Abstract

Objective:

The present study aimed to assess preoperative levels of patient anxiety and pain before root canal treatment, and to explore variables that may affect these levels.

Methods:

Ninety-five patients presenting for an endodontic visit were recruited for the study. A questionnaire was administered. Visual analog scales were used to record levels of pain and anxiety. Data was tabulated, and analysis was performed using the Pearson Chi-Squire test with continuity correction, and the level of significance was set at 0.05 (P=0.05).

Results:

Anxiety was detected more frequently in females (60%) than in males (33%) (P=0.016). Sixty-two percent of patients who were waiting for a new treatment were anxious, compared to 39% of those who were returning to continue treatment (P=0.049). Sixty-nine percent of patients in pain reported being anxious (P=0.015). Patients aged 18–30 years reported more pain than those older than 30 years (P=0.023). Forty-three percent of new patients reported being in pain, whereas only 20% of patients returning for a treatment reported pain (P=0.027).

Conclusion:

Anxiety associated with root canal treatment is prevalent, and it was reported primarily by young females who were presenting for a new treatment. Pain and anxiety are highly inter-related, and they are usually reduced after the first endodontic session.

Keywords: Anxiety, endodontics, pain, dental fear

HIGHLIGHTS.

Dissimilarities in the perception of dental fear and anxiety associated with root canal treatments among American individuals.

Dental pain is a very significant reason for fear and anxiety among the younger individuals when they are visiting for an endodontic appointment for the first time.

The first appointment is very critical because the clinicians can minimize patient perceptions regarding the pain and anxiety in the consecutive appointments.

Endodontists should be aware of the possible influence of gender and age based on dental fear and anxiety during the endodontic treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Dental anxiety is a common disorder that hinders patient compliance, and it is correlated with poor oral status (1), and may lead to avoidance of dental care. A traumatic dental experience during childhood is often associated with succeeding dental anxiety (2). A patient’s sex is an essential factor, and females report higher levels of dental anxiety than did males (3-5). Older patients can exhibit comparatively lower levels of anxiety (6), which may be a result of having fewer teeth and fewer dental visits, or they may be less likely to report pain. It has been reported that anxious patients tend to have lower pain thresholds, especially in the oral region (7). Anxious patients may also overestimate pain, and thus may require more chairside time spent on stress reduction. This extra chairside time could potentially increase the level of stress experienced by both the patient and the dental provider (8). The effects of other variables on dental anxiety, including the level of education, income, and occupation, have been studied, but they were not strongly associated with dental anxiety (9).

A recent systematic review suggests that in addition to age, sex, and ethnicity, previous non-surgical endodontic treatment may also influence dental anxiety (10). It has also been reported that root canal treatment and oral surgery are the two procedures most likely to induce dental anxiety (11). Results of a survey conducted by the American Association of Endodontics showed that typically, public perceptions of root canal treatment were negative and that this was mainly due to reports of pain associated with the dental procedure (12). Wali et al. (13) reported that 13% of 200 patients canceled an endodontic appointment because of fear of pain. Most prior research investigating anxiety has focused on comprehensive dental treatment. There is a lack of scientific evidence concerning dental anxiety associated with endodontic treatment. Hence, the present study aimed to assess preoperative anxiety and pain levels while waiting to receive endodontic treatment and to investigate variables that may affect anxiety and pain levels in these patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

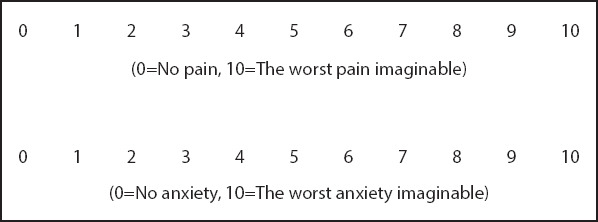

Ethical approval for the study was given by the institutional review board of New York University’s Langone Health Center (study #: S12-02348). Patients attenting the Department of Endodontics for an endodontic visit were recruited in the study. Study investigators asked the patient if he/she was willing to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria were: (a) Subjects must be above 18 years old. (b) Subjects must read and speak English fluently. (c) Subjects must be willing to provide verbal consent. (d) Subjects must have appointment for initianting or continuation of non-surgical root canal treatment. Exclusion criteria were: (a) Pregnant females. (b) Subjects were unwilling or unable to provide verbal consent. (c) Subject with special needs. (d) NYU employees and students. In accordance with a previous study (14) in the current study, a power analysis was conducted based on an estimation that 40% of subjects would be anxious prior to treatment. The power analysis indicated that 94 cases are required to detect a group difference of at least 26 vs. 54% with a 95% confidence interval and 80% power in a z-test for independent proportions. All the patients who fullfied inclusion creteria were given a questionnaire (Table 1) to complete before the appointment, and the questions in the survey included dependent variables (pain and anxiety) and independent variables (including sex, ethnicity, age, socioeconomic status, and dental history). Patients reported their levels of pain and anxiety via visual analog scales (VASs) (15, 16): “VAS-P” for pain and “VAS-A” for anxiety (Fig. 1). Pain and anxiety levels were dichotomized to either ≤3 (no pain/anxiety group) or ≥4 (pain/anxiety group) (17, 18). Name, date of visit, and other potentially identifying information were not collected.

TABLE 1.

Questionnaire items and their association to pre-operative pain or anxiety or both. In questions with more than two variables, the one with a significant difference is marked with “†” for anxiety and “‡” for pain

| Question/Answer | n (%) |

| 1) What is your gender?† | |

| Male | 42 (44.2) |

| Female | 53 (55.8) |

| Total | 95 (100) |

| 2) What is your ethnicity? | |

| Caucasian | 33 (34.7) |

| African-American | 16 (16.8) |

| Hispanic | 23 (24.2) |

| Other | 23 (24.2) |

| Total | 95 (100) |

| 3) What is your age? | |

| 18 – 30 ‡ | 28 (29.5) |

| 31 - 40 | 18 (18.9) |

| 41 - 50 | 20 (21.1) |

| 51 - 60 | 14 (14.7) |

| Above 60 | 15 (15.8) |

| Total | 95 (100) |

| 4) Is the cost of this treatment a concern? | |

| Yes | 47 (49.5) |

| No | 39 (41.1) |

| I don’t know | 9 (9.5) |

| Total | 95 (100) |

| 5) What is your level of education? | |

| 12 years or less | 15 (15.8) |

| College level | 55 (57.9) |

| Graduate level | 20 (21.1) |

| Post graduate level | 5 (5.3) |

| Total | 95 (100) |

| 6) How often do you visit your dentist for a regular checkup? | |

| Every 6 months | 33 (34.7) |

| Every 6-12 months | 27 (28.4) |

| More than every 12 months | 14 (14.7) |

| I don’t visit my dentist for a regular dental checkup | 21 (22.1) |

| Total | 95 (100) |

| 7) Are you employed? | |

| Yes, full time | 38 (40.0) |

| Yes, part time | 20 (21.1) |

| No, I’m unemployed | 37 (38.9) |

| Total | 95 (100) |

| 8) How long have you been waiting today for your root canal treatment? | |

| Less than 15 minutes | 56 (58.9) |

| More than 15 minutes | 39 (41.1) |

| Total | 95 (100) |

| 9) Using the scale of 0 to 10 (0= no pain, 10= the most intense pain you have ever experienced),please slide to the level of pain you are experiencing now?† | |

| Not in pain ≤3 | 66 (69.5) |

| In pain ≥4 | 29 (30.5) |

| Total | 95 (100) |

| 10) Have you taken any medication to reduce your pain in the last 4 hours?‡ | |

| Yes | 12 (12.6) |

| No | 83 (87.4) |

| Total | 95 (100) |

| 11) Using the scale of 0 to 10 (0=no anxiety, 10=the most amount of anxiety that you have ever experienced),please slide to the level of anxiety you are feeling now?‡ | |

| Not anxious ≤3 | 37 (38.9) |

| Anxious ≥4 | 58 (61.1) |

| Total | 95 (100) |

| 12) Have you taken any medication to reduce your anxiety in the last 4 hours? | |

| Yes | 5 (5.3) |

| No | 90 (94.7) |

| Total | 95 (100) |

| 13) At today’s session, are you having a new treatment initiated or a continuation of a treatment | |

| that was previously initiated?‡† | |

| New treatment | 42 (45.2) |

| Previously initiated | 51 (54.8) |

| Total | 95 (100) |

| 14) Have you met the dentist who is going to perform the root canal treatment?‡ | |

| Yes | 71 (74.7) |

| No | 24 (25.3) |

| Total | 95 (100) |

| 15) If you are continuing previously initiated treatment, is the dentist the same person that initiated the treatment? | |

| Yes | 37 (68.5) |

| No | 17 (31.5) |

| Total | 54 (100) |

| 16) When did you have your last root canal treatment? | |

| Within the last 6 months | 20 (21.1) |

| Between 6-12 months ago | 8 (8.4) |

| Over 1 Year ago | 35 (36.8) |

| I don’t remember | 17 (17.9) |

| I never had a root canal treatment | 15 (15.8) |

| Total | 95 (100) |

| 17) When did you have your last dental (other than root canal) treatment? | |

| Within the last 6 months | 60 (63.2) |

| Between 6-12 months ago | 10 (10.5) |

| Over 1 Year ago | 19 (20.0) |

| I don’t remember | 6 (6.3) |

| Total | 95 (100) |

| 18) What was the gender of the dentist who performed your last treatment? | |

| Male | 54 (56.8) |

| Female | 41 (43.2) |

| Total | 95 (100) |

| 19) Using the scale of 0 to 10 (0=the worst dental experience, 10=the best dental experience you have ever had),please grade your last root canal experience | |

| Bad ≤3 | 20 (21.1) |

| Good ≥4 | 75 (78.9) |

| Total | 95 (100) |

| 20) Using the scale of 0 to 10 (0=the worst dental experience, 10=the best dental experience that you have ever had),please grade your last dental (other than root canal) experience? | |

| Bad ≤3 | 26 (27.4) |

| Good ≥4 | 69 (72.6) |

| Total | 95 (100) |

Figure 1.

Visual analogue scale for pain and anxiety

Data were imported into a Microsoft® Excel® spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) to which only the principal investigators had access. Data analysis was performed using the Pearson Chi-Squire statistical test with continuity correction. IBM SPSS (v.22, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all analyses, and P<0.05 was deemed to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Ninety-five patients participated in the current study (42 males and 53 females). The cumulative responses to all questions are summarized in Table 1. The mean pain (VAS-P) score was 2.7 (SD 3.5), and the mean anxiety (VAS-A) score was 4.64 (SD 3.2). There was week positive correlation between pain and anxiety (Fig. 2). Reported anxiety was more common in females than in males (60% vs. 33%; P=0.016) (Table 2). Sixty-two percent of patients who were waiting for a new treatment reported anxiety, compared to 39.2% who were returning to continue treatment (P=0.049). Sixty-nine percent of patients in pain reported being anxious, which was significantly more than the percentage of those who reported not being in pain (P=0.015).

Figure 2.

Week positive correlation between pain and anxiety

TABLE 2.

Relationships between anxiety and variables with significant associations

| Variable | Patients n (%) | Anxious patients’ n (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 42 (44.2) | 14 (33.3) | 0.016 |

| Female | 53 (55.8) | 32 (60.4) | |

| New treatment or a continuation | |||

| New treatment | 42 (45.2) | 26 (61.9) | 0.049 |

| Continuation of treatment | 51 (54.8) | 20 (39.2) | |

| Pain | |||

| Not in pain | 66 (69.5) | 26 (39.4) | 0.015 |

| In pain | 29 (30.5) | 20 (69.0) |

Patients aged 18–30 years were more likely to report pain than those aged >30 years (P=0.023; Table 3). Forty-three percent of new patients reported being in pain, compared to 20% of patients returning for treatment (P=0.027). The prevalence of pain when patients had not previously met their dental care provider was 54.2%, and when they had previously met their dental care provider, it was 22.5% (P=0.008). Thirty-three percent of patients on pain medication reported either no pain or only slight pain, while 66.7% of patients on pain medication reported pain (P=0.010). None of the other variables investigated yielded any significant differences pertaining to preoperative pain or anxiety.

TABLE 3.

Relationships between pain and variables with significant associations

| Variable | Patients n (%) | Patients in pain n (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 18–30 years | 28 (29.5) | 14 (50.0) | 0.023 |

| 31–40 years | 18 (18.9) | 3 (16.7) | |

| 41–50 years | 20 (21.1) | 8 (40.0) | |

| 51–60 years | 14 (14.7) | 2 (14.3) | |

| >60 years | 15 (15.8) | 2 (13.3) | |

| New treatment or a continuation | |||

| New treatment | 42 (45.2) | 18 (42.9) | 0.027 |

| Continuation of treatment | 51 (54.8) | 10 (19.6) | |

| Had previously met the dentist | |||

| Yes | 71 (74.7) | 16 (22.5) | 0.008 |

| No | 24 (25.3) | 13 (54.2) | |

| Taking pain medication | |||

| Yes | 12 (12.6) | 8 (66.7) | 0.010 |

| No | 83 (87.4) | 21 (25.3) |

DISCUSSION

A recent study from Australia reported that the anxiety and fear in endodontics are influenced by ethnicity (19). Conversely, ethnicity was not significantly associated with anxiety in the present study. This could be related to the different ethnic groups were studied in our study and thiers. Other variables that were not significantly associated with pretreatment pain or anxiety in the current study included the cost of treatment, frequency of dental visits, employment status, level of education, and anxiety medications. In a previous study, patients who did not visit the dentist regularly experienced more anxiety, as did patients with higher education (14). This could be related the methodology that used in that study since they used State-Trait Anxiety Inventory scale STAI, while we used VAS. However, a Brazilian study reported that anxiety was inversely associated with knowledge in patients undergoing root canal treatment (5). As noticed, education is not consistent among the studies. A study (20) observed that the longer patients wait in the reception area, the more anxiety they report; nevertheless, this was not witnessed in the present study. The reason behind that is that study had subjects were all anxious and referred for sedation to manage their anxiety during the dental treatment. On the other hand, our subjects were not all anxious.

Sixty-nine percent of patients that reported pain were also anxious, which is agreement with the findings of a previous study investigating relationships between pain and anxiety (21). Anxiety and pain were significantly associated with each other in the present study. This finding supports the premise that fear of endodontic treatment may be more of a psychological factor, rather than biological (e.g., due to pain) (22, 23). The observation in the present study that anxiety was more common in females than in males is consistent with the findings of previous studies (5, 8, 21).

Anxiety and pain were lower with consecutive appointments when the appointment was for the continuation of a procedure that had already commenced as opposed to a new procedure. It has previously been reported that patients’ expectations at emergency dental visits include reduction of symptoms and an explanation pertaining to the cause of the problem (24). During the first appointment, treatment options and their associated risks and benefits, likely outcomes, and postoperative requirements are explained to a patient. During this session, a patient’s questions can be answered. If the patient is in pain, emergency treatment aimed at reducing their symptoms may also be administered. This process may help the patient understand the proposed treatment better, and as a result, reduce their anxiety before and during subsequent sessions. Another possibility is that during visits after the first treatment session, the patient comes to realize that the treatment is less painful than they initially expected, and thus, they become less anxious during those subsequent visits. Positive interaction with the provider is another variable that has been associated with reduced patient anxiety (25).

Patients aged 18–30 years reported more pain and anxiety than those in other age groups. These findings are concordant with those of previous studies investigating anxiety levels (5, 9) and pain levels (25, 26) in this context and associations between those levels and age. With regard to pain and/or anxiety medication, in the present study, 33% of patients who took pain medication reported only being in slight pain or reported no pain at all (P=0.010). This observation was statistically significant, but due to the low number of patients taking pain medication (n=12), we do not believe this finding can be generalized to a broader clinical context. In the current study, whether pain medications were prescribed to the patient or were self-prescribed was not investigated; nevertheless, this finding may indicate either unnecessary use of pain medications or pain reduction due to the effects of the medication. There was no significant association between taking anxiety medications and experiencing pain. Again, due to the very low number of patients taking anxiety medications (n=5), no firm conclusions can be drawn from this observation.

The present study had limitations. The VASs used are considered valid by some studies (15, 27, 28), but other studies have used the Dental Anxiety Scale (10, 29, 30). In addition, when assessing levels of pain and anxiety, it is better to compare the same patient before and after treatment to evaluate variables relating to the treatment and the clinician. Another point warranting consideration is that the majority of the subjects in the study did not report any pain. In order to better assess pain and anxiety, it may be better to conduct a similar study involving patient types who tend to present to the dental emergency room reporting pain and/or anxiety.

CONCLUSION

In the current study, anxiety associated with endodontic treatment was prevalent, and it was most common in females visiting for a new treatment. Dental pain was most common in younger patients (aged 18–30 years) undergoing endodontic treatment and in those visiting for a new treatment. Pain and anxiety are highly inter-related, and both usually diminish after the first endodontic treatment session.

Acknowledgement:

The authors would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research of Majmaah University for supporting this work under Project Number No. R-1441-129.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Ethics Committee Approval: The study was approved by the institutional review board of New York University College of Dentistry, New York, United States (study #: S12-02348).

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Financial Disclosure: None declared.

Authorship contributions: Concept – D.K., R.H., P.A.R.; Design – R.A., M.M., J.C.; Supervision – D.K., M.M., P.A.R.; Funding - None; Materials - R.A., R.H., D.K.; Data collection &/or processing – R.A., D.K., J.C.; Analysis and/or interpretation – R.A., R.H., M.M.; Literature search – R.A., J.C., R.H.; Writing – R.A., J.C., R.H.; Critical Review – P.A.R., R.H., M.M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berggren U, Meynert G. Dental fear and avoidance:causes symptoms, and consequences. J Am Dent Assoc. 1984;109(2):247–51. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1984.0328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eli I, Uziel N, Baht R, Kleinhauz M. Antecedents of dental anxiety:learned responses versus personality traits. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25(3):233–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armfield JM, Slade GD, Spencer AJ. Dental fear and adult oral health in Australia. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37(3):220–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2009.00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liddell A, Locker D. Gender and age differences in attitudes to dental pain and dental control. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25(4):314–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peretz B, Moshonov J. Dental anxiety among patients undergoing endodontic treatment. J Endod. 1998;24(6):435–7. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(98)80028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liddell A, Locker D. Dental anxiety in the elderly. Psych Health. 1993;8(2-3):175–83. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klepac RK, McDonald M, Hauge G, Dowling J. Reactions to pain among subjects high and low in dental fear. J Behav Med. 1980;3(4):373–84. doi: 10.1007/BF00845291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hmud R, Walsh L. Dental anxiety:causes complications and management approaches. International Dentistry SA. 2007;9(5):6–14. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neverlien PO. Normative data for Corah's Dental Anxiety Scale (DAS) for the Norwegian adult population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1990;18(3):162. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1990.tb00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan S, Hamedy R, Lei Y, Ogawa RS, White SN. Anxiety Related to Nonsurgical Root Canal Treatment:A Systematic Review. J Endod. 2016;42(12):1726–36. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong M, Lytle WR. A comparison of anxiety levels associated with root canal therapy and oral surgery treatment. J Endod. 1991;17(9):461–5. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(07)80138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Association of Endodontists. Public education report:surveys document more people choosing root canal therapy over extraction. Chicago, IL: American Association of Endodontists; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wali A, Siddiqui TM, Gul A, Khan A. Analysis of level of anxiety and fear before and after endodontic treatment. J Dent Oral Health. 2016;2(3):19–21. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stouthard ME, Hoogstraten J. Prevalence of dental anxiety in The Netherlands. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1990;18(3):139–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1990.tb00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Facco E, Zanette G, Favero L, Bacci C, Sivolella S, Cavallin F, et al. Toward the validation of visual analogue scale for anxiety. Anesth Prog. 2011;58(1):8–13. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006-58.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huskisson EC. Measurement of pain. Lancet. 1974;2(7889):1127–31. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)90884-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Price DD, McGrath PA, Rafii A, Buckingham B. The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain. 1983;17(1):45–56. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Appukuttan D, Vinayagavel M, Tadepalli A. Utility and validity of a single-item visual analog scale for measuring dental anxiety in clinical practice. J Oral Sci. 2014;56(2):151–6. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.56.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter AE, Carter G, Boschen M, AlShwaimi E, George R. Ethnicity and Pathways of Fear in Endodontics. J Endod. 2015;41(9):1437–40. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen SM, Fiske J, Newton JT. The impact of dental anxiety on daily living. Br Dent J. 2000;189(7):385–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vassend O. Anxiety pain and discomfort associated with dental treatment. Behav Res Ther. 1993;31(7):659–66. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90119-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter AE, Carter G, George R. Pathways of fear and anxiety in endodontic patients. Int Endod J. 2015;48(6):528–32. doi: 10.1111/iej.12343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu SM, Bellamy HA, Kogan MD, Dunbar JL, Schwalberg RH, Schuster MA. Factors that influence receipt of recommended preventive pediatric health and dental care. Pediatrics. 2002;110(6):e73. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.6.e73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson R. Patient expectations of emergency dental services:a qualitative interview study. Br Dent J. 2004;197(6):331–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4811652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watkins CA, Logan HL, Kirchner HL. Anticipated and experienced pain associated with endodontic therapy. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133(1):45–54. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horst OV, Cunha-Cruz J, Zhou L, Manning W, Mancl L, DeRouen TA. Prevalence of pain in the orofacial regions in patients visiting general dentists in the Northwest Practice-based REsearch Collaborative in Evidence-based DENTistry research network. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146(10):721–8. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kindler CH, Harms C, Amsler F, Ihde-Scholl T, Scheidegger D. The visual analog scale allows effective measurement of preoperative anxiety and detection of patients'anesthetic concerns. Anesth Analg. 2000;90(3):706–12. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200003000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luyk NH, Beck FM, Weaver JM. A visual analogue scale in the assessment of dental anxiety. Anesth Prog. 1988;35(3):121–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corah NL, Gale EN, Illig SJ. Assessment of a dental anxiety scale. J Am Dent Assoc. 1978;97(5):816–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1978.0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corah NL. Development of a dental anxiety scale. J Dent Res. 1969;48(4):596. doi: 10.1177/00220345690480041801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]