Abstract

Post-exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) is an effective yet underutilized HIV prevention tool. PEPTALK developed and evaluated a media campaign to drive demand for PEP among men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women (TW) living in high HIV prevalence areas in New York City. Formative qualitative research (38 in-depth interviews and five focus groups [N=48]) with Black or African-American MSM or TW who reported condomless sex with a HIV-positive/unknown status man was conducted to inform campaign design. We assessed the impact of the campaign, 15 bus shelter ads and low or no-cost social media, by assessing change in the proportions of new PEP patient visits, to the clinical site where the campaign directed consumers, using one-sided z-test for proportions, before and after the media campaign. The proportion of new PEP patients increased significantly after the media campaign in the periods examined, suggesting that such campaigns may increase PEP demand.

Keywords: HIV prevention, PEP, men who have sex with men, media campaign, health communication

INTRODUCTION

Gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (henceforth MSM) constituted the largest proportion (83.5%) of new HIV diagnoses among men in the United States (US) in 2016, with marked disparities by race/ethnicity(1). Nationally in 2016, Latinx MSM comprised 24% and Black MSM 32% of all MSM living with HIV/AIDS, despite making up smaller proportions of the general population(1). New York City (NYC) is the metropolitan area with the largest number of newly diagnosed HIV infections among MSM(2). In NYC, 2,157 New Yorkers were newly diagnosed with HIV in 2017, down 5.4% from 2016(3); among MSM, there were 1,243 new HIV diagnoses, with 32% of all new cases among Black and 42% among Latinx MSM(4). Lower income areas, such as Upper Manhattan and the South Bronx, continue to be heavily burdened by new infections(4), consistent with national data(5). Despite a leveling off of new infections among MSM nationally, national and local efforts to prevent new infections are urgently needed.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued guidelines for clinical use of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) to prevent HIV infection over 15 years ago, based on animal and observational human data,(6-8) updating them most recently in 2016(9).Taken for 28 days to prevent infection after a high-risk exposure to HIV, PEP is underutilized by those who experience non-occupational exposure,(10-13) MSM in particular.(14-16) PEP is cost-effective and even cost-saving (17-19) and tolerability has improved in recent years.(16, 20) Preventing HIV acquisition through uptake of effective biomedical prevention methods, specifically pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and PEP, is a key component of the national Ending the Epidemic strategy(21). Importantly, the PEP treatment period offers opportunities for educating at risk MSM about prevention options, to promote uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Despite evidence that there is growing awareness of PEP among MSM and transwomen in the US, ranging from 60 to 80% among urban-dwelling MSM and transwomen (15, 22), there is still extremely limited uptake.(10) This suggests that there is a disconnect between awareness of this effective prevention method and recognition of what might trigger the need for PEP, as well as how to access it. PEPTALK was a study designed to evaluate the impact of a media campaign to increase uptake of PEP among MSM at risk of HIV infection. The study team conducted formative qualitative research to inform the development of the campaign, which was designed to reach African-American/Black MSM or TW living in Upper Manhattan or the Bronx, two high HIV prevalence areas in NYC, and to drive potential PEP users to a single, specific clinical site. The formative research explored concepts theorized to be related to demand for PEP, including core domains of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)(23) and Diffusion of Innovation (DOI)(24) theories. Here we describe the formative research, which explored theoretically-informed barriers and facilitators to PEP uptake, the resultant campaign. As well, we describe results of an analysis of the impact of the campaign on PEP visits to the clinical site where the campaign directed media consumers.

METHODS

In-depth Interview and Focus Group Sample

Recruitment for the formative phase of the study occurred between February and September 2017 and resulted in 38 in-depth interviews and five focus groups (N=48). The eligibility criteria for both were: 1) aged 18 or older; 2) assigned male at birth, regardless of gender identity; 3) self-identify as Black, African American, Caribbean Black, African Black or multiethnic Black; 4) report condomless insertive or receptive anal intercourse (including dipping) with a man in the last 6 months; 5) live in, work in or spend the majority of time in the Bronx or upper Manhattan; 5) able to read and respond in English; and 7) provide informed consent. Participants were recruited via social media platforms, geosocial networks that cater to MSM, LGBT community-based organizations and healthcare centers and word of mouth. Participants were ineligible if they were enrolled in another HIV-related research study. To provide appropriate contrasts, we conducted interviews with five participants who used PEP in the past 3 years. Eligible and willing participants were invited to the study’s site in upper Manhattan to engage in the research. Participants were provided a $50 in cash and a roundtrip transit fare card for their time and travel expenses. Most study visits took between 1½ and 2 hours. The research was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the City University of New York and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, and Montefiore Medical Center.

In-depth Interview and Focus Group Content, Method and Analysis

In-depth interviews (IDIs) and focus groups (FGs) were conducted by a PhD-level project director, trained by the Principal Investigator in qualitative interviewing and focus group facilitation. The IDIs focused on the first few steps of the PEP uptake process: exposure risk awareness, PEP awareness, and PEP access. To start, participants were asked to define what sexual health meant to them and where they seek and gain knowledge and care regarding their sex lives. Participants were asked to interpret the term “exposure” in terms of HIV and describe their knowledge of how an individual can contract HIV. Participants were then asked about what they may have “heard” about PEP. Lastly, participants are asked about how they would navigate PEP access and uptake. For previous PEP users, we discussed their experiences with access and adherence. PEP characteristics theorized to be relevant to uptake were explored using constructs from Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) theory(24), including relative advantage (i.e., superiority to existing or alternative HIV prevention options), compatibility (i.e., how PEP, as a medication, fits into a potential users lifestyle), complexity (i.e., how complicated are the medication regimen and visit schedule), trialability (i.e., whether PEP can be tested out or adapted as needed) and observability (i.e., whether PEP can be perceived to “work”). Key TPB domains(23), including attitudes towards medication use, medical mistrust, subjective norms, and self-efficacy, were also explored. Thematic analysis, applying the framework approach, was conducted including basic coding of the data, organization of codes into themes and discussion among study team members(25). The first author (JF) conducted all IDIs, which were digitally recorded and professionally transcribed, and coded the data using broad domains covered in the interview guide. Three key study team members (JF, VF & BZ) read each transcript and reviewed select coded content to identify key themes. To inform design of the media campaign, we visually depicted the themes identified with key supporting quotes from the data (see Graphics) and conducted a series of meetings with study team members and key consultants, which generated potential campaign messaging and imagery ideas. The FGs were used to test the possible media messages and images that were developed through this process. Here, an abbreviated set of topical areas were explored, followed by the presentation of mock-ups of potential messages and advertisements. Feedback was used to adjust the messages and images selected. In both the IDIs and FGs, we explored the influence of subjective norms on participants’ responses to and perceptions of PEP, as potential barriers to access and uptake.

Media Campaign and Impact Analysis

The media campaign included 15 bus shelter ads in locations selected by the study team and the vendor in Upper Manhattan and the Bronx. The bus shelter ads began in mid-September 2018 and continued until mid-October 2018; the period was extended for seven of the sites until mid-November. In addition, some ran for longer periods due to lack of demand for the bus shelter location from other potential advertisers. In addition, a social media campaign was launched that included targeted ads on Facebook and low or no-cost distribution via social network contacts, friendly community-based organizations and word-of-mouth on social media. Thus, during the period 17 different posts were made on Facebook and a single paid Facebook ad occurred in mid- November. The posts focused on educational information on PEP as HIV prevention, for example when PEP should be sought and how to seek it. Specific PEP access points, described below, were identified in ads and all posts. The posts were posted on different days of the week and at different times; the average impression across posts was 87.2. A website was developed as a landing pad for individuals who received social media messages or viewed the bus shelter ads, which displayed the website address (PEPTALK.NYC), the clinical site’s phone number, the NYC PEP Hotline toll-free telephone number and a scannable “quick response” (QR) code that directed viewers to the PEPTALK.NYC website. The ads and posts were designed to drive demand for PEP and to direct individuals to The Oval Center, a comprehensive sexual health clinic affiliated with the Montefiore AIDS Center, which provides sexual health services, HIV testing, PEP and PrEP services, etc. and is located in the Bronx. Data related to call volume to the NYC PEP hotline could not be obtained, but an average of 10 new and unique webpage visitors were reported each week during the study period. Further, an average of 4 new PEP patients were seen each week during the study period.

To evaluate the impact of these media efforts on PEP uptake at the clinical site, we compared the rate of new PEP patients, who self-reported male sex at birth and any sexual identity that was not heterosexual, out of all new clinic visits using a one-sided z-test for proportion (p ≤ 0.05) and three periods of comparison. The first compared the 7-month period from November 2017 to May 2018 to the 7-month period from November 2018 to May 2019. The second compared the 5-month period from January 2018 to May 2018 to the 5-month period the following year, January 2019 to May 2019. Finally, we compared January 2018 to August 2018, the eight months immediately prior to the first month of the ad campaign (September 2018), to October 2018 to May 2019, the eight months immediately after the campaign. We selected these three periods to address different potential biases. The first period selected compared the seven months from the last month of the campaign (November 2018) through the spring (May 2019), but not including the summer, to the same period the year prior (2017-18). The summer months were excluded because it can be a period of higher levels of sexual activity. The second period selected allowed us to assess a potential lagged effect of the ads by comparing a period starting a full month after the ads stopped (January 2019 to May 2019) to the same period the year before, which also help address the impact of seasonal trends in sexual activity, which may be related to opportunity (26-28). Finally, by assessing the third selected period, the eight months immediately before the ad campaign to the eight months immediately after the campaign, we capture the immediate impact of the campaign, although we ignore the potential impact of seasonal variation in sexual activity. All periods end in May 2019, the end of the grant period. Analyses were done in SAS 9.4® and IBM® SPSS® 24.

RESULTS

Formative Research Sample

Formative research participants (38 in-depth interviews and five focus groups [N=48]) ranged in age from 18 to 52. Across all participants, 94% self-identified as male; 5% as female and 1% as transgender female. (All participants were assigned male sex at birth.) Of IDI participants, 77% self-identified as African-American or Black and 18% self-identified as Black or African American and Latinx; 5% identified as African-American or Black and another category. The average age of IDI participants (N=38) was 28.2 (sd=7.8) and the mean age of focus group participants was 30 (sd=9.7). Of FG participants (N=48), 70% self-identified as African-American or Black and 22% self-identified as Black or African American and Latinx; 9% identified as African-American or Black and another category. In terms of sexual orientation, across both IDIs and FGs, 40% identified as gay; 39% as bisexual; 13% as straight; 5% as straight and has sex with transgender women; and the remained (3%) declined to answer or wrote in “confused.”

Formative Research Themes

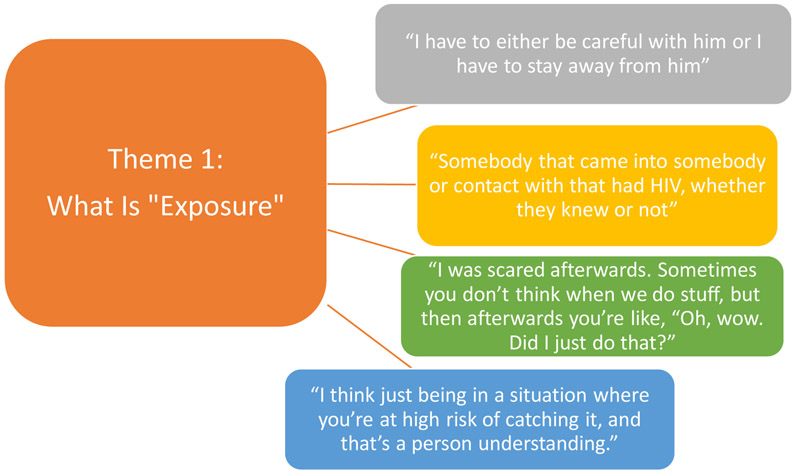

We identified three themes in the IDI and FG data most relevant to the development of the media campaign. The first theme reflected risk awareness and perception of the term “exposure;” the second emerged around PEP knowledge and credibility. The final theme reflected feedback on messaging and imagery related to the proposed media campaign. In terms of the first theme, most participants were able to describe situations (got drunk and had condomless sex) or experiences (condom broke with HIV-positive partner) that placed them at risk for HIV acquisition, but were either unfamiliar with or uncomfortable with the word “exposure.” The word did not resonate with participants; further, they reported that it made them feel threatened. To communicate what clinicians conceptualize as exposure without triggering feelings of fear, we identified the inputs clinicians use to label an exposure via examples provided by participants. Such phrases as “condom broke?” were identified as preferable ways to attract a viewer’s attention to a potential exposure (Graphic 1). In terms of PEP knowledge, we identified some lack of knowledge of biomedical HIV prevention tools. Although most participants had seen ads on subways and buses for PrEP, several did not know what exactly was being advertised. Others were familiar with PrEP, but had no idea that PEP existed; they wondered how long PEP has been available and why it was not more widely available. Participants who knew about PEP had learned about it from their friends or acquaintances and/or health care providers. When asked who in general knew about PEP, several noted that it was known in the gay or trans communities; however, unlike PrEP, PEP was not a major topic of discussion. Some participants described skepticism about PEP, wondering why they had not heard of it, if it was so effective, as well as whether it actually works. Others were skeptical because it did not address STIs other than HIV or due to concerns around so-called risk compensation (Graphic 2). These negative attitudes may reflect a more generalized medical mistrust based in historical and current mistreatment and violence against people of color by the health care system and care providers(29, 30).

Graphic 1.

Formative Research Theme 1: What is Exposure?

Graphic 2.

Formative Research Theme 2: PEP Awareness, Knowledge and Credibility

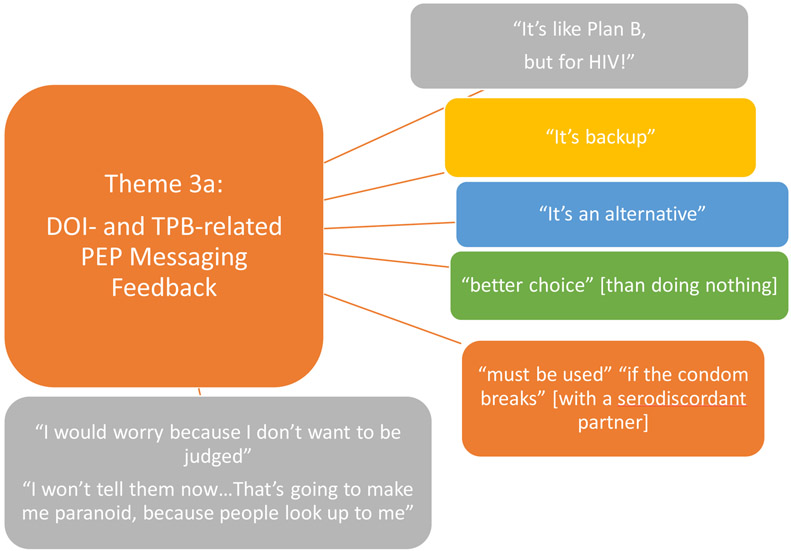

In the IDIs, we explored how PEP was perceived in terms of “relative advantage” one of the core concepts of the DOI theory, reflecting whether and how the novel prevention method is superior to an existing or currently used prevention method, and that is relevant to messaging to viewers new to PEP. We found that few participants imagined using PEP as a primary form of HIV prevention, suggesting that it was not perceived as superior to current methods, but that it was seen as a good back-up method and a better choice than doing nothing after an exposure. Its utility in the case of condom breakage was noted by several participants, although cost and access were concerns. In terms of the DOI-based concepts, “observability” (being able to see the drug working, for example feeling better after feeling unwell) and “trialability” (being able to start and stop the medication), some participants stated that not being able to observe the effects of the drug would make them “uncomfortable” or that they would "go crazy” due to this. Most said that if provided the option, they would seek out PEP if they knew that they had been exposed, even if they could not stop and start. Importantly, however, some noted that they would be concerned that others would find out that they were on PEP. Here the role of subjective norms, a key component of the TPB reflecting an individual’s beliefs about how others perceive the action in this case medication, emerged as a potential barrier to PEP uptake (Graphic 3a).

Graphic 3a.

Formative Research Theme 3: Messaging Feedback

Media Campaign Design

The overarching goal of our media campaign was to drive demand for PEP by informing and motivating people who could benefit from PEP to access it. Thus, we sought to raise awareness of the existence of PEP, and communicate knowledge around the time-dependent nature of it (must start within 72 hours of exposure) and its benefit if accessed (can prevent infection). To inform the design of the media campaign, we identified themes most relevant to messaging, particularly how to communicate what an exposure is, as well as the limitations of PEP as a method. We developed a matrix that arrayed our themes and brainstormed messages that reflect the themes, specifically the reflections of participants themselves. For example, the interview responses to our IDI questions about defining exposures revealed significant use of feelings of anxiety to gauge risk of infection in the days after condomless sex with a status unknown partner. This resulted in attention-grabbing messages that reflected feelings of anxiety. For the awareness, knowledge and credibility theme, we noted that many participants were PrEP aware, thus we designed messages to leverage that knowledge to communicate the existence of PEP.

Next, we conducted focus groups, after these messages based on the IDIs were developed, to explore ways of presenting visually or verbally a “call to action” that a potential exposure to HIV could constitute. Because the term “exposure” was received negatively by most participants, we offered a range of potential options including:

Hit It Raw?

$#!+ Happens, Get PEP

PEP, it’s like PLAN B but for HIV!

Condom broke, what’s you Plan B?

Protect Yourself, We Got You

You’ve heard of PrEP…but have you heard of PEP?

Worried about last night's session? If taken within 72 hours, Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) can keep you HIV negative.

Feedback indicated that “Hit It Raw?” was experienced as potentially stigmatizing and thus failed to connect with participants. “We Got You” was seen as supportive, but vague. Contrary to our notion that the awareness around PrEP could be leveraged for PEP, the use of PrEP was seen as contributing to confusion between the two prevention methods. “Plan B for HIV” was very well-received and comprehensible to most participants; participants indicated that it was familiar and immediately recognizable. It seemed to hold a certain meaning as well for participants, particularly as it reflected the IDI results around PEP as an important back-up option, but not the front-line of prevention. In addition, it communicated critical information of the window period for taking the medication more quickly that wordier approaches.

In terms of the images presented, we offered a range of images of men and transwomen of color as well as some graphics-only options. The concerns that emerged in the IDIs around why PEP is being marketed to Black MSM and other people of color were raised again in the groups.

Participants reported fatigue regarding images of people of color paired with messaging around HIV care and prevention. Participants reported that if images had to be used on publicity, they must be diverse in terms of race/ethnicity and sex/gender (Graphic 3b). Finally, in terms of preferences around the amount and type of font and graphics, participants reported that the messaging must be easily digestible, using simple language; video game-referencing font was well-received, as were clean, bright colors. The graphics used in the final posters, of the neon broken condom, clock face and shield, were seen as communicating exposure triggers and key intervention elements (72-hour window; protection from infection). (Graphics 4&5)

Graphic 3b.

Formative Research Theme 3: Messaging Feedback

Graphic 4.

Final PEPTALK Bus Shelter Ad Clockface

Graphic 5.

Final PEPTALK Bus Shelter Ad Shield

Pre- and Post-Media Campaign Impact Results

The results of the one-sided z-test for proportion is presented in Table 1. In the 8 months preceding the start of the bus shelter campaign (January 2018-August 2018), there were 49 (13.4%) new PEP visits out of 365 new visits vs. 66 (18.7%) new PEP visits out of 353 new visits in the 8 months following the start of the bus shelter campaign (October 2018-May 2019) (p=0.03). For seasonal comparison, there were 43 new PEP visits out of 332 new visits from November 2017 to May 2018, as compared with 53 new PEP visits out of 294 new visits from November 2017 to May 2018 (p=0.04). Finally, there were 28 new PEP visits out of 231 new visits from January 2018 to May 2018, as compared to 41 new PEP visits out of 227 new visits from January 2019 to May 2019 (p=0.04).

Table I.

Number and proportion of new PEP visits

| Bus Shelter Ad Period | Before | After | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Jan 2018-Aug 2018 | Oct 2018-May 2019 | |

| Total New visits | 365 | 353 | |

| PEP Visits | 49 (13.4%) | 66 (18.7%) | 0.03 |

| Period | Nov 2017-May 2018 | Nov 2018-May 2019 | |

| Total New visits | 332 | 294 | |

| PEP Visits | 43 (13.0%) | 53 (18.0%) | 0.04 |

| Period | Jan 2018-May 2018 | Jan 2019-May 2019 | |

| Total New visits | 231 | 227 | |

| PEP Visits | 28(12.1%) | 48 (18.1%) | 0.04 |

DISCUSSION

Like the PrEP continuum(31), there is also a PEP continuum, beginning with PEP awareness and culminating in a confirmatory HIV test conducted 90 days after the initial clinical visit. To increase demand for PEP post-sexual contact exposure and reduce incidence, twin significant challenges must be addressed. The first is increasing awareness of PEP as an accessible, practical and effective biomedical HIV prevention method. Despite recent research indicating that PEP awareness among MSM and transwomen is relatively high in NYC(15), in our sample, a sizable portion of participants did not know what PEP was or thought it was not a method that they could readily access and use. Increasing demand thus requires increasing awareness in much the same way that health officials have increased awareness of PrEP and condom use in the past(32). Our research suggests that there is widespread PrEP awareness, most likely because of the significant and coordinated efforts by city and state health department. For example, the clinical site at the center of this campaign became a state-designated PEP Center of Excellence in July of 2016. As well, NYC promoted PEP via the “PlaySure” campaign begun in 2016(33). Despite these efforts, we found that PEP was not well-recognized in our sample and that communicating the notion of “exposure” or when to seek PEP was a challenge. Our research found that “Plan B for HIV” was a highly recognizable and meaningful tag line, or “hook,” which triggered an automatic, positive association with effective prevention of an unwanted result of a sexual experience. In contrast, efforts to link communicate the difference between PEP and PrEP were not well-received. Further research based in thoughtful application of communication science should be engaged to identify the best ways to capitalize on the growing awareness of and belief the usability and effectiveness of PrEP for HIV prevention(32, 34).

The second major challenge in driving demand for PEP is increasing recognition of when a sexual experience constitutes a potential “exposure” and increasing knowledge of when, where and how to access PEP. In our formative research, we found that the word exposure was not well-received and yet preventionists have a hard time explaining what we mean without using this clinical and potentially anxiety-provoking term. In our research, we identified the experiences that constituted potential exposures for those not on PrEP, including broken condoms, getting drunk or high and having condomless sex with someone of unknown status or viral load (if positive), and other scenarios, like condomless anonymous and/or group sex. Participants were turned off by texts and images that highlighted certain of these scenarios, noting that for a public, bus shelter-based, ad campaign, certain of these scenarios could further stigmatize gay and bisexual men, particularly if paired with images of men of color. Health departments may wish to consider grants to collectives of gay and bisexual men and transgender women of color to design and launch ad campaigns in closed, digital and other networks where concerns related to stigmatization in the public sphere may be lessened. PEPTALK intended to drive demand for PEP among MSM of color primarily; yet because of this message fatigue, images and text that appealed to a general audience were implemented. This may have limited our ability to decrease the racial disparity in PEP access, although we note that the bus shelter ads were placed in neighborhoods where Black and Latinx residents make up the majority.

Rigorous evaluations of media campaigns to improve public health are challenging and can rarely demonstrate causality(34). Our results suggest that a geographically-focused, public transportation- and social media-based media campaign may increase traffic to a specific clinical site for PEP access. However, there are important threats to this conclusion that must be acknowledged. First, it is important to note that there may be other factors that contributed to the increase in PEP access at the focal clinical site. The New York state health department updated guidance to clinicians on non-occupational PEP in May of 2018(35). In addition, the efforts to increase awareness and uptake of PrEP in NYC were significant(36) during the study period and could have contributed to increased awareness of and access to PEP(37). Data from NY state’s Ending the Epidemic dashboard indicates that PEP prescriptions to Medicaid recipients increased among men in NYC from 416 to 482 between January and December of 2017; by June 2018, the last period with published data, the number had increased to 556 city-wide (see here: http://etedashboardny.org/data/prevention/ pep-in-nys)(38). Finally, we were unable to ascertain where clinic patients learned about PEP unfortunately; had we been able to track that a stronger conclusion regarding the impact of the media campaign might have been made. Despite these limitations, this study contributes to the growing body of research on the impact of health communications around sexual health and HIV prevention.

CONCLUSION

PEP is an underutilized HIV prevention approach which, if initiated more often, could have numerous potential benefits, most importantly preventing incident HIV infection. Increasing demand for PEP via media campaigns that link patients to physical, clinical sites as well as hotlines is a crucial first step. Although a PEP patient’s initial contact with HIV care and prevention professionals focuses appropriately on immediate, this setting can also be harnessed to efficiently and effectively transition patients to PrEP. Further research is needed to evaluate how best to support such a transition. This is complicated by the fact that, among MSM who initiate PEP, attrition during follow-up has proven to be a challenge,(12, 16, 39). Adherence support programs that simultaneously integrate consideration of a transition to PrEP are also needed. PEP is an often- overlooked prevention alternative for MSM and TW and others; further research on how to increase and capitalize on existing awareness in order to increase uptake is needed. Media campaigns play a vital role in this, but on-going navigation and support is also required, particularly to support transition to PrEP.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to Drs. Victoria Frye and Barry Zingman (R21 AI122996-01; Contact PI: Frye). The authors thank the participants who engaged in the research and the Project ACHIEVE community advisory board members who offered initial input into the study design. We also thank Dr. Beryl Koblin, Mr. Dashawn Usher, and Ms. Dominique Jackson for their feedback on select results of the formative research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

REFERENCES

- 1.Estimated HIV Incidence and Prevalence in the United States 2010-2016 2019. [Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html.

- 2.HIV Surveillance Annual Report, 2017. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Blasio Administration Announces Historic Low for New HIV Diagnoses, Down 64 Percent Since Reporting Begain in 2001 [press release]. New York, NY, November 29, 2018. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.2018. HIV/AIDS Among Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM) in New York City, 2017 New York, NY: [Available from: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/dires/hiv-aids-in-msm.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prevention CfDCa. Social determinants of health among adults with diagnosed HIV infection, 2017. Part A: Census tract-level social determinants of health and diagnosed HIV infection—United States and Puerto Rico.. 2019 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.CDC. Management of possible sexual, injecting-drug-use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV, including considerations related to antiretroviral therapy. Public Health Service statement. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47(RR-17):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schechter M, Do Lago RF, Mendelsohn AB, Moreira RI, Moulton LH, Harrison LH, et al. Behavioral impact, acceptability, and HIV incidence among homosexual men with access to postexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;35(5):519–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardo DM, Culver DH, Ciesielski CA, Srivastava PU, Marcus R, Abiteboul D, et al. A case–control study of HIV seroconversion in health care workers after percutaneous exposure. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337(21):1485–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Updated Guidelines for Antiretroviral Postexposure Prophylaxis After Sexual, Injection Drug Use, or Other Nonoccupational Exposure to HIV-United States, 2016. Atlanta, Georgia2016 [updated May 23, 2018 Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/programresources/cdc-hiv-npep-guidelines.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Z, Zou H. P566 The uptake of non-occupational HIV postexposure prophylaxis among MSM: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu AY, Kittredge PV, Vittinghoff E, Raymond HF, Ahrens K, Matheson T, et al. Limited Knowledge and Use of HIV Post- and Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Among Gay and Bisexual Men. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;47(2):241–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shoptaw S, Rotheram-Fuller E, Landovitz RJ, Wang J, Moe A, Kanouse DE, et al. Nonoccupational post exposure prophylaxis as a biobehavioral HIV-prevention intervention. AIDS Care. 2008;20(3):376–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez AE, Castel AD, Parish CL, Willis S, Feaster DJ, Kharfen M, et al. HIV Medical Providers' Perceptions of the Use of Antiretroviral Therapy as Nonoccupational Postexposure Prophylaxis in 2 Major Metropolitan Areas. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2013;64 Supplement(1):S68–S79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donnell D, Mimiaga MJ, Mayer K, Chesney M, Koblin B, Coates T. Use of non-occupational postexposure prophylaxis does not lead to an increase in high risk sex behaviors in men who have sex with men participating in the EXPLORE trial. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(5):1182–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koblin BA, Usher D, Nandi V, Tieu H-V, Bravo E, Lucy D, et al. Post-exposure Prophylaxis Awareness, Knowledge, Access and Use Among Three Populations in New York City, 2016–17. AIDS and Behavior. 2018;22(8):2718–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jain S, Oldenburg CE, Mimiaga MJ, Mayer KH. Longitudinal Trends in HIV Nonoccupational Postexposure Prophylaxis Use at a Boston Community Health Center Between 1997 and 2013. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2015;68(1):97–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bassett IV, Freedberg KA, Walensky RP. Two drugs or three? Balancing efficacy, toxicity, and resistance in postexposure prophylaxis for occupational exposure to HIV. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2004;39(3):395–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinkerton SD, Martin JN, Roland ME, Katz MH, Coates TJ, Kahn JO. Cost-effectiveness of HIV postexposure prophylaxis following sexual or injection drug exposure in 96 metropolitan areas in the United States. AIDS. 2004;18(15):2065–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinkerton SD, Martin JN, Roland ME, Katz MH, Coates TJ, Kahn JO. Cost-effectiveness of postexposure prophylaxis after sexual or injection-drug exposure to human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(1):46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain S, Mayer KH. Practical guidance for nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV infection: an editorial review. AIDS. 2014;28(11):1545–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for the United States. Jama. 2019;321(9):844–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dolezal C, Frasca T, Giguere R, Ibitoye M, Cranston RD, Febo I, et al. Awareness of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is low but interest is high among men engaging in condomless anal sex with men in Boston, Pittsburgh, and San Juan. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2015;27(4):289–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ajzen I The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes. 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 3rd ed. ed. New York: :: Free Press; ;; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC medical research methodology. 2013;13(1):117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li B, Bi P, Chow EP, Donovan B, McNulty A, Ward A, et al. Seasonal variation in gonorrhoea incidence among men who have sex with men. Sexual health. 2016;13(6):589–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Markey PM, Markey CN. Seasonal variation in internet keyword searches: a proxy assessment of sex mating behaviors. Archives of sexual behavior. 2013;42(4):515–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wellings K, Macdowall W, Catchpole M, Goodrich J. Seasonal variations in sexual activity and their implications for sexual health promotion. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1999;92(2):60–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Philbin MM, Parker CM, Parker RG, Wilson PA, Garcia J, Hirsch JS. The promise of pre-exposure prophylaxis for black men who have sex with men: an ecological approach to attitudes, beliefs, and barriers. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2016;30(6):282–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cahill S, Taylor SW, Elsesser SA, Mena L, Hickson D, Mayer KH. Stigma, medical mistrust, and perceived racism may affect PrEP awareness and uptake in black compared to white gay and bisexual men in Jackson, Mississippi and Boston, Massachusetts. AIDS care. 2017;29(11):1351–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edelstein, Scanlin, Findlater, Salcuni, Daskalakis, Myers, editors. HIV Prevention Continuum among MSM, New York City, Spring 2016. 12th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Storey D, Seifert-Ahanda K, Andaluz A, Tsoi B, Matsuki JM, Cutler B. What is health communication and how does it affect the HIV/AIDS continuum of care? A brief primer and case study from New York City. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2014;66:S241–S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Myers J Building a Citywide Network for Prevention Navigation: Year One of New York City's PlaySure Network National HIV Prevention Conference; Atlanta, Georgia: NYC Health; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hornik RC. Introduction public health communication: Making sense of contradictory evidence Public health communication: Routledg; e; 2002. p. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- 35.PEP for Non-Occupational: Exposure to HIV (nPEP) New York2018 [Available from: https://www.hivguidelines.org/pep-for-hiv-prevention/non-occupational/_-_tab_0.

- 36.Myers JE, Edelstein ZR, Daskalakis DC, Gandhi AD, Misra K, Rivera AV, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis monitoring in New York City: A public health approach. American journal of public health. 2018;108(S4):S251–S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alcala C Improving Access to PEP in the City that Never Sleeps: PEP Centers of Exellence in NYC National HIV Prevention Conference; Atlanta, Georgia: New York City Department of Health PlaySure; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ending the Epidemic New York2018 [Available from: http://etedashboardny.org/data/prevention/pep-in-nys/.

- 39.Bogoch II, Scully EP, Zachary KC, Yawetz S, Mayer KH, Bell CM, et al. Patient Attrition Between the Emergency Department and Clinic Among Individuals Presenting for HIV Nonoccupational Postexposure Prophylaxis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2014;58(11):1618–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]