Abstract

Context

The pandemic has substantially increased the workload of hospital palliative care providers, requiring them to be responsive and innovative despite limited information on the specific end of life care needs of patients with COVID-19. Multi-site data detailing clinical characteristics of patient deaths from large populations, managed by specialist and generalist palliative care providers are lacking.

Objectives

To conduct a large multicenter study examining characteristics of COVID-19 hospital deaths and implications for care.

Methods

A multi-center retrospective evaluation examined 434 COVID-19 deaths in 5 hospital trusts over the period March 23, 2020 to May 10, 2020.

Results

Eighty three percent of patients were over 70.32% were admitted from care homes. Diagnostic timing indicated over 90% of those who died contracted the virus in the community. Dying was recognized in over 90% of patients, with the possibility of dying being identified less than 48 hours from admission for a third. In over a quarter, death occurred less than 24 hours later. Patients who were recognized to be dying more than 72 hours prior to death were most likely to have access to medication for symptom control.

Conclusion

This large multicenter study comprehensively describes COVID-19 deaths throughout the hospital setting. Clinicians are alert to and diagnose dying appropriately in most patients. Outcomes could be improved by advance care planning to establish preferences, including whether hospital admission is desirable, and alongside this, support the prompt use of anticipatory subcutaneous medications and syringe drivers if needed. Finally, rapid discharges and direct hospice admissions could better utilize hospice beds and improve care.

Key Words: COVID-19, Deaths, Hospital, End of life care, Palliative, Characteristics

Key Message

This article describes a large multicenter retrospective evaluation of COVID-19 deaths and the care provided. Clinicians are alert to and diagnose dying appropriately in most patients. Care could be improved by advance care planning and the prompt use of anticipatory subcutaneous medications and syringe drivers.

Introduction

Palliative care has improved patient and family experience during the pandemic despite multiple challenges.1, 2, 3 Recent studies, in the hospital setting, focus on patients referred to specialist palliative care (SPC),4 observing patients have a shorter prognosis and higher in-hospital mortality and symptom burden than ‘typical’ SPC caseloads.5 Most symptoms are controlled with modest doses of opioids and benzodiazepines6 and early syringe driver use is important.4 Different phenotypes have been observed including; fulminant COVID-19, atypical presenters and those that stabilize then rapidly deteriorate.6 , 7

This study responds to the need for data on hospital deaths from large multi-site studies.2 , 8 , 9 Patients referred to SPC are likely unrepresentative of all COVID-19 hospital deaths, which were analyzed in this study to get a true picture of care and to ascertain if dying is being identified appropriately. The COVPALL study10 has demonstrated a significant increase in the workload of hospital palliative care providers whilst hospices remain less affected. Improved understanding of the trajectory of a death from COVID-19 will help plan better utilization of resources across sites.

Methods

This multicenter retrospective audit included 5 NHS Foundation Trusts: County Durham and Darlington, Gateshead, Newcastle, Northumbria, South Tyneside and Sunderland. These hospitals serve populations who had among the highest COVID-19 prevalence during the first wave. The work was registered with service evaluation teams.

Patients who died in hospital in alternate weeks between March 23, 2020 and May 10, 2020 were included if they had a positive nasopharyngeal swab for COVID-19 just prior to or during their in-patient stay. Data collection proformas were produced independently in two NHS Foundation Trusts (South Tees and Northumbria) by SPC physicians who were experienced in providing care to hospital patients with COVID-19 at the start of the pandemic (HB, CB, KF). The data collected was (in the opinion of local SPC multidisciplinary teams) information required to understand how COVID-19 patients were dying and how care could be improved. These proformas were amalgamated and repeated review with all authors made the proforma fit for purpose across all sites. A data collection guide provided detailed instructions. For example: Symptoms were defined as COVID-19 related symptoms, if they included shortness of breath, cough, sore throat, anosmia/dysgeusia, gastrointestinal upset OR general malaise AND the clinical impression was COVID-19. The symptoms were recorded as Non-COVID-19 related if no clinical concern of COVID-19 was highlighted e.g. symptoms clearly indicating acute cerebrovascular/cardiovascular disease or trauma. Guidance also advised if and when to record that the possibility of dying was recognized by the clinical team. This included first documentation that the person was “at risk of further deterioration,” “sick/ill enough to die,” “approaching end of life,” or “dying.” This included (but was not exclusive to) care of the dying patient documentation completion.

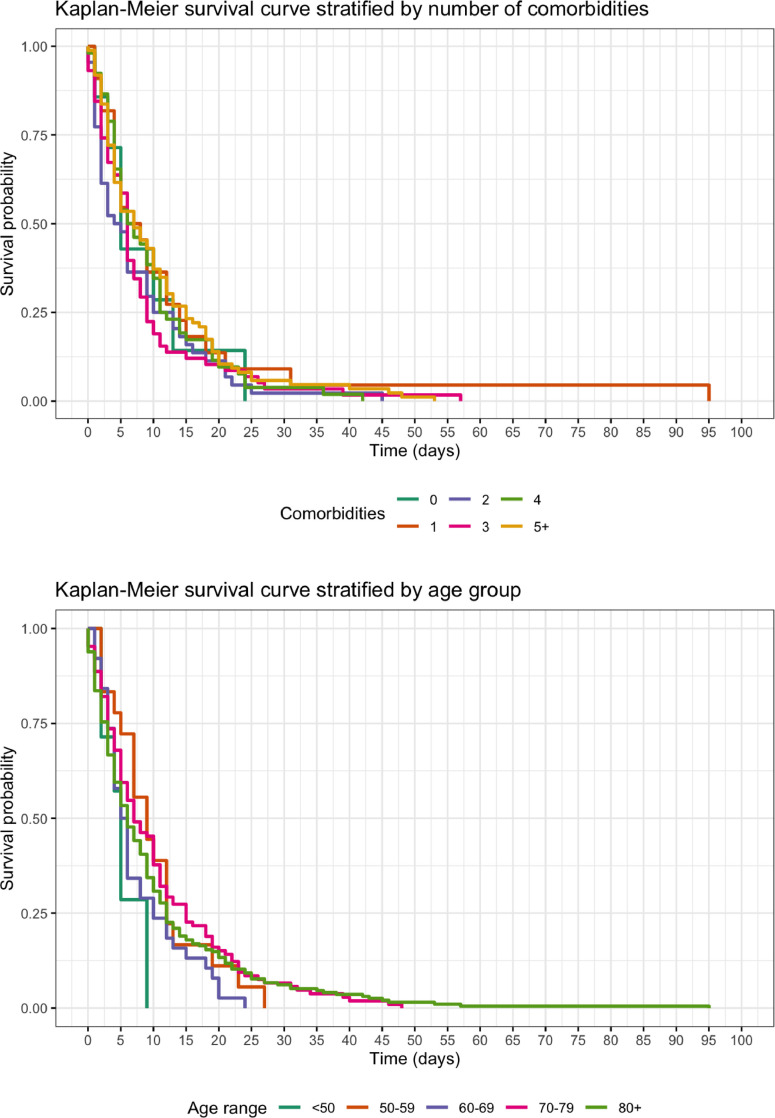

Data were extracted from medical and nursing notes by clinicians with knowledge of local note keeping systems AND palliative care experience. Data that were unavailable from electronic/paper medical/nursing notes and medicine charts were left blank. However, if no reference was made to specific symptoms or administration of medication these were recorded as not present or not given. Given the size of the study statistical adjustment was not made for missing data. Simple descriptive statistics were used to describe the audit data, the Chi Square statistic was used to test the relationship between categorical variables, Kaplan-Meier plots and log rank tests were used to investigate differences in the survival distribution on the basis of age and number of comorbidities.

Results

434 deaths from COVID-19 occurred over the study period. Most deaths occurred in the elderly population with progressively fewer people in the younger age groups: 235 (54.1%) were aged 80 or over, 124 (28.6%) were aged 70–79, 46 (10.6%) were aged 60–69, 21 (4.8%) were aged 50–59 and 8 (1.9%) were aged less than 50. 54.6% were male, 45.4% were female. A total of 138 (31.8%) of all patients were admitted from a care home, 258 (59.4%) from home and the remainder were admitted from another community location e.g. sheltered accommodation or supported living. Around 95.5% were white British (representative of the background population).

Most patients who died from COVID-19 were admitted for COVID-related symptoms (n = 345, 79.5%). This, together with the fact that 82.7% of positive tests occurred within seven days of admission (36 [8.3%] were positive before admission, 174 [40.1%] on the day of admission, 80 [18.4%] day 1 post admission, 26 [6.0%] day 2 post admission, 43 [9.9%] day 3–7 post admission), indicates that most infection occurred in the community. 17.3% of patients had a late positive swab (>seven days post admission); 33.8% of these patients were admitted with COVID related symptoms indicating the possibility of false negative tests.

Time frame analysis was available on 364 patients (Table 1 ). The possibility of dying was recognized in over 90% of patients. The possibility of dying was less likely to be identified in patients receiving ward-based care (92.1%) compared to those receiving higher level care (98.0%) (P = .039). The possibility of dying was recognized in a third of all patients less than 48 hours from admission. A higher proportion of those dying in higher level care were recognized to be dying within the last 24 hours of life compared with those in ward level care, although this difference was not statistically significant (P = .158). Survival distributions were similar for all age categories, and number of comorbidities (all log rank tests P > .05), meaning no firm conclusions could be drawn to guide prognostication (Fig. 1 ).

Table 1.

Key Time Points During Admission in Relation to Level of Care and Medication Administration

| Places of Care During Admission (n = 364) | Overall Length of Stay | Admission to Recognition of Dying | Recognition of Dying to Death | Recognition of Dying to Death `– HDU/ITU | Recognition of Dying to Death – Level 2 Care | Recognition of Dying to Death – Basic Ward | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–24 hours | 17 (4.7%) | 84 (23.0%) | 96 (26.4%) | 12 (31.6%) | 20 (32.8%) | 62 (23.4%) | ||||||

| 1–3 days | 61 (16.8%) | 65 (17.9%) | 126 (34.6%) | 10 (26.3%) | 24 (39.3%) | 93 (35.2%) | ||||||

| 3–7 days | 108 (29.7%) | 80 (21.9%) | 86 (23.6%) | 7 (18.4%) | 13 (21.3%) | 67 (25.4%) | ||||||

| 7–14 days | 99 (27.2%) | 60 (16.5%) | 26 (7.1%) | 9 (23.7%) | 2 (3.3%) | 16 (6.1%) | ||||||

| 14–21 days | 34 (9.3%) | 24 (6.6%) | 4 (1.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (1.5%) | ||||||

| 21–28 days | 25 (6.9%) | 11 (2.6%) | 2 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.8%) | ||||||

| 28 days + | 20 (5.5%) | 17 (3.0%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||||||

| Dying not | identified | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (3.3%) | 21 (8.0%) | ||||||||

| Dying | identified | 38 (100%) | 59 (96.7%) | 244 (92.1%) | ||||||||

|

Medications prescribed in the last 24 hours of Life (n = 297) |

||||||||||||

| Timing prior to death dying identified | Anticipatory Medications for all 5 symptoms | Anticipatory medication prescribed but incomplete | No Anticipatory medication prescribed | Syringe Driver Prescribed | PRN opioid Received | PRN Benzodiazepine Received | ||||||

| < 24 hours (n = 83) | 72 | 3 | 8 | 23 (27.7%) | 43 (51.8%) | 44 (53.0%) | ||||||

| 24–72 hours (n = 114) | 104 | 3 | 7 | 59 (51.8%) | 70 (61.4%) | 75 (65.7%) | ||||||

| 3 to 7 days (n = 77) | 71 | 4 | 2 | 40 (51.9%) | 39 (50.6%) | 36 (46.8%) | ||||||

| More than 7 days (n = 23) | 21 | 0 | 2 | 11 (47.8%) | 10 (43.4%) | 10 (43.5%) | ||||||

| Timing of recognition of possibility dying |

PRN Opioid Received in final 24 hours |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number doses |

Total OME 24h dose (mg) |

|||||||||||

| Yes - N/162 | Median | Range | Median | Range | No - N/135 | |||||||

| < 24 hours | 43 | 2 | 1–5 (IQR 1-2.5) | 10 | 2–30 (IQR 5–15) | 40 | ||||||

| 24–72 hours | 70 | 2 | 1–9 (IQR 1-2) | 7.5 | 2–120 (IQR 5–15) | 44 | ||||||

| 3–7 days | 39 | 1 | 1–5 (IQR 1–2) | 5 | 3–50 (IQR 5–10) | 38 | ||||||

| > 7 days | 10 | 1 | 1–2 | 5 | 3–5 | 13 | ||||||

| Timing of recognition of possibility dying |

PRN Benzodiazepine Received in final 24 hours |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number doses |

Total 24h dose (mg) |

|||||||||||

| Yes - N/165 | Median | Range | Median | Range | No - N/132 | |||||||

| < 24 hours | 44 | 1.5 | 1–6 (IQR 1–3) | 2.5 | 2.5–25 (IQR 2.5–7.5) | 39 | ||||||

| 24–72 hours | 75 | 2 | 1–8 (IQR 1–3) | 5 | 2.5–20 (IQR 2.5–7.5) | 39 | ||||||

| 3–7 days | 36 | 2 | 1–4 (IQR 1–2) | 5 | 2.5–20 (IQR 2.5–5) | 41 | ||||||

| > 7 days | 10 | 1.5 | 1–5 (IQR 1–2.75) | 3.8 | 2.5–12.5 (IQR 2.5–6.875) | 13 | ||||||

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve stratified by comorbidities and age group.

Prescribing at the end of life was evaluated in 297 patients (patients receiving care in HDU/ITU [n = 38], those in whom dying was not identified [n = 23] and those with data omissions [n = 6] were excluded). Anticipatory medication to treat common symptoms in the last days of life was prescribed for all 5 indications11 in 90.2%. The proportion of those prescribed all anticipatory medicines was lower in those where dying was recognized less than 24 hours before death (86.7%) than in those where it was recognized more than 24 hours before death (92.5%) however this difference was not statistically significant (P = .207). This was equally true of syringe driver use. In those where dying was recognized less than 24 hours prior to death, syringe drivers were prescribed in 27.7%. If dying was recognized more than 24 hours prior to death, syringe drivers were prescribed in 51.4% (P = .003). Patients were more likely to require breakthrough medication in the last 24 hours of life if the possibility of dying was identified in the last 72 hours of life. This was more pronounced and statistically significant for benzodiazepines (60.4% vs. 46.0% [P = .0182]) than for opioids, which was not statistically significant (57.4% vs. 49.0% [P = .171]). This data indicates that there was an increased likelihood of a patient being asymptomatic (not requiring breakthrough medication) and being on a syringe driver if the possibility of dying was recognized earlier. The doses of opioids and benzodiazepines received were relatively modest (Table 1).

Discussion

This large dataset detailing COVID-19 hospital deaths demonstrates that the possibility of dying was recognized in more than 90% of patients. The phrase “possibility of dying” was explicitly decided upon by the multi-site steering group to reflect that a person was “sick enough to die”12 despite clinicians dealing with a novel disease with an uncertain trajectory and different treatments being regularly introduced. While acknowledging this important distinction in the phrase used, these results are similar to a national audit of patients who died in hospitals before the COVID-19 pandemic, where dying was recognized in 88% of patients.11 In this (pre-COVID-19) audit, more patients were identified as dying in the last 24 hours of life than in our COVID-19 data (36% and 26.4% respectively). This may be due to health-care professionals being alert to the grave consequences of the virus or the use of the terminology “possibility” of dying.

This study demonstrates that the possibility of dying was identified in most, however this was often shortly before death. This may present challenges to facilitating individualized care plans and supporting wishes and preferences. Patients may be too unstable for transfers to alternative settings for end of life care; proactive palliative care in hospital is essential to ensure optimal end of life care in the last days of life. For those who are more stable, and for whom the possibility of dying was identified more than 48 hours prior to death, the use of a hospice may be possible, beneficial and appropriate given the relatively low hospice bed occupancy in the first wave and the likely exponential increase in hospital bed pressures over winter.10 This data did not determine how such patients would be identified and more research is needed on this.

A third of patients were admitted from nursing homes and hospital admission may not have enhanced their care. Improved communication between hospices, care homes and GP services could increase the number of patients able stay at home or be directly admitted to hospices for the dying phase if symptoms are problematic.

Overall, syringe drivers and anticipatory medication were prescribed in a similar percentage in COVID-19 deaths compared with non COVID-19 deaths (where they were prescribed in 37% and 89% respectively).11 Where the possibility of dying was identified closer to death, patients required more reactive medication administrations and were less likely to be prescribed a syringe driver. It is our opinion that there should be a low threshold for prescribing symptom control medications for those with prognostic uncertainty.

The collection of this large regional dataset required collaboration and utilized multiple personnel. Individuals all had palliative care experience and variance in entry requirements was reduced by a data entry guide. Due to the novel nature of COVID-19, timeframes reported related to the possibility of dying rather than the diagnosis of dying.

Conclusions

This large multi-center study comprehensively describes COVID-19 deaths in hospitals. The possibility of dying was recognized in a vast majority, leading to anticipatory prescribing for commonly experienced symptoms in over 90%. A proportion of patients may be stable enough to consider alternative options for end of life care, potentially enhancing hospice utilization and optimizing acute hospital beds use. Community based advance care planning may be able to identify those who don't want and/or would not benefit from hospital admission.

Disclosures

The named authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr Daniel Stow PHD from Newcastle University who provided statistical consultation.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Wu Z, McGoogan J. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Etkind S, Bone A, Lovell N. The role and response of palliative care and hospice services in epidemics and pandemics: a rapid review to inform practice during the COVID-19 pandemic/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.029. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e31–e40. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selman LE, Chao D, Sowden R, Marshall S, Chamberlain C, Koffman J. Bereavement support on the frontline of COVID-19: recommendations for hospital clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e81–e86. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.024. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32376262%0A. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC7196538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lovell N, Maddocks M, Etkind SN. Characteristics, symptom management and outcomes of 101 patients with COVID-19 referred for hospital palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e77–e81. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hetherington L, Johnston B, Kotronoulas G, Finlay F, Keeley P, McKeown A. COVID-19 and hospital palliative care – a service evaluation exploring the symptoms and outcomes of 186 patients and the impact of the pandemic on specialist hospital palliative care. Palliat Med. 2020;34:1256–1262. doi: 10.1177/0269216320949786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson T, Hobson K, Clare H, Weegmann D, Moloughney C, McManus S. End-of-life care in COVID-19: an audit of pharmacological management in hospital inpatients. Palliat Med. 2020;34:1235–1240. doi: 10.1177/0269216320935361. 2020;34(9):1235–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turner J, Eliot Hodgson L, Leckie T, Eade L, Ford-Dunn S. A dual-centre observational review of hospital based palliative care in patients dying with COVID-19. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.031. e75–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32387139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing symptoms (including at the end of life) in the community. Natl Inst Heal Care Excell. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NICE COVID-19 rapid guideline: critical care in adults. Natl Inst Heal Care Excell. 2020:2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradshaw A, Dunleavy L, Walshe C. Understanding and addressing challenges for advance care planning in the COVID-19 pandemic an analysis of the UK CovPall survey data from specialist palliative care services. medRxiv. 2020:1–30. doi: 10.1177/02692163211017387. Available from: https://medrxiv.org/cgi/content/short/2020.10.28.20200725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership . 2019. National Audit of Care at the End of Life. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliver D. What to say when patients are “sick enough to die”. BMJ. 2019;367:6–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]