Abstract

Herbal medicines have drawn considerable attention with regard to their potential applications in breast cancer (BC) treatment, a frequently diagnosed malignant disease, considering their anticancer efficacy with relatively less adverse effects. However, their mechanisms of systemic action have not been understood comprehensively. Based on network pharmacology approaches, we attempted to unveil the mechanisms of FDY003, an herbal drug comprised of Lonicera japonica Thunberg, Artemisia capillaris Thunberg, and Cordyceps militaris, against BC at a systemic level. We found that FDY003 exhibited pharmacological effects on human BC cells. Subsequently, detailed data regarding the biochemical components contained in FDY003 were obtained from comprehensive herbal medicine-related databases, including TCMSP and CancerHSP. By evaluating their pharmacokinetic properties, 18 chemical compounds in FDY003 were shown to be potentially active constituents interacting with 140 BC-associated therapeutic targets to produce the pharmacological activity. Gene ontology enrichment analysis using g:Profiler indicated that the FDY003 targets were involved in the modulation of cellular processes, involving the cell proliferation, cell cycle process, and cell apoptosis. Based on a KEGG pathway enrichment analysis, we further revealed that a variety of oncogenic pathways that play key roles in the pathology of BC were significantly enriched with the therapeutic targets of FDY003; these included PI3K-Akt, MAPK, focal adhesion, FoxO, TNF, and estrogen signaling pathways. Here, we present a network-perspective of the molecular mechanisms via which herbal drugs treat BC.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is a common female malignancy and a cause of mortality globally [1]. The genetic and epigenetic dysregulations in multiple cancer-associated genes and their key oncogenic signalings are implicated in the pathology of BC; these include the phosphoinositide 3-kinase- (PI3K-) Akt, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), forkhead box O (FoxO), erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog (ErbB), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), hypoxia-inducible factor- (HIF-) 1, estrogen, p53, focal adhesion, and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways [2–4]. Currently, chemotherapy, molecular-targeted therapy, and endocrine therapy are the major pharmacological approaches for BC treatment [5–10]. However, the long-term and frequent use of the aforementioned therapeutic drugs may induce toxic events that deteriorate quality of life of cancer patients, including gastrointestinal dysfunction, fatigue, peripheral neuropathy, immunosuppression and myelosuppression, cardiotoxicity, and osteoporosis [11–18]. In addition, the pharmacological efficacy of most molecular-targeted agents often falls short of expectations because of their limited capacity to therapeutically modulate the cancerous activities of various oncogenic cellular components [19]. These issues emphasize the need for anticancer agents that can pharmacologically regulate multiple oncogenes and pathways with safety. Herbal drugs are multicomponent therapeutics that elicit their pharmacological effects via multiple chemical compounds that target diverse disease-related genes, proteins, and pathways [20, 21]. Herbal medicines have attracted much attention due to their promising anticancer effects, reduced toxicities, and lower side effects [20, 21]. Previous clinical research studies have further shown that the use of herbal drugs can improve the tumor response, survival, health status, and quality of life of patients undergoing cancer therapy [22, 23].

FDY003 is an herbal formula composed of three herbal medicines [24, 25], namely, Lonicera japonica Thunberg (LjT), Artemisia capillaris Thunberg (AcT), and Cordyceps militaris (Cm), that have been reported to exert prominent anticancer effects in various cancer types [26–35]. It has been shown that FDY003 is a potent inhibitor of proliferation while promoting the apoptotic death of cancer cells and tumors [24, 25]. These activities involve regulation of key modulators of cell cycle and apoptosis, such as p53, p21, caspase-3, and Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax) [24]. However, the molecular mechanisms of FDY003 against BC at the systemic level remain unclear.

Network pharmacology is a multidisciplinary research approach that uncovers complex disease mechanisms and can be used to formulate promising treatment strategies based on a systems perspective [36–39]. The interdisciplinary methodology integrates diverse scientific fields, such as medicine, pharmacology, network biology, systems biology, and computer science [36–39]. Network pharmacology has been demonstrated to be an efficient tool for the acquisition of comprehensive and systematic insights into the “multicompound, multitarget, multipathway” polypharmacological properties of herbal medicines, and it is extensively used to explore the active chemical compounds of herbal drugs and their therapeutic targets responsible for their pharmacological activities [36–39]. Network pharmacology investigates how associated systematic mechanisms are regulated through interactions among various key components and targets [36–39]. Here, we attempted to unravel the molecular mechanisms of anti-BC effects of FDY003 based on network pharmacology approaches.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

The MCF-7, MDA-MB-453, and MDA-MB-231 human BC cell lines were purchased from the Korean Cell Line Bank (Seoul, Korea). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM, WELGENE Inc., Daegu, Korea) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The cultured cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37°C.

2.2. Preparation of FDY003 Herbal Formula

The preparation of FDY003 was conducted as previously described [25]. In brief, the raw herbal constituents of FDY003 were obtained from Green Myeong-Poom Pharm. Co., Ltd. (Namyangju, Korea). The dried plant materials of LjT (4.16 g), AcT (6.25 g), and Cm (6.25 g) were ground, added to 70% ethanol (500 mL), and subjected to reflux extraction at 80°C for 3 h. Then, the herbal extract was filtered through a 1 μm pore filter (Hyundai Micro, Seoul, Korea) and successively purified with 80% and 90% ethanol. The resulting solution was lyophilized at −80°C. The samples were stored at −20°C and then dissolved in distilled water before the experiments.

2.3. Cell Viability Assay

The cell viability assay was performed following the previous procedures [25]. 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Cell viability was measured using the MTT assay. The cells were seeded in 96-well plates (5.0 × 104 cells per well) and then treated with the indicated drugs for 72 h in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. Subsequently, MTT solution (200 μL) was added to each well, and the cells were further incubated for 2 h. Thereafter, the resulting formazan crystals were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, and the absorbance was read with an Epoch 2 Microplate Spectrophotometer at 550 nm (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA).

2.4. Exploration of Active Chemical Compounds

Comprehensive information on the phytochemical components of FDY003 was integrated from traditional Chinese medicine systems pharmacology (TCMSP) and anticancer herbs database of systems pharmacology (CancerHSP) databases [40, 41]. To determine the bioactive compounds of FDY003, we assessed the key absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) pharmacokinetic parameters (i.e., oral bioavailability (OB), drug-likeness (DL), and Caco-2 permeability) of chemical constituents obtained from the TCMSP database [40]. OB, a pivotal consideration in drug development, is a measurement of the rate, fraction, and extent of an orally administered drug that reaches the expected site of drug action [40, 42]. Caco-2 permeability is a parameter widely used for the evaluation of the intestinal absorption rate and extent of a given substance using Caco-2 human intestinal epithelial cells [40, 43–45]. In general, drug molecules with a Caco-2 permeability less than −0.4 are considered not permeable across the epithelium of intestines [40, 46, 47]. DL is an indicator that is used to assess whether a compound has the potential to be developed into a drug with respect to its physical and chemical properties; it is calculated based on the Tanimoto coefficient and relevant molecular descriptors [40, 48]. A chemical compound is considered active if it meets the following criteria: OB ≥ 30%, Caco-2 permeability ≥ −0.4, and DL ≥ 0.18 [37, 40, 49, 50].

2.5. Target Identification for the Active Compounds

Molecular targets of the bioactive compounds of FDY003 were determined using comprehensive information regarding chemical-protein interactions obtained from various relevant databases, including Search Tool for Interactions of Chemicals (STITCH) 5 [51], SwissTargetPrediction [52, 53], PharmMapper [54], and Similarity Ensemble Approach (SEA) [55]. We also used in silico models, such as systematic drug targeting tool (SysDT) [56] and weighted ensemble similarity (WES) algorithm [57], for target identification according to previously described procedures [58–63]. Human genes/proteins related to the pathology of BC were obtained from the following databases: Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) [64], GeneCards [65], Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD) [66], DisGeNET [67], Human Genome Epidemiology (HuGE) Navigator [68], Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) [69], Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase (PharmGKB) [70], and DrugBank [71].

2.6. Network Construction

The herbal medicine-bioactive compound (H-C) and bioactive compound-target (C-T) networks were generated by connecting the three herbal constituents of FDY003 with the bioactive compounds and the bioactive compounds with the targets. The target-pathway (T-P) network was generated by connecting the targets with relevant biological pathways. The protein-protein interaction (PPI) network was generated based on the interactions between the targets (confidence score ≥ 0.9) using the STRING database [72]. Network visualization and analysis were performed with Cytoscape [73]. In the presented data, nodes indicate the herbal constituents, active chemical constituents, targets, or pathways, and edges (or links) indicate their interactions [74]. The degree indicates the number of edges of a node in a network [74].

2.7. Contribution Index Analysis

The contribution of chemical compounds to the pharmacological activity of FDY003 was analyzed using a contribution index (CI) [50] that can be calculated using the following formula:

| (1) |

twhere NE indicates the network-based efficacy, n indicates the number of targets of chemical component j, di indicates the number of links of target i of chemical component j, m indicates the number of chemical components, and ci (or cj) indicates the number of previous literatures containing the terms “breast cancer” and the common name of chemical component i (or j) in their title or abstract that were retrieved from the PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). If the sum of the highest CIs is greater than 85%, the compounds with those CIs are considered the major contributors, as previously suggested [50].

2.8. Functional Enrichment Analysis

Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed using g:Profiler [75], and pathway enrichment analysis was carried out with Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases [76].

3. Results

3.1. Anticancer Properties of FDY003 against Breast Cancer

To investigate whether FDY003 exerts therapeutic effects on BC cells, we treated MCF-7 (an estrogen receptor-positive human BC cell line), MDA-MB-453 (a human epidermal growth factor receptor 2- (HER2-) positive human BC cell line), and MDA-MB-231 (a triple-negative human BC cell line) cells with FDY003 for 72 h and observed their responses. We found that FDY003 repressed the viability of MCF-7 (IC50 = 242.90 μg/mL), MDA-MB-453 (IC50 = 156.01 μg/mL), and MDA-MB-231 (IC50 = 197.56 μg/mL) cells (Supplementary Figure S1), suggesting that the herbal medicine possesses anti-BC properties.

3.2. Chemical Components of FDY003

The chemical compounds that are present in FDY003 were obtained from the comprehensive databases associated with herbal medicine such as TCMSP and CancerHSP [40, 41]. Accordingly, 323 compounds were retrieved for FDY003 after removing duplicates (Supplementary Table S1).

3.3. Active Chemical Compounds in FDY003

Compounds whose pharmacokinetic parameters met the following criteria were considered active as described in Section 2.4: OB ≥ 30%, Caco-2 permeability ≥ −0.4, and DL ≥ 0.18 [49, 50]. A number of compounds not satisfying the aforementioned criteria were also considered bioactive because they were present in large amounts in herbal medicines and were known to have potent pharmacological efficacy. As a result, we obtained 20 active compounds for FDY003 (Supplementary Table S2).

3.4. Targets of Active Chemical Compounds in FDY003

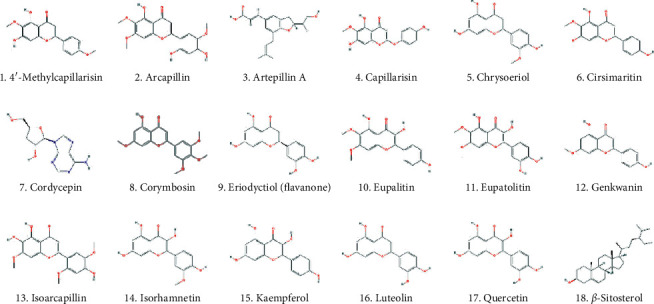

We used comprehensive chemical-protein interaction data obtained from various relevant databases, including STITCH [51], SEA [55], SwissTargetPrediction [52, 53], and PharmMapper [54] to explore the molecular targets for the bioactive chemical components in FDY003. In addition, in silico models, such as SysDT [56] and WES algorithms [57], were used for the target exploration based on previously described procedures [58–63]. Consequently, we obtained 196 targets for the 18 active compounds (i.e., 4′-methylcapillarisin, arcapillin, artepillin A, capillarisin, chrysoeriol, cirsimaritin, cordycepin, corymbosin, eriodyctiol (flavanone), eupalitin, eupatolitin, genkwanin, isoarcapillin, isorhamnetin, kaempferol, luteolin, quercetin, and β-sitosterol) in FDY003 (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S3). No interacting targets were retrieved for the compounds “loniceracetalides B_qt” and “demethoxycapillarisin.”

Figure 1.

The active chemical compounds of FDY003.

3.5. Network Pharmacology Study on the Molecular Mechanisms of FDY003

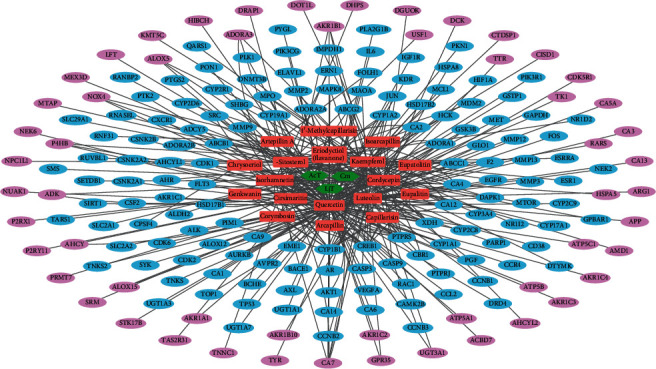

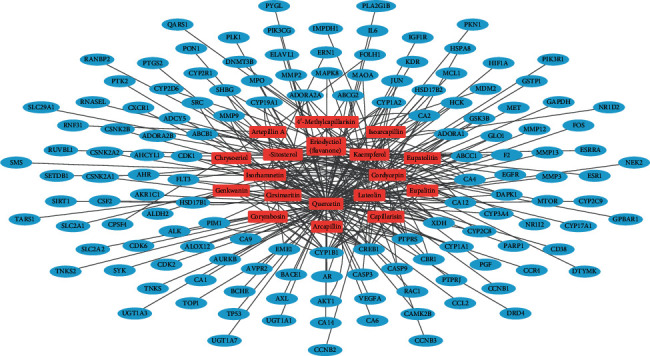

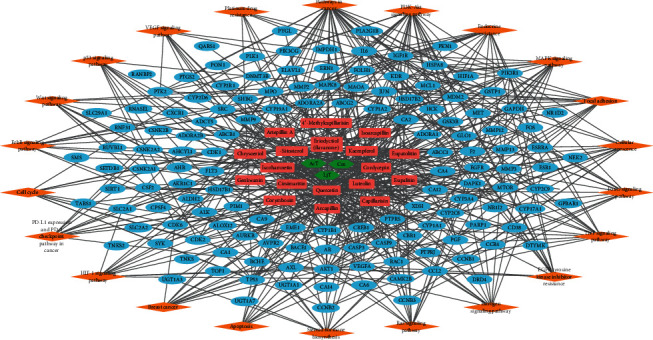

To conduct network pharmacology analysis of the molecular mechanisms of FDY003 against BC, we first generated an herbal medicine-bioactive compound-target (H-C-T) network of the herbal formula by linking the herbal medicines with their bioactive chemical components and the components with the targets (Figure 2). The resulting H-C-T network contained 217 nodes (3 herbal medicines, 18 active chemical components, and 196 targets) and 354 edges (Figure 2). In addition, to obtain insight into the BC-associated pharmacological features of FDY003, we constructed a C-T network (158 nodes with 254 edges) by connecting the bioactive chemical components with the BC-associated targets (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table S3). The quercetin, luteolin, kaempferol, cordycepin, eriodyctiol (flavanone), isorhamnetin, and β-sitosterol exhibited the highest degrees (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table S3), implying that they are essential for the mediation of the anticancer effects of FDY003 against BC. Furthermore, 42 BC-associated targets interacted with two or more compounds (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table S3), supporting the polypharmacological characteristics of FDY003.

Figure 2.

Herbal medicine-active chemical compound-target network of FDY003. Green hexagons, herbal medicines; red rectangles, active chemical compounds; blue ellipses, BC-associated targets; purple ellipses, non-BC-associated targets.

Figure 3.

Active chemical component-target network of FDY003. Red rectangles, bioactive chemical components; blue ellipses, breast cancer-associated targets.

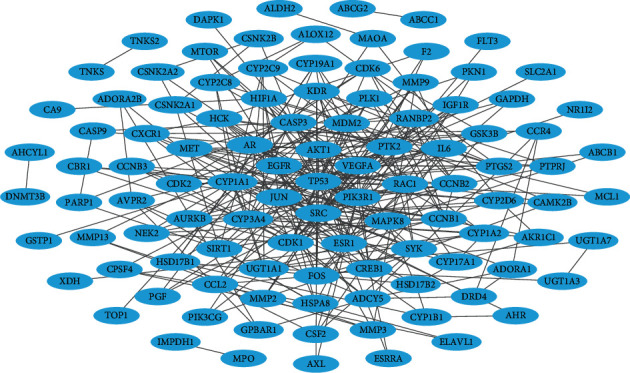

To investigate the interactive associations among the targets, we built a PPI network (106 nodes and 315 edges) consisting of the BC-associated therapeutic targets of FDY003 (Figure 4). Subsequently, we explored the existence of hubs (i.e., nodes with relatively high degrees that tend to play prominent roles in the cellular processes in a network) [77, 78]. In the analysis, we defined hubs as nodes with degrees equal to or greater than twice the mean node degree [79, 80]. Among the BC-associated targets of FDY003, TP53, SRC, PIK3R1, VEGFA, AKT1, EGFR, CYP1A1, CYP3A4, JUN, CDK1, and ESR1 were hub nodes (Figure 4), suggesting that the nodes act as important targets mediating the therapeutic effects of FDY003 against BC cells. Loss of function of p53 (encoded by TP53) due to genetic alterations has been shown to drive the tumorigenesis, progression, and metastasis of BC; p53 expression has been reported to be a potential prognostic indicator for BC patients [81–89]. The dysregulation and elevated activity of the kinase Src (encoded by SRC) is frequently observed in multiple human malignancies, including BC, and it promotes the invasion, metastasis, migration, and proliferation of BC cells [90–94]. The expression and activity of SRC or PIK3R1 are highly upregulated in malignant breast tumor tissues and have been correlated with decreased survival of BC patients [95–97]. VEGF-A (encoded by VEGFA) is a crucial regulator in the proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastatic behavior of BC cells, and it confers resistance against chemotherapy [98–101]. The overexpression or hyperactivation of AKT (encoded by AKT1), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR; encoded by EGFR), or c-Jun (encoded by JUN) promotes various cancerous processes, including proliferation, growth, survival, invasion, and migration of BC cells and is further related to the poorer clinical outcomes of BC patients [102–127]. Such targets have been implicated in reduced drug sensitivity of cancer cells to chemotherapeutics; therefore, targeting them could improve the therapeutic efficacy of chemotherapy and radiotherapy in BC [104–106, 109, 111–113, 117, 119, 123, 125, 126, 128–131]. Cytochrome P450 1A1 (encoded by CYP1A1) and cytochrome P450 3A4 (encoded by CYP3A4) are modulators of estrogen metabolism, and their activities are involved in the cancerous processes of BC cells [132–139]. Genetic polymorphism and expression of CYP3A1 or CYP3A4 in breast tumor tissues have been reported to be potentially useful factors for the prediction of treatment responses to chemotherapy [140, 141]. CDK1 (encoded by CDK1) functions as a crucial regulator in cell cycle progression, and its dysregulation leads to aberrant proliferation of BC cells [142]. Previous studies have indicated that CDK1 activity may act as a prognostic indicator in BC, and CDK1 targeting can increase chemotherapeutic efficacy [143–147]. Abnormal activity of estrogen receptor α (encoded by ESR1) is considered primarily responsible for tumorigenesis and progression of BC, and the receptor is the most promising therapeutic target [134–139].

Figure 4.

Protein-protein interaction network for breast cancer-associated targets of FDY003. Nodes refer to the breast cancer-related targets of FDY003.

To assess the contribution of the chemical components to the pharmacological effects of FDY003, we calculated CIs for the individual active compounds (Section 2.7) [50, 148]. As a result, quercetin and luteolin had the highest CIs with a sum of 91.83% (Supplementary Figure S2), which suggests that the two active components are key factors contributing to the FDY003 anticancer properties in BC treatment.

Overall, the results of the analyses above facilitate the identification of the polypharmacological mechanisms of FDY003 activity against BC.

3.6. Functional Enrichment Analysis for the FDY003 Network

To investigate the biological roles of the BC-related targets of FDY003, we carried out GO enrichment analysis for the targets. These targets were enriched in GO terms for the modulation of biological processes, involving cell proliferation, cell cycle progression, and cell apoptosis (Supplementary Figure S3), highlighting the molecular properties of FDY003 activity.

The aberrant activities of oncogenic cellular signalings are known to be responsible for cancer development and progression [149]. To this end, we next carried out pathway enrichment analysis for its BC-related targets (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure S3). We found that the following diverse pathways, which importantly function in the tumorigenesis and progression of BC, were significantly enriched with the FDY003 targets: “Pathways in cancer,” “PI3K-Akt signaling pathway,” “Endocrine resistance,” “MAPK signaling pathway,” “Focal adhesion,” “Cellular senescence,” “FoxO signaling pathway,” “TNF signaling pathway,” “EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance,” “Estrogen signaling pathway,” “Ras signaling pathway,” “Steroid hormone biosynthesis,” “Apoptosis,” “Breast cancer,” “HIF-1 signaling pathway,” “PD-L1 expression and PD-1 checkpoint pathway in cancer,” “Cell cycle,” “ErbB signaling pathway,” “Wnt signaling pathway,” “p53 signaling pathway,” “VEGF signaling pathway,” and “Platinum drug resistance” (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure S3). The dysregulation of PI3K-Akt, MAPK, focal adhesion, and Ras signaling pathways promotes diverse cancerous cell processes, including the uncontrolled cell proliferation, invasion, migration, survival, metastasis, and angiogenesis of BC cells [3, 126, 150–154]. Abnormalities of crucial cellular function, such as senescence, apoptosis, and cell cycle, are the important pathological processes of BC [155–160]. The TNF signaling pathway is a mediator of the inflammatory process, and its activity is closely linked with the progression, metastasis, and poor prognosis of BC [161, 162]. The estrogen signaling pathway functions as the most critical regulator of tumor initiation and malignant progression in BC, and therapeutic modulation of its activity serves as a primary treatment strategy [163–167]. Previous studies have suggested that expression of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) serves as a prognostic factor for the survival of patients with BC and that inhibition of the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/PD-L1 pathway can enhance antitumor responses [168–172]. The HIF-1 and Wnt signaling regulate various cellular behaviors, involving cell proliferation, metastasis, and stem cell-like characteristics in BC cells [173–180]. The p53 signaling pathway exerts tumor-suppressive activity associated with cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and cellular senescence, and loss of function of its key pathway components has been implicated in the carcinogenesis of BC and is a negative prognostic factor for patient survival [85, 181]. The VEGF signaling pathway plays a protumoral role by increasing angiogenesis, thus promoting the survival, migration, and invasion of BC cells [101, 182]. In addition, resistance to platinum-based drugs, endocrine therapy, and EGFR signaling inhibitors are major obstacles in BC treatment [183–189].

Figure 5.

Herbal medicine-compound-target-pathway network of FDY003. Green hexagons, herbal medicines; red rectangles, bioactive chemical components; blue ellipses, breast cancer-related targets; orange diamonds, signaling pathways.

We further analyzed the functional associations among FDY003 targets using GeneMANIA [190], an algorithm useful for the analysis of biological functions of cellular components based on extensive network integration. Among the BC-associated targets of FDY003, 38.32% and 33.65% of them tended to be coexpressed and physically interacting, respectively (Supplementary Figure S4), suggesting that they have similar biological roles and functions.

Together, the results above suggest that FDY003 exerts the pharmacological activity by targeting diverse BC-associated oncogenic signaling pathways and the modulation of relevant biological functions.

4. Discussion

BC is a common cancer type and ranks as the leading cause of death among women globally [1]. Herbal medicines are attracting considerable attention for potential applications in cancer treatment owing to their high anticancer activities, reduced toxicity, and minimal adverse effects [21]. Based on a network pharmacology analysis, we explored the molecular mechanisms of the therapeutic effects of FDY003 for BC. (i) FDY003 exhibited anticancer effects on human BC cells (Supplementary Figure 1). (ii) Eighteen potentially active compounds (i.e., 4′-methylcapillarisin, arcapillin, artepillin A, capillarisin, chrysoeriol, cirsimaritin, cordycepin, corymbosin, eriodyctiol (flavanone), eupalitin, eupatolitin, genkwanin, isoarcapillin, isorhamnetin, kaempferol, luteolin, quercetin, and β-sitosterol) present in FDY003 may interact with 140 BC-associated therapeutic targets and induce the pharmacological activity of the herbal drug (Figures 1–4). (iii) GO terms for the modulation of cellular processes were significantly enriched for the FDY003 targets, including cell proliferation, cell cycle process, and cell apoptosis (Supplementary Figure 3). In addition, (iv) diverse pathways that play key roles in BC pathology were enriched for the targets that included PI3K-Akt, MAPK, focal adhesion, FoxO, TNF, and estrogen signaling pathways (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure 3).

The FDY003 constituents have been reported to exert inhibitory effects against BC. AcT inhibited the proliferation but induced the death of BC cells [191]. Cm has been previously demonstrated to reduce the migratory and proliferative capacities of BC cells and to stimulate apoptosis by promoting caspase activation and Akt inactivation [29, 35, 192, 193]. Cm also has immunomodulatory properties that can inhibit the growth of breast tumors [194]. Capillarisin exhibits its anticancer effects by attenuating the invasive and proliferative properties of BC cells [195]. Chrysoeriol treatment has been reported to promote apoptosis and cell cycle arrest and further repress the invasion, proliferation, and migration of BC cells [196, 197]. Cirsimaritin inhibits proliferation and angiogenesis via the downregulation of VEGF, Akt, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) [198]. Cordycepin is a potent inhibitor of the invasion and proliferation of BC cells while inducing their apoptosis through the regulation of MAPK and caspase-dependent pathways [199–203]. Cordycepin has also been shown to function as a radiosensitizer that can enhance the efficacy of radiotherapy toward BC cells [204]. Genkwanin modulates the activities of CYP1 enzymes and PI3K/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways, thereby suppressing proliferation and inducing apoptosis of BC cells [205–207]. Isorhamnetin exerts the anticancer activity against BC cells by inhibiting their proliferative and invasive abilities [208–210]. β-Sitosterol activates key apoptotic pathways, including Fas and caspase signaling pathways, and reduces the viability of BC cells [211–214]. Furthermore, β-sitosterol has been demonstrated to elevate the pharmacological effectiveness of tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator that is extensively applied in clinical practice [215]. Kaempferol, luteolin, and quercetin stimulate apoptotic cell death but inhibit cell processes, including proliferation, cell cycle progression, angiogenesis, migration, invasion, metastasis, and cancer stemness; such effects occur via the regulation of important BC-associated pathways such as the Akt, caspase, EGFR, estrogen, HER2, MAPK, insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1, Notch, and Wnt signaling pathways [216–266]. The three chemical compounds have also been shown to sensitize BC cells to various anticancer drugs, including cisplatin, docetaxel, doxorubicin, lapatinib, paclitaxel, rapamycin, sorafenib, tamoxifen, topotecan, and vincristine [267–286]. For instance, luteolin can synergistically enhance the growth-suppression and apoptosis-inducing activities of the anticancer agent celecoxib against BC cells by blocking the activation of oncogenic Akt and ERK signaling [271, 272]. The combined treatment of quercetin with kaempferol or luteolin has synergistic antiproliferative effects that are greater than those of either treatment exclusively [287, 288]. The risk of BC incidence showed a tendency to be lower in women with higher quercetin intakes [289].

Pharmacologic effects of FDY003 in cancer cells have been previously reported [24, 25]. FDY003 has been reported to exert its anticancer effects through the regulation of the activities of key mediators of apoptosis and cell cycle progression; these involved Bax, caspase-3, p21, and p53 that induce apoptosis while suppressing the proliferative and survival capacities of cancer cells [24, 25]. Treatment with the herbal formula further inhibited tumor growth in xenograft mice bearing human cancer cells [24], suggesting in vivo therapeutic effects against cancer. Contrary to the treatment with irinotecan, a clinically used cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agent [290], body weight loss (a parameter used to evaluate the potential toxicity of drug treatments in animal experiments) did not occur in FDY003-administered xenograft mice [24], suggesting tolerability of the herbal drug as well as its antitumor activity. Future experimental studies should (i) investigate the pharmacological effects of FDY003 in diverse types of cancer, (ii) explore the mechanisms underlying the anticancer activity of the herbal formula such as its immunomodulatory effects, and (iii) evaluate the anticancer effectiveness and safety of FDY003 combined with other widely used therapeutic approaches (i.e., chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and targeted molecular therapy). Such studies would facilitate the development of safer and more effective herbal medicine-based strategies for BC treatment.

5. Conclusions

We explored the systematic mechanisms of FDY003 activity against BC based on a network pharmacology analysis. FDY003 elicited anticancer effects on human BC cells. Eighteen chemical compounds in FDY003 were identified as potentially bioactive compounds that could target 140 BC-associated genes/proteins and exhibit therapeutic effects. The FDY003 targets were enriched in GO terms associated with the modulation of cellular processes, involving cell proliferation, cell cycle progression, and cell apoptosis. Pathway enrichment analysis of the targets further demonstrated that diverse pathways crucial for the BC pathology were significantly enriched with the FDY003 targets, involving the PI3K-Akt, MAPK, focal adhesion, FoxO, TNF, and estrogen signaling pathways. Based on a network perspective, our findings offer in-depth insights into the therapeutic properties of herbal medicines in BC treatment. Future studies should explore the potential efficacy of the herbal formula in other cancer types as well as its potential efficacy and safety profiles in combination with other therapies.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Fore and Forest Hospital.

Abbreviations

- AcT:

Artemisia capillaris Thunberg

- ADME:

Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion

- Bax:

Bcl-2-associated X protein

- C-T:

Compound-target

- CI:

Contribution index

- Cm:

Cordyceps militaris

- CTD:

The Comparative Toxicogenomics Database

- CYP:

Cytochrome P450

- DL:

Drug-likeness

- EGFR:

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- ErbB:

Erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog

- FoxO:

Forkhead box protein O

- GO:

Gene ontology

- H-C:

Herb-compound

- H-C-T:

Herb-target-pathway

- HIF-1:

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1

- HuGE Navigator:

Human Genome Epidemiology Navigator

- KEGG:

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- LjT:

Lonicera japonica Thunberg

- MAPK:

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MTT:

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- NE:

Network-based efficacy

- OB:

Oral bioavailability

- OMIM:

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man

- PD-1:

Programmed cell death protein 1

- PD-L1:

Programmed death-ligand 1

- PharmGKB:

Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase

- PI3K:

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PPI:

Protein-protein interaction

- QOL:

Quality of life

- SEA:

Similarity ensemble approach

- STITCH:

Search Tool for Interactions of Chemicals

- SysDT:

Systematic drug targeting tool

- TCMSP:

Traditional Chinese medicine systems pharmacology

- TTD:

Therapeutic Target Database

- TNF:

Tumor necrosis factor

- T-P:

Target-pathway

- VEGF:

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- WES algorithm:

Weighted ensemble similarity algorithm.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1. Effects of FDY003 on the viability of breast cancer cells. Supplementary Figure S2. Contribution index of active compounds in FDY003. Supplementary Figure S3. Functional enrichment analysis for the breast cancer-associated targets of FDY003. Supplementary Figure S4. Functional interaction analysis for the breast cancer-associated targets of FDY003. Supplementary Table S1. List of the chemical compounds in FDY003. Supplementary Table S2. List of the active chemical compounds in FDY003. Supplementary Table S3. List of the targets of active chemical compounds in FDY003.

References

- 1.DeSantis C. E., Ma J., Gaudet M. M., et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2019. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2019;69(6):438–451. doi: 10.3322/caac.21583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Becerra R., Santos N., Diaz L., Camacho J. Mechanisms of resistance to endocrine therapy in breast cancer: focus on signaling pathways, miRNAs and genetically based resistance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020;14(1):108–145. doi: 10.3390/ijms14010108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McAuliffe P. F., Meric-Bernstam F., Mills G. B., Gonzalez-Angulo A. M. Deciphering the role of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in breast cancer biology and pathogenesis. Clinical Breast Cancer. 2010;10(3):S59–S65. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2010.s.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zardavas D., Baselga J., Piccart M. Emerging targeted agents in metastatic breast cancer. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2013;10(4):191–210. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.den Hollander P., Savage M. I., Brown P. H. Targeted therapy for breast cancer prevention. Frontiers in Oncology. 2013;3:p. 250. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li X., Lewis M. T., Huang J., et al. Intrinsic resistance of tumorigenic breast cancer cells to chemotherapy. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100(9):672–679. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nahta R., Yu D., Hung M. C., Hortobagyi G. N., Esteva F. J. Mechanisms of disease: understanding resistance to HER2-targeted therapy in human breast cancer. Nature Clinical Practice Oncology. 2006;3(5):269–280. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piccart-Gebhart M. J., Procter M., Leyland-Jones B., et al. Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(16):1659–1672. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romond E. H., Perez E. A., Bryant J., et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(16):1673–1684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rouzier R., Perou C. M., Symmans W. F., et al. Breast cancer molecular subtypes respond differently to preoperative chemotherapy. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005;11(16):5678–5685. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abotaleb M., Kubatka P., Caprnda M., et al. Chemotherapeutic agents for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer: an update. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2018;101:458–477. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.02.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ali S., Rasool M., Chaoudhry H., et al. Molecular mechanisms and mode of tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. Bioinformation. 2016;12(3):135–139. doi: 10.6026/97320630012135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ariazi E. A., Ariazi J. L., Cordera F., Jordan V. C. Estrogen receptors as therapeutic targets in breast cancer. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;6(3):181–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farolfi A., Melegari E., Aquilina M., et al. Trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity in early breast cancer patients: a retrospective study of possible risk and protective factors. Heart. 2013;99(9):634–639. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiuza M. Cardiotoxicity associated with trastuzumab treatment of HER2+ breast cancer. Advances in Therapy. 2009;26(1):S9–S17. doi: 10.1007/s12325-009-0048-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayer E. L., Burstein H. J. Chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America. 2007;21(2):257–272. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Partridge A. H., Burstein H. J., Winer E. P. Side effects of chemotherapy and combined chemohormonal therapy in women with early-stage breast cancer. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2001;30:135–142. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramaswamy B., Shapiro C. L. Osteopenia and osteoporosis in women with breast cancer. Seminars in Oncology. 2003;30(6):763–775. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2003.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimmermann G. R., Lehar J., Keith C. T. Multi-target therapeutics: when the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. Drug Discovery Today. 2007;12(1-2):34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohnishi S., Takeda H. Herbal medicines for the treatment of cancer chemotherapy-induced side effects. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2015;6:p. 14. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poornima P., Kumar J. D., Zhao Q., Blunder M., Efferth T. Network pharmacology of cancer: from understanding of complex interactomes to the design of multi-target specific therapeutics from nature. Pharmacological Research. 2016;111:290–302. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yin S. Y., Wei W. C., Jian F. Y., Yang N. S. Therapeutic applications of herbal medicines for cancer patients. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;2013:15. doi: 10.1155/2013/302426.302426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu L., Li L., Li Y., Wang J., Wang Q. Chinese herbal medicine as an adjunctive therapy for breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2016;2016:17. doi: 10.1155/2016/9469276.9469276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee I.-H., Lee D.-Y. FDY003 inhibits colon cancer in a Colo205 xenograft mouse model by decreasing oxidative stress. Pharmacognosy Magazine. 2019;15(65):p. 675. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee H.-S., Lee I.-H., Kang K., et al. Systems pharmacology study of the anticervical cancer mechanisms of FDY003. Natural Product Communications. 2020;15(12) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng G., Wang X., You C., et al. Antiproliferative potential of Artemisia capillaris polysaccharide against human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2013;92(2):1040–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hokin-Neaverson M., Jefferson J. W. Deficient erythrocyte NaK-ATPase activity in different affective states in bipolar affective disorder and normalization by lithium therapy. Neuropsychobiology. 1989;22(1):18–25. doi: 10.1159/000118587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jang E., Kim S. Y., Lee N. R., et al. Evaluation of antitumor activity of Artemisia capillaris extract against hepatocellular carcinoma through the inhibition of IL-6/STAT3 signaling axis. Oncology Reports. 2017;37(1):526–532. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.5283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin C. Y., Kim G. Y., Choi Y. H. Induction of apoptosis by aqueous extract of Cordyceps militaris through activation of caspases and inactivation of Akt in human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 Cells. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2008;18(12):1997–2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim J., Jung K. H., Yan H. H., et al. Artemisia Capillaris leaves inhibit cell proliferation and induce apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies. 18(1):p. 147. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2217-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park K. I., Park H., Nagappan A., et al. Polyphenolic compounds from Korean Lonicera japonica Thunb. induces apoptosis via AKT and caspase cascade activation in A549 cells. Oncology Letters. 2017;13(4):2521–2530. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rao Y. K., Fang S. H., Wu W. S., Tzeng Y. M. Constituents isolated from Cordyceps militaris suppress enhanced inflammatory mediator’s production and human cancer cell proliferation. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2010;131(2):363–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoo H. S., Shin J. W., Cho J. H., et al. Effects of Cordyceps militaris extract on angiogenesis and tumor growth. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2004;25(5):657–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou Q., Zhang Z., Song L., et al. Cordyceps militaris fraction inhibits the invasion and metastasis of lung cancer cells through the protein kinase B/glycogen synthase kinase 3beta/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Oncology Letters. 2018;16(6):6930–6939. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.9518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen C., Wang M.-L., Jin C., et al. Cordyceps militaris polysaccharide triggers apoptosis and G0/G1 cell arrest in cancer cells. Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology. 2015;18(3):433–438. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hao da C., Xiao P. G. Network pharmacology: a Rosetta Stone for traditional Chinese medicine. Drug Discovery Today. 2014;75(5):299–312. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee H. S., Lee I. H., Park S. I., Lee D. Y. Network pharmacology-based investigation of the system-level molecular mechanisms of the hematopoietic activity of samul-tang, a traditional Korean herbal formula. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/9048089.9048089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee W. Y., Lee C. Y., Kim Y. S., Kim C. E. The methodological trends of traditional herbal medicine employing network pharmacology. Biomolecules. 2019;9:8. doi: 10.3390/biom9080362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang G. B., Li Q. Y., Chen Q. L., Su S. B. Network pharmacology: a new approach for Chinese herbal medicine research. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;2013:9. doi: 10.1155/2013/621423.621423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ru J., Li P., Wang J., et al. TCMSP: a database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. Journal of Cheminformatics. 2014;6:p. 13. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tao W., Li B., Gao S., et al. CancerHSP: anticancer herbs database of systems pharmacology. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:p. 11481. doi: 10.1038/srep11481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang C. K., Craik D. J. Cyclic peptide oral bioavailability: lessons from the past. Biopolymers. 2016;106(6):901–909. doi: 10.1002/bip.22878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia M. N., Flowers C., Cook J. D. The Caco-2 cell culture system can be used as a model to study food iron availability. Journal of Nutrition. 1996;126(1):251–258. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.1.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kono Y., Iwasaki A., Matsuoka K., Fujita T. Effect of mechanical agitation on cationic liposome transport across an unstirred water layer in caco-2 cells. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2016;39(8):1293–1299. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b16-00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Volpe D. A. Variability in Caco-2 and MDCK cell-based intestinal permeability assays. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2008;97(2):712–725. doi: 10.1002/jps.21010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Y., Zhang J., Zhang L., et al. Systems pharmacology to decipher the combinational anti-migraine effects of Tianshu formula. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2015;174:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang J., Li Y., Chen X., Pan Y., Zhang S., Wang Y. Systems pharmacology dissection of multi-scale mechanisms of action for herbal medicines in stroke treatment and prevention. PLoS One. 2014;9(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102506.e102506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee A. Y., Park W., Kang T. W., Cha M. H., Chun J. M. Network pharmacology-based prediction of active compounds and molecular targets in Yijin-Tang acting on hyperlipidaemia and atherosclerosis. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2018;221:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang J., Cheung F., Tan H. Y., et al. Identification of the active compounds and significant pathways of yinchenhao decoction based on network pharmacology. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2017;16(4):4583–4592. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.7149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yue S. J., Xin L. T., Fan Y. C., et al. Herb pair Danggui-Honghua: mechanisms underlying blood stasis syndrome by system pharmacology approach. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:p. 40318. doi: 10.1038/srep40318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Szklarczyk D., Santos A., von Mering C., Jensen L. J., Bork P., Kuhn M. STITCH 5: augmenting protein-chemical interaction networks with tissue and affinity data. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;44(D1):D380–D384. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V. SwissTargetPrediction: updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Research. 2019;47(W1):W357–W364. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gfeller D., Grosdidier A., Wirth M., Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V. SwissTargetPrediction: a web server for target prediction of bioactive small molecules. Nucleic Acids Research. 2014;42:W32–W38. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang X., Shen Y., Wang S., et al. PharmMapper 2017 update: a web server for potential drug target identification with a comprehensive target pharmacophore database. Nucleic Acids Research. 2017;45(W1):W356–W360. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Keiser M. J., Roth B. L., Armbruster B. N., Ernsberger P., Irwin J. J., Shoichet B. K. Relating protein pharmacology by ligand chemistry. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(2):197–206. doi: 10.1038/nbt1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu H., Chen J., Xu X., et al. A systematic prediction of multiple drug-target interactions from chemical, genomic, and pharmacological data. PLoS One. 2012;7(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037608.e37608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zheng C., Guo Z., Huang C., et al. Large-scale direct targeting for drug repositioning and discovery. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:p. 11970. doi: 10.1038/srep11970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu J., Jiang M., Li Z., et al. A novel systems pharmacology method to investigate molecular mechanisms of scutellaria barbata D. Don for non-small cell lung cancer. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2018;9:p. 1473. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Su X., Li Y., Jiang M., et al. Systems pharmacology uncover the mechanism of anti-non-small cell lung cancer for Hedyotis diffusa Willd. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2019;109:969–984. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang J., Zhang L., Liu B., et al. Systematic investigation of the Erigeron breviscapus mechanism for treating cerebrovascular disease. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2018;224:429–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu J., Liu J., Shen F., et al. Systems pharmacology analysis of synergy of TCM: an example using saffron formula. Scientific Reports. 2018;8(1):p. 380. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18764-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu J., Zhu J., Xue J., et al. In silico-based screen synergistic drug combinations from herb medicines: a case using Cistanche tubulosa. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1):p. 16364. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16571-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu J., Pei T., Mu J., et al. Systems pharmacology uncovers the multiple mechanisms of xijiao dihuang decoction for the treatment of viral hemorrhagic fever. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2016;2016:17. doi: 10.1155/2016/9025036.9025036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu F., Han B., Kumar P., et al. Update of TTD: therapeutic target database. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;38:D787–D791. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Safran M., Dalah I., Alexander J., et al. GeneCards Version 3: the human gene integrator. Database. 2010;2010:p. baq020. doi: 10.1093/database/baq020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Davis A. P., Grondin C. J., Johnson R. J., et al. The comparative Toxicogenomics database: update 2019. Nucleic Acids Research. 2019;47(D1):D948–D954. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pinero J., Bravo A., Queralt-Rosinach N., et al. DisGeNET: a comprehensive platform integrating information on human disease-associated genes and variants. Nucleic Acids Research. 2017;45(D1):D833–D839. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yu W., Gwinn M., Clyne M., Yesupriya A., Khoury M. J. A navigator for human genome epidemiology. Nature Genetics. 2008;40(2):124–125. doi: 10.1038/ng0208-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Amberger J. S., Bocchini C. A., Schiettecatte F., Scott A. F., Hamosh A. OMIM.org: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM(R)), an online catalog of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;43:D789–D798. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Whirl-Carrillo M., McDonagh E. M., Hebert J. M., et al. Pharmacogenomics knowledge for personalized medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92(4):414–417. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wishart D. S., Feunang Y. D., Guo A. C., et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Research. 2017;46(D1):D1074–D1082. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Szklarczyk D., Gable A. L., Lyon D., et al. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Research. 2019;47(D1):D607–D613. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Research. 2003;13(11):2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barabasi A. L., Oltvai Z. N. Network biology: understanding the cell’s functional organization. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2004;5(2):101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrg1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Raudvere U., Kolberg L., Kuzmin I., et al. Nucleic Acids Research. Vol. 47. W1: 2019. g:Profiler: a web server for functional enrichment analysis and conversions of gene lists (2019 update) pp. W191–W198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kanehisa M., Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28(1):27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cho D. Y., Kim Y. A., Przytycka T. M. Chapter 5: network biology approach to complex diseases. PLoS Computational Biology. 2012;8(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002820.e1002820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jeong H., Mason S. P., Barabasi A. L., Oltvai Z. N. Lethality and centrality in protein networks. Nature. 2001;411(6833):41–42. doi: 10.1038/35075138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhu J., Yi X., Zhang Y., Pan Z., Zhong L., Huang P. Systems pharmacology-based approach to comparatively study the independent and synergistic mechanisms of danhong injection and naoxintong capsule in ischemic stroke treatment. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2010;2019:17. doi: 10.1155/2019/1056708.1056708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhong J., Liu Z., Zhou X., Xu J. Synergic anti-pruritus mechanisms of action for the radix sophorae flavescentis and fructus cnidii herbal pair. Molecules. 2017;22:9. doi: 10.3390/molecules22091465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Miller L. D., Smeds J., George J., et al. An expression signature for p53 status in human breast cancer predicts mutation status, transcriptional effects, and patient survival. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(38):13550–13555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506230102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yang P., Du C. W., Kwan M., Liang S. X., Zhang G. J. The impact of p53 in predicting clinical outcome of breast cancer patients with visceral metastasis. Scientific Reports. 2020;3:p. 2246. doi: 10.1038/srep02246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wellenstein M. D., Coffelt S. B., Duits D. E. M., et al. Loss of p53 triggers WNT-dependent systemic inflammation to drive breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2019;572(7770):538–542. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1450-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lim L. Y., Vidnovic N., Ellisen L. W., Leong C. O. Mutant p53 mediates survival of breast cancer cells. British Journal of Cancer. 2009;101(9):1606–1612. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lacroix M., Toillon R. A., Leclercq G. p53 and breast cancer, an update. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2006;13(2):293–325. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yamashita H., Toyama T., Nishio M., et al. p53 protein accumulation predicts resistance to endocrine therapy and decreased post-relapse survival in metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research. 2006;8(4):p. R48. doi: 10.1186/bcr1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Walerych D., Napoli M., Collavin L., Del Sal G. The rebel angel: mutant p53 as the driving oncogene in breast cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33(11):2007–2017. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Turner N., Moretti E., Siclari O., et al. Targeting triple negative breast cancer: is p53 the answer? Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2013;39(5):541–550. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Na B., Yu X., Withers T., et al. Therapeutic targeting of BRCA1 and TP53 mutant breast cancer through mutant p53 reactivation. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2019;5:p. 14. doi: 10.1038/s41523-019-0110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mayer E. L., Krop I. E. Advances in targeting SRC in the treatment of breast cancer and other solid malignancies. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16(14):3526–3532. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hiscox S., Morgan L., Green T. P., Barrow D., Gee J., Nicholson R. I. Elevated Src activity promotes cellular invasion and motility in tamoxifen resistant breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2006;97(3):263–274. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang X. H., Wang Q., Gerald W., et al. Latent bone metastasis in breast cancer tied to Src-dependent survival signals. Cancer Cell. 2009;16(1):67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Saad F., Lipton A. SRC kinase inhibition: targeting bone metastases and tumor growth in prostate and breast cancer. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2010;36(2):177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jallal H., Valentino M. L., Chen G., Boschelli F., Ali S., Rabbani S. A. A Src/Abl kinase inhibitor, SKI-606, blocks breast cancer invasion, growth, and metastasis in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Research. 2007;67(4):1580–1588. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Elsberger B., Fullerton R., Zino S., et al. Breast cancer patients’ clinical outcome measures are associated with Src kinase family member expression. British Journal of Cancer. 2010;103(6):899–909. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Verbeek B. S., Vroom T. M., Adriaansen-Slot S. S., et al. c-Src protein expression is increased in human breast cancer. An immunohistochemical and biochemical analysis. The Journal of Pathology. 1996;180(4):383–388. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199612)180:4<383::AID-PATH686>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yang Y., Li M., Li Y. High expression of PIK3R1 (p85α) correlates with poor survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Int Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology. 9(12):12797–12806. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Burstein H. J., Chen Y. H., Parker L. M., et al. VEGF as a marker for outcome among advanced breast cancer patients receiving anti-VEGF therapy with bevacizumab and vinorelbine chemotherapy. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;14(23):7871–7877. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liang Y., Brekken R. A., Hyder S. M. Vascular endothelial growth factor induces proliferation of breast cancer cells and inhibits the anti-proliferative activity of anti-hormones. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2006;13(3):905–919. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Luo M., Hou L., Li J., et al. VEGF/NRP-1axis promotes progression of breast cancer via enhancement of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and activation of NF-kappaB and beta-catenin. Cancer Letters. 2016;373(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Perrot-Applanat M., Di Benedetto M. Autocrine functions of VEGF in breast tumor cells: adhesion, survival, migration and invasion. Cell Adhesion & Migration. 2012;6(6):547–553. doi: 10.4161/cam.23332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Vestey S. B., Sen C., Calder C. J., Perks C. M., Pignatelli M., Winters Z. E. Activated Akt expression in breast cancer: correlation with p53, Hdm2 and patient outcome. European Journal of Cancer. 2005;41(7):1017–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Perez-Tenorio G., Stal O., Southeast Sweden Breast Cancer G. Activation of AKT/PKB in breast cancer predicts a worse outcome among endocrine treated patients. British Journal of Cancer. 2002;86(4):540–545. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kirkegaard T., Witton C. J., McGlynn L. M., et al. AKT activation predicts outcome in breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen. The Journal of Pathology. 2005;207(2):139–146. doi: 10.1002/path.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Grell P., Fabian P., Khoylou M., et al. Akt expression and compartmentalization in prediction of clinical outcome in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer patients treated with trastuzumab. International Journal of Oncology. 2012;41(4):1204–1212. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tokunaga E., Kataoka A., Kimura Y., et al. The association between Akt activation and resistance to hormone therapy in metastatic breast cancer. European Journal of Cancer. 2006;42(5):629–635. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Vleugel M. M., Greijer A. E., Bos R., van der Wall E., van Diest P. J. c-Jun activation is associated with proliferation and angiogenesis in invasive breast cancer. Human Pathology. 2006;37(6):668–674. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jiao X., Katiyar S., Willmarth N. E., et al. c-Jun induces mammary epithelial cellular invasion and breast cancer stem cell expansion. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(11):8218–8226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.100792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhang Y., Pu X., Shi M., et al. c-Jun, a crucial molecule in metastasis of breast cancer and potential target for biotherapy. Oncology Reports. 2007;18(5):1207–1212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhang Y., Pu X., Shi M., et al. Critical role of c-Jun overexpression in liver metastasis of human breast cancer xenograft model. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:p. 145. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Teschendorff A. E., Li L., Yang Z. Denoising perturbation signatures reveal an actionable AKT-signaling gene module underlying a poor clinical outcome in endocrine-treated ER+ breast cancer. Genome Biology. 2015;16:p. 61. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0630-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Davis N. M., Sokolosky M., Stadelman K., et al. Deregulation of the EGFR/PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTORC1 pathway in breast cancer: possibilities for therapeutic intervention. Oncotarget. 2014;5(13):4603–4650. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nogi H., Kobayashi T., Suzuki M., et al. EGFR as paradoxical predictor of chemosensitivity and outcome among triple-negative breast cancer. Oncology Reports. 2009;21(2):413–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Liu D., He J., Yuan Z., et al. EGFR expression correlates with decreased disease-free survival in triple-negative breast cancer: a retrospective analysis based on a tissue microarray. Medical Oncology. 2012;29(2):401–405. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-9827-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lim S. O., Li C. W., Xia W., et al. EGFR signaling enhances aerobic glycolysis in triple-negative breast cancer cells to promote tumor growth and immune escape. Cancer Research. 2016;76(5):1284–1296. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Mueller K. L., Powell K., Madden J. M., Eblen S. T., Boerner J. L. EGFR tyrosine 845 phosphorylation-dependent proliferation and transformation of breast cancer cells require activation of p38 MAPK. Translational Oncology. 2012;5(5):327–334. doi: 10.1593/tlo.12163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Dihge L., Bendahl P. O., Grabau D., et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and the estrogen receptor modulator amplified in breast cancer (AIB1) for predicting clinical outcome after adjuvant tamoxifen in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2008;109(2):255–262. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9645-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Park H. S., Jang M. H., Kim E. J., et al. High EGFR gene copy number predicts poor outcome in triple-negative breast cancer. Modern Pathology. 27(9):1212–1222. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ghayad S. E., Cohen P. A. Inhibitors of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway: new hope for breast cancer patients. Recent Patents on Anti-Cancer Drug Discovery. 5(1):29–57. doi: 10.2174/157489210789702208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Langer S., Singer C. F., Hudelist G., et al. Jun and Fos family protein expression in human breast cancer: correlation of protein expression and clinicopathological parameters. European Journal of Gynaecological Oncology. 2014;27(4):345–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Yan X. L., Fu C. J., Chen L., et al. Mesenchymal stem cells from primary breast cancer tissue promote cancer proliferation and enhance mammosphere formation partially via EGF/EGFR/Akt pathway. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2012;132(1):153–164. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1577-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Verbeek B. S., Adriaansen-Slot S. S., Vroom T. M., Beckers T., Rijksen G. Overexpression of EGFR and c-erbB2 causes enhanced cell migration in human breast cancer cells and NIH3T3 fibroblasts. FEBS Letters. 1998;425(1):145–150. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Castaneda C. A., Cortes-Funes H., Gomez H. L., Ciruelos E. M. The phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase/AKT signaling pathway in breast cancer. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2010;29(4):751–759. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9261-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kallergi G., Agelaki S., Kalykaki A., Stournaras C., Mavroudis D., Georgoulias V. Phosphorylated EGFR and PI3K/Akt signaling kinases are expressed in circulating tumor cells of breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Research. 10(5):p. R80. doi: 10.1186/bcr2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Paplomata E., O’Regan R. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in breast cancer: targets, trials and biomarkers. Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology. 2008;6(4):154–166. doi: 10.1177/1758834014530023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Saini K. S., Loi S., de Azambuja E., et al. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and Raf/MEK/ERK pathways in the treatment of breast cancer. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2013;39(8):935–946. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Briggs J., Chamboredon S., Castellazzi M., Kerry J. A., Bos T. J. Transcriptional upregulation of SPARC, in response to c-Jun overexpression, contributes to increased motility and invasion of MCF7 breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2002;21(46):7077–7091. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Jordan N. J., Gee J. M., Barrow D., Wakeling A. E., Nicholson R. I. Increased constitutive activity of PKB/Akt in tamoxifen resistant breast cancer MCF-7 cells. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2004;87(2):167–180. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000041623.21338.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Albert J. M., Kim K. W., Cao C., Lu B. Targeting the Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway for radiosensitization of breast cancer. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2006;5(5):1183–1189. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Liang K., Jin W., Knuefermann C., et al. Targeting the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway for enhancing breast cancer cells to radiotherapy. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2003;2(4):353–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Lee J. J., Loh K., Yap Y. S. PI3K/Akt/mTOR inhibitors in breast cancer. Cancer Biology & Medicine. 2015;12(4):342–354. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2015.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Rodriguez M., Potter D. A. CYP1A1 regulates breast cancer proliferation and survival. Molecular Cancer Research. 2013;11(7):780–792. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Huang Y., Trentham-Dietz A., Garcia-Closas M., et al. Association of CYP1B1 haplotypes and breast cancer risk in Caucasian women. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2009;18(4):1321–1323. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Huang C. S., Chern H. D., Chang K. J., Cheng C. W., Hsu S. M., Shen C. Y. Breast cancer risk associated with genotype polymorphism of the estrogen-metabolizing genes CYP17, CYP1A1, and COMT: a multigenic study on cancer susceptibility. Cancer Research. 1999;59(19):4870–4875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Mitra R., Guo Z., Milani M., et al. CYP3A4 mediates growth of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells in part by inducing nuclear translocation of phospho-Stat3 through biosynthesis of (+/-)-14,15-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid (EET) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286(20):17543–17559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.198515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Napoli N., Villareal D. T., Mumm S., et al. Effect of CYP1A1 gene polymorphisms on estrogen metabolism and bone density. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2005;20(2):232–239. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Yu A. M., Fukamachi K., Krausz K. W., Cheung C., Gonzalez F. J. Potential role for human cytochrome P450 3A4 in estradiol homeostasis. Endocrinology. 2005;146(7):2911–2919. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Cheng Z. N., Shu Y., Liu Z. Q., Wang L. S., Ou-Yang D. S., Zhou H. H. Role of cytochrome P450 in estradiol metabolism in vitro. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2001;22(2):148–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Taioli E., Bradlow H. L., Garbers S. V., et al. Role of estradiol metabolism and CYP1A1 polymorphisms in breast cancer risk. Cancer Detection and Prevention. 1999;23(3):232–237. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1500.1999.09912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Zhou X., Qiao G., Wang X., et al. CYP1A1 genetic polymorphism is a promising predictor to improve chemotherapy effects in patients with metastatic breast cancer treated with docetaxel plus thiotepa vs. docetaxel plus capecitabine. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2018;81(2):365–372. doi: 10.1007/s00280-017-3500-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Sakurai K., Enomoto K., Matsuo S., Amano S., Shiono M. CYP3A4 expression to predict treatment response to docetaxel for metastasis and recurrence of primary breast cancer. Surgery Today. 2011;41(5):674–679. doi: 10.1007/s00595-009-4328-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Izadi S., Nikkhoo A., Hojjat-Farsangi M., et al. CDK1 in breast cancer: implications for theranostic potential. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 2020;20(7):758–767. doi: 10.2174/1871520620666200203125712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Xia Q., Cai Y., Peng R., Wu G., Shi Y., Jiang W. The CDK1 inhibitor RO3306 improves the response of BRCA-pro fi cient breast cancer cells to PARP inhibition. International Journal of Oncology. 2014;44(3):735–744. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Kim S. J., Masuda N., Tsukamoto F., et al. The cell cycle profiling-risk score based on CDK1 and 2 predicts early recurrence in node-negative, hormone receptor-positive breast cancer treated with endocrine therapy. Cancer Letters. 2014;355(2):217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Kim S. J., Nakayama S., Miyoshi Y., et al. Determination of the specific activity of CDK1 and CDK2 as a novel prognostic indicator for early breast cancer. Annals of Oncology. 2008;19(1):68–72. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Nakayama S., Torikoshi Y., Takahashi T., et al. Prediction of paclitaxel sensitivity by CDK1 and CDK2 activity in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Research. 2009;11(1):p. R12. doi: 10.1186/bcr2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Kang J., Sergio C. M., Sutherland R. L., Musgrove E. A. Targeting cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) but not CDK4/6 or CDK2 is selectively lethal to MYC-dependent human breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:p. 32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Yue S. J., Liu J., Feng W. W., et al. System pharmacology-based dissection of the synergistic mechanism of huangqi and huanglian for diabetes mellitus. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2017;8:p. 694. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Kolch W., Halasz M., Granovskaya M., Kholodenko B. N. The dynamic control of signal transduction networks in cancer cells. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2015;15(9):515–527. doi: 10.1038/nrc3983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Hardy K. M., Booth B. W., Hendrix M. J., Salomon D. S., Strizzi L. ErbB/EGF signaling and EMT in mammary development and breast cancer. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 2010;15(2):191–199. doi: 10.1007/s10911-010-9172-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Luo M., Guan J. L. Focal adhesion kinase: a prominent determinant in breast cancer initiation, progression and metastasis. Cancer Letters. 2010;289(2):127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Bullock M. FOXO factors and breast cancer: outfoxing endocrine resistance. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2016;23(2):R113–R130. doi: 10.1530/ERC-15-0461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Farhan M., Wang H., Gaur U., Little P. J., Xu J., Zheng W. FOXO signaling pathways as therapeutic targets in cancer. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2017;13(7):815–827. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.20052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Li T., Sparano J. A. Inhibiting Ras signaling in the therapy of breast cancer. Clinical Breast Cancer. 2003;3(6):405–416. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2003.n.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Angelini P. D., Zacarias Fluck M. F., Pedersen K., et al. Constitutive HER2 signaling promotes breast cancer metastasis through cellular senescence. Cancer Res. 2013;73(1):450–458. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Lipponen P. Apoptosis in breast cancer: relationship with other pathological parameters. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 1999;6(1):13–16. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0060013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Pare R., Yang T., Shin J. S., Lee C. S. The significance of the senescence pathway in breast cancer progression. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2013;66(6):491–495. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2012-201081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Parton M., Dowsett M., Smith I. Studies of apoptosis in breast cancer. BMJ. 2001;322(7301):1528–1532. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7301.1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Roy P. G., Thompson A. M. Cyclin D1 and breast cancer. Breast. 1998;15(6):718–727. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Sutherland R. L., Musgrove E. A. Cyclins and breast cancer. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 2004;9(1):95–104. doi: 10.1023/B:JOMG.0000023591.45568.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Goldberg J. E., Schwertfeger K. L. Proinflammatory cytokines in breast cancer: mechanisms of action and potential targets for therapeutics. Current Cancer Drug Targets. 2010;11(9):1133–1146. doi: 10.2174/138945010792006799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Mercogliano M. F., Bruni S., Elizalde P. V., Schillaci R. Tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade: an opportunity to tackle breast cancer. Frontiers in Oncology. 2020;10:p. 584. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Hayashi S., Niwa T., Yamaguchi Y. Estrogen signaling pathway and its imaging in human breast cancer. Cancer Sciences. 2009;100(10):1773–1778. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Nahta R., O’Regan R. M. Therapeutic implications of estrogen receptor signaling in HER2-positive breast cancers. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2012;135(1):39–48. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Renoir J. M., Marsaud V., Lazennec G. Estrogen receptor signaling as a target for novel breast cancer therapeutics. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2013;85(4):449–465. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Saha Roy S., Vadlamudi R. K. Role of estrogen receptor signaling in breast cancer metastasis. International Journal of Breast Cancer. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/654698.654698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Saha T., Makar S., Swetha R., Gutti G., Singh S. K. Estrogen signaling: an emanating therapeutic target for breast cancer treatment. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2019;177:116–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Andrieu G. P., Shafran J. S., Smith C. L., et al. BET protein targeting suppresses the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway in triple-negative breast cancer and elicits anti-tumor immune response. Cancer Letters. 2019;465:45–58. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Chretien S., Zerdes I., Bergh J., Matikas A., Foukakis T. Beyond PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition: what the future holds for breast cancer immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:5. doi: 10.3390/cancers11050628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Guo Y., Yu P., Liu Z., et al. Prognostic and clinicopathological value of programmed death ligand-1 in breast cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156323.e0156323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Jing X., Shao S., Zhang Y., et al. BRD4 inhibition suppresses PD-L1 expression in triple-negative breast cancer. Experimental Cell Research. 2010;392(2) doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2020.112034.112034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Muenst S., Schaerli A. R., Gao F., et al. Expression of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) is associated with poor prognosis in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2014;146(1):15–24. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2988-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Jang G. B., Kim J. Y., Cho S. D., et al. Blockade of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling suppresses breast cancer metastasis by inhibiting CSC-like phenotype. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:p. 12465. doi: 10.1038/srep12465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]