Abstract

Purpose:

We explored relationships between patient-provider communication quality (PPCQ) and three quality of life (QOL) domains among self-identified rural cancer survivors: social well-being, functional well-being, and physical well-being. We hypothesized that high PPCQ would be associated with greater social and functional well-being, but be less associated with physical well-being, due to different theoretical mechanisms.

Methods:

All data were derived from the 2017–2018 Illinois Rural Cancer Assessment (IRCA). To measure PPCQ and QOL domains, we respectively used a dichotomous measure from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey’s Experience Cancer care tool (high, low/medium) and continuous measures from the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G).

Results:

Our sample of 139 participants was largely female, non-Hispanic White, married, and economically advantaged. After adjusting for demographic and clinical variables, patients who reported high PPCQ exhibited greater social well-being (Std β= 0.20, 95% CI: 0.03, 0.35, p = 0.02) and functional well-being (Std. β= 0.20, 95% CI: 0.05, 0.35, p = 0.03) than patients with low/medium PPCQ. No association was observed between PPCQ and physical well-being (Std β= 0.06, 95% CI: −2.51, 0.21, p = 0.41). Sensitivity analyses found similar, albeit attenuated, patterns.

Conclusion:

Our findings aligned with our hypotheses. Future researchers should explore potential mechanisms underlying these differential associations. Specifically, PPCQ may be associated with social and functional well-being through interpersonal mechanisms, but may not be as associated with physical well-being due to multiple contextual factors rural survivors disproportionately face (e.g., limited healthcare access, economic hardship) and stronger associations with clinical factors.

Keywords: Cancer survivorship, patient-provider communication, quality of life

Introduction

The prevalence of cancer survivors (defined as the individuals who have been diagnosed with cancer at some point of their lives) [1], has dramatically increased over time [2]. Most cancer survivors are now able to live 5 years or more post diagnosis [3]. Some research has however indicated cancer mortality is declining more slowly in rural areas than urban areas, resulting in growing urban-rural disparities in survivorship [4, 5]. Urban-rural survival disparities are likely, in part, impacted by complex, dynamic urban-rural disparities in quality of life (QOL) and other intermediate post-diagnosis outcomes [6]. Inadequate patient-provider communication quality (PPCQ) is one potential, modifiable determinant, given its effects on QOL [7] and survival [8]. However, PPCQ may differ in its relationship with different domains of QOL, due to other contributing determinants of disparities. As a first step, this study explores how PPCQ is differentially associated with multiple QOL domains among self-identified rural cancer survivors. We define rurality in terms of self-identification, because this is especially useful when focusing on social factors like PPCQ, for which social perceptions may be influenced by self-identity and cultural perceptions [9].

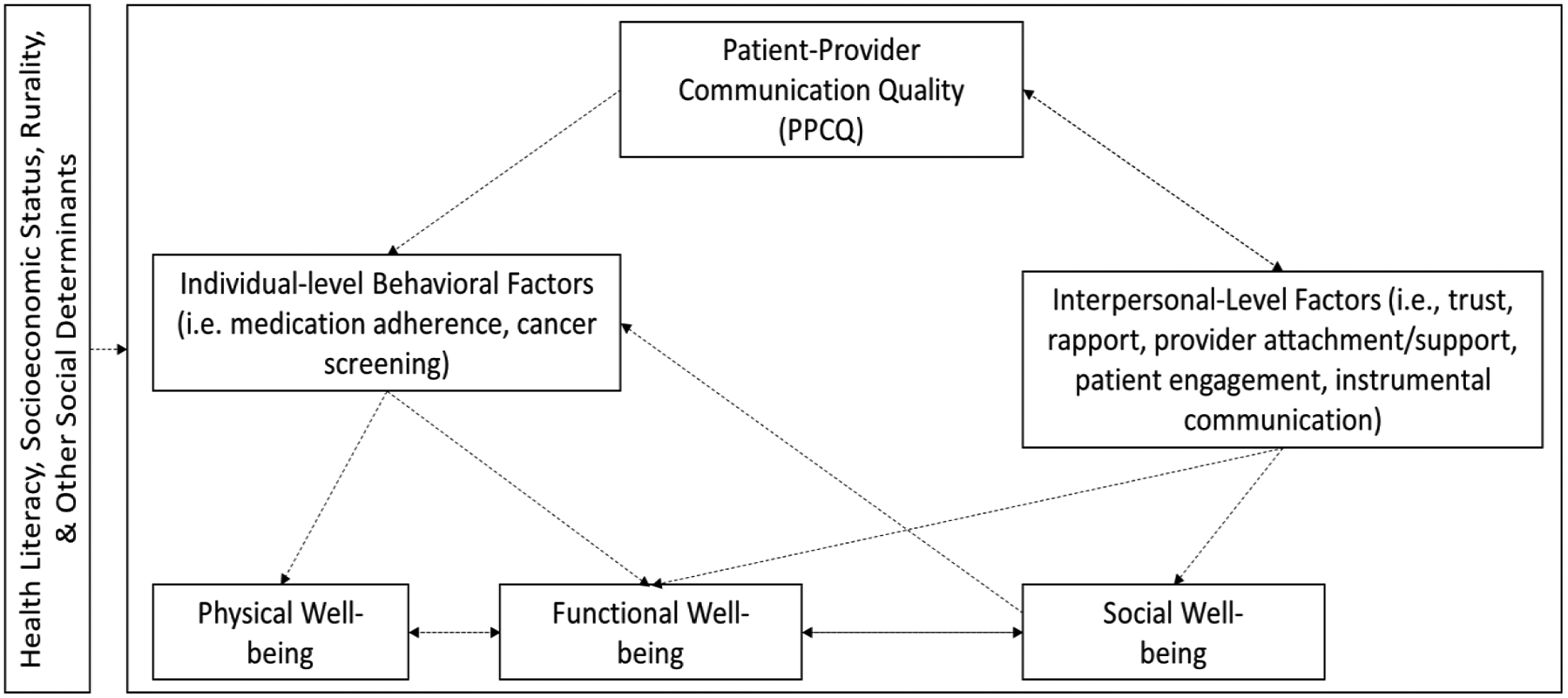

Figure 1 depicts our conceptual framework regarding potential associations between PPCQ and QOL. The framework is derived from the World Health Commission on Social Determinants of Health [10], a QOL framework [11], and health communication theory [12]. PPCQ is defined here as the level of cancer-related information exchange between patient and provider regarding the patient’s health status [13]. High PPCQ is conceptualized as in-depth conversations about treatment options and treatment effects (medical, non-medical) between the provider and patient [14]. We focus on three QOL domains that PPCQ may affect: social, physical, and functional well-being. Social well-being is defined as an individual’s evaluation of their interaction with members of their social network (e.g., perceived social support, family functioning, intimacy, acceptance of illness, and communication of illness with family) [15]. Functional well-being is defined as an individual’s evaluation of their daily life activities and abilities to perform routine tasks [16]. Physical well-being is defined as an individual’s vitality and perceived physical health [17].

Figure 1:

Conceptual Framework of the relationship between Patient-Provider Communication Quality and Quality of Life Domains

Based on our Figure 1, we posit that high PPCQ may improve QOL through positively affecting patients’ individual-level behaviors (e.g., medication adherence, cancer screening [18, 19]); and, interpersonal-level factors between the patients and providers (e.g., trust, rapport, provider support [20]). Both pathways may have multi-faceted health benefits. Individual-level behaviors may specifically directly impact perceived functional well-being and, ultimately, physical well-being through improved physical health outcomes (e.g., reduced symptom burden [21]). Interpersonal-level factors may, conversely, directly impact perceived social well-being [22]. Simultaneously, interpersonal-level factors may indirectly impact functional well-being through changes in information exchange (e.g., needs assessments, referrals) [23] and subsequent efforts to improve individual-level behaviors. These indirect effects may in turn lead to positive effects for physical well-being in the long-term. Yet, physical well-being may be more strongly associated with clinical factors (e.g., stage of diagnosis, treatment type) than PPCQ and other social factors [11]. Further, our conceptual framework stipulates that these relationships, especially physical well-being, may depend on a number of intersecting contextual factors that underlie various social determinants of health, including (but not limited to): patients’ health literacy levels; race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and rural residence [24, 25].

As a first step to test this framework, we explored the relationships between PPCQ with social, functional, and physical well-being among self-identified rural cancer survivors. We focused on rural residence for this study, due to disparities noted above and the simultaneous underrepresentation of this population in research [26]. Below, we provide our hypotheses and theoretical rationale, based on our conceptual framework.

Hypothesis 1: We hypothesized that rural patients with high PPCQ would report greater social and functional well-being than rural patients with low/medium PPCQ. Theoretically, we believed these differences in social and functional well-being would be due to PPCQ’s universal effects on interpersonal-level factors [27] across urban and rural residents.

Hypothesis 2: We hypothesized that rural patients with high and low/medium PPCQ would not differ in physical well-being. Theoretically, we believed this lack of association may either be due to rural populations’ disproportionate exposure to adverse contextual factors (e.g., economic hardship; geographic access to care) [28] or to physical well-being’s stronger relationship with clinical factors (e.g., type of treatment, cancer stage) [11] than social factors.

Methods

Study Sample

Data were derived from the Illinois Rural Cancer Assessment (IRCA) Study [29–31]. The focus of this cross-sectional parent study was to assess patient-reported outcomes of adult Illinois residents who self-identified as being rural cancer survivors, caregivers of rural cancer survivors, or both. All recruitment and data collection procedures have been previously reported [29–31] and were approved by the University of Illinois Cancer Center Protocol Review Committee and the University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board. Briefly, study participants were recruited during Wave 1 (January 2017-February 2018) and Wave 2 (March 2018-September 2018). During Wave 1, we recruited participants by providing printed and electronic flyers to community organizations (e.g. churches, cancer centers, support groups, public health departments, etc.), websites, and listservs. Interested participants contacted research staff members. During Wave 2, we purchased a commercial phone list for residents within 63 non-metropolitan Illinois counties (Rural Urban Continuum Code (RUCC)≥4[32]) and 1 metropolitan county (RUCC=3) that was adjacent to key non-metropolitan Illinois counties. Participants recruited in Wave 2 were contacted via phone call and text message on their landline and mobile phone.

Eligible participants were consented and later given a survey to complete by phone, mail, or in person. All completed surveys were entered into Qualtrics by a trained research team member. Each participant was provided with $15 to $25 to compensate them for their time. Differences in incentives reflected different waves and the addition of a request to keep participants’ contact information for recruitment of future studies. The total study sample included 227 adult cancer survivors and caregivers. The current study focused solely on the cancer survivor participants (n=139).

Measures

Quality of Life (QOL).

These QOL domains were assessed through the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - General (FACT-G) tool [33], including 7 items for social well-being, 7 items for functional well-being, and 7 items for physical well-being (Table 1). Responses to each item ranged from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). For physical well-being, items were reverse-coded 0 (very much) to 4 (not at all). All items within each domain were summed, resulting in a range from 0–28. Higher scores indicated greater social, functional, and physical well-being. Cronbach’s alpha for social, functional, and physical well-being were respectively 0.87, 0.89, and 0.85.

Table 1:

FACT-G Items for Different Quality of Life Domains.1

| Domain | Items |

|---|---|

| Functional well-being |

|

| Physical well-being |

|

| Social well-being |

|

Responses to each item ranged from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). For physical well-being, items were reverse-coded 0 (very much) to 4 (not at all). All items within each domain were summed, resulting in a range from 0–28. Higher scores indicated greater social, functional, and physical well-being.

Patient-Provider Communication Quality (PPCQ).

The 4-item Medical Expenditure Panel Survey’s (MEPS) Experience with Cancer Care tool was used to measure PPCQ [34]. The four items respectively focused on patient-provider communication about lifestyle/health recommendations, regular follow-up care/monitoring, emotional/social needs, and late/long-term cancer treatment side effects. Responses fell within three ordinal categorical variables: High (a majority of responses were “discussed in detail” and 0 responses were “did not discuss”), Medium (responses were a combination of “briefly discussed”, “discussed in detail”, and “did not discuss”), and Low (at least one or more responses of “did not discuss” and few if any responses of “discussed in detail”). Based on preliminary review of frequency distributions, we dichotomized this variable into two categories: High and Low/Medium.

Demographic Covariates.

Respondents also provided information regarding their age, gender, race, marital status, education, employment status, annual household income, and private insurance status. Given our small sample size, we generated a socioeconomic composite score by conducting a principal component analysis within SPSS for the following variables: education, income, and private insurance. Tertiles were used for all analyses with this composite score. They also provided their geographic information which allowed us to classify their county-level rurality, using the Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (RUCC). Counties with RUCC 4–9 were classified as non-metropolitan and counties with RUCC 1–3 were classified as metropolitan [32].

Clinical Covariates.

Respondents reported the primary cancer site of their diagnoses; whether they were actively in treatment (no, yes); their lifetime comorbidities, using the Self-Administered Comorbidity [35]; and, their treatment-related symptoms, using the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) [36].

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using the statistical software program SPSS, version 25 [37]. Relatively low levels of missingness were observed for the socioeconomic composite score variable. No other variables exhibited missingness. As a result, single imputations were conducted by imputing the overall value of the mean for the socioeconomic composite score.

Descriptive statistics (e.g., %s, frequencies) and bivariate analyses (e.g., chi-squared tests, one-way ANOVAs) were first calculated (Table 2). Multivariable linear regressions were subsequently conducted to assess the relationship between PPCQ and the three QOL domains after adjusting for the following variables: age, socio-economic composite score, marital status, rurality, cancer site, cancer treatment status, number of comorbidities, and Global Distress score (Table 3). Our sensitivity analyses replicated models with participants with non-imputed data only; female participants only; non-Hispanic White participants only; patients residing in non-metropolitan counties only; and Wave 1 participants only.

Table 2:

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the Illinois Rural Cancer Assessment respondents by post-treatment communication and follow-up care utilization (n = 139)

| PPCQ1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | High | Low/Medium | p-value | ||||

| N (%) | 139 | 100% | 45 | 32% | 94 | 68% | -- |

| SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS | |||||||

| Age, Mean (SD)2 | 58.09 | 12.10 | 58.73 | 12.4 | 57.79 | 12.00 | 0.67 |

| Gender, n (%)3 | 0.04 | ||||||

| Male | 24 | 17% | 12 | 27% | 12 | 13% | |

| Female | 115 | 83% | 33 | 73% | 82 | 87% | |

| Race, n (%)3 | 0.62 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 126 | 91% | 40 | 89% | 86 | 92% | |

| Other | 13 | 9% | 5 | 11% | 8 | 8% | |

| Marital Status, n (%)3 | 0.87 | ||||||

| Married | 97 | 70% | 31 | 69% | 66 | 70% | |

| Not married | 42 | 30% | 14 | 31% | 28 | 30% | |

| Education, n (%) 3 | 0.17 | ||||||

| <Bachelor’s Degree | 78 | 56% | 29 | 64% | 49 | 52% | |

| ≥Bachelor’s Degree | 61 | 44% | 16 | 36% | 45 | 48% | |

| Employment Status, n (%)3 | 0.44 | ||||||

| Employed | 86 | 62% | 26 | 58% | 60 | 64% | |

| Not employed | 52 | 37% | 19 | 42% | 33 | 35% | |

| Missing | 1% | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1% | ||

| Annual household income, n (%)3 | |||||||

| <$50,000 | 67 | 48% | 26 | 61% | 41 | 46% | 0.12 |

| ≥$50,001 | 65 | 47% | 17 | 40% | 48 | 54% | |

| Missing | 7 | 5% | 2 | 4% | 5 | 5% | |

| Private insurance, n (%)3 | 0.35 | ||||||

| Yes | 79 | 57% | 23 | 51% | 56 | 40% | |

| No | 60 | 43% | 22 | 49% | 38 | 60% | |

| Socioeconomic composite (education, income, and insurance)2,4 | 0.14 | ||||||

| Tertile 1 (Range: −2.47 to −0.47) | 43 | 31% | 19 | 42% | 24 | 26% | |

| Tertile 2 (Range: −0.37 to 0.52) | 43 | 31% | 11 | 24% | 32 | 34% | |

| Tertile 3 (Range: 0.62 to 1.30) | 46 | 33% | 13 | 29% | 33 | 35% | |

| Missing | 7 | 5% | 2 | 4% | 5 | 5% | |

| County rurality5 | 0.09 | ||||||

| Populations of ≥20,000 (RUCC <4) | 54 | 39% | 22 | 49% | 32 | 34% | |

| Populations of <20,000 (RUCC 4+) | 85 | 61% | 23 | 51% | 62 | 66% | |

| CLINICAL COVARIATES | |||||||

| Cancer Sites, n (%)3,6 | 0.94 | ||||||

| Breast cancer | 58 | 41.7 | 19 | 42% | 39 | 42% | |

| Other | 81 | 58.3 | 26 | 58% | 55 | 59% | |

| Currently being Treated, n(%) | 0.31 | ||||||

| Yes | 42 | 30% | 11 | 24% | 31 | 33% | |

| No | 97 | 70% | 34 | 76% | 63 | 67% | |

| Total Comorbidities, M (SD)2,7 | |||||||

| 5.40 | 3.26 | 4.89 | 3.14 | 5.65 | 3.30 | 0.20 | |

| Treatment-related symptoms (Global Distress), M (SD)2,8 | |||||||

| 0.78 | 078 | 0.55 | 0.67 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.02 | |

| QUALITY OF LIFE (QOL), M (SD)2,9 | |||||||

| Social Well-being | 18.64 | 5.7 | 17.91 | 5.38 | 20.16 | 4.39 | 0.02 |

| Functional Well-being | 19.75 | 6.45 | 18.73 | 6.18 | 21.87 | 6.55 | 0.007 |

| Physical Well-being | 21.55 | 5.46 | 21.00 | 5.39 | 22.69 | 5.51 | 0.09 |

Patient Provider Communication was measured 4-item survey instrument from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey’s (MEPS). [34] Experience with Cancer Care section

Mean values, standard deviations, and p-values were obtained by accessing between group different between high patient-provider communication and low/medium patient provider communication using one-way ANOVA tests within SPSS.

Frequencies, percentages, and p-values were obtained by conducting Person chi-squared tests within SPSS.

Teritles were created based on the SES composite score with the maximum value of 1.30 indicating most disadvantaged and the minimum value of −2.47 indicating least disadvantage.

Rural Urban Continuum Code (RUCC). RUCC 1–3 codes incorporate populations with ≥20,000 residents in metropolitan areas. RUCC 4–9 incorporate urban and completely rural areas with populations of <20,000.

Other within this category includes the following cancer sites: testicular, melanoma, skin, lung, bone, kidney, bladder, stomach, prostate, pancreatic, thyroid, colon, liver, rectal, Hodgkins Lymphoma, non-Hodgkins Lympohma, and leukemia.

Data were derived from the Comorbidity Questionnaire [35]. Responses for comorbidities are dichotomous with participants selecting either “yes” or “no.” The ranges are respectively 0 to 14.

Global Distress was measured by the 24 items of the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS). 0–4 was the possible range for this variable [36].

Range values social well-being, functional well-being, and physical well-being are 0–28 with higher scores indicating better quality of life [33].

Table 3:

Multivariable, Adjusted Linear Regression Models Assessing Relationships Between Patient Provider Communication Quality (PPCQ)1 and Quality of Life Domainsa

| Social Well-being | Functional Well-being | Physical Well-being | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std. β | 95% CI | p-value | Std. β | 95% CI | p-value | Std. β | 95% CI | p-value | |

| PPCQ (all participants) (n=139) | 0.20 | 0.03, 0.35 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.05, 0.35 | 0.01 | 006 | −2.51, 0.21 | 0.41 |

| SENSITIVITY ANALYSES | |||||||||

| PPCQ (female participants only) (n=115) | 0.18 | −0.02, 0.37 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.02, 0.36 | 0.03 | −0.06 | −0.23, 0.11 | 0.48 |

| PPCQ (non-Hispanic White participants only) (n=126) | 0.17 | −0.01, 0.35 | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.02, 0.33 | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.10, 0.20 | 0.52 |

| PPCQ (participants in Wave 1) (n=119) | 0.17 | −0.01, 0.35 | 0.07 | 0.15 | −0.01, 0.31 | 0.06 | 0.62 | −0.11, 0.21 | 0.53 |

| PPCQ (participants with RUCC 4+) | 0.19 | −0.02, 0.41 | 0.08 | 0.17 | −0.03, 0.38 | 0.10 | 0.80 | −0.11, 0.25 | 0.48 |

All linear regression models were adjusted for the following covariates: age, gender (ref: male), race (ref: other), marital status (ref: non-married), education (ref:<Bachelor’s), employment (ref: non-employed), income (ref: ≥$50,001), private insurance (ref: no), social economic composite score (ref: teritle 1), RUCC (ref: <4), cancer site (ref: other), currently being treated (ref: yes), total comorbidities score, Global distress score, and PPCQ (ref: non-high). Significant associations (p≤0.05) are marked in bold. Marginal associations (p≤0.10) are italicized.

RESULTS

Table 2 depicts sociodemographic and clinical covariates for patients with higher and low/medium PPCQ. Overall, most participants indicated that their PPCQ was low/medium (68%). The mean age value was 58.1 (SD=12.1). A majority of the study sample was female (83%), non-Hispanic White (91%), married (70%), had a level of education less than a bachelor’s degree (56%), were employed at the time of the study (62%), and, had private insurance (57%). With regard to demographic differences by PPCQ status, a greater proportion of men reported high PPCQ than women (50% or 12/24 vs. 29% or 33/115). Survivors with high PPCQ also reported fewer treatment-related symptoms than survivors with low/medium PPCQ. There were no other significant demographic or clinical differences between survivors with high and low/medium PPCQ.

Crude analyses suggested that survivors with high PPCQ reported greater social and functional well-being (Table 2). Similar patterns were found with our primary, adjusted models (Table 3). Survivors with high PPCQ reported greater social well-being (Std β= 0.20, 95% CI: 0.03, 0.35, p = 0.02) and functional well-being (Std. β= 0.20, 95% CI: 0.05, 0.35, p = 0.01) than survivors with low/medium PPCQ. Survivors with high and low/medium PPCQ had comparable levels of physical well-being (Std. β= 0.06, 95% CI: −2.51, 0.21, p = 0.41). Sensitivity analyses showed largely similar, albeit attenuated patterns.

Discussion

Our study focused on rural survivors, an underserved and understudied population [26]. Self-identified rural cancer survivors with high PPCQ experienced greater social well-being and functional well-being, but comparable physical well-being, relative to rural cancer survivors with low/medium PPCQ. Our findings aligned with our conceptual framework and past research, as discussed below. Our study also served as a first step for considering how the associations of PPCQ and different QOL domains might depend on various social determinants of health. Specifically, our framework and preliminary findings suggest that there may be some universal benefits of high PPCQ, but certain underserved populations may not be able to reap all theoretical benefits.

Our study found that positive associations with high PPCQ, social well-being, and functional well-being, in line with past research [20] and recent efforts to improve functional well-being through improving PPCQ [38]. These associations could potentially have reflected PPCQ’s positive effects on interpersonal factors (i.e., trust, rapport, provider attachment/support, etc.), as described in our conceptual framework [20]. These interpersonal factors may be very important for rural survivors, due to their geographic isolation and limited access to health information [39]. Yet, it should be noted that interpersonal-level factors may also result in higher PPCQ. Future longitudinal studies are warranted to confirm our findings, including the directionality and potential feedback loops of associations; mediation effects of interpersonal-level factors on associations between PPCQ and QOL domains; and, the universal/consistent associations of PPCQ and QOL domains among urban and rural survivors.

Findings that no association was observed between PPCQ and physical well-being also supported our conceptual framework. Specifically, our work contradicted research with largely urban samples [40]. These discrepancies, theoretically, could have reflected urban-rural differences in economic hardship/healthcare access [28] and associated challenges in maintaining healthy behaviors (e.g., medication adherence, physical activity). Alternatively, in line with QOL frameworks [11], physical well-being could have been more associated with type of treatment, cancer stage, and physiological sequelae than with PPCQ and other social factors. Future research is warranted to disentangle these two possibilities; and, directly test the potential moderating effects of residence on associations between PPCQ and QOL.

In addition to our primary hypotheses, our study offers preliminary findings concerning associations of PPCQ with gender and treatment-related symptoms. First, a greater proportion of male cancer patients reported higher PPCQ than low/medium PPCQ, in line with a recent systematic review [41]. Nonetheless, these differences should be considered cautiously, given the very small number of male participants in our study. Second, our work suggests that patients with high PPCQ reported fewer treatment-related effects than patients with low/medium PPCQ. Such work aligns with other research suggesting the importance of PPCQ for various survivorship outcomes such as medication adherence [42].

Limitations

This study is not without its limitations. Our primary limitations included a small convenience-based, fairly homogeneous, cross-sectional sample. Despite IRCA participants’ likeness to nationally representative rural populations in regard to age and private insurance status [43], the present sample generally had higher education attainment and a larger annual household income, and overrepresentation of non-Hispanic white women. Thus, our findings are not likely to be generalizable. Our small sample size may have also resulted in reduced statistical power, especially for associations with relatively weak magnitude, such as PPCQ and physical well-being. Because this study is cross-sectional in nature, the causality of PPCQ on the QOL among rural cancer survivors also could not be determined. Further, given our small sample size, we were unable to test our conceptual framework directly in terms of moderation analyses. The independent variable, PPCQ, also relied on the study participant’s ability to recall their experiences post-diagnosis. However, patients’ ability to recall certain aspects of communication with their provider may not have been completely accurate [44]. To mitigate this limitation partially, we controlled for whether or not the participant was in active treatment. Nonetheless, we were unable to address recall bias completely. The parent study did not administer the entire FACT-G instrument; consequently, it was not possible for us to examine the association of PPCQ with emotional well-being. Further, FACT-G social and function well-being items focused on well-being, whereas FACT-G physical well-being items focused on worse health but were reverse coded to reflect well-being. Differences in wording potentially affected observed associations. High PPCQ differs across cancer types, based on differing guidelines for recommended survivorship and follow-up care. Because of our small sample, we were not however able to distinguish differences in PPCQ and its associations with QOL across cancer types. Relatedly, this pilot study did not collect important clinical variables that may have influenced relationships. For example, we did not collect cancer staging data, which may have mediated relationships between PPCQ and QOL. For the current study, we focused on self-identification as our operationalization of rurality, as this might be particularly useful when focusing on social norms and values [9]. Objective measurements may however have been particularly beneficial with regard to associations dependent on contextual (e.g., geographic access to healthcare) and other factors. To address these issues, we conducted a sensitivity analysis focusing only on residents who both perceived themselves to be rural and lived in counties designated as rural, based on NCI recommendations [45]. These analyses found similar findings. However, it should be noted that the definition of rurality is an ongoing challenge and how we operationalized rurality may have affected our results.

Future Implications

Our study provides an important conceptual framework by which to understand patient-provider relationships and survivorship outcomes in terms of specific factors related to the social determinants of health among rural cancer survivors. Our preliminary data aligned with our hypotheses. Our findings suggest the need for research that assess the: 1) mediating roles of different theoretical mechanisms; and, 2) moderating effects of rurality on PPCQ and physical well-being. Finally, our research is informative for an understudied health disparity patient population. More work is needed to support QOL and health outcomes of cancer survivors within this population. Future researchers, community health advocates, and stakeholders should collaborate with one another to increase the PPCQ among rural cancer survivors. This strategy may provide an effective approach for reducing the existing disproportionate health burden rural cancer survivors experience.

Source of funding

This study has been funded by the Center for Research on Women and Gender, University of Illinois at Chicago and the University of Illinois Cancer Center. The corresponding author (Dr. Molina) was financially supported by the National Cancer Institute, K01CA193918. Dr. Strayhorn would like to acknowledge the funding of the National Cancer Institute, T32CA057699.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Informed consent

Each participant provided informed consent prior to their enrollment.

Ethical approval

All procedures involving study participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review board of the University of Illinois Cancer Center Protocol Review Committee as well as the University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ries LA, Harkins D, Krapcho M, et al. (2007) SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2004. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Boer A, Verbeek J, Spelten E, et al. (2008) Work ability and return-to-work in cancer patients. British journal of cancer 98:1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urquhart R, Lethbridge L, Porter G (2017) Patterns of cancer centre follow-up care for survivors of breast, colorectal, gynecologic, and prostate cancer. Current Oncology 24:360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunn KM, Berry NM, Meng X, et al. (2019) Differences in the health, mental health and health-promoting behaviours of rural versus urban cancer survivors in Australia. Supportive Care in Cancer 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zahnd WE MS, Jenkins WD PhD, MPH, Mueller-Luckey GS MS (2017) Cancer Mortality in the Mississippi Delta Region: Descriptive Epidemiology and Needed Future Research and Interventions. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 28:315–328. 10.1353/hpu.2017.0025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burris JL, Andrykowski M (2010) Disparities in mental health between rural and nonrural cancer survivors: a preliminary study. Psycho- Oncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer 19:637–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asare M, Fakhoury C, Thompson N, et al. (2019) The Patient–Provider Relationship: Predictors of black/African American Cancer Patients’ Perceived Quality of Care and Health Outcomes. Health communication 1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White-Means SI, Osmani AR (2017) Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Patient-Provider Communication With Breast Cancer Patients: Evidence From 2011 MEPS and Experiences With Cancer Supplement. Inquiry - Excellus Health Plan; Thousand Oaks 54:. http://dx.doi.org.proxy.cc.uic.edu/10.1177/0046958017727104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soini K, Vaarala H, Pouta E (2012) Residents’ sense of place and landscape perceptions at the rural–urban interface. Landscape and Urban Planning 104:124–134 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marmot M, Allen J, Bell R, et al. (2012) WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. The lancet 380:1011–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrans CE, Powers MJ (1985) Quality of life index: development and psychometric properties. Advances in nursing science [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogers Everett M (1995) Diffusion of innovations. New York 12: [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiner SJ, Barnet B, Cheng TL, Daaleman TP (2005) Processes for effective communication in primary care. Annals of Internal Medicine 142:709–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorflinger L, Kerns RD, Auerbach SM (2013) Providers’ roles in enhancing patients’ adherence to pain self management. Translational behavioral medicine 3:39–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McDowell I (2006) Measuring health: a guide to rating scales and questionnaires. Oxford University Press, USA [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cella DF (1994) Quality of life: concepts and definition. Journal of pain and symptom management 9:186–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reker GT, Wong PT (1984) Psychological and physical well-being in the elderly: The Perceived Well-Being Scale (PWB). Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue canadienne du vieillissement 3:23–32 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schoenthaler A, Knafl GJ, Fiscella K, Ogedegbe G (2017) Addressing the social needs of hypertensive patients: the role of patient–provider communication as a predictor of medication adherence. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 10:e003659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Villani J, Mortensen K (2013) Patient–provider communication and timely receipt of preventive services. Preventive medicine 57:658–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon HS, Street RL Jr, Sharf BF, et al. (2006) Racial differences in trust and lung cancer patients’ perceptions of physician communication. Journal of clinical oncology 24:904–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mosher CE, Daily S, Tometich D, et al. (2018) Factors underlying metastatic breast cancer patients’ perceptions of symptom importance: a qualitative analysis. European journal of cancer care 27:e12540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrell BR, Grant M, Funk B, et al. (1997) Quality of life in breast cancer: Part I Physical and social well-being. Cancer nursing 20:398–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li C-C, Matthews AK, Dossaji M, Fullam F (2017) The relationship of patient–provider communication on quality of life among African-American and white cancer survivors. Journal of health communication 22:584–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Medical Association AHC on the C on SA (1999) Health literacy: report of the Council on Scientific Affairs. JAMA 281:552–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Selden C, Zorn M, Ratzan S, Parker R (2000) Current bibliographies in medicine: health literacy. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blake KD, Moss JL, Gaysynsky A, et al. (2017) Making the case for investment in rural cancer control: an analysis of rural cancer incidence, mortality, and funding trends. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers 26:992–997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corboy D, McLaren S, McDonald J (2011) Predictors of support service use by rural and regional men with cancer. Australian Journal of Rural Health 19:185–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charlton M, Schlichting J, Chioreso C, et al. (2015) Challenges of rural cancer care in the United States. Oncology 29:633–633 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strayhorn SM, Carnahan LR, Zimmermann K, et al. (2019) Comorbidities, treatment-related consequences, and health-related quality of life among rural cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis-Thames MW, Carnahan LR, James AS, et al. (2020) Understanding Posttreatment Patient-Provider Communication and Follow- Up Care Among Self- Identified Rural Cancer Survivors in Illinois. The Journal of Rural Health [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hallgren E, Hastert TA, Carnahan LR, et al. (2020) Cancer-Related Debt and Mental-Health-Related Quality of Life among Rural Cancer Survivors: Do Family/Friend Informal Caregiver Networks Moderate the Relationship? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 0022146520902737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.United States Department of Agriculture, (2013) Rural Urban Continuum Codes. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/

- 33.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. (1993) The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 11:570–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yabroff KR, Dowling E, Rodriguez J, et al. (2012) The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) experiences with cancer survivorship supplement. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 6:407–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, et al. (2003) The Self- Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Care & Research 49:156–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, et al. (1994) The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale: an instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. European Journal of Cancer 30:1326–1336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.IBM Corp N (2013) IBM SPSS statistics for windows. Version 220

- 38.Bakken S, Marden S, Arteaga SS, et al. (2019) Behavioral interventions using consumer information technology as tools to advance health equity. American journal of public health 109:S79–S85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rees CE, Bath PA (2000) The information needs and source preferences of women with breast cancer and their family members: a review of the literature published between 1988 and 1998. Journal of advanced nursing 31:833–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mead EL, Doorenbos AZ, Javid SH, et al. (2013) Shared decision-making for cancer care among racial and ethnic minorities: a systematic review. American journal of public health 103:e15–e29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reese JB, Sorice K, Beach MC, et al. (2017) Patient-provider communication about sexual concerns in cancer: a systematic review. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 11:175–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rust CF, Davis C, Moore MR (2015) Medication adherence skills training for African-American breast cancer survivors: the effects on health literacy, medication adherence, and self-efficacy. Social work in health care 54:33–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Symens AS, Trevelyan E (2019) Older populations in rural America In Some States, More Than Half of Older Residents Live in Rural Areas. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/10/older-population-in-rural-america.html. Published 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gabrijel S, Grize L, Helfenstein E, et al. (2008) Receiving the diagnosis of lung cancer: patient recall of information and satisfaction with physician communication. Journal of clinical oncology 26:297–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rural Definitions—Overview and Rural Demographic Patterns: 2018. In: National Cancer Institute; Rural Cancer Control Meeting [Google Scholar]