Abstract

Background:

Although disparities in cancer rates, later diagnoses and lower survival rates between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people have been documented, little is known about how Indigenous patients with cancer encounter the health care system. We explored perceptions and experiences of Indigenous patients with cancer and their families to understand better how 2 key concepts — trust and world view — influence cancer care decisions.

Methods:

In this patient-oriented study that included participation of 2 patient partners, qualitative data were collected from Indigenous patients with cancer and their families using an Indigenous method of sharing circles. The sharing circle occurred at a culturally appropriate place, Wanuskewin Heritage Park, Saskatoon, on Sept. 22, 2017. The first patient partner started the sharing circle by sharing their cancer journey, thus engaging the Indigenous methodology of storytelling. This patient partner was involved in selecting the data collection method and recruiting participants through snowballing and social media. Trust and world view were employed as meta themes to guide our examination of the data. In keeping with Indigenous methodology, interview transcripts were analyzed using narrative analysis. The themes were reviewed and verified by a second Indigenous patient partner.

Results:

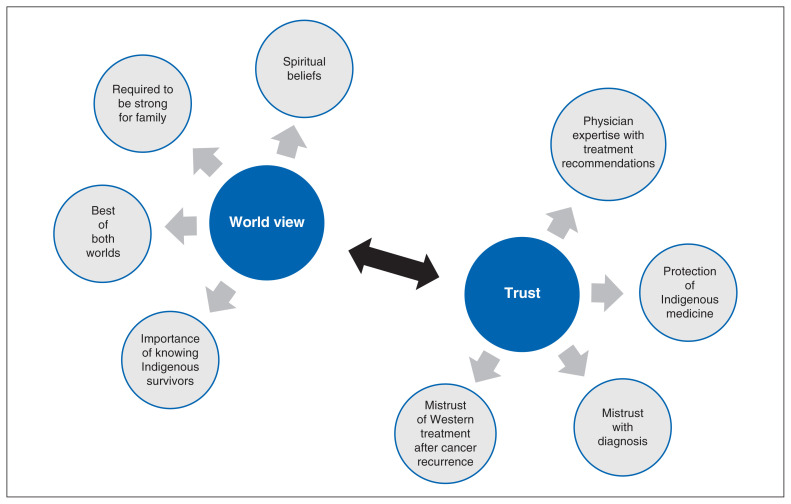

There were 14 participants in the sharing circle. The 2 meta themes, trust and world view, comprised 8 subthemes. The meta theme trust included mistrust with diagnosis and Western treatment after cancer therapy, protection of Indigenous medicine and physician expertise with treatment recommendations. The world view meta theme included the following subthemes: best of both worlds, spiritual beliefs, required to be strong for family and importance of knowing Indigenous survivors.

Interpretation:

This study displayed complex relations between trust and world view in the cancer journeys of Indigenous patients and their families. These findings may assist health care providers in gaining a better understanding of how trust and world view affect the decision-making of Indigenous patients regarding cancer care.

Plain language summary: Considering the differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada regarding rates of common cancer, later stage diagnosis and lower survival, we took the opportunity in this patient-oriented study to understand how Indigenous patients experience the health care system. Our specific aim was to understand how trust and world view of Indigenous people affected their personal cancer journey. A patient partner (an Indigenous patient with cancer) led this research with the researchers’ support. After the patient partner recruited 14 participants, a sharing circles protocol was guided by a circle keeper, and the patient partner began by sharing their story. By using sharing circles, a traditional Indigenous practice that provides a safe, culturally appropriate environment to share experiences, we gathered information from patients and their families. We organized the participant stories into themes that reflected their experiences with trust and world view and had these reviewed by another Indigenous cancer survivor. Participants were both trusting and mistrusting of the health care system, which seemed to connect with how well health care providers accepted their world view. Trusting that Indigenous medicine would be protected was also important. Spiritual beliefs, being strong for family and knowing Indigenous survivors were important to participants. Other participants embraced both Indigenous and Western perspectives. Because this patient-oriented study used an Indigenous method, as researchers, we strengthened our ties with Indigenous communities and furthered the dialogue on Indigenous experiences with health care.

Indigenous Peoples (First Nations, Métis and Inuit) in Canada are diagnosed with common cancers at a higher rate,1–5 are more likely to receive diagnoses at a later stage6 and have lower survival rates7,8 relative to non-Indigenous Canadians. Indigenous patients with cancer tend to rely on the connection among family, culture and spirituality9,10 to cope during their cancer journey. Much of what is currently known about the experiences of Indigenous patients with cancer is limited to epidemiological studies7 or focused on spirituality.11,12 Past research does not necessarily provide insight into how to improve their experiences. Although access issues have been identified as obstacles in some provinces,13 little is known about how Indigenous patients with cancer encounter the health care system in Saskatchewan, Canada.

Trust and world view have been shown to play an important role in how Indigenous patients interact with the health care system.14 Reciprocal respect, perception of world view acceptance and culturally appropriate knowledge translation influence level of trust.11 Indigenous patients often hold different world views from those of providers and the health care system.15 Building on our literature-derived theory of shared decision-making for Indigenous patients,14 our study explores the perceptions and experiences of Indigenous patients with cancer and their families to understand how trust and world view influence their cancer care decisions. We engaged 2 Indigenous cancer survivors to partner in our research to ensure that our work maintained a patient-oriented lens.

Methods

Study design and setting

Our study is a patient-oriented qualitative analysis that used a data-gathering practice suitable to an Indigenous population, sharing circles, conducted under the guidance of the first patient partner, L.A., a cancer survivor.16,17

Preparation for data collection occurred over the 2 weeks leading to the sharing circle, which was held on 1 day, Sept 22, 2017. During this preparation period, the patient partner assisted with educating the other researchers in protocol and selecting an Elder and circle keeper. The setting for the circle was the Wanuskewin Heritage National Park, 20 km north of Saskatoon. The park is a living reminder of the sacred relationship between the land and the Indigenous Peoples.18 Chosen by the patient partner, this location was intended to provide participants with a culturally relevant environment to assist in reducing power imbalance between researchers and participants.

Participants

A convenience sample of participants was recruited by the first patient partner. A cancer survivor and a well-known, respected member of several Indigenous communities and organizations, the patient partner contacted and invited 33 Indigenous patients with cancer and their families to participate in the sharing circle. Eligibility for inclusion was connection to the patient partner, self-identification as Indigenous, and receipt of past or ongoing treatment for cancer or being a family member of a patient with cancer or a cancer survivor. Participants were not excluded based on their distance from Saskatoon or whether they resided inside or outside of an Indigenous community. The majority of participants (n = 9) identified as patients, though all participants had family members who had experienced cancer. All study participants received an honorarium for participation.

Data collection

Data collection took place in a single sharing circle. The details of the sharing circle protocol have been published,16 and our data collection was conducted according to customs of sharing circles.17,19–21 In addition to the study participants, 3 members of the research team (the first patient partner, a circle keeper [R.R.] and the principal investigator [T.C.]), took part in the circle. The gathering began with a meal, then the researchers explained the study and facilitated the signing of informed consent.

Prior to data collection, an Elder (a person recognized within the Indigenous communities as being knowledgeable and supportive of traditional ceremonies, protocols and songs22) was offered tobacco by the researchers on behalf of the project; the Elder responded with a prayer in the Cree language. The Elder did not participate in the circle.

The circle keeper led the data collection phase and ensured the relevant customs of the communities were observed. The circle was opened by the circle keeper, who offered smudging to the participants. Because of the nature of the sharing circles methodology, the circle keeper guided participants to share their cancer experiences freely, without prescripted questions. Because of the familiar cultural aspects of the methodology, it was not necessary to provide participants with detailed instructions regarding the structure and protocol of the sharing circles.

The Indigenous patient partner started the sharing circle by sharing thier cancer journey. Next, a small stone was passed in a clockwise manner and whoever held the stone shared whatever they felt comfortable sharing until every participant, including the principal investigator, had shared a single time.

The principal investigator (who does not identify as an Indigenous person) was invited into the circle by the other participants and was the final member of the circle to share. As an evaluator of health support programs for Indigenous Peoples,23 the investigator had participated in many healing sharing circles and had also taken part in ceremonies with the circle keeper. Although the principal investigator shared at the end of the circle to thank participants and add their own family experiences with cancer, this transcription was not included with the data.

After the sharing circle protocol was completed, participants were debriefed by the patient partner. The sharing circles were audio-recorded, and the data were sent to a transcription service (Social Sciences Research Laboratories at the University of Saskatchewan) for verbatim transcription.

Patient engagement

Two patient partners participated in our research. The first patient partner, L.A., is an Indigenous cancer survivor who was connected to the research team by a member of the provincial First Nations and Métis Health Service.

In this current study, the first patient partner was instrumental by sharing their experiences, informing the data-gathering method (i.e., sharing circles) and recruiting participants through their social network. They also influenced our sharing circles methodology, helping the research team in navigating the identification of participants’ cultural background and leading the cultural protocols of sharing circles.

During the sharing circles, in conjunction with the circle-keeper, the first patient partner helped facilitate the established protocol within the community. As they were the first participant commencing the sharing circles and the topic of discussion, they initiated the tone of the circle. We relied on their reflexive ability as a cancer survivor and role in the community to support and encourage the sharing of other participants. Although the first patient partner was an important research partner during much of the study, they did not play an active role in data analysis. They offered comments on the final manuscript before submission.

A second Indigenous patient partner, who was a cancer survivor, a patient navigator and a patient advisor from another study on Indigenous cancer support needs, verified our analysis. This patient partner did not participate in our sharing circle but played the role of a partial patient partner in the study. We asked this patient partner to participate because of their patient navigation experience in the Indigenous community in the northern Saskatchewan region. Given the limited, yet important, role that they played, the second patient partner was acknowledged in our study.

Data analysis

In alignment with Indigenous methodology,17–21 we chose to conduct a thematic narrative analysis in which the context within the text is the main focus.24 Our 2 key concepts were trust and world view and how they influenced the shared decision-making of Indigenous patients with lived cancer experiences and their families.12,25–27

Excel was used to house the transcript data, and the analysis was conducted in several phases. We used our 2 key concepts as primary themes to guide the analysis. First, taking a deductive approach, 1 reviewer (A.A.) manually searched the transcripts for references to the key concepts of trust and world view. This phase included reading and rereading the transcripts and highlighting relevant sections; these findings were then verified by a second reviewer (T.C.). The highlighted sections were organized (A.A.) in a chart format to ensure the identified themes matched the patient and family narratives.

T.C. and A.A. performed the remainder of the analysis. We coded the data based on keywords from the participant quotes related to trust and world view. These keywords were then sorted into subthemes, which were related to trust and world view. For an example of this phase of the analysis, see Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/8/4/E852/suppl/DC1.

Because of our deductive analytical approach, we reached saturation once we had exhausted the representation of trust and world view in the data.24,28 In the final analysis, there were 8 tables of grouped subthemes that were collated into the 2 meta themes.

To ensure the validity of our analysis of the transcript data, the second patient partner verified our results. They provided further insight into our analysis and emphasized that Indigenous patients from the north tend to trust their physicians.

Ethics approval

The study received ethics approval from the University of Saskatchewan’s Behavioural Research Ethics Board.

Results

Of the 33 individuals who were invited to participate, only 14 agreed. We held 1 sharing circle that included 14 study participants and 3 researchers (1 patient partner, the circle keeper and the principal investigator), which lasted about 2 hours. Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. All participants self-identified as either First Nations or Métis, residing in 7 communities within 200 km of Saskatoon. Nine participants identified as patients and 5 identified as family members. Most participants were female (n = 10). The length of time since diagnosis ranged from 1 year to 37 years, with 4 participants having a diagnosis within 5 years. Two participants resided in urban areas, 6 were from small urban areas, 4 lived in rural areas and 2 lived on reserve.

Table 1:

Characteristics of Indigenous patients with cancer and their families who participated in a sharing circle (n = 14)

| Characteristic | No. of participants |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 4 |

| Female | 10 |

| Who attended | |

| Patients | 9 |

| Family members | 5 |

| Geographical location | |

| Reserve | 2 |

| Rural | 4 |

| Small urban | 6 |

| Urban | 2 |

| Types of cancer*† | |

| Bladder | 1 |

| Breast | 4 |

| Cervical | 1 |

| Colon | 1 |

| Ovarian | 1 |

| Uterine | 1 |

| Unknown | 1 |

| Illness trajectory† | |

| Remission or monitoring | 5 |

| Undergoing active treatments | 1 |

| Recurrence | 3 |

| Time since diagnosis, yr† | |

| < 5 | 4 |

| 5–10 | 2 |

| > 10 | 2 |

| Unknown | 1 |

One patient had more than 1 type of cancer diagnosed.

For patients only.

We used 2 meta themes — trust and world view — to guide our analysis. Each meta theme included 4 subthemes (Figure 1). For trust, the 4 subthemes were mistrust with diagnosis, protection of Indigenous medicine, physician expertise with treatment recommendations and mistrust of Western treatment after cancer therapy. For world view, the 4 subthemes were best of both worlds, spiritual beliefs, required to be strong for family and importance of knowing Indigenous survivors. The interconnections between the meta themes are described below.

Figure 1:

Connections between the meta themes and subthemes.

Meta theme: trust

Trust or lack of trust with the health care system and its providers was an important aspect of participants’ experiences during their cancer journey (Box 1). Although some participants described their accordance with “doctor knows best,” others preferred a second opinion to confirm diagnosis. Western treatments were especially considered suspect when cancer recurred, prompting participants to look to alternative treatments.

Box 1: Meta theme: trust.

Physician expertise with treatment recommendations

“And, I did what I had to do because I didn’t know what else there was to do. I figured the doctors, they’re the experts; they know what’s best for me. And, I believed in them; I trusted them. And I had a discussion with my mom and she asked me if I was going to do the treatment they had planned out. I said, ‘Yes.’ And, I felt it from her that she didn’t agree with it; she didn’t want me to do the chemo. And like me, thinking, ‘Mom, these are professionals, they know what they’re doing. I’m just going to do what they want, what they think is best for me.’” (Patient 9)

Mistrust with diagnosis

“So he sent me to do surgery right away. And I don’t know I just have no idea why but I told him, ‘I want a second opinion. I don’t want to just go into surgery and not know what’s going on.’ So he sent me to [specialized tertiary centre] and the surgeon there because they had already scheduled my surgery and everything, but I told them no I want a second opinion. And so anyway the ... he sent me to [specialized tertiary centre] and the doctor said, ‘Had they done that surgery there in [local hospital] it would’ve been the wrong one. So it’s good that you asked for the second opinion.’” (Patient 2)

“So then I went home to Saskatoon, made an appointment with my doctor and I had to fight with my doctor because I was young. [They] said, ‘I’m 99% sure that this isn’t cancer that you have.’ And I said, ‘Well I need you to do a mammogram.’ ‘Well you’re too young; they won’t.’ I said, ‘I need you to do a mammogram, just do it.’” (Patient 7)

Mistrust of Western treatment after cancer recurrence

“I said, ‘I want to live, I want to live. I want the best quality of life and I don’t think chemo is quality of life.’ To have to go through the pain and everything, I wanted to give up halfway through my first bout of chemo. ... So when I was diagnosed a second time, it was — no I know I’m not doing chemo. No. Two years ago and it’s back again, I’m going to try something else.” (Patient 9)

Protection of Indigenous medicine

“Everything’s getting better; I’m getting healthier and stronger, and she asked — that’s when [my doctor] said, ‘Well what are you doing?’ Yes I was doing the cannabis she knows, she knows I was drinking a lot of chaga tea and stuff like that. Eating healthy is the main thing, and, this lady that I’ve been seeing, she’s helped me a lot too throughout my journey. And I believe that’s why I’m still here today. And, I just tell the doctor I’m just doing the same thing. Only thing I’m going to share, because if I share any more what are they going to do with it? Are they going to go after her? Are they going to ban the stuff that she uses? Take that from her? For helping us, anybody that she’s helping.” (Patient 9)

When the second Indigenous patient partner reviewed our themes, they reported, based on their work as an Indigenous patient navigator, that patients in the more remote areas of northern Saskatchewan tended to be absolute in their trust of physician expertise. Their refinement of this meta theme indicated the complexity of trust’s role in decision-making.

Some participants shared a strong protective sentiment over their own medicines. Traditional healing practices tended not to be shared with health care providers because of previous stigmatizations. Participants viewed these more traditional healing practices as requiring protection from Western health care. Others refused to share as they perceived the threat of commercialization of the traditional medicine. In instances where doctors accepted that patients would try traditional forms of healing, a better therapeutic alliance with physicians was formed and trust increased. Most Indigenous patients initially had trust in the physician’s treatment recommendation; however, they often used traditional healing after the first round of cancer treatments.

Meta theme: world view

Strong adherence to Indigenous world view encompassed beliefs in the healing power of traditional ceremonies (Box 2). Similarly, there were many participants who blended “both ways”: belief in the Western health care system and trust in traditional healing, including ceremonies and medicine. Participants spoke of the need for both, to encourage Indigenous patients with cancer to engage in traditional healing practices and for the health care system to support traditional practices in facilities.

Box 2: Meta theme: world view.

Best of both worlds

“[Elder] was our way, and [Elder] was the white man’s way. ‘The best of both ways,’ [Elder] said. It’s the way I followed that, and [Elder] also said, ‘Do 4 ceremonies, sweat, dance, round dance, sun dance, use those as a support.’ And that’s what we try to do today. We go to these ceremonies. It’s amazing how it’s helped us.” (Family member 1)

Spiritual beliefs

“These things that we believe in — an eagle feather can help a person in the hospital, just have it by the pillow or a bag of sweet grass, makes them feel good and stronger. So I try to share that.” (Family member 1)

“And have come out stronger and survivors and have become warriors and examples for other people. We know that miracles happen, all have witnessed it. We know the Creator is powerful, we know that our ceremonies are powerful.” (Family member 4)

Required to be strong for family

“And I needed to be strong for my kids, I didn’t have time to panic, but I was panicking. I’m strong. I’m a strong, beautiful Indigenous woman with a strong voice, and I will use that voice to help all of us for our children and our grandchildren. Because, we need to be there for them. We need to set this foundation for them, we need to show them and we need to lead the way.” (Patient 6)

“And the youngest one was at home and that one was the hardest, because to him it was like, ‘My God my mom’s going to die, she has cancer.’ And he was 12 at the time. So, of course me being the strong one. ‘I’ll be okay, you don’t have to worry. I’m going to fight this and do whatever I have to do.’ And, he wanted to be there for me, but I didn’t want him to see me in pain. I didn’t want him to see me hurting and crying.” (Patient 9)

Importance of knowing Indigenous survivors

“So, I really like the story though about gathering of stories and, so that people have something to refer to. Our people know that there are avenues out there that are — people to help, there are things that exist that can help our people get through the — not only the physical, but the emotional trauma that impacts not only the person that has been afflicted with a cancer but the surrounding people in their support groups. I think that they’re just as important. That was it.” (Family member 4)

“And I just remember being in such despair and just feeling hopeless. And then I just thought I had to — I just got strong about something and I just thought, ‘[names self], there’s survivors. There’s survivors.’ And that’s when it hit me, this is not a death sentence. People have survived it. Then I got hope and then I just took off from there and, spoke to people.” (Patient 4)

Family relationships were especially salient for participants. Many of the participants described using inner strength fostered by their Indigenous identity to sustain themselves and their families. They expressed, unequivocally, the requirement to continue to be strong, despite cancer, to support their families and remain resilient.

A final aspect of Indigenous world view was the importance of community. Knowing Indigenous survivors was highly appreciated and valuable throughout their cancer journey. One participant noted how comforting it would have been to “see a brown face” at the cancer facility. Knowing there were other Indigenous survivors increased morale, and many participants spoke of the therapeutic value of the sharing circle itself.

Connections between meta themes

A final observation about the data was that the 2 meta themes, trust and world view, were connected in important ways (Figure 1). For example, when participants trusted that their use of Indigenous medicine was not at risk, they embraced both Western and Indigenous medicine. They were passionate in their defence of traditional medicines (Box 3), but also expressed trust in both Western medicine and traditional ceremony. These intersections show the complexities of the experiences of Indigenous patients living with cancer.

Box 3: Connections between meta themes.

Defence of Indigenous medicine

“We have to be careful of them [Western health care providers], very careful. Because we have to — we’re of the generation that has to preserve that, those medicines. And they are medicines. And we have to share these stigmas that go with it.” (Patient 10)

Western and Indigenous medicine

“In finding out something about your genes, my dad’s traditional. My dad, he sweats, he has led a rough life but he chose to go back to his roots. So what I can say with that finding out the genetics [of cancer diagnosis], I’ve been able to find my traditional roots again.” (Family member 2)

Fear

Fear, which is a common theme in cancer experiences, was embedded within Indigenous world view concepts for some participants (Box 4). Indigenous world view was reflected when cancer experiences of participants were perceived as useful for others who were experiencing fear. Another participant found hope and inspiration in their journey through sharing and keeping “spirits” strong. It was important for this participant to fight fear with hope.

Box 4: Fear and Indigenous world view.

“And I have recognized that those tears and that fear does not make me weak, it makes me human. And that struggle and that hurt is meant to be there because it’s going to help me help somebody else.” (Patient 6)

“Sharing hope and inspiration is one thing that I’ve found along the journey. Knowledge of any kind that we can share together, so a lot of it is just getting together sharing hope, inspiration, keeping our spirits strong.” (Patient 3)

Interpretation

This study explored concepts of trust and world view in decision-making with Indigenous patients undergoing cancer treatment. Participants reported experiences related to trust and mistrust of the medical system and several manifestations of Indigenous world view.14 Trust appeared to be connected to the participant’s confidence that the health care system had accepted the Indigenous world view. This perception of acceptance corresponded with trust in physician expertise. The result was the belief that Indigenous medicine would be protected. Other participants embraced both Indigenous and Western perspectives.

The relations between trust and world views were complex. Both Western and Indigenous medicine played a role when participants trusted that their use of Indigenous medicine was not at risk. As reported in other studies,12 spiritual beliefs, being strong for family and knowing Indigenous survivors were important to participants. This research supports other findings that Indigenous patients and families have distinct needs throughout cancer care26 and survivorship11,12,29 and amplifies the need for culturally safe practices among service providers.29

There is much yet to be learned about the complex connections between trust and world view and how they affect the decision-making of Indigenous patients with cancer. Further research could also involve Indigenous patients in identifying key solutions surrounding health care barriers in accessing cancer care.

Limitations

Possible bias could have been introduced by the research group asking a single patient partner to recruit participants and attend the circle. However, the research group was unlikely to make the necessary contacts without this patient partner and relied on their presence to engage participants in the circle. Indigenous people tend to mistrust researchers17,19,30 and might be unlikely to share intimate experiences such as cancer journeys. In this study, the researchers could gain trust because of the patient partner and their social contacts within Indigenous communities.

Although sharing circles offer a culturally relevant and potentially more appropriate method for Indigenous participants to share experiences, the protocol means limited influence over specific topics that participants discuss. Specifically, once the circle started, the researchers were unable to focus participants’ stories on the concepts of interest. Retrospectively, we could have asked the patient partner (the first person to speak) to highlight explicitly how trust and world view affected their decision-making regarding their cancer journey. This may have prompted other participants to share more exclusively about their experiences related to trust and world view. However, the nature of the flowing discussions and unpredictability in patient narratives is common in Indigenous methodologies, meaning the interpretation is often up to the listener.31 Our sharing circles protocol allowed us to access participants’ journeys in a nondirected way, bringing greater richness to the data. In that way, the protocol was both a limitation and a strength.

In verifying our analysis with a second Indigenous patient partner, we endeavoured to stay true to a patient understanding of the data. We also recognize that including the perspectives of only these 2 patient partners may have directed our findings in a particular manner that participation of a different patient partner may not have; our budget prohibited the participation of additional patient partners. With more resources, we could have involved the first patient partner in data analysis, and had member-checking and knowledge dissemination during each phase of analysis. For a full patient-oriented research study, more involvement of participants throughout would have been ideal.

Lessons learned from patient involvement

Sharing circles offered a culturally safe environment for Indigenous patients to share their cancer journey experiences.17,20,21,30–32 The use of the sharing circles method in particular was made possible by the participant recruitment of the first patient partner, who was both a cancer survivor and an Indigenous community member. They also suggested the study setting and ensured the sharing circle protocols were followed for the gathering. Sharing circles cannot be conducted with Indigenous Peoples without following traditional protocols. A circle keeper who knows how to facilitate these circles properly is instrumental to this research methodology. Our patient partner’s familiarity with conducting the protocols allowed us to respect and follow these practices before, during and after the gathering.

When a second Indigenous patient partner reviewed our initial analysis and both confirmed and offered refined explanations, we recognized the value of having multiple patients in various stages of the project. As researchers, we gained valuable experience in participating with the sharing circles. Collaborating in this gathering helped strengthen our ties with Indigenous communities. We are confident that this could lead to further dialogue in how to optimize Indigenous access to and experiences with health care.

Conclusion

This study provides a deeper understanding of how trust and world view are apparent in the journeys of Indigenous patients with cancer. Trust in physician expertise and protection of Indigenous medicine was important, whereas some participants experienced mistrust with diagnosis and with treatment after recurrence. World view was connected to spiritual beliefs, being strong for family and knowing Indigenous survivors. Some participants held beliefs in both Western and Indigenous medicine. When practitioners respected Indigenous world view, patient trust seemed to increase.

This research supports that Indigenous patients and families have distinct needs throughout their cancer care. In addition, these findings amplify the need for culturally safe practices among service providers. This includes accepting the holistic elements of Indigenous culture such as ceremony, values and healing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are dedicated to ensuring that the spirit of Reconciliation and Treaty 6 is honoured and respected. This acknowledgement also reaffirms that the research was conducted on Treaty 6 Territory and homeland of the Métis. Special thanks to Terri Hansen Gardiner, the second patient partner, for their input on the authors’ analysis and to Gilbert Kewistep, the Elder, for their assistance.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Tracey Carr, Lorna Arcand, Rose Roberts and Gary Groot contributed to the conception and design of the work and the acquisition of data. Tracey Carr, Jennifer Sedgewick and Anum Ali made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation for the work. All authors were involved in drafting and revising the manuscript and gave approval of the final version. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Data sharing: Participants did not give consent for this level of disclosure of their cancer journeys. Without this consent, the researchers are not able to provide access to any portion of the data. Therefore, no portion of the data is available to others.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/8/4/E852/suppl/DC1

References

- 1.Elias B, Kliewer EV, Hall M, et al. The burden of cancer risk in Canada’s Indigenous population: a comparative study of known risks in a Canadian region. Int J Gen Med. 2011;4:699–709. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S24292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marrett LD, Jones CR, Wishart K. First Nations cancer research and surveillance priorities for Canada. workshop report; September 23–24, 2003; Ottawa, Ontario. Toronto: Cancer Care Ontario; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Métis Nation of Ontario and Cancer Care Ontario. Cancer in the Métis people of Ontario: risk factors and screening behaviours. Toronto: Cancer Care Ontario; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazereeuw MV, Withrow DR, Nishri ED, et al. Cancer incidence among First Nations adults in Canada: follow-up of the 1991 census mortality cohort (1992–2009) Can J Public Health. 2018;109:700–9. doi: 10.17269/s41997-018-0091-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGahan CE, Linn K, Guno P, et al. Cancer in First Nations people living in British Columbia, Canada: an analysis of incidence and survival from 1993 to 2010. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;28:1105–16. doi: 10.1007/s10552-017-0950-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheppard AJ, Chiarelli AM, Marrett LD, et al. Detection of later stage breast cancer in First Nations women in Ontario, Canada. Can J Public Health. 2010;101:101–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03405573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Withrow DR, Pole JD, Nishri ED, et al. Cancer survival disparities between First Nation and non-Aboriginal adults in Canada: follow-up of the 1991 census mortality cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26:145–51. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.“It’s our responsibility … ”: report of the Aboriginal Cancer Care Needs Assessment. Toronto: Aboriginal Cancer Care Unit, Cancer Care Ontario; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMichael C, Kirk M, Manderson L, et al. Indigenous women’s perceptions of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment in Queensland. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2000;24:515–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2000.tb00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newman CE, Gray R, Brener L, et al. “I had a little bit of a bloke meltdown … but the next day, I was up”: understanding cancer experiences among Aboriginal men. Cancer Nurs. 2017;40:E1–8. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gifford W, Thomas R, Barton G, et al. Providing culturally safe cancer survivorship care with Indigenous communities: study protocol for an integrated knowledge translation study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019;5:331. doi: 10.1186/s40814-019-0422-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gifford W, Thomas O, Thomas R, et al. Spirituality in cancer survivorship with First Nations people in Canada. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27:2969–76. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4609-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demers AA. Mammography rates for breast cancer screening: a comparison of first nations women and all other women living in Manitoba, Canada, 1999–2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E82. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.140571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groot G, Waldron T, Barreno L, et al. Trust and world view in shared decision making with indigenous patients: a realist synthesis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26:503–14. doi: 10.1111/jep.13307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasakamoose J, Bellegarde T, Sutherland W, et al. Miýo-pimatisiwin developing Indigenous cultural responsiveness theory (ICRT): improving indigenous health and well-being. Int Indig Policy J. 2017 Oct 1;:8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carr T, Sedgewick JR, Roberts R, et al. The sharing circle method: understanding Indigenous cancer stories. SAGE Research Methods Cases. 2020 doi: 10.4135/9781529711264.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tachine AR, Bird EY, Cabrera NL. Sharing circles: an Indigenous methodological approach for researching with groups of Indigenous Peoples. Int Rev Qual Res. 2016;9:277–95. [Google Scholar]

- 18.The land. Saskatoon: Wanuskewin Heritage Park; 2019. [accessed 2019 Nov 7]. Available: https://wanuskewin.com/our-story/the-land. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kovach M. Research as resistance: revisiting critical, Indigenous and anti-oppressive approaches. In: Strega S, Brown L, editors. Emerging from the margins: Indigenous methodologies. 2nd ed. Toronto: Canadian Scholar’s Press and Women’s Press Toronto; 2010. pp. 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hart MA. Sharing Circles: utilizing traditional practice methods for teaching, helping and supporting. In: O’Meara S, West DA, editors. From our eyes: learning from Indigenous Peoples. Toronto: Garamond Press; 1996. pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavallée LF. Practical application of an Indigenous research framework and two qualitative Indigenous research methods: sharing circles and Anishnaabe symbol-based reflection. Int J Qual Methods. 2009;8:21–40. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elders. Saskatoon: Saskatchewan Indigenous Cultural Centre; [accessed 2020 Aug. 25]. Available: https://sicc.sk.ca/elders/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carr T. Resolution Health Support Program Evaluation. Melfort (SK): Canadian Métis Heritage Corporation; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butina M. A narrative approach to qualitative inquiry. Clin Lab Sci. 2015;28:190–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jull J, Giles A, Boyer Y, et al. Shared decision-making with Aboriginal women facing health decisions: a qualitative study identifying needs, supports, and barriers. AlterNative. Int J Indig Peoples. 2015;11:401–16. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hillen MA, de Haes HC, Smets EM. Cancer patients’ trust in their physician — a review. Psychooncology. 2011;20:227–41. doi: 10.1002/pon.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaiser K, Rauscher GH, Jacobs EA, et al. The import of trust in regular providers to trust in cancer physicians among white, African American, and Hispanic breast cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:51–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1489-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52:1893–907. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gifford W, Thomas R, Barton G, et al. “Breaking the silence” to improve cancer survivorship care for First Nations Peoples: a study protocol for an Indigenous knowledge translation strategy. Int J Qual Methods. 2018;17:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurtz DLM. Indigenous methodologies: traversing Indigenous and Western worldviews in research. AlterNative. Int J Indig Peoples. 2013;9:217–29. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poudrier J, Thomas R. We’ve fallen into the cracks”: a photovoice project with Aboriginal breast cancer survivors. Nurs Inq. 2009;16:306–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2008.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothe JP, Ozegovic D, Carroll LJ. Innovation in qualitative interviews: “Sharing circles” in a First Nations community. Inj Prev. 2009;15:334–40. doi: 10.1136/ip.2008.021261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.