Abstract

Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are ubiquitously present in the environment, but NTM diseases occur infrequently. NTM are generally considered to be less virulent than Mycobacterium tuberculosis, however, these organisms can cause diseases in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent hosts. As compared to tuberculosis, person-to-person transmission does not occur except with M. abscessus NTM species among cystic fibrosis patients. Lung is the most commonly involved organ, and the NTM-pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) occurs frequently in patients with pre-existing lung disease. NTM may also present as localized disease involving extrapulmonary sites such as lymph nodes, skin and soft tissues and rarely bones. Disseminated NTM disease is rare and occurs in individuals with congenital or acquired immune defects such as HIV/AIDS. Rapid molecular tests are now available for confirmation of NTM diagnosis at species and subspecies level. Drug susceptibility testing (DST) is not routinely done except in non-responsive disease due to slowly growing mycobacteria (M. avium complex, M. kansasii) or infection due to rapidly growing mycobacteria, especially M. abscessus. While the decision to treat the patients with NTM-PD is made carefully, the treatment is given for 12 months after sputum culture conversion. Additional measures include pulmonary rehabilitation and correction of malnutrition. Treatment response in NTM-PD is variable and depends on isolated NTM species and severity of the underlying PD. Surgery is reserved for patients with localized disease with good pulmonary functions. Future research should focus on the development and validation of non-culture-based rapid diagnostic tests for early diagnosis and discovery of newer drugs with greater efficacy and lesser toxicity than the available ones.

Keywords: Diagnosis, non-tuberculous mycobacteria pulmonary disease, NTM, NTM extrapulmonary disease, treatment

Introduction

Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are known by several names including environmental mycobacteria, atypical mycobacteria or anonymous mycobacteria, mycobacteria other than Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) (MOTT) and its close relatives, M. africanum, M. bovis, M. canetti, M. caprae, M. pinnipedii and M. leprae1. These organisms are ubiquitous in the environment and have been isolated from air, soil, dust, plants, natural and drinking water sources including biofilms, wild animals, milk and food products2,3. NTM are characterized by a thin peptidoglycan layer surrounded by a thick outer lipid-rich coating that enables NTM attachment to rough surfaces and by offering resistance to antibiotics and disinfectants, helping NTM survival in low oxygen and carbon concentrations and in other adverse conditions4. Based on their growth characteristics from the subculture, NTM are divided into rapidly growing mycobacteria (RGM; <7 days) and slowly growing mycobacteria (SGM; ≥7 days)5 (Table I). At present, there is no evidence for the latency of NTM6. Taxonomy of the genus Mycobacterium includes about 200 species and 13 subspecies7,8,9.

Table I.

Common non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) species causing human diseases

| Slowly growing NTM (showing growth in ≥7 days on subculture) |

| 1. Photochromogens (produce pigment on exposure to light) Mycobacterium kansasii |

| M. marinum |

| 2. Scotochromogens (produce pigment when grown in dark) |

| M. scrofulaceum |

| 3. Non-chromogens (growth not pigmented) |

| M. avium complex (MAC) |

| M. avium |

| M. intracellulare |

| M. chimaera |

| M. ulcerans |

| M. xenopi |

| M. simiae |

| M. malmoense |

| M. szulgai |

| M. haemophilum |

| Rapidly growing NTM (showing growth in <7 days on subculture) |

| M. abscessus |

| M. abscessus subspecies abscessus |

| M. abscessus subspecies bolletii |

| M. abscessus subspecies massiliense |

| M. fortuitum |

| M. chelonae |

Source: Ref. 5

In high tuberculosis (TB)-burden countries, diagnosis of NTM is rarely made because of lack of awareness among healthcare providers about the NTM diseases and poor access to adequate laboratory resources including mycobacterial culture and molecular methods for identification or speciation10. In these resource-limited settings, there is a heavy reliance on smear microscopy for the diagnosis of TB, and the diagnosis of NTM is frequently missed and these patients are empirically treated as drug-sensitive and -resistant TB11.

Epidemiology

NTM disease burden

Table II describes the distribution of various NTM species in the environment2,3. Table III details the major differences between NTM and Mtb1,2,3,4,5,6,9,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. Although recent reports regarding the transmission of M. abscessus and M. massiliense have not proven person-to-person transmission, but these are highly suggestive of indirect transmission among cystic fibrosis (CF) patients21. Systematic reporting of NTM diagnosis is not done because the disease is not notifiable to public health authorities in several countries10. NTM lung infection rates, defined as individuals with NTM-positive cultures and those with defined NTM pulmonary disease (NTM-PD), increase with age22 and differ considerably among various countries23,24,25. Many studies have suggested an increase in the prevalence rates of NTM over the last four decades22,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. The data from the USA suggest that the current prevalence of NTM-positive culture ranges between 1.4 and 6.6/100,000 individuals26, whereas UK data suggest that NTM-positive culture incidence has increased from 4/100,000 to 6.1/100,000 individuals between 2007 and 201235. A study from Canada has reported a significant increase in the prevalence of NTM-PD from 29.3 cases/100,000 in 1998-2002 to 41.3/100,000 individuals tested in 2006-201036. Several factors that have contributed to this increase in the incidence and prevalence are listed in Box I37,38. Published reports on rate of NTM isolation from several countries are summarized in Table IV22,29,30,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63.

Table II.

Environmental niches of non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM)

| Types of sources | Sources | Commonly isolated NTM |

|---|---|---|

| Natural water sources | Streams, rivers, lakes, ponds and seawater | MAC, Mycobacterium fortuitum, M. chelonae, M. kansasii, M. gordonae, M. xenopi, M. marinum |

| Man-made water sources | Drinking water supply pipelines | MAC, M. kansasii, M. gordonae, M. xenopi, M. abscessus, M. fortuitum, M. chelonae, M. scrofulaceum, M. szulgai |

| Cold and hot water tanks | ||

| Hot tubs, indoor and outdoor pools | ||

| Household plumbing, showerheads and faucets | ||

| Hospital plumbing and water supply | ||

| Ice machines and commercial ice | ||

| Bottled drinking water | ||

| Aerosols | Showers, hot-tubs, humidifiers, indoor swimming pools, heater-cooler units in hospitals | MAC, M. kansasii, M. gordonae, M. abscessus |

| Other sources* | Natural soil dust, potting soil, peat moss and domestic dust | MAC, M. fortuitum, M. chelonae, M. kansasii |

Table III.

Differences between non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb)

| Characteristics | NTM | Mtb |

|---|---|---|

| Nomenclature | NTM have several names: MOTT, atypical mycobacteria, anonymous mycobacteria and environmental mycobacteria. The preferred name is NTM. | Mtb is an important member of MTBC responsible for human TB. Other members include M. africanum, M. bovis, M. canettii, M. caprae and M. pinnipedii. |

| NTM species distribution | Nearly 200 species are described using DNA sequencing (a new species is defined as >1% difference in nucleotides); NTM species have regional variation due to climatic and geographical factors. | Mtb strains [Beijing (most pathogenic), Cameroon, CAS, EAI, Haarlem, LAM, Manu (Indian), and S] have geographical variation. |

| Biochemical tests | No single biochemical test is available for the diagnosis of NTM species. Some of the NTM species show positive results with niacin accumulation test (M. simiae, M. chelonae), nitrate reduction test (M. ulcerans, M. szulgai, M. fortuitum, M. smegmatis, M. kansasii), catalase test (M. fortuitum, M. chelonae, M. abscessus, M. ulcerans, M. szulgai, M. kansasii), citrate utilization test (M. chelonae, M. smegmatis), urea hydrolysis test (M. kansasii, M. marinum, M. simiae, M. szulgai, M. scrofulaceum), McConkey agar (without crystal violet) (M. fortuitum, M. abscessus) test and tellurite reduction (M. avium, M. intracellulare, M. simiae, M. fortuitum, M. abscessus). | Mtb is niacin positive, reduces nitrate and is negative for heat-stable catalase test. |

| Microscopic morphology | Absence of characteristics serpentine cords in acid-fast smears. | Characteristic serpentine cording seen as rope-like aggregates in which long axis of the bacilli is parallel to the long axis of the cord in acid-fast smears. |

| Growth characteristics in cultures | Rapidly growing (<7 days) and slowly growing (≥7 days) mycobacteria, growth rates are slower than other bacteria (Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli). | Mtb are slowly growing mycobacteria and take ~2 wk to grow. Ordinary bacteria may take ~20 min to 12-24 h in the laboratory. Mtb colonies are rough, cauliflower-like and light buff in colour. |

| Differential identification | Difficult to differentiate NTM from Mtb only on the basis of positive acid-fast smear. Culture is important in differentiating from P. aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Nocardia, Aspergillus and Sporothrix, etc. | Both smear and culture should be done. |

| Transmission | Person-to-person transmission does not occur except for M. abscessus among cystic fibrosis patients. | Mtb is highly transmissible through airborne route especially in PTB with cavitary disease and high bacillary loads. |

| Route of entry | Infection occurs mainly by inhalation, ingestion or direct inoculation. Airborne NTM are a major source of entry for NTM-PD. In advanced HIV/AIDS, gut colonization with subsequent haematogenous dissemination occurs. | Smaller cough droplet nuclei (<1-10 µM) carrying Mtb reach terminal bronchioles and alveoli and establish infection. |

| Pathogenicity potential | Opportunistic organisms | Highly pathogenic and obligate parasites |

| Virulence | Generally, NTM have low virulence. | Highly virulent |

| M. kansasii is more virulent among NTM. | ||

| Latent infection | No evidence of latent NTM infection | Systematic data are available regarding LTBI especially in low TB-burden countries. |

| Efforts should be made to differentiate between LTBI and active disease in high TB burden settings. | ||

| Case notification | It is not essential to notify laboratory confirmed, newly diagnosed NTM cases. NTM disease notification is practiced only in a few countries. | Systematic TB notification is encouraged and the global TB report is published annually on a regular basis by the World Health Organization. |

| Pulmonary: extrapulmonary disease proportions | Pulmonary: Extrapulmonary 80-90%: 10-20% in HIV-negative. Disseminated NTM disease occurs in severely immunocompromised individuals such as advanced HIV/AIDS. | Pulmonary 80-85%: extrapulmonary 15-20% in HIV-negative and pulmonary 40-50%: extrapulmonary 50-60% in HIV/AIDS. |

| Risk factors | NTM-PD usually occurs in individuals with pre-existing lung disease or in those with quantitatively impaired mucociliary function or in individuals who are heterozygous for CFTR mutations. | TB can involve both healthy and destroyed lungs. Risk factors include: malnutrition, tobacco smoking, chronic alcohol intake, diabetes mellitus, overcrowding, HIV/AIDS, head or neck cancer, leukaemia, or Hodgkin’s disease, drugs including corticosteroids, TNF-α inhibitors or receptor blocker. |

| Lady Windermere syndrome occurs in post-menopausal non-smoking females with nodular-bronchiectasis, several skeletal abnormalities, increased adiponectin and decreased leptin and oestrogen levels, abnormalities in fibrillin gene, high prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease and increased susceptibility to NTM infections. | ||

| NTM species predilection for various organs | Pulmonary: MAC, M. kansasii, M. xenopi, M. malmoense, M. abscessus, M. fortuitum M. simiae | No such predilection for body organs is known in TB. |

| Skin: M. ulcerans, M. marinum, M. abscessus, M. chelonae, M. fortuitum | ||

| Soft tissues: M. chelonae and M. fortuitum | ||

| Lymphadenitis: MAC but can occur with other NTM species also. | ||

| Disseminated NTM disease: Most commonly due to MAC but other species can also produce disseminated disease. | ||

| Radiographic patterns in MAC-pulmonary disease | Three types of radiographic patterns occur in MAC NTM-PD: | PTB Primary complex (usually in children) |

| Cavitary: In elderly smokers with COPD patients. | Progressive pulmonary disease | |

| NB: Predominantly in post-menopausal non-smoking females; bilateral bronchiectasis, multiple nodules and tree-in-bud appearance on HRCT, some may also have small cavitary lesions. | Post-primary PTB: Cavitary, atelectasis, consolidation Miliary PTB | |

| Hypersensitivity pneumonitis-like NTM pulmonary disease due to MAC and M. immunogenum. | Sequelae such as fibrotic and calcified lesions | |

| Clinical relevance of NTM isolates in respiratory specimens | Clinical relevance of isolated NTM species versus activity of the underlying pulmonary disease should be assessed. Colonization in the host and contamination in the laboratory must be ruled out. Causality association of the particular isolated NTM species with the pulmonary disease should be carefully established before starting the treatment. | Mtb produces both latent TB infection and active disease. Active TB disease must be ruled out appropriately before starting the treatment. |

| Drug susceptibility testing (DST) | DST for NTM is controversial because of poor correlation between in vitro DST pattern and in vivo treatment response and outcomes. According to CLSI (2018) guidelines16, initial and recurrent MAC and M. kansasii be tested for DST. | Universal DST should be performed and treatment should be carried out as per sensitivity profile of Mtb. DS-TB, H monoresistance, MDR-TB and XDR-TB should be treated with as per National Guidelines, and tolerance of drugs. |

| Both phenotypic and genotypic DST are performed. | ||

| For MAC, perform DST against macrolides (clarithromycin as a class agent) and amikacin; for M. kansasii, against rifampicin and clarithromycin. | ||

| RGM species (and subspecies) show different drug resistance patterns and DST should be selectively tested for various antibiotics (macrolides, amikacin, tobramycin, imipenem, trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole, doxycycline, minocylcine, tigecyline, cefoxitin linezolid) DST, erm (41) gene status should be done in M. abscessus. | ||

| Information about erm (41) gene and phenotypic DST for clarithromycin should be done on days 3-5 and 14 in case of M. abscessus. | ||

| Treatment | ATS (2007)17 and BTS (2017)1 ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA18 guidelines on NTM diseases should be followed. | National guidelines should be followed for treatment of drug sensitive and drug-resistant TB. |

| Treatment outcomes | Treatment outcomes differ among NTM species and subspecies. | Globally, treatment outcomes in case of drug-sensitive TB are good. Treatment of drug-resistant TB is still a challenge and global rate of successful treatment is 56% only. With newer drug regimen(s), treatment success rates are likely to improve in future. |

| Prevention | Exposure to NTM from the environmental sources especially household water systems, hospital settings and soil should be avoided. In HIV/AIDS patients (CD4 T-cells counts <50/μl), antimicrobial prophylaxis includes administration of azithromycin (1200 mg/weekly) or clarithromycin (500 mg twice daily) or rifabutin (300 mg/day) along with antiretroviral drugs till CD4 cell count is >100 cells/μl for three months. | Exposure to smear positive PTB should be avoided to halt TB transmission. Chemoprophylaxis for latent TB infection (active TB disease must be ruled out in high TB-burden countries), various treatment options include: isoniazid daily for 6 or 9 months, or combination of rifapentine and isoniazid once weekly for 12 wk or combination of rifampicin and isoniazid daily for 3-4 months or rifampicin alone daily for four months. |

| Vaccines | No vaccine is available at present | BCG vaccine is recommended in high TB burden countries to prevent severe form of TB (miliary and central nervous system TB); newer TB vaccines such as M72/AS01, M. vaccae, MVA85A etc., are in clinical trials. M72/AS01 was significantly protective against TB disease in a Phase IIb trial in Kenya20. |

Disseminated disease: Involvement of two or more non-contiguous body sites through haematogenous route. Note: Underlying oesophageal disease must be ruled out in NTM-PD due to RGM especially M. fortuitum. NTM-PD, NTM-pulmonary disease; MTBC, Mtb complex; CAS, Central Asian strain; EAI, East African Indian strain; LAM, Latin American-Mediterranean strain; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SGM, slowly growing mycobacteria; RGM, rapidly growing mycobacteria; CLSI, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; ATS, American Thoracic Society; BTS, British Thoracic Society; ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA, American Thoracic Sciety European Respiratory Society European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Infectious Diseases Society of America; erm, erythromycin ribosome methylation; MOTT, mycobacteria other than TB; LTBI, latent TB infection; CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; MAC, Mycobacterium avium complex; NB, nodular/bronchiectatic; HRCT, high-resolution computed tomography; MDR, multidrug resistant; XDR, extensively drug resistant; PTB, pulmonary TB; BCG, bacille Calmette-Guerin. Source: Refs 1,2,3,4,5,6,9,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20

Box I.

Factors contributing to increased non-tuberculous mycobacteria burden

| 1. Genetic evolution in NTM due to mutations leading to increased virulence |

| 2. Environmental and climatic changes due to increased human-manufactured infrastructure |

| 3. Changes in host immunity due to increased life expectancy and immunocompromised population |

| 4. Increased incidence of chronic lung disease |

| 5. Decreasing herd immunity due to declining TB burden especially in high-income countries |

| 6. Widespread availability of CT scanning and laboratory infrastructure for NTM diagnosis |

| 7. Increasing awareness among medical personnel about NTM disease |

| 8. Sharp rise in NTM publications by laboratories and practicing physicians |

CT, computed tomography; NTM, non-tuberculous mycobacteria. Source: Ref. 38

Table IV.

Global prevalence of pulmonary non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) isolation and NTM disease

| Zone | Countries | NTM isolation prevalence per 100,000 individuals | NTM disease prevalence per 100,000 individuals | Commonly isolated NTM species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | Canada36 | 22.2 | 9.08 | MAC, Mycobacterium xenopi, |

| USA | M. abscessus, M. fortuitum, | |||

| Oregon39 | 12.7 | 8.6 | M. chelonae, M. gordonae | |

| California39 | 191 | NR | MAC, M. kansasii, M. abscessus, | |

| Hawaii22 | 396 | NR | M. xenopi, M. fortuitum | |

| South America | Brazil40 | 1.31 | 0.25 | MAC, M. kansasii, M. abscessus, M. xenopi, M. fortuitum |

| Europe | Ireland41 | 1.9 | 0.2 | MAC, M. kansasii, M. xenopi, |

| Scotland42 | NR | 3.1 | M. malmoense, M. marinum, | |

| The United Kingdom43 | 2.9 | 1.7 | M. szulgai, M. gordonae, | |

| Denmark34 | 2.5 | 1.1 | M. abscessus, M. chelonae | |

| Netherlands44 | 6.3 | 1.4 | ||

| France45 | NR | 0.7 | ||

| Greece46 | 07 | 0.7 | ||

| Croatia47 | 5.3 | 0.75 | ||

| Oceania | Australia48 | 5.9 | 0.56 | MAC, M. kansasii, M. abscessus, |

| New Zealand49 | 3.7 | 0.56 | M. fortuitum, M. simiae | |

| Africa | Kenya50* | 1.7% | NR | MAC, M. abscessus, |

| Nigeria51* | 4.3% | NR | M. malmoense, M. marinum, | |

| Uganda52* | 4.3% | NR | M. xenopi, M. scrofulaceum, | |

| Burkina Faso53* | 20.6% | NR | M. simiae, M. gordonae | |

| Asia | Japan29 | 33-65 | NR | MAC, M. abscessus, M. fortuitum, |

| South Korea54 | 39.6 | NR | M. simiae, M. szulgai, M. chelonae, M. gordonae | |

| China55* | 6.3% | NR | ||

| Taiwan30 | 7.94 | NR | ||

| Singapore56* | 511 | NR | ||

| Iran57,58* | 0.7 to 8% | NR | ||

| India59,60,61,62,63* | 0.2 to 5.9% | 0.8% |

*Data presented in % is the isolation of NTM among TB suspected individuals in high TB burden countries Note: NTM isolation data for India provided from Refs 59-63 and disease prevalence from Ref. 61 NR, not reported; MAC, Mycobacterium avium complex

Details of 13 Indian studies published between 1985 and 2019 are summarized in Table V59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71. Most of these studies have reported NTM isolation rates from laboratories without describing clinical features and treatment details. Two studies were done exclusively on extrapulmonary specimens and 11 on both pulmonary and extrapulmonary specimens. NTM isolation prevalence varied between 0.38 and 23.7 per cent. Six of these 13 studies reported NTM prevalence ≤1 per cent among TB suspects. Almost all except one study have not provided treatment outcomes. Most of the studies (11/13) were hospital based and had selection bias. A large community-based study from south India conducted at four sites in the pre-HIV era has reported NTM isolation prevalence between 4.5 and 8.6 per cent in the sputum specimens. This variable NTM prevalence can be attributed to the following factors: (i) differences in study designs, (ii) standard American Thoracic Society (ATS) (2007)17 and British Thoracic Society (BTS) (2017)1 guidelines criteria were not followed in most of these studies, (iii) only laboratory-related NTM culture data have been reported, and (iv) most of the studies have not provided clinical details and treatment outcomes. Of the 13 studies, only two61,71 followed ATS guidelines (2007)17 and one of these reported treatment outcomes61. Future studies should report about extrapulmonary NTM diseases in addition to clinical details including treatment outcomes of various NTM diseases.

Table V.

Summary of Indian studies on non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM)

| Study details | Methods of NTM detection and identification and results | Identified NTM species | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| North zone | |||

| Myneedu et al59, New Delhi Hospital-based prospective study (2009-2011) Total TB suspects=15,581 PTB=12,466 EPTB=3,115 HIV status: Not available |

ZN staining Liquid culture (MGIT 960) Biochemical tests Prevalence: 0.38% (60/15581) in TB suspects Other results: Pulmonary NTM: 45% (27/60) Extrapulmonary NTM: 55% (33/60) |

21 NTM species were identified, % (n) Mycobacterium simiae 11.3 (7) M.avium 9.7 (6) M. gordonae 8.1 (5) M. kansasii 8.1 (5) M. fortuitum 8.1 (5) Others: M. chelonae 8.1 (5), M. phlei 8.1 (5), M. terrae 6.4 (4), M. szulgai 3.2 (2), M. vaccae 3.2 (2), M. flavescens 3.2 (2), M. trivale 3.2 (2), M. malmoense, M. scrofulaceum, M. intracellulare, M. xenopi, M. ulcerans, M. tusciae, M. triplex, M. septicum, M. mucogenicum each 1.6 (1) |

Clinical relevance of isolated NTM is not established. HIV status of patients not provided. Molecular methods such as PCR and gene sequencing not performed for NTM species identification. Treatment details including outcomes not provided. |

| Jain et al60, New Delhi Hospital-based retrospective study (2011-2012) Total TB suspects=436 PTB=237 EPTB=199 HIV status: All negative |

ZN staining Liquid culture (MGIT 960) PNB-LJ culture ICA (SD MPT64TB Ag Kit) Multiplex-PCR Prevalence: 2.98% (13/436) Other results: Pulmonary NTM: 69.2% (9/13) Extrapulmonary NTM: 30.8% (4/13) |

M. kansasii 30 (4) M. chelonae 23.1 (3) M. xenopi 15.4 (2) M. scrofulaceum 7.7 (1) M. avium 7.7 (1) M. asiaticum 7.7 (1) M. fortuitum 7.7 (1) |

Retrospective study on culture isolates. Clinical relevance of isolated NTM not determined. Gene sequencing not used for speciation. Treatment details including outcomes not provided. |

| Maurya et al64, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh Hospital-based prospective study (2015) EPTB suspects only=756 HIV status: Not available |

ZN staining Liquid culture (BacT/ALERT 3D) ICA (SD MPT64 TB Ag Kit) Biochemical tests LPA (CM/AS Kit) Prevalence: 8.2% (62/756) in EPTB suspects |

M. fortuitum 27.5 (17) M. intracellulare 20.9 (13) M. abscessus 14.6 (9) M. chelonae 12.9 (8) Others: MAC 8.1 (5), M. kansasii 4.8 (3), M. gordonae 3.2 (2), M. interjectum 3.2 (2) and other species 4.8 (3) |

Biased selection of population (EPTB suspects). Molecular techniques such as gene amplification and gene sequencing not used for NTM speciation. Treatment details including outcomes not provided. |

| Umrao et al65, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh Hospital-based prospective study (2013-2015) TB suspects=4,620 HIV status: Available |

ZN staining Liquid culture (BacT/ALERT 3D) ICA (SD MPT64TB Ag Kit) Biochemical tests LPA (CM/AS Kit) Prevalence: 4.52% (263/4620) in TB suspects Pulmonary NTM: 79.1% (208/263) Extrapulmonary NTM: 20.9% (55/263) Other results: Three NTM patients were HIV positive |

M. abscessus 31.3 (82) M. fortuitum 22 (59) M. intracellulare 13.6 (36) M. chelonae 9.1 (24) M. avium 7.2 (19) M. interjectum 3.4 (9) M. simiae 3.4 (9) Others: M. gordonae 2.6 (7), M. scrofulaceum 1.9 (5), M. kansasii 1.9 (5), M. szulgai 1.7 (4), M. malmoense 0.7 (2), M. intermedium 0.7 (2) |

Gene sequencing not performed for NTM speciation. HIV status of the patients not provided. Clinical data of the patients not available. Treatment details including outcomes not provided. |

| Sairam et al66, New Delhi Hospital-based retrospective study (2015-2017) Total TB suspects=877 HIV status: Not available |

ZN staining GeneXpert MTB/RIF Culture Prevalence: 3.87% (34/877) in TB suspects Pulmonary NTM: 56% (19/877) Extrapulmonary NTM: 34% (15/877) |

M. intracellulare 23.5 (8) M. kansasii 20.5 (7) M. abscessus 14.7 (5) M. fortuitum 2.9 (1) M. chelonae 2.9 (1) M. interjectum 2.9 (1) Other include 11 isolates |

Details of methods of species identification not mentioned. HIV status of patients not provided. Data related to patients having actual disease not clear. Methods of NTM identification and speciation not clearly provided. Treatment details including outcomes not provided. |

| Sharma et al61, New Delhi Hospital-based prospective study (2014-2017) Total TB suspects=5,409 PTB=3,840 EPTB=1,569 HIV status: Available |

ZN and fluorochrome staining GeneXpert MTB/RIF Liquid culture (MGIT 960) ICA (SD MPT64TB Ag Kit) PNB-LJ culture LPA (CM/AS Kit) Mycolic acid analysis by HPLC 16S-23S rRNA ITS gene sequencing Prevalence: 0.7%(42/5409) Other results: Pulmonary NTM: 34 (81%) Extrapulmonary NTM: 8 (19%) M. simiae was repeatedly isolated in one patient with bronchial asthma, he was not treated because of absence of symptoms. One extrapulmonary NTM patient was HIV positive. |

Pulmonary NTM M. intracellulare 32.3 (11) M. abscessus 26.5 (9) M. simiae 14.7 (5) M. kansasii 11.8 (4) M. gordonae 8.8 (3) M. chimaera 2.9 (1) M. senegalense 2.9 (1) Extrapulmonary NTM M. abscessus 75 (6) M. intracellulare 12.5 (1) M. parascrofulaceum 12.5 (1) |

Multi-locus gene sequencing not performed to identify NTM to the subspecies level. |

| South zone | |||

| Paramasivan et al62, Thiruvallur, Tambaram, Madras city, Bangalore Community-based prospective study (1980-81) PTB suspects Thiruvallur: n=16,907 Tambaram: n=3,576 Madras city: n=24,121 Bangalore: n=12,909 HIV status: Pre-HIV era in India |

Solid culture (LJ medium) Biochemical tests Prevalence: 8.6% (1457/16,907): Thiruvallur 7.6% (270/3576): Tambaram 4.5% (1095/24,121): Madras city 4.5% (587/12,909): Bangalore |

Speciation for 1000 isolates from Thiruvallur was done M. avium/intracellulare 22.6 (226) M. terrae complex 12.5 (125) M. scrofulaceum 10.5 (105) M. fortuitum 7.6 (76) Others: M. flavescens 6.7 (67), M. gordonae 6.6 (66), M. chelonae 5.5 (55), M. vaccae 5.4 (54), M. phlei 3.4 (34), M. triviale 3.3 (33), M. smegmatis 1.9 (19), M. gastri 1.8 (18), M. asiaticum 1.5 (15), M. toakiense 1.1 (11), M. marinum 1 (10), M. malmoense 0.9 (9), M. kansasii 0.7 (7), M. szulgai 0.7 (7), M. haemophilum 0.6 (6), M. xenopi 0.5 (5), M. ulcerans 0.5 (5), M. aurum 0.5 (5), M. thermoresistable 0.2 (2), M. aichiense 0.2 (2), M. simiae 0.1 (1), M. thermophilum 0.1 (1), M. neoaurum 0.1 (1) |

Study done in pre-HIV era in India, therefore, it may not provide the true prevalence of NTM disease in the region. |

| Jesudason and Gladstone67, Vellore, Tamil Nadu Hospital-based prospective study (1999-2004) Total TB suspects=32,084 HIV status: Available |

ZN staining, Solid culture (LJ medium) Biochemical tests DST for rapidly growing NTM on Mueller-Hinton agar and for slow growing NTM on LJ medium was done Prevalence: 0.5% (173/32,084) among TB suspects Other results: Pulmonary NTM: 9.8% (17/173) Extrapulmonary NTM: 90.2% (156/173) 6 NTM patients were HIV positive |

Speciation was done only in 115 isolates M. chelonae 46 (53) M. fortuitum 41 (47) M. szulgai 2.6 (3) M. terrae 2.6 (3) Others: M. smegmatis 1.73 (2), M. scrofulaceum 0.9 (1), M. simiae 0.9 (1), M. flavescens 0.9 (1) and M. gordonae 0.9 (1) |

For NTM identification, newer molecular techniques such as gene probes, PCR and DNA sequencing not used. Clinical significance of isolated NTM not established. Data for pulmonary and extra-pulmonary NTM disease provided only for 115 patients. Treatment details including outcomes not provided. |

| Sivasankari et al68, Puducherry Hospital-based prospective study (2003-2004) Total TB suspects=635 PTB=337 EPTB=298 HIV status: Available |

ZN and fluorochrome staining Culture LJ medium Biochemical tests Prevalence: 0.8% (5/635) Other results: All patients had extrapulmonary NTM disease |

M. kansasii 60 (3) M. flavescens 20 (1) M. gordonae 20 (1) |

Molecular techniques such as HPLC, gene amplification and gene sequencing not used. Treatment details including outcomes not provided. |

| Radha Bai Prabhu et al69, Kancheepuram, Tamil Nadu Hospital-based prospective study (2008-2016) TB suspected tubal disease females=173 Only extrapulmonary specimens=urine, POD fluid and endometrial samples HIV status: Available |

ZN and fluorochrome staining Liquid culture (MGIT 960) Histopathological examination PCR Mycolic acid analysis by HPLC Prevalence: 23.7% (63/173) among tubal disease suspects Other results: 41 NTM isolates were associated with tubal disease |

M. chelonae 25.4 (16) M. fortuitum 6.3 (4) M. simiae 3.2 (2) M. kansasii 1.6 (1) M. intracellulare 1.6 (1) M. marinum 1.6 (1) |

Biased selection of population. Molecular methods for species identification not used Clinical relevance of isolated NTM species was not established. Treatment details including outcomes not provided. |

| West zone | |||

| Narang et al70, Wardha, Maharashtra Hospital-based prospective study (2001-2002) HIV-TB coinfection suspects=71 PTB=53 EPTB=14 (In 4 patients, information regarding pulmonary and extrapulmonary status was not available) HIV status: All positive |

Liquid culture (BACTEC 460TB) Biochemical tests Mycolic acid analysis by HPLC Prevalence: 8.4% (6/71) in HIV-TB suspected patients Other result Extrapulmonary NTM=6 |

MAC 50 (3) M. simiae 50 (3) |

Biased selection of the study population (HIV patients only). Molecular techniques not used for species identification. Clinical relevance of isolated NTM not discussed. Treatment details including outcomes not provided. |

| Shenai et al71, Mumbai, Maharashtra Hospital-based prospective study (2005-2008) Total TB suspects=14,627 HIV status: Available |

Liquid culture (MGIT 960) PNB-LJ culture NAP test (BACTEC 460 TB) RLBH assay of rpoB gene PCR-RE assay and gene sequencing Prevalence: 0.8% (127/14627) Other results: Pulmonary NTM: 81% (103/127) Extrapulmonary NTM: 19% (24/127) three NTM cases were HIV positive |

M. intracellulare 40 (32), M. simiae 35 (28), M. abscessus 59 (27), M. fortuitum 29 (19), M. kansasii 6 (5), M. gordonae 4 (3), M. szulgai 2 (2), M. avium 1 (1) Ten cases had mixed infection, 6 with Mtb and 4 had M. kansasii + M. fortuitum 1 (1), M. avium + M. kansasii 2 (2) and M. intracellulare + M. gordonae 1 (1) |

Sequencing of rpoB gene may lead to misidentification of NTM species. Multilocus gene sequencing would have given strength to the study. Treatment details including outcomes not provided. |

| Goswami et al63, Wardha, Maharashtra Community-based prospective survey (2007-2009) PTB suspects=6,445 HIV status: Not available |

Culture Biochemical tests DST by micro-broth dilution method Prevalence: 1% (65/6445) |

M. fortuitum 32.3 (21), M. gordonae 21.5 (14), M. avium 13.8 (9), M. flavescens 10.7 (7) Others: M. scrofulaceum 6.1 (4), M. chelonae 4.61 (3), M. abscessus 4.61 (3), M. kansasii 1.5 (1), M. simiae 1.5 (1), M. gastri 1.5 (1) and M. triviale 1.5 (1) |

Study was performed in PTB suspects only. How TB and NTM were distinguished not clear. HIV status of the patients not available. Gene sequencing for speciation not performed. Patients’ data not available. Treatment details including outcomes not provided. |

PTB, pulmonary TB; EPTB, extra PTB; LJ medium, Löwenstein-Jensen medium; ZN staining, Ziehl-Neelsen staining; DST, drug susceptibility testing; MGIT, mycobacteria growth indicator tube; PNB, p-nitrobenzoic acid; NAP, p-nitro-alpha-acetylamino-beta-hydroxypropiophenone; RLBH, reverse line blot hybridization; PCR-RE assay, polymerase chain reaction-restriction endonuclease assay; ICA, immunochromatographic assay; MPT64, mycobacterial protein 64 KD; LPA, line probe assay; 16S-23S rRNA ITS sequence, 16S-23S ribosomal RNA internal transcribed spacer sequence; MAC, Mycobacterium avium complex; POD, pouch of douglas; HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography

Risk factors for NTM disease

Risk factors for NTM diseases vary according to the clinical type of NTM disease72,73,74. Various risk factors for NTM-PD are described in Box IIA72,73,74. Pre-existent lung disease is mostly present in these patients. In the absence of obvious structural lung disease, patients may have quantitatively impaired ciliary function or may be heterozygous for cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene mutations75,76. Extrapulmonary NTM disease can occur due to breaches in skin or soft tissues or due to several nosocomial factors, which are detailed in (Box IIB)72,73,74. Disseminated NTM disease generally occurs in patients having primary or acquired immunodeficiency conditions. Certain environmental and organism-related factors such as water sources and reservoirs, and NTM growth characteristics in different climatic conditions, have also been reported as risk factors Box IIB72,73,74. In addition, habits, hobbies and profession of an individual may also increase the risk of having NTM disease74.

Box II.

(A and B): Risk factors for nontuberculous mycobacterial disease (A) Risk factors based on disease sites

| Pulmonary NTM disease | Extrapulmonary NTM disease (generally related to healthcare and commercial establishments) |

|---|---|

| Destroyed lungs due to TB or other diseases like pneumoconioses | Trauma (direct infection from environs) |

| Bronchiectasis (esp. middle lobe and lingula) due to any cause | Cosmetic surgeries |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Prosthetic devices and implants |

| Cystic fibrosis-CFTR gene polymorphism* | Organ transplantation |

| Primary ciliary dyskinesia | Dental procedures and surgeries |

| Alpha 1 antitrypsin deficiency | Intramuscular or intradermal injection |

| Lung cancer | Joint injections |

| Thoracic skeletal abnormalities (kyphoscoliosis) | Invasive devices (e.g., pacemakers) |

| Lady Windermere syndrome† | Medical tourism (individuals infected with NTM visiting to some other country) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease‡ | |

| Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis with lung involvement | |

| *NTM are isolated in sputum cultures of 3-19.5% of CF patients (majority are MAC). †High prevalence (26-44%) of NTM disease especially nodular-bronchiectatic type in nonsmoking postmenopausal white women who are taller and lean with scoliosis, pectus excavatum and mitral valve prolapse syndrome than their peers, ‡In gastroesophageal reflux disorders, RGM are commonly involved in the disease such as M. fortuitum. BMI: body mass index; CFTR: cystic fibrosis transmembrane receptor; MAC, Mycobacterium avium complex; CF, cystic fibrosis | |

| (B) Miscellaneous risk factors | |

| (i) Immunodeficiency states | |

| (a) Primary* | (b) Acquired |

| Anti-interferon γ-antibodies (blocking of interferon γ-interleukin-12 pathway) | HIV/AIDS status (CD4 counts <50 cells/µl) |

| Anti GM-CSF antibodies (impaired local immunity) | Use of biologics (anti-TNF agents and TNF receptor blockers) |

| NEMO mutations (impaired signal transduction from Toll-like receptors, interleukin-1, and TNFα) | Use of immunosuppressive agents and steroids |

| STAT1 deficiency (low systemic immunity) | |

| IL12 mutations (reduced T-cells and natural killer cells stimulation) | |

| CYBB mutations (decreased bactericidal activity) | |

| GATA2 gene mutations (impaired hematopoietic, lymphatic, and vascular development) | |

| (ii) Environmental factors | |

| (a) Household and lifestyle factors | (b) Climatic and bacterial population factors |

| Soil exposure | Larger water surface area |

| Showers and hot tubs | Higher mean daily potential evapotranspiration |

| Municipal water supply | Higher copper soil levels (helps mycobacteria to form biofilms) |

| Kitchen sink biofilms, ice machines, refrigerator taps | Higher sodium soil levels (more nutrition for mycobacteria) |

| Indoor swimming pool use in past 4 months | Lower manganese soil levels (manganese inhibits mycobacterial growth) |

| Outdoor swimming pool use for at least once a month | Lower top soil depth (high nutrition for mycobacteria due to low vegetation) |

| Infection from spa, Jacuzzi, whirlpool footbath, saunas, pedicure procedures | |

*These mutations are rare and associated with disseminated NTM disease. GM- CSF, granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor; NEMO, nuclear factor κB essential modulator; STAT1, Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (for disseminated infection); IL-12, interleukin-12; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; CYBB, cytochrome b-245 beta. Source: Refs 72,73,74

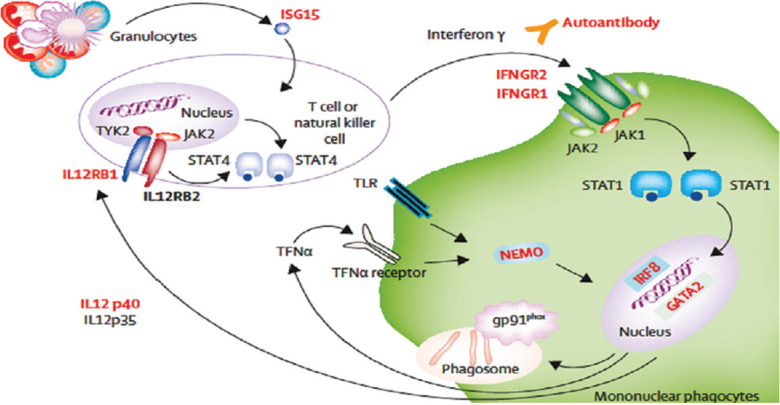

Immunopathogenesis of NTM disease

In addition to lung, the most common organ involved affected by NTM, localized and disseminated NTM infections can occur73. Patients with disseminated NTM infections (defined as involvement of two or more non-contiguous body organs) usually have underlying generalized immune defect such as HIV/AIDS, and 2-8 per cent of these patients may have concurrent pulmonary involvement77. Identification of the underlying immune defect is crucial for early diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Patients with NTM disease and underlying primary immunodeficiencies typically present in their childhood or adulthood, whereas those with acquired immunodeficiencies can present at any age (Table VI)73.

Table VI.

Primary and acquired immune deficiencies associated with disseminated non-tuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) infection

| Immunodeficiency | Inheritance | Disease onset | BCG infection | Systematic Salmonella infection | Other possible infection | Granuloma formation | Response to antimicrobial | Indication for immunotherapy | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early onset | |||||||||

| IFNGR1/R2 | |||||||||

| Complete | AR | Infancy/early childhood | Yes | Yes | Listeriosis, herpes virus, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus infections, TB | No | Very poor | No | Poor |

| Partial | AR | Late childhood | Yes | Yes | TB | No report | Favourable | Variable | Good |

| Partial | AR | Late childhood/adolescence | Yes | Yes | Histoplasmosis, TB | Yes | Favourable | Yes | Good |

| IL12B | AR | Infancy/early childhood | Yes (97%) | Yes (25%) | CMC, disseminated TB, nocardia, Klebsiella spp. infection | Yes | Favourable | Yes | Fair |

| IL12RB1 | AR | Early childhood | Yes (76%) | Yes (43%) | TB, CMC (24%), Klebsiella spp. infection | Yes | Favourable | Yes | Fair |

| STAT1 LOF | |||||||||

| Complete | AR | Infancy (die early without HSCT) | Yes | No | TB, fulminant viral infection (mainly herpes) | Yes | Poor | No | Poor |

| Partial | AR | Infancy/early childhood/adolescence | Yes | Yes (50%) | Severe, curable viral infection (mainly herpes) | No report | Favourable | Yes | Fair |

| Partial | AD | Infancy/early/childhood/adolescence | Yes | No | TB | Yes | Favourable | Yes | Good |

| IRF8 | AR | Infancy | Yes | No | CMC | Poorly formed | Poor | No | Poor |

| IRF8 | AD | Late infancy | Yes | No | No report | Yes | Favourable | No | Good |

| ISG15 | AR | Infancy | Yes | Yes | No report | No report | Favourable | Yes | Good |

| NEMO | XR | Early to late childhood | Yes | No | Invasive Hib infection TB | Yes | Variable | Yes | Fair |

| CYBB | XR | Infancy/early childhood | Yes | No | TB | Yes | Fair | No | Fair |

| Late onset | |||||||||

| GATA2 | AD | Late childhood/adulthood | No | No | HPV, CMV, EBV, Clostridium difficile infections, histoplasmosis, aspergillosis | Yes | Poor | Yes | Poor |

| Anti-IFN-γ antibodies | Acquired | Young adult to elderly | No | Yes | Salmonella spp., Penicillium spp., Histoplasma spp., Cryptococcus spp., B. pseudomallei, VZV, CMV infections | Yes | Poor | No | Fair |

AR, autosomal recessive; AD, autosomal dominant; CMC, chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis; LOF, loss of function; HSCT, haemopoietic stem cell transplantation; Hib, Haemophilis influenzae type b, HPV, human papillomavirus; CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; VZV, varicella zoster virus; BCG, bacille Calmette-Guerin; B. pseudomallei, Burkholderia pseudomallei; IFN-γ, interferon-gamma; XR, X-linked recessive; IFNGR, interferon-gamma recapter; IL, interleukin; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; IRF, interferon regulatory factor; ISG, interferon-stimulated genes; NEMO, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells essential modulator; GATA, transcription factor implicated in early hematopoietic, lymphatic and vascular development. Note: Investigations for GATA2 deficiency should be done in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and mycobacterial disease. Source: Reproduced with permission from Ref. 73

Antimycobacterial cell-mediated immunity requires a close interaction between myeloid and lymphoid cells (Fig. 1)73. Mononuclear phagocytes after engulfing mycobacteria secrete interleukin-12 (IL-12) which, in turn, stimulates T cells and NK (natural killer) cells through the IL-12 receptor (heterodimer of IL12RB1 and IL12RB2). A complex cascade is triggered by IL-12 receptors via TYK2 (tyrosine kinase) and JAK2 (Janus kinase) signals, leading to STAT-4 (signal transducer and activator of transcription) phosphorylation, homodimerization and nuclear translocation to induce interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) secretion (Fig. 1). IFN-γ binds to its receptor IFNG receptor (IFNGR) (heterodimer of IFNGR1 and IFNGR2) and leads to phosphorylation of JAK2, JAK1 and STAT1 and phosphorylated STAT1 (pSTAT1) homodimerisation. The pSTAT1 homodimer [IFN-γ activators (GAF)] binds to IFN-γ activation sequence which upregulates IFN-γ responsive gene transcription. This cascade leads to activation and differentiation of macrophages. As a result, upregulation of IL-12 and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) secretions facilitates granuloma formation. After these events, macrophages can kill intracellular mycobacteria being assisted by maturation of mycobacterial phagosome, nutrition deprivation and induction of autophagy, exposure to antimicrobial peptides and reactive oxygen species. The nuclear factor (NF) κB essential modulator-mediated pathway and oxidative burst from macrophages are also important to fight against NTM infection73. Genetic defects in any of these immune factors may disturb the cascade of protection against mycobacterial infection and may lead to disseminated NTM disease73. These immune defects have been summarized in Table VI73.

Fig. 1.

Host defence mechanisms against non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM). Defects leading to disseminated NTM infection are shown in red. ISG15, interferon-stimulated gene 15; IFNGR, interferon-gamma receptor; TYK, tyrosine kinase; JAK, Janus kinase; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; IRF, interferon regulatory factor; GATA, transcription factor implicated in early haemopoietic, lymphatic, and vascular development; NEMO, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells essential modulator; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; TLR, toll-like receptors. Source: Reproduced with permission from Ref. 73.

Clinical manifestations

The clinical manifestations of NTM disease are similar to those of TB and may pose a diagnostic challenge even to an experienced clinician. NTM disease is classified into four clinical types: (i) chronic PD, (ii) lymphadenopathy, (iii) skin and soft tissues, rarely, bones and joints, and (iv) disseminated disease73.

Chronic pulmonary disease (PD)

The ATS and Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), 200717, and BTS, 20171, ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA18 have published guidelines to standardize the diagnosis and treatment of NTM diseases. While evaluating NTM suspects, the following criteria should be followed: (i) pulmonary symptoms, nodular or cavitary opacities on chest radiograph, or high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scan that shows multifocal bronchiectasis with multiple, small nodules; (ii) positive culture results from at least two separate expectorated sputum samples [if the results from the initial sputum samples are non-diagnostic, consider repeat sputum acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smear and culture]; single-positive NTM culture from CT-directed bronchoalveolar lavage or bronchial washing specimen from the affected lung segment of NTM suspect who cannot expectorate sputum or whose sputum is consistently culture-negative; and (iii) other disorders such as TB and fungal infections must be excluded1,17.

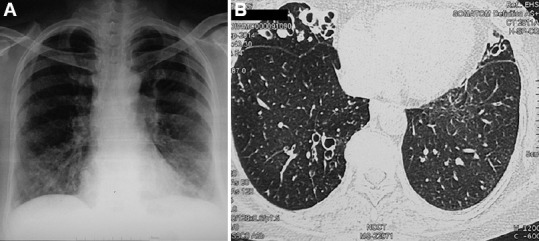

Patterns of NTM-PD: Chronic PD is the most common form of NTM disease. Three patterns of pulmonary involvement have been described17: (i) fibro-cavitary type, which usually occurs in the upper lobe with a history of smoking in an older male patient with pre-existent lung disease such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bronchiectasis and CF (Fig. 2); (ii) nodular/bronchiectatic type of pattern occurring in post-menopausal, non-smoking females, predominantly having right middle lobe and left lingular bronchiectasis with a few lung nodules. This syndrome was described after the main character in Oscar Wilde's eponymous play as 'Lady Windermere syndrome'78, and was believed to occur from voluntary cough suppression79, however, subsequently, this hypothesis was discarded80. Other features include mitral valve prolapse, scoliosis and pectus excavatum; high prevalence of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD) (26-44%)81,82; increased adiponectin; decreased leptin and estrogen levels and abnormalities in fibrillin gene. Presence of all these features increases the susceptibility of these females to MAC infections83; and (iii) hypersensitivity pneumonitis-like NTM PD or 'hot tub lung' occurring due to exposure to aerosols from indoor hot tub. Various risk factors for NTM-PD are listed in Box IIA.

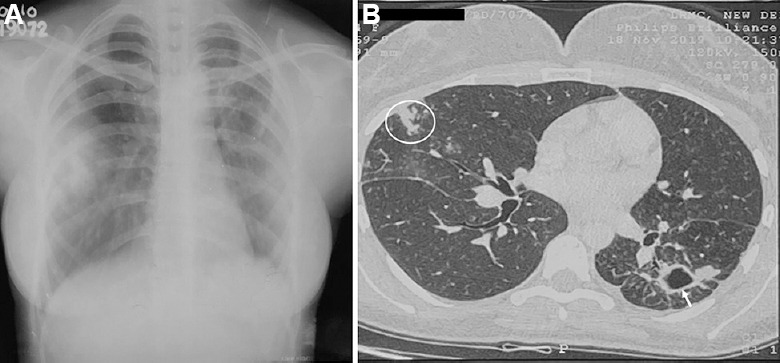

Fig. 2.

(A) Chest radiograph in a 62 yr old female with asthma, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis and bronchiectasis. Mycobacterium simiae was isolated repeatedly from the sputum. (B) High-resolution computed tomography chest (axial section) showing bilateral bronchiectasis in the right middle lobe, lingula and lower lobes.

NTM species and NTM-PD: Because of variable virulence, it is important to identify NTM species and M. abscessus subspecies for the management of NTM-PD. It has been reported that only 25-60 per cent of patients with positive respiratory specimen fulfil clinical, radiographic and microbiological criteria of NTM-PD84. Patients in whom M. kansasii and M. malmoense are isolated from respiratory specimens frequently meet clinical disease criteria, as these NTM isolates are clinically highly relevant, whereas 40-60 per cent with MAC, M. abscessus and M. xenopi and <20 per cent of patients with M. chelonae and M. fortuitum meet clinical disease criteria44,85,86,87,88,89.

The potential to produce specific clinical type of lung disease also varies among NTM species. While M. kansasii, M. xenopi and M. malmoense commonly cause fibro-cavitary disease but rarely nodular-bronchiectatic disease17,44,90,91, MAC and M. abscessus cause both types of NTM-PDs and MAC and M. immunogenum cause hypersensitivity pneumonitis-like NTM-PD17.

MAC is the most common NTM isolated from respiratory secretions in patients with NTM-PD. While a single strain of MAC species is repeatedly isolated in the cavitary type, several strains of MAC species may occur simultaneously or the strain may change sequentially in nodular-bronchiectatic type92,93. Relapse versus new re-infection of MAC infection after treatment completion can be differentiated by MAC genotyping94.

According to one study from the USA, while tap water was the source of M. avium infection, soil was the source of M. intracellulare infection94. It has been suggested that patients with M. intracellulare lung disease present at a later stage with adverse prognosis than patients with M. avium lung disease, and M. chimaera is less virulent than M. avium and M. intracellulare95,96. Significant geographic variation exists in the distribution of NTM species in the USA; where M. avium complex was the most common species isolated in the South, M. abscessus/M. chelonae was proportionately higher in the West in one study97. MAC species also vary from region to region: while M. avium is dominantly found in South America and Europe, M. intracellulare is found in South Africa and Australia23. Recurrence rates in MAC-associated lung disease also differ among MAC species95.

The second common NTM species also has a geographical variation. While M. abscessus is the second most common cause of NTM-PD in the USA98, M. kansasii in some European countries including the UK, M. xenopi in some parts of Europe and Canada and M. malmoense in northern Europe are the second most common causes of NTM-PD99. M. kansasii, one of the slowly growing NTM, is most virulent98. About 80 per cent of NTM-PD due to RGM results from M. abscessus100. There are three subspecies of M. abscessus: (i) M. abscessus subsp. abscessus, which is the most common pathogen (45-65%), followed by (ii) M. abscessus subsp. massiliense (20-55%), and (iii) M. abscessus subsp. bolletii (1-18%)101. Patients with gastro-oesophageal disease may have NTM-PD due to RGM such as M. fortuitum17.

Clinical features: Respiratory symptoms and signs in NTM-PD vary depending on the clinical type. In the cavitary type, these may be severe due to the pre-existent underlying lung disease and include shortness of breath, cough with expectoration and haemoptysis, whereas patients with nodular-bronchiectasis have milder respiratory symptoms without pre-existing parenchymal lung disease and nagging cough may be prominent. Constitutional symptoms such as fever, anorexia, progressive fatigue, malaise and weight loss may be present especially in cavitary type of NTM-PD1,17. The clinical and radiographic presentation in M. kansasii PD is similar to Mtb and includes fever, cough with or without haemoptysis and chest pain, and chest X-ray often shows infiltrates and cavitary lesions17,102 (Fig. 3). Patients with hypersensitivity pneumonitis-like NTM-PD have subacute onset of respiratory symptoms involving young individuals without pre-existing lung disease and the prognosis is good17,103,104.

Fig. 3.

Chest radiograph in a 29 yr old female patient with Mycobacterium kansasii-pulmonary disease. (A) Chest X-ray reveals a cavitary lesion in the left lung. (B) Axial section in the high-resolution computed tomography scan demonstrates a cavity in the left lung (white arrow) and tree-in-bud appearance in the right lung (white circle).

Lymphadenitis

In low TB-burden countries, single-site lymphadenitis is the most common manifestation of NTM infection in younger children74,105. Solitary lymph node is usually localized to the submandibular or cervical region and rarely, can also involve other groups either singly or multiple such as axillary, inguinal region in the disseminated NTM disease in severely immunocompromised individuals106. The lymph node enlargement usually starts as a painless swelling and later in the advanced stage, the swelling becomes fluctuant with pus inside, which may later burst out with a sinus formation. Constitutional symptoms such as fever, weight loss and fatigue may be absent. Smear microscopy and culture may be negative because of paucibacillary nature of the disease17. Molecular tests may be used to establish the diagnosis. MAC is the most frequently isolated NTM species. There is an inverse relationship of TB incidence and NTM disease and in high TB-burden countries, Mtb is the most frequent cause of lymphadenitis in all ages106.

Skin, soft tissues and bone NTM infections

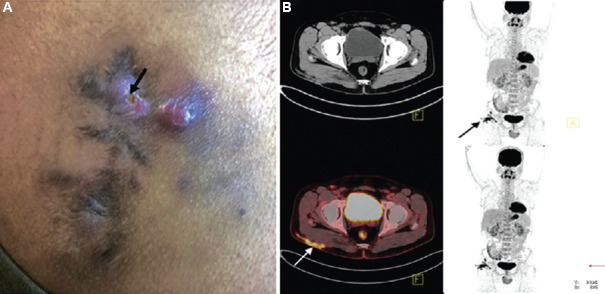

Three types of clinical presentations have been described: (i) Buruli ulcer (predominantly occurring in Uganda) or Bairnsdale ulcer disease (predominantly occurring in Australia), certain regional pockets in Latin America and China: it is a severe cutaneous disease due to M. ulcerans which progresses from nodular cutaneous lesions into large painless ulcers107. These organisms produce a toxin, mycolactone, which produces damage to the skin108. Early diagnosis and treatment is essential to minimize morbidity and costs and prevent long-term disability109; (ii) infection due to M. marinum is also known as fish-tank granuloma (previously known as swimming pool granuloma) and the infection can be acquired from swimming pools, cleaning of fish tanks or any other fish- or water-related activity110. Organisms usually gain access through skin cuts or abrasions111. It starts as a single papulonodular, verrucous or ulcerated granulomatous lesion over the hand and forearm that progresses to form multiple skin lesions in a sporotrichoid pattern - appearance which is similar to skin lesions due to Sporothrix schenckii and rarely, the underlying bone involvement occurs112; and (iii) localized skin and soft-tissue infections occurring due to RGM (M. abscessus, M. fortuitum and M. chelonae) at wound or injection sites113,114,115 (Figs. 4 and 5) and slowly growing mycobacteria in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent individuals115,116. These organisms gain access through skin breaks following trauma and surgical procedures, following the use of surgical instruments without autoclaving, during cosmetic surgery, pedicure and manicure procedures in beauty salons, surgical procedures involving placement of various implants, in mesh used for hernial site repair (Fig. 6), tattooing procedures following inoculation of contaminated ink containing M. haemophilum, intravenous punctures and lines, abscesses due to intramuscular injections through contaminated needles and use of tap water for skin cleaning112,113.

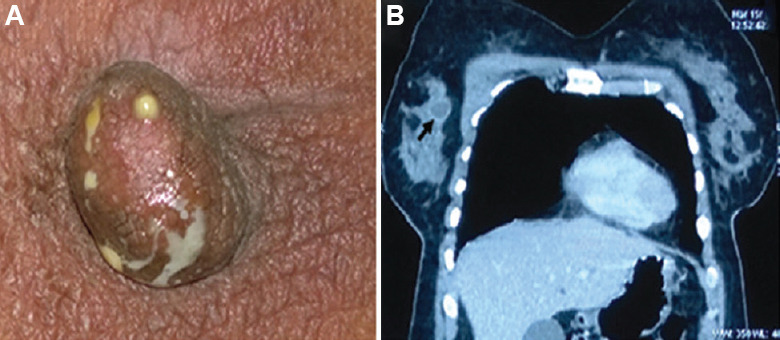

Fig. 4.

(A) A 35 yr old female presented with discharge from the right nipple, Mycobacterium abscessus was isolated from the pus on several occasions prior to treatment. (B) Computed tomography (CT)-chest showing enhancement of the margin of the abscess (black arrow) with intravenous contrast. Source: Reproduced with permission from Ref. 61.

Fig. 5.

(A) Clinical photograph of a 30 yr old male, showing right-sided post-injection gluteal abscess (black arrow) in a patient with NTM infection. (B) Transaxial fused 18F-fluorodeoxyglucosepositron emission tomography-computed tomography (18F-FDG-PET-CT) image of the same patient, at the level of acetabulum showing FDG accumulation in the subcutaneous thickening and stranding (arrow) involving the underlying right gluteus muscle superficially in right gluteal region. Source: Reproduced with permission from Ref. 61.

Fig. 6.

Clinical photograph of a 35 yr old male, showing discharging sinus (white arrow) in the abdominal wall in a patient infected with Mycobacterium abscessus following hernia repair with mesh. Source: Reproduced with permission from Ref. 61.

Disseminated NTM disease

Disseminated NTM disease due to MAC is frequent in HIV/AIDS especially in patients with CD4+ lymphocyte count <50 cells/μl. Isolated pulmonary involvement is rare in HIV/AIDS117. Pulmonary involvement occurs in 2.5-8 per cent of patients with disseminated MAC77. The portal of entry in these patients is believed to be through bowel118,119,120 and occasionally through lungs with subsequent haematogenous dissemination. MAC (predominantly M. avium) is the most common NTM species isolated in these patients17. These patients typically present with insidious onset of constitutional symptoms comprising fever with night sweats, weight loss, abdominal pain, diarrhoea and malaise17. They may have anaemia, hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy17. Somehow, disseminated NTM infections due to rapidly growing NTM (M. abscessus and M. fortuitum) are rare in HIV/AIDS patients121. Besides M. avium, less common NTM species such as M. genavense and M. simiae can also cause disseminated NTM disease in HIV/AIDS patients17.

M. kansasii can cause pulmonary involvement in HIV/AIDS patients at higher CD4+ counts, and its isolation should always be considered a potential pathogen17,122. Pulmonary involvement can also occur in other immunocompromised populations such as organ transplantation (6.5%)123, bone marrow (2.9%)124 and rarely liver and kidney transplantation. CF patients undergoing lung transplantation may develop life-threatening infection with M. abscessus124. Disseminated NTM infections can also occur in a few other rare settings (Fig. 7A-G) which will require appropriate investigations. These have been listed in (Box IIB)73. NTM, especially M. abscessus (Fig. 7) and M. fortuitum, may infect deep indwelling lines17,122. Anti-tumour necrosis factor-α agents (infliximab, etanercept and adalimumab) used to treat several diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease can predispose to both TB and NTM diseases125. A good response to rituximab in disseminated MAC patients with interferon-gamma autoantibodies has also been reported126,127.

Fig. 7.

The patient, a 14 yr old male, had disseminated Mycobacterium intracellulare infection; no immune defect could be detected. He was successfully treated. (A) The magnetic resonance imaging scan shows osteomyelitis of foot bone (black arrow). (B) Black arrow shows healing of cutaneous lesion by keloid formation. (C) Upper part of thigh shows another healed skin lesion (black arrow). (D and E) Hypodense lesions in the spleen (white open circles) and peri-splenic abscess (white arrows). (F) Bilateral conglomerate necrotic axillary (extreme-left and -right arrows) and right paratracheal lymph nodes (long and short arrows in the centre of CT image), calcification is also noted in the lymph nodes. (G) Iliopsoas abscess on the right side (white asterisk). Source: Reproduced with permission from Ref. 61.

Diagnosis

Criteria for the diagnosis of NTM disease

Healthcare providers should carefully assess causality association of the isolated NTM species with patient's symptoms and signs. Approximately, one-third of NTM species are potentially pathogenic for humans128. Some of the common pathogenic NTM species are listed in Table VII2,3,10,129. It is possible that an individual with a particular NTM isolate may not have an active disease or the isolate may not be clinically relevant. While evaluating NTM suspects, the following criteria should be followed: (i) pulmonary symptoms, nodular or cavitary opacities on chest radiograph or high-resolution CT scan that shows multifocal bronchiectasis with multiple small nodules; (ii) positive culture results from at least two separate expectorated sputum samples (if the results from the initial sputum samples are non-diagnostic, consider repeat sputum AFB smear and culture; single-positive NTM culture from CT-directed bronchoalveolar lavage or bronchial washing specimen from the affected lung segment of NTM suspect who cannot expectorate sputum or whose sputum is consistently culture negative); and (iii) other disorders such as TB and fungal infections must be excluded1,17.

Table VII.

Clinically relevant non-tuberculous mycobacteria species

| Types of disease | Names of species |

|---|---|

| Pulmonary disease | MAC, M. kansasii, M. abscessus, M. xenopi, M. simiae, M. malmoense |

| Cervico-facial lymphadenitis | M. scrofulaceum, M. avium, M. malmoense, M. lentiflavum, M. bohemicum |

| Skin and soft tissue | M. ulcerans, M. marinum, M. abscessus, M. fortuitum, M. haemophilum, M. chelonae |

| Bone and joints | MAC, M. kansasii, M. abscessus, M. xenopi, M. goodii, M. terrae |

| Disseminated disease | M. avium, M. intracellulare, M. haemophilum, M. genavense |

Differential diagnosis

Because of similar clinical features and radiographic appearances, diseases such as TB, recurrent pulmonary aspirations, pneumonitis, bronchiectasis, histoplasmosis, aspergillosis and lung cancer should be considered in the differential diagnosis and should be appropriately ruled out. In the laboratory, the presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Nocardia and Aspergillus in the specimens must be carefully tested17. It is important to consider the differential diagnosis of Sporothrix schenckii infection in patients suspected to have skin and soft-tissue NTM disease due to M. marinum113.

Specimen collection, transportation and processing

A proper sample collection is crucial to establish a correct laboratory diagnosis of NTM disease. In case of NTM-PD patients, during collection of sputum, environmental and personal contamination should be avoided. To differentiate NTM-PD from occasional presence of NTM in tracheobronchial tract, at least 3 sputum specimens should be tested on separate occasions18. Sampling from extrapulmonary specimens should be obtained directly from the lesion or organ concerned130. Further, instruments used for sampling should be devoid of any contamination, especially in hospital settings. Storage and transportation of specimens should be done carefully130. Once the specimen reaches the laboratory, the process of decontamination should be done in fully sterilized set-up. As NTM are resistant to most of the common disinfectants, careful selection of disinfectants is necessary130. Various precautions for sample collection, transportation and laboratory processing are listed in Box III130.

Box III.

Essentials for Identification of non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM)

| Sample collection and transportation to the laboratory |

| For respiratory specimens, individuals should not rinse their mouths with tap water or other fluids before submitting the specimen. |

| Use a sterile, leak proof, disposable plastic container. Avoid waxed containers. Swabs are not recommended for the isolation of mycobacteria. |

| Collect specimens aseptically, reducing contamination with indigenous microbiota. |

| Collect initial specimens before antimicrobial therapy is started. |

| Three early morning specimens collected on three consecutive days are ideal. |

| For induced sputum, sterile hypertonic saline (3-5%) should be used. Avoid contamination with nebulizer reservoir water. |

| In case of BAL or bronchial wash, bronchoscope should be sterile, cleaned with suitable disinfectant not with tap water and saline used should be devoid of any micro-organism growth. (Lidocaine used during BAL procedure may inhibit growth of NTM). |

| While collection of extrapulmonary specimens, surgical instruments should be cleaned cautiously avoiding tap water or stored water. Formalin should not be used as transfer medium. |

| Once samples stored in container, it should not be opened until it reaches to the laboratory. |

| Store at 2-8°C (do not freeze) if transport is delayed more than one hour; should not be kept more than one week |

| Precautions in the laboratory |

| Effect of disinfectant depends on concentration of the disinfectant, duration of disinfection and mycobacterial load in solution or on surface. |

| Avoid use of chlorine, benzalkonium chloride, cetylpyridinium chloride, quaternary ammonium compounds, and phenolic- or glutaraldehyde-based disinfectants as NTM are resistant to these chemicals. |

| Use of tap water or stored distilled water should be avoided. |

| Use of 70% alcohol and 5% phenol as disinfectant is recommended for bench surface cleaning and biosafety filters. |

| Autoclaving (at 131°C under 15 psi pressure) of plasticware and glassware used in laboratory is strongly recommended. |

| Laboratory workers should look for contamination by other micro-organism such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Nocardia, Aspergillus, etc. |

| Incubation temperature for every species may vary between 27-45°C and requires constant monitoring. |

| Selective drug susceptibility testing should be done. |

| Laboratory workers should be aware about the patient’s disease status and must co-ordinate the treating physician while reporting NTM species and subspecies. |

BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage. Source: Ref. 130

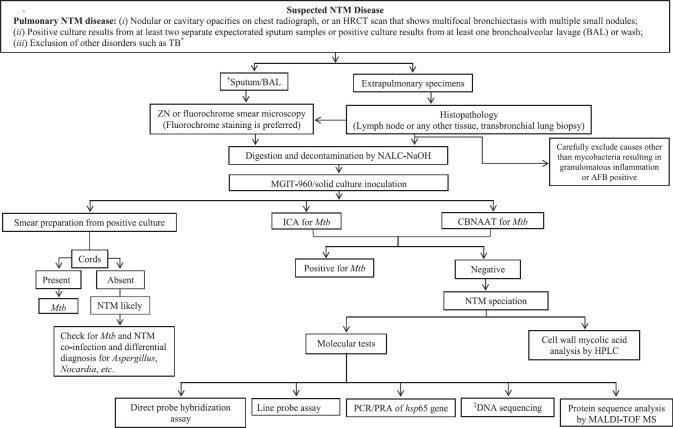

Laboratory diagnosis of NTM disease

Figure 8 illustrates various steps for NTM isolation and identification in the laboratory. Initially, the specimens are simultaneously subjected to AFB (Ziehl-Neelsen or fluorochrome) staining and GeneXpert for Mtb detection. Samples that are positive on AFB staining and negative on GeneXpert are considered NTM suspects, and the culture for such specimens should be done. Most of the NTM are cultivable in Lowenstein-Jensen, Middle-brook and Dubos Broth and Agar. A novel agar-based medium, RGM medium, has been specifically developed for the isolation of rapidly growing NTM. It provides an alternative method for the recovery of NTM from respiratory specimens, particularly from CF patients, by offering a simple and rapid method for specimen processing131. For some NTM species, additional supplements (haemin for M. haemophilum and mycobactin J for M. paratuberculosis and M. genavense)130 are added in the culture medium for optimal growth. Incubation temperatures of 36±2°C for SGM and 28±2°C for RGM have been recommended18. Appropriate adjustments in the incubation temperature (M. xenopi: 42-45°C, M. ulcerans and M. marinum: 30°C) may be done for a few NTM species18,130. Some NTM species such as M. tilburgii which are not cultivable need to be tested directly from the specimen using molecular methods132. In patients with a high suspicion of NTM-PD but negative cultures, reassessment of decontamination procedures, use of supplemented media and molecular methods may be helpful18. Culture isolates of NTM-suspected specimens should be tested with Mtb-specific tests such as MPT64 antigen immunochromatographic test or GeneXpert, and if found negative, then it is likely to be NTM and thereafter its species identification should be done.

Fig. 8.

Diagnostic algorithm for detection of NTM disease. *According to Ref. 16, consecutive three sputum samples are obtained, positive results from at least two separate expectorated sputum samples confirms the diagnosis. †While sputum collection, the patient should not rinse mouth with municipal or untreated water. Spontaneous sputum should be collected or sputum should be induced if no sputum is produced by patient. ‡Whole genome sequencing (NGS) and multi-locus targeted gene sequencing of gene such as 16S rRNA, hsp65, rpoB, 16S-23S rRNA internal transcribed region (ITS), gyrB, danA, recA and secA. HRCT, high-resolution computed tomography; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; ICA, immunochromatographic assay; CBNAAT, cartridge based nucleic acid amplification test; L-J, Lowenstein-Jensen media, HPLC: high-performance liquid chromatography, SGM, slowly growing mycobacteria; RGM, rapidly growing mycobacteria; DST, drug susceptibility testing; LPA, line probe assay; PNB: para-nitro benzoic acid; PCR/PRA, polymerase chain reaction/restriction endonuclease assay; MAC, Mycobacterium avium complex; MALDI-TOF MS, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. Source: Refs 1,17,130.

Earlier, several biochemical tests were done for NTM identification130 (Table VIII). These tests were cumbersome and time consuming and are obsolete now. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-based analysis of mycolic acid was used for NTM identification in the past. This method identifies slowly growing NTM species such as MAC and M. kansasii, but it is less specific in identifying RGM accurately130,133. It also has low discriminatory power to identify closely related SGM and RGM species130,133. These tests have now been replaced by molecular tests for NTM species and subspecies identification. These tests include polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) analysis, gene probes and line probe assays (LPA)130 (Table VIII). These molecular tests though identify a limited number of NTM species, but fail to differentiate genetically closely related NTM species133.

Table VIII.

Laboratory methods for non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) identification

| Method | Principle | Advantage(s) | Limitation(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical tests | Based on reaction products after niacin test, nitrate reduction, catalase activity, urease test, pyrazinamidase test, growth in the presence of p-nitrobenzoic acid, and hydrazide of thiophene 2-carboxylic acid | Low-cost tests and expert manpower not required | Time consuming and cumbersome tests; not useful for definitive species identification |

| HPLC | HPLC analysis of number of carbon atoms in mycolic acid found in the cell walls of NTM species | Cost of individual sample testing relatively inexpensive | Problematic for identification of rapidly-growing mycobacteria; limited ability to resolve some NTM groups/complexes |

| PCR-RFLP | Analysis of the band patterns of restricted hsp65 gene fragments which are specific for different NTM species | Specialized equipment not required | Time-consuming; analysis restricted to a small fraction of the genome; requires trained staff; different sequences may share identical RFLP patterns thus it is not useful for definitive species identification especially with newer species/subspecies |

| Nucleic acid probes | Binding of ester-labelled gene DNA probes complementary to 16S rRNA gene | Provide quick results, as analysis may be performed directly on clinical samples | Identifies M. avium, M. intracellulare, M. gordonae, M. kansasii only; shows a cross-reactivity between MAC species and other NTM species |

| LPA | Reverse hybridization of genetic probes | Nucleic acid amplification increases sensitivity; low implementation costs | Useful for species identification but there can be cross reactivity with similar species |

| Gene sequencing | TGS Sequencing of single conserved gene MSLT: multiple conserved gene sequencing and consensus analysis for NTM species identification WGS | Useful for definitive species identification for most clinically relevant species; detects previously unknown mutations. Provides more accurate results than single TGS. | Specificity depends upon selection of gene target; closely related NTM species may not be identified; requires costly specialized equipment. Requires skilled manpower; sequence analysis dependent upon updated and accurate database. |

| Sequencing of entire genome allows detection of different genetic variants within the same population; helpful in understanding geographical and environmental distribution of NTM; useful in studying disease outbreaks and transmission of NTM; also provides information about other features such as virulence and resistance to various antimicrobial agents. | Expensive; data analysis is cumbersome and difficult; drug-resistant variants may be undetected if the drug susceptible variants are in majority; currently available sequencing platforms have problems with analysis of microsatellites. | ||

| MALDI-TOF MS | Analysis of conserved protein sequences | Identifies almost 160 NTM species; most rapid NTM identification test; may identify other organisms such as Nocardia, fungi, thus useful for differential diagnosis | High initial cost; cannot differentiate between subspecies of M. abscessus and species within the MAC, M. fortuitum and M. mucogenicum groups; limited database at present |

HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography; PCR-RFLP, polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis; LPA, line probe assay; MALDI-TOF MS, matrix-assisted laser desorption time-of-flight mass spectrometry; rRNA, ribosomal RNA; TGS, targeted gene sequencing; MSLT, multi-locus sequence typing; WGS, whole genome sequencing; ITS, internal transcribed spacer; MAC, Mycobacterium avium complex. Source: Ref. 130

At present, DNA sequencing is the most accepted method for the identification and characterization of NTM species and subspecies134,135. These techniques include targeted gene sequencing and multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) that involve analysis of conserved genes such as rpoB, hsp65, 16S rRNA and 16S-23S rRNAinternal transcribed spacer (ITS) region134. Targeted sequencing of single gene may identify a reasonable number of NTM species but sometimes may not distinguish species having close genetic association. MLST is preferred as multiple conserved genes are sequenced with this technique and on the basis of consensus analysis of different gene sequences, NTM species are identified more accurately134.

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) is considered the gold standard for NTM species identification and is helpful in understanding the geographical and environmental distribution of NTM species. It is also useful to study healthcare-associated disease outbreaks and transmission134. WGS of NTM species can provide information on other characteristics such as virulence and resistance to various antimicrobial agents135,136. However, DNA sequencing is an expensive method and requires expertise130. This technique is not available in the routine laboratory set-up for NTM diagnosis in resource-limited countries130.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight-mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS)-based analysis of conserved proteins is another technique available for NTM species identification137. MALDI-TOF-MS is considered the most rapid technique137 which identifies around 160 NTM species138. However, like other techniques, MALDI-TOF-MS also fails to identify closely linked NTM species130. Details of various NTM identifications methods130 are summarized in Table VIII.

Drug susceptibility testing (DST)

DST for NTM is controversial because of discrepancy between in vitro susceptibility and the treatment response101. DST should follow the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines16. CLSI recommends that phenotypic DST should be performed using broth microdilution method18. Both phenotypic and genotypic DST for MAC and M. kansasii are performed for initial and recurrent isolates. Acquired resistance for macrolide in MAC occurs due to point mutations in the 23S rRNA (rrl) gene and for amikacin due to mutations in 16S rRNA (rrs) gene (amikacin resistance is observed in MAC isolates cultured from sputum specimens of patients who were extensively exposed to the drug or related aminoglycosides)18. For MAC, DST against macrolides [clarithromycin is used as a class agent; minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) cut-off: >32 μg/ml] and amikacin (MIC cut-off: >64 μg/ml for parenteral and >128 μg/ml for liposomal amikacin) and, for M. kansasii, DST against rifampicin (MIC >2 μg/ml) and clarithromycin are used (MIC ≥32 μg/ml)128. When M. kansasii is resistant against rifampicin, DST for amikacin, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, linezolid, minocycline, moxifloxacin, rifabutin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is recommended18. RGM species (and subspecies) show different drug resistance patterns1, and DST should be selectively done for the following antibiotics: macrolides, amikacin, tobramycin, imipenem, trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole, doxycycline, minocycline, tigecycline, cefoxitin and linezolid1,65. Information on an active erm (41) gene is important in RGM (esp. in M. abscessus subspecies) as it can lead to inducible resistance to macrolides1,17. In M. abscessus subsp massiliense, the erm (41) gene is nonfunctional owing to a large deletion, thus rendering the strains macrolide susceptible. The erm (41) gene is non-functional in some M.abscessus subsp. abscessus due to presence of C instead of T at the nucleotide 28 (arginine 10 instead of tryptophan 10)18. Constitutive resistance to macrolides can occur due to mutation in 23S rRNA gene1. Table IX describes various conditions of macrolide resistance among M. abscessus subspecies. M. chelonae is resistant to cefoxitin and sensitive to tobramycin1.

Table IX.

Interpretation of extended clarithromycin susceptibility results for Mycobacterium abscessus

| Clarithromycin susceptibility (days 3-5) | Clarithromycin susceptibility (day 14) | Genetic implication | M. abscessus subspecies | Macrolide susceptibility phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Susceptible | Susceptible | Dysfunctional erm (41) gene | M. abscessus. massiliense | Macrolide susceptible |