future locus of intervention. Our validation cohort (FHS) was selected based on long-term follow-up for CVD, a large range of age (to test age-related interactions), and a similar metabolite profiling platform (Broad). While we did not observe effect modification by race, a focus on replication in young Black adults is an important goal to be addressed by ongoing efforts in cross-cohort collaborations and new studies. In addition, there is possibility of a healthy survivor bias in FHS, though we would anticipate that a survival bias (FHS participants surviving to older age as being “healthier”) would have augmented the impact of a “poorer” metabolic score on CVD outcome. In addition, we observed no meaningful association between age and the metabolic health scores. Finally, the future implications of these results on metabolic pathway discovery merit discussion. We identified both metabolites with known CVD association and less well studied metabolites, suggesting potential for mechanistic dissection. As with previous integrative studies of metabolism, functional studies, large collaborative efforts with varying metabolic exposures (e.g., exercise, diet), and integration with genetics (e.g., metabolite-based Mendelian randomization) are likely to provide greater context for our findings and opportunity for mechanistic discovery.

In conclusion, in a large group of white and Black young Americans, metabolic signatures of myocardial and vascular health obtained in young adulthood specify known and novel pathways of metabolic dysfunction relevant to CVD and are associated with long-term clinical CVD outcomes over two decades, with strongest association in young adulthood. Targeted efforts to include metabolic health in risk stratification to interrupt CVD at its earliest stage are warranted.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

What is new?

Alterations in metabolism are linked to cardiovascular disease and can occur early in life.

Most studies of molecular markers of metabolism involve older adults, where CVD predisposition may be “encoded” in traditional risk factors.

Here, we use high-dimensional metabolite profiling in a cohort of biracial young adults, demonstrating metabolite-based signatures of myocardial and vascular disease in young adults that are associated with cardiac events at >20 years later into mid-life.

These associations are reproduced in a separate cohort of adults across a broad age range, demonstrating the maximal impact of metabolite signatures in younger individuals.

What are the clinical implications?

These findings are clinically relevant in highlighting the importance of early metabolic pathways and interventions in forestalling CVD progression and support societal efforts to alter metabolism as a method to prevent CVD at an early stage.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the dedication of the CARDIA and FHS study participants without whom this research would not be possible. This manuscript has been reviewed by CARDIA for scientific content. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institutes of Health; or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

Dr. Murthy receives funding from the Melvin Rubenfire Professorship in Preventive Cardiology. Dr. Murthy and Dr. Shah are supported in part by grants from the National Institute on Aging (R01AG059729) and National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (R01HL136685) and the American Heart Association. Dr. Vasan is supported in part by the Evans Medical Foundation and the Jay and Louis Coffman Endowment from the Department of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA) is conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with the University of Alabama at Birmingham (HHSN268201800005I & HHSN268201800007I), Northwestern University (HHSN268201800003I), University of Minnesota (HHSN268201800006I), and Kaiser Foundation Research Institute (HHSN268201800004I). The Framingham Heart Study (FHS) acknowledges the support of contracts NO1-HC-25195, HHSN268201500001I and 75N92019D00031 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and grant R01DK081572 from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases for this research.

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Murthy owns stock in General Electric and Cardinal Health and stock options in Ionetix. He has received research grants and speaking honoraria from Siemens Medical Imaging and expert testimony fees on behalf of Jubilant Draximage. He has served on medical advisory boards for Ionetix and Curium. Dr. Shah has served as a consultant in the past 12 months for Myokardia (ongoing) and Best Doctors (ongoing), and has minor stock holdings in Gilead. Dr. Shah is a co-inventor on a patent for ex-RNAs signatures of cardiac remodeling.

Non-Standard Abbreviations

- CARDIA

Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults

- PCA

principal components analysis

- FHS

Framingham Heart Study

- PCE

pooled cohort equation

- CAC

coronary artery calcification

- AAC

abdominal aortic calcification

- MAPK

MAP kinase

- NO

nitric oxide

- cGMP

cyclic guanosine monophosphate

REFERENCES

- 1.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, Braun LT, de Ferranti S, Faiella-Tommasino J, Forman DE, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139:e1082–e1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strong JP, Malcom GT, McMahan CA, Tracy RE, Newman WP 3rd, Herderick EE and Cornhill JF. Prevalence and extent of atherosclerosis in adolescents and young adults: implications for prevention from the Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth Study. Jama. 1999;281:727–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartiala O, Magnussen CG, Kajander S, Knuuti J, Ukkonen H, Saraste A, Rinta-Kiikka I, Kainulainen S, Kahonen M, Hutri-Kahonen N, et al. Adolescence risk factors are predictive of coronary artery calcification at middle age: the cardiovascular risk in young Finns study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1364–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loria CM, Liu K, Lewis CE, Hulley SB, Sidney S, Schreiner PJ, Williams OD, Bild DE and Detrano R. Early adult risk factor levels and subsequent coronary artery calcification: the CARDIA Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:2013–2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ference BA, Bhatt DL, Catapano AL, Packard CJ, Graham I, Kaptoge S, Ference TB, Guo Q, Laufs U, Ruff CT, et al. Association of Genetic Variants Related to Combined Exposure to Lower Low-Density Lipoproteins and Lower Systolic Blood Pressure With Lifetime Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Jama. 2019;322:1381–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gooding HC, Ning H, Gillman MW, Shay C, Allen N, Goff DC Jr., Lloyd-Jones D and Chiuve S. Application of a Lifestyle-Based Tool to Estimate Premature Cardiovascular Disease Events in Young Adults: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. JAMA internal medicine. 2017;177:1354–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagenknecht LE, Perkins LL, Cutter GR, Sidney S, Burke GL, Manolio TA, Jacobs DR Jr., Liu KA, Friedman GD, Hughes GH, et al. Cigarette smoking behavior is strongly related to educational status: the CARDIA study. Preventive medicine. 1990;19:158–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dyer AR, Cutter GR, Liu KQ, Armstrong MA, Friedman GD, Hughes GH, Dolce JJ, Raczynski J, Burke G and Manolio T. Alcohol intake and blood pressure in young adults: the CARDIA Study. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1990;43:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bild DE, Jacobs DR Jr., Sidney S, Haskell WL, Anderssen N and Oberman A. Physical activity in young black and white women. The CARDIA Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1993;3:636–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sidney S, Jacobs DR Jr., Haskell WL, Armstrong MA, Dimicco A, Oberman A, Savage PJ, Slattery ML, Sternfeld B and Van Horn L. Comparison of two methods of assessing physical activity in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133:1231–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murthy VL, Abbasi SA, Siddique J, Colangelo LA, Reis J, Venkatesh BA, Carr JJ, Terry JG, Camhi SM, Jerosch-Herold M, et al. Transitions in Metabolic Risk and Long-Term Cardiovascular Health: Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2016;5:e003934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Cheng S, Rhee EP, McCabe E, Lewis GD, Fox CS, Jacques PF, Fernandez C, et al. Metabolite profiles and the risk of developing diabetes. Nature medicine. 2011;17:448–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abidi W, Nestoridi E, Feldman H, Stefater M, Clish C, Thompson CC and Stylopoulos N. Differential Metabolomic Signatures in Patients with Weight Regain and Sustained Weight Loss After Gastric Bypass Surgery: A Pilot Study. Dig Dis Sci 2020;65:1144–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang JH, Berkovitch SS, Iaconelli J, Watmuff B, Park H, Chattopadhyay S, McPhie D, Ongur D, Cohen BM, Clish CB, et al. Perturbational Profiling of Metabolites in Patient Fibroblasts Implicates alpha-Aminoadipate as a Potential Biomarker for Bipolar Disorder. Mol Neuropsychiatry 2016;2:97–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy D, Garrison RJ, Savage DD, Kannel WB and Castelli WP. Left ventricular mass and incidence of coronary heart disease in an elderly cohort. The Framingham Heart Study. Ann Intern Med 1989;110:101–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy D, Garrison RJ, Savage DD, Kannel WB and Castelli WP. Prognostic implications of echocardiographically determined left ventricular mass in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1561–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carr JJ, Jacobs DR Jr., Terry JG, Shay CM, Sidney S, Liu K, Schreiner PJ, Lewis CE, Shikany JM, Reis JP, et al. Association of Coronary Artery Calcium in Adults Aged 32 to 46 Years With Incident Coronary Heart Disease and Death. JAMA cardiology. 2017;2:391–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah RV, Yeri AS, Murthy VL, Massaro JM, D’Agostino R Sr., Freedman JE, Long MT, Fox CS, Das S, Benjamin EJ, et al. Association of Multiorgan Computed Tomographic Phenomap With Adverse Cardiovascular Health Outcomes: The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA cardiology. 2017;2:1236–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah RV, Murthy VL, Colangelo LA, Reis J, Venkatesh BA, Sharma R, Abbasi SA, Goff DC Jr., Carr JJ, Rana JS, et al. Association of Fitness in Young Adulthood With Survival and Cardiovascular Risk: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. JAMA internal medicine. 2016;176:87–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brittain EL, Nwabuo C, Xu M, Gupta DK, Hemnes AR, Moreira HT, De Vasconcellos HD, Terry JG, Carr JJ and Lima JA. Echocardiographic Pulmonary Artery Systolic Pressure in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study: Associations With Race and Metabolic Dysregulation. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2017;6:e005111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kishi S, Reis JP, Venkatesh BA, Gidding SS, Armstrong AC, Jacobs DR Jr., Sidney S, Wu CO, Cook NL, Lewis CE, et al. Race-ethnic and sex differences in left ventricular structure and function: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2015;4:e001264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kishi S, Armstrong AC, Gidding SS, Colangelo LA, Venkatesh BA, Jacobs DR Jr., Carr JJ, Terry JG, Liu K, Goff DC Jr., et al. Association of obesity in early adulthood and middle age with incipient left ventricular dysfunction and structural remodeling: the CARDIA study (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults). JACC Heart failure. 2014;2:500–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gidding SS, Rana JS, Prendergast C, McGill H, Carr JJ, Liu K, Colangelo LA, Loria CM, Lima J, Terry JG, et al. Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth (PDAY) Risk Score in Young Adults Predicts Coronary Artery and Abdominal Aorta Calcium in Middle Age: The CARDIA Study. Circulation. 2016;133:139–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Quigley J, Xu R and Stare J. Explained randomness in proportional hazards models. Stat Med 2005;24:479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB Sr. and Steyerberg EW. Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Stat Med 2011;30:11–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu X, Zheng Y, Guasch-Ferre M, Ruiz-Canela M, Toledo E, Clish C, Liang L, Razquin C, Corella D, Estruch R, et al. High plasma glutamate and low glutamine-to-glutamate ratio are associated with type 2 diabetes: Case-cohort study within the PREDIMED trial. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2019;29:1040–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng Y, Hu FB, Ruiz-Canela M, Clish CB, Dennis C, Salas-Salvado J, Hruby A, Liang L, Toledo E, Corella D, et al. Metabolites of Glutamate Metabolism Are Associated With Incident Cardiovascular Events in the PREDIMED PREvencion con DIeta MEDiterranea (PREDIMED) Trial. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2016;5:e003755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng S, Rhee EP, Larson MG, Lewis GD, McCabe EL, Shen D, Palma MJ, Roberts LD, Dejam A, Souza AL, et al. Metabolite profiling identifies pathways associated with metabolic risk in humans. Circulation. 2012;125:2222–2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magnusson M, Lewis GD, Ericson U, Orho-Melander M, Hedblad B, Engstrom G, Ostling G, Clish C, Wang TJ, Gerszten RE, et al. A diabetes-predictive amino acid score and future cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1982–1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Sullivan JF, Morningstar JE, Yang Q, Zheng B, Gao Y, Jeanfavre S, Scott J, Fernandez C, Zheng H, O’Connor S, et al. Dimethylguanidino valeric acid is a marker of liver fat and predicts diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:4394–4402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ottosson F, Ericson U, Almgren P, Smith E, Brunkwall L, Hellstrand S, Nilsson PM, Orho-Melander M, Fernandez C and Melander O. Dimethylguanidino Valerate: A Lifestyle-Related Metabolite Associated With Future Coronary Artery Disease and Cardiovascular Mortality. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2019;8:e012846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robbins JM, Herzig M, Morningstar J, Sarzynski MA, Cruz DE, Wang TJ, Gao Y, Wilson JG, Bouchard C, Rankinen T, et al. Association of Dimethylguanidino Valeric Acid With Partial Resistance to Metabolic Health Benefits of Regular Exercise. JAMA cardiology. 2019;4:636–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang XC, Paultre F, Pearson TA, Reed RG, Francis CK, Lin M, Berglund L and Tall AR. Plasma sphingomyelin level as a risk factor for coronary artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2000;20:2614–2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kikas P, Chalikias G and Tziakas D. Cardiovascular Implications of Sphingomyelin Presence in Biological Membranes. Eur Cardiol 2018;13:42–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feig DI, Kang DH and Johnson RJ. Uric acid and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1811–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang R, Babyak MA, Brummett BH, Hauser ER, Shah SH, Becker RC, Siegler IC, Singh A, Haynes C, Chryst-Ladd M, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor rs6265 (Val66Met) polymorphism is associated with disease severity and incidence of cardiovascular events in a patient cohort. Am Heart J. 2017;190:40–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bahls M, Konemann S, Markus MRP, Wenzel K, Friedrich N, Nauck M, Volzke H, Steveling A, Janowitz D, Grabe HJ, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is related with adverse cardiac remodeling and high NTproBNP. Scientific reports. 2019;9:15421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kermani P and Hempstead B. BDNF Actions in the Cardiovascular System: Roles in Development, Adulthood and Response to Injury. Frontiers in physiology. 2019;10:455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Enos WF, Holmes RH and Beyer J. Coronary disease among United States soldiers killed in action in Korea; preliminary report. J Am Med Assoc 1953;152:1090–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gidding SS, McMahan CA, McGill HC, Colangelo LA, Schreiner PJ, Williams OD and Liu K. Prediction of coronary artery calcium in young adults using the Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth (PDAY) risk score: the CARDIA study. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:2341–2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahola-Olli AV, Mustelin L, Kalimeri M, Kettunen J, Jokelainen J, Auvinen J, Puukka K, Havulinna AS, Lehtimaki T, Kahonen M, et al. Circulating metabolites and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study of 11,896 young adults from four Finnish cohorts. Diabetologia 2019;62:2298–2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mosley JD, Gupta DK, Tan J, Yao J, Wells QS, Shaffer CM, Kundu S, Robinson-Cohen C, Psaty BM, Rich SS, et al. Predictive Accuracy of a Polygenic Risk Score Compared With a Clinical Risk Score for Incident Coronary Heart Disease. Jama 2020;323:627–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lewis GD, Farrell L, Wood MJ, Martinovic M, Arany Z, Rowe GC, Souza A, Cheng S, McCabe EL, Yang E, et al. Metabolic signatures of exercise in human plasma. Science translational medicine. 2010;2:33ra37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun Q, Wang B, Li Y, Sun F, Li P, Xia W, Zhou X, Li Q, Wang X, Chen J, et al. Taurine Supplementation Lowers Blood Pressure and Improves Vascular Function in Prehypertension: Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Hypertension 2016;67:541–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Creager MA, Gallagher SJ, Girerd XJ, Coleman SM, Dzau VJ and Cooke JP. L-arginine improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation in hypercholesterolemic humans. J Clin Invest 1992;90:1248–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bibbins-Domingo K, Pletcher MJ, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Gardin JM, Arynchyn A, Lewis CE, Williams OD and Hulley SB. Racial differences in incident heart failure among young adults. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1179–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bahrami H, Kronmal R, Bluemke DA, Olson J, Shea S, Liu K, Burke GL and Lima JA. Differences in the incidence of congestive heart failure by ethnicity: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:2138–2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loehr LR, Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Folsom AR and Chambless LE. Heart failure incidence and survival (from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study). Am J Cardiol 2008;101:1016–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spahillari A, Talegawkar S, Correa A, Carr JJ, Terry JG, Lima J, Freedman JE, Das S, Kociol R, de Ferranti S, et al. Ideal Cardiovascular Health, Cardiovascular Remodeling, and Heart Failure in Blacks: The Jackson Heart Study. Circ Heart Fail 2017;10:e003682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lewis AA, Ayers CR, Selvin E, Neeland I, Ballantyne CM, Nambi V, Pandey A, Powell-Wiley TM, Drazner MH, Carnethon MR, et al. Racial Differences in Malignant Left Ventricular Hypertrophy and Incidence of Heart Failure: A Multicohort Study. Circulation. 2020;141:957–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Djousse L, Petrone AB, Blackshear C, Griswold M, Harman JL, Clark CR, Talegawkar S, Hickson DA, Gaziano JM, Dubbert PM, et al. Prevalence and changes over time of ideal cardiovascular health metrics among African-Americans: the Jackson Heart Study. Preventive medicine. 2015;74:111–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu B, Zanetti KA, Temprosa M, Albanes D, Appel N, Barrera CB, Ben-Shlomo Y, Boerwinkle E, Casas JP, Clish C, et al. The Consortium of Metabolomics Studies (COMETS): Metabolomics in 47 Prospective Cohort Studies. Am J Epidemiol 2019;188:991–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cirulli ET, Guo L, Leon Swisher C, Shah N, Huang L, Napier LA, Kirkness EF, Spector TD, Caskey CT, Thorens B, et al. Profound Perturbation of the Metabolome in Obesity Is Associated with Health Risk. Cell metabolism. 2019;29:488–500 e482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roef GL, Taes YE, Kaufman JM, Van Daele CM, De Buyzere ML, Gillebert TC and Rietzschel ER. Thyroid hormone levels within reference range are associated with heart rate, cardiac structure, and function in middle-aged men and women. Thyroid. 2013;23:947–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ottosson F, Smith E, Melander O and Fernandez C. Altered Asparagine and Glutamate Homeostasis Precede Coronary Artery Disease and Type 2 Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018;103:3060–3069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.He F, Wu C, Li P, Li N, Zhang D, Zhu Q, Ren W and Peng Y. Functions and Signaling Pathways of Amino Acids in Intestinal Inflammation. BioMed research international. 2018;2018:9171905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Walford GA, Ma Y, Clish C, Florez JC, Wang TJ, Gerszten RE and Diabetes Prevention Program Research G. Metabolite profiles of diabetes incidence and intervention response in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes. 2016;65:1424–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guasch-Ferre M, Hu FB, Ruiz-Canela M, Bullo M, Toledo E, Wang DD, Corella D, Gomez-Gracia E, Fiol M, Estruch R, et al. Plasma Metabolites From Choline Pathway and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in the PREDIMED (Prevention With Mediterranean Diet) Study. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2017;6:e006524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wurtz P, Havulinna AS, Soininen P, Tynkkynen T, Prieto-Merino D, Tillin T, Ghorbani A, Artati A, Wang Q, Tiainen M, et al. Metabolite profiling and cardiovascular event risk: a prospective study of 3 population-based cohorts. Circulation. 2015;131:774–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marz W, Meinitzer A, Drechsler C, Pilz S, Krane V, Kleber ME, Fischer J, Winkelmann BR, Bohm BO, Ritz E, et al. Homoarginine, cardiovascular risk, and mortality. Circulation. 2010;122:967–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kishimoto Y, Kondo K and Momiyama Y. The Protective Role of Heme Oxygenase-1 in Atherosclerotic Diseases. International journal of molecular sciences. 2019;20:3628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McCarty MF and DiNicolantonio JJ. The cardiometabolic benefits of glycine: Is glycine an ‘antidote’ to dietary fructose? Open Heart. 2014;1:e000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ding Y, Svingen GF, Pedersen ER, Gregory JF, Ueland PM, Tell GS and Nygard OK. Plasma Glycine and Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Patients With Suspected Stable Angina Pectoris. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2015;5:e002621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Diaz-Flores M, Cruz M, Duran-Reyes G, Munguia-Miranda C, Loza-Rodriguez H, Pulido-Casas E, Torres-Ramirez N, Gaja-Rodriguez O, Kumate J, Baiza-Gutman LA, et al. Oral supplementation with glycine reduces oxidative stress in patients with metabolic syndrome, improving their systolic blood pressure. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2013;91:855–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maia AR, Batista TM, Victorio JA, Clerici SP, Delbin MA, Carneiro EM and Davel AP. Taurine supplementation reduces blood pressure and prevents endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress in post-weaning protein-restricted rats. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li T, Zhang Z, Kolwicz SC Jr., Abell L, Roe ND, Kim M, Zhou B, Cao Y, Ritterhoff J, Gu H, et al. Defective Branched-Chain Amino Acid Catabolism Disrupts Glucose Metabolism and Sensitizes the Heart to Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Cell metabolism. 2017;25:374–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sun H, Olson KC, Gao C, Prosdocimo DA, Zhou M, Wang Z, Jeyaraj D, Youn JY, Ren S, Liu Y, et al. Catabolic Defect of Branched-Chain Amino Acids Promotes Heart Failure. Circulation. 2016;133:2038–2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koeth RA, Lam-Galvez BR, Kirsop J, Wang Z, Levison BS, Gu X, Copeland MF, Bartlett D, Cody DB, Dai HJ, et al. l-Carnitine in omnivorous diets induces an atherogenic gut microbial pathway in humans. J Clin Invest 2019;129:373–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Prasad M, Matteson EL, Herrmann J, Gulati R, Rihal CS, Lerman LO and Lerman A. Uric Acid Is Associated With Inflammation, Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction, and Adverse Outcomes in Postmenopausal Women. Hypertension. 2017;69:236–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Holmes E, Loo RL, Stamler J, Bictash M, Yap IK, Chan Q, Ebbels T, De Iorio M, Brown IJ, Veselkov KA, et al. Human metabolic phenotype diversity and its association with diet and blood pressure. Nature. 2008;453:396–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Simard T, Jung R, Labinaz A, Faraz MA, Ramirez FD, Di Santo P, Perry-Nguyen D, Pitcher I, Motazedian P, Gaudet C, et al. Evaluation of Plasma Adenosine as a Marker of Cardiovascular Risk: Analytical and Biological Considerations. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2019;8:e012228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yu E, Ruiz-Canela M, Guasch-Ferre M, Zheng Y, Toledo E, Clish CB, Salas-Salvado J, Liang L, Wang DD, Corella D, et al. Increases in Plasma Tryptophan Are Inversely Associated with Incident Cardiovascular Disease in the Prevencion con Dieta Mediterranea (PREDIMED) Study. The Journal of nutrition. 2017;147:314–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yu B, Heiss G, Alexander D, Grams ME and Boerwinkle E. Associations Between the Serum Metabolome and All-Cause Mortality Among African Americans in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183:650–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Svingen GF, Ueland PM, Pedersen EK, Schartum-Hansen H, Seifert R, Ebbing M, Loland KH, Tell GS and Nygard O. Plasma dimethylglycine and risk of incident acute myocardial infarction in patients with stable angina pectoris. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2013;33:2041–2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang R, Shen Y, Zhou L, Sangwung P, Fujioka H, Zhang L and Liao X. Short-term administration of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide preserves cardiac mitochondrial homeostasis and prevents heart failure. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2017;112:64–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Diguet N, Trammell SAJ, Tannous C, Deloux R, Piquereau J, Mougenot N, Gouge A, Gressette M, Manoury B, Blanc J, et al. Nicotinamide Riboside Preserves Cardiac Function in a Mouse Model of Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2018;137:2256–2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.