Summary

Sentinel species are playing an indispensable role in monitoring environmental pollution in aquatic ecosystems. Many pollutants found in water prove to be endocrine disrupting chemicals that could cause disruptions in lipid homeostasis in aquatic species. A comprehensive profiling of the lipidome of these species is thus an essential step toward understanding the mechanism of toxicity induced by pollutants. Both the composition and spatial distribution of lipids in freshwater crustacean Gammarus fossarum were extensively examined herein. The baseline lipidome of gammarids of different sex and reproductive stages was established by high throughput shotgun lipidomics. Spatial lipid mapping by high resolution mass spectrometry imaging led to the discovery of sulfate-based lipids in hepatopancreas and their accumulation in mature oocytes. A diverse and dynamic lipid composition in G. fossarum was uncovered, which deepens our understanding of the biochemical changes during development and which could serve as a reference for future ecotoxicological studies.

Subject Areas: Environmental Science, Lipidomics, Metabolomics, Pollution, Zoology

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Baseline lipidome profiling of G. fossarum of different sex and reproductive stages

-

•

Spatial localization of lipids in gammarid tissue by mass spectrometry imaging

-

•

SIMS imaging guided discovery of sulfate-based lipids in hepatopancreas epithelium

-

•

Disclosure of a dynamic lipid composition in maturing female oocytes

Environmental Science; Lipidomics; Metabolomics; Pollution; Zoology

Introduction

Lipids are a structurally diverse group of molecules that can be classified into several categories, including fatty acyls, glycerolipids, glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, sterol lipids, prenol lipids, saccharolipids, and polyketides, according to the LIPID MAPS (Lipid Metabolites and Pathways Strategy) lipid classification system (Fahy, et al., 2011; Fahy, et al., 2005; Fahy, et al., 2009). Besides their basic function as building blocks of the cell membrane, lipids are involved in essential biofunctions, including signaling and energy storage that mediate cell growth, reproduction, and so on (Dutta and Sinha, 2017; Obeid, et al., 1993; van Meer, 2005; van Meer, et al., 2008). Lipid homeostasis in the organisms is extremely crucial for their development, maintenance, and reproduction (De Mendoza and Pilon, 2019; Klose, et al., 2012; Zhang and Rock, 2008). However, this homeostasis can be disrupted when the organism is subjected to threats from environmental stressors. As a result of anthropogenic activities, especially the intense use of chemical products, various kinds of pollutants are continuously released into the aquatic environment. Increasing evidence has shown that some of these pollutants are endocrine disrupting chemicals, also referred to as obesogens, which could interfere lipid homeostasis and cause toxic effects on a number of aquatic animal species (Capitao, et al., 2017; Fuertes, et al., 2020). Therefore, it is highly desirable to get retrospective and prospective comprehensive profiles of the lipidome in sentinel organisms in order to understand which, and how, the lipid species could be altered by chemical pollutants and to further assess the ecological risk incurred by the contaminated aquatic environment.

Freshwater sentinel species Gammarus fossarum is one of the most represented amphipod crustaceans widespread across European inland aquatic habitats (Wattier, et al., 2020). Its broad distribution and sensitivity to a wide range of contaminants has made this keystone species a valuable model organism in ecotoxicology (Besse, et al., 2013; Chaumot, et al., 2015; Dedourge-Geffard, et al., 2009; Kunz, et al., 2010; Mehennaoui, et al., 2016; Wigh, et al., 2017). Endocrine effects (e.g., accelerated oocyte maturation, smaller vitellogenic oocytes, and decreased spermatozoon production) have also been observed in this species when exposed to endocrine disrupting chemicals in wastewater effluents (Schirling, et al., 2005; Trapp, et al., 2015) and in laboratory experiments (Schirling, et al., 2005; Trapp, et al., 2015). It is thus of great interest to characterize the lipidome of this organism to understand the molecular mechanism underlying these endocrine effects and to develop biomarkers for early stage risk assessment of obesogen contamination in freshwater systems. Initial assessment of lipid perturbation in Gammarus fossarum exposed to a growth regulator insecticide has been recently reported (Arambourou, et al., 2018). However, only a limited number of lipid classes and molecular species in this non-model organism have been described (Arambourou, et al., 2018; Fu, et al., 2020; Kolanowski, et al., 2007). Our knowledge about the lipid composition, especially the associated dynamics, in this species is scarce.

Lipidomics per se covers a broad range of mass spectrometry (MS) workflows that aim to identify and quantify a great variety of lipid classes, including their molecular species in biological systems (Hsu, 2018; Hu, et al., 2019; Klose, et al., 2013; Shevchenko and Simons, 2010; van Meer, 2005; Wenk, 2005). In addition, when required, advanced lipid structural characterization (e.g., double bond and sn-positions) is also readily achievable via MS-related developments, such as ozonolysis (Brown, et al., 2011), UV-induced photodissociation (Bowman, et al., 2017; Brown, et al., 2011; Ryan, et al., 2017; Williams, et al., 2017), and ion mobility spectrometry (Groessl, et al., 2015; Jackson, et al., 2008; Kim, et al., 2009; Leaptrot, et al., 2019). The most popular analytical platforms for lipidomic analysis are electrospray ionization (ESI)-MS-based shotgun lipidomics (i.e., direct infusion MS) and liquid chromatography (LC)-MS. In contrast to the necessity of time-consuming chromatography separation in LC-MS, shotgun lipidomics is a high-throughput approach which relies on the direct infusion of a crude lipid extract into the ion source of a mass spectrometer (Han and Gross, 2003, 2005a, 2005b; Hsu, 2018). The maintenance of a constant concentration of the delivered lipid extract provides a stable ionization environment, thus enabling reproducible qualitative and quantitative detection of hundreds of molecular lipid species in a single run. Nowadays, high-resolution MS (e.g., Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance and Orbitrap) is frequently used in shotgun lipidomics and has tremendously increased the confidence of analysis with its capability of resolving isobaric lipid species (Zullig and Kofeler, 2020). Up to now, shotgun lipidomics has been successfully applied to describe the lipidome of a variety of biological systems like yeast cells (Ejsing, et al., 2009; Klose, et al., 2012), Drosophila (Carvalho, et al., 2012; Palm, et al., 2012), flatworm (Thommen, et al., 2019), nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (Harvald, et al., 2017; Penkov, et al., 2010), and freshwater crustacean Daphnia magna (Taylor, et al., 2017).

Despite the access of the molecular complexity and the identification of hundreds to thousands of chemical species offered by shotgun lipidomics, the spatial distribution of the measured molecular lipid species is missing due to the mandatory lipid extraction procedures. Even though a global evaluation of lipid content in an organism proves to be very valuable for studying the lipid metabolism variations associated with development or disease (Ayciriex, et al., 2017; Carvalho, et al., 2012; Guan, et al., 2013; Knittelfelder, et al., 2018; Wang, et al., 2020), the spatial distribution of these biomolecules is crucial to understand their modes of action, in particular functional compartments. In the last two decades, MS imaging (MSI) has emerged as a novel tool to localize various molecules such as metabolites, lipids, drugs, and so on in biological tissues without the need of labeling (Davoli, et al., 2020; McDonnell and Heeren, 2007; Spengler, 2015). By using a laser or an ion beam to generate ions directly from the tissue, MSI preserves the spatial localization of the ions and enables multiplexed molecular mapping of important structures in tissue sections. Among the various MSI techniques, secondary ion MS (SIMS) is well recognized for its high spatial resolving power, providing a micron or even submicron routine resolution (Ayciriex, et al., 2011; Benabdellah, et al., 2010; Touboul and Brunelle, 2016). Therefore, SIMS remains popular in biological imaging despite the severe molecular fragmentation due to the employment of energetic primary ion beams. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI), on the other hand, enables intact molecular detection with a good spatial resolution, typically >10 μm (Benabdellah, et al., 2010; Gessel, et al., 2014). Both SIMS and MALDI MS imaging techniques have been intensively employed for lipid mapping (Bich, et al., 2014; Djambazova, et al., 2020; Sämfors and Fletcher, 2020; Zemski Berry, et al., 2011).

With the aim to provide an exhaustive characterization of the lipidome of freshwater sentinel species G. fossarum and to disclose the lipid dynamics during the development, we performed shotgun lipidomics and MSI on gammarids of different gender and distinct female reproductive stages. The baseline lipidome of this organism was defined by high-throughput shotgun lipidomics using a robotic chip-based nano-ESI infusion device coupled to a high-resolution mass spectrometer. To reveal the in situ localization of a variety of lipids in the organs and tissues, gammarid tissue sections were examined globally by MALDI MSI and scrutinized in detail by time-of-flight (TOF)-SIMS imaging. Several unknown sulfate-based lipids were uncovered in this organism and localized in the epithelium of hepatopancreas (HP) by high-resolution SIMS imaging, which subsequently guided the targeted high mass resolution analysis of HP lipid extract for molecular identification and structural characterization. Dynamic distribution of these sulfate-based lipids in the course of reproduction or oocyte maturation was then investigated by mapping the oocytes of female gammarids at two different reproductive stages. Overall, our results provide both compositional and spatial information of the lipids in this crustacean species.

Results and discussion

Lipid composition of the Gammarus fossarum lipidome

Shotgun lipidomics analyses via high-resolution MS in positive and negative ion modes were conducted to decipher the lipidome of males and females of the freshwater crustacean G. fossarum and at specific female reproductive stages (Figure S1). The reproduction cycle of female gammarids (oogenesis/vitellogenesis, embryogenesis) is closely synchronized with molting and is now well characterized (Chaumot, et al., 2020; Geffard, et al., 2010; Schirling, et al., 2004). In total, six molt stages are defined according to the phenotypic features of the females, namely postmolt (A, B), intermolt (C1, C2), and premolt (D1, D2). Postmolt stage A is very short, lasts approximately one day (Chaumot, et al., 2020) and can be grouped with stage B as one stage, the AB stage, which involves the hardening of the cuticle. At this stage, the oocytes contain very few lipid globules and yolk vesicles. Intermolt stages C1 and C2 are characterized by an epidermal retraction from the cuticle, which constitutes a determination criterion of these stages based on integument morphogenesis observation of the periopod pairs in this species (Geffard, et al., 2010). The transition between C1 and C2 stage marks the onset of secondary vitellogenesis, the yolk vesicles and lipid globules in the oocytes increase drastically in both number and size. Finally, at premolt stages D1 and D2, a new cuticle is generated before the molting. The histological features of the oocytes at these stages are very similar to those at C2 stage. Along with the phenotypic development, an accumulation of vitellogenin, the key protein involved in reproduction, has been observed throughout the reproductive cycle, and the biggest increases occur from C1 to C2 and C2 to D1 (Jubeaux, et al., 2012). Contrary to females, spermatogenesis in male gammarids is not related to the molting cycle, and morphological parameters are not available to depict accurately the organisms at different spermatogenesis stages. In this study, all the male organisms sampled were in amplexus to ensure they were at similar spermatogenesis stage (mature). Female gammarids were collected at the beginning of intermolt stage (C1) and at premolt stage (D1) to investigate lipid alterations related to oocyte maturation.

By shotgun lipidomics, more than 200 molecular lipid species were quantified, corresponding to 11 major lipid classes in wild male and female adult gammarids – triacylglycerols (TAGs), diacylglycerols, phosphatidylcholines (PCs), phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs), ether lipids (PE-O and PC-O), phosphatidylinositols (PIs), lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs), lysophosphatidylethanolamines (LPEs), sphingomyelins (SMs), and cholesterol (Figure 1A and Data S1). Our findings have significantly expanded the lipidome coverage reported previously in G. fossarum in terms of both lipid class and molecular lipid species (Arambourou, et al., 2018). Total fatty acids (FAs), including the acyl chains of larger lipid molecules from the whole organism, were also examined and deciphered by gas chromatography with flame ionization detector (GC-FID) (Figure S2). The predominant fatty acid in gammarids was monounsaturated C18:1 (∼33%). Other FAs of comparatively high level were saturated C16:0 (∼16%), polyunsaturated C20:5 n-3 (∼14%), and monounsaturated C16:1 (∼13%). Omega-3 FAs made up ∼25% of the polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) in contrast of omega-6 PUFA (∼9%). The main n-3 FA was eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5, n-3), followed by α-linolenic acid (FA 18:3, n-3).

Figure 1.

Lipid composition of the Gammarus fossarum lipidome

(A) Lipid classes identified in G. fossarum organism with the associated number of lipid species identified. Comparison of the different lipid profile between male and female gammarids at specific female reproductive stages (C1 versus D1).

(B) TAG profile.

(C) Cholesterol, phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, and ether lipid distribution.

(D) Lysophospholipid, phosphatidylinositol, and sphingomyelin profile. Lipid class abundance is presented as moles per mole of total membrane lipid (phospholipids, sphingolipids, and sterols – not including storage lipids). Significance was calculated by Student's t test, and statistically significant changes (∗∗∗p < 0.001) are marked by asterisks. Data are represented as mean +/− standard deviation.

The TAG class turned out to be the most predominant lipid class in gammarids. Interestingly, females at D1 stage contained more TAGs than females at C1 stage and males (Figure 1B), whereas no major changes were observed for membrane lipids like cholesterol, phospholipids (PC, PE, PE-O, PC-O, PI), lysophospholipids (LPE, LPC), and sphingomyelin (Figures 1C and 1D). In the reproductive cycle of female gammarids, D1 stage follows the second vitellogenesis where dramatically increased follicular surface has been observed compared to females at C1 postmolt stages (Geffard, et al., 2010). It is well documented that in many crustacean species, ovarian maturation requires huge amount of lipids to realize the vitellogenesis process (Alava, et al., 2007; Lee and Walker, 1995; Ravid, et al., 1999). In the female gammarids at D1 stage, TAG is predicted to serve as an energy storage reservoir (FA store) that might be rapidly mobilized on demand during the second vitellogenesis (Subramoniam, 2011). Although a global lipid accumulation during oocyte maturation is evident, the mostly affected stages and lipid species seem to differ among the crustacean species. Equal amounts of TAG and phospholipids are accumulated in the ovary of Penaeus semisulcatus when oocytes reach maturation (Ravid, et al., 1999). However, in most species, TAG is primarily responsible for the changes in total lipid content and increase of phospholipids only occurs at the end of maturation (Mourente, et al., 1994; Wouters, et al., 2001) as probably in the case of G. fossarum.

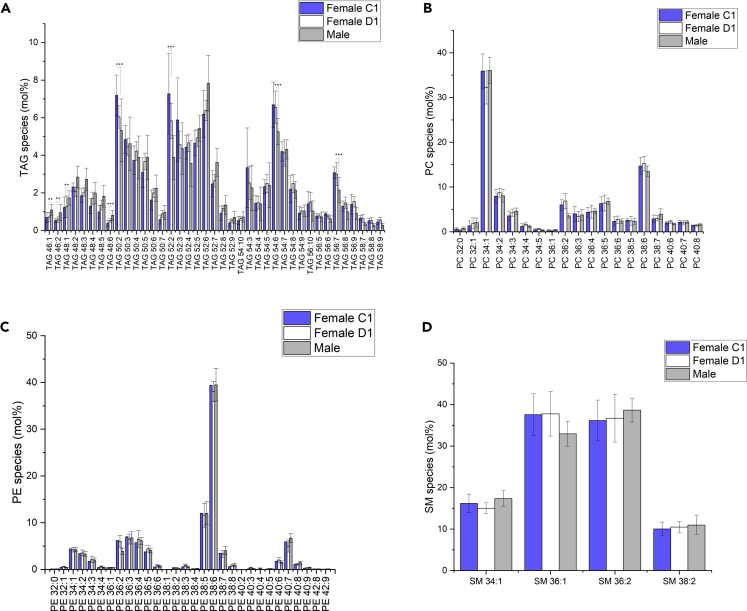

Diversity of molecular lipid species in G. fossarum across gender and distinct female reproductive stages

Next, we questioned whether the profile of the molecular lipid species of each lipid class found in adult gammarid varies between the gender and different female reproductive stages. Figure 2 displays the profiles of the molecular species of four lipid classes (namely TAG, PC, PE, and SM) in male gammarid and female gammarids at C1 and D1 stages. The abundance of each lipid was normalized to the total abundance of the corresponding lipid class to show the proportion of each molecular lipid species within a lipid class. It is observed that TAG species containing relatively short chain and PUFAs(e.g., TAG 46:1, TAG 46:2, and TAG 48:1 to TAG 48:6) have a higher proportion in males compared to females, whereas TAGs with longer chain and PUFAs are more prominent in females (e.g., TAG 54:6, TAG 56:7). This difference in the proportion of each molecular species in total TAG is less significant between the females at C1 and D1 reproductive stages. All the reported 46 TAG molecular species were characterized by tandem MS. TAG precursors were detected in positive ion mode as ammonium adduct [M + NH4]+, of which the MS/MS spectra were featured by neutral losses (NLs) of NH3 and an acyl side chain (as a carbolic acid ROOH) to generate a diacyl product ion (Figure S3). For instance, under higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD), the precursor ion at m/z 868.7416 (TAG 52:6, [M + NH4]+) exhibited NLs of 319, 271, 299, and 245 which correspond to FA 20:5, 16:1, 18:1, and 14:0, respectively. It was also revealed by MS/MS analysis that TAG 52:6 was composed of two isomers TAG 16:0-16:1-20:5 and 14:0-18:1-20:5 (Figure S3B).

Figure 2.

Diverse molecular lipid species in G. fossarum across gender and female reproductive stages

Lipid profile for the main glycerolipid (A) TAG and the two main phospholipid classes (B) PC and (C) PE. (D) Sphingomyelin profile. Note that for TAG profile only the species higher than 5 mol% are presented. Significance was calculated by Student's t test, and statistically significant changes (∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001) are marked by asterisks. Data are represented as mean +/− standard deviation.

For glycerophospholipid class, the predominant PC species in gammarids is monounsaturated PC 34:1, followed by the polyunsaturated PC 38:4 (Figure 2B). These two major PC species were defined as PC 16:0-18:1 and PC 18:1-20:5, respectively, based on the observation of the fragments corresponding to FAs in the negative MS/MS spectra (Figure S4). For PE lipid class, PE 38:6 (PE 18:1-20:5) stands out as the most abundant molecular lipid species (Figures 2C and S5). Only 4 SM species were detected in the gammarid, namely SM 34:1 (d18:1/16:0), 36:1 (d18:1/18:0), 36:2 (d18:1/18:1), and 38:2 (d18:1/20:1) (Figures 2D and S6). This finding was confirmed by a targeted lipidomics approach employing LC-ESI-MS/MS (data not shown). Overall, no significant differences in the proportional abundance of the glycerophosholipid and sphingolipid lipids were observed between male and female gammarid at the molecular species level.

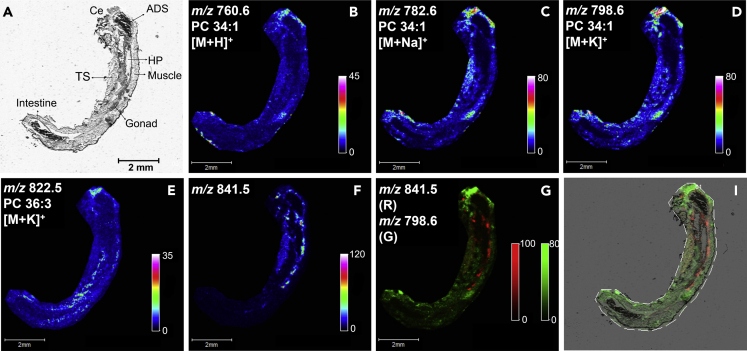

Localization of lipids in whole-body gammarid section by MALDI MSI

With the rich molecular lipid species information obtained with shotgun lipidomics, MSI was then performed to map the lipids in situ and reveal their spatial localization in the tissues and organs of G. fossarum. First, longitudinal sections of the male gammarid were mapped by MALDI MSI to examine the global distribution of the lipid species. In negative ion mode, the ions at m/z 295.2 and 297.2 were the main species detected from the tissue section (Figure S7), while in positive ion mode, PCs were the prominent lipid species observed in the mass range of m/z 750-850 (Figure S8). MALDI MS ion images of the main PC lipids, PC 34:1 and PC 36:3, are displayed in Figure 3. Both PC species are distributed across the whole body in cephalon, muscle, and thorax segments (TSs) with higher abundance in cephalon. PC 34:1 is the most abundant PC species according to the shotgun analysis (Figure 2). Three ions related to PC 34:1 ([M + H]+, [M + Na]+, and [M + K]+) were detected, all showing identical distribution in the cephalon, muscle, and TS tissue of the male gammarid. Besides the PC lipids, an ion at m/z 841.5 was also observed in the measured mass range (Figures 3F and S8). The ion image showed a distinct spatial localization from the PC lipids. By overlaying the ion image with that of PC 34:1 [M + K]+ and subsequently the optical image of the analyzed tissue section (Figures 3G and 3I), it is revealed that this molecule is principally colocalized to the gonad, as well as to the area close to HP where the gonad is usually located but not seen in the optical image due to the non-ideal cutting orientation during cryosectioning. This ion at m/z 841.5 was tentatively attributed as sulfated glyceroglycolipid (SGG), also referred to as seminolipid with C16:0/C16:0 alkyl/acyl chains (Lessig, et al., 2004).

Figure 3.

Localization of lipids in whole-body gammarid section by MALDI MSI

(A) Optical image of the whole-body tissue section of the male gammarid. Scale bar, 2mm.

(B) Ion image of protonated PC 34:1.

(C) Ion image of sodium adduct of PC 34:1.

(D) Ion image of potassium adduct of PC 34:1.

(E) Ion image of potassium adduct of PC 36:3.

(F) Ion image of the ion at m/z 841.5.

(G) Two-color overlay of the ion at m/z 841.5 and the potassium adduct of PC 34:1.

(I) Overlay of the two-color overlay image in G and the optical image. Ce: cephalon; ADS: anterior digestive system; HP: hepatopancreas; TS: thorax segments.

Seminolipid C16:0/16:0 is the predominant SGG species and is a key lipid involved in germ cell differentiation during spermatogenesis in mammalians (Tanphaichitr, et al., 2018; Zhang, et al., 2005), and it is likely to have similar function in G. fossarum. In the anatomy of male gammarid, the gonad is surrounded by orange lipid droplets (Wigh, et al., 2017). Therefore, it is unclear if this molecule detected here is derived from the gonad tissue or from the surrounding lipid droplets. The future work will be focusing on characterizing this seminolipid, discovering its potential analogs and identifying its precise localization.

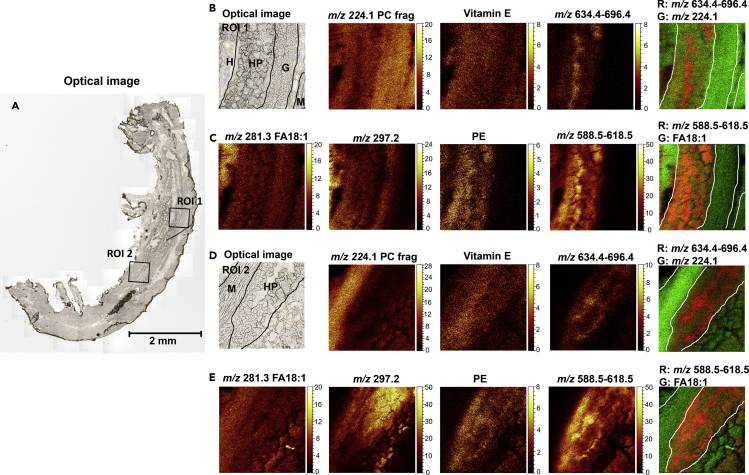

Lipid distribution in targeted organs by high-resolution SIMS imaging

After examining the global distribution of lipids in the male gammarid, we then applied high-resolution SIMS imaging to scrutinize the individual organs at 2-μm lateral resolution. Two regions of interest (ROIs) covering various tissue types including the HP, gonad, and muscle were targeted as shown in the optical images in Figure 4. The ion at m/z 224.1, which is a characteristic fragment of PC lipids, was found abundant in the muscle tissue (Figures 4B and 4D), consistent with the results from MALDI MSI. It is interesting to note that this PC fragment was also observed with high intensity in the gonad tissue, implying the presence of PC lipids in the gonad and which may differ from those in the muscle as certain PC species such as PC 34:1 was not observed in the gonad from MALDI MSI analysis. Vitamin E (ions at m/z 429.4, C29H49O2+ [M + H-2H]+ and m/z 430.4, C29H49O2+· M+·) was also observed at in SIMS imaging analysis and was found in all kinds of tissue types. Several unknown ion species were detected between m/z 648.4 and m/z 696.4 in the positive ion mode (Figure S9), and the corresponding ion images show that they appear to be specifically colocalized to the HP (Figures 4B and 4D).

Figure 4.

Lipid distribution in targeted organs of male gammarid by high-resolution SIMS imaging

(A) Optical image of the gammarid tissue section. Scale bar, 2mm.

(B) Ion images of lipid species detected in positive ion mode in ROI 1.

(C) Ion images of lipid species detected in negative ion mode in ROI

(D) Ion images of lipid species detected in positive ion mode in ROI 2.

(E) Ion images of lipid species detected in negative ion mode in ROI 2. Ion image of vitamin E was summed from those of ions at m/z 429.4 (C29H49O2+ [M + H-2H]+) and m/z 430.4 (C29H49O2+· M+·). Ion image of m/z 634.4–696.4 was summed from those of ions at m/z 634.4, 648.5, 648.4, 664.5, 666.4, 680.4, 682.4, and 696.4. Ion image of m/z 588.5–618.5 was summed from those of ions at m/z 588.5, 602.5, 604.5, 616.5, and 618.5. ROI: region of interest; H: hemocoel; HP: hepatopancreas; G. gonad; M: muscle.

In negative ion mode, several FA species were detected (Figure S10), among which FA 18:1 (oleic acid) was observed across the analyzed regions with higher abundance observed in the body cavity hemocoel (Figures 4C and 4E). The ion at m/z 297.2 showed strong signal in the SIMS spectra acquired in negative ion mode, and the ion images illustrate that this ion species seems to be mostly derived from the lumen of the HP (Figure 4E). The ion image of PE lipid was summed from those of diacylglycerophosphatidylethanolamine and 1-(1Z-alkenyl),2-acylglycerophosphatidylethanol amines which were all predominantly localized in the HP (Figure S11). Also, in HP, some unknown ion species at m/z 588.5, 602.5, 604.5, 616.5, and 618.5 were detected. These ions turned out to have a very different distribution pattern from that of the ion at m/z 297.2, although they were all derived from the HP organ (Figures S12, 4C, and 4E). The overlay images of the sum of these ion species and FA 18:1 reveal that their distribution is similar to that of ions at m/z 648.4–696.4 detected in positive ion mode. This high-resolution examination of ROIs of the whole-body tissue section provided not only a clearer map of the chemical species distributed in individual organs of the gammarid but also supplementary information in terms of lipid detection.

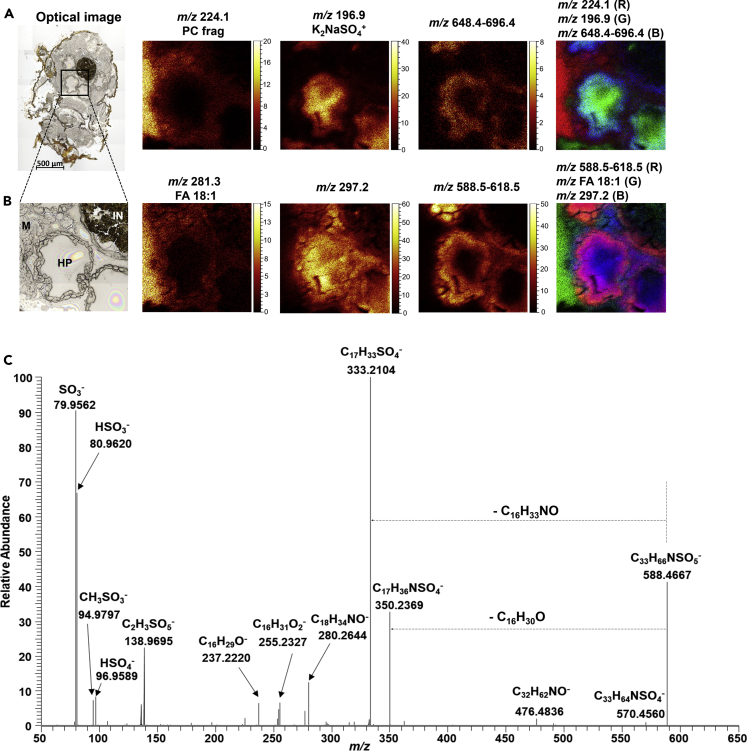

Identification of sulfate-based lipid species in the hepatopancreas

With the aim to identify whether the ion species at m/z 632.4–696.4 (in positive ion mode) and m/z 588.5–618.5 (in negative ion mode) are localized in the lumen or the epithelium of the HP, the HP region was then targeted by SIMS imaging on the transverse section where the structures of the 4 HP caeca are well defined (Figure 5). Consistent with the above MALDI and SIMS analyses of longitudinal tissue sections, the ion at m/z 224.1 (PC head group) was predominantly found in the muscle tissue. The ion at m/z 196.9 which was assigned as salt ion K2NaSO4+ (based on spectral library search in SurfaceLab) turned out to be concentrated in the lumen of the HP, whereas the ions at m/z 632.4–696.4 were mainly detected from the epithelium of the HP and intestine (Figure 5A). For ions generated in negative ion mode, FA 18:1 shared similar distribution as the PC head group. The ion at m/z 297.2 was found in both the lumen and epithelium of the HP with higher abundance in the lumen. The summed ion image of the ions at m/z 588.5–618.5 and its overlay with FA 18:1 and m/z 297.2 confirm that these ion species are localized principally in the epithelium of the HP and intestine (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Identification of sulfate-based lipid species in the hepatopancreas

(A) Ion images of selected chemical species detected in positive ion mode. Scale bar, 500 μm.

(B) Ion images of selected chemical species detected in negative ion mode.

(C) MS/MS spectrum of the precursor ion at m/z 588.4667 acquired on a QExactive mass spectrometer in negative ion mode. HP: hepatopancreas; M: muscle; IN: intestine.

To characterize these unknown ion species, HP tissues from 10 male gammarids were pooled and then extracted according to a modified Folch lipid extraction procedure. Full scan mode and MS/MS on a high-resolution mass spectrometer (ESI-Orbitrap) was performed in both polarities. The ions at m/z 634.4–696.4 were not observed in the positive ion mode, either due to low abundance or low extraction efficiency. In negative ion mode, the ions at m/z 295.2, 297.2 and m/z 588.5–618.5 were readily detected, and subsequent MS/MS analyses yielded informative tandem mass spectra (Figures 5C and S13–S18). Fragment ions corresponding to sulfate ion (m/z 79.9562, SO3-, m/z 80.9620, HSO3- and m/z 96.9589, HSO4-), as well as neutral losses of hydrocarbon chains containing O and N motifs (e.g., C16H30O and C16H33NO in Figure 5C), were observed in the MS/MS spectra of all the precursor ions at m/z 588.5–618.5, indicating these molecules were sulfate-based lipids. Both precursor and fragment ions were annotated with a high mass accuracy better than 5 ppm (Figure 5C, Figures S15–S18, and Table S1). Based on these accurate MS and MS/MS data, various databases including METLIN (Smith, et al., 2005) and LIPID MAPS (Fahy, et al., 2007) were interrogated without getting any possible matches. Thus, these sulfate-based lipids are predicted to be new molecules present in this gammarid species. Sulfate-based lipids (SBLs) belong to sulfolipids, a heterogeneous class of lipids containing sulfur element in the structure (Dias, et al., 2019). In mammals, SBLs are involved in various biochemical processes including cell-cell communication (Honke, 2013), inflammation (Hu, et al., 2007), and immunity (Avila, et al., 1996). Some SBLs, such as cholesterol sulfate and SO3-Gal-ceramide, are commonly found in the epithelium of digestive tracts to regulate the activities of pancreatic protease by inhibiting elastase (Ito, et al., 1998). We hypothesized that the SBL detected in the HP might be involved in similar activities in G. fossarum. However, further investigations are required to elucidate their biological functions.

Dynamic change in oocyte lipid composition during the female reproductive cycle

As described previously, the reproductive cycle of female gammarids comprises six molt stages which are characterized by the maturation of oocytes (Geffard, et al., 2010; Schirling, et al., 2004). To investigate the dynamics of lipid composition related to the maturation process, high-resolution TOF-SIMS imaging was performed to map the chemical composition of the early vitellogenic oocytes of female gammarids at C1 stage and the late vitellogenic oocytes of female gammarids at D1 stage, respectively. The analyzed areas covering various tissue types including oocytes, HP, intestine, and muscle are shown in Figure 6. The regions of oocytes were defined and outlined by comparing with hematoxylin and eosin-stained images of the same sections analyzed by TOF-SIMS (Figure S19). For females at both C1 and D1 stages, FAs were detected across the analyzed area with lower abundance in the intestine and HP. Intense signals of FAs were also observed in the hallow area caused by tissue cracking which frequently occurred during preparation of fragile tissue sections. The ion at m/z 297.2 was found abundant in the HP and intestine in females at both stages. Very interesting to note is the distribution of the newly identified sulfate-based lipids. Compared to the female at C1 stage where the SBLs were mainly detected from the HP, the D1 female showed a significant accumulation of SLs in the oocytes. In Figure 6B, the overlay image of SBL, FA18:1, and the ion at m/z 297.2 illustrates that the SBLs are only accumulated in the secondary oocytes and are absent in the primary oocytes, which are immature oocytes at the previtellogenic stage (Schirling, et al., 2004; Tan-Fermin and Pudadera, 1989).

Figure 6.

Dynamic change in oocyte lipid composition during the reproductive cycle

(A) Optical image of the transvers tissue section of C1 female and ion images of FA18:1 and sulfate-based lipids. Scale bar, 500 μm.

(B) Optical image of the transvers tissue section of D1 female and ion images of FA 18:1 and sulfate-based lipids. Scale bar, 500 μm. The ion image of sulfate-based lipids at m/z 588.5–618.5 was summed from those of m/z 588.5, m/z 602.5, m/z 604.5, m/z 616.5, and m/z 618.5.

Although it is demonstrated in many crustacean species that accumulation of lipids in the oocytes occurs during the ovarian maturation, the origin of these rapidly accumulated lipids is not fully understood. Mobilization of lipids from the HP to oocytes in the prawn Penaeus japonicus has been proven by tracing the lipids derived from radioactive labeled FAs (Teshima, et al., 1988). In addition, several studies have reported the co-occurrence of a decreased lipid content in the HP and an increased lipid content in the ovary during ovarian maturation (Alava, et al., 2007; Castille and Lawrence, 1989; Spaargaren and Haefner, 1994). Therefore, it has been hypothesized that the HP also functions as a lipid storage organ in crustacean species and could release the required lipids to oocytes to facilitate their maturation. By high-resolution MSI, the observation of the accumulation of SBLs in oocytes of D1 female suggests that these SBLs have probably gone through this lipid transfer process to accumulate in oocytes of the female gammarids and play an important role in the maturation process.

Limitations of the study

The chemical structure of sulfate-based lipid species observed in the HP and oocytes should be determined by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and their respective isomers if they exist by ion mobility-MS. Characterization of seminolipid is a challenge since this lipid may be associated with lipid storage droplets or/and gonad tissue. The determination of the precise FA structure (geometric isomerism, cis/trans) was not addressed in this study.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Sophie Ayciriex (sophie.ayciriex@univ-lyon1.fr).

Material availability

This study did not generate new unique materials.

Data and software availability

Shotgun lipidomics data and MS imaging data have been deposited to the EMBL-EBI MetaboLights database with the identifier MTBLS1901. The data sets can be accessed here: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/metabolights/MTBLS1901.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the French National Research Agency (ANR) (young investigator grant, ANR-18-CE34-0008 PLAN-TOX), the Chemistry Institute of Lyon (young investigator inter-laboratory cooperation grant,ICL-2017 DOSAGE), the ISA research funds grant, and also the French GDR “Aquatic Ecotoxicology” framework which aims at fostering stimulating discussions and collaborations for more integrative approaches. MALDI-TOF instrument at CNRS-ICSN was founded by the Région Ile-de-France (DIM Analytics). We would like to thank Elodie Chauvet, Yves de Puydt from Tescan Analytics (Fuveau, France) for the access to TOF-SIMS instrument and the help with the experiments. We thank Jean-Valery Guillaubez for his technical assistance on the lipid MS analysis of the hepatopancreas sample. We would also like to warmly thank Dr. Serge Della-Negra for his support and fruitful discussions. We thank Dr. Alain Brunelle for his careful and critical reading of the manuscript. The authors thank Nicolas Delorme, Laura Garnero, Hervé Quéau for their technical assistance in gammarids sampling and Guy Charmantier for his help on gammarids histology. We thank the Pôle Biosciences, Technologies, Ethique of Lyon Catholic University for the access to the microtome.

Author contributions

T.F., O.G., A.C., D.D.E., and S.A. designed research; T.F., O.K., E.T., N.E., and S.A. performed the experiments; J.L., A.S., A.Sh., and D.T. contributed analytic tools; T.F., Y.C., and S.A. performed data processing; T.F., O.K., O.G., Y.C., E.T., and S.A. analyzed data; T.F., O.G., and K.A. conducted histology analysis; S.A. provided funding, project administration, and resources; and T.F. and S.A. prepared the figures and wrote the manuscript. All authors have provided feedback on the manuscript and have approved the final version.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: February 19, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102115.

Supplemental Information

References

- Alava V.R., Quinitio E.T., De Pedro J.B., Priolo F.M.P., Orozco Z.G.A., Wille M. Lipids and fatty acids in wild and pond-reared mud crab Scylla serrata (Forsskål) during ovarian maturation and spawning. Aquac. Res. 2007;38:1468–1477. [Google Scholar]

- Arambourou H., Fuertes I., Vulliet ., Daniele G., Noury P., Delorme N., Abbaci K., Barata C. Fenoxycarb exposure disrupted the reproductive success of the amphipod Gammarus fossarum with limited effects on the lipid profile. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0196461. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila J.L., Rojas M., Avila A. Cholesterol sulphate-reactive autoantibodies are specifically increased in chronic chagasic human patients. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1996;103:40–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.877569.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayciriex S., Djelti F., Alves S., Regazzetti A., Gaudin M., Varin J., Langui D., Bieche I., Hudry E., Dargere D. Neuronal cholesterol accumulation induced by Cyp46a1 down-regulation in mouse hippocampus disrupts brain lipid homeostasis. Front Mol. Neurosci. 2017;10:211. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayciriex S., Touboul D., Brunelle A., Laprevote O. Time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometer: a novel tool for lipid imaging. Clin. Lipidol. 2011;6:437–445. [Google Scholar]

- Benabdellah F., Seyer A., Quinton L., Touboul D., Brunelle A., Laprevote O. Mass spectrometry imaging of rat brain sections: nanomolar sensitivity with MALDI versus nanometer resolution by TOF-SIMS. Anal Bioanal. Chem. 2010;396:151–162. doi: 10.1007/s00216-009-3031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besse J.P., Coquery M., Lopes C., Chaumot A., Budzinski H., Labadie P., Geffard O. Caged Gammarus fossarum (Crustacea) as a robust tool for the characterization of bioavailable contamination levels in continental waters: towards the determination of threshold values. Water Res. 2013;47:650–660. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bich C., Touboul D., Brunelle A. Cluster TOF-SIMS imaging as a tool for micrometric histology of lipids in tissue. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2014;33:442–451. doi: 10.1002/mas.21399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman A.P., Abzalimov R.R., Shvartsburg A.A. Broad separation of isomeric lipids by high-resolution differential ion mobility spectrometry with tandem mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2017;28:1552–1561. doi: 10.1007/s13361-017-1675-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S.H., Mitchell T.W., Blanksby S.J. Analysis of unsaturated lipids by ozone-induced dissociation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1811:807–817. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitao A., Lyssimachou A., Castro L.F.C., Santos M.M. Obesogens in the aquatic environment: an evolutionary and toxicological perspective. Environ. Int. 2017;106:153–169. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho M., Sampaio J.L., Palm W., Brankatschk M., Eaton S., Shevchenko A. Effects of diet and development on the Drosophila lipidome. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2012;8:600. doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castille F.L., Lawrence A.L. Relationship between maturation and biochemical composition of the gonads and digestive glands of the shrimps Penaeus aztecus ives and Penaeus setiferus (L.) J. Crust Biol. 1989;9:202–211. [Google Scholar]

- Chaumot A., Coulaud R., Adam O., Queau H., Lopes C., Geffard O. In situ reproductive bioassay with caged Gammarus fossarum (Crustacea): Part 1-gauging the confounding influence of temperature and water hardness. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2020;39:667–677. doi: 10.1002/etc.4655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaumot A., Geffard O., Armengaud J., Maltby L. Chapter 11 - gammarids as reference species for freshwater monitoring. In: Amiard-Triquet C., Amiard J.-C., Mouneyrac C., editors. Aquat Ecotoxicol. Academic Press; 2015. pp. 253–280. [Google Scholar]

- Davoli E., Zucchetti M., Matteo C., Ubezio P., D'Incalci M., Morosi L. The space dimension at the micro level: mass spectrometry imaging of drugs in tissues. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1002/mas.21633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Mendoza D., Pilon M. Control of membrane lipid homeostasis by lipid-bilayer associated sensors: a mechanism conserved from bacteria to humans. Prog. Lipid Res. 2019;76:100996. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2019.100996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedourge-Geffard O., Palais F., Biagianti-Risbourg S., Geffard O., Geffard A. Effects of metals on feeding rate and digestive enzymes in Gammarus fossarum: an in situ experiment. Chemosphere. 2009;77:1569–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias I.H.K., Ferreira R., Gruber F., Vitorino R., Rivas-Urbina A., Sanchez-Quesada J.L., Vieira Silva J., Fardilha M., de Freitas V., Reis A. Sulfate-based lipids: analysis of healthy human fluids and cell extracts. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2019;221:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2019.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djambazova K.V., Klein D.R., Migas L.G., Neumann E.K., Rivera E.S., Van de Plas R., Caprioli R.M., Spraggins J.M. Resolving the complexity of spatial lipidomics using MALDI TIMS imaging mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2020;92:13290–13297. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c02520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta A., Sinha D.K. Zebrafish lipid droplets regulate embryonic ATP homeostasis to power early development. Open Biol. 2017;7:170063. doi: 10.1098/rsob.170063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejsing C.S., Sampaio J.L., Surendranath V., Duchoslav E., Ekroos K., Klemm R.W., Simons K., Shevchenko A. Global analysis of the yeast lipidome by quantitative shotgun mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009;106:2136–2141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811700106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy E., Cotter D., Sud M., Subramaniam S. Lipid classification, structures and tools. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1811:637–647. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy E., Subramaniam S., Brown H.A., Glass C.K., Merrill A.H., Jr., Murphy R.C., Raetz C.R., Russell D.W., Seyama Y., Shaw W. A comprehensive classification system for lipids. J. Lipid Res. 2005;46:839–861. doi: 10.1194/jlr.E400004-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy E., Subramaniam S., Murphy R.C., Nishijima M., Raetz C.R., Shimizu T., Spener F., van Meer G., Wakelam M.J., Dennis E.A. Update of the LIPID MAPS comprehensive classification system for lipids. J. Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S9–S14. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800095-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy E., Sud M., Cotter D., Subramaniam S. LIPID MAPS online tools for lipid research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W606–W612. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu T., Oetjen J., Chapelle M., Verdu A., Szesny M., Chaumot A., Degli-Esposti D., Geffard O., Clement Y., Salvador A. In situ isobaric lipid mapping by MALDI-ion mobility separation-mass spectrometry imaging. J. Mass Spectrom. 2020;55:e4531. doi: 10.1002/jms.4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuertes I., Pina B., Barata C. Changes in lipid profiles in Daphnia magna individuals exposed to low environmental levels of neuroactive pharmaceuticals. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;733:139029. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geffard O., Xuereb B., Chaumot A., Geffard A., Biagianti S., Noel C., Abbaci K., Garric J., Charmantier G., Charmantier-Daures M. Ovarian cycle and embryonic development in Gammarus fossarum: application for reproductive toxicity assessment. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010;29:2249–2259. doi: 10.1002/etc.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessel M.M., Norris J.L., Caprioli R.M. MALDI imaging mass spectrometry: spatial molecular analysis to enable a new age of discovery. J. Proteom. 2014;107:71–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groessl M., Graf S., Knochenmuss R. High resolution ion mobility-mass spectrometry for separation and identification of isomeric lipids. Analyst. 2015;140:6904–6911. doi: 10.1039/c5an00838g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan X.L., Cestra G., Shui G., Kuhrs A., Schittenhelm R.B., Hafen E., van der Goot F.G., Robinett C.C., Gatti M., Gonzalez-Gaitan M. Biochemical membrane lipidomics during Drosophila development. Dev. Cell. 2013;24:98–111. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X., Gross R.W. Global analyses of cellular lipidomes directly from crude extracts of biological samples by ESI mass spectrometry: a bridge to lipidomics. J. Lipid Res. 2003;44:1071–1079. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R300004-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X., Gross R.W. Shotgun lipidomics: electrospray ionization mass spectrometric analysis and quantitation of cellular lipidomes directly from crude extracts of biological samples. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2005;24:367–412. doi: 10.1002/mas.20023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X., Gross R.W. Shotgun lipidomics: multidimensional MS analysis of cellular lipidomes. Expert Rev. Proteomics. 2005;2:253–264. doi: 10.1586/14789450.2.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvald E.B., Sprenger R.R., Dall K.B., Ejsing C.S., Nielsen R., Mandrup S., Murillo A.B., Larance M., Gartner A., Lamond A.I. Multi-omics analyses of starvation responses reveal a central role for lipoprotein metabolism in acute starvation survival in C. elegans. Cell Syst. 2017;5:38–52 e34. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honke K. Biosynthesis and biological function of sulfoglycolipids. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2013;89:129–138. doi: 10.2183/pjab.89.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu F.F. Mass spectrometry-based shotgun lipidomics - a critical review from the technical point of view. Anal Bioanal. Chem. 2018;410:6387–6409. doi: 10.1007/s00216-018-1252-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C., Wang C., He L., Han X. Novel strategies for enhancing shotgun lipidomics for comprehensive analysis of cellular lipidomes. Trends Analyt. Chem. 2019;120:115330. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2018.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu R., Li G., Kamijo Y., Aoyama T., Nakajima T., Inoue T., Node K., Kannagi R., Kyogashima M., Hara A. Serum sulfatides as a novel biomarker for cardiovascular disease in patients with end-stage renal failure. Glycoconj. J. 2007;24:565–571. doi: 10.1007/s10719-007-9053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito N., Iwamori Y., Hanaoka K., Iwamori M. Inhibition of pancreatic elastase by sulfated lipids in the intestinal mucosa. J. Biochem. 1998;123:107–114. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson S.N., Ugarov M., Post J.D., Egan T., Langlais D., Schultz J.A., Woods A.S. A study of phospholipids by ion mobility TOFMS. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2008;19:1655–1662. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jubeaux G., Simon R., Salvador A., Queau H., Chaumot A., Geffard O. Vitellogenin-like proteins in the freshwater amphipod Gammarus fossarum (Koch, 1835): functional characterization throughout reproductive process, potential for use as an indicator of oocyte quality and endocrine disruption biomarker in males. Aquat. Toxicol. 2012;112-113:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.I., Kim H., Pang E.S., Ryu E.K., Beegle L.W., Loo J.A., Goddard W.A., Kanik I. Structural characterization of unsaturated phosphatidylcholines using traveling wave ion mobility spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2009;81:8289–8297. doi: 10.1021/ac900672a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose C., Surma M.A., Gerl M.J., Meyenhofer F., Shevchenko A., Simons K. Flexibility of a eukaryotic lipidome--insights from yeast lipidomics. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose C., Surma M.A., Simons K. Organellar lipidomics--background and perspectives. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2013;25:406–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knittelfelder O., Traikov S., Vvedenskaya O., Schuhmann A., Segeletz S., Shevchenko A., Shevchenko A. Shotgun lipidomics combined with laser capture microdissection: a tool to analyze histological zones in cryosections of tissues. Anal Chem. 2018;90:9868–9878. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b02004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolanowski W., Stolyhwo A., Grabowski M. Fatty acid composition of selected fresh water gammarids (Amphipoda, Crustacea): a potentially innovative source of omega-3 LC PUFA. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2007;84:827–833. [Google Scholar]

- Kunz P.Y., Kienle C., Gerhardt A. Gammarus spp. in aquatic ecotoxicology and water quality assessment: toward integrated multilevel tests. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2010;205:1–76. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-5623-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaptrot K.L., May J.C., Dodds J.N., McLean J.A. Ion mobility conformational lipid atlas for high confidence lipidomics. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:985. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08897-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R.F., Walker A. Lipovitellin and lipid droplet accumulation in oocytes during ovarian maturation in the blue crab, Callinectes sapidus. J. Exp. Zool. 1995;271:401–412. [Google Scholar]

- Lessig J., Gey C., Suss R., Schiller J., Glander H.J., Arnhold J. Analysis of the lipid composition of human and boar spermatozoa by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, thin layer chromatography and 31P NMR spectroscopy. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;137:265–277. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell L.A., Heeren R.M.A. Imaging mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2007;26:606–643. doi: 10.1002/mas.20124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehennaoui K., Georgantzopoulou A., Felten V., Andreï J., Garaud M., Cambier S., Serchi T., Pain-Devin S., Guérold F., Audinot J.N. Gammarus fossarum (Crustacea, Amphipoda) as a model organism to study the effects of silver nanoparticles. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;566-567:1649–1659. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourente G., Medina A., González S., Rodríguez A. Changes in lipid class and fatty acid contents in the ovary and midgut gland of the female fiddler crab Uca tangeri (Decapoda, Ocypodiadae) during maturation. Mar. Biol. 1994;121:187–197. [Google Scholar]

- Obeid L.M., Linardic C.M., Karolak L.A., Hannun Y.A. Programmed cell death induced by ceramide. Science. 1993;259:1769–1771. doi: 10.1126/science.8456305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palm W., Sampaio J.L., Brankatschk M., Carvalho M., Mahmoud A., Shevchenko A., Eaton S. Lipoproteins in Drosophila melanogaster-assembly, function, and influence on tissue lipid composition. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002828. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penkov S., Mende F., Zagoriy V., Erkut C., Martin R., Passler U., Schuhmann K., Schwudke D., Gruner M., Mantler J. Maradolipids: diacyltrehalose glycolipids specific to dauer larva in Caenorhabditis elegans. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:9430–9435. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravid T., Tietz A., Khayat M., Boehm E., Michelis R., Lubzens E. Lipid accumulation in the ovaries of a marine shrimp Penaeus semisulcatus (de haan) J. Exp. Biol. 1999;202(Pt 13):1819–1829. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.13.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan E., Nguyen C.Q.N., Shiea C., Reid G.E. Detailed structural characterization of sphingolipids via 193 nm ultraviolet photodissociation and ultra high resolution tandem mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2017;28:1406–1419. doi: 10.1007/s13361-017-1668-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sämfors S., Fletcher J.S. Lipid diversity in cells and tissue using imaging SIMS. Annu. Rev. Anal Chem. 2020;13:249–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anchem-091619-103512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirling M., Jungmann D., Ladewig V., Nagel R., Triebskorn R., Kohler H.R. Endocrine effects in Gammarus fossarum (Amphipoda): influence of wastewater effluents, temporal variability, and spatial aspects on natural populations. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2005;49:53–61. doi: 10.1007/s00244-004-0153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirling M., Triebskorn R., Köhler H.R. Variation in stress protein levels (hsp70 and hsp90) in relation to oocyte development in Gammarus fossarum (Koch 1835) Invertebr. Reprod. Dev. 2004;45:161–167. [Google Scholar]

- Shevchenko A., Simons K. Lipidomics: coming to grips with lipid diversity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:593–598. doi: 10.1038/nrm2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C.A., O'Maille G., Want E.J., Qin C., Trauger S.A., Brandon T.R., Custodio D.E., Abagyan R., Siuzdak G. METLIN: a metabolite mass spectral database. Ther. Drug Monit. 2005;27:747–751. doi: 10.1097/01.ftd.0000179845.53213.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaargaren D.H., Haefner P.A. Interactions of ovary and hepatopancreas during the reproductive cycle of Crangon crangon (L.). II. biochemical relationships. J. Crust Biol. 1994;14:6–19. [Google Scholar]

- Spengler B. Mass spectrometry imaging of biomolecular information. Anal. Chem. 2015;87:64–82. doi: 10.1021/ac504543v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramoniam T. Mechanisms and control of vitellogenesis in crustaceans. Fish. Sci. 2011;77:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Tan-Fermin J.D., Pudadera R.A. Ovarian maturation stages of the wild giant tiger prawn, Penaeus monodon Fabricius. Aquaculture. 1989;77:229–242. [Google Scholar]

- Tanphaichitr N., Kongmanas K., Faull K.F., Whitelegge J., Compostella F., Goto-Inoue N., Linton J.J., Doyle B., Oko R., Xu H. Properties, metabolism and roles of sulfogalactosylglycerolipid in male reproduction. Prog. Lipid Res. 2018;72:18–41. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor N.S., White T.A., Viant M.R. Defining the baseline and oxidant perturbed lipidomic profiles of Daphnia magna. Metabolites. 2017;7:11. doi: 10.3390/metabo7010011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teshima S., Kanazawa A., Koshio S., Horinouchi K. Lipid metabolism in destalked prawn Penaeus japonicus: induced maturation and accumulation of lipids in the ovaries. Nippon Suisan Gakk. 1988;54:1115–1122. [Google Scholar]

- Thommen A., Werner S., Frank O., Philipp J., Knittelfelder O., Quek Y., Fahmy K., Shevchenko A., Friedrich B.M., Julicher F. Body size-dependent energy storage causes Kleiber's law scaling of the metabolic rate in planarians. Elife. 2019;8:e38187. doi: 10.7554/eLife.38187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touboul D., Brunelle A. What more can TOF-SIMS bring than other MS imaging methods? Bioanalysis. 2016;8:367–369. doi: 10.4155/bio.16.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp J., Armengaud J., Pible O., Gaillard J.C., Abbaci K., Habtoul Y., Chaumot A., Geffard O. Proteomic investigation of male Gammarus fossarum, a freshwater crustacean, in response to endocrine disruptors. J. Proteome Res. 2015;14:292–303. doi: 10.1021/pr500984z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meer G. Cellular lipidomics. EMBO J. 2005;24:3159–3165. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meer G., Voelker D.R., Feigenson G.W. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:112–124. doi: 10.1038/nrm2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Hinz S., Uckermann O., Honscheid P., von Schonfels W., Burmeister G., Hendricks A., Ackerman J.M., Baretton G.B., Hampe J. Shotgun lipidomics-based characterization of the landscape of lipid metabolism in colorectal cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2020;1865:158579. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2019.158579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wattier R., Mamos T., Copilas-Ciocianu D., Jelic M., Ollivier A., Chaumot A., Danger M., Felten V., Piscart C., Zganec K. Continental-scale patterns of hyper-cryptic diversity within the freshwater model taxon Gammarus fossarum (Crustacea, Amphipoda) Sci. Rep. 2020;10:16536. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73739-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenk M.R. The emerging field of lipidomics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005;4:594–610. doi: 10.1038/nrd1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigh A., Geffard O., Abbaci K., Francois A., Noury P., Bergé A., Vulliet E., Domenjoud B., Gonzalez-Ospina A., Bony S. Gammarus fossarum as a sensitive tool to reveal residual toxicity of treated wastewater effluents. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;584-585:1012–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams P.E., Klein D.R., Greer S.M., Brodbelt J.S. Pinpointing double bond and sn-positions in glycerophospholipids via hybrid 193 nm ultraviolet photodissociation (UVPD) mass spectrometry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:15681–15690. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b06416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wouters R., Molina C., Lavens P., Calderón J. Lipid composition and Vitamin content of wild female Litopenaeus vannamei in different stages of sexual maturation. Aquaculture. 2001;198:16. [Google Scholar]

- Zemski Berry K.A., Hankin J.A., Barkley R.M., Spraggins J.M., Caprioli R.M., Murphy R.C. MALDI imaging of lipid biochemistry in tissues by mass spectrometry. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:6491–6512. doi: 10.1021/cr200280p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Hayashi Y., Cheng X., Watanabe T., Wang X., Taniguchi N., Honke K. Testis-specific sulfoglycolipid, seminolipid, is essential for germ cell function in spermatogenesis. Glycobiology. 2005;15:649–654. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwi043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.M., Rock C.O. Membrane lipid homeostasis in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;6:222–233. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zullig T., Kofeler H.C. High resolution mass spectrometry in lipidomics. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1002/mas.21627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Shotgun lipidomics data and MS imaging data have been deposited to the EMBL-EBI MetaboLights database with the identifier MTBLS1901. The data sets can be accessed here: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/metabolights/MTBLS1901.