Abstract

Cells produce cytoplasmic vesicles to facilitate the processing and transport of RNAs, proteins, and other signaling molecules among intracellular organelles. Moreover, most cells release a range of extracellular vesicles (EVs) that mediate intercellular communication in both physiological and pathological settings. In addition to a better understanding of their biological functions, the diagnostic and therapeutic prospects of EVs, particularly the nano-sized small EVs (sEVs, exosomes), are currently being rigorously pursued. While EVs and viruses such as retroviruses might have evolved independently, they share a number of similar characteristics, including biogenesis pathways, size distribution, cargo, and cell-targeting mechanisms. The interplay of EVs with viruses has profound effects on viral replication and infectivity. Our research indicates that sEVs, produced by primary human trophoblasts, can endow other non-placental cell types with antiviral response. Better insights into the interaction of EVs with viruses may illuminate new ways to attenuate viral infections during pregnancy, and perhaps develop new antiviral therapeutics to protect the feto-placental unit during critical times of human development.

Keywords: Placenta, trophoblast, extracellular vesicles, viruses, microRNA

Introduction

Extracellular vesicles (EVs), existing in the plasma, urine, and likely in all biofluids1,2, influence a variety of physiological and pathological processes, such as aging3, neutralization of bacterial toxins4, viral infection5–7, immune response8,9, and tumorigenesis.10,11 EV subtypes and function are defined by their size, surface molecules, release mechanisms, and cargo12, including proteins; RNAs such as microRNAs (miRNAs)13,14, long non-coding RNAs15, and transfer RNAs;16 and other bioactive molecules. The spectrum of EV types includes, in order of decreasing size, tumor cell–derived oncosomes17,18 (1,000~10,000 nm), apoptotic blebs (ABs, 100~5,000 nm), microvesicles19 (MVs, 100~1,000 nm), and exosomes20,21 (50~150 nm). Other, less-defined EVs include amphisoms, arrestin-domain-containing protein 1 (ARRDC1)-mediated microvesicles (ARMM), non-classical MVs and exosomes, and the large macrolets.21–24 Other than obvious size differences among EV subpopulations, exosomes are notably distinct from other EVs as they are formed by cellular endocytic pathways, whereas oncosomes, ABs, and MVs are directly shed from the plasma membrane. Recently, by using asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation, a new type of non-vesicular nanoparticle, termed exomeres (30~50 nm), was identified within exosome preparations.22 The cargo of exomeres is strikingly distinct from exosomes, adding to the heterogeneity of EVs and the nanoparticle repertoire produced by host cells.22,25 Following the consensus recommendations by the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV)21,26,23, and reflecting the difficulty in defining EV subtypes based on size and biophysical properties, we herein designate exosomes as small extracellular vesicles (sEVs). Extensive reviews on the biogenesis and properties of EVs, which are not a focus of this text, have been published elsewhere.19,26,23,27 Here we focus on the intriguing interplay between EVs and viruses, particularly as it pertains to human placental trophoblasts. These cells use sophisticated defense mechanisms to confront viruses that may reach the placenta, and thus protect against transmission of viruses to the developing fetus.

Human placental EVs have been shown to convey intercellular messages at the fetal-maternal interface28 and play a pivotal role in cellular adaptation processes, including remodeling of maternal endothelial cells29–31, immuno-modulation and tolerance32–36, and defense against viral infection.37,5 Based on their potential role in maternal-fetal interaction and disorders of pregnancy, the impact of placental EVs and their cargo has been studied in the context of gestational diseases. These include studies of biomarkers of environmental pollutant-induced injury or pregnancy disorders, including intrauterine growth restriction, preterm birth, and preeclampsia.38–44 For more details, the readers are referred to other reviews in this special issue on placental EVs and disorders of pregnancy. Here we focus on current knowledge of trophoblastic EVs and relevant viral infections during pregnancy.

EVs and viruses: similarities and dissimilarities

Before reviewing the complex interaction of EVs with pregnancy-related pathogenic viruses and the role of EV-based defense against viruses, we compare several key properties that define EVs and viral pathogens, emphasizing similar characteristics and differences.

Size and Shape

The size of most viruses is in the range of 20~500 nm in diameter, which overlaps with the size distribution of EVs. Unlike the roughly spherical structure of EVs, with an outer phospholipid bilayer membrane, many viruses have less spherical nucleocapsid shapes, such as rods or polygonal spheres, attributed to viral nucleoproteins (or capsid proteins) and their interaction with viral nucleic acids. Additionally, certain viruses, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), have an extra lipid membrane bilayer intercalated with viral enveloped proteins, leading to spherical or rod-like shapes.

Vesiculated or Non-vesiculated forms

Depending on the encasement of the nucleocapsid core in a lipid layer derived from host cell membrane, viruses are categorized as non-enveloped or lipid-enveloped. As such, vesiculated viruses resemble EVs and may use similar routes to enter target cells. Notably, differences in vesiculation among non-enveloped viruses, enveloped viruses, and vesiculated EVs may be blurred in some circumstances. For instance, hepatitis A viruses, presumably non-enveloped, cloak their nucleocapsids with host cell–derived lipid membrane when circulating in the plasma of infected humans.45 Upon egress from host cells, some enveloped viruses, such as hepatitis C virus, disguise progeny virions with an additional lipid membrane bilayer and associated host cellular proteins.46 In a more compound scenario, EVs derived from virus-infected cells might enclose viral miRNAs47, further obscuring the boundary between cellular EVs and EVs derived from progeny virions.

Formation and Propagation

Key proteins that control the intricate steps of exocytosis are utilized in biogenesis of both EVs and viruses.48,49 Processing within the cellular endosomal network, including both early and late endosomes, and the subsequent fusion of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) with the plasma membrane or the alternative direct budding of plasma membrane, are obligatory for EV generation and egress from parental cells.7 Likewise, viruses also leverage the endosomal network and MVBs to facilitate their replication, assembly, and release from host cells. Mechanistically, Rab27a/b50, SNAP protein and its cognate SNAP REceptor (SNARE) protein complexes51, and the Endosomal Sorting Complexes Required for Transport (ESCRT) multiple subunit family members, including ALIX1 and TSG101, promote fusion of MVBs with the plasma membrane and facilitate the release of both viruses and intraluminal vesicles (which will become EVs) from host cells52. As expected, certain virus families may preferentially deploy discrete subsets of host cell proteins to support their replication, assembly, and release. Similarly, EVs derived from various cell types also evolve unique mechanisms to modulate their biogenesis pathways, such as ceramide-dependent, but ESCRT-independent, signaling.53,54 Nevertheless, viruses and EVs are fundamentally distinct in the ability to replicate: while some viruses may not propagate or egress from host cells, most can synthesize progeny virions in the infected recipient cells and resort to new-round infection events. In contrast, currently there is no evidence that EVs bear the capability to propagate in recipient cells.

Cargo content

The DNA or RNA genomes enclosed within viruses encode viral proteins that engage host cells in support of viral replication. Moreover, DNA viruses such as human cytomegalovirus (hCMV) and retrovirus HIV-1 leverage host machinery to transcribe viral miRNAs, which functionally repress host cell mRNA transcripts and therefore facilitate viral replication.55–57 Interestingly, EV’s RNA cargo, such as miRNAs, has been demonstrated to attenuate the expression of host target genes and therefore redirect recipient cells into pathophysiological pathways, including aging, lipodystrophy, and tumor metastasis.14,13,58,3 Viruses package viral genomes as nucleocapsids and transcribe viral miRNAs following delivery of their genomes to the host. EVs encapsulate miRNAs upon egress from donor cells, yet pathways for processing EV miRNA cargo and its delivery to Argonaute proteins in RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC)59 remain unclear. The possibility that Argonaute proteins might be a part of the sEVs’ cargo was recently ruled out by Coffey’s group, who demonstrated that Argonaute proteins are present in non-vesicular forms rather than in sEVs.21 These data are consistent with our previous findings based on human trophoblastic sEVs.37 Compared to viruses bearing DNA genomes, sEVs have no double-strand DNA (dsDNA) and associated histone proteins.

Given that both EVs and viruses exploit similar biogenesis pathways, it is not surprising that they may share similar lipid composition.48,27 Notwithstanding the resemblance, there are unambiguous differences in the protein landscape between EVs and viruses. Unlike EV proteins that were derived from donor cells, viruses contain non-cellular, virus-specific proteins, which assist them in entry into the host and multiply progeny virions.60,61 Collectively, while cargo delivery by both viruses and EVs can reprogram some functions of the recipient cells, the consequences are unequivocally distinctive in that viruses may lead to detrimental effects on the host, whereas EVs, depending on affected signaling cascades and the cellular context, might elicit both beneficial and deleterious effects on recipient cells.

Target cells: Entry and endocytosis

EVs enter target cells to execute their function, whereas viruses must enter target cells for replication. Based on this notion, and the structural similarity between viruses and EVs, it is not surprising that EVs and viruses may utilize similar cell recognition, attachment, and endocytic mechanisms to target intracellular domains. When compared to EV processing, more is currently known about virus uptake and processing in target cells.

The entry of viruses into cells is a stepwise process, with initial interaction taking place upon virus attachment to surface factors on the cellular plasma membrane, followed by receptor clustering into macrodomains, signaling activation, formation of endocytic vesicles with delivery of viral cargo into endosomes, endosomal sorting and trafficking, and a final escape from the endosomes. Similarly to viruses, EVs utilize multiple nonexclusive entry mechanisms to deliver their cargo into recipient cells and execute their functions.19,62 The initial interaction that guides EV attachment to a specific cell may take place using “barcode and reader” recognition proteins that are also involved in endocytosis pathways, including clathrin-mediated and caveolae-mediated endocytosis.63,64 Cell entry by enveloped viruses, such as herpes simplex virus (HSV), also entails virus and plasma membrane fusion, primed by viral fusion proteins to overcome energy barriers imposed by the two merging lipid bilayer structures.65 Intriguingly, the fusogenic proteins syncytin1/2 (ERVW-1 and ERVFRD-1), derived from envelope proteins of human endogenous retroviruses (ERV) and predominantly expressed in the placenta, are present in trophoblastic sEVs as well66,67,37 and are postulated to regulate sEV fusion with target cells.37,66 Cellular surface protein integrins that guide viral entry are also packaged in sEVs, including human trophoblastic sEVs37, leading to tumor sEV-mediated organotropic metastasis.68,62 In addition to protein barcode and reader-conferred viral entry, viral envelope phospholipid phosphatidylserine (PS), alongside PS-adaptor protein Gas6, mediate viral entry of cells by binding to Axl, a TAM receptor tyrosine kinase on target host cells.69 Notably, we found that phosphatidylserine is also expressed on human trophoblastic EVs, including ABs, MVs, and sEVs.37

Upon internalization, viruses usurp the cell endocytic pathways for further processing. The assortment of viral receptor proteins and pathways used for cell entry guide the interaction of viruses or EVs with the cellular endocytosis pathways, including clathrin-mediated endocytosis, caveolae-mediated endocytosis, and macropinocytosis.68,19,70 Fascinatingly, the cells deploy similar endocytic pathways to block viral replication, thus staging the cell-virus war at the endocytosis stage. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis is used by many viruses, such as VSV68, HIV-171, and Zika.72,73 This process includes pre-existing clathrin-coated pits or newly assembled clathrin sites, which mediate virus or EV delivery to early endosomes in the cell periphery.63 Viruses (such as simian virus 40, SV-40) that utilize caveolae-mediated endocytosis, colocalize with caveolin, with subsequent tyrosine phosphorylation–dependent virus uptake. Clathrin/caveolin-independent pathways commonly begin with a virus-induced membrane curvature and wrapping of the plasma membrane around the viral vesicles, followed by fission and delivery of the viral vesicle to early endosomes.68 Macropinocytosis, triggered by many viruses74 and likely used by EVs19, is sparked by integrins, receptor tyrosine kinase, or phosphatidylserine, followed by actin-stimulated membrane ruffling that forms filopodia, lamellipodia, or blebs, which engulf viruses or EVs, with subsequent macropinosome maturation into late endosomes and fusion with lysosomes. Consistently, filopodia are critical for sEV uptake in primary human fibroblasts.75 Using primary human placental fibroblasts and human uterine microvascular endothelial cells as likely relevant recipient cells for trophoblastic sEVs, we uncovered that trophoblastic sEVs enter these two target cells mainly through macropinocytosis and clathrin-mediated endocytosis, but not caveolin-dependent endocytosis.76

Once taken up by cells, viruses or EVs enter the cell endosomal network, sharing the space with intraluminal vesicles. If viruses or EVs do not exit the endosome into the cytosol, they presumably shuttle onward within early and late endosomes and subsequently undergo degradation in lysosomes. Notably, many viruses hijack the endosome machinery and leverage the acidic pH for fusion with the endosomal membrane, culminating in release of the viral genome. The fusogenic protein hemagglutinin (HA), expressed on the surface of influenza virus, is a canonical mediator of fusion with endosomes.77 Likewise, the enveloped retrovirus HIV-1 expresses the trimeric fusion glycoprotein gp16078, and membrane fusion largely occurs in the endosome following internalization by clathrin-mediated endocytosis, implying that HIV-1 can evade immune surveillance by reducing exposure of the viral epitope on the outer layer of host cells.71 Some viruses can escape early endosomes, late endosomes, lysosomes, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi or even recycling endosomes and form their own independent, clustered macrodomains.70 Likewise, following entry of target cells such as primary human placental fibroblasts and human uterine microvascular endothelial cells, human trophoblastic sEVs are transported to APPL1- and EEA1-positive early endosomes, and then translocated to late endosomes and lysosomes.76 Intriguingly, the majority of endocytosed sEVs deploy diverse membrane interaction modes to relocate to regions near the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Such a unique sEV-and-ER contact is believed to modulate cargo release.75 Our recent findings also revealed that miR-517a-3p, one of trophoblast-specific sEV cargo molecules, localizes to intracellular P-bodies and binds GW182 and Argonaute 2 (AGO2) in target primary human placental fibroblasts.76 The relevance of entry and endocytic pathways of placental EV may be germane to placental biology and the use of EVs in perinatal translational medicine.79

Certain sEVs suppress viral infection via delivery of vesicular cargo

Among the intricate strategies used by cells to combat viral infections, donor cells may endow neighboring and/or distant recipient cells with EV-mediated RNAs and proteins that participate in antiviral signaling cascades, thus inhibiting viral replication and/or abrogating progeny virion production and release. Relevant to modulation of trophoblast differentiation by interferon-induced transmembrane (IFITM) protein family members80, IFITM3 hinder cell entry of a broad spectrum of viruses, including the Flaviviridae family Dengue and Zika viruses, HIV-1, Influenza, and SARS coronavirus81–83, and also reroute the internalized viruses to lysosomes for degradation, thus limiting viral replication.84 Consistent with these observations, sEV-mediated transfer of vesicular IFITM3 proteins suppresses Dengue virus entry and subsequent progeny virion release.85 Cytidine deaminase APOBEC3G restrains viral replication and infectivity of a panel of retroviruses, including HIV-1, by deamination of the viral genome. Notwithstanding, the HIV-1 Vif protein resists the antiviral activity of APOBEC3G.86–89 APOBEC3G-laden sEVs also suppress viral replication of wild-type HIV-1, despite the fact that the viral genome maintains the least frequency of deamination90, suggesting that APOBEC3G is unlikely to be the sole antiviral effector of HIV-1 inhibition.

At an organ scale, sEVs might reconstruct antiviral defense mechanisms that engage multiple distinct cell types. As such, induced packaging of functional antiviral molecules into sEVs derived from one cell type may augment an antiviral response by other cell types and, in turn, impede viral infection. Type I interferon (IFN), an innate immune defense molecule, confines viral infection at the host defense frontline until an adaptive immune response is mounted.91 In addition to the direct action of IFN on host cells, IFN can stimulate the packaging of antiviral factors into sEVs and therefore propagate its antiviral activity to other cell types, usurping sEVs to execute IFN action92. Beyond augmented delivery of proteins, miRNAs such as miR-423-5p may be induced and sorted into sEVs of human diploid MRC-5 cells infected by rabies viruses and exert a suppressive effect on viral replication by repressing the suppressor of cytokine signaling 3, an inhibitor of innate interferon signaling.93

An antiviral response to sEVs takes place not only within an individual but also among individuals and across species. For instance, sEVs from healthy human semen attenuate HIV-1 infection by repressing HIV-1 proviral transcription.94 Furthermore, bacteria-released sEVs may protect women from HIV-1 infection. For example, predominant vagina-resident lactobacilli can curtail HIV-1 infection, and human ex vivo tissues or cell lines treated with lactobacillus-derived sEVs from heathy women can reduce HIV-1 attachment and entry and, consequently, HIV-1 virus load.95

Certain sEVs promote viral infection by cloaking viruses or changing vesicular cargo

The notion that certain viruses, such as retroviruses, engage inherent EV biogenesis machinery for the assembly of progeny virions96 supports the concept that EVs might augment viral infectivity. As such, progeny virions are cloaked with host cell–derived EVs and egress from infected cells via the conventional EV exocytosis pathway, rendering them Trojan horses to evade immunosurveillance.97 Supporting this notion, both non-enveloped hepatitis A viruses and enveloped hepatitis C viruses, disguised with host cell–derived lipid membrane, have been shown to circulate in the plasma of infected humans, where they act as pseudo-enveloped viruses that may acquire increased viral entry tropism or avoid neutralization by antibodies.46,45 Similarly, by hijacking EVs to harbor multiple virion copies, enteroviruses, noroviruses, and rotaviruses can overburden the host viral defense mechanisms and thus promote viral replication.98,99 Adding another dimension to virus dissemination prior to the lytic phase of viral infection, picornaviruses are released via a non-lytic route by encasing their progeny with membranes derived from multiple distinct EVs, including MVs and sEVs, which account for the discrete viral infectivity.100

In some pathological settings, despite the fact that sEVs derived from infected cells do not contain intact virions and had therefore been presumed to be noninfectious101, sEV content, including vesicular protein and miRNA cargoes, may be altered by incorporating significant amounts of viral proteins or miRNAs following viral infection.102,47 Such virus-primed sEVs can reprogram recipient uninfected cells to facilitate virus spread via increased cell-to-cell contact101 or by potentiating their susceptibility to viral infection.103 In addition, a virus-favorable niche reconstructed by virus-educated sEVs is associated with tumor virus–initiated cell transformation.104 For instance, Epstein-Barr Virus exploits sEVs to transport viral miRNAs into uninfected recipient cells and repress host cell transcription of immunoregulatory genes such as CXCL11.47

Virus-derived factors packaged within sEVs may exert detrimental collateral damage on non-infected “bystander” cells and, therefore, in conjunction with the propagation of virions in permissive cells, ultimately result in tissue or organ dysfunction. Contributing to in vivo HIV-1-sparked clinical comorbidity, such as abnormal hematopoiesis and atherosclerosis, HIV-1 protein Nef-containing sEVs alter lipid raft composition through replacement of TLR4 and TREM-1 to lipid rafts of “bystander” cells and lead to boosted secretion of proinflammatory cytokines.105 In some pathophysiological situations, tumorigenesis may be functionally associated with augmented viral infection due to suppression of innate immunity. Consistent with this notion, tumor-derived EGFR-positive sEVs enhance viral infection in host macrophages by dampening in vivo innate antiviral response.106

Human pregnancy, viral infection, and trophoblastic sEV-mediated defense mechanisms

Antenatal vertical transmission of DNA viruses, including hCMVs and parvovirus B19 (PVB19), and RNA viruses, such as rubella virus (RV) and Zika virus (ZIKV), has been shown to cause human congenital syndromes.107–109 For instance, maternal infection by RV during the first trimester of human pregnancy is associated with fetal congenital rubella syndrome, including cardiovascular anomalies, microcephaly, deafness and related conditions. While the exact mechanisms by which RV infects the human placenta and subsequently results in congenital rubella syndrome remain unclear, the problems associated with this syndrome has been largely eliminated by the prevalent deployment of an effective RV vaccine.

Placental proteins and glycosphingolipids are likely utilized as receptors to facilitate virus entry into the placenta, with subsequent intrauterine transmission.107 For instance, ZIKV infection of pregnant women is associated with fetal neurological deficits, including microcephaly and retinal damage, and causes major fetal morbidity and mortality. Rather than replicating in syncytiotrophoblasts (STBs)110, ZIKV robustly replicates in placental cells expressing viral entry cofactors Axl and TIM1, including extravillous trophoblasts and placenta-specific Hofbauer macrophages.111,112 PVB19 affects fetal erythropoiesis and may lead to hydrops fetalis due to fetal anemia.107 Glycosphingolipid globoside113, a receptor for PVB19, in conjunction with viral coreceptors such as α5β1 integrin114 and Ku80115, are deployed for virion attachment and internalization through endocytosis pathways. Intriguingly, globoside is strongly expressed in the villous trophoblasts of first and second trimester placentas rather than in those of third trimester, which may, in part, contribute to the observation that maternal infection of PVB19 in early gestation may lead to worse outcomes when compared to near-term infection.113 Maternal hCMV infection poses a risk of fetal transmission, with subsequent birth defects, including cognitive impairment, hearing loss, and intrauterine growth restriction. hCMV replicates in villous cytotrophoblasts (CTBs) by resorting to neonatal Fc receptor–mediated transcytosis from STBs to the underlying CTBs, where most of its replication takes place.116,117 In addition to transcytosis entry, hCMVs also infect chorionic trophoblast progenitors118, extravillous trophoblasts119, and amniotic epithelial cells.120

Most recently, a novel bat-borne, RNA betacoronavirus, SARS-CoV-2121, which resembles the coronaviruses that caused severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and middle eastern respiratory syndrome (MERS), caused viral pneumonia and the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. While the precise mechanisms underlying SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis are being uncovered, recent data indicate that the transmembrane TMPRSS2 serine protease is required for priming the viral surface Spike proteins that subsequently utilize angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) act as receptors for virus entry.121,122 Although these proteins are expressed in human placental trophoblasts123,124, current data indicate that, even during maternal viremia, the feto-placental compartment is relatively spared from SARS-CoV-2 infection at least in the third trimester.125–127 This suggests that the human placenta may mount effective viral defense pathways even when this typically airborne virus is present in the blood stream and can infect other internal organs.128

The morphology of the human placenta constitutes a sophisticated physical barrier of syncytialized cells that may attenuate infection by viruses that circulate in the maternal blood.129,130 Supporting this notion, primary human trophoblasts, isolated from normal full-term placentas, are relatively resistant in vitro to a diverse range of viruses, including DNA and RNA viruses such as HSV, hCMV, HIV-1, and ZIKV, when compared to other cell types.131,132,110 Autophagy is engaged in host antiviral defense by activating pattern recognition receptor signaling due to pathogen-associated molecular patterns of the invading viruses, and subsequently diverting them to lysosomes for degradation.133 We found that the relative viral resistance of primary human trophoblasts is not due to defects of viral entry, and instead, primary human trophoblasts exhibit high levels of basal autophagy, which in part contributes to the relative resistance of these cells to viruses.131 Conditioned primary human trophoblasts medium containing trophoblastic sEVs can also induce autophagy in non-placental cells and render them relatively resistant to viral infection including VSV, Coxsackievirus B, and Hepatitis C virus. Mechanistically, viral resistance is attributed, at least in part, to released trophoblastic sEVs and cargo miRNAs of the chromosome 19 microRNA cluster (C19MC) family.5,131 C19MC miRNAs are primate specific and almost exclusively expressed in the placenta, where they represent the majority of the miRNAs expressed in trophoblasts.134

Both sEVs and cargo C19MC miRNAs such as miR-517a-3p promote autophagy and viral degradation within autolysosomes, thus restraining a subsequent virus uncoating process and cytoplasmic viral replication.131 Of note, we showed that the expression of C19MC miRNAs, detectable in maternal plasma as early as 2 weeks after implantation, is not affected by maternal infection with hCMV, and that C19MC miRNA augment infection of other cell types by hCMV135,131, implicating a more complex interaction of hCMV with trophoblastic antiviral pathways.

The C19MC-mediated effect on viral infection is largely executed by trophoblastic sEVs, not ABs or MVs.37 Furthermore, C19MC-laden sEVs execute their antiviral activity without affecting interferons and interferon-stimulated genes such as IFI44L.136 This antiviral phenotype is recapitulated from plasma sEVs of pregnant women compared to those from non-pregnant women.37 Additional data also indicate that a C19MC-independent defense mechanism, type III interferon, IFN-λ, participates in protection of primary human trophoblasts against viral infection.110,136 Collectively, both C19MC miRNAs and IFN-λ are expressed in primary human trophoblasts and orchestrate two independent antiviral defense mechanisms. Whereas IFN-λ or trophoblastic C19MC-containing sEVs attenuate VSV infection, concomitant exposure of target cells to IFN-λ and sEVs leads to an additive antiviral effect.136 Moreover, C19MC-containing sEVs can communicate an antiviral activity to a broad range of non-trophoblastic cells, including other local placental cells, maternal cells, or possibly, fetal cells.137 In line with this notion, we recently uncovered that two primary human cells that do not endogenously transcribe C19MC miRNAs, including primary human placental fibroblasts and human uterine microvascular endothelial cells, exhibit an antiviral effect after uptake of C19MC-laden sEVs.76 While the mechanisms underlying these observations are currently being pursued, these findings illuminate unprecedented mechanisms employed by human trophoblasts at a systemic scale during pregnancy.

Future perspectives

While the early data on the function of placental sEVs in pregnancy disorders are intriguing, the underpinnings of placental sEV biogenesis and their interaction with maternal tissues and organs remain enigmatic.79 EVs enter cells via various endocytosis routes, dictated by the nature of their interaction with recipient cells.19,138 Deep insight into the mechanisms underlying the action of barcode-like molecules at the two apposing sEV and cell lipid membranes, followed by entry into recipient cells, is lacking. Advanced imaging technologies, such as super resolution microscopy, and novel genetic tracking systems are needed in order to tackle such fundamental questions. An additional, critical question is how processing of placental sEV cargo is intimately connected to the control of cell and tissue homeostasis and/or resilience. In this regard, fusion of sEVs with the endosome membrane might be essential for vesicular cargo release. Decoding these molecular mechanisms, using in vitro cell culture studies with in vivo animal tracking approaches, will shed light on the functional relevance of placental EVs to pregnancy adaptation and response to viral pathogens.

Depending on the specific cellular contexts, the interplay of EVs and viruses may have a profound impact on viral replication and infectivity. Deepening our knowledge of key factors that mediate such bidirectional effects may suggest new pathways for protection against viral infection. In light of our discovery that trophoblastic sEVs relay an antiviral program at the maternal-fetal interface, further research into effector molecules that mediate C19MC-conferred antiviral response may shed light on the interaction of sEVs and viruses and become instrumental in initiating therapeutic intervention against viral infection. Such research may also advance our understanding of the on-going conflict between viral infection and placental responses to such infection, and the antiviral and proviral effect of certain proteins and RNAs, as shown in other contexts.139–142 It may also explain why some placentas and fetuses are infected by certain viruses during maternal viremia, and others are not. Within this context, a critical challenge lies in the unambiguous separation of EVs-derived from infected cells from released virions that co-exist in the extracellular space and may rely on understanding the contributions of virus-primed EVs and viruses alone to viral infectivity. Leveraging the unique biochemical and biophysical properties of EVs or encapsulated viruses, combined with enhanced flow cytometry-based single-vesicle sorting, may provide solutions to this challenge.7,143–147

From the translational medicine viewpoint, EV-based therapeutics is an emerging area that explores the implementation of personalized and precision medicine approaches to diseases.148 Research using engineered EVs, consisting of appropriate antiviral agents that facilitate their specific targeting to eradicate virus latency, is being vigorously pursued. One promising strategy is deploying an HIV-neutralizing antibody and apoptosis inducers into EVs in order to suppress viral replication.149 Such breakthroughs can markedly advance our knowledge of the complex interplay between EVs and viruses.

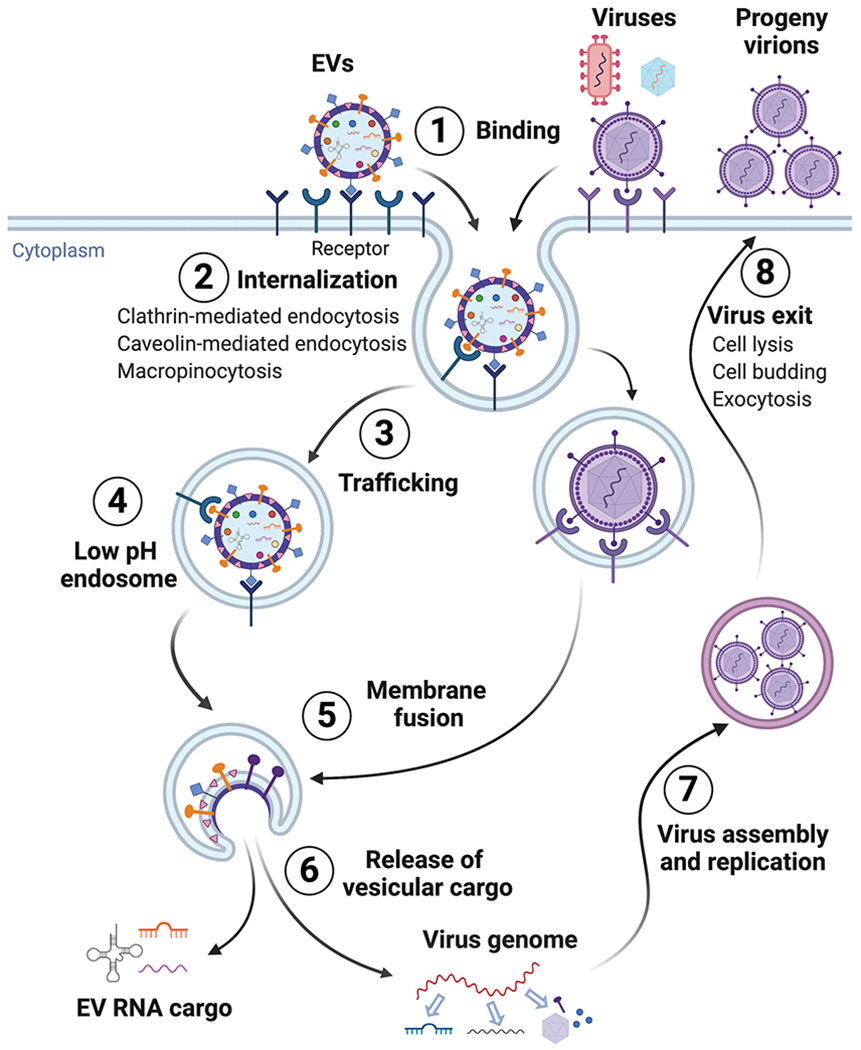

Figure 1. A general schematic illustrating how EVs and viruses enter cells via endocytosis and fusion-triggered endosomal escape for cargo release and subsequent processing.

EVs and viruses, including lipid enveloped or non-enveloped forms, enter their target cell by binding to specific receptors on the plasma membrane (1). They are subsequently internalized into endosomal vesicles through multiple endocytosis pathways, mainly including clathrin-mediated endocytosis, caveolin-mediated endocytosis, and macropinocytosis (2). Direct virus and plasma membrane fusion-mediated cell entry, utilized by certain viruses, is not shown, but described in the text. This is followed by trafficking within the endosomal network, including early endosome, late endosome or endolysosome (3), EVs and viruses reach the low-pH endosomal compartment (4) where fusogenic proteins on the surface membrane of EVs or viruses trigger membrane fusion (5), with subsequent cargo release to the cytosol (6). EV cargo, including diverse coding or non-coding RNA types, are released and likely execute their function in target recipient cells. In contrast, viral DNA or RNA genomes are released and processed for transcription and replication. The processing of EV or viral proteins is not shown. Unlike the arrival of EVs to their “final destination”, viruses can usurp host cell machinery to synthesize viral nonstructural proteins such as viral polymerase and/or integrase to support viral replication. Consequently, assembled viral genome and proteins may begin replication (7). Lastly, progeny virions utilize exocytosis pathways, cell budding or cell lysis for exit and virus dissemination (8). Additional similarities and dissimilarities in EV and virus pathways are detailed in the text. This figure was created with BioRender.com.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lori Rideout for assistance with manuscript preparation and Bruce Campbell for editing. The project was supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) grants R01HD086325 and R37HD086916, the 25 Club of Magee-Womens Hospital, and the Margaret Ritchie R. Battle Family Charitable Fund.

Footnotes

Disclosures Y.S. is a consultant to Illumina, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murillo OD, Thistlethwaite W, Rozowsky J, Subramanian SL, Lucero R, Shah N, Jackson AR, Srinivasan S, Chung A, Laurent CD, Kitchen RR, Galeev T, Warrell J, Diao JA, Welsh JA, Hanspers K, Riutta A, Burgstaller-Muehlbacher S, Shah RV, Yeri A, Jenkins LM, Ahsen ME, Cordon-Cardo C, Dogra N, Gifford SM, Smith JT, Stolovitzky G, Tewari AK, Wunsch BH, Yadav KK, Danielson KM, Filant J, Moeller C, Nejad P, Paul A, Simonson B, Wong DK, Zhang X, Balaj L, Gandhi R, Sood AK, Alexander RP, Wang L, Wu C, Wong DTW, Galas DJ, Van Keuren-Jensen K, Patel T, Jones JC, Das S, Cheung KH, Pico AR, Su AI, Raffai RL, Laurent LC, Roth ME, Gerstein MB, Milosavljevic A. exRNA atlas analysis reveals distinct extracellular RNA cargo types and their carriers present across human biofluids. Cell. 2019;177(2):463–477.e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srinivasan S, Yeri A, Cheah PS, Chung A, Danielson K, De Hoff P, Filant J, Laurent CD, Laurent LD, Magee R, Moeller C, Murthy VL, Nejad P, Paul A, Rigoutsos I, Rodosthenous R, Shah RV, Simonson B, To C, Wong D, Yan IK, Zhang X, Balaj L, Breakefield XO, Daaboul G, Gandhi R, Lapidus J, Londin E, Patel T, Raffai RL, Sood AK, Alexander RP, Das S, Laurent LC. Small RNA Sequencing across diverse biofluids identifies optimal methods for exRNA isolation. Cell. 2019;177(2):446–462.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y, Kim MS, Jia B, Yan J, Zuniga-Hertz JP, Han C, Cai D. Hypothalamic stem cells control ageing speed partly through exosomal miRNAs. Nature. 2017;548(7665):52–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keller MD, Ching KL, Liang FX, Dhabaria A, Tam K, Ueberheide BM, Unutmaz D, Torres VJ, Cadwell K. Decoy exosomes provide protection against bacterial toxins. Nature. 2020;579(7798):260–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ouyang Y, Mouillet JF, Coyne CB, Sadovsky Y. Placenta-specific microRNAs in exosomes - good things come in nano-packages. Placenta. 2014;35(Suppl):S69–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meckes DG Jr., Raab-Traub N. Microvesicles and viral infection. J Virol. 2011;85(24):12844–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nolte-’T Hoen E, Cremer T, Gallo RC, Margolis LB. Extracellular vesicles and viruses: Are they close relatives? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(33):9155–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robbins PD, Morelli AE. Regulation of immune responses by extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(3):195–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen G, Huang AC, Zhang W, Zhang G, Wu M, Xu W, Yu Z, Yang J, Wang B, Sun H, Xia H, Man Q, Zhong W, Antelo LF, Wu B, Xiong X, Liu X, Guan L, Li T, Liu S, Yang R, Lu Y, Dong L, Mcgettigan S, Somasundaram R, Radhakrishnan R, Mills G, Lu Y, Kim J, Chen YH, Dong H, Zhao Y, Karakousis GC, Mitchell TC, Schuchter LM, Herlyn M, Wherry EJ, Xu X, Guo W. Exosomal PD-L1 contributes to immunosuppression and is associated with anti-PD-1 response. Nature. 2018;560(7718):382–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamerkar S, Lebleu VS, Sugimoto H, Yang S, Ruivo CF, Melo SA, Lee JJ, Kalluri R. Exosomes facilitate therapeutic targeting of oncogenic KRAS in pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2017;546(7659):498–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Nedawi K, Meehan B, Micallef J, Lhotak V, May L, Guha A, Rak J. Intercellular transfer of the oncogenic receptor EGFRvIII by microvesicles derived from tumour cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(5):619–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tkach M, Thery C. Communication by extracellular vesicles: Where we are and where we need to go. Cell. 2016;164(6):1226–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomou T, Mori MA, Dreyfuss JM, Konishi M, Sakaguchi M, Wolfrum C, Rao TN, Winnay JN, Garcia-Martin R, Grinspoon SK, Gorden P, Kahn CR. Adipose-derived circulating miRNAs regulate gene expression in other tissues. Nature. 2017;542(7642):450–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, Sjostrand M, Lee JJ, Lotvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(6):654–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinger SA, Cha DJ, Franklin JL, Higginbotham JN, Dou Y, Ping J, Shu L, Prasad N, Levy S, Zhang B, Liu Q, Weaver AM, Coffey RJ, Patton JG. Diverse long RNAs are differentially sorted into extracellular vesicles secreted by colorectal cancer cells. Cell Rep. 2018;25(3):715–725.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shurtleff MJ, Yao J, Qin Y, Nottingham RM, Temoche-Diaz MM, Schekman R, Lambowitz AM. Broad role for YBX1 in defining the small noncoding RNA composition of exosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(43):E8987–e8995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Vizio D, Morello M, Dudley AC, Schow PW, Adam RM, Morley S, Mulholland D, Rotinen M, Hager MH, Insabato L, Moses MA, Demichelis F, Lisanti MP, Wu H, Klagsbrun M, Bhowmick NA, Rubin MA, D’souza-Schorey C, Freeman MR. Large oncosomes in human prostate cancer tissues and in the circulation of mice with metastatic disease. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(5):1573–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meehan B, Rak J, Di Vizio D. Oncosomes - large and small: What are they, where they came from? J Extracell Vesicles. 2016;533109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathieu M, Martin-Jaular L, Lavieu G, Thery C. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21(1):9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalluri R, Lebleu VS. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science. 2020;367(6478). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeppesen DK, Fenix AM, Franklin JL, Higginbotham JN, Zhang Q, Zimmerman LJ, Liebler DC, Ping J, Liu Q, Evans R, Fissell WH, Patton JG, Rome LH, Burnette DT, Coffey RJ. Reassessment of exosome composition. Cell. 2019;177(2):428–445.e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang H, Freitas D, Kim HS, Fabijanic K, Li Z, Chen H, Mark MT, Molina H, Martin AB, Bojmar L, Fang J, Rampersaud S, Hoshino A, Matei I, Kenific CM, Nakajima M, Mutvei AP, Sansone P, Buehring W, Wang H, Jimenez JP, Cohen-Gould L, Paknejad N, Brendel M, Manova-Todorova K, Magalhaes A, Ferreira JA, Osorio H, Silva AM, Massey A, Cubillos-Ruiz JR, Galletti G, Giannakakou P, Cuervo AM, Blenis J, Schwartz R, Brady MS, Peinado H, Bromberg J, Matsui H, Reis CA, Lyden D. Identification of distinct nanoparticles and subsets of extracellular vesicles by asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20(3):332–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thery C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ, Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, Antoniou A, Arab T, Archer F, Atkin-Smith GK, Ayre DC, Bach JM, Bachurski D, Baharvand H, Balaj L, Baldacchino S, Bauer NN, Baxter AA, Bebawy M, Beckham C, Bedina Zavec A, Benmoussa A, Berardi AC, Bergese P, Bielska E, Blenkiron C, Bobis-Wozowicz S, Boilard E, Boireau W, Bongiovanni A, Borras FE, Bosch S, Boulanger CM, Breakefield X, Breglio AM, Brennan MA, Brigstock DR, Brisson A, Broekman ML, Bromberg JF, Bryl-Gorecka P, Buch S, Buck AH, Burger D, Busatto S, Buschmann D, Bussolati B, Buzas EI, Byrd JB, Camussi G, Carter DR, Caruso S, Chamley LW, Chang YT, Chen C, Chen S, Cheng L, Chin AR, Clayton A, Clerici SP, Cocks A, Cocucci E, Coffey RJ, Cordeiro-Da-Silva A, Couch Y, Coumans FA, Coyle B, Crescitelli R, Criado MF, D’souza-Schorey C, Das S, Datta Chaudhuri A, De Candia P, De Santana EF, De Wever O, Del Portillo HA, Demaret T, Deville S, Devitt A, Dhondt B, Di Vizio D, Dieterich LC, Dolo V, Dominguez Rubio AP, Dominici M, Dourado MR, Driedonks TA, Duarte FV, Duncan HM, Eichenberger RM, Ekstrom K, El Andaloussi S, Elie-Caille C, Erdbrugger U, Falcon-Perez JM, Fatima F, Fish JE, Flores-Bellver M, Forsonits A, Frelet-Barrand A, Fricke F, Fuhrmann G, Gabrielsson S, Gamez-Valero A, Gardiner C, Gartner K, Gaudin R, Gho YS, Giebel B, Gilbert C, Gimona M, Giusti I, Goberdhan DC, Gorgens A, Gorski SM, Greening DW, Gross JC, Gualerzi A, Gupta GN, Gustafson D, Handberg A, Haraszti RA, Harrison P, Hegyesi H, Hendrix A, Hill AF, Hochberg FH, Hoffmann KF, Holder B, Holthofer H, Hosseinkhani B, Hu G, Huang Y, Huber V, Hunt S, Ibrahim AG, Ikezu T, Inal JM, Isin M, Ivanova A, Jackson HK, Jacobsen S, Jay SM, Jayachandran M, Jenster G, Jiang L, Johnson SM, Jones JC, Jong A, Jovanovic-Talisman T, Jung S, Kalluri R, Kano SI, Kaur S, Kawamura Y, Keller ET, Khamari D, Khomyakova E, Khvorova A, Kierulf P, Kim KP, Kislinger T, Klingeborn M, Klinke DJ 2nd, Kornek M, Kosanovic MM, Kovacs AF, Kramer-Albers EM, Krasemann S, Krause M, Kurochkin IV, Kusuma GD, Kuypers S, Laitinen S, Langevin SM, Languino LR, Lannigan J, Lasser C, Laurent LC, Lavieu G, Lazaro-Ibanez E, Le Lay S, Lee MS, Lee YXF, Lemos DS, Lenassi M, Leszczynska A, Li IT, Liao K, Libregts SF, Ligeti E, Lim R, Lim SK, Line A, Linnemannstons K, Llorente A, Lombard CA, Lorenowicz MJ, Lorincz AM, Lotvall J, Lovett J, Lowry MC, Loyer X, Lu Q, Lukomska B, Lunavat TR, Maas SL, Malhi H, Marcilla A, Mariani J, Mariscal J, Martens-Uzunova ES, Martin-Jaular L, Martinez MC, Martins VR, Mathieu M, Mathivanan S, Maugeri M, Mcginnis LK, Mcvey MJ, Meckes DG Jr., Meehan KL, Mertens I, Minciacchi VR, Moller A, Moller Jorgensen M, Morales-Kastresana A, Morhayim J, Mullier F, Muraca M, Musante L, Mussack V, Muth DC, Myburgh KH, Najrana T, Nawaz M, Nazarenko I, Nejsum P, Neri C, Neri T, Nieuwland R, Nimrichter L, Nolan JP, Nolte-’T Hoen EN, Noren Hooten N, O’driscoll L, O’grady T, O’loghlen A, Ochiya T, Olivier M, Ortiz A, Ortiz LA, Osteikoetxea X, Ostergaard O, Ostrowski M, Park J, Pegtel DM, Peinado H, Perut F, Pfaffl MW, Phinney DG, Pieters BC, Pink RC, Pisetsky DS, Pogge Von Strandmann E, Polakovicova I, Poon IK, Powell BH, Prada I, Pulliam L, Quesenberry P, Radeghieri A, Raffai RL, Raimondo S, Rak J, Ramirez MI, Raposo G, Rayyan MS, Regev-Rudzki N, Ricklefs FL, Robbins PD, Roberts DD, Rodrigues SC, Rohde E, Rome S, Rouschop KM, Rughetti A, Russell AE, Saa P, Sahoo S, Salas-Huenuleo E, Sanchez C, Saugstad JA, Saul MJ, Schiffelers RM, Schneider R, Schoyen TH, Scott A, Shahaj E, Sharma S, Shatnyeva O, Shekari F, Shelke GV, Shetty AK, Shiba K, Siljander PR, Silva AM, Skowronek A, Snyder OL, Soares RP, Sodar BW, Soekmadji C, Sotillo J, Stahl PD, Stoorvogel W, Stott SL, Strasser EF, Swift S, Tahara H, Tewari M, Timms K, Tiwari S, Tixeira R, Tkach M, Toh WS, Tomasini R, Torrecilhas AC, Tosar JP, Toxavidis V, Urbanelli L, Vader P, Van Balkom BW, Van Der Grein SG, Van Deun J, Van Herwijnen MJ, Van Keuren-Jensen K, Van Niel G, Van Royen ME, Van Wijnen AJ, Vasconcelos MH, Vechetti IJ Jr., Veit TD, Vella LJ, Velot E, Verweij FJ, Vestad B, Vinas JL, Visnovitz T, Vukman KV, Wahlgren J, Watson DC, Wauben MH, Weaver A, Webber JP, Weber V, Wehman AM, Weiss DJ, Welsh JA, Wendt S, Wheelock AM, Wiener Z, Witte L, Wolfram J, Xagorari A, Xander P, Xu J, Yan X, Yanez-Mo M, Yin H, Yuana Y, Zappulli V, Zarubova J, Zekas V, Zhang JY, Zhao Z, Zheng L, Zheutlin AR, Zickler AM, Zimmermann P, Zivkovic AM, Zocco D, Zuba-Surma EK. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles. 2018;7(1):1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding W, Rivera OC, Kelleher SL, Soybel DI. Macrolets: outsized extracellular vesicles released from lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages that trap and kill Escherichia coli. iScience. 2020;23(6):101135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Q, Higginbotham JN, Jeppesen DK, Yang YP, Li W, Mckinley ET, Graves-Deal R, Ping J, Britain CM, Dorsett KA, Hartman CL, Ford DA, Allen RM, Vickers KC, Liu Q, Franklin JL, Bellis SL, Coffey RJ. Transfer of functional cargo in exomeres. Cell Rep. 2019;27(3):940–954.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Das S, Ansel KM, Bitzer M, Breakefield XO, Charest A, Galas DJ, Gerstein MB, Gupta M, Milosavljevic A, Mcmanus MT, Patel T, Raffai RL, Rozowsky J, Roth ME, Saugstad JA, Van Keuren-Jensen K, Weaver AM, Laurent LC. The Extracellular RNA Communication Consortium: Establishing foundational knowledge and technologies for extracellular RNA research. Cell. 2019;177(2):231–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Niel G, D’angelo G, Raposo G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19(4):213–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong M, Chamley LW. Placental extracellular vesicles and feto-maternal communication. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015;5(3):a023028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta AK, Rusterholz C, Huppertz B, Malek A, Schneider H, Holzgreve W, Hahn S. A comparative study of the effect of three different syncytiotrophoblast micro-particles preparations on endothelial cells. Placenta. 2005;26(1):59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salomon C, Torres MJ, Kobayashi M, Scholz-Romero K, Sobrevia L, Dobierzewska A, Illanes SE, Mitchell MD, Rice GE. A gestational profile of placental exosomes in maternal plasma and their effects on endothelial cell migration. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e98667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salomon C, Ryan J, Sobrevia L, Kobayashi M, Ashman K, Mitchell M, Rice GE. Exosomal signaling during hypoxia mediates microvascular endothelial cell migration and vasculogenesis. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kshirsagar SK, Alam SM, Jasti S, Hodes H, Nauser T, Gilliam M, Billstrand C, Hunt JS, Petroff MG. Immunomodulatory molecules are released from the first trimester and term placenta via exosomes. Placenta. 2012;33(12):982–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stenqvist AC, Nagaeva O, Baranov V, Mincheva-Nilsson L. Exosomes secreted by human placenta carry functional Fas ligand and TRAIL molecules and convey apoptosis in activated immune cells, suggesting exosome-mediated immune privilege of the fetus. J Immunol. 2013;191(11):5515–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lokossou AG, Toudic C, Nguyen PT, Elisseeff X, Vargas A, Rassart E, Lafond J, Leduc L, Bourgault S, Gilbert C, Scorza T, Tolosa J, Barbeau B. Endogenous retrovirus-encoded Syncytin-2 contributes to exosome-mediated immunosuppression of T cells. Biol Reprod. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alam SMK, Jasti S, Kshirsagar SK, Tannetta DS, Dragovic RA, Redman CW, Sargent IL, Hodes HC, Nauser TL, Fortes T, Filler AM, Behan K, Martin DR, Fields TA, Petroff BK, Petroff MG. Trophoblast glycoprotein (TPGB/5T4) in human placenta: Expression, regulation, and presence in extracellular microvesicles and exosomes. Reprod Sci. 2018;25(2):185–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaminski VL, Ellwanger JH, Chies JaB. Extracellular vesicles in host-pathogen interactions and immune regulation - exosomes as emerging actors in the immunological theater of pregnancy. Heliyon. 2019;5(8):e02355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ouyang Y, Bayer A, Chu T, Tyurin VA, Kagan VE, Morelli AE, Coyne CB, Sadovsky Y. Isolation of human trophoblastic extracellular vesicles and characterization of their cargo and antiviral activity. Placenta. 2016;4786–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheller-Miller S, Radnaa E, Arita Y, Getahun D, Jones RJ, Peltier MR, Menon R. Environmental pollutant induced cellular injury is reflected in exosomes from placental explants. Placenta. 2020;8942–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitchell MD, Peiris HN, Kobayashi M, Koh YQ, Duncombe G, Illanes SE, Rice GE, Salomon C. Placental exosomes in normal and complicated pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4 Suppl):S173–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jin J, Menon R. Placental exosomes: A proxy to understand pregnancy complications. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2018;79(5):e12788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rubens CE, Sadovsky Y, Muglia L, Gravett MG, Lackritz E, Gravett C. Prevention of preterm birth: Harnessing science to address the global epidemic. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(262):262sr5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gill M, Motta-Mejia C, Kandzija N, Cooke W, Zhang W, Cerdeira AS, Bastie C, Redman C, Vatish M. Placental syncytiotrophoblast-derived extracellular vesicles carry active NEP (Neprilysin) and are increased in preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2019;73(5):1112–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li H, Ouyang Y, Sadovsky E, Parks WT, Chu T, Sadovsky Y. Unique microRNA signals in plasma exosomes from pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2020;75(3):762–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miranda J, Paules C, Nair S, Lai A, Palma C, Scholz-Romero K, Rice GE, Gratacos E, Crispi F, Salomon C. Placental exosomes profile in maternal and fetal circulation in intrauterine growth restriction - Liquid biopsies to monitoring fetal growth. Placenta. 2018;6434–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feng Z, Hensley L, Mcknight KL, Hu F, Madden V, Ping L, Jeong SH, Walker C, Lanford RE, Lemon SM. A pathogenic picornavirus acquires an envelope by hijacking cellular membranes. Nature. 2013;496(7445):367–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramakrishnaiah V, Thumann C, Fofana I, Habersetzer F, Pan Q, De Ruiter PE, Willemsen R, Demmers JA, Stalin Raj V, Jenster G, Kwekkeboom J, Tilanus HW, Haagmans BL, Baumert TF, Van Der Laan LJ. Exosome-mediated transmission of hepatitis C virus between human hepatoma Huh7.5 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(32):13109–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pegtel DM, Cosmopoulos K, Thorley-Lawson DA, Van Eijndhoven MA, Hopmans ES, Lindenberg JL, De Gruijl TD, Wurdinger T, Middeldorp JM. Functional delivery of viral miRNAs via exosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(14):6328–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morita E, Sundquist WI. Retrovirus budding. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20395–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Colombo M, Raposo G, Thery C. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30255–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ostrowski M, Carmo NB, Krumeich S, Fanget I, Raposo G, Savina A, Moita CF, Schauer K, Hume AN, Freitas RP, Goud B, Benaroch P, Hacohen N, Fukuda M, Desnos C, Seabra MC, Darchen F, Amigorena S, Moita LF, Thery C. Rab27a and Rab27b control different steps of the exosome secretion pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(1):19–30; sup pp 1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jahn R, Sudhof TC. Membrane fusion and exocytosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68863–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baietti MF, Zhang Z, Mortier E, Melchior A, Degeest G, Geeraerts A, Ivarsson Y, Depoortere F, Coomans C, Vermeiren E, Zimmermann P, David G. Syndecan-syntenin-ALIX regulates the biogenesis of exosomes. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(7):677–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trajkovic K, Hsu C, Chiantia S, Rajendran L, Wenzel D, Wieland F, Schwille P, Brugger B, Simons M. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science. 2008;319(5867):1244–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Babst M MVB vesicle formation: ESCRT-dependent, ESCRT-independent and everything in between. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23(4):452–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stern-Ginossar N, Elefant N, Zimmermann A, Wolf DG, Saleh N, Biton M, Horwitz E, Prokocimer Z, Prichard M, Hahn G, Goldman-Wohl D, Greenfield C, Yagel S, Hengel H, Altuvia Y, Margalit H, Mandelboim O. Host immune system gene targeting by a viral miRNA. Science. 2007;317(5836):376–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bennasser Y, Le SY, Yeung ML, Jeang KT. HIV-1 encoded candidate micro-RNAs and their cellular targets. Retrovirology. 2004;143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kincaid RP, Sullivan CS. Virus-encoded microRNAs: An overview and a look to the future. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(12):e1003018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang L, Zhang S, Yao J, Lowery FJ, Zhang Q, Huang WC, Li P, Li M, Wang X, Zhang C, Wang H, Ellis K, Cheerathodi M, Mccarty JH, Palmieri D, Saunus J, Lakhani S, Huang S, Sahin AA, Aldape KD, Steeg PS, Yu D. Microenvironment-induced PTEN loss by exosomal microRNA primes brain metastasis outgrowth. Nature. 2015;527(7576):100–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bartel DP. Metazoan microRNAs. Cell. 2018;173(1):20–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferrero D, Ferrer-Orta C, Verdaguer N. Viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases: A structural overview. Subcell Biochem. 2018;8839–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Deeks SG, Overbaugh J, Phillips A, Buchbinder S. HIV infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;115035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hoshino A, Costa-Silva B, Shen TL, Rodrigues G, Hashimoto A, Tesic Mark M, Molina H, Kohsaka S, Di Giannatale A, Ceder S, Singh S, Williams C, Soplop N, Uryu K, Pharmer L, King T, Bojmar L, Davies AE, Ararso Y, Zhang T, Zhang H, Hernandez J, Weiss JM, Dumont-Cole VD, Kramer K, Wexler LH, Narendran A, Schwartz GK, Healey JH, Sandstrom P, Labori KJ, Kure EH, Grandgenett PM, Hollingsworth MA, De Sousa M, Kaur S, Jain M, Mallya K, Batra SK, Jarnagin WR, Brady MS, Fodstad O, Muller V, Pantel K, Minn AJ, Bissell MJ, Garcia BA, Kang Y, Rajasekhar VK, Ghajar CM, Matei I, Peinado H, Bromberg J, Lyden D. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature. 2015;527(7578):329–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sorkin A Cargo recognition during clathrin-mediated endocytosis: A team effort. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16(4):392–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Parton RG. Caveolae: Structure, function, and relationship to disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2018;34111–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Campadelli-Fiume G, Menotti L, Avitabile E, Gianni T. Viral and cellular contributions to herpes simplex virus entry into the cell. Curr Opin Virol. 2012;2(1):28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vargas A, Zhou S, Ethier-Chiasson M, Flipo D, Lafond J, Gilbert C, Barbeau B. Syncytin proteins incorporated in placenta exosomes are important for cell uptake and show variation in abundance in serum exosomes from patients with preeclampsia. Faseb j. 2014;28(8):3703–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tolosa JM, Schjenken JE, Clifton VL, Vargas A, Barbeau B, Lowry P, Maiti K, Smith R. The endogenous retroviral envelope protein syncytin-1 inhibits LPS/PHA-stimulated cytokine responses in human blood and is sorted into placental exosomes. Placenta. 2012;33(11):933–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mercer J, Schelhaas M, Helenius A. Virus entry by endocytosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79803–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Morizono K, Xie Y, Olafsen T, Lee B, Dasgupta A, Wu AM, Chen IS. The soluble serum protein Gas6 bridges virion envelope phosphatidylserine to the TAM receptor tyrosine kinase Axl to mediate viral entry. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9(4):286–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Helenius A Virus entry: Looking back and moving forward. J Mol Biol. 2018;430(13):1853–1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miyauchi K, Kim Y, Latinovic O, Morozov V, Melikyan GB. HIV enters cells via endocytosis and dynamin-dependent fusion with endosomes. Cell. 2009;137(3):433–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meertens L, Labeau A, Dejarnac O, Cipriani S, Sinigaglia L, Bonnet-Madin L, Le Charpentier T, Hafirassou ML, Zamborlini A, Cao-Lormeau VM, Coulpier M, Misse D, Jouvenet N, Tabibiazar R, Gressens P, Schwartz O, Amara A. Axl mediates ZIKA virus entry in human glial cells and modulates innate immune responses. Cell Rep. 2017;18(2):324–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hackett BA, Cherry S. Flavivirus internalization is regulated by a size-dependent endocytic pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(16):4246–4251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mercer J, Helenius A. Virus entry by macropinocytosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(5):510–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Heusermann W, Hean J, Trojer D, Steib E, Von Bueren S, Graff-Meyer A, Genoud C, Martin K, Pizzato N, Voshol J, Morrissey DV, Andaloussi SE, Wood MJ, Meisner-Kober NC. Exosomes surf on filopodia to enter cells at endocytic hot spots, traffic within endosomes, and are targeted to the ER. J Cell Biol. 2016;213(2):173–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li H, Pinilla-Macua I, Ouyang Y, Sadovsky E, Kajiwara K, Sorkin A, Sadovsky Y. Internalization of trophoblastic small extracellular vesicles and detection of their miRNA cargo in P-bodies. J Extracell Vesicles. 2020;9(1):1812261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Blijleven JS, Boonstra S, Onck PR, Van Der Giessen E, Van Oijen AM. Mechanisms of influenza viral membrane fusion. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016;6078–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen B Molecular mechanism of HIV-1 entry. Trends Microbiol. 2019;27(10):878–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Margolis L, Sadovsky Y. The biology of extracellular vesicles: The known unknowns. PLoS Biol. 2019;17(7):e3000363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Buchrieser J, Degrelle SA, Couderc T, Nevers Q, Disson O, Manet C, Donahue DA, Porrot F, Hillion KH, Perthame E, Arroyo MV, Souquere S, Ruigrok K, Dupressoir A, Heidmann T, Montagutelli X, Fournier T, Lecuit M, Schwartz O. IFITM proteins inhibit placental syncytiotrophoblast formation and promote fetal demise. Science. 2019;365(6449):176–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brass AL, Huang IC, Benita Y, John SP, Krishnan MN, Feeley EM, Ryan BJ, Weyer JL, Van Der Weyden L, Fikrig E, Adams DJ, Xavier RJ, Farzan M, Elledge SJ. The IFITM proteins mediate cellular resistance to influenza A H1N1 virus, West Nile virus, and dengue virus. Cell. 2009;139(7):1243–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bailey CC, Zhong G, Huang IC, Farzan M. IFITM-Family Proteins: The Cell’s First Line of Antiviral Defense. Annu Rev Virol. 2014;1261–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Savidis G, Perreira JM, Portmann JM, Meraner P, Guo Z, Green S, Brass AL. The IFITMs Inhibit Zika Virus Replication. Cell Rep. 2016;15(11):2323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Spence JS, He R, Hoffmann HH, Das T, Thinon E, Rice CM, Peng T, Chandran K, Hang HC. IFITM3 directly engages and shuttles incoming virus particles to lysosomes. Nat Chem Biol. 2019;15(3):259–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhu X, He Z, Yuan J, Wen W, Huang X, Hu Y, Lin C, Pan J, Li R, Deng H, Liao S, Zhou R, Wu J, Li J, Li M. IFITM3-containing exosome as a novel mediator for anti-viral response in dengue virus infection. Cell Microbiol. 2015;17(1):105–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Miyagi E, Opi S, Takeuchi H, Khan M, Goila-Gaur R, Kao S, Strebel K. Enzymatically active APOBEC3G is required for efficient inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2007;81(24):13346–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yu X, Yu Y, Liu B, Luo K, Kong W, Mao P, Yu XF. Induction of APOBEC3G ubiquitination and degradation by an HIV-1 Vif-Cul5-SCF complex. Science. 2003;302(5647):1056–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sheehy AM, Gaddis NC, Malim MH. The antiretroviral enzyme APOBEC3G is degraded by the proteasome in response to HIV-1 Vif. Nat Med. 2003;9(11):1404–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Conticello SG, Harris RS, Neuberger MS. The Vif protein of HIV triggers degradation of the human antiretroviral DNA deaminase APOBEC3G. Curr Biol. 2003;13(22):2009–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Khatua AK, Taylor HE, Hildreth JE, Popik W. Exosomes packaging APOBEC3G confer human immunodeficiency virus resistance to recipient cells. J Virol. 2009;83(2):512–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schoggins JW. Interferon-stimulated genes: What do they all do? Annu Rev Virol. 2019;6(1):567–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yao Z, Jia X, Megger DA, Chen J, Liu Y, Li J, Sitek B, Yuan Z. Label-free proteomic analysis of exosomes secreted from THP-1-derived macrophages treated with IFN-alpha identifies antiviral proteins enriched in exosomes. J Proteome Res. 2019;18(3):855–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang J, Teng Y, Zhao G, Li F, Hou A, Sun B, Kong W, Gao F, Cai L, Jiang C. Exosome-mediated delivery of inducible miR-423-5p enhances resistance of MRC-5 cells to rabies virus infection. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Welch JL, Kaddour H, Schlievert PM, Stapleton JT, Okeoma CM. Semen Exosomes promote transcriptional silencing of HIV-1 by disrupting NF-kappaB/Sp1/Tat circuitry. J Virol. 2018;92(21). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nahui Palomino RA, Vanpouille C, Laghi L, Parolin C, Melikov K, Backlund P, Vitali B, Margolis L. Extracellular vesicles from symbiotic vaginal lactobacilli inhibit HIV-1 infection of human tissues. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):5656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schwab A, Meyering SS, Lepene B, Iordanskiy S, Van Hoek ML, Hakami RM, Kashanchi F. Extracellular vesicles from infected cells: Potential for direct pathogenesis. Front Microbiol. 2015;61132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gould SJ, Booth AM, Hildreth JE. The Trojan exosome hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(19):10592–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Santiana M, Ghosh S, Ho BA, Rajasekaran V, Du WL, Mutsafi Y, De Jesus-Diaz DA, Sosnovtsev SV, Levenson EA, Parra GI, Takvorian PM, Cali A, Bleck C, Vlasova AN, Saif LJ, Patton JT, Lopalco P, Corcelli A, Green KY, Altan-Bonnet N. Vesicle-cloaked virus clusters are optimal units for inter-organismal viral transmission. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;24(2):208–220.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chen YH, Du W, Hagemeijer MC, Takvorian PM, Pau C, Cali A, Brantner CA, Stempinski ES, Connelly PS, Ma HC, Jiang P, Wimmer E, Altan-Bonnet G, Altan-Bonnet N. Phosphatidylserine vesicles enable efficient en bloc transmission of enteroviruses. Cell. 2015;160(4):619–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Van Der Grein SG, Defourny KaY, Rabouw HH, Galiveti CR, Langereis MA, Wauben MHM, Arkesteijn GJA, Van Kuppeveld FJM, Nolte-’T Hoen ENM. Picornavirus infection induces temporal release of multiple extracellular vesicle subsets that differ in molecular composition and infectious potential. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15(2):e1007594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pinto DO, Demarino C, Pleet ML, Cowen M, Branscome H, Al Sharif S, Jones J, Dutartre H, Lepene B, Liotta LA, Mahieux R, Kashanchi F. HTLV-1 extracellular vesicles promote cell-to-cell contact. Front Microbiol. 2019;102147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ahsan NA, Sampey GC, Lepene B, Akpamagbo Y, Barclay RA, Iordanskiy S, Hakami RM, Kashanchi F. Presence of viral RNA and proteins in exosomes from cellular clones resistant to rift valley fever virus infection. Front Microbiol. 2016;7139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Arenaccio C, Chiozzini C, Columba-Cabezas S, Manfredi F, Affabris E, Baur A, Federico M. Exosomes from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected cells license quiescent CD4+ T lymphocytes to replicate HIV-1 through a Nef- and ADAM17-dependent mechanism. J Virol. 2014;88(19):11529–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mcnamara RP, Chugh PE, Bailey A, Costantini LM, Ma Z, Bigi R, Cheves A, Eason AB, Landis JT, Host KM, Xiong J, Griffith JD, Damania B, Dittmer DP. Extracellular vesicles from Kaposi Sarcoma-associated herpesvirus lymphoma induce long-term endothelial cell reprogramming. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15(2):e1007536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mukhamedova N, Hoang A, Dragoljevic D, Dubrovsky L, Pushkarsky T, Low H, Ditiatkovski M, Fu Y, Ohkawa R, Meikle PJ, Horvath A, Brichacek B, Miller YI, Murphy A, Bukrinsky M, Sviridov D. Exosomes containing HIV protein Nef reorganize lipid rafts potentiating inflammatory response in bystander cells. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15(7):e1007907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gao L, Wang L, Dai T, Jin K, Zhang Z, Wang S, Xie F, Fang P, Yang B, Huang H, Van Dam H, Zhou F, Zhang L. Tumor-derived exosomes antagonize innate antiviral immunity. Nat Immunol. 2018;19(3):233–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pereira L Congenital viral infection: Traversing the uterine-placental interface. Annu Rev Virol. 2018;5(1):273–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kourtis AP, Read JS, Jamieson DJ. Pregnancy and infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2211–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Arora N, Sadovsky Y, Dermody TS, Coyne CB. Microbial vertical transmission during human pregnancy. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;21(5):561–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bayer A, Lennemann NJ, Ouyang Y, Bramley JC, Morosky S, Marques ET Jr., Cherry S, Sadovsky Y, Coyne CB. Type III interferons produced by human placental trophoblasts confer protection against Zika virus infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19(5):705–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tabata T, Petitt M, Puerta-Guardo H, Michlmayr D, Wang C, Fang-Hoover J, Harris E, Pereira L. Zika virus targets different primary human placental cells, suggesting two routes for vertical transmission. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20(2):155–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Quicke KM, Bowen JR, Johnson EL, Mcdonald CE, Ma H, O’neal JT, Rajakumar A, Wrammert J, Rimawi BH, Pulendran B, Schinazi RF, Chakraborty R, Suthar MS. Zika virus infects human placental macrophages. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20(1):83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Jordan JA, Deloia JA. Globoside expression within the human placenta. Placenta. 1999;20(1):103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Weigel-Kelley KA, Yoder MC, Srivastava A. Alpha5beta1 integrin as a cellular coreceptor for human parvovirus B19: requirement of functional activation of beta1 integrin for viral entry. Blood. 2003;102(12):3927–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Munakata Y, Saito-Ito T, Kumura-Ishii K, Huang J, Kodera T, Ishii T, Hirabayashi Y, Koyanagi Y, Sasaki T. Ku80 autoantigen as a cellular coreceptor for human parvovirus B19 infection. Blood. 2005;106(10):3449–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Fisher S, Genbacev O, Maidji E, Pereira L. Human cytomegalovirus infection of placental cytotrophoblasts in vitro and in utero: Implications for transmission and pathogenesis. J Virol. 2000;74(15):6808–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Maidji E, Mcdonagh S, Genbacev O, Tabata T, Pereira L. Maternal antibodies enhance or prevent cytomegalovirus infection in the placenta by neonatal Fc receptor-mediated transcytosis. Am J Pathol. 2006;168(4):1210–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Tabata T, Petitt M, Zydek M, Fang-Hoover J, Larocque N, Tsuge M, Gormley M, Kauvar LM, Pereira L. Human cytomegalovirus infection interferes with the maintenance and differentiation of trophoblast progenitor cells of the human placenta. J Virol. 2015;89(9):5134–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Weisblum Y, Panet A, Zakay-Rones Z, Haimov-Kochman R, Goldman-Wohl D, Ariel I, Falk H, Natanson-Yaron S, Goldberg MD, Gilad R, Lurain NS, Greenfield C, Yagel S, Wolf DG. Modeling of human cytomegalovirus maternal-fetal transmission in a novel decidual organ culture. J Virol. 2011;85(24):13204–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Tabata T, Petitt M, Fang-Hoover J, Zydek M, Pereira L. Persistent cytomegalovirus infection in amniotic membranes of the human placenta. Am J Pathol. 2016;186(11):2970–2986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Si HR, Zhu Y, Li B, Huang CL, Chen HD, Chen J, Luo Y, Guo H, Jiang RD, Liu MQ, Chen Y, Shen XR, Wang X, Zheng XS, Zhao K, Chen QJ, Deng F, Liu LL, Yan B, Zhan FX, Wang YY, Xiao GF, Shi ZL. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Kruger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, Schiergens TS, Herrler G, Wu NH, Nitsche A, Muller MA, Drosten C, Pohlmann S. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–280.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Valdes G, Neves LA, Anton L, Corthorn J, Chacon C, Germain AM, Merrill DC, Ferrario CM, Sarao R, Penninger J, Brosnihan KB. Distribution of angiotensin-(1-7) and ACE2 in human placentas of normal and pathological pregnancies. Placenta. 2006;27(2-3):200–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Li M, Chen L, Zhang J, Xiong C, Li X. The SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 expression of maternal-fetal interface and fetal organs by single-cell transcriptome study. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0230295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Breslin N, Baptiste C, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Miller R, Martinez R, Bernstein K, Ring L, Landau R, Purisch S, Friedman AM, Fuchs K, Sutton D, Andrikopoulou M, Rupley D, Sheen JJ, Aubey J, Zork N, Moroz L, Mourad M, Wapner R, Simpson LL, D’alton ME, Goffman D. COVID-19 infection among asymptomatic and symptomatic pregnant women: Two weeks of confirmed presentations to an affiliated pair of New York City hospitals. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;100118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Karimi-Zarchi M, Neamatzadeh H, Dastgheib SA, Abbasi H, Mirjalili SR, Behforouz A, Ferdosian F, Bahrami R. Vertical transmission of coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) from Infected pregnant mothers to neonates: A review. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2020;1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zaigham M, Andersson O. Maternal and perinatal outcomes with COVID-19: A systematic review of 108 pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lamers MM, Beumer J, Van Der Vaart J, Knoops K, Puschhof J, Breugem TI, Ravelli RBG, Paul Van Schayck J, Mykytyn AZ, Duimel HQ, Van Donselaar E, Riesebosch S, Kuijpers HJH, Schippers D, Van De Wetering WJ, De Graaf M, Koopmans M, Cuppen E, Peters PJ, Haagmans BL, Clevers H. SARS-CoV-2 productively infects human gut enterocytes. Science. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Koi H, Zhang J, Makrigiannakis A, Getsios S, Maccalman CD, Strauss JF 3rd, Parry S. Syncytiotrophoblast is a barrier to maternal-fetal transmission of herpes simplex virus. Biol Reprod. 2002;67(5):1572–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Delorme-Axford E, Sadovsky Y, Coyne CB. The placenta as a barrier to viral infections. Annu Rev Virol. 2014;1(1):133–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Delorme-Axford E, Donker RB, Mouillet JF, Chu T, Bayer A, Ouyang Y, Wang T, Stolz DB, Sarkar SN, Morelli AE, Sadovsky Y, Coyne CB. Human placental trophoblasts confer viral resistance to recipient cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(29):12048–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Bayer A, Delorme-Axford E, Sleigher C, Frey TK, Trobaugh DW, Klimstra WB, Emert-Sedlak LA, Smithgall TE, Kinchington PR, Vadia S, Seveau S, Boyle JP, Coyne CB, Sadovsky Y. Human trophoblasts confer resistance to viruses implicated in perinatal infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(1):71.e1–71.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Deretic V, Saitoh T, Akira S. Autophagy in infection, inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(10):722–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Donker RB, Mouillet JF, Chu T, Hubel CA, Stolz DB, Morelli AE, Sadovsky Y. The expression profile of C19MC microRNAs in primary human trophoblast cells and exosomes. Mol Hum Reprod. 2012;18(8):417–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Dumont TMF, Mouillet JF, Bayer A, Gardner CL, Klimstra WB, Wolf DG, Yagel S, Balmir F, Binstock A, Sanfilippo JS, Coyne CB, Larkin JC, Sadovsky Y. The expression level of C19MC miRNAs in early pregnancy and in response to viral infection. Placenta. 2017;5323–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Bayer A, Lennemann NJ, Ouyang Y, Sadovsky E, Sheridan MA, Roberts RM, Coyne CB, Sadovsky Y. Chromosome 19 microRNAs exert antiviral activity independent from type III interferon signaling. Placenta. 2018;6133–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Chang G, Mouillet JF, Mishima T, Chu T, Sadovsky E, Coyne CB, Parks WT, Surti U, Sadovsky Y. Expression and trafficking of placental microRNAs at the feto-maternal interface. Faseb j. 2017;31(7):2760–2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Mulcahy LA, Pink RC, Carter DR. Routes and mechanisms of extracellular vesicle uptake. J Extracell Vesicles. 2014;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Wang P The opening of Pandora’s box: An emerging role of long noncoding RNA in viral infections. Front Immunol. 2018;93138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Chang Z, Wang Y, Zhou X, Long JE. STAT3 roles in viral infection: antiviral or proviral? Future Virol. 2018;13(8):557–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Barriocanal M, Fortes P. Long non-coding RNAs in hepatitis C virus-infected cells. Front Microbiol. 2017;81833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Heusinger E, Kirchhoff F. Primate lentiviruses modulate NF-kappaB activity by multiple mechanisms to fine-tune viral and cellular gene expression. Front Microbiol. 2017;8198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Demarino C, Barclay RA, Pleet ML, Pinto DO, Branscome H, Paul S, Lepene B, El-Hage N, Kashanchi F. Purification of high yield extracellular vesicle preparations away from virus. J Vis Exp. 2019;(151). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Heider S, Muzard J, Zaruba M, Metzner C. Integrated method for purification and single-particle characterization of lentiviral vector systems by size exclusion chromatography and tunable resistive pulse sensing. Mol Biotechnol. 2017;59(7):251–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]