Abstract

Background/Aim: The objective of the study was analysis of risk factors associated with outcome of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) in infants in a single-center study. Patients and Methods: All consecutive infants hospitalized for NEC over a period of 6 years were retrospectively analyzed for clinical course, infections, treatment and outcome. Results: Out of 76 patients, surgical management was applied in 56 (53 exploratory laparotomy, three initial peritoneal drain placement) and in 20 there was only a conservative approach. Segmental intestinal resection was performed in 41 patients. Survival from NEC in our cohort was 79%. We found that independent adverse risk factors of outcome of newborns and infants with NEC were gut perforation, infection, abdominal wall erythema, and development of acute kidney injury. Conclusion: We underline the value of both surgical and conservative approach with careful management in this cohort of patients.

Keywords: Newborns, infants, necrotizing enterocolitis, minimally invasive surgery

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is a complex predominantly intestinal inflammatory disorder affecting preterm infants, and the major cause of morbidity and mortality in this age group. It is one of the most common gastrointestinal (GI) emergencies in the neonatal period. NEC has multifactorial etiology and is characterized by a variable degree of intestinal gangrene. Population-based studies have estimated the incidence of NEC between 0.72-1.8 per 1,000 live births (1). Most neonates diagnosed with NEC are at the age of less than 32 weeks of gestation, particularly in the case of extremely low birth weight infants weighing less than 1,000 g, while a decline in incidence occurs after 35 weeks of gestation (2).

Well-known risk factors for development of NEC include prematurity and bacterial colonization of the gastrointestinal tract (3,4). With increasing survival of extremely premature infants, the number of neonates at risk for developing NEC continues to rise. Clinical features of NEC include the presence of physiological and metabolic instability, abdominal distention, and feeding intolerance (5). Disease severity is characterized by clinical and radiographic findings, known as the Bell staging system (6).

The objective of this study was the analysis of the clinical course and risk factors for outcomes of infants with NEC in a single-center study.

Patients and Methods

Design of the study. A total of 76 consecutive infants including 43 (56.6%) males, and 33 (43.4%) females with NEC hospitalized at the Department over a period of 6 years were retrospectively analyzed for clinical course, infections, treatment and outcome. The study was approved by Collegium Medicum in Bydgoszcz Bioethical Committee No 465/2011.

NEC diagnosis and classification. NEC was diagnosed on the basis of clinical, laboratory (e.g. white blood cell count, neutrophil count, platelet count, blood gas balance, C-reactive protein) and radiological (e.g. ultrasound, X-ray) signs and symptoms. Patients admitted to the Department were treated surgically or conservatively. Surgical treatment was based on laparotomy or peritoneal drainage. The newborns were classified according to Bell’s (6-8) or modified Tepas criteria (9). NEC classification in Bell’s criteria with Walsh-Kliegman modification (6-8) included three stages: Stage I: suspicion of NEC (A, occult GI bleeding; B, GI bleeding); stage II: diagnosed NEC (A, mild; B, intermediate); stage III: advanced NEC (A, without perforation; B, with perforation). Additionally, we classified patients with NEC according to Tepas criteria of NEC natural history (9) with our own modification, which included four grades: Grade 1: no necrosis, no perforation; grade 2: perforation but without metabolic or hematologic derangements; grade 3: severe clinical symptoms with coexisting metabolic and hematological derangements (thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, left shift of segmented neutrophils, metabolic acidosis, hyponatremia, bacteremia, or hypotension) together with free intraperitoneal air; grade 4: severe clinical symptoms with coexisting metabolic and hematological derangements, without free intraperitoneal air.

Statistical analysis. Categorical variables were compared by the chi-square test or Fisher exact test, with odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI); and non-categorical variables by the Mann-Whitney test. The primary endpoint of the study was overall survival (OS). The survival curves were determined by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared with log-rank test. Risk factors analysis for surgical treatment were in univariate analysis were by uni- and multivariate logistic regression. Risk factor analysis for survival was performed using a univariate Cox model. Factors significant in univariate model were analyzed in multivariate Cox model. The results of the multivariate analysis are presented by hazard ratio (HR) with a 95% CI. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analysis was performed using the statistical package SPSS 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

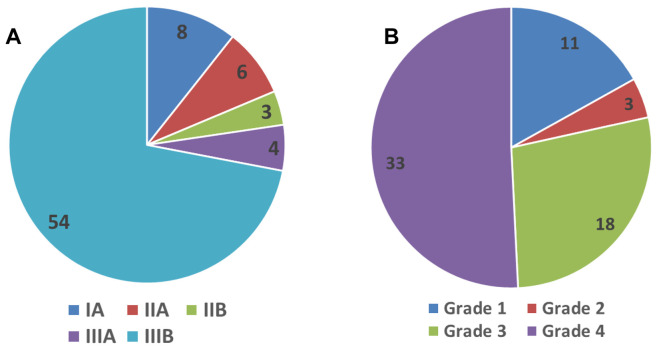

Demographics. The median gestational birth age was 29 weeks (range=23-41 weeks), median weight 1095 g (range=570-4,620 g), median Apgar score 5 (range=1-10), and median age at admission 12 days (range=1-3 days). The distribution of patients according to Bell’s and modified Tepas classifications are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Frequency distribution of patients according to Bell’s classification (6-8) (A) and modified Tepas classification (9) (B).

Microbial colonization. On admission, colonization was diagnosed in 53 patients, including bacterial etiology in 52 patients (Gram-positive in 35, and Gram-negative in 17), and fungal etiology in eight patients. Gram-positive strains detected included: methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococcus in nine, Staphyococcus aureus in four, Staphyococcus spp in eight, Staphyococcus epidermidis in two, Staphyococcus haemolyticus in seven, Streptococcus pnuemoniae in one, Streptococcus viridans in two, Enterococcus faecalis in seven, and Enteroccus faecium in seven. Gram-negative strains included: Klebsiella pneumoniae in five, Klebsiella oxytoca in four, Escherichia coli in 14, Enterobacter cloacae in three, Serratia marcescens in one, Citrobacter spp in two, Corynebacterium spp in two, Pseudomonas aeruginosa in one, Acinetobacter baumanii in 2, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in four. Fungal colonization included: Candida albicans in six, Candida guilliermondii in one, and Candida faringe in one.

Infectious complications. Infections developed in 51 patients, including sepsis in 48 patients, microbiologically documented infection in 28 patients, and clinically documented infection in 21 patients. Bacterial etiology of infection was diagnosed in 26 patients (Gram-positive in 14, and Gram-negative in 12), and fungal infection in seven patients. Infection with Gram-positive strains included: Staphylococcus epidermidis in nine, Staphylococcus haemolyticus in three, Streptococcus pneumoniae in one, and Enteroccus faecium in one. Infection with Gram-negative strains included: Klebsiella pneumoniae in two, Escherichia coli in four, Enterobacter cloacae in two, Aeromonas spp in one, Acinetobacter baumanii in two, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in two. Infections with fungi included: Candida albicans in five, Candida guilliermondii in one, Candida faringe in one, and Candida pelicula in one.

Surgical treatment. Out of 76 patients, 56 were treated surgically (53 exploratory laparoscopy, three peritoneal drain placement) and 20 conservatively only. Intestine resection with concomitant creation of enterostomy was performed in 41 patients, at a median of 12 days (range=1-45 day). Median length of resected intestine was 10 cm (range=3-72 cm). significantly risk factors for surgical treatment in univariate analysis were: Grade 3-4 in modified Tepas classification (HR=5.0, 95% CI=1.6-16, p=0.006), stage III in classification by Bell (HR=28, 95% CI=6.9->100, p<0.001), and perforation (HR=9.9, 95% CI=3.0-32, p<0.001), while birth weight <1,000 g was a factor reducing the decision on surgical treatment (HR=0.20, 95% CI=0.1-0.7, p=0.007). The only risk factor remaining significant for surgical treatment in multivariate analysis was stage III in classification by Bell (HR=40, 95% CI=7.4->100, p<0.001).

Antibiotic utilization. All patients were treated with antibiotics, including: meropenem in 39, imipenem in 13 (carbapenems in 49), vancomycin in 45, teicoplanin in 8, linezolid in one, piperacillin-tazobactam in 12, cephalosporines III/IV generation in 10 (ceftazidime in eight, ceftriaxone in two, cefepime in one), metronidazole in 60, amikacin in 13, netilmicin in 13, gentamicin in one, amoxicillin with clavulanate in 12, cefuroxime in one, cefoperazon with sulbactam in three, ciprofloxacin in three, ampicillin in two, and colistin in two. Overall, 66 patients were administered antifungals, including fluconazole in 61, amphotericin B in three, voriconazole in one, and anidulafungin in one.

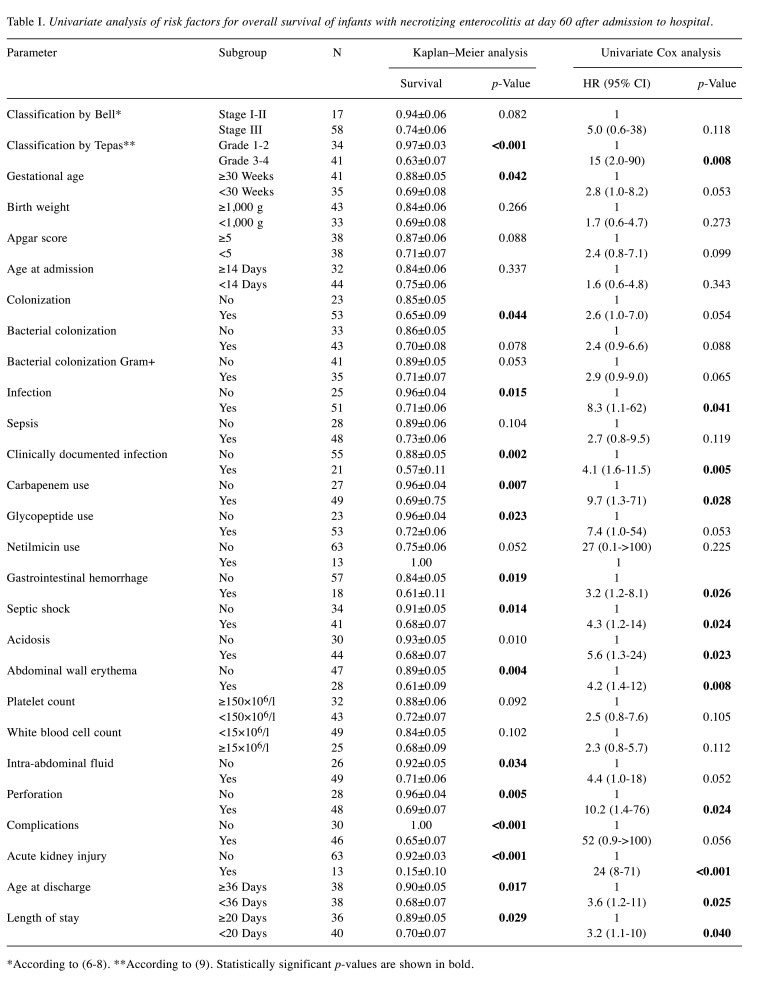

Univariate analysis of risk factors for overall survival. Overall, 16 (21%) patients died, at a median of 16 days (range=1-35 days) after admission to the Department. In univariate analysis, the following risk factors significantly contributed to adverse outcome: Grade 3/4 in modified Tepas classification, infection, use of carbapenems, use of glycopeptides, GI hemorrhage, septic shock, acidosis, abdominal wall erythema, intestine perforation, acute kidney injury, age at discharge less than 36 days, and length of hospital stay less than 20 days (Table I).

Table I. Univariate analysis of risk factors for overall survival of infants with necrotizing enterocolitis at day 60 after admission to hospital.

*According to (6-8). **According to (9). Statistically significant p-values are shown in bold

Apart from the parameters shown in Table I, also sex, mode of delivery (cesarean section), fungal colonization, Gram-negative bacterial colonization, microbiologically documented infections, specific bacterial strain, other laboratory and radiographic findings, as well as the use of any other antibiotic, had no influence on survival.

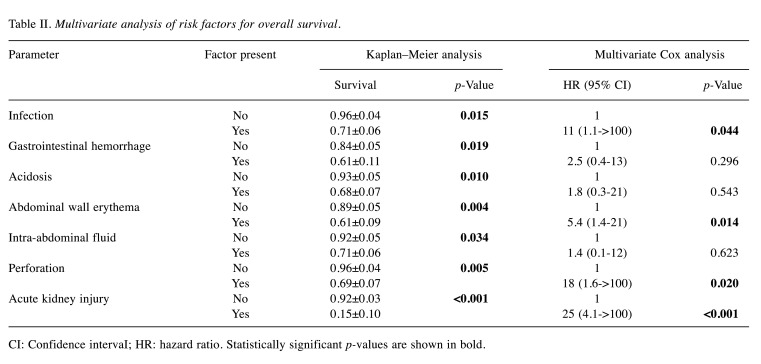

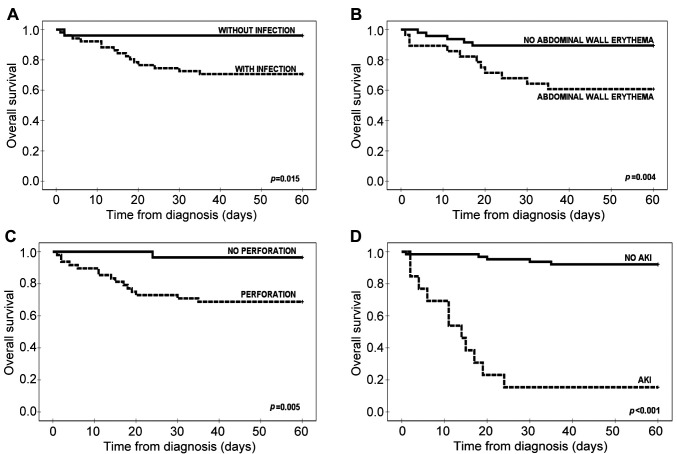

Multivariate analysis of risk factors for OS. The following independent factors, significant in univariate Cox analysis were included in the multivariate analysis: Infection, clinically documented infection, GI hemorrhage. septic shock, acidosis, abdominal wall erythema, intra-abdominal fluid, perforation, and acute kidney injury (Table II, Figure 2). On the other hand, the following factors were considered dependent on others: Modified Tepas classification, carbapenem use, age at discharge, and length of stay.

Table II. Multivariate analysis of risk factors for overall survival.

CI: Confidence intervaI; HR: hazard ratio. Statistically significant p-values are shown in bold

Figure 2. Overall survival with respect to concomitant infection (A), abdominal wall rythema (B), perforation (C) and acute kidney injury (AKI) (D).

Four independent factors significantly increased the risk of death due to NEC: Gut perforation, infection, abdominal wall erythema, and the development of acute kidney injury.

Discussion

The major finding of this study was determination of four independent adverse risk factors for outcome of newborns and infants with NEC, namely gut perforation, infection, abdominal wall erythema, and development of acute kidney injury.

Most patients included in the study were treated surgically either by exploratory laparotomy or with peritoneal drainage. In multivariate analysis, we showed that stage III in classification by Bell including perforation was the strongest factor influencing the decision of surgical treatment, while birth weight <1,000 g was the factor determining an initial conservative approach. Lower birth weight is a well-known factor associated with a higher frequency and greater severity of disease (10,11).

A number of laboratory and radiographic parameters confirmed adverse values of parameters assessing clinical status, and those confirming gut perforation have the highest value in selection of therapeutic approach and outcome of NEC. Obviously, a newborn’s death due to NEC is associated with severe clinical signs, laboratory parameters (leukocytosis, high level of C-reactive protein, metabolic acidosis) and radiological signs (no gas in the digestive tract). Perforation of the GI tract is usually followed by metabolic acidosis and typical radiological signs (free echogenic fluid in peritoneum and free gas in the abdomen). The same symptoms might develop in the case of post-surgical complications, such as acute kidney injury, which is frequently associated with the severity of enterocolitis (12). We also found that abdominal wall erythema was a relatively frequent symptom in our cohort, and had an adverse prognostic value. This phenomenon is rarely described in the literature, and it might be included in symptoms of abdominal distension (13).

In our cohort, a classic surgical treatment of NEC was applied: Resection of the necrotic bowel segment together with temporary proximal enterostomy creation. Nowadays several options for surgical treatment are proposed, depending mainly on the extent of necrosis and the patient’s general status (14,15). In an experimental model, it has been shown that laparoscopy has acceptable levels of agreement with laparotomy in NEC lesions of both the colon and the small intestine (16). There is still an open question of the use of minimally invasive surgery in neonates and small infants (14-16).

We previously showed that in case of congenital abdominal cystic lesions, a laparoscopically assisted minimal-access approach resulted in minimal risk of complications and complete recovery in all patients (17). On the other hand, a completely different approach was necessary for patients with Hirschsprung’s disease (18).

This study has some limitations. Apart from its retrospective design and long-term inclusion as a single-center study, we also did not analyze factors which may have contributed to the development of NEC, including the general care of newborns, such as antenatal corticosteroid use, delayed enteral feeding, human milk feeding, and pre- or probiotic administration (19). On the other hand, we analyzed a large number of risk factors, including clinical classifications, clinical signs and symptoms, laboratory and imaging parameters both in diagnosis of NEC and in the selection of treatment approach; however, no other independent factors were found which contributed to OS. The use of specific antibiotics, including carbapenems and glycopeptides, was bound to worsen survival, however, this was because of severe infection which required these ‘reference’ antibiotics and not any negative impact of the antibiotics themselves.

In conclusion, survival from NEC in our cohort was 79%. We found that independent adverse risk factors of outcome of NEC in newborns and infants were gut perforation, systemic infection, abdominal wall erythema, and the development of acute kidney injury. We underline the value of both surgical and conservative approach with careful management in this cohort of patients. The role of minimally invasive surgery in NEC might be a question of future research.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose in regard to this study.

Authors’ Contributions

PG: Concept/design, data analysis/interpretation, writing article; PG, MC, and JS: data collection, data analysis/interpretation; PG and JS: critical revision of article, approval of article.

References

- 1.Dominguez KM, Moss RL. Necrotizing enterocolitis. Ashcraft’s Pediatric Surgery Sixth Edition. London, Elsevier-Saunders. 2014:454–467. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel RM, Knezevic A, Shenvi N, Hinkes M, Keene S, Roback JD, Easley KA, Josephson CD. Association of red blood cell transfusion, anemia, and necrotizing enterocolitis in very low-birth-weight infants. JAMA. 2016;315(9):889–897. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sjoberg Bexelius T, Ahle M, Elfvin A, Bjorling O, Ludvigsson JF, Andersson RE. Intestinal failure after necrotising enterocolitis: Incidence and risk factors in a Swedish population-based longitudinal study. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2018;2(1):e000316. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2018-000316eCollection2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han SM, Hong CR, Knell J, Edwards EM, Morrow KA, Soll RF, Modi BP, Horbar JD, Jaksic T. Trends in incidence and outcomes of necrotizing enterocolitis over the last 12 years: A multicenter cohort analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2020;55(6):998–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2020.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heida FH, Stolwijk L, Loos MH, van den Ende SJ, Onland W, van den Dungen FA, Kooi EM, Bos AF, Hulscher JB, Bakx R. Increased incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in the Netherlands after implementation of the new Dutch guideline for active treatment in extremely preterm infants: Results from three academic referral centers. J Pediatr Surg. 2017;52(2):273–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell MJ, Ternberg JL, Feigin RD, Keating JP, Marshall R, Barton L, Brotherton T. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Ann Surg. 1978;187(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197801000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell MJ. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. N Engl J Med. 1978;298(5):281–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh MC, Kliegman RM. Necrotizing enterocolitis: Treatment based on staging criteria. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1986;33(1):179–201. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)34975-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tepas JJ 3rd, Sharma R, Hudak ML, Garrison RD, Pieper P. Coming full circle: An evidence-based definition of the timing and type of surgical management of very low-birth-weight (<1,000 g) infants with signs of acute intestinal perforation. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(2):418–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang ZL, An Y, He Y, Hu XY, Guo L, Li QY, Liu L, Li LQ. Risk factors of necrotizing enterocolitis in neonates with sepsis: A retrospective case–control study. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2020;34:2058738420963818. doi: 10.1177/2058738420963818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quiroz HJ, Rao K, Brady AC, Hogan AR, Thorson CM, Perez EA, Neville HL, Sola JE. Protocol-driven surgical care of necrotizing enterocolitis and spontaneous intestinal perforation. J Surg Res. 2020;255:396–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2020.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanchez C, Garcia MA, Valdes BD. Acute kidney injury in newborns with necrotizing enterocolitis: Risk factors and mortality. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2019;76(5):210–214. doi: 10.24875/BMHIM.19000044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meister AL, Doheny KK, Travagli RA. Necrotizing enterocolitis: It’s not all in the gut. Exp Biol Med. 2020;245(2):85–95. doi: 10.1177/1535370219891971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith J, Thyoka M. What role does laparoscopy play in the diagnosis and immediate treatment of infants with necrotizing enterocolitis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2013;23(4):397–401. doi: 10.1089/lap.2012.0482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galazka P, Czyzewski K, Marjanska A, Daniluk-Matras I, Styczynski J. Minimally invasive surgery in pediatric oncology: Proposal of guidelines. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(11):5853–5859. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knudsen KBK, Thorup J, Thymann T, Strandby R, Nerup N, Achiam MP, Lauritsen T, Svendsen LB, Buelund L, Sangild PT, Ifaoui IBR. Laparoscopy to assist surgical decisions related to necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm neonates. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2020;30(1):64–69. doi: 10.1089/lap.2018.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galazka P, Redloch K, Kroczek K, Styczynski J. Minimally invasive surgery for congenital abdominal cystic lesions in newborns and infants. In Vivo. 2020;34(3):1215–1221. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galazka P, Szylberg L, Bodnar M, Styczynski J, Marszalek A. Diagnostic algorithm in Hirschsprung’s disease: Focus on immunohistochemistry markers. In Vivo. 2020;34(3):1355–1359. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang B, Xiu W, Dai Y, Yang C. Protective effects of different doses of human milk on neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Medicine. 2020;99(37):e22166. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000022166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]